Polymer Chemistry Fundamentals: From Synthesis to Advanced Drug Delivery Applications

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of polymer chemistry, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Polymer Chemistry Fundamentals: From Synthesis to Advanced Drug Delivery Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of polymer chemistry, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, including polymer structures, classification, and synthesis mechanisms. The scope extends to modern characterization techniques, troubleshooting of common issues like stability and scalability, and a comparative analysis of emerging polymer platforms such as ZIF-composites and supramolecular polymers for advanced biomedical applications, offering a complete guide from theory to practice.

Core Principles and Classifications: Building Blocks of Polymer Science

In the field of polymer chemistry, understanding the architectural relationship between monomers and polymers is a foundational principle. A monomer, derived from the Greek words "mono" (one) and "meros" (part), represents the fundamental building block of polymeric materials [1]. These simple molecules, through chemical bonding, form larger macromolecules known as polymers - from "poly" (many) and "meros" (part) [1]. This architectural hierarchy mirrors construction, where simple units (bricks) assemble into complex structures (buildings), with the specific arrangement and bonding of monomers dictating the ultimate properties and applications of the resulting polymer.

The architectural analogy extends to biological systems, where α-d-glucose monomers polymerize to form cellulose, and amino acids serve as monomers that assemble into protein copolymers through enzyme-mediated processes [2]. In synthetic contexts, the ethylene monomer forms the ubiquitous polyethylene polymer [1] [2]. This whitepaper examines the core principles defining monomers and polymers, the methodologies for their characterization, and emerging data-driven approaches that are transforming polymer research and development.

Structural Fundamentals and Nomenclature

Defining Characteristics and Classification

Table 1: Fundamental Classification of Polymers Based on Structure and Origin

| Classification Basis | Category | Key Characteristics | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | Natural Polymers (Biopolymers) | Produced by living organisms; perform biological functions | Proteins, DNA, Cellulose, Natural rubber |

| Synthetic Polymers | Engineered through chemical processes; tailored properties | Polyethylene, Polyvinyl chloride (PVC), Nylon, Teflon | |

| Molecular Structure | Linear Polymers | Chains with minimal branching; typically thermoplastic | Polyethylene, Nylon |

| Cross-linked Polymers | Networks with covalent bonds between chains; thermosetting | Vulcanized rubber, Bakelite, Epoxy resins | |

| Backbone Composition | Organic Polymers | Carbon-based backbone | Most common plastics (PVC, PET, PP) |

| Inorganic Polymers | Backbone lacking carbon | Silicones, Polysilanes | |

| Thermal Response | Thermoplastics | Soften upon heating; can be reshaped | Polypropylene, Polystyrene |

| Thermosets | Permanently set when heated; do not melt | Polyurethane, Phenol-formaldehyde resins |

Polymers exhibit tremendous diversity, classified by origin (natural vs. synthetic), molecular architecture (linear, branched, cross-linked), and thermal behavior (thermoplastics vs. thermosets) [1] [2]. Linear polymers form chains with minimal branching, typically yielding resilient, thermoplastic materials that soften when heated. In contrast, cross-linked polymers feature extensive networks where monomers connect through multiple active sites, creating rigid, thermosetting materials that decompose rather than melt upon heating [2].

The architecture of a polymer significantly influences its macroscopic properties. As Professor Frank Leibfarth notes, "Plastics are kind of cool because you can hold them in your hand, push and pull them, and you can actually feel how these molecular changes manifest into actual properties. But at the core, it all comes down to fundamental chemistry—how we make them" [3].

Systematic Nomenclature Standards

Table 2: IUPAC Nomenclature for Copolymer Architectures

| Copolymer Type | Connective | Nomenclature Example | Structural Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unspecified | -co- | poly(styrene-co-isoprene) | General copolymer without specific sequence definition |

| Statistical | -stat- | poly[isoprene-stat-(methyl methacrylate)] | Monomers follow statistical distribution patterns |

| Random | -ran- | poly[(methyl methacrylate)-ran-(butyl acrylate)] | Monomers arranged randomly along chain |

| Alternating | -alt- | poly[styrene-alt-(maleic anhydride)] | Regular alternating monomer sequence (A-B-A-B) |

| Periodic | -per- | poly[styrene-per-isoprene-per-(4-vinylpyridine)] | Repeating sequence pattern (A-B-C-A-B-C) |

| Block | -block- | poly(buta-1,3-diene)-block-poly(ethene-co-propene) | Distinct blocks of different monomers |

| Graft | -graft- | polystyrene-graft-poly(ethylene oxide) | Side chains of one monomer grafted onto backbone |

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) establishes standardized nomenclature for polymers through two primary approaches [4]. Source-based nomenclature identifies the monomer source, using the prefix "poly" followed by the monomer name in parentheses (e.g., poly(methyl methacrylate)). Structure-based nomenclature uses the "preferred constitutional repeating unit" (CRU), identified by analyzing the smallest repeating portion of the polymer chain and selecting the representation with the lowest possible locants for substituents [4].

For non-linear architectures, specific qualifiers describe complex arrangements: comb polymers feature side chains attached to a main backbone, star polymers radiate from a central core, cyclic polymers form closed loops, and network polymers create extensive three-dimensional covalent networks [4]. Standardized representation follows IUPAC graphical representation standards to ensure unambiguous communication of chemical structures [5].

Methodologies for Polymer Characterization and Analysis

Experimental Determination of Polymer Properties

Experimental Protocol 1: Determination of Hildebrand Solubility Parameter (δ) Using Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

Purpose: To determine the Hildebrand solubility parameter (δ) of polymers using Dynamic Light Scattering as an alternative to conventional techniques like Ubbelohde viscometry and swelling measurements [6].

Principle: The solubility parameter indicates the solvation behavior of polymers and their compatibility with solvents. DLS measures particle size distribution and molecular interactions in solution by analyzing fluctuations in scattered light intensity caused by Brownian motion.

Materials and Equipment:

- Polymer samples (e.g., microporous polymers PIM-1, poly(1-trimethylsilyl-1-propyne))

- Solvent series with varying solubility parameters

- Dynamic Light Scattering instrument

- Centrifuge for sample clarification

- Temperature-controlled sample chamber

Procedure:

- Prepare polymer solutions in a series of solvents with known solubility parameters.

- Clarify solutions by centrifugation to remove dust and large aggregates.

- Load samples into DLS instrument with temperature control.

- Measure diffusion coefficients of polymer chains in different solvents.

- Identify the solvent(s) where polymer exhibits minimum hydrodynamic volume and maximum stability.

- Correlate these solvent parameters to determine the polymer's solubility parameter.

Validation: Compare DLS results with traditional viscometry and group contribution methods. Research shows DLS exhibits good agreement with these established techniques while reducing time and material requirements [6].

Computational and Data-Driven Approaches

Experimental Protocol 2: High-Throughput Computational Screening of Polymer Properties

Purpose: To rapidly characterize polymer properties through computational methods, enabling efficient exploration of vast chemical space [7].

Principle: Molecular simulations at various scales (quantum, classical, mesoscopic) can predict polymer properties without resource-intensive experimental synthesis.

Materials and Software Resources:

- Polymer structure databases (e.g., Polymer Genome)

- Molecular dynamics packages (LAMMPS, GROMACS, NAMD)

- Quantum chemistry software (VASP, QUANTUM ESPRESSO, Gaussian)

- High-performance computing infrastructure with CPU/GPU clusters

Procedure:

- Featurization: Represent polymer structures in machine-readable numerical formats (fingerprints) using Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) strings, molecular graphs, or binary representations [7].

- Database Curation: Access homogeneous structure-property relation databases or generate de novo computational data.

- Molecular Simulation:

- Use quantum simulations (VASP, QUANTUM ESPRESSO) for electronic properties (band gap, dielectric constant)

- Employ classical MD (LAMMPS, GROMACS) for thermodynamic and transport properties

- Machine Learning Integration: Train models on generated data to establish structure-property relationships and predict properties for unexplored polymers.

- Experimental Validation: Select promising candidates from computational screening for targeted synthesis and testing.

