Polymeric Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery: Advances, Applications, and Future Prospects

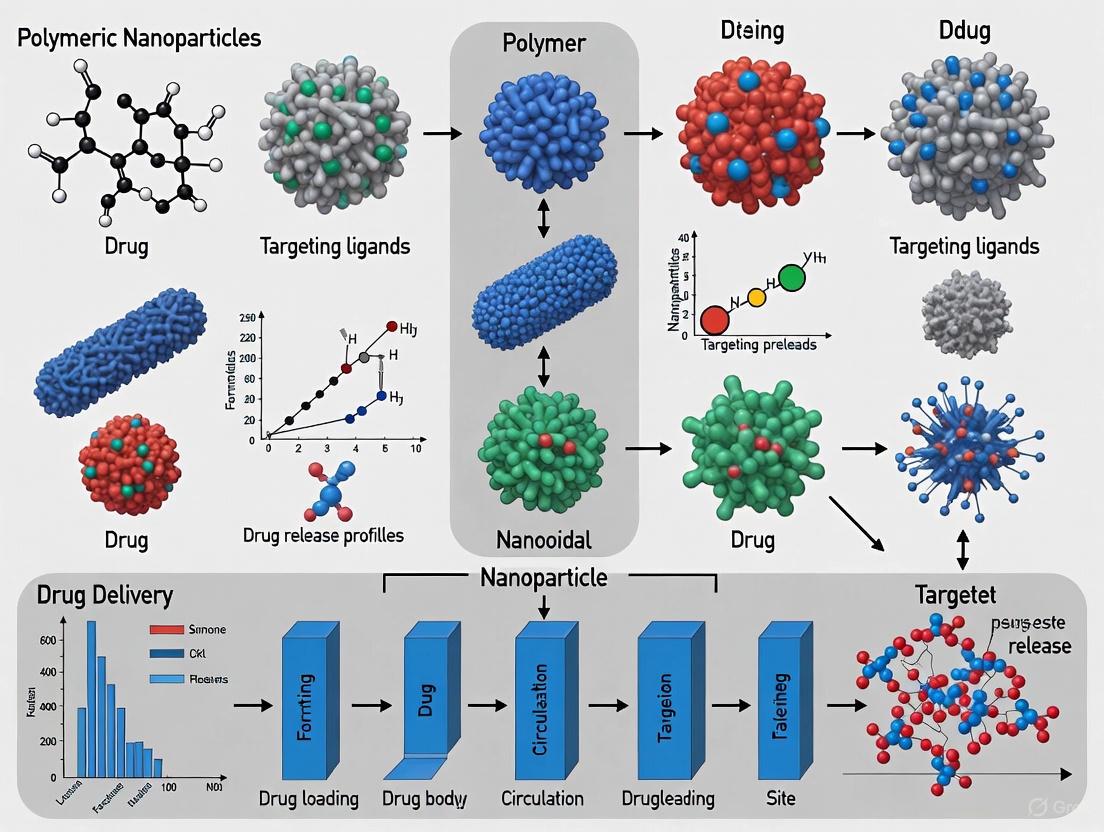

This comprehensive review explores the rapidly evolving field of polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) as sophisticated drug delivery systems.

Polymeric Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery: Advances, Applications, and Future Prospects

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the rapidly evolving field of polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) as sophisticated drug delivery systems. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the article delves into the foundational principles of PNP design, including polymer selection and the biological barriers they must overcome. It provides a detailed analysis of current fabrication methodologies, characterization techniques, and their diverse therapeutic applications in areas such as cancer therapy, ocular delivery, and infectious diseases. The content further addresses critical challenges in clinical translation—including scalability, biocompatibility, and immune evasion—and offers optimization strategies. Finally, it evaluates the clinical and commercial landscape, comparing PNPs with other nanocarriers and discussing the promising integration of stimuli-responsive systems and AI-driven design for the future of precision medicine.

The Foundation of Polymeric Nanoparticles: Design Principles and Biological Interactions

Polymeric nanoparticles represent a cornerstone of modern drug delivery system research, offering unparalleled versatility in encapsulating and delivering therapeutic agents. These colloidal carrier systems, with diameters typically less than 1 μm, are primarily categorized as either nanospheres or nanocapsules based on their fundamental architectural differences [1]. Understanding this distinction is critical for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to design optimized nanocarriers for specific biomedical applications.

Nanospheres exhibit a matrix-type structure where the drug is uniformly dispersed, dissolved, or adsorbed throughout a continuous polymeric network [1]. In this configuration, the active substance is distributed within the entire volume of the solid particle, creating a monolithic system where release kinetics are governed by diffusion through the polymer matrix or polymer erosion. In contrast, nanocapsules possess a vesicular structure characterized by a core-shell morphology [1]. These systems feature an oil-based or aqueous core that encapsulates the active substance, surrounded by a protective polymeric shell that acts as a barrier membrane, controlling the release rate of the encapsulated compound. This fundamental architectural difference directly influences their drug loading capacity, release profiles, and suitability for particular therapeutic applications in drug delivery research.

Comparative Analysis: Structural and Functional Characteristics

The structural divergence between nanospheres and nanocapsules directly translates to distinct functional properties that dictate their performance in drug delivery applications. The table below summarizes the key characteristics that researchers must consider during the design phase.

Table 1: Comparative characteristics of nanospheres versus nanocapsules

| Characteristic | Nanospheres | Nanocapsules |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Structure | Matrix-based, monolithic system | Reservoir-based, vesicular system |

| Drug Location | Dispersed, dissolved, or adsorbed throughout polymer matrix | Confined within an inner cavity (oil or aqueous core) surrounded by polymeric shell [1] |

| Polymer Distribution | Uniform throughout particle | Concentrated in the shell membrane [1] |

| Typical Drug Load | Generally high for lipophilic drugs | High for lipophilic drugs (if oil core) or hydrophilic drugs (if aqueous core) |

| Release Profile | Diffusion-controlled through polymer matrix; often biphasic (initial burst followed by sustained release) | Membrane-controlled; can provide more constant, zero-order release kinetics |

| Primary Advantages | Protection of labile drugs, sustained release, high stability | High encapsulation efficiency for compatible drugs, controlled release, protection of core content |

Beyond these fundamental characteristics, the surface properties of both nanosphere and nanocapsule systems can be modified through the attachment of targeting ligands (e.g., folic acid, peptides, antibodies) to enhance site-specific accumulation [2] [3]. The polymer composition itself can be engineered to create "smart" nanoparticles that respond to specific stimuli in the tumor microenvironment (e.g., pH, redox potential, or specific enzymes), enabling precise drug release at the targeted site [3].

Preparation Methodologies: Standard Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Nanosphere Preparation via Emulsion-Solvent Evaporation

The emulsion-solvent evaporation method represents a widely utilized technique for nanosphere production, particularly suitable for encapsulating lipophilic drugs [2].

- Oil Phase Preparation: Dissolve 100-500 mg of biodegradable polymer (e.g., PLGA, PLA) and 10-50 mg of lipophilic active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) in 10-20 mL of a water-immiscible organic solvent (typically dichloromethane or ethyl acetate).

- Aqueous Phase Preparation: Prepare 50-100 mL of an aqueous surfactant solution (e.g., 0.5% - 2% w/v polyvinyl alcohol or sodium cholate) in purified water.

- Primary Emulsion Formation: Add the organic phase to the aqueous phase under high-speed homogenization (e.g., 10,000-15,000 rpm for 2-5 minutes) using a high-shear homogenizer to form an oil-in-water (O/W) emulsion.

- Solvent Evaporation: Transfer the formed emulsion to a magnetic stirrer and stir continuously at 400-600 rpm for 3-6 hours at room temperature to allow for complete evaporation of the organic solvent. This step causes the polymer to precipitate, forming solid nanospheres with the API encapsulated within the matrix.

- Purification: Centrifuge the resulting nanosphere suspension at 15,000-20,000 x g for 30-60 minutes. Discard the supernatant and re-suspend the pellet in purified water or an isotonic buffer (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline, PBS). Repeat this washing step 2-3 times to remove residual surfactant and unencapsulated API.

- Final Product Formation: Re-suspend the purified nanosphere pellet in an appropriate medium (e.g., PBS, sucrose solution for cryoprotection) and lyophilize for long-term storage, if required.

Protocol for Nanocapsule Preparation via Nanoprecipitation

The nanoprecipitation method, also known as solvent displacement, is a common and efficient technique for preparing nanocapsules with an oil core [3].

- Organic Phase Preparation: Dissolve 50-200 mg of polymer (e.g., PCL, PLA, PEG-PLA) and 5-25 mg of a lipophilic drug in a water-miscible organic solvent (e.g., acetone, ethanol). Add 0.5-2 mL of a specific oil (e.g., Miglyol 812, caprylic/capric triglycerides, or almond oil) to this solution.

- Aqueous Phase Preparation: Prepare 100-200 mL of an aqueous solution containing a stabilizer (e.g., 0.5% w/v polysorbate 20 or 80) in purified water.

