Self-Healing Polyurethanes: Synthesis, Mechanisms, and Biomedical Applications in Drug Delivery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly advancing field of self-healing polyurethanes, with a specific focus on their synthesis, underlying mechanisms, and transformative potential in biomedical applications and...

Self-Healing Polyurethanes: Synthesis, Mechanisms, and Biomedical Applications in Drug Delivery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly advancing field of self-healing polyurethanes, with a specific focus on their synthesis, underlying mechanisms, and transformative potential in biomedical applications and drug delivery. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational chemistry of dynamic covalent and non-covalent bonds that enable self-repair. The content delves into innovative synthesis strategies, including the use of Diels-Alder reactions, disulfide bonds, and biomimetic designs for creating room-temperature and underwater self-healing systems. It further addresses key challenges in balancing mechanical properties with healing efficiency and critically evaluates the biocompatibility and in vivo performance of these smart materials, offering a forward-looking perspective on their role in precision medicine and minimally invasive medical devices.

The Chemistry of Self-Repair: Understanding Dynamic Bonds in Polyurethanes

Self-healing materials represent a revolutionary class of smart polymers engineered to autonomously repair physical damage, mimicking biological regeneration processes found in nature [1]. These materials are predominantly categorized into two distinct mechanistic approaches: extrinsic and intrinsic healing, each with unique operational principles and characteristics [2] [3]. This classification is fundamental to understanding their application in self-healing polyurethane systems for advanced research and industrial applications.

Extrinsic self-healing relies on pre-embedded healing agents contained within microcapsules, hollow fibers, or vascular networks distributed throughout the polymer matrix [2] [4]. When damage occurs, these containers rupture and release healing agents into the crack plane through capillary action. The released monomer subsequently contacts an embedded catalyst, triggering polymerization that bonds the fracture surfaces together [3] [4]. This approach provides rapid, single-use repair capabilities suitable for emergency damage mitigation.

Intrinsic self-healing utilizes inherent reversible chemistry within the polymer backbone itself, employing dynamic covalent bonds or supramolecular interactions that can undergo reversible dissociation and reassociation [2] [5]. These reversible networks enable multiple healing cycles at the same damage site through stimulus-responsive bond reformation, offering theoretically unlimited repair capacity but often requiring external triggers such as heat, light, or moisture [3] [5].

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Extrinsic and Intrinsic Self-Healing Mechanisms

| Characteristic | Extrinsic Self-Healing | Intrinsic Self-Healing |

|---|---|---|

| Healing Agent | Separate, encapsulated healing agents | Inherent reversible bonds in polymer matrix |

| Healing Cycles | Single-use at specific damage site | Multiple cycles at same location |

| Healing Speed | Rapid repair (minutes) | Variable (hours to days) |

| External Stimulus | Often autonomous | Frequently requires heat, light, or moisture |

| Mechanical Impact | May compromise original properties | Tunable mechanical properties |

| Typical Applications | Structural composites, protective coatings | Flexible electronics, biomedical devices |

Quantitative Comparison of Healing Performance

The effectiveness of self-healing systems is quantitatively evaluated through parameters including healing efficiency, mechanical property recovery, and cycling capability. Recent advancements in both extrinsic and intrinsic systems have demonstrated significant improvements in these performance metrics.

For extrinsic systems, healing efficiency is constrained by the quantity and distribution of encapsulated healing agents. The pioneering work by White et al. demonstrated approximately 75% recovery of fracture toughness using dicyclopentadiene (DCPD) microcapsules and Grubbs' catalyst [3]. Vascular-based systems extend this capability through interconnected networks that allow larger healing volumes, with An et al. reporting complete corrosion resistance restoration in scratched coatings containing self-healing core-shell nanofibers [3].

Intrinsic systems exhibit wider performance variation based on their specific dynamic chemistry. Disulfide-based systems have achieved 75-83% healing efficiency at room temperature within 2-48 hours, while diselenide-bonded waterborne polyurethanes under visible light irradiation demonstrated over 90% healing efficiency [5]. Vanillin-derived polyurethanes with dynamic imine bonds showcased complete scratch healing within 30 minutes at 80°C while tripling tensile strength compared to conventional waterborne polyurethane (12.8 MPa versus 4.3 MPa) [6].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Self-Healing Polyurethane Systems

| System Type | Healing Chemistry | Healing Conditions | Healing Efficiency | Mechanical Properties | Cycling Capability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extrinsic (Microcapsule) | DCPD + Grubbs' catalyst | Room temperature, autonomous | ~75% fracture recovery | Minimal property compromise | Single use per location |

| Extrinsic (Vascular) | PDMS crosslinking | Room temperature, autonomous | Complete barrier restoration | Maintains corrosion protection | Limited by agent reservoir |

| Intrinsic (Disulfide) | Aromatic disulfide metathesis | 25°C, 2-48 hours | 75-83% tensile strength | 6.8-11.0 MPa tensile strength | Multiple cycles demonstrated |

| Intrinsic (Diselenide) | Diselenide exchange | Visible light, 48 hours | >90% tensile strength | 16.31 MPa tensile strength | Multiple cycles demonstrated |

| Intrinsic (Imine bonds) | Schiff base exchange | 80°C, 30 minutes | Complete visual healing | 12.8 MPa tensile strength | Multiple cycles possible |

Experimental Protocols for Self-Healing Polyurethane Synthesis

Protocol: Microencapsulated Self-Healing Polyurethane System

This protocol outlines the procedure for preparing an extrinsic self-healing polyurethane composite based on the methodology established by White et al. [3] [4].

Materials Required:

- Polyurethane matrix components (polyol, diisocyanate, catalyst)

- Urea-formaldehyde microcapsules (50-200 μm) containing dicyclopentadiene (DCPD)

- Grubbs' catalyst (ruthenium-based)

Procedure:

- Microcapsule Preparation: Prepare urea-formaldehyde microcapsules containing DCPD using in-situ polymerization. Confirm capsule size distribution (50-200 μm) and shell integrity via optical microscopy.

- Catalyst Dispersion: Uniformly disperse 2.5-5.0 wt% Grubbs' catalyst powder within the polyol component using mechanical stirring at 500 rpm for 30 minutes under nitrogen atmosphere.

- Composite Fabrication:

- Incorporate 10-20 wt% DCPD microcapsules into the catalyzed polyol mixture with gentle stirring (200 rpm) to prevent capsule rupture.

- Add stoichiometric equivalent of diisocyanate (e.g., isophorone diisocyanate) and mix thoroughly.

- Degas the mixture under vacuum (0.1 atm) for 10 minutes to remove entrapped air.

- Cast into molds and cure at 80°C for 12 hours followed by post-curing at 110°C for 4 hours.

- Quality Control: Verify microcapsule distribution and integrity in the final composite using scanning electron microscopy of cross-sections.

Healing Assessment:

- Introduce controlled cracks using razor blade scoring or fracture toughness testing.

- Monitor autonomous healing at room temperature over 24-48 hours.

- Quantify healing efficiency via fracture toughness recovery: η = (KIC,healed / KIC,virgin) × 100%

Protocol: Vanillin-Derived Intrinsic Self-Healing Polyurethane

This protocol describes the synthesis of bio-based intrinsic self-healing waterborne polyurethane incorporating dynamic imine bonds, adapted from recent literature [6].

Materials Required:

- Isophorone diisocyanate (IPDI, 99%)

- Polytetrahydrofuran (PTHF, Mn = 1000 g/mol)

- Vanillin (98%) and ethylenediamine (99%) for vanillin diol synthesis

- Dimethylolpropionic acid (DMPA, 98%)

- Dibutyltin dilaurate (DBTDL, 98%) as catalyst

- Triethylamine (TEA, 98%) for neutralization

Procedure:

- Vanillin Diol (VAN-OH) Synthesis:

- Dissolve 5 g (32 mmol) vanillin in 5 mL ethanol in a 100 mL three-neck flask equipped with reflux condenser.

- Add 1 g (16 mmol) ethylenediamine dropwise under magnetic stirring, observing immediate yellow precipitate formation.

- Heat to 55°C and reflux for 8 hours with continuous stirring.

- Filter the precipitate, wash with ethanol/water, and dry under vacuum at 70°C for 24 hours.

- Characterize product by FTIR and NMR to confirm imine bond formation.

Polyurethane Prepolymer Synthesis:

- Charge 15 g (15.9 mmol) PTHF and 6 g (27 mmol) IPDI into a 100 mL reactor.

- Add 20 μL DBTDL catalyst and heat to 70°C under nitrogen atmosphere with mechanical stirring.

- React for 4 hours until theoretical NCO content is reached (determined by dibutylamine titration).

Chain Extension and Dispersion:

- Add 1 g (7.5 mmol) DMPA and 1.2 g (3.6 mmol) VAN-OH to the prepolymer.

- Continue reaction at 80°C for 4 hours with monitoring of NCO content.

- Cool to 40°C and gradually add aqueous triethylamine solution (neutralizing agent) with high-shear mixing (1000 rpm) for 1 hour.

- Obtain milky white dispersion with approximately 30-35% solid content.

Film Formation and Characterization:

- Cast dispersion onto glass plates and dry at room temperature for 48 hours followed by 60°C for 12 hours.

- Verify imine bond presence by FTIR (C=N stretch at 1640-1660 cm⁻¹).

- Assess self-healing by creating controlled scratches with razor blade and heating at 80°C for 30 minutes.

