NMR and FTIR in Polymer Characterization: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a detailed exploration of Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy for polymer characterization, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

NMR and FTIR in Polymer Characterization: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a detailed exploration of Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy for polymer characterization, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It covers the fundamental principles of these techniques, their specific methodological applications for analyzing polymer structure and composition, strategies for troubleshooting complex samples, and approaches for data validation and comparative analysis. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with advanced applications, this guide aims to empower scientists to effectively utilize NMR and FTIR for optimizing polymeric materials, with a special focus on advancements in drug delivery systems and biomedical applications.

Understanding NMR and FTIR: Core Principles for Polymer Analysis

Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy is a powerful analytical technique used to identify a material's molecular composition by measuring how it absorbs infrared light. This method provides detailed insights into molecular structure, making it invaluable across various industries, particularly for analyzing polymers and complex biological materials [1]. In the context of polymer characterization, FTIR spectroscopy serves as a complementary technique to Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), offering unique capabilities for functional group identification and chemical bond analysis that are essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The fundamental principle of FTIR spectroscopy revolves around molecular vibrations. When IR radiation interacts with a sample, specific frequencies are absorbed that correspond to molecular bond vibrations, including stretching, bending, or twisting of dipoles [2]. These vibrational energies are discrete and characteristic of specific functional groups, creating a unique molecular "fingerprint" for each compound. Modern FTIR spectrometers employ an interferometer with a moving mirror that generates an interferogram, which is then transformed via a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) algorithm into a recognizable intensity-versus-wavenumber spectrum [3] [2]. This approach provides significant advantages over dispersive IR instruments, including higher signal-to-noise ratios, better spectral resolution, faster data collection, and more reliable calibration transfer through Fellgett's (multiplex), Jacquinot's (throughput), and Connes' advantages [3] [2].

Fundamental Principles of FTIR Spectroscopy

Molecular Vibrations and Infrared Absorption

At the core of FTIR spectroscopy is the relationship between molecular vibrations and infrared light absorption. Molecules consist of atoms connected by chemical bonds that behave like microscopic springs, constantly vibrating at specific frequencies. When infrared radiation interacts with a sample, energy is absorbed when the frequency of radiation matches one of the natural vibrational frequencies of the molecular bonds [4]. This absorption causes changes in the dipole moments of molecules, leading to vibrational transitions between quantized energy states [3] [2].

The vibrational energy of a molecule depends on two primary variables: the reduced mass (μ) of the atoms forming the bond and the bond spring constant (k), which represents bond strength [3]. This relationship explains why different functional groups absorb at characteristic wavenumbers. For instance, triple bonds (C≡C) appear at higher wavenumbers than double bonds (C=C), which in turn appear at higher wavenumbers than single bonds (C-C), demonstrating that bond strength alters wavenumbers more significantly than atomic mass [3]. Similarly, substituting atoms in a C-C bond with heteroatoms like nitrogen or oxygen causes measurable shifts in absorption wavenumbers due to changes in both mass and bond strength [3].

The FTIR Instrument and Measurement Process

Modern FTIR spectrometers utilize an interferometer design, most commonly of the Michelson type, which consists of a broadband IR source, beam splitter, fixed and moving mirrors, and a detector [2]. As the moving mirror travels, it creates constructive and destructive interference patterns—an interferogram—that encodes all spectral frequencies simultaneously. The interferogram is then mathematically transformed by a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) algorithm into a conventional intensity-versus-wavenumber spectrum [3] [2].

The measurement process involves several critical steps. First, a background spectrum is collected without the sample to account for instrumental and environmental factors. The sample is then placed in the IR beam path, and its interferogram is collected. After Fourier transformation, the resulting spectrum represents the molecular fingerprint of the sample, showing specific absorption bands corresponding to its functional groups and chemical bonds [2]. This process enables the identification of organic compounds, verification of product quality, and investigation of material failures with precision and reliability [1].

Sampling Techniques in FTIR Spectroscopy

Modern FTIR instruments support multiple sampling geometries, each suited to different sample types and analytical requirements. The most common techniques include:

- Transmission: IR light passes through a thin film, gas cell, or KBr pellet. This mode is suitable for transparent samples but requires careful sample thickness control [2].

- Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR): The most popular modern technique, ATR uses an internal reflection element (IRE) such as diamond, ZnSe, or Ge to guide the IR beam through the sample interface. With a penetration depth of approximately 1–2 µm, ATR enables direct analysis of solids, liquids, and gels without extensive preparation [1] [2].

- Diffuse Reflectance (DRIFTS): This method collects scattered radiation from powders or rough surfaces, making it excellent for analyzing soils, catalysts, or asphalt materials [2].

- Specular Reflection and RAIRS: Used for thin films or monolayers on reflective substrates, particularly in surface and catalytic studies [2].

- Photoacoustic (FT-IR-PAS) and Microspectroscopy (µ-FT-IR): These techniques extend FT-IR to inhomogeneous, micro-scale, or non-transparent samples [2].

For polymer characterization, ATR-FTIR has become particularly valuable due to its minimal sample preparation requirements and suitability for analyzing various physical forms of polymers, including films, solids, and viscous liquids [1].

Identifying Functional Groups and Chemical Bonds

Characteristic Absorption Bands

Functional groups in organic molecules display characteristic infrared absorption bands that enable their identification. These absorptions occur in specific regions of the IR spectrum, providing a systematic approach to molecular structure elucidation. The following table summarizes key functional group absorptions particularly relevant to polymer characterization:

Table 1: Characteristic FTIR Absorption Bands for Common Functional Groups

| Functional Group | Bond Type | Absorption Range (cm⁻¹) | Band Characteristics | Example Polymer/Compound |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxyl (O-H) | Stretch | 3200-3600 | Very broad, strong | Poly(vinyl alcohol), Ethanol [5] |

| Carbonyl (C=O) | Stretch | 1700-1750 | Strong, sharp | Polyesters, Polycarbonates, Ethyl acetate [5] |

| Amine (N-H) | Stretch | 3300-3500 | Primary: two peaks; Secondary: one peak; Tertiary: none | Nylon, Butylamine [5] |

| Methylene (CH₂) | Asymmetric Stretch | ~2920 | Strong | Polyethylene [6] |

| Methylene (CH₂) | Symmetric Stretch | ~2850 | Strong | Polyethylene [6] |

| Ester (C-O) | Stretch | 1050-1300 | Strong, often multiple peaks | Poly(ethylene terephthalate), Ethyl acetate [5] |

| Nitrile (C≡N) | Stretch | ~2240 | Sharp, medium intensity | Acrylonitrile-based polymers, Acetonitrile [5] |

| Olefin (=C-H) | Stretch | ~3010 | Medium | Unsaturated polymers, Polyethylene (unsat.) [7] |

The "fingerprint region" (approximately 1500-600 cm⁻¹) contains complex absorption patterns resulting from coupled vibrations that are unique to each molecule, serving as a molecular signature for compound identification [5]. While this region can be challenging to interpret for specific functional groups, it provides valuable information for material verification and quality control.

