Polymer Characterization Techniques: A Comparative Guide for Biomedical Researchers and Drug Developers

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of polymer characterization techniques, tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development.

Polymer Characterization Techniques: A Comparative Guide for Biomedical Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of polymer characterization techniques, tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development. It explores the foundational principles of key methodologies, details their specific applications in pharmaceutical and biomedical contexts, offers troubleshooting and optimization strategies for complex analyses, and presents a framework for the validation and comparative selection of techniques. The scope covers chromatographic, spectroscopic, thermal, and emerging methods, with a focus on their critical role in ensuring the performance, stability, and safety of polymeric nanocarriers and biomaterials.

Understanding Polymer Properties: The Foundation of Material Performance

Polymers are fundamental to advancements in numerous scientific and industrial fields, from pharmaceutical development to aerospace engineering. Their performance is dictated by a trio of interdependent key properties: molecular weight, structure, and thermal behavior. Understanding these properties is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for comparing polymer-based products and selecting the right material for a specific application. For researchers and scientists, mastering the characterization of these properties enables the prediction of material behavior, optimization of processing conditions, and ultimately, the innovation of new products. This guide provides a comparative overview of the experimental techniques used to investigate these essential characteristics, presenting objective data and standardized protocols to inform research and development efforts.

Molecular Weight Characterization

Molecular weight (MW) and its distribution are among the most critical parameters of a polymer, profoundly influencing its mechanical strength, viscosity, solubility, and processability. Accurate determination is therefore a cornerstone of polymer characterization.

Key Techniques and Comparative Data

Different analytical techniques are employed to determine molecular weight, each with its own principles, applications, and limitations. The table below summarizes the primary methods.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Techniques for Molecular Weight Characterization

| Technique | Measured Parameter | Typical Application | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC/GPC) [1] | Molecular weight distribution, average MW (Mn, Mw) | Routine analysis of soluble polymers; quality control. | Requires polymer solubility and appropriate standards; charged polymers can adhere to columns [2]. |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) [1] | Absolute molecular weight of oligomers and polymers | Detailed structural analysis of lower MW polymers. | Can be challenging for high MW polymers and complex mixtures. |

| Viscosity Measurements [2] | Reduced viscosity, intrinsic viscosity | Indirect determination of MW via the Mark-Houwink relationship. | An indirect method; requires calibration with standards of known MW. |

| Molecular Dynamics Simulation [2] | Radius of gyration, which correlates to MW | Theoretical prediction of MW and solution behavior. | Computationally intensive; results are model-dependent. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Molecular Weight from Viscosity and Simulation

A hybrid experimental-numerical approach can be powerful for determining the molecular weight of challenging polymers, such as water-soluble ionic terpolymers. The following protocol, adapted from research, outlines this methodology [2].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a series of brine solutions (e.g., 0.1M NaCl) with varying, known concentrations of the ionic terpolymer.

- Experimental Viscosity Measurement: Measure the reduced viscosity of each polymer-brine solution at normal temperature and pressure (e.g., 30°C, 1 atm) using an appropriate viscometer.

- Molecular Dynamics Simulation Setup:

- Model Construction: Use molecular modeling software (e.g., Material Studio) to build an atomistic model of the terpolymer, optimizing its geometry and charge distribution.

- System Configuration: Create simulation boxes containing one polymer molecule, sodium and chloride ions to balance charge, and a sufficient number of water molecules (e.g., ~17,000 for a MW of 3160 g/mol) to represent the brine solvent.

- Simulation Run: Perform molecular dynamics simulations using an NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) at the target conditions. Use a force field like COMPASS II and the Ewald summation method for Coulombic interactions. An initial run of 100,000 steps (100 ps) with a 1 fs time-step achieves equilibrium.

- Data Analysis:

- From the simulation, calculate the polymer's radius of gyration (Rg), a measure of its size in solution, by averaging the square distance of each atom from the polymer's center of mass.

- Establish a mathematical relationship between the simulated Rg and the polymer's molecular weight. This can be a power-law fit (Rg ∝ Mᵞ) or an empirical formula derived from the data.

- Correlate the experimentally measured reduced viscosity with the simulated Rg and polymer concentration to estimate the molecular weight of an unknown sample.

Impact of Molecular Weight on Material Properties

The molecular weight of a polymer is a key determinant of its performance. For instance, in pharmaceutical development, the solubility of a drug in a polymer matrix is a critical factor for formulating solid dispersions. A comparative study using indomethacin and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) of different molecular weights (K12, K25, K30, K90) found that the experimental drug-polymer solubility was not significantly different across the various PVPs. The solubility was determined more by the strength of the specific drug-polymer interactions than by the polymer's molecular weight. This finding suggests that for initial screening of drug-polymer solubility, testing with a single representative molecular weight per polymer is sufficient [3] [4].

Polymer Structure Analysis

The chemical structure and morphology of a polymer define its identity and govern its interactions with other substances and the environment. Structural analysis confirms the polymer's composition and reveals details about its crystallinity and chain organization.

Key Techniques and Comparative Data

A combination of spectroscopic and microscopic techniques is typically required to fully characterize polymer structure at different length scales.

Table 2: Comparison of Key Techniques for Polymer Structure Characterization

| Technique | Primary Structural Information | Spatial Resolution / Key Output | Sample Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy [5] [6] | Chemical bonds, functional groups, molecular identity. | Infrared absorption spectrum. | Minimal sample required (particles as small as 3mm) [5]. |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy [5] [6] | Molecular structure, monomer ratios, tacticity, branching. | Chemical shift spectrum. | Typically requires less than a gram of material [5]. |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) [6] | Surface morphology, texture, filler distribution. | 2D surface image; nanometer resolution. | Samples often require conductive coating. |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) [6] | Internal microstructure, crystalline domains. | 2D projection image; sub-nanometer resolution. | Requires ultra-thin samples; low contrast can be an issue. |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) [6] | Surface topography, mechanical properties (e.g., nanomechanical mapping). | 3D surface map. | Can analyze samples in various environments (air, liquid). |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Polymer Identification via FTIR and NMR

FTIR and NMR are the two most common techniques for initial polymer structure analysis. The following is a standard protocol for polymer identification and detailed characterization [5].

- FTIR for Initial Identification:

- Sample Preparation: For a bulk polymer, a small section (as small as 3mm) can be analyzed directly using an attenuated total reflectance (ATR) accessory. For more complex samples, techniques like transmission or reflection may be used.

- Data Acquisition: Collect the infrared spectrum across a standard wavenumber range (e.g., 4000-400 cm⁻¹).

- Analysis: Compare the obtained spectrum to reference spectral libraries to identify the base polymer. The presence or absence of characteristic absorption peaks (e.g., carbonyl stretch, amine bends) confirms the polymer type and identifies major functional groups.

- NMR for Detailed Structural Elucidation:

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve a small amount (less than a gram) of the polymer in a suitable deuterated solvent. For insoluble polymers, solid-state NMR can be employed.

- Data Acquisition: Acquire ¹H (proton) and ¹³C (carbon) NMR spectra. Other nuclei like ²⁹Si or ³¹P can be analyzed if relevant.

- Analysis:

- Analyze the ¹³C NMR spectrum to determine the polymer's microstructure. The chemical shifts and splitting patterns reveal the types of carbon atoms present.

- Use the ¹H NMR spectrum to calculate the ratio of different monomers in a copolymer, such as in ABS plastic [5].

- Identify and quantify branching in polymers like polyethylene by integrating the signals from branch points versus the main chain [5].

Research Reagent Solutions for Structural Analysis

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Polymer Structure Analysis

| Item | Function in Characterization |

|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆) | Provides a solvent environment for NMR analysis without producing a large interfering signal in the spectrum. |

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | Used to prepare pellets for FTIR analysis in transmission mode for very small samples. |

| ATR Crystal (e.g., Diamond, ZnSe) | The internal reflection element in ATR-FTIR that enables direct analysis of solid samples with minimal preparation. |

| Conductive Coatings (e.g., Gold, Carbon) | Applied to non-conductive polymer samples prior to SEM analysis to prevent charging and improve image quality. |

| Ultramicrotome | Instrument used to prepare ultra-thin sections (nanometers to micrometers thick) of polymer samples for TEM analysis. |

Thermal Behavior and Stability

The response of a polymer to heat is a critical performance indicator, especially for applications in demanding environments like aerospace, automotive, and drug delivery. Thermal analysis techniques reveal phase transitions, relaxation dynamics, and decomposition profiles.