Applications: This approach is particularly valuable for designing polymers for specific applications such as membranes, dielectrics, and thermally conductive materials [7].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Polymer Chemistry Investigations

| Reagent/Material Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common Monomers | Ethylene, Propylene, Styrene, Phenol, Formaldehyde, Vinyl chloride, Acetonitrile, Ethylene glycol | Building blocks for polymer synthesis; determine fundamental polymer properties | Purity critical for controlled polymerization; storage conditions vary (e.g., inhibitors for vinyl monomers) |

| Polymer Characterization Standards | Polystyrene standards with narrow dispersity, Solvent series for solubility parameter determination | Calibration of analytical instruments; method validation | Required for GPC/SEC calibration; solubility parameters should cover wide range (15-30 MPa¹/²) |

| Specialty Polymers for Advanced Applications | PIM-1 (Polymer of Intrinsic Microporosity), Poly(1-trimethylsilyl-1-propyne) | High fractional free volume materials for membrane research | Exceptional gas permeability; challenging processability |

| Computational Resources | LAMMPS, GROMACS, VASP, QUANTUM ESPRESSO | Molecular simulation at various scales | HPC environment with MPI architecture required for large systems |

| Group Contribution Parameters | Updated van der Waals volume parameters | Predicting polymer properties via group contribution methods | Mean absolute relative error of ~9.0% for solubility parameter prediction [6] |

Emerging Frontiers in Polymer Science

Data-Driven Polymer Design

The field of polymer science is undergoing a transformation through the integration of data-driven methodologies. The optimal design of polymers remains challenging due to their enormous chemical and configurational space [7]. For example, a simple linear copolymer with just two types of chemical moieties and a chain length of 50 monomers presents over 10¹⁵ possible sequences [7]. This combinatorial explosion necessitates advanced approaches beyond traditional trial-and-error methods.

Machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) are increasingly deployed to establish correlations between chemical structure and material properties [7]. These methods include fingerprinting techniques such as SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) strings and molecular graphs that represent polymers in machine-readable formats [7]. As noted in recent reviews, "the combination of machine learning, rapid computational characterization of polymers, and availability of large open-sourced homogeneous data will transform polymer research and development over the coming decades" [7].

A significant challenge in this domain is the lack of standardized, extensive databases comparable to the Protein Data Bank for biological macromolecules [7]. While such resources have accelerated biomolecular informatics, similar comprehensive databases for synthetic polymers remain sparse, heterogeneous, and often unavailable [7]. Current research focuses on addressing this limitation through computational generation of polymer property data and development of transferable predictive models.

Sustainable and Functional Polymer Systems

Contemporary polymer research increasingly emphasizes sustainability and circular economy principles. As Professor Frank Leibfarth, recipient of the 2025 Polymer Chemistry Lectureship, observes: "The biggest challenge we face is switching plastics from a linear workflow into a circular one. That requires new science, new technology and a new mindset" [3]. This perspective highlights the critical need for polymers designed not only for performance but also for recyclability and environmental compatibility.

Advanced research explores functional polymers for specialized applications including:

- MRI imaging agents capable of detecting hypoxia (low oxygen levels)

- Ultra-tough resins for 3D printing

- Microporous polymers for membrane-based separations

- High-performance composites for aerospace and medical applications [3] [6] [2]

These developments often employ innovative synthesis techniques such as continuous flow chemistry, which enables automation of polymer production and facilitates machine learning applications [3]. The integration of synthetic chemistry with computational design and automation science represents the cutting edge of polymer research, potentially enabling researchers without deep synthetic expertise to design and produce tailored polymeric materials through computational interfaces [3].

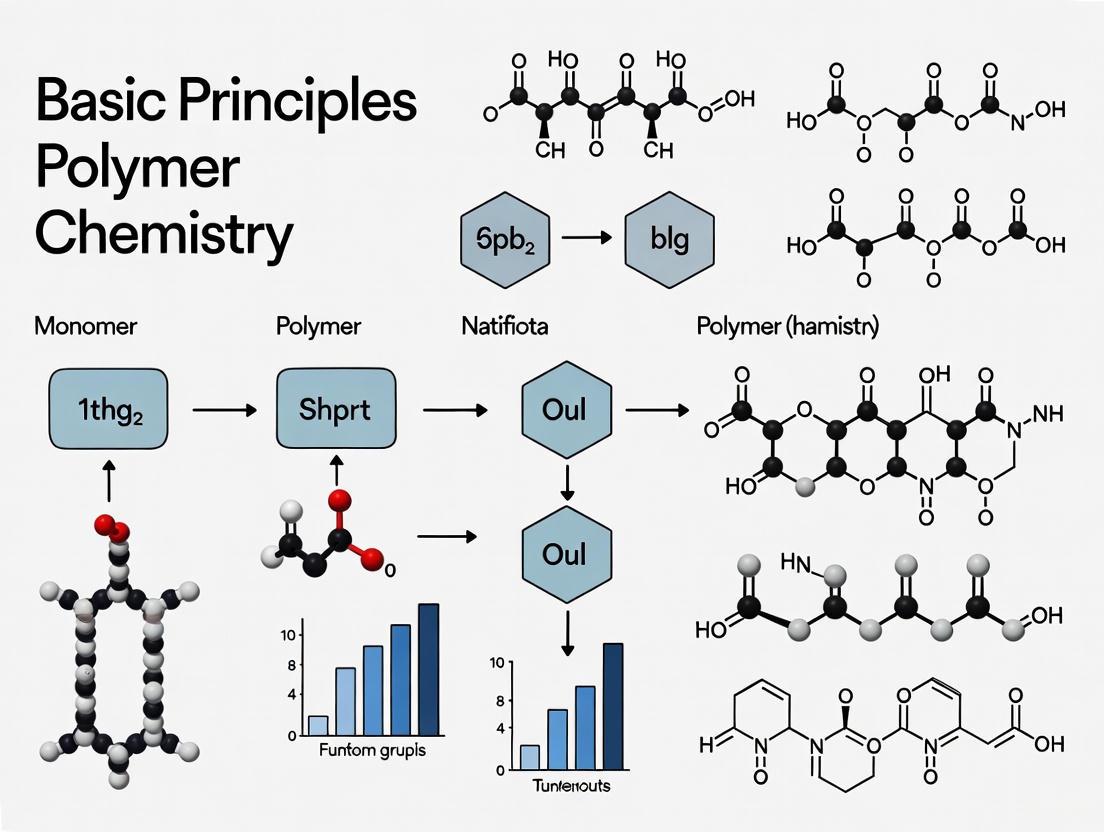

Visualizing Architectural Relationships in Macromolecular Systems

Polymerization and Structural Hierarchy: This diagram illustrates the architectural hierarchy from monomers to functional supramolecular assemblies, highlighting how simple building blocks organize into complex, functional structures through sequential processes.

Data-Driven Polymer Design Workflow: This workflow depicts the iterative process of polymer design integrating computational methods, machine learning, and experimental validation to efficiently navigate vast chemical spaces.

The architectural relationship between monomers and polymers represents a cornerstone of materials science with profound implications across biological systems and technological applications. The fundamental principle that simple molecular units can assemble into complex macromolecular structures with emergent properties continues to drive innovation in polymer science. Contemporary research increasingly leverages computational methodologies, data-driven design, and sustainable engineering principles to advance the field beyond traditional approaches.

The integration of machine learning with high-throughput computational screening and targeted experimental validation represents a paradigm shift in polymer research, potentially accelerating materials development that traditionally required 15-25 years [7]. Furthermore, the growing emphasis on circular economy principles underscores the responsibility of polymer chemists to design materials considering their entire lifecycle. As the field advances, the fundamental understanding of monomer-polymer relationships will continue to enable the creation of tailored materials with precision functionality, driving innovations in medicine, energy, electronics, and sustainable technologies.

The development of synthetic polymers represents a transformative chapter in materials science, marking a transition from reliance on naturally occurring substances to the engineered creation of materials with tailored properties. The introduction of Bakelite in 1907 by Belgian-American chemist Leo Hendrik Baekeland signaled the beginning of the "Polymer Age," establishing the fundamental principles that would guide decades of polymer chemistry research [8]. This first fully synthetic plastic demonstrated that human manufacturing was no longer constrained by the limits of nature, paving the way for the diverse array of polymeric materials that underpin modern technology, medicine, and daily life [9]. For researchers and scientists engaged in drug development and materials design, understanding this historical progression provides critical insight into the structure-property relationships that govern polymer performance and functionality.

The term "polymer," meaning "of many parts," describes large molecules comprised of long chains of repeating molecular units called monomers [9]. This architectural principle allows for extraordinary diversity in material properties—from flexible and elastic to rigid and brittle—based on molecular composition, chain length, and intermolecular interactions [10]. The evolution from Bakelite to contemporary polymers reflects increasingly sophisticated manipulation of these parameters, driven by fundamental research into polymerization mechanisms and structure-property relationships.