Practical Interpretation Strategies

Successful interpretation of FTIR spectra requires a systematic approach that combines knowledge of characteristic group frequencies with careful observation of band patterns. The following protocol outlines a standard methodology for functional group identification:

Table 2: Protocol for FTIR Spectral Interpretation

| Step | Procedure | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Sample Preparation | Prepare sample appropriate for sampling technique (ATR, transmission, etc.). | For ATR, ensure good contact with crystal; for transmission, optimize thickness to avoid saturation [2]. |

| 2. Spectral Acquisition | Collect spectrum with appropriate parameters. | Typical resolution: 4 cm⁻¹; 16-32 scans; proper background collection [8] [2]. |

| 3. Initial Assessment | Examine C-H stretching region (3000-2800 cm⁻¹). | Number of peaks indicates methyl/methylene presence; peaks above 3000 cm⁻¹ suggest unsaturation [6]. |

| 4. Carbonyl Analysis | Check 1750-1700 cm⁻¹ region for C=O stretch. | Note exact position: esters (~1735), acids (~1710), conjugated carbonyls (20-30 cm⁻¹ lower) [5]. |

| 5. Heteroatom Identification | Scan for O-H, N-H (3600-3200 cm⁻¹). | O-H is broad; N-H is sharper; primary amines show two peaks [5]. |

| 6. Fingerprint Region | Analyze 1500-600 cm⁻¹ for specific patterns. | Use library matching for complex patterns; note C-O stretches around 1100-1300 cm⁻¹ [5] [2]. |

| 7. Band Ratio Calculation | Calculate significant band area ratios. | Provides semi-quantitative comparison; e.g., A3010/A2923 for unsaturation [7]. |

For polymer applications, specific spectral features provide valuable structural information. For example, the presence of a methyl group umbrella mode at 1377 cm⁻¹ distinguishes low-density polyethylene (LDPE) from high-density polyethylene (HDPE), which lacks this peak due to the absence of side chains [6]. Similarly, the degree of unsaturation in polymer chains can be quantified using band area ratios such as A3010/A2923+2852, which reflects the unsaturated-to-saturated lipid content [7].

Experimental Protocols for Polymer Characterization

Standard Operating Procedure for Polymer Analysis by ATR-FTIR

Principle: This protocol describes the analysis of polymer samples using ATR-FTIR to identify functional groups and chemical structure of the repeat units [6] [1].

Materials and Equipment:

- FTIR spectrometer with ATR accessory (diamond crystal recommended)

- Polymer samples (films, solids, or powders)

- Forceps and cleaning supplies (methanol, lint-free wipes)

- Microtome or blade (for sectioning thick samples)

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for FTIR Polymer Analysis

| Item | Specification | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| ATR Crystal | Diamond, ZnSe, or Germanium | Provides internal reflection for surface measurement [1] [2] |

| Cleaning Solvent | HPLC-grade methanol | Removes residual sample from crystal without damage [2] |

| Polymer Standards | Known reference materials (e.g., PE, PP, PS) | Instrument verification and method validation [1] |

| Background Material | Clean ATR crystal or air | Establishes baseline reference spectrum [2] |

| Sample Mounting Device | Pressure applicator or clamp | Ensures consistent sample-crystal contact [1] |

Procedure:

- Instrument Preparation: Turn on FTIR spectrometer and allow to warm up for at least 15 minutes. Initialize the instrument control software.

- Background Collection: Clean the ATR crystal thoroughly with methanol and lint-free wipes. Collect a background spectrum with the clean crystal exposed to air [2].

- Sample Preparation:

- For films: Cut a piece approximately 1x1 cm to cover the ATR crystal.

- For powders: Create a uniform layer on the crystal.

- For bulk materials: Section if necessary to ensure good crystal contact.

- Sample Placement: Position the sample on the ATR crystal. Apply consistent pressure using the integrated pressure applicator to ensure optimal contact [1].

- Spectral Acquisition:

- Post-Processing:

- Apply automatic ATR correction if available [8]

- Perform baseline correction if necessary

- Normalize spectra if comparing multiple samples

- Interpretation:

- Identify key functional groups using characteristic absorption bands (refer to Table 1)

- Compare with library spectra if available

- Note any oxidation peaks (e.g., carbonyl around 1710 cm⁻¹) that may indicate degradation

Quality Control: Validate instrument performance periodically using certified polystyrene standards with known absorption peaks [1].

Advanced Protocol: Monitoring Polymer Degradation by TGA-IR

Principle: This hyphenated technique combines thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) with FTIR spectroscopy to study polymer decomposition and identify evolved gases, providing insights into degradation mechanisms and material stability [1].

Materials and Equipment:

- TGA-IR system with heated transfer line

- Polymer samples

- High-purity nitrogen or air (depending on degradation atmosphere)

- Temperature calibration standards

Procedure:

- System Setup: Connect TGA to FTIR spectrometer via heated transfer line maintained at appropriate temperature (typically 200-300°C) to prevent condensation of evolved gases.

- Method Programming:

- Set TGA temperature program (e.g., 25-800°C at 10°C/min)

- Configure FTIR to collect spectra continuously (e.g., every 10-15 seconds)

- Set spectral parameters: 4 cm⁻¹ resolution, 4000-600 cm⁻¹ range

- Sample Analysis:

- Place 10-20 mg of polymer sample in TGA pan

- Initiate temperature program and simultaneous FTIR data collection

- Monitor real-time Gram-Schmidt plot to track decomposition events

- Data Analysis:

- Identify decomposition steps from TGA weight loss curve

- Extract FTIR spectra at specific temperatures or weight loss events

- Identify evolved gases (e.g., CO₂ at ~2350 cm⁻¹, water at ~1500-1600 cm⁻¹)

- Use library spectra to identify organic degradation products

Applications: This method is particularly valuable for failure analysis, lifetime prediction, and understanding degradation pathways in polymers such as polypropylene and polyethylene [1].

Applications in Polymer Research

FTIR spectroscopy provides versatile applications in polymer characterization, offering insights that complement other analytical techniques like NMR. Key applications include:

Chemical Structure Identification

FTIR spectroscopy is fundamentally used to identify the chemical structure of polymer repeat units. Unlike small molecules, polymer spectra are determined primarily by the repeat unit structure rather than total molecular weight, as each repeat unit contributes identically to the overall spectrum [6]. This enables researchers to distinguish between polymer types, identify unknown materials, and verify monomer incorporation in copolymers. For example, FTIR can readily differentiate between low-density polyethylene (LDPE) with characteristic methyl umbrella modes at 1377 cm⁻¹ and high-density polyethylene (HDPE) lacking these peaks due to fewer side chains [6].

Degradation and Oxidation Monitoring

Polymer degradation, whether thermal, oxidative, or environmental, produces detectable changes in FTIR spectra. The formation of carbonyl groups (1700-1750 cm⁻¹) is a common indicator of oxidation in polymers such as polypropylene and polyethylene [1] [2]. Using accelerated aging protocols with in-situ FTIR monitoring, researchers can study degradation mechanisms in real-time, identifying specific degradation products and calculating kinetic parameters like activation energy [1]. This application is crucial for predicting material lifetime, developing stabilizer systems, and understanding failure mechanisms in plastic components.

