Strategies for Improving Thermal Stability in Polymers: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a systematic examination of methodologies to enhance polymer thermal stability, addressing critical needs in pharmaceutical development and biomedical applications.

Strategies for Improving Thermal Stability in Polymers: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a systematic examination of methodologies to enhance polymer thermal stability, addressing critical needs in pharmaceutical development and biomedical applications. Covering fundamental degradation mechanisms, material design strategies, stabilization techniques, and advanced validation methods, the content synthesizes current research to guide the selection and optimization of thermally robust polymers. Special emphasis is placed on pharmaceutical formulation challenges, including polymer-excipient interactions and processing stability, with practical insights for developing advanced drug delivery systems that maintain integrity under thermal stress.

Understanding Polymer Thermal Degradation: Mechanisms and Stability Fundamentals

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental definition of thermal stability in materials science? Thermal stability describes a material's ability to retain its original properties (mechanical, electrical, chemical) when exposed to elevated temperatures over extended periods. It is not a single property but a performance characteristic influenced by temperature, time, load conditions, and environment. The key is resistance to permanent property changes caused by heat [1] [2].

2. Why is thermal stability a critical parameter for polymers in demanding applications? Most polymers experience degraded performance at high temperatures. For example, their charge-discharge efficiency can drop significantly, and mechanical strength can be permanently lost. High thermal stability allows polymers to function reliably in harsh environments like those in aerospace, electronics, and energy storage [3] [2].

3. What are the common degradation mechanisms that reduce thermal stability? Common mechanisms include chemical decomposition, coarsening of precipitates (in composites), aggregation (in biologics), and undesirable chemical modifications like oxidation or fragmentation. In polymers, charge transfer complexes can also form at high temperatures, increasing electrical conductivity and reducing insulation properties [4] [3] [2].

4. What experimental techniques are used to assess thermal stability? Common techniques include:

- Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA): Measures mass change as a function of temperature to determine decomposition temperatures [1].

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): Identifies thermal transitions like glass transition temperature (Tg) and melting point (Tm) [1].

- Accelerated Aging Studies: Exposes materials to elevated temperatures to model long-term stability and predict service life [4].

5. What strategies can improve the thermal stability of polymers? Advanced strategies include elemental doping, surface coating, creating concentration-gradient structures, and microstructural engineering. For polyimides, molecular-level strategies like donor-acceptor rearrangement through crosslinking have been shown to simultaneously enhance heat resistance and electrical insulation [5] [3].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent thermal stability results across different batches of a polymer composite.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent dispersion of fillers or additives. | Perform scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to examine filler distribution in the polymer matrix. | Optimize the mixing or compounding procedure to ensure uniform dispersion. |

| Variations in crosslinking density. | Use solvent swelling tests or UV-vis spectroscopy to determine the crosslinking degree [3]. | Strictly control the time and temperature of the crosslinking/curing process. |

| Residual solvent or moisture content. | Use thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) to check for low-temperature weight loss indicative of volatiles [1]. | Implement a standardized and thorough drying process before testing. |

Problem: A polymer film shows excellent short-term thermal stability but rapid degradation during long-term aging.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Slow, progressive oxidative degradation. | Conduct aging tests in different atmospheres (e.g., nitrogen vs. air) to isolate oxidation. | Incorporate antioxidant additives into the polymer formulation [1]. |

| Antioxidant depletion over time. | Model antioxidant depletion kinetics from accelerated aging data [6]. | Reformulate with a higher initial concentration or more stable antioxidants. |

| Physical ageing or creep. | Use rheological assessments to monitor viscoelastic properties over time at service temperatures [6]. | Explore strategies to increase the polymer's glass transition temperature (Tg). |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Assessing Hydrolytic Degradation in Polymer Blends

Objective: To evaluate the compatibility and hydrolytic degradation of polymer blends, such as Poly(glycolic Acid)/Poly(butylene succinate) (PGA/PBS) blends [6].

Materials:

- Polymer blend samples (e.g., PGA/PBS)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution or deionized water (pH may be adjusted)

- Controlled temperature oven or water bath

- Analytical balance

- Rheometer

- DSC and TGA equipment

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare uniform films or pellets of the polymer blend.

- Initial Characterization: Measure the initial molecular weight, thermal properties (via DSC), and rheological properties.

- Hydrolytic Aging: Immerse weighed samples in PBS solution in sealed containers. Place containers in an oven at a predetermined temperature (e.g., 37°C, 60°C).

- Sampling: Remove samples in triplicate at fixed time intervals (e.g., 1, 2, 4, 8 weeks).

- Analysis:

- Mass Loss: Dry the samples to constant weight and calculate percentage mass loss.

- Molecular Weight: Use Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) to track changes.

- Thermal and Rheological Properties: Perform DSC, TGA, and rheological analysis to monitor changes in Tg, melting behavior, and viscosity/compatibility [6].

- Data Modeling: Fit degradation data to kinetic models (e.g., Arrhenius equation) to predict long-term behavior.

Protocol for Enhancing Thermal Stability via Molecular Rearrangement

Objective: To improve the thermal stability and electrical insulation of a polyimide through benzyl-induced crosslinking to create a preferred layer packing (PLP) structure [3].

Materials:

- Dianhydride monomer (e.g., BPADA)

- Diamine monomers (e.g., phenylenediamine (PDA) and 2,3,5,6-tetramethyl-1,4-phenylenediamine (TPD))

- Suitable solvent (e.g., N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP))

- FT-IR Spectrometer

- Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

- UV-vis Spectrometer

- Equipment for electrical conductivity and dielectric breakdown measurement

Method:

- Polymer Synthesis: Synthesize the polyimide (e.g., TPEI) from BPADA and TPD monomers via thermal imidization in a temperature range from 70°C to 290°C in air.

- Crosslinking: The benzyl functional groups in the polymer film will undergo a thermo-oxidation crosslinking reaction during the high-temperature imidization step.

- Crosslinking Degree Measurement:

- Structural Characterization:

- Use FT-IR to confirm the chemical structure and complete imidization.

- Use AFM to verify the film is flat and defect-free.

- Performance Testing:

- Measure glass transition temperature (Tg) via DSC.

- Evaluate electrical conductivity and discharged energy density at elevated temperatures (e.g., 200°C, 250°C).

This protocol's workflow for creating a stable polymer structure is summarized below.

Quantitative Data on Thermal Stability

Table 1: Thermal Stability Performance of Selected Advanced Materials

| Material System | Application Context | Key Stability Metric | Performance Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyimide (TPEI) via Benzyl Crosslinking | Dielectric Capacitors | Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) & Energy Density at 250°C | Tg increased to ~290°C; Discharged energy density of 3.04 J cm⁻³ with >90% efficiency at 250°C [3]. | [3] |

| All-Polymer Ternary Blend (OPV) | Organic Photovoltaics | Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) Retention | Retained 80% of initial PCE after 1500 hours at 120°C [7]. | [7] |

| Ni-Rich Layered Cathodes (with synergistic modification) | Lithium-Ion Batteries | Resistance to Thermal Runaway | Synergistic high-entropy doping and coating in single-crystal structures significantly enhances thermal stability [5]. | [5] |

| Enzyme (PpLDH via Short-loop Engineering) | Biocatalysis | Half-life at Elevated Temperature | Half-life increased by 9.5x compared to wild type [8]. | [8] |

Table 2: Essential Reagent Solutions for Thermal Stability Research

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Example Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Crosslinking Diamine Monomers (e.g., TPD) | Enables benzyl-induced crosslinking during imidization, leading to a Preferred Layer Packing (PLP) structure that decouples thermal stability from electrical conduction [3]. | Enhancing thermal stability and electrical insulation in polyimide dielectrics. |

| High-Crystallinity Polymer (e.g., D18) | Acts as a ternary component to optimize active layer morphology, balancing charge transport and improving morphological stability under thermal stress [7]. | Improving thermal stability in all-polymer organic photovoltaics (OPVs). |

| High-Entropy Doping Elements | Suppresses structural degradation and phase transition at the particle surface and bulk of cathode materials at high voltages and temperatures [5]. | Improving thermal stability of Ni-rich cathodes in lithium-ion batteries. |

| Hydrophobic Amino Acids (e.g., Tyr, Phe, Trp) | Used for cavity-filling mutations in short-loop enzyme engineering; large side chains enhance hydrophobic interactions and rigidify the protein scaffold [8]. | Enhancing kinetic and thermodynamic thermal stability of enzymes. |

