Recycling and Reprocessing of Polymers: Degradation Mechanisms and Implications for Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of polymer degradation during recycling and reprocessing, with a specific focus on implications for biomedical and pharmaceutical development.

Recycling and Reprocessing of Polymers: Degradation Mechanisms and Implications for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of polymer degradation during recycling and reprocessing, with a specific focus on implications for biomedical and pharmaceutical development. It explores the fundamental chemical pathways of degradation, including thermal, thermo-mechanical, and enzymatic mechanisms. The content details advanced methodological approaches for characterizing and mitigating degradation, covering both conventional processing and additive manufacturing. It further addresses critical troubleshooting strategies for optimizing polymer stability and performance, and presents validation frameworks for comparing material properties across recycling cycles. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current research to support the development of sustainable, high-performance polymeric materials for clinical applications.

The Science of Polymer Degradation: Mechanisms and Molecular Consequences

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common signs that polymer degradation has occurred during processing?

A: Common signs include color changes, such as yellowing or browning, which can range to black with severe degradation [1] [2]. You may also observe a loss of mechanical properties (e.g., tensile strength), the generation of bubbles in the melt (from moisture-induced hydrolysis), and the presence of black specks or carbonized material, which can lead to nozzle or barrel clogging [1] [2].

Q2: How does thermo-oxidative degradation differ from pure thermal degradation?

A: Thermal degradation is initiated solely by heat, which causes random chain scission or end-chain scission, leading to a reduction in molecular weight [3]. Thermo-oxidative degradation involves the presence of oxygen, which reacts with polymer radicals generated by heat to form peroxy radicals and hydroperoxides [3]. This propagation cycle accelerates the degradation process, leading to more severe chain scission, cross-linking, and the formation of carbonyl groups at a faster rate than thermal degradation alone [3].

Q3: Why are some polymers, like PET or PLA, particularly susceptible to hydrolytic degradation?

A: Polymers such as Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) and Polylactic Acid (PLA) are prone to hydrolytic degradation because their backbones contain functional groups known as ester bonds [4] [3]. These bonds are highly susceptible to cleavage through a reaction with water, especially at elevated temperatures common during processing like extrusion or injection molding [3]. This hydrolysis reaction severs the polymer chains, reducing their molecular weight and compromising material properties.

Q4: What is the impact of multiple processing cycles (e.g., during mechanical recycling) on polymer properties?

A: Each processing cycle subjects the polymer to renewed thermal and shear stresses, which can lead to cumulative degradation [3]. With multiple cycles (as in mechanical recycling), this typically results in a progressive reduction in average molecular weight due to chain scission, a loss of key mechanical properties like impact strength, and a potential change in melt viscosity, making the material increasingly difficult to process and often limiting it to downcycled applications [5] [6] [3].

Q5: What are the key strategies for stabilizing polymers against degradation during processing?

A: Key stabilization strategies include:

- Proper Drying: Removing moisture by drying hygroscopic polymers (e.g., PET, PA, PLA) according to the manufacturer's specifications to prevent hydrolysis [1] [2].

- Optimizing Processing Parameters: Using the lowest feasible melt temperature and minimizing residence time in the barrel to reduce thermal exposure [1] [2].

- Using Stabilizers: Incorporating chemical additives like antioxidants to interrupt the radical propagation cycles of thermo-oxidative degradation [3].

- Preventing Contamination: Ensuring regrind is of high quality and the machine barrel is thoroughly purged to avoid contamination from previously degraded material [1] [2].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Discoloration (Yellowing/Browning) of Polymer During Extrusion

- Possible Cause 1: Excessive barrel temperatures leading to thermal or thermo-oxidative degradation.

- Possible Cause 2: Contamination from previously degraded polymer residue in the barrel or die.

- Solution: Perform a thorough purge of the extruder with a purging compound or a high-flow-rate virgin polymer. Ensure the machine is cleaned properly between experimental runs [1].

- Possible Cause 3: Oxygen presence in the processing environment.

- Solution: If feasible, purge the extruder hopper and feed throat with an inert gas such as nitrogen to create an oxygen-free atmosphere [3].

Problem: Bubble Formation in Extrudate or Printed Part (FFF Additive Manufacturing)

- Possible Cause: Inadequate drying of the polymer, leading to hydrolytic degradation.

- Solution: Dry the polymer feedstock in a suitable oven or hopper dryer according to the material's specific drying guidelines (typically for several hours at a specified temperature). Ensure the dried material is stored in a dry environment or used immediately [1].

Problem: Drastic Drop in Melt Viscosity or Mechanical Strength

- Possible Cause 1: Severe chain scission due to excessive thermo-mechanical degradation from high shear rates.

- Solution: Lower the screw rotation speed. Check screw and barrel for wear that might cause excessive shear. Use a polymer with a higher molecular weight if the application allows [3].

- Possible Cause 2: Overheating or excessive residence time.

- Solution: Review the shot-to-barrel capacity ratio; the shot weight should not be less than 25% of the machine's capacity. Transfer to a machine with a smaller barrel if needed. Optimize the cycle time to reduce residence time [2].

Quantitative Data on Polymer Degradation

Table 1: Bond Dissociation Energies (BDE) for Common Polymer Bonds [3]

| Bond | Aromatic or Heterocyclic BDE (kJ/mol) | Aliphatic BDE (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| C-C | 410 | 284–368 |

| C=C | - | 615 |

| C-H | 427–435 | 381–410 |

| C-O | 448 | 350–389 |

| C-N | 460 | 293–343 |

Table 2: Characteristic Degradation Pathways and Products of Common Polymers [4] [3]

| Polymer | Primary Degradation Pathway | Key Degradation Products |

|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene (PE) | Thermal-Oxidative | Alkanes, Alkenes, Ketones, Carboxylic Acids |

| Polypropylene (PP) | Thermal-Oxidative | Hydrocarbons, Ketones, Aldehydes |

| Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) | Thermal / Thermal-Oxidative | Hydrogen Chloride (HCl), Chlorinated Hydrocarbons |

| Polystyrene (PS) | Thermal / Thermal-Oxidative | Styrene Monomer, Oligomers, Aromatic Hydrocarbons |

| Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) | Hydrolytic | Terephthalic Acid, Ethylene Glycol |

| Polyurethane (PU) | Hydrolytic / Thermal-Oxidative | Polyols, Amines, Carbon Dioxide |

Experimental Protocols for Degradation Analysis

Protocol 1: Assessing Thermo-Oxidative Stability via TGA

Principle: Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) measures the mass change of a sample as a function of temperature under a controlled atmosphere. Using an oxidative atmosphere (e.g., air) allows for the study of thermo-oxidative stability.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare 5-20 mg of polymer sample in powder or small film form.

- Instrument Setup: Load the sample into a platinum or alumina TGA crucible. Set the gas flow to synthetic air (80% N₂, 20% O₂) at a standard flow rate (e.g., 50 mL/min).

- Temperature Program: Run a dynamic heating program from room temperature to 800°C at a constant heating rate (e.g., 10°C/min).

- Data Analysis: Determine the onset degradation temperature (Tₒₙₛₑₜ), which is the temperature at which the sample begins to lose mass, and the temperature at maximum degradation rate (Tₘₐₓ) from the derivative of the TGA curve (DTG). The residue at a high temperature (e.g., 600°C) indicates the inorganic or carbonized content.

Protocol 2: Monitoring Molecular Weight Changes via GPC

Principle: Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC), also known as Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), separates polymer molecules by their hydrodynamic volume, allowing for the determination of average molecular weight (Mₙ, M𝄆) and dispersity (Đ) before and after processing.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve processed and unprocessed (control) polymer samples in an appropriate solvent (e.g., THF for many polymers) at a low concentration (~1-2 mg/mL). Filter the solutions through a 0.45 μm filter to remove any particulates.

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate the GPC system with narrow dispersity polymer standards of known molecular weight that match the polymer under investigation.

- Analysis: Inject the filtered polymer solution into the GPC system. Use a refractive index (RI) detector or another suitable detector.

- Data Analysis: Compare the molecular weight averages and dispersity of the processed sample to the control. A decrease in Mₙ and M𝄆 and a potential change in Đ are clear indicators of chain scission (or, in some cases, cross-linking) due to degradation [3].

Protocol 3: Investigating Hydrolytic Degradation

Principle: This experiment accelerates hydrolytic degradation by exposing the polymer to elevated temperatures in an aqueous environment, simulating long-term effects or processing with residual moisture.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare compression-molded or injection-molded specimens of standardized dimensions (e.g., dumbbells for tensile testing).

- Ageing Process: Place specimens in sealed containers with deionized water or a buffer solution at a controlled pH. Age the samples in an oven at a temperature below the polymer's glass transition temperature (Tg) but sufficiently high to accelerate the reaction (e.g., 60°C or 70°C).

- Periodic Analysis: Remove samples at predetermined time intervals. Dry them to a constant weight in a vacuum oven.