- Nanoprecipitation: Inject the organic phase into the aqueous phase under moderate magnetic stirring (300-600 rpm) using a syringe pump (flow rate of 1-5 mL/min) or by drop-wise addition. The rapid diffusion of the organic solvent into the water causes the instantaneous formation of nanocapsules with an oil core surrounded by a polymeric wall.

- Organic Solvent Removal: Place the suspension under reduced pressure (e.g., using a rotary evaporator) or continue stirring for 1-2 hours at room temperature to completely remove the organic solvent.

- Purification and Concentration: Purify the nanocapsule suspension using tangential flow filtration (TFF) with appropriate molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) membranes (typically 100-300 kDa) or by centrifugation. TFF is preferred for scalable processes and to avoid capsule disruption [4].

- Final Product Formation: Adjust the concentration of the purified nanocapsules to the desired volume and lyophilize with a suitable cryoprotectant (e.g., trehalose, mannitol) for storage.

Characterization Techniques: Essential Analytical Protocols

Rigorous characterization is imperative to ensure the quality, reproducibility, and efficacy of polymeric nanoparticles. The table below outlines the critical parameters and standard analytical methods employed.

Table 2: Essential characterization techniques for polymeric nanoparticles

| Parameter | Analytical Technique | Protocol Summary & Significance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Size & Distribution (PDI) | Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Dilute nanoparticle suspension in filtered buffer and measure at 25°C. PDI < 0.2 indicates a monodisperse population, crucial for reproducible biodistribution [2] [3]. | ||||

| Surface Charge | Zeta Potential Analysis | Measure electrophoretic mobility in a diluted suspension at neutral pH. A value > | +30 | mV or < | -30 | mV typically indicates good electrostatic stability [3]. |

| Encapsulation Efficiency (EE) | Indirect Method: UV-Vis Spectroscopy | Separate unencapsulated drug (via ultrafiltration/ultracentrifugation). Analyze the free drug in the supernatant. EE(%) = (Total Drug - Free Drug) / Total Drug × 100% [2]. High EE reduces cost and waste. | ||||

| Morphology | Electron Microscopy (TEM/SEM) | Deposit a diluted sample on a carbon-coated grid, stain (e.g., uranyl acetate for TEM), and image. Confirms core-shell (nanocapsules) vs. matrix (nanospheres) structure [1]. | ||||

| In Vitro Drug Release | Dialysis Bag / Franz Cell | Place nanoparticle suspension in a dialysis membrane (appropriate MWCO). Immerse in release medium (PBS, pH 7.4) at 37°C under sink conditions. Withdraw samples at predetermined times and analyze drug content via HPLC/UV-Vis to generate a release profile [1] [2]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful formulation of polymeric nanoparticles requires a selection of critical reagents and materials. The following toolkit details essential components and their functions in the preparation process.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for nanoparticle fabrication

| Reagent/Material | Function/Role | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Biodegradable Polymers | Forms the structural matrix (nanospheres) or protective shell (nanocapsules); determines degradation rate and drug release kinetics. | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL), Chitosan, Poly(lactic acid) (PLA) [2] [3]. |

| Surfactants/Stabilizers | Prevents nanoparticle aggregation during and after formation by providing steric or electrostatic stabilization. | Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA), Polysorbates (Tween), Lipoids (e.g., Lipoid S PC-3), Phospholipids [2] [5]. |

| Oils (for Nanocapsules) | Forms the internal core of nanocapsules, serving as a reservoir for dissolving and encapsulating lipophilic drugs. | Miglyol 812, Caprylic/Capric Triglycerides, Almond Oil, Ethyl Oleate [1]. |

| Organic Solvents | Dissolves polymers and lipophilic compounds for the formulation process. Must be removed to final product. | Dichloromethane (DCM), Ethyl Acetate, Acetone, Ethanol [5]. |

| Targeting Ligands | Surface-functionalization molecules that enhance specific accumulation at the target site (e.g., tumor). | Folic Acid, Peptides, Antibodies, PEG (stealth coating) [2] [3]. |

Advanced Manufacturing: Scaling Up Production

Transitioning from small-scale laboratory synthesis to industrial production presents significant challenges, including maintaining batch-to-batch reproducibility, homogeneity, and control over nanoparticle properties [5]. Conventional small-scale methods are often time-intensive and difficult to scale. A promising advancement is the use of microfluidic mixing devices for the continuous production of layer-by-layer nanoparticles [4]. This approach allows polymers and other layers to be sequentially added as particles flow through a microchannel, eliminating the need for purification after each step and integrating Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP)-compliant processes. This method has demonstrated the capability to produce 15 mg of nanoparticles (approximately 50 doses) in just a few minutes, a significant improvement over traditional batch processes, thus facilitating the path to clinical trials [4].

Polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) represent a groundbreaking advancement in targeted drug delivery systems, offering significant benefits over conventional systems, including versatility, biocompatibility, and the ability to encapsulate diverse therapeutic agents for controlled release [6]. The selection of polymer building blocks—natural, synthetic, or a hybrid of both—is fundamental to the performance of these nanocarriers. These polymers determine the nanoparticles' critical physicochemical properties, such as size, shape, surface charge, and drug-loading capacity, which in turn influence their behavior in biological environments, targeting capabilities, and overall therapeutic efficacy [7] [6]. Framed within the context of a broader thesis on polymeric nanoparticles for drug delivery, these application notes and protocols provide a comparative overview of core polymer materials and detailed methodologies for their use in formulating advanced drug delivery systems for researchers and drug development professionals.

Comparative Analysis: Natural vs. Synthetic Polymers

The choice between natural and synthetic polymers is pivotal and depends on the specific requirements of the drug delivery application. The table below summarizes their key characteristics and applications.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Natural and Synthetic Polymers for Drug Delivery

| Feature | Natural Polymers | Synthetic Polymers |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Extracted from microorganisms, algae, plants, or animals (e.g., crustaceans) [7]. | Artificially produced in laboratories from petroleum-derived monomers [7]. |

| Common Examples | Alginate, hyaluronic acid, chitosan, collagen, gelatin, starch [7]. | Poly(lactic acid) (PLA), Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), Poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA), Polyethylene glycol (PEG) [7] [6]. |

| Backbone Composition | Carbon, oxygen, nitrogen [7]. | Predominantly carbon-carbon bonds [7]. |

| Biocompatibility & Toxicity | Generally high biocompatibility; similar to ECM components, avoiding chronic immunological reactions [7]. | Variable; many are biocompatible and biodegradable, but some can elicit toxicity or immune responses [7] [8]. |

| Biodegradability | Usually biodegradable and metabolized in the biological environment [7]. | Some are biodegradable (e.g., PLA, PLGA); others are not [7]. |

| Key Advantages | Biocompatible, biodegradable, low carbon footprint, often biologically active (e.g., inherent antibacterial properties of chitosan) [7]. | Properties can be precisely engineered (e.g., molecular weight, degradation rate); high batch-to-batch consistency; versatile chemistry for functionalization [7] [8]. |

| Key Limitations | Batch-to-batch variability; strong intra/intermolecular bonds can limit processability; potential immunogenicity [7] [8]. | Risk of toxicity or biopersistence from non-degradable polymers or degradation by-products; complex manufacturing scaling [8]. |

| Primary Drug Delivery Applications | Drug delivery carriers, tissue engineering scaffolds, wound healing, hydrogel preparation [7]. | Controlled drug release systems, nano-carriers, stimuli-responsive "smart" systems, gene delivery, bio-inks for 3D-printing [7] [6]. |

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Formulation of Stimuli-Responsive Hybrid Nanoparticles

This protocol details the synthesis of near-infrared (NIR) light-responsive hybrid particles for controlled drug and growth factor release, adapted from recent research [7].

3.1.1. Principle Hybrid particles composed of natural proteins (gelatin, agarose) and black phosphorus quantum dots (BPQDs) are engineered to release encapsulated cargo (e.g., antimicrobial peptides, growth factors) upon exposure to NIR light. The BPQDs absorb NIR light, generating heat that induces a reversible phase transition in the gelatin matrix, thereby liberating the therapeutic payload [7].

3.1.2. Materials

- Gelatin (Natural polymer): Thermoresponsive matrix material.

- Agarose (Natural polymer): Provides structural integrity to the particle.

- Black Phosphorus Quantum Dots (BPQDs): NIR-responsive photothermal agent.

- Therapeutic Cargo: e.g., Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), antimicrobial peptides.

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS): For buffer preparation.

- Source of NIR Light: e.g., NIR laser (808 nm).

3.1.3. Procedure

- BPQD Synthesis: Prepare BPQDs via liquid exfoliation of bulk black phosphorus in an organic solvent under an inert atmosphere.

- Polymer Solution Preparation: Dissolve gelatin and agarose in warm PBS (at approximately 40-50°C) under gentle stirring to form a homogeneous solution.

- Cargo Loading: Add the therapeutic cargo (e.g., VEGF) and the synthesized BPQDs to the polymer solution. Mix thoroughly to ensure even distribution.

