Revolutionizing Polymer Composites: A Comprehensive Guide to AI-Driven Filler Selection and Optimization for Advanced Materials

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are transforming the design of polymer composites, specifically focusing on filler selection and optimization.

Revolutionizing Polymer Composites: A Comprehensive Guide to AI-Driven Filler Selection and Optimization for Advanced Materials

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are transforming the design of polymer composites, specifically focusing on filler selection and optimization. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of composite material challenges, details the application of predictive AI models like Gaussian Process Regression and Graph Neural Networks, and offers practical guidance for troubleshooting data and model limitations. It further examines the rigorous validation and comparative analysis of AI methods against traditional approaches. The scope synthesizes current research to empower professionals in leveraging these tools to accelerate the development of next-generation materials with tailored mechanical, thermal, and functional properties.

From Trial-and-Error to AI: Understanding the Polymer Composite Design Challenge

1. Introduction and Context

This application note details the critical material science considerations for filler selection in polymer composites, framed within a broader AI-driven research thesis. The systematic characterization and optimization of filler properties—type, size, shape, loading, and dispersion—are foundational for generating high-quality, structured datasets. These datasets are essential for training machine learning models to predict composite properties and recommend optimal filler formulations for target applications, such as controlled drug delivery systems or tissue engineering scaffolds.

2. Summary of Key Filler Properties and Quantitative Data

The following table summarizes the primary filler property dimensions and their typical ranges/effects, based on current literature.

Table 1: Multidimensional Filler Property Space for Polymer Composites

| Property Dimension | Common Examples | Typical Size Range | Key Influence on Composite | Target Metrics Affected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type (Chemistry) | SiO₂, TiO₂, HA, CNTs, Graphene, Clay | N/A | Biocompatibility, degradation, surface chemistry, reactivity. | Drug loading efficiency, cytotoxicity, modulus, degradation rate. |

| Size | Nanoparticles, Microparticles | 10 nm – 100 µm | Surface area-to-volume ratio, packing density, light scattering. | Tensile strength, barrier properties, release kinetics, opacity. |

| Shape | Spherical, Rod-like, Plate-like, Fibrous | Aspect Ratio: 1 to >1000 | Stress transfer, percolation threshold, viscosity, alignment. | Electrical/thermal conductivity, fracture toughness, rheology. |

| Loading (wt.% / vol.%) | Low to High Concentration | 0.1 – 60 wt.% (varies by system) | Filler-matrix interaction density, agglomeration tendency. | Young's Modulus, viscosity, glass transition temperature (Tg). |

| Dispersion Quality | Agglomerated, Well-dispersed | N/A (Qualitative/Statistical) | Homogeneity of property enhancement, defect sites. | Ultimate tensile strength, elongation at break, reliability. |

3. Experimental Protocols for Filler Characterization

Protocol 3.1: Quantitative Analysis of Filler Dispersion via Image Analysis Objective: To quantify the degree of filler agglomeration and spatial distribution within a composite matrix from SEM/TEM micrographs. Materials: SEM/TEM images of composite cross-section, ImageJ/FIJI software. Procedure:

- Image Pre-processing: Import micrograph. Convert to 8-bit. Apply background subtraction and threshold adjustment to clearly distinguish filler particles from the matrix.

- Particle Analysis: Use the "Analyze Particles" function. Set a size circularity limit to exclude artifacts. Output data includes: particle count, area, centroid coordinates.

- Dispersion Metrics Calculation:

- Agglomerate Ratio: (Number of particles > 2x mean particle size) / (Total particle count).

- Nearest Neighbor Distance (NND): Calculate the mean and standard deviation of distances between each particle centroid and its nearest neighbor. A low mean and low standard deviation indicate uniform dispersion.

- Quadrant Method: Overlay a grid of quadrants. Calculate the particle count per quadrant. The coefficient of variation (CV = Std. Dev./Mean) of quadrant counts is a dispersion index (lower CV = better dispersion). Deliverable: Agglomeration ratio, NND (mean ± std dev), Dispersion Index (CV).

Protocol 3.2: Rheological Assessment of Filler Loading and Shape Effects Objective: To determine the influence of filler loading and shape on composite processability and percolation behavior. Materials: Rheometer (parallel plate geometry), prepared composite resin/filament. Procedure:

- Sample Loading: Load sample between plates pre-set to gap (e.g., 1 mm). Trim excess.

- Amplitude Sweep: At constant frequency (e.g., 10 rad/s), strain from 0.01% to 100%. Determine the linear viscoelastic region (LVR).

- Frequency Sweep: Within the LVR (e.g., at 0.1% strain), log sweep frequency from 100 to 0.1 rad/s. Record complex viscosity (η*), storage (G'), and loss (G'') moduli.

- Analysis: Plot η* vs. frequency. High aspect ratio fillers (e.g., CNTs) show stronger shear-thinning. Plot G' vs. loading. A sharp rise in G' at low frequency indicates a percolation network formation. Identify the critical loading for gelation/percolation. Deliverable: Complex viscosity profiles, percolation threshold loading, G' vs. frequency plots.

4. The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Filler-Composite Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Silane Coupling Agents (e.g., APTES, MPS) | Modifies filler surface chemistry to improve interfacial adhesion with polymer matrix, reducing agglomeration. |

| Pluronic F-127 / PVP (Polyvinylpyrrolidone) | Non-ionic surfactants used as dispersion aids for nanoparticles in aqueous or solvent-based systems to prevent aggregation. |

| Polymer Matrix (PLA, PCL, PEGDA, Epoxy Resin) | Base material forming the continuous phase of the composite; selected for biocompatibility, degradability, or mechanical properties. |

| Ultra-sonicator (Probe Type) | Applies high-intensity ultrasonic energy to break apart filler agglomerates and promote uniform dispersion in suspensions prior to mixing. |

| Three-Roll Mill | High-shear mechanical mixer used to exfoliate layered fillers (e.g., graphene, clay) and distribute them uniformly in viscous polymer matrices. |

| Zetasizer Nano ZS | Instrument for dynamic light scattering (DLS) to measure particle size distribution and zeta potential of filler suspensions, indicating stability. |

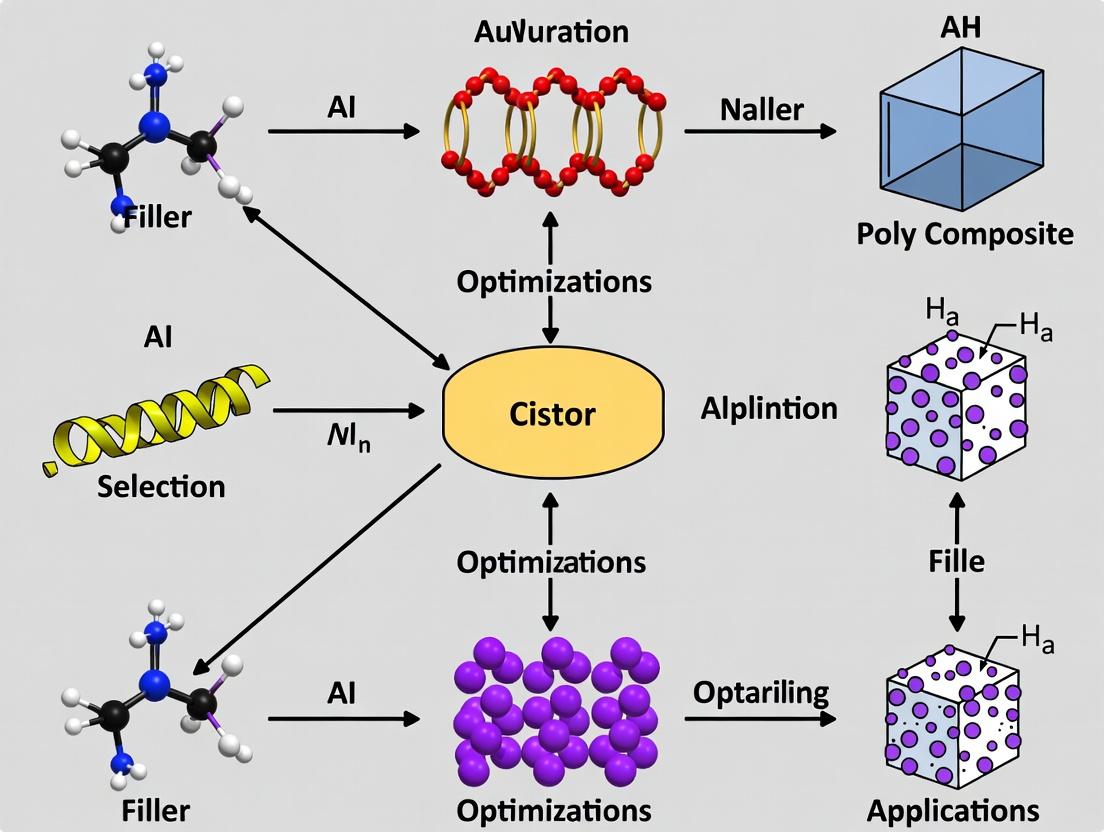

5. Visualizing Relationships and Workflows

Diagram Title: AI-Driven Composite Optimization Workflow

Diagram Title: Key Filler Property Interactions & Trade-offs

Traditional Filler Selection Methods and Their Limitations in High-Dimensional Spaces

This application note, framed within a broader thesis on AI-driven polymer composite development, details conventional methodologies for filler selection and their inherent constraints when applied to high-dimensional parameter spaces. These methods, while foundational, become inefficient for modern multifunctional composites and high-throughput pharmaceutical excipient development. We provide structured data, experimental protocols, and visual workflows to elucidate these limitations.