Crystallinity Analysis

FTIR spectroscopy can quantify crystallinity in semi-crystalline polymers through careful analysis of specific absorption bands. Different spectral regions are associated with amorphous and crystalline phases of polymers, enabling calculation of crystallinity ratios [9] [2]. For example, in poly(ε-caprolactone), curve-fitting methods applied to the carbonyl stretching region have successfully determined crystallinity, achieving agreement with conventional techniques like differential scanning calorimetry [2]. Similarly, crystallinity in apatite-containing systems can be calculated by sub-peak fitting of the phosphate region (1154-900 cm⁻¹) and determining the ratio of sub-peaks at 1030 and 1020 cm⁻¹ [8].

Surface Modification Verification

FTIR-ATR is particularly valuable for verifying surface modifications of polymers, such as the immobilization of active molecules in catheter matrices for drug delivery applications [2]. By detecting functional groups indicative of both covalent and non-covalent interactions, FTIR confirms successful modification and provides insights into the chemical nature of surface changes. This application supports the development of advanced biomaterials, functional coatings, and specialized polymer surfaces for medical devices and implants.

Blend Compatibility and Interactions

FTIR spectroscopy can study polymer blend compatibility and interactions between different polymers in mixtures, which is essential in designing polymer composites and blends with specific properties [9]. Shifts in characteristic absorption bands indicate intermolecular interactions between blend components, while the presence of new bands may suggest chemical reactions at interfaces. This information guides the development of optimized polymer blends with enhanced mechanical properties and stability.

FTIR spectroscopy remains an indispensable tool for polymer characterization, providing critical information about functional groups, chemical bonds, and material properties that complement data from other analytical techniques like NMR. The fundamental principles of molecular vibrations and infrared absorption translate into practical applications that span chemical structure identification, degradation monitoring, crystallinity analysis, surface modification verification, and blend compatibility assessment.

As FTIR technology continues to evolve, driven by advancements in automation, sensitivity, and integration with complementary techniques like TGA and rheometry, its role in polymer research and development will expand further. The ability to combine FTIR with microscopy, thermal analysis, and mechanical testing provides researchers with comprehensive insights into complex material systems, enabling innovations in polymer science and applications across industries from biomedical devices to sustainable materials. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, mastering FTIR spectroscopy principles and applications remains essential for advancing polymer characterization capabilities.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy stands as a cornerstone analytical technique for determining the molecular structure, dynamics, and composition of polymers. For researchers and drug development professionals, it provides indispensable insights into the chemical architecture of polymeric materials, from commodity plastics to advanced drug delivery systems. The power of NMR lies in its ability to probe the local magnetic environment of nuclei, such as ^1H and ^13C, revealing detailed information about the polymer backbone, stereochemical configuration, and monomer sequencing [10] [11]. This application note delineates the essential theory and practical protocols for employing NMR spectroscopy to elucidate two fundamental aspects of polymer structure: the backbone connectivity and the tacticity of the chain. Within the broader context of polymer characterization, NMR serves as a complementary and orthogonal technique to FTIR, providing atomic-level resolution that is critical for rational material design in pharmaceutical applications [12] [10].

Essential Theory

Fundamental NMR Principles for Polymers

NMR spectroscopy exploits the magnetic properties of certain atomic nuclei. When placed in a strong external magnetic field, nuclei with a non-zero spin, such as ^1H and ^13C, can absorb electromagnetic radiation in the radiofrequency range. The exact frequency at which absorption occurs—the chemical shift (δ, measured in ppm)—is exquisitely sensitive to the local electronic environment of the nucleus [11]. This forms the primary source of structural information. In polymers, this allows for the discrimination of different monomer units and functional groups along the chain.

Spin-spin coupling (J-coupling) arises from magnetic interactions between neighboring nuclei transmitted through chemical bonds. The resulting splitting patterns in the NMR spectrum provide information about the number of adjacent protons and the connectivity between atoms [13]. For complex polymers, one-dimensional (1D) ^1H or ^13C NMR spectra can often suffer from signal overlap. Two-dimensional (2D) NMR techniques, such as Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence (HSQC), overcome this by spreading correlations across a second frequency dimension, dramatically enhancing spectral resolution and enabling unambiguous assignment of polymer structure [11].

NMR Analysis of Polymer Backbone Structure

Elucidating the structure of the polymer backbone is a primary application of NMR. A powerful example is the identification of an unknown insoluble solid during the large-scale synthesis of the drug Faldaprevir. Through a combination of solution and solid-state NMR techniques, the impurity was identified as Poly-Faldaprevir, where polymerization occurred via the vinyl cyclopropane group through a free-radical mechanism [14]. This case highlights the critical role of NMR in identifying and characterizing unexpected polymeric species in pharmaceutical development.

For standard polymer characterization, backbone structure is often confirmed by assigning the chemical shifts of the main-chain protons and carbons. The table below summarizes characteristic chemical shifts for common polymer backbones.

Table 1: Characteristic ¹H and ¹³C NMR Chemical Shifts for Common Polymer Backbones

| Polymer | Backbone Group | ¹H Chemical Shift (δ, ppm) | ¹³C Chemical Shift (δ, ppm) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) | -O-CH₂-CH₂- | 3.6 - 3.7 | ~70 | [12] |

| Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) | -O-CH₂- | 4.0 - 4.2 | ~64 | [12] |

| -C(=O)-CH₂- | 2.3 - 2.5 | ~34 | [12] | |

| Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) | -C-CH₂- (backbone) | 1.8 - 2.2 | 44 - 54 | [15] |

| -C(CH₃)- | 1.0 - 1.2 | 16 - 22 | [15] |

NMR Analysis of Polymer Tacticity

Tacticity describes the stereochemical arrangement of pendant groups along the polymer backbone and is a critical determinant of a material's physical properties, including crystallinity, glass transition temperature (Tg), and mechanical strength [15]. NMR is the preeminent technique for determining tacticity.

In vinyl polymers (─CH₂─CHR─)ₙ, the relative stereochemistry of consecutive chiral centers leads to three primary microstructures:

- Isotactic: Pendant groups (R) are consistently on the same side of the backbone.

- Syndiotactic: Pendant groups alternate regularly from one side to the other.

- Atactic: Pendant groups are arranged randomly.

This stereochemistry profoundly impacts material properties. For instance, the glass transition temperature (Tg) of pure isotactic PMMA is ~42 °C, while that of pure syndiotactic PMMA is ~124 °C [15]. The NMR spectrum is sensitive to these configurational differences because the magnetic environment of a nucleus is influenced by the stereochemistry of its neighbors. For example, in PMMA, the backbone methylene (─CH₂─) protons appear as a single peak in the syndiotactic configuration, where the two protons are equivalent. In the isotactic configuration, they are diastereotopic and give rise to two distinct peaks [15]. Advanced ¹³C NMR methods, including those using relaxation agents and polarization transfer like RINEPT, are employed for rapid and quantitative analysis of tacticity in polymers like polypropylene [16].

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Molecular Weight by End-Group Analysis

Principle: The number-average molecular weight (Mₙ) of a polymer can be determined by comparing the integral of signals from the chain-end groups to the integral of signals from the repeating monomer units in a ¹H NMR spectrum [12].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve 10-50 mg of the polymer in 0.6-0.7 mL of a suitable deuterated solvent (e.g., CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆). Ensure the sample is fully dissolved and homogeneous.