- Characterization:

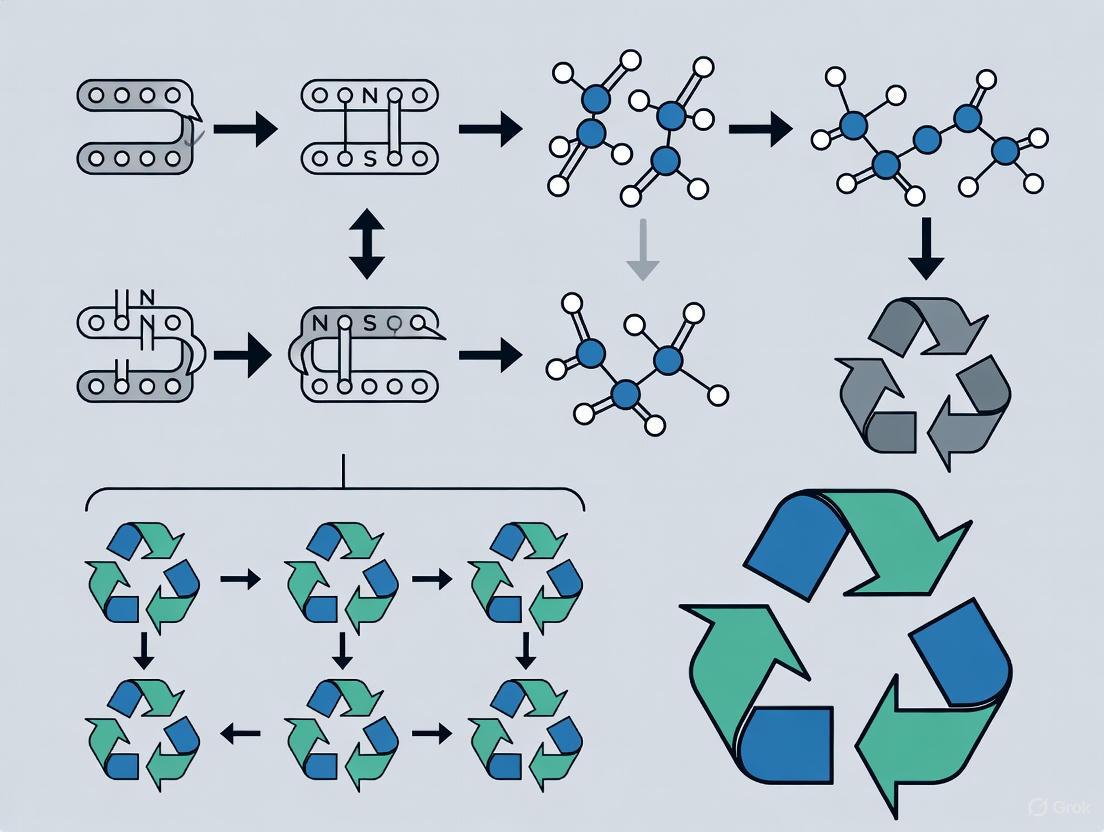

Diagram: Polymer Degradation Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Polymer Degradation and Recycling Research

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Inert Gas (N₂ or Argon) | Creates an oxygen-free atmosphere during processing or in a reactor to suppress thermo-oxidative degradation [3]. |

| Stabilizers (Antioxidants) | Chemical additives that scavenge free radicals or decompose hydroperoxides, inhibiting the propagation of degradation reactions during processing [3]. |

| Purging Compounds | Specialized formulations used to clean extruder and injection molding barrels between material changes or experiments, removing residual and potentially degraded polymer [2]. |

| Selective Solvents | Used in solvent-based recycling (e.g., STRAP, CreaSolv) to selectively dissolve and separate specific polymers from mixed waste, recovering near-virgin quality resins [7]. |

| Compatibilizers | Chemicals used in mechanical recycling of polymer blends to improve interfacial adhesion between immiscible polymers, enhancing the properties of the recycled blend [6]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary molecular-level changes that occur during polymer recycling? During mechanical recycling, polymers are subjected to heat and shear forces, which induce two primary, competing molecular-level changes: chain scission and cross-linking [8] [9]. Chain scission is the breaking of the polymer backbone, leading to a reduction in molecular weight and a decrease in melt viscosity [10] [11]. Cross-linking is the formation of new bonds between polymer chains, which increases molecular weight and can lead to gel formation and increased melt viscosity [8] [11]. The dominant mechanism depends on the polymer type and the processing environment [11].

FAQ 2: How does the presence of oxygen influence degradation pathways? The presence of oxygen significantly shifts the dominant degradation mechanism from chain scission to long-chain branching (LCB) and cross-linking [11]. In an inert atmosphere (e.g., N₂), chain scission tends to dominate [11]. However, in an oxygen-rich environment (air), macroradicals react with O₂ to form stable carbonyl and hydroxyl end groups [11]. These groups can act as radical acceptors, promoting reactions between chains and leading to the formation of long-chain branches [11].

FAQ 3: Why do recycled polymers often exhibit reduced mechanical performance? The reduction in mechanical properties, such as tensile strength and impact resistance, is a direct consequence of molecular-level degradation [10] [9]. Chain scission shortens polymer chains, inherently reducing their strength and ability to bear load [10]. While cross-linking can initially increase stiffness, it often leads to embrittlement, as it reduces the material's ability to plastically deform, resulting in a lower failure strain [8]. Furthermore, the formation of oxidation products (e.g., carbonyls) can also compromise material integrity [11].

FAQ 4: How can I quantitatively track degradation during reprocessing? Rheology is a powerful tool for quantifying degradation without the need for extensive extrusion experiments [11]. Key rheological metrics include:

- Complex Viscosity (η*): A decrease suggests chain scission dominates, while an increase points to cross-linking or long-chain branching [11].

- Van Gurp-Palmen (vGP) Plot: The shape of the curve (phase angle δ vs. complex modulus |G*|) is a qualitative indicator of branching. Increasing curvature and a lower phase angle indicate the formation of long-chain branches [11].

- Modulus Crossover (G' = G"): Changes in the crossover point can be used to estimate changes in molecular weight and polydispersity [11].

Advanced chromatographic techniques like Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) are used to directly measure the reduction in molar mass (Mₙ, M𝄬) and the broadening of dispersity (Ð), providing direct evidence of chain scission [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Severe Loss of Viscosity and Mechanical Strength in Recycled PLA

- Observed Issue: The recycled polymer flows too easily, and the final product is weak and brittle [10].

- Molecular Cause: Dominant chain scission during reprocessing. Hydrolysis at the ester linkage and shear-induced thermal degradation are the primary culprits, leading to a significant reduction in molecular weight [10] [9].

- Solutions:

- Ensure thorough drying of the material before processing to minimize hydrolytic degradation [10] [9].

- Optimize processing parameters: Reduce melt temperature and shear rates (e.g., lower screw speed) to minimize thermal and thermo-mechanical degradation [10] [9].

- Consider using a chain extender," a reactive additive that can reconnect cleaved chains and partially restore molecular weight [12].

Problem: Increased Viscosity, Gel Formation, and Discoloration in Recycled Polyolefins

- Observed Issue: The material is difficult to process, shows signs of cross-linked gels, and has turned yellow or brown [13] [11].

- Molecular Cause: Dominant cross-linking and long-chain branching driven by thermo-oxidative degradation [11]. The presence of oxygen at high processing temperatures leads to the formation of radicals that recombine into branched structures [8] [11].

- Solutions:

- Process under an inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen purging) if possible, to limit oxygen exposure [11].

- Incorporate antioxidants into the recyclate. These additives scavenge free radicals, inhibiting the oxidation pathway that leads to cross-linking [14] [12].

- Optimize residence time in the processing equipment to avoid excessive heat history [2] [13].

Problem: Inconsistent Batch-to-Batch Quality of Post-Conser Recyclate (PCR)

- Observed Issue: The properties of the recycled feedstock are highly variable, making it difficult to guarantee product performance [11].

- Molecular Cause: Uncontrolled and variable degradation pathways due to unknown history, contamination, and mixed polymer grades [11]. Different contaminants and initial molecular structures degrade at different rates and via different mechanisms [11].

- Solutions:

- Implement a rapid quality control method using rheology to "fingerprint" the recyclate's degradation propensity before large-scale processing [11].

- Improve feedstock sorting and washing to reduce contamination from other polymers, labels, and organic residues [12].

- Use stabilizer packages designed for recycled materials to create a more consistent and robust processing window [14] [12].

