Optimizing Polymer Molecular Weight Distribution: Advanced Strategies for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

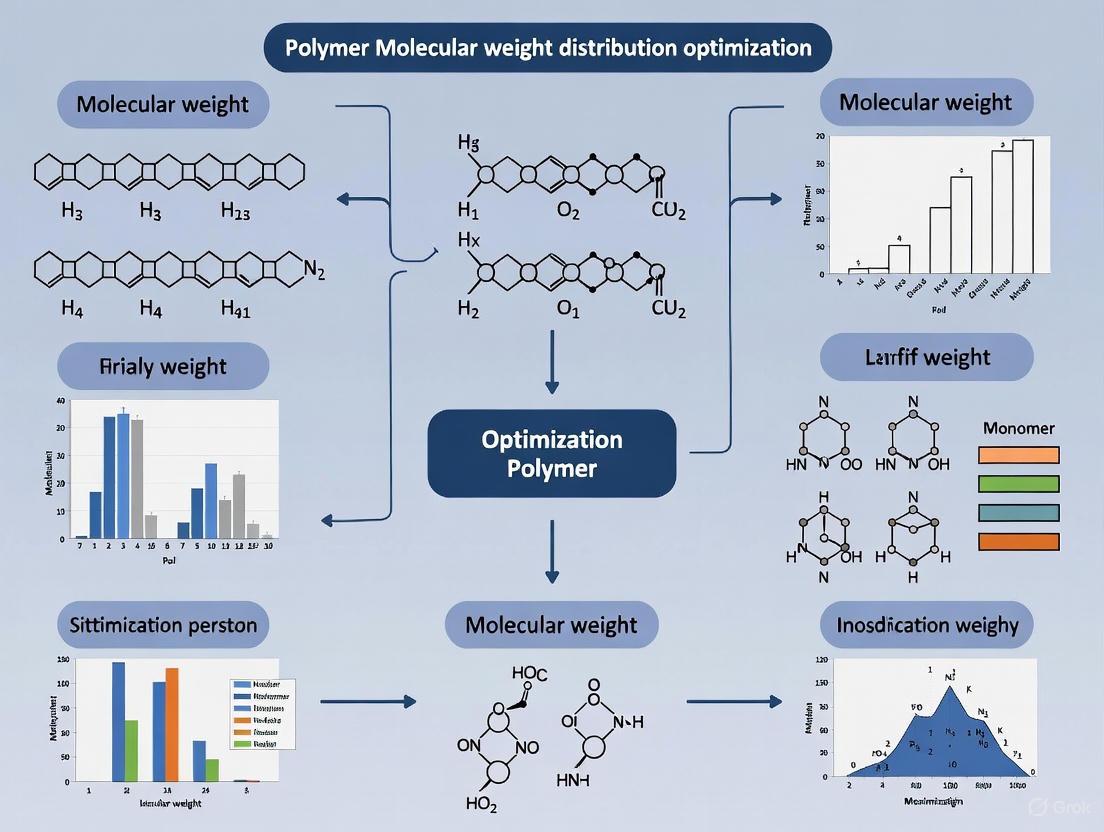

This article provides a comprehensive overview of advanced strategies for optimizing polymer molecular weight distribution (MWD), a critical parameter governing the properties and performance of polymeric materials in biomedical applications.

Optimizing Polymer Molecular Weight Distribution: Advanced Strategies for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of advanced strategies for optimizing polymer molecular weight distribution (MWD), a critical parameter governing the properties and performance of polymeric materials in biomedical applications. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles linking MWD to material properties, innovative synthesis and computational methodologies, practical troubleshooting for common processing challenges, and state-of-the-art validation techniques. By integrating insights from recent advances in flow chemistry, molecular dynamics simulations, and AI-driven optimization, this review serves as a strategic guide for the precise design of polymer systems to enhance drug delivery, biomaterial performance, and therapeutic efficacy.

The Critical Role of Molecular Weight Distribution in Polymer Properties and Performance

In polymer chemistry, the Molecular Weight Distribution (MWD), also known as the molar mass distribution, describes the relationship between the number of moles of each polymer species and its molar mass [1]. Unlike small molecules, polymer samples consist of chains of varying lengths, making MWD a fundamental characteristic. This distribution is intrinsically related to critical material properties, including processability, mechanical strength, and morphological behavior [2] [3]. For researchers aiming to optimize polymer materials for specific applications, such as drug delivery systems or biocompatible materials, a precise understanding and control of MWD is essential [2].

Key Metrics and Their Significance

Polymer molecular weight is not described by a single value but by several averages, each providing different information about the distribution. The most common averages and their significance for troubleshooting are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Molecular Weight Averages and Their Significance

| Average | Mathematical Definition | Physical Significance & Measurement | Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number Average (Mₙ) | ( Mn = \frac{\sum Ni Mi}{\sum Ni} ) [1] | Represents the simple arithmetic mean. Sensitive to the total number of molecules. Measured by techniques like osmometry and end-group analysis [1] [4]. | Low Molecular Weight Species [4] |

| Weight Average (M𝓌) | ( Mw = \frac{\sum Ni Mi^2}{\sum Ni M_i} ) [1] | Weights molecules by their mass. Sensitive to larger, heavier chains. Determined by static light scattering and small-angle neutron scattering [1] [4]. | High Molecular Weight Species [4] |

| Z-Average (M𝓏) | ( Mz = \frac{\sum Ni Mi^3}{\sum Ni M_i^2} ) [1] | A higher moment average, emphasizing the very largest molecules. Measured by sedimentation equilibrium in an analytical ultracentrifuge [1] [4]. | Very High Molecular Weight Species / Tail of Distribution [4] |

| Viscosity Average (Mᵥ) | ( Mv = \left[ \frac{\sum Mi^{1+a} Ni}{\sum Mi N_i} \right]^{1/a} ) [1] | Derived from viscosity measurements and dependent on the solvent-polymer system via the Mark-Houwink parameter 'a' [1]. Obtained from viscosimetry [1]. | Dependent on Polymer-Solvent System [1] |

The relationship between these averages for a typical polymer sample is consistent: Mₙ < Mᵥ < M𝓌 < M𝓏 [1]. The ratio of M𝓌 to Mₙ is known as the Polydispersity Index (PDI) or dispersity, which is a critical parameter indicating the breadth of the MWD [1] [4]. A PDI of 1 indicates a perfectly uniform (monodisperse) polymer, while higher values indicate a broader distribution. For example, an ideal living polymerization gives a PDI of 1, whereas an ideal step-growth polymerization gives a PDI of 2 [1]. In commercial polymers, PDI can be much higher, such as in certain polyethylenes where it exceeds 10 to balance processability and strength [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Successful MWD analysis and control relies on specific reagents and instruments. The following table details key items for a research laboratory.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for MWD Analysis

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) / Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) System | The primary technique for MWD measurement. It separates polymer molecules by their hydrodynamic volume in solution, allowing for the determination of Mₙ, M𝓌, M𝓏, and PDI [1] [4]. |

| Polymer Standards (Narrow MWD) | Crucial for calibrating SEC/GPC systems. These standards with known, narrow MWD allow for the correlation of retention time with molecular mass [1]. |

| Multi-Angle Laser Light Scattering (MALLS) Detector | A detector used in conjunction with SEC/GPC that provides an absolute measure of molecular weight without relying on polymer standards, based on the intensity of scattered light [1]. |

| Differential Refractive Index (DRI) Detector | A common, concentration-sensitive detector for SEC/GPC that measures the change in refractive index of the eluent [1]. |

| Viscometer (for Solution Viscosity) | Used to measure the intrinsic viscosity of a polymer solution, which can be related to molecular weight via the Mark-Houwink equation [1] [4]. |

| Solvents (HPLC Grade) | High-purity solvents are essential for preparing polymer solutions for SEC/GPC and other analyses to avoid interference from impurities. |

| Chain Transfer Agents | Small molecules used during polymerization to control and reduce molecular weight by transferring the active chain end to a new molecule [2]. |

| Tubular Flow Reactor | An advanced tool for precision polymer synthesis, enabling the construction of targeted MWDs by accumulating narrow MWD polymers made under computer-controlled conditions [3]. |

Experimental Protocol: Determining MWD by SEC/GPC with Triple Detection

This protocol outlines a robust methodology for determining the complete molecular weight distribution of a homopolymer sample using a Size Exclusion Chromatography system equipped with multiple detectors, which is considered a gold-standard approach.

