Solving Polymer Chain Degradation: Mechanisms, Analysis, and Stabilization Strategies for Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals tackling polymer chain degradation.

Solving Polymer Chain Degradation: Mechanisms, Analysis, and Stabilization Strategies for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals tackling polymer chain degradation. It covers fundamental degradation mechanisms—thermal, oxidative, hydrolytic, and enzymatic—and explores advanced analytical techniques like SEC, TGA, and FTIR for characterization. The content details practical methodologies for lifetime prediction and stabilization, presents troubleshooting strategies for processing and in-service failure, and outlines validation frameworks for comparing material performance. By synthesizing foundational science with applied problem-solving, this resource aims to enhance the durability, reliability, and efficacy of polymeric materials in biomedical products and therapies.

Understanding Polymer Degradation: Core Mechanisms and Chemical Pathways

FAQs: Core Concepts and Mechanisms

Q1: What are the primary modes of polymer chain scission, and what determines which one occurs? The two fundamental modes are chain-end scission and random scission [1]. The dominant mode is not purely random nor dictated solely by molecular chemistry; the most critical determining factor is the polymer's solubility [1] [2]. Soluble polymers predominantly undergo chain-end scission, where monomers are sequentially cleaved from the chain ends. In contrast, insoluble polymers (such as many plastics in aqueous environments) tend to fragment via random scission, where chains break at arbitrary points along their backbone [1]. This finding overturns the common assumption that molecular structure or bond type alone governs the degradation pathway.

Q2: What are the common degradation mechanisms encountered during polymer processing? During processing like extrusion or injection molding, polymers are subjected to high temperatures and shear, leading to several key mechanisms [3]:

- Thermal Degradation: Chain breakage due to heat, governed by bond dissociation energies.

- Thermo-mechanical Degradation: The combined effect of heat and mechanical shear stress breaking chains.

- Thermo-oxidative Degradation: Chain breakage initiated by heat in the presence of even small amounts of oxygen.

- Hydrolysis: Cleavage of polymer chains (especially in polyesters) by water and heat.

Q3: Why does polymer degradation lead to a loss of mechanical properties? Degradation induces irreversible changes at the molecular scale, such as a reduction in chain length (molecular weight), changes in dispersity, and the introduction of new functional groups [3]. These molecular-level alterations directly impact macroscopic properties. For instance, photo-oxidative degradation from UV exposure creates a hardened, brittle surface layer [4]. This degraded layer acts as a crack initiator, significantly reducing the material's overall fracture toughness and leading to failure [4].

Q4: What biological methods are available for polymer waste management? Biodegradation, which uses microorganisms and their enzymes to break down polymers, is a sustainable alternative to landfill and incineration [5]. Strategies include:

- Single-Strain Degradation: Using a specific, effective bacterial strain.

- Multi-Strain Communities: Employing consortia of microbes that are often more resilient and efficient.

- Enzyme Engineering: Using directed evolution or rational design to enhance the catalytic efficiency of degradation enzymes [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Unexpected Material Embrittlement

Problem: A transparent polymer part becomes brittle and develops surface micro-cracks after outdoor use or accelerated weathering.

Investigation & Solution:

| Step | Action | Underlying Principle & Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Confirm | Perform visual inspection for yellowing and surface cracking; use Indentation testing to measure surface hardening. | UV exposure causes photo-oxidative degradation, forming a hardened, brittle surface layer that acts as a stress concentrator [4]. |

| 2. Analyze | Use Micro-FTIR to determine the degradation depth profile and identify oxidation products. | FTIR analysis can quantitatively measure the distribution of photoproducts (like carbonyl groups) with high-depth resolution from the surface inward [4]. |

| 3. Resolve | Reformulate with UV stabilizers (e.g., UV absorbers, HALS); consider a protective coating. | Stabilizers are additives that reduce the degradation rate by protecting polymer chains against radical attacks initiated by UV radiation [3]. |

Guide 2: Controlling Degradation During Melt Processing

Problem: During extrusion or injection molding, a polymer shows severe molecular weight loss and discoloration.

Investigation & Solution:

| Step | Action | Underlying Principle & Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Confirm | Check moisture content of resin pellets prior to processing; analyze Mw post-processing via GPC. | Moisture and high temperature cause hydrolysis, leading to random chain scission and a rapid drop in Mw [3]. Thermal-oxidative degradation also causes chain breakage and discoloration [3]. |

| 2. Analyze | Review processing parameters: temperature profile, screw speed, and presence of venting. | Excessive temperatures and shear rates provide energy for thermal and thermo-mechanical degradation. Trapped air introduces oxygen for oxidation [3]. |

| 3. Resolve | Pre-dry the polymer resin thoroughly; optimize processing temperature and shear; introduce appropriate stabilizers (antioxidants). | Drying prevents hydrolysis. Optimizing parameters minimizes excessive thermal/mechanical energy. Stabilizers (antioxidants) interrupt the radical chain reactions of oxidation [3]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Characterizing a Surface-Degraded Layer via Indentation Testing

Objective: To quantitatively measure the thickness and mechanical properties of a hardened surface layer on a polymer sample resulting from UV degradation [4].

Materials & Reagents:

- Weathered polymer sample (e.g., polycarbonate exposed to UV).

- Nanoindentation tester with a sharp tip (e.g., Berkovich, Vickers).

- Reference sample (non-degraded, from the same batch).

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Mount the degraded polymer sample to ensure the surface is flat and accessible.

- Shallow Indentation: Perform indentation at multiple locations on the surface at a very shallow depth (e.g., 1-2 µm). This step is designed to characterize the properties of the degraded layer itself, ignoring the effect of the underlying non-degraded substrate [4].

- Deep Indentation: Perform deeper indentations (e.g., 10-50 µm) at various locations. The indentation curve here will be affected by the combined response of the degraded layer and the substrate [4].

- Reverse Analysis: Use the shallow indentation data to deduce the elastoplastic properties (Young's modulus, yield strength) of the degraded layer. Then, use the deep indentation data and a pre-established dimensionless function in a Finite Element Method (FEM) model to calculate the thickness of the degraded layer [4].

Protocol 2: Identifying Chain Scission Mode via Kinetic Modeling

Objective: To determine whether a polymer degrades primarily via chain-end or random scission by analyzing time-dependent molecular weight data [1].

Materials & Reagents:

- Polymer samples degraded under controlled conditions for different time periods.

- Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) system for molecular weight analysis.

Methodology:

- Data Collection: Subject polymer samples to degradation (e.g., hydrolytic, enzymatic) and collect samples at regular time intervals. Use GPC to measure the molecular weight distribution for each time point [1].

- Model Fitting: Fit the time-dependent molecular weight data to two established kinetic models: one for chain-end scission and one for random scission [1].

- Statistical Analysis: Perform statistical analysis to identify which model provides the best fit for the experimental data. The model with the highest correlation indicates the dominant scission mode [1].

- Correlation with Solubility: Correlate the identified scission mode with the physical state (soluble or insoluble) of the polymer in the degradation medium, as solubility is the key predictive factor [1] [2].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Polymer Degradation Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Key Initiating Factor(s) | Primary Molecular Consequence | Resulting Property Changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal | High Temperature [3] | Random chain fission or end-chain β-scission [3] | Decrease in Mw, loss of viscosity & mechanical strength [3] |

| Thermo-oxidative | Heat + Oxygen [3] | Radical formation leading to chain scission & crosslinking [3] | Embrittlement, discoloration, surface cracking [4] [3] |

| Hydrolytic | Water/Moisture + Heat [3] | Random cleavage of hydrolysable bonds (e.g., esters) [3] | Rapid reduction in Mw, loss of mechanical integrity [3] |

| Photo-oxidative | UV Light + Oxygen [3] | Radical formation & chain scission in a surface layer [4] | Surface hardening, yellowing, loss of transparency [4] |

| Biodegradation | Microorganisms & Enzymes [5] | Enzymatic cleavage of polymer chains | Weight loss, reduction to small molecules/CO₂/H₂O [5] |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Polymer Degradation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| TBD (1,5,7-triazabicyclo[4.4.0]dec-5-ene) | Organic catalyst for degradation/chemical recycling of polyesters & polycarbonates [6] | Superbase; operates via dual H-bond activation of carbonyl and hydroxyl groups [6] |

| DBU (1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene) | Potent organocatalyst for glycolysis of polymers like PET [6] | Strong base; highly efficient in glycolytic degradation [6] |

| R. pyridinivorans F5 (Bacterial Strain) | Biodegradation of natural rubber [5] | Achieved 18% rubber weight reduction in 30 days [5] |

| Steroidobacter cummioxidans 35Y | High-efficiency biodegradation of natural rubber [5] | Gram-negative strain; 60% NR weight loss in 7 days [5] |

| UV Stabilizers (HALS, UV Absorbers) | Additives to prevent photo-oxidative degradation [3] | Inhibit radical chain reactions during UV exposure [3] |