Historical Context and Predecessors to Bakelite

Before the advent of fully synthetic polymers, humans utilized naturally derived polymeric materials and developed semi-synthetic modifications to meet growing industrial needs. The following table summarizes key material developments that preceded and influenced Baekeland's work:

Table: Key Pre-Bakelite Polymer Developments

| Material | Date | Inventor/Developer | Key Properties & Limitations | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vulcanized Rubber | 1839 | Charles Goodyear | durable, elastic; required modification of natural rubber [10] | tires, waterproof clothing [10] |

| Parkesine | 1862 | Alexander Parkes | colorful, moldable; brittle, not commercially viable [11] | display molds, buttons, combs [10] |

| Celluloid | 1869 | John Wesley Hyatt | moldable, resembled ivory; highly flammable, thermoplastic [8] [9] | billiard balls, shirt collars, photographic film [9] [12] |

| Chardonnet Silk | 1890 | Hilaire de Chardonnet | synthetic textile fiber; derived from cellulose nitrate [8] | first synthetic textile [8] |

The driving force behind many early plastic innovations was often the scarcity and cost of natural materials. The famous $10,000 prize offered for an ivory substitute for billiard balls by Phelan and Collender in the 1860s directly stimulated Hyatt's development of celluloid [8] [12]. Similarly, Baekeland's initial research was motivated by the desire to find a synthetic substitute for shellac, a natural electrical insulator derived from lac insects that was becoming increasingly expensive and difficult to obtain in sufficient quantities for the rapidly electrifying United States [9] [13].

The Invention of Bakelite: A Paradigm Shift

Baekeland's Experimental Breakthrough

Leo Baekeland's invention of Bakelite between 1905-1907 represented a methodological and conceptual revolution in polymer science [12]. Unlike his predecessors who worked with modified natural polymers, Baekeland sought to create a completely synthetic material through the controlled reaction of phenol and formaldehyde [8]. His initial goal was to produce a soluble shellac substitute, but when this proved unsuccessful, he pivoted to creating an insoluble, infusible material that could withstand heat and solvents [13].

Baekeland's key insight was the application of precise heat and pressure control during the polymerization process. Earlier investigators like Adolf von Baeyer and Werner Kleeberg had observed the reaction between phenol and formaldehyde but dismissed the resulting resin as a laboratory nuisance that ruined equipment because it hardened into an intractable mass [8]. Baekeland systematically investigated this reaction using a sealed pressure vessel he called a "Bakelizer," which allowed him to control the condensation reaction and suppress violent foaming [13]. His laboratory notebook entry from June 18, 1907, documents the systematic approach to impregnating wood with phenol-formaldehyde mixtures and his observation of the resulting "very hard" product he initially called "Bakalite" [8].

Experimental Protocol: Synthesis of Bakelite

The synthesis of Bakelite involves a multi-stage, base- or acid-catalyzed condensation polymerization reaction. The following protocol details the methodology based on Baekeland's original process:

- Objective: To synthesize a thermosetting phenol-formaldehyde resin (Bakelite) via condensation polymerization.

- Principal Reagents & Equipment:

- Phenol (C₆H₅OH)

- Formaldehyde (CH₂O) solution (e.g., formalin)

- Catalyst (Ammonia, NaOH, or HCl)

- Heat source with temperature control (≥150°C)

- Pressure vessel ("Bakelizer")

- Mold for final shaping

- Procedure:

- Initial Condensation: Heat a mixture of phenol and formaldehyde in a molar ratio of approximately 1:1 to 1:1.5 in the presence of a basic (e.g., ammonia) or acidic (e.g., HCl) catalyst at 50-100°C. This produces a soluble, fusible liquid or low-molecular-weight solid known as Bakelite A (resol resin) [13].

- Intermediate Stage: Further heating of Bakelite A produces Bakelite B (resitol), a rubbery solid that is partially soluble and can still be softened by heat [13].

- Final Curing (Bakelizer Step): Place the Bakelite B into a strong mold or pressure vessel. Apply heat (140-160°C) and pressure (approximately 1500-2500 psi) for several hours. This final curing process creates a highly cross-linked, fully hardened, and infusible network polymer known as Bakelite C (resite) [8] [13]. The applied pressure is critical to prevent foaming and the formation of a porous, brittle product.

Diagram: Bakelite Synthesis Workflow

Key Properties and Research Impact of Bakelite

Bakelite's revolutionary properties stemmed from its thermosetting nature—once molded and cured, its cross-linked structure could not be remelted or reshaped, distinguishing it from thermoplastics like celluloid [8]. This property made it ideally suited for mass production techniques like compression molding [13].

Table: Characteristic Properties and Early Applications of Bakelite

| Property | Technical Significance | Resulting Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Thermosetting | Retained shape when heated; ideal for molding [8] | Radio cabinets, telephone housings, electrical insulators [8] [13] |

| High Electrical Resistance | Excellent electrical insulator [9] | Distributor caps, sockets, light bulb bases, support for electrical components [8] |

| Heat & Chemical Resistance | Withstood elevated temperatures and corrosive substances [8] | Automotive ignition components, appliance handles, industrial equipment [8] [12] |

| High Mechanical Strength | Durable and rigid, especially when reinforced with fillers [8] [13] | Tool handles, children's toys, mechanical parts [8] |

Baekeland secured comprehensive patent protection for his invention, filing more than 400 patents related to its manufacture and applications [8]. The formation of the General Bakelite Corporation in 1910 and the subsequent construction of large-scale production facilities marked the beginning of the modern plastics industry [8]. Bakelite was aggressively marketed as "the material of a thousand uses," a claim supported by its rapid adoption across electrical, automotive, and consumer goods industries [13].

Post-Bakelite: Proliferation of Synthetic Polymers

The commercial success of Bakelite stimulated intensive research into other synthetic polymers, first in industrial laboratories and later in academic institutions. The period between 1920 and 1970 witnessed an explosion of new polymers, each with distinct properties and applications:

Table: Major Synthetic Polymers Developed After Bakelite

| Polymer | Discovery/Commercialization Date | Key Innovator(s)/Company | Defining Characteristics | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene | 1929 (1937 commercial) | IG Farben [11] | transparent, rigid, brittle; excellent electrical insulator | packaging, disposable cutlery, insulation [11] |

| Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) | 1933 (first studied 1838-1872) [11] | – | durable, versatile; can be rigid or flexible | pipes, cable insulation, siding, medical devices [11] |

| Nylon | 1935 (1938 full scale) | Wallace Carothers (DuPont) [9] [11] | strong, tough, elastic synthetic fiber | parachutes, ropes, apparel, toothbrush bristles [9] [11] |

| Polyethylene | 1933 (1938 commercial) | Fawcett & Gibson (ICI) [11] | flexible, chemical & moisture resistant | radar insulation (WWII), squeeze bottles, bags [9] [11] |

| Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) | 1941 | Whinfield & Dickson [11] | strong, transparent gas barrier | synthetic fiber (Terylene), beverage bottles [11] |

| Polyurethane | 1949 (Lycra) [11] | DuPont [11] | versatile; can be elastomeric, rigid, or foam | foam insulation, spandex fibers, coatings [11] |

World War II acted as a massive catalyst for the plastics industry, necessitating the development of synthetic replacements for scarce natural materials [9]. Nylon replaced silk in parachutes and other military supplies, while Plexiglas (polymethyl methacrylate) provided a shatter-resistant alternative to glass in aircraft windows [9]. This period cemented the strategic importance of polymer research and established the infrastructure for the postwar plastics boom that would see plastics "challenge traditional materials and win, taking the place of steel in cars, paper and glass in packaging, and wood in furniture" [9].

The Modern Polymer Research Landscape

Contemporary polymer science has evolved far beyond the scope of early materials like Bakelite, focusing on precision synthesis, advanced functionality, and sustainability. Current research, as highlighted in special issues like "Rising Stars in Polymer Science 2025," addresses complex challenges through interdisciplinary approaches [14] [15].

Key Contemporary Research Areas

- Sustainable and Biobased Polymers: Developing polymers from renewable resources and creating chemically recyclable materials to address plastic waste. Researchers like Feng Li (Hokkaido University) focus on utilizing biomass for novel sustainable polymers and developing environmentally friendly catalytic methods [15].

- Advanced Manufacturing and Automation: Integrating flow chemistry, machine learning, and automation to achieve unprecedented control over polymer synthesis. The Leibfarth Group (UNC-Chapel Hill) uses these tools to design functional, sustainable plastics with precision, aiming to automate polymer production [3].