Materials and Equipment

- Polymer Sample: Homopolymer, free of additives like plasticizers, fillers, or large amounts of stabilizers that could affect rheology or chromatography [5].

- SEC/GPC Instrument: Configured with an isocratic pump, autosampler, column oven, and a series of columns with appropriate pore sizes for the polymer's molecular weight range.

- Detectors: A triple-detector array is ideal, typically comprising a Differential Refractive Index (DRI) detector, a Multi-Angle Laser Light Scattering (MALLS) detector, and a Differential Viscometer.

- Solvent: HPLC-grade solvent that is a good solvent for the polymer at room temperature (e.g., THF for many synthetic polymers). The solvent must be filtered and degassed.

- Calibration Standards: Narrow dispersity polymer standards of known molecular weight, matching the polymer under investigation.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Prepare polymer solutions at a concentration of 1-2 mg/mL in the chosen solvent. Filter the solutions through a 0.45 µm (or smaller) pore size filter (e.g., PTFE) into an HPLC vial to remove any dust or microgels.

- System Equilibration: Start the solvent flow through the SEC columns and detectors. Allow the system to equilibrate until a stable baseline is achieved on all detectors. This may take several hours.

- Calibration (Optional for MALLS): If using a conventional calibration curve, inject the series of narrow standards and record their retention times to create a log(M) vs. retention time calibration curve. Note: This step is not required for an absolute molecular weight measurement when using a MALLS detector.

- Sample Injection: Inject a fixed volume (typically 50-100 µL) of the filtered polymer solution into the SEC system.

- Data Collection: Collect data from all detectors (DRI, MALLS, Viscometer) simultaneously as the sample elutes.

- Data Analysis:

- The DRI detector provides the concentration of polymer at each elution volume slice.

- The MALLS detector measures the absolute molecular weight (M) at each slice directly from the scattered light intensity.

- The Viscometer measures the intrinsic viscosity at each slice.

- Software combines these signals to calculate Mₙ, M𝓌, M𝓏, PDI, and the full distribution curve.

The workflow below illustrates the logical sequence and data flow for this characterization method:

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My SEC/GPC analysis shows a double peak or significant tailing. What could be the cause?

- A: A double peak can indicate a bimodal distribution, often resulting from multiple active catalytic sites in the polymerization (e.g., Ziegler-Natta catalysts) or incomplete mixing in a reactor [2]. Tailing on the high molecular weight side can suggest aggregation or microgel formation in the solution. Ensure your sample is fully dissolved and filtered. Tailing on the low molecular weight side may indicate adsorption of polymer onto the SEC columns.

Q2: I am trying to synthesize a polymer with a narrow MWD, but my PDI remains high. How can I improve this?

- A: High PDI often stems from slow or incomplete initiation, side reactions (such as chain transfer to polymer or solvent), or non-isothermal reaction conditions [1] [2]. To improve dispersity:

- Ensure your initiator is highly active and rapidly consumed.

- Use purified reagents to minimize chain transfer agents.

- Maintain a constant, controlled reaction temperature.

- Consider using a controlled/living polymerization technique.

Q3: Why is controlling the entire Molecular Weight Distribution more important than just targeting Mₙ and M𝓌?

- A: Two polymers can have identical Mₙ and M𝓌 but vastly different MWDs (e.g., one broad and one bimodal), leading to different mechanical and processing properties [6] [3]. The high molecular weight tail (influenced by M𝓏) significantly affects melt elasticity and toughness, while the low molecular weight fraction can act as a plasticizer. For consistent and optimized performance, the entire distribution must be controlled.

Q4: Can I determine MWD from rheological data?

- A: Yes, it is possible to estimate MWD from dynamic mechanical frequency sweep data (G' and G") using rheological models like the "double reptation" mixing rule [5]. This method is particularly sensitive to high molecular weight components and can be useful as a complementary technique to SEC. However, it requires accurate material parameters and is sensitive to factors like long-chain branching, which can invalidate the results [5].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Table 3: Common MWD Experimental Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor SEC/GPC Resolution | Inappropriate column pore size; Column degradation; Flow rate too high. | Use a column set with a broad pore size range; Clean or replace columns; Optimize flow rate for better separation. |

| High PDI in Synthesis | Inefficient initiation; Broad temperature profile; Chain transfer reactions. | Use faster initiators; Improve reactor temperature control; Identify and minimize chain transfer sources. |

| Low Mₙ, High PDI | Excessive chain transfer agent; High initiator concentration; Depletion of monomer. | Reduce chain transfer agent or initiator concentration; Ensure constant monomer feed in semi-batch processes [6]. |

| MWD Results Differ from Expected | Imperfect mixing in reactor; Model-plant mismatch; Sensor delays in feedback control. | For lab reactors, use state estimators (e.g., Extended Kalman Filter) to compensate for measurement delays and update control policies [6]. |

| Inability to Achieve Target MWD Shape | Arbitrary MWD shaping methods; Multimodal blends. | Implement a computer-controlled tubular flow reactor designed for Taylor dispersion, which allows for the precise "building" of a target MWD by accumulating narrow MWD fractions [3]. |

The properties of a polymer are intrinsically related to its Molecular Weight Distribution (MWD). This fundamental structural characteristic simultaneously impacts a material's processability, mechanical strength, and morphological phase behavior [7]. The MWD represents the spectrum of different chain lengths within a polymer sample, and its control is a central challenge in polymer science.

The presence of low molecular weight (LMW) polymers provides ease of processing, while high molecular weight (HMW) components impart high mechanical strength and impact resistance [7] [8]. This structure-function relationship is of critical importance for applications ranging from commodity objects to emerging areas like 3D printing and advanced drug delivery systems [7] [9]. Through precise tuning of the MWD, an ideal balance of material properties and processability can be achieved, enabling the design of polymers for specific applications.

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Researchers often encounter specific issues when attempting to control or characterize MWD. The following table addresses frequent experimental challenges.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for MWD-Related Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution | Related Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor Processability (e.g., high viscosity, difficult extrusion) | Excessive High Molecular Weight (HMW) fraction leading to high entanglement density [8]. | Implement controlled rheology via reactive extrusion with peroxides to induce selective chain scission and narrow the MWD [10]. | Fiber spinning, injection molding [10]. |

| Insufficient Mechanical Strength | Low molecular weight (LMW) fraction is too high, or HMW content is insufficient [7] [8]. | Synthesize trimodal or bimodal MWDs; a small increase in HMW backbone can significantly increase crystallinity and strength [8]. | High-strength pipelines, fibers [8]. |

| Inconsistent Drug Release Profiles from polymeric carriers [9]. | Complex interplay between polymer degradation, drug diffusion, and MWD not properly accounted for. | Use model-based optimization of the MWD and particle size distribution to achieve the desired release profile [9]. | Controlled Drug Delivery Systems (DDS) [9]. |

| Unintended Crystalline Morphology (e.g., irregular spherulites, lamellae). | Molecular segregation during crystallization, where different MW fractions crystallize at different rates and locations [11]. | Control cooling rates and consider the spatial molecular weight distribution; HMW components often nucleate first [11]. | Material design for specific thermal/mechanical properties [11]. |

| Difficulty Achieving Target MWD in synthesis. | Lack of precision in traditional batch polymerization methods. | Employ a computer-controlled automated flow reactor to produce narrow MWD batches that accumulate into a targeted, complex MWD [7] [12]. | Fundamental material studies, advanced material tuning [7]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is a broad MWD sometimes desirable in industrial applications? A broad MWD is a staple in industry because it provides an ideal balance of properties. The LMW fractions act as an internal plasticizer, enhancing processability and reducing energy consumption during extrusion or molding. Meanwhile, the HMW fractions form entanglements that provide the mechanical strength, toughness, and environmental stress crack resistance required in the final product. For example, some polyethylenes produced with Phillips catalysts have a dispersity (Ð) >10 for this reason [12].

Q2: How does MWD specifically affect the crystallization behavior of polymers? MWD drives distinct crystalline structures through a phenomenon called molecular segregation. During crystallization, polymer chains of different lengths do not crystallize uniformly. HMW components, with their higher entanglement density and slower relaxation, often nucleate first but grow more slowly. LMW components, with high chain mobility, can later form thicker extended-chain lamellae at the edges of these structures. This cooperative crystallization leads to complex textures like nested spherulites or shish-kebabs under flow, ultimately determining the material's macroscopic properties [11] [8].