Key Techniques and Comparative Data

Thermal stability and behavior are routinely probed using a suite of complementary thermo-analytical methods.

Table 4: Comparison of Key Techniques for Thermal Behavior Analysis

| Technique | Primary Measured Property | Key Outputs & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) [7] [8] | Heat flow into/out of sample vs. temperature. | Glass transition (Tg), melting (Tm), and crystallization temperatures; degree of crystallinity; cure kinetics. |

| Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) [7] | Mass change of sample vs. temperature or time. | Thermal decomposition temperature; moisture and volatiles content; filler content in composites. |

| Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) [8] | Mechanical response (modulus, damping) under oscillatory stress. | Glass transition temperature; storage/loss moduli; viscoelastic behavior; relaxation processes. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Assessing Thermal Stability of Epoxy Composites

The thermal stability of polymers, such as those used in aerospace, is often assessed using TGA. The following protocol can be used to compare the performance of different epoxy composites [7].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare samples of the unfilled epoxy resin and the composite of interest (e.g., epoxy filled with mesoporous silica). Ensure samples are ground to a consistent powder or are cut into small, uniform pieces to ensure representative and efficient heat transfer.

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate the TGA instrument for temperature and weight using standard reference materials.

- Experimental Run:

- Load a small sample (typically 5-20 mg) into a platinum or alumina crucible.

- Purge the furnace with an inert gas, such as nitrogen, at a constant flow rate (e.g., 50 mL/min) to create a non-oxidative environment.

- Heat the sample from room temperature to a high temperature (e.g., 800°C) at a constant heating rate (e.g., 10°C/min).

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the percentage weight loss against temperature.

- Determine the onset decomposition temperature, which is the temperature at which the sample begins to lose mass rapidly. A higher onset temperature indicates greater thermal stability.

- Calculate the activation energy for thermal degradation using model-free methods like the Flynn-Wall-Ozawa method. A higher activation energy signifies that more energy is required to initiate decomposition, reflecting improved thermal stability. For example, an unfilled epoxy resin may have an activation energy of 148.86 kJ/mol, while an epoxy composite with mesoporous silica could show a significantly higher value of 217.6 kJ/mol [7].

Interrelationship of Properties: A Case Study on Thermal Conductivity

The properties of molecular weight, structure, and thermal behavior are not isolated. This interplay is evident in the challenge of polymer gears, which suffer from low thermal conductivity, leading to heat buildup and failure. A novel solution involves creating hybrid polymer gears with metal (aluminum or steel) inserts using additive manufacturing. This approach structurally modifies the polymer matrix to improve its thermal behavior. The metal inserts act as heat sinks, increasing heat dissipation from the meshing teeth. Experimental results show that this hybrid design can achieve a bulk temperature reduction of up to 9°C (17%) compared to a pure polymer gear, significantly enhancing wear resistance and load-bearing capacity without a fundamental change in the polymer's molecular weight or chemical structure [9].

The comparative data and experimental protocols presented in this guide underscore a central theme: a comprehensive understanding of polymers requires a multi-faceted analytical approach. Molecular weight characterization predicts solubility and processing, structural analysis confirms chemical identity and morphology, and thermal analysis ensures performance under application-specific stresses. These properties are deeply intertwined, as a change in one often directly impacts the others. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the right combination of characterization techniques is paramount. The choice depends on the specific polymer system and the critical performance metrics for the intended application. By leveraging these standardized methodologies, scientists can make informed comparisons, troubleshoot manufacturing issues, and drive the development of next-generation polymeric materials with tailored properties.

Characterization techniques are fundamental tools in materials science, chemistry, and pharmaceutical development, enabling researchers to decipher the composition, structure, and properties of substances. For professionals engaged in polymer research or drug development, selecting the appropriate analytical method is crucial for obtaining accurate, relevant data. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of four principal characterization categories—chromatographic, spectroscopic, thermal, and mechanical—framed within the context of polymer characterization research. By presenting objective performance comparisons, detailed methodologies, and technical specifications, this article serves as a strategic resource for scientists making informed decisions about their analytical workflows.

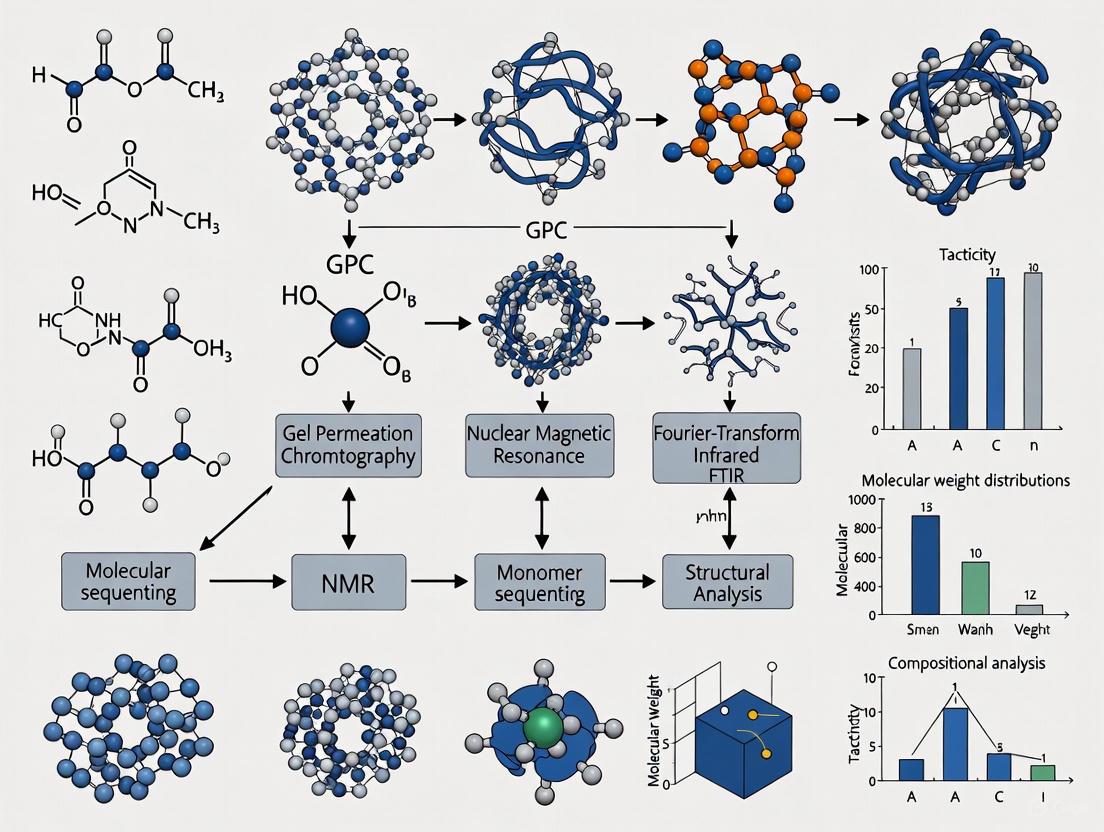

The following diagram outlines a generalized decision-making workflow for selecting an appropriate characterization technique based on key material properties and information requirements.

Comparative Analysis of Technique Categories

The table below provides a high-level comparison of the four characterization technique categories, highlighting their primary functions, common variants, and key applications relevant to polymer and pharmaceutical research.

Table 1: Overview of Major Characterization Technique Categories

| Technique Category | Core Principle | Key Variants | Primary Outputs | Typical Polymer/Drug Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatographic | Separates components in a mixture based on partitioning between mobile and stationary phases. | GC-MS, GC-MS/MS, GC-NCI-MS [10] | Retention time, peak area/height, mass spectra, concentration. | Analysis of residual monomers, plasticizers, drug impurities, biomarkers in urine [10]. |

| Spectroscopic | Probes interaction between matter and electromagnetic radiation. | UV-Vis, FTIR [11] | Absorbance/transmittance/reflectance spectra, functional group identification, concentration. | Monitoring resin curing [11], chemical composition analysis [12]. |

| Thermal | Measures physical and chemical properties as a function of temperature. | DSC, TGA, DMA, TMA [13] | Melting point (Tm), glass transition (Tg), mass loss, modulus, thermal stability. | Determining polymer purity, thermal stability, filler content, and viscoelastic properties [13]. |

| Mechanical | Applies force to measure material deformation and failure. | DMA, TMA [13] | Storage/loss modulus (E', E"), damping factor (tan δ), creep, stress-strain curves. | Characterizing rigidity, toughness, impact strength, and viscoelastic behavior of polymers [13]. |

Detailed Technique Comparisons and Experimental Data

Chromatographic Techniques

Chromatographic methods are unparalleled for separating and analyzing the components of complex mixtures. Gas chromatography coupled with various detectors is particularly powerful for volatile and semi-volatile analytes.