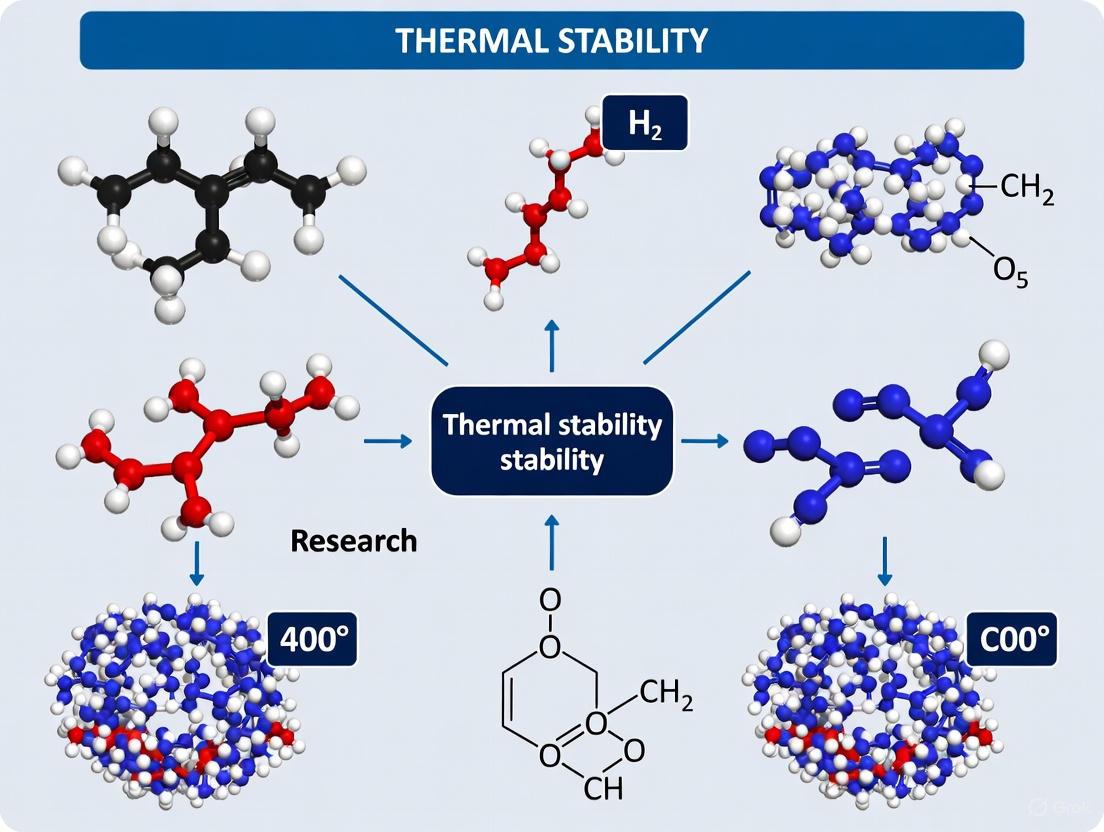

Advanced Modification Strategy Diagram

The following diagram outlines the core strategies for improving thermal stability, as identified in recent literature, particularly for Ni-rich layered cathodes [5]. This multi-faceted approach is also conceptually applicable to polymer research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between chain scission and depolymerization? Chain scission refers to the fragmentation of long polymer chains into shorter segments by breaking the covalent bonds in the backbone [9]. This can occur randomly along the chain (random scission) or at the chain ends (chain-end scission) [10] [11]. Depolymerization, a specific form of chain-end scission, is the reverse of polymerization, where a polymer is systematically unzipped to regenerate its constituent monomers [12]. While chain scission generally leads to lower molecular weight polymer fragments, depolymerization aims for high monomer yield, which is crucial for chemical recycling [12].

Q2: How does the polymer's physical state (e.g., soluble vs. insoluble) influence its degradation mechanism? Recent meta-analysis studies show that a polymer's solubility is a critical factor. Soluble polymers tend to degrade primarily via chain-end scission, while insoluble polymers (such as plastics in aqueous environments) more frequently undergo random chain scission [10]. This physical state can be a more significant determinant of the degradation pathway than molecular chemistry alone.

Q3: What is the "ceiling temperature" (Tc), and why is it important for depolymerization? The ceiling temperature (Tc) is a key thermodynamic concept where the rates of polymerization and depolymerization for a given monomer are equal [12]. Above this temperature, depolymerization is favored, making monomer regeneration feasible. The Tc is not a fixed value but depends on monomer concentration; lower equilibrium monomer concentrations lead to a higher Tc [12]. Understanding Tc is essential for designing effective depolymerization systems.

Q4: What role does chain mobility play in enzymatic depolymerization? For enzymatic hydrolysis to occur, the polymer chain must have sufficient mobility to interact with the enzyme's active site. A key parameter is the local glass transition temperature of the solvent-soaked material (Tg,s). When the operational temperature exceeds Tg,s, chain mobility increases significantly, facilitating enzyme access and drastically accelerating the degradation rate [13].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Inconsistent Depolymerization Yields

- Potential Cause: The experimental temperature is below the effective ceiling temperature for the system, or the monomer is not being removed efficiently from the reaction equilibrium.

- Solution: Revisit the thermodynamic parameters of your polymer. According to the law of mass action, depolymerization is favored by removing monomer from the system [12]. Ensure your reaction setup allows for continuous removal of regenerated monomer to shift the equilibrium towards depolymerization.

Problem: Unexpected Molecular Weight Profile During Degradation

- Potential Cause: The dominant scission mode may differ from assumptions. For example, expecting random scission while the polymer is primarily undergoing end-chain scission, or vice versa.

- Solution: Analyze time-dependent molecular weight data with both random and chain-end scission models [10]. A rapid initial drop in molecular weight suggests random scission, while a more gradual decrease is characteristic of chain-end scission (depolymerization) [11]. Correlate this with the polymer's solubility, as it is a key indicator of the likely scission mode [10].

Problem: Slow or Inefficient Enzymatic Hydrolysis

- Potential Cause: Insufficient chain mobility at the polymer-water interface, preventing enzyme access.

- Solution: Consider strategies to lower the local glass transition temperature (Tg,s) of the polymer, for instance, by using solvents that plasticize the polymer or by designing polymer blends that increase chain mobility at the desired degradation temperature [13].

Quantitative Data on Degradation Mechanisms

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of the primary degradation mechanisms.

Table 1: Characteristics of Primary Polymer Degradation Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Description | Primary Triggers | Effect on Molecular Weight | Common Polymer Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chain Scission (Random) | Covalent bonds are broken at random points along the polymer backbone [9] [11]. | Heat, mechanical stress, oxygen [11]. | Rapid decrease [11]. | Polyolefins, PVC [9]. |

| Depolymerization (Chain-End Scission) | Sequential unzipping of monomer units from the chain end, reversing the polymerization process [12] [11]. | Heat (above ceiling temperature) [12]. | Slow, gradual decrease; high monomer yield [11]. | Polystyrene (PS), Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) [12] [14]. |

| Side-Group Elimination | Removal of side groups attached to the polymer backbone, often leading to unsaturation or char formation [11]. | Heat [11]. | Changes in chemical structure; can lead to cross-linking. | Poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC). |

Table 2: Bond Dissociation Energies (BDEs) of Common Polymer Bonds [11]

| Bond | Bond Dissociation Energy (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|

| C–C (aliphatic) | 284 - 368 |

| C–C (aromatic) | 410 |

| C–O | 350 - 389 |

| C–H | 381 - 410 |

| C–Cl | 326 |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Identifying Chain Scission Mode via Molecular Weight Kinetics

Objective: To determine whether a polymer degrades primarily via random scission or chain-end scission (depolymerization) by monitoring molecular weight over time [10].

Materials:

- Polymer sample

- Relevant degradation environment (e.g., oven, UV chamber, enzymatic solution)

- Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) system with refractive index and light scattering detectors

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare multiple identical thin films or solutions of the polymer to ensure consistent thermal and mass transfer properties.

- Degradation Experiment: Expose samples to the controlled degradation environment (e.g., specific temperature, pH, enzyme concentration). Remove samples at predetermined time intervals.

- Molecular Weight Analysis: Analyze each sample using GPC to determine the molecular weight (Mn, Mw) and dispersity (Đ) at each time point.

- Data Fitting: Fit the time-dependent molecular weight data to kinetic models for random scission and chain-end scission [10].

- Interpretation: The model that best fits the experimental data indicates the dominant scission mode. A rapid drop in molecular weight supports random scission, while a slower, more linear decrease suggests chain-end scission [11].

Protocol 2: Determining the Impact of Solubility on Degradation Pathway

Objective: To experimentally validate the correlation between polymer solubility and its dominant chain scission mode [10].

Materials:

- Polymer samples with varying solubility (e.g., soluble in a solvent vs. insoluble gel or solid)

- Solvents of different polarities

- Standard equipment for degradation studies (as in Protocol 1)

Methodology:

- Sample Conditioning: Prepare two sets of polymer samples: one as a soluble fraction in a good solvent and the other as an insoluble phase (e.g., a cross-linked gel or a solid film in a non-solvent).

- Parallel Degradation: Subject both sets of samples to identical degradation conditions.