- High-Performance Functional Polymers: Designing polymers for specialized applications in energy, medicine, and electronics. Examples include:

- Polymer Ferroelectrics for electronics [14].

- Sustainable polymers for battery applications to improve energy storage [14].

- Conjugated polymers for stretchable, miniaturized organic electronics, as researched by Chien-Chung Shih (NYUST) [15].

- Implantable biomaterials like PEEK for neurological applications and 3D-printed body parts [11].

- Smart and Responsive Materials: Creating polymers that respond to external stimuli (e.g., ultrasound, light, pH). Reika Katsumata (UMass Amherst) develops reprocessable crosslinked polymers through ultrasound-mediated bond-exchange reactions, enabling healing and recycling of thermosets [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Modern polymer research relies on a sophisticated toolkit of reagents, catalysts, and analytical techniques to design and characterize new materials.

Table: Key Research Reagents and Materials in Modern Polymer Science

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization (ROMP) Catalysts | Complex metal catalysts (e.g., Grubbs' catalyst) that enable the polymerization of cyclic olefins via metathesis [14]. | Synthesis of precision polymers with complex architectures and functional groups [14]. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Synthetic polymers with template-shaped cavities for specific molecular recognition, acting as "synthetic antibodies" [16]. | Selective extraction and sensing of analytes in environmental, food, and biological samples [16]. |

| Sol-Gel Derived Advanced Materials | Hybrid organic-inorganic materials formed via sol-gel chemistry, offering high surface area and tunable porosity [16]. | Stationary phases for chromatography, coating for microextraction sorbents, and functional nanoparticles [16]. |

| Ionic Monomers | Monomers bearing ionic groups used to create poly(ionic liquid)s and other charged polymers [15]. | Developing polymers with unique rheological properties, ionic conductivity, and responsiveness for energy and sensor applications [15]. |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Computational tools used to model structure-property relationships and predict polymerization outcomes [14] [3]. | Accelerating the design of new polymers with targeted properties, such as ultra-tough 3D printing resins [3]. |

Diagram: Modern Polymer Design and Development Cycle

The journey from Bakelite to modern synthetic polymers illustrates a fundamental shift in materials science—from empirical discovery to rational, molecular-level design. Baekeland's achievement was monumental, demonstrating that entirely new materials could be created synthetically. However, his understanding of the molecular structure of his creation was limited [12]. Today, polymer chemists operate with a deep understanding of polymer physics and structure-property relationships, enabling them to design materials with exquisite precision for applications ranging from sustainable packaging to targeted drug delivery and advanced electronics.

The future of polymer science, as evidenced by current research trends, lies in addressing the dual challenges of performance and sustainability. The field is moving toward a circular economy model, necessitating the development of polymers that are not only functional but also recyclable, biodegradable, or derived from renewable resources [3]. The integration of tools from adjacent fields—such as machine learning for predictive design, continuous flow chemistry for precise control, and advanced analytics for characterization—ensures that polymer science will continue to be a dynamic and innovative discipline, building upon the foundation laid by Baekeland over a century ago to create the advanced materials of the future.

Polymers, large molecules composed of repeating monomeric subunits, constitute a fundamental pillar of materials science and chemical research. Their classification by origin—natural, synthetic, and semi-synthetic—provides a critical framework for understanding their properties, applications, and development trajectories. This classification system is not merely descriptive; it directly informs the strategic design of new materials with tailored functionalities for advanced applications, particularly in biomedicine and sustainable technology [17] [18].

The ongoing evolution in polymer science is marked by a strategic convergence of these classes. Researchers are increasingly focusing on hybrid materials that combine the advantages of natural and synthetic polymers to overcome their individual limitations. This paradigm shift is driven by contemporary challenges, including the need for sustainable materials and advanced drug delivery systems, setting the context for a deeper exploration of each category's defining characteristics and synergistic potential [19] [3] [18].

Fundamental Classification and Defining Characteristics

Natural polymers are produced by living organisms—plants, animals, or microorganisms—and are integral to biological structures and functions. They typically feature complex structures that have been optimized through natural selection for specific biological roles. Common examples include cellulose (from plants), proteins like collagen and silk (from animals), and natural rubber (from the Hevea brasiliensis tree) [17] [18]. These materials often require extraction and purification processes before they can be utilized in industrial or biomedical applications [17].

Synthetic polymers are human-made, created in laboratory or industrial settings through controlled chemical reactions that polymerize monomers derived predominantly from petrochemical sources. This origin allows for a high degree of customization. Examples such as polyethylene (PE), nylon, and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) showcase the vast range of properties achievable through synthetic design. Their structures can be precisely engineered to mimic or even surpass the properties of natural polymers [17].

Semi-synthetic polymers (also termed bioartificial or biosynthetic polymers) occupy the strategic middle ground. This class is created by chemically modifying natural polymers or by creating covalent linkages or blends between natural and synthetic polymers. The goal is to produce a new class of materials that combines the desirable properties of both parents, such as the biocompatibility of a natural polymer with the mechanical strength and processability of a synthetic one. Examples include modified cellulose (like cellulose acetate) and various collagen-synthetic polymer hybrids [19] [18].

Comparative Analysis of Key Properties

The table below summarizes the fundamental characteristics of the three polymer classes, highlighting their comparative advantages and limitations.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Polymer Classes Based on Origin

| Characteristic | Natural Polymers | Synthetic Polymers | Semi-Synthetic Polymers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | Plants, animals, microorganisms [17] | Chemical synthesis (e.g., from petrochemicals) [17] | Chemical modification of natural polymers or their blends with synthetics [19] [18] |

| Biocompatibility | Typically high [18] | Variable; can contain residual initiators or impurities that hinder cell growth [18] | Designed to be high, combining natural biocompatibility with controlled synthesis [18] |

| Biodegradability | Typically high [19] [18] | Variable; many are non-biodegradable and persist in the environment [3] | Can be engineered for specific degradation profiles [19] |

| Mechanical & Thermal Properties | Often limited; can be structurally weak and lack thermal stability [18] | Generally excellent, highly customizable, and reproducible [19] [18] | Improved and tunable; aims to surpass natural polymer limitations [19] [18] |

| Processability | Can be challenging; high temperatures may destroy native structure [18] | Excellent; can be processed into a wide range of shapes and forms [17] [18] | Enhanced; improved processability compared to natural polymers alone [18] |

| Architectural Control & Reproducibility | Fixed, complex structures; batch-to-batch variation possible [17] | High degree of control over molecular weight, structure, and composition; highly reproducible [19] [17] | Good control, though influenced by the natural polymer component [19] |

| Example Applications | Wood, paper, cotton, silk, biological scaffolds [17] [18] | Plastics, fibers, elastomers, commodity packaging [17] [3] | Advanced drug delivery systems, functionalized biomaterials, sustainable plastics [19] [3] |

Structural and Thermal Considerations in Polymer Design

Beyond origin, a polymer's physical properties are profoundly influenced by its molecular architecture and thermal behavior. These factors are critical for researchers selecting or designing a polymer for a specific application.

Polymer Architectures

- Linear Polymers: Monomers are connected end-to-end in a single continuous chain. These chains can pack closely together, resulting in materials with high density, crystallinity, and tensile strength. A classic example is high-density polyethylene (HDPE) [17].

- Branched Polymers: The main polymer chain has side chains or branches extending from it. These branches disrupt the close packing of chains, leading to lower density, lower crystallinity, and increased flexibility. Low-density polyethylene (LDPE) is a common branched polymer [17].

- Cross-Linked Polymers: Chains are connected by covalent bonds, forming a three-dimensional network. This structure restricts chain movement, resulting in high mechanical strength, thermal stability, and insolubility. Once formed, these materials cannot be re-melted and reshaped. Vulcanized rubber and epoxy resins are cross-linked polymers [17].

Thermal Classifications

The relationship between polymer structure and thermal response defines two key classifications:

- Thermoplastics: These polymers, which are typically linear or branched, soften upon heating and harden upon cooling in a reversible process. This property allows them to be reshaped and recycled. Their behavior is characterized by the glass transition temperature ($Tg$), where the polymer transitions from a glassy to a rubbery state, and the melting temperature ($Tm$), where crystalline regions melt [17].

- Thermosets: These polymers are cross-linked into a permanent network during a curing process (often initiated by heat or light). After curing, they cannot be re-melted or reshaped, as the cross-links are irreversible. They exhibit high mechanical strength and thermal stability but cannot be recycled by conventional means. Epoxy resins and polyurethanes are thermosets [17].