Traditional filler selection for polymer composites and drug formulation matrices relies on heuristic, trial-and-error, and one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approaches. These methods systematically evaluate fillers (e.g., silica, carbon black, cellulose nanocrystals) based on a limited set of properties. In high-dimensional spaces—where parameters include filler aspect ratio, surface energy, chemical functionality, concentration, dispersion method, and interfacial adhesion—these traditional methods fail to capture complex, non-linear interactions, leading to suboptimal material performance.

Experimental Protocol: OFAT Screening for Mechanical Reinforcement

Aim: To determine the optimal loading of a single filler type (e.g., micron-sized silica) for tensile strength enhancement in an epoxy matrix.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a base epoxy resin (e.g., Diglycidyl ether of bisphenol-A) with a hardener (e.g., Triethylenetetramine) at a specified stoichiometric ratio.

- Divide the mixture into 5 equal batches.

- Incorporate silica filler at 0, 5, 10, 15, and 20 wt% into respective batches using a planetary centrifugal mixer (e.g., Thinky ARE-250) at 2000 rpm for 3 minutes. Ensure consistent degassing.

- Cast mixtures into dog-bone shaped molds per ASTM D638.

- Cure at room temperature for 24 hours, followed by a 2-hour post-cure at 80°C.

- Testing & Analysis:

- Perform tensile testing (ASTM D638) using a universal testing machine (e.g., Instron 5966) with a 5 mm/min crosshead speed (n=5 per group).

- Measure Young's modulus, tensile strength, and elongation at break.

- Analyze fracture surfaces via Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to assess dispersion and failure mechanisms.

Table 1: Results from OFAT Silica/Epoxy Composite Screening

| Silica Loading (wt%) | Young's Modulus (GPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elongation at Break (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (Neat Epoxy) | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 65 ± 3 | 7.5 ± 0.4 |

| 5 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 68 ± 2 | 6.8 ± 0.3 |

| 10 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 72 ± 4 | 5.9 ± 0.5 |

| 15 | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 70 ± 3 | 4.2 ± 0.3 |

| 20 | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 61 ± 5 | 2.8 ± 0.2 |

Limitations in High-Dimensional Spaces

Traditional methods like OFAT, heuristic rule-of-mixtures, and simple design-of-experiment (Taguchi) face critical limitations:

- Combinatorial Explosion: Testing all combinations of 5 fillers, 5 loadings, 3 surface treatments, and 3 dispersion methods requires 225 experiments, which is resource-prohibitive.

- Ignored Interactions: They cannot model non-linear synergies or antagonisms between parameters (e.g., surface treatment efficacy dependent on both filler type and loading).

- Local Optima: They identify the best condition within the narrow tested subspace, potentially missing a global optimum in the broader high-dimensional space.

- Single-Objective Focus: They struggle to balance multiple, often competing, objectives (e.g., maximizing conductivity while minimizing viscosity for printable composites).

Visualizing the Traditional Workflow and Its Limitations

Diagram Title: Traditional filler selection workflow and key limitations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Traditional Filler Selection Experiments

| Item (Example) | Function in Protocol | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Epoxy Resin (DGEBA) | Polymer matrix for composite. | Purity, epoxy equivalent weight, viscosity. |

| Silica Nanoparticles (Aerosil 200) | Model inorganic filler for reinforcement. | Surface area, hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity, aggregate size. |

| (3-Glycidyloxypropyl)trimethoxysilane (GPS) | Coupling agent to modify filler-matrix interface. | Hydrolysis conditions, concentration, reactivity with matrix. |

| Triethylenetetramine (TETA) | Amine-based hardener for epoxy curing. | Stoichiometric ratio, pot life, curing temperature. |

| N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) | Solvent for facilitating filler dispersion. | Polarity, boiling point, compatibility with polymer. |

| Thinky Planetary Centrifugal Mixer | Ensures uniform filler dispersion and degassing. | Mixing speed, time, and vacuum cycle parameters. |

| Instron Universal Testing Machine | Quantifies tensile/compressive mechanical properties. | Calibration, grip type, strain rate compliance with ASTM. |

| Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) | Visualizes filler dispersion and fracture morphology. | Sample coating requirements, operating voltage, vacuum. |

Note: This toolkit represents a baseline for conventional research. The transition to AI-driven methods incorporates high-throughput robotic dispensers, automated characterization, and data management platforms.

Within polymer composite filler selection and optimization research, a critical challenge is predicting material properties from constituent composition. Traditional trial-and-error experimentation is resource-intensive. This Application Note details how Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) paradigms establish quantitative, high-dimensional mappings between composite formulation (filler type, loading, surface treatment, matrix chemistry) and resultant properties (mechanical, thermal, electrical). Framed within a thesis on AI-driven materials discovery, we present protocols, data structures, and validated workflows for researchers to implement these predictive models.

Core AI/ML Paradigms in Materials Informatics

The mapping of composition to property employs several key ML paradigms, each suited to different data scenarios and prediction tasks.

Supervised Learning for Property Prediction

This is the most direct paradigm for mapping, where models learn from historical data of known compositions (features) and measured properties (labels).

- Common Algorithms: Gradient Boosting Machines (e.g., XGBoost, LightGBM), Random Forests, Support Vector Regression, and Neural Networks.

- Input Features: Numerical (filler wt%, particle size), categorical (filler type: graphene, CNT, silica; matrix type), and experimental conditions (cure temperature).

- Output Properties: Continuous (Young's modulus, conductivity) or categorical (brittle/ductile failure).

Unsupervised Learning for Pattern Discovery

Used to identify hidden clusters or reduce dimensionality in compositional space where property data is sparse or unavailable.

- Common Algorithms: t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE), Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP), and K-Means Clustering.

- Application: Grouping similar composite formulations to suggest novel, unexplored combinations in chemical space.

Generative Models for Inverse Design

Inverts the mapping to generate candidate compositions that satisfy a target property profile.

- Common Algorithms: Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), and Conditional Generative Models.

- Application: Proposing filler surface functionalization or hybrid filler ratios to achieve a specified tensile strength and dielectric constant.

The following table summarizes recent benchmark performances of ML models in predicting polymer composite properties.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of ML Models for Property Prediction

| ML Model | Dataset (Composite System) | Target Property | Prediction Error (Metric) | Key Features Used | Reference Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Boosting | 320 Epoxy/Silica Composites | Tensile Strength | MAE: 4.7 MPa | Filler load%, size, dispersion index | 2023 |

| Graph Neural Network | 210 Polymer/Graphene Nanocomposites | Electrical Conductivity | R²: 0.94 | Molecular graph of polymer, filler aspect ratio | 2024 |

| Random Forest | 185 Polypropylene/Carbon Fiber | Flexural Modulus | RMSE: 0.8 GPa | Fiber length, orientation, coupling agent | 2023 |

| Multi-task DNN | 450 Multi-filler Systems (CNT+Clay) | Strength & Toughness | Avg. MAPE: 8.5% | Hybrid ratio, processing method, cure time | 2024 |

MAE: Mean Absolute Error; RMSE: Root Mean Square Error; MAPE: Mean Absolute Percentage Error

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a Supervised ML Model for Filler Selection

Objective: To train a model that predicts the glass transition temperature (Tg) of an epoxy composite based on filler characteristics.

Materials & Data Preparation:

- Data Curation: Assemble a dataset from literature and internal experiments. Minimum recommended size: 150 distinct formulations.

- Feature Engineering:

- Numerical: Filler loading (wt%), specific surface area (m²/g), acid-base component of surface energy (∆H⁺).

- Categorical: Filler chemistry (SiO₂, Al₂O₃, BN), surface treatment (amine, epoxy, none).

- Matrix Context: Epoxy base resin type (DGEBA, Novolac), hardener stoichiometry.

- Label: Experimentally measured Tg (from DSC).

Procedure:

- Preprocessing: Normalize numerical features, one-hot encode categorical features. Split data 70/15/15 into training, validation, and test sets.

- Model Training: Train a Random Forest Regressor (scikit-learn) using the training set. Use cross-validation to tune hyperparameters (nestimators, maxdepth).

- Validation: Evaluate model on the validation set using R² score and MAE. Iterate on feature selection if performance is poor (<0.8 R²).

- Testing & Deployment: Final evaluation on the held-out test set. Deploy the trained model as a Python pickle file for predicting Tg of new filler proposals.