- Analysis and Comparison: Monitor the molecular weight change and product distribution (e.g., monomer vs. oligomer yield) for both systems.

- Result Correlation: The soluble fraction is expected to show a stronger tendency for chain-end scission, while the insoluble fraction will likely exhibit random scission behavior [10].

Mechanism and Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Primary degradation mechanisms and their products. The process initiates with the formation of a macro-radical, which then propagates via one of three primary pathways, leading to distinct product profiles.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Studying Polymer Degradation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Heat Stabilizers | Used to protect polymers from thermal degradation during processing or as a control in degradation studies [15]. |

| Model Polymers | Well-characterized polymers like Polylactide (PLA) or Polystyrene (PS) are used as benchmarks to study specific degradation mechanisms [10] [13]. |

| Proteinase K | A highly effective enzyme used in studies of enzymatic hydrolysis and depolymerization of polyesters like PLA [13]. |

| Nanochitin (NCh) | An eco-friendly additive that can be functionalized to introduce acidic species into a polymer bulk, enhancing acidic hydrolysis from within the material [13]. |

| GPC/SEC Standards | Narrow dispersity polymer standards are essential for calibrating Gel Permeation or Size Exclusion Chromatography systems to accurately track molecular weight changes during degradation [10] [11]. |

Thermo-oxidative degradation is a complex chemical process where combined heat and oxygen exposure cause irreversible damage to polymeric materials, fundamentally altering their molecular structure and mechanical properties. Unlike inert atmosphere degradation, the presence of oxygen significantly accelerates chain scission and crosslinking reactions through free radical mechanisms, leading to premature material failure. Understanding oxygen's role is particularly crucial for developing thermal stability polymers capable of withstanding extreme environments in aerospace, automotive, and electronics applications. This technical resource provides methodologies, troubleshooting guidance, and experimental protocols to help researchers investigate, quantify, and mitigate these degradation processes in their polymer systems.

Key Mechanisms & Experimental Evidence

The Diffusion-Limited Oxidation (DLO) Effect

A critical phenomenon in thermo-oxidative degradation is Diffusion-Limited Oxidation (DLO), where oxygen consumption at the material surface exceeds its diffusion rate into inner layers, creating significant oxidation gradients. Research on natural rubber (NR) and natural rubber/butadiene rubber (NR/BR) laminates demonstrates that DLO causes uneven degradation profiles with substantially higher crosslink density and lower sol fraction at specimen centers compared to surfaces [16].

Quantitative Evidence of DLO in Rubber Systems [16]

| Material | Temperature Range | Key Observation | Impact on Oxygen Diffusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Rubber (NR) | 150-240°C | Distinct decrosslinking behaviors at higher temperatures. | - |

| NR/Butadiene Rubber (NR/BR) | 150-240°C | Recrosslinking decreases oxygen permeability coefficient with rising temperature. | Creates barrier, hindering inner layer diffusion and causing inhomogeneous degradation. |

The fundamental challenge is that as thermo-oxidative degradation progresses, re-crosslinking reactions can decrease the oxygen permeability coefficient, making it increasingly difficult for oxygen to diffuse into the material's inner layers and resulting in heterogeneous degradation [16]. This effect is pronounced in complex polymer systems like tire rubber, where synthetic and natural rubbers coexist.

Mechanistic Workflow for Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for analyzing thermo-oxidative degradation, from the initial challenge to key mechanistic insights.

Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful experimentation requires specific materials and analytical tools. The table below catalogs essential items referenced in recent studies for investigating thermo-oxidative degradation.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Rubber (SCR-5) | Model polymer for degradation studies [16] | ρ = 0.913 g·cm⁻³ |

| Butadiene Rubber (BR9000) | Model synthetic rubber for co-degradation studies [16] | ρ = 0.902 g·cm⁻³ |

| 1,5,7-Triazabicyclo[4.4.0]dec-5-ene (TBD) | Organic catalyst for controlled degradation of condensation polymers [17] | Dual hydrogen-bonding activation mechanism |

| Polyethersulfone | Polymer additive studied for its impact on thermo-oxidative stability [18] | Used as a toughener |

| Aluminum Diethyl Phosphinate (AlPi) | Polymer additive studied for its impact on thermo-oxidative stability [18] | Used as a flame retardant |

| Toluene | Solvent for analysis (e.g., swelling tests) [16] | Commercial grade |

Core Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Tracking Degradation Kinetics in Rubber Laminates

This protocol, adapted from He et al., investigates DLO effects in rubber systems [16].

Materials Preparation:

- Formulate rubber compounds using NR (SCR-5) and/or BR (BR9000) with standard additives (e.g., sulfur, stearic acid, ZnO, CZ) [16].

- Vulcanize the compounded rubber into thin laminates under predetermined temperature and pressure conditions.

Thermo-Oxidative Aging:

- Place laminate specimens in a forced-air circulation oven, ensuring adequate air flow around samples.

- Expose specimens to temperatures in the range of 150°C to 240°C for varying durations (e.g., 0 to 120 minutes) [16].

- Remove samples at designated time intervals for immediate analysis to prevent post-aging changes.

Post-Aging Analysis:

- Sol Fraction Analysis: Extract degraded samples in toluene using a Soxhlet apparatus for 24 hours. Dry the insoluble residue and calculate the sol fraction as the percentage of mass lost, indicating chain scission [16].

- Crosslink Density Measurement: Perform equilibrium swelling tests on the dried residue (gel fraction) from sol fraction analysis. Calculate the crosslink density using the Flory-Rehner equation based on solvent uptake [16].

- Spatial Profiling: Carefully section the aged laminates into layers (e.g., surface, sub-surface, core). Perform sol fraction and crosslink density measurements on each layer to map the degradation profile and quantify DLO effects [16].

- Chemical Analysis: Use FTIR and UV-Vis spectroscopy on each layer to trace the evolution of oxidative products like carbonyl groups and hydroperoxides [16].

Protocol: Lifetime Prediction via Model-Free Kinetics

This protocol, based on epoxy resin/composite research, uses TGA for service life prediction [18].

Data Acquisition via TGA:

- Prepare samples as finely powdered pieces to ensure uniform heat and mass transfer.

- Using a Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA), perform dynamic (non-isothermal) experiments in synthetic air or oxygen atmosphere. Use multiple constant heating rates (e.g., 5, 10, 15, 20 K/min) from ambient to beyond degradation temperatures [18].

Kinetic Analysis:

- Flynn-Wall-Ozawa (FWO) Method:

- For each heating rate, plot mass conversion (α) versus temperature.

- At constant conversion values, plot log(β) against 1/T, where β is the heating rate and T is the absolute temperature.

- The activation energy (Eₐ) is proportional to the slope of this plot, allowing for Eₐ calculation without prior knowledge of the reaction model [18].

- Friedman Method:

- Differentiate the TGA mass loss data to obtain the reaction rate (dα/dt) at constant conversion levels for different heating rates.

- Plot ln(dα/dt) against 1/T for each conversion.

- The slope of this plot gives -Eₐ/R, providing a model-free estimate of the activation energy [18].

Lifetime Extrapolation:

- Using the determined kinetic parameters (e.g., Eₐ), extrapolate the short-term high-temperature TGA data to predict the time to a specific degree of degradation (e.g., 5% mass loss) at lower, use-temperature conditions.

- Critical Note: Correlate these predictions with long-term isothermal oven aging experiments in an air atmosphere to validate the accuracy of the model under real-world oxidative conditions [18].

Troubleshooting FAQs

FAQ 1: Why is my polymer degrading unevenly, with the surface more severely degraded than the core?

- Problem: This is a classic symptom of Diffusion-Limited Oxidation (DLO) [16].

- Solution:

- Reduce Temperature: Lower the aging temperature to decrease the oxidation reaction rate, allowing oxygen to more effectively diffuse into the core before being fully consumed at the surface. Lower temperatures and prolonged treatment times are recommended to enhance homogeneous degradation [16].

- Verify Oven Atmosphere: Ensure forced air circulation in the aging oven to maintain a uniform oxygen concentration around the sample.

- Profile the Degradation: Confirm the hypothesis by sectioning the sample and measuring properties like crosslink density or carbonyl index from surface to core [16].

FAQ 2: My lifetime predictions from short-term TGA data are too optimistic compared to long-term oven aging. What is wrong?

- Problem: A common issue arises from neglecting oxidative mechanisms and DLO effects in kinetic models. TGA predictions based on inert atmosphere data or simple kinetic models fail to capture the complex, often autocatalytic, nature of thermo-oxidative degradation [18].

- Solution:

- Use Oxidative Atmosphere: Perform all TGA experiments in synthetic air or oxygen, not nitrogen, to simulate the correct degradation pathway [18].

- Apply Model-Free Methods: Use isoconversional methods like Flynn-Wall-Ozawa and Friedman, which are more flexible and do not require assumed reaction models, making them better suited for complex oxidative degradation [18].