Experimental Focus: Methodologies for Advanced Polymer Synthesis and Blending

Preparation of Semisynthetic Polymer Blends for Biomaterials

Objective: To create a novel biomaterial blend of a natural polymer (e.g., chitosan or collagen) with a synthetic polymer (e.g., PVA) that exhibits enhanced mechanical properties and biocompatibility for potential drug delivery or tissue engineering applications [18].

Materials and Solvent Considerations:

- Natural Polymer Selection: Collagen (soluble in dilute acetic acid) or Chitosan (soluble in dilute acetic acid, with solubility dependent on its molecular weight and degree of deacetylation) [18].

- Synthetic Polymer Selection: A water-soluble synthetic polymer like Poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) or Poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) is chosen to enable blending in a common solvent [19] [18].

- Solvent System: Dilute aqueous acetic acid (typically 0.1-1 M) is a common solvent for collagen and chitosan. The concentration must be optimized to dissolve both components without degrading the natural polymer's native structure [18].

Protocol:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare separate solutions of the natural and synthetic polymers in the common solvent (e.g., 1% w/v chitosan and 2% w/v PVA in 0.5 M acetic acid). Stir gently until complete dissolution is achieved.

- Blending: Combine the two polymer solutions in a desired mass ratio (e.g., 50:50 chitosan:PVA) under constant mechanical stirring at room temperature for several hours to ensure a homogeneous mixture.

- Film Casting/Scaffold Formation:

- For Films: Pour the homogeneous blend solution into a Petri dish and allow the solvent to evaporate slowly at a controlled temperature (e.g., 37°C) over 24-48 hours.

- For Porous Scaffolds: Utilize techniques like freeze-drying (lyophilization), where the blend solution is rapidly frozen and then placed under vacuum to sublime the ice crystals, creating a porous structure [18].

- Post-Processing: Neutralize the resulting film or scaffold in an alkaline solution (e.g., NaOH/ethanol mixture) to remove residual acetic acid and improve stability. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and air-dry.

Characterization: The resulting blend material should be characterized for its mechanical properties (tensile testing), morphology (scanning electron microscopy), chemical structure (Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy), and biocompatibility (cell culture assays) [18].

Advanced Synthesis: Flow Chemistry for Precision Polymers

Objective: To synthesize synthetic polymers with extraordinary precision and control over molecular weight and architecture using automated flow chemistry techniques, enabling high-throughput screening and machine-learning-driven design [3].

Principle: Flow chemistry, unlike traditional batch synthesis, involves pumping reagents continuously through tubular reactors. This allows for superior control over reaction parameters like temperature and mixing, leading to more reproducible and scalable polymer synthesis [3].

Protocol:

- System Setup: Configure a flow chemistry system consisting of reagent reservoirs, precision pumps, a temperature-controlled tubular reactor (often a coil), and a collection vessel.

- Monomer and Initiator Preparation: Prepare solutions of the monomer(s) and initiator in an appropriate solvent. Degas the solutions to remove oxygen, which can inhibit many polymerization reactions.

- Continuous Polymerization: Use the pumps to introduce the monomer and initiator streams at a controlled, fixed flow rate into the reactor. The residence time in the reactor (and thus the polymer chain length) is determined by the flow rate and reactor volume.

- Quenching and Collection: The polymer solution exiting the reactor is collected in a vessel containing a quenching agent to terminate the reaction.

- Purification: The polymer is typically isolated by precipitation into a non-solvent, followed by filtration or centrifugation, and then dried.

This methodology is at the forefront of modern polymer science, facilitating the discovery of new functional and sustainable plastics [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Polymer Synthesis and Blending

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Chitosan | A natural cationic biopolymer used for its biocompatibility, biodegradability, and inherent antibacterial properties. Often blended with synthetics to create wound dressings and drug delivery carriers [19] [18]. |

| Collagen | The most abundant animal protein. Used as a natural polymer component in blends to enhance cell adhesion and biocompatibility in tissue engineering scaffolds [18]. |

| Poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) | A water-soluble synthetic polymer frequently blended with natural polymers to improve the mechanical strength and flexibility of the resulting bioartificial material [19] [18]. |

| Poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) | A water-soluble, biocompatible synthetic polymer used in blends to modify viscosity, enhance drug release profiles, and improve processability [19]. |

| Dilute Acetic Acid | A common solvent for dissolving natural polymers like chitosan and collagen, enabling their processing and blending with other water-soluble polymers [18]. |

| Cross-linking Agents | Chemicals (e.g., genipin, glutaraldehyde) used to create covalent bonds between polymer chains, increasing the mechanical strength and stability of both synthetic and semi-synthetic networks [18]. |

Research Workflow and Future Directions

The strategic development of new polymeric materials follows a logical pathway from concept to application, driven by specific design goals. This workflow is increasingly informed by principles of sustainability and circularity.

Diagram 1: Polymer research workflow from design to application.

The future of polymer science, as illustrated in the workflow, is oriented toward overcoming current limitations. A major focus is on sustainable and circular design, moving away from a "take-make-waste" model. Researchers like Frank Leibfarth are pioneering the use of automated synthesis and machine learning to design polymers from the bottom up for both performance and recyclability [3]. In biomedicine, the trend is moving beyond simple delivery systems toward complex, co-delivery synergetic platforms and smart, condition-responsive releases, where semi-synthetic polymers play a crucial role due to their tunable properties [19]. The continued functionalization of semisynthetic polymers promises even greater control over release kinetics and material interactions within biological systems, paving the way for next-generation therapies and smart materials [19].

The fundamental properties of polymeric materials are dictated by their underlying architectural design. While the chemical composition is critical, the spatial arrangement of polymer chains into specific structural configurations—linear, branched, and cross-linked networks—ultimately determines key characteristics such as mechanical strength, solubility, thermal processability, and application potential [20]. Within the broader thesis on basic principles of polymer chemistry research, understanding these configurations provides the foundational knowledge required to design novel materials with tailored properties for advanced applications, including drug delivery systems, biomedical devices, and sustainable materials [21]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these core structures, their synthesis, characterization, and structure-property relationships, serving as an essential resource for researchers and scientists engaged in polymer-related research and development.

Fundamental Polymer Architectures

Linear Polymers

Linear polymers consist of a single continuous backbone chain with no branches or crosslinks, resembling long strands of spaghetti [20]. The long chains are typically held together by weaker intermolecular forces such as van der Waals forces or hydrogen bonding [20]. These physical bonds are relatively easy to break with heat, allowing the chains to flow past each other, which makes linear polymers typically thermoplastic [20]. This means they soften upon heating, can be reshaped, and harden upon cooling, enabling processing through methods like injection molding and extrusion [20] [22]. The geometry around each carbon atom in a carbon-chain polymer is tetrahedral, causing the chain to fold back on itself in a random fashion rather than being truly linear or straight [22]. Examples include high-density polyethylene (HDPE), polypropylene, and nylon [23].

Branched Polymers

Branched polymers feature a main backbone chain with shorter side chains hanging from it [20]. These branches can vary in length and complexity, including short-chain branching, long-chain branching, star polymers, and comb polymers [23]. The presence of branches interferes with efficient packing of the polymer chains, resulting in materials that are less dense than their linear counterparts [20]. Like linear polymers, most branched polymers are thermoplastic, as heat typically breaks the bonds between chains [20]. However, some complex branched structures may resist melting and degrade before softening, exhibiting thermosetting behavior [20]. A common example is low-density polyethylene (LDPE), where branches reduce crystallinity and density compared to HDPE [23] [22].