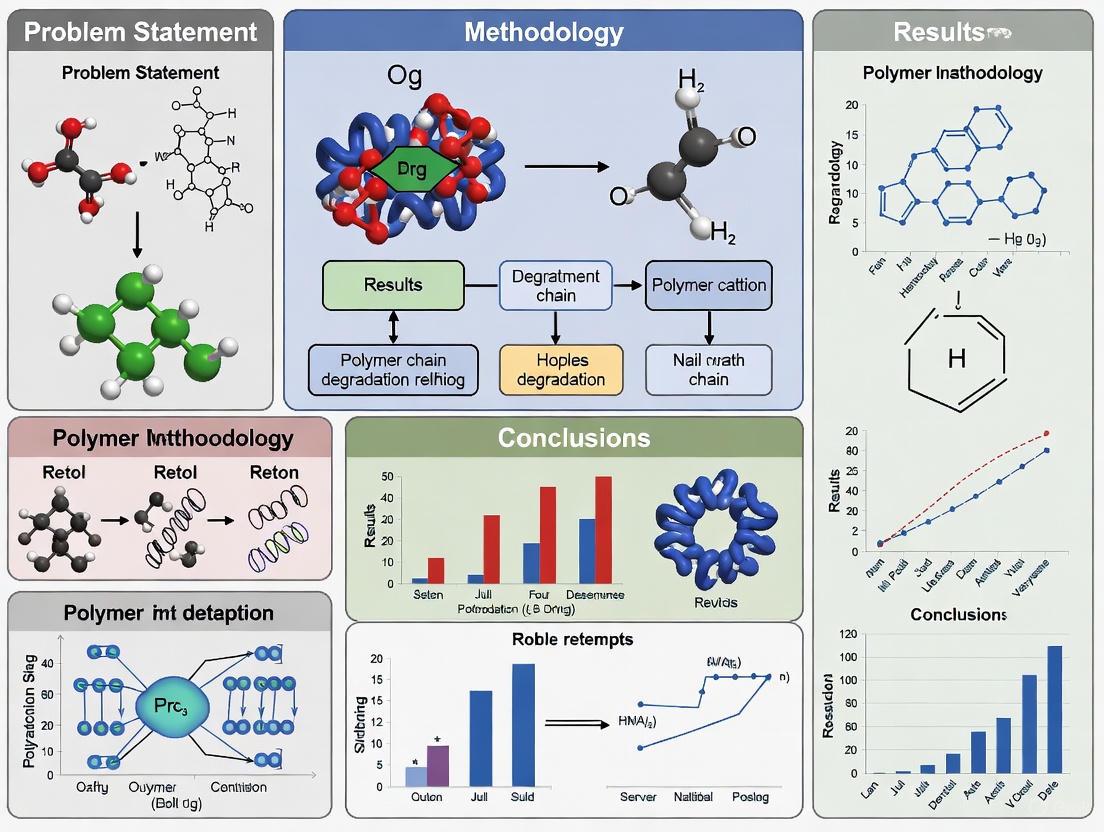

Mandatory Visualization

Degradation Pathways

Experimental Workflow

In the quest to develop advanced polymeric materials with enhanced longevity and performance, understanding their degradation under heat and oxygen is paramount. Thermal and thermo-oxidative degradation are fundamental processes that dictate the maximum service temperature, long-term stability, and ultimate failure of polymers. While thermal degradation involves molecular deterioration at elevated temperatures in an inert atmosphere, thermo-oxidative degradation occurs when oxygen is present, typically at lower temperatures and with different mechanistic pathways [7] [8]. For researchers and scientists, particularly in drug development where polymer-based delivery systems and devices are critical, controlling these degradation processes is essential to prevent premature material failure, ensure product safety, and predict shelf-life accurately. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and methodological support for investigating these complex phenomena within the broader research context of solving polymer chain degradation issues.

Fundamental Mechanisms: FAQs for Researchers

What is the fundamental chemical difference between thermal and thermo-oxidative degradation?

Thermal degradation is defined as a type of polymer degradation where damaging chemical changes take place at elevated temperatures without the involvement of oxygen. In contrast, thermo-oxidative degradation is accelerated by the presence of oxidants, leading to a lower onset decomposition temperature and different reaction mechanisms [7] [8]. The absence or presence of oxygen fundamentally alters the dominant chemical pathways and degradation products.

Why does my polymer sample show significant degradation at temperatures far below its melting point?

Many polymers are susceptible to thermo-oxidative degradation, which can become significant at temperatures much lower than those at which pure thermal degradation or mechanical failure occurs [8]. For example, the presence of tertiary carbon atoms in polypropylene makes it particularly sensitive to oxidative attack, initiating chain scission well below its melting temperature [9].

What are the common visual indicators of thermal and thermo-oxidative degradation during experiments?

Researchers should monitor for these common physical indicators:

- Discoloration (yellowing or darkening)

- Surface chalkiness or loss of gloss

- Formation of micro-cracks

- Em brittlement and reduced ductility

- Changes in melt viscosity [7] [10]

These physical changes are often manifestations of underlying chemical modifications like chain scission or cross-linking.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent Degradation Rates Between Batch Tests

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Oxygen concentration variability | Verify atmosphere control in ovens; use oxygen sensors | Use controlled atmosphere chambers; purge with inert gas |

| Sample thickness variations | Measure sample dimensions precisely; note surface-to-volume ratio | Use standardized sample geometry; consider diffusion-limited oxidation |

| Trace metal contaminants | Perform elemental analysis; test with/without chelating agents | Use polymer-grade materials; add metal deactivators |

| Residual catalyst presence | Analyze catalyst residue from synthesis | Implement purification steps; adjust polymerization conditions |

Problem: Unexpected Volatile Byproducts During Thermal Analysis

| Observed Byproduct | Likely Source Polymer | Degradation Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen chloride (HCl) | Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) | Side-group elimination at 100-120°C [7] |

| Styrene monomer | Polystyrene (PS) | Depolymerization via chain-end scission [11] |

| Alkanes, alkenes, ketones | Polyethylene (PE) | Random chain scission and β-scission [11] [9] |

| Terephthalic acid, ethylene glycol | Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) | Hydrolysis of ester bonds [11] |

Essential Analytical Methods & Protocols

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) for Degradation Kinetics

Protocol:

- Precisely weigh 5-15 mg of sample in a platinum or alumina crucible

- Select temperature program: typically 10°C/min from ambient to 800°C

- Choose atmosphere: inert N₂ for thermal degradation; air or O₂ for thermo-oxidative

- Record mass loss as a function of temperature

- Analyze derivative curve (DTG) to identify distinct degradation steps

Data Interpretation:

- Onset temperature: Indicator of initial stability

- Inflection points: Reveal multi-stage degradation processes

- Char residue: Provides information on thermal stability and cross-linking [7]

Determination of Oxidation Induction Time (OIT) via DSC

Protocol:

- Load 3-8 mg sample in hermetic aluminum pans with pinhole lids

- Heat rapidly (20°C/min) under nitrogen to specified isothermal temperature (e.g., 200°C)

- Hold for 1 minute to equilibrate

- Switch gas to oxygen at same flow rate (50 mL/min)

- Record time from gas switch to onset of exothermic oxidation peak

Application: OIT provides a quantitative measure of polymer stability and effectiveness of antioxidant packages, with longer times indicating better oxidative resistance [9].

FTIR Spectroscopy for Detecting Oxidation Products

Protocol:

- Prepare thin polymer films (50-100 μm) by compression molding

- Collect baseline spectrum before thermal exposure

- Age samples at controlled temperatures with/without oxygen

- Monitor specific absorbance peaks over time:

- Carbonyl region (1700-1750 cm⁻¹): Formation of ketones, aldehydes, carboxylic acids

- Hydroxyl region (3200-3600 cm⁻¹): Hydroperoxide and alcohol formation

- Calculate Carbonyl Index = Absorbance₍C=O₎ / Absorbance₍reference₎ [9]

Research Reagent Solutions for Degradation Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Antioxidants | Hindered phenols (BHT, Irganox 1010) | Radical scavengers; donate labile H atoms to terminate propagation [9] |

| Secondary Antioxidants | Phosphites (Irgafos 168), Thioesters | Hydroperoxide decomposers; prevent radical formation from hydroperoxides [9] |

| Hindered Amine Stabilizers | HALS (Tinuvin 770, Chimassorb 944) | Radical scavengers; regenerate active form; particularly effective against photo-oxidation [9] |

| UV Absorbers | Benzophenones, Benzotriazoles | Absorb harmful UV radiation; dissipate energy as heat [9] |

| Metal Deactivators | Irganox MD-1024 | Chelate transition metals; prevent catalytic decomposition of hydroperoxides [9] |

Experimental Workflow for Degradation Mechanism Elucidation

The following diagram illustrates a systematic approach to investigating polymer degradation mechanisms:

Systematic Workflow for Polymer Degradation Analysis

Characteristic Degradation Temperatures and Products

| Polymer | Thermal Degradation Onset (°C) | Main Degradation Mechanism | Primary Volatile Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene (PE) | ~400°C | Random chain scission | Alkanes, alkenes, carbonyl compounds [11] |

| Polypropylene (PP) | ~300°C | Random chain scission | Hydrocarbons, ketones, aldehydes [11] |

| Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) | 100-120°C (HCl loss) | Side-group elimination | Hydrogen chloride, aromatic compounds [7] [11] |

| Polystyrene (PS) | ~350°C | Depolymerization | Styrene monomer, oligomers [11] |

| Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) | ~300°C | Hydrolysis, scission | Terephthalic acid, ethylene glycol [11] |

| Polycarbonate (PC) | ~400°C | Hydrolysis, rearrangement | Bisphenol A, phenolic compounds [11] |

Advanced Research Considerations

Nanoparticle-Enhanced Stabilization

Emerging research demonstrates that nanoparticles can significantly enhance thermal stability through polymer-filler interactions. Nanoparticles with high surface area can form hydrogen or covalent bonds with polymer chains, increasing adhesion and dispersion degree, which typically leads to radical enhancement of chemical stability properties [8]. This approach is particularly promising for developing high-temperature polymer composites for demanding applications.