Protocol 2: Active Learning Loop for Optimal Filler Loading

Objective: To minimize experiments needed to find the filler loading that maximizes thermal conductivity.

Workflow:

- Initial Seed: Start with a small dataset (~10 data points) of thermal conductivity at various loadings for a given filler/matrix pair.

- Model & Predict: Train a Gaussian Process Regressor (GPR) on the current data. The GPR provides both a prediction and an uncertainty estimate across the loading range (0-30 wt%).

- Query Selection: Use an "acquisition function" (e.g., Expected Improvement) to select the next loading level to test. This function balances exploring high-uncertainty regions and exploiting high-prediction regions.

- Experiment & Iterate: Perform the experiment at the suggested loading, add the new data point to the training set, and retrain the GPR. Loop until the optimal loading is identified within a desired confidence interval (e.g., ±0.1 W/mK).

Visualizations

Title: AI/ML Workflow for Composite Design

Title: Algorithm Selection Decision Tree

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for AI-Driven Composite Research

| Item / Solution | Function in AI/ML Workflow | Example Product/ Library |

|---|---|---|

| Materials Database | Provides structured, historical data for model training. Crucial for initial dataset. | PolyInfo (NIMS), Citrination, internal LIMS. |

| Feature Calculation Software | Computes quantitative descriptors (features) from chemical structures or processing parameters. | RDKit (for molecular descriptors), pymatgen (for inorganic fillers). |

| ML Framework | Core environment for building, training, and validating predictive models. | scikit-learn, TensorFlow/PyTorch, XGBoost. |

| Automated Experimentation | Enables closed-loop active learning by executing synthesis and measurement from ML suggestions. | Chemspeed, Opentrons robots coupled with analytical instruments. |

| High-Throughput Characterization | Rapidly generates property labels (e.g., mechanical, thermal) for many samples. | Parallel DSC/TGA, automated tensile testers, high-throughput AFM. |

| Inverse Design Platform | Hosts generative models to propose novel compositions meeting target properties. | IBM MolGX, MatGAN, custom VAE implementations. |

Application Notes

Materials Informatics (MI) applies data-driven AI and machine learning (ML) to accelerate materials discovery and optimization. In the context of polymer composite filler selection, these techniques enable researchers to navigate complex property landscapes, linking filler characteristics (e.g., size, shape, surface chemistry) and processing conditions to final composite performance (e.g., tensile strength, thermal conductivity, viscosity). Key application areas include:

- Virtual Screening of Fillers: AI models predict the compatibility and performance contribution of novel or existing fillers (e.g., graphene, carbon nanotubes, silica) within a specific polymer matrix, reducing the need for exhaustive trial-and-error experimentation.

- Multi-Objective Property Optimization: ML algorithms, particularly Bayesian optimization, are used to identify optimal filler loading percentages and surface treatment protocols that simultaneously maximize multiple, often competing, target properties (e.g., stiffness vs. toughness).

- Inverse Design: Generative models and deep learning can propose novel filler architectures or composite formulations that meet a predefined set of target properties, reversing the traditional design paradigm.

- Processing-Structure-Property Linkage: AI techniques, including neural networks, establish complex, non-linear relationships between processing parameters (e.g., mixing speed, curing temperature), the resulting composite microstructure, and the macroscopic properties.

Key AI/ML Protocols in Materials Informatics

Protocol 1: High-Dimensional Dataset Construction for Polymer Composites

Objective: To assemble a structured, machine-readable dataset for training predictive models. Methodology:

- Data Sourcing: Extract data from peer-reviewed literature, internal lab notebooks, and curated databases (e.g., Polymer Properties Database, NOMAD). Key descriptors include:

- Filler Properties: Particle size distribution, aspect ratio, specific surface area, density, surface energy, functional groups.

- Matrix Properties: Polymer type, molecular weight, glass transition temperature, melt flow index.

- Processing Conditions: Mixing method, time, temperature, shear rate, curing cycle.

- Composite Properties: Tensile modulus & strength, elongation at break, thermal conductivity, electrical conductivity, viscosity.

- Feature Engineering: Calculate domain-informed features (e.g., filler volume fraction, interparticle distance estimates) to enhance model interpretability.

- Data Curation: Handle missing values using imputation or deletion. Normalize or standardize numerical features to a common scale (e.g., [0,1]).

- Structured Storage: Organize data into a structured table (e.g.,

.csv,.parquet) or a dedicated database, ensuring each row represents a unique experiment/formulation.

Protocol 2: Training a Predictive Property Model with Gradient Boosting

Objective: To build a supervised ML model that predicts a target composite property (e.g., Young's modulus) from formulation and processing features. Methodology:

- Model Selection: Choose a gradient-boosted decision tree algorithm (e.g., XGBoost, LightGBM) for its robust handling of tabular data and non-linear relationships.

- Data Splitting: Partition the dataset into training (70%), validation (15%), and hold-out test (15%) sets. Use stratified splitting if data is imbalanced.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Use a validation set and techniques like random search or Bayesian optimization to tune key hyperparameters (e.g.,

learning_rate,max_depth,n_estimators). - Model Training: Train the model on the training set, using early stopping on the validation set to prevent overfitting.

- Evaluation: Assess model performance on the unseen test set using metrics like Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and the Coefficient of Determination (R²).

Protocol 3: Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization for Filler Selection

Objective: To efficiently navigate the experimental/search space and identify Pareto-optimal filler formulations. Methodology:

- Define Objectives & Constraints: Specify target properties to maximize/minimize (e.g., maximize thermal conductivity, minimize viscosity) and any hard constraints (e.g., cost < X, filler loading ≤ Y%).

- Initialize Surrogate Model: Build Gaussian Process (GP) models for each objective using an initial small dataset (e.g., 10-20 data points from historical experiments).

- Acquisition Function Optimization: Use an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Hypervolume Improvement) to propose the next most informative experiment(s) by balancing exploration and exploitation.

- Iterative Experimentation: Conduct the proposed experiment (or simulation), measure results, and update the GP surrogate models with the new data point.

- Termination & Analysis: Iterate steps 3-4 until a performance plateau or resource limit is reached. Analyze the final Pareto front of non-dominated optimal solutions.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of ML Models for Predicting Polymer Composite Tensile Strength

| Model Type | Average R² (Test Set) | Average MAE (MPa) | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Boosting | 0.87 | 4.2 | Handles non-linearity & mixed data types | Can overfit without careful tuning |

| Random Forest | 0.85 | 4.5 | Robust to outliers & provides feature importance | Less accurate than boosting for complex tasks |

| Support Vector Machine | 0.79 | 5.8 | Effective in high-dimensional spaces | Performance sensitive to kernel choice |

| Artificial Neural Network | 0.89 | 3.9 | Captures complex interactions | Requires large datasets & extensive tuning |

Table 2: Key Features for AI-Driven Filler Selection Models

| Feature Category | Specific Examples | Data Type | Typical Impact on Model Importance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filler Physical | Volume Fraction, Aspect Ratio, Specific Surface Area | Continuous | High - Directly governs percolation & load transfer |

| Filler Chemical | Surface Energy, Functional Group Density | Continuous | Medium-High - Affects matrix-filler adhesion |

| Matrix Properties | Polymer Melt Viscosity, Glass Transition Temp (Tg) | Continuous | Medium - Defines baseline processing & performance |

| Processing | Mixing Shear Rate, Curing Temperature/Time | Continuous | Medium - Determines final dispersion & morphology |

Visualizations

Title: Core AI Workflow in Materials Informatics

Title: AI Models Link Formulation to Structure & Properties

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

| Item/Category | Function in AI-Driven Materials Research | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Curated Materials Databases | Provide structured, high-quality data for model training and benchmarking. | NIST Polymer Data Repository, Citrination, Materials Project. |

| Automated Lab Software (LIMS/ELN) | Captures experimental metadata and results in a structured, machine-readable format. | Benchling, LabArchive, custom Python scripts with Open Source tools. |

| Feature Calculation Software | Computes domain-specific molecular or material descriptors from raw structures. | RDKit (for organic moieties), Pymatgen (for inorganic fillers). |

| ML Frameworks | Libraries for building, training, and deploying predictive and generative models. | Scikit-learn (classical ML), PyTorch/TensorFlow (deep learning), GPyTorch (Bayesian optimization). |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Platforms | Generates large, consistent datasets required for robust AI models. | Automated dispensing robots, parallel rheometers, combinatorial spray coaters. |

| Inverse Design Software | Implements generative models to propose novel structures meeting property targets. | MatDeepLearn, PyXtal, custom variational autoencoder (VAE) pipelines. |

Within the broader thesis on AI for filler selection and optimization in polymer composites, the foundational step is the acquisition of high-quality, curated, and machine-readable data. This document details critical data repositories and protocols for constructing robust datasets to train predictive AI models linking composite formulation (filler type, size, surface treatment, matrix, processing) to final properties (mechanical, thermal, electrical).

Primary Public Repositories

The following table summarizes core quantitative metrics for key public data sources.