- Particle Formation: Emulsify the mixture in a cold oil phase under high-speed homogenization to form water-in-oil (W/O) emulsion droplets. Cool the emulsion on an ice bath to solidify the particles.

- Washing and Collection: Centrifuge the particles, discard the oil phase, and wash the collected particles multiple times with PBS to remove residual oil and unencapsulated materials.

- Storage: Store the final hybrid particles in PBS at 4°C until use.

3.1.4. Release Kinetics Assessment

- Suspend a known quantity of drug-loaded particles in a release medium (e.g., PBS) in a vial.

- Place the vial in a temperature-controlled shaker.

- At predetermined time intervals, expose the sample to NIR light (e.g., 808 nm laser at a specific power density) for a set duration.

- Following irradiation, centrifuge the samples and collect the supernatant.

- Analyze the supernatant using an appropriate method (e.g., HPLC, ELISA) to quantify the amount of drug released.

- Plot the cumulative drug release versus time to characterize the release profile.

Protocol: Layer-by-Layer (LbL) Assembly for Colon-Targeted Drug Delivery

This protocol describes the fabrication of a multilayered nanocapsule system for targeted oral delivery of biologics like insulin, preventing premature release in the upper gastrointestinal tract (GIT) [9].

3.2.1. Principle LbL assembly involves the alternating deposition of polyelectrolytes with opposing charges onto a core template (e.g., a protein). The number, composition, and compactness of these layers dictate the release kinetics and targeting specificity of the encapsulated biologic [9].

3.2.2. Materials

- Core Biologic: e.g., Insulin (IN).

- Polyelectrolytes: Carboxymethyl starch (CMS, anionic) and Spermine-modified starch (SS, cationic).

- pH-adjusted Buffers: For dissolving and washing layers at optimal pH.

3.2.3. Procedure

- Core Preparation: Dissolve insulin in a buffer at a pH where it carries a net positive charge.

- First Layer Deposition: Under constant stirring, add a solution of anionic CMS to the insulin solution. The CMS will adsorb onto the insulin surface, reversing the surface charge.

- Washing: Centrifuge the obtained IN/CMS particles and re-disperse in fresh buffer to remove non-adsorbed polyelectrolyte.

- Second Layer Deposition: Add a solution of cationic SS to the IN/CMS dispersion. The SS will adsorb onto the anionic surface, forming an IN/CMS/SS nanocapsule.

- Iterative Layering: Repeat the washing and deposition steps to add subsequent layers (e.g., another CMS layer to form IN/CMS/SS/CMS) until the desired number of layers is achieved.

- Critical Parameter Optimization: Systematically vary the ratio of CMS:SS (e.g., 1:2, 1:4, 1:8) during the assembly process. This directly impacts shell compactness, particle size, zeta potential, and ultimately, the release profile [9].

3.2.4. In Vitro Release Testing in Simulated GIT

- Simulated Gastric Fluid (SGF): Incubate the LbL nanocapsules in SGF (pH ~1.2) for a set period (e.g., 2 hours) to simulate stomach transit.

- Simulated Intestinal Fluid (SIF): Transfer the capsules to SIF (pH ~6.8) for a further period to simulate small intestine transit.

- Simulated Colonic Fluid (SCF): Finally, transfer to SCF (often at a higher pH or with specific enzymes) to simulate the colon.

- At each stage, sample the release medium, and quantify the amount of insulin released. A well-designed system will show minimal release in SGF and SIF, with the majority of release triggered in SCF.

Table 2: Impact of CMS:SS Ratio on LbL Nanocapsule Properties and Release Profile [9]

| CMS:SS Ratio | Particle Size (nm) | Zeta Potential (mV) | Premature Insulin Release in Upper GIT |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1:2 | ~26.6 | +3.7 | High (~60%) |

| 1:4 | ~16.0 | +8.9 | Moderate (~26%) |

| 1:8 | ~14.5 | +11.7 | Low (~12%) |

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Polymer Selection and Nanoparticle Fabrication

Mechanism of Stimuli-Responsive Drug Release

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Polymeric Nanoparticle Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | Natural polymer; mucoadhesive, inherent antibacterial properties; used in wound healing patches and microneedle arrays [7]. | CSMNA patches for wound healing [7]. |

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | Synthetic, biodegradable polymer; provides controlled release profiles; widely used in microspheres and implants [6] [8]. | Lornoxicam-loaded microspheres for intra-articular administration [6]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Synthetic polymer; used for "PEGylation" to impart stealth properties, reduce opsonization, and extend circulation time [6] [8]. | Surface coating on liposomes (Doxil) and polymeric nanoparticles [8]. |

| Carboxymethyl Starch (CMS) | Modified natural polymer (anionic); used as a polyelectrolyte in LbL assembly for oral colon-targeted delivery [9]. | LbL nanocapsules for insulin delivery [9]. |

| Black Phosphorus Quantum Dots (BPQDs) | Photothermal agent; enables stimuli-responsive drug release when incorporated into natural polymer matrices like gelatin [7]. | NIR-light responsive hybrid particles for wound healing [7]. |

| Targeting Ligands | Molecules (antibodies, peptides, folates) conjugated to nanoparticle surface to enable active targeting to specific cells (e.g., tumor cells) [6]. | EGF fusion protein for targeting EGFR+ tumors; folic acid for folate-receptor positive cancers [9] [6]. |

The efficacy of a therapeutic agent is fundamentally governed by its ability to reach its site of action in sufficient concentration. Biological barriers—systemic, microenvironmental, and cellular—represent a formidable challenge in drug delivery, often preventing promising candidates from achieving their full therapeutic potential [10]. Polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) have emerged as a groundbreaking platform to navigate this complex landscape. Their versatility, biocompatibility, and capacity for engineered control allow for enhanced drug bioavailability, specific targeting, and minimized off-target effects [11] [12]. This document outlines the key biological hurdles and provides detailed application notes and protocols for using PNPs to overcome them, framed within contemporary drug delivery research.

Biological barriers operate at multiple levels, from the entire organism down to subcellular compartments. The table below categorizes these hurdles and summarizes how PNP-based strategies can address them.

Table 1: Classification of Biological Barriers and PNP Countermeasures

| Barrier Category | Specific Example | Impact on Drug Delivery | PNP-Based Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic Barriers | Rapid clearance by immune system (MPS), Enzymatic degradation in blood [13] [10] | Short circulation half-life, reduced bioavailability | Surface PEGylation to impart "stealth" properties, use of biodegradable polymers [12] [14] |

| Microenvironmental Barriers | Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB), Tumor Microenvironment (acidic pH, high ROS, enzymatic activity) [10] [15] | Prevents drug access to target tissue, reduces efficacy | Stimuli-responsive (pH, redox, enzyme) polymers; surface functionalization with targeting ligands (e.g., peptides, antibodies) [12] [16] |

| Cellular Barriers | Cell membrane, Endolysosomal entrapment, Nuclear envelope [10] | Limits intracellular drug delivery, leads to drug degradation | Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs), endosomolytic agents, nuclear localization signals [12] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The development and evaluation of advanced PNPs require a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PNP Formulation and Testing

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Biodegradable Polymers | Form the nanoparticle matrix; control drug release kinetics. | PLGA, Chitosan, Poly(lactic acid) (PLA), Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) [11] [12] [17] |

| Stimuli-Responsive Polymers | Enable triggered drug release in response to specific pathological cues. | pH-sensitive polymers (e.g., poly(β-amino esters)), redox-sensitive polymers (e.g., with disulfide linkages) [12] [16] |

| Targeting Ligands | Direct PNPs to specific cells or tissues (active targeting). | Antibodies or fragments, peptides (e.g., RGD), folates, aptamers [12] [14] |

| Stabilizers & Surfactants | Control nanoparticle size and stability during fabrication. | Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA), Poloxamers (Pluronic F127, F68) [11] |

| In Vitro Barrier Models | Preclinical evaluation of PNP penetration and transport. | Transwell assays, Organ-on-a-chip models (e.g., liver-on-a-chip, BBB-on-a-chip) [18] [14] [15] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Formulation of PEGylated PLGA Nanoparticles via Nanoemulsion

This protocol describes the preparation of core PNPs with a "stealth" coating to evade the immune system [11] [12].

Application Note: This method is ideal for encapsulating hydrophobic drugs and establishing a long-circulating nanocarrier platform for systemic administration.

Materials:

- Polymer: PLGA (50:50, acid-terminated)

- Surfactant: Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA, 1-5% w/v aqueous solution)

- PEGylation Agent: PLGA-PEG diblock copolymer

- Organic Solvent: Ethyl acetate

- Drug: Model compound (e.g., Docetaxel)

- Equipment: Probe sonicator, magnetic stirrer, centrifugation system

Procedure:

- Organic Phase Preparation: Dissolve 100 mg of PLGA and 10 mg of PLGA-PEG in 5 mL of ethyl acetate. Add the drug (e.g., 10 mg Docetaxel) and vortex until fully dissolved.

- Aqueous Phase Preparation: Place 20 mL of 2% w/v PVA solution in a 50 mL glass beaker.

