Validating AI Predictions of Polymer Properties: From Computational Models to Laboratory Synthesis

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the methods and challenges in validating artificial intelligence (AI) predictions for polymer properties, a critical step for their application in drug development and...

Validating AI Predictions of Polymer Properties: From Computational Models to Laboratory Synthesis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the methods and challenges in validating artificial intelligence (AI) predictions for polymer properties, a critical step for their application in drug development and materials science. We explore the foundational principles of polymer informatics, examine cutting-edge methodological approaches including foundation models and novel chemical representations, and address key troubleshooting areas such as data scarcity and model interpretability. Furthermore, we present a detailed framework for the experimental and computational validation of AI models, featuring comparative analyses of performance and recent case studies of successfully synthesized AI-designed polymers. This resource is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to robustly integrate AI into their polymer discovery pipelines.

The Foundations of AI in Polymer Informatics: Core Concepts and Unique Challenges

The Core Challenges in Polymer Data Collection

For researchers and scientists in polymer science, the journey to discovering new materials is often hampered by a fundamental obstacle: the scarcity of high-quality, labeled experimental data. This "small data" problem stems from several intrinsic and experimental challenges that make data collection both costly and time-consuming.

Intrinsic Molecular Complexity: Unlike small molecules or inorganic materials, synthetic polymers are rarely a single, well-defined entity. They are typically described by distributions of molecular weights, chain lengths, and sequences. Even a polymer sample made from a single monomer requires the characterization of its molecular mass distribution and dispersity, making its complete description inherently complex and data-intensive [1].

Inconsistent Nomenclature and Identification: The field suffers from a lack of standardized naming. A single polymer like polystyrene can be known by over 1,800 different names [1]. While systems like IUPAC naming and CAS numbers exist, they have shortcomings for polymers, and identifiers like the IUPAC international chemical identifier (InChI) have only recently added support for linear polymers, with no support for more complex branched structures [1]. This complicates the creation of unified, searchable databases.

Costly and Time-Consuming Experimentation: Acquiring property data involves extensive laboratory synthesis and testing, which is both expensive and slow. The development cycle for new materials can typically take 10 to 20 years [1]. This high barrier limits the volume of data that can be generated, creating a significant bottleneck for data-driven research.

Context-Dependent Properties and Reporting: Polymer properties are not always fundamental state variables. Properties like density can vary significantly with processing history [1]. Furthermore, many key properties are "application" or "phenomenological" properties, meaning their measured value depends heavily on the specific method of measurement and analysis. Without standardized reporting of this contextual information, data points from different sources can be difficult to compare or integrate.

AI Strategies to Overcome Data Scarcity

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) are providing innovative pathways to mitigate these data challenges. Researchers are developing sophisticated methods to make the most of limited data and generate reliable synthetic data for training models.

Table 1: AI and Machine Learning Approaches to Polymer Data Scarcity

| Methodology | Core Principle | Key Advantage | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-task Auxiliary Learning [2] | A model is trained simultaneously on a primary task with scarce data and multiple auxiliary tasks with abundant data. | Leverages shared learnings across different (but related) property predictions to improve performance on the data-scarce primary task. | Using a large dataset of various polymer properties (auxiliary tasks) to improve the prediction of a specific, poorly-labeled property (target task). |

| Physics-Informed Synthetic Data [3] | Using physics-based models and group contribution theory to generate a large volume of synthetic, labeled polymer data. | Provides a physically consistent starting point for AI models, allowing them to learn fundamental rules before fine-tuning with real data. | Generating 3,237 hypothetical but physically admissible polymers with properties estimated via group contribution for pre-training LLMs [3]. |

| Two-Phase "Prediction-Correction" [3] | Phase 1: Supervised pre-training of an AI model using large amounts of synthetic data. Phase 2: Fine-tuning the model with limited experimental data. | Achieves >50% improvement in prediction accuracy in data-scarce conditions (e.g., for polymer flammability metrics) compared to direct fine-tuning [3]. | Learning polymer flammability metrics like time to ignition and peak heat release rate where experimental cone calorimeter data is extremely limited [3]. |

| Transfer Learning [4] | An AI model first learns from a large dataset of related materials (e.g., small molecules) and is then adapted to the specific polymer task. | Reduces the need for a massive, exclusive polymer dataset by leveraging chemical knowledge from other domains. | Supplementing data for 100 polymers with related data from 3,000 small molecules to build a predictive model for thermal properties [4]. |

Experimental Workflow for Data-Scarce AI Modeling

The following diagram illustrates a modern, integrated workflow that combines physics-based modeling, AI, and targeted experimentation to overcome data scarcity, as demonstrated in recent research [3].

Protocol: Two-Phase AI Model Training with Limited Experimental Data

This protocol details the methodology for training an accurate AI model when experimental data is scarce, as depicted in the workflow above [3].

Phase 1: Supervised Pre-training with Physics-Based Synthetic Data

- Step 1: Generate Hypothetical Polymers: Use physics-based group contribution (GC) methods to systematically combine molecular groups into thousands of structurally valid, hypothetical polymers. This ensures the generated structures are physically admissible [3].

- Step 2: Calculate Fundamental Properties: For each generated polymer, use GC relationships to estimate a suite of fundamental properties (e.g., heat of combustion, heat capacity, pyrolysis kinetic parameters) [3].

- Step 3: Run Simulations: Use the calculated properties as inputs to high-fidelity physics-based simulators (e.g., Fire Dynamics Simulator for flammability) to generate synthetic data for complex properties of interest (e.g., peak heat release rate) [3].

- Step 4: Pre-train the Model: Conduct supervised training of a Large Language Model (LLM) or other AI model using the generated synthetic polymer-property dataset. This phase aligns the model's parameters with the underlying physical rules of polymer chemistry [3].

Phase 2: Fine-Tuning with Limited Experimental Data

- Step 5: Curate Experimental Dataset: Gather a small set of high-quality, experimentally measured data for the target property. This dataset is limited but represents the ground truth.

- Step 6: Fine-Tune the Model: Initialize the AI model with the weights from the pre-trained model in Phase 1. Then, perform additional training (fine-tuning) exclusively on the small experimental dataset. This "corrects" for the inaccuracies and simplifications inherent in the synthetic data and hones the model's predictive power for real-world applications [3].

Validation and Iteration

- Step 7: Predict and Validate: Use the fine-tuned model to predict properties for novel polymer candidates. Select the top candidates for laboratory synthesis and testing.

- Step 8: Expand the Dataset: Incorporate the new experimental results back into the training dataset, creating a virtuous cycle of model improvement and data expansion.

Comparative Performance of AI Models and Databases

With multiple approaches and databases available, benchmarking their performance on key properties is crucial for researchers to select the right tool.

Table 2: Benchmarking Polymer Informatics Tools and Performance

| Tool / Database | Data Scale & Type | Reported Performance on Key Properties | Notable Features & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| OpenPoly Database [5] | 3,985 experimental polymer-property data points across 26 properties. | XGBoost with Morgan fingerprints achieves R² of 0.65–0.87 on dielectric constant, glass transition (Tg), melting point (Tm), and mechanical strength in data-scarce conditions. | Provides a consistent benchmark; used to propose polymers for high-temperature dielectrics and fuel cell membranes. |

| Citrine AI Platform [4] | Trained on 100 proprietary polymer data points; used transfer learning from 3,000 small molecules. | AI model accuracy was within the ±20 unit margin of error of the lab measurement method for a target thermal property. | Hierarchical AI model; enabled screening of 2,000+ virtual polymers to identify a shortlist of 10 top candidates for lab testing. |

| Georgia Tech AI (polyBERT) [6] | AI algorithms trained on existing polymer data. | Successfully designed a new class of polynorbornene and polyimide polymers for capacitors that simultaneously achieve high energy density and high thermal stability. | Uses SMILES string representation of polymers; models are available via cloud-based software (Matmerize) for industry use. |

| Two-Phase LLM Framework [3] | Pre-trained on 3,237 synthetic polymers; fine-tuned with limited cone calorimeter data. | Supervised pre-training improved final prediction accuracy by over 50% for flammability metrics (time to ignition, peak heat release rate). | Combines LLMs, physics-based modeling, and experiments; specifically tackles the "pathology of data scarcity." |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Polymer Informatics