Organocatalysis for Controlled Degradation

Recent advances in organic catalysis have enabled more controlled degradation of condensation polymers. Catalysts like 1,5,7-triazabicyclo[4.4.0]dec-5-ene (TBD) exhibit exceptional efficiency in degrading polymers such as PET through a dual hydrogen-bonding activation mechanism [6]. This approach offers metal-free, environmentally friendly pathways for chemical recycling and upcycling of polymer waste, aligning with circular economy principles in polymer design.

Understanding thermal and thermo-oxidative degradation mechanisms provides the foundation for designing more stable polymeric materials and developing effective stabilization strategies. By implementing these troubleshooting guides, experimental protocols, and analytical methodologies, researchers can systematically address polymer chain degradation challenges across diverse applications from drug delivery systems to high-performance materials.

Key Mechanisms of Hydrolytic Degradation

Hydrolytic degradation is a chemical process in which water molecules cleave the backbone chains of a polymer. This is primarily a nucleophilic substitution reaction where water molecules act as nucleophiles, attacking electrophilic centers in the polymer chain [12] [13]. The mechanism varies based on the chemical structure of the polymer:

- Nucleophilic Substitution (SN1 and SN2): Water molecules attack susceptible bonds. The specific mechanism (SN1 or SN2) depends on the polymer's structure and reaction conditions, leading to bond cleavage and the formation of new functional groups like hydroxyl and carboxyl groups [13].

- Ester Bond Hydrolysis: This is common in polyesters like PET and PLA. A water molecule attacks the carbonyl carbon in the ester linkage, cleaving it and producing a carboxylic acid and an alcohol end group. This reaction can be catalyzed by acids or bases [12] [13].

- Chain Scission: The hydrolysis reaction severs the polymer's main chains. This can occur via random scission (breaking at random points along the backbone) or end scission (occurring at the chain ends). The immediate consequence is a reduction in the polymer's molecular weight, leading to a loss of mechanical properties [12] [13].

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for studying these mechanisms in an experimental setting.

Factors Influencing Degradation Rate

The rate of hydrolytic degradation is not constant; it is controlled by several chemical and physical factors [12] [13]:

- pH: Acidic or basic conditions act as catalysts, significantly accelerating the hydrolysis of bonds like esters and amides. The effect is most pronounced at extreme pH values [13].

- Temperature: Higher temperatures increase the kinetic energy of molecules, speeding up the reaction rate. This relationship follows the Arrhenius equation [13].

- Polymer Morphology: The physical structure of a polymer is a major determinant of degradation rate. Crystalline regions are more resistant to water penetration than amorphous regions. Similarly, polymers with hydrophobic segments degrade slower than hydrophilic ones [12].

- Presence of Catalysts/Additives: Metal ions (e.g., zinc, iron) can catalyze hydrolysis. Conversely, stabilizers can be added to inhibit the degradation process [14] [13].

Table 1: Susceptibility of Common Functional Groups to Hydrolysis

| Functional Group | Polymer Example | Relative Susceptibility | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aliphatic Ester | PLA, PGA, PET | Very High | High pH, temperature, catalyst presence [14] [15] |

| Aromatic Ester | Polyarylate | Moderate | Electron-withdrawing groups, high pH [15] |

| Urethane | Polyurethane | Moderate | Ester-based more susceptible than ether-based [15] |

| Carbonate | Polycarbonate | Moderate | Susceptible to base-catalyzed hydrolysis [16] [13] |

| Amide | Nylon (Polyamide) | Low | Susceptible to strong acids [13] |

| Anhydride | Poly(anhydride) | Very High | Highly reactive with water [12] |

Quantitative Data and Kinetics

Tracking the kinetics of degradation is essential for predicting material lifetime and performance. Key quantitative measures and models include [13]:

- Weight Loss and Water Adsorption: These are primary metrics tracked over time. Mass loss indicates the erosion of polymer material, while water uptake shows the extent of hydration.

- Molecular Weight Reduction: Techniques like Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) are used to monitor the decrease in molecular weight due to chain scission.

- Kinetic Models: Hydrolysis often follows first-order kinetics. The half-life of a polymer can be calculated if the rate constant is known.

- Arrhenius Relationship: This equation is used to model the temperature dependence of the degradation rate, allowing for the prediction of long-term behavior from accelerated aging tests at elevated temperatures.

Table 2: Experimental Degradation Data for Selected Polymers and Composites

| Polymer Material | Test Conditions | Key Quantitative Result | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLLA (Poly(L-lactic acid)) | pH 7.4, 37°C | Initial weight loss rate: 0.12 %/day [17] | Mass loss measurement |

| PLLA/Non-g-MCC Composite | pH 7.4, 37°C | Initial weight loss rate: 0.27 %/day [17] | Mass loss measurement |

| PLA/5MgPEI Composite | pH 7.4, 60°C (accelerated) | >90% mass loss after 7 weeks; higher resistance than neat PLA [14] | Mass loss, TGA, Raman Spectroscopy |

| Epoxy/Di-(1-aminopropyl-3-ethoxy) ether | 24h in water at 100°C | Tensile Strength: 37 MPa (vs. 41 MPa dry) [15] | Mechanical testing |

| Epoxy/Di-(1-aminopropyl-3-ethoxy) ether | After drying from wet state | Tensile Strength recovered to: 53 MPa [15] | Mechanical testing |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: My biodegradable polyester scaffold is degrading too quickly in vitro, losing mechanical strength before tissue healing can occur. What factors should I investigate?

- A1: A rapid loss of mechanical properties is a classic sign of aggressive hydrolytic scission. Your troubleshooting should focus on:

- Check Polymer Crystallinity: Polymers with low crystallinity degrade faster because water can penetrate the amorphous regions more easily. Verify the crystallinity of your starting material [12].

- Review Polymer Composition: Polyesters with a higher ratio of glycolic acid to lactic acid (in PLGA) or thinner device dimensions will degrade more quickly. Re-formulate with a slower-degrading monomer (e.g., L-lactide vs. D,L-lactide) or adjust the co-polymer ratio [12].

- Control pH and Test for Autocatalysis: The acidic byproducts (e.g., lactic acid) of polyester hydrolysis can lower the local pH inside the specimen, autocatalyzing further degradation. Ensure your buffer solution has sufficient capacity and volume to neutralize these acids, and consider the geometry of your sample to allow for byproduct diffusion [12] [14].

- Verify Test Conditions: Confirm that the temperature and pH of your in vitro environment are not excessively accelerating the test. Use a physiological temperature of 37°C and a pH of 7.4 unless accelerated data is the goal [14].

Q2: I am observing a sudden, dramatic drop in the glass transition temperature (Tg) of my epoxy adhesive after humidity aging. Is this reversible?

- A2: A significant drop in Tg is typically due to water absorption, which plasticizes the polymer by reducing intermolecular forces. To determine if it's reversible:

- Dry the Sample: Thoroughly dry the aged sample in a vacuum oven and re-measure the Tg.

- Interpret the Results:

- If Tg returns to its original value: The degradation was reversible plasticization. The water was acting as a temporary plasticizer and did not cause permanent chemical damage [15].

- If Tg does not fully recover: The drop is likely due to irreversible hydrolytic degradation. Permanent chain scission has occurred, reducing the polymer's molecular weight and crosslink density. This is common in ester-cured epoxies or polyurethanes [15].

Q3: The failure mode of my adhesive joint has shifted from cohesive to adhesive after exposure to a humid environment. Why has the interface failed?

- A3: This is a common failure mode driven by water's affinity for the substrate interface, not necessarily bulk hydrolysis.

- Primary Mechanism: Water Displacement: Water molecules permeate through the bulk adhesive, preferentially migrating to the hydrophilic interface. They then displace the adhesive by adsorbing onto the adherend surface (e.g., metal oxide), breaking the adhesive-adherend bonds [15].