- Correlate with Long-Term Data: Always validate accelerated TGA predictions with real-time oven aging data at multiple temperatures to calibrate your models [18].

FAQ 3: How can I achieve more controlled and efficient chemical recycling of condensation polymers like PET or PC?

- Problem: Standard thermal degradation often leads to random scission, producing a complex mixture of products that are difficult to repolymerize.

- Solution:

- Employ Organic Catalysts: Utilize potent transesterification catalysts like TBD (1,5,7-triazabicyclo[4.4.0]dec-5-ene) or DBU [17].

- Mechanism: These superbases activate both the ester carbonyl group and the nucleophile (e.g., alcohol or amine) via dual hydrogen-bonding, enabling highly selective depolymerization to valuable monomers like BHET or terephthalamides [17].

- Optimize Conditions: Reactions can be efficient (e.g., completed in 2 hours with 1 mol% DBU at 190°C for PET glycolysis), providing a viable path for chemical recycling and upcycling [17].

Advanced Visualization: Oxygen Diffusion & Degradation

The following diagram details the coupled chemical and physical processes during thermo-oxidative degradation, leading to heterogeneous material properties.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Poor Thermal Stability in Polymer Formulations

Problem: Your polymer sample undergoes significant degradation at target application temperatures below 300°C.

Explanation: The thermal stability of a polymer is directly influenced by the strength of its chemical bonds and the stability of its cyclic structures. Weak linkages or non-aromatic rings in the chain can become points of failure when exposed to heat.

Solution: Incorporate aromatic or heteroaromatic rings with high resonance energy into the polymer backbone.

- Action 1: Replace aliphatic segments with aromatic units like phenylquinoxaline, which demonstrates exceptional thermal stability in high-performance polymers [19].

- Action 2: Utilize heterocycles like 1,3,4-oxadiazole, which is electronically similar to a p-phenylene structure but offers superior thermal resistance and does not contain easily degraded hydrogen atoms [19].

- Action 3: Ensure synthesis conditions fully form the aromatic system, as incomplete cyclization can leave vulnerable single bonds.

Guide 2: Managing Decomposition Enthalpy in Energetic Materials

Problem: An experimental heterocyclic compound exhibits an undesirably high and sharp exothermal decomposition peak.

Explanation: A high decomposition enthalpy (ΔHdec) with a narrow temperature range can indicate potential safety hazards. The nitrogen-to-carbon (N/C) ratio in heterocycles is a key factor.

Solution: Select heterocyclic stabilizers with a lower N/C ratio to manage energy release.

- Action 1: Prefer pyrazoles over triazoles. Pyrazole-stabilized compounds have shown significantly lower decomposition enthalpies (e.g., 2.5 kJ/mol) compared to triazole-stabilized ones (e.g., >116 kJ/mol) [20].

- Action 2: If a triazole is necessary, specific substitution patterns can improve stability. A methyl group at the N2 position of the triazole can increase the peak decomposition temperature (Tpeak) and lower ΔHdec [20].

- Action 3: Monitor thermal behavior using Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) to detect sharp exotherms, which may require reformulation for safe handling.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why do aromatic rings confer greater thermal stability to a molecule than non-aromatic rings?

Aromatic rings possess exceptional stability due to resonance energy—the energy released from the delocalization of π electrons across the cyclic structure [21]. This delocalization results in a more stable, lower-energy molecule compared to a non-aromatic system with the same number of electrons. For example, benzene is about 36 kcal/mol more stable than a hypothetical cyclohexatriene without electron delocalization [21]. This enhanced stability requires more energy input to break the molecular structure, thereby raising the decomposition temperature.

FAQ 2: How does the presence of a heteroatom (e.g., N, O, S) in an aromatic ring influence thermal stability?

The influence is complex and depends on the heteroatom's properties and the ring's structure. Heteroatoms can alter the electron distribution within the ring. In some high-performance polymers, heterocycles like phenylquinoxaline and 1,3,4-oxadiazole are used specifically for their thermal and thermo-oxidative stability [19]. However, in hypervalent iodine compounds, the type of N-heterocycle used as a stabilizing ligand significantly impacts thermal stability; triazoles (high N/C ratio) lead to lower decomposition temperatures, while pyrazoles and thiazoles offer higher stability [20].

FAQ 3: What is the relationship between covalent bond strength and the thermal stability of a solid material?

Thermal stability in covalent solids is directly linked to the strength of the covalent bonds forming the network [22]. Breaking these bonds requires substantial energy. Solids with strong, multidirectional covalent bonding (e.g., diamond, silicon carbide) consequently have very high melting points and are stable at extreme temperatures. Stronger bonds, such as shorter double or triple bonds, require more energy to break than single bonds, directly increasing the thermal stability of compounds containing them [23].

FAQ 4: Can an aromatic ring remain stable even if it is not perfectly planar?

Yes, to a significant extent. Research shows that aromatic rings are structurally flexible and can undergo considerable in-plane and out-of-plane distortions at room temperature with only a small energy cost (1-2 kcal/mol) [24]. While such deformations can cause instantaneous fluctuations in geometric indices of aromaticity like HOMA, the time-averaged aromatic character remains high. This indicates that aromaticity, a key source of stability, is somewhat resilient to thermal distortions.

Table 1: Thermal Decomposition Data of N-Heterocycle-Stabilized Iodanes

| Stabilizing Heterocycle | Example Compound | Peak Decomposition Temp (Tpeak, °C) | Decomposition Enthalpy (ΔHdec, kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benziodoxolone (O-stabilized) | 1 | 206.8 | 72.9 [20] |

| Triazole | 2 | 120.8 | 116.3 [20] |

| N2-methyl Triazole | 4 | 152.4 | Lower than 2, 3, 5 [20] |

| Pyrazole | 6 | 168.9 | 2.5 [20] |

| Benzimidazole | 9 | 193.9 | 58.5 [20] |

| Thiazole | 12 | 173.4 | 44.9 [20] |

Table 2: Thermal Stability of Heterocyclic Aromatic Polyethers

| Polymer | Key Structural Components | 5% Mass Loss Temp in Air (°C) | 5% Mass Loss Temp in Helium (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ox-BisA | 1,3,4-oxadiazole, isopropylidene | >430 | >420 [19] |

| Ox-Q | Phenylquinoxaline, 1,3,4-oxadiazole | >430 | >420 [19] |

| Q-DFB | Phenylquinoxaline | >430 | >420 [19] |

Table 3: Average Bond Energies

| Bond | Bond Energy (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|

| H-H | 436 [23] |

| C-C | ~347 [23] |

| C=C | ~611 [23] |

| C≡C | ~837 [23] |

| C-H | 415 [23] |

| C-O | ~360 [23] |

| C=O | ~799 [23] |

| C-N | ~305 [23] |

| C≡N | ~891 [23] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evaluating Thermal Stability via Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) and Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Purpose: To determine the decomposition temperature and enthalpy of a new heterocyclic compound or polymer.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Place 2-10 mg of the pure, dry solid sample into an open alumina or platinum crucible.

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate the TGA/DSC instrument for temperature and cell constants using standard references like indium.

- Experimental Run: Under an inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen or helium) and a flow rate of 50 mL/min, heat the sample from room temperature to 600-800°C at a controlled heating rate (e.g., 10 °C/min).

- Data Analysis:

- Onset Temperature (Tonset): Determine the temperature at which the sample begins to lose mass from the TGA curve.

- Peak Decomposition Temperature (Tpeak): Identify the maximum rate of mass loss from the derivative TGA (DTG) curve or the peak of the exotherm/endotherm in the DSC curve.

- Decomposition Enthalpy (ΔHdec): Integrate the area under the DSC peak associated with decomposition to calculate the energy change in kJ/mol [20] [19].

Protocol 2: Assessing Aromaticity via Geometric Index (HOMA) from Computed Structures

Purpose: To quantify the aromatic character of a ring in a molecule, which correlates with its stability.

Methodology:

- Geometry Optimization: Perform a full geometry optimization of the molecule using a computational method like DFT (e.g., B3LYP/6-311+G level) to find its ground-state structure. Confirm the structure is a true minimum (no imaginary frequencies) via frequency analysis [24].

- Bond Length Measurement: Extract the lengths of all bonds in the ring of interest from the optimized geometry.

- HOMA Calculation: Calculate the Harmonic Oscillator Model of Aromaticity (HOMA) index using the formula: HOMA = 1 - (α/n) * Σ(Ropt, i - Ri)² where α is a normalization constant, n is the number of bonds, Ropt, i is the optimal bond length for full aromaticity, and Ri is the calculated bond length. A HOMA value closer to 1 indicates high aromaticity [24].

Visualizations

A thermal degradation pathway for benzene, a model aromatic compound, shows how initial H-abstraction leads to ring opening products through key radical intermediates [25].