Cross-linked and Network Polymers

Cross-linked polymers resemble ladders, with covalent bonds connecting one polymer backbone to another [20]. Unlike the weak physical bonds in linear and branched polymers, these covalent cross-links create a much stronger interconnected structure [20]. This bonding makes most cross-linked polymers thermosetting, meaning they do not soften upon heating but instead maintain their shape until they eventually degrade [20]. A subset of cross-linked polymers, known as network polymers, are heavily linked to form a complex three-dimensional network [20]. These materials are nearly impossible to soften without degrading the polymer structure and are thus always thermosetting [20]. The extent of cross-linking significantly impacts properties; for instance, lightly cross-linked polymers can be elastic (elastomers), while heavily cross-linked networks are rigid and robust (thermosets) [22] [21]. Examples include vulcanized rubber, epoxy resins, and phenol-formaldehyde resins [23] [21].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Polymer Structural Configurations

| Characteristic | Linear Polymers | Branched Polymers | Cross-linked Polymers | Network Polymers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure | Single backbone, no branches [20] | Main backbone with secondary side chains [20] | Chains linked via covalent bonds (ladder-like) [20] | Extensive 3D network of covalent linkages [20] |

| Intermolecular Forces | van der Waals, Hydrogen bonding [20] | van der Waals, Hydrogen bonding [20] | Covalent bonding [20] | Covalent bonding [20] |

| Solubility | Soluble in suitable solvents [22] | Often soluble [22] | Insoluble [22] | Insoluble [22] |

| Thermal Behavior | Thermoplastic [20] | Mostly Thermoplastic [20] | Mostly Thermosetting [20] | Thermosetting [20] |

| Primary Properties | Can be crystalline or semi-crystalline, moldable [22] | Lower density, reduced crystallinity [20] | Enhanced strength, elasticity, solvent resistance [23] | High rigidity, thermal stability, insolubility [20] |

| Examples | HDPE, Nylon, Polypropylene [23] | LDPE [23] | Vulcanized Rubber, PEX [23] | Epoxy, Phenol-formaldehyde resins [23] |

Synthesis and Experimental Protocols

Synthesis of Linear and Branched Polymers

Linear polymers are typically synthesized through polymerization reactions involving bifunctional monomers. In chain-growth polymerization (e.g., of ethylene), a catalyst initiates the reaction, causing monomers to add rapidly to a growing chain with active sites [22]. In step-growth polymerization (e.g., for nylon), monomers with two reactive end groups react with each other, gradually building molecular weight through the formation of dimers, trimers, and longer chains [22]. The purity of monomers and precise control of reaction conditions (temperature, catalyst concentration, and solvent) are critical for achieving high molecular weight linear polymers with minimal branching.

Branched polymers can be synthesized via several methods. Chain transfer to polymer during free-radical polymerization can generate random branches [23]. Copolymerization with a branching comonomer (e.g., using a small amount of divinylbenzene in a vinyl polymerization) introduces branch points directly into the polymer backbone [23]. Grafting techniques involve creating active sites on a pre-formed linear polymer backbone and then using these sites to initiate the polymerization of a second monomer, forming the branches [20] [23]. The branching density and branch length are controlled by the concentration of the branching agent or the intensity of the grafting initiation conditions.

Synthesis of Cross-linked and Network Polymers

The synthesis of cross-linked polymers involves creating permanent covalent bonds between polymer chains. This can be achieved through two primary strategies:

- Copolymerization with Multifunctional Monomers: This one-pot method involves polymerizing a mixture of monofunctional and multifunctional monomers (e.g., divinylbenzene, ethylene glycol dimethacrylate) [23] [21]. The multifunctional monomers act as cross-linkers, connecting growing polymer chains into a network. The cross-link density is controlled by the molar ratio of the multifunctional monomer.

- Post-Polymerization Cross-linking: In this two-step approach, linear or branched polymers with reactive pendant or terminal groups are first synthesized [23] [21]. These reactive polymers are then treated with a cross-linking agent in a separate step. A classic example is the vulcanization of rubber, where polyisoprene chains are cross-linked with sulfur bridges [22]. Other cross-linking methods include using radiation (electron beam, UV) or heat, often in the presence of a chemical initiator [23].

Table 2: Key Reagents for Polymer Synthesis and Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Divinylbenzene | A common multifunctional monomer used as a cross-linker in copolymerization reactions to form polymer networks [23]. |

| Initiators (e.g., AIBN, Peroxides) | Compounds that generate free radicals upon heating or UV exposure to initiate chain-growth polymerizations [21]. |

| Sulfur & Accelerators | The cross-linking agent system for the vulcanization of rubber (polyisoprene) to create elastomers [22]. |

| Solvents (Toluene, THF, DMF) | Used to dissolve reactants for synthesis, to purify linear/branched polymers via precipitation, and for swelling studies of networks [22] [21]. |

| Deuterated Solvents (CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆) | Essential for nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to characterize polymer structure and composition without interfering solvent signals [24]. |

| FT-IR Spectrometer | Instrument used to identify and quantify functional groups in a polymer, and to monitor the progress of cross-linking reactions [21]. |

Figure 1: Polymer synthesis pathways from monomers to different architectures.

Characterization Methodologies

Characterizing polymers, especially cross-linked networks, presents unique challenges due to insolubility. A combination of techniques is required to fully understand their structure and properties.

Solubility and Swelling Tests

A primary method to distinguish between polymer structures is their behavior in solvents. Linear and branched polymers are typically soluble in one or more solvents because the weaker intermolecular forces between chains can be disrupted by solvent molecules [22]. In contrast, cross-linked polymers are insoluble in all solvents because the polymer chains are tied together by strong covalent bonds that cannot be broken by solvents [22]. Instead of dissolving, cross-linked polymers swell as solvent molecules penetrate the network and push the chains apart. The equilibrium swelling ratio can be used to calculate the molar mass between crosslinks (Mc), a critical parameter defining network density [21]. The experimental protocol involves:

- Precisely weighing a dry polymer sample (W₀).

- Immersing it in a suitable solvent until equilibrium swelling is reached (typically 24-48 hours).

- Carefully removing the sample, blotting excess solvent, and weighing again (Wₛ).

- Calculating the swelling ratio as Q = Wₛ / W₀.

- Using the Flory-Rehner equation, which incorporates the polymer-solvent interaction parameter (χ) and the cross-link density, to compute Mc [21].

Thermal Analysis

Thermal analysis reveals how polymer structure influences thermal transitions and processability.

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): DSC measures thermal transitions such as the glass transition temperature (Tg) and the melting temperature (Tm). Linear and branched polymers exhibit clear Tg and, if crystalline, Tm. Cross-linking restricts chain mobility, which generally increases the Tg [23]. Highly cross-linked networks may not show a melting endotherm as they are amorphous and cannot flow [21].

- Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA): TGA measures weight loss as a function of temperature, providing information about thermal stability and decomposition. Cross-linked networks often exhibit higher thermal decomposition temperatures due to their robust covalent structure [21].

Spectroscopic and Mechanical Characterization

- Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy: FT-IR is used to identify chemical functional groups and monitor the consumption of reactive groups (e.g., C=C bonds) during cross-linking [21]. For insoluble networks, Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) accessories allow for direct analysis of solid samples.

- Mechanical Testing: The mechanical properties are profoundly affected by structure. Tensile testing measures strength and elongation. Linear/branched thermoplastics can be tough but may creep under load. Cross-linked polymers exhibit higher strength and elasticity, with properties varying with cross-link density: low cross-link density produces elastomers, while high density produces rigid thermosets [23] [22]. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) is particularly powerful for probing the viscoelastic behavior and Tg of polymer networks [21].

Table 3: Characterization Techniques for Polymer Structures

| Technique | Primary Information | Application to Linear/Branched | Application to Cross-linked/Network |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solubility/Swelling | Distinguishes thermoplastic vs. thermoset behavior [22] | Soluble in suitable solvents [22] | Insoluble, but swells in solvents; swelling degree indicates cross-link density [21] |

| Gel Fraction | Quantifies the insoluble, cross-linked fraction [21] | Not typically applicable (soluble) | Critical metric; calculated from the mass of the insoluble gel after solvent extraction [21] |

| DSC | Glass transition (Tg) and melting (Tm) temperatures [21] | Reveals Tg and Tm, related to processability | Reveals increased Tg; melting endotherm is often absent [23] |

| TGA | Thermal stability and decomposition profile [21] | Determines degradation onset temperature | Often shows higher thermal stability and char yield [21] |

| FT-IR | Chemical functionality, cross-linking progress [21] | Identifies functional groups in the polymer | Tracks disappearance of cross-linker functional groups (e.g., C=C) [21] |

| Tensile Test | Mechanical strength, elasticity, elongation [21] | Properties vary with crystallinity and Mw | Higher strength and elasticity; properties depend on cross-link density [22] |

Figure 2: Decision workflow for characterizing polymer architectures based on solubility.

The strategic design of polymer materials for advanced applications hinges on a fundamental understanding of structural configurations. Linear polymers offer processability, branched polymers provide lower density and specific melt properties, while cross-linked and network polymers deliver enhanced mechanical strength, thermal stability, and solvent resistance. The choice of architecture is a direct response to application requirements, guided by established synthesis protocols and characterized by a suite of analytical techniques. As polymer science continues to evolve, particularly with the emergence of dynamic networks and bio-based feedstocks, these core principles of structure-property relationships will remain the foundation for innovation in fields ranging from drug development and biomedical engineering to sustainable materials science.

