The Conduction Mechanism of Organic Polymers: From Fundamental Concepts to Advanced Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the electrical conduction mechanisms in organic polymers, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The Conduction Mechanism of Organic Polymers: From Fundamental Concepts to Advanced Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the electrical conduction mechanisms in organic polymers, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It begins by establishing the foundational principles of conjugated electron systems and doping, detailing how these materials transition from insulators to conductors. The scope extends to advanced synthesis methodologies, characterization techniques, and the vast application landscape, with a particular emphasis on drug delivery systems, neural interfaces, and tissue engineering. The content further addresses current performance limitations and optimization strategies, including molecular engineering and compositing, and concludes with a comparative analysis of material properties and validation protocols essential for clinical translation. This review serves as a critical resource for leveraging the unique properties of conductive polymers in next-generation biomedical technologies.

Unraveling the Core Principles: The Electronic Structure and Conduction Mechanisms of Organic Polymers

The field of polymer science was fundamentally transformed by the groundbreaking discovery that organic polymers, traditionally classified as insulators, could exhibit metallic levels of electrical conductivity. This paradigm shift challenged long-held scientific beliefs and initiated a new era of materials research. Prior to the 1970s, polymers were universally considered to be electrical insulators, a dogma that was overturned by the pioneering work on polyacetylene [1]. The enhancement of polyacetylene's conductivity by a factor of one million through doping revealed the vast potential of this new material class [2]. This revolutionary finding earned Hideki Shirakawa, Alan MacDiarmid, and Alan Heeger the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2000, firmly establishing conductive polymers as a distinct scientific field [1].

These conducting organic polymers combine the electrical properties of metals and semiconductors with the mechanical flexibility, processing advantages, and reduced environmental impact of conventional polymers [3] [1]. This unique combination of properties has enabled their application across diverse fields including energy storage, optoelectronics, sensing, and biomedicine [3] [2] [1]. This review provides a comprehensive technical examination of conducting polymers, exploring their fundamental conduction mechanisms, synthesis methodologies, and advanced applications, with particular emphasis on their growing importance in biomedical research and drug development.

Fundamental Conduction Mechanisms

The electrical behavior of conducting polymers stems from their unique molecular architecture, which differs fundamentally from both traditional polymers and inorganic semiconductors.

Chemical Structure and Backbone Conjugation

At the core of every conducting polymer is a conjugated carbon chain consisting of alternating single (σ) and double (π) bonds [2] [1]. This conjugation creates a system of highly delocalized π-electrons that can move along the polymer backbone, providing the pathway for electrical conductivity [1]. The degree of conjugation and the overall chain length are critical factors determining the electrical and optical properties of the material [1]. In their undoped state, conjugated polymers behave as anisotropic, quasi-one-dimensional electronic structures with moderate bandgaps of 2–3 eV, characteristic of semiconductors [2].

Doping and Charge Carrier Generation

A pivotal breakthrough in understanding conducting polymers was the discovery that doping processes could dramatically enhance their electrical conductivity by several orders of magnitude [2]. Doping introduces additional charge carriers—either electrons (n-type) or holes (p-type)—into the polymer matrix [1]. This process generates quasi-particles that facilitate charge transport along and between polymer chains [1]. Unlike inorganic semiconductors, doping in conducting polymers does not involve atomic substitution but rather a redox reaction that changes the oxidation state of the polymer backbone [2].

When conjugated polymers undergo doping or photoexcitation, the π-bond system becomes self-localized, leading to nonlinear excitation states that enable the transition from insulating to metallic behavior [2]. The primary charge carriers in conducting polymers include:

- Polarons: Radical cations or anions associated with a local structural distortion, extending over several polymer units.

- Bipolarons: Spinless dications or dianions formed by the interaction of two polarons.

- Solitons: Unique to polymers with degenerate ground states like polyacetylene, these are domain walls between phases of different bond alternation.

Table 1: Charge Carriers in Conducting Polymers and Their Characteristics

| Charge Carrier | Spin | Charge | Formation Energy | Stability | Primary Polymer Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polaron | 1/2 | +e or -e | Moderate | Medium | PANI, PPy, PEDOT |

| Bipolaron | 0 | +2e or -2e | Lower than two polarons | High | PPy, PTH, PEDOT |

| Soliton | 0 or 1/2 | 0 or ±e | Low | High in PA | Polyacetylene |

The conductivity of conjugated polymers in their pure form ranges from insulators to semiconductors, with conductivity increasing dramatically with dopant concentration [2]. For instance, pristine polyacetylene has a conductivity of approximately 10⁻⁵ S cm⁻¹, but after optimized doping, this can increase to 10² to 10³ S cm⁻¹ [2]. The dopant ions reside in close proximity to the polymer chain without forming direct chemical bonds, influencing not only electrical properties but also mechanical and optical characteristics [2].

Major Conducting Polymer Families and Their Synthesis

Several classes of conducting polymers have been extensively studied, each with distinct structural features and property profiles. The following sections detail the most significant polymer families and their synthesis methodologies.

Polyacetylene and its Derivatives

Polyacetylene represents the prototypical conducting polymer whose investigation led to the Nobel Prize recognition [2]. The polymer consists of a linear polyene chain that can be functionalized through substitution of hydrogen atoms with various pendant groups [2]. Polyacetylene exhibits multifunctional behavior including electrical conductivity, photoconductivity, liquid crystal properties, and chiral recognition capabilities [2].

Multiple synthesis approaches have been developed for polyacetylene:

- Catalytic Polymerization: Using Ziegler-Natta catalysts (Ti(0-n-C₄H₉)₄ and (C₂H₅)₃Al) to produce highly crystalline free-standing films [2]. These catalysts offer high solubility in organic solvents and excellent selectivity [2].

- Luttinger Catalysts: Employing a hybrid reducing agent with a group VIII metal complex (e.g., nickel chloride) to produce high molecular weight polyacetylene without oligomer formation [2]. These catalysts utilize hydrophilic solvents like water-ethanol tetrahydrofuran or acetonitrile [2].

- Electrochemical Polymerization: Anodic oxidation of monomer precursors on inert metal surfaces using techniques such as cyclic voltammetry, potentiostatic, or galvanostatic methods [2]. This approach allows direct deposition of polymer films with controllable thickness through adjustment of electrochemical parameters [2].

- Non-Catalytic Methods: Including ring-opening polymerization of 1,3,5,7-cyclooctatetraene with metathesis catalysts [2] and UV-induced polymerization of acetylene gas [2].

Polyaniline (PANI)

Polyaniline ranks among the most promising and extensively studied conducting polymers due to its high environmental stability, facile processability, and tunable conducting/optical properties [2]. Its conductivity is strongly dependent on dopant concentration and pH, achieving metal-like conductivity only at pH levels below 3 [2].

Polyaniline exists in three distinct oxidation states:

- Leucoemeraldine: Fully reduced state with primarily benzenoid rings.

- Emeraldine: Intermediate oxidation state containing equal ratios of benzenoid and quinoid rings; this is the conductive form.

- Pernigraniline: Fully oxidized state with predominantly quinoid rings.

Table 2: Synthesis Methods for Conducting Polymers

| Synthesis Method | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations | Applicable Polymers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Oxidation | Monomer mixed with oxidizing agent in acid medium | Simple, scalable, ambient conditions | Limited control over structure | PANI, PPy, PTH |

| Electrochemical Polymerization | Anodic oxidation on inert metal surface | Controlled film thickness, direct deposition | Limited to conductive substrates | PPy, PTH, PEDOT |

| Interfacial Polymerization | Reaction at interface of two immiscible liquids | Good molecular weight control | Slow reaction rate | PANI, PPy |

| Electrospinning | Fiber formation under strong electrical field | Produces nano/micro fibrous morphologies | Requires optimized viscosity | PANI, PPy, PEDOT |

| Vapor Phase Synthesis | Monomer polymerization in vapor phase | High purity films | Specialized equipment | PA, PPy |

Synthesis methodologies for polyaniline include:

- Chemical Oxidation: Combining aniline monomers with oxidizing agents (e.g., ammonium persulfate, ceric nitrate, potassium bichromate) in acidic media, with the color change to green indicating polyaniline formation [2].

- Interfacial Polymerization: Conducting polymerization at the interface between organic solvent-containing aniline and aqueous oxidant/dopant solutions [2].

- Electropolymerization: Utilizing electrochemical techniques without external oxidants [2].

- Electrospinning: Creating fibrous polymer morphologies with nano or micro diameters under strong electrical fields [2].