Mechanism Visualization and Pathways

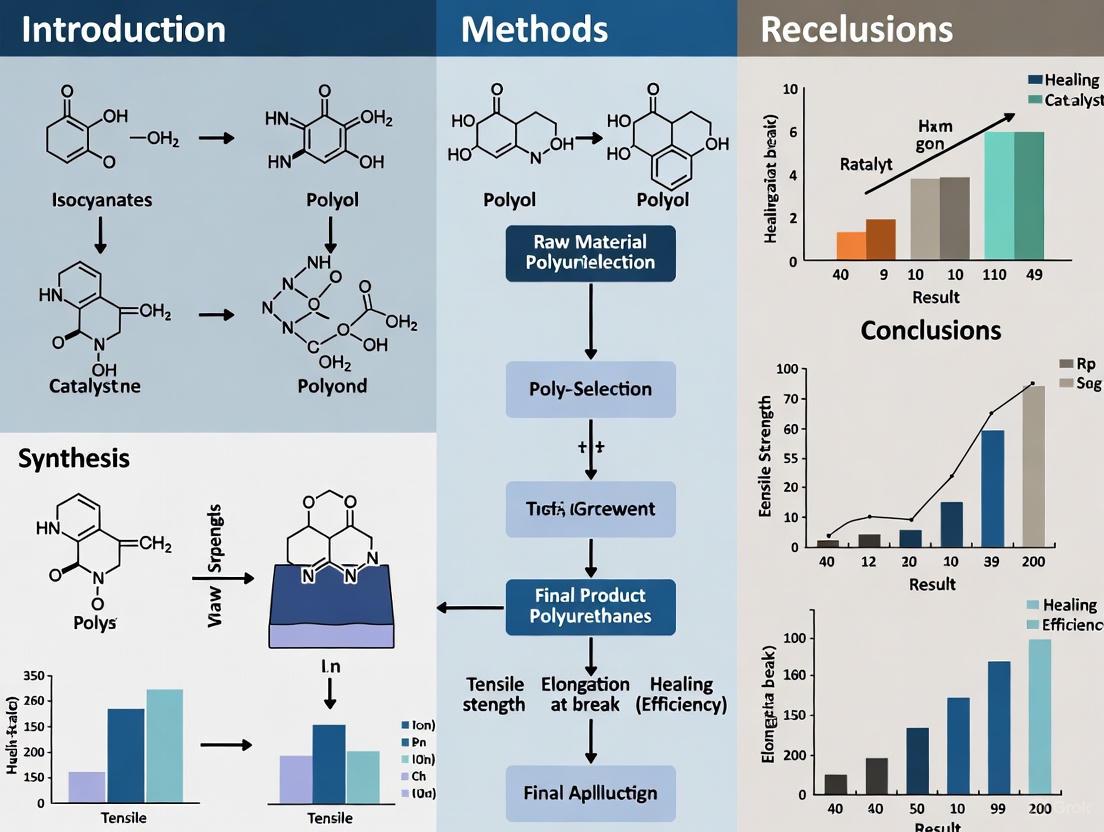

The following diagrams illustrate the fundamental operational principles of extrinsic and intrinsic self-healing mechanisms, providing visual representation of the damage repair processes.

Diagram 1: Comparative Healing Process Flows. Extrinsic healing relies on sequential release and polymerization of encapsulated agents, while intrinsic healing utilizes stimulus-triggered reversible bond reformation.

Diagram 2: Dynamic Bond Classification in Intrinsic Self-Healing. Dynamic covalent bonds provide stronger mechanical properties, while non-covalent interactions enable faster healing responses at milder conditions.

Research Reagent Solutions for Self-Healing Polyurethanes

The following table details essential research reagents and their specific functions in developing self-healing polyurethane systems, providing a practical resource for experimental design.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Self-Healing Polyurethane Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Self-Healing System | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Bond Monomers | Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl) disulfide, Diaminophenyl disulfide, Vanillin-derived diols | Incorporate reversible covalent bonds (disulfide, imine) into polymer backbone | Aromatic disulfides enable room-temperature healing; vanillin provides bio-based alternative |

| Healing Agents | Dicyclopentadiene (DCPD), Vinyl-terminated PDMS, Epoxidized vegetable oils | Polymerizable monomers for extrinsic healing systems | DCPD requires Grubbs' catalyst; vegetable oils offer sustainable alternatives |

| Catalysts | Grubbs' catalyst (ruthenium-based), Dibutyltin dilaurate (DBTDL) | Initiate polymerization of healing agents or catalyze dynamic bond exchange | Grubbs' catalyst sensitive to oxygen/water; DBTDL common for urethane formation |

| Polyisocyanates | Isophorone diisocyanate (IPDI), Hexamethylene diisocyanate (HDI), Toluene diisocyanate (TDI) | Form urethane linkages; determine mechanical properties and weathering resistance | Aliphatic IPDI/HDI for UV resistance; aromatic TDI for mechanical performance |

| Polyols | Polytetrahydrofuran (PTHF), Polypropylene glycol (PPG), Polyester polyols | constitute soft segments; influence flexibility, crystallinity, and phase separation | Molecular weight and functionality affect mechanical properties and healing efficiency |

| Chain Extenders | Dimethylolpropionic acid (DMPA), Butanediol (BDO), Ethylenediamine | Control hard segment formation; DMPA enables water dispersibility | Affect microphase separation crucial for balancing mechanical and healing properties |

Application Context in Polyurethane Research

The selection between intrinsic and extrinsic self-healing mechanisms carries significant implications for specific application domains in advanced polyurethane materials. Understanding these application-specific considerations is essential for targeted material design.

Flexible Electronics and Wearable Sensors predominantly utilize intrinsic self-healing polyurethanes due to their multiple repair cycles and tunable mechanical properties [4] [5]. These systems employ dynamic disulfide, diselenide, or imine bonds that enable repeated healing of microcracks formed during device flexing. Recent advances demonstrate room-temperature healing under visible light irradiation using diselenide chemistry, achieving over 90% healing efficiency while maintaining electrical conductivity [5]. For biomedical applications like electronic skins, waterborne polyurethane systems with disulfide bonds provide biocompatibility while achieving 83% healing efficiency at physiological temperatures [5].

Protective Coatings and Structural Composites often employ extrinsic systems for rapid, autonomous damage response [3] [4]. Microencapsulated DCPD systems provide immediate corrosion protection when coatings are scratched, particularly valuable for automotive and aerospace applications where prompt repair is critical. Vascular networks extending healing agent supply have demonstrated complete restoration of barrier properties in corrosion tests on steel substrates [3]. The single-use limitation is acceptable in these applications where catastrophic failure prevention is the primary objective.

Sustainable Material Systems increasingly leverage bio-based intrinsic healing approaches combining renewable feedstocks with dynamic covalent chemistry [6] [7]. Vanillin-derived polyurethanes with imine bonds represent emerging sustainable alternatives that simultaneously address mechanical performance, healing capability, and environmental impact. These systems align with circular economy principles through their reparability and bio-based composition, finding applications in eco-friendly coatings, adhesives, and packaging materials [6].

The ongoing development of fourth-generation self-healing materials combines intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms within hybrid systems, overcoming individual limitations while synergistically enhancing performance [8] [9]. These advanced materials demonstrate exceptional potential for high-performance applications requiring both mechanical robustness and repeated reparability, such as in energy storage devices, biomedical implants, and advanced sensors [10] [7].

Reversible covalent bonds are dynamic linkages that can undergo controlled breaking and reformation under specific conditions. This article details the application notes and experimental protocols for three pivotal reversible bonds—Diels-Alder adducts, disulfide (S–S), and diselenide (Se–Se) bridges—within the context of synthesizing advanced self-healing polyurethanes (PUs). These materials mimic biological repair mechanisms, offering enhanced longevity and sustainability for applications ranging from flexible electronics to targeted drug delivery [2] [4]. The dynamic nature of these bonds facilitates stimuli-responsive behavior, enabling materials that autonomously repair damage and restore mechanical integrity upon exposure to triggers such as heat, light, or specific redox environments [4] [11].

The following sections provide a comparative analysis of these bonds, detailed protocols for their incorporation into polyurethane networks, and visual workflows to guide researchers in their experimental design.

Comparative Bond Analysis and Quantitative Data

The selection of an appropriate dynamic bond is crucial for tailoring the properties of self-healing materials. The table below summarizes key quantitative data and characteristics for the Diels-Alder reaction, disulfide, and diselenide bonds.

Table 1: Comparative quantitative data for Diels-Alder, disulfide, and diselenide bonds.

| Property | Diels-Alder Adduct | Disulfide Bond (S–S) | Diselenide Bond (Se–Se) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Dissociation Energy | Varies with adduct | 60 kcal/mol (251 kJ/mol) [12] | 172 kJ/mol [13] |

| Bond Length | N/A | ≈ 2.03 Å [12] | N/A |

| Stimuli-Responsive Trigger | Heat (Retro-Diels-Alder) [14] | Redox (GSH, ~2-10 mM intracellular) [13] [15] | Redox (GSH & H₂O₂, ~50-100 μM in cancer tissue) [13] [15] |

| Key Advantage in Self-Healing | Thermally reversible, catalyst-free "click" chemistry [16] | High sensitivity to reducing environments (e.g., cytosol) [4] | Dual responsiveness to both oxidative (H₂O₂) and reductive (GSH) stimuli [15] |

| Typical Self-Healing Efficiency | Governed by kinetic vs. thermodynamic control (endo/exo ratios) [14] | Efficient under physiological conditions; dependent on GSH concentration [13] | Higher redox sensitivity compared to disulfide; effective even at low GSH [13] |

| Primary Application Context | Intrinsic self-healing polymers & bioconjugation [2] [16] | Redox-responsive drug delivery & self-healing materials [12] [4] | Next-generation, highly sensitive anticancer drug delivery systems [13] [15] |

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

The Diels-Alder Reaction in Polymer Cross-linking

The Diels-Alder (DA) reaction is a [4+2] cycloaddition between a conjugated diene and a dienophile. Its reversible nature, via the retro-Diels-Alder (rDA) reaction upon heating, makes it ideal for creating thermally mending polymers [14] [17]. The reaction is stereospecific, often favoring the endo adduct as the kinetic product at lower temperatures, while thermodynamic exo products can form at higher temperatures when the reaction is reversible [14] [17].