- Nanoemulsion Formation: While vigorously stirring the aqueous phase, add the organic phase dropwise. Subsequently, probe sonicate the mixture on ice (100 W, 60% amplitude) for 2 minutes to form a stable oil-in-water nanoemulsion.

- Solvent Evaporation: Stir the emulsion overnight at room temperature to allow for complete evaporation of the organic solvent and nanoparticle hardening.

- Purification: Centrifuge the nanoparticle suspension at 15,000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4°C. Wash the pellet with ultrapure water to remove excess PVA and unencapsulated drug. Repeat centrifugation twice.

- Characterization: Re-disperse the final nanoparticle pellet in PBS or water. Characterize for size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential using dynamic light scattering (DLS). Determine drug loading and encapsulation efficiency via HPLC.

Protocol: Fabrication of pH-Responsive PNPs for Tumor Targeting

This protocol outlines the synthesis of PNPs that release their payload in response to the acidic tumor microenvironment [12] [16].

Application Note: These nanoparticles are designed to exploit the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect and provide site-specific drug release, minimizing systemic toxicity.

Materials:

- Polymer: pH-sensitive polymer (e.g., Poly(β-amino ester))

- Crosslinker: Cystamine (for redox sensitivity)

- Drug: Doxorubicin hydrochloride

- Equipment: Dialysis tubing, magnetic stirrer, pH meter

Procedure:

- Polymer Dissolution: Dissolve 50 mg of the pH-sensitive polymer in 4 mL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

- Drug Loading: Add a solution of 5 mg Doxorubicin in 1 mL of DMSO to the polymer solution. Stir gently for 1 hour.

- Nanoparticle Self-Assembly: Transfer the polymer-drug solution into a dialysis tube (MWCO: 3.5-7 kDa). Dialyze against a 100x volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) for 24 hours, changing the buffer every 6-8 hours. During dialysis, the nanoparticles will self-assemble as the solvent is exchanged.

- Crosslinking (Optional): To add dual pH/redox sensitivity, add cystamine dihydrochloride and a carbodiimide crosslinker to the nanoparticle suspension and stir for 4 hours. Purify via dialysis.

- Characterization and Release Testing: Characterize the nanoparticles as in Protocol 4.1. Perform in vitro drug release studies using dialysis in PBS at pH 7.4 and pH 5.5 (simulating the tumor microenvironment) to confirm pH-responsive release.

Visualization of PNP Trafficking and Overcoming Cellular Barriers

The following diagram illustrates the sequential journey of a targeted, stimuli-responsive PNP from systemic circulation to intracellular action.

Diagram 1: PNP Journey from Circulation to Action

Workflow for Evaluating PNP Performance Against Biological Barriers

A standardized workflow is crucial for systematically assessing how well novel PNPs overcome key hurdles.

Diagram 2: PNP Performance Evaluation Workflow

Within the field of polymeric nanoparticle (PNP) drug delivery systems, the protein corona (PC) represents a critical, yet often overlooked, interface that dictates the ultimate biological fate of administered nanocarriers. Upon introduction to any biological fluid (e.g., blood, amniotic fluid), nanoparticles are immediately coated by a dynamic layer of proteins, forming the PC. This corona confers a new "biological identity" that fundamentally redefines how the nanoparticle interacts with cells and tissues, overriding its initial synthetic design [19] [20] [21]. For researchers and drug development professionals, a deep understanding of the PC is no longer optional but essential for rational nanocarrier design. The PC influences every aspect of in vivo performance, including cellular uptake, biodistribution, targeting efficacy, and potential toxicity [20] [22]. This Application Note details the core principles of PC formation, provides quantitative data on its composition and effects, and outlines standardized protocols for its investigation, specifically within the context of advancing PNP-based therapeutic and diagnostic applications.

Core Concepts and Quantitative Data

The Dual Nature of the Protein Corona and Key Influencing Factors

The PC is typically categorized into two layers: the hard corona, consisting of proteins with high affinity that are tightly and almost irreversibly bound to the nanoparticle surface, and the soft corona, comprising proteins that are loosely bound and engaged in dynamic, transient exchange with the surrounding environment [19] [20]. The hard corona is thermodynamically favorable and plays the predominant role in determining the nanoparticle's biological identity [19].

The composition and density of the PC are governed by a complex interplay of nanoparticle physicochemical properties and the nature of the biological environment, as shown in the diagram below.

Diagram Title: Factors Governing Protein Corona Formation

Key Factors Influencing PC Formation:

- Nanoparticle Physicochemical Properties: Size and surface chemistry are primary determinants. Smaller nanoparticles have a higher curvature that influences protein binding affinity. Surface charge (zeta potential) directs electrostatic interactions with proteins, while hydrophobicity drives adsorption through hydrophobic forces [20]. The presence of surface functional groups, such as PEG, can dramatically reduce total protein adsorption and create a "stealth" effect [19] [23].

- Biological Environment Factors: The source and concentration of proteins (e.g., plasma vs. amniotic fluid) lead to distinct coronas. Physiological conditions like pH and temperature, as well as the duration of exposure (time), further modulate the corona's composition and dynamics, a phenomenon described by the Vroman effect [20] [22].

Impact of Polymer Type and PEGylation on the Protein Corona

The core polymer and surface architecture of PNPs directly determine the PC's properties, which in turn dictate cellular association and in vivo biodistribution. The following table summarizes experimental data from a study investigating polymeric nanoparticles for intra-amniotic delivery [19] [24].

Table 1: Protein Corona Characteristics and Biological Effects of Different Polymeric Nanoparticles in Amniotic Fluid

| Nanoparticle Type | Hydrodynamic Diameter (nm) | Surface Charge (mV) | Key Proteins in Corona | In Vitro Cellular Association | Primary In Vivo Biodistribution (Fetal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLGA | ~140-190 [19] | -6 to -10 [19] | Not Specified | Low [24] | Not Detected [24] |

| PLGA-PEG | ~140-190 [19] | -6 to -10 [19] | High Albumin [24] | High [24] | Lung [24] |

| PLA-PEG | ~140-190 [19] | -6 to -10 [19] | Keratins [24] | Not Specified | Bowel [24] |

| PACE-PEG | ~140-190 [19] | ~+5 [19] | High Albumin [24] | High [24] | Lung [24] |

Critical Insights from the Data:

- The Role of PEGylation: Surface PEGylation creates a dense brush conformation that confers a "stealth" property, significantly enhancing colloidal stability in biological fluids like amniotic fluid. This stability is crucial for successful in vivo delivery, as non-PEGylated NPs (PLGA) failed to distribute to fetal organs [19] [24].

- Corona Composition Drives Targeting: The specific protein profile in the corona is linked to organ-specific targeting. PLGA-PEG and PACE-PEG NPs, which accumulated high levels of albumin in their corona, showed preferential distribution to the fetal lung. In contrast, PLA-PEG NPs, with a corona rich in keratins, distributed exclusively to the fetal bowel, suggesting that pre-adsorbed proteins can act as endogenous targeting ligands [24].

- Cellular Association Correlation: In vitro experiments on A549 cells demonstrated a direct correlation between the amount of albumin in the PC and the level of cellular association, highlighting how the PC directly mediates cell-NP interactions [24].

Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed methodology for isolating and characterizing the protein corona formed on polymeric nanoparticles, a fundamental prerequisite for understanding their biobehavior.

Protocol: Protein Corona Isolation and Characterization via Density Gradient Ultracentrifugation

This protocol is adapted from advanced methods developed for lipid nanoparticles [25] and tailored for the higher density of polymeric NPs like PLGA and PLA.

I. Principle: This method separates protein-NP complexes from unbound proteins and endogenous biological nanoparticles (e.g., exosomes, lipoproteins) based on their buoyant density using a continuous sucrose gradient. This avoids the aggregation and corona disruption associated with high-speed pelleting centrifugation [25].

II. Materials and Reagents:

- Polymeric Nanoparticles (e.g., PLGA, PLA, PACE), sterile

- Relevant Biological Fluid (e.g., human plasma, amniotic fluid)

- Ultracentrifuge and Swinging-Bucket Rotor

- Sucrose, Ultra-Pure

- PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline), pH 7.4

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) system

III. Procedure:

- NP Incubation: Incubate a known concentration of PNPs (e.g., 1 mg/mL) with the biological fluid (e.g., 50% plasma in PBS) for a predetermined time (e.g., 1 hour) at 37°C with gentle agitation.

- Gradient Preparation: Prepare a continuous sucrose density gradient (e.g., 10-60% w/v in PBS) in ultracentrifuge tubes. Use a gradient maker for precise linearity.

- Sample Layering: Carefully layer the NP-biofluid incubation mixture on top of the pre-formed sucrose gradient.

- Ultracentrifugation: Centrifuge at approximately 160,000 × g for 16-24 hours at 4°C. This extended duration is critical for effective separation from endogenous particles [25].

- Fraction Collection: After centrifugation, carefully fractionate the gradient from the top. The protein-NP complexes will form a band at their buoyant density.