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Polymer AI

| Item / Solution | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Group Contribution (GC) Methods [3] | A physics-based method to estimate fundamental polymer properties from their constituent molecular groups, enabling the generation of labeled synthetic data for pre-training AI models. |

| SMILES Notation [6] [4] | A string-based representation (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System) that encodes a polymer's molecular structure into a format readable by AI and machine learning models. |

| Morgan Fingerprints / Molecular Descriptors [5] | A numerical representation of a molecule's structure, converting complex chemical information into a feature vector that machine learning algorithms (e.g., XGBoost) can process for property prediction. |

| Cloud-Based AI Platforms (e.g., Matmerize, Citrine) [6] [4] | Provides industry-ready, modular AI software that allows researchers to input their data and virtually screen polymer candidates, accelerating the transition from AI discovery to application. |

| Benchmark Databases (e.g., OpenPoly, PolyInfo) [5] | Curated, open-access datasets of polymer properties that serve as a standard ground truth for training new AI models and fairly comparing the performance of different algorithms. |

The predictive power of artificial intelligence (AI) in polymer science is fundamentally constrained by the quality, diversity, and integration of the underlying data. As researchers develop increasingly sophisticated machine learning (ML) models to predict properties like glass transition temperature, melt flow rate, and mechanical strength, the community faces a critical challenge: how to effectively unite disparate data types—from precise experimental measurements and large-scale molecular simulations to historical legacy records—into a cohesive, validated knowledge base. This guide objectively compares the performance of various data integration and AI modeling approaches, providing a framework for assessing their efficacy in predicting key polymer properties. The validation of AI predictions hinges on robust benchmarking against standardized experimental data, a process that requires meticulous methodology and transparent reporting of protocols.

Comparative Analysis of Polymer Data Platforms and AI Models

The ecosystem of data resources and AI models for polymer research is diverse, with different platforms and approaches offering distinct advantages depending on the data landscape and target properties. The table below provides a structured comparison of these key resources.

Table 1: Comparison of Polymer Data Platforms and AI Modeling Approaches

| Platform / Model Name | Data Source & Type | Key Polymer Properties Predicted | Reported Performance (Metric / Value) | Primary Use-Case / Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OpenPoly Database [5] | Literature-mined, manually validated experimental data (3,985 data points) | Dielectric constant, Glass transition (Tg), Melting point (Tm), Mechanical strength | R²: 0.65 - 0.87 (XGBoost on key properties) | Multi-property benchmarking; Optimal trade-off between cost and accuracy [5] |

| PolyArena Benchmark [7] | Quantum-chemical datasets (PolyData) & experimental benchmarks (130 polymers) | Density, Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) | Accurately predicts densities and captures Tg phase transitions; Outperforms classical force fields [7] | Validating Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs) against experimental bulk properties [7] |

| polyBERT / TransPolymer [5] | Large-scale chemical language models trained on polymer sequences | Various polymer properties | Enables fully machine-driven, ultrafast polymer informatics [5] | Leveraging legacy data and chemical language for rapid screening [5] |

| Vivace MLFF [7] | Quantum-chemical data (PolyData: PolyPack, PolyDiss, PolyCrop) | Density, Thermodynamic properties (e.g., Tg) | Accurately predicts polymer densities ab initio; Captures second-order phase transitions [7] | High-accuracy molecular dynamics simulations for polymer design [7] |

| LAIML-MFRPPPA Model [8] | Industrial process data (1,044 samples: temp, pressure, catalyst feed) | Melt Flow Rate (MFR) | R²: 0.965, MAE: 0.09, RMSE: 0.12 [8] | Real-time industrial quality control and process optimization [8] |

| ML-based Generative Design [6] | Existing material-property datasets | Energy density, Thermal stability | Successful lab synthesis & validation of AI-predicted polymers for capacitors [6] | Inverse design of polymers with targeted multi-property profiles [6] |

Experimental Protocols for Data Generation and AI Validation

The credibility of AI predictions in polymer science depends on rigorous, reproducible experimental and computational protocols for generating training and validation data. Below are detailed methodologies for key types of data generation and model validation cited in comparative analyses.

Protocol 1: Generating Quantum-Mechanical Data for Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs)

This protocol underpins the development of MLFFs like Vivace, as used for benchmarking in PolyArena [7].

- Objective: To create a diverse dataset of atomistic polymer structures with quantum-mechanically computed energies and forces for training MLFFs.

- Dataset Components:

- PolyPack: Contains multiple, structurally-perturbed polymer chains packed in periodic boundary conditions at various densities. Primarily probes strong intramolecular interactions [7].

- PolyDiss: Consists of single polymer chains in unit cells of varying sizes. Focuses on weaker intermolecular (inter-chain) interactions [7].

- PolyCrop: Comprises fragments of polymer chains in a vacuum, aiding in the model's understanding of local bonding environments [7].

- Computational Methodology:

- Software: Quantum chemistry software packages (e.g., VASP, Gaussian) are used for the calculations [7].

- Level of Theory: Density Functional Theory (DFT) is a standard method for calculating the reference energies and atomic forces for all structures in the dataset [7].

- Labeling: Each atomic configuration in PolyPack, PolyDiss, and PolyCrop is labeled with its DFT-calculated energy and forces.

Protocol 2: Experimental Benchmarking of Glass Transition Temperature (Tg)

This protocol describes the experimental measurement of Tg, a critical property for validating AI predictions, as referenced in the PolyArena benchmark [7].

- Objective: To determine the glass transition temperature of an amorphous polymer sample experimentally.

- Principle: The glass transition is identified as a change in slope of a thermophysical observable (e.g., density or heat flow) as a function of temperature during controlled heating. It marks the transition from a glassy to a rubbery state [7].

- Equipment: Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC).

- Procedure:

- A small, precisely weighed sample of the polymer (5-20 mg) is placed in a hermetic DSC pan.

- The sample and an empty reference pan are subjected to a controlled temperature program in an inert atmosphere (e.g., N₂).

- The program typically involves:

- a. Heating from room temperature to above the expected Tg to erase thermal history.

- b. Cooling at a controlled rate to a low temperature.

- c. Re-heating at a standard rate (e.g., 10°C/min) while recording the heat flow difference between the sample and reference pans.

- The glass transition is observed as a step-like change in the heat flow curve during the second heating cycle.

- Data Analysis: Tg is taken as the midpoint of the step transition in the heat flow curve, as determined by the instrument's software according to standard protocols (e.g., ASTM E1356).

Protocol 3: Industrial Melt Flow Rate (MFR) Measurement and Model Validation

This protocol outlines both the conventional measurement of MFR and the validation of AI models like LAIML-MFRPPPA, which aims to supersede these offline methods [8].

- Objective: To measure the melt flow rate of a polymer resin, a key indicator of processability and molecular weight, and to use such data for validating real-time prediction models.

- Standard Experimental Method (Offline):

- Equipment: Melt Flow Indexer.

- Procedure:

- Polymer granules are loaded into the instrument's barrel, which is heated to a standardized temperature (e.g., 190°C for polyethylene).

- After a preheat time, a piston is forced down onto the polymer melt by a specified weight.

- The extrudate is cut at timed intervals as it flows through a die.

- The mass of the extrudate over a fixed time is measured.

- Calculation: MFR is reported as the mass of polymer (in grams) extruded over 10 minutes.

- AI Model Validation:

- Data Collection: A dataset of 1,044 industrial samples is used, with input features including reactor temperature, pressure, hydrogen-to-propylene ratio, and catalyst feed rate [8].