Protocol 3.1.1: Fabrication of Diels-Alder Cross-linked Polyurethane Micelles for Drug Delivery

This protocol outlines the synthesis of core-cross-linked (CCL) micelles using the Diels-Alder reaction between furan and maleimide groups [13].

Materials:

- Polymer: Poly(ethylene oxide)₂ₖ-b-poly(furfuryl methacrylate)₁.₅ₖ (PEO₂ₖ-b-PFMA₁.₅ₖ).

- Cross-linker: Bis-maleimide cross-linker (e.g., 1,6-bis(maleimide)hexane, BisMH).

- Drug: Doxorubicin (DOX).

- Solvent: Acetonitrile or water.

Methodology:

- Step 1: Drug Loading. Dissolve the PEO₂ₖ-b-PFMA₁.₅ₖ copolymer and DOX in an organic solvent. The drug is incorporated into the hydrophobic PFMA core via hydrophobic interactions.

- Step 2: Micelle Formation. Add the solution dropwise to deionized water under vigorous stirring to induce the self-assembly of polymeric micelles. Allow the organic solvent to evaporate.

- Step 3: Core Cross-linking. Add the bis-maleimide cross-linker (BisMH) to the micellar solution. Heat the mixture at 40°C for 48 hours to facilitate the Diels-Alder cycloaddition between the furan groups on the PFMA block and the maleimide groups of the cross-linker, forming a cross-linked micelle core [13].

- Step 4: Purification. Purify the resulting CCL micelles via dialysis or filtration to remove unreacted cross-linker and unencapsulated drug.

Key Considerations:

- The DA reaction accelerates in water due to hydrophobic packing and hydrogen bonding [17] [13].

- The cross-linking density can be tuned by varying the ratio of the bis-maleimide cross-linker to the furan groups in the polymer.

- Drug release can be triggered by the rDA reaction at elevated temperatures or by hydrolysis at acidic pH (e.g., pH 5.0 in tumor microenvironments) [13].

Disulfide Chemistry for Redox-Responsive Materials

Disulfide bonds are a cornerstone of dynamic chemistry, characterized by their reversibility under redox conditions. The bond is notably weaker than C–C and C–H bonds, making it the "weak link" in many systems and highly susceptible to cleavage by nucleophiles, especially thiolates [12]. The concentration of glutathione (GSH) in tumor cells can be 100–1000 times higher than in extracellular fluids, providing a specific trigger for drug release [13].

Protocol 3.2.1: Incorporating Disulfide Bonds into Waterborne Polyurethane (WPU) for Room-Temperature Self-Healing

This protocol describes the synthesis of a WPU elastomer capable of self-healing at room temperature via disulfide metathesis [4].

Materials:

- Disulfide Monomer: Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl) disulfide or similar.

- Polyol: Poly(tetramethylene ether) glycol (PTMEG).

- Diisocyanate: Isophorone diisocyanate (IPDI).

- Chain Extender: 1,4-Butanediol (BDO).

- Catalyst: Dibutyltin dilaurate (DBTDL).

Methodology:

- Step 1: Pre-polymer Synthesis. Under a nitrogen atmosphere, react PTMEG with a stoichiometric excess of IPDI in a dry flask at 80°C for 2–3 hours in the presence of a few drops of DBTDL catalyst to form an isocyanate-terminated pre-polymer.

- Step 2: Disulfide Incorporation. Lower the temperature to 60°C. Add the disulfide diol monomer (e.g., bis(4-hydroxyphenyl) disulfide) to the pre-polymer mixture and allow it to react for 1 hour. This incorporates dynamic disulfide bonds into the polymer backbone.

- Step 3: Chain Extension. Add the chain extender (BDO) to the reaction mixture and stir for an additional hour to complete the polymerization and achieve the target molecular weight.

- Step 4: Emulsification. Disperse the resulting polyurethane in water with high-speed stirring to form a stable WPU emulsion.

Key Considerations:

- The disulfide metathesis exchange reaction is favored at room temperature and is catalyzed by basic conditions or light [4].

- The mechanical properties of the final film (e.g., tensile strength, elasticity) must be balanced with the self-healing efficiency, which is a common challenge in intrinsic self-healing systems [11].

Diselenide Bonds for Dual Redox Responsiveness

Diselenide bonds share similarities with disulfide bonds but exhibit superior redox sensitivity due to a lower bond dissociation energy (172 kJ/mol for Se–Se vs. 268 kJ/mol for S–S) [13]. This allows them to be cleaved by both reductive (GSH) and mild oxidative (H₂O₂) stimuli, which are abundant in tumor microenvironments, making them exceptionally suitable for advanced drug delivery systems [15].

Protocol 3.3.1: Synthesis of Diselenide Core-Cross-Linked Micelles and Redox-Triggered Drug Release

This protocol details the creation of micelles cross-linked with diselenide bonds, offering dual redox responsiveness [13].

Materials:

- Polymer: PEO₂ₖ-b-PFMA₁.₅ₖ.

- Cross-linker: Diselenobis(maleimido)ethane (DseME).

- Triggering Agents: Glutathione (GSH, 10 mM) and/or Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂, 100 mM).

Methodology:

- Steps 1-3: Follow Protocol 3.1.1 for drug loading, micelle formation, and core cross-linking, but substitute the bis-maleimide cross-linker (BisMH) with the diselenide-based cross-linker DseME.

- Step 4: Redox-Triggered De-Cross-Linking. To induce drug release, treat the diselenide CCL micelles with either 10 mM GSH (reductive cleavage) or 100 mM H₂O₂ (oxidative cleavage). The diselenide bond will break, de-cross-linking the micelle core and accelerating the release of the encapsulated drug (e.g., DOX) [13].

- Step 5: Analysis. Monitor the changes in micelle size and polydispersity index (PDI) using dynamic light scattering (DLS), and quantify drug release using UV-Vis spectroscopy.

Key Considerations:

- Diselenide-based micelles demonstrate more significant changes in size and PDI in response to redox environments compared to disulfide analogs, indicating higher sensitivity [13].

- These systems show lower drug release at physiological pH (7.4) but enhanced release at tumor-like acidic pH (5.0) and in the presence of GSH/H₂O₂, providing multiple layers of targeting [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key reagents and materials for working with reversible covalent bonds in self-healing materials and drug delivery.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Furfuryl Methacrylate (FMA) | Provides furan-protected diene monomers for Diels-Alder polymer synthesis. | Used in the backbone of PEO₂ₖ-b-PFMA₁.₅ₖ for subsequent cross-linking [13]. |

| Bis-Maleimide Cross-linkers | Dienophile for Diels-Alder cross-linking; forms reversible bridges between polymer chains. | 1,6-bis(maleimide)hexane (BisMH) cross-links PFMA cores of micelles [13]. |

| Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl) disulfide | Disulfide-containing diol monomer for incorporating dynamic S–S bonds into PU backbone. | A monomer for synthesizing room-temperature self-healing waterborne polyurethanes [4]. |

| Dithiobis(maleimido)ethane (DTME) | A cross-linker containing a disulfide bond, used for redox-responsive cross-linking. | Used to form disulfide core-cross-linked micelles [13]. |

| Diselenobis(maleimido)ethane (DseME) | A cross-linker containing a diselenide bond, enables dual (GSH/H₂O₂) redox responsiveness. | Used to form diselenide core-cross-linked micelles with higher sensitivity than S–S [13]. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Strong reducing agent; cleaves disulfide and diselenide bonds in biochemical contexts. | Used in excess to reduce and cleave disulfide bonds in laboratory experiments [12]. |

| Glutathione (GSH) | Natural reducing tripeptide; mimics intracellular reductive environment to trigger S–S or Se–Se cleavage. | Applied at 10 mM concentration to induce redox-responsive de-cross-linking in micelles [13]. |

Visual Experimental Workflows

Workflow for Self-Healing Polyurethane Synthesis

The diagram below illustrates the strategic decision-making process for selecting and implementing reversible bonds in self-healing polyurethane synthesis.

Mechanism of Redox-Responsive Bond Cleavage

This diagram details the mechanistic pathways for the cleavage of disulfide and diselenide bonds by glutathione (GSH) and hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂).

Supramolecular chemistry, defined as 'chemistry beyond the molecule,' focuses on molecular associations governed by non-covalent interactions with partial covalent character [18]. In the specific context of self-healing polyurethanes (PUs), these reversible interactions provide the foundational mechanism enabling autonomous damage repair, restoration of mechanical strength, and structural adaptability without external intervention [4]. The dynamic nature of hydrogen bonds and metal-ion coordination bonds allows for the development of intelligent materials capable of extending service life, reducing waste, and enabling more sustainable material lifecycles [4] [19].