Q3: What are the main conjugation methods for attaching functional molecules (like peptides) to polymers, and how does MWD play a role? The two primary methods are post-conjugation (onto pre-formed nanoparticles) and pre-conjugation (synthesizing and purifying peptide-polymer conjugates before nanoparticle formation) [13]. The MWD of the parent polymer is critical because it can affect the conjugation efficiency and the final nanoparticle's properties. A wide MWD in a maleimide-endcapped polymer, for instance, can lead to inconsistent peptide loading and heterogeneous nanoparticle populations, potentially affecting targeting efficacy in drug delivery applications [13].

Q4: How can Machine Learning (ML) assist in MWD research? ML serves as a powerful tool to uncover the complex relationships between synthesis conditions, MWD, and final material properties. It can predict polymer properties based on structural descriptors, reversibly design polymer structures for targeted functions, and optimize processing parameters to achieve specific MWDs. This data-driven approach helps accelerate the discovery and design of novel polymers by navigating the vast combinatorial space of possible compositions and structures [14].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Designing Tailored MWDs using an Automated Flow Reactor

This protocol enables the synthesis of polymers with pre-defined MWD shapes, moving beyond simple dispersity control [7] [12].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Tubular Flow Reactor: Computer-controlled system for precise reagent pumping and temperature control.

- Living Polymerization Initiators: Chemistry-dependent (e.g., for Ring-Opening Polymerization of lactide, anionic polymerization of styrene, or Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization).

- Monomer Solutions: High-purity monomers in appropriate solvents.

- Taylor Dispersion Tracer: A UV-absorbing initiator or small molecule to characterize flow profile.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Reactor Design: Select a tubular reactor with radius (R), length (L), and establish a flow rate (Q) based on the design rule that the "plug volume" is proportional to ( R^2 \sqrt{LQ} ) [12]. This ensures narrow residence time distribution via Taylor dispersion.

- WD Target Definition: Input the desired MWD profile (e.g., broad, skewed, bimodal) into the control software.

- Flow Program Calculation: The software a-priori calculates the required flow rate program for the initiator and monomer streams to produce a series of narrow MWD polymer batches with specific molecular weights.

- Synthesis and Accumulation: The flow reactor executes the program, synthesizing these sequential batches. They are collected in a single vessel, where they accumulate to build up the final, targeted MWD.

- Validation: Characterize the final product using Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) to verify the achieved MWD matches the design.

Protocol: Optimizing Drug Release via MWD and Particle Size Control

This model-based approach optimizes biodegradable polymer carriers (e.g., PLGA) for a desired drug release profile [9].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Formulate Degradation-Diffusion Model: Develop a mathematical model that couples:

- Hydrolytic Degradation Kinetics: Describe the cleavage of polymer backbone esters, which reduces the average molecular weight over time.

- Drug Diffusion: Model the diffusion of dissolved API through the polymer matrix, using a time-dependent diffusion coefficient that increases as the polymer degrades and becomes more porous.

- Parameter Estimation: Fit the unknown model parameters to experimental drug release data from a known system.

- Define Optimization Goal: Specify the target drug release profile (e.g., sustained release over 3 weeks with minimal burst release).

- Run Multi-Parametric Optimization: Calculate the optimal MWD and particle size distribution of the polymer carrier population that minimizes the difference between the model's prediction and the target release profile.

- Synthesize and Validate: Produce the optimized carrier system and validate its performance in vitro.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Advanced MWD Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in MWD Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Controlled Polymerization Initiators (e.g., for ROP, Anionic, ROMP) | Enables synthesis of polymers with narrow MWD building blocks, which are essential for constructing complex designed MWDs [7] [12]. | Chemistry must be living/controlled to maintain narrow dispersity during flow synthesis. |

| Peroxides (e.g., DTBPH) | Used in controlled rheology to precisely reduce molecular weight and narrow MWD via chain scission during reactive extrusion, improving processability [10]. | Content must be carefully optimized (<600 ppm); excess can cause degradation and property loss. |

| Maleimide-Terminated Polymers (e.g., PCL-PEG-MAL) | Allows for site-specific conjugation of thiol-functionalized molecules (e.g., targeting peptides) via Michael addition for functionalized nanoparticles [13]. | A wide MWD of the parent polymer can lead to inconsistent conjugation and nanoparticle heterogeneity. |

| Computer-Controlled Flow Reactor | The core platform for executing precise "design-to-synthesis" protocols, producing a quasi-infinite number of polymer batches to build any targeted MWD [7] [12]. | Requires understanding of fluid mechanics (Taylor dispersion) to achieve narrow residence time distribution. |

| Multi-Detector GPC/SEC System | The primary analytical tool for determining MWD, average molecular weights (Mn, Mw), and for analyzing polymer-biomolecule conjugates [13]. | Critical for validating synthesis outcomes and characterizing polymer degradation. |

Property Relationships and Data Synthesis

Understanding the quantitative impact of MWD on material properties is crucial for design. The following table summarizes key relationships.

Table 3: Quantitative and Qualitative Effects of MWD on Polymer Properties

| MWD Characteristic | Effect on Processability | Effect on Mechanical & Physical Properties | Demonstrated Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broad/Polydisperse MWD | Improved; LMW fraction acts as a processing aid [7] [12]. | Good balance; HMW provides strength, but LMW can create weak points. | Industrial polyolefins (e.g., Phillips PE, Ð>10) [12]. |

| Narrow MWD (Low Ð) | Can be difficult; high melt viscosity and elastic effects [10]. | High strength but can be brittle; uniform structure. | Controlled-rheology PP for stable fiber spinning [10]. |

| Bimodal MWD | Good; LMW component enhances flow [8]. | Excellent; synergistic effect combines strength from HMW and rigidity from LMW [8]. | High-grade pipelines (PE100) [8]. |

| Trimodal MWD | Tunable; can be optimized for specific processes [8]. | Superior to bimodal; addition of ultra-HMW component enhances crack growth and wear resistance [8]. | High-strength fibers, protective products, PE100RC pipes [8]. |

| LMW Fraction Increase | Increases processability, reduces viscosity [7] [10]. | Decreases mechanical strength, impact resistance, and can slow crystallization by causing entanglements [8]. | |

| HMW Fraction Increase | Decreases processability, increases viscosity and melt strength [8] [10]. | Increases mechanical strength, toughness, and crack resistance [7] [8]. |

Influence of MWD on Crystalline Texture and Morphology in Polymers

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why do I observe multiple crystal morphologies (e.g., both thin lamellae and thicker spherulites) in my isothermally crystallized polydisperse polymer sample?

This is a classic manifestation of molecular segregation driven by a broad Molecular Weight Distribution (MWD). In a polydisperse system, chains of different lengths do not co-crystallize uniformly. High Molecular Weight (HMW) components, with their high entanglement density and slow relaxation, often nucleate first but grow slower, potentially forming less ordered or thinner lamellae. Low Molecular Weight (LMW) components, with high chain mobility, can later crystallize into more ordered, thicker lamellae at the edges of structures initiated by HMW chains. This leads to composite textures, such as nested spherulites with thin-lamellar dendrites in the interior surrounded by thicker lamellae at the periphery [11].

Q2: How does MWD affect the formation of shish-kebab structures under flow or shear conditions?

Under flow fields, HMW and LMW components play distinct, synergistic roles. The elongated HMW chains, due to their long relaxation times, are more prone to form the central oriented "shish" core. The LMW components, with their higher mobility, can then crystallize rapidly onto this core as folded-chain "kebabs". A broad MWD ensures the presence of both populations: HMW for stable nucleation under flow and LMW for rapid growth of the kebabs [11].

Q3: My polymer sample has the same chemical composition but exhibits different crystal polymorphs under identical crystallization conditions. Could MWD be the cause?

Yes. The propensity to form different crystal polymorphs can be strongly influenced by MWD. HMW and LMW fractions within the same sample can have different crystallization pathways and kinetics. For instance, LMW components might more readily form extended-chain crystals or specific polymorphs due to their reduced ability to fold under given undercooling, while HMW components might favor a different polymorph due to kinetic constraints like entanglement [11].

Q4: What are the best practices for designing a polymer blend to achieve a desired crystalline texture?

The key is to treat the MWD as a design parameter, not just a single average value.

- For a uniform texture: Use a polymer with a narrow MWD.