Quantitative Data on Polymer Degradation

Table 1: Quantifiable Molecular Changes in PLA During Multiple Extrusion Cycles [10]

| Reprocessing Cycle | Number Average Molar Mass (Mₙ) Reduction | Crystallinity (%) | Melt Flow Index (MFI) Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virgin (PLA0) | Baseline | 6.9% | Baseline |

| 1st Cycle (rPLA1) | ~10% reduction | ~15% (est.) | Increased |

| 3rd Cycle (rPLA3) | ~25% reduction | ~25% (est.) | Significantly Increased |

| 6th Cycle (rPLA6) | ~40% reduction | 39.5% | Greatly Increased |

Table 2: Rheological Indicators of Polyethylene Degradation Under Different Environments [11]

| Processing Environment | Dominant Mechanism | Change in Complex Viscosity (η*) | Change in vGP Plot | Molecular Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen (N₂) | Chain Scission | Increase of ~14% (at 10 rad/s) | Flattened curve | Slight branching possible |

| Air (Oxygen Present) | Long-Chain Branching | Increase 5x greater than in N₂ (at 0.1 rad/s) | Increased curvature, lower phase angle | Significant branching and cross-linking |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Simulating Mechanical Recycling via Rheology

This protocol uses a rheometer to simulate the shear and thermal history of multiple extrusion cycles, providing a rapid assessment of a polymer's degradation propensity [11].

- Sample Preparation: Cut or compression-mold the polymer (virgin or recyclate) into disks that fit the rheometer plate geometry.

- Instrument Setup: Equip the rheometer with parallel plates and an environmental test chamber capable of gas purging.

- Loading and Melting: Load the sample onto the pre-heated plate (set to the typical processing temperature, e.g., 180°C for PLA, 190°C for HDPE). Trim excess material and close the gap.

- Environment Control: Purge the measurement chamber with the desired gas (Nitrogen for inert conditions, Air for oxidative conditions) for at least 5 minutes before and during the test.

- Oscillatory Time-Treatment: Apply a constant oscillatory shear stress or strain at a fixed frequency (e.g., 1-10 rad/s) for a prolonged period (e.g., 1-3 hours) to simulate mechanical recycling.

- Intermittent Frequency Sweeps: At regular intervals (e.g., every 20 minutes), run a full frequency sweep (e.g., 0.1 to 100 rad/s) to monitor the evolution of the viscoelastic properties (G', G", η*).

- Data Analysis: Plot the complex viscosity and Van Gurp-Palmen plots (Phase Angle δ vs. |G|) for each interval. A decreasing η and flattened vGP plot indicate chain scission. An increasing η* and more curved vGP plot indicate long-chain branching [11].

Protocol: Quantifying Chain Scission via Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC)

This protocol measures the direct reduction in molecular weight, the hallmark of chain scission [10].

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve the polymer samples (virgin and recycled) in an appropriate solvent (e.g., THF for many polymers) at a low concentration (~1-2 mg/mL). Filter the solutions through a 0.45 μm filter to remove any gel particles or impurities.

- GPC System Calibration: Calibrate the GPC system using narrow dispersity polymer standards of known molecular weight that match the polymer being analyzed.

- Sample Injection: Inject a precise volume of the filtered polymer solution into the GPC system.

- Chromatogram Acquisition: The system separates polymer chains by their hydrodynamic volume as they pass through the columns. A detector (e.g., refractive index) records the elution time and concentration.

- Data Analysis: Software converts the elution time data into molecular weight distributions. Compare the number-average molar mass (Mₙ), weight-average molar mass (M𝄬), and dispersity (Ð) of the recycled samples to the virgin material. A consistent decrease in Mₙ and M𝄬 is quantitative evidence of chain scission [10].

Degradation Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Polymer Degradation Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Antioxidants (e.g., Hindered Phenols, Phosphites) | Scavenge free radicals to inhibit thermo-oxidative degradation during processing [14] [12]. | Added to recyclate to stabilize it and prevent cross-linking and discoloration during multiple extrusion cycles [14]. |

| Chain Extenders (e.g., Epoxy-functionalized, Carbodiimides) | Reconnect cleaved polymer chains through reactive group coupling, counteracting chain scission [12]. | Used to restore the molecular weight and melt viscosity of recycled condensation polymers like PLA or PET [12]. |

| Stabilizer Packages (e.g., UV absorbers, Hindered Amine Light Stabilizers) | Protect the polymer from various environmental degradation factors beyond processing [14]. | Incorporated into recycled products intended for outdoor use to enhance their long-term durability [14]. |

| Purge Compounds | Specialized formulations to clean processing equipment (extruders, injection molders) of degraded polymer residues [13]. | Used during material changeover or machine shutdown/startup to prevent contamination of new batches with black specks from carbonized degraded polymer [13]. |

| Inert Gas (e.g., Nitrogen N₂) | Creates an oxygen-free processing environment to minimize thermo-oxidative degradation [11]. | Used to purge the barrel of an extruder or the chamber of a rheometer during reprocessing experiments to study/control degradation mechanisms [11]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary degradation mechanisms that occur during the mechanical recycling of polymers?

During mechanical recycling, polymers are predominantly subjected to thermal, thermo-mechanical, and thermal-oxidative degradation due to the high temperatures and shear forces experienced during processes like extrusion and injection molding [9]. These processes can cause chain scission (breaking of the polymer backbone), cross-linking, or the formation of new functional groups, all of which alter the polymer's fundamental structure [9]. For polyesters, hydrolytic degradation is also a significant concern if moisture is present during processing [9].

FAQ 2: How does a change in Molecular Weight (Mw) and Polydispersity Index (PDI) affect the performance of a recycled polymer product?

A decrease in Mw, typically resulting from chain scission, directly leads to a reduction in key mechanical properties such as tensile strength, toughness, and impact resistance [15] [16]. An increase in PDI indicates a broader molecular weight distribution, often signifying inconsistent degradation and potentially leading to unpredictable processing behavior and final product performance, such as variations in melt viscosity and brittleness [15]. In applications like amorphous solid dispersions for pharmaceuticals, minute changes in Mw and PDI can significantly impact the dissolution performance of a drug [15].

FAQ 3: Why do some polymers become brittle after repeated recycling cycles?

Brittleness is primarily a consequence of chain scission reducing the average molecular weight, which shortens the polymer chains and limits their ability to entangle and absorb energy [16] [14]. Additionally, certain degradation mechanisms, like photo-oxidation, can lead to embrittlement, surface cracking, and discoloration [14] [17]. For some polymers, cross-linking during degradation can also increase brittleness by reducing the chain mobility between cross-links [17].

FAQ 4: What analytical techniques are essential for characterizing polymer degradation in a research setting?

Key techniques include:

- Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC): Essential for tracking changes in Molecular Weight and PDI [15].

- Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy: Identifies the formation of new functional groups (e.g., carbonyl groups from oxidation) [16].

- Thermal Analysis (DSC/TGA): Monitors changes in thermal properties like glass transition temperature (Tg) and thermal stability [15].

- Mechanical Testing: Measures the loss of properties like tensile strength and elongation at break [16].

- Rheological Evaluations: Assesses changes in melt viscosity, which is directly influenced by Mw [15].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue: Inconsistent Mechanical Properties in Reprocessed Polymer Samples

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High variability in tensile strength and elongation at break between batches. | Inconsistent degradation due to fluctuating processing parameters (temperature, shear rate) or moisture content. | Standardize and tightly control processing conditions (temperature, screw speed). Ensure polymers are thoroughly dried before processing according to manufacturer guidelines [1]. |

| A significant drop in impact resistance after recycling. | Severe chain scission leading to a critical reduction in molecular weight. | Optimize processing temperature to the minimum required to reduce thermal degradation. Consider incorporating stabilizers or blending with virgin material to restore properties [9]. |

| Polymer melt becomes too fluid and difficult to control during extrusion. | Advanced chain scission has significantly lowered the average molecular weight. | Gradually decrease processing temperatures in small increments (e.g., 5°C) and minimize residence time in the extruder [1]. |

Issue: Unwanted Color Formation (Yellowing/Browning) During Processing

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer exhibits yellow or brown discoloration after extrusion. | Thermal-oxidative degradation leading to the formation of chromophores [9]. | Ensure the processing temperature is below the polymer's degradation onset temperature. Use an inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen purging) during processing to minimize oxidative degradation [9]. |

| Burnt particles are present in the extrudate, contaminating the product. | Localized overheating or contamination from previously degraded polymer residue in the equipment. | Immediately purge the extruder. Perform a thorough cleaning of the barrel and screw before starting new experiments [1]. |

Experimental Protocols for Degradation Research

Protocol 1: Investigating Thermo-Oxidative Degradation during Simulated Recycling

Objective: To quantify the impact of multiple extrusion cycles on the molecular weight, dispersity, and mechanical integrity of a target polymer.

Materials:

- Polymer pellets (e.g., PLA, PP)

- Twin-screw extruder

- Granulator

- Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) system

- Tensile testing machine

- Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC)

Methodology:

- Preparation: Dry the polymer pellets thoroughly to eliminate hydrolytic degradation as a variable.

- Initial Characterization: Analyze the virgin material using GPC (for Mw and PDI), DSC (for Tg and Tm), and tensile testing (for baseline mechanical properties).