- Fraction Analysis: Analyze fractions for nanoparticle content (via fluorescence or absorbance) and protein content (e.g., BCA assay). Pool fractions rich in protein-NP complexes.

- Buffer Exchange and Washing: Use centrifugal filters (e.g., 100 kDa MWCO) to exchange the buffer into pure PBS or water and concentrate the samples. This step removes sucrose and loosely bound ("soft corona") proteins.

- Protein Elution and Identification:

- Denature the recovered complexes with Laemmli buffer.

- Analyze protein composition using SDS-PAGE for a general profile.

- For precise identification and quantification, digest the proteins with trypsin and analyze the peptides via LC-MS/MS.

Protocol: Evaluating Cellular Uptake of Corona-Coated Nanoparticles

I. Principle: This protocol assesses how the pre-formed PC influences the interaction of PNPs with target cells in vitro, providing a functional readout of the PC's biological activity.

II. Procedure:

- Prepare PC-Coated NPs: Generate PC-coated NPs using the isolation method above or a simplified incubation followed by buffer exchange to remove unbound proteins.

- Cell Seeding: Seed relevant cell lines (e.g., A549 for lung, Caco-2 for intestine) in multi-well plates and culture until ~80% confluent.

- NP Treatment: Treat cells with PC-coated NPs and pristine (non-coated) NPs at equal concentrations. Include a fluorescence label (e.g., DiD, Cy5) in the NP formulation for quantification.

- Incubation and Washing: Incubate for a set period (e.g., 2-4 hours) at 37°C. Subsequently, wash cells thoroughly with PBS to remove non-internalized NPs.

- Analysis:

- Flow Cytometry: Trypsinize and resuspend cells. Analyze cell-associated fluorescence using a flow cytometer to quantify the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) per cell, which corresponds to NP uptake.

- Confocal Microscopy: Fix washed cells and stain nuclei and actin cytoskeleton. Use a confocal microscope to visually confirm internalization and subcellular localization of the fluorescent NPs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Protein Corona and Biodistribution Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Biodegradable Polymers (PLGA, PLA, PACE) | Form the core matrix of the nanoparticle; determine biodegradability, cargo release kinetics, and initial surface properties for protein interaction. [19] [26] | PLGA is FDA-approved. PACE offers high nucleic acid encapsulation efficiency and tunable cytotoxicity. [19] |

| PEGylated Lipids / Polymers (e.g., PLGA-PEG) | Impart "stealth" properties by reducing opsonin adsorption, enhancing circulation time, and influencing PC composition. [19] [24] | PEG density is inversely correlated with total protein adsorption. High PEG density forms a brush conformation. [19] |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | Commonly used as a surfactant and stabilizer during nanoparticle formulation via emulsion. [19] | Residual PVA on the NP surface can influence subsequent protein corona formation and must be characterized. [19] |

| Apolipoproteins (ApoA1, ApoE) & Clusterin | Key "dysopsonins" (stealth proteins) in the corona. Pre-coating with these can actively engineer a stealth corona to reduce macrophage uptake. [22] [23] | Stability of pre-coated layers in full plasma is a key research challenge. Significant interspecies differences exist. [23] |

| Density Gradient Media (Sucrose, Iodixanol) | Enable gentle separation of protein-NP complexes from unbound proteins and endogenous particles for clean corona analysis. [25] | Critical for avoiding artifacts and obtaining a true representation of the hard corona composition. |

Visualization of the Protein Corona's Impact on Biodistribution

The following diagram synthesizes the critical steps and decision points that link nanoparticle properties to ultimate biodistribution through the mechanism of protein corona formation.

Diagram Title: How Protein Corona Determines Nanoparticle Fate In Vivo

The protein corona is not a confounding artifact but a fundamental determinant of the in vivo journey of polymeric nanoparticles. As demonstrated, its composition, governed by the NP's synthetic identity and biological environment, directly controls cellular interactions and biodistribution profiles. Moving forward, the field is transitioning from simply observing the PC to actively engineering it. Strategies include pre-coating NPs with specific "stealth" or "targeting" proteins like ApoA1 to dictate biological outcomes [23], and using Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) to predict corona composition based on NP physicochemical parameters, thereby accelerating rational design [20]. Furthermore, leveraging the PC as a diagnostic tool by analyzing its "personalized" fingerprint in patient biofluids represents a promising frontier for disease detection [20]. For researchers, integrating robust PC characterization into the standard development workflow for polymeric nanoparticle drug delivery systems is no longer a niche activity but a critical step toward creating effective, targeted, and translatable nanomedicines.

In the development of polymeric nanoparticle (PNP) drug delivery systems, achieving targeted delivery and optimal therapeutic efficacy hinges on the precise engineering of physicochemical properties. Size, shape, and surface charge are fundamental design parameters that collectively govern the biological identity of nanoparticles, influencing their stability, circulation half-life, cellular uptake mechanisms, and biodistribution profiles [27] [28]. A deep understanding of the structure-function relationships dictated by these parameters is essential for advancing PNP-based strategies from laboratory research to clinical application. This document provides a detailed overview of these critical parameters, supported by quantitative data and standardized experimental protocols, to guide researchers in the rational design of polymeric nanocarriers.

Quantitative Analysis of Key Parameters

The following tables summarize the target ranges and biological implications of size, shape, and surface charge, as established by current research.

Table 1: Optimal Size Ranges for Different Biological Processes

| Biological Process | Optimal Size Range | Biological Implication & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Avoiding Renal Clearance | >10 nm [27] | Prevents rapid elimination through kidney filtration. |

| Reducing MPS/Uptake | ~150 nm [29] | Helps evade phagocytosis by the mononuclear phagocyte system. |

| Enhancing Cellular Uptake | ~50-100 nm [28] | Generally favorable for efficient cellular internalization. |

| Promoting EPR Effect | 10-200 nm [27] | Facilitates passive accumulation in tumor tissues through leaky vasculature. |

Table 2: Influence of Surface Charge on Biological Interactions

| Surface Charge (Zeta Potential) | Key Biological Interactions | Considerations for Design |

|---|---|---|

| Positive (Cationic) | Promotes strong electrostatic interaction with anionic cell membranes, generally leading to higher cellular uptake [29] [28]. | Can induce higher cytotoxicity and is more rapidly cleared from circulation by the immune system [27]. |

| Neutral | Minimizes non-specific interactions, leading to longer circulation times (e.g., via PEGylation) [27]. | May require functionalization with targeting ligands to achieve specific cellular uptake. |

| Negative (Anionic) | Can reduce protein opsonization compared to cationic surfaces but may still be recognized by specific serum proteins [27]. | A strongly negative charge may still lead to clearance by the MPS; a slightly negative to neutral charge (~-15 to 0 mV) is often optimal for longevity [29]. |

Table 3: Impact of Nanoparticle Shape on Delivery Efficacy

| Shape | Impact on Delivery and Biological Interactions |

|---|---|

| Spherical | The most commonly studied shape; cellular uptake is highly dependent on diameter [27]. |

| Rod / Cylindrical | Altered cellular internalization kinetics and circulation times compared to spheres [27]. |

| Other (Discoidal, etc.) | Different shapes can significantly influence margination, vascular transport, and phagocytosis [27]. |

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Control and Characterization

Protocol: Controlling Nanoparticle Size via Flash Nanoprecipitation

Principle: This flow-based method provides superior control over particle size and distribution by enabling rapid, homogeneous mixing, which leads to consistent nucleation and growth of polymeric nanoparticles [30].

Materials:

- Polymer: e.g., PEG--PLGA (Poly(lactic--co-glycolic acid))

- Organic Solvent: Water-miscible (e.g., Tetrahydrofuran, Acetone)

- Aqueous Solution: Deionized water or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Equipment: Syringe pumps, precision-bore tubing, mixing chamber, collection vessel

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve the polymer and hydrophobic drug (if applicable) in the organic solvent to form the organic phase.

- Apparatus Setup: Load the organic and aqueous phases into separate syringes mounted on syringe pumps. Connect the syringes to the inlets of a confined impingement jet (CIJ) or other multi-inlet vortex mixer.

- Mixing and NP Formation: Simultaneously drive the two streams at high velocity (typical total flow rate >10 mL/min) into the mixing chamber. The rapid and homogeneous mixing causes the polymer to supersaturate and precipitate, forming nanoparticles.

- Solvent Removal: Collect the effluent and stir gently to allow for the diffusion and removal of residual organic solvent.

- Purification: Purify the resulting nanoparticle suspension by dialysis or tangential flow filtration to remove solvents and unencapsulated cargo.

Notes: Particle size can be tuned by adjusting parameters such as polymer concentration, molecular weight, flow rate ratio, and total flow rate [30].

Protocol: Modifying Surface Charge and Coating

Principle: The surface charge (zeta potential) of PNPs is critical for their stability and interaction with biological components. Coating with hydrophilic polymers like PEG (polyethylene glycol) is a standard method to confer a neutral charge and "stealth" properties [27].