- Secondary Mechanism: Interfacial Corrosion/Hydration: For metal adherends, water can hydrate the metal oxide layer (e.g., on aluminum or iron), forming a weak, gelatinous boundary layer that fails easily [15].

- Solution: Focus on improving interfacial stability by using silane coupling agents or choosing more hydrophobic adhesives that resist water permeation and displacement [15].

Q4: I need to accelerate the hydrolytic degradation of my PLA composite for a feasibility study. What are effective and controlled methods?

- A4: Accelerated tests are useful for comparative studies but may not perfectly replicate long-term in vivo degradation.

- Elevated Temperature: Conduct degradation studies at a higher temperature (e.g., 50°C or 60°C). This is the most common and controllable method, following the Arrhenius relationship. Ensure the temperature stays below the polymer's melting point [14].

- Alkaline Conditions: Use a buffer solution with a pH > 7.4 (e.g., pH 9-10). Ester bonds are highly susceptible to base-catalyzed hydrolysis, which will significantly speed up degradation [13].

- Incorporate Hydrophilic Fillers: As demonstrated in research, adding fillers like microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) or magnesium (Mg) particles can create pathways for water to penetrate the polymer matrix, accelerating bulk degradation [14] [17].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Monitoring PLA Hydrolysis

This protocol outlines a standard method for tracking the hydrolytic degradation of Poly(L-lactic acid) and its composites, adaptable to other polyesters [14] [17].

1. Objective: To quantify the hydrolytic degradation rate of PLA-based materials by measuring mass loss, water absorption, and thermal property changes under controlled, accelerated conditions.

2. Materials and Reagents: Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item | Function/Explanation | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer/Composite Films | The test material. | e.g., Neat PLA, PLA/5Mg, PLA/5MgTT [14]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Simulates physiological pH. | 0.1 M, pH 7.4 ± 0.2 is standard [14]. |

| Thermostatic Oven | Provides a constant, elevated temperature. | Set to 60°C for accelerated testing [14]. |

| Analytical Balance | Precisely measures mass changes. | Accuracy of at least 0.0001 g [14]. |

| Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA) | Measures thermal stability and residual mass. | -- |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Analyzes thermal transitions (Tg, crystallinity). | -- |

| Raman Spectrometer | Tracks chemical structure changes. | Can identify bond breakage [14]. |

3. Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare polymer films (e.g., by solution casting or compression molding) and cut them into standardized specimens (e.g., 30 mm x 10 mm x 50 μm) [14] [17].

- Baseline Characterization:

- Weigh each dry specimen to obtain the initial mass (W₀).

- Analyze a set of baseline samples using TGA, DSC, and Raman spectroscopy to characterize initial properties.

- Immersion Study:

- Place each specimen in a separate flask containing a sufficient volume of PBS (e.g., 5 mL) to ensure the solution's pH remains stable.

- Place the flasks in a thermostatic oven set at the desired temperature (e.g., 60°C for accelerated tests or 37°C for physiological conditions).

- Change the PBS solution daily to maintain a constant pH and remove dissolved oligomers [14].

- Sampling and Analysis: At predetermined time points (e.g., weekly for 7 weeks):

- Remove replicate samples (n=3) from the PBS.

- Gently wipe the surface with a paper towel and record the wet mass (Wwet).

- Dry the samples in an oven (e.g., at 60°C for 5 hours) until a constant mass is achieved, and record the dry mass (Wdry) [14].

- Perform TGA, DSC, and Raman analysis on the dried samples.

4. Data Analysis:

- Calculate Mass Loss (%):

[(W₀ - W_dry) / W₀] * 100 - Calculate Water Absorption (%):

[(W_wet - W_dry) / W_wet] * 100 - Plot the percentage mass loss and water absorption versus time to visualize degradation kinetics.

- Analyze Thermal Data: Use DSC to track changes in crystallinity and Tg over time. Use TGA to observe changes in thermal stability.

- Analyze Spectral Data: Use Raman spectra to identify the appearance of new peaks or disappearance of existing ones, indicating chemical changes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Materials and Their Functions in Hydrolytic Degradation Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| pH Buffers (e.g., PBS) | Maintains a constant hydrolytic environment, simulating different biological or environmental conditions [14]. |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., CDCl₃, DMSO-d6) | Essential for NMR spectroscopy to identify degradation products and quantify chain scission in solution [13]. |

| Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) Standards | Calibrates the GPC system to accurately measure the molecular weight distribution of polymers before and after degradation [13]. |

| Stabilizers & Inhibitors (e.g., Antioxidants) | Used as control additives to suppress secondary degradation mechanisms like oxidation, isolating the hydrolytic effect [13]. |

| Hydrophilic Fillers (e.g., MCC, Mg particles) | Incorporated into polymer composites to create pathways for water ingress, often used to study or accelerate bulk degradation [14] [17]. |

| Silane Coupling Agents | Used in adhesion studies to modify the interface and improve resistance to water displacement, mitigating adhesive failure [15]. |

The following diagram maps the core chemical mechanism of ester bond hydrolysis, the most common pathway for many biomedical and commodity polymers.

Photo-oxidation and UV-Driven Chain Scission Mechanisms

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting UV Degradation Experiments

| Problem Phenomenon | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Method | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent degradation rates between samples | Varying UV wavelengths or irradiance levels; Inhomogeneous sample preparation | Spectroradiometry to measure UV source output; Check polymer sensitivity spectra [18] | Standardize UV source and exposure distance; Use monochromatic filters matching polymer's activation maxima |

| Unexpected polymer yellowing instead of chain scission | Competing oxidation pathways dominating over chain scission | FTIR analysis for carbonyl index vs. hydroperoxide formation [19] | Incorporate pro-oxidants (e.g., metal stearates) to favor β-scission; Adjust UV intensity |

| No significant molecular weight reduction observed | UV stabilizers present in commercial polymer resins; Insufficient exposure time | HPLC/GPC analysis of molecular weight distribution; Review polymer resin datasheets [19] | Use unstabilized polymer resins; Extend exposure duration or increase irradiance |

| Surface cracking without bulk property changes | Heterogeneous degradation; UV penetration limited to surface layers | Cross-sectional microscopy; Depth-profiling FTIR [19] | Reduce sample thickness; Consider sample stirring/rotation during exposure |

| Poor correlation between lab tests and field performance | Non-representative accelerated aging conditions; Missing environmental co-factors | Review climatic data (irradiation, temperature, humidity) for target region [18] | Incorporate thermal cycling and moisture exposure in test protocol; Match UV spectrum to solar radiation |

Advanced Technical Support: Degradation Mechanism Analysis

Table 2: Diagnostic Techniques for Chain Scission Verification

| Analytical Technique | Data Output | Interprets Chain Scission Via | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) | Molecular weight distribution, dispersity (ĐM) | Decrease in number-average molecular weight (Mn); Increased dispersity | Primary method for quantifying chain scission efficiency [20] [19] |

| Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy | Carbonyl Index (CI); Hydroxyl Index | Increase in carbonyl (C=O) absorption bands (~1715 cm-1) | Tracks photo-oxidation products; Norrish reactions [19] |

| Tensile Testing | Elongation at break; Tensile strength | Reduction in mechanical properties | Chain scission reduces polymer's load-bearing capacity [18] [21] |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Crystallinity changes | Increased crystallinity due to chain scission in amorphous regions | Shorter chains can reorganize into more ordered structures [19] |

| Monte Carlo Simulation | Predicted molecular weight decrease | Models stochastic chain scission events | Validates experimental data; Predicts degradation pathways [20] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What specific UV wavelengths are most damaging to common polymers, and why?

The photodegradation of polymers is highly wavelength-dependent. Each polymer has specific "activation spectra maxima" where it most strongly absorbs UV radiation, leading to chain breakage. Critical wavelengths for common polymers include: Polypropylene (290-300, 330, 370 nm), Nylon (290-315 nm), Polycarbonate (280-310 nm), ABS (300-310, 370-385 nm), and Polyurethane aromatic (350-415 nm) [18]. The most aggressive degradation occurs in the UVB range (280-315 nm) due to higher photon energy, which can directly break chemical bonds in the polymer backbone [18].

Q2: How do environmental factors like geographic location affect UV degradation rates?

Geographic location significantly impacts degradation kinetics due to variations in solar irradiation. The annual UV radiation energy exposure varies dramatically worldwide - for example, approximately 220 kcal/cm²/year in Sudan compared to 70 kcal/cm²/year in Sweden [18]. This three-fold difference means the same polymer formulation may degrade three times faster in tropical regions compared to temperate zones. Researchers must account for these variations when designing accelerated aging tests to predict real-world service life.

Q3: What is the relationship between chain scission and subsequent biodegradation?

Chain scission plays a critical role in enhancing polymer biodegradability. Research demonstrates that reducing molecular weight through UV-induced chain scissions significantly increases biodegradation rates. For Polyethylene Glycol (PEG), a decrease in molecular weight from approximately 6,380 Da to lower fragments dramatically enhanced biodegradation in soil and sediment, with nearly complete mineralization to CO₂ within 150 days [20]. Microbial enzymes can more effectively assimilate lower molecular weight fragments (typically <5,000 Da), making initial abiotic UV degradation a crucial prerequisite for efficient biological breakdown [20] [19].