While extrinsic self-healing systems rely on pre-embedded healing agents within microcapsules or hollow fibers, intrinsic self-healing—the focus of this protocol—leverages reversible bonds within the polymer matrix itself [4] [5]. This approach offers significant advantages, including multiple healing cycles at the same damage site without depleting a healing agent [19]. The integration of both hydrogen bonding and metal-ion coordination creates a synergistic system where hydrogen bonds provide moderate mechanical strength and the metal-coordination bonds contribute robust yet dynamic cross-linking, enabling high mechanical performance and efficient room-temperature self-healing—a combination that is often challenging to achieve [19].

Quantitative Comparison of Dynamic Bond Systems

The table below summarizes key performance metrics for various dynamic bond systems used in self-healing polyurethanes, highlighting the superior mechanical and healing performance of hybrid systems.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Dynamic Bonds in Room-Temperature Self-Healing Polyurethanes

| Dynamic Bond Type | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Toughness (MJ m⁻³) | Healing Efficiency (%) | Healing Conditions | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dual H-bond + Metal-Lysine Coordination [19] | 17.2 - 43.0 | 45.8 - 121.5 | > 92 (Toughness) | 24 h @ 25 °C | Excellent integrated properties, room-temperature healing, recyclable |

| Aromatic Disulfide Bonds [5] | ~6.8 | ~26.9 | > 75 | 2 h @ 25 °C | Room-temperature metathesis without stimulus; yellow appearance |

| Diselenide Bonds [5] | ~16.3 | ~68.9 | > 90 | 48 h under visible light | Responsive to visible light; lower bond energy than disulfide |

| Metal-Ligand (e.g., Fe²⁺-PY) [5] | ~4.6 | - | ~96 (Tensile) | 48 h @ 25 °C | Room-temperature healing; often exhibits lower mechanical strength |

Experimental Protocol: Synthesis of Room-Temperature Self-Healable Polyurethane via Metal-Lysine Coordination

This protocol details the synthesis of a self-healing polyurethane elastomer by integrating dual dynamic units of hydrogen bonding and metal-lysine coordination bonds, adapting the methodology from recent pioneering work [19].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Self-Healing Polyurethane Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Explanation | Example/CAS |

|---|---|---|

| Isophorone Diisocyanate (IPDI) | Aliphatic diisocyanate monomer forming the hard segment. Provides steric asymmetry that promotes efficient dynamic exchange. | 4098-71-9 |

| Polycaprolactone Diol (PCL) | Macropolyol soft segment, determining flexibility and crystallization behavior. | Mn = 2,000 Da |

| l-Lysine Monohydrochloride | Natural amino acid precursor for synthesizing the metal-coordination complex ligand. | 657-27-2 |

| Zinc Carbonate Basic | Source of Zn²⁺ ions for forming dynamic metal-coordination bonds. | istory |

| 1,4-Butanediol (BDO) | Conventional chain extender, contributing to urethane hydrogen bonding network. | 110-63-4 |

| Dibutyltin Dilaurate (DBTDL) | Catalyst for the urethane polymerization (isocyanate-alcohol reaction). | 77-58-7 |

| Anhydrous N,N-Dimethylacetamide (DMAc) | Solvent for polymerization, requiring anhydrous conditions to prevent isocyanate side reactions. | 127-19-5 |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Synthesis of Metal-Lysine Coordination Complexes (e.g., Zn(Lys)₂)

- Dissolve l-lysine monohydrochloride (10.0 g, 54.8 mmol) in 200 mL of deionized water in a 500 mL three-necked round-bottom flask.

- Slowly add a stoichiometric amount of zinc carbonate basic (calculated based on Zn²⁺ content) with vigorous stirring. A mild effervescence (CO₂ release) will be observed.

- Heat the reaction mixture to 60°C and maintain for 6 hours under a nitrogen atmosphere.

- Cool the mixture to room temperature and filter to remove any unreacted solids.

- Precipitate the product by slowly adding the filtered solution into a large excess of acetone (approximately 1 L) under stirring.

- Collect the resulting white solid by vacuum filtration and wash thoroughly with acetone. Dry the product under vacuum at 50°C for 24 hours. Characterize the complex via FTIR and elemental analysis [19].

Step 2: Prepolymer Formation

- In a dry 500 mL reactor equipped with a mechanical stirrer, thermometer, and nitrogen inlet, charge PCL diol (0.05 mol) and IPDI (0.10 mol).

- Add 2-3 drops of DBTDL catalyst.

- Under a constant nitrogen purge, gradually heat the mixture to 85°C and maintain with stirring for 2-3 hours.

- Monitor the reaction by the disappearance of the -OH peak using FTIR or by standard di-n-butylamine back-titration method to determine the -NCO content until it reaches the theoretical value for the prepolymer.

Step 3: Chain Extension and Incorporation of Dynamic Bonds

- Cool the prepolymer to 70°C.

- Prepare a chain extension mixture containing a molar ratio of 1,3-BAC and the synthesized Zn(Lys)₂ complex. For example, for the PU-Zn-20 system, 20 mol% of the chain extender is Zn(Lys)₂, and 80 mol% is 1,3-BAC [19].

- Dissolve this mixture in a minimum amount of anhydrous DMAc and add it dropwise to the prepolymer over 15 minutes.

- Maintain the reaction at 70°C for an additional 3-4 hours until the -NCO peak in the FTIR spectrum (around 2270 cm⁻¹) is no longer detectable.

Step 4: Film Casting and Post-Processing

- Pour the resulting viscous polymer solution onto a clean, leveled Teflon plate.

- Use a doctor blade to achieve a uniform thickness (e.g., 0.5-1.0 mm).

- Place the cast film in a vacuum oven and gradually increase the temperature to 60°C. Cure under vacuum for 24 hours to remove all residual solvent.

- Carefully peel the resulting polyurethane film from the plate for testing.

Characterization and Validation

- Mechanical Testing: Perform tensile tests (ASTM D412) on dog-bone samples to determine stress-strain curves, from which tensile strength, elongation at break, and toughness are calculated.

- Self-Healing Efficiency Assessment:

- Cut a dumbbell-shaped sample completely in half with a sharp blade.

- Gently bring the two cut surfaces into contact and leave them at room temperature (25°C) for 24 hours without any external pressure or stimulus.

- Perform tensile tests on the healed sample.

- Calculate the healing efficiency (η) as: η = (Toughness of healed sample / Toughness of original sample) × 100% [19].

- Structural Analysis: Use FTIR to confirm the formation of urethane linkages and the presence of coordination bonds. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) can be used to study thermal transitions and microphase separation.

Interaction Mechanisms and Material Workflow

The self-healing functionality arises from the synergistic operation of multiple dynamic interactions. The following diagram visualizes the hierarchical structure and self-healing mechanism of the synthesized polyurethane.

Diagram 1: Self-Healing Mechanism of Metal-Coordinated Polyurethane. The material's structure and function operate across multiple scales. (A) At the molecular level, dynamic hydrogen bonds (red) and metal-ligand coordination bonds (green) exist within the polymer network. (B) These interactions drive nanoscale self-assembly into a microphase-separated structure where reinforced hard domains are dispersed in a soft matrix. (C) Upon damage, these dynamic bonds rupture preferentially, allowing surfaces to reconnect. Over time, the bonds reassociate across the crack interface, leading to macroscopic healing [19] [5].

Application Notes in Flexible Electronics and Drug Delivery

The unique properties of these supramolecular PUs make them ideal for advanced applications. In flexible electronics, they serve as substrates for healable electrodes and sensors, mitigating mechanical damage during operation and extending device lifetime [4]. Their dynamic nature allows them to be reprocessed and recycled, supporting a more sustainable electronics lifecycle [19].

Furthermore, supramolecular polymers are revolutionizing precision medicine. The same principles of reversible, stimuli-responsive assembly are leveraged to create nanocarriers for targeted drug delivery [20] [21]. These systems can be engineered to release therapeutic agents in response to specific physiological cues like pH gradients or enzyme activity at disease sites, improving efficacy and reducing off-target effects [18] [20]. Cyclodextrin-based complexes, for instance, are widely used to improve drug solubility and stability [18].

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Table 3: Common Synthesis Challenges and Solutions

| Challenge | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Mechanical Strength | Insufficient microphase separation; low crosslink density. | Optimize the hard-to-soft segment ratio; ensure complete reaction during chain extension. |

| Low Healing Efficiency | Restricted chain mobility; dynamic bonds are too stable. | Adjust the type and molar percentage (e.g., PU-Zn-20) of the metal-ligand complex; ensure good contact between cut surfaces. |

| Polymer Discoloration | Oxidation of metal ions or aromatic moieties. | Use aliphatic isocyanates (e.g., IPDI); conduct synthesis under inert atmosphere (N₂). |

| Incomplete Solvent Removal | Low vacuum or temperature during curing. | Extend curing time under high vacuum at 60-70°C. |

The Microphase-Separated Structure of Polyurethanes and its Role in Self-Healing

Polyurethanes (PUs) are segmented block copolymers that have become a cornerstone of modern polymer science, particularly in the field of smart materials with self-healing capabilities. Their unique architectural motif, known as the microphase-separated structure, is fundamentally responsible for a wide spectrum of mechanical properties and the ability to recover from damage. This application note delineates the integral role of microphase separation in enabling self-healing functionality within polyurethane materials. Framed within a broader thesis on self-healing PU synthesis, this document provides researchers and scientists in drug development and materials science with a detailed examination of the underlying mechanisms, quantitative structure-property relationships, and practical experimental protocols. The insights herein are crucial for designing next-generation biomedical devices, drug delivery systems, and other advanced applications where material longevity and autonomic repair are paramount.