- Model Training & Testing: The dataset is split into training and testing sets. Ensemble models (KELM and RVFL) are trained on the training data and their predictions are compared to the experimentally measured MFR values on the test set [8].

- Performance Metrics: Predictive accuracy is evaluated using R², MAE (Mean Absolute Error), RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error), and MAPE (Mean Absolute Percentage Error) [8].

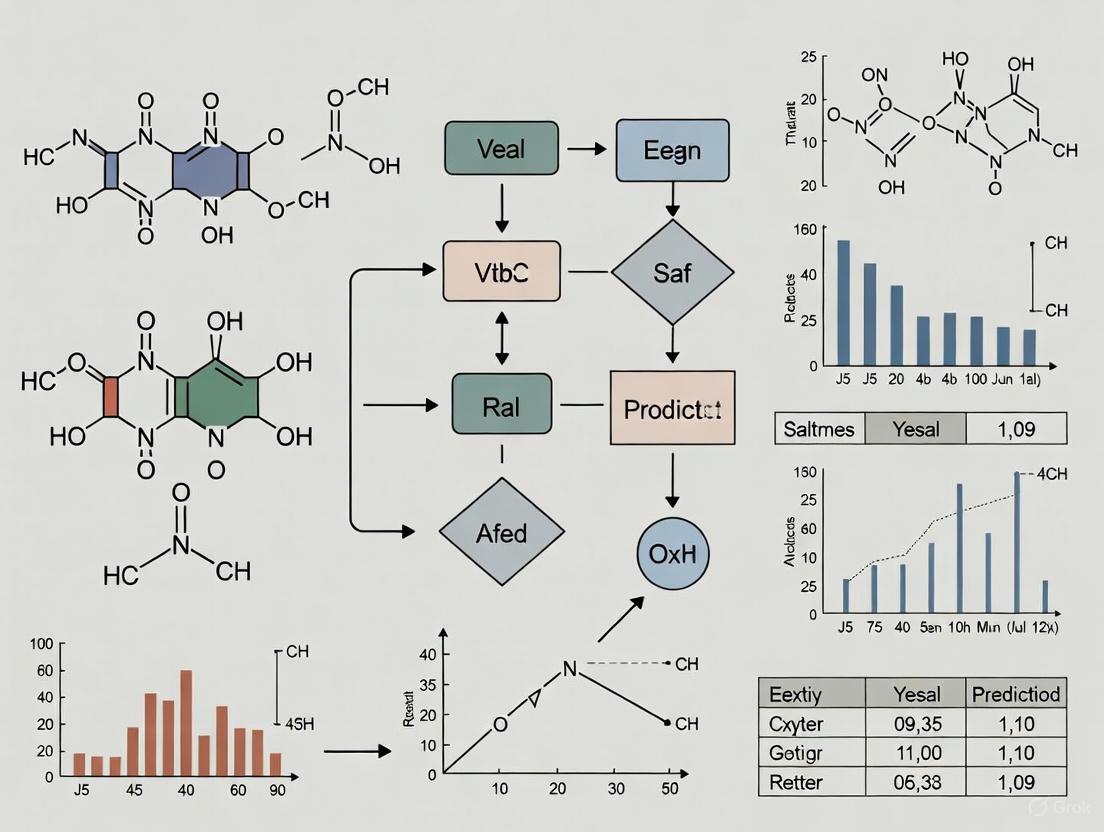

Workflow Visualization: Integrating Data for AI Validation

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for generating, processing, and utilizing diverse data types to validate AI predictions in polymer science.

AI Validation Workflow

This workflow demonstrates the continuous cycle of integrating diverse data sources to train AI models, followed by rigorous benchmarking and experimental validation to ensure predictive accuracy.

Successful AI-driven polymer research relies on a suite of computational and data resources. The table below details key solutions and their functions in the data integration and modeling pipeline.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Polymer AI

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| OpenPoly [5] | Curated Database | Provides a benchmarked, multi-property experimental database for training and validating predictive models. |

| PolyArena / PolyData [7] | Benchmark & Dataset | Offers a standardized benchmark (PolyArena) and accompanying quantum-chemical dataset (PolyData) for evaluating MLFFs on experimental polymer properties. |

| Allegro / Vivace [7] | Machine Learning Force Field (MLFF) | SE(3)-equivariant neural network architectures for accurate, large-scale molecular dynamics simulations of polymers derived from quantum mechanics. |

| Polyply [9] | Polymer Building Tool | Generates realistic initial configurations and entangled structures for molecular dynamics simulations, overcoming pitfalls of simple packing algorithms. |

| Polymer Genome [6] | Informatics Platform | A data-powered polymer informatics platform for the prediction of property profiles and high-throughput screening. |

| Matmerize [6] | Commercial Software | Cloud-based polymer informatics platform enabling virtual material design for industry applications. |

| XGBoost [5] | Machine Learning Algorithm | A tree-based ensemble ML algorithm that has demonstrated high performance (R²: 0.65-0.87) on key polymer properties with limited data. |

| polyBERT / TransPolymer [5] | Chemical Language Model | A transformer-based model that treats polymer sequences as a language, enabling prediction of unified polymer properties from their chemical structure. |

The integration of experimental, simulation, and legacy data is not merely a technical convenience but a foundational requirement for validating AI predictions in polymer research. As demonstrated by the performance comparisons, the accuracy of any given model is intrinsically linked to the quality and relevance of its underlying data landscape. Robust experimental protocols provide the ground truth, large-scale simulations offer atomic-level insight at scale, and curated legacy databases ensure that historical knowledge is not lost but amplified. The future of polymer informatics lies in the continued development of standardized benchmarks like PolyArena and OpenPoly, the refinement of multi-fidelity data integration methods, and the adherence to FAIR data principles. This structured, data-centric approach is key to building trustworthy AI systems capable of accelerating the discovery and development of next-generation polymeric materials.

The integration of artificial intelligence into polymer science has predominantly followed a pattern recognition paradigm, where models are trained to classify and predict properties based on existing structural patterns. While this approach has yielded significant advances in predictive accuracy, it fundamentally limits our capacity to discover novel polymer systems with exceptional or unexpected properties. The field of polymer informatics now stands at a critical juncture, where moving beyond mere classification toward exploratory generative approaches promises to unlock unprecedented opportunities for materials discovery and design.

Traditional machine learning approaches in polymer informatics typically follow a two-step process: first, transforming polymer structures into numerical representations (fingerprints), then applying supervised learning to predict target properties [10]. Methods such as Polymer Genome fingerprints, graph-based polyGNN, and transformer-based polyBERT have demonstrated considerable success in predicting key thermal properties including glass transition temperature (Tg), melting temperature (Tm), and decomposition temperature (Td) [10]. More recently, large language models (LLMs) have emerged as promising tools for polymer property prediction, with fine-tuned versions of LLaMA-3-8B and GPT-3.5 demonstrating the ability to interpret SMILES strings and predict properties directly from text, eliminating the need for handcrafted fingerprints [10].

However, these pattern recognition approaches share a fundamental limitation: they excel at interpolating within known chemical spaces but struggle to generate truly novel polymer structures with optimized property combinations. This limitation becomes particularly problematic when addressing emerging challenges in sustainable materials, extreme environment applications, and multi-property optimization, where incremental improvements often prove insufficient. The transition from classification to exploration represents not merely a methodological shift but a fundamental reimagining of AI's role in materials discovery.