Q4: How do pro-oxidants like metal stearates accelerate photo-oxidation?

Metal stearates (e.g., iron or manganese stearate) function as pro-oxidants by catalyzing the decomposition of hydroperoxides (ROOH) into reactive alkoxyl (RO•) and hydroxyl (HO•) radicals through redox cycling [19]. This significantly accelerates the initiation phase of photo-oxidation, leading to faster chain scission. Studies show these additives demonstrate concentration-dependent effects, with even minor concentrations (0.5-5%) substantially reducing the molecular weight of polyethylene sheets during UV exposure [19].

Q5: What are the key differences between Norrish Type I and Type II reactions in polymer photodegradation?

Norrish Type I reactions involve direct cleavage of carbonyl-containing polymers at the bond adjacent to the carbonyl group, producing free radicals that propagate further degradation. Norrish Type II reactions involve intramolecular hydrogen transfer from the gamma position to the carbonyl oxygen, forming an enol and ultimately leading to chain scission without free radical production. Both mechanisms are significant in polymers like PBAT that contain carbonyl groups in their backbone, with the specific pathway depending on polymer structure and environmental conditions [22].

Experimental Protocols

Standard Protocol: UV-Induced Chain Scission in Polyethylene Glycol (PEG)

Purpose: To quantitatively measure UV-driven chain scission and its effect on molecular weight distribution and subsequent biodegradability.

Materials:

- 13C-labeled PEG (Mₙ ≈ 6,380 ± 400 Da)

- UV radiation source (e.g., UV-C lamp, 254 nm)

- Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) for hydroxyl radical generation

- HPLC system with Charged Aerosol Detector and Mass Spectrometer (HPLC-CAD-MS)

- Soil/sediment samples for biodegradation incubation

- 13CO₂ trapping and quantification system

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare triplicate solutions of 13C-PEG (5 mg/mL) in appropriate aqueous buffer [20].

- Hydroxyl Radical Generation: Add H₂O₂ to solutions and expose to UV radiation to generate •OH radicals photochemically. Maintain environmentally relevant [•OH]ss concentrations (10⁻¹⁵ to 10⁻¹⁷ M) [20].

- Time-Course Exposure: Expose samples for predetermined intervals (e.g., 0, 15, 30, 45 minutes) with constant stirring.

- Molecular Weight Analysis: Analyze samples by HPLC-CAD-MS to determine molecular weight distribution changes post-exposure.

- Biodegradation Assay: Incubate unreacted and •OH-reacted PEG solutions in soil and sediment for 150 days. Quantify 13CO₂ production as mineralization indicator [20].

- Data Analysis: Calculate average number of scissions per initial PEG chain using: SıC(t) = (1 - e⁻ᵏ¹·ᵗ) × (Mₙ(t₀)/MWMonomer) [20].

Advanced Protocol: Monte Carlo Simulation of Chain Scission

Purpose: To computationally model and predict stochastic chain scission events during polymer degradation.

Software: R (version 4.4.0) via RStudio [20]

Methodology:

- Initialization: Define an ensemble of polymer chains with lengths following a normal distribution around characteristic mean chain length λ.

- Reaction Probability: Assign chain length-specific reaction rate constants: k(n) = 0.8·kM·n for n ≤ 30; k(n) = 0.8·kM·30·(n/30)⁰·⁵⁷ for n > 30, where kM is the intrinsic reaction rate constant [20].

- Stochastic Selection: Randomly select chains for cleavage with probability proportional to their reaction rate constants.

- Chain Scission Simulation: For each selected chain, randomly assign cleavage site along backbone, generating two shorter chains.

- Iteration: Update chain population after each scission event and repeat for multiple steps.

- Validation: Compare simulation results with experimental GPC data for molecular weight reduction.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for UV Degradation Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Mechanism | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pro-oxidants | Iron (III) stearate, Manganese (II) stearate | Accelerate photo-oxidation via catalytic decomposition of hydroperoxides [19] | Concentration-dependent effect (0.5-5%); May contribute color; Enhances fragmentation |

| UV Stabilizers | Hindered Amine Light Stabilizers (HALS), Benzotriazoles, Benzophenones | Compete with chromophores to absorb UV radiation; Trap free radicals [18] | HALS ineffective for PVC; Benzotriazoles suitable for transparent applications |

| Polymer Substrates | 13C-labeled PEG, Unstabilized LDPE/HDPE, PBAT/TPS blends | Enable fate tracking; Eliminate interference from commercial stabilizers [20] [22] [19] | 13C-labeling allows precise biodegradation monitoring via 13CO₂ detection |

| Radical Generators | Hydrogen peroxide, Nitrate/Nitrite, Dissolved Organic Matter | Source of hydroxyl radicals under UV irradiation [20] | Environmentally relevant •OH concentrations: 10⁻¹⁵ to 10⁻¹⁷ M |

| Reference Materials | Carbon black, Rutile titanium oxide | UV absorbers for control experiments; Reference stabilizers [18] | Carbon black one of most effective UV absorbers; Titanium oxide effective at 300-400 nm |

Mechanism and Workflow Visualization

Polymer UV Degradation Mechanism

Polymer UV Degradation Pathway

Experimental Workflow for Chain Scission Study

Chain Scission Study Workflow

Enzymatic and Biological Degradation Pathways for Biopolymers

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary enzymatic mechanisms for degrading different biopolymer types? Biopolymers are degraded through distinct enzymatic mechanisms based on their chemical structure. For polyesters (e.g., PLA, PET), the primary mechanism is hydrolysis, where enzymes like cutinases and hydrolases cleave ester bonds by inserting water molecules [23]. For hydrocarbon-based polymers (e.g., PE, PP) and lignin, the mechanism is oxidation, catalyzed by oxidoreductases such as laccases, peroxidases, and lignin peroxidases, which attack carbon-carbon bonds or aromatic rings [24] [25] [23]. For polysaccharides (e.g., cellulose, starch), hydrolytic enzymes like cellulases (endo- and exo-glucanases) and amylases cleave glycosidic bonds [26] [27].

Q2: Which microorganisms are most effective for degrading lignin, and what are their limitations? Fungi, particularly white-rot fungi, are the most efficient lignin degraders, employing peroxidases and laccases [28] [25]. Key bacterial genera include Bacillus (e.g., Bacillus cereus with 89% degradation), Pseudomonas, Rhodococcus, and Streptomyces [29]. A major limitation of fungi is their long pretreatment period and poor environmental adaptability, whereas bacteria, though more robust, often exhibit slower and more limited delignification [25] [29].

Q3: What are the critical factors influencing the degradation rate of cellulose in laboratory experiments? The degradation rate of cellulose is highly dependent on both the microbial strain and cultivation conditions. Key factors include [26]:

- Temperature: Optimal range is typically 30-35°C.

- pH: A neutral to slightly acidic pH (e.g., 6-7) is often ideal.

- Aeration: Rotation speed (e.g., 140 r/min) ensures adequate oxygen supply.

- Substrate dosage: The concentration of the biomass (e.g., 1% w/v bamboo powder). Under optimized conditions, Bacillus velezensis achieved a 33.12% cellulose degradation rate [26].

Q4: How can I improve the degradation efficiency of semi-crystalline polymers like PET or PLA? Semi-crystalline polymers are recalcitrant due to their crystalline regions. Efficiency can be improved by:

- Pretreatment: Physical (e.g., steam explosion), chemical (e.g., ionic liquids), or UV/thermal oxidative methods disrupt crystallinity and enhance enzyme access [30] [31].

- Enzyme Engineering: Using engineered enzymes (e.g., PETase variants) with higher activity [23].

- Process Optimization: Using enzyme cocktails and controlling parameters like temperature and pH [32] [23].

Q5: What are the common analytical methods to confirm and quantify polymer biodegradation? Standard methods to analyze biodegradation include [26] [32]:

- Weight Loss: Measuring mass loss of the polymer sample.

- Spectroscopy: FTIR to detect changes in chemical functional groups.

- Chromatography: LC-MS to identify degradation products and intermediates.

- Microscopy: SEM to observe surface erosion and physical changes.