- Processing Cycle: a. Process the polymer through the extruder at a predetermined temperature profile and screw speed. b. Quench the extrudate in a water bath and pelletize it using a granulator.

- Repeated Processing: Subject the pelleted material to repeated cycles of extrusion and granulation (e.g., up to 5 cycles).

- Post-Processing Analysis: After each processing cycle, collect a sample and perform the same characterization as in Step 2.

Expected Outcomes: With an increasing number of processing cycles, you will typically observe a progressive decrease in molecular weight, an increase in PDI, a reduction in tensile strength and elongation at break, and potential changes in thermal transition temperatures.

Protocol 2: Accelerated Aging to Study UV Degradation

Objective: To evaluate the surface and bulk property changes of polymers upon exposure to UV radiation.

Materials:

- Polymer films or injection-molded plaques

- UV aging chamber (e.g., with a Xenon arc lamp per ISO 4892-2)

- FTIR Spectrometer

- Impact tester

- Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

Methodology:

- Baseline Testing: Characterize the initial surface chemistry (FTIR), mechanical properties (impact strength), and surface morphology (SEM).

- UV Exposure: Place samples in the UV aging chamber. Exposure conditions should be set according to relevant standards (e.g., specific wavelength, irradiance, chamber temperature, and relative humidity) to simulate real-world conditions [17].

- Periodic Sampling: Remove samples at regular intervals (e.g., 250, 500, 1000 hours).

- Post-Exposure Analysis: Repeat the baseline tests on the exposed samples. FTIR is particularly useful for detecting the formation of carbonyl groups from photo-oxidation.

Expected Outcomes: UV exposure typically leads to surface cracking, chalking, and embrittlement. FTIR will show an increase in carbonyl index, impact strength will drop significantly, and SEM images will reveal micro-cracks and surface pitting [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Degradation Research |

|---|---|

| Antioxidants | Inhibit oxidative degradation by scavenging free radicals that are generated during thermal processing, thereby helping to maintain molecular weight and mechanical properties [9]. |

| UV Stabilizers | Absorb or screen out harmful UV radiation to protect polymers from photo-oxidative degradation, delaying surface embrittlement and color changes [14]. |

| HALS (Hindered Amine Light Stabilizers) | A highly effective class of UV stabilizers that inhibit the degradation cycle by neutralizing free radicals formed during photo-oxidation [18]. |

| Chain Extenders | Used in recycling to repair polymer chains that have undergone scission. They can increase the molecular weight and improve melt viscosity, thus restoring some mechanical performance [9]. |

The following table summarizes quantitative data on how degradation impacts key polymer properties, as reported in research.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Degradation on Polymer Properties

| Polymer Type | Degradation Condition | Change in Mw | Change in PDI | Impact on Mechanical Properties | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVP-VA64 (Pharmaceutical Polymer) | Hot-Melt Extrusion (HME) | Decrease | Increase (broader mass distribution) | Impacts dissolution performance & API supersaturation | [15] |

| Fibre/Epoxy Composite | UV Ageing (80 days) | Not Specified | Not Specified | Longitudinal Compressive Strength: Reduced to 51% of original. Flexural Strength: Reduced to 77% of original. | [17] |

| General Polymers | Thermal & Thermo-mechanical Processing | Decrease (via chain scission) | Increase | Reduction in tensile strength, toughness, and elongation at break. | [16] [9] |

Visualization of Degradation Pathways and Workflows

Degradation Pathways in Polymer Recycling

Experimental Workflow for Recycling Study

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guide

FAQ 1: Why is the degradation rate of my polyester-based medical device (e.g., PLA screw) not matching literature values in my in vitro tests?

- Answer: The degradation rate of biodegradable polyesters is highly sensitive to experimental conditions. A common discrepancy arises from differences in the hydrolytic degradation environment.

- Check Your Buffering Solution: Polyesters like PLA and PLGA degrade primarily through hydrolysis of ester bonds, releasing acidic byproducts (e.g., lactic acid). If the buffer capacity of your in vitro medium is insufficient, the local pH will drop, autocatalyzing the degradation process and leading to faster-than-expected rates [19]. Ensure you use a well-buffered solution (e.g., PBS) with a capacity that mimics the buffering action of physiological fluids.

- Monitor Molecular Weight and Mass Loss: Degradation is a multi-stage process. The onset of significant mass loss often occurs only after the polymer's molecular weight has decreased substantially [19]. Simultaneously track both molecular weight (via GPC) and mass loss to get a complete picture of the degradation profile.

- Consider Device Morphology and Crystallinity: The initial molecular weight, crystallinity, and physical form of the polymer significantly impact water diffusion and degradation. Enzymatic degradation also targets amorphous regions more readily than crystalline ones. Characterize these initial material properties to make a valid comparison with literature data [20] [21].

FAQ 2: We are researching the biodegradation of polyolefins (e.g., PE, PP) for sustainable applications. Why do we observe minimal degradation even with microbial consortia in our bioreactors?

- Answer: Polyolefins are inherently recalcitrant to biodegradation due to their hydrophobic nature, high molecular weight, and stable C-C and C-H bonds, which are inaccessible to microbial enzymes without pre-treatment [22] [23].

- Implement a Pre-oxidation Step: The biodegradation of polyolefins typically requires an initial abiotic oxidation step (oxo-biodegradation). Consider pre-treating your polymer samples with UV light or heat to introduce carbonyl groups (ketones, carboxylic acids) into the polymer backbone. This breaks the chains and creates sites for microbial enzyme attachment [22] [23]. You can monitor the success of pre-treatment by measuring the Carbonyl Index using FTIR spectroscopy.

- Verify Biofilm Formation: Microbial degradation often begins with the formation of a biofilm on the polymer surface. Use techniques like scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to confirm that your microbial consortia are successfully adhering to and colonizing the polymer surface, a stage known as biodeterioration [22].

- Characterize the Final Products: To confirm biodegradation is occurring, analyze the output for products of bioassimilation and mineralization, such as carbon dioxide (under aerobic conditions) or methane (under anaerobic conditions), in addition to monitoring physical changes in the polymer [21].

FAQ 3: How can we accurately control and predict the service life of a biodegradable polyester scaffold for tissue engineering?

- Answer: Controlling the service life involves tailoring the polymer's properties and understanding the degradation kinetics.

- Leverage Copolymer Ratios: The degradation rate of copolymers like PLGA can be finely tuned by adjusting the ratio of its monomers. For example, increasing the proportion of glycolide (GA) relative to lactide (LA) in PLGA accelerates degradation. A PLGA 50:50 degrades significantly faster than a PLGA 75:25 [19].

- Control Crystallinity: Processing conditions (e.g., annealing, cooling rate) can be adjusted to modify the polymer's crystallinity. Since amorphous regions degrade faster, a more crystalline polymer will generally have a longer service life [19] [21].

- Use Accelerated Ageing Tests Judiciously: Standardized accelerated ageing tests (e.g., under elevated temperature or UV light) can provide comparative data. However, when predicting absolute service life, ensure the accelerated conditions do not alter the fundamental degradation mechanism. Always validate these predictions with real-time studies under relevant conditions [23].

FAQ 4: Our experiments on styrene-based materials (e.g., PS) show conflicting biodegradation results. What are the key factors to consider in experimental design?

- Answer: The biodegradation of polystyrene (PS) is challenging and highly dependent on specific microbial strains and environmental conditions.

- Source Specialized Microorganisms: Only certain microorganisms possess the enzymatic machinery to initiate PS breakdown. Consider sourcing strains reported in the literature, such as Rhodococcus ruber or organisms isolated from the gut of plastic-eating waxworms [22]. The presence of a benzene ring in PS makes it particularly recalcitrant [22].

- Employ Appropriate Analytical Techniques: Weight loss alone is an insufficient metric for slow-degrading polymers like PS. Combine it with more sensitive techniques to detect early-stage degradation:

- Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC): To detect reductions in molecular weight.

- Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy: To identify the formation of new oxidative functional groups (e.g., carbonyl groups) on the polymer surface [23].

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): To visualize surface erosion and cracking.

- Acknowledge the Role of Pre-treatment: Like polyolefins, PS degradation is often enhanced by UV or thermal pre-treatment, which breaks the polymer chains and facilitates microbial attack [22]. Clearly document any pre-treatment steps in your methodology.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Hydrolytic Degradation of PolyestersIn Vitro

This protocol outlines a standard method for evaluating the degradation profile of biodegradable polyesters like PLA, PCL, and PLGA under simulated physiological conditions [19].

1. Materials and Reagents

- Polymer Samples: Compression-molded or solution-cast films of the polyester.

- Buffer Solution: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4, with sodium azide (0.02% w/v) to prevent microbial growth.

- Equipment: Incubator or water bath maintained at 37°C, sterile containers (e.g., centrifuge tubes), analytical balance, freeze dryer.

2. Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Cut polymer films into precise dimensions (e.g., 10 mm x 10 mm). Weigh each sample accurately (initial dry weight, W₀) and record initial thickness.

