Precision Drug Delivery: 3D Printing Multi-Material Implants with Controlled Amorphous and Crystalline Regions

This article explores the advanced frontier of additive manufacturing for personalized medicine: the fabrication of multi-material medical devices and implants with precisely engineered amorphous and crystalline domains.

Precision Drug Delivery: 3D Printing Multi-Material Implants with Controlled Amorphous and Crystalline Regions

Abstract

This article explores the advanced frontier of additive manufacturing for personalized medicine: the fabrication of multi-material medical devices and implants with precisely engineered amorphous and crystalline domains. Targeted at researchers and pharmaceutical development professionals, we detail the scientific principles, methodologies (including fused deposition modeling and direct ink writing), and material science behind controlling solid-state phase distribution. The content covers foundational concepts of polymer crystallization, cutting-edge multi-material printing techniques, troubleshooting of interfacial adhesion and phase stability, and validation methods for performance. The synthesis of these intents demonstrates how controlled microstructure enables tunable drug release profiles, mechanical integrity, and degradation rates, paving the way for next-generation combination products and patient-specific therapies.

The Science of Solids: Understanding Amorphous vs. Crystalline Domains in 3D Printed Pharmaceuticals

Within the broader research on 3D printing multi-material parts with controlled amorphous and crystalline regions, the deliberate manipulation of a drug's solid-state phase emerges as a critical variable. This application note details how amorphous and crystalline domains within a printed medical device directly govern active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) release kinetics and the mechanical performance of the device itself. Mastery of this landscape is essential for creating next-generation, patient-specific drug-delivery systems.

Quantitative Impact of Solid-State Phase on Drug Release

The dissolution rate of an API is fundamentally dictated by its thermodynamic state. Amorphous solids, lacking long-range order, possess higher free energy and molecular mobility, leading to faster dissolution. Conversely, crystalline materials are more stable and dissolve slower. This directly translates to programmable release profiles in 3D-printed dosage forms.

Table 1: Comparative Properties & Release Kinetics of Solid-State Phases

| Property | Amorphous Solid | Crystalline Solid | Impact on Drug Release |

|---|---|---|---|

| Free Energy | High | Low | Amorphous: Higher driving force for dissolution. |

| Aqueous Solubility | Higher (metastable) | Lower (equilibrium) | Amorphous can provide supersaturation, enhancing bioavailability. |

| Dissolution Rate | Rapid initial burst | Slower, constant | Amorphous facilitates immediate release; crystalline enables sustained release. |

| Physical Stability | Low (prone to recrystallization) | High | Crystalline regions ensure shelf-life stability; amorphous regions require stabilization. |

| Typical Release Mechanism | Diffusion-controlled from a rubbery/polymer matrix | Erosion or diffusion-controlled from a glassy/polymer matrix | Combined phases allow for complex, multi-phasic release profiles. |

Protocols for Phase Characterization and Analysis

Protocol 2.1: Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) for Phase Identification

Purpose: To identify and quantify amorphous and crystalline content within a 3D-printed part. Materials: DSC instrument, sealed aluminum crucibles, analytical balance.

- Precisely weigh 5-10 mg of sample from a specific region of the 3D-printed part.

- Seal the sample in an aluminum crucible. Use an empty crucible as reference.

- Run a heat-cool-heat cycle: Equilibrate at 25°C, heat to 20°C above the API's melting point at 10°C/min, cool to 25°C at 20°C/min, then re-heat at 10°C/min.

- Analysis: The first heating scan reveals the enthalpy of melting (ΔHf, J/g) for crystalline content. The glass transition temperature (Tg) appears as a step change in heat flow, indicating the amorphous phase. The degree of crystallinity can be calculated: Crystallinity (%) = (ΔHf,sample / ΔHf,100% crystalline reference) × 100.

Protocol 2.2: In Vitro Drug Release Testing from Multi-Phase Constructs

Purpose: To correlate spatially defined solid-state phases with release kinetics. Materials: USP Apparatus II (paddle), dissolution medium (e.g., phosphate buffer pH 6.8), 3D-printed multi-material tablet, fiber optic UV probes or HPLC for sampling.

- Using a controlled solvent deposition or multi-nozzle 3D printer, fabricate a bilayer tablet: one layer with API in amorphous solid dispersion (in polymer), the other with crystalline API in a rate-controlling polymer.

- Place the tablet in the dissolution vessel containing 900 mL of medium, maintained at 37°C ± 0.5°C. Paddle speed: 50 rpm.

- Automatically sample medium (or use in-situ probes) at pre-determined intervals (e.g., 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24 hours).

- Analyze API concentration via calibrated UV-Vis spectroscopy or HPLC.

- Data Modeling: Fit release data to models (e.g., zero-order, first-order, Higuchi, Korsmeyer-Peppas) to determine the dominant release mechanism for each phase region.

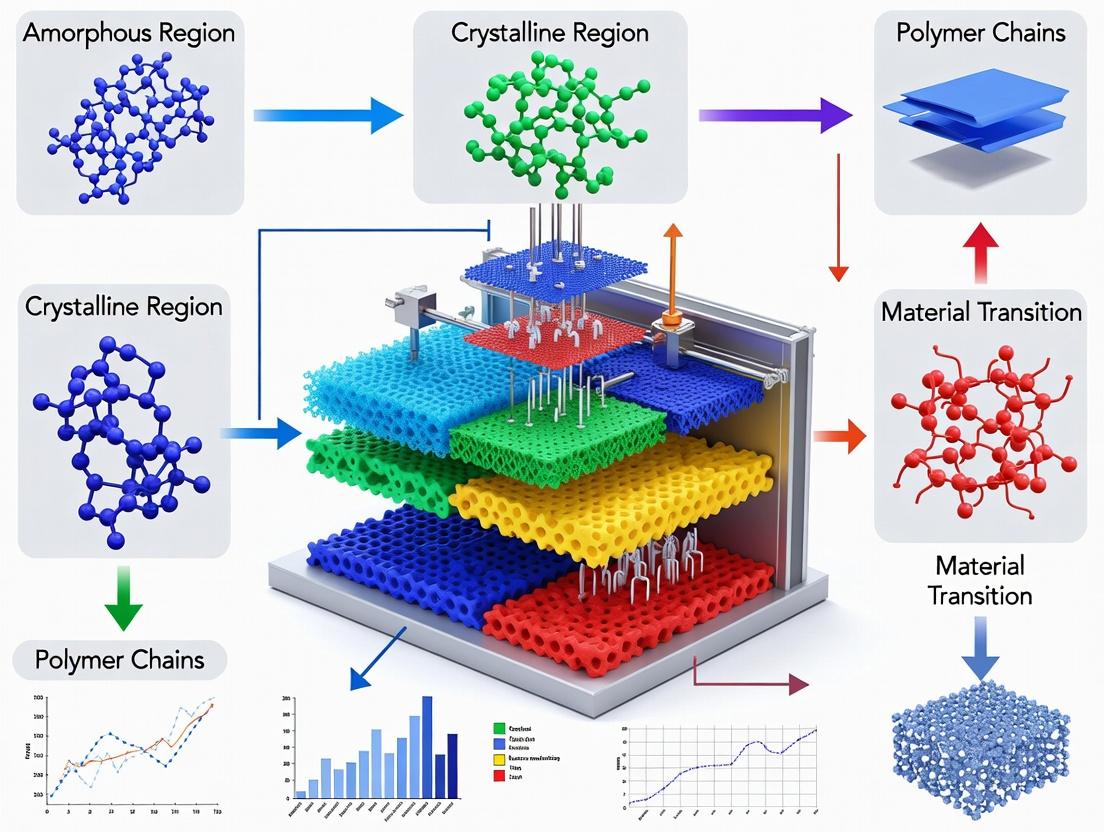

Visualizing the Solid-State-Property-Performance Relationship

(Diagram 1: From 3D Printing to Performance Outcomes)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Phase-Controlled 3D Printing of Drug Delivery Devices

| Item | Function | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrophobic Polymer Carrier | Forms a solid dispersion matrix, inhibits crystallization of amorphous API, controls release rate. | Eudragit RL/RS, Ethyl Cellulose, Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) |

| Hydrophilic Polymer Carrier | Enhances dissolution, stabilizes amorphous API, enables rapid release. | Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC), Soluplus |

| Plasticizer | Lowers polymer Tg, improves printability, prevents crack formation in amorphous domains. | Triethyl citrate, Polyethylene glycol (PEG 400), Dibutyl sebacate |

| Crystallization Inhibitor | Stabilizes the metastable amorphous phase within the device during storage. | Cellulose derivatives (HPMCAS), Surfactants (Poloxamer) |

| Model API (BCS Class II) | Poorly soluble, high-permeability drug where solid-state manipulation offers maximum benefit. | Itraconazole, Fenofibrate, Griseofulvin |

| Hot-Melt Extrusion (HME) Feedstock | Pre-formulated filament for Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) 3D printing, containing API-polymer blends. | Custom filaments of API + Eudragit E PO / PVA |

| Photopolymer Resin for SLA/DLP | Light-curable resin with dissolved or suspended API for vat polymerization, requiring phase stability post-cure. | PEGDA-based resins with photoinitiators and API |

Application Notes

Controlled crystallization within polymeric matrices is critical for tailoring the release kinetics, stability, and mechanical properties of 3D-printed multi-material parts, particularly in pharmaceutical and biomedical applications. This primer details the selection and use of key polymers and excipients to manipulate amorphous and crystalline domains.

Role of Polymers in Crystallization Control

Polymers act as crystallization modifiers by influencing nucleation and growth rates. Their chemical structure, molecular weight, and concentration determine the extent of API-polymer interactions, which can either inhibit or promote crystalline order.

- Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA): A hydrophilic polymer that forms strong hydrogen bonds with many APIs. It is highly effective in suppressing crystallization, stabilizing amorphous solid dispersions, and enabling rapid dissolution. Its excellent film-forming and gelation properties make it ideal for fused deposition modeling (FDM) 3D printing.

- Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA): A hydrophobic, biodegradable copolymer. The ratio of lactic to glycolic acid (LA:GA) determines crystallinity, degradation rate, and subsequent release profiles. PLGA can be used to create sustained-release matrices where API crystallization is kinetically trapped or deliberately induced over time.

- Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL): A semi-crystalline, biodegradable polyester with a low glass transition temperature (~ -60°C). It provides a flexible matrix where controlled API crystallization can be engineered through thermal annealing or solvent evaporation protocols, useful for long-term implantable devices.

Excipients as Crystallization Modulators

Excipients are used to fine-tune the crystallization environment.

- Nucleating Agents (e.g., Talc, Silica): Provide heterogeneous nucleation sites to promote controlled, fine-grained crystalline regions.

- Plasticizers (e.g., Triethyl Citrate, PEG): Increase polymer chain mobility, which can accelerate crystallization kinetics or, conversely, help maintain amorphous states by reducing glass transition temperature.

- Anti-plasticizers & Stabilizers (e.g., Poloxamers, HPMC): Inhibit molecular mobility, stabilizing metastable amorphous forms against recrystallization.

Table 1: Key Properties of Featured Polymers for Crystallization Control

| Polymer | Typical Mw Range (kDa) | Tg (°C) | Tm (°C) | Degradation Time | Primary Role in Crystallization Control | Solubility Parameter (δ, MPa^1/2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVA | 30-150 | ~85 | ~230 | Non-degrading | Amorphous Stabilizer | 25.8-29.1 |

| PLGA 50:50 | 10-100 | 45-55 | Amorphous | 1-2 months | Degradation-Triggered Crystallization | 19.4-21.0 |

| PLGA 85:15 | 10-100 | 50-55 | ~160 | 5-6 months | Crystalline Matrix | 19.0-20.5 |

| PCL | 14-80 | ~(-60) | 58-65 | >24 months | Crystallizable Matrix | 17.1-19.0 |

Table 2: Effect of Common Excipients on Crystallization Kinetics

| Excipient (Type) | Example | Typical Conc. (% w/w) | Effect on Crystal Growth Rate | Primary Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Talc (Nucleating Agent) | Magnesium silicate | 0.1-2.0 | Increase (>200%) | Provides heterogeneous nucleation sites |

| Poloxamer 188 (Stabilizer) | PEO-PPO-PEO block copolymer | 5-20 | Decrease (50-70%) | Inhibits surface nucleation, increases solubility |

| Triethyl Citrate (Plasticizer) | - | 10-30 | Variable (Increase/Decrease) | Modifies polymer chain mobility (Tg reduction) |

| HPMC (Inhibitor) | Hypromellose | 5-30 | Decrease (60-90%) | Viscosity enhancement, molecular mobility inhibition |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of Polymer/API Filaments for FDM 3D Printing with Controlled Crystallinity

Objective: To produce homogeneous polymer-API filaments with a defined amorphous or crystalline API state. Materials: Polymer (PVA, PLGA, or PCL), API (e.g., Itraconazole), plasticizer (if needed), twin-screw hot melt extruder (HME), filament spooler, vacuum oven. Procedure:

- Pre-mixing: Pre-blend the polymer and API at the target ratio (e.g., 70:30 w/w) using a mortar and pestle or turbula mixer for 15 minutes.

- Hot Melt Extrusion: Set HME barrel temperature profile based on polymer Tm/Tg. For PVA: 150-190°C; PLGA: 80-120°C; PCL: 70-100°C. Feed rate: 0.2-0.5 kg/h. Screw speed: 50-100 rpm.

- Filament Collection: Use a calibrating puller unit to achieve a consistent filament diameter of 1.75 ± 0.10 mm. Spool immediately.

- Post-Processing (Annealing for Crystallization): For PCL/API filaments, anneal at 45°C (between Tg and Tm of PCL) for 24h in a vacuum oven to induce controlled API crystallization within the flexible matrix.

- Characterization: Assess filament diameter uniformity, API state by XRD, and thermal properties by DSC.

Protocol 2: In-situ Monitoring of API Crystallization in a PLGA Film

Objective: To quantify the rate of API crystallization during solvent evaporation from a polymer film. Materials: PLGA (50:50), API (e.g., Ritonavir), organic solvent (dichloromethane), spin coater, polarized optical microscope (POM) with hot stage, image analysis software. Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve PLGA and API (80:20 w/w) in DCM at 10% w/v total solid content. Stir until clear.

- Film Casting: Deposit 100 µL of solution onto a clean glass slide. Spin-coat at 1500 rpm for 60s to create a thin, uniform film.

- In-situ Crystallization Monitoring: Immediately transfer the wet film to the POM stage. Initiate time-lapse imaging (1 frame/minute) under cross-polarizers for 120 minutes.

- Environmental Control: Maintain stage at 25°C and controlled humidity (30% RH) using an environmental chamber.

- Data Analysis: Use image analysis to quantify the increase in birefringent crystalline area over time. Plot % crystalline area vs. time to derive crystallization kinetics.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Pathways to Control Crystallinity

Diagram 2: Factors Governing Crystallization Outcome

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Controlled Crystallization Experiments

| Item / Reagent | Example Product/Catalog | Primary Function in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | Sigma-Aldrich, 363170 (Mw ~145,000, 99+% hydrolyzed) | Forms hydrogen bonds to inhibit API crystallization; primary matrix for water-soluble prints. |

| PLGA (50:50) | Lactel (DURECT Corp), B6010-2 (IV 0.55-0.75 dL/g) | Hydrophobic, amorphous copolymer for degradation-mediated crystallization control. |

| Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) | Sigma-Aldrich, 704105 (Mw 45,000) | Semi-crystalline, flexible matrix for engineering crystalline domains via annealing. |

| Model Crystallizing API | Itraconazole (Sigma-Aldrich, I6657) | A BCS Class II drug with well-characterized crystallization tendencies from polymers. |

| Hot Melt Extruder (HME) | HAAKE Minilab II (Thermo Scientific) | For lab-scale production of homogeneous polymer-API filaments with controlled thermal history. |

| Polymer-Compatible Plasticizer | Triethyl Citrate (Sigma-Aldrich, 90260) | Reduces polymer Tg to modify chain mobility and crystallization kinetics during processing. |

| Nucleating Agent | Talc (Sigma-Aldrich, 243604) | Provides sites for heterogeneous nucleation to induce controlled crystal growth. |

| Polarized Optical Microscope (POM) | Olympus BX53 with Linkam hot stage | For in-situ visualization and quantification of crystal nucleation and growth in films. |

This application note details the thermodynamic and kinetic principles governing polymer crystallization during material extrusion additive manufacturing (AM). The control of crystallization is paramount for the broader research thesis on 3D printing multi-material parts with spatially controlled amorphous and crystalline regions. Such control enables the fabrication of components with tailored mechanical properties (e.g., toughness vs. stiffness), degradation profiles (for drug delivery), and optical characteristics. Crystallinity directly influences the performance and predictability of printed polymers, making its understanding critical for advanced applications in biomedical devices and pharmaceutical development.

Foundational Principles: Thermodynamics and Kinetics

Thermodynamics dictates the driving force for crystallization, defined by the difference in free energy between the molten and crystalline states ((\Delta G = \Delta H - T \Delta S)). Crystallization occurs spontaneously below the equilibrium melting temperature ((Tm^0)) when (\Delta G < 0). The degree of supercooling ((\Delta T = Tm^0 - T_c)) is the primary thermodynamic driver.

Kinetics describes the rate and mechanism of crystallization, typically modeled by the Avrami equation: (1 - Xt = \exp(-K t^n)), where (Xt) is the crystalline fraction at time (t), (K) is the crystallization rate constant, and (n) is the Avrami exponent related to nucleation and growth dimensionality.

Table 1: Crystallization Kinetics Parameters for Common AM Polymers

| Polymer | (T_m^0) (°C) | Typical (T_c) in AM (°C) | Avrami Exponent (n) | Half-time of Crystallization, (t_{1/2}) (s) at (\Delta T) = 30°C | Max. Crystallinity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(Lactic Acid) (PLA) | 180 | 100-130 | 2.5 - 3.0 | 40 - 80 | ~35 |

| Polypropylene (PP) | 185 | 110-140 | 2.0 - 3.0 | 10 - 30 | ~50 |

| Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) | 395 | 290-320 | 2.0 - 2.5 | 5 - 20 | ~35 |

| Poly(ε-Caprolactone) (PCL) | 70 | 30-50 | 2.0 - 2.8 | 200 - 500 | ~70 |

| Nylon (PA6) | 260 | 180-210 | 2.0 - 2.5 | 15 - 40 | ~30 |

Table 2: Effect of AM Process Parameters on Crystallinity

| Process Parameter | Effect on Crystallization Temperature ((T_c)) | Effect on Overall Crystallinity | Primary Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nozzle/Bed Temperature (↑) | Increases | Decreases | Reduced supercooling ((\Delta T)) |

| Print Speed (↑) | Decreases | Increases (up to a limit) | Faster cooling, higher (\Delta T); potential for shear-induced nucleation |

| Layer Height (↓) | Increases | Decreases | Enhanced thermal history from previous layers reduces cooling rate |

| Flow Rate/Extrusion Multiplier (↑) | Increases | Variable (can increase) | Increased shear stress promotes row-nucleation |

| Active Bed Cooling (ON) | Decreases Significantly | Increases (up to a limit) | Rapid quench creates more nucleation sites; may limit spherulite growth |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In-Situ Crystallinity Monitoring During Printing via Rheo-Optics

Objective: To correlate real-time polymer crystal formation with extrusion and thermal conditions. Materials: Filament extrusion 3D printer modified with optical viewport, polarized light source and high-speed camera, IR pyrometer, PLA or PCL filament. Procedure:

- Setup: Modify a print head to include a quartz glass nozzle tip. Align polarized filters (cross-polarized) with a high-speed camera (≥100 fps) focused on the extrudate immediately exiting the nozzle.