- For a complex, composite texture: Create a bimodal or broad MWD blend. Systematically blend HMW and LMW fractions. The HMW fraction will influence nucleation density and initial structure, while the LMW fraction will dictate the final lamellar thickening and overall crystallinity. The spatial distribution of these fractions (MWSD) ultimately dictates the final crystalline texture [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Crystalline Morphology Between Batches

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Batch-to-batch variation in spherulite size and shape. | Variation in the breadth or shape of the MWD between polymer batches. | Characterize MWD: Use Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) to verify the MWD of each batch. Fractionate the polymer to narrow the MWD and achieve more consistent results [11]. |

| Lamellar thickness distribution is too broad. | Significant molecular segregation during crystallization. | Optimize crystallization conditions: Slower cooling rates can reduce segregation by allowing chains more time to co-crystallize. Annealing the sample after crystallization can promote more uniform lamellar thickening [11]. |

Issue 2: Failure to Achieve Target Shish-Kebab Morphology Under Shear

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor or no shish formation under applied shear. | Insufficient HMW content to form stable thread-like nuclei. | Increase HMW fraction: Blend in a HMW component to your polymer system. Optimize shear conditions: Ensure sufficient shear rate and duration to elongate the HMW chains [11]. |

| Kebabs are poorly formed or irregular. | Inadequate LMW content or incorrect thermal conditions for kebab growth. | Verify LMW fraction: Ensure the polymer has a sufficient population of LMW chains. Adjust undercooling: After shear, the temperature should be optimal for the LMW chains to crystallize epitaxially on the shish [11]. |

Issue 3: Unpredicted Crystal Polymorph Formation

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Appearance of an unexpected crystal form during isothermal crystallization. | Specific MW fractions within the MWD have a strong propensity for a particular polymorph. | Analyze fractionated material: Separate the polymer into different MW fractions and study the crystallization behavior of each fraction individually. Control nucleation: Use a controlled seed crystal of the desired polymorph to dominate the crystallization process [11]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Investigating MWD-Induced Molecular Segregation in Polymer Blends

This protocol outlines a method to create and characterize the nested crystalline textures resulting from the crystallization of a bimodal MWD blend.

- Objective: To observe the spatial molecular segregation of HMW and LMW components and their resulting distinct crystalline structures.

- Materials:

- HMW polymer fraction (e.g., Mw ~ 100,000 g/mol)

- LMW polymer fraction (e.g., Mw ~ 10,000 g/mol)

- Common solvent (e.g., Toluene, Chloroform)

Procedure:

- Prepare separate solutions of HMW and LMW fractions (e.g., 1% w/v).

- Blend the solutions in a desired mass ratio (e.g., 50:50) and stir thoroughly.

- Drop-cast the blend solution onto a clean glass slide (e.g., a hot plate at 50°C) to create a thin film.

- Immediately transfer the slide to a hot stage under a polarizing optical microscope (POM). Heat to ~30°C above the melting temperature (Tm) for 5 minutes to erase thermal history.

- Rapidly cool to the desired isothermal crystallization temperature (Tc) and observe the crystal growth in real-time.

- After crystallization is complete, quench the sample to room temperature.

- Characterize the morphology using Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) to measure lamellar thicknesses in different regions of the crystalline texture.

Expected Outcome: A crystalline texture where the HMW-rich regions form the initial, inner structure (e.g., thin-lamellar dendrites), while the LMW component crystallizes later at the periphery, forming thicker, extended-chain lamellae [11].

Quantitative Data on MWD Effects

Table 1: Influence of Molecular Weight on Key Crystallization Parameters [11]

| Molecular Weight Fraction | Nucleation Tendency | Crystal Growth Rate | Typical Lamellar Feature | Common Morphology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High (HMW) | High (forms initial nuclei) | Slow (high entanglement) | Thin lamellae, non-integer folds | Internal dendrites, Shish core |

| Low (LMW) | Lower | Fast (high mobility) | Thicker, extended-chain lamellae | Peripheral overgrowth, Kebab |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common MWD-Related Crystallization Problems

| Problem | Diagnostic Tool | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Uncontrolled polymorphism | Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC), Wide-Angle X-Ray Scattering (WAXS) | Fractionate polymer; Use selective nucleating agents. |

| Poor flow-induced crystallization | Rheometry, In-situ SAXS/WAXS | Increase HMW content; Optimize shear rate and temperature. |

| Broad melting range | DSC | Characterize MWD via GPC; Apply successive self-nucleation and annealing (SSA) analysis. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for MWD and Crystallization Studies

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Polymer Fractions (Narrow MWD) | Used as standards or blend components to systematically study the effect of chain length. Essential for creating defined bimodal distributions. |

| Metallocene Catalysts | Provide precise control over polymer microstructure and MWD during synthesis, enabling the creation of tailored polymers for research [15]. |

| Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC/SEC) System | The primary tool for determining the Molecular Weight Distribution (MWD), dispersity (Đ), and average molecular weights of a polymer sample. |

| Polarizing Optical Microscope (POM) with Hot Stage | For real-time observation and imaging of spherulitic growth, crystal morphology, and overall crystalline texture under controlled thermal conditions. |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Allows for nanoscale resolution of crystalline structures, such as measuring lamellar thickness and visualizing shish-kebab formations [11]. |

Experimental Workflow and Causal Relationships

Workflow for MWD-Crystallization Research

Mechanism of Molecular Segregation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does Molecular Weight Distribution (MWD) directly impact the biocompatibility of a biomedical polymer?

The MWD influences biocompatibility by affecting the polymer's degradation profile and how cells interact with the material. A broader MWD can lead to heterogeneous degradation, where smaller chains degrade first, potentially releasing degradation products that trigger inflammatory responses. For instance, in polycarbonate polyurethanes (PCUs), molecular weight, along with hardness and structural composition, directly affects cell viability and adhesion. Studies show that variations in these properties lead to differences in how cells like Normal Human Lung Fibroblasts (NHLF) attach and spread on the material surface [16]. Furthermore, the presence of low molecular weight fractions can sometimes lead to the rapid release of monomers or oligomers that may be cytotoxic or provoke an immune response, underscoring the need for careful MWD characterization to ensure safety [17].

Q2: What are the key experimental parameters to monitor when assessing the degradation profile of a biodegradable polymer?

Degradation is a multifaceted process that should be assessed by monitoring physical, chemical, and mechanical property changes over time. The key parameters are summarized in the table below [18]:

| Assessment Category | Key Parameters to Monitor |

|---|---|

| Physical | Mass loss (Gravimetric analysis), surface morphology (via SEM), surface erosion |

| Chemical | Changes in molecular weight (via SEC/GPC), chemical structure of by-products (via FTIR, NMR, Mass Spectrometry) |

| Mechanical | Tensile strength, storage modulus, elasticity |

It is critical to use multiple complementary techniques. While physical changes like weight loss can infer degradation, only chemical analysis can confirm it by identifying the breakdown products. Relying solely on one method, such as gravimetric analysis, can be misleading as mass loss may be due to dissolution rather than true degradation [18].

Q3: What is the most effective method for controlling the MWD of a polymer during synthesis for a specific application?

Flow chemistry using a computer-controlled tubular reactor has emerged as a powerful protocol for designing targeted MWDs. This chemistry-agnostic method allows for the precise synthesis of polymers with narrow MWDs, which are then accumulated in a collection vessel to build up a specific, pre-determined MWD profile. This represents a "design-to-synthesis" protocol, moving beyond traditional methods that often result in arbitrary MWD shapes. This level of control is crucial for tailoring materials where properties like processability and mechanical strength are intrinsically linked to the MWD [12]. Alternatively, in batch processes, the initial concentration and flow rate of chain transfer agents can be dynamically optimized to manipulate the MWD [19].

Q4: Why is a broad MWD sometimes desirable in biomedical applications, and what are the trade-offs?