Comparative Performance Analysis: Traditional vs. Modern Approaches

Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Model Architectures

Table 1: Performance comparison of AI models for polymer property prediction

| Model Category | Specific Model | Property Predicted | Performance Metric | Value | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional ML | Polymer Genome | Thermal properties | Not specified | Not specified | Hand-crafted features |

| Graph-based | polyGNN | Thermal properties | Not specified | Not specified | Limited novel structure generation |

| Transformer-based | polyBERT | Thermal properties | Not specified | Not specified | SMILES interpretation only |

| LLM-based | LLaMA-3-8B | Tg, Tm, Td | MAE | Close to traditional methods | Limited cross-property correlation |

| LLM-based | GPT-3.5 | Tg, Tm, Td | MAE | Underperforms LLaMA-3 | Black-box nature |

| Deep Learning | DNN (Natural Fiber Composites) | Mechanical properties | R² | 0.89 | Requires large datasets |

| SMILES-based DL | SMILES-PPDCPOA | Multiple properties | Classification accuracy | 98.66% | Limited to known property classes |

The performance data reveals a consistent pattern: while modern LLM and deep learning approaches can match or approach the predictive accuracy of traditional methods, they each carry distinct limitations. The fine-tuned LLaMA-3 model consistently outperforms GPT-3.5, likely due to the flexibility and tunability of the open-source architecture [10]. Single-task learning generally proves more effective than multi-task learning for LLMs, which struggle to exploit cross-property correlations—a significant advantage of traditional methods [10]. This performance gap highlights a fundamental challenge in polymer informatics: accurate classification does not inherently enable novel discovery.

Performance Under Data Scarcity Conditions

Data scarcity poses particularly challenges for deep learning approaches, which typically require large labeled datasets for optimal performance. The Ensemble of Experts (EE) system has demonstrated superior performance compared to standard artificial neural networks when predicting properties like glass transition temperature and Flory-Huggins interaction parameters under data-scarce conditions [11]. By leveraging tokenized SMILES strings and combining knowledge from multiple pre-trained models, the EE approach captures intricate chemical interactions more effectively than traditional one-hot encodings, maintaining predictive accuracy even when only a fraction of the available data is used for training [11]. This capability is particularly valuable for exploring under-represented regions of polymer chemical space.

Methodological Approaches: From Classification to Exploration

Experimental Protocols for Traditional Predictive Modeling

Traditional machine learning approaches for polymer property prediction follow a structured pipeline with distinct stages:

Data Curation and Standardization: Researchers compile experimental data from various sources, typically focusing on the most frequently reported thermal properties. For example, benchmark datasets might contain 5,253 glass transition temperature (Tg) values, 2,171 melting temperature (Tm) values, and 4,316 thermal decomposition temperature (Td) values [10]. Polymer structures are represented using SMILES strings, which undergo canonicalization to address non-uniqueness and ensure standardized representation.

Molecular Representation: Traditional methods employ specialized fingerprinting techniques to convert structural information into numerical representations. Polymer Genome utilizes hand-crafted fingerprints representing polymers at three hierarchical levels—atomic, block, and chain—capturing structural details across multiple length scales [10]. Graph-based methods like polyGNN employ molecular graphs to learn polymer embeddings, while transformer-based models like polyBERT utilize the linguistic structure of SMILES strings with adaptations for polymers.

Model Training and Optimization: Supervised learning algorithms range from simple linear regression to complex deep learning architectures. For LLM-based approaches, prompt optimization is critical, with the most effective structure following the format: "If the SMILES of a polymer is

, what is its ?" [10]. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning methods like Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) significantly reduce computational overhead while preserving model performance. Validation and Benchmarking: Models are evaluated using rigorous cross-validation techniques, with performance measured through metrics such as mean absolute error (MAE), coefficient of determination (R²), and computational efficiency. Comparative benchmarks assess whether new approaches can surpass established baselines across multiple property prediction tasks.

Generative Approaches for Exploratory Discovery

Generative models for polymer discovery employ fundamentally different protocols:

Chemical Space Expansion: Unlike predictive models that work within existing chemical spaces, generative approaches actively expand these spaces. For example, the PI1M dataset comprising 1 million hypothetical polymers was generated using an RNN trained on actual polymers from PolyInfo, filling gaps where existing data is lacking [12].

Multi-Objective Optimization: Advanced frameworks like the Pareto Optimization Algorithm (POA) enable simultaneous optimization of multiple, potentially competing properties. The SMILES-PPDCPOA model integrates a one-dimensional convolutional neural network with a gated recurrent unit (1DCNN-GRU) and applies POA for hyperparameter tuning, achieving 98.66% classification accuracy across eight polymer property classes [13].

Reinforcement Learning Integration: Models such as REINVENT and GraphINVENT incorporate reinforcement learning to guide the generation process toward polymers with targeted properties, particularly valuable for designing high-temperature polymers for extreme environments [12].

Validity and Diversity Metrics: Generative approaches require specialized evaluation metrics including the fraction of valid polymer structures (fv), uniqueness (f10k), Nearest Neighbor Similarity (SNN), Internal Diversity (IntDiv), and Fréchet ChemNet Distance (FCD) to assess both the quality and diversity of generated structures [12].

Figure 1: Contrasting methodological approaches between traditional pattern recognition and exploratory generation in polymer informatics.

Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Essential research reagents and computational tools for AI-driven polymer exploration

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMILES Strings | Representation | Standardized molecular representation | Canonicalization for consistent model input [10] |

| PolyInfo Database | Data Source | Repository of known polymer structures | Training generative models [12] |

| Polymer Genome | Fingerprinting | Multi-level structural representation | Traditional property prediction [10] |

| Morgan Fingerprints | Representation | Chemical substructure encoding | Predicting compound properties [11] |

| Mol2vec | Representation | Molecular substructure vectors | Transfer learning approaches [11] |

| Optuna | Framework | Hyperparameter optimization | DNN architecture tuning [14] |

| LoRA | Method | Parameter-efficient fine-tuning | Adapting LLMs to polymer tasks [10] |

| Pareto Optimization | Algorithm | Multi-objective optimization | Balancing competing property targets [13] |

| Ensemble of Experts | Framework | Knowledge transfer | Addressing data scarcity [11] |

| t-SNE | Method | Dimensionality reduction | Visualizing chemical spaces [12] |

The tools and reagents listed in Table 2 represent the essential components for both traditional and exploratory AI approaches in polymer science. SMILES strings provide a crucial standardized representation that enables both pattern recognition and generative approaches, though their limitations in capturing polymer-specific complexities remain a challenge [10]. The PolyInfo database serves as the foundational dataset for training both predictive and generative models, though its limited size (18,697 polymer structures) compared to small molecule databases (116 million in PubChem) highlights the data scarcity issues in polymer informatics [12].

Advanced optimization frameworks like Optuna enable efficient hyperparameter tuning for complex deep learning architectures, while methods like Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) make fine-tuning large language models computationally feasible [10] [14]. The Ensemble of Experts approach represents a particularly innovative framework for addressing data scarcity by combining knowledge from multiple pre-trained models, demonstrating that strategic integration of existing knowledge can sometimes compensate for limited data [11].

Generative Model Benchmarking: Performance and Limitations

Recent benchmarking studies have systematically evaluated deep generative models for inverse polymer design, providing critical insights into their relative strengths and limitations. Six popular models—Variational Autoencoder (VAE), Adversarial Autoencoder (AAE), Objective-Reinforced Generative Adversarial Networks (ORGAN), Character-level Recurrent Neural Network (CharRNN), REINVENT, and GraphINVENT—were evaluated using multiple metrics including validity, uniqueness, diversity, and similarity to known polymers [12].

The results revealed that CharRNN, REINVENT, and GraphINVENT demonstrated excellent performance when applied to real polymer datasets, while VAE and AAE showed more advantages in generating hypothetical polymers [12]. This performance pattern highlights a fundamental trade-off: models excelling at reproducing known chemical spaces may struggle with exploration, while those capable of generating novel structures may produce lower yields of valid polymers.

Generative models face unique challenges in polymer informatics compared to small molecules. While small molecules are fully represented by their complete structures in SMILES, polymers require special handling of repeating units and polymerization points (denoted by "" in SMILES) [12]. These wild cards capture specific chemical bonding patterns and connectivity between repeating units, requiring specialized approaches that respect polymer topology and connectivity. Treating "" as a generic wild card can lead to inaccurate depictions of polymer structures and invalid molecular designs [12].