- Calibration: Correlate birefringence intensity (image grayscale value) with known crystallinity standards (from DSC) for the polymer.

- Printing & Data Acquisition: Print a single-wall rectilinear pattern at varying nozzle temperatures (e.g., 180°C to 220°C for PLA) and print speeds (20-80 mm/s).

- Synchronize IR pyrometer temperature readings of the extrudate surface with the camera frames.

- Analysis: Use image analysis software to plot birefringence intensity (proxy for crystallinity development) vs. time and distance from the nozzle.

Protocol 2: Post-Print Structural Analysis for Spatial Crystallinity Mapping

Objective: To map the spatial distribution of crystalline and amorphous regions in a printed part. Materials: Printed polymer sample, microtome, Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC), Polarized Optical Microscope (POM), FT-IR microscope. Procedure:

- Sectioning: Use a microtome to prepare thin slices (5-10 µm) from the printed part along the three principal axes (XY-plane, XZ-side view, YZ-side view).

- POM Imaging: Observe slices under cross-polarized light. Spherulites and crystalline structures will appear bright against a dark amorphous background. Document morphology and size distribution.

- FT-IR Microscopy Mapping: Perform mapping in transmission or ATR mode across the sample slice. Monitor the crystallinity-sensitive absorption band (e.g., for PLA, the 955 cm⁻¹ band vs. the 918 cm⁻¹ amorphous band). Generate a 2D crystallinity index map.

- DSC Validation: Perform DSC (10°C/min heating rate) on small, precisely located samples dissected from different regions (e.g., inter-layer weld, core of a raster) to quantify local crystallinity from the melting enthalpy.

Visualizations

Title: Polymer Crystallization Pathway During Cooling

Title: AM Process to Property Relationship

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Polymer Crystallization Studies in AM

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Model Polymers | Provide defined baseline for crystallization studies. | PLA (slow crystallizer), PCL (fast crystallizer), PEEK (high-performance). |

| Nucleating Agents | Increase nucleation density, fine-tune crystal size/distribution. | Talc (for PP), Boron Nitride (for PEEK), specific organic nucleants (e.g., TMB-5 for PLA). |

| Plasticizers | Modify chain mobility and glass transition temperature (Tg), altering crystallization kinetics. | Polyethylene glycol (PEG) for PLA, Dioctyl Phthalate for various polymers. |

| Thermal Stabilizers | Prevent degradation during prolonged melt states in the nozzle, ensuring consistent crystallization baseline. | Phosphites, hindered phenols (e.g., Irgafos 168, Irganox 1010). |

| Fluorescent Dyes | Enable visualization of crystalline morphology via fluorescence microscopy (some dyes segregate into amorphous regions). | Nile Red, 2-(2-Hydroxyphenyl)benzothiazole. |

| Calibration Standards | For quantitative crystallinity measurement techniques (DSC, XRD). | Indium (DSC cal.), Fully amorphous and annealed crystalline samples of the target polymer. |

| Isothermal Stage | Attachable to printer or used post-print to precisely control Tc for kinetic studies. | Peltier-controlled heating stage (±0.1°C). |

Application Notes

The targeted spatial control of amorphous and crystalline phases within 3D printed structures represents a frontier in advanced manufacturing, with profound implications for aerospace, biomedical devices, and controlled drug delivery. Recent breakthroughs leverage multi-material printing, in-situ monitoring, and novel energy deposition techniques to dictate local microstructure with high precision. This capability enables the fabrication of parts with site-specific mechanical, thermal, and dissolution properties from a single material feedstock by controlling its solid-state phase.

Key Application Areas:

- Graded Drug Eluting Implants: Spatially controlled crystallinity in polymeric matrices (e.g., PCL, PEEK) allows for tunable degradation rates and staged drug release profiles within a single implant.

- Functionally Graded Alloys: In metals, controlling amorphous (metallic glass) versus crystalline regions within a part can engineer surfaces with high hardness and wear resistance coupled with a tough, ductile core.

- Photonic & Electronic Devices: For semiconductors and optical materials, phase patterning dictates bandgap and refractive index, enabling embedded waveguides or sensors.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multi-Material Jetting for Polymer Phase Gradients

Objective: To fabricate a polymer part with defined crystalline and amorphous regions using drop-on-demand (DoD) printing of a single polymer with differential thermal histories. Materials: Polycaprolactone (PCL) filament, Solvent (Chloroform), Multi-material inkjet printer (e.g., Stratasys J750), Hot plate, Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC).

- Ink Formulation: Dissolve PCL pellets in chloroform (15% w/v). Filter the solution (0.45 μm pore size) to remove particulates.

- Printer & Substrate Setup: Load the PCL ink into a printhead cartridge. Set the build platform temperature to 60°C (above PCL's glass transition but below its melting point for controlled crystallization).

- Gradient Design & Printing: Design a digital mask where "Region A" receives a standard droplet volume. "Region B" receives 50% reduced droplet volume to facilitate faster cooling.

- In-situ Crystallization Control: For Region A (target: higher crystallinity), after printing each layer, expose the layer to a 70°C anneal for 60 seconds on the build plate. For Region B (target: amorphous/low crystallinity), immediately after deposition, activate a directed air jet (25°C) for 10 seconds to quench the layer.

- Post-Processing: After print completion, slowly cool the entire part to room temperature over 2 hours. Characterize phase distribution via DSC mapping and micro-Raman spectroscopy.

Protocol 2: Laser-Powder Bed Fusion (L-PBF) for Metallic Glass-Crystal Composites

Objective: To spatially control the formation of crystalline phases within a metallic glass matrix using modulated laser energy density. Materials: Gas-atomized Zr-based metallic glass powder (e.g., AMZ4), Commercial L-PBF system, Argon gas supply, Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) with EBSD.

- Powder Preparation: Dry the powder at 120°C in a vacuum oven for 4 hours. Sieve to a particle size range of 15-45 μm.

- Energy Density Modulation: Create a build file with alternating scan strategies.

- Zone 1 (Amorphous): Use high laser power (P=300W), high scan speed (v=2000 mm/s), and hatch spacing (h=0.10 mm) to achieve a volumetric energy density, Ev = P/(vhlayer thickness), of ~50 J/mm³, promoting ultra-rapid melting and quenching.

- Zone 2 (Crystalline): Use lower power (P=150W), slower speed (v=500 mm/s), and pre-heat the powder bed to 400°C to induce partial devitrification and crystal growth.

- Process Execution: Conduct the build in an argon atmosphere with O₂ < 100 ppm. Monitor melt pool stability via coaxial photodiode.

- Analysis: Section the part. Prepare metallographic samples. Etch with Kroll's reagent. Analyze using EBSD to map crystalline fractions against processing parameters.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Process Parameters & Resulting Phase Fractions in L-PBF of AMZ4 Alloy

| Zone ID | Laser Power (W) | Scan Speed (mm/s) | Bed Pre-heat (°C) | Vol. Energy Density (J/mm³) | Crystalline Fraction (%) | Vickers Hardness (HV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone 1 | 300 | 2000 | 25 | 50 | 5 ± 2 | 580 ± 15 |

| Zone 2 | 150 | 500 | 400 | 120 | 65 ± 8 | 420 ± 25 |

| Zone 2* | 180 | 1000 | 400 | 72 | 30 ± 5 | 510 ± 20 |

Note: Data is representative. Zone 2 illustrates an intermediate parameter set.*

Table 2: Thermal Protocols for Graded Crystallinity in Printed PCL Structures

| Region | Droplet Volume (pL) | Substrate Temp (°C) | Post-Deposition Quench | Anneal Temp/Time | Final Crystallinity (%) | Drug Release T₅₀ (days)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core | 100 | 60 | None | 70°C / 60s | 45 ± 3 | 28 ± 2 |

| Shell | 50 | 60 | 25°C Air, 10s | None | 18 ± 4 | 7 ± 1 |

T₅₀: Time for 50% release of a model hydrophilic drug (e.g., Metformin).