Structural Fundamentals of Polyurethane Microphase Separation

The molecular architecture of polyurethanes is characterized by a segmented block copolymer structure, comprising alternating hard segments (HS) and soft segments (SS) [22] [23]. The hard segments are formed from the reaction of a diisocyanate with a low molecular weight chain extender, such as a diol or diamine. The soft segments are derived from long-chain polymeric diols, such as polyether or polyester polyols [23] [24]. This chemical dissimilarity between the rigid, polar hard segments and the flexible, non-polar soft segments leads to a thermodynamic incompatibility, driving their organization into a microphase-separated morphology [23] [24].

In this morphology, the hard segments aggregate into discrete, glassy or semi-crystalline domains that act as physical cross-links and reinforcing fillers, dispersed within a continuous matrix of soft segments [5] [23]. This structure is the genesis of the exemplary mechanical properties of PUs, combining the high elasticity of the soft phase with the strength and toughness of the hard domains. The degree and perfection of microphase separation are not fixed; they are exquisitely tunable parameters. They are influenced by the chemical nature of the monomers (e.g., aliphatic vs. aromatic isocyanates, the molecular weight of the polyol), the ratio of hard to soft segments, and the synthesis processing conditions [22] [24]. This tunability directly governs critical properties, including mechanical strength, elasticity, biodegradation rate, and, as explored in the following section, the capacity for self-healing.

The Bridge to Self-Healing: Mechanisms and Microphase Synergy

Self-healing polyurethanes are classified into two principal categories based on their repair mechanism: extrinsic and intrinsic. The microphase-separated structure plays a distinct and critical role in both.

Extrinsic Self-Healing

Extrinsic self-healing relies on embedded healing agents that are released upon damage. This approach typically involves microcapsules or hollow fibers containing a liquid healing agent (e.g., dicyclopentadiene, DCPD) and a catalyst dispersed within the PU matrix [2] [4] [25]. When a crack propagates through the material, it ruptures these containers, releasing the healing agent into the crack plane. The agent then polymerizes upon contact with the embedded catalyst, effectively bonding the crack faces [4] [25]. In these systems, the microphase-separated structure provides the bulk mechanical integrity and fracture toughness necessary to control crack growth and ensure the containers rupture at the damage site.

Intrinsic Self-Healing

Intrinsic self-healing is a more recent and rapidly advancing field. It does not require a separate healing agent but is instead enabled by reversible chemistry within the polymer network itself [2] [5]. These reversible motifs can be dynamic covalent bonds (e.g., disulfide bonds, imine bonds, Diels-Alder adducts) or reversible non-covalent interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, metal-ligand coordination) [2] [6] [5]. The role of microphase separation is far more profound and direct in intrinsic systems. The hard domains not only provide mechanical strength but can also serve as reversible physical cross-links. Upon damage, the application of a stimulus (such as heat, light, or simply ambient conditions) enables the reversible bonds to break and reform, allowing molecular chains to diffuse across the damage interface and restore mechanical properties [5] [26]. The soft, flexible matrix facilitates the necessary chain mobility for this repair process. This synergy creates a dynamic material that can recover from multiple damage cycles.

Table 1: Key Dynamic Bonds in Intrinsic Self-Healing Polyurethanes and Their Characteristics

| Dynamic Bond Type | Stimulus for Exchange | Typical Healing Conditions | Key Advantages | Limitations/Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aromatic Disulfide [5] | Thermal, Radical | Room Temperature - 2-48 hours [5] | High healing efficiency; can be autonomous | Can cause yellowing; expensive monomers |

| Diselenide [5] | Visible Light | 48 hours under visible light [5] | Responsive to benign visible light; lower bond energy | Complex synthesis of monomers |

| Imine (Schiff Base) [6] | Thermal, pH | 30 minutes at 80°C [6] | Fast kinetics; can be derived from bio-based sources (e.g., vanillin) [6] | Susceptibility to hydrolysis |

| Diels-Alder [27] | Thermal | ~120°C for 30 minutes [27] | High thermal reversibility; well-characterized | Requires relatively high healing temperatures |

| Hydrogen Bonds [5] | Thermal | Room Temperature or mild heating [5] | Highly reversible; abundant in PUs | Generally weaker, leading to lower mechanical strength |

Quantitative Analysis of Structure-Property-Performance Relationships

The performance of self-healing PUs is quantifiably linked to their formulation and resulting microstructure. The following table summarizes data from recent research, illustrating how monomer selection and dynamic bond integration influence mechanical and healing properties.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Representative Self-Healing Polyurethane Systems

| Polyurethane System | Dynamic Bond / Mechanism | Hard Segment Components | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Healing Efficiency / Conditions | Reference Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WPU-VAN-OH [6] | Imine bonds (vanillin-derived) | IPDI, VAN-OH | 12.8 MPa | ~100% (scratch closure) / 30 min at 80°C [6] | Protective coatings, adhesives |

| MPUE-SS [26] | Disulfide bonds (HEDS) | MDI, HEDS/BDO | 40 MPa | >95% (mechanical recovery) / 24 hours at RT [26] | Robust, transparent elastomers |

| IP-SS (Kim et al.) [5] | Aromatic disulfide | IPDI, Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl) disulfide | 6.8 MPa | >75% / 2 hours at 25°C [5] | Flexible electronics |

| DSe-WPU-FSi [5] | Diselenide bonds | IPDI, Di(1-hydroxyethylene) diselenide | 16.31 MPa | >90% / 48 hours under visible light [5] | Mechanically robust, flexible coatings |

| DA-based Powder Coating [27] | Diels-Alder reaction | Uretdione cross-linker, DA adduct | N/A | 100% (scratch recovery) / 12.5 min at 120°C [27] | Powder coatings for deep-drawn metals |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This protocol details the synthesis of a bio-based, waterborne polyurethane (WPU) using a vanillin-derived diol (VAN-OH) incorporating dynamic imine bonds, resulting in enhanced mechanical strength and thermal healing capabilities.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Polyol: Polytetrahydrofuran (PTHF, Mn = 1000 g/mol)

- Diisocyanate: Isophorone diisocyanate (IPDI)

- Ionic Center Source: Dimethylolpropionic acid (DMPA)

- Dynamic Chain Extender: Vanillin diol (VAN-OH), synthesized from vanillin and ethylenediamine [6]

- Catalyst: Dibutyltin dilaurate (DBTDL)

- Neutralizing Agent: Triethylamine (TEA)

- Dispersion Medium: Deionized water

Methodology:

- Pre-polymer Synthesis: Charge a dried 100 mL three-necked flask with PTHF (15 g, 15.9 mmol) and IPDI (6 g, 27 mmol). Add DBTDL (20 µL) as a catalyst. Heat the mixture to 70°C under a nitrogen atmosphere with mechanical stirring for 4 hours.

- Chain Extension: To the pre-polymer, add DMPA (1 g, 7.5 mmol) and the VAN-OH chain extender (1.2 g, 3.6 mmol). Increase the temperature to 80°C and continue stirring until the reaction mixture reaches the theoretical NCO value (determined by standard dibutylamine titration).

- Neutralization and Dispersion: Cool the NCO-terminated pre-polymer to 40°C. Gradually add a mixture of distilled water and TEA (to neutralize carboxylic groups from DMPA) via a dropping funnel to the reaction system. Maintain vigorous mechanical stirring for 1 hour to facilitate emulsification.

- Product Isolation: A stable, milky-white dispersion of self-healing WPU (WPU-VAN-OH) is obtained. The dispersion can be cast into a Teflon mold and dried at room temperature or elevated temperature to form a free-standing film for characterization.

This protocol describes the construction of a high-strength, transparent polyurethane elastomer with disulfide bonds, demonstrating excellent room-temperature self-healing and shape-memory properties.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Soft Segments: Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL, Mn = 1000) and a branched polyol (PPG-3, Mn = 300).

- Diisocyanate: 4,4′-diphenylmethane diisocyanate (MDI).

- Mixed Chain Extenders: 1,4-Butanediol (BDO) and Bis(2-hydroxyethyl)disulfide (HEDS).

- Equipment: Planetary vacuum mixer; heated hydraulic press.

Methodology:

- Pre-polymer Preparation: Vacuum dry PCL and PPG-3 in a three-necked flask at 80°C for 2 hours. Add molten MDI to the flask to initiate pre-polymerization. Conduct the reaction with mechanical stirring at 80°C for 2 hours.

- Degassing: Transfer the pre-polymer to a planetary vacuum mixer and degas for 3 minutes at 85°C to remove entrapped air bubbles.

- Chain Extension: Heat the degassed pre-polymer to 90°C. Add the mixed chain extenders (BDO and HEDS) dropwise with vigorous stirring. The chain extension reaction is typically complete within 2 minutes.

- Curing and Post-Processing: Pour the viscous mixture into a preheated mold and immediately compress under 150 bar at 120°C for 40 minutes. Subsequently, cure the film in an oven at 100°C for 20 hours. Finally, allow the film to condition at room temperature for 7 days before testing to ensure complete curing and stabilization of properties.

Visualization of Microphase Separation and Self-Healing Pathways

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the logical relationship between polyurethane synthesis, microphase separation, and the resulting self-healing mechanisms.