Figure 2: Benchmarking workflow for generative models in inverse polymer design, highlighting key evaluation metrics.

Explainable AI: Validating Model Attention and Feature Selection

As AI models become more complex, ensuring their reliability requires moving beyond traditional performance metrics to examine their decision-making processes. Explainable AI (XAI) techniques provide critical insights into whether models are considering chemically relevant features or relying on spurious correlations [15].

In comprehensive evaluations using both qualitative and quantitative XAI methodologies, models with similar classification performance can demonstrate dramatically different feature selection capabilities. For example, while ResNet50 achieved 99.13% classification accuracy for rice leaf disease detection with strong feature selection capabilities (IoU: 0.432), models like InceptionV3 and EfficientNetB0 showed poor feature selection despite high accuracies, with low IoU scores (0.295 and 0.326) and high overfitting ratios (0.544 and 0.458) [15]. This discrepancy highlights the limitations of relying solely on classification accuracy without examining model attention.

For polymer informatics, similar XAI approaches could validate whether models focus on chemically meaningful substructures when predicting properties. Quantitative metrics like Intersection over Union (IoU), Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC), and specialized overfitting ratios provide objective measures of model reliability, ensuring that predictions stem from chemically plausible reasoning rather than dataset artifacts [15]. This validation is particularly crucial when moving from classification to exploration, as models that learn chemically invalid structure-property relationships will generate nonsensical or unstable polymer designs.

Future Directions: Integrating Exploration and Validation

The future of AI-driven polymer discovery lies in frameworks that seamlessly integrate generative exploration with rigorous validation. Promising directions include:

Hybrid Predictive-Generative Frameworks: Combining the accuracy of predictive models with the novelty of generative approaches through iterative refinement cycles. Predictive models can guide generative sampling toward regions of chemical space with desirable property combinations, while generative models can expand the chemical space beyond the limitations of training data.

Multi-Scale Modeling Integration: Incorporating physical principles and multi-scale simulations to constrain generative models to thermodynamically feasible structures. This approach aligns with the growing emphasis on scientific machine learning, where domain knowledge complements data-driven approaches.

Active Learning and Autonomous Experimentation: Closing the loop between computation and synthesis through automated platforms that iteratively propose, synthesize, and test promising candidates. This approach progressively refines models while directly validating their exploratory capabilities.

Explainable Generative Models: Developing generative approaches that provide chemically interpretable rationales for their designs, enabling researchers to understand not just what structures are generated but why they are expected to exhibit target properties.

These integrated frameworks represent the next evolutionary stage in polymer informatics, moving beyond the pattern recognition paradigm toward a more holistic exploration- validation cycle that accelerates the discovery of novel, high-performance polymer systems.

The transition from pattern recognition to exploratory generation represents a necessary evolution in AI-driven polymer research. While traditional classification approaches have established valuable baselines for property prediction, their inherent limitation lies in constraining discovery to interpolations within known chemical spaces. Generative models, multi-objective optimization, and explainable AI collectively provide the methodological foundation for true exploration, enabling researchers to venture into uncharted regions of polymer chemical space.

The benchmarking data and performance comparisons presented in this analysis clearly demonstrate that no single approach currently dominates across all metrics. Instead, the optimal strategy involves strategically combining elements from traditional predictive modeling, modern generative approaches, and rigorous validation protocols. As the field advances, the integration of physical principles with data-driven exploration, coupled with autonomous experimental validation, promises to accelerate the discovery of novel polymer systems with tailored properties for emerging applications.

The future of polymer informatics lies not in choosing between classification and exploration, but in developing frameworks that intelligently balance both—using pattern recognition to guide exploration and exploration to expand the patterns available for recognition. This synergistic approach will ultimately fulfill the promise of AI-driven materials discovery, moving beyond incremental improvements toward genuinely novel polymer systems with exceptional and previously unattainable property combinations.

The application of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in polymer science represents a paradigm shift from traditional, resource-intensive discovery methods. While traditional approaches like trial-and-error experimentation and high-fidelity computational simulations (e.g., molecular dynamics, density functional theory) provide valuable insights, they are often hampered by extensive time requirements and significant computational costs [16] [17]. AI promises to accelerate this process dramatically, but a critical challenge emerges: models trained solely on data, without incorporating the underlying physics and chemistry, often struggle with predictive accuracy and generalizability, particularly for complex polymer systems where labeled data is scarce [18] [19].

This comparison guide examines the current landscape of AI methodologies for predicting polymer properties, objectively evaluating their performance, underlying mechanisms, and suitability for different research applications. We focus specifically on how the integration of physical laws and chemical domain knowledge—ranging from simple feature engineering to complex hybrid modeling—distinguishes cutting-edge approaches from conventional data-driven models, ultimately enabling more reliable and scientifically valid predictions crucial for research and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of AI Approaches for Polymer Property Prediction

The table below summarizes the core methodologies, strengths, and limitations of different AI approaches for polymer informatics, providing a framework for understanding their relative performance.

| AI Approach | Core Methodology | Key Strengths | Inherent Limitations | Representative Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure Data-Driven ML | Learns patterns exclusively from input-output data, often using models like Random Forest or standard Neural Networks. | High speed once trained; can discover non-intuitive correlations from large datasets [16]. | Poor performance with small datasets; predictions can be physically inconsistent; low generalizability [16]. | Accurate for large, well-defined datasets (e.g., >12,000 samples for superconductor Tc prediction [16]). |

| Physics-Informed Feature Engineering | Incorporates domain knowledge through carefully constructed input features (e.g., molecular fingerprints, Coulomb matrix, radial distribution functions) [17]. | Makes learning more efficient; features have physical meaning; improves model interpretability. | Quality of features limits model performance; requires significant domain expertise to implement. | Used by winning model in NeurIPS 2025 competition (Morgan fingerprints + GNN) for polymer properties [18]. |

| Physics-Constrained Architecture | Uses neural network architectures inherently suited to molecular structures, such as Graph Neural Networks (GNNs). | Naturally operates on molecular graph structures; inherently captures topological information [18]. | Still primarily data-driven; physical consistency is not guaranteed by the architecture alone. | Demonstrated high precision in predicting 5 key polymer properties (e.g., Tg, density) in limited-data scenarios [18] [19]. |

| Hybrid Physics-AI Modeling | Tightly integrates physical models (e.g., DFT, MD) with AI, using AI to learn specific components like the energy functional [17]. | Highest physical fidelity; can extrapolate more reliably; reduces required training data. | Highest implementation complexity; computationally intensive; requires expertise in both AI and physics. | Enabled billion-atom quantum-accurate simulations (Gordon Bell Prize 2020, 2023) [17]. |

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

Validating AI predictions in polymer research requires rigorous methodologies that ensure predictions are not just statistically plausible but also physically meaningful. The following protocols are essential for benchmarking model performance.

The Cross-Validation Strategy for Limited Data

A primary challenge in polymer informatics is the scarcity of high-quality, labeled data. For some key properties, datasets may contain only 200-300 labeled examples amidst thousands of uncharacterized candidates [18]. In this context, the cross-validation strategy employed by the winning team of the NeurIPS 2025 competition is particularly instructive [18].

- Methodology: The available labeled data is split into multiple, non-overlapping training and validation subsets. A model is trained on each unique combination of these subsets.

- Validation: The model's performance is assessed by its average accuracy across all validation folds. This provides a robust estimate of how the model will perform on unseen data, mitigating the risk of overfitting to a small dataset.

- Outcome: This protocol was critical for the team to "find the规律 (patterns) from the non-correct answers" and achieve a balanced performance across the five target properties, ultimately winning the gold medal [18].

Benchmarking Against High-Fidelity Simulations

In many modern AI competitions and research initiatives, the "ground truth" for polymer properties is not derived from a single experiment but from high-fidelity molecular dynamics (MD) simulations [19] [17]. This approach provides a consistent and controlled benchmark for comparing AI predictions.