- Immersion: Place each sample in a separate container with a sufficient volume of PBS (e.g., 20 mL per 100 mg of polymer) to ensure sink conditions.

- Incubation: Place the containers in an incubator at 37°C.

- Sampling and Analysis: At predetermined time intervals (e.g., 1, 4, 12, 24 weeks), remove samples in triplicate for analysis.

- Mass Loss: Rinse retrieved samples with deionized water, lyophilize to constant weight, and weigh (final dry weight, *Wᵢ)). Calculate percentage mass loss:

(W₀ - Wᵢ) / W₀ × 100%. - Molecular Weight Change: Analyze the dried samples using Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) to track the reduction in molecular weight over time.

- pH Monitoring: Measure the pH of the buffer solution at each time point to track acidification.

- Morphology: Examine the surface and cross-section of degraded samples using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM).

- Mass Loss: Rinse retrieved samples with deionized water, lyophilize to constant weight, and weigh (final dry weight, *Wᵢ)). Calculate percentage mass loss:

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Simulates the ionic strength and pH of physiological fluids for hydrolytic degradation. |

| Sodium Azide | Prevents microbial growth in the buffer, ensuring degradation is due to hydrolysis and not biodegradation. |

| Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) | Analyzes changes in the polymer's molecular weight and distribution, an early indicator of degradation. |

Protocol 2: Evaluating Microbial Degradation of Polyolefins

This protocol describes a method to screen and assess the ability of microorganisms to degrade pre-treated polyolefin films [22].

1. Materials and Reagents

- Polymer Samples: Low-density polyethylene (LDPE) or Polypropylene (PP) films.

- Microbial Inoculum: A pure strain (e.g., Rhodococcus ruber) or a microbial consortium from activated sludge or soil.

- Mineral Salt Medium (MSM): A carbon-free medium containing essential salts to force microbes to utilize the polymer as the sole carbon source.

- Equipment: UV cross-linker or oven for thermal pre-treatment, shaker incubator, sterile glassware, FTIR spectrometer.

2. Procedure

- Polymer Pre-treatment: Expose polymer films to UV radiation (e.g., 254 nm) for a set duration (e.g., 100 hours) or heat to introduce carbonyl groups. Characterize the pre-treated films using FTIR to calculate the initial Carbonyl Index.

- Inoculum Preparation: Grow the microbial strain in a nutrient-rich medium, then harvest and wash the cells to remove residual carbon.

- Inoculation and Incubation: Aseptically place pre-treated polymer films in Erlenmeyer flasks containing MSM. Inoculate with the microbial suspension. Maintain control flasks with polymer but no inoculum, and with inoculum but no polymer.

- Incubation: Incubate the flasks in a shaker incubator (e.g., 30°C, 120 rpm) for several weeks.

- Analysis:

- Biofilm Formation: Periodically check for biofilm formation on the polymer surface using SEM.

- Weight Loss: After incubation, carefully remove the films, clean them to remove adhered biomass, dry, and measure weight loss.

- Surface Analysis: Perform FTIR analysis on the retrieved films to track changes in the Carbonyl Index and other functional groups.

- Metabolic Activity: Monitor microbial growth (e.g., optical density) or CO₂ production in the headspace to confirm bioassimilation.

Table 1: Mechanical and Degradation Properties of Common Biodegradable Polyesters

Data compiled for biomedical applications [19].

| Polymer | Tensile Modulus (MPa) | Ultimate Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elongation at Break (%) | Typical Degradation Time (Months) | Key Degradation Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGA | 7,000 - 8,400 | ~890 | ~30 | 6 - 12 | Hydrolysis (Fast) |

| PLA | ~3,500 | ~55 | 30 - 240 | > 24 | Hydrolysis (Slow) |

| PCL | ~700 | 4 - 28 | 700 - 1000 | > 24 | Hydrolysis & Enzymatic |

| PLGA (50:50) | ~2,000 | ~64 | 3 - 10 | 1 - 3 | Hydrolysis (Rate tunable by LA:GA ratio) |

| PHB | ~3,500 | ~40 | 5 - 8 | > 24 | Hydrolysis |

Table 2: Characteristics of Common Non-(Readily)Biodegradable Polymers

Data relevant to recycling and environmental degradation research [22] [23] [24].

| Polymer | Key Structural Feature | Primary Degradation Challenge | Potential Degradation Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene (PE) | C-C backbone, hydrophobic | High molecular weight, stable C-C bonds | Oxo-biodegradation (UV/heat pre-treatment + microbial) |

| Polypropylene (PP) | C-C backbone with methyl groups | Steric hindrance from branches | Oxo-biodegradation; more difficult than PE |

| Polystyrene (PS) | C-C backbone with benzene rings | Aromatic ring stability | Specific microbial consortia (e.g., R. ruber); often requires pre-treatment |

| Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) | Ester bonds + aromatic rings | Crystallinity and aromatic content | Chemical recycling (e.g., glycolysis, hydrolysis); enzymatic degradation |

Degradation Pathway Visualizations

Polyester Hydrolytic Degradation Pathway

Title: Polyester Hydrolytic Degradation Mechanism

Oxo-Biodegradation of Polyolefins

Title: Two-Stage Oxo-Biodegradation of Polyolefins

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

This section addresses common challenges you might encounter in your research on polymer degradation and its health effects, providing targeted solutions based on current experimental models.

FAQ 1: How can I accurately quantify micro- and nanoplastic (MNP) accumulation in bone tissue for toxicological assessment?

- Challenge: Researchers often struggle with detecting and quantifying MNPs in complex, calcified tissues like bone, where background interference is high and particle distribution is heterogeneous.

- Solution: Implement a multi-step digestion and extraction protocol followed by advanced spectroscopic confirmation.

- Tissue Preparation: Dissect and clean bone tissue thoroughly to remove adherent soft tissue. Pulverize the sample under liquid nitrogen to a fine powder using a sterile mortar and pestle.

- Organic Matrix Digestion: Digest 1g of pulverized bone tissue using 10 mL of 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution. Incubate at 60°C for 48 hours with continuous agitation to fully dissolve the organic component without degrading common polymers like PS, PE, and PP [25].

- Density Separation: Centrifuge the digestate and resuspend the pellet in a saturated sodium iodide (NaI) solution (density ~1.8 g/cm³). Centrifuge again; MNPs will float to the surface and can be collected by vacuum filtration onto a polycarbonate membrane filter [4].

- Identification and Quantification: Analyze the filtered particles using µ-Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (µ-FTIR) or Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (Pyr-GC/MS). For bone studies, Pyr-GC/MS is often preferred for its ability to quantify specific polymer masses (e.g., μg of PS per gram of tissue) [25] [4].

FAQ 2: My in vivo model is not showing consistent inflammatory responses to polymer degradation products. What factors should I optimize?

- Challenge: Inconsistent inflammatory outcomes can stem from variable MNP bioavailability, differences in animal model physiology, or inconsistent characterization of the administered dose.

- Solution: Standardize the MNP exposure material and focus on precise delivery routes.

- Particle Characterization: Before exposure, fully characterize the MNPs using Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) for hydrodynamic diameter and Zeta potential for surface charge. This ensures batch-to-batch consistency [25].

- Exposure Route: For systemic and bone-targeted effects, consider intravenous (IV) injection to bypass gastrointestinal variability. For oral exposure, use gavage with a well-dispersed MNP suspension in a vehicle like 0.05% carboxymethyl cellulose, rather than mixing it into feed, to ensure accurate and consistent dosing [25].

- Endpoint Analysis: Move beyond general cytokine profiling. Focus on specific osteotoxicity markers by analyzing gene and protein expression of key osteoclastogenic factors like RANKL in bone marrow or bone tissue using RT-qPCR and ELISA [25].

FAQ 3: What is the best method to distinguish the toxicity of the polymer particle itself from the toxicity of leached additives?

- Challenge: The inherent toxicity of polymer particulates is often conflated with the effects of chemical additives (e.g., plasticizers, stabilizers) that can leach out, leading to misinterpretation of mechanisms.

- Solution: Employ a rigorous experimental design with appropriate controls.

- Prepare Leachate: Incurate the MNPs (e.g., 1 mg/mL) in the experimental medium (e.g., cell culture medium or saline) under standard culture conditions (37°C, with agitation) for 48 hours. Centrifuge at high speed (e.g., 100,000 × g for 2 hours) to pellet all particles. Carefully collect the supernatant, which is the particle-free leachate [4].

- Design Experimental Groups:

- Group A: Unexposed controls (medium only).

- Group B: Exposed to the full MNP suspension (particles + potential leachates).

- Group C: Exposed only to the particle-free leachate.

- Comparative Analysis: Assess toxicological endpoints (e.g., cell viability, oxidative stress, gene expression) across all groups. A significant effect in Group B but not in Group C points to particle-dominated toxicity. A significant effect in Group C indicates leachate-dominated toxicity [25] [4].