Visualizations

Workflow for Spatial Phase Control in 3D Printing

Energy Input & Cooling Rate Determine Final Phase

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item Name | Function / Role in Phase Control | Example Product / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Model Polymer (PCL) | A biodegradable, semi-crystalline polymer with tunable crystallization kinetics via thermal history. | Polycaprolactone, Mn 80,000, Sigma-Aldrich 440744 |

| Metallic Glass Powder | Base feedstock for creating amorphous-crystalline composites via controlled devitrification. | Gas-atomized Zr₅₉.₃Cu₂₈.₈Al₁₀.₄Nb₁.₅ (AMZ4), size 15-45 μm |

| Controlled Atmosphere Chamber | Prevents oxidation of reactive metals and polymers during high-temperature processing. | Argon-filled glovebox, O₂ & H₂O < 1 ppm |

| In-situ Pyrometer/Photodiode | Monitors melt pool temperature and stability in real-time, correlating to cooling rate. | Coaxial two-color pyrometer integrated into L-PBF system |

| Micro-Raman Spectrometer | Maps spatial distribution of crystalline and amorphous phases non-destructively. | Confocal Raman microscope with 532 nm laser |

| Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD) Detector | Provides crystallographic orientation maps and quantifies local crystalline fraction. | EDAX Hikari XP EBSD system on an SEM |

| Programmable Hot Stage | Provides precise, spatially variable thermal profiles for in-situ annealing/quenching. | Linkam THMS600 stage with liquid nitrogen cooling |

| Graded Crystallinity Model Drug | A hydrophilic API used to validate release profiles from phase-graded polymer matrices. | Metformin HCl, USP grade |

From Design to Fabrication: Techniques for Multi-Material Printing with Spatial Phase Control

Application Notes & Comparative Analysis

The fabrication of multi-material parts with controlled amorphous and crystalline regions is pivotal for advanced applications in pharmaceuticals and biomedical devices. This pursuit demands precise spatial control over material deposition and energy delivery to dictate solid-state form. The following table summarizes the core capabilities of three key additive manufacturing technologies in this context.

Table 1: Core Technology Comparison for Solid-State Control

| Feature | Multi-Nozzle FDM | Direct Ink Writing (DIW) | Volumetric Printing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Melt extrusion and layer deposition | Paste/gel extrusion and layer deposition | Photopolymerization within a rotating resin volume |

| Typical Materials | Thermoplastic polymers (e.g., PVA, PVP, Eudragit), drug-polymer filaments | Hydrogels, polymer solutions, particle-laden pastes, APIs in carrier inks | Photopolymerizable resins (e.g., PEGDA), with dissolved/mixed APIs |

| Spatial Resolution | 100 - 400 µm | 1 - 500 µm | 50 - 300 µm |

| Key Variable for Solid-State Control | Nozzle/Print Bed Temperature, Cooling Rate | Solvent Evaporation Rate, Gelation Kinetics | Photopolymerization Rate, Radical/Oxygen Inhibition |

| Amorphous Region Suitability | High (via rapid cooling of polymer-drug melt) | High (via solvent quenching or kinetic trapping) | Moderate (kinetic trapping possible, but crosslinking may induce crystallization) |

| Crystalline Region Suitability | Low-Medium (requires controlled slow cooling, often challenging) | High (via controlled solvent evaporation or anti-solvent diffusion) | Low (photocuring typically disrupts crystallization) |

| Multi-Material Capability | High (discrete nozzles for different materials) | High (multi-channel printheads, switching) | Low (typically single vat, though resin exchange possible) |

| Representative Throughput | Moderate (10-100 mg/hr) | Low-Moderate (1-50 mg/hr) | High (parts in seconds/minutes) |

| Primary Advantage for Thesis | Robust multi-material fabrication; good for amorphous solid dispersions. | Gentle processing; excellent for crystalline particle embedding or co-deposition. | Speed and geometric freedom; potential for unique encapsulated structures. |

| Primary Limitation for Thesis | High thermal stress; limited control over crystallization. | Post-print drying/gelation critical and difficult to control uniformly. | Limited material scope; difficult to prevent unintended crystallization post-print. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 2.1: Fabricating Bi-Layered Amorphous-Crystalline Constructs via Multi-Nozzle FDM

Objective: To fabricate a dual-compartment tablet with an amorphous solid dispersion layer and a crystalline API-containing layer.

- Material Preparation:

- Nozzle 1 (Amorphous Layer): Prepare a hot-melt extruded filament of 20% w/w Itraconazole in Soluplus. Diameter: 1.75 mm ± 0.05 mm.

- Nozzle 2 (Crystalline Layer): Prepare a pure PEG 1500 filament or a physical mixture filament of 10% w/w Milled Ibuprofen crystals in PCL. Diameter: 1.75 mm ± 0.05 mm.

- Printer Setup: Utilize a dual-extrusion FDM printer (e.g., customized Prusa i3 MK3S+). Calibrate nozzle alignment to within 0.1 mm.

- Printing Parameters:

- Nozzle 1 (Amorphous): Nozzle Temp: 185°C; Bed Temp: 70°C; Layer Height: 0.2 mm; Print Speed: 15 mm/s; Cooling Fan: 100%.

- Nozzle 2 (Crystalline): Nozzle Temp: 70°C (PEG) or 90°C (PCL); Bed Temp: 40°C; Layer Height: 0.2 mm; Print Speed: 20 mm/s; Cooling Fan: 0%.

- Process: Print the amorphous layer first directly onto the build plate. Upon completion, the print head switches to Nozzle 2 and prints the crystalline layer atop the first layer without pause.

- Post-Processing: Immediately transfer prints to a desiccator containing silica gel for 24 hours to anneal any residual stresses and stabilize the solid state.

Protocol 2.2: Direct Ink Writing of Gradient Crystallinity Constructs

Objective: To create a scaffold with a spatial gradient of API crystallinity using a co-axial printhead.

- Ink Formulation:

- Core Ink: Saturated solution of Griseofulvin (10 mg/mL) in Dichloromethane (DCM) loaded into a 5 mL Luer-lock syringe.

- Sheath Ink: 2% w/w Sodium Alginate in deionized water, loaded into a 10 mL syringe.

- Printer Setup: Use a pneumatically assisted DIW system with a co-axial nozzle (inner diameter: 200 µm, outer: 600 µm). Connect syringes to independent pressure regulators.

- Printing Parameters: Bed Temp: 25°C; Deposition Speed: 5 mm/s; Core Ink Pressure: 10 kPa; Sheath Ink Pressure: 15 kPa. Print into a 100 mM Calcium Chloride bath for instantaneous alginate gelation.

- Crystallinity Gradient Creation: The gradient is achieved by programming a gradual, linear increase in the bed temperature from 25°C to 40°C along a 50 mm print path. This controls the DCM evaporation rate, inducing faster crystallization at the higher temperature end.

- Post-Printing: Immerse the printed structure in fresh CaCl₂ bath for 30 min for complete gelation. Rinse gently with DI water and air-dry for 12 hours under ambient conditions.

Protocol 2.3: Volumetric Printing of Encapsulated API Reservoirs

Objective: To volumetrically print a hollow, permeable hydrogel sphere encapsulating a crystalline API suspension.

- Resin Preparation: In low-actinic glassware, prepare a resin comprising: 20% w/w PEGDA (700 Da), 3% w/w Lithium Phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) photoinitiator, 0.5% w/w Sudan I (photoadsorber), and 76.5% w/w Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS).

- Loading & Printing:

- Gently mix 1% w/w of crystalline Naproxen particles (<50 µm) into the resin just prior to printing.

- Inject 1 mL of the suspension-resin into a cylindrical glass vial (Ø22 mm).

- Place vial in a volumetric printer (e.g., xolography or computed axial lithography system). Project the computed series of 2D light patterns (λ = 455 nm, 20 mW/cm²) while rotating the vial 360° over a total exposure time of 30 seconds. The pattern corresponds to a hollow sphere (Ø2 mm) with a micro-lattice shell.

- Post-Printing & Harvest: After exposure, decant the un-polymerized resin. The encapsulated API suspension is trapped within the sphere. Gently rinse the sphere in PBS for 60 minutes to remove residual monomer and initiator.

Diagrams

Title: Technology Selection for Microstructure Control

Title: Workflow for Solid-State Controlled 3D Printing

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Multi-Material 3D Printing

| Item | Primary Function | Relevance to Thesis |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrophilic Polymers (Soluplus, PVP VA64) | Carrier matrix for amorphous solid dispersions. Inhibits crystallization via molecular mixing and hydrogen bonding. | Essential for FDM and DIW fabrication of amorphous regions. |

| Photopolymerizable Monomers (PEGDA, GelMA) | Form the hydrogel/scaffold matrix upon light exposure. Degree of crosslinking controls diffusivity. | Enables volumetric and DIW printing; mesh size can influence API release and crystallization kinetics. |

| Photorinitiators (LAP, TPO) | Generate radicals upon light exposure to initiate polymerization. Concentration controls cure depth and rate. | Critical for volumetric and stereolithography prints. Reaction exotherm can affect API solid state. |

| Thermal Stabilizers (BHT, Vitamin E) | Antioxidants that prevent polymer degradation during high-temperature FDM processing. | Maintains polymer molecular weight and prevents API degradation in the melt. |

| Co-Solvents (DMSO, Ethanol) | Adjust ink rheology for DIW and modulate solvent evaporation rate to control crystallization. | Primary tool for tuning crystallization kinetics in DIW processes. |

| Plasticizers (Triacetin, PEG 400) | Lower polymer glass transition temperature (Tg), improving printability in FDM and film formation in DIW. | Reduces required print temperature, mitigating thermal stress on API. Can impact physical stability of amorphous dispersions. |

| Crystallization Inhibitors (HPMC, PVP) | Added to inks or resins to kinetically trap metastable amorphous forms or suppress crystal growth. | Directly enables the creation and stabilization of amorphous regions within printed constructs. |

| Model APIs (Griseofulvin, Itraconazole, Ibuprofen) | Poorly soluble crystalline drugs (BCS Class II) used as benchmark compounds. | Standard substrates for evaluating technology efficacy in generating and controlling different solid-state forms. |

Application Notes

These Application Notes detail the use of material strategies for phase programming in multi-material 3D printing, specifically for creating parts with controlled spatial distributions of amorphous and crystalline phases. This capability is critical for advanced applications in drug delivery and biomedical devices, where release kinetics, degradation profiles, and mechanical performance must be precisely engineered.