Table 1: Public Data Repositories for Polymer Composites

| Repository Name | Primary Data Type | Estimated Records (Relevant) | Accessibility | Key AI-Relevant Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIST Materials Data Repository (MDR) | Experimental property data, processing parameters | 1,000+ composite datasets | Open API, Bulk Download | Standardized JSON-LD format, linked to materials ontologies. |

| Materials Project | Computed properties (e.g., elastic tensors) of filler crystals | 150,000+ inorganic crystals | REST API | Pre-computed descriptors, crystal structures for filler screening. |

| PolyInfo (NIMS, Japan) | Experimental polymer & composite properties | ~300,000 data points | Web Interface, Limited API | Extensive mechanical & thermal properties for polymer matrices. |

| Citrination (Citrine Informatics) | Mixed experimental & calculated data | Varies by dataset | API (Key required) | Data curation tools, pattern-matching for structure-property links. |

| NanoMine | Nanocomposite formulation & property data | ~2,500 curated entries | Web Portal, SPARQL | Semantic data model, focused on nanostructured composites. |

Table 2: Proprietary/Commercial Data Sources

| Source Name | Data Scope | Access Model | Utility for AI Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knovel | Engineering handbooks, property databases | Subscription | Reliable reference data for model validation. |

| MatWeb | Manufacturer datasheets for resins & fillers | Free/Subscription | Sourcing real-world material grades and typical properties. |

| Springer Materials | Critically evaluated data collections | Institutional License | High-quality phase diagram & thermodynamic data for interfaces. |

Experimental Protocols for Data Generation

To supplement repository data, targeted experiments are required to fill data gaps. The following protocol is central to the thesis for generating standardized composite data.

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Formulation & Tensile Testing for AI Training Sets

Objective: Generate a consistent dataset linking filler parameters (type, loading, aspect ratio) to the tensile properties of an epoxy composite.

The Scientist's Toolkit:

| Reagent/Material | Function |

|---|---|

| Epoxy Resin (e.g., DGEBA) | Polymer matrix with consistent chemistry. |

| Curing Agent (e.g., Polyetheramine) | Crosslinks the epoxy resin. |

| Surface-Modified Fillers (e.g., silane-treated SiO₂, -NH₂ f-MWCNT) | Provides interfacial bonding; variable for study. |

| Dispersing Agent (e.g., BYK-110) | Aids in achieving homogeneous filler dispersion. |

| Vacuum Degassing Chamber | Removes air bubbles introduced during mixing. |

| Dual Column Tensile Tester (ASTM D638) | Measures Young's modulus, tensile strength, elongation at break. |

| Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer (DMA) | Measures viscoelastic properties (Tg, storage modulus). |

Procedure:

- Design of Experiment (DoE): Use a factorial design. Variables: Filler Type (A: spherical SiO₂, B: carbon nanotubes), Weight Fraction (0%, 0.5%, 1%, 2%), and Surface Treatment (Treated, Untreated). Total conditions: 2 x 4 x 2 = 16, plus 3 replicates = 48 samples.

- Mixing & Curing: a. Weigh epoxy resin and filler accurately. Use a speed mixer at 2000 rpm for 2 minutes. b. Add stoichiometric curing agent and dispersant (1 wt% of filler). Mix again at 2000 rpm for 3 minutes. c. Degas the mixture under vacuum until no bubbles emerge (~10 minutes). d. Pour into dog-bone silicone molds (ASTM D638 Type V). e. Cure: 2 hrs at 80°C, then 2 hrs at 120°C. Demold and post-cure at 120°C for 1 hour.

- Characterization: a. Tensile Testing: Perform on 5 specimens per condition at 1 mm/min crosshead speed. Record full stress-strain curves. b. DMA: Test one specimen per condition in tension mode, 1 Hz, 3°C/min from 30°C to 150°C.

- Data Curation: For each sample, create a structured JSON file containing:

{formulation: {...}, processing: {...}, properties: {E_modulus, tensile_strength, elongation, Tg, ...}, metadata: {test_date, operator}}.

Protocol 2: Data Extraction & Harmonization from Literature

Objective: To programmatically build a dataset from published academic literature.

Procedure:

- Query Construction: Use APIs from Springer Nature, Elsevier, and arXiv with keywords: "epoxy composite filler," "mechanical properties," "Young's modulus graphene."

- Text Mining: Use named entity recognition (NER) models (e.g.,

chemdataextractor) to parse full-text articles for materials, quantities, and properties. - Unit Harmonization: Convert all extracted property values to SI units (GPa, MPa, %) via a standardized conversion script.

- Ontology Mapping: Map extracted filler names (e.g., "multi-walled carbon nanotubes") to entries in the NanoMaterial Ontology (NMO) using a dictionary-based approach.

- Validation: Manually check a 10% subset for extraction accuracy. Flag ambiguous entries for review.

Visualization of Data Workflows

AI Composite Data Pipeline

HT Exp & AI Validation Loop

Building and Deploying AI Models for Predictive Composite Design

This application note details protocols for curating material datasets and engineering features to develop predictive AI models for polymer composite filler selection. Within the broader thesis on AI-driven optimization of polymer composites, the quality and structure of input data are paramount for accurate predictions of properties such as tensile strength, modulus, and thermal stability. These protocols are designed for researchers and scientists in materials science and related fields.

Primary Data Acquisition

Polymer composite data is typically heterogeneous, originating from experimental literature, proprietary databases, and high-throughput experimentation. The curation pipeline must address inconsistencies in reporting standards.

Protocol 2.1.1: Automated Literature Data Extraction

- Tool Selection: Employ Python libraries (e.g.,

BeautifulSoup,Scrapy,selenium) or dedicated API clients (e.g., for Springer Nature, Elsevier) for systematic retrieval. - Search Strategy: Use precise Boolean queries targeting polymer matrices (e.g., epoxy, polypropylene), filler types (e.g., graphene oxide, halloysite nanotubes, carbon black), and property keywords.

- Entity Recognition: Implement Named Entity Recognition (NER) models trained on materials science text (using spaCy or ChemDataExtractor) to identify polymer names, filler compositions (wt%, vol%), and numerical property values from full-text and tables.

- Normalization: Convert all extracted property values to standard SI units (MPa, GPa, °C).

- Provenance Logging: Create a metadata table recording source DOI, extraction date, and any assumptions made during parsing.

Data Curation and Cleaning

Raw extracted data requires rigorous validation and imputation.

Table 1: Common Data Quality Issues & Resolution Protocols

| Issue Category | Example | Resolution Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Missing Values | Filler aspect ratio not reported for a composite. | 1. Delete: Remove entry if critical feature (e.g., filler loading) is missing.2. Impute: Use domain-based imputation (e.g., median aspect ratio for that filler type) or model-based imputation (k-NN). Flag imputed values. |

| Unit Inconsistency | Strength reported in psi, MPa, or N/mm². | Apply conversion factors during ingestion. Store only canonical (SI) units. |

| Synonymy & Typography | "Graphene oxide," "GO," "graphene oxide (GO)". | Create a controlled vocabulary. Map all variations to a standard term (e.g., "GO"). |

| Outlier Detection | A reported tensile strength value is 5x higher than peer entries for similar composition. | Apply statistical methods (IQR, Z-score) coupled with domain knowledge. Verify against theoretical bounds (e.g., Rule of Mixtures) before exclusion. |

Protocol 2.2.1: Outlier Validation Workflow

- Calculate Z-scores for key numerical columns (e.g., tensile strength).

- Flag records where |Z-score| > 3.

- For each flagged record, perform a manual literature cross-check.

- If unsupported, move record to a separate "anomaly" table, preserving it without use in primary training.

Feature Engineering for Composite Materials

Domain-Informed Feature Construction

Moving beyond raw compositional data, engineered features encapsulate materials science principles.

Table 2: Engineered Feature Catalog for Polymer Composites

| Feature Category | Example Features | Calculation & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Geometric | Filler Aspect Ratio, Specific Surface Area, Sphericity | From manufacturer specs or microscopy image analysis. Critical for reinforcement efficiency. |

| Interfacial | Theoretical Interface Area, Filler Packing Fraction | Interface Area ≈ Filler SSA * Filler Mass / Composite Density. Influences stress transfer. |

| Composite Theory | Rule of Mixtures Upper/Lower Bound, Halpin-Tsai Prediction | Provides a physics-based baseline. AI model can learn deviations due to interface quality. |

| Processing | Shear Rate During Mixing, Curing Temperature Gradient | Extracted from method descriptions. Dictates filler dispersion and matrix morphology. |

| Filler Chemistry | Oxygen/Carbon Ratio (for GO), Surface Functional Group Density | From XPS or FTIR literature data. Impacts matrix-filler adhesion. |

Protocol for Feature Calculation: Halpin-Tsai Features

The Halpin-Tsai equations provide semi-empirical estimates for composite modulus, serving as an excellent baseline feature.

Protocol 3.2.1: Generating Halpin-Tsai Estimator Features

- Objective: Calculate predicted tensile modulus (EpredHT) for use as an input feature.