Quantitative Data on MNP Exposure and Effects

The following tables consolidate key quantitative data from recent studies to aid in experimental design and data interpretation.

Table 1: Documented Concentrations of Microplastics in Human Tissues and Fluids

| Matrix/Tissue | Detected Polymers | Average Concentration | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peripheral Blood | PET, PS, PE | 1.6 μg/mL | [25] |

| Bone Marrow | PE, PS, PVC, PA66, PP | 51.29 μg/g | [25] |

| Weekly Human Ingestion (Estimated) | Various | 0.1 - 5.0 g (equiv. to 74,000–121,000 particles) | [25] [26] |

Table 2: Key Signaling Pathways Implicated in MNP-Induced Osteotoxicity

| Pathway | Cell Type(s) | Primary Experimental Model | Key Outcome(s) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RANKL / NF-κB | Osteoclasts, Macrophages | Rodent Bone Marrow | Promotion of osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption activity. | [25] |

| MAPK | Osteoblasts, Osteoclasts | In Vitro Cell Cultures | Alteration of cell differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis. | [25] |

| BMP/Smad | Osteoblasts, MSCs | In Vitro Cell Cultures | Disruption of bone formation and homeostasis. | [25] |

| Oxidative Stress (Nrf2/ARE) | Various Bone Cells | In Vivo (Rodent) & In Vitro | Induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to inflammation and cell damage. | [25] [4] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Osteoclastogenesis in Primary Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophages (BMMs) Exposed to MNPs

This protocol is critical for evaluating the impact of MNPs on bone resorption.

- BMM Isolation: Euthanize an 8-10 week old C57BL/6 mouse following ethical guidelines. Dissect out femurs and tibiae, and flush the bone marrow cavity with alpha-MEM medium using a sterile 25-gauge needle.

- Cell Culture: Suspend the collected cells in complete alpha-MEM medium (supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin, and 30 ng/mL of Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor (M-CSF)). Culture in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for 3 days to allow for adherence and proliferation of BMMs.

- MNP Exposure and Differentiation: Seed BMMs in a 96-well plate at a density of 8 x 10³ cells/well. Replace the medium with osteoclastogenic medium (complete alpha-MEM with 30 ng/mL M-CSF and 50 ng/mL RANKL). Add the test MNPs (e.g., 50 nm PS-NPs at 10-100 μg/mL) to the treatment wells. Include a positive control (RANKL only) and a negative control (no RANKL). Refresh the medium and treatments every two days.

- Endpoint Analysis (Day 7):

- Tartrate-Resistant Acid Phosphatase (TRAP) Staining: Fix cells and stain using a commercial TRAP staining kit. Multinucleated (≥3 nuclei) TRAP-positive cells are counted as mature osteoclasts.

- Pit Assay: Seed BMMs on synthetic hydroxyapatite-coated plates. After the differentiation period, visualize resorption pits by light microscopy after washing away the cells. The percentage of resorbed area can be quantified with image analysis software [25].

Protocol 2: Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) for Evaluating Chemical Recycling of Mixed Plastic Waste

This methodology is essential for framing polymer degradation research within the context of sustainable recycling.

- Goal and Scope Definition: Define the objective (e.g., to compare the climate change impact of chemical recycling vs. incineration with energy recovery). Set the functional unit to "management of 1 tonne of mixed plastic waste (MPW)". The system boundaries should include all processes from waste collection to the production of the final recycled product (naphtha) [27].

- Life Cycle Inventory (LCI): Compile energy and material input/output data. For a decentralized pyrolysis plant (e.g., 165 kg/hr capacity), this includes:

- Inputs: Electricity, natural gas for process heat, MPW feedstock.

- Outputs: Primary product (naphtha), by-products (e.g., char, gases), and emissions (CO₂, CH₄, NOₓ) [27].

- Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA): Use LCA software (e.g., SimaPro, OpenLCA) and databases (e.g., ecoinvent) to translate inventory data into environmental impacts. The key category is Global Warming Potential (kg CO₂-equivalent) [27].

- Interpretation: Compare the results against conventional scenarios. For example, the study found a reduction of 1284 kg CO₂-eq. per tonne of MPW when using chemical recycling instead of waste-to-energy incineration [27].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram: MNP-Induced Disruption of Bone Homeostasis

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for In Vivo MNP Osteotoxicity

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Polymer Degradation and Toxicity Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene Nanospheres | Model MNPs for in vitro and in vivo exposure studies. | Available in various sizes (e.g., 50 nm, 100 nm) and surface functionalizations (plain, carboxylated, aminated). Useful for studying particle-size-dependent effects [25]. |

| Recombinant M-CSF | Promotes the survival and proliferation of BMM precursors. | Essential for the in vitro differentiation of osteoclasts from bone marrow cells [25]. |

| Recombinant RANKL | The key cytokine that induces osteoclast differentiation. | Used in combination with M-CSF to generate osteoclasts in culture for bone resorption studies [25]. |

| TRAP Staining Kit | Histochemical identification of mature osteoclasts. | Allows for the quantification of osteoclast number and activity in cell culture or bone tissue sections [25]. |

| KOH Solution | Digests organic biological material for MNP extraction. | Effective for isolating MNPs from complex tissues like bone without significantly degrading common polymers [25] [4]. |

| Synthetic Hydroxyapatite-Coated Plates | Substrate for measuring osteoclast resorptive function. | Used in the pit assay to quantitatively assess the bone degradation capacity of mature osteoclasts in vitro [25]. |

| Pyrolysis-GC/MS System | Quantitative analysis of polymer mass in biological and environmental samples. | The gold-standard method for unequivocally identifying and quantifying specific polymer types (e.g., PS, PE) in complex matrices [25] [4]. |

Analytical Techniques and Processing Technologies for Degradation Assessment

FAQs: Core Techniques in Polymer Degradation Research

Q1: How can rheology detect polymer degradation during mechanical recycling?

Rheological measurements are highly sensitive to changes in molecular structure caused by degradation. A decrease in the zero-shear viscosity (η₀) often indicates a reduction in average molecular weight due to chain scission, a common thermal or thermo-mechanical degradation effect during extrusion or injection molding [28]. Conversely, an increase in the steady-state recoverable compliance (Jₑ⁰) can signal the formation of a branched structure or the presence of a low molecular weight fraction, which alters the elasticity of the polymer melt [28]. These measurements provide a rapid, bulk assessment of molecular changes without the need for dissolution, making them ideal for quality control in recycling processes [3] [28].

Q2: Why is infrared (IR) spectroscopy particularly valuable for analyzing recycled polymers?

IR spectroscopy excels not only in identifying polymer types but also in diagnosing the chemical consequences of degradation. It can directly detect the formation of oxygen-containing functional groups like carbonyls (C=O) and hydroperoxides (ROOH) that result from thermal-oxidative degradation [16] [29]. Furthermore, it can probe the material's physical structure, providing insights into changes in crystallinity and molecular orientation induced by processing history [29]. This makes it a powerful tool for comparing recycled material to virgin polymer references and for assessing batch-to-batch homogeneity [29].

Q3: What chromatographic method is best for quantifying changes in molecular weight after reprocessing?

Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), also known as Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC), is the primary chromatographic technique for this purpose [16] [30]. It separates polymer molecules by their hydrodynamic volume, providing detailed data on the molecular weight distribution (MWD). A shift in the MWD or a decrease in the average molecular weight (e.g., Mₙ, M𝓌) directly confirms chain scission from degradation. An increase in the polydispersity index (Đ) can indicate simultaneous scission and cross-linking events [3]. SEC/GPC is a routine method for understanding the scission and cross-linking processes that occur during polymer degradation [16].

Q4: How do I choose between NIR and MIR spectroscopy for plastics sorting and analysis?

The choice depends on the application and sample characteristics. Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy is fast, requires little to no sample preparation, and is well-suited for rapid identification and sorting of clean plastics based on their distinct spectral features [31]. However, it is less effective for black plastics containing carbon black, which absorbs NIR radiation [31]. Mid-Infrared (MIR) spectroscopy probes fundamental molecular vibrations, providing richer chemical information and is more effective for analyzing filled or dark-colored polymers, as it can be used with techniques like ATR that are less affected by strong absorbers [29] [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Rheometry: Interpreting Complex Viscosity Data

A researcher is analyzing a recycled polypropylene melt and observes an unexpected rheological response.

- Problem: The complex viscosity curve shows a significant drop at low frequencies compared to the virgin material.

- Investigation & Solution:

| Observation | Possible Cause | Underlying Degradation Mechanism | Confirmatory Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drop in low-frequency viscosity and modulus. | Reduction in average molecular weight. | Chain scission due to thermo-mechanical stress during reprocessing [3]. | Perform SEC/GPC to measure the molecular weight distribution and confirm the shift [3]. |

| Increase in elasticity (Jₑ⁰) and a broader relaxation time spectrum. | Formation of long-chain branching or a high molecular weight tail. | Cross-linking or branching via radical recombination during thermal-oxidative degradation [3] [28]. | Conduct elongational rheometry to check for strain hardening, a signature of long-chain branching [28]. |

Chromatography: SEC/GPC Analysis of Degraded Polymers

A scientist runs an SEC test on a mechanically recycled polyester and encounters issues with the chromatogram.