- Data Generation: Large-scale MD simulations, sometimes accelerated with AI-learned potentials, are run to compute target properties like density, glass transition temperature (Tg), and thermal conductivity for a wide array of polymers defined by their SMILES strings [19] [17].

- Evaluation Metric: The Weighted Mean Absolute Error (wMAE) is a common and stringent metric. It calculates the average absolute difference between the AI-predicted values and the simulation-derived values across all properties, often applying different weights to reflect the varying importance or scale of each property [19]. A lower wMAE indicates superior performance.

Visualizing the Workflow of a Physics-Informed AI Model for Polymers

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of a high-performing, physics-informed AI model for polymer property prediction, synthesizing the key elements from the championed approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Successful implementation of AI-driven polymer research requires a combination of computational tools and data resources. The table below details key components of the research ecosystem.

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research | Relevance to AI Integration |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMILES String | Data Representation | A text-based descriptor of a molecule's structure, serving as the universal input for molecular models [19]. | Provides a standardized input format for AI models to parse chemical structures. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | AI Model Architecture | A deep learning model designed to operate directly on graph data, naturally representing molecules as atom (node) and bond (edge) networks [18]. | Inherently captures topological and relational information from the molecular structure, integrating chemical intuition. |

| Morgan Fingerprint | Molecular Feature | A technique to convert a molecular structure into a fixed-length bit vector based on its topological environment [18]. | Provides a numerical "fingerprint" for traditional ML models, encoding structural features for AI learning. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Simulation Method | Simulates the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, providing "ground truth" data for properties like Tg and density [19] [17]. | Serves as a high-fidelity data source for training and validating AI models; can be integrated into hybrid AI-physics workflows. |

| Cross-Validation | Statistical Protocol | A resampling method used to evaluate model performance on limited data by rotating training and validation subsets [18]. | Critical for preventing overfitting and providing a realistic performance estimate in data-scarce polymer research. |

| Open Polymer Dataset | Data Resource | Large-scale, open-source datasets (e.g., from NeurIPS competitions) containing polymer structures and properties [19]. | Provides the essential, high-quality data required for training and benchmarking robust AI models for polymers. |

The objective comparison of AI methodologies reveals a clear trajectory for the future of polymer informatics. While pure data-driven models offer speed, their applicability is limited without the grounding influence of physical laws. The most successful approaches, as demonstrated by recent award-winning implementations, are those that seamlessly integrate AI with chemistry and physics [18] [17]. This integration occurs at multiple levels: through physics-informed feature engineering (molecular fingerprints, graph representations), through specialized model architectures (GNNs), and ultimately through hybrid models where AI augments rather than replaces physical simulations.

For researchers and drug development professionals, this underscores that the most powerful "virtual lab" will not be powered by AI alone. Instead, it will be a synergistic environment where AI's pattern recognition capabilities are guided and constrained by the fundamental principles of polymer chemistry and physics. This paradigm is key to building trustworthy, predictive models that can reliably accelerate the discovery and design of next-generation polymeric materials and therapeutics.

Advanced Methods for Prediction and Design: Language Models and Feature Engineering

The discovery and development of new polymers have traditionally been resource-intensive processes, relying heavily on experimental trial-and-error that can span over a decade from initial concept to final application [20]. This traditional approach struggles to navigate the immense combinatorial complexity of polymer chemical space, where molecular structures can vary enormously in composition, architecture, and functionality. The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) has transformed this landscape, offering computational methods to predict polymer properties and performance before synthesis ever begins [6] [21]. However, the effectiveness of these AI tools depends fundamentally on how polymer structures are represented in a language that computers can understand.

Molecular string representations serve as the essential bridge between chemical structures and computational algorithms, enabling machines to parse, analyze, and generate novel molecular designs [22] [23]. The field has evolved from early notations like SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) to more robust representations like SELFIES (Self-Referencing Embedded Strings), and recently to specialized formats such as Group SELFIES that incorporate chemical intuition through functional group tokens [24]. Each representation offers different trade-offs between human readability, machine interpretability, and chemical robustness, making the choice of representation a critical determinant of success in AI-driven polymer research. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these leading molecular string representations, examining their technical specifications, performance characteristics, and practical applications within the context of validating AI predictions for polymer properties.

Technical Comparison of Polymer Representation Formats

Fundamental Representations: SMILES and SELFIES

SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System), introduced more than 30 years ago, represents chemical structures using compact ASCII strings that depict atoms, bonds, branches, and rings through specific character sequences [22] [25]. In SMILES notation, atomic symbols represent elements (with uppercase initial letters indicating aliphatic atoms and lowercase indicating aromatic atoms), while bond types are denoted by specific symbols: hyphen (-) for single bonds, equal sign (=) for double bonds, and octothorpe (#) for triple bonds. Branches are represented by parentheses, and rings are indicated by numerical markers showing connection points [25]. Despite its widespread adoption and human-readable format, SMILES has significant limitations for AI applications, particularly its tendency to generate syntactically and semantically invalid strings when processed by generative models [23].

SELFIES (Self-Referencing Embedded Strings) was developed specifically to address the robustness limitations of SMILES for machine learning applications [23] [25]. Unlike SMILES, which can produce invalid molecular structures when strings are mutated or generated by AI, every possible SELFIES string corresponds to a valid molecule with proper atom valencies. This 100% robustness is achieved through a formal grammar based on Chomsky type-2 grammar and finite state automata, which localizes non-local features (like rings and branches) and incorporates physical constraints through different derivation states [23]. Rather than simply indicating the start and end of rings and branches as SMILES does, SELFIES represents these structural elements by their length, with subsequent symbols interpreted as numbers specifying the size of the feature [23]. This approach eliminates the syntactic and semantic errors common in SMILES-based generative models.

Advanced Representation: Group SELFIES

Group SELFIES builds upon the robust foundation of SELFIES while incorporating higher-level chemical intuition through group tokens that represent functional groups or entire substructures [24]. This representation maintains the chemical robustness guarantees of SELFIES while adding flexibility through fragment-based tokens that capture meaningful chemical motifs. Similar to how human chemists think in terms of substructures rather than individual atoms, Group SELFIES enables machines to operate at a more conceptually relevant level of chemical organization [24]. The representation includes specialized tokens: [X] for adding atoms with atomic symbol X, [Branch] for creating new branches, [pop] for exiting branches, and [RingX] for forming ring bonds [24]. This approach demonstrates improved distribution learning of common molecular datasets and enhances the quality of molecules generated through random sampling compared to regular SELFIES strings [24].

Table 1: Comparison of Fundamental Characteristics of Molecular Representations

| Feature | SMILES | SELFIES | Group SELFIES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Robustness | No guarantee of validity | 100% robust - always valid molecules | 100% robust - always valid molecules |

| Representation Level | Atomic | Atomic | Fragment-based |

| Substructure Control | No | No | Yes |

| Extended Chirality Support | No | No | Yes |

| Human Readability | High | Moderate | Moderate |

| Implementation Complexity | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Grammar Type | Line notation | Formal grammar (Chomsky type-2) | Extended formal grammar |

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Experimental evaluations of molecular representations consistently demonstrate the performance advantages of SELFIES and Group SELFIES over traditional SMILES notation, particularly in downstream classification tasks and generative modeling. In comprehensive studies comparing tokenization approaches for chemical language models, SELFIES representations with specialized tokenization methods have shown significant improvements in classification accuracy across critical biophysics and physiology datasets [22].

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Molecular Representations in Classification Tasks

| Representation | HIV Dataset (ROC-AUC) | Toxicology Dataset (ROC-AUC) | Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration (ROC-AUC) | Tokenization Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMILES | 0.815 | 0.782 | 0.801 | Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) |

| SMILES | 0.863 | 0.834 | 0.857 | Atom Pair Encoding (APE) |

| SELFIES | 0.829 | 0.791 | 0.812 | Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) |

| SELFIES | 0.851 | 0.826 | 0.843 | Atom Pair Encoding (APE) |

| Group SELFIES | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Note: N/A indicates specific quantitative data not available in search results, though Group SELFIES demonstrates improved distribution learning [24]

Recent research exploring augmented SELFIES for molecular property prediction has revealed statistically significant improvements over SMILES representations, with a 5.97% improvement for classical models and a 5.91% improvement for hybrid quantum-classical models [25]. These enhancements are particularly valuable in drug development contexts where accurately identifying molecular properties and potential side effects is crucial for preventing costly late-stage failures [25].