Table 2: Comparison of Gas Chromatographic Techniques for Aromatic Amine Analysis

| Parameter | GC-EI-MS (SIM) | GC-NCI-MS | GC-EI-MS/MS (MRM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Electron Impact ionization with Single-Ion Monitoring [10] | Negative Chemical Ionization [10] | Electron Impact with Multiple Reaction Monitoring [10] |

| Linear Range | 3-5 orders of magnitude [10] | 3-5 orders of magnitude (with exceptions) [10] | 3-5 orders of magnitude [10] |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | 9–50 pg/L [10] | 3.0–7.3 pg/L [10] | 0.9–3.9 pg/L [10] |

| Precision (Intra-day Repeatability) | < 15% for most levels [10] | < 15% for most levels [10] | < 15% for most levels [10] |

| Key Advantage | Good sensitivity and widely available technology. | Excellent sensitivity for electronegative atoms. | Superior selectivity and lowest detection limits. |

Experimental Protocol: GC Analysis of Aromatic Amines in Urine

The following workflow details a method for analyzing aromatic amines in urine, a relevant application for biomonitoring and toxicology studies [10].

- Sample Hydrolysis: Add 10 mL of concentrated HCl (37%) to 20 mL of urine. Heat at 80°C for 12 hours with stirring (e.g., 200 rpm) to convert metabolized aromatic amines back to their free forms [10].

- Basification and Extraction: Once cooled, basify the solution with 20 mL of 10 M NaOH. Extract the free amines twice using 5 mL of diethyl ether each time. Combine the organic fractions [10].

- Clean-up: Wash the combined ether extract with 2 mL of 0.1 M NaOH to remove acidic interferences [10].

- Back-Extraction and Acidification: Back-extract the amines into 10 mL of water acidified with 200 µL of concentrated HCl. Evaporate any residual diethyl ether by blowing nitrogen over the sample for 20 minutes [10].

- Derivatization (Sandmeyer-like Reaction): Convert the aromatic amines to their iodinated derivatives to reduce polarity and improve chromatographic performance. This involves diazotization with sodium nitrite followed by iodination with hydriodic acid [10].

- Instrumental Analysis: Inject the derivatized sample into the GC system. The separation and detection conditions must be optimized for the specific GC technique (e.g., GC-MS, GC-NCI-MS, or GC-MS/MS) as outlined in Table 2 [10].

Spectroscopic Techniques

Spectroscopic techniques provide insights into molecular structure and composition by measuring the interaction of light with matter. The utility of the raw data obtained is often greatly enhanced through statistical preprocessing.

Table 3: Comparison of Statistical Preprocessing Techniques for Spectroscopic Data

| Preprocessing Method | Formula | Effect on Spectral Data | Suitability for Polymer Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standardization (Z-score) | ( Zi = (Xi - μ) / σ ) [12] | Transforms data to a distribution with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. | Excellent for comparing spectra from different instruments or samples with varying baseline offsets. |

| Affine Transformation (Min-Max Normalization) | ( f(x) = (x - r{min}) / (r{max} - r_{min}) ) [12] | Scales all data points to a fixed range, typically [0, 1]. | Highly effective for highlighting the shapes of spectral signatures, such as peaks and valleys in polymer FTIR spectra [12]. |

| Mean Centering | ( X'i = Xi - μ ) [12] | Subtracts the mean from each data point, centering the spectrum around zero. | A common first step before multivariate analysis to focus on variation between samples. |

| Normalization to Maximum | ( X'i = Xi / X_{max} ) [12] | Divides each data point by the maximum value in the spectrum. | Useful for comparing the relative intensity of absorption bands when absolute reflectance varies. |

Experimental Protocol: UV-Vis Spectroscopy for Vat Photopolymerization Resin Design

UV-Vis spectroscopy is critical for designing resins used in vat photopolymerization (VPP) 3D printing, as it determines the penetration depth of UV light and thus the curing efficiency and resolution [11].

- Sample Preparation: The liquid photopolymer resin is placed into a standard quartz cuvette. Ensure the cuvette is clean and free of scratches to avoid light scattering.

- Instrument Calibration: Perform a baseline correction with a blank cuvette filled with a non-UV-absorbing solvent if necessary.

- Data Acquisition: Place the sample cuvette in the spectrometer and acquire the absorbance spectrum across the relevant UV and visible range (e.g., 200-500 nm). The critical parameter is the molar attenuation coefficient (ε) at the wavelength of the 3D printer's light source (e.g., 365 nm or 405 nm) [11].

- Data Analysis: The measured absorbance and known sample concentration are used to calculate ε via the Beer-Lambert law (A = ε * c * l). This coefficient directly influences the cure depth of the resin and is a key parameter for predicting and optimizing printability [11].

Thermal Analysis Techniques

Thermal analysis characterizes how material properties change with temperature, providing essential data on stability, composition, and phase transitions for polymers and pharmaceuticals.

Table 4: Comparison of Common Thermal Analysis Techniques

| Technique | Measured Property | Typical Sample Mass | Key Applications in Polymer Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Heat flow into/out of sample vs. temperature [13] | ~100 mg [14] | Glass transition (Tg), melting/crystallization (Tm/Tc), degree of cure, oxidation stability, purity [13]. |

| Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) | Mass change vs. temperature [13] | ~10 mg [13] | Thermal stability, decomposition temperatures, composition (moisture, polymer, filler, ash content) [13] [14]. |

| Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) | Viscoelastic properties (modulus, damping) under oscillatory stress [13] | Varies with geometry [13] | Glass transition temperature (most sensitive method), storage/loss moduli (E', E"), damping (tan δ), crosslink density [13]. |

| Thermomechanical Analysis (TMA) | Dimensional change vs. temperature or force [13] | Varies with geometry [13] | Coefficient of thermal expansion (CLTE), softening point, heat deflection temperature [13]. |

Experimental Protocol: Determining Polymer Composition and Transitions via TGA & DSC

A combined TGA-DSC analysis is a powerful approach for comprehensively characterizing a polymer material.

TGA for Compositional Analysis:

- Calibration: Calibrate the TGA balance according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Sample Loading: Precisely weigh 5-20 mg of the polymer sample into a clean, tared alumina crucible.

- Method Programming: Run a temperature ramp from room temperature to 800-1000°C under a nitrogen atmosphere (e.g., at 10-20°C/min) to assess thermal stability and polymer content. Then, switch to air or oxygen to burn off any carbon black and determine the inorganic filler and ash content [13].

- Data Interpretation: The mass loss steps correspond to the volatilization of moisture, plasticizers, polymer decomposition, and finally, the combustion of carbon black.

DSC for Transition Analysis:

- Calibration: Calibrate the DSC for temperature and enthalpy using indium or other standards.

- Sample Loading: Place a small, hermetically sealed pan containing 3-10 mg of the polymer sample in the instrument. An empty sealed pan is used as a reference.

- Method Programming: Run a heat/cool/heat cycle. For example: equilibrate at -50°C, heat to 300°C (first heat, erases thermal history), cool back to -50°C, and reheat to 300°C (second heat, reveals intrinsic material properties). Use a constant purge of nitrogen gas.

- Data Interpretation: Analyze the second heating curve for the glass transition temperature (Tg), melting point (Tm), crystallization temperature (Tc), and corresponding enthalpies. The first heat can provide information about the material's processing history and percent cure [13] [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful characterization relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table lists key items used in the experimental protocols cited in this guide.