The thermal stability of a molecule is determined by the interplay of aromaticity (and its associated resonance energy), the strength of its covalent bonds, and the nature of any heterocycles present [21] [20] [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Investigating Thermal Stability

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role |

|---|---|

| Phenylquinoxaline-based monomers | Incorporates a highly thermally stable aromatic heterocycle into polymer backbones [19]. |

| 1,3,4-Oxadiazole-based monomers | Provides a symmetric, thermoresistant heterocycle with an electron-withdrawing character for polymers [19]. |

| Pyrazole-stabilized ligands | Offers a favorable balance of thermal stability and reactivity for metal complexes or hypervalent molecules [20]. |

| Thiazole-stabilized ligands | A good compromise for thermal stability and chemical reactivity in molecular design [20]. |

| Inert Atmosphere (He/N₂) | Essential for TGA/DSC to study pure thermal degradation without oxidative side reactions [19]. |

FAQs: Core Concepts and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between decomposition temperature and activation energy?

The decomposition temperature is an experimentally observed value, typically the temperature at which a material begins to lose mass rapidly during thermal analysis. It is a direct indicator of a material's thermal stability under specific test conditions [26].

The activation energy (Ea) is a kinetic parameter representing the minimum energy barrier that must be overcome for the decomposition reaction to occur. It provides insight into the intrinsic thermal stability and the reaction's sensitivity to temperature, helping to predict material lifetime and behavior under different thermal conditions [27] [28].

FAQ 2: Why do I get different activation energy values when using different kinetic methods?

Different kinetic methods (e.g., model-free isoconversional vs. model-fitting) have distinct underlying assumptions and handle experimental data differently. For instance:

- Isoconversional methods (like Ozawa-Flynn-Wall) calculate Ea at specific degrees of conversion without assuming a reaction model, revealing complex multi-step mechanisms [29] [28].

- Model-fitting methods assume a specific reaction pathway (e.g., first-order) and can be sensitive to experimental noise [30].

Variations are normal. Using multiple methods and cross-validating results provides a more robust understanding of the decomposition kinetics [29] [30].

FAQ 3: My TGA shows a multi-step decomposition. How do I interpret the activation energy?

Multi-step decomposition indicates competing or sequential reactions (e.g., dehydration, polymer backbone scission, side-group loss). In such cases:

- The overall single value of activation energy has limited meaning.

- Apply isoconversional methods to calculate how Ea changes with the degree of conversion (α). This "Ea vs. α" plot helps identify the different dominant mechanisms at various stages of decomposition [29] [31].

- Use complementary techniques like evolved gas analysis (EGA-FTIR) to identify the gaseous products at each mass loss step, linking mass change to chemical events [32].

Troubleshooting Guide 1: Inconsistent Decomposition Temperatures

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Decomposition temperature (Td) varies significantly between identical samples. | Sample preparation inhomogeneity: In polymers, factors like nanoparticle agglomeration (e.g., in PMMA/NiO composites) [33] or inconsistent crosslink density can create local thermal stability variations. | Standardize mixing and processing protocols. Use techniques like SEM to verify filler dispersion [33]. |

| Td shifts to lower temperatures with repeated testing. | Material degradation during processing or testing: Some materials, like active pharmaceuticals (e.g., Nifedipine), may begin slow decomposition below their melting point [26]. | Minimize thermal history before analysis. Use a protective inert atmosphere (N2, Ar) during TGA to prevent oxidative degradation [29] [34]. |

| Td differs from literature values for the same polymer. | Different heating rates: A higher heating rate shifts Td to a higher temperature due to thermal lag [27]. | Always report the heating rate used. For comparisons, ensure identical experimental conditions or use kinetic methods to extrapolate data. |

Troubleshooting Guide 2: Challenges in Kinetic Analysis and Lifetime Prediction

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor fit of kinetic data to a single Ea model. | Multi-step mechanism: The decomposition does not follow a single reaction pathway. This is common in complex systems like IPN hydrogels [29] or polymer blends [34]. | Use model-free isoconversional methods (e.g., Friedman, OFW) that do not assume a single reaction model and can handle complex mechanisms [29] [28]. |

| Large errors in predicted service lifetime. | Inaccurate extrapolation: Using kinetic parameters obtained at high temperatures (from TGA) to predict long-term stability at much lower use temperatures can be invalid if the degradation mechanism changes [28] [30]. | Choose an extrapolation model (e.g., Arrhenius, Toop) that accounts for the reaction mechanism. Validate predictions with real-time ageing data at lower temperatures where possible [27] [30]. |

| Inconsistent Ea from different properties. | Property-dependent degradation: Different material properties (e.g., elongation at break, mass loss) degrade at different rates and may reflect different chemical processes [30]. | Acknowledge that Ea is often "apparent" and specific to the measured property. Use Ea for comparative studies rather than as an absolute fundamental value [30]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Metrics

Protocol 1: Determining Decomposition Temperature via TGA

This protocol outlines the standard procedure for determining the decomposition temperature of a polymeric material using Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA).

1. Principle The sample mass is monitored as it is heated under a controlled atmosphere. The decomposition temperature is identified from the resultant thermogram as the onset of significant mass loss, or the temperature at the maximum rate of mass loss (Tmax) from the derivative thermogravimetry (DTG) curve [29] [33].

2. Materials and Equipment

- TGA instrument (e.g., SETARAM Labsys Evo, NETZSCH TG 209 F1 Libra)

- Balance, accuracy ± 0.01 mg

- High-purity inert gas (Nitrogen or Argon), for purge and protective atmosphere

- Sample: Powder or small pieces (∼5-20 mg)

- Crucibles: Alumina or platinum

3. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Calibration: Calibrate the TGA instrument for temperature and weight using certified standards.

- Sample Preparation: Weigh 10.0 ± 0.5 mg of the sample into a clean, tared crucible [29]. For polymers, ensure the sample is representative and free of residual solvent.

- Baseline Measurement: Run a blank curve with an empty crucible under the same conditions to be used for the sample.

- Parameter Setting:

- Atmosphere: High-purity nitrogen flow (e.g., 50 mL/min) [34].

- Temperature Program: Heat from room temperature to a suitable end temperature (e.g., 800-1000°C) at a constant heating rate (e.g., 10 °C/min) [29]. Multiple heating rates (e.g., 5, 10, 15 °C/min) are required for kinetic analysis [27] [33].

- Data Acquisition: Run the experiment in triplicate to ensure reproducibility and allow for statistical analysis [29].

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the percentage mass loss versus temperature (TGA curve).

- Plot the derivative of the TGA curve (DTG curve).

- The onset decomposition temperature (Tonset) is determined by the intersection of the baseline and the tangent at the point of maximum slope on the TGA curve.

- The temperature at the peak of the DTG curve is reported as Tmax, the temperature of maximum degradation rate.

Protocol 2: Calculating Activation Energy Using Isoconversional Methods

This protocol describes the calculation of apparent activation energy using the model-free Ozawa-Flynn-Wall (OFW) method, which is ideal for analyzing complex decompositions [29] [28].

1. Principle The OFW method calculates the activation energy at progressive degrees of conversion (α) without assuming a reaction model. It uses the shift in temperature required to reach the same conversion level at different heating rates [28].

2. Prerequisites

- TGA data obtained at a minimum of three different heating rates (β), e.g., 5, 10, and 15 °C/min [27].

- Mass loss data converted to degree of conversion (α), where α = (m0 - mt) / (m0 - mf), with m0, mt, and mf being initial, current, and final mass, respectively.

3. Step-by-Step Calculation

- Data Extraction: For each heating rate, record the temperature (Tα) at fixed intervals of α (e.g., from α = 0.05 to 0.95 in steps of 0.05).

- OFW Plotting: For each value of α, plot log(β) versus 1000/Tα (with T in Kelvin).

- Activation Energy Calculation: For each α, the activation energy (Ea) is calculated from the slope (S) of the OFW plot:

- Interpretation: Plot Ea as a function of α. A constant Ea suggests a single mechanism. Variations in Ea indicate a multi-step process, as often seen in IPN hydrogels or polymer blends [29] [34].

Comparative Data for Polymer Systems

The following tables summarize key stability metrics for different classes of materials as reported in recent literature.