Generative Performance and Distribution Learning

In generative tasks, the robustness of SELFIES and Group SELFIES translates to substantial practical advantages. When used in variational autoencoders (VAEs), SELFIES-based models demonstrate a latent space that is denser by two orders of magnitude compared to SMILES, enabling more comprehensive exploration of chemical space during optimization procedures [22]. The guaranteed validity of all SELFIES strings eliminates the need for complex validity checks or architectural workarounds that often plague SMILES-based generative models [23].

Group SELFIES further enhances generative performance by incorporating meaningful chemical fragments as inductive biases. Experiments demonstrate that Group SELFIES improves distribution learning of common molecular datasets and enhances the quality of molecules generated through random sampling compared to regular SELFIES strings [24]. The fragment-based approach enables more efficient exploration of chemical space while maintaining relevance to synthesizable, functionally meaningful regions of molecular diversity.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Evaluation Framework

The experimental protocols for evaluating molecular representations typically follow standardized benchmarking frameworks to ensure fair comparisons across different representations and models. The MoleculeNet benchmark serves as a comprehensive evaluation resource, curating datasets spanning quantum mechanics, physical chemistry, biophysics, and physiology [25]. For polymer property prediction tasks, established evaluation metrics include:

- ROC-AUC (Receiver Operating Characteristic - Area Under Curve): Particularly valuable for evaluating models trained on imbalanced datasets, as it accounts for the classifier's ability to correctly identify positive instances while avoiding misclassifying negative instances [25].

- Validation Rate: Critical for generative models, measuring the percentage of generated strings that correspond to valid molecular structures.

- Novelty and Diversity: Assessing the ability of representations to generate novel structures not present in training data while maintaining chemical diversity.

The Side Effect Resource (SIDER) dataset provides specific benchmarking for pharmaceutical applications, compiling known drug side effects information from various sources with side effects classified according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) [25]. This enables systematic analysis and model training for predicting adverse drug reactions based on molecular properties.

Tokenization Methods and Model Architectures

The performance of molecular representations is significantly influenced by the choice of tokenization methods and model architectures. Research comparing SMILES and SELFIES tokenization has identified several key approaches:

- Byte Pair Encoding (BPE): A subword tokenization algorithm that iteratively merges the most frequent pairs of bytes or characters, adapted from natural language processing for chemical languages [22].

- Atom Pair Encoding (APE): A novel tokenization approach specifically designed for chemical languages that preserves the integrity and contextual relationships among chemical elements, significantly enhancing classification accuracy compared to BPE [22].

- Model Architectures: Chemical language models typically employ transformer-based architectures (such as BERT), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, or hybrid quantum-classical approaches like Quantum Kernel-Based LSTM (QK-LSTM) [22] [25].

Robustness Testing Protocols

Experimental validation of representation robustness follows specific protocols to stress-test each format's reliability under generative conditions:

- Random Mutation Analysis: Applying random edits (add, replace, delete) to molecular strings and measuring the percentage of resulting strings that correspond to valid molecules [23] [24].

- Latent Space Interpolation: Mapping molecular structures to continuous latent representations in variational autoencoders and examining the validity of structures generated through interpolation between points [23].

- Genetic Algorithm Applications: Implementing evolutionary strategies with string-level mutations as genetic operations and tracking validity rates across generations [24].

These protocols consistently demonstrate that while SMILES representations frequently generate invalid structures when mutated, SELFIES and Group SELFIES maintain 100% validity across all mutation types [23].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of molecular representations for AI-driven polymer research requires specific computational tools and resources. The following table details key research "reagents" and their functions in experimental workflows.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Molecular Representation Experiments

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| SELFIES Python Library | Software Library | Encoding/decoding SELFIES strings | pip install selfies [23] |

| Group SELFIES Library | Software Library | Working with Group SELFIES representations | GitHub: aspuru-guzik-group/group-selfies [24] |

| MoleculeNet | Benchmark Dataset | Standardized evaluation across multiple chemical tasks | Curated datasets for fair comparison [25] |

| SIDER Dataset | Specialized Dataset | Side effect prediction for pharmaceutical applications | Binary classification of drug side effects [25] |

| BERT-based Transformers | Model Architecture | Chemical language processing with attention mechanisms | Adapted from NLP with chemical tokenization [22] |

| QK-LSTM | Model Architecture | Hybrid quantum-classical sequence modeling | Quantum kernels integrated with LSTM [25] |

| STONED Algorithm | Generative Method | Combinatorial exploration of chemical space | SELFIES-based efficient molecular generation [23] |

Integration in Polymer Informatics Workflow

The role of molecular representations extends beyond standalone applications to integrated workflows in polymer informatics. AI-driven polymer discovery typically follows an iterative cycle beginning with target property definition, followed by machine learning model training, molecular generation, and experimental validation [6]. In this workflow, molecular representations serve as the fundamental encoding that enables each step:

Industrial applications of these workflows are already demonstrating tangible success. Researchers at Georgia Tech have used AI-driven approaches to discover new polymer classes for capacitive energy storage, with designed materials undergoing successful laboratory synthesis and testing [6] [21]. The integration of molecular representations with AI prediction models has enabled "virtual screening" of polymer structures before commitment to resource-intensive synthesis, significantly accelerating the discovery timeline [6].

The evolution of molecular representations continues with emerging research directions extending the capabilities of existing formats. Augmented SELFIES approaches are showing promise for enhancing molecular property prediction, though their potential impact in quantum machine learning domains remains unexplored [25]. The development of learned grammars that automatically extract useful production rules from molecular datasets represents another frontier, potentially creating even more efficient representations tailored to specific polymer classes or applications [24].

The integration of explainable AI (XAI) techniques with molecular representations addresses the critical challenge of interpretability in AI-driven polymer science [26]. By making model decisions interpretable, these approaches build trust among researchers and ensure that machine-generated hypotheses can be critically evaluated against chemical knowledge and intuition [26]. This is particularly important as the field moves toward self-driving laboratories where AI systems autonomously design, execute, and analyze polymer synthesis with minimal human intervention [26] [27].

In conclusion, the choice of molecular representation significantly impacts the effectiveness of AI-driven polymer property prediction and discovery. While SMILES offers simplicity and human readability, its limitations in robustness make it less suitable for generative applications. SELFIES addresses these limitations with guaranteed validity, while Group SELFIES incorporates valuable chemical intuition through fragment-based tokens. As polymer informatics continues to evolve, these representations will play an increasingly central role in enabling the rapid discovery of novel polymers with tailored properties for energy, healthcare, and sustainability applications.

The discovery and development of novel polymers have traditionally been slow, resource-intensive processes hampered by the vastness of polymer chemical space. Conventional methods, which heavily rely on researcher intuition and trial-and-error experimentation, struggle to efficiently navigate this complex design landscape [20]. The emerging field of polymer informatics seeks to address these challenges through data-driven approaches, with machine learning (ML) models increasingly deployed to predict polymer properties from chemical structures [28] [29]. However, these pipelines often depend on handcrafted molecular fingerprints—numerical representations of chemical structures—which require significant domain expertise, are tedious to develop, and may lack generalizability across diverse polymer classes [29].

Foundation models, pre-trained on vast datasets, represent a transformative shift in this domain. Adapted from natural language processing (NLP), these models treat chemical representations as a language to be learned [30] [29]. This paradigm enables fully machine-driven pipelines that can automatically generate informative chemical representations, dramatically accelerating both the prediction of polymer properties and the generative design of novel polymers [30] [29]. This article focuses on polyBART, a pioneering model that establishes new state-of-the-art performance in bidirectional structure-property translation, and benchmarks it against key alternatives in the field, providing researchers with a clear comparison of capabilities, performance, and optimal use cases.