- Data Acquisition: Acquire a standard ¹H NMR spectrum on an 80 MHz or higher-field spectrometer. Use a sufficient number of scans (typically 16-64) to achieve a good signal-to-noise ratio. Employ a relaxation delay of at least 5-6 seconds to allow for full proton relaxation between pulses [12].

- Data Processing and Analysis:

- Phase and baseline-correct the spectrum.

- Identify and integrate a signal unique to the end-group and a signal from the repeating backbone unit.

- Calculate the Degree of Polymerization (DP) and Mₙ using the equations below, where Iₑ and Iᵣ are the integrals of the end-group and repeat-unit signals, and Nₑ and Nᵣ are the number of protons giving rise to those signals [12].

Calculations:

- Degree of Polymerization (DP):

DP = (Iᵣ / Nᵣ) / (Iₑ / Nₑ) - Number-Average Molecular Weight (Mₙ):

Mₙ = DP × Mᵣwhere Mᵣ is the molecular weight of the repeating unit.

Table 2: Example End-Group Analysis for Common Polymers

| Polymer | End Group Signal (δ, ppm) | Backbone Signal (δ, ppm) | Calculation Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methoxy-PEG | -OCH₃ at ~3.4 | -O-CH₂-CH₂- at ~3.7 | Nₑ (OCH₃) = 3, Nᵣ (CH₂) = 4 | [12] |

| Tosyl-PCL | Aromatic H at ~7.7-7.9 | -O-CH₂- at ~4.1 | Nₑ (Tosyl) = 8 (for two ends), Nᵣ (O-CH₂) = 2 | [12] |

Protocol 2: Determining Copolymer Composition

Principle: The molar ratio of monomers in a copolymer can be directly determined from the integral ratios of well-resolved signals characteristic of each monomer unit in the ¹H NMR spectrum [12].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a solution as described in Protocol 1.

- Data Acquisition: Acquire a quantitative ¹H NMR spectrum with a long relaxation delay and a pulse angle of 90° to ensure accurate integration.

- Data Analysis:

- Identify and integrate one signal from each monomer unit (A and B).

- Calculate the molar ratio using the equation below, where Iₐ and Iբ are the integrals, and Nₐ and Nբ are the number of protons for the selected signals from monomers A and B, respectively [12].

Calculation:

- Molar Ratio A/B:

Ratio (A/B) = (Iₐ / Nₐ) / (Iբ / Nբ)

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Polymer NMR

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents (CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆) | Provides a signal for spectrometer locking and avoids dominant solvent signals in the spectrum. | Standard solvent for most polymer solutions. |

| Chromium(III) Acetylacetonate (Cr(acac)₃) | Relaxation agent; reduces long ¹³C T₁ relaxation times, allowing for faster data acquisition. | Essential for rapid, quantitative ¹³C NMR analysis of polypropylene tacticity [16]. |

| Magic Angle Spinning (MAS) Probe | Spins the solid sample at the "magic angle" (54.74°) to average anisotropic interactions, dramatically improving resolution. | Used in solid-state NMR for insoluble polymers (e.g., Poly-Faldaprevir characterization) [14] [17]. |

| Cross Polarization (CP) | Enhances sensitivity of low-abundance nuclei (e.g., ¹³C) by transferring polarization from abundant nuclei (e.g., ¹H). | Standard solid-state NMR experiment for structure elucidation [14]. |

Protocol 3: Structure Elucidation of Complex/Insoluble Polymers via Solid-State NMR

Principle: For polymers that are insoluble or cannot be dissolved without degradation, solid-state NMR with Magic Angle Spinning (MAS) and Cross Polarization (CP) is required for structure elucidation [14] [17].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Pack the solid polymer powder into a MAS rotor. The rotor size is selected based on the available probe (e.g., 4 mm, 3.2 mm).

- Experimental Setup:

- Set the magic angle precisely to 54.74°.

- Calibrate the ¹H and ¹³C channel powers, including the CP contact pulse.

- Select a MAS spinning speed sufficient to resolve the signals of interest (e.g., 10-15 kHz for many applications).

- Data Acquisition:

- CP/MAS: Acquire a standard ¹³C CP/MAS spectrum for initial structural assessment.

- 2D HETCOR (Heteronuclear Correlation): Perform a 2D experiment to correlate ¹H and ¹³C chemical shifts, providing connectivity information crucial for assigning the polymer backbone, as demonstrated for Poly-Faldaprevir [14].

- Data Analysis: Analyze the 2D spectrum by identifying cross-peaks that connect proton and carbon chemical shifts. These correlations are used to map out the molecular structure of the polymer.

Workflow Visualization

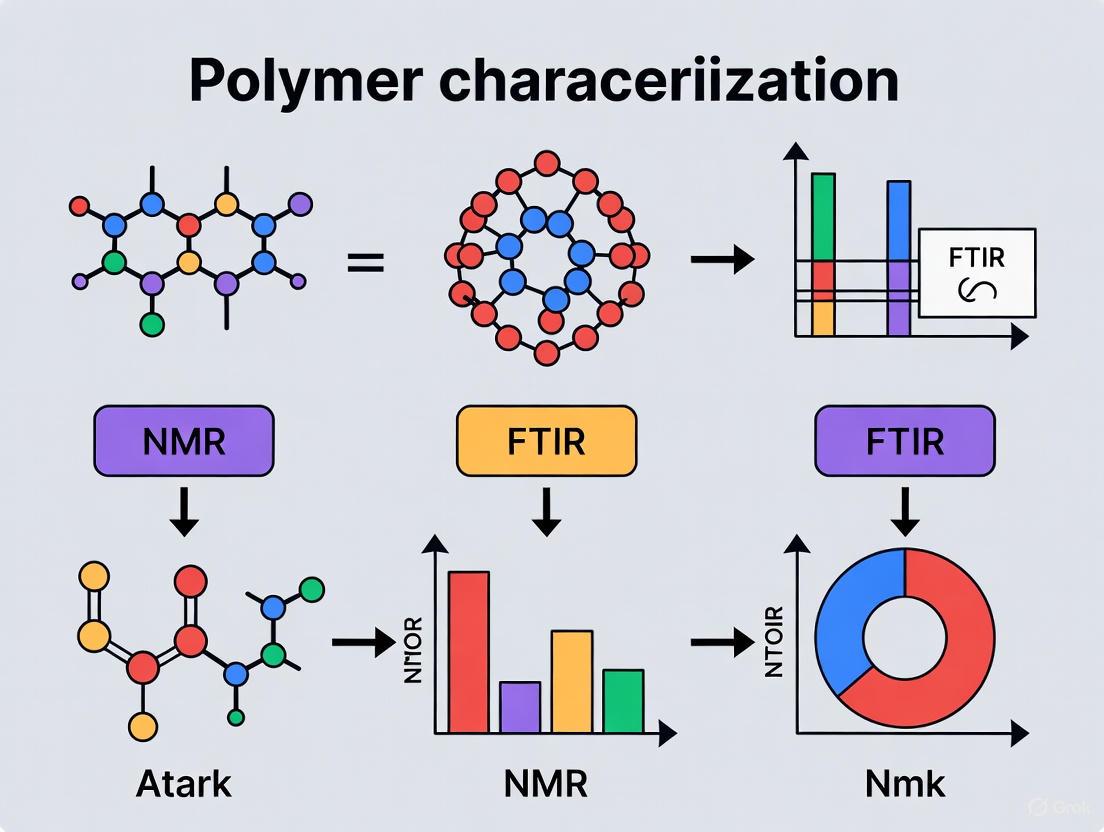

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision pathway for selecting the appropriate NMR experiment based on polymer solubility and the structural information required.