- Calorimetry: DSC and XRD to monitor changes in crystallinity.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent or Low Degradation Rates

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal Environmental Conditions | - Measure temperature and pH in the reaction vessel.- Check agitation speed for aerobic microbes. | - Re-optimize parameters using RSM [26]. For many bacteria, maintain pH 6-7, temperature 30-35°C, and agitation at 140 rpm [26]. |

| Low Enzyme Activity or Production | - Assay enzyme activity (e.g., cellulase, laccase) in the supernatant.- Run SDS-PAGE to check enzyme expression profiles. | - Add inducers (e.g., lignocellulosic biomass for ligninases) [28].- Use immobilized enzymes or enzyme cocktails for synergy [23]. |

| Poor Microbial Growth | - Measure OD600 to monitor cell density.- Check for microbial contamination via microscopy. | - Ensure medium contains essential nutrients and a co-substrate (e.g., glucose) to support initial growth [29]. |

| High Polymer Crystallinity | - Characterize polymer with XRD or DSC to determine crystallinity degree. | - Implement a pretreatment step (e.g., thermal, chemical) to reduce crystallinity [30] [31]. |

Problem: Difficulty in Identifying Degradation Products

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Complex Product Mixture | - Use LC-MS or GC-MS for high-resolution separation and identification. | - For lignin, map products against known metabolic pathways (e.g., β-ketoadipate pathway) [28] [29]. |

| Low Concentration of Products | - Concentrate the sample via lyophilization or solid-phase extraction. | - Scale up the degradation reaction or use sensors (e.g., fluorescence-based) for real-time monitoring [29]. |

| Inadequate Analytical Standards | - Cross-reference detected masses with databases (e.g., KEGG, MetCyc). | - Synthesize or purchase suspected monomeric standards (e.g., vanillic acid for lignin, glucose for cellulose) for confirmation [26]. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Cellulose Degradation by Bacteria

This protocol is adapted from a study on degrading cellulose in bamboo forest waste using Bacillus velezensis [26].

1. Materials and Reagents

- Microorganism: Bacillus velezensis (or other cellulolytic strain).

- Culture Medium: Luria-Bertani (LB) medium.

- Substrate: Bamboo forest waste powder (150 μm particle size).

- Staining Solution: 1 mg/mL Congo red solution.

2. Experimental Workflow

3. Key Steps and Parameters

- Screening & Isolation: Inoculate soil samples in LB with microcrystalline cellulose. Incubate at 30°C with shaking (140 rpm) for 72 h. Streak on solid LB plates and screen for cellulose-degraders using Congo Red assay (clear halos indicate activity) [26].

- Optimization: Use Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to optimize pH, temperature, and agitation speed. For B. velezensis, optimum was pH 6, 35°C, and 140 rpm [26].

- Degradation Assay: Inoculate purified bacteria into LB, incubate for 24 h to create seed culture. Centrifuge, resuspend in saline, and add bamboo powder (1% w/v). Incubate under optimal conditions for up to 72 h [26].

- Analysis: Sample periodically. Measure cellulose content. Use FTIR for chemical changes, XRD for crystallinity, SEM for surface morphology, and LC-MS to identify products like cellobiose and UDP-glucose [26].

Protocol 2: Evaluating Lignin Degradation by Bacterial Consortia

1. Materials and Reagents

- Microorganisms: Bacterial strains such as Bacillus cereus, Pseudomonas putida, or Rhodococcus jostii [29].

- Culture Medium: Mineral salt medium or LB.

- Substrate: Alkali lignin or kraft lignin.

- Reagents: For enzyme assays (e.g., laccase, peroxidase).

2. Experimental Workflow

3. Key Steps and Parameters

- Culture Preparation: Grow bacterial precultures to mid-log phase. Harvest, wash, and resuspend in fresh medium to standard cell density [29].

- Lignin Addition & Incubation: Add filter-sterilized alkali or kraft lignin (e.g., 0.1-0.5% w/v) to the culture. Incubate aerobically with shaking (e.g., 150 rpm) at 30°C for several days to weeks [29].

- Monitoring & Sampling: Monitor bacterial growth (OD600). Sample periodically to measure residual lignin and enzyme activities [29].

- Analysis:

- Lignin Degradation: Measure the remaining lignin content by UV-Vis spectrophotometry (at 280 nm) or SEC for molecular weight changes. Degradation can reach 52-89% with efficient strains like Bacillus cereus [29].

- Enzyme Assays: assay culture supernatant for laccase (oxidation of ABTS), manganese peroxidase (MnP), and lignin peroxidase (LiP) [28] [25].

- Metabolite Identification: Use HPLC or GC-MS to identify low-molecular-weight aromatic compounds (e.g., vanillin, ferulic acid) funneled into central metabolic pathways [28] [29].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Strains (e.g., Bacillus velezensis, Pseudomonas putida) [26] [29] | Primary biocatalysts for depolymerization. | - Check culture collections (e.g., ATCC, DSMZ).- Optimize growth conditions for each strain. |

| Fungal Strains (e.g., Aspergillus, Penicillium) [24] | Source of potent ligninolytic and cellulolytic enzymes. | - Requires longer cultivation times than bacteria.- Handle spores in appropriate biosafety cabinets. |

| Purified Enzymes (e.g., Cutinase, Laccase, PETase, Cellulase) [24] [30] [23] | Controlled degradation studies and mechanism elucidation. | - Can be expensive; consider in-house production.- Check stability at working pH and temperature. |

| Alkali/Kraft Lignin [29] | Standardized substrate for lignin degradation assays. | - Solubility can vary by source and pretreatment.- Filter-sterilize before adding to cultures. |

| Microcrystalline Cellulose / Biomass Powder [26] [27] | Substrate for cellulose degradation studies. | - Standardize particle size (e.g., 150μm).- Can be used as an enzyme inducer. |

| Congo Red Staining Solution [26] | Qualitative screening for cellulase-producing microbes. | - Clear halos on dyed cellulose plates indicate hydrolysis.- Stain for 1 hour before observation. |

| ABTS (2,2'-Azinobis-(3-Ethylbenzthiazolin-6-Sulfonate)) | Chromogenic substrate for laccase activity assays. | - Monitor oxidation by increase in absorbance at 420 nm.- Prepare fresh solutions. |

| Response Surface Methodology (RSM) Software (e.g., Design-Expert) [26] | Statistical optimization of culture/degration conditions. | - Efficiently models interaction of multiple factors.- Reduces total number of experiments required. |

Key Degradation Pathways

Diagram: Major Bacterial Degradation Pathways for Lignin and Cellulose

Core Concepts: Understanding Polymer Degradation

This section addresses fundamental questions about the processes that affect polymer stability and performance in experimental and applied contexts.

FAQ: What are the primary modes of polymer chain scission, and how do they impact my experimental outcomes?

Chain scission, the breaking of polymer chains, is a central process in degradation. The mode of scission directly influences changes in molecular weight and material properties. Understanding these differences is crucial for designing reproducible experiments and interpreting results accurately. The two primary modes are:

- Chain-End Scission (or End-Cleavage): Degradation occurs sequentially from the chain ends. This process is likened to pearls falling off one end of a cut necklace, steadily reducing the chain length one unit at a time [1].

- Random Chain Scission: Degradation occurs at random points along the polymer backbone. This is like cutting a necklace at multiple random points, rapidly splitting it into several shorter fragments [1].

A recent meta-analysis revealed that a polymer's solubility is the most critical factor determining the dominant scission mode, overturning the common assumption that molecular chemistry alone is the primary governor [1]. This finding has direct implications for choosing the right polymer-solvent system for your experiments.

FAQ: What common environmental factors trigger polymer degradation in laboratory settings?

Polymer degradation can be initiated by several factors present in standard lab environments. The most significant include [33] [34]:

- Heat (Thermal Degradation): High temperatures during processing or storage can cause chain scission or cross-linking, even in the absence of oxygen [33].

- Light (Photo-oxidation): Ultraviolet (UV) radiation from ambient light, combined with oxygen, initiates free radical chain reactions that break polymer chains and lead to embrittlement and discoloration [33].

- Mechanical Shear: High shear forces during mixing, extrusion, or injection molding can physically snap polymer chains, particularly the longest and most entangled ones [33] [35].

- Chemical Exposure:

- Hydrolysis: Polymers with hydrolyzable backbone bonds (e.g., esters, carbonates, amides) are susceptible to chain cleavage by water [33] [6].

- Oxidation: Exposure to oxidative agents, including atmospheric oxygen, can lead to chain scission and the formation of new, often undesired, functional groups [33].

- Chlorine & Ozone: Trace chlorine in water or ozone in the air can attack specific polymers, leading to cracking and failure [33].

▼ Table 1: Polymer Degradation Types and Mechanisms

| Degradation Type | Primary Trigger(s) | Key Mechanism(s) | Common Polymers Affected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal/Oxidative [33] | Heat, Oxygen | Chain scission, Cross-linking | Polypropylene (PP), Polyethylene (PE) [35] |

| Photo-oxidative [33] | UV Light, Oxygen | Free radical formation, Chain scission | Most plastics (e.g., PP, PE, PS) |

| Hydrolytic [33] [6] | Water, Acids, Bases | Cleavage of hydrolyzable bonds (e.g., ester, carbonate) | Polyesters (e.g., PLGA, PET), Polycarbonates (PC) |

| Mechanical [33] [35] | Shear Stress, Physical Force | Chain scission under stress | All thermoplastics during processing |

| Biological [33] | Microorganisms | Enzymatic cleavage of polymer chains | Aliphatic polyesters (e.g., PLA), natural polymers |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

This section provides targeted solutions for frequently encountered problems in polymer-related research.