Materials:

- Pre-formed polymeric nanoparticles (e.g., from Protocol 3.1)

- PEG-lipid (e.g., DSPE-PEG) or other functionalized PEG polymers

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Lab-scale stirrer/hot plate

Procedure:

- Post-Formation Coating: Add a solution of DSPE-PEG in PBS or another suitable buffer directly to the prepared nanoparticle suspension. A typical final PEG-lipid concentration is 0.1-1.0 mg/mL.

- Incubation: Incubate the mixture for 30-60 minutes at room temperature or a temperature above the phase transition of the lipid (e.g., 40-50°C) with gentle stirring.

- Purification: Purify the PEG-coated nanoparticles via dialysis, gel filtration, or centrifugation to remove unincorporated PEG-lipid.

- Verification: Measure the zeta potential of the nanoparticles before and after coating using dynamic light scattering (DLS). Successful PEGylation is indicated by a shift towards neutral potential (approximately 0 to -10 mV) and a potential reduction in polydispersity index.

Notes: Alternative coatings such as poly(2-oxazoline) (POx), polypeptides, or zwitterionic polymers can be explored to mitigate potential anti-PEG immunity [27].

Protocol: Characterizing Size, Surface Charge, and Morphology

Principle: A multi-technique approach is required to accurately characterize the physicochemical properties of PNPs, as each method provides complementary information [31].

Materials:

- Nanoparticle suspension

- Deionized water or appropriate buffer (for DLS/Zeta Potential)

- Filter membranes (e.g., 0.22 or 0.45 µm)

- Copper grids with carbon support film (for TEM)

- Staining solution (e.g., uranyl acetate)

Procedure:

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) for Hydrodynamic Size:

- Dilute a small aliquot of the nanoparticle suspension in a clean, particle-free buffer to avoid scattering from dust or aggregates.

- Transfer to a disposable cuvette and measure the intensity-based size distribution and polydispersity index (PDI) using a DLS instrument. A PDI <0.2 is generally considered monodisperse.

Laser Doppler Electrophoresis for Zeta Potential:

- Dilute the nanoparticle sample in a low-conductivity buffer (e.g., 1 mM KCl) or a standard specified by the manufacturer.

- Load the sample into a folded capillary cell or appropriate cell.

- Measure the electrophoretic mobility and calculate the zeta potential using the Smoluchowski equation.

Electron Microscopy for Morphology and Actual Size:

- Sample Preparation: Place a small drop (5-10 µL) of diluted nanoparticle suspension onto a TEM grid. After 1-2 minutes, wick away the excess liquid with filter paper. Negative stain with 1-2% uranyl acetate for 30-60 seconds, then wick away the excess and allow the grid to air-dry completely.

- Imaging: Image the samples using Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) at appropriate accelerating voltages (e.g., 80-120 kV). TEM provides direct visualization of nanoparticle core size, shape, and morphology (e.g., spherical, cylindrical, vesicular) [31].

Visualization of Design Logic and Biological Fates

The following diagrams illustrate the logical framework for PNP design and the subsequent biological pathways they encounter.

Diagram 1: The interrelationship between key design parameters and the development pathway for polymeric nanoparticles.

Diagram 2: The influence of nanoparticle properties on key biological pathways post-administration. MPS: Mononuclear Phagocyte System; EPR: Enhanced Permeability and Retention.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PNP Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Biodegradable Polymers | The core structural material forming the nanoparticle matrix. | PLGA, PLA, PCL, Chitosan and its derivatives [29] [28]. |

| PEGylated Lipids/Polymers | Impart "stealth" properties to reduce opsonization and extend circulation half-life. | DSPE-PEG, PLGA--PEG block copolymers [27] [30]. |

| Fluorescent Dyes | Enable tracking and visualization of nanoparticles in in vitro and in vivo studies. | Rhodamine B (RhB), FITC, Coumarin-6 [29] [28]. |

| Characterization Tools | Essential for measuring the critical quality attributes (CQAs) of the final formulation. | DLS for size, Zeta Potential analyzer, TEM/SEM for morphology [31]. |

From Bench to Bedside: Fabrication Techniques and Therapeutic Applications

Polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) are at the forefront of advancing drug delivery systems, offering unparalleled control over therapeutic agent release, enhanced targeting precision, and improved bioavailability [32]. The efficacy and application of these nanocarriers are profoundly influenced by their fabrication method, which dictates critical attributes such as particle size, morphology, drug loading efficiency, and release kinetics [33] [34]. This article details three core fabrication techniques—nanoprecipitation, emulsification, and ionic gelation—within the context of polymeric nanoparticle drug delivery research. It provides detailed application notes and standardized protocols to support scientists and drug development professionals in optimizing nanoparticle formulations for pre-clinical and clinical translation.

Nanoprecipitation

Principle and Applications

Nanoprecipitation, also termed solvent displacement or the "Ouzo effect," is a versatile and efficient technique for formulating PNPs [33] [34]. This method is based on the precipitation of a polymer and a hydrophobic drug from a water-miscible organic solution upon addition to an aqueous phase (anti-solvent) [35]. The process involves four key stages: supersaturation, nucleation, growth by condensation, and growth by coagulation, leading to the formation of a colloidal suspension of nanoparticles [35] [34]. Its advantages include simple methodology, minimal energy input, high reproducibility, and the general absence of surfactants, thereby reducing potential toxicity [33] [34]. Nanoprecipitation is suitable for encapsulating both hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs and has been successfully applied for the controlled delivery of various therapeutic agents [35].

Critical Experimental Parameters

The properties of the resulting nanoparticles are highly dependent on several process and formulation parameters. Key factors include the polymer type and concentration, solvent and anti-solvent selection, organic-to-aqueous phase ratio, and the mixing method and kinetics [33] [35]. Rapid mixing, as achieved in flash (FNP) or microfluidic nanoprecipitation (MNP), provides superior control over particle size and distribution compared to conventional batch mixing [33] [34].

Table 1: Key Parameters in Nanoprecipitation Optimization

| Parameter | Impact on Nanoparticle Characteristics | Common Options / Optimal Range |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Type | Determines biodegradability, drug compatibility, and release kinetics. | PLGA, PLA, PCL, PLA-PEG, chitosan [33] [34]. |

| Polymer Concentration | Influences particle size and drug loading capacity. | Typically 0.1 - 1% (w/v); must be optimized [34]. |

| Solvent Choice | Affects polymer solubility and rate of diffusion into anti-solvent. | Acetone, tetrahydrofuran (THF), ethanol [33] [35]. |

| Solvent-to-Anti-solvent Ratio | Impacts supersaturation level and final particle size. | Commonly 1:5 to 1:10 (organic:aqueous) [33]. |

| Mixing Method | Governs mixing time, homogeneity, and batch-to-batch consistency. | Batch (pipette/dropwise), Flash (FNP), Microfluidic (MNP) [33]. |

| Drug-to-Polymer Ratio | Critical for achieving high encapsulation efficiency. | Varies by drug-polymer system; requires experimental optimization [35]. |

Standardized Protocol for Batch Nanoprecipitation

Materials:

- Polymer (e.g., PLGA, 50 mg)

- Hydrophobic drug (e.g., 5 mg)

- Organic solvent, water-miscible (e.g., acetone, 10 mL)

- Aqueous anti-solvent (e.g., deionized water, 50 mL)

- Magnetic stirrer and stir bar

- Syringe and needle or pipette

Procedure:

- Organic Phase Preparation: Dissolve the polymer and the drug completely in the organic solvent to form a clear solution.

- Aqueous Phase Preparation: Place the aqueous anti-solvent (water) in a beaker under moderate magnetic stirring (500-600 rpm).

- Precipitation: Using a syringe or pipette, add the organic phase dropwise (e.g., at a rate of 0.5-1 mL/min) into the aqueous phase under constant stirring.

- Stirring: Continue stirring the resulting milky suspension for 3-4 hours at room temperature to allow for nanoparticle formation and evaporation of the organic solvent.

- Purification: Purify the nanoparticle suspension by centrifugation (e.g., 20,000 rpm for 30 minutes) and resuspend the pellet in distilled water or buffer for further analysis and use.

Diagram 1: Nanoprecipitation Workflow

Ionic Gelation

Principle and Applications

Ionic gelation is a mild, self-assembly process ideal for encapsulating hydrophilic drugs and sensitive biomolecules [36] [37]. This method relies on the electrostatic cross-linking between a charged polymer (polyelectrolyte) and an oppositely charged ion or polymer [37]. The most common system involves the cationic polysaccharide chitosan and the polyanion sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP) [36]. When mixed, the NH₃⁺ groups on chitosan form ionic linkages with the P₃O₁₀⁵⁻ groups of TPP, leading to the instantaneous gelation and formation of a nanoparticle network [36] [37]. The key advantages of this technique are its simplicity, execution in an aqueous environment, avoidance of organic solvents, and use of generally recognized as safe (GRAS) materials [36] [38].