Blends: Homogeneous mixtures of two or more polymers (e.g., PVP and PCL) allow for the tuning of bulk properties. The ratio of amorphous to crystalline polymers directly influences glass transition temperature (Tg), crystallinity, and dissolution rate. This is a foundational strategy for creating monolithic parts with predictable, averaged properties.

Gradients: By continuously varying the composition of a blend along one or more spatial axes during printing, it is possible to engineer continuous property transitions. This is instrumental for creating implants with stiffness gradients that match bone-to-soft-tissue interfaces or for tablets with sequential drug release profiles.

Core-Shell Designs: This concentric, multi-material approach decouples the functionality of a part's interior from its exterior. A crystalline polymer core can provide structural integrity, while an amorphous polymer shell can control initial wetting and release. This design offers the most precise spatiotemporal control over phase-dependent properties.

The selection of strategy depends on the desired property profile: blends for uniform properties, gradients for smooth transitions, and core-shell for sharp, functional interfaces. Successful implementation requires precise control over printing parameters, material rheology, and post-processing thermal protocols to achieve the target phase morphology.

Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of Amorphous-Crystalline Polymer Blends for Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM)

Objective: To prepare, characterize, and 3D print filament composed of a blend of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, amorphous) and polycaprolactone (PCL, crystalline) for controlled drug elution.

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" Table 1. Equipment: Twin-screw micro-compounder, filament winder, desktop FDM 3D printer, differential scanning calorimeter (DSC), X-ray diffractometer (XRD).

Procedure:

- Pre-drying: Dry PVP and PCL granules separately in a vacuum oven at 50°C for 12 hours.

- Melt Blending: Feed PVP and PCL at the desired weight ratio (e.g., 30:70, 50:50, 70:30) into a twin-screw micro-compounder. Process at 110°C with a screw speed of 50 rpm for 5 minutes to ensure homogeneous mixing.

- Filament Extrusion: Directly extrude the molten blend through a 1.75 mm diameter die. Use a filament winder to spool the material, maintaining consistent diameter (±0.05 mm).

- Filament Characterization:

- Thermal Analysis: Use DSC to determine Tg of the amorphous phase and melting temperature (Tm) and crystallinity (%) of the crystalline phase. Heating rate: 10°C/min.

- Crystallinity Confirmation: Use XRD to confirm the presence/absence of crystalline peaks.

- 3D Printing: Load filament into an FDM printer. Use a nozzle temperature between the Tg of the blend and the Tm of PCL (e.g., 80-90°C). Print benchmark structures (e.g., discs, tensile bars).

- Post-Printing Analysis: Repeat DSC/XRD on printed parts to assess phase stability during printing.

Protocol 2: Creating Radial Gradients via Multi-Material Direct Ink Writing (DIW)

Objective: To fabricate a cylindrical construct with a radial gradient in crystallinity, transitioning from a crystalline exterior to an amorphous interior.

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" Table 1. Equipment: Dual-channel pneumatic extrusion DIW system with mixing nozzle, syringes, controlled heating stage, rheometer.

Procedure:

- Ink Preparation: Prepare two ink reservoirs.

- Reservoir A (High Crystallinity): 25% w/w PCL in dimethyl carbonate.

- Reservoir B (High Amorphous): 30% w/w PVP in ethanol.

- Characterize viscosity vs. shear rate for each ink using a rheometer.

- System Setup: Load inks into separate syringes mounted on the DIW system. Connect to a static mixing nozzle (8 elements).

- Gradient Programming: Program the printer's deposition path for a concentric spiral (cylinder fill). Simultaneously, program the relative flow rates from Syringe A and Syringe B to change dynamically during printing.

- Start Point (Outer Wall): Flow Rate A: 100%, Flow Rate B: 0%.

- End Point (Center): Flow Rate A: 0%, Flow Rate B: 100%.

- Implement a linear gradient transition over the print path.

- Printing: Maintain stage temperature at 30°C to facilitate solvent evaporation. Print at a constant deposition speed (e.g., 8 mm/s) matched to the mixed ink's gelation kinetics.

- Post-Processing: Place printed cylinder in a vacuum desiccator for 48 hours to remove residual solvent.

- Gradient Validation: Section the cylinder and use micro-Raman or IR spectroscopy mapping across the radius to validate the compositional gradient.

Protocol 3: Core-Shell Fabrication using Coaxial Extrusion Additive Manufacturing

Objective: To print a core-shell filament in situ with a crystalline polymer core (PCL) and an amorphous polymer shell (Eudragit L100) for pH-dependent release.

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" Table 1. Equipment: Coaxial print head (inner and outer nozzles), precision syringe pumps (x2), UV cure station (if needed), pH-controlled dissolution apparatus.

Procedure:

- Core Solution: Prepare 40% w/w PCL in dichloromethane.

- Shell Solution: Prepare 35% w/w Eudragit L100 in ethanol. Add 1% w/w (relative to polymer) photoinitiator (Irgacure 2959).

- Print Head Setup: Mount core and shell solutions in separate syringes on independent pumps. Connect to coaxial nozzle (e.g., core: 22G, shell: 18G).

- Printing Parameters: Set core flow rate to 5 mL/hr and shell flow rate to 15 mL/hr to achieve a ~1:3 core:shell diameter ratio. Maintain ambient temperature.

- Deposition & Curing: Deposit core-shell filament in a designed pattern (e.g, mesh or capsule). Immediately expose the deposited structure to UV light (365 nm, 10 mW/cm² for 60 sec) to photopolymerize the Eudragit shell.

- Post-Printing: Air-dry for 24 hours to evaporate remaining solvents.

- Functionality Test: Place structure in a USP dissolution apparatus (pH 2.0 for 2 hrs, then pH 6.8). Sample periodically and use HPLC to quantify release of a model drug (e.g., theophylline) loaded in the core.

Data Tables

Table 1: Thermal and Physical Properties of PVP/PCL Blend Filaments

| PVP:PCL Ratio (w/w) | Glass Transition (Tg) °C | Melting Point (Tm) °C | Crystallinity (%) (from DSC) | Dissolution Time (50% Mass Loss, hrs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100:0 (Pure PVP) | 175 | N/A | 0 | <0.5 |

| 70:30 | 155 | 52 | 18 | 2.5 |

| 50:50 | 142 | 55 | 35 | 8.0 |

| 30:70 | N/D | 58 | 52 | >24 |

| 0:100 (Pure PCL) | N/A | 60 | 65 | N/A (Non-soluble) |

N/A = Not Applicable, N/D = Not Detectable

Table 2: Release Kinetics of Model Drug from Core-Shell Constructs

| Shell Material (Thickness ~150µm) | Core Material (+10% Drug) | % Release at pH 2.0 (2 hrs) | % Release at pH 6.8 (8 hrs) | Release Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eudragit L100 (pH-sensitive) | PCL | <5% | >85% | pH-triggered polymer dissolution |

| PEGDA (Hydrogel, permeable) | PCL | ~45% | ~95% | Diffusion through swollen hydrogel mesh |

| PLA (Semi-crystalline, slow deg.) | PVP | ~20% | ~100% | Diffusion + slow bulk erosion |

Diagrams

Title: Decision Workflow for Material Strategy Selection

Title: Core-Shell Fabrication via Coaxial Extrusion

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Phase Programming

| Item | Function / Relevance |

|---|---|

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) | A biodegradable, semi-crystalline polyester. Serves as the crystalline phase component, providing structural integrity and tunable degradation. |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | A water-soluble, amorphous polymer. Used to create amorphous domains, accelerate dissolution, and stabilize amorphous solid dispersions of drugs. |

| Eudragit L100 | A pH-sensitive, anionic methacrylic acid copolymer (amorphous). Used for enteric coating and targeted release in core-shell designs. |

| Irgacure 2959 | A UV photoinitiator. Enables in-situ photopolymerization of polymer shells during direct ink writing processes. |

| Dimethyl Carbonate (DMC) | A low-toxicity, volatile solvent. Suitable for dissolving PCL and creating inks for DIW with minimal residue. |

| Coaxial Print Head | A specialized nozzle allowing simultaneous, concentric extrusion of two materials. Essential for fabricating core-shell architectures. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Critical for quantifying thermal transitions (Tg, Tm, crystallinity %) to validate phase programming outcomes. |

Application Notes

Within the research thesis on 3D printing multi-material parts with controlled amorphous and crystalline regions, the precise manipulation of process parameters is critical for dictating the crystalline morphology of semi-crystalline polymers (e.g., PCL, PLA, PEEK) and their composites. This control is paramount for applications such as drug-eluting implants, where crystallization impacts mechanical strength, degradation rate, and active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) release kinetics.

- Nozzle Temperature (Tnozzle): Directly governs the melt viscosity and the thermodynamic driving force for nucleation upon deposition. A higher Tnozzle reduces molecular chain entanglements in the melt, potentially allowing for more rearrangement and larger spherulite growth if cooling is slow. Conversely, a lower Tnozzle near the melting point can induce rapid heterogeneous nucleation.

- Cooling Rate (β): The most decisive factor for crystalline fraction and morphology. Rapid quenching (high β) from the melt, often achieved via active bed cooling or forced convection, kinetically traps chains in disordered states, yielding high amorphous content. Slow, controlled cooling (low β) provides the necessary time for chain diffusion, alignment, and crystal growth, increasing crystallinity and often average crystal size.