Diagram 1: From Monomers to Self-Healing via Microphase Separation

Diagram 2: Intrinsic Self-Healing Mechanism via Dynamic Bond Exchange

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Self-Healing Polyurethane Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Formulation |

|---|---|---|

| Diisocyanates | IPDI, H12MDI (Aliphatic/Alicyclic); MDI (Aromatic) [22] [26] [24] | Forms the urethane linkage in hard segments; Aliphatic offers light stability, aromatic offers mechanical strength. |

| Polyols | PTHF, PCL, PO3G, PPG [22] [26] [24] | Constitutes the soft segment; governs flexibility, elasticity, and primary degradation profile. |

| Dynamic Chain Extenders | HEDS (Disulfide), VAN-OH (Imine), DiSe (Diselenide) [6] [5] [26] | Introduces reversible covalent bonds into polymer backbone (often in hard segment) to enable intrinsic self-healing. |

| Ionic Center Sources | DMPA [22] [6] | Provides internal emulsification sites (ionic groups) for the formation of stable waterborne polyurethane dispersions. |

| Catalysts | DBTDL [6] | Accelerates the reaction between isocyanate (-NCO) and hydroxyl (-OH) groups during synthesis. |

Self-healing polyurethanes (PUs) represent a transformative class of smart materials that autonomously repair physical damage, thereby extending product lifespan, enhancing safety, and promoting sustainability. For researchers and drug development professionals, the interplay between three core properties—self-healing efficiency, mechanical strength, and biocompatibility—is paramount in designing materials for advanced applications. These properties are intrinsically linked to the underlying chemical architecture, often involving a careful balance; for instance, strategies that enhance mechanical strength can sometimes impede the molecular mobility required for efficient self-repair. This document provides a detailed analysis of these key properties, supported by quantitative data, standardized experimental protocols for their assessment, and a breakdown of critical reagent solutions, serving as a practical guide for the synthesis and application of next-generation self-healing PUs in biomedical and flexible electronic devices.

Quantitative Property Analysis

The following tables summarize the key performance metrics of various self-healing polyurethane systems as reported in recent literature, providing a benchmark for researchers.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Intrinsic Self-Healing Polyurethanes

| Material System | Self-Healing Mechanism | Healing Conditions | Healing Efficiency | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elongation at Break (%) | Key Applications | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vanillin-based WPU | Dynamic Imine Bonds | 80 °C, 30 min | ~100% (scratch closure) | 12.8 | N/R | Protective Coatings, Adhesives | [6] |

| Aromatic Disulfide WPU | Disulfide Metathesis | 25 °C, 48 h | >83% (tensile strength) | 11.0 | N/R | High-Strength Coatings | [5] |

| Diselenide WPU | Diselenide Metathesis | Visible Light, 48 h | >90% | 16.31 | N/R | Robust, Self-Healing Films | [5] |

| PU with Halloysite Clay | Dynamic Carbonate Exchange | Room Temperature, Autonomous | Maintained | Improved vs. unfilled | Improved vs. unfilled | Structural Composites | [28] |

| PU-Urea Nanocomposite | Disulfide + Cellulose Nanocrystals | 80 °C, 24 h | >82% (elongation) | 48.0 | N/R | High-Toughness Materials | [29] |

| Dimethylglyoxime SHE | Oxime-Urethane Bonds | 37 °C, 5 min (Autonomous) | Functional Recovery | 0.033 - 4.383 | 506 - 3295 | Aortic Aneurysm, Nerve Repair | [30] |

| PU with UPy & Graphene | Multiple H-bonds | 80 °C, 1 h | 88 - 91% | ~5.0 | N/R | 3D Printed Devices | [29] |

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Self-Healing Mechanisms and Trade-Offs

| Healing Mechanism | Typical Healing Stimulus | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation | Impact on Biocompatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Covalent Bonds (Diels-Alder) | Heat (e.g., 60-120 °C) | Robust healed strength | High healing temperature | Potential concern from high temp |

| Dynamic Covalent Bonds (Disulfide) | Room Temp / Visible Light | Mild healing conditions | Lower mechanical strength | Favorable (avoids harsh conditions) |

| Dynamic Covalent Bonds (Imine) | Heat / pH | High design flexibility | Susceptible to hydrolysis | Can be tailored for biodegradability |

| Non-Covalent Bonds (H-bond, Ionic) | Room Temperature / Moisture | Fast healing kinetics | Low mechanical strength | Generally high (no toxic catalysts) |

| Supramolecular Dual Network (H-bond + Diels-Alder) | Heat | Synergistic property enhancement | Complex synthesis | Depends on individual components |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Synthesis of Vanillin-derived Self-Healing WPU

This protocol outlines the synthesis of a bio-based waterborne polyurethane (WPU) using a vanillin-derived diol (VAN-OH) containing dynamic imine bonds, yielding materials with enhanced mechanical strength and self-healing properties [6].

- Objective: To synthesize a self-healing WPU dispersion with a tensile strength of approximately 12.8 MPa and scratch-healing capability at 80 °C within 30 minutes.

Materials:

- Polytetrahydrofuran (PTHF, Mn = 1000 g/mol)

- Isophorone diisocyanate (IPDI)

- Dimethylolpropionic acid (DMPA)

- Vanillin diol (VAN-OH, synthesized via condensation of vanillin and ethylenediamine)

- Dibutyltin dilaurate (DBTDL, catalyst)

- Triethylamine (TEA, neutralizer)

- Deionized Water

- Nitrogen Gas

Equipment:

- 100 mL three-necked reactor equipped with mechanical stirrer, reflux condenser, and thermometer.

- Heating mantle with temperature control.

- Dropping funnel.

- Vacuum oven.

Procedure:

- Prepolymer Formation: Charge 15 g (15.9 mmol) of PTHF and 6 g (27 mmol) of IPDI into the dry reactor. Add 20 µL of DBTDL catalyst. Purge the system with nitrogen and heat the mixture to 70 °C with continuous mechanical stirring for 4 hours.

- Chain Extension: Add 1 g (7.5 mmol) of DMPA and 1.2 g (3.6 mmol) of VAN-OH to the reactor. Increase the temperature to 80 °C and continue stirring until the reaction mixture reaches the theoretical NCO value (determined by standard dibutylamine titration).

- Cooling and Neutralization: Allow the NCO-terminated prepolymer to cool to 40 °C. Gradually add a mixture of distilled water and TEA via the dropping funnel to neutralize the carboxylic acid groups of DMPA. Maintain stirring for 1 hour at 40 °C.

- Dispersion: The neutralized prepolymer will spontaneously disperse in the water phase upon vigorous stirring, resulting in a stable, milky-white WPU-VAN-OH dispersion.

- Film Formation: Cast the dispersion into a PTFE mold and allow it to dry at room temperature for 48 hours, followed by post-curing in a vacuum oven at 50 °C for 12 hours to obtain a free-standing film for testing.

Protocol: Evaluating Self-Healing Efficiency via Tensile Test

This protocol describes a quantitative method for assessing the healing efficiency of a self-healing polyurethane film by comparing its mechanical properties before and after a healing cycle [5] [29].

- Objective: To quantify the self-healing efficiency (%) by measuring the recovery of tensile strength.

Materials & Equipment:

- Self-healing PU film (dumbbell-shaped specimens, e.g., ASTM D638 Type V)

- Universal Tensile Testing Machine

- Surgical blade or scalpel

- Environmental chamber (if healing requires controlled temperature/humidity)

- Light source (if photo-triggered)

Procedure:

- Initial Mechanical Test: Perform a uniaxial tensile test on a pristine dumbbell specimen (n ≥ 3) at a constant crosshead speed (e.g., 50 mm/min). Record the average tensile strength (σ₁).

- Specimen Damage: Completely cut through the center of a new set of dumbbell specimens (n ≥ 3) using a scalpel.

- Healing Cycle: Gently bring the two cut surfaces into contact. Subject the specimens to the required healing conditions (e.g., 80 °C for 30 minutes [6], room temperature for 48 hours [5], or visible light irradiation). Apply minimal external pressure if necessary to ensure good contact.

- Healed Mechanical Test: After the healing period, perform the tensile test on the healed specimens under the same conditions as step 1. Record the average tensile strength of the healed samples (σ₂).

- Calculation: Calculate the healing efficiency (η) using the formula: η (%) = (σ₂ / σ₁) × 100

Protocol: In Vitro Biocompatibility Assessment

This protocol outlines a fundamental cytotoxicity test according to ISO 10993-5, a critical first step in evaluating the biocompatibility of self-healing PUs for biomedical applications [30].

- Objective: To assess the in vitro cytotoxicity of a self-healing PU extract using a fibroblast cell line.

Materials & Equipment:

- PU film (sterilized by UV irradiation or ethanol immersion)

- Fibroblast cell line (e.g., L929 or NIH/3T3)

- Cell culture medium (e.g., DMEM with 10% FBS)

- Sterile extraction vehicle (e.g., PBS or culture medium without FBS)

- Multi-well cell culture plates

- CO₂ incubator (37 °C, 5% CO₂)

- Cell proliferation assay kit (e.g., MTT, CCK-8)

Procedure:

- Extract Preparation: Following ISO 10993-12 guidelines, prepare an extract by immersing the sterilized PU film in the extraction vehicle at a surface-area-to-volume ratio of 3 cm²/mL (or 0.1 g/mL). Incubate at 37 °C for 24 hours. Use a vehicle-only extract as a negative control.

- Cell Seeding: Seed fibroblasts in a 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 10⁴ cells per well in complete culture medium. Incubate for 24 hours to allow cell attachment.

- Exposure: Aspirate the medium from the wells and replace it with 100 µL of the PU extract, negative control extract, or fresh medium (as a baseline). Incubate the plates for a predetermined period (e.g., 24, 48, or 72 hours).