Other Significant Conducting Polymers

Beyond polyacetylene and polyaniline, several other conducting polymers have gained significant attention:

- Polypyrrole (PPy): Noted for its excellent environmental stability and relatively straightforward synthesis, making it valuable for biomedical applications including biosensors and artificial muscles [1].

- Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT): Particularly in its commercial form PEDOT:PSS, widely used in flexible electronics and transparent conductive films due to its aqueous processability and stable dispersion [1].

- Polythiophene (PT) and Derivatives: Including Poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT), central to organic electronics, especially organic solar cells and field-effect transistors [1].

- Poly(p-phenylene vinylene) (PPV): Primarily utilized in light-emitting technologies due to its semiconducting and electroluminescent properties [1].

Advanced Applications in Research and Medicine

The unique properties of conducting polymers have enabled their deployment across remarkable diverse applications, with particularly significant advances in biomedical fields.

Energy Storage and Conversion

Conducting polymers play crucial roles in advanced energy systems including supercapacitors, batteries, and solar cells [3] [1]. Their rapid redox switching capabilities, high surface area, and tunable conductivity make them ideal for electrochemical energy storage devices [2]. Publication trends indicate strong alignment between research articles and patents in this domain, reflecting active commercial development [1].

Biomedical Applications

Conducting polymers have undergone explosive growth in biomedical applications, with journal articles comprising 67% and patent families representing 32% of publications, indicating a research-dominated field with substantial commercialization potential [1].

Table 3: Biomedical Applications of Conducting Polymers

| Application Area | Key Polymers | Primary Functions | Research/Patent Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biosensors | PPy, PEDOT, PANI, PT | Biomarker detection, signal transduction | Highest volume |

| Neural Interfaces | PEDOT, PPy | Neural recording/stimulation, tissue integration | High |

| Artificial Muscles | PA, PPy | Actuation, biomimetic movement | High patent-to-journal ratio |

| Drug/Gene Delivery | PPV, PPP, PPS, PF | Electrically-triggered release | Emerging |

| Antimicrobial Coatings | PANI, PT, PFu | Infection control on implants | High patent-to-journal ratio |

| Tissue Engineering | PPy, PEDOT | Conductive scaffolds, cell growth stimulation | Early research |

Key biomedical applications include:

- Biosensing: Conducting polymers form the foundation of advanced biosensors that enable real-time, sensitive biomarker monitoring [1]. Their electrical properties change in response to biological interactions, facilitating detection of various analytes.

- Neural Interfaces: These materials enable advanced electrodes and implants that seamlessly integrate with neural tissue for applications including neural stimulation, cochlear implants, and retinal prosthetics [1].

- Artificial Muscles and Implantable Prosthetics: Conducting polymers can closely mimic natural muscle movements and facilitate intuitive, brain-controlled prosthetics through seamless neural integration [1].

- Drug and Gene Delivery Systems: Conductive polymers allow electrically triggered, localized therapeutic release, enabling precise spatial and temporal control over drug administration [1].

- Antimicrobial Coatings: Certain conducting polymers provide active surfaces that disrupt microbial growth and reduce infection risks on implants and medical devices [1].

- Tissue Engineering: Conductive polymers serve as scaffolds that stimulate cell growth and regeneration through electrical signaling, particularly for electrically responsive tissues like nerve and muscle [1].

Recent Breakthrough: Complementary Internal Ion-Gated Organic Electrochemical Transistors (cIGTs)

A groundbreaking 2025 study demonstrated that spatial control of doping in conducting polymers enables creation of complementary, conformable, implantable internal ion-gated organic electrochemical transistors (cIGTs) [4]. This innovation addresses a fundamental challenge in organic electronics: the requirement for separate materials to create n-type and p-type transistors [4].

The research discovered that introducing source/drain contact asymmetry enables spatial control of dedoping and creation of single-material complementary organic transistors from various conducting polymers [4]. By making the drain contact area smaller than the source contact area, researchers achieved significantly enhanced saturation in the 3rd quadrant operation [4]. This geometrical control preferentially dedopes the channel region near the smallest contact, creating directional control of channel current [4].

This approach has enabled the development of high-performance conformable amplifiers with 200 V/V uniform gain and 2 MHz bandwidth, demonstrating long-term in vivo stability and allowing implantation in developing rodents to monitor network maturation [4]. This breakthrough significantly expands the potential of organic electronics in standard circuit designs and enhances their biomedical applications [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Chemical Oxidation Synthesis of Polyaniline

Materials Required:

- Aniline monomer

- Oxidizing agent (typically ammonium persulfate)

- Dopant acid (HCl, H₂SO₄, or others)

- Solvent system (aqueous)

Procedure:

- Purify aniline monomer through distillation under reduced pressure.

- Prepare 0.2M aniline solution in 1M dopant acid.

- Prepare 0.2M ammonium persulfate solution in the same acid concentration.

- Cool both solutions to 0-5°C to control exothermic reaction.

- Slowly add oxidant solution to monomer solution with constant stirring.

- Maintain reaction temperature below 10°C during initial mixing.

- Allow reaction to proceed for 4-24 hours with continuous stirring.

- Observe color change to dark green indicating polyaniline formation.

- Filter the precipitate and wash repeatedly with acid solution.

- Dry under dynamic vacuum at 40-60°C for 24 hours.

Critical Parameters:

- Monomer-to-oxidant ratio significantly affects molecular weight and conductivity.

- Acid concentration determines doping level and ultimate conductivity.

- Temperature control is crucial to prevent over-oxidation and branching.

- Reaction time influences polymer chain length and properties.

Electrochemical Polymerization of Polypyrrole

Materials Required:

- Pyrrole monomer

- Supporting electrolyte (LiClO₄, TBAPF₆, or pTSA)

- Solvent (acetonitrile, propylene carbonate, or aqueous)

- Working electrode (Pt, Au, or ITO)

- Counter electrode (Pt mesh)

- Reference electrode (Ag/AgCl)

Procedure:

- Purify pyrrole monomer through distillation or passage through alumina column.

- Prepare electrolyte solution (0.1M) in chosen solvent.

- Add pyrrole monomer to achieve 0.05-0.1M concentration.

- Deoxygenate solution by bubbling with inert gas (N₂ or Ar).

- Set up three-electrode electrochemical cell.

- Apply potential using one of several methods:

- Potentiostatic: Constant potential of 0.7-0.9 V vs. Ag/AgCl

- Galvanostatic: Constant current density of 0.1-1.0 mA/cm²

- Cyclic Voltammetry: Scanning between -0.2 and 0.8 V at 10-50 mV/s

- Continue polymerization until desired film thickness is achieved.

- Remove electrode, rinse thoroughly with solvent to remove oligomers and electrolyte.

- Dry under inert atmosphere.

Critical Parameters:

- Electrolyte type determines incorporated dopant and film properties.

- Applied potential/current controls nucleation density and film morphology.

- Solvent choice affects polymer chain conformation and conductivity.

- Monomer concentration influences growth kinetics and film quality.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Conducting Polymer Research

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS | Transparent conductive films, neural interfaces | Aqueous processability, high conductivity, biocompatibility | Clevios PH1000, Orgacon EL-P5015 |

| Polyaniline (PANI) | Biosensors, anticorrosion coatings | pH-dependent conductivity, environmental stability | Emeraldine salt form for conductivity |

| Polypyrrole (PPy) | Artificial muscles, drug delivery | Good biocompatibility, redox activity | Often combined with PSS dopant |

| Poly(3-hexylthiophene) | Organic photovoltaics, OFETs | Solution processability, charge transport | Regioregular P3HT for high performance |

| Ziegler-Natta Catalyst | Polyacetylene synthesis | High stereospecificity, crystalline products | Ti(OBu)₄/AlEt₃ combination |

| Ammonium Persulfate | Chemical oxidation polymerization | Strong oxidizing agent, water solubility | Standard oxidant for PANI and PPy |

| Lithium Perchlorate | Electrolyte for electrochemical synthesis | High conductivity, wide potential window | Common electrolyte for PPy deposition |

| Indium Tin Oxide (ITO) | Electrode substrate | Transparency, conductivity | Standard for optoelectronic devices |

| Dodecylbenzenesulfonate | Surfactant dopant | Improves processability, conductivity | Template for nanostructured polymers |

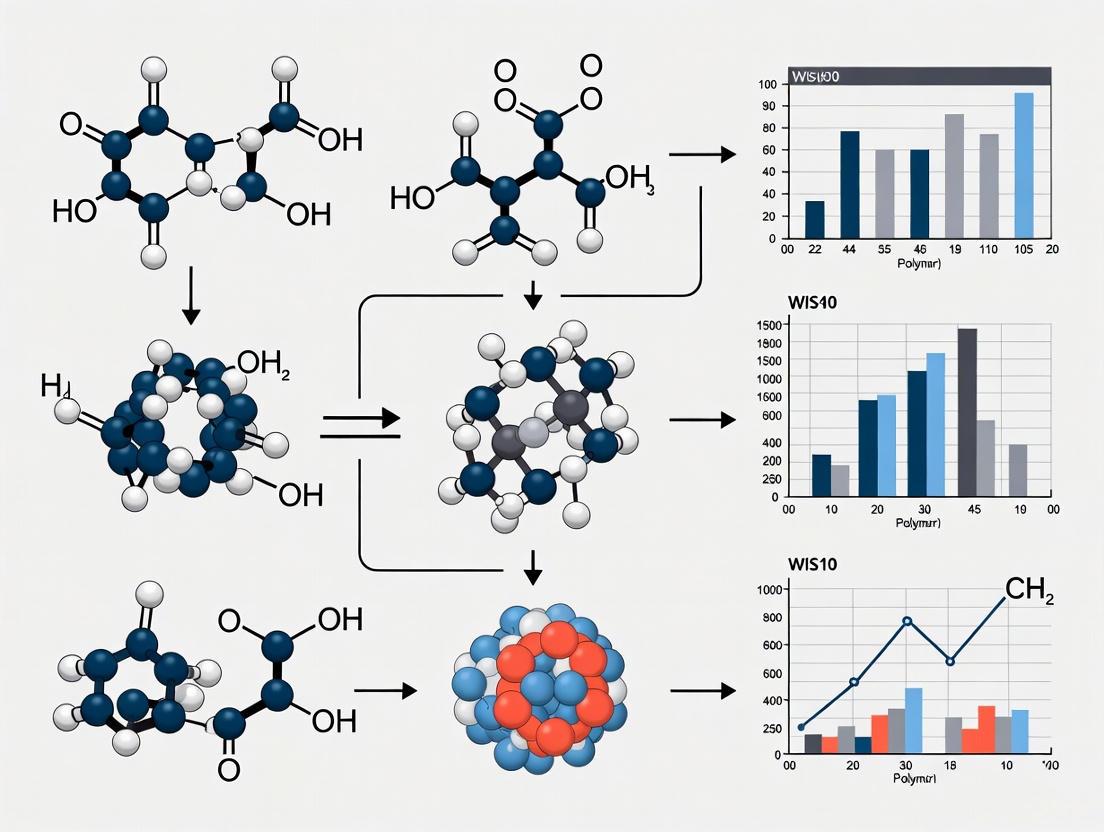

Visualizations

Historical Development and Mechanism Evolution

Doping Mechanism and Charge Transport

The historical breakthrough from insulating polymers to conducting materials represents a paradigm shift in materials science that continues to evolve more than four decades after its initial discovery. From the fundamental understanding of conduction mechanisms in conjugated systems to the recent innovation of spatially controlled doping for complementary organic transistors, the field has demonstrated remarkable scientific vitality and practical relevance. The unique combination of electronic functionality, mechanical flexibility, biocompatibility, and environmental sustainability positions conducting polymers as enabling materials for next-generation technologies, particularly in biomedical applications where they facilitate seamless integration between electronic devices and biological systems. As research addresses remaining challenges related to long-term stability, biocompatibility, and processing scalability, conducting polymers are poised to play increasingly significant roles across energy, electronics, and medicine, fulfilling the promise envisioned by their pioneering discoverers.

The discovery that organic polymers can conduct electricity marked a paradigm shift in materials science, transforming polymers from traditional insulators into a unique class of semiconductors and conductors [5]. This conductivity arises from a fundamental structural feature: the conjugated backbone [6]. Conjugated polymers represent a distinct class of organic materials characterized by a backbone of alternating single and double bonds, which enables π-electron delocalization along the polymer chain [7] [5]. This delocalization forms the foundation of their electrical conductivity, allowing them to combine the electronic properties of metals or semiconductors with the mechanical flexibility, lightweight nature, and processability of conventional polymers [5] [8]. The pioneering work on polyacetylene, which demonstrated metallic conductivity upon doping, laid the groundwork for this field and was recognized with the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2000 [7] [5]. This review explores the fundamental principles of π-electron delocalization in conjugated backbones, its characterization, and its critical role in enabling conductivity in organic polymers.

Electronic Structure and the Origin of Delocalization

Atomic Orbital Hybridization and Bond Formation

The electronic structure of conjugated polymers fundamentally differs from that of non-conjugated polymers due to a specific type of atomic orbital hybridization [6].

- In non-conjugated polymers (e.g., polyethylene), carbon atoms in the polymer backbone are

sp^3hybridized. Each carbon atom forms four covalent σ-bonds with adjacent atoms, resulting in all electrons being strongly localized in these single bonds. The absence of delocalized electrons and a large electronic band gap (around 8 eV for polyethylene) renders these materials electrically insulating [6]. - In conjugated polymers (e.g., polyacetylene), carbon atoms are

sp^2hybridized. Each carbon atom forms three covalent σ-bonds with its neighbors, creating the structural backbone. The remaining unhybridized2p_zatomic orbital, which contains one electron, lies orthogonal to the σ-bond plane. The parallel overlap of these adjacent2p_zorbitals leads to the formation of π-bonds [6].

The following diagram illustrates the electronic structure and the resulting energy bands in a conjugated system.

From π-Bonds to Delocalized Electron Clouds

The continuous overlap of 2p_z orbitals along the polymer backbone leads to the formation of a delocalized π-electron cloud above and below the plane of the σ-bonded backbone [6]. This delocalization means that the π-electrons are not fixed between two specific carbon atoms but are shared and can move freely along the entire conjugated chain. This creates a system of molecular orbitals that extend across multiple atoms. The highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) are the most significant, as electronic transitions between these levels govern the material's optoelectronic properties [7]. The energy difference between the HOMO and LUMO is the band gap ((E_g)), a critical parameter determining the intrinsic conductivity and optical characteristics of the semiconductor [6]. The planar configuration of the backbone maximizes π-orbital overlap, thereby enhancing this delocalization and establishing efficient conductive pathways for charge carriers [7].

Charge Transport Mechanisms in Conjugated Systems

Electrical conductivity in conjugated polymers requires both the presence of charge carriers and their ability to move through the material. The delocalized π-system provides the pathway, but conduction involves two primary mechanisms:

- Intra-chain Transport: Charge carriers (electrons or holes) move along the length of an individual polymer chain through the delocalized π-system. The efficiency of this transport depends on the conformational planarity of the backbone; twists or kinks can localize charges and hinder movement [7].

- Inter-chain Transport: Charge carriers "hop" between adjacent polymer chains. This process is facilitated by π-π stacking interactions, where the delocalized electron clouds of neighboring chains interact, enabling charge transfer across chains [7]. The degree of molecular order and crystallinity in the material significantly influences this hopping efficiency.

The following table summarizes key parameters and their influence on charge transport.

Table 1: Key Parameters Influencing Charge Transport in Conjugated Polymers

| Parameter | Description | Impact on Conductivity |

|---|---|---|

| Band Gap ((E_g)) | Energy difference between HOMO and LUMO levels [7]. | A lower band gap facilitates the thermal or optical generation of charge carriers, leading to higher intrinsic conductivity. |

| Degree of Delocalization | The spatial extent over which π-electrons are shared along the backbone. | Enhanced delocalization, achieved through planar backbones and D-A interactions, improves intra-chain charge mobility [7]. |

| π-π Stacking Distance | The distance between conjugated backbones of adjacent chains in the solid state. | A shorter stacking distance enhances electronic coupling between chains, promoting efficient inter-chain charge hopping [7]. |

| Charge Carrier Mobility | A measure of how quickly a charge carrier can move through the material under an electric field. | Directly proportional to the electrical conductivity. High mobility requires both efficient intra-chain and inter-chain transport pathways. |

Experimental Characterization of the Conjugated Backbone

Verifying the structure and electronic properties of the conjugated backbone is crucial for material development. The table below outlines standard experimental techniques used for characterization.

Table 2: Experimental Techniques for Characterizing Conjugated Backbones

| Technique | Information Obtained | Experimental Protocol Summary |

|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis-NIR Spectroscopy | Optical Band Gap: Determined from the absorption edge [6]. Electronic Transitions: Reveals π-π* transitions and evidence of low-bandgap design from D-A structures [7]. | Dissolve or disperse the polymer in a suitable solvent. Measure absorption spectrum from UV to NIR. Tauc plot analysis of the absorption edge yields the optical band gap. |

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Electrochemical Band Gap: Estimated from oxidation (HOMO) and reduction (LUMO) onset potentials [7]. Redox Activity: Assesses the doping/dedoping process and electrochemical stability. | Prepare a thin film on a working electrode (e.g., ITO, glassy carbon). Scan potential in an electrolyte solution using a standard 3-electrode setup. Record current response vs. applied potential. |

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | Molecular Packing: Reveals π-π stacking distance and long-range order from diffraction patterns [9]. Crystallinity. | For powders or thin films, expose to X-rays and measure diffraction angles. Analyze peak positions (e.g., (010) reflection for π-π stacking) to calculate d-spacings [9]. Grazing-Incidence XRD (GIXRD) is used for thin films. |

| Vibrational Spectroscopy (Raman/FTIR) | Backbone Structure: Confirms presence of conjugated double bonds and molecular structure. Doping Level: Can identify charge carriers like polarons and bipolarons. | Illuminate solid sample with laser (Raman) or IR light (FTIR). Analyze the scattered/transmitted light to obtain vibrational spectrum, which is sensitive to bonding and electronic structure. |

Backbone Engineering for Enhanced Conductivity

Molecular design allows for precise tuning of the conjugated backbone's properties. Two primary strategies are employed:

Backbone Modification and Donor-Acceptor Design

A highly effective strategy for reducing the band gap and enhancing intramolecular charge transfer is the Donor-Acceptor (D-A) approach [7]. This involves synthesizing a copolymer backbone with alternating electron-rich (donor) and electron-deficient (acceptor) units. The electronic interaction between these units facilitates π-electron delocalization, leading to a quinoid mesomeric structure along the polymer chain and a significantly reduced bandgap compared to homopolymers [7]. Furthermore, strategic substitution with atoms like fluorine or chlorine can fine-tune the energy levels (HOMO/LUMO) of the backbone, optimizing it for specific applications [7].

Side-Chain Engineering

While not part of the conjugated backbone itself, side-chain engineering is critical for modulating the properties of the backbone and the overall material. Attaching alkyl or other functional groups as side chains can:

- Improve Solubility and Processability: Enabling solution-based fabrication techniques [7].

- Influence Molecular Packing: The size, shape, and branching of side chains can control the π-π stacking distance and overall solid-state order, directly impacting inter-chain charge transport [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Research and development in conjugated polymers rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components used in the synthesis and processing of these materials.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Conjugated Polymer Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| 3,4-Ethylenedioxythiophene (EDOT) | Monomer for synthesizing the widely used conjugated polymer PEDOT [5] [8]. | Served as the precursor for PEDOT:PSS, a transparent conductive polymer used in organic electronics and photovoltaics [5] [6]. |

| Aniline | Monomer for the chemical or electrochemical synthesis of Polyaniline (PANI) [8]. | Oxidative polymerization of aniline produces PANI, which is explored for applications in batteries, supercapacitors, and sensors [5] [8]. |

| Iron(III) Chloride (FeCl₃) | A common chemical oxidizing agent for polymerization. | Used in the oxidative polymerization of monomers like pyrrole and thiophene, converting them into conductive polypyrrole (PPy) and polythiophene (PTh) [5]. |

| Polystyrene sulfonate (PSS) | A polymeric counter-ion and dopant used to stabilize and disperse conductive polymers. | Forms a complex with PEDOT (PEDOT:PSS), which is water-dispersible and widely used as a transparent electrode or hole-injection layer [5] [9]. |

| Dimethylformamide (DMF) | A polar aprotic solvent with high boiling point. | Used for processing various conjugated polymers and coordination complexes (e.g., Ni-BAND), facilitating thin film formation via spin-coating [9]. |

Advanced Concepts: Mixed Conduction and Proton-Electron Coupling

Beyond pure electronic conduction, some conjugated materials are designed to transport both ions and electrons, functioning as Mixed Ionic-Electronic Conductors (MIECs) [7]. A specific subclass are Mixed Protonic-Electronic Conductors (MPECs), which are capable of conducting both protons and electrons [9]. This dual functionality is crucial for applications in bioelectronics, electrochemical transistors, and advanced energy storage [7] [9]. The conduction mechanism in MPECs can involve a synergistic proton-electron coupling (PEC), where the movement of protons and electrons enhances their mutual transfer, a phenomenon critical in biological processes like photosynthesis [9]. The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for developing and characterizing such advanced conjugated materials.

The conjugated backbone, with its system of alternating single and double bonds and the resulting π-electron delocalization, is the fundamental architectural element that enables conductivity in a wide range of organic polymers. Understanding this principle—from the basic sp² hybridization and band gap formation to advanced concepts like donor-acceptor engineering and mixed ionic-electronic conduction—is essential for designing next-generation materials. As research progresses, the precise control over the conjugated backbone's structure, energy levels, and intermolecular interactions continues to unlock new possibilities in flexible electronics, sustainable energy technologies, and bio-integrated devices. The interplay between foundational theory, sophisticated characterization, and innovative synthesis ensures that conjugated polymers will remain at the forefront of materials science.

Conducting organic polymers represent a unique class of materials that bridge the gap between the electronic properties of traditional metals/semiconductors and the mechanical flexibility, lightweight nature, and processability of conventional polymers [3] [5]. The discovery in the late 1970s that polyacetylene could exhibit metallic conductivity upon doping with iodine marked a paradigm shift in polymer science, ultimately earning the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for Heeger, MacDiarmid, and Shirakawa in 2000 [10] [5]. This breakthrough established the foundation for exploring conjugated polymers with extended π-electron delocalization as electronically active materials, leading to the development of numerous conducting polymers including polyaniline (PANI), polypyrrole (PPy), polythiophene (PTh), and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) [5].

Unlike conventional polymers, conducting polymers possess a conjugated backbone of alternating single and double bonds, which allows for delocalization of π-electrons along the polymer chain [5]. This delocalization, combined with chemical or electrochemical doping, enables these polymers to conduct electricity in a controlled and tunable manner [3] [5]. The electrical conductivity in these materials arises from the formation of charged defects or quasi-particles – specifically polarons, bipolarons, and solitons – upon doping [11] [12]. Understanding the nature, formation, and transport mechanisms of these charge carriers is fundamental to optimizing the performance of organic electronic devices, including light-emitting diodes, photovoltaic cells, sensors, supercapacitors, and transistors [3] [13].

This technical guide examines the core mechanisms of charge carrier formation and transport in conducting organic polymers, focusing on the fundamental physics of polarons, bipolarons, and solitons. The content is framed within the context of ongoing research aimed at enhancing the electrical and optoelectronic properties of these materials for advanced applications.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Charge Transport

Electronic Structure of Conjugated Polymers

The electronic properties of conducting polymers originate from their molecular structure, characterized by a backbone of sp²-hybridized carbon atoms with conjugated π-electron systems [14]. In a solid state, the discrete energy states of atomic orbitals begin to overlap and form energy bands due to the Pauli exclusion principle [13]. The energy band that is fully filled with electrons is called the valence band, while the empty band above it is called the conduction band. The energy difference between these bands is known as the band gap [13].

Organic semiconductors typically have energy gaps ranging from 1 eV to 5 eV and are normally undoped, possessing no free charge carriers at room temperature, which results in low dark current [13]. Charge transport occurs only when carriers are injected from metallic electrodes or generated via optical excitation [13]. The molecular structures in most organic semiconductors, particularly polymers and oligomers, are highly disordered with numerous defects and traps. This disorder causes energy states to become localized, making traditional band theory insufficient for describing charge transport in these materials [13].

Charge Transport Models

The charge transport in organic semiconductors is governed by several mechanisms that differ significantly from those in inorganic crystalline semiconductors. The two primary models are hopping transport and multiple trapping and release (MTR).

Hopping Transport: In highly disordered organic semiconductors, charge transport occurs via thermally activated tunneling between energetically localized states—a process known as hopping [13]. The hopping rate depends on the separation between sites and their energy differences. Two primary models describe this process:

- Miller-Abrahams Model: Describes hopping as a phonon-assisted tunneling process between localized states, with the hopping rate dependent on the spatial separation and energy difference between sites [13].

- Marcus Theory: Applies under higher temperatures and strong electron-phonon couplings, describing electron transfer rates in terms of reorganization energy and driving force [13].

For hopping transport, mobility follows a thermally activated behavior described by: [ \mu = \mu0 \exp\left(-\frac{\Delta E}{kB T}\right) ] where (\mu0) is the mobility prefactor, (\Delta E) is the activation energy, (kB) is Boltzmann's constant, and (T) is temperature [13].

Multiple Trapping and Release (MTR): This model is frequently applied to well-ordered organic semiconductors and involves charge carriers moving freely in a transport band containing delocalized energy states, while periodically becoming trapped in localized energy states at the band edges [13]. If traps are shallow, carriers can be thermally released back into the transport band. The effective mobility in the MTR model is given by: [ \mu{\text{eff}} = \mu0 \alpha \exp\left(-\frac{Et}{kB T}\right) ] where (\alpha) is the ratio of free to total carriers and (E_t) is the trap depth [13].

Table 1: Comparison of Charge Transport Models in Organic Semiconductors

| Transport Model | Applicable Systems | Temperature Dependence | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Band Transport | High-purity single crystals | Decreases with temperature | Delocalized states, minimal disorder |

| Hopping | Disordered polymers and oligomers | Increases with temperature | Localized states, thermally activated |

| Multiple Trapping and Release | Ordered organic semiconductors | Increases with temperature | Shallow traps, transport band with trap states |

Charge Carriers in Doped Conjugated Polymers

Formation of Charged Defects

The unique electrical properties of conducting polymers emerge from the formation of charged defects upon doping. Doping involves the introduction of impurity atoms or molecules that either donate electrons (n-type doping) or accept electrons (p-type doping) from the polymer backbone [15]. This process generates charge carriers in the form of solitons, polarons, and bipolarons, which are responsible for electrical conduction [11] [12].

Solitons are peculiar to conjugated polymers with degenerate ground states, such as trans-polyacetylene. A soliton is a topological defect that separates two phases of bond alternation in the polymer chain [11] [12]. In neutral polymers, solitons are radical defects, but upon doping, they become charged spinless entities that can move along the polymer chain, contributing to electrical conductivity.

Polarons form in polymers with non-degenerate ground states, which include most conducting polymers like polypyrrole, polythiophene, and polyaniline [11] [12]. A polaron is a localized structural distortion of the polymer chain associated with a radical cation (in p-type doping) or radical anion (in n-type doping), carrying both charge and spin 1/2. When a neutral polymer chain is oxidized (p-doped) or reduced (n-doped), the first added charge forms a polaron, which consists of a charged site with accompanying local lattice distortion.

Bipolarons are formed when two like charges share a common lattice distortion, resulting in a spinless defect [11] [12]. In non-degenerate ground-state polymers, the addition of a second charge to an existing polaron leads to the formation of a bipolaron, which is generally more stable than two separate polarons due to the energy gained from sharing a common lattice distortion. Bipolarons consist of two charged states without unpaired spins.

Electronic Structure and Energy States

The formation of these charged defects creates new electronic states within the band gap of the polymer. Polarons introduce two localized states within the band gap – one occupied and one unoccupied – symmetrically positioned about the midgap. Bipolarons create two gap states that are both empty in the case of p-doping (or both filled in the case of n-doping) [11] [12]. The energy levels of these gap states play a crucial role in determining the optical and electronic properties of the material.

The transport properties of these charge carriers are influenced by both intra-chain and inter-chain processes. Along a single polymer chain, charge carriers can move relatively freely, but in bulk materials, conduction requires inter-chain hopping, which is typically the rate-limiting step due to the disordered nature of most polymer systems [13].

Table 2: Characteristics of Charge Carriers in Conducting Polymers

| Charge Carrier | Charge | Spin | Formation Energy | Stability | Mobility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soliton | 0 or ±e | 0 or 1/2 | Lowest in degenerate ground state polymers | High in trans-polyacetylene | High along polymer chain |

| Polaron | ±e | 1/2 | Moderate | Stable in most polymers | Moderate |

| Bipolaron | ±2e | 0 | Lower than two separate polarons | High in non-degenerate polymers | Varies with system |

Doping Strategies and Charge Carrier Generation

Doping Methodologies

Doping is essential for generating charge carriers in conjugated polymers and enhancing their electrical conductivity. Various doping strategies have been developed, each with distinct mechanisms and applications:

Chemical Doping: This traditional approach involves exposing the polymer to oxidizing (p-type) or reducing (n-type) agents. Common p-dopants include iodine, ferric chloride, and various organic acceptors, while n-dopants often involve alkali metals or organic donors [5] [15]. Chemical doping can be performed during or after polymerization and typically results in high carrier concentrations.

Electrochemical Doping: This method utilizes an electrochemical cell where the polymer serves as an electrode. By applying an appropriate potential, ions from the electrolyte are driven into the polymer film, compensating for the injected electronic charges [10]. Electrochemical doping allows precise control over the doping level by adjusting the applied potential and is reversible in many cases.

Contact Doping: This approach forms ohmic contacts in organic semiconductor devices by depositing a doping layer at the interface between the metal electrode and the semiconductor layer [15]. For instance, depositing molybdenum trioxide as a doping layer at the contact interface has been shown to improve overall charge transport in polymer transistors [15].

Photocatalytic Doping: This emerging technique uses photocatalysts to promote redox reactions for doping under light illumination [15]. The doping level can be controlled by adjusting the light dose. Research has demonstrated that photocatalytic p-type doping can increase electrical conductivity from 10⁻⁵ S cm⁻¹ to over 700 S cm⁻¹, while photocatalytic n-type doping can enhance conductivity from less than 10⁻⁵ S cm⁻¹ to nearly 1 S cm⁻¹ [15].

Doping Efficiency and Charge Carrier Concentration

The efficiency of doping processes significantly impacts the resulting charge carrier concentration and overall electrical conductivity. Recent studies have focused on enhancing doping efficiency to improve material performance:

N-type Doping: Research on the design and synthesis of n-type organic semiconductors has shown that enhancing doping efficiency between dopants and polymers effectively increases electrical conductivity [15]. The N2200 series of polymers demonstrated significantly increased conductivity under n-type doping when doping efficiency was optimized.

Cation Exchange Doping: A recent n-type doping method based on cation exchange has shown promise [15]. By selecting appropriate dopants and ionic liquids, both high doping efficiency and high cation exchange efficiency can be achieved simultaneously, leading to high doping levels. This method has achieved electrical conductivity up to 0.01 S cm⁻¹ in organic electronic devices [15].

P-type Doping: Studies have confirmed that improving doping efficiency significantly increases the electrical conductivity of p-type doped polymers. For example, after epitaxy of the F6TCNNQ small molecule on the surface of a DNTT single crystal device, the charge carrier shift rate increased by nearly double [15].

Table 3: Doping Methods and Their Performance Characteristics

| Doping Method | Carrier Type | Conductivity Range | Control Level | Reversibility | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Doping | p or n-type | 10⁻³ - 10⁵ S cm⁻¹ | Moderate | Limited | Bulk materials, fibers |

| Electrochemical Doping | Primarily p-type | 10⁻² - 10³ S cm⁻¹ | High | High | Sensors, actuators, supercapacitors |

| Contact Doping | p or n-type | Varies with system | High | Limited | Transistors, electronic devices |

| Photocatalytic Doping | p or n-type | 10⁻⁵ - 10³ S cm⁻¹ | High | Moderate | Optoelectronics, photovoltaics |

Characterization Techniques for Charge Carriers

Electrical Characterization Methods

Several experimental techniques have been developed to characterize charge carrier mobility and transport properties in organic semiconductors:

Organic Field-Effect Transistor (OFET) Method: This is the prevalent technique for evaluating the mobility of organic semiconductors [13]. OFETs are field-effect transistors where the semiconductor layer is an organic material. The field-effect mobility is extracted from the transfer characteristics using the equation: [ ID = \frac{W Ci \mu}{2L} (VG - VT)^2 ] where (ID) is the drain current, (W) and (L) are the channel width and length, (Ci) is the gate insulator capacitance per unit area, (\mu) is the field-effect mobility, (VG) is the gate voltage, and (VT) is the threshold voltage [13]. OFET measurements provide direct insight into carrier mobility and are essential for device applications.

Time-of-Flight Photoconductivity (TOFP): This method characterizes charge transport in organic semiconducting layers sandwiched between two electrodes [13]. A pulsed laser generates photoexcited charge carriers near one electrode, and their transit across the layer under an applied electric field is measured. The carrier mobility is calculated using: [ \mu = \frac{d^2}{V \cdot tT} ] where (d) is the sample thickness, (V) is the applied voltage, and (tT) is the carrier transit time [13]. TOFP is particularly useful for measuring bulk carrier mobility.

Space-Charge Limited Current (SCLC) Method: This technique analyzes the current-voltage characteristics in a metal-semiconductor-metal structure under high bias conditions where the current is limited by the space charge of injected carriers [13]. The mobility can be extracted from the Mott-Gurney law: [ J = \frac{9}{8} \epsilon0 \epsilonr \mu \frac{V^2}{d^3} ] where (J) is the current density, (\epsilon0) is the vacuum permittivity, (\epsilonr) is the relative dielectric constant, (\mu) is the mobility, (V) is the applied voltage, and (d) is the sample thickness.

Spectroscopic Characterization

Various spectroscopic techniques provide insights into the nature and behavior of charge carriers:

UV-Vis-NIR Spectroscopy: This method detects optical transitions associated with polarons and bipolarons, which typically appear in the band gap region as distinct absorption peaks [11]. The evolution of these sub-gap features with doping level provides information about the relative concentrations of different charge carriers.

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) Spectroscopy: EPR detects unpaired spins and is therefore useful for identifying and quantifying polarons, which carry spin 1/2 [11] [12]. In contrast, bipolarons and charged solitons are diamagnetic and do not produce EPR signals.

Vibrational Spectroscopy: Techniques such as Raman and infrared spectroscopy probe changes in vibrational modes upon doping, which reflect the structural distortions associated with polarons and bipolarons [11]. These methods provide information about the electron-phonon coupling, which is central to the formation of these quasiparticles.

Photoelectron Spectroscopy: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) directly measure the electronic structure, including the density of states in the band gap region arising from polarons and bipolarons [11].

Enhancement Strategies for Charge Carrier Mobility

Molecular Engineering Approaches

Improving charge carrier mobility remains a central challenge in organic semiconductor research. Several molecular-level strategies have been developed to enhance charge transport:

Enhancing π-π Stacking: Strengthening intermolecular π-π packing improves molecular planarity and optimizes molecular arrangement within organic semiconductors [15]. Research has demonstrated that polymers with stronger π-π stacking exhibit higher carrier migration rates. For instance, studies with dicyanobenztriazole-based polymers showed that enhanced π-π packing directly correlates with improved charge transport performance [15].

Side-Chain Engineering: Modifying the side chains of conjugated polymers can significantly impact their packing behavior and electronic properties. Hydrophilic side chains like tri(ethylene glycol) have shown advantages in photocatalytic hydrogen production over hydrophobic alternatives like n-decyloxy and n-dodecyl side chains [14]. Similarly, in poly(3-alkylthiophene) systems, alkyl side-chain length influences photovoltaic properties and charge transport [5].

Donor-Acceptor Architectures: Designing polymers with alternating electron-donor and electron-acceptor units along the backbone enables tuning of electronic properties and can enhance charge separation and transport [14]. This approach has led to significant improvements in organic photovoltaic devices, with power conversion efficiencies approaching 20% in some cases [14].

Processing and Structural Optimization

High-Speed Spin Coating and High-Temperature Annealing: Processing conditions significantly impact molecular orientation and charge transport properties [15]. Studies have shown that high-temperature annealing and high-speed spin-coating enhance lateral orientation of specific molecules in thin films, leading to increased carrier mobility. For example, these processing conditions increased the carrier migration rate of TCDADI-C16 from 0.01 cm² V⁻¹ s⁻¹ to significantly higher values [15].

Nanostructuring and Hybrid Materials: Combining conducting polymers with nanomaterials such as graphene, carbon nanotubes, or metal oxides can enhance electrical conductivity, mechanical strength, and electrochemical performance [10] [5]. Graphene, in particular, has shown promise for boosting mobility due to its two-dimensional honeycomb lattice structure and excellent electronic properties [13].

Interface Engineering: Optimizing interfaces between different materials or layers in devices minimizes charge trapping and facilitates efficient charge injection and extraction [13]. This approach is particularly important in multilayer device structures such as organic light-emitting diodes and photovoltaic cells.

Table 4: Charge Carrier Mobility Enhancement Strategies

| Enhancement Strategy | Mechanism | Typical Mobility Improvement | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| π-π Stacking Enhancement | Improved electron cloud overlap and inter-molecular coupling | 2-10x | Maintaining solubility while enhancing order |

| Side-Chain Engineering | Optimized packing and reduced inter-chain distance | 2-5x | Balancing processability and electronic properties |

| Donor-Acceptor Architecture | Tuned electronic structure and enhanced charge separation | 3-8x | Synthetic complexity and reproducibility |

| Processing Optimization | Controlled morphology and molecular orientation | 2-20x | Scalability and uniformity |

| Hybrid Composites | Additional conduction pathways and reduced hopping barriers | 5-50x | Interface control and material compatibility |

Experimental Protocols for Charge Carrier Studies

Protocol for Doping and Charge Carrier Generation

Chemical Doping of Conjugated Polymers:

Material Preparation: Dissolve the pristine conjugated polymer (e.g., polythiophene, polyaniline) in an appropriate solvent (chloroform, toluene, or NMP) at a concentration of 5-10 mg/mL. Filter the solution through a 0.45 μm PTFE filter to remove aggregates.

Thin Film Fabrication: Deposit polymer films via spin-coating (1000-3000 rpm for 30-60 seconds) onto cleaned substrates (glass, ITO, or SiO₂/Si). Anneal the films at appropriate temperatures (typically 80-150°C) for 10-30 minutes to remove residual solvent and optimize morphology.

Doping Process: Prepare dopant solutions at varying concentrations (e.g., 1-100 mM in acetonitrile or ethanol for solution-based doping). Common p-dopants include FeCl₃, F4TCNQ, and iodine, while n-dopants include benzyl viologen and (RuCp*mes)₂.

Doping Implementation: For solution-based doping, immerse polymer films in dopant solutions for controlled durations (seconds to hours). For vapor-phase doping, expose films to dopant vapors in a controlled environment. For electrochemical doping, use a three-electrode cell with polymer film as working electrode, appropriate electrolyte, and controlled potential application.

Characterization: Measure electrical conductivity via four-point probe method. Record UV-Vis-NIR spectra to monitor polaron/bipolaron formation. Perform EPR measurements to quantify spin concentrations (for polarons).

Protocol for Charge Carrier Mobility Measurement

OFET-Based Mobility Characterization:

Device Fabrication:

- Substrate Preparation: Clean heavily doped silicon wafers with 300 nm thermal oxide layer using standard RCA cleaning procedure.

- Electrode Deposition: Pattern source and drain electrodes (typically gold) through shadow masks or via photolithography. Channel length should range from 20-100 μm.

- Semiconductor Deposition: Deposit the organic semiconductor via spin-coating, drop-casting, or vacuum deposition to form a continuous film (20-100 nm thick).

- Annealing: Thermally anneal the completed devices at optimized temperature (if required) for 10-30 minutes.

Electrical Measurements:

- Perform measurements in inert atmosphere or vacuum to prevent environmental degradation.

- Sweep gate voltage (VG) from positive to negative values (for p-type) or negative to positive (for n-type) while maintaining constant drain voltage (VD).

- Record transfer characteristics (ID vs VG at constant VD) and output characteristics (ID vs VD at constant VG).

Data Analysis:

- Extract field-effect mobility from the saturation regime using: [ \mu = \frac{2L}{W Ci} \left( \frac{\partial \sqrt{ID}}{\partial V_G} \right)^2 ]

- Calculate threshold voltage (VT) from the x-intercept of the √ID vs V_G plot.

- Determine current on/off ratio from the maximum and minimum I_D values.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Charge Carrier Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT) | Model conjugated polymer for fundamental studies | OFETs, solar cells, mobility measurements | Good solubility, well-studied charge transport |

| PEDOT:PSS | Conducting polymer complex for electrodes and transport layers | Hole injection layers, transparent electrodes, sensors | High conductivity, transparency, aqueous processing |

| F4TCNQ | Strong p-type molecular dopant | Electrical conductivity enhancement, polarity control | High electron affinity, solution processable |

| N-DMBI | N-type molecular dopant | Electron transport enhancement, n-type OFETs | Air-stable, effective for various n-type polymers |

| Chloroplatinic Acid | Conductivity enhancer for PEDOT:PSS | High-conductivity transparent electrodes | Increases conductivity via redox reactions |

| Ionic Liquids | Electrolytes for electrochemical doping | Supercapacitors, transistors, sensors | Wide electrochemical window, tunable properties |

| Molybdenum Trioxide | Contact doping layer | Ohmic contact formation in OFETs | Work function alignment, hole injection |

| Graphene Nanoparticles | Mobility-enhancing filler | Hybrid composites, conductive coatings | High intrinsic mobility, large surface area |

Applications and Future Perspectives

The understanding and control of charge carriers in organic polymers have enabled numerous applications across various fields. In energy storage, conducting polymers are used in supercapacitors and batteries, where their rapid redox switching and high charge storage capacity are leveraged [3] [10]. In photovoltaics, organic semiconductors are employed in solar cells, with device architectures optimized for efficient exciton dissociation and charge carrier collection [3] [14]. For sensing applications, the sensitivity of conducting polymers to various chemical and biological analytes is exploited in chemical sensors, biosensors, and electronic noses [10].

Recent advances in photocatalysis have demonstrated the potential of organic semiconductors for solar fuel production and environmental remediation [14]. While challenges such as chemical instability, high exciton binding energy, and low charge carrier mobility remain, strategies including molecular engineering, hybrid material formation, and interface optimization show promise for overcoming these limitations [14].

Future research directions will likely focus on developing more precise doping techniques, understanding charge transport at heterointerfaces in multicomponent systems, and designing materials with tailored energy levels and enhanced stability [10] [14]. The integration of machine learning approaches for predicting charge transport properties and optimizing molecular structures represents an emerging frontier in the field [15]. As fundamental understanding of charge carriers in organic polymers deepens, these materials will continue to enable new technologies in flexible electronics, sustainable energy, and biomedical devices.

Conducting organic polymers (COPs) represent a unique class of materials that combine the electronic properties of semiconductors and metals with the mechanical advantages and processability of plastics. Unlike traditional polymers valued for their insulating properties, COPs possess an extended π-conjugated backbone along which electrons can delocalize, providing a pathway for electrical charge transport [3] [16]. However, this intrinsic conjugation alone is insufficient for substantial electrical conductivity. The transformative process that enables these materials to transition from insulating to metallic states is doping—a redox process that either removes electrons from (oxidation/p-doping) or adds electrons to (reduction/n-doping) the polymer backbone [16]. This controlled introduction of charge carriers, stabilized by counter-ions, fundamentally alters the electronic structure of the material, enabling conductivity enhancements of over ten orders of magnitude [16]. The critical role of doping extends beyond mere conductivity enhancement; it governs the operational mechanisms of COPs across diverse applications, from energy storage and conversion to biomedical devices and environmental technologies. This whitepaper comprehensively examines the redox processes underlying doping, the transition to metallic states, experimental characterization methodologies, and the application-specific tuning of doping protocols, providing researchers with a foundational framework for advancing COP-based technologies.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Doping and Redox Processes

Conceptual Framework of Doping in Conjugated Polymers

The doping process in COPs is fundamentally different from that in traditional inorganic semiconductors. While doping in silicon involves atomic substitution within a crystalline lattice, doping in COPs is a redox-driven process that introduces charge carriers into the π-conjugated system, often accompanied by the incorporation of counter-ions (dopants) to maintain charge neutrality [16]. This process occurs through the following sequential mechanisms:

- Charge Transfer: The polymer chain undergoes oxidation (p-doping) or reduction (n-doping) through interaction with a chemical or electrochemical agent.

- Polaron/Bipolaron Formation: The introduced charge distorts the local structure of the polymer backbone, forming localized states in the band gap known as polarons (single charge) or bipolarons (two charges) [16].

- Counter-Ion Stabilization: Dopant ions migrate into the polymer matrix to stabilize the newly formed charges, preventing recombination and enabling charge delocalization.

- Charge Transport: The charged species propagate along the polymer chain (intrachain transport) and hop between chains (interchain transport), enabling bulk electrical conductivity.

The effectiveness of doping depends critically on the polymer's electronic structure, the steric accessibility of the backbone, the size and mobility of the counter-ions, and the structural order of the polymer matrix [16] [17].

p-Type versus n-Type Doping

Doping in COPs manifests in two primary forms, defined by the nature of the charge transfer:

p-Type Doping (Oxidation): This process involves the removal of electrons from the polymer's valence band, creating positively charged holes as the primary charge carriers. Exemplified by the treatment of polyacetylene with iodine vapor [16], p-doping is generally more stable and prevalent for many COPs, including polypyrrole, polyaniline, and PEDOT. The oxidation potential must be carefully controlled to avoid over-oxidation, which can lead to irreversible structural damage and performance degradation.

n-Type Doping (Reduction): This less common process involves the addition of electrons to the polymer's conduction band, creating negative charges as carriers [18]. n-Type doping is often more challenging to achieve and stabilize, particularly in ambient conditions, due to the susceptibility of the reduced state to reaction with oxygen and water. However, advances in donor-acceptor conjugated polymers, which feature alternating electron-rich and electron-deficient units in their backbone, have improved the prospects for stable n-type materials by lowering the energy levels of the conduction band [18].

Redox Chemistry and Charge Compensation Mechanisms

The redox activity of COPs necessitates a charge compensation mechanism during doping to maintain overall electroneutrality. Real-time studies of doping mechanisms, particularly in organic radical polymers, have revealed two dominant modes of ion transport and doping during the redox process: doping by cation expulsion and doping by anion uptake [17]. The dominance of one mode over the other is controlled by factors including anion type, electrolyte concentration, and timescale. For instance, in polyaniline-based systems, the switching between these mechanisms can be quantitatively monitored using techniques like electrochemical quartz crystal microbalance (EQCM), which tracks mass changes in the polymer film during redox cycling [17]. Understanding these ion flux dynamics is critical for designing materials with fast switching speeds and high charge capacity, particularly for electrochemical energy storage and conversion applications.

Experimental Characterization of Doping Processes and Metallic Transitions

Quantitative Metrics for Doping Assessment

Researchers employ multiple characterization techniques to quantify doping levels and their effects on electronic properties. The doping level (y) is typically defined as the number of dopant molecules per repeating monomer unit in the polymer chain. For instance, in polyacetylene, a doping level of y = 0.1 represents one dopant per ten monomer units, which can increase conductivity from 10⁻⁵ S/cm to over 10⁵ S/cm [16]. The table below summarizes key performance metrics for representative doped conducting polymers.

Table 1: Electrical Properties of Representative Conducting Organic Polymers Before and After Doping

| Polymer | Undoped Conductivity (S/cm) | Doped Conductivity (S/cm) | Primary Dopants | Doping Type | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyacetylene [16] | 10⁻⁹ (cis), 10⁻⁵ (trans) | >10⁵ | I₂, Br₂, AsF₅ | p-type | Fundamental studies |

| Poly(p-phenylene vinylene) (PPV) [16] | 10⁻¹³ | 10² to 10⁴ | H₂SO₄ | p-type | Light-emitting diodes (LEDs) |

| Polyaniline (Emeraldine base) [16] | ~10⁻¹⁰ | 1-10 | HCl, H₂SO₄ | p-type (protonic) | Sensors, corrosion protection |

| PEDOT:PSS [4] | - | ~1 (can be enhanced) | PSS (built-in), ionic liquids | p-type | Organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs) |

Advanced Protocol: Real-Time Analysis of Doping Mechanisms

To provide researchers with a practical methodology for probing doping mechanisms, the following detailed protocol, adapted from studies on organic radical polymers, allows for quantitative tracking of ion transport [17].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Doping Mechanism Analysis

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Critical Parameters & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Electroactive Polymer Film | The working electrode material whose doping is under study. | Preferrably a well-defined thin film (100-500 nm) on a conductive substrate. |

| Lithium Salts (LiTFSI, LiClO₄) | Provide mobile cations (Li⁺) in the electrolyte. | Concentration (e.g., 0.1-1.0 M) significantly influences ion transport mode. |

| Tetraalkylammonium Salts (TBAPF₆, TBAClO₄) | Provide bulkier cations; used to study anion-dominated transport. | Size of the alkylammonium cation affects mobility and partitioning. |

| Aprotic Solvents (Acetonitrile, Propylene Carbonate) | Electrolyte solvent, must be electrochemically inert in the operating window. | Must be thoroughly dried and degassed to prevent side reactions. |

| Electrochemical Quartz Crystal Microbalance (EQCM) | Measures mass changes in the polymer film in situ during doping/dedoping. | Calibration of mass-frequency relationship is critical for quantitative data. |

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) Setup | Applies controlled redox potential to drive the doping process. | Scan rate determines the timescale of the experiment. |

Experimental Workflow:

- Electrode Preparation: Fabricate a uniform film of the electroactive polymer (e.g., poly(TEMPO-methacrylate)) on the gold-coated quartz crystal of an EQCM. Determine the exact mass of the dry film.