Critical Experimental Parameters

The characteristics of chitosan-TPP nanoparticles are highly sensitive to synthesis conditions. A systematic optimization of the following parameters is crucial [36]:

Table 2: Key Parameters in Ionic Gelation Optimization

| Parameter | Impact on Nanoparticle Characteristics | Common Options / Optimal Range |

|---|---|---|

| Chitosan Parameters | ||

| - Molecular Weight | Affects viscosity, particle size, and gel density. | Low to medium molecular weight is often preferred. |

| - Degree of Deacetylation | Determines the number of available NH₃⁺ sites for cross-linking. | > 75% is typical [36]. |

| - Concentration | Higher concentrations can lead to larger particles or aggregation. | 0.1% - 0.5% (w/v) [36]. |

| Solution pH | Critically affects chitosan chain charge and expansion. | pH 4.6 - 5.5 is optimal for chitosan protonation [36]. |

| TPP Concentration | Impacts cross-linking density, particle size, and stability. | 0.1% - 0.5% (w/v); Chitosan:TPP mass ratio of ~3:1 to 5:1 [36]. |

| Mixing Conditions | ||

| - Stirring Speed | Influences mixing homogeneity and particle size. | 500 - 700 rpm [36]. |

| - Addition Time (Dripping) | Affects the rate of cross-linking and particle uniformity. | 2 - 6 minutes for 1.7 mL of TPP solution [36]. |

Standardized Protocol for Chitosan-TPP Nanoparticle Synthesis

Materials:

- Chitosan (low molecular weight, 75-85% deacetylation)

- Sodium Tripolyphosphate (TPP)

- Acetic acid (1% v/v)

- Sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 20% solution for pH adjustment)

- Magnetic stirrer

- Syringe and needle or peristaltic pump

Procedure:

- Chitosan Solution Preparation: Dissolve chitosan in 1% acetic acid solution to a final concentration of 0.1% (w/v). Adjust the pH of the solution to 5.5 using 20% NaOH. Filter the solution through a 0.22 µm membrane.

- TPP Solution Preparation: Dissolve TPP in deionized water to a concentration of 0.1% (w/v).

- Cross-linking and Nanoparticle Formation: Under constant magnetic stirring at 500 rpm, add 1.7 mL of the TPP solution dropwise (e.g., over 2 minutes) into 5 mL of the chitosan solution.

- Stirring: Continue stirring the suspension for 30 minutes at room temperature to allow for nanoparticle hardening.

- Purification and Stabilization: Purify the nanoparticles by centrifugation or dialysis. To enhance stability during purification and storage, surfactants like Poloxamer 188 or Polysorbate 80 (1% w/v) can be added [36]. For long-term storage, freeze-drying with cryoprotectants like trehalose or sucrose (5-10% w/v) is recommended [36].

Diagram 2: Ionic Gelation Workflow

Emulsification-Solvent Evaporation

Principle and Applications

The emulsification-solvent evaporation method is a widely used technique for encapsulating hydrophobic drugs [39]. The process involves two primary steps: first, the formation of a primary emulsion, where a polymer and drug dissolved in a water-immiscible organic solvent (e.g., dichloromethane or ethyl acetate) is emulsified in an aqueous phase containing a stabilizer (emulsifier) to form an oil-in-water (O/W) emulsion [39] [40]. Second, the organic solvent is evaporated under reduced pressure or stirring, leading to the precipitation of the polymer and the formation of solid nanoparticles [39]. The method provides high encapsulation efficiencies for lipophilic compounds and allows for control over particle size through homogenization energy [40].

Critical Experimental Parameters

The stability and characteristics of the nanoemulsion and final nanoparticles are governed by several factors [39] [40]:

Table 3: Key Parameters in Emulsification-Solvent Evaporation Optimization

| Parameter | Impact on Nanoparticle Characteristics | Common Options / Optimal Range |

|---|---|---|

| Oil-to-Water Phase Ratio | Influences emulsion type and droplet size. | Varies; a small organic phase volume is typical for O/W emulsions. |

| Emulsifier/Stabilizer Type & Concentration | Critical for preventing droplet coalescence and ensuring colloidal stability. | Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polysorbates, poloxamers, caseinates [39] [40]. |

| Homogenization Method & Energy | Directly determines the droplet and final particle size. | High-speed homogenization (e.g., 2,000-10,000 rpm) or ultrasonication [39]. |

| Solvent Removal Rate | Affects particle morphology and drug distribution. | Stirring at room pressure or under reduced pressure. |

| Environmental Stresses (pH, T, electrolytes) | Can destabilize the emulsion; parameters must be optimized for stability [39]. | Alkaline pH (e.g., 9), temperatures up to 50°C, electrolyte concentrations up to 100 mM may be tolerated in optimized systems [39]. |

Standardized Protocol for O/W Nanoemulsion Formation

Materials:

- Polymer (e.g., PLGA, 100 mg)

- Hydrophobic drug (e.g., 10 mg)

- Organic solvent, water-immiscible (e.g., dichloromethane, 10 mL)

- Emulsifier (e.g., Polyvinyl Alcohol - PVA, 1-2% w/v solution)

- High-speed homogenizer or ultrasonic probe

- Magnetic stirrer and stir bar

Procedure:

- Organic Phase Preparation: Dissolve the polymer and drug in the water-immiscible organic solvent.

- Aqueous Phase Preparation: Prepare an aqueous solution of the emulsifier (e.g., 1% PVA in water).

- Primary Emulsion Formation: Add the organic phase to the aqueous phase. Immediately homogenize the mixture using a high-speed homogenizer (e.g., 10,000 rpm for 5 minutes) or an ultrasonic probe to form a coarse O/W emulsion.

- Size Reduction: Further reduce the droplet size by sonication (e.g., on an ice bath for 1-2 minutes at a specific power output) to form a nanoemulsion.

- Solvent Evaporation: Stir the nanoemulsion continuously at room temperature for several hours (or under reduced pressure) to evaporate the organic solvent, solidifying the nanoparticles.

- Purification: Collect the nanoparticles by ultracentrifugation, wash repeatedly with water to remove excess emulsifier, and resuspend for analysis.

Diagram 3: Emulsification-Solvent Evaporation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for Polymeric Nanoparticle Fabrication

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Formulation |

|---|---|---|

| Biodegradable Polymers | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), Poly(lactic acid) (PLA), Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) [33] [34] | Forms the nanoparticle matrix; determines biodegradability, drug release profile, and biocompatibility. |

| Natural Polyelectrolytes | Chitosan, Sodium Alginate, Hyaluronic Acid [36] [37] [38] | Acts as the primary gelling or structural polymer in ionic gelation; offers mucoadhesion and mild processing. |

| Cross-linking Agents | Sodium Tripolyphosphate (TPP), Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) [36] [37] | Induces ionic gelation by forming bridges between polyelectrolyte chains to create a nanoparticle network. |

| Emulsifiers & Stabilizers | Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA), Poloxamer 188, Polysorbate 80, Sodium Caseinate [36] [39] [40] | Reduces interfacial tension during emulsification; prevents aggregation and stabilizes the formed nanoparticles. |

| Cryoprotectants | Trehalose, Sucrose [36] | Protects nanoparticle structure from ice crystal damage and prevents aggregation during freeze-drying for long-term storage. |

In the development of polymeric nanoparticle (PNP) drug delivery systems, advanced characterization of size, stability, and drug release profiles is paramount for ensuring therapeutic efficacy and successful clinical translation [6]. These physicochemical parameters directly influence critical biological interactions, including biodistribution, cellular uptake mechanisms, and controlled release kinetics at target sites [41] [42]. This document provides detailed application notes and standardized protocols to enable researchers to obtain reliable, reproducible characterization data that can effectively guide PNP formulation optimization.

The characterization process presents significant challenges due to the nanoscale dimensions and dynamic behavior of PNPs in complex biological environments [42]. No single technique provides a complete picture; instead, a complementary, orthogonal approach combining multiple methodologies is essential for comprehensive understanding [43]. The following sections outline standardized methodologies and data interpretation frameworks to address these challenges systematically.

Particle Size and Size Distribution Analysis

Orthogonal Technique Approach

Particle size directly impacts PNPs' in vivo behavior, including circulation time, tissue penetration, and cellular internalization. Employing orthogonal techniques provides a more comprehensive understanding of PNP size distributions than any single method could achieve independently [43].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Sizing Techniques for Polymeric Nanoparticles

| Technique | Size Range | Principle | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | 1 nm - 6 μm | Measures Brownian motion to calculate hydrodynamic diameter | Rapid analysis, high sensitivity to large aggregates, minimal sample preparation [41] [43] | Intensity-weighted distribution biased toward larger particles, assumes spherical morphology [41] |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) | 10 - 2000 nm | Tracks and analyzes individual particle movement | Direct visualization, provides concentration data, superior for polydisperse samples [41] | Lower concentration range, analysis time longer than DLS [41] |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | <1 nm - μm | High-resolution electron imaging | Ultimate size and morphological detail, reveals structural heterogeneity [41] [42] | Vacuum conditions may alter samples, dry-state measurement, complex sample preparation [41] |

Step-by-Step Protocol for Multi-Technique Sizing

Protocol Title: Comprehensive Size Analysis of Polymeric Nanoparticles Using Orthogonal Techniques

Principle: This protocol leverages the complementary strengths of DLS, NTA, and TEM to obtain a complete understanding of PNP size distribution and morphology [41] [43].