Table 1: Decomposition Temperatures and Activation Energies of Selected Polymers and Composites

| Material System | Decomposition Temperature (Td or Tmax) | Activation Energy (Ea, kJ/mol) | Method / Notes | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVA/PEGDA-PEGMA IPN Hydrogel | Varies with composition | Multi-step, Ea distribution by conversion | TGA, Friedman & OFW methods. Ea depends on PVA & crosslinker content. | [29] |

| Nifedipine (API) | Onset: ~150 °C (slow) | 115.5 ± 2.4 | TGA, sc-MKA method. Decomposition begins below melting point. | [26] |

| Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) | -- | 346.2 (at 5% conversion) | TGA, Flynn-Wall method. Used for lifetime prediction of wire insulation. | [27] |

| Polychlorotrifluoroethylene (PCTFE) | -- | 238.7 (at 5% conversion) | TGA, Flynn-Wall method. Compared with PTFE for insulation. | [27] |

| PMMA/NiO Nanocomposite | Decreases with NiO addition | Decreases with NiO | TGA, Kissinger method. Longer mixing time reduces stability. | [33] |

| Chalcogenide Glass (STSI) | -- | Multi-step | TGA, Isoconversional & model-fitting (Šesták–Berggren). | [31] |

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Thermal Stability Research

| Research Reagent | Function in Experiment | Example Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) | Chemical crosslinker to form a dense polymer network. | IPN hydrogels; increases crosslinking density, limiting moisture retention and altering thermal decomposition profile [29]. |

| Thermolatent Brønsted Base Generators (TBGs) | Catalysts that release active base upon thermal stimulus, triggering or controlling reactions. | Dynamic polymer networks (vitrimers); allows spatiotemporal control over bond exchange for recycling/repair [32]. |

| Lithium 2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (TPO-Li) | Photo-sensitizer / initiator for UV-induced polymerization. | Synthesis of PVA/PEGDA-PEGMA hydrogels; enables network formation under mild UV light exposure [29]. |

| Nickel Oxide (NiO) Nanoparticles | Inorganic nanofiller to modify thermal, mechanical, or electrical properties. | PMMA nanocomposites; can alter thermal degradation kinetics and stability depending on dispersion [33]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

- Core Analytical Instrument: Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA), often coupled with DTA/DSC or evolved gas analysis (FTIR/MS).

- Software for Kinetic Analysis: OriginPro, Python (NumPy, SciPy, Matplotlib) for data processing and applying complex kinetic models (e.g., Friedman, OFW, NPK) [29].

- Essential Labware: High-temperature crucibles (Alumina, Pt), automated gas flow systems, and precise microbalances.

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Thermal Stability Assessment

Diagram 2: Relationship Between Key Stability Metrics

For researchers and scientists engaged in the development of materials for extreme environments, the transition from commodity plastics to high-performance polyimides represents a critical pathway toward achieving unprecedented thermal stability. Polyimides stand at the apex of polymer technology, offering exceptional thermal, mechanical, and chemical properties that make them indispensable for advanced applications in aerospace, electronics, energy storage, and transportation [35]. These materials combine outstanding thermal stability exceeding 400°C, exceptional mechanical properties, inherent flame retardancy, and remarkable chemical resistance [35] [36]. This technical support center provides essential guidance for addressing key experimental challenges and advancing research in thermal stability polymers, with specific focus on methodologies, troubleshooting, and practical experimental protocols.

Essential Knowledge Base: Polyimide Fundamentals

FAQ: Core Properties and Characteristics

Q: What defines the upper thermal limit for polyimides in practical applications? A: While polyimides can withstand short-term exposure to temperatures as high as 555°C, their continuous service temperature typically falls between 250-333°C for long-term applications. The onset of thermal degradation generally begins above 400°C, with significant chemical structure changes occurring beyond this point [37] [36] [38].

Q: How does polyimide thermal performance compare to other high-temperature polymers like PEEK? A: Polyimides significantly surpass PEEK in thermal performance. While PEEK remains stable to approximately 260°C, various polyimide formulations can withstand temperatures exceeding 300-400°C. Polyimides also exhibit higher glass transition temperatures (often exceeding 250°C compared to 143°C for PEEK) [39] [40].

Q: What are the primary degradation products of polyimides under thermal stress? A: Thermo-oxidative degradation of polyimides produces gases including CO₂, CO, H₂O, NH₃, HCN, and various N-containing compounds such as aromatic amines, nitriles, and phthalimides. Under air atmosphere, NH₃ and HCN can further convert to NOx compounds [37] [41].

Q: What are the key processing challenges with polyimides? A: Polyimides present significant processing difficulties due to their high melting temperatures, high melt flow viscosity, and narrow processing windows. They cannot be injection molded and are typically limited to compression molding or extrusion [39]. Additive manufacturing approaches are emerging but require specialized techniques [35].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Inconsistent thermal stability measurements in TGA analysis

- Potential Cause: Sample history sensitivity (moisture absorption, previous thermal cycling)

- Solution: Implement standardized pre-drying protocols (120°C under vacuum for 24 hours) and control atmospheric conditions during testing [38] [42]

- Prevention: Store polyimide samples in moisture-free environments and document thermal history

Problem: Nanoparticle agglomeration in composite formulations

- Potential Cause: Poor compatibility between nanoparticles and polyimide matrix

- Solution: Employ surface modification of nanoparticles, optimize sonication parameters, and utilize compatibilizing agents [42]

- Prevention: Gradually add nanoparticles to the matrix and maintain constant stirring during processing

Problem: Degradation during additive manufacturing

- Potential Cause: Thermal management complexities and inadequate dimensional control

- Solution: Optimize printing parameters for specific PI formulation, implement controlled cooling cycles, and employ structural tuning to enhance printability while retaining thermal performance [35]

- Prevention: Characterize material-specific processing windows thoroughly before manufacturing

Problem: Variable dielectric properties under thermal ageing

- Potential Cause: Molecular mobility acceleration and changes in charge transport mechanisms

- Solution: Control thermal exposure history and implement pre-aging conditioning protocols [38]

- Prevention: Incorporate stabilization additives and maintain operating temperatures below accelerated mobility thresholds

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Thermal Analysis

Protocol 1: Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) for Thermal Stability Assessment

Purpose: To quantitatively determine the thermal decomposition profile and stability limits of polyimide materials [37] [41] [42].

Materials and Equipment:

- Thermogravimetric analyzer (TGA)

- High-purity nitrogen or air gas supply

- Sample pans (platinum or alumina)

- Microbalance

- Polyimide samples (5-15 mg)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Precisely weigh 5-15 mg of polyimide material using a microbalance. For films, cut to fit sample pan without overlapping.

- Instrument Calibration: Perform temperature calibration using magnetic standards (Nickel, Perkalloy) or melting point standards (Indium, Tin).

- Parameter Setup:

- Temperature range: 25°C to 1000°C

- Heating rates: 5°C, 10°C, 20°C, and 30°C/min for kinetic analysis

- Gas flow: 60 mL/min nitrogen or air

- Data collection: Continuous weight and derivative weight (DTG)

- Analysis Execution:

- Purge system with inert gas for 10 minutes before heating

- Initiate temperature program and record data continuously

- Perform triplicate runs for statistical significance

- Data Interpretation:

- Determine onset degradation temperature (T₅% - temperature at 5% weight loss)

- Identify maximum decomposition rate temperature from DTG peak

- Calculate residual char yield at 800°C

Kinetic Analysis:

- Apply multiple heating rate methods (FWO, KAS, Starink) for activation energy calculation [41]

- Use master-plot method to determine reaction model (typically F2 or F3 for polyimides) [41]

Protocol 2: Dynamic Mechanical Thermal Analysis (DMTA) for Relaxational Behavior

Purpose: To characterize molecular relaxations and mechanical property evolution under thermal stress [38].

Materials and Equipment:

- Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer (DMA)

- Polyimide film samples (rectangular: 32 × 12.5 mm²)

- Liquid nitrogen cooling system

- Temperature controller

Procedure:

- Sample Mounting: Clamp polyimide film in tension or dual cantilever geometry with precise torque control.

- Temperature Program:

- Range: -150°C to 400°C

- Heating rate: 2°C/min

- Frequency: 1 Hz (multi-frequency optional)

- Strain amplitude: 0.01% (within linear viscoelastic region)

- Data Collection: Monitor storage modulus (E'), loss modulus (E"), and tan delta continuously.

- Relaxation Identification:

- γ relaxation: ~-85°C (local mobility of polar groups with water molecules)

- β relaxation: ~200°C (molecular oscillation of p-phenylene groups)

- Ageing Studies: Compare relaxational behavior before and after thermal ageing at elevated temperatures.

Interpretation Guidelines:

- Accelerated molecular mobility evidenced by shifts in γ and β relaxations indicates thermal degradation progression [38]

- Changes in storage modulus slope reveal structural modifications

- Peak broadening in tan delta suggests increased heterogeneity

Protocol 3: Pyrolysis-GC/MS for Degradation Pathway Analysis

Purpose: To identify thermal decomposition products and elucidate degradation mechanisms [37] [41].

Materials and Equipment:

- Customized Pyrolysis-GC/MS system

- Pyrolysis tubes or cups

- High-purity helium carrier gas

- Polyimide samples (0.5-1 mg)

- GC capillary column (non-polar stationary phase)

- Mass spectrometer detector

Procedure:

- Sample Loading: Precisely weigh 0.5-1 mg polyimide into pyrolysis cup.