- Problem: The SEC chromatogram shows peak broadening and a shifting baseline.

- Investigation & Solution:

| Symptom | Potential Issue | Root Cause in Recycling Context | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broad, tailing peaks. | Column overloading or undesirable interactions between the analyte and the stationary phase. | Presence of low molecular weight fragments (degradation products) or additives from the waste stream [3]. | Reduce the injection volume or concentration. Use a guard column. Ensure the eluent is a good solvent for all potential degradation products [32]. |

| Shifting or drifting baseline. | Contamination of the system or detector cell by previous samples. | Carry-over of polymer additives (e.g., stabilizers, plasticizers) or degraded oligomers [32]. | Flush the system thoroughly with a strong solvent. Use a dedicated column for recycled materials analysis. Filter samples to remove insoluble gel particles [32]. |

Spectroscopy: FTIR for Oxidation Tracking

An analyst uses FTIR to monitor oxidation in polyethylene after multiple extrusion cycles but gets noisy, inconsistent data.

- Problem: The carbonyl index calculation is inconsistent between replicate samples.

- Investigation & Solution:

| Symptom | Likely Reason | Impact on Degradation Assessment | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| High noise in the carbonyl region (~1715 cm⁻¹). | Poor contact between the sample and ATR crystal, or an insufficient number of scans. | Inaccurate quantification of the oxidation level, leading to unreliable conclusions about material stability [29]. | Ensure the sample is pressed firmly and uniformly against the crystal. Increase the number of scans to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. |

| Inconsistent absorbance values. | Sample inhomogeneity and surface irregularities. | Recycled polymer batches are often inhomogeneous; a non-representative measurement leads to high data variance [29]. | Prepare a homogeneous film via compression molding [29]. Take spectra from multiple spots on the sample and average the results. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Monitoring Thermal-Oxidative Degradation via FTIR

Aim: To quantify the level of oxidation in a polyolefin (e.g., PE or PP) sample subjected to multiple extrusion cycles.

Materials:

- FTIR spectrometer with ATR accessory

- Compression molding press

- Virgin and recycled polymer pellets

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Compression mold pellets into uniform thin films (~100 µm thickness) using a predefined cycle (e.g., 200°C for 2 minutes) [29].

- Data Acquisition:

- Place the film on the ATR crystal.

- Collect a background spectrum.

- Collect sample spectra in the range of 4000–400 cm⁻¹ with a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹ and 32 scans per spectrum.

- Repeat the measurement on at least three different spots of the film.

- Data Analysis:

- Use a baseline correction method (e.g., subtracting the absorbance at a non-absorbing wavelength like ~1900 cm⁻¹) [31].

- Calculate the Carbonyl Index using the following formula, which uses an internal reference peak to normalize the data:

- Carbonyl Index = (Area under carbonyl peak ~1715 cm⁻¹) / (Area under reference peak ~1460 cm⁻¹ or ~2849 cm⁻¹) [16] [29].

Protocol 2: Assessing Molecular Weight Change via SEC/GPC

Aim: To determine the change in molecular weight and distribution of a polymer after a reprocessing step.

Materials:

- SEC/GPC system with refractive index (RI) detector

- Appropriate columns (e.g., 3x mixed-bed columns)

- Solvent (e.g., THF for PS, PLA; TCB for PE, PP at high temperature)

- Narrow dispersity polymer standards for calibration

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve the virgin and recycled polymer samples in the eluent at a concentration of ~1–2 mg/mL. Agitate gently for several hours until fully dissolved. Filter the solution through a 0.45 µm PTFE syringe filter [30].

- System Calibration: Run a series of narrow MWD standards to create a calibration curve of log(Molecular Weight) vs. elution time/volume.

- Chromatographic Run:

- Set the appropriate flow rate (e.g., 1.0 mL/min for THF) and column temperature.

- Inject the filtered sample solution and acquire the chromatogram.

- Data Analysis:

- Use the calibration curve to calculate the number-average (Mₙ) and weight-average (M𝓌) molecular weights, and the polydispersity index (Đ = M𝓌/Mₙ) for both virgin and recycled samples.

- A decrease in Mₙ and M𝓌 indicates chain scission. An increase in Đ suggests a broadening of the MWD, often due to simultaneous degradation processes [3].

Analytical Techniques for Polymer Degradation

Table 1: Key Characterization Techniques for Recycling Research

| Technique | Measures | Information Obtained | Application in Recycling Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rheology [28] | Zero-shear viscosity (η₀), Steady-state compliance (Jₑ⁰), Relaxation spectrum | Molecular weight changes, branching/cross-linking, melt stability | Quick assessment of degradation extent after reprocessing; quality control for recycled pellet batches. |

| FTIR Spectroscopy [16] [29] | Absorbance of specific chemical bonds (e.g., C=O, O-H) | Formation of oxidation products, chemical composition, polymer identification | Tracking thermo-oxidative degradation; identifying contaminants in sorted waste streams. |

| SEC/GPC [16] [3] [30] | Molecular weight distribution, Mₙ, M𝓌, Đ | Direct measure of chain scission and cross-linking | Quantifying the molecular damage from multiple processing cycles; establishing processing-structure relationships. |

| Thermal Analysis (TGA) [30] | Weight loss as a function of temperature | Thermal stability, filler content, volatile degradation products | Determining the processing temperature window for recycled materials; analyzing additive content. |

Table 2: Spectroscopic Signatures of Polymer Degradation

| Polymer | Degradation Type | Key Spectral Changes (Wavenumber, cm⁻¹) | Assigned Chemical Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyolefins (PE, PP) [16] [29] | Thermal-Oxidative | ~1715 (s), ~3400 (broad) | Formation of carbonyl groups (ketones, acids); formation of hydroperoxides and alcohols. |

| Polyesters (PET, PLA) [3] | Hydrolysis | ~1715 (broadening), ~3500 (broad) | Increase in terminal carboxylic acid groups; increase in hydroxyl groups. |

| General | Chain Scission | Changes in fingerprint region (1400-600) | Alterations in crystallinity bands and chain end groups. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Polymer Degradation Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Antioxidants (e.g., Hindered phenols, Phosphites) [3] | Stabilize polymer melts during processing and analysis by scavenging free radicals and decomposing hydroperoxides. | Added to recycled polymer melts during rheological testing to prevent additional thermal-oxidative degradation from affecting the measurement [3]. |

| HPLC/SEC Grade Solvents (e.g., THF, TCB) [32] [30] | Act as the mobile phase for SEC/GPC; must be pure and degassed to prevent column damage and baseline artifacts. | Dissolving polymer samples for SEC analysis to accurately determine molecular weight distribution after degradation [30]. |

| Compression Molded Films [29] | Create uniform, thin samples for transmission or ATR-FTIR spectroscopy, ensuring reproducible and quantitative results. | Preparing standardized samples from recycled pellets for reliable tracking of the carbonyl index evolution [29]. |

| Narrow Dispersity Polymer Standards [30] | Calibrate the SEC/GPC system to convert elution volume into molecular weight. | Essential for generating accurate molecular weight data for virgin and degraded polymers, allowing for direct comparison. |

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: Polymer Degradation Analysis Workflow. This chart illustrates the pathway from polymer reprocessing to degradation, resulting molecular changes, and the advanced characterization techniques used for detection.

Diagram 2: Molecular Pathways of Thermal-Oxidative Degradation. This diagram outlines the key radical-based reaction steps, including initiation, propagation (with and without oxygen), and termination, leading to chain scission or cross-linking.

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: My enzymatic depolymerization of PET is yielding low monomer quantities. What could be the cause?

Answer: Low yield in PET enzymatic depolymerization is frequently due to substrate crystallinity and inadequate pretreatment [33] [34]. The enzyme's inability to access the polymer chains is a major bottleneck.

- Problem Identification: Highly crystalline PET (common in bottles) has tightly packed polymer chains that resist enzyme binding. Performance is often overestimated when using non-industrial, amorphous PET substrates in experiments [33].

- Solution: Implement a thermal pretreatment step to amorphize the PET. Heating the polymer above its glass transition temperature (Tg) and rapidly cooling it can disrupt its crystalline structure, making it more susceptible to enzymatic attack [35] [34].

- Recommended Protocol:

- Grind PET waste into fine flakes (<1 mm).

- Heat flakes to 70-100°C for 10-30 minutes.

- Rapidly quench in liquid nitrogen or ice water.

- Use the amorphized flakes as substrate for depolymerization with PET-hydrolyzing enzymes (e.g., engineered LCC, IsPETase variants) [33].