Materials:

- Purified PNP suspension (e.g., PLGA, chitosan-based systems)

- Dialysis buffer (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4)

- Filtered, deionized water (0.02 μm filtered)

- TEM grids (e.g., copper grids with carbon support film)

- Negative stain (e.g., 2% uranyl acetate)

- DLS instrument (e.g., Malvern Zetasizer)

- NTA instrument (e.g., Malvern NanoSight)

- TEM instrument

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Dialyze PNP suspensions against an appropriate buffer to remove free polymer and surfactants.

- Prepare three dilutions of the sample in filtered buffer (typically 1:10 to 1:100) to identify optimal concentration ranges for each instrument.

Dynamic Light Scattering:

- Transfer 1 mL of appropriately diluted sample into a disposable sizing cuvette.

- Equilibrate to measurement temperature (typically 25°C or 37°C) for 300 seconds.

- Perform minimum of 12 measurements per sample with automatic attenuation selection.

- Record intensity-weighted size distribution, polydispersity index (PdI), and cumulants mean (Z-average).

Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis:

- Load diluted sample via sterile syringe, ensuring careful exclusion of air bubbles.

- Capture five 60-second videos at camera level 14-16, ensuring particle count between 20-100 particles/frame.

- Process all videos with identical detection threshold and screen gain settings.

- Report mode and mean size from number-weighted size distribution.

Transmission Electron Microscopy:

- Glow-discharge TEM grids to enhance hydrophilicity.

- Apply 5 μL of sample to grid, incubate 60 seconds, blot excess with filter paper.

- Wash with 5 μL filtered water, blot immediately.

- Stain with 5 μL uranyl acetate (2%) for 30 seconds, blot thoroughly.

- Image at multiple magnifications (e.g., 10,000x to 50,000x) across grid squares.

Data Interpretation Guidelines:

- Compare DLS (intensity-weighted) and NTA (number-weighted) distributions to identify presence of aggregates or subpopulations [41].

- Use TEM data to validate size measurements and provide critical information on particle morphology and structural homogeneity [42].

- Significant discrepancies between DLS and NTA often indicate sample polydispersity requiring formulation optimization.

Stability Assessment Under Physiological Conditions

Critical Stability Parameters

PNP stability extends beyond shelf-life to encompass performance in biologically relevant environments. Key parameters include colloidal stability (resistance to aggregation), structural integrity under physiological conditions, and interaction with biological components [43].

Table 2: Key Stability Parameters and Assessment Methodologies

| Stability Parameter | Assessment Technique | Experimental Conditions | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colloidal Stability | DLS (size and PDI), Zeta Potential | Storage in formulation buffer (4°C, 25°C), freeze-thaw cycling | Size change < 10%, PDI < 0.2, zeta potential change < 5 mV |

| Serum Stability | DLS, NTA, Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy | Incubation in 10-50% FBS/PBS at 37°C with gentle agitation | Limited size increase, no macroscopic aggregation |

| Storage Stability | DLS, HPLC (drug content), Visual Inspection | Accelerated stability (4°C, 25°C, 40°C) over 1-6 months | Maintains physicochemical properties, no precipitation |

Protocol for Serum Stability Assessment

Protocol Title: Evaluation of Polymeric Nanoparticle Stability in Biological Media

Principle: This protocol assesses the stability of PNPs upon exposure to biologically relevant media, simulating in vivo conditions and predicting performance upon administration [43].

Materials:

- PNP suspension (1-10 mg/mL in PBS)

- Fetal bovine serum (FBS) or human serum

- Incubator/shaker maintaining 37°C

- DLS instrument

- NTA instrument

- Centrifugal filters (100 kDa MWCO)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Pre-warm serum to 37°C in water bath.

- Mix PNP suspension with serum to achieve final concentrations of 10%, 25%, and 50% serum (v/v).

- Prepare control samples in PBS alone.

Time-Course Measurements:

- Incubate serum-PNP mixtures at 37°C with gentle agitation (50-100 rpm).

- Withdraw aliquots (50 μL) at predetermined time points (0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 hours).

- For DLS analysis, dilute samples 1:10 in corresponding serum-PBS mixture to maintain constant scattering background.

- For NTA analysis, dilute samples 1:100-1:1000 in filtered PBS to achieve optimal particle density.

Data Collection:

- Perform DLS measurements in triplicate at each time point.

- Capture three 60-second NTA videos per time point.

- Centrifuge select samples through 100 kDa filters at 14,000 × g for 45 minutes to separate released drug for quantification by HPLC.

Interpretation and Analysis:

- Plot hydrodynamic diameter, PDI, and particle concentration versus time.

- Significant increases in size indicate aggregation or protein corona formation.

- Decreasing particle concentration suggests dissolution or extensive aggregation beyond detection limits.

- Correlation of physical stability with drug release profiles provides insights into formulation robustness.

Drug Release Kinetics Profiling

Methodological Considerations

Accurate characterization of drug release profiles is essential for predicting in vivo performance but presents significant technical challenges. Traditional methods like dialysis membrane (DM) approaches may misestimate release kinetics due to inadequate separation or additional diffusion barriers [44].

Table 3: Comparison of In Vitro Release Study Methods for Polymeric Nanoparticles

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dialysis Membrane (DM) | Separation of free drug through semi-permeable membrane | Simple setup, widely used | Potential underestimation of burst release, membrane adsorption issues, additional diffusion barrier [44] |

| Sample and Separate with Centrifugal Ultrafiltration (SS+CU) | Physical separation via centrifugal filtration | Direct measurement of free drug concentration, maintains sink conditions, no additional barriers [44] | Requires validation of separation efficiency, potential for continued release during separation |

| Continuous Flow (CF) | Continuous replacement of release medium | Maintains perfect sink conditions | Complex setup, low throughput, potential for particle loss [44] |

Recent investigations demonstrate that the Sample and Separate method with Centrifugal Ultrafiltration (SS+CU), when combined with USP apparatus II (paddle), provides superior accuracy and reproducibility for characterizing drug release from PNPs [44].

Advanced Protocol for Drug Release Studies

Protocol Title: Sample and Separate Method with Centrifugal Ultrafiltration for Drug Release Profiling

Principle: This protocol utilizes centrifugal ultrafiltration to efficiently separate released drug from nanoparticles during time-course studies, providing accurate release kinetics without the additional diffusion barrier of dialysis membranes [44].

Materials:

- USP Apparatus II (paddle apparatus)

- Centrifugal ultrafiltration devices (e.g., Amicon Ultra, 100 kDa MWCO)

- Release medium (e.g., PBS with 0.1-0.5% w/v SDS to maintain sink conditions)

- Water bath maintaining 37°C

- HPLC system with appropriate column and detection

Procedure:

- Sink Condition Validation:

- Determine drug solubility in selected release medium.

- Ensure medium volume is at least 3 times that required to form a saturated solution.

Release Study Setup:

- Place 500 μL of PNP suspension (or equivalent of 1-5 mg drug) into 100 mL release medium in USP apparatus II vessels.

- Maintain temperature at 37°C ± 0.5°C with paddle rotation at 50 rpm.

- At predetermined time intervals, withdraw 500 μL aliquots from each vessel.

Separation and Analysis:

- Immediately transfer aliquots to pre-rinsed centrifugal ultrafiltration devices.

- Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 10 minutes at controlled temperature (37°C).

- Collect filtrate and analyze drug concentration using validated HPLC-UV method.

- Replace medium in vessels with equal volume of fresh pre-warmed medium to maintain constant volume.

Data Processing:

- Calculate cumulative drug release using standard equations accounting for sample removal.

- Plot cumulative release versus time to generate release profiles.

- Fit data to appropriate mathematical models (e.g., zero-order, first-order, Higuchi, Korsmeyer-Peppas) to elucidate release mechanisms.

Validation Parameters:

- Separation Efficiency: Confirm >98% nanoparticle retention in ultrafiltration device using DLS analysis of retentate.

- Non-specific Binding: Demonstrate <5% drug adsorption to filtration membrane.

- Stability: Verify drug stability in release medium over experiment duration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for PNP Characterization

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Systems | PLGA, Chitosan, HPMA, Poly(lactic acid) | PNP matrix materials providing structural framework and controlling release kinetics | Select based on biodegradability, biocompatibility, and regulatory status [6] [45] |

| Stabilizers | TPGS, PVA, Poloxamers | Prevent nanoparticle aggregation during formation and storage | TPGS particularly effective for flash nanoprecipitation [44] |

| Characterization Standards | Latex/nanosphere size standards, Buffer components | Instrument calibration and method validation | Essential for data comparability across laboratories [43] |

| Separation Materials | Centrifugal filters (10-100 kDa MWCO), Dialysis membranes | Separation of free drug from nanoparticles in release studies | 100 kDa MWCO typically effective for polymeric nanoparticles [44] |

| Analytical Tools | HPLC systems, DLS instruments, TEM grids | Quantification and morphological characterization | Orthogonal approach recommended [41] [43] [44] |