A broad MWD can be beneficial because it often enhances material toughness and improves processability. The presence of long polymer chains can entangle to provide mechanical strength, while shorter chains can act as a plasticizer, facilitating easier processing [20] [12]. The key trade-off is the potential for inconsistent degradation behavior. A broad distribution means the polymer does not degrade uniformly; lower molecular weight fractions degrade first, which can lead to an initial burst of degradation products and unpredictable changes in mechanical properties over time. This can be detrimental in applications like controlled drug delivery or tissue engineering, where a consistent and predictable performance is critical [21] [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Polymer Degradation Rates

Problem: The degradation rate of your polymer batch varies significantly between test samples, leading to unreliable data.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Broad or Multimodal MWD | Perform Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) to analyze the MWD. A high polydispersity index (PDI) indicates a broad distribution. | Implement synthesis techniques like flow chemistry to achieve a narrower, more monomodal MWD for consistent degradation [12]. |

| Improper Degradation Media | Verify the pH and ionic strength of the buffer. Confirm the activity and concentration of enzymes if used. | Strictly follow ASTM F1635-11 guidelines for degradation testing. Use a pH of 7.4 or the documented pH for the targeted bodily environment [18]. |

| Inadequate Characterization | Relying only on gravimetric analysis (mass loss). | Employ a multi-pronged characterization approach. Combine gravimetric analysis with SEC to track molecular weight changes and NMR/HPLC to identify by-products [18]. |

Issue 2: Unfavorable Cellular Response to Polymer Implant

Problem: Cell viability tests on your polymer film or scaffold show low viability, or cells fail to adhere and proliferate properly.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Cytotoxic Low-MW Fractions | Extract the polymer with a suitable solvent and analyze the extractables via chromatography and mass spectrometry. Perform cytotoxicity testing on the extracts. | Purify the polymer to remove low molecular weight oligomers and residual monomers. Techniques like temperature rising elution fractionation (TREF) can isolate narrow fractions [21] [17]. |

| Inappropriate Surface Morphology | Use Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to visualize the surface topography that cells are encountering. | Modify the polymer processing or synthesis parameters. For example, blending with another polymer or adding a bioactive coating can improve cell adhesion [17] [16]. |

| Adverse Inflammatory Response | The polymer's degradation products may be causing inflammation. | Analyze the degradation by-products for their biocompatibility. Consider modifying the polymer chemistry to produce more benign metabolites upon hydrolysis or enzymatic cleavage [17] [18]. |

Issue 3: Failure to Achieve Target MWD During Synthesis

Problem: The synthesized polymer's MWD does not match the design parameters, affecting subsequent property testing.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Ineffective Initiator Mixing | In flow reactors, use a UV tracer to check the pulse width and distribution at the reactor outlet. | Ensure proper mixing at the reactor inlet. While static mixers can be used, Taylor dispersion in a properly designed tubular reactor can achieve the necessary "plug-like" flow for narrow MWDs [12]. |

| Uncontrolled Polymerization Kinetics | Monitor reaction kinetics in real-time if possible. Analyze the MWD of samples taken at different reaction times. | Use chain transfer agents to control chain growth and narrow the distribution. For dynamic optimization, manipulate the initial concentration and flow rate of the chain transfer agent [19] [20]. |

| Incorrect GPC/SEC Calibration | Validate your GPC system with narrow dispersity polymer standards. | Always use appropriate calibration standards for accurate MWD measurement. Cross-validate results with other techniques like static light scattering for absolute molecular weights [22]. |

Table 1: Impact of PLA Molecular Weight on Thermal Degradation Kinetics [21]

This data demonstrates how molecular weight influences the energy required for thermal degradation, which is correlated with stability and degradation behavior.

| Sample | Viscosity-Average Molecular Weight (Mv) ×10³ g/mol | Temperature at Max Degradation Rate (Tmax) at 8°C/min | Activation Energy (Eα) Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 92.6 | 357.68 °C | 180 - 240 kJ/mol |

| S2 | 113.0 | 358.30 °C | 180 - 240 kJ/mol |

| S3 | 131.7 | 354.52 °C | 140 - 180 kJ/mol |

Table 2: Biocompatibility and Mechanical Performance of Polycarbonate Polyurethane (PCU) Resins [16]

This table shows the direct relationship between a polymer's properties and its biological performance.

| PCU Resin | Hardness | Key Mechanical Finding | Cytotoxicity (Cell Viability) | Cell Morphology Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronoflex (CF) 65D | 65D | Greater elasticity at high frequencies | >70% | Homogeneous cell distribution, elongated morphology |

| Carbothane (CB) 95A (Lower MW) | 95A | Improved strain recovery | >70% | Cells tended to aggregate and form clusters |

| Carbothane (CB) 95A (Higher MW) | 95A | Improved strain recovery | >70% | Information not specified in source |

Standard Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing In Vitro Degradation of Solid Polymer Formulations

Objective: To evaluate the degradation profile of a solid polymer scaffold or film in simulated physiological conditions [18].

Materials:

- Polymer sample: Pre-weighed and characterized (e.g., dimensions, initial molecular weight).

- Degradation medium: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, pH 7.4) or simulated body fluid, with or without enzymes (e.g., esterases for PLA).

- Incubator: Maintained at 37°C.

- Analytical equipment: Analytical balance, Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC/GPC) system, FTIR, NMR, SEM.

Workflow:

- Pre-degradation Characterization: Record the initial dry mass (W₀), dimensions, and analyze the initial molecular weight and chemical structure via SEC and FTIR.

- Immersion: Immerse samples in degradation medium at a defined surface-area-to-volume ratio. Maintain at 37°C.

- Sampling: At predetermined time points, remove samples from the medium in triplicate.

- Rinsing and Drying: Rinse samples with deionized water and dry to a constant weight.

- Post-degradation Analysis:

- Gravimetric Analysis: Measure dry mass (Wt). Calculate mass loss % = [(W₀ - Wt) / W₀] × 100.

- Molecular Weight Analysis: Use SEC/GPC to determine the change in molecular weight (Mn, Mw) and PDI over time.

- Morphological Analysis: Use SEM to examine surface erosion and cracking.

- By-product Analysis: Use techniques like NMR or HPLC to identify and quantify degradation products in the buffer.

Protocol 2: Tailoring MWD via Flow Chemistry Synthesis

Objective: To synthesize a polymer with a specifically targeted molecular weight distribution using a computer-controlled flow reactor [12].

Materials:

- Tubular flow reactor system: With precise temperature control and computer-controlled pumps.

- Monomer and initiator solutions: Purified and dissolved in an appropriate solvent.

- Collection vessel: For accumulating the polymer product.

- GPC/SEC system: For real-time or offline MWD analysis.

Workflow:

- Reactor Design: Design the tubular reactor (radius, length) based on principles of Taylor dispersion to achieve narrow residence time distribution.

- Protocol Calculation: A-priori calculate the required flow rates and initiator addition profile to build the target MWD in the collection vessel.

- Synthesis Execution: Run the computer-controlled reactor. The system produces a series of polymer populations with narrow, specific molecular weights.

- Accumulation: These discrete populations are accumulated in a single collection vessel, building up the final polymer with the designed MWD.

- Verification: Analyze the final product using GPC/SEC to verify the MWD matches the target design.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for MWD and Degradation Research

| Item | Function | Example Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Chain Transfer Agents | Controls polymer chain growth during synthesis, helping to narrow MWD or control average molecular weight. | Dynamic optimization of MWD in batch polymerization processes [19]. |

| Temperature Rising Elution Fractionation (TREF) | Separates polydisperse polymer into narrow molecular weight fractions for precise study of MW effects. | Obtaining narrow MWD PLA fractions to study the isolated impact of molecular weight on thermal degradation [21]. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (GPC/SEC) | The primary technique for determining the molecular weight distribution of a polymer sample. | Monitoring changes in Mw and PDI throughout a degradation study [18] [22]. |

| Enzymes (e.g., Esterases, Lipases) | Catalyze the enzymatic degradation of polymers, simulating biological breakdown. | Studying the enzymatic degradation rate of polyesters like PLA in vitro [17]. |

| Static Light Scattering (SLS) Detector | Coupled with GPC to determine absolute molecular weight (Mw) and radius of gyration. | Accurately characterizing the molecular parameters of a newly synthesized polymer for biomedical use [22]. |

Advanced Synthesis and Computational Methods for Precise MWD Control

Molecular Weight Distribution (MWD) is a fundamental characteristic that dictates the physical and mechanical properties of polymers. Traditional batch processes often struggle with precise MWD control due to batch-to-batch variability and inconsistent reaction dynamics. Flow chemistry reactors offer a revolutionary solution, enabling unprecedented precision in designing tailored MWDs through enhanced control over reaction parameters such as mixing, temperature, and residence time. This technical support center provides researchers and scientists with the essential knowledge and troubleshooting guidance to harness flow chemistry for advanced polymer MWD optimization.

FAQs: Fundamentals of MWD Control in Flow Reactors

What makes flow chemistry superior to batch processes for tailoring MWDs?

In batch processes, reaction conditions such as concentration and temperature change over time, leading to challenges in controlling the consistency of the MWD. In contrast, flow chemistry involves the continuous feeding of materials, allowing for steady-state conditions where all variables remain constant over time. This enables superior heat and mass transfer, faster and more efficient mixing, and precise control over reaction parameters, resulting in highly reproducible and targeted MWDs [23].