Diagram Title: Polymer NMR Analysis Decision Workflow

NMR spectroscopy is an indispensable tool in the polymer scientist's arsenal, providing unparalleled insights into backbone structure, tacticity, composition, and molecular weight. The protocols outlined herein—from routine solution-state analysis to advanced solid-state techniques—form a foundation for the comprehensive characterization of polymeric materials. For pharmaceutical researchers, these methods are particularly vital for ensuring the quality, performance, and safety of polymeric excipients and drug delivery systems. By integrating these NMR strategies with other characterization techniques like FTIR, scientists can achieve a holistic understanding of polymer structure-property relationships, thereby driving innovation in drug development and material science.

The Critical Role of Polymer Characterization in Drug Delivery and Biomedical Applications

Polymer characterization is a foundational discipline in the advancement of modern drug delivery and biomedical applications. It provides the critical data necessary to understand the relationship between a polymer's physical/chemical structure and its performance in a biological context. Techniques such as Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy are indispensable for elucidating chemical structures, confirming successful synthesis, and ensuring batch-to-batch consistency, which is vital for both research and regulatory compliance [18] [19]. Without thorough characterization, the development of reliable and effective polymeric drug carriers—such as nanoparticles, hydrogels, and implants—would be severely hampered. This document outlines key application notes and detailed experimental protocols for characterizing polymers using FTIR and NMR, providing a practical guide for researchers and scientists in the field.

Application Notes: Key Characterization Techniques and Data

FTIR Spectroscopy for Functional Group Analysis and Drug-Polymer Interaction

FTIR spectroscopy functions by exposing a sample to infrared light, which causes chemical bonds to vibrate at specific frequencies; the resulting absorption spectrum serves as a molecular fingerprint for the material [20]. In drug delivery, it is extensively used to identify functional groups, monitor polymerization reactions, and analyze degradation processes [19].

Note 1: Confirming Polymer-Drug Encapsulation A primary application is verifying the successful encapsulation of a drug within a polymer matrix and identifying any potential chemical interactions. As shown in a study on chitosan hydrogels for methyl orange (a model drug) encapsulation, FTIR can confirm effective absorption by showing characteristic peaks of both the polymer and the drug without significant peak shifts, indicating physical encapsulation rather than chemical reaction. The study reported an optimum effective absorbance of 4.34% for a specific hydrogel formulation (Td50Ti60) [21].

Note 2: Verification of Polymer Synthesis FTIR is crucial for confirming the successful synthesis of new polymers. For instance, in the synthesis of a novel homopolymer (poly(2MPAEMA)) and its copolymer with methyl methacrylate (MMA), FTIR spectroscopy was used alongside NMR for structural verification [22].

Table 1: Key FTIR Absorption Bands for Common Functional Groups in Biomedical Polymers

| Functional Group | Vibration Mode | Typical Wavenumber Range (cm⁻¹) | Polymer Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| O-H / N-H | Stretching | 3200–3600 [20] | Chitosan, Poly(2MPAEMA) [21] [22] |

| C=O (Carbonyl) | Stretching | ~1700 [20] [22] | Poly(lactic acid), PLGA, Poly(2MPAEMA) [22] [18] |

| C-O | Stretching | 1000–1300 | PLGA, Poly(2MPAEMA) [22] |

| C-H | Stretching | 2850–3000 | Present in most organic polymers [22] |

| C-N | Stretching | 1000–1350 | Poly(2MPAEMA) [22] |

NMR Spectroscopy for Structural Elucidation and Quantification

NMR spectroscopy provides unparalleled detail on the molecular structure, composition, and dynamics of polymers in solution [18] [19]. It is the primary method for monitoring monomer conversion and the "livingness" of controlled polymerizations [18].

Note 1: Structural Determination of Novel Monomers and Polymers NMR is essential for confirming the chemical structure of newly synthesized monomers and polymers. For example, the successful synthesis of the 2MPAEMA monomer and its subsequent polymerization was verified using ¹H and ¹³C NMR spectroscopy [22].

Note 2: Quantification of Drug Loading and Conjugation When a drug molecule is conjugated to a polymer chain, NMR can be used to quantify the success of this reaction. By comparing the integration values of characteristic peaks from the drug and the polymer backbone, researchers can calculate drug loading efficiency. This is frequently employed in systems like PEG-PLGA drug conjugates [18].

Note 3: Determining Molecular Weight with DOSY Diffusion-ordered NMR spectroscopy (DOSY) is a powerful technique for estimating the molecular weight of polymers. It works by separating NMR signals based on the diffusion coefficients of different species in solution, which correlate with their size [18].

Table 2: Key NMR Signals for a Model Polymer (e.g., 2MPAEMA-co-MMA Copolymer) [22]

| Proton Type | Chemical Shift δ (ppm) | Structural Information |

|---|---|---|

| -OCH₃ (MMA unit) | ~3.6 | Confirms incorporation of MMA monomer. |

| -OCH₃ (Aromatic) | ~3.8 | Confirms integrity of methoxyphenyl group. |

| -CH₂- (Backbone) | ~1.8-2.0 | Methylene protons from the polymer main chain. |

| -CH₃ (Backbone) | ~0.8-1.2 | Terminal methyl groups from the polymer backbone. |

| Aromatic Protons | ~6.8-7.2 | Confirms presence of the aromatic ring in 2MPAEMA. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: FTIR Analysis of a Drug-Loaded Polymeric Hydrogel

This protocol describes the characterization of a chitosan hydrogel loaded with methyl orange, based on the research by Nordin et al. [21].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Hydrogel Synthesis: Prepare an acidic chitosan polyelectrolyte solution by dissolving chitosan powder in distilled water and acetic acid (pH ~2.8-3.1). Adjust the pH to ~5.1 using 1M NaOH to protonate most amine groups. Perform cathodic electrodeposition using copper plate electrodes to deposit the hydrogel [21].

- Drug Loading: Immerse the deposited hydrogel in a solution of methyl orange (model drug) for a specified duration (e.g., 60 minutes) to allow for encapsulation [21].

- FTIR Sample Handling: For the solid hydrogel, use an Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) accessory. Ensure the sample is in direct contact with the ATR crystal. For powder samples, the KBr pellet method can be used.

2. Instrumentation and Data Acquisition:

- Use an FTIR spectrometer (e.g., PerkinElmer Spectrum Two).

- Set the scanning range to 4000–450 cm⁻¹ [22].

- Set the resolution to 4 cm⁻¹ and accumulate 32 scans per spectrum to ensure a good signal-to-noise ratio.