- Layering (Layer Time and Thickness): Dictates the thermal history gradient through the Z-axis. A new hot layer partially re-melts and anneals the sub-layer, creating an intricate thermal profile. Short layer times (rapid deposition) minimize this effect, while longer times allow for significant isothermal crystallization in previous layers.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Process Parameters on Crystallinity

| Parameter | Low Value Condition | High Value Condition | Typical Measured Crystallinity Range (%) | Key Morphological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nozzle Temp. | Near melting point (Tm) | Significantly above Tm | 15-40% (Low) vs. 25-50% (High)* | Low T: Smaller, imperfect crystallites. High T: Larger spherulites (if cooled slowly). |

| Cooling Rate | Quenched (> 50°C/min) | Slow, controlled (< 5°C/min) | 5-25% (High β) vs. 30-60% (Low β) | High β: Dominantly amorphous. Low β: High crystalline fraction, possible lamellar thickening. |

| Layer Time | Short (< 10 s/layer) | Long (> 60 s/layer) | 20-35% (Short) vs. 30-50% (Long) | Short: Stratified morphology. Long: Gradient crystallinity with annealed lower layers. |

Note: Absolute values are polymer-dependent (e.g., PEEK vs. PLA). The trend indicates the relative change.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Isolating the Effect of Cooling Rate on Crystallinity

Objective: To quantify the relationship between cooling rate and percent crystallinity in a model polymer (e.g., PCL).

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below.

Methodology:

- Specimen Fabrication: Use a single-material FDM printer. Set a standardized nozzle temperature (e.g., 80°C for PCL, 220°C for PLA) and a constant layer thickness (0.2 mm).

- Cooling Modulation: Print identical single-layer or cube specimens under varying cooling conditions:

- Condition A (Quenched): Enable maximum auxiliary cooling fan speed (100%).

- Condition B (Intermediate): Set fan speed to 25%.

- Condition C (Annealed): Disable the part cooling fan and utilize a heated bed set 10°C below the polymer's Tg.

- Thermal Monitoring: Embed a micro-thermocouple at the deposition point to record the actual cooling profile for each condition.

- Analysis: Analyze specimens using Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC). Perform a first heat at 10°C/min to determine the enthalpy of fusion (ΔHf). Calculate percent crystallinity via: %Crystallinity = (ΔHf, sample / ΔHf, 100% crystal) x 100.

Protocol 2: Mapping Z-Axis Crystallinity Gradients Induced by Layering

Objective: To characterize the through-thickness crystallinity gradient in a printed part due to layered thermal history.

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below.

Methodology:

- Printed Part: Fabricate a tall, thin rectangular prism (e.g., 5mm x 5mm x 20mm) using constant print parameters (nozzle temp, speed, fan speed).

- Microtome Sectioning: Using a cryogenic microtome, carefully section the part transversely into sequential ~100μm slices along the Z-axis (build direction). Label each slice with its approximate original height.

- Localized Analysis: Analyze each slice via:

- Micro-Raman Spectroscopy: Focus the laser on the slice center. Measure the ratio of the crystalline-to-amorphous band intensity (e.g., ~920 cm-1 vs. ~870 cm-1 for PCL) to create a relative crystallinity profile.

- Nanoindentation: Perform indentations on the slice surface to map the localized modulus, which correlates with crystallinity.

- Data Correlation: Plot crystallinity or modulus versus Z-height to visualize the gradient.

Visualizations

Title: Parameter-Morphology Control Pathway

Title: Workflow for Controlled Crystallinity Printing

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item/Reagent | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Semi-Crystalline Biopolymer Filament (e.g., PCL, PLA, PEEK) | Base material whose crystalline morphology is to be controlled. Must be of high purity and consistent molecular weight for reproducible thermal behavior. |

| FDM 3D Printer with Modifiable Firmware | Allows precise, independent control of nozzle temperature, bed temperature, and auxiliary cooling fan speed (G-code manipulation). A heated bed is essential. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | The primary tool for quantifying percent crystallinity and thermal transitions (Tg, Tc, Tm). |

| Polarized Optical Microscope (POM) with Hot Stage | Enables direct visualization of spherulite nucleation density, growth, and size as a function of controlled cooling from the melt. |

| Micro-Raman Spectrometer | Provides non-destructive, spatially resolved chemical mapping to identify crystalline/amorphous band ratios within a printed cross-section. |

| Cryogenic Microtome | Used to prepare thin, undamaged cross-sectional slices of printed parts for localized analysis (Raman, nanoindentation). |

| Controlled Atmosphere Enclosure (Dry N2 or Argon) | Prevents thermo-oxidative degradation of polymers during high-temperature printing (critical for PEEK), which can alter crystallization kinetics. |

Introduction This document presents three detailed case studies within the framework of research focused on 3D printing multi-material parts with controlled amorphous and crystalline regions. The precise spatial arrangement of these material phases dictates the functional performance of printed constructs. These applications leverage control over crystallinity for tailored drug release profiles, mechanical anisotropy, and biomimetic architecture.

Case Study: Personalized Craniofacial Implant with Osteoconductive Gradients

Application Note: Patient-specific polyetheretherketone (PEEK) implants for cranial reconstruction are enhanced with a gradient of osteoconductive material (e.g., hydroxyapatite, HA) to promote bone integration. Controlling the crystalline structure of PEEK is critical for its mechanical strength, while the composite regions require management of ceramic particle distribution and polymer crystallinity at the interface.

Key Data & Outcomes: Table 1: Properties of Graded PEEK/HA Implant vs. Pure PEEK

| Property | Pure PEEK (Crystalline Region) | PEEK/HA Composite (Interface Region) | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elastic Modulus | 3.6 - 4.0 GPa | 5.8 - 7.2 GPa (graded) | Nanoindentation |

| Bone Apposition Rate | Low | Increased by ~300% at peak HA concentration | Histomorphometry (8 weeks in vivo) |

| Crystallinity (Xc) | 30-35% | Reduced to 20-25% at interface | Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) |

Experimental Protocol: Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF) of Graded Implant

- Pre-processing: Convert patient CT data to a 3D model. Design a material gradient map, specifying 100% PEEK filament for the bulk implant and a gradient to a 70/30 PEEK/HA composite filament at the bone-facing surface.

- Printing Setup: Employ a dual-nozzle FFF printer. Nozzle 1 loads pure PEEK filament. Nozzle 2 loads composite PEEK/HA filament. Chamber temperature is maintained at 120°C to minimize thermal stress and control crystallization kinetics.

- Gradient Fabrication: Program toolpath to initiate co-printing at the defined interface. The extrusion ratio from the two nozzles is dynamically varied per the gradient map over a 2mm transition zone.

- Post-processing: Anneal the printed implant at 200°C (above PEEK's glass transition, Tg ~143°C) for 2 hours in an inert atmosphere to relieve internal stresses and achieve a stable, controlled crystalline structure.

Scientist's Toolkit:

- Medical-Grade PEEK Filament: High-purity, biocompatible polymer feedstock with consistent crystallinity.

- PEEK/HA Composite Filament: Filament with uniformly dispersed nano-hydroxyapatite particles (20-30% wt.) to induce osteoconductivity.

- Controlled Atmosphere Print Chamber: Prevents polymer oxidation at high processing temperatures.

- Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC): For quantifying the degree of crystallinity in different regions of the printed part.

Diagram: Workflow for Personalized Graded Implant

Case Study: Multi-Drug Polypill with Timed Release Profiles

Application Note: A single tablet (polypill) is printed containing three drugs with distinct release kinetics: immediate, delayed, and sustained. This is achieved by employing excipients with different crystalline/amorphous ratios and multi-material print cores. Amorphous solid dispersions are used to enhance solubility for poorly water-soluble drugs.

Key Data & Outcomes: Table 2: Release Profile of a 3-Agent Polypill

| Drug Layer | Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) | Excipient System (Crystallinity Role) | Target Release (T50%) | Achieved T50% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate | Aspirin | Crystalline Mannitol (Rapid dissolution) | < 15 min | 12 ± 3 min |

| Delayed (Enteric) | Pantoprazole | Amorphous HPMCAS (pH-triggered dissolution) | ~2 hours (in SI) | 2.1 ± 0.4 hours |

| Sustained | Atorvastatin | Amorphous Solid Dispersion in PVP (controlled erosion) | 8-10 hours | 9.2 ± 1.1 hours |

Experimental Protocol: Powder Bed Binder Jetting for Polypills

- Powder Preparation: Use a crystalline mannitol-based powder blend for the immediate layer. Use an amorphous cellulose-based powder for the sustained layer.

- Binder Formulation: Prepare aqueous binder solutions containing respective drugs: aspirin for immediate, atorvastatin-PVP for sustained. For the delayed layer, pantoprazole is suspended in a non-aqueous, pH-sensitive polymer solution.

- Layer-by-Layer Printing: Spread the immediate-release powder layer. Jet the aspirin binder selectively. Spread the sustained-release powder layer. Jet the atorvastatin-PVP binder. Repeat for desired core. Finally, encapsulate the core with several layers of enteric powder jetted with the pantoprazole binder.

- Curing & Post-processing: Dry the printed tablet array at 40°C for 4 hours. Gently depowder. No further sintering is applied to maintain the amorphous nature of the solid dispersions.

Scientist's Toolkit:

- Engineered Excipient Powders: Tailored for binder jetting with controlled particle size, shape, and crystallinity (e.g., spherical mannitol, amorphous lactose).

- Polymeric Binders (PVP, HPMCAS): Form amorphous solid dispersions to stabilize APIs and modulate release.

- pH-Sensitive Polymers (Eudragit L100): For delayed, enteric release layers.

- USP Dissolution Apparatus II (Paddle): For in vitro drug release testing in media of varying pH.