Polymerization is a fundamental chemical process in which small molecules, known as monomers, covalently bond to form large chain-like or network molecules called polymers [25] [26]. These macromolecules are the primary components of plastics and numerous other materials that define modern technology and daily life [26]. The structure-property relationships inherent to polymers dictate their mechanical, thermal, and chemical resistance profiles, making an understanding of their formation crucial for materials scientists and researchers [27]. Within polymer chemistry, two primary mechanisms form the basis for synthesizing most polymeric materials: addition (chain-growth) polymerization and condensation (step-growth) polymerization [25] [28]. This whitepaper, framed within a broader thesis on the basic principles of polymer chemistry research, provides an in-depth technical examination of these core mechanisms, their experimental protocols, and their distinctive characteristics.

Addition Polymerization

Mechanism and Key Characteristics

Addition polymerization, also referred to as chain-growth polymerization, involves the sequential addition of monomer molecules to a growing polymer chain through the rearrangement of double or triple bonds without the loss of any atoms or molecules [25] [29] [28]. This process is characterized by its chain-reaction nature, which proceeds through three distinct stages: initiation, propagation, and termination [26] [28].

A critical requirement for addition polymerization is that the monomer must possess a carbon-carbon double bond, as seen in ethylene and its derivatives (vinyl monomers) [26] [30]. The reaction is typically exothermic and results in polymers with high molecular weights rapidly forming after initiation [25]. The molecular weight of the final polymer equals the sum of the molecular weights of all incorporated monomers [28].

Figure 1: The three fundamental steps of addition polymerization: initiation, propagation, and termination.

Experimental Protocol for Free Radical Polymerization

Free radical polymerization is a common form of addition polymerization. The following provides a generalized protocol suitable for the synthesis of polymers like polystyrene.

Objective: To synthesize polystyrene via free radical addition polymerization of styrene monomer. Principle: The double bond of the styrene monomer is activated by a free radical initiator. This initiated monomer then adds to other monomer molecules in a chain-propagating reaction until termination [26] [28].

Materials and Equipment:

- Monomer: Styrene (requires purification to remove inhibitors, typically by passing through an alumina column).

- Initiator: Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN), recrystallized from methanol.

- Reactor: Schlenk flask or a glass reactor with a stir bar.

- Inert Atmosphere: Nitrogen or argon gas supply.

- Heating Bath: Thermostatic oil or heating bath capable of maintaining 60-70°C.

Procedure:

- Purification: Purify the styrene monomer. Weigh the required amount of AIBN (typical concentration is 0.1-1 mol% relative to monomer).

- Reactor Setup: Charge the styrene and AIBN into the Schlenk flask. Seal the flask with a rubber septum.

- Oxygen Removal: Attach the flask to a vacuum/nitrogen line. Perform a minimum of three freeze-pump-thaw cycles to remove dissolved oxygen, which acts as an inhibitor. Under a positive pressure of nitrogen, seal the flask.

- Polymerization: Immerse the flask in a heating bath set at 60-70°C with constant stirring. The reaction will typically proceed for 4-24 hours, during which the solution will become viscous.

- Termination & Isolation: Terminate the reaction by rapidly cooling the flask and exposing the contents to air. Precipitate the polymer into a large excess of vigorously stirred methanol. Filter the resulting white solid and dry it under vacuum at 40°C to constant weight.

Key Considerations:

- Safety: Conduct all operations behind a safety shield, especially during the initiation step. Handle monomers and initiators with appropriate personal protective equipment.

- Characterization: The final polymer can be characterized by Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) for molecular weight distribution, and NMR or FTIR for structural analysis.

Condensation Polymerization

Mechanism and Key Characteristics

Condensation polymerization, or step-growth polymerization, proceeds through the stepwise reaction between molecules containing two or more condensable functional groups [25] [31]. Each reaction step produces a distinct, stable molecule and is typically accompanied by the elimination of a small molecule by-product such as water, methanol, or HCl [29] [32].

Unlike addition polymerization, monomers for condensation reactions must possess two or more functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl, carboxyl, or amine groups) [31]. Common examples include the formation of polyamides (e.g., nylon) from a diamine and a diacid, and polyesters (e.g., PET) from a diol and a diacid [30] [31]. The reaction is generally endothermic and the polymers formed are often more susceptible to hydrolytic degradation due to the nature of the inter-unit linkages [25]. The molecular weight of the polymer increases slowly throughout the reaction, and high conversions are required to achieve high molecular weights [32].

Figure 2: The step-growth mechanism of condensation polymerization, showing the formation of a by-product at each linkage.

Experimental Protocol for Nylon-6,6 Synthesis

Objective: To synthesize the polyamide Nylon-6,6 via the condensation polymerization of hexamethylene-diamine and adipic acid. Principle: The amine groups of the diamine react with the carboxyl groups of the diacid to form amide linkages, with the elimination of water [30] [31].

Materials and Equipment:

- Monomer A: Adipic acid.

- Monomer B: Hexamethylene-diamine.

- Solvent: A 50/50 (v/v) mixture of water and ethanol.

- Nylon Salt: Pre-formed by neutralizing the diacid and diamine in a 1:1 molar ratio.

- Reactor: A three-necked round-bottom flask equipped with a mechanical stirrer, nitrogen inlet, and a distillation head or condenser.

- Inert Atmosphere: Nitrogen gas supply.

- Heating Mantle: With temperature control.

Procedure (Interfacial & Melt Polycondensation):

A. Nylon Salt Formation:

- Dissolve equimolar amounts of adipic acid and hexamethylene-diamine in the hot ethanol/water solvent.

- Cool the solution to allow the precipitation of the 1:1 salt. Filter and dry the salt thoroughly. This ensures exact stoichiometry.

B. Melt Polycondensation:

- Reactor Charging: Place the dry nylon salt in the three-necked flask.

- Oxygen Removal: Flush the flask with nitrogen and maintain a slight positive pressure of inert gas throughout the reaction.

- Polymerization: Heat the flask rapidly to 210°C and hold for 1-2 hours while allowing water to distill off. Then, gradually increase the temperature to 270-280°C under a vacuum (< 1 mmHg) for 1-2 hours to drive the reaction to completion and remove the last traces of water.

- Isolation: After cooling under nitrogen, the solid polymer melt can be broken up and isolated.

Key Considerations:

- Stoichiometry: Precise 1:1 molar ratio of functional groups is critical for achieving high molecular weight. The use of pre-formed salt ensures this.

- By-product Removal: Efficient removal of the water by-product, especially in the final stages under vacuum, is essential to shift the equilibrium towards polymer formation.

- Characterization: The final polymer can be characterized by its melting point, inherent viscosity, and FTIR spectroscopy to confirm the amide linkage.

Comparative Analysis

The fundamental differences between addition and condensation polymerization mechanisms lead to distinct polymer properties and processing requirements. The following table provides a structured quantitative and qualitative comparison to guide material selection and process design in research and development.

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of addition and condensation polymerization mechanisms.

| Characteristic | Addition Polymerization | Condensation Polymerization |

|---|---|---|

| Required Monomer Structure | Double or triple bonds (e.g., vinyl monomers) [29] [28] | Two or more functional groups (e.g., -OH, -COOH, -NH₂) [29] [31] |

| Reaction By-products | None [29] [28] | Yes (e.g., H₂O, CH₃OH, HCl, NH₃) [29] [31] |

| Molecular Weight Relationship | Polymer MW = n × (Monomer MW) [29] | Polymer MW < n × (Monomer MW) due to by-product loss [29] |

| Growth Mechanism | Chain-growth (rapid addition to active chain) [26] [28] | Step-growth (slow reaction between any two molecules) [32] [31] |

| Reaction Kinetics | Fast, exothermic [25] | Slower, often endothermic and equilibrium-limited [25] [28] |

| Catalysts/Initiators | Radical initiators, Lewis acids/bases, Ziegler-Natta catalysts [29] [28] | Specific acid/base catalysts for the functional group reaction [29] |

| Typical Polymers Formed | Polyethylene, Polypropylene, PVC, Polystyrene [25] [26] | Polyesters (PET), Polyamides (Nylon), Polycarbonates [25] [31] |

| Susceptibility to Degradation | Chemically inert due to strong C-C bonds [25] | Susceptible to hydrolysis, especially at elevated temperatures [25] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful polymerization research requires careful selection of reagents and materials. The following table details key components used in the featured experimental protocols and their critical functions.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for polymerization studies.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Polymerization | Example in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) | Free radical initiator; decomposes thermally to generate radicals that initiate chain growth [28]. | Addition polymerization of styrene [28]. |

| Purified Monomer (e.g., Styrene) | The primary building block of the polymer; requires purification to remove inhibitors (e.g., hydroquinone) that prevent premature polymerization [26]. | Addition polymerization of styrene [26]. |

| Nylon Salt (1:1 Hexamethylene-diamine/Adipic Acid) | Ensures strict 1:1 stoichiometry of functional groups, which is critical for achieving high molecular weight in step-growth polymerization [32]. | Condensation polymerization of Nylon-6,6 [31]. |

| Inert Gas (N₂ or Ar) | Creates an oxygen-free atmosphere; oxygen is a radical scavenger that inhibits addition polymerization and can cause oxidative degradation [28]. | Used in both addition and condensation protocols [28]. |