- Inputs:

- ( Em ): Tensile modulus of matrix polymer (GPa).

- ( Ef ): Tensile modulus of filler (GPa).

- ( \xi ): Shape factor (ξ = 2 * (filler aspect ratio) for modulus).

- ( \phi_f ): Filler volume fraction.

- Procedure:

- Calculate the parameter ( \eta ): ( \eta = \frac{(Ef / Em) - 1}{(Ef / Em) + \xi} )

- Calculate the Halpin-Tsai prediction: ( E{pred_HT} = Em \frac{1 + \xi \eta \phif}{1 - \eta \phif} )

- Append ( E_{pred_HT} ) and the intermediate variable ( \eta ) as new columns to the dataset.

- Note: This prediction becomes a feature for the AI model, which then learns to predict the actual experimental modulus, potentially correcting for interface effects not captured by Halpin-Tsai.

Diagram 1: Feature Engineering Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials & Tools for Data-Centric Composite Research

| Item | Function in Data Generation/Curration |

|---|---|

| High-Throughput Mixing & Casting System (e.g., dual-screw compounder with automated feed) | Generates consistent, large-scale processing data under varying parameters (shear, temperature). |

| Automated Tensile Tester with Digital Image Correlation (DIC) | Produces rich, structured mechanical property data (stress-strain curves, modulus, Poisson's ratio) directly to digital format. |

| Controlled Vocabulary & Ontology (e.g., based on IUPAC, Polymer Ontology) | Standardizes material names and properties during data entry, preventing synonymy issues at source. |

| Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) with API Access | Captures experimental parameters (masses, settings, observations) in structured fields, enabling direct export to databases. |

| Materials Database Software (e.g., Citrination, PUMA) | Provides a dedicated schema for storing material compositions, processing conditions, and measured properties in a linked, queryable format. |

Protocol: Constructing an AI-Ready Dataset

Protocol 5.1: End-to-End Data Pipeline

- Aggregation: Execute Protocol 2.1.1 for target literature. Import internal experimental data from ELN/DB.

- Curation: Run data through cleaning procedures defined in Table 1 and Protocol 2.2.1.

- Feature Engineering: For each composite record, calculate the relevant features from Table 2 (e.g., follow Protocol 3.2.1).

- Vectorization: Encode categorical variables (e.g., matrix type, filler family) using one-hot or target encoding. Scale all numerical features (e.g., using RobustScaler).

- Splitting: Perform a stratified split on a key property (e.g., filler type loading) to ensure training and test sets represent the full compositional range. Never split randomly for material data due to risk of data leakage.

- Versioning & Storage: Save the final feature matrix (X), target vector(s) (y, e.g., strength), and metadata using a versioned system (e.g., DVC, Git LFS) with clear identifiers.

Diagram 2: AI-Ready Data Pipeline

Robust data curation and insightful feature engineering are the foundational steps in building reliable AI models for polymer composite design. By implementing these standardized protocols, researchers can transform disparate, noisy material data into structured, knowledge-rich datasets that enable accurate predictive modeling for filler selection and optimization.

1. Introduction and Thesis Context This application note details methodologies for predictive model selection within a broader research thesis focused on AI-driven polymer composite filler selection and optimization. The primary objective is to identify and characterize high-performance composite materials for applications ranging from structural components to specialized drug delivery systems. Accurate prediction of key properties (e.g., tensile strength, modulus, permeability, degradation rate) based on filler characteristics (type, size, morphology, surface chemistry, loading percentage) and processing parameters is critical for accelerating material discovery. This document provides a comparative framework and experimental protocols for implementing and validating three foundational modeling paradigms: classical regression, ensemble-based Random Forests, and Neural Networks.

2. Model Comparison & Data Presentation The following table summarizes the core characteristics, performance, and applicability of each modeling approach for material property prediction, based on current literature and typical experimental outcomes in materials informatics.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Predictive Modeling Techniques for Material Properties

| Aspect | Linear/Multiple Regression | Random Forest (Ensemble) | Neural Network (Deep Learning) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Models linear relationship between independent variables and target. | Ensemble of decision trees; output is mode (classification) or mean (regression) of individual trees. | Interconnected layers of nodes (neurons) that transform input data through non-linear activation functions. |

| Interpretability | High. Provides clear coefficients for each feature. | Moderate. Feature importance is available, but internal logic is opaque. | Low. "Black box" model; difficult to interpret learned relationships. |

| Handling Non-linearity | Poor. Requires manual feature engineering. | Excellent. Inherently captures non-linear and interaction effects. | Excellent. Highly flexible function approximator. |

| Data Efficiency | High. Effective with small datasets (10s-100s of samples). | Moderate to High. Requires more data than regression but less than deep learning. | Low. Requires large datasets (1000s+ samples) for robust generalization. |

| Typical R² Range (Composite Prop.) | 0.3 - 0.7 | 0.6 - 0.9 | 0.7 - 0.95+ |

| Key Hyperparameters | Regularization (Ridge/Lasso) strength. | Number of trees, tree depth, features per split. | Layers & neurons, learning rate, activation functions, epochs. |

| Best Suited For | Screening experiments, establishing baseline trends, highly linear systems. | Robust prediction with medium-sized datasets, identifying critical feature importance. | Complex, high-dimensional relationships with abundant, consistent data. |

3. Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Data Curation and Feature Engineering for Filler-Composite Datasets Objective: To construct a clean, structured dataset for model training from experimental records. Materials: Experimental literature databases (e.g., SciFinder, PubMed), laboratory notebooks, computational chemistry outputs (e.g., molecular descriptors). Procedure:

- Data Collection: Extract quantitative data on filler properties (primary particle size, aspect ratio, specific surface area, zeta potential), composite formulation (filler wt.%, matrix type, additives), processing conditions (mixing speed/time, curing temperature/pressure), and resulting material properties (Young's modulus, tensile strength, thermal conductivity).

- Feature Encoding: Encode categorical variables (e.g., filler type: graphene oxide, carbon nanotube, silica) using one-hot encoding.

- Normalization: Apply min-max scaling or standard (Z-score) normalization to all numerical features to ensure equal weighting during model training.

- Train-Test-Validation Split: Randomly partition the dataset into training (70%), validation (15%), and hold-out test (15%) sets. The validation set is used for hyperparameter tuning.

Protocol 3.2: Implementation and Training of a Random Forest Regressor Objective: To train a Random Forest model for predicting a target composite property. Materials: Python environment with scikit-learn library (v1.3+), curated dataset from Protocol 3.1. Procedure:

- Initialize Model: Instantiate a

RandomForestRegressorfromsklearn.ensemble. - Hyperparameter Grid: Define a search grid for key parameters:

n_estimators(e.g., [100, 300, 500]),max_depth(e.g., [10, 30, None]),min_samples_split(e.g., [2, 5, 10]). - Cross-Validation Tuning: Perform a RandomizedSearchCV or GridSearchCV using the training set and the validation strategy, optimizing for the

neg_mean_squared_errororr2score. - Model Training: Train the final model with the optimal hyperparameters on the combined training and validation set.

- Evaluation: Predict on the held-out test set and report key metrics: R², Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE).

Protocol 3.3: Design and Training of a Fully Connected Neural Network Objective: To construct and train a feedforward neural network for property prediction. Materials: Python with TensorFlow/Keras (v2.13+) or PyTorch (v2.0+), normalized dataset. Procedure:

- Architecture Design: Define a sequential model. Start with an Input layer matching the number of features. Add 2-4 Dense hidden layers with decreasing neurons (e.g., 128, 64, 32), using ReLU activation. Include Dropout layers (rate=0.2-0.5) to prevent overfitting. End with a single-neuron output layer (linear activation for regression).

- Compilation: Compile the model using the

Adamoptimizer andMeanSquaredErrorloss function. MonitorMeanAbsoluteErroras a metric. - Training with Early Stopping: Fit the model to the training data, using the validation set for evaluation. Implement

EarlyStoppingcallback to halt training if validation loss does not improve for 20-50 epochs. - Evaluation & Prediction: Evaluate the final model on the test set. Use the model to predict properties for novel, unseen filler combinations.