Diagram: Polypill Multi-Material Print Logic

Case Study: Osteochondral Tissue Scaffold with Zonal Porosity

Application Note: A biphasic scaffold mimics the osteochondral interface: a cartilaginous region (soft, porous) and a subchondral bone region (stiff, mineralized). This is achieved by printing a multi-material hydrogel with spatial control over polymer crosslinking density (affecting amorphous network structure) and ceramic particle incorporation.

Key Data & Outcomes: Table 3: Zonal Properties of 3D Printed Osteochondral Scaffold

| Scaffold Zone | Material Composition | Avg. Pore Size | Compressive Modulus | Primary Cell Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cartilage Region | Methacrylated Gelatin (GelMA) | 180 ± 20 µm | 12 ± 2 kPa | Chondrocytes |

| Interface Region | GelMA + nano-HA (10% w/v) | Gradient 180 → 100 µm | Gradient 12 → 150 kPa | Mesenchymal Stem Cells |

| Bone Region | GelMA + nano-HA (30% w/v) | 100 ± 15 µm | 280 ± 35 kPa | Osteoblasts |

Experimental Protocol: Digital Light Processing (DLP) of Graded Hydrogels

- Bioink Preparation: Synthesize GelMA. Prepare three resin vats: (A) Pure GelMA photoinitiator solution; (B) GelMA with 10% nano-HA; (C) GelMA with 30% nano-HA. Maintain homogeneity of HA in (B) and (C).

- Graded Printing via Vat Switching: Design the 3D model with clear zone demarcation. The DLP printer platform is lowered into Vat A, and the cartilage layer is exposed to patterned blue light (405 nm). The platform is raised, rinsed briefly, then lowered into Vat B for the interface layer. The process repeats for Vat C for the bone layer.

- Post-Printing Processing: Crosslink the entire construct under broad-spectrum UV light for 60 sec for final cure. Wash in sterile PBS to remove unreacted monomers. Characterize porosity via micro-CT and modulus via compression testing.

- Cell Seeding: Seed chondrocytes preferentially onto the cartilage zone and osteoblasts onto the bone zone using a pipette-based method, exploiting the scaffold's wetting properties.

Scientist's Toolkit:

- Methacrylated Gelatin (GelMA): Photocrosslinkable hydrogel mimicking extracellular matrix.

- Nano-Hydroxyapatite (nano-HA): Ceramic particles for osteoconduction and mechanical reinforcement.

- Photoinitiator (LAP): Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate, biocompatible for cell-laden printing.

- Digital Light Processing (DLP) Printer: For high-resolution, layer-based vat photopolymerization with multi-vat capability.

Diagram: DLP Process for Biphasic Scaffold

Solving Print Challenges: Adhesion, Stability, and Reproducibility in Multi-Phase Structures

Interface engineering is critical for fabricating reliable multi-material parts via 3D printing, particularly when integrating dissimilar amorphous and crystalline polymer regions. This is paramount in pharmaceutical and biomedical devices, where controlled drug release profiles depend on the precise spatial distribution and bonding integrity of these regions. Poor interfacial adhesion leads to delamination, stress concentration, and device failure. The core challenge lies in overcoming the thermodynamic immiscibility and kinetic barriers between ordered (crystalline) and disordered (amorphous) phases. Strategies involve molecular design, in-process energy modulation, and post-processing to create robust interphase regions with graded or interlocked morphology.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Interface Engineering |

|---|---|

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) | A semi-crystalline polymer used as the crystalline model phase; provides structural integrity and tunable degradation. |

| Poly(D,L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | An amorphous copolymer used as the amorphous model phase; enables controlled drug release. |

| Pluronic F-127 | A triblock copolymer surfactant; acts as a compatibilizer to reduce interfacial tension and improve adhesion. |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) Nanosheets | 2D nanofiller; when functionalized, migrates to the interface during printing, providing mechanical interlocking and stress transfer. |

| Benzophenone-based Photo-linker | A UV-active crosslinker; enables covalent bonding across the interface via selective irradiation during printing. |

| Silane Coupling Agent (e.g., (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane) | Forms covalent bridges between polymer chains and inorganic fillers or adjacent polymer phases. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: In-Nozzle Mixing for Interphase Gradation

Objective: To create a functionally graded interphase between amorphous PLGA and crystalline PCL during Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM). Materials: PLGA (85:15), PCL (Mn 80,000), Dichloromethane (DCM), Dual-channel syringe pump, Custom coaxial nozzle. Procedure:

- Prepare Solutions: Dissolve PLGA in DCM (25% w/v) and PCL in DCM (30% w/v) separately. Stir for 12 hours.

- Load Syringes: Load each polymer solution into separate syringes on a dual-channel pump.

- Configure Nozzle: Attach a custom coaxial nozzle. PLGA is fed through the outer annulus, PCL through the inner core.

- Print with Gradient: Initiate printing. Program the syringe pump to linearly decrease PCL flow rate from 100% to 0% while simultaneously increasing PLGA flow rate from 0% to 100% over a 500 µm translation distance.

- Solvent Evaporation: Utilize in-situ heating (60°C) and vacuum assist at the nozzle tip to rapidly evaporate DCM, solidifying the graded filament.

- Characterize: Use micro-Raman mapping across the interface to confirm gradient composition.

Protocol 3.2: UV-Intervallic Crosslinking During Vat Photopolymerization

Objective: To covalently bond an amorphous methacrylate-based resin to a crystalline acrylate-based resin layer-by-layer. Materials: Amorphous resin: Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA, Mn 700) with 2% Irgacure 819. Crystalline resin: Poly(ε-caprolactone) diacrylate (PCL-DA, Mn 10,000) with 2% Irgacure 819 and 0.5% benzophenone. Procedure:

- Print First Layer: Deposit and spread amorphous resin (PEGDA). Expose with 405 nm UV (5 mW/cm² for 10 s) to solidify.

- Interface Treatment: Do not recoate. Instead, flood the solidified layer with a mist of benzophenone solution in ethanol (1% w/v) and gently dry.

- Print Second Layer: Deposit and spread the crystalline resin (PCL-DA) directly onto the treated layer.

- Interface Crosslinking: Expose the entire new layer to a lower-intensity UV (2 mW/cm² for 30 s). The benzophenone initiates radical formation on the first layer, grafting PCL-DA chains to the PEGDA network.

- Full Layer Cure: Complete curing of the second layer with standard exposure (5 mW/cm² for 15 s).

- Repeat: Continue steps 2-5 for subsequent layers.

- Characterize: Perform lap-shear tests per ASTM D3163 on bilayer samples.

Protocol 3.3: Interfacial Crystallization Seeding

Objective: To induce epitaxial-like crystal growth from the crystalline region into the amorphous region, creating a physical interlock. Materials: PCL (crystalline matrix), Amorphous Poly(L-lactic acid) (PLLA) drug-loaded film, Controlled hot stage. Procedure:

- Prepare Substrate: Melt-press PCL into a thin film (200 µm) and isothermally crystallize at 45°C for 2 hours.

- Deposit Amorphous Layer: Dissolve amorphous PLLA and drug (e.g., Ibuprofen) in chloroform. Cast solution directly onto the crystalline PCL film.

- Controlled Annealing: Place the bilayer in a controlled hot stage. Heat to 80°C (above PLLA Tg but below PCL Tm) for 5 minutes to allow chain relaxation at the interface.

- Seeded Crystallization: Cool rapidly to 100°C (above PCL Tm) and hold for 1 minute. Then, cool slowly to 120°C at 0.5°C/min. At this temperature, PCL chains at the interface act as nuclei for PLLA crystallization.

- Final Quench: Cool to room temperature.

- Characterize: Use Polarized Optical Microscopy (POM) and Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) to visualize trans-interfacial crystal growth.

Table 1: Interfacial Shear Strength of Engineered Bonds

| Engineering Method | Amorphous Material | Crystalline Material | Avg. Interfacial Shear Strength (MPa) | Std. Dev. (MPa) | Reference Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Grading (Coaxial) | PLGA | PCL | 4.2 | ±0.3 | 2023 |

| UV Crosslinking (Benzophenone) | PEGDA | PCL-DA | 8.7 | ±0.6 | 2024 |

| Crystallization Seeding | a-PLLA | PCL | 6.1 | ±0.5 | 2023 |

| Untreated Adhesion | PLGA | PCL | 0.9 | ±0.2 | - |

Table 2: Effect of Compatibilizer (Pluronic F-127) on Interphase Width

| Compatibilizer Conc. (% w/w) | Interphase Width (µm) via SEM-EDS | Drug Release Lag Time (hr) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5.1 | 2.1 |

| 1 | 18.7 | 5.8 |

| 3 | 35.2 | 12.4 |

| 5 | 32.9 | 11.9 |

Visualized Workflows & Pathways

Title: Multi-Material Interface Engineering Workflow

Title: Bonding Mechanisms and Engineering Routes

Within the broader thesis on 3D printing multi-material parts with controlled amorphous and crystalline regions, managing the thermal history of printed materials is paramount. This is especially critical in pharmaceutical and advanced polymer applications, where unwanted crystallization can compromise product performance, stability, and drug release profiles. These Application Notes detail protocols for characterizing and controlling thermal history during extrusion-based 3D printing (e.g., Fused Deposition Modeling, FDM) and subsequent storage to prevent undesirable phase transitions.