What is the basic principle behind designing a targeted MWD in a flow reactor?

The fundamental principle involves using a computer-controlled flow reactor to produce a series of polymer segments, each with a very narrow MWD. By systematically varying the flow rates to change the residence time or reagent composition, and accumulating the resulting polymer segments in a collection vessel, any targeted MWD profile can be constructed directly from a pre-determined design. This is known as a "design-to-synthesis" protocol [12].

How does "Taylor dispersion" contribute to achieving narrow MWD segments in tubular flow reactors?

Under laminar flow conditions, a parabolic flow velocity profile can cause a wide distribution of residence times, which broadens the MWD. Taylor dispersion counteracts this effect. As a solute pulse travels through a tubular reactor, radial diffusion combined with the radial velocity gradient homogenizes the concentration profile, resulting in a plug-like flow behavior. This ensures that initiator molecules have similar residence times, which is essential for producing the narrow MWD polymer segments needed to build a complex overall distribution [12].

What is "Residence Time" and why is it critical for MWD control?

The residence time is the duration any given molecule spends inside the flow reactor [24]. In polymerization, it directly influences the degree of monomer conversion and the resulting polymer's molecular weight. Precise control over residence time, achieved by adjusting the flow rate and reactor volume, is therefore critical for targeting specific molecular weights and for the sequential synthesis of different polymer segments [12].

When developing a flow process, why is it important to collect product at "steady-state"?

A flow system reaches a steady-state when all variables, such as temperature and reagent feed flow rates, become constant. The material collected at this stage has a product distribution that is truly representative and reproducible. Collecting product before the system reaches steady-state, during the transient start-up phase, will not yield a representative MWD and can lead to inconsistent and non-scalable results [24] [25].

Troubleshooting Guide

This guide addresses common operational challenges in flow chemistry systems for polymer synthesis.

Mixing and Fluid Dynamics Issues

| Problem & Symptoms | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Broadened MWD inconsistent with design predictions. | Laminar flow regime causing a wide residence time distribution (RTD) [12]. | - Implement a static mixing chip to promote homogenization [25].- Leverage Taylor dispersion by optimizing reactor radius, length, and flow rate [12]. |

| Poor Reproducibility and variable conversion between runs. | Inadequate mixing at the reactor inlet, leading to concentration gradients [12]. | - Incorporate a passive static mixer for more efficient mixing at relevant flow rates [25].- Ensure reactor design follows established rules for plug flow behavior [12]. |

System Operation and Blockages

| Problem & Symptoms | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Pressure Spikes or a system shutdown due to over-pressure. | Blockage in the flow path, often from precipitated polymer or solid build-up [24] [25]. | - Use inlet filters to remove particulates from reagents [25].- For known problematic chemistries, consider a dynamically mixed reactor to reduce fouling [24]. |

| Check Valve Failure leading to inaccurate pumping. | Particulate matter damaging the valves or reagents stagnating and crystallizing inside [25]. | - Always use inlet filters [25].- Flush pump heads and check valves regularly with a suitable cleaning solvent (e.g., a 1:1:1 THF:AcOH:water mixture) [25]. |

| Low Conversion of monomer despite sufficient residence time. | - Inadequate mixing.- Electrode fouling (in flow electrochemistry).- Unoptimized flow rate [26]. | - Improve mixing with a static mixer [25].- For electrochemical systems, clean electrodes or use polarity reversal [26].- Reduce flow rate to increase residence time [26]. |

Process Control and Reproducibility

| Problem & Symptoms | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Variability in Results from day to day. | - Fluctuations in ambient temperature affecting reactor performance.- Gradual fouling of the reactor or components.- Slight variations in reagent preparation [23]. | - Allow the system to reach a verifiable steady-state before collection [24].- Implement a regular cleaning and maintenance schedule for the flow path and valves [25].- Standardize reagent preparation and storage protocols. |

Experimental Protocols for MWD Design

Protocol 1: Synthesizing a Polymer with a Bimodal MWD

This protocol outlines the steps to create a polymer with two distinct molecular weight peaks, which can be useful for enhancing material processability and mechanical strength.

- Reactor Setup: Configure a flow reactor system with at least two reagent feed pumps and a computer-controlled outlet valve. A standard coil reactor made of PTFE, PFA, or stainless steel is suitable [27] [25].

- Initial Narrow MWD Segment: Set the flow rates of monomer and initiator streams to target a high molecular weight. Allow the system to reach steady-state (typically 2-3 reactor volumes) [24]. Divert the product stream to Collection Vessel A for a predetermined time (t1).

- Switch to Low MW Segment: Quickly adjust the flow rates (and potentially the monomer-to-initiator ratio) to target a low molecular weight. Once a new steady-state is achieved, divert the product stream to Collection Vessel B for a time (t2).

- Blending: The final bimodal MWD is achieved by precisely blending the contents of Vessel A and Vessel B in the desired mass ratio. The GPC analysis of the blend will show a bimodal distribution.

The following workflow illustrates this multi-step process:

Protocol 2: Refining Reactivity Ratios using an ML-Driven Flow Reactor

This advanced protocol uses machine learning to update classical polymerization models, such as the Mayo-Lewis Equation (MLE), for greater precision [28].

- Autonomous System Setup: Integrate a continuous flow reactor with in-line analytical tools (e.g., IR, RAMAN, or GPC) and an edge server for real-time data processing and ML-driven control [28].

- Initial Data Generation: Run the copolymerization experiment with model monomers (e.g., styrene and acrylate) over a range of conditions, monitoring copolymer composition in real-time.

- ML Model Training & Feedback: Use the collected data to train an ML model that refines the reactivity ratios (rr) in the MLE. The model then suggests new experimental conditions to optimize for a target property.

- Closed-Loop Optimization: The system automatically adjusts the flow rates of comonomers based on the ML model's output, creating a feedback loop that continuously improves the MLE parameters and converges on the desired copolymer composition.

This closed-loop, AI-driven process can be visualized as follows:

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and their functions in flow chemistry reactors for polymer synthesis.

| Item | Function & Role in MWD Control |

|---|---|

| Tubular Coil Reactor | The primary vessel where polymerization occurs. Its dimensions (radius, length) are critical for determining residence time distribution and achieving narrow MWD segments via Taylor dispersion [12]. |

| Static Mixer | A passive mixing device incorporated at the reactor inlet to ensure rapid and homogeneous mixing of initiator and monomer streams, which is essential for simultaneous initiation and narrow MWDs [25]. |

| Back-Pressure Regulator | A device placed towards the end of the flow system that maintains pressure, preventing the evolution of gas bubbles and ensuring a single liquid phase, which is crucial for consistent flow and reaction kinetics [27] [26]. |

| Initiator Tracer | A UV-absorbing initiator or other detectable species used in pulse tracer experiments to characterize the residence time distribution (RTD) of the reactor and validate plug-flow behavior [12]. |

| Chain Transfer Agent (CTA) | A reagent used to control molecular weight by terminating growing polymer chains. In flow, its initial concentration and flow rate can be dynamically optimized to precisely shape the MWD [19]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Required for flow electrochemistry applications to ensure sufficient conductivity of the reaction mixture, enabling the use of electrons as clean reagents for redox-initiated polymerizations [26]. |

Quantitative Data for Reactor Design

The following table summarizes key experimental data and design rules for constructing a tubular flow reactor capable of producing narrow MWD polymers, based on tracer studies for the ring-opening polymerization of lactide [12].

| Reactor Parameter | Experimental Range Tested | Impact on Plug Volume / MWD Control |

|---|---|---|

| Reactor Radius (R) | 0.0889 – 0.254 mm | Plug volume has a 2nd order dependency on radius (∝ R²). A smaller radius is preferred to minimize residence time distribution [12]. |

| Reactor Length (L) | 7.6 – 15.2 m | Plug volume has a half-order dependency on length (∝ √L) [12]. |

| Flow Rate (Q) | 63.4 – 267.5 µL/min | For polymerizations, plug volume showed a ~ -0.86 order dependency on flow rate. Lower flow rates increase residence time and can broaden MWD if not optimized [12]. |

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) for Simulating MWD in Non-Ideal Reactors