- Pyrolysis Parameters:

- Temperature: 500-900°C (programmed or single-shot)

- Interface temperature: 300°C

- Cryogenic trapping: -50°C (optional)

- GC Separation:

- Column: 30m × 0.25mm ID, 0.25μm film thickness

- Oven program: 40°C (2 min) to 300°C at 10°C/min

- Carrier gas: Helium at 1.0 mL/min constant flow

- MS Detection:

- Ionization: Electron impact (70 eV)

- Mass range: 35-650 m/z

- Scan rate: 2-5 scans/second

- Data Analysis:

- Identify major pyrolysis products (CO₂, CO, H₂O, N-containing compounds)

- Compare mass spectra with NIST library

- Track product evolution with temperature

Three-Stage Degradation Mechanism [41]:

- Stage 1: Initial bond cleavage around imide ring

- Stage 2: Major decomposition with gas evolution

- Stage 3: Char formation and secondary reactions

Comparative Data Analysis: Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Thermal Properties of High-Performance Polymers

| Material | Continuous Service Temperature (°C) | Glass Transition Temperature (°C) | Onset Degradation Temperature (°C) | Char Yield at 800°C (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyimide (Kapton) | 333 | >250 | 460-585 | 50-60 | [37] [36] [38] |

| Polyamide-imide (PAI) | 250-280 | 280-320 | 460-500 | 45-55 | [37] |

| Polyetherimide (PEI) | 170-200 | 210-220 | 460-480 | 40-50 | [37] |

| PEEK | 260 | 143 | 350-400 | 30-40 | [39] [40] |

| Nanoparticle Type | Loading (%) | Onset Degradation Temperature Change | Char Yield at 800°C | Glass Transition Temperature Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al₂O₃ | 3-9 | Increase (5-15°C) | Increase (3-8%) | Increase (5-12°C) |

| ZnO | 3-9 | Decrease (5-10°C) | Decrease (2-5%) | Increase (3-8°C) |

| None (Control) | 0 | 400°C (baseline) | 55% (baseline) | 250°C (baseline) |

| Kinetic Method | Activation Energy (kJ/mol) | Correlation Coefficient (R²) | Best-Fit Reaction Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flynn-Wall-Ozawa (FWO) | 284.6 | >0.98 | F2, F3 |

| Kissinger-Akahira-Sunose (KAS) | 286.1 | >0.98 | F2, F3 |

| Starink | 286.5 | >0.98 | F2, F3 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Polyimide Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes | Supplier Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| BTDA (3,3',4,4'-Benzophenonetetracarboxylic dianhydride) | Monomer for polyimide synthesis | Forms rigid backbone structure; handle under anhydrous conditions | Sigma-Aldrich |

| PMDA (Pyromellitic dianhydride) | Monomer for polyimide synthesis | Creates high-Tg polymers; moisture sensitive | Alfa Aesar |

| ODA (4,4'-Oxydianiline) | Diamine monomer | Provides ether linkages for processability | TCI Chemicals |

| Al₂O₃ Nanoparticles (20-50nm) | Thermal stability enhancement | Improves thermal conductivity; optimize dispersion | Nanophase Technologies |

| ZnO Nanoparticles (30-70nm) | UV shielding functionality | May reduce thermal resistance; provides semiconductor properties | Alfa Aesar |

| NMP (N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone) | Solvent for polyimide precursor | High boiling point (202°C); handle in dry atmosphere | VWR Canada |

| DMAc (N,N-Dimethylacetamide) | Synthesis solvent | For poly(amic acid) precursor formation | Sigma-Aldrich |

Advanced Applications: Polyimides in Emerging Technologies

Energy Storage Systems

Polyimides serve as critical "inert" components in lithium-ion batteries, including separators, solid-state electrolytes, protective layers, and binders. Their exceptional thermal stability addresses safety concerns in high-energy-density batteries, while their mechanical robustness maintains electrode integrity during cycling [36].

Additive Manufacturing

Novel AM techniques for polyimides include vat photopolymerization, direct ink writing (DIW), and material extrusion. Structural tuning approaches enhance printability while retaining thermal performance, enabling complex geometries unattainable through traditional processing [35].

Future Research Directions: Advancing Thermal Stability Frontiers

The future of polyimide research focuses on multifunctional composites, stimuli-responsive materials, and advanced manufacturing approaches [35]. Key challenges include cost-effective synthesis, balancing electrical and mechanical properties, and optimizing interfaces through molecular engineering [36]. Emerging opportunities exist in smart polyimide composites that respond to environmental stimuli while maintaining thermal stability under extreme conditions.

Research should prioritize sustainable manufacturing approaches and recycling methodologies, particularly pyrolysis-based recovery of valuable N-containing materials from polyimide waste [37] [41]. The integration of computational materials design with experimental validation will accelerate development of next-generation polyimides with customized thermal performance profiles for specific application environments.

Material Design and Stabilization Strategies for Enhanced Thermal Performance

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is incorporating aromatic and heterocyclic structures into a polymer backbone a common strategy to improve thermal stability?

Integrating aromatic and heterocyclic structures into polymer backbones is a fundamental strategy in developing high-performance materials. These rigid, cyclic structures impart significant advantages over aliphatic polymers, primarily due to their high resonance stability and strong intermolecular interactions. This results in greater thermal and oxidative stability, higher strength, lower flammability, and improved solvent resistance, making them suitable for demanding engineering applications [43]. The general structure of such polymers is often denoted as -Ar1-X-Ar2-Y-, where 'Ar' represents aromatic moieties and 'X' and 'Y' are bridging units [43].

Q2: What are some common examples of high-performance aromatic polymers and their applications?

Common families of aromatic polymers include poly(arylene ether)s, polyetherketones, polysulfones, and polysulfides [43]. These materials are used as high-performance engineering plastics in industries such as aerospace, electronics, and automotive. For instance, polysulfones (PSU) are widely used as base materials for membrane-mediated separation processes like water purification, gas separation, and fuel cells due to their excellent mechanical properties and chemical inertness [43].

Q3: What is a key challenge when working with fully aromatic homopolyanhydrides, and how can it be addressed?

A key challenge with fully aromatic homopolyanhydrides is their poor processability; they are often insoluble in common organic solvents and melt at temperatures above 200°C [43]. This limits their fabrication into films or microspheres. A common strategy to address this is copolymerization with other aromatic diacids, such as isophthalic acid (IPA) or terephthalic acid (TA), which can yield polymers that are soluble in chlorinated hydrocarbons and melt at temperatures below 100°C, thus improving processability while maintaining a slow degradation profile [43].

Q4: My phthalonitrile-benzoxazine resin has a complex curing process. How does the backbone structure influence its curing behavior?

The backbone structure of a phthalonitrile-containing benzoxazine resin significantly impacts its curing kinetics. The steric hindrance derived from the backbone structure can notably change the activation energies for the reactions of both the benzoxazine and the nitrile groups [44]. For example, a resin with a fluorene structure in its backbone will exhibit different curing behavior and final properties compared to one without it. The curing process is typically a two-stage reaction involving the ring-opening polymerization of the benzoxazine ring followed by the ring-forming polymerization of the nitrile groups, and the efficiency of the first stage directly affects the second [44].

Troubleshooting Guides

Curing and Processability Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Curing Temperature | High steric hindrance from rigid aromatic backbone; Lack of efficient catalyst/initiator. | Utilize a self-catalytic system like benzoxazine-containing phthalonitrile (BA-ph) where the ring-opening generates catalytic sites [44]. |

| Insufficient Thermal Stability in Final Polymer | Incomplete crosslinking of nitrile groups; Low degree of polymerization. | Ensure a complete two-stage curing process: first, ring-opening of benzoxazine, then triazine formation from nitriles. Use thermal analysis (TGA/DSC) to optimize cure cycle [44]. |

| Poor Solubility or High Melting Point | High crystallinity from linear, symmetric aromatic structures. | Design copolymers with less symmetric monomers (e.g., incorporate meta-linked aromatics or bulky groups like fluorene) to disrupt chain packing [43] [44]. |

| Uncontrolled Polymerization Rate | Improper initiator choice or thermal management. | For solution polymerization, use cooling to control exothermic reactions. For condensation polymerization, use heat and vacuum to remove by-products [45]. |

Characterization and Property Analysis

| Problem | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unexpectedly Low Activation Energy (Eα) | Autocatalytic behavior from generated phenolic groups during benzoxazine ring-opening. | Confirm the reaction model using DSC kinetics analysis. An autocatalytic model is typical for these systems [44]. |

| Poor Mechanical Properties (e.g., brittleness) | High crosslink density; Presence of structural defects or incomplete curing. | Use DSC to confirm full conversion. Characterize fracture surfaces with SEM to identify failure origins. Adjust backbone flexibility [44]. |

| Inconsistent Results Between Batches | Variations in monomer purity, stoichiometry, or curing conditions. | Strictly control synthesis and purification of monomers. Use calibrated equipment and maintain consistent, monitored curing profiles (time/temperature) [44] [46]. |