4. Mandatory Visualizations

Title: AI-Driven Material Property Prediction Workflow

Title: Random Forest Ensemble Prediction Mechanism

5. The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Computational Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for AI-Enabled Composite Research

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Matrix Library | Provides the continuous phase for composites; variation enables study of matrix-filler interactions. | Epoxy resins, Polylactic acid (PLA), Polyethylene glycol (PEG). |

| Functionalized Filler Library | Discrete fillers with controlled properties (size, surface chemistry) are the independent variables for modeling. | Carboxylated CNTs, Aminated silica nanoparticles, Graphene oxide sheets. |

| Mechanical Testers | Generate quantitative target variables (e.g., modulus, strength) for model training and validation. | Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer (DMA), Universal Testing Machine (UTM). |

| Scikit-learn Library | Open-source Python library providing robust, easy-to-use implementations of regression and Random Forest algorithms. | sklearn.linear_model, sklearn.ensemble. |

| TensorFlow/PyTorch | Open-source frameworks for building, training, and deploying neural network models. | tf.keras.Sequential, torch.nn.Module. |

| Hyperparameter Optimization Tools | Automates the search for optimal model settings, saving researcher time and improving performance. | Optuna, scikit-learn's GridSearchCV. |

| Chemical Descriptor Software | Computes quantitative features (e.g., molecular weight, polarity) from filler chemical structures for models. | RDKit, Dragon software. |

The optimization of polymer composites for applications ranging from lightweight structural components to drug delivery systems hinges on the precise engineering of filler-matrix interactions. Within the broader thesis on AI-driven filler selection, this document focuses on Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) as a transformative architecture for modeling these complex, non-linear interactions. Unlike traditional machine learning models that treat composite formulations as vectorized data, GNNs operate directly on the inherent graph structure of a composite system. In this representation, nodes correspond to atoms, functional groups, or filler particles, while edges encode chemical bonds, spatial proximities, or interfacial forces. This allows for the explicit learning of structure-property relationships, enabling the in-silico prediction of key properties such as tensile strength, modulus, thermal conductivity, and drug release kinetics based solely on molecular and mesoscale descriptors.

Foundational Concepts: GNNs for Material Graphs

A GNN's core operation is message passing, where node features are iteratively updated by aggregating information from their neighbors. For a composite, a node ( v ) (e.g., a silica nanoparticle) at layer ( k ) has a hidden state ( h_v^{(k)} ). Its update is given by:

[ hv^{(k)} = \text{UPDATE}^{(k)}\left(hv^{(k-1)}, \text{AGGREGATE}^{(k)}\left({h_u^{(k-1)}, \forall u \in \mathcal{N}(v)}\right)\right) ]

where ( \mathcal{N}(v) ) are the neighbors of ( v ). Common variants like Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) or Graph Attention Networks (GATs) can be specialized to capture specific filler-matrix interaction energies, adhesion strengths, or interfacial phonon scattering.

Application Notes: Predictive Modeling of Composite Properties

Data Curation and Graph Construction

The primary challenge is constructing meaningful graph representations (material graphs) from experimental or simulation data.

Protocol 3.1: Constructing a Filler-Matrix Interaction Graph from Molecular Dynamics (MD) Trajectories

- Objective: To create a graph representation of a composite system for GNN training from all-atom or coarse-grained MD simulations.

- Input: MD trajectory files (e.g., .xtc, .dcd) and topology file for a system containing polymer chains and filler particles.

- Procedure:

- Frame Selection: Sample representative snapshots from the equilibrated portion of the trajectory.

- Node Definition: Define nodes as either (a) individual filler particles, or (b) polymer beads/residues within a cutoff radius (e.g., 1 nm) from any filler surface. Assign initial node features: for filler nodes - radius, surface chemistry code; for polymer nodes - residue type, partial charge, local polarity.

- Edge Definition: Connect nodes with an edge if the inter-atomic distance is below an interaction-specific cutoff (e.g., 0.5 nm for van der Waals, 0.3 nm for hydrogen bonding). Assign edge features: distance, calculated interaction energy from a force field, bond type indicator.

- Global Graph Attribute: Assign the target property (e.g., computed tensile modulus from MD, experimental glass transition temperature shift) as a graph-level label.

- Output: A set of graph objects (compatible with PyTorch Geometric or DGL libraries) for model training.

Model Architecture Selection and Training

Table 1: Comparison of GNN Architectures for Filler-Matrix Modeling

| Architecture | Core Mechanism | Advantage for Composites | Typical Output Layer | Applicable Property Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCN | Spectral graph convolution | Computationally efficient for homogeneous filler dispersion. | Graph Readout (Pooling) + MLP | Bulk modulus, electrical conductivity. |

| GAT | Attention-weighted aggregation | Learns importance of specific polymer-filler contacts. | Graph Readout + MLP | Interfacial strength, fracture toughness. |

| Message Passing Neural Network (MPNN) | Generalizable message function | Can incorporate custom physical equations (e.g., Lennard-Jones). | Graph Readout + MLP | Interaction energy, binding affinity for drug-loaded fillers. |

| Graph Isomorphism Network (GIN) | Sum aggregation, MLP update | Powerful for distinguishing topological structures of grafted fillers. | Graph Readout + MLP | Viscosity, dispersion stability. |

Protocol 3.2: Training a GAT for Predicting Interfacial Shear Strength (IFSS)

- Objective: Train a model to predict the IFSS of a silica nanoparticle-polyethylene composite from its graph representation.

- Dataset: 500 material graphs generated via Protocol 3.1, with IFSS labels from molecular mechanics calculations.

- Model Specification:

- GAT Layers: 3 layers with 256, 128, 64 hidden channels respectively. Attention heads: 4.

- Readout: Global mean + max pooling of node features.

- Prediction Head: 2-layer MLP (64 → 16 → 1 neuron).

- Training: Adam optimizer (lr=0.001), Mean Squared Error loss, 80/10/10 train/validation/test split, early stopping.

- Validation: Monitor R² score and Mean Absolute Error on the validation set. Use SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) on the trained model to identify critical sub-graph motifs (e.g., specific chemical groups near the interface) that contribute most to high IFSS.

Experimental Validation Protocol

Protocol 4.1: Validating GNN Predictions via Nano-Indentation on Composite Films

- Objective: Experimentally measure mechanical properties predicted by the GNN model.

- Materials: (See Scientist's Toolkit below).

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare thin films of polymer (e.g., PMMA) with GNN-optimized loadings of functionalized graphene oxide (GO) filler via solution casting.

- Nano-Indentation: Using a nanoindenter with a Berkovich tip, perform a grid of 25 indents on each film. Use the Oliver-Pharr method to extract reduced modulus (Er) and hardness (H) from the unloading curve.

- Data Correlation: Compare the experimental distribution of Er and H to the GNN's prediction range. Perform statistical analysis (t-test) to confirm predictions fall within the 95% confidence interval of measurements.

- Key Output: A validation table comparing predicted vs. measured modulus and hardness.

Visualizations

Title: GNN Workflow in Composite AI Thesis

Title: GNN Message Passing on Composite Graph

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents & Materials for Filler-Matrix GNN Validation

| Item | Function/Description | Example Product/Chemical |

|---|---|---|

| Functionalized Filler | Core reinforcement phase; surface chemistry is a key node feature. | Aminated silica nanoparticles, Carboxylated graphene oxide. |

| Polymer Matrix | Continuous phase; source of polymer node features. | Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), Polyethylene glycol (PEG). |

| Solvent for Dispersion | For preparing homogeneous filler-polymer mixtures. | Tetrahydrofuran (THF), Dimethylformamide (DMF). |

| Coupling Agent | Alters interfacial interactions, modifying edge features in the graph. | (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES). |

| Nano-Indenter | Validates GNN-predicted mechanical properties at the micro-scale. | Keysight G200, Hysitron TI 950. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Generates training data for graph construction. | GROMACS, LAMMPS, Materials Studio. |

| GNN Framework | Library for building and training graph models. | PyTorch Geometric, Deep Graph Library (DGL). |

Application Note APN-001: Multi-Objective Optimization in Polymer Composite Design

1.0 Thesis Context Integration This application note is developed within the broader thesis framework "AI-Driven Paradigm for Integrated Selection and Multi-Objective Optimization of Polymer Composite Fillers." The core challenge is navigating the high-dimensional, non-linear property space where filler selection (e.g., carbon nanotubes, graphene, silica, calcium carbonate) dictates often antagonistic performance metrics. AI/ML models are trained to predict Pareto fronts, identifying optimal trade-offs impossible to intuit manually.

2.0 Quantitative Data Summary: Property Trade-Offs

Table 1: Common Filler Systems & Their Impact on Conflicting Properties

| Filler Type | Primary Property Enhanced | Conflicting Property Compromised | Typical Quantitative Trade-off Example | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Electrical Conductivity (σ) | Melt Processability/Viscosity (η) | σ > 10 S/cm at 3 wt% leads to η increase > 200% vs. neat polymer. | Formation of conductive percolating network impedes chain mobility. |

| Graphene Nanoplatelets (GNPs) | Tensile Strength (σ_t) | Fracture Toughness (K_IC) | σt increase by 100% at 5 wt% can lead to KIC decrease by 40%. | High aspect ratio plates create stress concentration sites, promoting brittle fracture. |

| Spherical Silica | Young's Modulus (E) | Impact Strength | E increase by 150% at 20 vol% can reduce Izod impact strength by 30%. | Rigid, non-deformable particles restrict plastic deformation of matrix. |

| Calcium Carbonate (low-cost) | Material Cost & Stiffness | Tensile Strength & Toughness | Cost reduction >25% at 30 wt% filler loading, but σ_t and elongation at break may drop >50%. | Poor interfacial adhesion and particle agglomeration lead to defect sites. |

Table 2: Multi-Objective Optimization Targets for Select Applications

| Target Application | Primary Objective 1 | Primary Objective 2 | Constraint | AI-Optimization Goal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lightweight Automotive Bracket | Maximize Specific Stiffness (E/ρ) | Maximize Impact Toughness | Cost < $5/kg | Find Pareto-optimal blend of short glass fiber & rubber particles. |

| Electrostatic Dissipative Packaging | Surface Conductivity > 10^-6 S/sq | Maintain Tensile Elongation > 20% | Optical Clarity (Haze < 10%) | Optimize type, coating, and dispersion of conductive nanowire network. |

| Biomedical Implant | Biocompatibility & Modulus Match Bone | Wear Resistance | Must Not leach ions | Optimize ceramic (e.g., hydroxyapatite) filler size, shape, and volume fraction. |

3.0 Experimental Protocols

Protocol PRO-01: Mapping the Strength-Toughness Pareto Front for Epoxy-Silica Composites Objective: To experimentally determine the Pareto-optimal frontier for tensile strength vs. fracture toughness. Materials: See Scientist's Toolkit. Workflow:

- Composite Fabrication: Prepare epoxy-silica composites with silica volume fractions (φ) of 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, 20% using a high-shear mixer (2000 rpm, 30 min) followed by sonication (30 min, pulse mode).