Problem: Uncontrolled Burst Release in Long-Acting Injectable Formulations

- Issue: A significant initial dose of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) is released from the polymer matrix before stable, sustained release is achieved, potentially compromising therapeutic efficacy and safety [36].

- Root Cause: Traditional polymer systems like PLGA are relatively rigid in their chemistry. Their degradation and drug release profiles can be difficult to fine-tune, often leading to unpredictable or high initial burst release [36].

- Solutions:

- Investigate Advanced Polymer Platforms: Consider polymers engineered for precise burst control. For instance, platforms incorporating backbone functionalization and controlled crosslinking offer a broader toolkit to adjust release kinetics and minimize burst by better stabilizing the API within the matrix [36].

- Optimize Processing Parameters: Shear forces and temperatures during processing can cause initial chain scission, creating weak points and low molecular weight fragments that contribute to burst release. Carefully monitor and optimize these parameters [33].

Problem: Inconsistent Results During Multiple Recycling or Reprocessing Loops

- Issue: The properties of a recycled polymer (e.g., viscosity, strength) change unpredictably with each successive reprocessing cycle, hindering its use in high-value applications.

- Root Cause: Repeated thermomechanical processing leads to cumulative degradation. For polypropylene (PP), this primarily manifests as chain scission, reducing molecular weight. For polyethylene (HDPE), chain scission can be followed by re-aggregation via branching, which increases molecular weight but alters properties. These competitive processes make the material's behavior hard to predict [35].

- Solutions:

- Monitor Key Indicators: Track the Melt Flow Index (MFI) and complex viscosity during recycling. A rising MFI indicates dominant chain scission (in PP), while changes in viscosity profiles suggest branching (in HDPE) [35].

- Use Stabilizers: Incorporate antioxidants and stabilizers to mitigate thermal and oxidative degradation during high-temperature processing [33].

- Control Processing Atmosphere: Minimize oxygen availability during processing to reduce oxidative degradation [35].

Problem: Destabilization of Biologics in Sustained-Release Formulations

- Issue: Sensitive biologic drugs (e.g., peptides, monoclonal antibodies) lose their structural and functional integrity when encapsulated within a biodegradable polymer matrix.

- Root Cause: Many established polymer systems (e.g., PLGA) generate acidic byproducts (e.g., lactic and glycolic acids) during their breakdown. This creates a hostile local chemical environment that can denature or fragment delicate biologic molecules [36].

- Solutions:

- Select Biocompatible Polymers: Utilize polymer platforms specifically designed to maintain biologic stability. These may lack acidic degradation products or have functionalized backbones that better stabilize the encapsulated drug [36].

- Adjust Microenvironment pH: Incorporate basic salts or other pH-modifying agents within the formulation to buffer the acidic microclimate.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in the troubleshooting guides.

Protocol: Monitoring Polymer Degradation During Multiple Extrusion Cycles

This protocol is adapted from research on recycling polyolefins and is useful for studying processing-induced degradation [35].

- Objective: To quantify the extent of thermal and mechanical degradation in a polymer subjected to multiple reprocessing loops.

- Materials:

- Polymer granules (e.g., Polypropylene impact copolymer or HDPE)

- Injection molding machine

- Granulator/Crusher

- Procedure:

- Step 1: Initial Characterization. Determine the baseline Melt Flow Index (MFI), molecular weight distribution (via GPC), and tensile properties of the virgin polymer.

- Step 2: Processing Loop. Process the polymer via injection molding using standardized parameters (temperature, pressure, screw speed).

- Step 3: Regrinding. After molding, regrind the test specimens into granules.

- Step 4: Repeating Cycles. Repeat Steps 2 and 3 for the desired number of cycles (e.g., 5-10 loops).

- Step 5: In-line Monitoring. Record processing parameters like metering time and maximum injection pressure for each cycle, as these can be indicators of changing material viscosity [35].

- Step 6: Post-Cycle Analysis. After every 1-2 cycles, characterize the reground material using MFI, rheology (complex viscosity), and FTIR to track structural changes.

- Expected Outcomes:

- For PP, expect a steady increase in MFI and a decrease in complex viscosity, indicating dominant chain scission [35].

- For HDPE, MFI changes may be less straightforward due to competitive branching; rheological analysis is key.

Protocol: Catalytic Degradation of Condensation Polymers for Chemical Recycling

This protocol outlines the use of organocatalysts to degrade polymers like PET into repolymerizable monomers, a key method in chemical recycling [6].

- Objective: To efficiently degrade a condensation polymer (e.g., PET) into its core monomer or other valuable building blocks using an organic catalyst.

- Materials:

- Polymer substrate (e.g., PET flakes)

- Organic catalyst (e.g., 1,5,7-Triazabicyclo[4.4.0]dec-5-ene (TBD) or 1,8-Diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU))

- Nucleophile (e.g., Ethylene Glycol for glycolysis, Benzylamine for aminolysis)

- Round-bottom flask, condenser, heating mantle, magnetic stirrer.

- Procedure:

- Step 1: Reaction Setup. Combine polymer, catalyst (e.g., 1-10 mol%), and a large excess of nucleophile in the flask.

- Step 2: Degradation. Heat the mixture with stirring under an inert atmosphere. For example, heat PET with ethylene glycol and 1 mol% DBU at 190°C for 2 hours [6].

- Step 3: Termination & Isolation. Cool the reaction mixture. The product, such as bis(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalate (BHET) from glycolysis, can often be isolated by crystallization or filtration [6].

- Step 4: Analysis. Analyze the product using techniques like NMR, MS, and HPLC to confirm identity and purity.

- Key Consideration: The efficiency is highly dependent on the catalyst-nucleophile pair. TBD operates via a dual hydrogen-bonding mechanism, activating both the polymer and the nucleophile [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

▼ Table 2: Essential Reagents for Polymer Degradation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| TBD (1,5,7-Triazabicyclo[4.4.0]dec-5-ene) [6] | Organocatalyst for degradation/chemical recycling of polyesters (e.g., PET) and polycarbonates. Effective in glycolysis and aminolysis. | Operates via a dual hydrogen-bonding mechanism. Commercially available and bench-stable. |

| DBU (1,8-Diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene) [6] | Organocatalyst for transesterification. Highly efficient in PET glycolysis with ethylene glycol. | Often more effective than TBD in specific glycolytic systems due to the "push-pull" theory of activation. |

| Ethylene Glycol [6] | Nucleophile (Glycolysis Agent) for depolymerizing polyesters like PET to yield BHET monomer. | Common, low-cost reagent. The choice of diol can influence catalyst efficiency. |

| Benzylamine [6] | Nucleophile (Aminolysis Agent) for degrading PET into terephthalamides, enabling upcycling. | Higher nucleophilicity than alcohols, allowing for non-catalytic reactions, which are enhanced by catalysts like TBD. |

| Hindered Amine Light Stabilizers (HALS) [33] | Stabilizer to inhibit photo-oxidative degradation by scavenging free radicals. | Critical for extending the service life of polymers exposed to UV light. |

| Antioxidants [33] | Stabilizer to prevent thermal-oxidative degradation during polymer processing and long-term use. | Often added to virgin polymer to survive multiple processing cycles. |

Analytical Techniques and Predictive Modeling for Degradation Analysis

Troubleshooting Guides

FTIR Spectroscopy Troubleshooting

Problem 1: Noisy or Distorted Spectra

- Potential Cause: Instrument vibration from nearby equipment (pumps, lab activity) or physical disturbances [37] [38].

- Solution: Ensure the spectrometer is placed on a stable, vibration-free bench. Isolate the instrument from potential sources of vibration [37].

Problem 2: Negative Absorbance Peaks

- Potential Cause: A contaminated or dirty ATR (Attenuated Total Reflection) crystal when the background spectrum was collected [37] [38].

- Solution: Clean the ATR crystal thoroughly with an appropriate solvent, collect a new background spectrum, and then re-analyze your sample [37] [38].

Problem 3: Distorted or Saturated Peaks in Diffuse Reflection

- Potential Cause: Processing data in absorbance units instead of Kubelka-Munk units [37] [38].

- Solution: Convert the spectral data to Kubelka-Munk units for a correct and interpretable representation [37] [38].

Problem 4: Weak or Unrepresentative Spectra from Plastic Samples

- Potential Cause: Surface effects, such as migration of plasticizers, additives, or surface oxidation, may not represent the bulk material's chemistry [37] [38] [39].

- Solution: For plastics, compare the spectrum from the "as-received" surface with a spectrum taken from a freshly cut interior surface to differentiate between surface and bulk chemistry [37] [38].

Problem 5: Poor Quality ATR Spectrum from Solid Samples

- Potential Cause: Inadequate contact between the hard ATR crystal and a porous or rigid solid sample (e.g., wood block) [40].

- Solution: For rigid solids, use a small chip or powdered sample to ensure better contact with the crystal. Applying high pressure to a large, hard sample often does not improve contact [40].