FAQ 2: How can I improve the stability and activity of my enzyme in a chemoenzymatic cascade process?

Answer: Reaction incompatibility between chemical and biological steps is a common issue, often caused by residual catalysts, solvents, or extreme pH from the pretreatment [36].

- Problem Identification: Glycolysis catalysts (e.g., metal acetates) or acidic/alkaline conditions used in chemical depolymerization can denature enzymes in subsequent steps [36].

- Solution: Introduce a neutralization and purification step between the chemical and enzymatic stages. Alternatively, explore enzyme engineering to develop more robust variants tolerant to process conditions [36].

- Recommended Protocol (For Glycolysis + Enzymatic Hydrolysis):

- Perform glycolysis on PET with a zinc acetate catalyst and ethylene glycol at 200°C [36].

- Cool the reaction mixture and dilute it with a neutral pH buffer.

- Use liquid-liquid extraction to separate the glycolyzed products from the catalyst.

- Adjust the pH and temperature to the optimum conditions for the specific enzyme (e.g., PETase) before introducing it to the purified stream.

FAQ 3: My polymer substrate is a mixed waste stream. How do I approach depolymerization?

Answer: Mixed plastics, especially those containing non-hydrolysable polymers like PE or PP, require targeted pre-separation or advanced cascade strategies [35] [36].

- Problem Identification: Enzymes are highly specific. A PET hydrolase will not degrade polyolefins, leading to incomplete depolymerization of mixed feeds [34].

- Solution: For polyesters (PET, PLA) blended with other plastics, a chemoenzymatic cascade is promising. For complex mixes, invest in upstream sorting using AI-assisted NIR (Near-Infrared) spectroscopy, which can achieve separation accuracy up to 95% [26].

- Recommended Protocol (For PET/PE Blends):

- Sorting: Use density-based separation (e.g., sink-float in water) to separate PET (denser) from PE (less dense).

- Pretreatment: For the PE fraction, employ a chemical oxidation step (e.g., with a peroxy acid) to introduce oxygen-containing functional groups [36].

- Depolymerization: Subject the sorted PET fraction to enzymatic depolymerization. The oxidized PE can be funneled to a different recycling pathway, such as pyrolysis or further chemoenzymatic cascades [36].

Experimental Protocols for Monomer Recovery

Protocol 1: Standardized Enzymatic Depolymerization of PET

This protocol is optimized for post-consumer PET, based on guidelines for reproducible PET hydrolase research [33].

- Substrate Preparation:

- Obtain clear, post-consumer PET bottles.

- Remove labels and lids, then wash and dry.

- Mechanically grind into flakes and sieve to a size of 0.1-0.5 mm.

- Amorphize by heating at 75°C for 1 hour, then rapidly cool on ice.

- Reaction Setup:

- Prepare a 1 mL reaction mixture in a suitable buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer, pH 8.0).

- Use a substrate loading of 100 g/L of amorphized PET flakes.

- Add the purified PET hydrolase (e.g., LCC ICGC, FAST-PETase) to a final concentration of 1-5 µM.

- Incubation:

- Incubate the reaction at the enzyme's optimal temperature (typically 60-72°C for thermostable variants) with constant agitation (e.g., 200 rpm) for 24-72 hours [33].

- Monomer Recovery:

- Stop the reaction by heating to 95°C for 10 minutes.

- Centrifuge the mixture to separate insoluble solids from the liquid hydrolysate.

- Analyze the liquid phase for monomers (TPA, MHET, EG) using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) or Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS).

Protocol 2: Chemoenzymatic Depolymerization of Polyurethane (PU)

This two-step protocol converts polyether-based PU foam into its diamine monomer [36].

- Chemical Glycolysis Step:

- Charge a reactor with shredded PU foam and a 10-15 fold excess of ethylene glycol.

- Add a catalyst (e.g., diethanolamine or a metal complex) at 1-2 wt%.

- React under a nitrogen atmosphere at 180-200°C for 2-4 hours.

- Cool the mixture. The main product is a carbamate-terminated oligomer.

- Enzymatic Hydrolysis Step:

- Dilute the glycolysis product in a neutral, mild buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5).

- Add a recently discovered urethanase (e.g., enzymes identified from metagenomic screening) [36].

- Incubate at 30-40°C with shaking for 24-48 hours.

- The enzyme hydrolyzes the carbamate bonds, releasing toluene-2,4-diamine (TDA) and polyols.

- Recover TDA via extraction and confirm identity by GC-MS.

Table 1: Comparison of Plastic Recycling Method Yields and Conditions

| Polymer | Recycling Method | Reported Yield | Key Process Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| PET | Enzymatic Depolymerization [37] | ~56% (Overall process yield) | Enzyme (e.g., LCC), 72°C, pH 8.0 |

| PET | Chemical Glycolysis [37] | ≥90% | Metal catalyst, Ethylene Glycol, ~200°C |

| PET | Mechanical Recycling [37] | 70-90% | Melt extrusion & reprocessing |

| Polyamide (Nylon) | Chemical Hydrolysis [37] | High (Near-complete) | Strong acid, High Temperature & Pressure |

| Polyurethane (PU) | Chemoenzymatic Cascade [36] | Protocol established | Glycolysis (200°C) + Enzymatic hydrolysis (40°C) |

Table 2: Key Enzymes for Polymer Depolymerization

| Enzyme Class | Target Polymer(s) | Source / Example | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| PET Hydrolase (Type I) | PET | Leaf-branch compost cutinase (LCC) [33] | Hydrolyzes ester bonds in PET to TPA and EG |

| PET Hydrolase (Type IIb) | PET | IsPETase (Ideonella sakaiensis) [33] | Mesophilic hydrolysis of PET |

| Urethanase | Polyurethane (PU) | Metagenomically-derived enzymes [36] | Hydrolyzes urethane (carbamate) bonds |

| Cutinase (Fungal) | PET, PEF | Fusarium species [33] | Hydrolyzes cutin and synthetic polyesters |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Experimental Workflow for Monomer Recovery

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Depolymerization Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| PET Hydrolase (e.g., LCC ICGC) | Primary biocatalyst for PET depolymerization | Hydrolyzing PET bottle flakes into TPA and EG monomers [33]. |

| Urethanase | Biocatalyst for breaking urethane links | Depolymerizing glycolyzed PU foam into diamines and polyols [36]. |

| Ethylene Glycol | Solvent and reagent for glycolysis | Chemical pretreatment of PET or PU in chemoenzymatic cascades [36]. |

| Metal Acetate Catalysts (e.g., Zn(OAc)₂) | Catalyst for chemical depolymerization | Accelerating the glycolysis reaction of PET [36]. |

| Amorphized PET Flakes | Standardized substrate for enzyme screening | Ensuring reproducible assessment of novel PET hydrolases under industry-relevant conditions [33]. |

| m-Chloroperoxybenzoic acid (mCPBA) | Chemical oxidant for pre-treatment | Introducing functional groups into polyolefins (PE, PP) to enable subsequent biocatalytic steps [36]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Diagnosing Unexpected Melt Flow Rate (MFR) Changes

Problem: MFR measurements are significantly higher or lower than anticipated after repeated extrusion cycles, indicating potential degradation.

Investigation Procedure:

- Verify Test Conditions: Confirm MFR testing was performed under standard conditions (specified temperature and load, e.g., 190°C/2.16 kg for PE or 230°C/2.16 kg for PP) according to ISO 1133. Inconsistent pre-drying of hygroscopic materials (like PA6 or PLA) can cause volatile-induced bubbles and skewed results [38] [39].

- Determine Dominant Mechanism:

- MFR Increased: Suggests chain scission is dominant. This is common for polymers like PP [40] and PLA [38]. Confirm via Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) showing reduced molecular weight (Mw) [41] [38].

- MFR Decreased: Suggests cross-linking or long-chain branching (LCB) is dominant. This occurs in PE under oxidative conditions [11] [40]. Use rheology to identify increased complex viscosity and elasticity (e.g., via Van Gurp-Palmen plots) [11].

- Check for Oxidation:

- Perform Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. Look for new carbonyl (C=O) absorption peaks around 1700-1750 cm⁻¹, indicating thermal-oxidative degradation [40].

- Review processing parameters: Were extruder vents open to air? Was a nitrogen purge used? Oxygen availability significantly influences degradation pathways [11].

Resolution Actions:

- For Chain Scission: Incorporate primary (e.g., phenolic) and secondary (e.g., phosphite) antioxidants to inhibit radical-induced scission during processing.

- For Cross-linking: Ensure robust stabilization with primary antioxidants to prevent radical formation. Process under nitrogen inert gas purge if possible [11].

- Optimize Processing: Reduce extrusion temperature and screw speed to minimize thermal and shear stress [3].

Guide: Addressing Loss of Mechanical Properties

Problem: Recycled material exhibits excessive brittleness (reduced impact strength) or a sharp drop in elongation at break.

Investigation Procedure: