Strategies for Reducing Agglomeration in Polymer Nanocomposites: Enhancing Properties for Biomedical and Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies to mitigate nanoparticle agglomeration in polymer nanocomposites, a critical challenge for researchers and drug development professionals.

Strategies for Reducing Agglomeration in Polymer Nanocomposites: Enhancing Properties for Biomedical and Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies to mitigate nanoparticle agglomeration in polymer nanocomposites, a critical challenge for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental causes and detrimental effects of agglomeration on mechanical, electrical, and biological properties. The content details advanced dispersion techniques, surface modification methods, and process optimization strategies to achieve uniform nanoparticle distribution. Furthermore, it covers characterization methods and predictive models for validating dispersion quality and performance. The insights are tailored to inform the design of next-generation nanocomposites for targeted drug delivery, implantable devices, and other advanced biomedical applications.

Understanding Agglomeration: The Fundamental Challenge in Polymer Nanocomposites

Defining Aggregation and Agglomeration in Nanocomposite Systems

Fundamental Definitions and Their Impact

What is the fundamental difference between aggregation and agglomeration?

In polymer nanocomposites, both aggregation and agglomeration describe the assembly of nanoparticles, but they differ significantly in the strength and nature of the bonds holding the particles together.

- Aggregation refers to the formation of strong and dense particle collectives, typically held together by direct mutual attraction via covalent or metallic bonds or through solid-state sintering. These structures are generally difficult to break apart [1].

- Agglomeration describes the assembly of loosely combined particles held together by weaker forces, such as van der Waals forces or electrostatic attractions. These assemblies can often be disrupted by mechanical forces applied during processing [1] [2].

This distinction is critical because the formation of aggregates or agglomerates diminishes the interfacial area between the polymer matrix and nanoparticles, leading to defects, stress concentrations, and ultimately, a deterioration of the nanocomposite's mechanical properties [1] [2].

How do aggregation and agglomeration negatively affect nanocomposite properties?

The presence of aggregates and agglomerates fundamentally undermines the key advantage of using nanoscale fillers: their high surface-to-volume ratio. The primary negative consequences are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Detrimental Effects of Aggregation/Agglomeration on Nanocomposite Properties

| Affected Property | Impact and Consequence |

|---|---|

| Mechanical Performance | Significant reduction in Young's modulus, tensile strength, and toughness. Agglomerates act as stress concentration points, initiating failure [1] [2] [3]. |

| Reinforcement Efficiency | Drastic decrease in the stiffening effect of nanoparticles. The high modulus of nanoparticles becomes ineffective if they are not properly dispersed [2]. |

| Interfacial Area | Reduction of the available surface area for polymer-filler interaction, which is crucial for stress transfer and property enhancement [3]. |

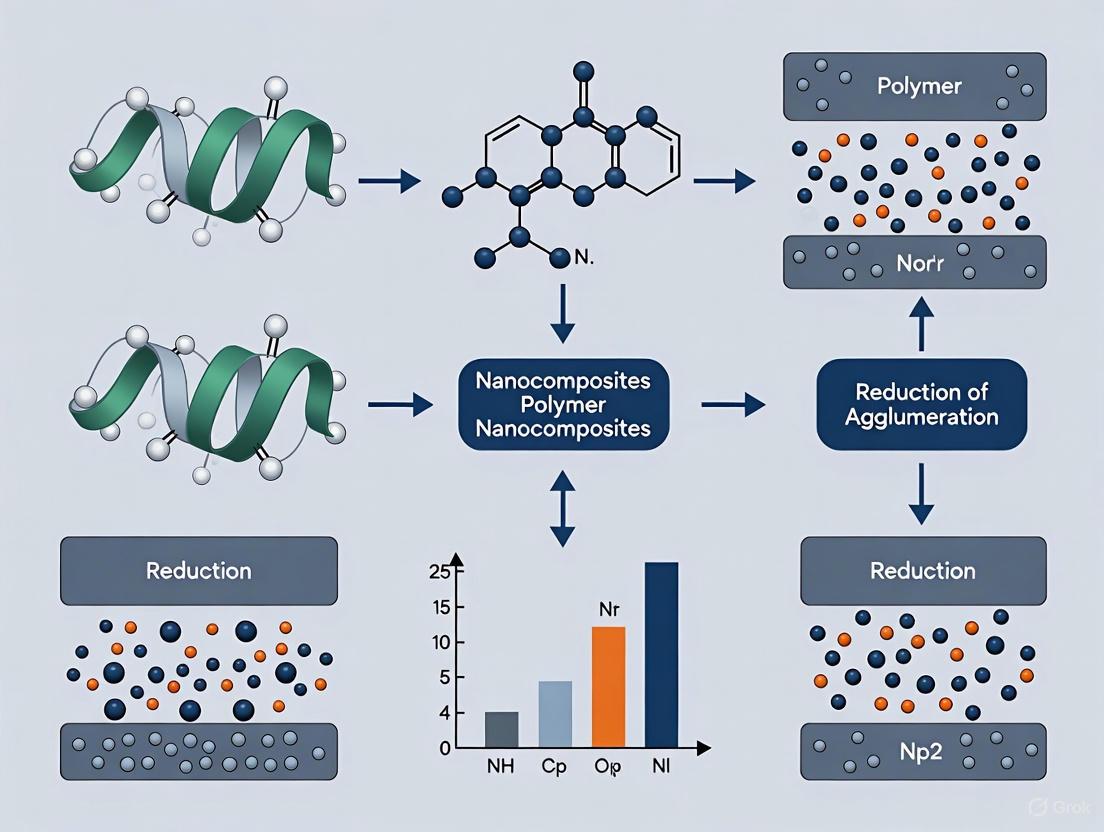

Diagram 1: The Vicious Cycle of Aggregation and Its Consequences. This flowchart illustrates how the inherent properties of nanoparticles lead to attraction, resulting in aggregation/agglomeration and ultimately poor nanocomposite performance, which must be counteracted by mitigation strategies.

Troubleshooting and FAQs: Identifying and Quantifying the Problem

How can I experimentally detect and quantify aggregation in my samples?

A combination of characterization techniques is required to accurately assess the state of nanoparticle dispersion.

Table 2: Techniques for Characterizing Aggregation/Agglomeration

| Technique | What it Measures | Common Pitfalls to Avoid |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Hydrodynamic size distribution in a solution. A size larger than the primary particle indicates agglomeration [4]. | Always characterize materials yourself; do not rely solely on manufacturer specifications. Measurements are highly sensitive to the dispersing medium (e.g., size can double in plasma vs. PBS) [4]. |

| Electron Microscopy (SEM/TEM) | Direct visualization of particle size, morphology, and dispersion state at the nanoscale [4]. | Sample preparation can introduce artifacts or contamination. Use appropriate protocols and tools to minimize this [5]. |

| Analysis of Mechanical Properties | Using micromechanical models to determine the "A" parameter (aggregation level) or the effective volume fraction of agglomerated nanoparticles (φ_agg) from shear yield or tensile data [1]. | Requires accurate input data for the model. Assumes insignificant primary aggregation from nanoparticle synthesis. |

Why does my nanocomposite show poor mechanical properties even with a high nanofiller loading?

This is a classic symptom of extensive nanoparticle aggregation. When nanoparticles agglomerate, they behave as large, microscopic defects rather than as nanoscale reinforcements. This has several effects:

- Reduced Interfacial Area: The polymer matrix cannot interact with the surface of nanoparticles trapped inside an agglomerate, drastically reducing stress transfer efficiency [3].

- Stress Concentrations: The irregular shape and poor adhesion of agglomerates create points of high stress that initiate cracking and premature failure [1].

- Inefficient Load Bearing: The model of Dorigato et al., which suggests aggregates can reinforce, is an exception; most studies conclusively show that agglomeration severely damages the stiffening effect of nanoparticles [2].

The following experimental workflow outlines a methodology to systematically diagnose this issue.

Diagram 2: Diagnostic Workflow for Poor Mechanical Properties. This flowchart provides a step-by-step guide to determine if aggregation is the root cause of underperforming nanocomposites.

Experimental Protocols for Analysis

Protocol: Two-Step Micromechanical Modeling of Young's Modulus to Quantify Agglomeration

This methodology uses the measured Young's modulus to determine the extent of nanoparticle agglomeration [2].

1. Principle: The nanocomposite is modeled as a system containing two phases: (A) spherical regions of aggregated/agglomerated nanoparticles, and (B) an effective matrix phase containing well-dispersed nanoparticles.

2. Key Agglomeration Parameters:

z: The volume fraction of the nanocomposite occupied by the aggregation/agglomeration phase (V_agg / V).y: The volume fraction of the total nanofiller that is trapped inside the aggregates/agglomerates (V_f_agg / V_f).

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Calculate the modulus of the aggregation/agglomeration phase (

E_agg) and the effective matrix phase (E_mat) using Paul's model. This model requires the Young's moduli of the polymer matrix and the nanofiller, and the parametersyandz. - Step 2: Calculate the overall nanocomposite modulus (

E) using the Maxwell model, which now treats the aggregation/agglomeration phase as spherical inclusions dispersed in the effective matrix phase. The volume fraction of these inclusions isz.

4. Output: By fitting the model predictions to your experimental modulus data, you can back-calculate the values of z and y that best describe your sample, providing a quantitative measure of the agglomeration state [2].

Protocol: Avoiding Endotoxin Contamination in Biocompatible Formulations

For nanocomposites intended for biomedical applications (e.g., drug delivery), endotoxin contamination is a critical concern that can mask true biocompatibility and cause immunostimulatory reactions [4].

1. Problem: Over one-third of samples submitted to the Nanotechnology Characterization Laboratory (NCL) have contamination requiring purification or re-manufacture.

2. Prevention Steps:

- Work Sterilely: Perform synthesis and purification in biological safety cabinets, not chemical fume hoods. Use depyrogenated glassware and sterile filters.

- Verify Reagents: Do not assume commercial reagents or purified water are endotoxin-free. Screen starting materials and equipment wash samples.

- Choose Filters Wisely: Avoid cellulose-based filters, as they contain beta-glucans that interfere with endotoxin assays.

3. Detection (LAL Assay):

- Always perform Inhibition and Enhancement Controls (IEC) to check for nanoparticle interference.

- If interference occurs (e.g., from colored or turbid formulations), use an alternative LAL method or a recombinant Factor C assay [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Mitigating Aggregation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Reducing Aggregation/Agglomeration |

|---|---|

| Coupling Agents / Compatibilizers | Improve the interfacial adhesion between the hydrophobic polymer matrix and hydrophilic nanofillers, promoting wetting and dispersion [1]. |

| Surface Capping Agents | Sterically hinder nanoparticles from approaching each other too closely, preventing the van der Waals forces from causing agglomeration [1]. |

| High-Shear Mixers (Twin-Screw Extruders) | Apply intense mechanical stress to break apart loosely bound agglomerates during melt compounding [1] [6]. |

| Pyrogen-Free Water & Solvents | Essential for preparing biocompatible nanocomposites to avoid endotoxin contamination that confounds biological testing [4]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do nanoparticles tend to agglomerate in polymer matrices? The primary cause is van der Waals forces, which are attractive intermolecular forces that act between nanoparticles at close range [7]. These forces cause nanoparticles to attract one another, leading to clumping or agglomeration. This is particularly problematic because nanoparticles have a high surface-area-to-volume ratio, which magnifies the effect of these surface forces [8]. Agglomeration is often a sign of an unfavorable interfacial interaction between the nanoparticle surface and the polymer matrix.

Q2: How does surface energy relate to nanoparticle dispersion? Surface energy is a measure of the excess energy at a material's surface compared to its bulk [9]. Nanoparticles with high surface energy are thermodynamically driven to lower their energy, often by adhering to other particles, which promotes agglomeration. For good dispersion, the surface energy of the nanoparticle should be compatible with the surface energy of the polymer matrix. A significant mismatch can lead to poor wetting of the nanoparticles by the polymer, causing the nanoparticles to be expelled from the matrix and form agglomerates [9].

Q3: What are the practical consequences of agglomeration in my nanocomposite? Agglomeration is a critical defect that severely degrades the intended properties of polymer nanocomposites [10]. It creates weak points and inhomogeneities within the material. Key impacts include:

- Reduced Mechanical Enhancement: Agglomerates act as stress concentrators, diminishing mechanical properties like tensile strength and modulus [11] [10]. For instance, larger agglomerates (e.g., 60 nm radius) can reduce the modulus improvement from 205% to just 40% compared to smaller, well-dispersed agglomerates [11].

- Impaired Electrical Conductivity: In conductive composites, agglomeration can break conductive pathways, increasing electrical resistivity [10].

- Altered Porosity: Agglomeration can create unwanted voids and porosity, which negatively affects the mechanical integrity and other functional properties of the nanocomposite [10].

Q4: Can agglomeration ever be beneficial? In most applications, agglomeration is detrimental. However, controlled or reduced agglomeration can be beneficial. For example, the presence of smaller, controlled agglomerates (e.g., ~10 nm radius) can positively influence the effective volume fraction and interphase contribution, leading to a significant enhancement of the nanocomposite's modulus [11]. Furthermore, induced porosity from agglomeration can be desirable in specific applications like biomimetic scaffolds for tissue engineering, where porosity is needed for cell proliferation [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing the Root Cause of Agglomeration

| Observation | Possible Root Cause | Supporting Data / Quantitative Relationship |

|---|---|---|

| Severe agglomeration at low filler content | High nanoparticle surface energy leading to strong van der Waals attraction [9]. | A high surface energy solid (e.g., metals, ceramics) will cause poor wetting by a low surface tension polymer, leading to high contact angles and particle cohesion [9]. |

| Agglomeration increases with nanoparticle loading | Exceeding the percolation threshold; system thermodynamics favor particle-particle interactions over particle-polymer interactions [10]. | Studies on MWCNT/epoxy show agglomeration effects become significant at 2% volume fraction, degrading mechanical properties [10]. |

| Properties decline despite high filler loading | Formation of large agglomerates creating defects and reducing the effective reinforced volume [11] [10]. | Modelling shows an increase in agglomerate radius from 10 nm to 60 nm diminishes the modulus improvement from 205% to just 40% [11]. |

| Voids and porosity around agglomerates | Poor interfacial adhesion and incompatibility between the hydrophobic/hydrophilic character of the filler and matrix [10]. | A non-homogeneous mixture creates voids, lowering stiffness and strength; e.g., porosity in graphite-nanoflake/PDMS composites increases with nanoflake concentration [10]. |

Guide 2: Quantitative Effects of Agglomeration and Interphase Properties

This table summarizes key quantitative relationships from modelling and experimental studies to help set your experimental targets.

| Factor | Impact on Nanocomposite Modulus | Key Quantitative Data |

|---|---|---|

| Agglomerate Size (Radius) | Smaller agglomerates significantly enhance modulus; larger agglomerates diminish improvement. | Ragg = 10 nm: Enhancement up to 205% [11]. Ragg = 60 nm: Enhancement reduced to ~40% [11]. |

| Interphase Thickness (t) | A thicker, stiffer interphase region dramatically improves load transfer and modulus. | t = 20 nm, Ei = 40 GPa: Enhancement of 145% [11]. t < 5 nm: Enhancement of only ~50% [11]. |

| Filler Concentration | Low concentrations improve properties; high concentrations promote agglomeration and property decline. | Agglomeration in MWCNT/epoxy begins at ~2% vol. fraction, reducing mechanical strength [10]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Surface Modification of Nanoparticles to Reduce Van der Waals Forces

Objective: To lower the surface energy of nanoparticles and improve compatibility with the polymer matrix, thereby reducing agglomeration.

Materials:

- Nanoparticles (e.g., nanodiamond, graphene, metal oxides)

- Silane coupling agent

- Anhydrous solvent (e.g., toluene)

- Beaker, magnetic stirrer, ultrasonic bath

- Centrifuge

Methodology:

- Dispersion: Disperse the nanoparticles in the anhydrous solvent using ultrasonication for 30 minutes.

- Reaction: Transfer the dispersion to a beaker equipped with a stirrer. Add a calculated amount of silane coupling agent (e.g., 1-10 wt% relative to nanoparticles).

- Heating and Stirring: Heat the mixture to 60-80°C and stir continuously for 4-12 hours under an inert atmosphere to prevent hydrolysis.

- Washing and Centrifugation: Allow the mixture to cool. Separate the modified nanoparticles by centrifugation (e.g., 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes) and wash with fresh solvent 2-3 times to remove unreacted silane.

- Drying: Dry the purified, surface-modified nanoparticles in a vacuum oven at 60°C overnight.

Visual Workflow:

Protocol 2: Advanced Physical Dispersion via Twin-Screw Extrusion

Objective: To achieve a uniform distribution of nanoparticles within a polymer matrix using high shear and thermal energy.

Materials:

- Polymer resin (pellets or powder)

- Surface-modified nanoparticles

- Twin-screw extruder

- Pelletizer

Methodology:

- Pre-mixing: Pre-mix the polymer resin and nanoparticles to create a rough feedstock. This can be done using a tumbler mixer.

- Extrusion: Feed the pre-mixed material into the hopper of a co-rotating twin-screw extruder.

- Parameter Optimization: Set the temperature profile along the extruder barrels according to the polymer's melting point. Configure the screw speed (e.g., 100-500 rpm) to apply high shear forces that break apart agglomerates.

- Compounding: The material is melted, mixed, and conveyed through the intermeshing screws. The design of the screws (kneading blocks) promotes dispersive and distributive mixing.

- Pelletizing: The homogeneously mixed melt is extruded through a die, cooled in a water bath, and pelletized for further processing (e.g., injection molding).

Visual Workflow:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Mitigating Agglomeration |

|---|---|

| Silane Coupling Agents | Form a covalent bridge between inorganic nanoparticles and the organic polymer matrix, reducing the energy mismatch and improving adhesion [8]. |

| Surfactants | Adsorb onto nanoparticle surfaces, creating a steric or electrostatic barrier that counteracts van der Waals attraction and prevents particles from coming close enough to agglomerate. |

| Halloysite Nanotubes (HNTs) | Act as a natural reinforcement agent; their tubular structure can help reduce chain mobility and improve the physical behavior of the biopolymer matrix, as demonstrated in chitosan/pectin films [12]. |

| Citric Acid (CA) | Serves as a natural crosslinking agent in biopolymer systems like chitosan and pectin. Crosslinking can strengthen the matrix and improve its resistance to degradation, which helps maintain integrity and potentially immobilizes fillers [12]. |

| Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) | A multifunctional nanofiller that can act as a compatibilizer in polymer blends (e.g., PLA/PDoF), promoting dispersion of the secondary phase and enhancing interfacial interaction, which reduces phase separation and agglomeration [12]. |

The Critical Link Between Agglomeration and Diminished Mechanical Properties

Quantitative Evidence: How Agglomeration Degrades Key Properties

Agglomeration negatively impacts mechanical performance by reducing the effective interfacial area between nanoparticles and the polymer matrix, creating stress concentration points and defects. The tables below summarize the quantitative evidence from research.

Table 1: Impact of Agglomeration Size on Nanocomposite Stiffness (Nanodiamond/Polymer System)

| Agglomerate Radius (Ragg) | Improvement in Young's Modulus | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| 10 nm | Up to 205 % enhancement | Nanodiamond agglomeration model, considering interphase effects [11] |

| 60 nm | Only 40 % improvement | Nanodiamond agglomeration model, considering interphase effects [11] |

Table 2: Mechanical Property Degradation in CNT/Epoxy Nanocomposites

| CNT Weight Fraction | Observed Effect on Young's Modulus | Primary Identified Cause |

|---|---|---|

| 2% | Maximum modulus value achieved | Sufficient dispersion, percolation threshold reached [13] |

| 4% and 5% | Adverse effect, reduction in properties | Significant formation of CNT agglomerates and porosity [13] |

Table 3: The Interplay Between Interphase Properties and Agglomeration

| Interphase Characteristic | Impact on Composite Modulus | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Thick interphase (t = 20 nm) & High modulus (Ei = 40 GPa) | 145 % enhancement | Dense and tough interphase compensates for some agglomeration effects [11] |

| Thin interphase (t < 5 nm) | Only 50 % improvement | Limited interphase cannot counter the negative impact of agglomeration [11] |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Agglomeration

Two-Step Micromechanical Method for Quantifying Agglomeration

This methodology uses micromechanical models to determine the level of nanoparticle aggregation/agglomeration in polymer nanocomposites by matching theoretical predictions with experimental modulus values [2].

Step 1: Define Agglomeration Parameters Two key parameters are defined to quantify agglomeration [2]:

- ( z ): The volume fraction of the aggregation/agglomeration phase in the nanocomposite.

- ( y ): The fraction of total nanoparticles located within the agglomerated regions.

Step 2: Calculate Phase Moduli Using Paul's Model The modulus of the agglomerated phase (( E{agg} )) and the effective matrix phase (( E{mat} )) containing well-dispersed nanoparticles are calculated using Paul's model, substituting the respective nanoparticle volume fractions [2].

Step 3: Calculate Composite Modulus Using Maxwell's Model The modulus of the entire nanocomposite is calculated by modeling the agglomerated phases as spherical inclusions dispersed within the effective matrix phase, using Maxwell's model [2].

Step 4: Determine Agglomeration Parameters (z and y) The parameters ( z ) and ( y ) are iteratively adjusted until the predicted composite modulus from the two-step method matches the experimentally measured modulus. Higher values of ( z ) and ( y ) indicate more significant agglomeration [2].

Protocol for Analyzing Agglomeration via Tensile Strength

The Pukanszky model is a widely used empirical approach to quantify the effect of filler-matrix interface and agglomeration on tensile strength.

Procedure:

- Experimentally measure the tensile strength (( \sigma )) of the neat polymer matrix and the nanocomposite at a specific nanoparticle volume fraction (( \phi_f )) [14].

- Apply the Pukanszky model: ( \sigma = \sigmam \frac{1-\phif}{1+2.5\phif} \exp(B\phif) ) where ( B ) is an interfacial adhesion parameter [14].

- Calculate the ( B ) parameter from the experimental data. A lower ( B ) value indicates weaker interfacial adhesion, often resulting from nanoparticle agglomeration, which reduces the effective interfacial area and load transfer efficiency [14].

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guide

FAQ 1: Why does agglomeration lead to a decrease in the mechanical properties of my nanocomposites?

Agglomeration creates regions with high nanoparticle concentration and poor polymer infiltration, leading to [2] [10] [14]:

- Reduced Interfacial Area: The primary mechanism of reinforcement in nanocomposites is the large interfacial area for stress transfer. Agglomerates act as large, ineffective particles with low specific surface area.

- Defect Formation: Agglomerates become points of stress concentration, initiating failure like microcracks and voids under load.

- Diminished Interphase Contribution: The interphase, a polymer region with altered properties around well-dispersed nanoparticles, is a key reinforcing element. Agglomeration drastically reduces the volume of this effective interphase.

FAQ 2: My nanocomposite's modulus is much lower than theoretical predictions. Is agglomeration the cause?

Yes, this is a classic symptom. Theoretical models often assume perfect, homogeneous dispersion of nanoparticles. Agglomeration invalidates this assumption, leading to overestimation of properties. Calculations based on well-dispersed nanoparticles consistently overestimate the composite modulus, while models that account for agglomeration show strong agreement with experimental data [11] [2]. If your experimental results are far below theoretical values, agglomeration is the most probable cause.

FAQ 3: I am using high-modulus nanoparticles, but my composite's stiffness is not improving significantly. What is wrong?

A high modulus of the nanoparticles alone is not sufficient for composite enhancement. The critical factor is the efficient transfer of stress from the polymer matrix to the nanoparticles. Agglomeration severely limits this stress transfer. Without good dispersion and a strong interface, the stiffening potential of the nanoparticles cannot be realized [2] [14]. Surface chemistry must be adjusted to prevent agglomeration and ensure good dispersion.

Troubleshooting Guide:

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Stiffness/Strength | High degree of nanoparticle agglomeration; Weak polymer-particle interface [2] [13]. | - Implement surface modification of nanoparticles (e.g., silanization) [15]. - Optimize dispersion protocol (e.g., ultrasonication, high-shear mixing) [8]. - Use compatibilizers to improve interfacial adhesion. |

| Properties Degrade at High Filler Loading | Increased nanoparticle agglomeration at higher concentrations leading to porosity and defects [10] [13]. | - Identify the optimal filler content below the critical agglomeration threshold. - Employ more advanced dispersion techniques (e.g., twin-screw extrusion, solvent-assisted dispersion) [8]. |

| Inconsistent Results Between Batches | Uncontrolled agglomeration due to inconsistent dispersion protocols or material variations [16]. | - Standardize and strictly document the dispersion method (e.g., energy input, time, solvent). - Characterize nanoparticle dispersion state in every batch (e.g., via microscopy). |

Research Reagent Solutions for Mitigating Agglomeration

Table 4: Key Materials and Methods for Improved Dispersion

| Reagent/Method | Function/Purpose | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Modifiers (e.g., (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane) | Reduces nanoparticle surface energy, weakens van der Waals forces causing agglomeration, and improves compatibility with the polymer matrix [15]. | Surface modification of silica nanoparticles in HDPE nanocomposites, leading to better dispersion and enhanced mechanical properties [15]. |

| Physical Dispersion: Ultrasonication | Applies high-frequency sound waves to create cavitation bubbles, generating intense local shear forces that break apart nanoparticle clusters [8]. | Effective for deagglomerating carbon nanotubes (CNTs) in epoxy resins prior to mixing [8] [13]. |

| Physical Dispersion: Twin-Screw Extrusion | Provides high shear and thermal energy in a continuous process, effectively dispersing nanoparticles in molten polymers during compounding [8]. | Standard industrial method for dispersing nanoclays or graphene in thermoplastics like polypropylene [8]. |

| Hybrid Filler Systems | Using a combination of different nanofillers can create synergistic effects that improve the overall dispersion state of each filler [16]. | Using a hybrid of multilayered graphene and carbon nanotubes to reduce the agglomeration of both fillers in the polymer [16]. |

Visualizing the Agglomeration Problem and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core concepts of how agglomeration impacts the microstructure and properties of polymer nanocomposites.

The diagram above illustrates the fundamental mechanism behind property degradation: agglomeration drastically reduces the interfacial area critical for stress transfer. The workflow below outlines a systematic experimental approach to diagnose and address this issue.

Impact on Electrical Conductivity and Percolation Threshold

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary factors that control the electrical conductivity of polymer nanocomposites? Several variables govern conductivity, including filler amount, filler conductivity, filler dimensions, nanoparticle dispersion, tunneling effect, and interfacial condition [17]. The formation of a continuous conductive network (percolation) is essential, and this network is highly sensitive to the quality of dispersion and the presence of an interphase layer around the nanoparticles [17] [18].

2. Why is agglomeration a critical problem in conductive nanocomposites? Agglomeration occurs due to strong van der Waals forces between nanomaterials like graphene and carbon nanotubes, causing them to clump together [19] [20]. These clumps prevent uniform dispersion, which increases the percolation threshold and hinders the formation of a continuous conductive network. This results in lower electrical conductivity, inconsistent properties, and reduced mechanical strength [19] [20].

3. How does the interphase region affect the percolation threshold? The interphase is a region surrounding nanoparticles with distinct properties, formed due to the high surface area of the nanofiller and its interaction with the polymer matrix [17] [18]. A well-formed interphase can significantly lower the percolation threshold because the interphase layers themselves can form a connected network even before the nanofillers make direct physical contact [17] [21] [18]. Furthermore, the interphase facilitates the tunneling effect, a key charge transfer mechanism [18].

4. What is electron tunneling and why is it important? Electron tunneling is a quantum mechanical phenomenon where electrons transfer between two nearby conductive nanoparticles separated by a thin insulating polymer layer [21] [22]. This effect is the primary mechanism for charge conduction in many nanocomposites, especially when fillers are not in direct physical contact. The tunneling distance is critical; typically, distances less than 10 nm are needed for effective tunneling, with shorter distances leading to significantly higher conductivity [21] [22].

5. What strategies can effectively reduce agglomeration? Several methods can mitigate agglomeration:

- Physical Methods: Using organic solvents, ultrasonication, and selecting suitable dispersion and production methods [19].

- Chemical Methods: Functionalizing the fillers to improve their compatibility with the polymer matrix [19].

- Hybrid Fillers: Using a combination of different fillers can create synergistic effects that improve the overall dispersion state [19].

- 3D Architectures: Creating three-dimensional foam structures of nanomaterials via processes like freeze-drying can prevent agglomeration and establish efficient conductive pathways [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Percolation Threshold

A high percolation threshold means you need to add a large amount of expensive nanofiller to make the composite conductive, which is inefficient and can worsen mechanical properties.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Filler Agglomeration | Use SEM to visualize filler dispersion. Look for clusters instead of isolated particles [19]. | Improve dispersion via prolonged sonication or solution mixing. Consider using surfactants or functionalized fillers [19]. |

| Low Filler Aspect Ratio | Check filler specifications from supplier. Model the percolation threshold using known dimensions [17] [24]. | Source fillers with a higher aspect ratio (longer length or larger diameter). For existing fillers, ensure processing doesn't break them [17]. |

| Poor or Non-existent Interphase | This is difficult to observe directly. Indirectly assess by modeling percolation and conductivity with interphase parameters [17] [21]. | Enhance polymer-filler interaction through chemical functionalization of the filler surface to promote a thicker, more effective interphase [17] [18]. |

| Large Tunneling Distance | Model the system's conductivity considering tunneling effects. Distances >1.8-3 nm drastically reduce tunneling [21] [22]. | Optimize processing to achieve a more uniform filler distribution, reducing the average gap between nanoparticles [21]. |

Problem: Low Electrical Conductivity

The composite's conductivity is lower than expected, even after exceeding the perceived percolation threshold.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Filler Network | Check if filler concentration is just above the percolation threshold. Conductivity increases gradually after percolation [22]. | Increase filler loading to boost the fraction of networked filler. Alternatively, use hybrid fillers to create more robust networks [19] [23]. |

| High Filler Waviness | Analyze filler morphology using TEM imaging. Waviness reduces effective aspect ratio [18]. | If using CNTs, select straighter variants or adjust processing conditions (e.g., curing under alignment fields) to reduce waviness [17] [22]. |

| Large Tunneling Resistance | The polymer matrix itself creates a tunneling resistance. Thicker polymer layers between fillers increase resistance [21] [22]. | Focus on achieving a homogeneous dispersion with minimal inter-particle distances (preferably <1.8 nm) [21] [22]. |

| Imperfect Interphase | Model the system with a "conduction transfer parameter" (Y). A low Y indicates poor conduction transfer from filler to polymer [17]. | Improve interfacial adhesion and properties through filler functionalization to enhance the conduction transfer efficiency [17]. |

Quantitative Data for Material Selection

The following table summarizes key parameters from recent research that significantly impact percolation and conductivity. Use this as a guide for selecting materials and setting targets.

| Parameter | Impact on Percolation Threshold | Impact on Electrical Conductivity | Target Range / Optimal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filler Aspect Ratio (Length/Diameter) | Higher aspect ratio drastically lowers percolation [17] [18] [24]. | Higher aspect ratio increases conductivity by forming networks more easily [17] [18]. | As high as possible (e.g., >1000). Note: rods with aspect ratio <1000 deviate from ideal scaling [24]. |

| Interphase Thickness | A thicker interphase lowers the percolation threshold [17] [21] [18]. | A thicker interphase increases conductivity by promoting tunneling and networked pathways [17] [21]. | Models show significant benefits up to ~40 nm [21]. |

| Tunneling Distance | A smaller tunneling distance lowers the percolation threshold [17]. | A smaller tunneling distance exponentially increases conductivity. The effect is dramatic below 1.8 nm [21] [22]. | Ideally ≤ 1.8 nm. Tunneling is negligible beyond ~10 nm [21] [22]. |

| Filler Waviness (u = straight length/actual length) | Higher waviness (u >> 1) increases the percolation threshold [18]. | Higher waviness decreases conductivity by reducing the effective aspect ratio [18]. | As close to 1 (perfectly straight) as possible [18]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Solution Mixing and Ultrasonication

This is a common method for preparing polymer nanocomposites with a focus on achieving good dispersion.

1. Objective: To disperse conductive nanofillers (e.g., graphene, CNTs) uniformly within a polymer matrix using solvent-assisted ultrasonication to minimize agglomeration and achieve a low percolation threshold.

2. Materials and Equipment:

- Polymer matrix (e.g., Epoxy resin).

- Conductive nanofiller (e.g., Graphene nanosheets, Multi-walled Carbon Nanotubes).

- Suitable solvent (e.g., Acetone, Dimethylformamide) that can dissolve the polymer.

- Ultrasonic probe sonicator.

- Magnetic stirrer and hotplate.

- Vacuum oven for solvent removal.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Polymer Dissolution. Dissolve the polymer matrix in the solvent using magnetic stirring at moderate temperature (e.g., 40-50°C) until a clear solution is obtained.

- Step 2: Filler Dispersion. Gradually add the nanofiller to the polymer solution under continuous stirring to achieve preliminary wetting.

- Step 3: Ultrasonication. Subject the mixture to probe ultrasonication for a set duration (e.g., 30-60 minutes). Use an ice bath to prevent solvent evaporation and overheating, which can damage the filler or polymer.

Critical Step: Optimize sonication time and amplitude. Under-sonication leaves agglomerates, while over-sonication can break fillers, reducing their aspect ratio and compromising conductivity [17] [19].

- Step 4: Solvent Removal. Pour the dispersed mixture into a petri dish and place it in a vacuum oven to slowly evaporate the solvent. Controlled evaporation helps prevent re-agglomeration.

- Step 5: Post-Processing. The resulting solid composite can be further processed by hot-pressing or compression molding to form final specimens for testing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Graphene Nanosheets | A 2D conductive filler with extremely high aspect ratio and conductivity, excellent for lowering percolation threshold and enhancing conductivity [17] [23]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | 1D tubular carbon structures (SWNTs or MWNTs) with high aspect ratio and conductivity, used to create conductive networks in polymers [19] [22]. |

| MXene Nanosheets | A class of 2D transition metal carbides/nitrides with high electrical conductivity and hydrophilic surfaces, making them promising for conductive composites [21]. |

| Hexagonal Boron Nitride (hBN) | A 2D electrical insulator with high thermal conductivity. Often used in hybrid filler systems or for applications requiring thermal conduction but electrical insulation [23]. |

| Functionalized Fillers | Fillers (e.g., COOH- or NH₂-modified CNT/Graphene) with surface chemical groups that improve compatibility with the polymer matrix, reduce agglomeration, and strengthen the interphase [19] [18]. |

| Surfactants / Dispersing Agents | Chemicals that adsorb onto filler surfaces, reducing their surface energy and van der Waals forces to prevent agglomeration during processing [19]. |

Relationship Between Key Factors and Conductivity

The diagram below illustrates the logical relationships between material properties, processing conditions, and the resulting macroscopic electrical properties of the nanocomposite.