NMR Spectroscopy Troubleshooting

Problem 1: Inability to Determine Stereochemistry or 3D Configuration

- Potential Cause: Relying solely on 1D NMR ((^1)H or (^{13})C) which provides limited information on spatial arrangement [41].

- Solution: Employ 2D NMR experiments, specifically NOESY (Nuclear Overhauser Effect Spectroscopy) or ROESY (Rotating-frame Overhauser Effect Spectroscopy), which provide information about the spatial proximity between atoms, crucial for determining three-dimensional structure and stereochemistry [41].

Problem 2: Difficulty Establishing Long-Range Carbon-Proton Connectivity

- Potential Cause: Standard (^1)H-(^{13})C correlation experiments (HSQC/HMQC) only show couplings between directly bonded nuclei [41].

- Solution: Perform an HMBC (Heteronuclear Multiple Bond Correlation) experiment. This technique detects long-range couplings over two or three bonds, helping to establish the connectivity of molecular fragments and identify quaternary carbons [41].

Problem 3: Challenges with Complex Mixtures or Isomeric Impurities

- Potential Cause: Co-eluting or structurally similar compounds can be difficult to resolve and identify with chromatographic techniques alone [41].

- Solution: Use NMR as an orthogonal technique. NMR is highly sensitive to differences in the magnetic environment, making it excellent for distinguishing positional isomers, tautomers, and other structurally similar impurities that might be missed by LC-MS [41].

Problem 4: Distinguishing Surface vs. Bulk Polymer Degradation

- Potential Cause: FTIR-ATR primarily probes surface chemistry, which may not reflect changes in the bulk material [37] [38] [39].

- Solution: Use Solid-State NMR (SSNMR). SSNMR is a powerful, non-destructive technique that can analyze the bulk material without surface-specific limitations. It provides detailed information on molecular structure, dynamics, and crystallinity, offering a complementary bulk perspective to surface-sensitive FTIR-ATR.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How can I use FTIR to monitor and quantify polymer degradation? FTIR can track the formation or disappearance of specific functional groups that indicate degradation. The degree of change is often quantified using established indexes [42]:

- Carbonyl Index (CI): Measures the formation of carbonyl groups (C=O), a key product of photo-oxidation and thermal-oxidative degradation. It is calculated as the ratio of the absorbance around 1710-1740 cm⁻¹ to an internal reference peak (often related to C-H stretching).

- Hydroxyl Index (HI): Measures the formation of hydroxyl groups (O-H), which can increase during oxidation. It uses the absorbance in the 3100-3600 cm⁻¹ region.

- Carbon-Oxygen Index (COI): Tracks changes in C-O bond vibrations, common in alcohols and ethers.

FAQ 2: What are the main degradation pathways for polymers during processing? The primary mechanisms are [3]:

- Thermal Degradation: Chain scission or depolymerization induced by heat.

- Thermo-mechanical Degradation: Combination of heat and shear stress breaking polymer chains.

- Thermal-oxidative Degradation: Oxidation reactions facilitated by heat and trace oxygen.

- Hydrolysis: Chain scission due to reaction with water, especially critical for polyesters.

FAQ 3: When should I use NMR over FTIR for structure elucidation? The techniques are complementary, but NMR is superior for full molecular framework determination. The table below summarizes key differences [41]:

| Feature | NMR | FTIR |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Detail | Full molecular framework, stereochemistry, dynamics | Functional group identification, molecular fingerprint |

| Stereochemistry | Excellent (via NOESY/ROESY) | Not applicable |

| Quantification | Accurate without external standards | Limited |

| Sample Preparation | Requires deuterated solvents | Simpler (solid/liquid, ATR) |

| Key Strength | Complete structure elucidation, isomer distinction | Rapid identification, monitoring specific functional groups |

FAQ 4: My FTIR spectrum has an abnormal baseline or strange peaks. What should I check first? Always verify your sample preparation and instrument background [43].

- Sample Preparation: Ensure your sample is clean, dry, and properly prepared (e.g., well-ground for solids, bubble-free for liquids).

- Background Collection: Collect a fresh background spectrum with the accessory in place but no sample. A dirty accessory or changing environmental conditions (e.g., humidity, CO₂ levels) will cause anomalies [38] [43].

- Instrument Maintenance: Check for dirty optics or exhausted desiccants, which can affect performance [43].

Experimental Protocols for Polymer Degradation Studies

Protocol 1: Assessing Polymer Weathering using FTIR Spectroscopy

This protocol outlines the use of ATR-FTIR to evaluate the chemical changes in polymers after artificial ageing or environmental weathering [42].

- Objective: To qualitatively and quantitatively assess the degree of polymer ageing by tracking changes in functional groups using spectral indexes.

- Materials:

- FTIR Spectrometer with ATR accessory (e.g., diamond crystal)

- Pristine polymer samples (e.g., PE, PP, PS pellets or fragments)

- Environmentally weathered microplastics (for comparison)

- Climate chamber with UV lamps

- Oven for thermal ageing

- Methodology:

- Baseline Measurement: Obtain ATR-FTIR spectra of all pristine polymer samples. Use settings such as 32 scans per spectrum at 4 cm⁻¹ resolution over 4000–500 cm⁻¹ [42].

- Artificial Ageing:

- Post-Ageing Analysis: After each ageing step, collect new ATR-FTIR spectra using the same instrument parameters.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the Carbonyl Index (CI), Hydroxyl Index (HI), and Carbon-Oxygen Index (COI) for each spectrum.

- Compare the indexes of aged samples against the pristine baseline to quantify degradation.

- Compare the spectra of artificially aged samples with those of naturally weathered environmental microplastics.

Protocol 2: Structure Elucidation of Degraded Polymer Products by NMR

This protocol describes the use of 1D and 2D NMR techniques to identify and confirm the molecular structure of unknown degradation products or impurities in polymers [41].

- Objective: To achieve full structural characterization of a polymer degradant, including its connectivity and stereochemistry.

- Materials:

- High-field NMR Spectrometer (e.g., 400 MHz or higher)

- Deuterated solvent suitable for the polymer/degradant (e.g., CDCl₃, DMSO-d6)

- Isolated degradant sample

- Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve the isolated degradant in a deuterated solvent.

- 1D NMR Analysis:

- Acquire ¹H NMR to identify hydrogen environments, chemical shifts, and integration.

- Acquire ¹³C NMR (with DEPT editing if possible) to identify the number and type of distinct carbon environments (CH₃, CH₂, CH, C) [41].

- 2D NMR Analysis:

- Perform COSY (Correlation Spectroscopy) to identify spin-spin couplings between protons, revealing connectivity through bonds [41].

- Perform HSQC (Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence) to correlate directly bonded carbon and proton nuclei [41].

- Perform HMBC (Heteronuclear Multiple Bond Correlation) to identify long-range (²JCH, ³JCH) carbon-proton couplings, connecting molecular fragments across heteroatoms or quaternary carbons [41].

- If stereochemistry is in question, perform NOESY or ROESY to determine spatial proximity between atoms through the Nuclear Overhauser Effect (NOE) [41].

- Data Interpretation: Correlate all spectral data to piece together the complete molecular structure, confirming the identity of the degradant.

Key Degradation Pathways in Polymers

The following diagram illustrates the common molecular pathways of polymer degradation during processing, which can be investigated using FTIR and NMR.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table lists key reagents and materials essential for conducting FTIR and NMR experiments focused on polymer degradation.

| Item | Function | Example Application in Polymer Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| ATR Crystals (Diamond, ZnSe) | Enables direct measurement of solid and liquid samples with minimal preparation by facilitating attenuated total reflection. | Analyzing the surface chemistry of a weathered plastic film without dissolution or pressing [37] [40]. |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆) | Provides a magnetically consistent environment for NMR analysis without adding significant interfering signal. | Dissolving a polymer extract to identify low-molecular-weight degradants or additives via 1D and 2D NMR [41]. |

| KBr (Potassium Bromide) | An IR-transparent material used as a bearer for making pellets of powdered solid samples for transmission FTIR. | Creating a transparent disc from a ground plastic sample for high-quality transmission FTIR analysis [40]. |

| Stabilizers & Antioxidants | Chemical additives that inhibit or slow down oxidation and other degradation processes in polymers. | Used in control experiments to compare the degradation rate of stabilized vs. unstabilized polymer samples [3]. |

| Spectral Libraries | Databases of reference spectra for known compounds, used for identification of unknown materials. | Comparing the FTIR spectrum of an unknown contaminant in a polymer product against a library to identify it [43]. |

Gel Permeation or Size-Exclusion Chromatography (GPC/SEC) is the primary method for determining the molar mass averages and molar mass distribution of polymers. When investigating polymer chain degradation, a shift in molecular weight provides a direct and quantifiable measure of chain scission or other structural changes. For researchers and scientists tracking these molecular weight shifts, systematic errors and operational issues can compromise data accuracy. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to resolve specific experimental challenges, ensuring your GPC/SEC data reliably reflects true polymer degradation.

Troubleshooting Guides: Addressing Common GPC/SEC Problems

Pressure Problems