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Characterization

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Iodinated Aromatic Standards | High-purity (>97%) quantitative standards for calibration [10] | Used as internal or external standards for the GC-MS analysis of derivatized aromatic amines [10]. |

| Hydriodic Acid (HI) | Derivatization agent for amine functional groups [10] | Used in the Sandmeyer-like reaction to convert aromatic amines into less polar, more volatile iodinated derivatives for GC analysis [10]. |

| Hermetic DSC Crucibles | Sealed containers for DSC sample preparation [13] | Prevents solvent evaporation or sample degradation during heating, crucial for measuring accurate transition temperatures in polymers or pharmaceuticals. |

| Nitrogen Gas (High Purity) | Inert purge gas for thermal analysis [13] | Creates an oxygen-free environment in TGA and DSC, preventing oxidative degradation and allowing for the measurement of inert thermal stability. |

| Polymer Photopolymer Resin | Light-activated formulation for 3D printing [11] | The subject of UV-Vis characterization to determine molar attenuation coefficient and predict cure depth in vat photopolymerization [11]. |

| Alumina Crucibles | Sample holders for TGA [13] | Inert, high-temperature resistant containers for holding polymer samples during TGA analysis. |

| Quartz Cuvettes | Sample holders for UV-Vis spectroscopy [11] | Transparent to UV and visible light, allowing for accurate measurement of a resin's absorption spectrum. |

The Impact of Molecular Weight Distribution (MWD) and Chemical Composition on Material Behavior

The behavior of polymeric materials, from their processing characteristics to their final mechanical performance, is intrinsically governed by two fundamental factors: their chemical composition and their Molecular Weight Distribution (MWD). MWD, also referred to as polydispersity, describes the statistical distribution of individual polymer chain lengths within a given sample [15]. Far from being a mere technical specification, a polymer's MWD is a critical material property that decisively influences crystallization kinetics, mechanical strength, thermal stability, and processability [15] [16]. Similarly, the chemical composition—including the choice of monomers, the incorporation of additives, and the presence of branching agents—defines the polymer's inherent chemical nature and potential for intermolecular interactions. In the demanding field of drug development, a precise understanding of how MWD and composition dictate material behavior is essential for designing effective polymeric drugs, excipients, and delivery systems [17]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these relationships, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform the decisions of researchers and scientists.

Analytical Techniques for MWD and Composition

Accurately characterizing MWD and chemical composition is the cornerstone of polymer analysis. The following table summarizes the primary techniques employed, their operating principles, and the specific information they yield.

Table 1: Essential Analytical Techniques for Polymer Characterization

| Technique | Fundamental Principle | Key Outputs | Role in MWD/Composition Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC)/Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Separation of polymer molecules by hydrodynamic volume in a porous column [18]. | Molecular weight averages (Mn, Mw), Polydispersity Index (Đ), MWD curve [18] [19]. | The primary method for directly determining the MWD and calculating average molecular weights and dispersity [19]. |

| Melt Flow Index (MFI) | Measures the mass of polymer extruded through a die in ten minutes under a specified load and temperature [20]. | Melt Flow Rate (g/10 min). | A single-point, quality-control test inversely related to melt viscosity. It is sensitive to average molecular weight but cannot detect MWD breadth or branching [20]. |

| Rheometry (Oscillatory Shear) | Applies a small oscillatory deformation to measure the viscoelastic response of a polymer melt [20]. | Complex viscosity (η*) vs. angular frequency (ω), storage and loss moduli. | Low-frequency data correlates with molecular weight (Mw). The breadth of the shear-thinning region is a sensitive indicator of MWD breadth, providing a more process-relevant assessment than MFI [20]. |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy | Absorbs radiofrequency radiation by atomic nuclei in a magnetic field, sensitive to the local chemical environment [18] [19]. | Polymer backbone structure, tacticity, copolymer composition, branching [18] [19]. | Elucidates chemical composition and microstructural features that, together with MWD, determine ultimate material properties. |

| Mass Spectrometry (e.g., GC/MS, LC/MS) | Ionizes chemical species and sorts them based on their mass-to-charge ratio [19]. | Identification and quantification of low molecular weight components (additives, residual monomers) [19]. | Critical for identifying chemical additives (e.g., antioxidants, plasticizers) that modify material behavior but are not part of the primary polymer structure. |

Experimental Data: Correlating MWD to Material Properties

The following case study and synthesized data table demonstrate how MWD directly influences material behavior, even when average molecular weights are identical.

Case Study: Linear Low-Density Polyethylene (LLDPE)

A compelling experiment compared three LLDPE samples with identical weight-average molecular masses (Mw ≈ 106 kg/mol) and nearly identical Melt Flow Indices (MFI ~0.92 g/10 min) [20]. The sole stated difference was their MWD, categorized by the supplier as either "medium" or "narrow". Rheological characterization revealed profound differences:

- Viscosity Profile: While all three samples exhibited shear-thinning, LLDPE #3 (narrow MWD) displayed a Newtonian plateau at low frequencies, indicative of its narrower distribution. In contrast, LLDPE #1 and #2 (medium MWD) showed continuous shear-thinning without a plateau, suggesting a broader distribution [20].

- Processability Implications: At high shear rates relevant to processing (e.g., extrusion >10 rad/s), LLDPE #3 had the highest viscosity, making it more energy-intensive to process. The broader MWD samples (LLDPE #1 and #2) exhibited lower processing viscosities, facilitating easier extrusion [20].

- MWD Breadth Ranking: Based on the shear-thinning behavior, the apparent MWD breadth was determined to be: LLDPE #3 (narrowest) < LLDPE #1 < LLDPE #2 (widest) [20].

Table 2: Experimental Data from Rheological Analysis of LLDPE Samples [20]

| Sample | Reported MWD | MFR (g/10 min) | Mw (kg/mol) | Zero-Shear Viscosity (η₀) Trend | Shear-Thinning Onset | Inferred Ease of Processing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLDPE #1 | Medium | 0.920 | 106 | Very High (no plateau) | Low Frequency | Easier |

| LLDPE #2 | Medium | 0.916 | 106 | Highest (no plateau) | Lowest Frequency | Easiest |

| LLDPE #3 | Narrow | 0.918 | 106 | Low (clear plateau) | High Frequency | Most Difficult |

Protocol: Rheological Characterization of Polymer Melts

Method: Small-Amplitude Oscillatory Shear Frequency Sweep [20]. Objective: To determine the shear-dependent viscosity profile and infer MWD characteristics. Steps:

- Sample Preparation: Place polymer pellets directly between the parallel plates of a rheometer.

- Melting: Melt the sample into a disk-shaped specimen at the test temperature (e.g., 190°C for polyethylene).

- Instrument Setup: Use a parallel plate geometry (e.g., 20 mm diameter) with a set gap (e.g., 0.75 mm). Employ electric plate and hood modules for precise temperature control.

- Frequency Sweep:

- Apply a small, constant strain (e.g., 0.1%) to ensure the material remains in the linear viscoelastic region.

- Sweep the angular frequency from 100 rad/s to 0.1 rad/s.

- Collect multiple data points per frequency decade.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot complex viscosity (|η*|) versus angular frequency (ω).

- Apply the Cox-Merz rule, which equates complex viscosity versus frequency to steady-state shear viscosity versus shear rate.

- Analyze the low-frequency plateau for zero-shear viscosity (related to Mw) and the breadth of the shear-thinning region (related to MWD).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and materials are fundamental for research involving polymer synthesis and characterization, particularly in controlled MWD design.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Polymer Synthesis and Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Application in MWD/Composition Research |

|---|---|---|

| Tubular Flow Reactor | A computer-controlled continuous flow system that enables precise mixing and residence time control [16]. | Key for synthesizing polymers with targeted, complex MWD shapes by accumulating narrow MWD "pulses" in a collection vessel [16]. |

| Monofunctional Initiator / Chain Terminator | A molecule that starts polymer chain growth or ends it, controlling the maximum possible chain length [21]. | Used in ring-opening polymerization (e.g., of lactide) and anionic polymerization to control average molecular weight and prevent gelation [16] [21]. |

| Multifunctional Branching Agent | A monomer with three or more reactive functional sites (e.g., tris[4-(4-aminophenoxy)phenyl] ethane) [21]. | Introduces long-chain branching into polymers during step-growth polymerization, dramatically altering rheology and mechanical properties [21]. |

| Static Mixers | In-line mixing elements that disrupt laminar flow in a reactor [16]. | Ensure rapid and homogeneous mixing of monomer and initiator at the inlet of a flow reactor, which is critical for achieving simultaneous initiation and narrow MWD polymer blocks [16]. |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., CDCl₃) | Solvents containing deuterium for lock-signal stabilization in NMR spectroscopy [18]. | Essential for preparing polymer samples for NMR analysis to determine chemical composition, tacticity, and comonomer ratios [18] [19]. |

MWD Design and Its Impact on Crystalline Structures

Advanced synthesis techniques now allow for the design of specific MWDs. A prominent method uses a computer-controlled tubular flow reactor to produce targeted MWDs by accumulating sequential "pulses" of narrow-dispersity polymer [16]. This "design-to-synthesis" protocol leverages Taylor dispersion to achieve plug-flow-like behavior, ensuring consistent residence time for each pulse [16].