Consequences for Interfacial/Interphase Properties and Composite Performance

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

| Problem Phenomenon | Possible Root Cause | Recommended Solution | Supporting Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor mechanical reinforcement despite low nanofiller loading. | Nanoparticle agglomeration reducing effective interfacial area and stress transfer [25] [1]. | Implement surface functionalization of nanofillers or use compatibilizers to improve dispersion and polymer-filler bonding [26] [27]. | [1] [27] |

| Inconsistent property data between experimental batches. | Uneven dispersion of nanoparticles within the polymer matrix, leading to variable microstructure [28]. | Standardize the mixing protocol (e.g., sonication power/duration, screw speed in melt compounding) and use surfactants [26] [1]. | [26] [28] |

| Reduced glass transition temperature (Tg) or altered relaxation dynamics. | Poor interfacial adhesion and agglomeration restrict polymer chain mobility [25] [29]. | Enhance interfacial interactions via chemical bonding between nanofiller and matrix to increase the effective interphase volume [25] [26]. | [25] [29] |

| Electrical/thermal conductivity below theoretical predictions. | Formation of agglomerates preventing the formation of a continuous conductive network [26]. | Optimize filler loading and dispersion process to achieve a uniform percolation network; use hybrid filler systems [26]. | [26] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is the dispersion of nanoparticles so challenging, and what are the main types of aggregation?

The primary challenge stems from strong intermolecular van der Waals forces attracting nanoparticles to each other [25] [1]. This leads to two main types of particle assemblies:

- Aggregation: Dense, strongly bonded particle collectives that are difficult to break apart [1] [2].

- Agglomeration: Loosely combined particles that might be separated by mechanical forces [1] [2]. Both forms significantly reduce the specific surface area of the nanofiller, which is critical for creating a large interfacial region with the polymer matrix [27].

Q2: How does agglomeration directly weaken the mechanical properties of my nanocomposite?

Agglomeration negatively impacts properties through several mechanisms [1] [27]:

- Reduced Stress Transfer: The large, clustered particles have a lower surface-to-volume ratio, which minimizes the load-bearing interface and impedes efficient stress transfer from the polymer matrix to the reinforcing nanofiller.

- Stress Concentrations: Agglomerates act as microscopic defects or voids within the composite, creating points of high stress concentration that can initiate cracks and lead to premature failure.

- Lower Effective Filler Content: A portion of the nanofiller is trapped inside agglomerates and does not contribute to reinforcement, effectively lowering the volume fraction of nanoparticles that interact with the polymer chains.

Q3: What are the most effective strategies to minimize agglomeration in my experiments?

Several strategies have proven effective in promoting dispersion and reducing agglomeration [26] [1]:

- Surface Functionalization: Chemically modifying the surface of nanoparticles to improve their chemical compatibility with the polymer matrix and create repulsive forces between particles.

- Use of Compatibilizers/Coupling Agents: Adding these agents can act as a molecular bridge, enhancing adhesion between the filler and the matrix.

- Optimized Processing Parameters: In melt compounding, parameters like screw speed, shear rate, and temperature can be tuned to apply sufficient stress to break apart agglomerates [1].

- Sonication: High-power ultrasonication is a common and effective method for dispersing nanoparticles in solvents or low-viscosity polymers, though it is best for small batches [26].

Q4: Can I quantitatively assess the level of agglomeration in my samples?

Yes, agglomeration can be studied indirectly through mechanical property modeling. A two-step micromechanical methodology has been suggested to determine aggregation parameters (z and y), where z is the volume fraction of the aggregation phase in the composite, and y is the fraction of total nanofiller located within that phase [2]. By fitting theoretical models (e.g., Paul and Maxwell models) to experimental Young's modulus data, researchers can back-calculate the extent of agglomeration [2].

Quantitative Data on Agglomeration Impact

Table 1: Experimentally observed agglomeration parameters (z and y) in various polymer nanocomposite systems, as determined by a two-step micromechanical modeling method [2].

| Nanocomposite System | Filler Content (wt%) | Aggregation Phase Fraction (z) |

Filler in Aggregates (y) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PVC / CaCO₃ | 7.5% | 0.20 | 0.95 |

| PCL / Nanoclay | 10% | 0.30 | 0.75 |

| PLA / Nanoclay | 5% | 0.10 | 0.99 |

| PET / MWCNT | 1.5% | 0.35 | 0.70 |

| Polyimide / MWCNT | 1.5% | 0.15 | 0.90 |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Characterizing Agglomeration via Mechanical Modeling

This protocol uses a two-step micromechanical analysis to quantify nanoparticle agglomeration [2].

- Input Material Properties: Determine the Young's modulus of the neat polymer matrix ((Em)) and the nanofiller ((Ef)).

- Measure Composite Modulus: Experimentally measure the Young's modulus of the nanocomposite at various filler loadings.

- Apply the Two-Step Model:

- Step 1: Use the Paul model [2] to calculate the modulus of the hypothesized aggregated regions ((E{agg})) and the well-dispersed effective matrix regions ((E{mat})). This calculation requires assumed values for the agglomeration parameters

zandy. - Step 2: Use the Maxwell model [2] to calculate the overall composite modulus by treating the aggregated phase as spherical inclusions dispersed in the effective matrix.

- Step 1: Use the Paul model [2] to calculate the modulus of the hypothesized aggregated regions ((E{agg})) and the well-dispersed effective matrix regions ((E{mat})). This calculation requires assumed values for the agglomeration parameters

- Iterate to Fit Data: Adjust the parameters

zandyuntil the model's prediction matches the experimental modulus data. The best-fit values indicate the level of agglomeration.

Protocol 2: Assessing Interfacial/Interphase Strength via Yield Strength

This protocol evaluates the quality of the interface by analyzing the composite's shear yield strength ((\tau)) [1] [27].

- Measure Shear Properties: Obtain the shear yield strength of the neat polymer matrix ((\tau_m)) and the nanocomposite.

- Calculate Interparticle Distance: The distance between nanoparticles ((\lambda)) can be calculated from the filler volume fraction and the size of the nanoparticles or their agglomerates [27].

- Apply Model: Use the relationship (\tau = \taum + G bB / \lambda) [1] [27], where (G) is the shear modulus and (b_B) is the Burgers vector.

- Interpret Results: A lower experimental yield strength than predicted by the model for well-dispersed particles indicates poor stress transfer, often caused by agglomeration and a weak interphase [27].

Relationship Between Agglomeration and Properties

The following diagram illustrates the cascading negative effects of nanoparticle agglomeration on the interphase and final composite performance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential materials and techniques for investigating and mitigating agglomeration.

| Item / Technique | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Coupling Agents (e.g., silanes) | Improve interfacial adhesion by creating chemical bonds between nanofiller and polymer matrix [26]. | Select an agent with functional groups compatible with both the filler surface and the polymer. |

| Surfactants & Dispersants | Reduce surface tension and create steric/electrostatic repulsion between nanoparticles to prevent agglomeration in suspensions [26]. | Must be compatible with the polymer system to avoid plasticization or other side effects. |

| High-Shear Mixers & Ultrasonicators | Apply physical force to break apart agglomerates during composite processing [26]. | Optimize parameters (speed, time, power) to balance dispersion quality with potential damage to nanoparticles. |

| Micromechanical Models (Paul, Maxwell) | Quantify agglomeration levels and predict composite properties based on constituent properties and microstructure [2]. | Requires accurate input data for matrix and filler properties. |

| Characterization Techniques (TEM, XRD, DMA, TGA) | Analyze dispersion quality, crystal structure, thermal transitions, and filler content [30] [29]. | A combinatorial approach is often necessary for a complete picture of the morphology. |

Advanced Dispersion Techniques and Surface Functionalization Methods

Agglomeration is a fundamental challenge in polymer nanocomposites research, as it prevents the uniform dispersion of nanoparticles within the polymer matrix, ultimately limiting the enhancement of mechanical, electrical, and thermal properties. Physical dispersion methods are crucial for overcoming the strong interparticle forces, such as van der Waals attractions, that cause nanoparticles to form stubborn agglomerates. This technical support guide addresses common experimental issues and provides detailed protocols for three key physical dispersion techniques: ultrasonication, bead milling, and twin-screw extrusion, framed within the context of a thesis focused on reducing agglomeration.