- Casting & Cure: Degas mixtures in a vacuum chamber, pour into dog-bone (ASTM D638) and compact tension (ASTM D5045) molds. Cure at 120°C for 2 hours.

- Tensile Testing: Test 5 dog-bone specimens per φ at a crosshead speed of 1 mm/min. Record ultimate tensile strength (σ_t).

- Fracture Toughness Testing: Pre-crack compact tension specimens via razor tapping. Test at 10 mm/min. Calculate plane-strain fracture toughness (K_IC).

- Data Analysis: Plot σt vs. KIC for all φ. The Pareto front comprises points where no increase in one property is possible without decreasing the other.

Protocol PRO-02: Optimizing Conductivity-Cost Trade-off in Conductive Thermoplastics Objective: To identify the cost-effective conductive filler loading for a target conductivity. Materials: Polypropylene (PP), Carbon Black (CB), Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs). Workflow:

- Design of Experiments (DoE): Create a mixture design for PP/CB/MWCNT. Total filler loading ranges from 1-7 wt%.

- Melt Compounding: Compound blends using a twin-screw extruder with a controlled temperature profile.

- Injection Molding: Produce discs for electrical testing.

- Property Measurement: Measure volume resistivity (Ω·cm) via four-point probe. Calculate conductivity (σ).

- Cost Calculation: Compute raw material cost/kg for each formulation based on current market prices (CB ~$5/kg, MWCNT ~$50/kg).

- AI Model Input: Use (σ, cost) data pairs to train a surrogate model (e.g., Gaussian Process) to predict the full Pareto front, identifying the minimal-cost formulation for any target σ.

4.0 Visualization of Methodologies

Diagram Title: Strength-Toughness Pareto Front Mapping Workflow

Diagram Title: AI-Driven Multi-Objective Optimization Loop

5.0 The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Multi-Objective Composite Studies

| Item/Category | Example Product/Specification | Primary Function in Optimization Research |

|---|---|---|

| High-Aspect-Ratio Conductive Fillers | MWCNTs (Diameter: 9-15 nm, Length: 5-20 µm), GNPs (Thickness: 6-8 nm, Diameter: 5-10 µm) | Enable percolation networks at low loading; key variables for conductivity-strength-toughness trade-offs. |

| Surface Modification Agents | (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES), Polyethylene-graft-maleic anhydride (PE-g-MA) | Modify filler-matrix interface adhesion, directly impacting stress transfer (strength) and energy dissipation (toughness). |

| Model Polymer Matrices | Epoxy (Diglycidyl ether of bisphenol-A), Polypropylene (Isotactic), Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Provide consistent, well-characterized base materials for isolating filler effects and benchmarking AI predictions. |

| Dispersive Processing Aids | Ultrasonic Cell Disruptor (with cup horn), Three-Roll Mill, High-Shear Twin-Screw Extruder | Achieve homogeneous filler dispersion, critical for reproducible property measurements and valid model training. |

| Characterization Standards | ASTM D638 (Tensile), ASTM D5045 (Fracture), ASTM D257 (Resistivity), ISO 179 (Impact) | Provide standardized protocols for generating reliable, comparable quantitative data for the objective space. |

This case study is presented within the broader research thesis: "AI-Driven Multi-Objective Optimization for Polymer Composite Filler Selection in Biomedical Applications." The thesis posits that artificial intelligence can navigate the complex, high-dimensional parameter space of composite biomaterials to identify optimal formulations that balance mechanical properties, drug release kinetics, biocompatibility, and degradation profiles. Here, we demonstrate the application of an AI-guided workflow to design a poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA)-based composite scaffold for the sustained release of dexamethasone to modulate osteogenesis.

Table 1: AI-Predicted vs. Experimentally Validated Properties of Top Scaffold Formulations

| Formulation ID (AI-Generated) | PLGA Ratio (LA:GA) | Filler Type & wt% | Dexamethasone Load (wt%) | Predicted Compressive Modulus (MPa) | Experimental Modulus (MPa) | Predicted Burst Release (Day 1, %) | Experimental Burst Release (%) | Predicted Osteogenic Score (AI Metric) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AID-07 | 75:25 | nHA, 15% | 2.0 | 142 | 138 ± 12 | 18 | 22 ± 3 | 0.89 |

| AID-12 | 85:15 | BG (4555), 10% | 1.5 | 98 | 105 ± 9 | 15 | 17 ± 2 | 0.92 |

| AID-03 | 50:50 | nHA, 20% | 3.0 | 165 | 158 ± 15 | 30 | 35 ± 4 | 0.76 |

Table 2: In Vitro Biological Response (Day 14) for Lead Formulation AID-12

| Cell Line / Assay | Control (PLGA only) | AID-12 Scaffold | Significance (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| hMSC Viability (AlamarBlue) | 100% ± 8 | 156% ± 10 | < 0.001 |

| ALP Activity (nmol/min/µg) | 12.3 ± 1.5 | 45.6 ± 3.2 | < 0.001 |

| OPN Gene Expression (Fold) | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 8.7 ± 0.9 | < 0.001 |

| TNF-α Secretion (pg/mL) | 220 ± 30 | 85 ± 15 | < 0.01 |

AI Model & Workflow Protocol

Protocol 3.1: AI Training and Scaffold Design Workflow

- Objective: To train a surrogate model for predicting scaffold properties and to generate optimal formulations.

- Materials: Historical dataset (literature-mined & in-house) of ~500 composite scaffold entries with features (polymer type, Mw, filler identity/size/loading, drug load, processing method) and outcomes (mechanical properties, release profile, cell viability).

- Procedure:

- Data Curation: Clean and standardize dataset. Normalize numerical features. Encode categorical features (e.g., filler type) using one-hot encoding.

- Model Training: Implement a Gradient Boosting Regressor (e.g., XGBoost) ensemble. Split data 80/20 for training/testing. Use 5-fold cross-validation on the training set. Optimize hyperparameters (learning rate, max depth, n_estimators) via Bayesian optimization.

- Multi-Objective Optimization: Define objectives: Maximize Compressive Modulus (>100 MPa), minimize Day 1 Burst Release (<20%), and maximize a calculated Osteogenic Potential score (derived from ALP and mineralization data). Use the NSGA-II (Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II) to explore the formulation space.

- Pareto Front Analysis: Identify the set of non-dominated optimal formulations from the NSGA-II output. Select 3 candidate formulations (AID-07, AID-12, AID-03) for experimental validation based on clustering along the Pareto front.

Experimental Synthesis & Characterization Protocols

Protocol 4.1: Scaffold Fabrication via Thermally Induced Phase Separation (TIPS)

- Objective: Synthesize porous composite scaffolds based on AI-generated formulations.

- Materials: PLGA (specified LA:GA ratio), Nano-hydroxyapatite (nHA) or Bioglass 4555 (BG), Dexamethasone, 1,4-Dioxane.

- Procedure:

- Weigh PLGA (1g total polymer) and dissolve in 10 mL of 1,4-dioxane in a glass vial. Stir at 50°C until fully dissolved.

- Add the specified weight percentage of filler (nHA or BG) to the solution. Sonicate in an ice bath for 30 minutes (5s pulse, 5s rest) to achieve homogeneous dispersion.

- Add dexamethasone (as % of polymer weight) to the suspension and stir magnetically for 1 hour in the dark.

- Pour the homogeneous suspension into a pre-chilled (-20°C) Teflon mold.

- Quench the mold at -80°C for 4 hours to induce solid-liquid phase separation.

- Transfer the mold to a freeze-dryer. Lyophilize at -50°C and <0.1 mbar for 48 hours to remove the solvent.

- Cut scaffolds into 8mm diameter x 3mm thick disks for characterization.

Protocol 4.2: In Vitro Drug Release Kinetics

- Objective: Quantify dexamethasone release profile in simulated physiological conditions.

- Materials: Scaffold disks, Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, pH 7.4) with 0.1% w/v sodium azide, shaking incubator, HPLC system.