The resulting MWD profoundly influences the crystalline architecture of semi-crystalline polymers. In polydisperse systems, molecular segregation occurs during crystallization, where chains of different lengths separate [15]. This leads to complex crystalline textures.

Diagram 1: From MWD to crystalline morphology. HMW: High Molecular Weight; LMW: Low Molecular Weight.

For instance, in poly(ethylene oxide) blends, HMW components nucleate first, forming thin-lamellar dendrites in the interior of a spherulite, while LMW components subsequently form thicker lamellae at the periphery, creating a nested structure [15]. Furthermore, under flow fields, HMW components with high entanglement density are more prone to form the oriented central "shish," while LMW components with high chain mobility crystallize as the folded-chain "kebabs" [15].

The experimental data and comparisons presented confirm that Molecular Weight Distribution is not a secondary parameter but a primary design variable that interacts synergistically with chemical composition to dictate polymer behavior. While techniques like MFI offer simple quality control, advanced rheology and GPC are indispensable for linking MWD to process-relevant properties. The emerging ability to precisely design MWDs through synthetic techniques like flow chemistry opens new frontiers in tailoring polymers for specific applications. For drug development professionals, this deep understanding is crucial for designing polymeric drugs with optimized bioactivity and for engineering robust, scalable nanoparticle delivery systems where consistency in MWD ensures predictable performance, stability, and drug release profiles.

Linking Intrinsic Properties to Processing and End-Use Performance

The performance of a polymer in its final application—whether in drug delivery, automotive components, or sustainable packaging—is not determined by chance but by a fundamental relationship between its intrinsic properties, processing history, and end-use conditions. This property-structure-processing-performance (PSPP) relationship forms the cornerstone of advanced polymer science and engineering [22]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these interconnected relationships is crucial for selecting the right polymer for specific applications, troubleshooting manufacturing issues, and innovating new material solutions. Polymers exhibit wide variations in properties even within the same chemical family, largely due to differences in processing conditions that alter their chemical and physical structures [23]. This comparative guide objectively analyzes major polymer characterization techniques, providing experimental data and methodologies to bridge the gap between fundamental polymer properties and their real-world performance across pharmaceutical, materials, and industrial applications.

Essential Polymer Characterization Techniques

The strategic selection of characterization techniques is fundamental to linking polymer properties to performance. Each technique provides unique insights into different aspects of polymer structure and behavior, forming a complementary analytical toolkit for researchers.

Table 1: Core Polymer Characterization Techniques and Their Applications

| Technique Category | Specific Technique | Key Measured Parameters | Primary Applications in Performance Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectroscopy | FTIR | Functional groups, additive presence, chemical changes | Verification of raw materials, troubleshooting production issues [18] |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Structural variations, especially in complex/colored samples | Complementary structural analysis to FTIR [18] | |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Polymer backbone structure, tacticity, copolymer composition | Detailed chemical structure elucidation [18] | |

| Chromatography | GPC/SEC | Molecular weight distribution, polydispersity, chain size | Assessment of polymer quality, degradation, and batch consistency [18] |

| HPLC | Non-volatile additives (antioxidants, plasticizers, stabilizers) | Quantification of additive packages and impurities [18] | |

| GC | Residual monomers, solvents, degradation products | Purity assessment and safety profiling [18] | |

| Thermal Analysis | DSC | Melting, crystallization, glass transitions | Determination of processing windows and stability [18] |

| TGA | Weight loss due to thermal degradation or volatile release | Prediction of shelf life and thermal stability [18] | |

| Mechanical Testing | Dynamic Mechanical Analysis | Thermo-mechanical behavior, viscoelastic properties | Performance under application conditions [24] |

| Indirect Tensile Strength | Material strength, failure characteristics | Comparative performance assessment [25] |

Experimental Case Studies: From Characterization to Performance Prediction

Case Study 1: Polymer-Modified Asphalt for Enhanced Road Performance

Objective: To evaluate and compare the mechanical properties of various polymer-modified asphalt (PMA) mixtures under demanding environmental conditions [25].

Experimental Methodology:

- Materials: Base asphalt binder (PG64-22), five different polymers (Lucolast 7010, Anglomak 2144, Pavflex140, SBS KTR 401, EE-2), limestone aggregate

- Sample Preparation: Polymers were mixed with base asphalt using an asphalt blender. Polymer content was optimized to achieve Performance Grade PG 76-10 required for high-temperature regions (Riyadh, KSA). Dense-graded asphalt mixtures were prepared according to Ministry of Transportation specifications [25].

- Testing Protocols:

- Dynamic Modulus Test: Assessed stiffness under varying temperatures and loading frequencies

- Flow Number Test: Measured rutting resistance under repeated axial stress

- Hamburg Wheel Tracking Test: Evaluated moisture and rutting susceptibility

- Indirect Tensile Strength Test: Determined resistance to cracking

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Polymer-Modified Asphalt Mixtures [25]

| Polymer Type | Dynamic Modulus (MPa) | Flow Number (cycles) | Hamburg Rut Depth (mm) | Indirect Tensile Strength (kPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (Unmodified) | Benchmark | Benchmark | Benchmark | Benchmark |

| Anglomak 2144 | Highest improvement | |||

| Paveflex140 | ||||

| EE-2 | ||||

| SBS KTR 401 | ||||

| Lucolast 7010 |

Key Findings: All PMA mixtures demonstrated superior mechanical properties compared to the unmodified control. Anglomak 2144 consistently ranked as the best-performing modifier, exhibiting the highest resistance to permanent deformation and optimal stiffness characteristics, followed by Paveflex140 and EE-2 [25]. This comprehensive comparison enables pavement engineers to select polymers based on performance data rather than simply meeting specification thresholds.

Case Study 2: Nanocomposites for Advanced Applications

Objective: To investigate how nanofillers enhance polymer properties for specialized applications including optoelectronics, thermal management, and biomedical devices [24].

Experimental Methodology:

- Materials: Various polymer matrices (epoxy, polyvinyl alcohol, poly(methyl methacrylate), poly(dimethylsiloxane)) and nanofillers (silica, MgO, alumina, SrTiO3, carbon nanotubes, functionalized graphene)

- Sample Preparation: Employed processing techniques including solution casting [24], in situ sol-gel synthesis [24], and melt compounding

- Testing Protocols:

- DC Breakdown Characteristics: Evaluated electrical insulation properties (epoxy/silica nanocomposites)

- Dynamic Mechanical Analysis: Assessed thermo-mechanical behavior (carbon nanotube/epoxy films)

- Antibacterial Testing: Quantified microbial growth inhibition (PVA/functionalized graphene)

- Optical Property Analysis: Measured transparency and UV absorption (PVA/SrTiO3/CNT films)

Key Findings: The incorporation of nanofillers produced substantial improvements in target properties. Epoxy nanocomposites demonstrated enhanced DC breakdown characteristics, while polyvinyl alcohol-based films with SrTiO3 and carbon nanotubes showed promise for optoelectronic applications [24]. Poly(methyl methacrylate) reinforced with hybrid SrTiO3/MnO2 nanoparticles exhibited potential for dental applications [24]. The study confirmed that the interface between nanofillers and polymer matrix critically determines final performance.

Case Study 3: Flame-Retardant Polymer Systems

Objective: To develop and characterize flame-retardant polymer formulations for enhanced fire safety [24].