- Viability Assessment: After the exposure period, assess cell viability quantitatively using a colorimetric assay like MTT or CCK-8 according to the manufacturer's instructions. Measure the absorbance using a microplate reader.

- Analysis: Calculate the relative cell viability (%) compared to the negative control group. A material is generally considered non-cytotoxic if relative cell viability exceeds 70-80%.

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualizations

Self-Healing Chemical Mechanisms

Self-Healing Cycle

Property Interplay & Material Design

Property Design Map

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Self-Healing Polyurethane Research

| Reagent / Chemical | Function in Synthesis | Key Rationale & Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Polyether/Polyester Diols (e.g., PTMG, PTHF) | Forms the soft segment of the PU backbone. | High molecular weight enhances chain mobility and room-temperature self-healing. Polycarbonate diols (PCDs) offer superior hydrolytic stability [28]. |

| Diisocyanates (e.g., IPDI, HDI, MDI) | Forms the hard segment with the chain extender. | Aliphatic isocyanates (IPDI, HDI) offer better light stability. Aromatic isocyanates (MDI) can provide higher mechanical strength [31]. |

| Dynamic Diol Chain Extenders | Introduces reversible bonds into the polymer network. | Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl) disulfide enables room-temperature metathesis [32]. Vanillin-derived diols provide bio-based, dynamic imine bonds [6]. Di(1-hydroxyethylene) diselenide allows visible-light-triggered healing [5]. |

| Dimethylolpropionic Acid (DMPA) | Internal emulsifier for Waterborne PU (WPU) dispersions. | Introduces ionic centers (-COOH) for water dispersibility after neutralization with TEA. Content affects dispersion stability and final film properties [6]. |

| Dibutyltin Dilaurate (DBTDL) | Catalyst for the urethane reaction (NCO-OH). | Significantly accelerates the reaction rate. Must be used sparingly as residual catalyst can affect long-term stability and biocompatibility [6]. |

| Nanofillers (e.g., Halloysite Clay, Graphene) | Mechanical reinforcement. | Halloysite clay (0.5-3 wt.%) improves strength without sacrificing autonomous self-healing [28]. Graphene (1-3 wt.%) enhances mechanical and electrical properties [29]. Dispersion is critical. |

Synthesis Strategies and Pioneering Applications in Biomedicine and Drug Delivery

Synthetic Routes for Incorporating Dynamic Bonds into the PU Backbone

The integration of dynamic bonds into the polyurethane (PU) backbone represents a paradigm shift in material design, enabling the creation of intelligent, self-healing materials. Intrinsic self-healing polyurethanes repair damage through the reversible fracture and reformation of dynamic bonds, a mechanism that offers significant advantages over extrinsic systems, including multiple healing cycles and no requirement for embedded healing agents [33] [2]. The primary challenge in this field lies in balancing high mechanical strength with efficient self-healing capabilities, often at room temperature [34]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for synthesizing PUs with various dynamic covalent bonds, focusing on their incorporation into the polymer backbone to equip researchers with the methodologies needed to advance this field.

Dynamic covalent bonds are characterized by their ability to undergo reversible cleavage and reformation under specific stimuli. When incorporated into the PU backbone, they impart reprocessability and self-healing properties. The table below summarizes the key dynamic bonds used in these synthetic strategies.

Table 1: Key Dynamic Covalent Bonds for PU Backbones

| Dynamic Bond | Typical Stimuli | Dynamic Mechanism | Key Advantages | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aromatic Disulfide | Room Temperature, Heat [33] | Metathesis Exchange Reaction [34] | Room-temperature autonomy; good mechanical strength [33] | Expensive monomers; yellow coloration [33] |

| Diselenide | Visible Light [33] | Radical-mediated Exchange [33] | Very low bond energy; visible-light responsiveness [33] | Limited monomer availability; potential toxicity |

| Imine (Schiff Base) | Heat, pH, Water-assisted [34] | Hydrolysis/Re-condensation; Metathesis [34] | Fast exchange kinetics; bio-based precursors available [6] | Instability in acidic conditions [34] |

| Diels-Alder Adduct | Heat (~60°C form, 100-150°C break) [34] | Reversible Cycloaddition [34] | Strong covalent network; high mechanical strength | Requires elevated temperatures for healing |

| Boronic Ester | pH, Heat [34] | Transesterification [34] | Catalyst-free exchange; self-heals in hydrogels [34] | pH-dependent stability; often poor mechanical properties [34] |

Experimental Protocols & Application Notes

Protocol 1: Incorporating Aromatic Disulfide Bonds via Chain Extension

This protocol outlines the synthesis of room-temperature self-healing PU using bis(4-hydroxyphenyl) disulfide (HPS) as a chain extender, introducing dynamic aromatic disulfide bonds into the hard segment of the polymer backbone [33].

Research Reagent Solutions

- Polyol Soft Segment: Polytetramethylene ether glycol (PTMG, Mn = 1000-2000 g/mol). Function: Forms the flexible matrix of the PU.

- Diisocyanate: Isophorone diisocyanate (IPDI) or Toluene 2,4-diisocyanate (TDI). Function: Reacts with polyol and chain extender to form urethane links.

- Dynamic Chain Extender: Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl) disulfide (HPS). Function: Introduces dynamic aromatic disulfide bonds into the polymer backbone.

- Catalyst: Dibutyltin dilaurate (DBTDL). Function: Catalyzes the urethane formation reaction.

- Solvent: Anhydrous N, N-Dimethylformamide (DMF). Function: Reaction solvent.

Detailed Methodology

- Prepolymer Synthesis: Charge a dry 250 mL three-neck flask with PTMG (0.05 mol) and IPDI (0.11 mol) under a nitrogen atmosphere. Add 3 drops of DBTDL catalyst. Heat the reaction mixture to 80°C with continuous mechanical stirring for 3 hours. Monitor the reaction by tracking the %NCO content using the standard dibutylamine back-titration method until the theoretical NCO value for the prepolymer is reached.

- Chain Extension: Cool the prepolymer to 70°C. Dissolve HPS (0.06 mol) in a minimal amount of warm DMF and add it dropwise to the prepolymer over 15 minutes. Maintain the temperature at 70°C with vigorous stirring for 4-6 hours until the FTIR spectrum shows the disappearance of the isocyanate peak (~2270 cm⁻¹).

- Precipitation and Drying: Once the reaction is complete, cool the viscous solution to room temperature. Precipitate the polymer by pouring it into a large excess of vigorously stirred ice-cold methanol. Filter the resulting white, fibrous solid and wash with fresh methanol. Dry the product in a vacuum oven at 50°C for 24 hours to constant weight.

Performance Data: PUs synthesized via this route have demonstrated tensile strengths up to 11.0 MPa and toughness of 52.1 MJ m⁻³. They can achieve a healing efficiency of over 83% for tensile strength after 48 hours at room temperature [33].

Protocol 2: Synthesis of Visible-Light Responsive PU with Diselenide Bonds

This protocol describes the synthesis of a waterborne PU (WPU) system incorporating dynamic diselenide bonds, which enable self-healing under visible light irradiation [33].

Research Reagent Solutions

- Diselenide Diol Monomer: Di(1-hydroxyethylene) diselenide (DiSe). Function: The dynamic moiety that undergoes exchange under visible light.

- Polyol Soft Segment: Polytetramethylene ether glycol (PTMG).

- Diisocyanate: Isophorone diisocyanate (IPDI).

- Ionic Center Agent: Dimethylolpropionic acid (DMPA). Function: Provides colloidal stability in water.

- Neutralizing Agent: Triethylamine (TEA). Function: Neutralizes DMPA's carboxylic acid groups to form salts.

- Catalyst: Dibutyltin dilaurate (DBTDL).

Detailed Methodology

- Prepolymer Synthesis: In a 500 mL flask equipped with a mechanical stirrer and reflux condenser, combine PTMG (0.04 mol), DiSe (0.01 mol), and IPDI (0.11 mol). Add DBTDL and heat to 75°C under N₂ for 2.5 hours.

- Ionic Modification: Cool the system to 60°C. Add DMPA (0.02 mol) and continue the reaction until the theoretical NCO content is achieved.

- Neutralization and Dispersion: Cool the prepolymer to 40°C. Add TEA (0.02 mol) to neutralize the carboxylic groups and stir for 30 minutes. Subsequently, add ice-cold deionized water at high stirring speed (2000 rpm) to form a stable emulsion. Stir for an additional hour to ensure complete chain extension via water.

- Film Formation: Cast the emulsion into a PTFE mold and allow it to dry at room temperature for 7 days, followed by vacuum drying to remove residual moisture.

Performance Data: The optimized diselenide-based WPU (DSe-WPU) can achieve a healing efficiency exceeding 90% after 48 hours under visible light irradiation [33].

Protocol 3: Bio-based PU with Dynamic Imine Bonds from Vanillin

This green chemistry protocol utilizes a vanillin-derived diol to incorporate dynamic imine bonds into the WPU backbone, offering a sustainable and high-performance route [6].

Research Reagent Solutions

- Vanillin Diol (VAN-OH): Synthesized from vanillin and ethylenediamine. Function: Bio-based chain extender providing dynamic imine bonds.

- Polyol: Polytetrahydrofuran (PTHF, Mn = 1000 g/mol).

- Diisocyanate: Isophorone diisocyanate (IPDI).

- Ionic Center Agent: Dimethylolpropionic acid (DMPA).

- Neutralizing Agent: Triethylamine (TEA).

- Catalyst: Dibutyltin dilaurate (DBTDL).