3. Data Analysis:

- Identify the characteristic peaks of chitosan: a broad O-H/N-H stretch around 3200-3600 cm⁻¹, C-H stretches, and the C=O stretch in amide I.

- Identify the characteristic peaks of methyl orange (e.g., S=O stretch).

- Compare the spectrum of the drug-loaded hydrogel with those of the pure polymer and the pure drug. The presence of both sets of peaks without significant shifting confirms successful encapsulation.

Protocol 2: NMR Structural Analysis and Molecular Weight Estimation of a Copolymer

This protocol is adapted from procedures used to characterize novel copolymers like 2MPAEMA-co-MMA [22] [18].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Dissolve approximately 10-20 mg of the purified copolymer (e.g., 2MPAEMA-co-MMA) in 0.6-0.7 mL of a suitable deuterated solvent (e.g., Chloroform-d, DMSO-d6).

- Transfer the solution to a clean, dry NMR tube.

2. 1D NMR Data Acquisition (¹H and ¹³C):

- Use a 400 MHz NMR spectrometer (e.g., Bruker TopSpin).

- For ¹H NMR, set the number of scans to 16 or more, depending on concentration.

- For ¹³C NMR, which is less sensitive, set the number of scans to 1024 or more.

- Run the experiment and process the data (Fourier transformation, phasing, and baseline correction).

3. 2D NMR for Advanced Structural Confirmation:

- Perform two-dimensional experiments such as COSY (Correlation Spectroscopy), HSQC (Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence), and HMBC (Heteronuclear Multiple Bond Correlation) to resolve complex spectra and confirm atomic connectivity and conjugation sites [18].

4. DOSY for Molecular Weight Estimation:

- Run a DOSY experiment using a pulsed field gradient sequence.

- Process the data using appropriate software to generate a diffusion-ordered spectrum.

- Correlate the measured diffusion coefficients with molecular weight using calibration standards or established algorithms [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Polymer Synthesis and Characterization in Drug Delivery

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | Natural biopolymer for hydrogels & nanoparticles; biocompatible and biodegradable. | Forming electrodeposited hydrogels for drug encapsulation [21]. |

| PLGA (Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)) | Synthetic, biodegradable copolymer for controlled-release nanoparticles. | Creating nanocarriers for sustained drug delivery [18]. |

| Azobis(isobutyronitrile) (AIBN) | Radical initiator for free-radical polymerization reactions. | Initiating synthesis of poly(2MPAEMA) and its copolymer [22]. |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., CDCl₃) | Solvent for NMR spectroscopy, providing a signal for lock and reference. | Dissolving polymer samples for ¹H and ¹³C NMR analysis [22]. |

| Methyl Methacrylate (MMA) | A common vinyl monomer for creating copolymers with tunable properties. | Synthesizing 2MPAEMA-co-MMA copolymer [22]. |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Polymer Characterization Workflow

Nanoparticle Development Pathway

Complementary Nature of FTIR and NMR in a Comprehensive Analytical Workflow

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopies represent two cornerstone technologies for molecular structure determination in chemical and pharmaceutical research. While each technique provides valuable standalone information, their integration creates a powerful synergistic workflow that significantly enhances analytical capabilities. This application note details the complementary relationship between FTIR and NMR spectroscopy within comprehensive analytical workflows, with specific emphasis on polymer characterization and pharmaceutical development. We provide experimental protocols, performance data, and practical implementation guidelines to enable researchers to leverage the combined power of these techniques for advanced material characterization.

The fundamental complementarity arises from the different physical principles each technique exploits. FTIR spectroscopy probes molecular vibrational transitions, providing exceptional sensitivity to functional groups and chemical bonds [23]. In contrast, NMR spectroscopy detects magnetic properties of atomic nuclei, yielding detailed information about atomic connectivity, molecular conformation, and stereochemistry [23]. This informational synergy is particularly valuable for characterizing complex molecular systems where neither technique alone provides sufficient structural insight.

Technical Comparison and Synergistic Benefits

Fundamental Principles and Information Content

FTIR spectroscopy measures the absorption of infrared radiation by molecular vibrations, generating a "molecular fingerprint" that identifies specific functional groups like -OH, -NH, C=O, and C-H moieties [23]. The technique excels at rapid identification of organic compounds, polymers, and materials with well-defined vibrational modes, requiring minimal sample preparation and being applicable to solids, liquids, and gases [23]. However, FTIR provides limited information about atomic connectivity or molecular architecture.

NMR spectroscopy relies on the interaction between atomic nuclei (typically ¹H and ¹³C) and external magnetic fields when exposed to radiofrequency radiation [23]. The resulting chemical shifts are exquisitely sensitive to the local electronic environment, providing detailed data about molecular structure, including carbon-hydrogen frameworks, stereochemistry, and dynamics [23]. While requiring more specialized sample preparation (often dissolution in deuterated solvents), NMR delivers unparalleled structural resolution, including the ability to differentiate between isomers.

Quantitative Performance Enhancement

Recent research demonstrates that combining ¹H NMR and IR spectroscopy significantly outperforms either technique alone for automated structure verification (ASV). In challenging studies involving 99 similar isomer pairs, the combined approach dramatically reduced unsolved structures across all confidence levels [24] [25].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Individual and Combined Spectroscopic Techniques for Structure Verification

| True Positive Rate | Technique | Unsolved Pairs | Relative Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| 90% | NMR alone | 27-49% | Baseline |

| 90% | IR alone | 27-49% | Baseline |

| 90% | NMR + IR | 0-15% | 69-100% decrease |

| 95% | NMR alone | 39-70% | Baseline |

| 95% | IR alone | 39-70% | Baseline |

| 95% | NMR + IR | 15-30% | 57-62% decrease |

This performance enhancement stems from the complementary structural information provided by each technique. While NMR excels at determining atomic connectivity and spatial relationships, IR spectroscopy provides superior functional group identification and sensitivity to bond characteristics [24] [25]. The combination effectively covers both atomic-level and bond-level structural features, creating a more comprehensive analytical picture.

Experimental Protocols

Integrated FTIR-NMR Workflow for Polymer Characterization

The following workflow describes a standardized approach for comprehensive polymer characterization using combined FTIR and NMR techniques:

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Polymer Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated chloroform (CDCl₃) | NMR solvent for soluble polymers | Provides deuterium lock signal; dissolves most organic polymers |

| Deuterated DMSO (DMSO-d₆) | NMR solvent for polar polymers | Dissolves challenging polar polymers; may hydrogen bond with sample |

| Potassium bromide (KBr) | FTIR sample preparation | Creates transparent pellets for transmission FTIR measurements |

| ATR crystal (diamond, ZnSe) | FTIR sampling interface | Enables direct measurement of solid polymers without preparation |

| Tetramethylsilane (TMS) | NMR chemical shift reference | Provides 0 ppm reference point for ¹H and ¹³C NMR spectra |

| Cross-polarization magic angle spinning (CP-MAS) probe | Solid-state NMR accessory | Enables high-resolution NMR of insoluble polymer systems |

Protocol 1: Sample Preparation and Data Collection

Sample Isolation and Preparation

- For soluble polymers: Prepare a 5-20 mg/mL solution in appropriate deuterated solvent (CDCl₃ for non-polar polymers, DMSO-d₆ for polar systems) for NMR analysis. Retain a portion of the neat sample for FTIR analysis.

- For insoluble polymers/cross-linked systems: Gently grind to fine powder using agate mortar and pestle. Split for FTIR (ATR measurement) and solid-state NMR (pack into rotor) analyses.

FTIR Spectral Acquisition

- Solid samples: Using ATR-FTIR spectrometer, place powdered sample directly on diamond crystal and apply consistent pressure with anvil. Acquire spectrum from 4000-400 cm⁻¹ with 4 cm⁻¹ resolution, 32 scans.

- Solution samples: For transmission mode, prepare KBr pellet containing 1% sample by weight or use liquid cell with appropriate pathlength. Acquire spectrum using same parameters.

- Data processing: Apply atmospheric suppression (CO₂, H₂O), baseline correction, and normalization to strongest band.

NMR Spectral Acquisition

- Solution-state NMR: For soluble polymers, transfer 600 μL of prepared solution to 5 mm NMR tube. Acquire ¹H NMR spectrum (128 scans) and ¹³C NMR spectrum (1024 scans) using standard pulse sequences at appropriate temperature (typically 25°C).

- Solid-state NMR: For insoluble systems, pack powdered sample into 4 mm ZrO₂ rotor. Acquire ¹³C CP-MAS spectrum with proton decoupling, using contact time of 2 ms, MAS rate of 10-12 kHz, and recycle delay of 3-5 seconds.

Protocol 2: Data Integration and Interpretation

Initial FTIR Analysis

- Identify major functional groups present: hydroxyl (3200-3600 cm⁻¹), carbonyl (1650-1780 cm⁻¹), aromatic (1500-1600 cm⁻¹), ether (1000-1300 cm⁻¹).

- Note polymer-specific signatures: silicone (1000-1100 cm⁻¹, Si-O-Si), polyamide (3300 cm⁻¹ N-H, 1640 cm⁻¹ amide I), polyester (1720 cm⁻¹ ester C=O).

Comprehensive NMR Analysis

- Assign ¹H NMR chemical shifts to proton environments: aliphatic (0.9-1.5 ppm), α-to-unsaturation/heteroatom (1.5-3.0 ppm), ether (3.0-4.5 ppm), vinyl/aromatic (4.5-8.0 ppm).

- Interpret ¹³C NMR spectrum: identify carbonyl (160-185 ppm), aromatic (110-150 ppm), aliphatic (0-50 ppm) carbons.

- For copolymers: determine monomer ratio from integration of distinctive signals; assess sequence distribution from dyad/triad intensities.

Data Correlation and Structural Validation

- Cross-verify functional group identification: confirm carbonyl type (ester vs. acid vs. amide) detected by FTIR with specific chemical shifts in NMR.

- Resolve structural ambiguities: use NMR connectivity information to interpret FTIR bands that may have multiple assignments.

- Generate consensus structural model consistent with all spectroscopic data.

Automated Structure Verification Protocol

For high-throughput applications in pharmaceutical development, the following ASV protocol leveraging both techniques has been validated:

Diagram 1: ASV workflow combining FTIR and NMR data

Protocol 3: Automated Structure Verification Workflow

Candidate Structure Generation

- Input all plausible isomeric structures based on reaction mechanism knowledge or prediction software [25].

- Ensure molecular weight consistency with MS data if available.

Theoretical Spectrum Calculation

- Perform DFT calculations (B3LYP/6-31G* level) to predict ¹H NMR chemical shifts and IR spectra for all candidate structures.

- Apply scaling factors to calculated frequencies to improve agreement with experimental data.

Experimental Spectral Acquisition

- Acquire high-quality FTIR spectrum (ATR mode, 4 cm⁻¹ resolution) using minimal sample (<1 mg).

- Obtain ¹H NMR spectrum (500 MHz or higher, 16-64 scans) in appropriate deuterated solvent.

Automated Scoring and Decision

- Apply IR.Cai algorithm to compare experimental and calculated IR spectra, generating match scores (0-1 scale) [25].

- Apply DP4* algorithm (modified to exclude labile protons) to compare NMR data, generating probability scores [25].

- Calculate combined score using Bayesian integration of IR and NMR probabilities.

- Classify structure as verified if top candidate score exceeds 95% probability and score difference to next candidate >0.3.

Application-Specific Workflows

Polymer Nanocomposite Characterization

The complementary nature of FTIR and NMR is particularly valuable for characterizing complex polymer nanocomposites, where understanding polymer-filler interfaces is critical for material performance [26].

Protocol 4: Interface Analysis in Nanocomposites

Surface Interaction Mapping

- Employ ATR-FTIR to detect specific interactions: hydrogen bonding between silica surface OH groups and polymer oxygen atoms [26].

- Utilize solid-state NMR to quantify interfacial region dynamics through T₁ρ relaxation measurements.

Filler Dispersion Assessment

- Apply FTIR microscopy to map filler distribution in polymer matrix with ~10 μm spatial resolution.

- Use NMR diffusion ordered spectroscopy (DOSY) to detect restricted polymer chain mobility near filler surfaces.

Cross-linking Density Determination

- Monitor FTIR band intensity changes (e.g., C=C disappearance in curing reactions).

- Quantify cross-link density via NMR T₂ relaxation measurements, correlating with mechanical properties.

Pharmaceutical Quality Control

In pharmaceutical QA/QC workflows, FTIR and NMR play complementary roles in raw material identification, polymorph screening, and formulation analysis [27].

Diagram 2: Pharmaceutical raw material verification workflow

Protocol 5: Pharmaceutical Raw Material Identification

FTIR Rapid Screening

- Acquire ATR-FTIR spectrum of incoming raw material (≤2 minutes analysis time).

- Compare to reference spectrum in validated spectral library.

- Apply correlation algorithms with acceptance threshold ≥0.95 match.

NMR Confirmatory Analysis

- For materials passing FTIR screen, prepare solution in deuterated DMSO.

- Acquire ¹H NMR spectrum with quantitative parameters (30° pulse, 5T₁ relaxation delay).

- Verify identity through chemical shift pattern matching and integral ratios.

Impurity Profiling

- Utilize FTIR for specific functional group contaminants (silicones, polyglycols).

- Employ NMR for structural analogs and isomeric impurities not distinguishable by FTIR.

The strategic integration of FTIR and NMR spectroscopy creates a comprehensive analytical workflow that significantly surpasses the capabilities of either technique in isolation. As demonstrated through the protocols and performance data presented, this combined approach enables researchers to address complex characterization challenges with greater confidence and efficiency. The complementary information provided – functional group identification from FTIR and atomic-level structural details from NMR – proves particularly valuable for advanced material development, pharmaceutical quality control, and research requiring complete molecular understanding. Implementation of the integrated workflows described in this application note will enhance analytical capabilities across multiple domains, from polymer science to drug development.