Table 1: Common 3D Printing Polymers and Their Crystallization Characteristics

| Polymer / Formulation | Glass Transition Temp (Tg) °C | Melting Temp (Tm) °C | Crystallization Half-Time (t½) at 25°C | Critical Cooling Rate to Avoid Crystallization °C/min |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCL (Polycaprolactone) | -60 | 60 | Minutes to Hours | ~10 |

| PVA (Polyvinyl Alcohol) | 85 | 230 | Days (Dry) | ~50 |

| PLGA (50:50) | 45-50 | Amorphous | N/A | N/A |

| PEO (Polyethylene Oxide) | -67 | 65 | Hours | ~15 |

| Amorphous ITZ (Itraconazole) | ~60 | N/A | Weeks (Below Tg) | N/A |

| Hot-Melt Extrusion (HME) Filament (Model API in Polymer) | Varies (40-80) | Varies | Hours to Months | >20 (Typical) |

Table 2: Impact of Print Parameters on Thermal History

| Parameter | Typical Range Studied | Effect on Nozzle Exit Temp | Effect on Part Cooling Rate | Risk of Unwanted Crystallization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nozzle Temperature | 150°C - 220°C | Direct Increase | Slight Increase | High: Increases supercooling if too high. |

| Bed Temperature | 25°C - 80°C | No Effect | Significant Decrease | High: Slows cooling, promotes crystallization. |

| Print Speed | 10 - 100 mm/s | Slight Decrease | Increase | Low: Faster cooling reduces risk. |

| Layer Height | 0.1 - 0.3 mm | No Effect | Increase (Thinner layers cool faster) | Medium: Thicker layers retain heat longer. |

| Enclosure Temperature | 25°C - 60°C | No Effect | Major Decrease | Very High: Dramatically reduces cooling rate. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Characterizing Thermal History During Printing

Objective: To map the temperature profile of a printed strand from nozzle extrusion to solidification. Materials: Infrared (IR) thermal camera, FDM 3D printer, printing filament (e.g., API-loaded polymer), data acquisition software. Methodology:

- Calibrate the IR thermal camera according to manufacturer instructions, ensuring correct emissivity is set for the material.

- Mount the camera to focus on the print nozzle tip and the initial build plate layers.

- Program a simple single-line print (e.g., 50mm length) at standard parameters.

- Initiate print and simultaneously record IR video at ≥10 fps.

- Use analysis software to extract temperature vs. time data for specific points along the extrudate path.

- Plot temperature profiles and calculate cooling rates (dT/dt) in the critical temperature window between Tm and Tg.

Protocol 3.2: Accelerated Stability Study for Post-Print Crystallization

Objective: To predict long-term physical stability of printed amorphous solid dispersions. Materials: Printed specimens, desiccator, humidity chambers, oven, XRD or DSC. Methodology:

- Store printed samples under controlled conditions: (a) Dry (over desiccant), (b) 25°C/60% RH, (c) 40°C/75% RH.

- At predetermined time points (e.g., 1, 2, 4, 8 weeks), remove triplicate samples.

- Analyze samples using Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) to detect crystallization exotherms/melting endotherms or X-ray Powder Diffraction (XRPD) to detect crystalline peaks.

- Quantify the degree of crystallinity using standard methods (e.g., enthalpy of fusion relative to 100% crystalline standard).

- Fit crystallinity vs. time data to models (e.g., Avrami equation) to extract crystallization kinetics.

Protocol 3.3: In-Process Quenching to Maintain Amorphous Content

Objective: To implement active cooling to bypass crystallization during printing. Materials: FDM printer modified with directed air cooling (e.g., auxiliary fan), thermocouple, adjustable cooling rig. Methodology:

- Install a high-efficiency, directional cooling fan focused on the extrudate immediately after the nozzle.

- Connect a thermocouple ~2mm below the nozzle to monitor effective strand temperature.

- Print a calibration cube with varying fan speeds (0% to 100%).

- Measure the achieved cooling rate using IR thermography (Protocol 3.1).

- Print a critical part (e.g., a thin-walled capsule) with the optimized fan speed.

- Validate amorphous state of the final part using DSC or XRD immediately after printing.

Visualization Diagrams

Diagram 1: Post-Print Crystallization Risk Pathway

Diagram 2: Thermal History Management Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Thermal History Management Research

| Item | Function & Relevance |

|---|---|

| Hot-Melt Extrusion (HME) System | For producing homogeneous, amorphous solid dispersion filaments from API and polymeric carriers, the primary feedstock for FDM printing. |

| Modular FDM 3D Printer | A research-grade printer allowing precise control and modification of print parameters (nozzle/bed temp, speed) and hardware (cooling fans). |

| High-Speed IR Thermal Camera | Critical for non-contact, real-time mapping of temperature profiles and cooling rates of the extrudate during printing. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | For characterizing thermal properties (Tg, Tm, Tc, enthalpy) of raw materials, filaments, and printed parts to quantify amorphous/crystalline content. |

| X-ray Powder Diffractometer (XRPD) | The gold standard for identifying and quantifying crystalline phases within printed matrices, especially for low-degree crystallization. |

| Stability Chambers (ICH Conditions) | For conducting controlled accelerated stability studies (temperature/humidity) on printed parts to model shelf-life and post-print crystallization. |

| Pharmaceutical-Grade Polymers (e.g., PVPVA, HPMCAS, Soluplus) | Amorphous polymers that inhibit crystallization and are suitable for forming solid dispersions with active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). |

| Model APIs (e.g., Itraconazole, Fenofibrate, Griseofulvin) | Poorly water-soluble drugs commonly used in amorphous solid dispersion research to demonstrate proof-of-concept for printed dosage forms. |

| Dynamic Vapor Sorption (DVS) Instrument | To measure moisture uptake of printed materials, which plasticizes the polymer and can drastically accelerate unwanted crystallization. |

1.0 Context & Significance Within research focusing on 3D printing multi-material drug delivery systems with controlled amorphous solid dispersions (ASD) and crystalline regions, print fidelity is not merely a mechanical concern but a critical determinant of pharmaceutical performance. Warping, delamination, and nozzle clogging directly compromise the structural integrity and precise spatial distribution of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and polymers. This document outlines applied protocols to mitigate these failures, ensuring the reproducibility of complex, functionally graded prints for in vitro and in vivo studies.

2.0 Quantitative Analysis of Failure Modes & Mitigation Parameters

Table 1: Primary Failure Modes, Root Causes, and Mitigation Parameters

| Failure Mode | Primary Root Cause | Key Material Parameter | Key Hardware/Process Parameter | Target Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warping | Differential thermal contraction & residual stress. | Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE), Glass Transition Temp (Tg). | Bed Temperature (T_bed), Chamber Temp, Print Speed. | Minimize thermal gradient (ΔT). |

| Delamination | Weak interlayer adhesion & poor weld strength. | Polymer Entanglement Density, Surface Energy. | Nozzle Temperature (T_nozzle), Layer Height, Flow Rate. | Maximize interdiffusion at interface. |

| Nozzle Clogging | Thermal degradation; crystallization in melt; particulate contamination. | Thermal Degradation Temp (T_d), Crystallization Kinetics, Particle Size (API/Filler). | Nozzle Temp, Nozzle Diameter (D_n), Filament Filtration. | Maintain homogeneous melt viscosity. |

Table 2: Optimized Protocol Windows for Common Pharmaceutical Polymers (Representative Data)

| Polymer/Blend | T_bed (°C) | T_nozzle (°C) | Chamber/Env. | Max. Layer Height (mm) | Critical Speed (mm/s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVA (Support) | 60-70 | 185-200 | Dry (<20% RH) | 0.2 | 40 | Hydroscopic; requires dry storage. |

| PLA (Structural) | 60 | 200-220 | Ambient | 0.3 | 80 | Low warp, stable. |

| PVP-VA64 (ASD) | 90-100 | 215-230 | Dry (<10% RH), 40°C | 0.15 | 30 | Prone to clogging; needs active drying. |

| EC (Crystalline) | 70-80 | 230-250 | Ambient | 0.25 | 50 | High melt viscosity; larger nozzle recommended. |

| PCL (Elastic) | 25-40 | 70-100 | Cooled Bed | 0.3 | 50 | Low Tg; requires bed cooling for crystallization control. |

3.0 Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Baseline Adhesion & Warping Assessment (Tape Test & Dimensional Analysis) Objective: Quantify bed adhesion and warping propensity of a new material under controlled conditions. Materials: Leveled print bed (glass or PEI), target filament (pre-dried), IPA for cleaning, digital caliper (±0.01mm), flat-edge ruler. Procedure:

- Bed Preparation: Clean bed with IPA. Apply uniform layer of recommended adhesive (e.g., diluted PVA glue for polymers, hairspray for PLA).

- Print Model: Print a standard 100x100x2 mm single-layer square. Use manufacturer-recommended T_nozzle initial.

- Adhesion Score (Tape Test): After cooling, attempt to lift corner with tweezers. Score: 5 (cannot remove), 4 (removes with significant force), 3 (removes with moderate force), 2 (removes easily), 1 (detaches during print).

- Warp Quantification: After complete cool-down to 25°C, place ruler across diagonal. Use caliper to measure maximum gap between bed and print edge. Record as "warp height."

- Iteration: Adjust Tbed in 5°C increments and repeat. Optimal Tbed is lowest temperature yielding adhesion score ≥4 and warp height <0.5 mm.

Protocol 3.2: Interlayer Adhesion (Delamination) Tensile Test per ASTM D638-14 Objective: Measure the interlayer weld strength of printed specimens. Materials: Dual-extrusion printer, primary and support material, universal testing machine (UTM), dessicator. Procedure:

- Specimen Printing: Print Type IV or V tensile dogbones per ASTM D638-14 with raster angle at 0°/90° and with print orientation such that tensile stress is applied perpendicular to layer lines (Z-direction).

- Conditioning: Store specimens in a dessicator at 25°C for 48 hours to normalize moisture.

- Testing: Mount specimen in UTM grips. Apply tensile load at a rate of 5 mm/min until failure.