Troubleshooting FAQs

1. My carbon nanotube (CNT) composites are not achieving electrical percolation even at loadings above the theoretical threshold. What is wrong?

- Problem: The dispersion process is likely insufficiently breaking up primary CNT agglomerates, or it is severely shortening the CNTs, reducing their aspect ratio and hindering network formation.

- Solutions:

- For Melt Mixing (Twin-Screw Extrusion): Monitor the Specific Mechanical Energy (SME) input. A higher SME (up to a certain point, e.g., ~0.4 kWh/kg) improves dispersion but can also shorten CNTs. If the state of dispersion is good but conductivity is poor, the CNTs may be too short. Try using a screw profile with more distributive mixing elements rather than dispersive ones to reduce shear-induced breaking [31].

- For Ultrasonication: Ensure you are using sufficient but not excessive power and time. Excessive ultrasonication can introduce defects and shorten CNTs, reducing their effectiveness for creating a conductive network [32] [33]. Characterize the CNT length after processing if possible.

- Consider a Hybrid Approach: Use a combination of chemical (surface modification) and physical (optimized ultrasonication or extrusion) methods to improve dispersion without excessive damage [34] [35].

2. How can I prevent the re-agglomeration of nanoparticles after I have successfully dispersed them?

- Problem: After dispersion, nanoparticles tend to re-agglomerate over time due to their high surface energy.

- Solutions:

- Surface Modification: This is the most effective long-term strategy. Modify the nanoparticle surface with surfactants, silanes, or polymer grafts to create steric hindrance or electrostatic repulsion between particles. For instance, coating magnetite nanoparticles with silica via a sol-gel process significantly improved their stability in suspension by changing the surface charge and providing a physical barrier [36].

- Optimize Matrix Compatibility: For melt processing, use compatibilizers (e.g., maleic anhydride grafted polymers) to improve the wetting and adhesion between the nanoparticle and the polymer matrix, "locking" them in place [34] [33].

- Process Control: In extrusion, ensure the melt is cooled rapidly after mixing to "freeze" the well-dispersed state before re-agglomeration can occur.

3. I am getting inconsistent results between different batches when using probe ultrasonication. How can I improve reproducibility?

- Problem: Inconsistent results often stem from unoptimized and unmonitored sonication parameters.

- Solutions:

- Systematic Optimization: Develop a protocol where you characterize the dispersion quality (e.g., by DLS for hydrodynamic diameter, TEM for morphology) at different time points during the sonication process to identify the optimal duration [32].

- Control Temperature: Use a water bath to control the temperature rise during sonication, as excessive heat can alter the dispersion medium and damage sensitive nanoparticles [32].

- Prevent Contamination: Be aware that probe sonication can cause tip erosion, contaminating the sample. For critical applications, consider using an indirect sonicator (e.g., with a vial tweeter) to eliminate this variable [32].

- Document Parameters Rigorously: Record all parameters including power (W), amplitude (%), pulse duration (on/off time), and sample volume for every experiment.

4. What is the most effective way to disperse two-dimensional nanofillers like graphene nanoplates (GNP) in a polymer melt?

- Problem: GNPs have strong interlayer bonding and a high aspect ratio, making them difficult to exfoliate and disperse without breaking them.

- Solutions:

- Combined Physical-Chemical Pretreatment: Prior to melt mixing, use techniques like ball milling or solid-state shear pulverization to break down large GNP agglomerates [34] [33].

- Use of Ultrasound-Assisted Extrusion: Studies have shown that applying ultrasonic waves directly in the melt during twin-screw extrusion can significantly improve the exfoliation and dispersion of layered nanofillers, though its effectiveness for GNP may be less than for CNTs or carbon black [34].

- Optimize Screw Profile: Use a screw profile that generates high shear stress to peel apart the layers but is balanced with distributive mixing to spread them throughout the matrix without excessive reduction in platelet size.

The following tables summarize critical operational parameters and their effects on dispersion quality for each method.

Table 1: Ultrasonication Parameters and Guidelines

| Parameter | Key Considerations | Typical Range/Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Sonication Type | Probe (direct) vs. Bath (indirect) | Probe: higher intensity, risk of contamination. Bath: gentler, more reproducible for toxicological studies [32]. |

| Power/Amplitude | Energy input into the system | Higher power accelerates deagglomeration but can damage particles (e.g., shorten CNTs) and increase temperature [32]. |

| Duration | Time of ultrasound application | Requires optimization; too short = poor dispersion, too long = particle damage and reduced stability [32]. |

| Pulsing | Intermittent cycles (e.g., 5s on/2s off) | Helps control temperature rise and allows particles to migrate back into sonication zones [32]. |

| Sample Volume | Volume of liquid to be processed | Critical for reproducibility. Must be kept constant for a given protocol [32]. |

Table 2: Twin-Screw Extrusion (TSE) Parameters and Their Impact

| Parameter | Key Considerations | Impact on Dispersion & Composite Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Screw Speed | Rotation speed (RPM) | Higher speed increases shear and SME, improving dispersion but can shorten nanofillers and degrade polymer [31]. |

| Screw Profile | Sequence of conveying, kneading, and mixing elements | Dispersive mixing (kneading blocks) breaks agglomerates. Distributive mixing (toothed elements) distributes them evenly [31]. |

| Specific Mechanical Energy (SME) | Total mechanical energy input per mass unit (kWh/kg) | Higher SME generally improves dispersion up to a plateau. Beyond this, filler shortening may dominate, harming properties like electrical conductivity [31]. |

| Feed Rate/Throughput | Mass flow rate of material | Affects residence time and fill factor in the extruder, influencing dispersion quality [31]. |

| Feeding Position | Hopper (main) vs. Side Feeder | Feeding fillers downstream via a side feeder can reduce filler breaking and polymer degradation, sometimes yielding better electrical and mechanical properties [31]. |

Table 3: Bead Milling Parameters and Guidelines

| Parameter | Key Considerations | Impact on Dispersion |

|---|---|---|

| Bead Size & Material | Diameter and density of milling media | Smaller, denser beads (e.g., zirconia) are more effective for breaking nano-agglomerates but generate more heat. |

| Bead Loading | Volume fraction of beads in chamber | Optimal loading (typically 50-80% of chamber volume) maximizes collision frequency for efficient milling. |

| Rotor Speed | Speed of the agitator | Higher speed increases collision energy, improving dispersion kinetics but also increasing heat and potential for contamination. |

| Processing Time | Duration of milling | Must be optimized; insufficient time leads to poor dispersion, while over-milling can damage particles and the polymer. |

| Suspension Viscosity | Rheology of the polymer/nanoparticle mix | Affects the transmission of shear forces. Optimal viscosity is required for efficient energy transfer. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimizing Ultrasonication for Aqueous Nanomaterial Dispersions

This protocol, adapted from [32], provides a systematic, step-by-step approach to achieve stable, well-dispersed suspensions, which can be a precursor to solution-based composite preparation.

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Preliminary Setup:

- Materials: Nanomaterial (e.g., CeO₂, ZnO, CNTs), deionized water, surfactant/dispersant (if required), ultrasonic bath, probe sonicator (or vial tweeter), ice bath.

- Prepare a stock suspension with a fixed nanomaterial concentration (e.g., 0.1-1 mg/mL) in a defined volume of dispersant. If needed, add a stabilizer like sodium citrate.

Systematic Parameter Sweep:

- Divide the stock suspension into multiple identical vials.

- Subject each vial to a different set of sonication conditions, systematically varying:

- Sonication Time: (e.g., 1, 5, 10, 20 minutes).

- Amplitude/Power: (e.g., 20%, 50%, 80% of maximum).

- Pulsing Mode: (e.g., continuous vs. 5 seconds on / 2 seconds off).

- Maintain a constant sample volume and control temperature using an ice bath to ensure comparisons are valid.

Real-Time Characterization:

- After each sonication condition, immediately analyze a small aliquot of the dispersion using:

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): To measure the hydrodynamic diameter (Z-average) and Polydispersity Index (PdI). The goal is to find the point where the size is minimized and the PdI is lowest.

- Electrophoretic Light Scattering (ELS): To measure the Zeta Potential (ZP). A value above |25| mV typically indicates good electrostatic stability.

- After each sonication condition, immediately analyze a small aliquot of the dispersion using:

Identify Optimal Conditions:

- Plot the hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential against sonication time and power.

- The optimal point is where you achieve the smallest hydrodynamic diameter with an acceptable PdI and a zeta potential indicating good stability, before any signs of re-agglomeration or particle degradation appear.

Final Quality Assessment:

- Prepare a final dispersion using the identified optimal parameters.

- Use Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) to visually confirm the state of dispersion, exfoliation, and absence of damage.

- Use UV-Vis spectroscopy to monitor the absorption over 24-48 hours to confirm dispersion stability. A stable dispersion will show minimal change in its characteristic absorption peak.

Protocol 2: Ultrasound-Assisted Twin-Screw Extrusion for Polymer/CNT Composites

This protocol details the use of high-power ultrasound integrated into a melt extruder to enhance the dispersion of carbon nanotubes in a thermoplastic matrix like Polyetherimide (PEI) or Polypropylene (PP) [37] [34].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Material Preparation:

- Materials: Polymer resin (e.g., PEI, PP), multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs).

- Dry the polymer resin in a vacuum oven according to manufacturer specifications (e.g., 110°C for 24 hours for PEI).

- Pre-mix the dried polymer powder with the desired loading of MWCNTs (e.g., 1-5 wt%) using a tumbler mixer or ball milling to ensure a roughly homogeneous dry blend.

Baseline Compounding:

- Set up the twin-screw extruder with a standard screw configuration (containing both distributive and dispersive mixing elements).

- Process the pre-mixed material without activating the ultrasound system.

- Record process data: torque, melt pressure, and melt temperature. Collect the extruded strand.

Ultrasound-Assisted Compounding:

- Using the same screw configuration and processing temperature, re-process the pre-mixed material or a masterbatch.

- Activate the ultrasonic transducer attached to the extruder barrel. Start with a low amplitude (e.g., 3-5 µm) and gradually increase it in subsequent runs (e.g., up to 10 µm).

- Monitor and record the ultrasonic power consumption and the pressure at the die. A drop in pressure upon ultrasound application indicates a reduction in melt viscosity.

Sample Collection and Analysis:

- Collect the extruded strands from both the baseline and ultrasound-assisted runs.

- Rheology: Perform oscillatory rheology on the composite pellets. An increase in storage modulus and complex viscosity in the low-frequency region after ultrasonic treatment indicates better dispersion and formation of a network structure [37].

- Electrical Conductivity: Measure the volume resistivity. A significant drop (several orders of magnitude) in the percolation region confirms improved CNT networking due to better dispersion [34] [37].

- Morphology: Analyze cryo-fractured surfaces using High-Resolution Scanning Electron Microscopy (HRSEM) to visually confirm the reduction in CNT agglomerate size and improved distribution [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Nanocomposite Dispersion Experiments

| Material / Reagent | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Citrate | Electrostatic stabilizer for aqueous nanoparticle dispersions (e.g., metal oxides) [36]. | Provides a negative surface charge, increasing zeta potential and preventing agglomeration via electrostatic repulsion. |

| Organosilanes (e.g., TEOS) | Coupling agent for surface modification of oxide nanoparticles (SiO₂, TiO₂) [33]. | Forms a silica-like shell via sol-gel processes, providing steric hindrance and improving compatibility with polymer matrices. |

| Quaternary Ammonium Salts | Modifier for layered silicates (clays) [33]. | Facilitates cation exchange, expanding the clay galleries and making the surface more organophilic for better polymer intercalation. |

| Polymer Grafts (e.g., PP-g-MA) | Compatibilizer for non-polar polymers like polypropylene [34]. | The maleic anhydride group interacts with filler surfaces, while the PP backbone entangles with the matrix, improving adhesion and dispersion. |

| Sodium Salt of 6-Aminohexanoic Acid | Modifier for carbon nanotubes in polar matrices like polyamide [34]. | Assists in debundling CNTs via 'cation-π' interactions, improving dispersion and significantly lowering electrical percolation thresholds. |

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How can I prevent nanoparticle aggregation in my polymer nanocomposite?

Issue: Nanoparticles tend to form large aggregates and agglomerates when incorporated into a polymer matrix, creating defects and reducing mechanical properties.

Solutions:

- Surface Functionalization: Covalently attach organic functional groups (e.g., R-NH₂, R-COOH) to nanoparticle surfaces using homo- or hetero-bifunctional cross-linkers. This introduces electrostatic or steric repulsion between particles [38].

- Polymer Coating: Wrap nanoparticles with charged polymers like polyethyleneimine (PEI) or poly(acrylic acid) (PAA). These coatings provide electrosteric stabilization and prevent close contact via van der Waals forces [39].

- Optimize Processing: During melt compounding, use optimal screw speed and feeding rate in extruders to apply sufficient shear stress and disrupt particle aggregates [1].

Experimental Protocol: Silanization for Silica NPs

- Disperse silica nanoparticles in anhydrous toluene via sonication.

- Add (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) at a 1:100 mass ratio (NPs:silane).

- React under reflux at 80°C for 6 hours with continuous stirring.

- Purify by repeated centrifugation and washing with ethanol.

- Characterize success by FTIR for amine groups and DLS for hydrodynamic size and ζ-potential [38] [39].

FAQ 2: Why is my surface functionalization not improving cellular uptake?

Issue: After surface modification, the nanoparticles still show poor uptake by target cells, reducing therapeutic efficacy.

Solutions:

- Check Ligand Orientation and Density: Ensure targeting ligands are correctly oriented for receptor binding. Use controlled bioconjugation (e.g., click chemistry) for site-specific attachment. Aim for optimal ligand density [40] [39].

- Reduce Protein Corona: Pre-coat with inert molecules like human serum albumin to minimize non-specific protein adsorption that masks targeting ligands [38].

- Verify Surface Charge: Use ζ-potential measurements. A slightly positive charge often improves cellular internalization, but avoid excessive charge to prevent non-specific binding [38] [41].

Experimental Protocol: Ligand Coupling via Click Chemistry

- Functionalize NPs with azide groups using azide-silane or azide-PEG crosslinkers.

- Prepare ligand (e.g., peptide) with a terminal alkyne group.

- React azide-NPs and alkyne-ligand in a 1:5 molar ratio using a Cu(I) catalyst.

- Incubate at room temperature for 24 hours with gentle shaking.

- Purify using gel filtration or dialysis.

- Validate conjugation yield with UV-Vis spectroscopy or HPLC and confirm bioactivity via cell-binding assay [40].

FAQ 3: How do I characterize the success and stability of surface modification?

Issue: It is challenging to confirm successful surface functionalization and its colloidal stability in physiological buffers.

Solutions and Characterization Techniques: Integrate multiple techniques for a comprehensive analysis [38] [39].

Table 1: Key Techniques for Characterizing Surface-Modified Nanoparticles

| Technique | Information Provided | Experimental Protocol Summary |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Hydrodynamic size, size distribution, aggregation state [38]. | Dilute NP sample in relevant buffer; measure intensity-based size distribution at 25°C; perform stability study over 48 hours. |

| ζ-Potential Analysis | Surface charge, confirmation of successful functionalization [38] [39]. | Measure electrophoretic mobility in a folded capillary cell; report value as mean ± SD from 3 runs. |

| Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy | Chemical bonds, functional groups on surface [38]. | Prepare dried NP film on KBr plate; scan from 4000 to 500 cm⁻¹; identify characteristic peaks (e.g., 1640 cm⁻¹ for amide). |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Core size, shape, and direct visualization of aggregation [38]. | Deposit NP suspension on carbon-coated grid; stain if necessary; image at appropriate magnification. |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Elemental and chemical state composition of the surface [42]. | Analyze dried NPs under ultra-high vacuum; survey scan for elements; high-resolution scan for specific bonds (e.g., C-N). |

FAQ 4: How does nanoparticle agglomeration affect mechanical properties?

Issue: The expected enhancement of Young's modulus in the polymer nanocomposite is not achieved.

Root Cause: Agglomeration creates stress concentration points, reduces the effective interfacial area between the polymer and nanoparticles, and diminishes the stiffening effect [1] [2].

Quantitative Analysis:

A two-step micromechanical model can quantify the effect. The model uses parameters z (volume fraction of agglomeration phase) and y (volume fraction of nanoparticles within the agglomeration phase) [2].

Table 2: Effect of Agglomeration on Young's Modulus (Sample Data)

| Nanocomposite System | Nanofiller Content (wt%) | Agglomeration Parameters (z, y) | Observed Modulus Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| PVC / CaCO₃ | 7.5% | (0.20, 0.95) | Low (1.13 GPa to 1.3 GPa) |

| PCL / Nanoclay | 10% | (0.30, 0.75) | Low |

| PLA / Nanoclay | 5% | (0.10, 0.99) | Moderate |

Solution: Improve dispersion by optimizing the surface chemistry of nanoparticles and processing parameters to reduce z and y values [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Nanoparticle Surface Functionalization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) | Silanization agent; introduces primary amine (-NH₂) groups onto silica and metal oxide surfaces for further conjugation [38] [39]. |

| Polyethyleneimine (PEI) | Cationic polymer; provides a positive surface charge for electrostatic adsorption of DNA, RNA, or for enhancing cellular uptake [39]. |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) Linkers | Provides a hydrophilic, steric barrier ("stealth" effect) to reduce protein corona formation and improve colloidal stability and circulation time [41]. |

| Click Chemistry Kits (e.g., Azide-Alkyne) | Enable efficient, site-specific, and bioorthogonal conjugation of targeting ligands (peptides, antibodies) to pre-functionalized nanoparticles [40] [39]. |

| Chitosan | Natural cationic polysaccharide; used as a biocompatible coating for mucoadhesion or controlled drug release [39]. |

Experimental Workflow and Strategy Selection

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for selecting and implementing surface modification strategies to reduce agglomeration.

Surface Modification Strategy Selection

Characterization Workflow for Modified Nanoparticles

After surface modification, a multi-technique approach is essential for thorough characterization. The following diagram maps this process.

Nanoparticle Characterization Workflow

In-situ Polymerization and Sol-Gel Processes for Intrinsic Dispersion

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Q1: My nanocomposite exhibits poor mechanical properties compared to literature values. What could be the cause?

This is frequently due to nanoparticle agglomeration, which creates stress concentration points and reduces the effective surface area for matrix interaction. Agglomeration negates the primary benefit of in-situ methods.

- Primary Cause: Inhomogeneous dispersion of nanoparticles within the polymer matrix, leading to weak interfaces and inefficient load transfer [43] [8].

- Solution:

- Verify Precursor Compatibility: Ensure your silica precursor (e.g., tetraethyl orthosilicate) is fully compatible with your monomer mixture (e.g., Bis-GMA/TEGDMA). Incompatibility can cause phase separation before gelation [43].

- Optimize Mixing Parameters: For sol-gel processes, control the hydrolysis and condensation rates by meticulously managing water content, catalyst concentration, and mixing speed. Ultrasonication during the initial mixing phase can help break up initial agglomerates [8].

- Characterize Dispersion: Use Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) to visually confirm nanoparticle dispersion, as demonstrated in studies achieving uniform composites [43].

Q2: I observe hazy gels or phase separation during the in-situ sol-gel process. How can I prevent this?

This indicates a lack of compatibility between the growing inorganic network and the organic polymer phase.

- Primary Cause: Rapid and uncontrolled condensation of silica, leading to macroscopic phase separation instead of a fine, interpenetrating network [43].

- Solution:

- Employ Coupling Agents: Use silane coupling agents (e.g., 3-methacryloxypropyl trimethoxysilane). These molecules possess alkoxy groups that co-condense with the silica precursor and organic methacrylate groups that can copolymerize with the matrix, creating a covalent link between phases [43].

- Control Reaction Kinetics: Slow down the condensation reaction by using milder catalysts or lower temperatures. This allows the organic and inorganic networks to form more harmoniously.

- Functionalize Monomers: In some cases, modifying the polymerizable monomers with groups that can interact with the silica precursor (e.g., via hydrogen bonding) can improve phase integration [43].

Q3: The volumetric shrinkage of my composite is unacceptably high. Can in-situ methods mitigate this?

Yes, a key advantage of well-executed in-situ sol-gel processes is significantly reduced volumetric shrinkage.

- Cause in Conventional Composites: Traditional composites using pre-formed fillers suffer from high shrinkage (often >2.2%) during the polymerization of the resin matrix alone [43].

- Solution with In-Situ Methods: The in-situ generation of silica creates an interpenetrating network (IPN) where the silica network forms concurrently with or prior to polymer matrix curing. This dual-network structure reduces overall shrinkage by occupying space before the organic polymerization. One study achieved a shrinkage as low as 0.5% compared to 2.2% for a commercial composite [43].

Q4: How does agglomerate size specifically affect the nanocomposite's modulus?

The size of nanoparticle agglomerates has a direct and pronounced impact on the final mechanical properties. Larger agglomerates drastically diminish reinforcement efficiency.

Table 1: Effect of Nanodiamond Agglomerate Size on Composite Modulus [11]

| Agglomerate Radius (Ragg) | Predicted Modulus Improvement |

|---|---|

| 10 nm | Up to 205% |

| 60 nm | Only 40% |

As shown in Table 1, smaller agglomerates are far more effective. Larger agglomerates act as defects and reduce the load-bearing cross-section of the matrix. Furthermore, a thick (t=20 nm) and tough (Ei=40 GPa) interphase zone around nanoparticles can enhance the composite modulus by 145%, while a thin interphase (t<5 nm) offers only a 50% improvement [11].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: When should I choose an in-situ polymerization approach over a simple physical blending method?

A: In-situ polymerization is superior when you need to achieve a maximally homogeneous dispersion at the nanoscale and strong nanoparticle-matrix adhesion. It is particularly beneficial for:

- Preventing agglomeration of high-surface-energy nanoparticles [8].

- Creating a co-continuous or interpenetrating organic-inorganic network [43].

- Applications requiring low volumetric shrinkage and high mechanical performance, such as dental restoratives or high-precision coatings [43].

Q: What are the critical parameters to monitor during a sol-gel reaction in a polymer matrix?

A: The most critical parameters are:

- pH: Dictates the rates of hydrolysis and condensation (acidic for linear chains, basic for particulate structures).

- Water-to-Precursor Ratio: Stoichiometrically controls the extent of the reaction.

- Temperature: Influences reaction kinetics and the stability of the colloidal sol.

- Catalyst Type and Concentration: Drives the reaction mechanism and speed. Consistent monitoring and control of these parameters are essential for reproducible results.

Q: My composite viscosity increases too rapidly, making processing difficult. What can I do?

A: A rapid viscosity increase suggests the sol-gel condensation is proceeding too quickly.

- Adjust Catalysis: Reduce the catalyst concentration or switch to a milder catalyst.

- Dilute the System: Temporarily dilute the reaction mixture with a compatible solvent to slow down particle collisions and network formation. Remember to remove the solvent later.

- Control Temperature: Lowering the reaction temperature can significantly slow the condensation kinetics.

Experimental Protocol: In-Situ Sol-Gel Formulation of a Dental Nanocomposite

This protocol is adapted from a published procedure for creating Bis-GMA/TEGDMA/silica composites with optimized properties [43].

1. Objective: To synthesize a dental nanocomposite with homogeneously dispersed silica nanoparticles via in-situ sol-gel process, resulting in high mechanical strength and low volumetric shrinkage.

2. Materials (Researcher's Toolkit):

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Equipment

| Item | Function / Specification |

|---|---|

| Bisphenol A-glycidyl methacrylate (Bis-GMA) | Base monomer for the resin matrix. |

| Triethylene glycol dimethacrylate (TEGDMA) | Diluent monomer to adjust viscosity. |

| Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) | Precursor for in-situ silica generation. |

| 3-Methacryloxypropyl trimethoxysilane | Silane coupling agent for interfacial bonding. |

| Photo-initiator (e.g., Camphorquinine) | To initiate radical polymerization upon light exposure. |

| HCl or NH₄OH | Catalyst for sol-gel reactions. |

| Ethanol | Solvent for the sol-gel process. |

| Ultrasonicator | To ensure initial homogeneous mixing. |

| UV Light Curing Unit | For final photopolymerization. |

3. Methodology:

Monomer and Precursor Preparation:

- Prepare the organic resin matrix by mixing Bis-GMA and TEGDMA monomers in a 70:30 weight ratio.

- Add the photo-initiator system and mix until fully dissolved.

- Functionalize the monomer mixture by adding 1-2 wt% of the silane coupling agent.

In-Situ Sol-Gel Reaction:

- Add Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) to the monomer mixture. The typical filler loading target is 50 wt% in the final composite [43].

- Introduce a calculated amount of acidified water (using HCl as a catalyst) in a water:TEOS molar ratio of approximately 4:1 to initiate hydrolysis.

- Stir the mixture continuously at room temperature for 24 hours. This allows for the hydrolysis of TEOS and the initial condensation of silica nanoparticles within the organic medium.

Degassing and Casting:

- Place the resulting viscous sol under vacuum to remove any entrapped air and the ethanol by-product formed during hydrolysis.

- Pour the degassed mixture into appropriate molds (e.g., Teflon molds for mechanical test specimens).

Polymerization:

- Cure the composite using a UV light curing unit at a specific wavelength and intensity (e.g., 470 nm, 1000 mW/cm²) for 60 seconds per surface to photopolymerize the methacrylate matrix.

Post-curing and Characterization:

- Optional: Post-cure the samples in an oven at 60°C for 24 hours to ensure complete conversion.

- Characterize the final composite using FTIR to confirm network formation, TEM/SEM to analyze silica dispersion, and mechanical testing (e.g., three-point bending for flexural strength).

Performance Data and Workflow

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The following table summarizes key mechanical properties achievable with an optimized in-situ sol-gel composite compared to a commercial material, demonstrating the efficacy of the method [43].

Table 3: Mechanical Properties of In-Situ vs. Commercial Composite