- Procedure:

- Weigh each scaffold disk (W0) and immerse in 5 mL of release medium in a 15 mL centrifuge tube. Incubate at 37°C, 60 rpm.

- At predetermined time points (1, 3, 6, 12, 24h, then daily for 28 days), remove and replace the entire release medium.

- Analyze the collected medium for dexamethasone concentration using HPLC (C18 column, mobile phase: 45:55 v/v acetonitrile:water, flow: 1.0 mL/min, detection: 242 nm).

- Calculate cumulative drug release as a percentage of the total loaded drug (determined from a separate scaffold dissolved in DMSO).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for AI-Guided Scaffold Research

| Item & Example Supplier | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| PLGA Copolymers (e.g., Lactel Absorbables) | The biodegradable polymer matrix. LA:GA ratio controls degradation rate and mechanical properties. |

| Nano-Hydroxyapatite (nHA) (e.g., Sigma-Aldrich) | Bioactive ceramic filler. Enhances compressive modulus, provides osteoconductivity, and can modulate drug release via adsorption. |

| Bioglass 4555 (BG) (e.g., Mo-Sci Corp) | Bioactive glass filler. Dissolves to release ions (Ca, P, Si) that stimulate osteogenesis and vascularization. |

| Model Osteogenic Drug: Dexamethasone (e.g., Cayman Chemical) | A glucocorticoid used to induce osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. |

| 1,4-Dioxane (HPLC Grade) | Solvent for TIPS process. Must be thoroughly removed via lyophilization due to toxicity. |

| hMSCs, Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells (e.g., Lonza) | Primary cell line for in vitro biocompatibility and osteogenic differentiation assays. |

| AlamarBlue Cell Viability Reagent (e.g., Thermo Fisher) | Resazurin-based assay for quantifying metabolic activity and cytotoxicity of scaffold extracts. |

| pNPP Alkaline Phosphatase Assay Kit (e.g., Abcam) | Colorimetric assay to measure ALP activity, a key early marker of osteogenic differentiation. |

Overcoming Data Scarcity and Model Pitfalls in AI-Driven Material Science

Application Notes

In the domain of AI for polymer composite filler selection and optimization, acquiring large, labeled datasets for novel filler chemistries or complex multi-property targets is a fundamental bottleneck. This small data problem stifles the development of accurate predictive models. Two synergistic strategies—Active Learning (AL) and Transfer Learning (TL)—offer robust solutions. AL intelligently selects the most informative data points for experimental labeling, maximizing model performance with minimal data. TL leverages knowledge from related, data-rich source domains (e.g., established polymer-filler databases or molecular simulations) to bootstrap models in the target domain with scarce data.

The integration of these strategies enables rapid, cost-effective AI-driven discovery cycles. For instance, a TL model pre-trained on a vast dataset of carbon nanotube composites can be fine-tuned with a small, actively acquired dataset targeting novel boron nitride nanotube composites for thermal management.

Protocol 1: Combined Transfer and Active Learning for Filler Property Prediction

Objective: To develop a predictive model for a target property (e.g., tensile strength) of a new polymer-filler system with less than 100 available data points.

Materials & Workflow:

Phase 1: Transfer Learning Initialization

- Source Model Training: Utilize a large, public dataset (e.g., NIST Polymer Database, Citrination datasets) containing property data for analogous composites. Train a base neural network model (e.g., Graph Neural Network for filler morphology, or a dense network for engineered features).

- Model Adaptation: Remove the final prediction layer of the pre-trained source model. Replace it with a new, randomly initialized layer(s) suited to the target property. Freeze the weights of all but the last 1-2 layers of the network.

Phase 2: Active Learning Cycle

- Pool-Based Sampling: From the unlabeled target domain pool (e.g., 500 formulated but untested composites), use the adapted TL model to predict properties and their uncertainty (e.g., using Monte Carlo Dropout or ensemble variance).

- Query Strategy: Apply an acquisition function (e.g., Maximum Uncertainty, Expected Improvement) to rank the pool samples. Select the top n (e.g., n=5) most "informative" samples for experimental validation.

- Experimental Labeling: Synthesize and test the selected composites using standard ASTM protocols (e.g., ASTM D638 for tensile strength) to obtain ground-truth labels.

- Model Update: Add the newly acquired data to the training set. Fine-tune the unfrozen layers of the TL model on this expanded dataset.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 3-6 until a predefined performance threshold or labeling budget is reached.

Diagram: TL & AL Integrated Workflow

Quantitative Data Summary

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Learning Strategies on Small Composite Datasets (<100 samples)

| Strategy | Avg. Mean Absolute Error (MAE) Reduction vs. Random Sampling | Avg. Data Required for Target Performance | Key Advantage | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Sampling (Baseline) | 0% | 100% | Simplicity | Very large available pools |

| Active Learning (AL) Only | 25-40% | 40-60% | Optimal experimental design | Novel systems with no prior data |

| Transfer Learning (TL) Only | 30-50% | 30-50% | Strong initial prior | Target domain related to rich source |

| Combined TL+AL | 50-70% | 20-40% | Synergistic efficiency | Novel systems with analogous data |

Table 2: Example Application: Predicting Tensile Modulus of Silica-Filled Elastomers

| Experiment Stage | Data Source (Samples) | Model Type | R² Score (Hold-out Test Set) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source Model | Public filler database (5000) | DNN | 0.88 (on source data) |

| TL Initialization | Target pool (0) | Fine-tuned DNN | 0.45 (prior only) |

| After 1st AL Cycle | +10 actively acquired | Fine-tuned DNN | 0.68 |

| After 4th AL Cycle | +40 actively acquired | Fine-tuned DNN | 0.85 |

Protocol 2: Few-Shot Learning for Filler Morphology Classification from SEM Images

Objective: To classify scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of a new filler type (e.g., cellulose nanocrystals) into morphological categories with very few labeled examples per class (<5).

Experimental Protocol:

- TL Feature Extraction: Use a convolutional neural network (CNN) like ResNet-50 pre-trained on ImageNet. Remove the classification head and use the convolutional base as a fixed feature extractor.

- Support & Query Sets: For each learning episode, randomly select N classes (e.g., 3 classes: "agglomerated," "dispersed," "network"). From each class, select K labeled images (e.g., K=3) as the support set. Use a separate set of images from the same N classes as the query set.

- Prototype Computation: For each of the N classes, compute the mean vector (prototype) of the embedded support set images.

- Distance-Based Classification: For each query image embedding, calculate the Euclidean (or cosine) distance to each of the N class prototypes. Assign the query image to the class with the nearest prototype.

- Training: The model is trained via episodic training. The loss (e.g., cross-entropy) is computed on the query set predictions, and gradients are backpropagated to update the embedding network to produce more discriminative features.

Diagram: Few-Shot Learning Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Implementing AL/TL in Composite Research

| Item / Resource | Function & Relevance | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained Model Repositories | Provides source models for Transfer Learning, saving computational cost and time. | ChemBERTa, MATERIALS.io models, TensorFlow Hub, PyTorch Torchvision models for images. |

| Uncertainty Estimation Library | Enables query strategy in Active Learning by quantifying model prediction confidence. | Monte Carlo Dropout (in PyTorch/TF), Ensemble libraries, GPyTorch (Gaussian Processes). |

| High-Throughput (HT) Experimentation Platform | Physically executes the "experimental labeling" step in the AL loop with minimal human intervention. | Automated dispensing robots, parallel micro-compounders, rapid curing systems. |

| Standardized Property Testers | Generates high-fidelity, consistent labels for model training from actively selected samples. | Micro-tensile testers, dynamic mechanical analyzers (DMA), impedance analyzers for dielectric data. |

| AL Query Framework | Implements and compares different acquisition functions for optimal sample selection. | modAL (Python), ALiPy, LibAct. |

| Materials Database (Source) | Acts as the foundational data-rich source domain for pre-training or initializing TL models. | NIST Polymer Database, PolyInfo, Citrination, OQMD. |

Mitigating Overfitting and Ensuring Model Generalizability to Novel Formulations

Within the thesis "AI-Driven Design of Next-Generation Polymer Composite Fillers for Enhanced Drug Delivery," a central challenge is the development of predictive models that remain robust when applied to novel, unseen filler formulations. Overfitting to limited or biased training data severely compromises the translation of in-silico predictions to real-world composite synthesis and performance. This document provides application notes and detailed protocols for mitigating overfitting and rigorously assessing model generalizability in this specific research context.

Core Strategies & Quantitative Comparisons

The following table summarizes principal techniques, their mechanistic role in combating overfitting, and key performance metrics as established in recent literature.

Table 1: Overfitting Mitigation Strategies & Efficacy in Material Informatics

| Strategy | Core Mechanism | Typical Impact on Test MSE (Reported Range) | Best-For Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|

| L1/L2 Regularization | Penalizes large weight coefficients, promoting simpler models. | Reduction of 15-30% vs. baseline. | High-dimensional descriptor spaces (e.g., quantum chemical features). |