Curing Kinetics of Phthalonitrile-Benzoxazine Resins

The following table summarizes kinetic parameters for different phthalonitrile-based resins, illustrating how the backbone structure affects the curing process. The activation energy (Eα) was evaluated using non-isothermal DSC [44].

| Resin Type | Backbone Structure Feature | Curing Stage | Apparent Activation Energy, Eα (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BA-ph | Standard Aromatic Backbone | Benzoxazine Ring-Opening | Value Not Explicitly Given in Source |

| BA-ph | Standard Aromatic Backbone | Nitrile Cyclotrimerization | Value Not Explicitly Given in Source |

| WZ-cn | Contains Bulky Fluorene Group | Benzoxazine Ring-Opening | Significantly Changed due to steric hindrance [44] |

| WZ-cn | Contains Bulky Fluorene Group | Nitrile Cyclotrimerization | Significantly Changed due to steric hindrance [44] |

Thermal Stability of Cured Polymers

Thermal stability of the cured polymers, as evaluated by Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA), is directly influenced by the backbone structure and the completeness of the curing reaction [44].

| Polymer System | Backbone Structure | Curing Condition | Key Thermal Stability Metric (e.g., Td₅%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cured BA-ph | Standard Aromatic | Optimized two-stage cure | Outstanding thermal stability confirmed [44] |

| Cured WZ-cn | Contains Fluorene | Optimized two-stage cure | Outstanding thermal stability confirmed [44] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Synthesis of a Fluorene-Based Benzoxazine Monomer (WZ-cn)

This protocol outlines the synthesis of a high-performance benzoxazine monomer with a fluorene group in the backbone, adapted from recent research [44].

- Objective: To synthesize a phthalonitrile-functionalized benzoxazine monomer (WZ-cn) with a fluorene backbone for enhanced thermal properties.

- Principle: A Mannich condensation reaction between a fluorene-based phenol derivative, an aromatic diamine with a phthalonitrile group, and formaldehyde.

- Materials:

- Fluorene-based phenol compound

- 4-(4-Aminophenoxy)phthalonitrile (or similar nitrile-functionalized amine)

- Paraformaldehyde

- Anhydrous toluene or 1,4-dioxane as solvent

- Procedure:

- Charge the fluorene-based phenol and the nitrile-functionalized amine into a round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer and reflux condenser.

- Add anhydrous toluene to the flask and stir to dissolve the reactants.

- Add paraformaldehyde to the reaction mixture in a stoichiometric ratio (typically 2:1:4 for phenol:amine:formaldehyde).

- Heat the reaction mixture to reflux (e.g., 110-120°C for toluene) with continuous stirring under an inert atmosphere (N₂ or Ar) for 12-24 hours.

- Allow the mixture to cool to room temperature after the reaction time.

- Precipitate the crude product by pouring the reaction mixture into a large excess of vigorously stirred hexane or petroleum ether.

- Collect the solid product via filtration and wash several times with the non-solvent.

- Purify the product by recrystallization from a suitable solvent (e.g., ethanol/toluene mixture) to obtain the pure WZ-cn monomer as a fine powder.

- Characterization:

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (¹H-NMR): Confirm the structure by identifying characteristic peaks: aromatic protons (6.69–7.79 ppm), and the distinct methylene protons of the oxazine ring at 4.48 ppm (N–CH₂–Ar) and 5.29 ppm (O–CH₂–N) [44].

- Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR): Verify key functional groups: the nitrile stretch at ~2230 cm⁻¹, and the C-O-C and C-N-C stretches of the oxazine ring at 1243, 1002, 1169, and 824 cm⁻¹ [44].

Protocol: Non-Isothermal DSC Analysis for Curing Kinetics

This method is used to determine the kinetic parameters of the polymerization process, which is crucial for optimizing the cure cycle [44].

- Objective: To study the curing behavior and determine the activation energy (Eα) of the benzoxazine ring-opening and nitrile group polymerization reactions.

- Materials:

- Purified benzoxazine monomer (e.g., BA-ph or WZ-cn)

- Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC)

- Standard aluminum DSC pans and lids

- Procedure:

- Precisely weigh 5-10 mg of the monomer into an aluminum DSC pan and seal it hermetically. An empty pan is used as a reference.

- Place the sample in the DSC and program the following method: heat from room temperature to 400°C at multiple, different linear heating rates (e.g., 5, 10, 15, and 20 °C/min) under a continuous nitrogen purge.

- For each heating rate, record the DSC thermogram, which will typically show two exothermic peaks corresponding to the ring-opening of benzoxazine and the cyclotrimerization of nitrile groups.

- Data Analysis:

- For each exothermic peak, determine the extrapolated onset temperature (Tᵢ) and peak temperature (Tₚ) at each heating rate (β).

- Use multiple model-free methods (e.g., Kissinger, Ozawa) for calculating the apparent activation energy (Eα) for each reaction stage.

- An autocatalytic model is typically confirmed for these reactions. The change in Eα due to different backbone structures (like the fluorene in WZ-cn) should be analyzed and compared [44].

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Aromatic Polymer Synthesis Workflow

Curing Behavior Relationship

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Polymer Backbone Engineering |

|---|---|

| Phthalonitrile-containing Monomers | Key building blocks that introduce nitrile (-C≡N) functional groups, which undergo thermally-induced cyclotrimerization to form triazine rings, creating a highly cross-linked and thermally stable network [44]. |

| Benzoxazine Monomers | Serve as a source of aromatic rings and provide a self-catalytic mechanism for polymerization; upon ring-opening, they generate phenolic Mannich structures that catalyze the cure of other functional groups like nitriles [44]. |

| Fluorene-based Comonomers | Incorporate rigid, bulky aromatic structures into the polymer backbone. This enhances thermal stability and glass transition temperature (Tg) while influencing curing kinetics and mechanical properties through steric effects [44]. |

| Catalysts (e.g., for condensation polymerization) | Drive step-growth (condensation) polymerizations forward, often by facilitating the removal of small molecule by-products like water or methanol. Essential for achieving high molecular weight [45]. |

| Initiators (e.g., Peroxides, Redox systems) | Generate active species (free radicals, cations, anions) to initiate chain-growth polymerization in methods like solution or emulsion polymerization [45]. |

Within the broader research on improving the thermal stability of polymers, additive stabilization systems are fundamental for enabling the processing and extending the service life of polymeric materials. Polymers are susceptible to degradation from environmental factors such as heat, oxygen, and UV light, leading to chain scission, cross-linking, loss of mechanical properties, and discoloration [47] [48]. Stabilization techniques are crucial for mitigating these degradation pathways. These methods protect polymers from oxidation, UV radiation, and thermal degradation, ensuring they maintain their properties under various conditions [47]. The core stabilization systems discussed in this guide—antioxidants, radical scavengers, and hydroperoxide decomposers—function by interfering with the auto-oxidation cycle at different stages, thereby kinetically retarding natural decay [49].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Stabilization Issues and Solutions

Problem: Inconsistent Thermal Stability Despite Identical Formulation Symptom: Variations in early yellowing or discoloration between production batches when using the same stabilizer package [50]. Root Cause & Analysis: The issue often lies not in the stabilizer chemistry itself, but in its dispersion and distribution within the polymer matrix. Inadequate shear during mixing can lead to stabilizer agglomerates or "fisheyes," creating local hotspots with insufficient protection. Conversely, excessive shear can cause mechanical degradation of the polymer, consuming the stabilizer prematurely [50]. Solution:

- Optimize Mixing Parameters: Ensure consistent mixer speed, time, and fill level across all batches. Monitor the temperature profile to achieve a "sweet spot" that ensures uniform coating of PVC particles without overheating [50].

- Verify Equipment: Check for worn mixer blades or dead spots that could lead to under-mixed material [50].

- Review Addition Sequence: Follow the recommended feeding order; for example, adding the stabilizer at around 60°C can maximize its contact with the resin as it begins to soften [50].

Problem: Unexpected Loss of Thermal Stability or Excessive Fumes Symptom: A stabilized formulation shows premature degradation, HCl emission, or plate-out in vents and molds [50]. Root Cause & Analysis: This is frequently caused by volatilization and loss of stabilizer components. Overly aggressive processing temperatures (during both mixing and extrusion) can drive off volatile stabilizer components, such as certain organic co-stabilizers, reducing the effective concentration in the polymer [50] [51]. Solution:

- Review Thermal History: Check if mixer or extruder zones have overshot intended temperatures. A strong odor or fumes at the extruder vent indicates volatility issues [50].

- Adjust Processing Conditions: Lower barrel temperatures and ensure adequate venting vacuum in the extruder [50].