Experimental Methodology:

- Materials: Bio-based flame retardants (phytic acid, chitosan), conventional flame retardants (ammonium polyphosphate, melamine), polymer matrices (urea/formaldehyde resins, rigid polyurethane foams, polypropylene)

- Sample Preparation: Synthesis of bio-based flame retardants followed by incorporation into polymer matrices through compounding and curing processes

- Testing Protocols:

- Limiting Oxygen Index: Measured minimum oxygen concentration supporting combustion

- Ul-94 Vertical Burning: Classified burning behavior

- Cone Calorimetry: Quantified heat release rate and smoke production

Key Findings: Bio-based flame retardants from phytic acid and chitosan demonstrated effective flame retardancy when combined with melamine and polyvinyl alcohol in intumescent urea/formaldehyde resins [24]. The synergistic combination of ammonium polyphosphate and nickel phytate significantly enhanced flame-retardant properties in rigid polyurethane foams [24]. The incorporation of carbon nanotubes and carbon black into linear low-density polyethylene/ethylene-vinyl acetate blends containing mineral flame retardants improved both mechanical behavior and flame retardancy [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Polymer Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Matrix Systems | Base material for composite formation | Epoxy, polyvinyl alcohol, poly(methyl methacrylate) [24] |

| Nanofillers | Enhance mechanical, electrical, or thermal properties | Silica, MgO, alumina, carbon nanotubes, functionalized graphene [24] |

| Flame Retardants | Improve fire resistance | Ammonium polyphosphate, nickel phytate, bio-based phytate/chitosan systems [24] |

| Spectroscopic Reagents | Enable structural characterization | Deuterated solvents for NMR, KBr pellets for FTIR [18] |

| Chromatography Standards | Calibration and quantification | Narrow dispersity polystyrene standards for GPC [18] |

| Thermal Analysis Reference Materials | Instrument calibration | Indium, zinc for DSC; certified reference materials for TGA [18] |

Advanced Visualization: Experimental Workflows and Relationships

PSPP Relationship Framework

Diagram 1: The PSPP relationship framework illustrates how processing conditions determine polymer structure, which governs material properties that ultimately predict end-use performance [23] [22]. The direct link between processing and performance highlights that manufacturing history can immediately impact how a polymer behaves in application.

Polymer Characterization Workflow

Diagram 2: The comprehensive polymer characterization workflow progresses from sample preparation through structural, thermal, and mechanical analysis to enable accurate performance prediction [18]. This sequential approach ensures that fundamental chemical structure is linked directly to macroscopic behavior.

The rigorous characterization of polymers through the detailed methodologies presented in this guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with critical insights for predicting end-use performance. The experimental data confirms that strategic polymer modification—through nanofillers, flame retardants, or performance-enhancing additives—significantly alters material behavior in predictable ways when proper structure-property relationships are established. The PSPP framework serves as an indispensable paradigm for linking intrinsic polymer properties to processing parameters and ultimate application performance, enabling more informed material selection and innovation across pharmaceutical, materials, and industrial sectors. As polymer science advances, the continued refinement of these characterization approaches and relationships will be essential for developing next-generation materials with tailored performance characteristics.

A Deep Dive into Core Techniques and Their Biomedical Applications

In the field of polymer science, understanding both the molecular weight distribution (MWD) and the chemical composition distribution (CCD) is crucial for correlating macromolecular structure with end-use properties. Gel Permeation or Size Exclusion Chromatography (GPC/SEC) has long been established as the gold standard technique for determining MWD, providing indispensable information about the size and molecular weight of polymer chains in solution [26]. However, as industrial polyolefins and advanced copolymers have grown more complex, often featuring non-homogeneous comonomer incorporation, the analysis of chemical composition distribution has emerged as an equally critical parameter for predicting material performance [27]. For this purpose, temperature gradient interaction chromatography (TGIC) and solvent gradient interaction chromatography (SGIC) have developed as powerful techniques that separate polymer molecules based on their chemical composition rather than molecular size [28].

These chromatographic methods operate on fundamentally different separation mechanisms that make them ideally suited for their respective characterization roles. GPC/SEC separates polymer molecules according to their hydrodynamic volume as they travel through a column packed with porous particles, with smaller molecules penetrating more pores and thus eluting later than larger molecules [29]. In contrast, SGIC and TGIC are adsorption-based techniques that utilize a graphitized carbon column and either a solvent gradient or temperature gradient, respectively, to separate macromolecules based on their chemical composition, particularly the level of short-chain branching in polyolefins [28]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these complementary techniques, offering researchers a clear framework for selecting the appropriate methodology based on their specific characterization needs.

GPC/SEC for Molecular Weight Distribution Analysis

Fundamental Principles and Instrumentation

GPC/SEC operates on the principle of steric exclusion, where polymer molecules in solution are separated according to their hydrodynamic volume or size as they pass through a column packed with porous stationary phase particles [29]. The separation mechanism is based on the differential access smaller molecules have to the pore volumes of the stationary phase, with larger molecules being excluded from smaller pores and thus eluting first, while smaller molecules can enter more pores and take a longer path through the column, resulting in later elution. The resulting chromatogram provides a direct representation of the polymer's molecular weight distribution, which can be quantified using appropriate calibration standards [30].

The instrumentation for GPC/SEC typically consists of an autosampler, pumping system, columns, and various detection systems. Modern GPC systems offer different configurations optimized for specific applications. For research and development laboratories requiring high-throughput and comprehensive characterization, systems like the GPC-IR offer fully automated operation for 42 or 66 samples with compatibility with advanced detectors including light scattering and viscometry [26]. For quality control environments where speed and simplicity are prioritized, instruments like the GPC-QC are tailored for single-sample analysis with rapid cycle times, utilizing a single rapid GPC column and magnetic stirring for faster dissolution [26]. Both systems incorporate nitrogen purging to prevent oxidative degradation of samples and can be equipped with infrared detection for chemical composition analysis alongside molecular weight distribution determination.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Implementing reliable GPC/SEC analysis requires careful attention to experimental parameters and methodology. The following protocol outlines a standard approach for molecular weight distribution analysis:

Sample Preparation: Weigh precise amounts of polymer sample (typically <1 mg to 60 mg depending on system) into appropriate vials. Add the appropriate mobile phase solvent (often tetrahydrofuran for room-temperature GPC or 1,2,4-trichlorobenzene for high-temperature analysis of polyolefins) to achieve desired concentration [26]. For high-temperature GPC, purge vials with nitrogen to prevent oxidative degradation.

Dissolution: Dissolve samples using gentle shaking or magnetic stirring, with dissolution times varying from 20 minutes for QC systems to 60 minutes for R&D systems [26]. Heating may be required for polymers with high crystallinity or high melting points, with polyolefins typically requiring temperatures above 160°C to remain in solution [29].

Column Selection and Configuration: Select appropriate column chemistry based on polymer solubility and analysis requirements. Polymer-based columns offer wider pH and temperature stability, while silica-based columns provide higher pressure stability and excellent resolution in narrow molar mass ranges [29]. For broad MWD samples, combine multiple columns with different pore sizes to extend the separation range.

System Calibration: Perform regular calibration using narrow dispersity polymer standards of known molecular weight. Establish a calibration curve correlating elution volume with molecular weight. For absolute molecular weight determination, utilize multi-angle light scattering detection in conjunction with concentration-sensitive detectors [30].

Analysis Parameters: Set flow rate appropriate for column dimensions (typically 0.5-1.0 mL/min for analytical columns). Maintain constant temperature throughout the system to ensure reproducible separations. For high-temperature GPC, dedicated temperature-controlled compartments for columns ensure optimal stability [26].

Detection and Data Analysis: Utilize refractive index (RI) detection for concentration determination. For advanced structural information, incorporate multiple detection systems including light scattering for absolute molecular weight, viscometry for branching analysis, and infrared spectroscopy for chemical composition [26] [30].

Table 1: Comparison of GPC System Configurations for Different Application Needs

| Parameter | GPC-IR (R&D Focus) | GPC-QC (Quality Control) |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Throughput | 42 or 66 samples automatically | Single-sample analysis |

| Sample Mass Range | <1 mg to 8 mg in 8 mL | <6 mg to 60 mg in 60 mL |

| Dissolution Method | Gentle shaking (minimizes shear degradation) | Magnetic stirring (accelerates dissolution) |

| Dissolution Time | Minimum 60 minutes | Minimum 20 minutes |

| Column Configuration | 3-4 analytical columns with dedicated temperature control | Single rapid column without dedicated column oven |

| Light Scattering Detection | Compatible | Not compatible |

| Viscometer Detection | Compatible | Compatible |

Applications and Data Interpretation

The primary application of GPC/SEC is the determination of molecular weight averages (Mn, Mw, Mz) and molecular weight distribution (MWD = Mw/Mn), which are fundamental parameters influencing polymer properties including mechanical strength, melt viscosity, and processability. Beyond these basic parameters, advanced GPC/SEC with multiple detection provides insights into polymer architecture including long-chain branching determination through intrinsic viscosity measurements [26], and compositional heterogeneity through coupled IR detection for chemical composition.