Model Architectures and Core Capabilities

polyBART: A Chemical Linguist for Polymers

polyBART is a language model specifically engineered for polymer informatics. Its core innovation lies in its PSELFIES (Pseudo-polymer SELFIES) representation, which adapts the SELFIES (Self-Referencing Embedded Strings) molecular representation for polymers [30]. The PSELFIES framework converts Polymer SMILES (PSMILES) into a pseudo-molecular SMILES (MSMILES) format by forming cyclic structures and strategically cleaving bonds, marking the new termini with astatine (At) atoms—a rare element in polymer chemistry that avoids confusion with common structures [30]. This representation guarantees 100% syntactic validity, ensuring every generated string corresponds to a chemically plausible polymer [30].

Architecturally, polyBART is based on an encoder-decoder framework (BART) and is developed through continued pre-training of SELFIES-TED, a model originally designed for molecular representations [30]. This strategic approach allows polyBART to leverage chemical priors already learned from the molecular domain. Its most distinctive capability is bidirectional translation, enabling it to not only predict properties from a given structure (the forward problem) but also to generate polymer structures that meet specific property targets (the inverse problem) [30]. This makes polyBART a unifying model for both prediction and generative design.

Alternative Polymer Foundation Models

The landscape of polymer foundation models includes other significant entrants, each with different architectural focuses.

polyBERT: An encoder-only Transformer model based on DeBERTa, polyBERT is a "chemical linguist" that treats polymer SMILES strings as a chemical language [29]. It is pre-trained on a massive dataset of 100 million hypothetical polymers to become an expert in polymer chemical syntax [29]. Unlike polyBART, its primary strength lies in ultrafast property prediction. It generates machine-crafted "Transformer fingerprints" that are then mapped to various properties using a multitask learning framework, outperforming handcrafted fingerprinting methods in speed by two orders of magnitude while maintaining accuracy [29].

General-Purpose LLMs (LLaMA, GPT): Studies have fine-tuned general-purpose large language models (LLMs) like LLaMA-3-8B and GPT-3.5 for polymer property prediction [31]. These models simplify workflows by using natural language inputs (SMILES strings), eliminating the need for explicit fingerprinting [31]. However, benchmarks indicate that while they approach the performance of domain-specific models, they generally underperform in predictive accuracy and efficiency compared to specialized tools like polyGNN or polyBERT, as they lack ingrained, domain-specific chemical knowledge [31].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the core structural and functional differences between these model architectures.

Experimental Protocols and Performance Benchmarking

Key Methodologies for Model Validation

Rigorous experimental protocols are essential for validating the performance of AI models in polymer informatics. The following methodologies are commonly employed in the field:

polyBART's Training and Validation: polyBART was developed via continued pre-training of the SELFIES-TED model on polymer-specific data represented in the novel PSELFIES format [30]. Its validation was notably comprehensive, involving both computational benchmarks and real-world laboratory synthesis [30]. A polymer designed by polyBART was synthesized, and its predicted high thermal degradation temperature was confirmed through experimental measurement, marking one of the first successful syntheses of a language-model-designed polymer [30] [6].

Benchmarking General LLMs: In a study benchmarking LLMs for polymer property predictions, models like LLaMA-3-8B and GPT-3.5 were fine-tuned on a curated dataset of 11,740 data entries for thermal properties (glass transition, melting, and decomposition temperatures) [31]. The study used parameter-efficient fine-tuning and hyperparameter optimization, comparing their performance against traditional fingerprint-based approaches (Polymer Genome, polyGNN) and domain-specific language models (polyBERT) under both single-task and multi-task learning settings [31].

SMILES-PPDCPOA Model: Another relevant deep learning approach, though not a foundation model in the same sense, is the SMILES-PPDCPOA model. It integrates a 1D Convolutional Neural Network (1D-CNN) with a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) to capture both local substructures and long-range dependencies in SMILES strings [32]. The model is optimized using a Pareto Optimization Algorithm (POA) for hyperparameter tuning and was evaluated on its ability to classify polymers into property categories with high accuracy [32].

Comparative Performance Data

The table below synthesizes key performance metrics for polyBART and alternative models, highlighting their effectiveness in property prediction and generative design.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarking of Polymer AI Models

| Model | Primary Function | Key Properties Predicted | Performance Highlights | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| polyBART [30] | Bidirectional Structure-Property Translation | Thermal degradation temperature, properties for electrostatic energy storage | Successfully guided the synthesis of a novel polymer with validated high thermal degradation temperature. | Unifying model for prediction & design; 100% valid generation via PSELFIES. |

| polyBERT [29] | Property Prediction | Glass transition temp ((Tg)), Melting temp ((Tm)), Degradation temp ((Td)), Band gap ((Eg)) | Ultrafast prediction speed (2 orders of magnitude faster than handcrafted fingerprints) while preserving accuracy. | Machine-crafted fingerprints; End-to-end pipeline; Superior for high-throughput screening. |

| LLaMA-3-8B (Fine-tuned) [31] | Property Prediction | Glass transition, Melting, and Decomposition temperatures | Approaches but generally underperforms traditional fingerprinting methods in predictive accuracy. | Simplifies workflow by using natural language SMILES inputs. |

| SMILES-PPDCPOA [32] | Property Classification | Bandgap, Dielectric Constant, Refractive Index, etc. | 98.66% average classification accuracy across eight property classes. | Hybrid 1D-CNN-GRU captures local & global features; High accuracy for classification. |

A critical finding from benchmarking studies is that single-task learning often proves more effective than multi-task learning for LLMs in this domain, as these models can struggle to capture cross-property correlations—a noted strength of traditional multi-task methods like polyGNN [31]. Furthermore, analysis of molecular embeddings suggests that general-purpose LLMs have limitations in representing nuanced chemo-structural information compared to the handcrafted features or domain-specific embeddings used by models like polyBERT [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

For researchers aiming to implement or validate polymer foundation models, a set of core components and resources is essential. The following table details key "research reagents" in this computational domain.

Table 2: Essential Tools and Resources for Polymer Foundation Model Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research | Relevance to Experiments |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSMILES (Polymer SMILES) [30] [29] | Data Representation | A string-based notation system for representing polymer repeat units with terminal endpoints marked by [*]. | Serves as the fundamental "language" or input for training and using models like polyBERT and polyBART. |

| PSELFIES (Pseudo-polymer SELFIES) [30] | Data Representation | A novel representation that guarantees 100% syntactically valid polymer structures, derived from PSMILES. | Critical for polyBART's generative capabilities, ensuring all model outputs are chemically plausible. |

| Hugging Face Transformers Library [33] | Software Library | A Python library providing thousands of pre-trained models, including architectures like BART and BERT. | Facilitates the loading, fine-tuning, and deployment of transformer-based foundation models. |

| RDKit [29] | Cheminformatics Toolkit | An open-source toolkit for cheminformatics and machine learning, including SMILES processing and fingerprinting. | Used for data pre-processing, canonicalization of SMILES strings, and generating traditional fingerprints for benchmarking. |

| Polymer Datasets [30] [29] [20] | Data | Curated collections of polymer structures and properties (e.g., from PolyInfo). | Provides the essential training and validation data for fine-tuning models and benchmarking performance. |

The advent of polymer foundation models like polyBART and polyBERT marks a significant leap beyond traditional polymer informatics. polyBART, with its unique bidirectional capabilities, addresses the complete materials discovery cycle, from property prediction to generative design, and has begun the critical transition from in-silico prediction to validated physical reality [30] [6]. Benchmarking data confirms that while general-purpose LLMs offer simplified workflows, domain-specific models currently hold a decisive edge in predictive accuracy and efficiency for specialized polymer tasks [31].