Troubleshooting Guide: Common CFD Simulation Challenges for Polymer MWD

| Challenge Category | Specific Issue | Potential Impact on MWD Simulation | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meshing & Geometry | Poor boundary layer mesh quality | Inaccurate prediction of local shear, affecting polymerization kinetics and dead chains [29]. | Perform mesh independence study; ensure y+ values ~1 for accurate near-wall physics [29]. |

| Geometry mistakes (gaps, leaks) in CAD model | Meshing failures; incorrect prediction of flow leakage and residence times [29]. | Use CAD cleanup tools; verify geometry is watertight before meshing [29]. | |

| Model Selection | Inappropriate turbulence model (e.g., k-ε for highly separated flows) | Incorrect velocity/pressure fields, leading to wrong residence time distributions and MWD breadth [30] [29]. | Use Scale-Resolving Simulation (SRS) models like SAS or DES for transient flows; validate model choice [29]. |

| Ignoring key physical effects (e.g., heat of reaction, viscosity change) | Missing key phenomena like hot spots, leading to inaccurate local kinetics and MWD skewing [29]. | Include coupled heat transfer and use variable viscosity models [30]. | |

| Numerical Stability | Simulation divergence or false convergence | Unreliable results; MWD cannot be trusted [29]. | Use proper under-relaxation factors; monitor integral quantities (e.g., total conversion) beyond residuals [29]. |

| Validation | Lack of experimental validation data | No confidence in CFD-predicted MWD; unknown model accuracy [31] [29]. | Benchmark against lab-scale reactor data for conversion and average molecular weights where possible [30]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why should I use CFD instead of an ideal reactor model for simulating Polymer Molecular Weight Distribution (MWD)?

Ideal reactor models assume perfect mixing, which is often not the case in industrial-scale polymer reactors. Non-ideal flow patterns, such as channeling or dead zones, create a distribution of residence times. Since MWD is directly tied to the history of reaction conditions a polymer chain experiences, these residence time distributions (RTDs) significantly impact the final MWD. CFD simulations explicitly resolve these spatial variations in velocity, temperature, and concentration, providing a more accurate prediction of the MWD than ideal models [30].

Q2: My CFD simulation of monomer conversion is stable, but the predicted MWD is unrealistic. What could be wrong?

This is a common issue that often points to a problem with the coupling between the flow field and the polymerization kinetics. Key areas to investigate are:

- Insufficient Mesh Resolution: The mesh might be fine for capturing bulk flow but too coarse to resolve micro-mixing effects, which are critical for initiating all chains simultaneously in a controlled polymerization [12].

- Inaccurate Kinetic Mechanism: Double-check the reaction rate constants, especially for initiation and termination steps. Small errors can magnify over the simulation and lead to unrealistic chain lengths [30] [6].

- Improper Mixing at Inlet: Poor mixing of initiator and monomer streams at the reactor inlet can lead to a distribution of initiation times, artificially broadening the MWD. Your simulation might need a more realistic model for the initial mixing zone [12].

Q3: What is the most efficient method to simulate the full MWD in a CFD framework, given its high computational cost?

Directly solving for millions of chain lengths within a CFD simulation is computationally prohibitive. A widely adopted and efficient strategy is the Method of Moments. This technique involves solving transport equations for the leading moments of the MWD (rather than the full distribution) within the CFD solver. Once the spatial fields of these moments are known, the full MWD can be reconstructed in a post-processing step. This approach drastically reduces computational cost while retaining the coupling between flow and kinetics [30].

Q4: How can I be confident that my CFD-predicted MWD is accurate?

Confidence is built through a rigorous process of Verification and Validation (V&V).

- Verification: Ask, "Am I solving the equations correctly?" This involves performing a mesh independence study to ensure your results do not change significantly with a finer mesh and checking that key conservation equations are satisfied [31] [29].

- Validation: Ask, "Am I solving the correct equations?" This requires comparing your CFD results with experimental data. Start by validating against simpler metrics like average velocity, temperature, or overall monomer conversion. If available, compare the final simulated MWD against an MWD measured from a physical reactor [31] [29].

Q5: What are the best practices for setting boundary conditions for a polymerization reactor simulation?

Using realistic boundary conditions is critical:

- Inlet Conditions: Avoid using a uniform velocity profile. If possible, use a measured or simulated turbulent velocity profile from the feed pipe.

- Outlet Conditions: For pressure outlets, implement backflow stabilization to prevent numerical divergence if reverse flow occurs.

- Walls: Specify correct wall boundary conditions, including no-slip for velocity and either a fixed temperature or heat flux for energy, based on your reactor's thermal control system [29].

Detailed Experimental & Simulation Protocols

Protocol: Coupling CFD and Kinetics for MWD Prediction

This protocol outlines the methodology for integrating a polymerization kinetic model into a CFD simulation to predict the molecular weight distribution in a non-ideal reactor [30].

Objective: To simulate the spatial variation of MWD in a non-ideal reactor by combining detailed flow physics with polymerization kinetics.

Methodology:

Pre-Processing and Geometry Setup:

- Geometry Creation: Develop a 3D CAD model of the reactor (e.g., tubular or autoclave), including internals like impellers, baffles, and inlets/outlets.

- Mesh Generation: Create a computational mesh. Pay special attention to refining regions with high velocity or temperature gradients (e.g., near impellers, walls, and inlets). Perform a mesh sensitivity analysis to ensure results are grid-independent.

- Solver Settings: Select a pressure-based, transient solver.

Physics Setup:

- Material Properties: Define temperature-dependent properties for all species (monomer, polymer, solvent), including density, viscosity, and thermal conductivity. Account for the drastic increase in viscosity with conversion.

- Turbulence Model: Select an appropriate model. For stirred tanks, SAS or DES models are often suitable. Ensure near-wall treatment is consistent with the mesh (e.g., use wall functions if y+ > 30).

- Reactive Flow Setup: Activate the species transport model.

- Boundary Conditions:

- Inlets: Specify inlet flow rates, temperature, and species mass fractions.

- Walls: Set to no-slip condition and define a thermal boundary condition (e.g., constant temperature or heat flux).

- Outlet: Use a pressure outlet boundary condition.

Kinetic Model Implementation (User-Defined Functions - UDFs):

- Develop UDFs to define the polymerization kinetic source terms. The kinetic scheme for free-radical polymerization should include [30]:

- Initiator decomposition

- Chain initiation

- Propagation

- Chain transfer to monomer

- Termination (combination and disproportionation)

- Implement the Method of Moments within the UDFs. This involves solving transport equations for the live and dead moments of the MWD within the CFD domain [30].

- Compile and hook the UDFs to the CFD solver to calculate species source terms and reaction heat.

- Develop UDFs to define the polymerization kinetic source terms. The kinetic scheme for free-radical polymerization should include [30]:

Solution and Monitoring:

- Initialize the flow field.

- Use a coupled solver for pressure-velocity coupling.

- Employ a second-order discretization scheme for accuracy.

- Run the simulation and monitor the residuals, as well as integral quantities like total monomer conversion and area-weighted averages of molecular weight moments at the outlet.

Post-Processing and MWD Reconstruction:

- Once the simulation converges, post-process the results to obtain spatial distributions of the molecular weight moments (e.g., λ₀, λ₁, λ₂).

- Reconstruct the full MWD at the reactor outlet and at specific internal points using the predicted moments, typically by assuming a functional form for the distribution (e.g., Gamma distribution) [30].

Protocol: Validating CFD Results with a Target MWD

This protocol describes how to use CFD simulations to find operating conditions that produce a polymer with a target MWD, a key aspect of reactor optimization [30] [6].

Objective: To determine the optimal reactor operating conditions (e.g., temperature profile, initiator feed rate) that maximize conversion while achieving a desired target MWD.

Methodology:

Define Target MWD and Objective Function:

- Precisely define the target MWD curve.

- Formulate an objective function for optimization, for example: Maximize monomer conversion, subject to the constraint that the simulated MWD matches the target MWD within a specified tolerance [30].

Set Up a CFD Simulation Suite:

- Parameterize the key operating conditions you wish to optimize (e.g., inlet temperature, wall temperature profile, initiator concentration).

- Use the CFD solver's built-in design exploration tools or external scripting to create a series of simulation cases that span a range of these parameters.

Run Automated Simulations and MWD Analysis:

- Execute the suite of CFD simulations.

- For each case, post-process the results to compute the final MWD at the reactor outlet and the total monomer conversion.

Optimization Loop:

- Compare the simulated MWD from each run against the target MWD.

- Based on the error, an optimization algorithm (e.g., gradient-based or surrogate-based) calculates a new set of improved operating conditions [30].

- The CFD simulation is run again with these new conditions.

- This loop continues until the objective function is minimized (i.e., the MWD matches the target and conversion is maximized).