When analyzing GPC/SEC data, the molecular weight distribution is represented as a plot of detector response versus elution volume, which is converted to molecular weight through the calibration curve. A narrow, symmetric distribution indicates a homogeneous polymer population, while broad or multimodal distributions suggest the presence of multiple molecular weight populations or polymer fractions. For copolymers, coupling GPC with composition-sensitive detectors like IR or UV provides information on how chemical composition varies with molecular weight, offering crucial insights for complex materials like graft copolymers or polymer blends.

SGIC and TGIC for Chemical Composition Distribution

Fundamental Principles and Separation Mechanisms

SGIC and TGIC are adsorption-based chromatographic techniques specifically developed for analyzing the chemical composition distribution of polyolefins and other polymers that are challenging to characterize using traditional methods [28]. Both techniques utilize graphitized carbon columns or other atomic level flat surface (ALFS) adsorbents, which interact with polymer molecules through weak van der Waals forces. The adsorption strength depends on the available surface area of the molecule in contact with the adsorbent, which is influenced by the polymer's chemical structure, particularly the presence of short-chain branches that reduce the interaction with the flat adsorbent surface [28].

In SGIC, separation is achieved through a gradient of increasing solvent strength, typically starting with a weak solvent and progressing to a stronger one, which desorbs polymer molecules based on their interaction with the stationary phase. The less branched (more linear) molecules have greater interaction with the graphitized carbon surface and require stronger solvents or later in the gradient to be desorbed, while highly branched molecules elute earlier [28]. TGIC utilizes an isocratic solvent system with a temperature gradient to control the adsorption/desorption process. Molecules are adsorbed at low temperatures and then desorbed as the temperature increases, with more linear molecules requiring higher temperatures for desorption [28]. The separation order in both techniques follows a predictable pattern based on branch content, with a linear correlation between comonomer mole percentage and elution volume or temperature.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The application of SGIC and TGIC requires specific instrumentation and methodological considerations:

Sample Preparation: Dissolve polymer samples in appropriate solvents at elevated temperatures. For polyolefins, use 1,2,4-trichlorobenzene or similar high-boiling solvents at temperatures of 160°C or higher to ensure complete dissolution [28]. Sample concentrations typically range from 0.5-2.0 mg/mL depending on detector sensitivity.

Column Selection: Utilize graphitized carbon columns or other ALFS adsorbents such as molybdenum sulphide, boron nitride, or tungsten sulphide. These materials provide the flat surface required for the separation mechanism based on polymer surface area interaction [28].

SGIC Methodology:

- Implement a solvent gradient from weak to strong solvents, typically starting with alkanols (decanol) or ethylene-glycol monobutyl-ether and progressing to trichlorobenzene [28].

- Maintain elevated temperature throughout the system to prevent polymer crystallization.

- Employ appropriate detection, though options are limited for solvent gradient approaches due to compatibility issues with common polymer detectors.

TGIC Methodology:

- Utilize isocratic solvent conditions (typically 1,2,4-trichlorobenzene) with a temperature gradient for desorption.

- Adsorb samples at low temperature (typically 30-50°C) then apply a temperature ramp to elute species based on branching content.

- Employ infrared detection for concentration measurement and comonomer quantification [28].

Two-Dimensional Techniques: For comprehensive characterization, combine SGIC with GPC/SEC in a two-dimensional setup, where the first dimension separates by chemical composition and the second by molecular weight [28]. This approach overcomes detector limitations in SGIC while providing orthogonal characterization.

Table 2: Comparison of Techniques for Chemical Composition Distribution Analysis

| Parameter | TGIC | SGIC | Crystallization Techniques (TREF/CEF) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Separation Mechanism | Temperature gradient with isocratic elution | Solvent gradient at constant temperature | Crystallization/elution based on crystallizability |

| Range of Comonomer Analysis | Down to ~50% octene mol | 0% to 100% comonomer incorporation | Limited to semicrystalline polymers (~<20% comonomer) |

| Detection Compatibility | Compatible with IR, viscometry, light scattering | Limited detector compatibility | Compatible with IR detection |

| Analysis Time | Moderate | Short | Long |

| Co-crystallization Effects | Not susceptible | Not susceptible | Susceptible |

Applications and Data Interpretation

SGIC and TGIC find particular utility in characterizing complex polyolefin copolymers, especially those with low crystallinity that cannot be analyzed by traditional crystallization-based techniques like TREF or CEF [28]. These include ethylene-propylene copolymers, ethylene propylene diene monomer (EPDM) resins, olefin block copolymers, and other elastomeric materials [28]. The techniques provide a linear calibration between elution volume/temperature and comonomer content, enabling quantitative determination of short-chain branching distribution.

When analyzing TGIC or SGIC data, the chemical composition distribution is represented as a plot of detector response versus elution volume or temperature, which can be correlated with branch frequency through appropriate calibration. For ethylene-octene copolymers, for example, a linear relationship exists between octene mole percentage and elution temperature [28]. The shape of the distribution reveals the homogeneity of comonomer incorporation, with narrow distributions indicating uniform branching and broad or multimodal distributions suggesting multiple compositional populations. For polypropylene-based systems, the separation behavior is more complex, with ethylene-rich copolymers separating by adsorption (TGIC mechanism) while propylene-rich copolymers separate by crystallization (TREF mechanism), resulting in a U-shaped calibration curve [28].

Comparative Analysis and Technique Selection

Side-by-Side Technique Comparison

GPC/SEC, SGIC, and TGIC offer complementary information about polymer structure, each with distinct strengths and applications. GPC/SEC remains the premier technique for molecular weight distribution analysis, providing critical parameters that influence processing behavior and mechanical properties. SGIC and TGIC excel in chemical composition distribution analysis, particularly for polyolefins with low crystallinity that challenge traditional crystallization-based methods. The selection between these techniques depends on the specific polymer characteristics and the analytical information required.

SGIC offers the broadest range of comonomer analysis, capable of characterizing ethylene copolymers across the entire composition range from 0% to 100% comonomer incorporation [28]. However, it faces limitations in detector compatibility due to the solvent gradient. TGIC, while covering a narrower range down to approximately 50% comonomer content, offers superior detector compatibility with isocratic conditions that support IR, viscometer, and light scattering detection [28]. Both gradient techniques overcome the co-crystallization effects that can complicate TREF and CEF analyses, providing more accurate characterization of complex multi-component resins.

Table 3: Comprehensive Comparison of Polymer Characterization Techniques

| Analytical Aspect | GPC/SEC | TGIC | SGIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Separation Basis | Hydrodynamic volume/size | Chemical composition (branching) | Chemical composition (branching) |

| Key Measured Parameters | Molecular weight averages, MWD | Chemical composition distribution | Chemical composition distribution |

| Optimal Application Range | All soluble polymers | Semicrystalline to amorphous polyolefins | Full range of polyolefin copolymers |

| Advanced Detection Options | Light scattering, viscometry, IR | IR, viscometry (isocratic conditions) | Limited by solvent gradient |

| Polymer Architecture Insights | Branching through intrinsic viscosity | Comonomer distribution homogeneity | Comonomer distribution across full range |

| Limitations | No direct composition information | Limited to ~50% comonomer content | Detector compatibility issues |

Integrated Workflow for Comprehensive Polymer Characterization

For complete structural analysis of complex polymers, an integrated approach combining these techniques provides the most comprehensive characterization. Two-dimensional chromatography, which couples a composition-based separation (SGIC or TGIC) with a size-based separation (GPC/SEC), represents the most powerful approach for characterizing complex polymers, revealing how chemical composition varies with molecular weight [28]. This 2D approach has been successfully applied to ethylene-propylene copolymers, EPDM resins, high-impact polypropylene, and olefin block copolymers [28].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision process for selecting appropriate characterization techniques based on polymer properties and analytical requirements:

Diagram 1: Technique selection workflow for polymer characterization

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of these chromatographic techniques requires specific materials and reagents optimized for each methodology. The following table details essential research reagent solutions for GPC/SEC, SGIC, and TGIC analyses:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Polymer Chromatography

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Technique Application |

|---|---|---|

| Graphitized Carbon Columns | ALFS adsorbent for chemical composition separation | SGIC, TGIC |

| Polymer-Based GPC Columns | Size exclusion separation with wide pH/temperature stability | GPC/SEC |

| Silica-Based GPC Columns | Size exclusion separation with high pressure stability | GPC/SEC |

| 1,2,4-Trichlorobenzene | High-temperature solvent for polyolefin dissolution | GPC/SEC, TGIC |

| Decanol/Ethylene-glycol monobutyl-ether | Weak solvents for SGIC gradient initiation | SGIC |

| Narrow Dispersity Polystyrene/Polyethylene Standards | System calibration and column performance verification | GPC/SEC |

| Nitrogen Purging Systems | Prevent oxidative degradation during sample preparation | GPC/SEC (high-temperature) |

| Infrared Detectors (IR4, IR6) | Concentration detection and chemical composition monitoring | GPC/SEC, TGIC |

| Light Scattering Detectors | Absolute molecular weight determination | GPC/SEC |

| Viscometer Detectors | Branching analysis and intrinsic viscosity measurement | GPC/SEC, TGIC |

The selection of appropriate columns is particularly critical for successful analyses. Polymer-based GPC columns offer advantages for high-temperature applications and when combining multiple columns to extend the molecular weight separation range, while silica-based columns provide higher pressure stability and excellent resolution in narrow molar mass ranges [29]. For SGIC and TGIC, graphitized carbon columns with specific surface properties are essential for achieving separation based on chemical composition rather than molecular size [28].