Detailed Methodology

- Synthesis of VAN-OH: Dissolve vanillin (32 mmol) in 5 mL ethanol in a 100 mL three-neck flask. Add ethylenediamine (16 mmol) dropwise, resulting in a yellow precipitate. Reflux the mixture at 55°C for 8 hours. Filter the precipitate, wash with ethanol/water, and dry under vacuum at 70°C [6].

- Solvent-Free Prepolymer Formation: Charge PTHF (15.9 mmol) and IPDI (27 mmol) into a reactor with DBTDL. Heat to 70°C under N₂ for 4 hours.

- Chain Extension: Add DMPA (7.5 mmol) and VAN-OH (3.6 mmol) to the prepolymer. Stir at 80°C until the theoretical NCO value is reached.

- Neutralization and Dispersion: Cool the prepolymer to 40°C. Gradually add a mixture of water and TEA under mechanical stirring to neutralize the DMPA and disperse the polymer, resulting in a milky WPU-VAN-OH dispersion [6].

Performance Data: The resulting WPU-VAN-OH films exhibit a tensile strength of 12.8 MPa (three times greater than standard WPU) and can completely mend surface scratches within 30 minutes at 80°C [6].

Table 2: Comparative Performance of PUs with Different Dynamic Bonds

| Dynamic Bond | Example Tensile Strength (MPa) | Example Healing Conditions | Healing Efficiency | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aromatic Disulfide [33] | 6.8 - 11.0 | 25°C, 2 - 48 h | 75% - >83% (Strength) | Leather coatings, flexible elastomers |

| Diselenide [33] | Up to 16.31 | Visible Light, 48 h | >90% (Strength) | Light-responsive coatings |

| Imine (Vanillin-based) [6] | 12.8 | 80°C, 0.5 h | ~100% (Visual) | Sustainable protective coatings, adhesives |

| Disulfide + Hydrogen Bonds [34] | 75.8 | 85°C, 1 h | 71.5% (Strength) | High-strength, healable materials |

Visual Synthesis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the general decision-making workflow and logical relationships for selecting and implementing a synthetic route for dynamic PUs.

Synthetic Route Decision Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagent Solutions for Dynamic PU Synthesis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Diisocyanates | Forms urethane bonds; influences phase separation and microphase structure. | IPDI (aliphatic, weatherability), TDI (aromatic, reactivity), MDI (aromatic, rigidity) [33] [35] |

| Macropolyols (Soft Segment) | Determines flexibility, elasticity, and low-temperature performance. | PTMG (polyether, hydrolysis resistance), PTHF (polyether), Polyester diols (mechanical strength) [33] [6] |

| Dynamic Chain Extenders | Introduces reversible bonds into the hard segment; key to self-healing. | Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl) disulfide, Di(1-hydroxyethylene) diselenide, Vanillin-derived diol (VAN-OH) [33] [6] |

| Catalysts | Accelerates the urethane formation reaction between NCO and OH groups. | Dibutyltin dilaurate (DBTDL) [6] |

| Ionic Dispersion Agents | Enables formation of waterborne systems (WPUs) for eco-friendly processing. | Dimethylolpropionic acid (DMPA) [33] [6] |

Design of Amphiphilic Polyurethane/Peptide Carriers for Controlled Drug Release

The development of smart drug delivery systems is a cornerstone of modern precision medicine. Among the most promising strategies is the design of amphiphilic polyurethane (PU) carriers, which offer superior biocompatibility and tunable mechanical properties. When integrated with self-assembling peptides, these materials form advanced platforms capable of targeted and controlled therapeutic release. Furthermore, the incorporation of self-healing mechanisms, driven by dynamic covalent bonds or reversible physical interactions, significantly enhances the durability and longevity of these carriers, making them highly suitable for demanding biomedical applications such as minimally invasive procedures and sustained drug delivery [36] [2]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for the synthesis and characterization of these multifunctional carriers, framing the work within a broader thesis on self-healing polyurethanes.

Experimental Protocols

Synthesis of Amphiphilic Polyurethane Pre-polymer

This protocol outlines the synthesis of an amphiphilic polyurethane pre-polymer adapted from established methods [36] [37], utilizing poly(ethylene oxide)-poly(propylene oxide)-poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO–PPO–PEO, e.g., Pluronic P123) to confer amphiphilicity and thermosensitive behavior.

Key Reagent Solutions:

| Research Reagent | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Pluronic P123 Macrodiol | Forms the soft segment; provides amphiphilicity and thermosensitive sol-gel transition [36]. |

| Aliphatic Diisocyanate (e.g., HDI) | Reacts with macrodiol hydroxyl groups to build the PU backbone; aliphatic isocyanates are preferred for biocompatibility [36] [37]. |

| Dibutyltin Dilaurate (DBTDL) | Catalyst for the urethane polymerization reaction [37]. |

| Anhydrous Dichloroethane | Solvent; anhydrous conditions prevent undesirable side reactions with water [37]. |

Procedure:

- Preparation: Dry Pluronic P123 macrodiol under vacuum at 110°C for 2 hours to remove residual moisture. Purity the aliphatic diisocyanate (e.g., Hexamethylene Diisocyanate, HDI) by distillation if necessary.

- Reaction Setup: In a three-necked round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer, reflux condenser, and argon inlet, dissolve the dried Pluronic P123 (e.g., 10 mmol) in anhydrous dichloroethane. Purge the system with inert gas (Ar or N₂).

- Catalyst Addition: Add 50 µL of DBTDL catalyst to the solution [37].

- Polymerization: With constant stirring under an argon atmosphere, add the aliphatic diisocyanate (e.g., HDI) at a molar ratio of NCO:OH = 1:1. Maintain the reaction temperature at 45°C for 48 hours [37].

- Termination and Purification: After 48 hours, stop the reaction by exposing the mixture to air. The resulting pre-polymer can be purified by precipitation into a cold non-solvent (e.g., hexane or diethyl ether) and dried under vacuum until constant mass.

Preparation of Polyurethane/Peptide Hybrid Gel

This protocol describes the integration of a collagen-inspired octapeptide into the polyurethane matrix to form a hybrid gel with enhanced mechanical and self-healing properties [36].

Procedure:

- Peptide Solution: Prepare an aqueous solution of the synthetic collagen-inspired peptide.

- Hydration: Hydrate the synthesized amphiphilic polyurethane pre-polymer in the aqueous peptide solution. The mixture will self-assemble into micellar structures.

- Gel Formation: Allow the mixture to equilibrate to form a gel. The gelation process involves dynamic intermolecular interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions) between the polyurethane and peptide segments [36].

- Characterization: The resulting hybrid gel can be characterized for its micelle size distribution, sol-gel transition temperature, and rheological properties as described in subsequent sections.

Drug Loading and Release Study

This protocol provides a general method for evaluating the carrier's efficiency in encapsulating and releasing a model drug, such as sodium diclofenac [37].

Procedure:

- Drug Loading: Incubate the pre-formed PU/peptide hydrogel with a concentrated solution of the drug (e.g., sodium diclofenac in ethanol) for 24 hours. The partition coefficient can be used to quantify loading efficiency [37].

- In Vitro Release Simulation:

- Place the drug-loaded hydrogel in a release apparatus containing an acidic medium (e.g., pH ~2.0, simulating gastric fluid) for a predetermined time (e.g., 2 hours). Monitor the drug release, which should be minimal (<5%) in this environment [37].

- Transfer the system to a neutral phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution (pH 7.4, simulating intestinal fluid). Continue to monitor the drug release over time (e.g., up to 40 hours) until a cumulative release of approximately 80% is achieved [37].

- Analysis: Sample the release medium at regular intervals and analyze the drug concentration using a validated method such as UV-Vis spectroscopy. Plot the cumulative drug release versus time to determine the release profile and kinetics.

Characterization and Data Analysis

Micellar Characterization and Gelation Kinetics

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) and rheological measurements are critical for understanding the self-assembly behavior and material properties of the carrier system. The data below, derived from a model system [36], should be presented in your thesis as follows:

Table 1: Micelle Hydrodynamic Diameter and Gelation Properties

| Peptide Content | Temperature | Hydrodynamic Diameter (DLS) | Sol-Gel Transition Time | Structure Recovery Time (after deformation) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 25°C | Bimodal distribution: ~30-40 nm and ~300-400 nm | 20-30 seconds | ~60 seconds (without peptide) |

| Low | 37°C | Bimodal distribution | 20-30 seconds | - |

| High | 25°C | Bimodal distribution | 20-30 seconds | - |

| High | 37°C | Monomodal distribution: ~25 nm | Equilibrium reached after >1 hour | ~300 seconds |

Key Findings:

- The transition from a bimodal to a monomodal micelle distribution at body temperature (37°C) with high peptide content indicates a peptide-mediated reorganization into more defined nanostructures [36].

- While the initial sol-gel transition is very fast (20-30 s), the peptide slows down the establishment of the final gel equilibrium, suggesting it enhances chain entanglement [36].

- The presence of peptide enables complete structural recovery after deformation, a key self-healing property, albeit over a longer timescale (~300 s) [36].

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental workflow from synthesis to characterization, highlighting the key stages in the development of the PU/Peptide carrier.

Self-Healing Mechanism in Polyurethane Carriers

The durability of these carriers is underpinned by intrinsic self-healing mechanisms. The following diagram and table detail the bonding interactions that enable damage repair.

Table 2: Key Self-Healing Mechanisms in Polyurethane/Peptide Carriers

| Mechanism Type | Specific Interaction | Role in Self-Healing | Stimulus-Responsiveness |

|---|---|---|---|