Workflow Visualization

MWD-CFD Coupling Workflow

MWD Optimization Loop

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Computational Solutions

| Item Name | Function / Relevance in MWD-CFD Simulation |

|---|---|

| ANSYS Fluent | A commercial CFD software package widely used for simulating fluid flow, heat transfer, and chemical reactions. It allows integration of User-Defined Functions (UDFs) for custom polymerization kinetics [30]. |

| Method of Moments | A mathematical technique implemented via UDFs to track polymer MWD without the prohibitive cost of solving for each chain length. It calculates distribution moments within the CFD solver [30]. |

| User-Defined Function (UDF) | A piece of custom C code that interfaces with the CFD solver to define complex physical models, such as polymerization reaction rates and molecular weight moment calculations [30]. |

| Kinetic Parameters (kd, kp, kt) | The fundamental rate constants for initiator decomposition (kd), propagation (kp), and termination (kt). Accurate values from literature or experiments are essential for realistic MWD prediction [30] [6]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | A network of computers providing massive parallel processing power, which is often necessary to run complex, transient, multi-phase CFD simulations with reasonable turnaround times [29]. |

| Gambit / ANSYS Meshing | Software tools used for creating the geometry and generating the computational mesh for the reactor simulation. Mesh quality is a primary factor in solution accuracy [30]. |

AI and Machine Learning in Polymer Processing Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can AI specifically help optimize the Molecular Weight Distribution (MWD) of polymers? AI, particularly machine learning models, can establish a quantitative relationship between polymerization conditions and the resulting MWD. This allows researchers to reverse-engineer process parameters to achieve a target MWD, which is crucial for tuning final polymer properties like tensile strength and melt viscosity. A dedicated ML approach maps the MWD to physical properties, enabling the design of polymers with user-specified characteristics and the valorization of recycled plastic waste [32].

Q2: Our experimental polymer data is limited. Can we still use machine learning effectively? Yes, strategies exist to overcome data scarcity. Active learning is a powerful technique where the model strategically selects the most informative data points for experimental testing, maximizing knowledge gain from a limited number of experiments [33]. Furthermore, leveraging pre-trained models like polyBERT or PerioGT, which are trained on vast datasets of polymer chemical structures, provides a significant head start, even with limited in-house data [34] [35].

Q3: We use traditional fingerprinting methods to represent polymers. Are there better alternatives? Recent AI models offer superior alternatives to traditional manual fingerprinting. Tools like polyBERT use a transformer architecture to understand the "chemical language" of polymers from their SMILES strings, capturing complex atomic-level relationships. This approach is over two orders of magnitude faster than fingerprinting and is more effective for high-throughput screening of polymer spaces [34]. Periodicity-aware models like PerioGT further advance this by explicitly incorporating the repeating nature of polymer chains into the learning framework, enhancing model generalization and performance [35].

Q4: How does AI integrate into a closed-loop optimization system for polymer processing? In a Closed-Loop AI Optimization (AIO) system, machine learning models use real-time plant data to dynamically adjust process setpoints. For example, the AI can continuously fine-tune reactor temperatures, screw speeds, and cooling rates to maintain optimal conditions. This real-time adjustment compensates for disturbances like feedstock variability or reactor fouling, minimizing off-spec production and ensuring consistent MWD and product quality without manual intervention [36].

Q5: Can AI help in discovering entirely new polymer materials for specific applications? Absolutely. AI accelerates the discovery of novel polymers by rapidly screening vast chemical spaces. A notable example is the use of ML to identify ferrocene-based mechanophores. The model screened thousands of candidates to find molecules that, when incorporated as crosslinkers, create polymers that are significantly more tear-resistant. This demonstrates AI's potential to design more durable plastics and reduce waste [37].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Model Performance on Limited Datasets

Problem: Your ML model for property prediction has high error rates due to insufficient training data.

Solution: Implement data-efficient modeling strategies.

- Step 1: Employ Transfer Learning. Start with a model pre-trained on a large, general polymer dataset (e.g., polyBERT's training on 80 million structures). Then, fine-tune it on your smaller, specific dataset. This leverages generalized chemical knowledge already captured by the model [34] [35].

- Step 2: Utilize Active Learning. Instead of random experimentation, use an active learning loop:

- Train an initial model on your available data.

- Let the model predict the next most informative data point to test.

- Run the experiment and add the new data to the training set.

- Retrain the model and repeat. This minimizes the number of costly experiments needed [33].

- Step 3: Apply Data Augmentation. For graph-based models, use graph augmentation strategies. This can include integrating virtual nodes to model chemical interactions or generating slightly altered versions of existing polymer graphs to create a larger, more robust training set [35].

Issue 2: Inaccurate Predictions of Polymer Mechanical Properties

Problem: Model predictions for properties like toughness or tear strength do not align with experimental validation.

Solution: Enhance feature representation and model selection.

- Step 1: Incorporate Advanced Structural Descriptors. Move beyond simple fingerprints. Use periodicity-aware graph representations that treat the polymer as a periodic graph, capturing the repeating unit structure more accurately. This has been shown to improve performance on downstream tasks [35].

- Step 2: Leverage Multi-Task Learning. Train a model to predict several properties simultaneously (e.g., tensile strength, glass transition temperature, and tear resistance). This allows the model to leverage hidden correlations within the data, often improving the accuracy for each individual property compared to single-task models [34].

- Step 3: Validate with Mechanophore Integration. As a case study, if aiming for toughness, consider crosslinkers identified by AI. Follow the workflow in the diagram below, which uses ML to screen for weak, force-responsive crosslinkers (mechanophores) that can dramatically increase tear resistance by forcing cracks to break more bonds [37].

Experimental Protocol: AI-Guided Discovery of Tougher Plastics

This protocol details the methodology for using ML to identify and validate mechanophores for creating more tear-resistant polymers, as conducted by MIT and Duke University [37].

1. Objective: To employ a machine-learning model to rapidly screen a database of organometallic compounds (ferrocenes) to identify candidate mechanophores that function as weak crosslinkers, and to experimentally validate that they produce tougher polyacrylate plastics.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Cambridge Structural Database: A comprehensive database of experimentally synthesized crystal structures, used as the source for 5,000 ferrocene structures [37].

- Computational Software: For performing Density Functional Theory (DFT) or similar calculations to determine the force required to break bonds in the mechanophore.

- Machine Learning Model: A neural network model (as described in the study).

- Chemical Reagents: For polymer synthesis, including acrylate monomers, initiators, and the selected ferrocene crosslinker (e.g., m-TMS-Fc).

- Polymer Testing Equipment: An instrument for performing stress-strain tests to measure tear resistance (toughness).

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

Phase 1: Computational Screening

- Data Curation: Extract ~5,000 ferrocene structures from the Cambridge Structural Database. Generate an additional ~7,000 derivative compounds by systematically rearranging functional groups.

- Initial Simulation: For a subset of 400 compounds, perform computational simulations to calculate the mechanical force required to break bonds within the molecule (the activation force).

- Model Training: Train a neural network using the molecular structures of the 400 compounds as input and the calculated activation forces as the target output.

- High-Throughput Prediction: Use the trained model to predict the activation forces for the remaining thousands of compounds in the database.

- Candidate Selection: Analyze the model's predictions and output to identify the top ~100 candidates with the lowest activation forces. Prioritize molecules with features the model deems important, such as bulky functional groups attached to both rings.

Phase 2: Experimental Validation

- Synthesis: Select a top candidate (e.g., m-TMS-Fc) and synthesize it. Create a polyacrylate material where this ferrocene acts as a crosslinker between polymer strands.

- Control Preparation: Synthesize a control material using a standard ferrocene crosslinker.

- Mechanical Testing: Subject both the candidate and control polymer samples to standardized tear tests, applying force until the material fractures.

- Analysis: Calculate the toughness of each material from the stress-strain data. Compare the performance of the AI-identified candidate against the control.

4. Expected Outcome: The polymer crosslinked with the AI-identified mechanophore (m-TMS-Fc) is expected to be significantly tougher—approximately four times more tear-resistant—than the control polymer, validating the ML prediction [37].

The table below summarizes key performance metrics reported from the industrial and research application of AI in polymer processing.

Table 1: Quantitative Improvements from AI Application in Polymer Processing

| Application Area | Key Performance Indicator | Reported Improvement | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Industrial Process Optimization | Reduction in Off-Spec Production | Over 2% reduction | [36] |

| Throughput Increase | 1 to 3% increase | [36] | |