- Electrochemical Cell Assembly: Assemble a standard three-electrode cell with the polymer-coated EQCM crystal as the working electrode, a Pt counter electrode, and a stable reference electrode (e.g., Ag/Ag⁺). Fill the cell with the electrolyte solution (e.g., 0.5 M LiTFSI in acetonitrile).

- In Situ Coupled Measurement:

- Apply a constant-current charge/discharge or a linear potential sweep (CV) to the working electrode to initiate the doping process.

- Simultaneously record the change in resonance frequency of the EQCM crystal, which is directly related to the mass change (Δm) of the polymer film via the Sauerbrey equation.

- Data Interpretation:

- Mass Increase during Oxidation: Indicates dominant anion uptake from the electrolyte into the polymer to compensate for the generated positive charge.

- Mass Decrease during Oxidation: Indicates dominant cation expulsion from the polymer into the electrolyte to compensate for the loss of negative charge (e.g., in a pre-reduced n-type system).

- The slope of the Δm vs. charge (Q) plot provides quantitative insight into the molar mass of the dominant moving ion.

This protocol enables researchers to move beyond indirect inferences and directly identify the operative doping mechanism under specific electrochemical conditions, which is vital for optimizing material performance.

Structural Control and Advanced Doping Strategies

Spatial Control of Doping for Device Engineering

Advanced doping strategies now extend beyond uniform bulk treatment. A groundbreaking approach involves spatial control of dedoping to create complex device functions from a single material. For instance, introducing asymmetric contact areas (e.g., source and drain contacts differing by up to 3 orders of magnitude in area) in a PEDOT:PSS channel enables contact-mediated control of where dedoping occurs [4]. This spatial modulation allows the creation of single-material complementary transistors, which are essential for building compact, power-efficient amplifier circuits for biomedical implants [4]. This geometric control of doping represents a paradigm shift, enabling functional electronic circuits without the need for complex multi-material patterning or inadequate stability.

The Role of Polymer Structure and Dopant Interactions

The efficiency of doping and the ultimate conductivity achieved are profoundly influenced by the molecular structure of the polymer and its interaction with dopants. Donor-acceptor (D-A) conjugated polymers are particularly promising in this regard. In these systems, the alternating electron-rich (donor) and electron-poor (acceptor) units in the backbone create a narrow band gap, facilitating both p-type and n-type doping [18]. The "push-pull" effect inherent in D-A polymers leads to high intrinsic charge carrier mobility even with minimal doping, a crucial property for maintaining a high Seebeck coefficient in organic thermoelectric applications [18]. Furthermore, the choice of dopant—from small ions like Cl⁻ to large polymeric anions like PSS⁻ (polystyrene sulfonate)—affects not only charge carrier density but also the structural order, mechanical flexibility, and interfacial properties of the resulting material [4] [10].

Application-Specific Doping Protocols and Performance

The strategic application of doping protocols is pivotal to unlocking the functionality of COPs across various technological domains. The doping requirements and mechanisms differ significantly depending on the target application, as outlined below.

Table 3: Doping Protocols and Performance in Key Application Areas

| Application Area | Doping Objective | Typical Doping Method & Materials | Key Performance Metrics & Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Storage (Batteries/Capacitors) [17] [19] | Achieve high charge capacity and fast redox kinetics for rapid charging. | Electrochemical n- and p-doping of organic radical polymers (e.g., poly(TEMPO)) or conjugated polymers in electrolyte. | - Capacity retention >95% over thousands of cycles.- Charging times of seconds to minutes. |

| Organic Electronics (OECTs) [4] | Modulate channel conductivity volumetrically via ion injection from an electrolyte. | In situ electrochemical doping of PEDOT:PSS or other mixed conductors by gate electrode in physiological buffers. | - Transconductance >10 mS.- Stable operation for over 1 month in vivo. |

| CO₂ Reduction Catalysis [20] | Enhance charge separation and provide active sites for CO₂ adsorption/activation. | Creating composites of COPs (e.g., polypyrrole) with metals/MOFs; doping optimizes charge carrier mobility. | - Increased CO₂ adsorption and photocurrent generation.- High selectivity for value-added fuels (e.g., CH₄, CO). |

| Wastewater Treatment [3] [16] | Enable adsorption and photocatalytic degradation of pollutants. | Chemical or electrochemical doping to enhance surface activity and charge separation in COP composites. | - Removal of heavy metal ions (Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺) via adsorption.- Degradation of organic dyes under visible light. |

Visualization of Doping Processes and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the core concepts and experimental workflows discussed in this whitepaper.

Diagram 1: Doping Mechanisms in a Conjugated Polymer

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Doping Mechanism Analysis

Doping, through controlled redox processes, is the critical enabling technology that unlocks the metallic states and functional properties of conducting organic polymers. The transition from insulator to conductor is not merely a change in electrical property but a fundamental alteration of the material's electronic structure, driven by the intricate interplay of electron transfer and ion flux. As research progresses, the focus is shifting from achieving high conductivity to precisely controlling doping profiles spatially and temporally, as exemplified by single-material complementary transistors [4], and understanding doping dynamics at the molecular level through advanced in situ techniques [17]. The future of the field lies in designing novel polymer architectures like donor-acceptor systems [18] for more stable and efficient n-type and p-type doping, developing smarter doping strategies that leverage geometric and electrochemical control, and integrating these advances into scalable fabrication processes. A deep and nuanced understanding of doping mechanisms will continue to be the cornerstone for innovating next-generation organic electronic, energy, and biomedical devices.

The transition of conjugated organic systems from semiconducting to metal-like conductivity represents a frontier in materials science. This whitepaper examines the fundamental principles of band theory as applied to organic semiconductors, detailing the mechanisms that enable enhanced charge transport. We explore how chemical doping, molecular engineering, and advanced fabrication techniques can significantly reduce the band gap and improve charge carrier mobility, achieving conductivity improvements of over 10 orders of magnitude in certain conjugated polymer systems. The experimental methodologies and material systems discussed herein provide a framework for ongoing research into organic conductive materials with applications spanning from bioelectronics to energy storage and flexible devices.

Organic semiconductors represent a unique class of materials that exhibit electronic conductivity between that of insulators and metals, typically ranging from 10⁻² to 10⁻¹⁴ ohm per centimeter [21]. Unlike inorganic semiconductors that possess well-defined crystalline structures, organic semiconductors are characterized by conjugated molecular systems with alternating single and double bonds. This conjugation creates a system of π-electrons that can delocalize across molecular frameworks, forming energy bands that facilitate charge transport.

The electronic properties of organic semiconductors are governed by their band structure, which consists of a valence band (the highest occupied molecular orbital, HOMO) and a conduction band (the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital, LUMO), separated by an energy gap [22] [21]. The lower this band gap, the higher the conductivity of the semiconductor material. In organic systems, band gaps are generally higher than those in inorganic semiconductors, resulting in typically lower electronic conductivity. However, through strategic molecular design and processing techniques, researchers have developed methods to reduce these band gaps and enhance charge transport properties, enabling the realization of metal-like conductivity in organic systems.

Fundamental Conductivity Mechanisms

Band Theory and Beyond

In conventional band theory, electrons are thermally excited to the conduction band, generating "holes" in the valence band that collectively facilitate charge transport [21]. However, in organic semiconductors, several complementary mechanisms govern charge transport:

Polaron Transfer: Polarons are quasiparticles consisting of an electron and its associated local distortion of the molecular structure. In polaron theory, energy bands form only after electrons have interacted with local molecular vibrations, differing from conventional band theory where electron-vibration interactions are treated as perturbations [21].

Electron Hopping: This mechanism involves electrons moving between discrete molecular sites in a thermally-activated process [21]. The rate of electron hopping depends strongly on molecular spacing and orientation, with closer packing typically enhancing conductivity.

Exciton Motion: When organic crystals are exposed to light, excitons (loosely bound electron-hole pairs) form and move through the crystal structure until they dissociate at interfaces or crystal dislocations, generating photoconduction [21].

Metallic Conductivity at Interfaces