GPC/SEC, SGIC, and TGIC represent powerful and complementary tools in the polymer characterization toolkit, each providing unique insights into different aspects of macromolecular structure. GPC/SEC remains the undisputed gold standard for molecular weight distribution analysis, offering versatile detection options and well-established methodologies. For chemical composition distribution analysis, particularly for complex polyolefin copolymers and elastomers, SGIC and TGIC provide capabilities that extend beyond traditional crystallization-based techniques, enabling characterization of polymers with low crystallinity that were previously challenging to analyze.

The selection of the appropriate technique depends fundamentally on the specific analytical question being addressed. For molecular weight parameters, GPC/SEC is the obvious choice. For composition analysis of semicrystalline to amorphous polymers, TGIC offers robust performance with excellent detector compatibility, while SGIC covers the broadest composition range. For the most complex polymers requiring complete structural elucidation, two-dimensional approaches combining these techniques provide the most comprehensive characterization. As polymer systems continue to grow in complexity through advanced catalyst technologies and manufacturing processes, these chromatographic methods will remain essential tools for understanding structure-property relationships and driving innovation in polymer science and technology.

In the field of polymer science, understanding the intricate relationship between a polymer's structure and its final properties is paramount. Spectroscopic techniques provide the essential tools to unravel these structural details, with Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy serving as two of the most fundamental methods. While both techniques probe molecular characteristics, they deliver distinct and complementary information. FTIR spectroscopy excels in identifying the functional groups and chemical bonds present within a polymer, essentially providing a molecular fingerprint. In contrast, NMR spectroscopy offers deeper insights into the precise chemical structure, including the configuration of monomer units along the polymer chain, known as tacticity. This objective comparison guide delves into the operational principles, specific applications, and experimental protocols for using these two techniques, providing researchers and scientists with the data necessary to select the appropriate method for their specific characterization challenges.

The selection of analytical techniques is critical because polymers can be complex, varying in their chemical makeup, crystallinity, and physical states. As outlined in Table 1, no single method provides a complete picture; a combination is often required for comprehensive characterization [1]. FTIR and NMR primarily address chemical characteristics, with NMR also providing some information on molecular behavior in solvents. This guide focuses on their unique and overlapping roles in elucidating polymer structure.

Table 1: Common Analytical Techniques for Polymer Characterization

| Analytical Technique | Chemical Bonds | Intra- and Intermolecular Interactions | MW Distribution | Solvent Properties | Thermal Behavior | Bulk Structure | Bulk Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMR (liquid) | X | X | X | ||||

| FTIR | X | X | |||||

| Raman | X | X | |||||

| Mass Spectrometry | X | ||||||

| SEC/GPC | X | X |

FTIR Spectroscopy: Functional Group Identification

Principles and Applications

FTIR spectroscopy operates on the principle that molecules absorb specific frequencies of infrared light that are characteristic of their chemical structure and functional groups [31]. When a polymer sample is exposed to IR radiation, the absorbed energy causes covalent bonds to vibrate—stretch, bend, or wag—at resonant frequencies. The resulting spectrum is a plot of absorbed energy versus wavelength, serving as a unique molecular fingerprint that reveals the chemical identity of the sample [31]. A key strength of FTIR is its ability to analyze a wide range of sample forms, including solids, liquids, and gases, with minimal preparation, especially when using techniques like Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) [32] [31].

In polymer characterization, FTIR is indispensable for several applications. It is the primary tool for identifying general polymer classes and for contamination analysis by comparing spectra against reference libraries [5]. It is also widely used to monitor the progress of polymerization reactions by tracking the disappearance of monomer peaks and the emergence of polymer peaks [33]. Furthermore, FTIR can probe polymer degradation by identifying new functional groups formed during photo-aging or thermal breakdown, and it can assess the crystallinity of materials by examining specific regions of the spectrum [31].

Key Experimental Protocol: ATR-FTIR for Polymer Identification

Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) is one of the most common FTIR sampling techniques for polymers due to its simplicity and minimal sample preparation [32]. The following protocol outlines a standard procedure for identifying an unknown polymer solid:

- Instrument and Material Setup: Ensure the FTIR spectrometer is calibrated and the ATR crystal (commonly diamond) is clean. The essential research reagents are a solvent for cleaning (e.g., isopropanol) and the unknown polymer sample.

- Sample Preparation: If the polymer is a large solid, flatten it to ensure good contact with the ATR crystal. A homogeneous film or a small, flat piece is ideal. No other processing is necessary.

- Background Measurement: Collect a background spectrum with no sample on the ATR crystal to account for atmospheric contributions.

- Data Acquisition: Place the polymer sample firmly onto the ATR crystal to ensure intimate contact. Acquire the IR spectrum over a standard wavenumber range (e.g., 4000-600 cm⁻¹).

- Spectral Analysis: Interpret the resulting spectrum by identifying key absorption bands and their corresponding functional groups. Compare the spectrum to a database of known polymer spectra for definitive identification.

Table 2: Key FTIR Absorption Bands for Common Polymers

| Polymer | Key Functional Group(s) | Characteristic Absorption Bands (cm⁻¹) | Band Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene (PE) | CH₂ | 2917, 2852, 1472, 718 [34] | Methylene asymmetric & symmetric stretch, bend, and rock |

| Polyamide (Nylon) | N-H, C=O | ~3300, ~1640 [33] | Amide N-H stretch, Amide C=O stretch (Amide I) |

| Polyester | C=O, C-O | ~1720, ~1100-1300 [33] | Carbonyl stretch, C-O-C stretch |

| Polyacrylonitrile (PAN) | C≡N | ~2240 [33] | Nitrile stretch |

NMR Spectroscopy: Determining Polymer Tacticity

Principles and Applications

NMR spectroscopy exploits the magnetic properties of certain atomic nuclei, such as ¹H (proton) and ¹³C (carbon-13). When placed in a strong magnetic field, these nuclei can absorb and re-emit electromagnetic radiation in the radiofrequency range [33]. The precise frequency at which a nucleus resonates—its chemical shift—is exquisitely sensitive to its local chemical environment. This allows NMR to distinguish between atoms that are part of different functional groups or that have different spatial arrangements. For polymers, this capability is crucial for determining tacticity, which refers to the stereochemical arrangement of asymmetric centers along the polymer backbone [33]. For example, in polymers like polypropylene, tacticity (isotactic, syndiotactic, or atactic) fundamentally influences crystallinity, mechanical strength, and thermal properties.

The applications of NMR in polymer science extend far beyond tacticity. It is the definitive technique for determining monomer ratios in copolymers and for elucidating the chemical structure of repeat units [5] [33]. NMR is also used to investigate polymer dynamics and molecular motion, analyze end-groups to understand chain termination mechanisms, and measure the degree of branching in polymers like polyethylene [5] [33]. A key advantage of NMR is its capability to analyze polymers in both solution and the solid state, with solid-state NMR providing insights into the morphology of insoluble polymers [32] [35].

Key Experimental Protocol: ¹H NMR for Tacticity Determination in Polypropylene

Determining the tacticity of a soluble polymer like polypropylene typically involves solution-state ¹H NMR. The following protocol provides a general outline:

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve approximately 5-10 mg of the polymer in 0.5-1 mL of a deuterated solvent (e.g., deuterated chloroform, CDCl₃). The use of a deuterated solvent is crucial to provide a signal for the spectrometer's lock system and to avoid a large interfering signal from protonated solvents.