Addition and condensation polymerizations represent two fundamentally distinct pathways for macromolecular synthesis, each with defined mechanisms, monomer requirements, and resulting polymer characteristics. Addition polymerization, a chain-growth process involving unsaturated monomers, yields non-degradable polymers like polyethylene and polystyrene. In contrast, condensation polymerization, a step-growth process involving polyfunctional monomers with the expulsion of small molecules, produces materials like nylons and polyesters, which often display different chemical reactivity. The choice of mechanism profoundly impacts the thermal stability, chemical resistance, and mechanical performance of the final material [25]. A deep and practical understanding of these core principles is indispensable for researchers and scientists engaged in the design, synthesis, and application of polymeric materials, forming the foundation for innovation in polymer chemistry and related fields such as drug delivery and materials science.

Synthesis, Characterization, and Biomedical Implementation

The pursuit of advanced polymerization techniques is a cornerstone of modern polymer chemistry research, driven by the need for precise architectural control and performance under industrially relevant conditions. A fundamental challenge in this field lies in the development of catalytic complexes that maintain their structural integrity and activity at high temperatures, particularly for processes like the synthesis of polyolefin elastomers (POEs) where solution polymerization often exceeds 120 °C. Traditional metallocene catalysts, while revolutionary, frequently suffer from thermally induced molecular weight depression, compromising the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of industrial production [33]. This technical guide examines the core principles of high-temperature stabilization in polymerization catalysis, focusing on the evolution from metallocenes to advanced non-metallocene systems. It provides an in-depth analysis of catalytic complex design, supported by quantitative performance data, detailed experimental methodologies, and essential reagent solutions, thereby offering a foundational resource for researchers and scientists engaged in the development of next-generation polymeric materials.

Catalyst Classes and Structural Evolution

From Metallocenes to Non-Metallocene Complexes

The progression of olefin polymerization catalysts represents a continuous effort to enhance activity, comonomer incorporation, and thermal stability.

- Ziegler-Natta (Z-N) Catalysts: As first-generation catalysts, Z-N systems are multi-site, leading to polymers with broad molecular weight distributions and non-uniform comonomer incorporation, making them unsuitable for high-performance POE production [33].

- Metallocene Catalysts: These single-site catalysts, such as constrained geometry catalysts (CGCs) developed by Exxon and Dow Chemical, demonstrate superior activity, narrow molecular weight distributions, and precise stereochemical control [33]. A key example is

Me₂Si(2-Me-Ind)₂ZrCl₂, which, when activated with methylaluminoxane (MAO), shows significantly higher activity and produces polypropylene with a molar mass three times greater than its unsubstituted analogue,Me₂Si(Ind)₂ZrCl₂[34]. Despite these advantages, their industrial application is limited by a tendency for molecular weight to decrease at elevated temperatures [33]. - Non-Metallocene Catalysts: This class encompasses catalysts without cyclopentadienyl (Cp) ligands, instead coordinating transition metals with heteroatom ligands [33]. They retain the single-site characteristics of metallocenes but offer distinct advantages:

- Enhanced Thermal Stability: Coordination with Group IVB metals (e.g., Hf, Zr) forms strong covalent bonds, significantly boosting stability for high-temperature solution polymerization [33].

- Tunable Ligand Environment: Ligands based on N,O- or S-donors allow for precise tuning of steric and electronic properties around the metal center [33].

- Resistance to Deactivation: Specific ligand architectures, such as imino-enamine types, are designed to resist high-temperature isomerization and decomposition pathways that plague other catalyst classes [33].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the challenges of industrial polymerization and the evolution of catalyst classes designed to address them.

Quantitative Performance of Advanced Catalysts

The performance of polymerization catalysts is quantitatively assessed by their activity, ability to maintain molecular weight, and comonomer incorporation efficiency at high temperatures. The data below compare key catalytic systems.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Group IVB Non-Metallocene Catalysts in Ethylene/1-Octene Copolymerization

| Catalyst Type | Central Metal | Temperature (°C) | Activity (g(polymer)·mol⁻¹·h⁻¹) | Molecular Weight (g·mol⁻¹) | 1-Octene Incorporation (mol%) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imino-Amido [33] | Hf | 120 | 6.6 × 10⁵ | Not Specified | Not Specified | Prone to isomerization at high T; Zr analogues are unstable at 120°C. |

| Imino-Enamine (Symmetric) [33] | Hf | 120 | 2.7 × 10⁷ | ~10⁶ | 5.4 | Excellent activity and high molecular weight. |

| Imino-Enamine (Asymmetric, a-type) [33] | Hf | 120 | 1.2 × 10⁸ | High | 8.7 | Exceptional activity and insertion rate; performance maintained at 150°C. |

| Pyridine-Imine [33] | Hf | 120 | 1.4 × 10⁸ | High | Low | High activity but low comonomer insertion tendency. |

| Silsesquioxane-Cp [35] | Ti | 50 | 28* (TOF h⁻¹) | 5,200-8,200 | N/A | For syndiotactic polystyrene; narrow dispersity (Đ). |

*TOF = Turnover Frequency

Table 2: Performance of Metallocene Catalysts in Propylene Polymerization

| Catalyst | System | Activity (kg PP·(g cat)⁻¹·h⁻¹) | Polymer Mw (Da) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Me₂Si(Ind)₂ZrCl₂ (Cat1) [34] | Homogeneous (MAO) | 4.6 | ~24,000 | Lower activity and molar mass. |

| Me₂Si(2-Me-Ind)₂ZrCl₂ (Cat2) [34] | Homogeneous (MAO) | 38.0 | ~195,000 | Higher activity and 8x higher Mw due to 2-methyl substitution. |

Experimental Protocols for Catalyst Synthesis and Evaluation

Synthesis of an Imino-Enamine Hf Catalyst Complex

The synthesis of high-performance asymmetric imino-enamine Hf complexes, as developed by Dow, can be achieved via a stable chloride intermediate route suitable for scale-up [33].

Methodology:

- Ligand Synthesis: Condense a substituted aniline with 1,2-cyclohexanedione to form the imino-enamine ligand. For asymmetric ligands, careful selection of the aniline substituent (e.g., a butyl chain) is crucial to drive the formation towards the desired, more stable "a-type" isomer [33].

- Chloro-Complex Formation: In an inert atmosphere glove box, add a tetrahydrofuran (THF) solution of the purified ligand to a slurry of HfCl₄ in toluene. Stir the reaction mixture for 12-16 hours at room temperature. The resulting solid is isolated by filtration, washed with cold toluene and cold pentane, and dried under vacuum to yield the dichloro imino-enamine Hf complex [33].

- Methylation (Alkylation): The stable chloro complex is methylated using methylmagnesium bromide (MeMgBr) or methylmagnesium iodide (MeMgI). Suspend the chloro complex in toluene and slowly add a molar equivalent of the Grignard reagent. After stirring for a defined period, the resulting trimethyl complex is recovered. This two-step methylation route avoids the need to handle highly unstable and pyrophoric Hf(CH₃)₄ intermediates, providing an overall yield of ~77% and facilitating larger-scale production [33].

High-Temperature Polymerization Procedure

Evaluation of catalyst performance is typically conducted via high-temperature solution polymerization of ethylene and 1-octene [33].

Protocol:

- Reactor Preparation: A Parr reactor is first heated under vacuum or purged with an inert gas (e.g., nitrogen or argon) to remove moisture and oxygen.

- Feedstock Introduction: The reactor is charged with the solvent (e.g., purified and dried toluene or iso-octane) and the comonomer (1-octene). The mixture is heated to the target reaction temperature (e.g., 120°C or 150°C) with continuous stirring.

- Saturating with Monomer: The reactor is pressurized with ethylene and maintained at the desired pressure throughout the experiment.