Practical Applications: Deformulation, Stability, and Drug Delivery Analysis

Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy serves as a powerful analytical technique for identifying molecular composition and structure by measuring how a sample absorbs infrared light [1]. Within polymer science, its versatility provides critical insights for research and development, manufacturing, and quality control, making it indispensable for analyzing complex polymeric materials [1]. This application note details specific FTIR methodologies for monitoring two fundamental polymer processes: polymerization reactions and degradation pathways. The content is structured to provide researchers with clear experimental protocols, key data interpretation guidelines, and essential resource information, supporting advanced research within a comprehensive thesis on polymer characterization.

Application Note: Monitoring Polymerization Reactions

Principle and Key Spectral Markers

FTIR spectroscopy is exceptionally suited for studying polymerization reactions in real-time, as it directly tracks the consumption of monomers and the formation of polymer chains through changes in characteristic functional group vibrations [28]. The initiation, propagation, and termination steps of the reaction can be followed by monitoring specific infrared absorption bands [28].

Table 1: Key FTIR Spectral Markers for Monitoring Cyanoacrylate Polymerization

| Wavenumber (cm⁻¹) | Assignment | Spectral Change During Polymerization | Chemical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 804 | C=C bending vibration | Decrease | Consumption of C=C bonds in the monomer [29] |

| 858 | C-C stretching vibration | Increase | Formation of the polymer backbone (CH₂-C-CH₂ bonds) [29] |

| 1254 | C-H bending vibration | Increase | Growth of polymer chain structure [29] |

| 1290 | C-H vibration associated with C=C group | Decrease | Disappearance of monomeric structures [29] |

Experimental Protocol: Time-Resolved Monitoring of Cyanoacrylate Curing

1. Objective: To monitor the curing kinetics of an ethyl cyanoacrylate adhesive via time-resolved FTIR spectroscopy [29].

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Ethyl cyanoacrylate adhesive.

- Potassium bromide (KBr) windows or a suitable IR-transparent crystal (e.g., diamond ATR crystal).

3. Instrumentation:

- FTIR spectrometer (e.g., Jasco FT-IR-6300 or equivalent).

- For macro-experiments: Standard sample holder.

- For micro-experiments: FTIR microscope with a linear array detector (e.g., Jasco IRT-7000) [29].

4. Macro-Scale Method (Bulk Reaction Kinetics): * Sample Preparation: Spread the cyanoacrylate adhesive uniformly on a 10x10 mm KBr window. Carefully place a second window on top to create a thin, uniform layer [29]. * Data Collection: * Collect a background spectrum (e.g., 256 scans) [29]. * Initiate data acquisition immediately after sample preparation. * Collect sample spectra at a resolution of 8 cm⁻¹ with a small number of scans per spectrum (e.g., 4 scans) to achieve a high time resolution (e.g., every 4 seconds) [29]. * Continue acquisition until the reaction is complete (e.g., 30 minutes) [29].

5. Micro-Scale Method (Spatially Resolved Kinetics): * Sample Preparation: Prepare the adhesive sample as for the macro experiment [29]. * Data Collection: * Use the FTIR microscope in "lattice mapping" mode. * Define a measurement grid (e.g., 16x16 points) over the area of interest. * Collect spectra at each point with 8 cm⁻¹ resolution and 4 co-added scans. * Acquire complete maps at regular time intervals (e.g., every 20 seconds) for the reaction duration [29].

6. Data Analysis:

- Plot the absorbance values of key peaks (e.g., 1254 cm⁻¹ for polymer formation and 1290 cm⁻¹ for monomer consumption) as a function of time [29].

- Fit the kinetic curves to determine reaction parameters such as the reaction rate constant and half-life [29].

Application Note: Investigating Polymer Degradation Processes

Principle and Degradation Indexes

Polymer degradation, induced by environmental factors like UV light, heat, and oxygen, leads to chemical changes such as chain scission and the formation of new functional groups [30]. FTIR spectroscopy is highly effective in tracking these changes, particularly through the calculation of degradation indexes [30].

Table 2: Key FTIR Indexes for Quantifying Polymer Degradation

| Index Name | Formula (Wavenumbers in cm⁻¹) | Chemical Significance | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbonyl Index (CI) | ( \frac{A{C=O}}{A{ref}} ) | Formation of carbonyl groups (ketones, aldehydes, carboxylic acids) due to oxidation [30]. | Polyethylene (PE) & Polypropylene (PP): (A{C=O}) ~1715 cm⁻¹, (A{ref}) ~1465 or 2720 cm⁻¹ [30]. |

| Hydroxyl Index (HI) | ( \frac{A{O-H}}{A{ref}} ) | Formation of hydroxyl or hydroperoxyl groups [30]. | PE & PP: (A{O-H}) ~3400 cm⁻¹, (A{ref}) as for CI [30]. |

| Carbon-Oxygen Index (COI) | ( \frac{A{C-O}}{A{ref}} ) | Formation of C-O bonds in esters, alcohols, and ethers [30]. | PE & PP: (A{C-O}) ~1150-1050 cm⁻¹, (A{ref}) as for CI [30]. |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Natural Weathering of Polypropylene Microplastics

1. Objective: To evaluate the chemical degradation of naturally weathered polypropylene (NWPP) microplastics using ATR-FTIR spectroscopy [31] [30].

2. Materials:

- Naturally weathered microplastics collected from the environment (e.g., beach sediments) [31].

- Pristine polymer samples for baseline comparison [30].

3. Instrumentation:

4. Method: * Sample Collection and Preparation: Collect environmental samples following standardized protocols for microplastics (e.g., density separation in NaCl solution, filtration, drying) [31]. For ATR-FTIR, ensure the sample surface makes good contact with the crystal. * Data Collection: * Acquire spectra over a wavenumber range of 4000–500 cm⁻¹ [30]. * Use a spectral resolution of 4 cm⁻¹ and accumulate 32 scans per spectrum to ensure a high signal-to-noise ratio [30]. * Advanced Analysis: * Calculate the Carbonyl (CI), Hydroxyl (HI), and Carbon-Oxygen (COI) indexes for all samples [30]. * Employ second derivative spectroscopy to resolve overlapping bands in the 1750–1500 cm⁻¹ region, which can reveal specific degradation products like vinyl and carboxylate groups [31].

5. Data Interpretation:

- An increase in CI, HI, and COI values indicates a higher degree of oxidation and weathering [30].

- The appearance of new bands in the hydroxyl region (3600–3200 cm⁻¹) and the carbonyl/ carboxylate region (1750–1500 cm⁻¹) provides evidence of specific oxidative pathways [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for FTIR Polymer Analysis

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| ATR Crystals | Enables direct measurement of solids and liquids with minimal preparation by generating an evanescent wave for analysis [32] [1]. | Diamond (durable, broad range), Germanium (high refractive index for hard materials) [1]. |

| KBr Windows/Pellets | Used in transmission FTIR for creating thin films or for preparing solid samples dispersed in a KBr matrix [29]. | Windows for liquid cells; powder for pressing pellets. |

| Polymer Standards | Used for instrument validation, quantitative calibration, and building identification libraries [32]. | Certified polystyrene for validation; pristine PE, PP, PS for degradation studies [32] [30]. |

| Saturated NaCl Solution | Used in density separation for extracting microplastics from environmental samples like sediments [31]. | Preparation of homogenized sediment samples for microplastic analysis [31]. |

| Blocking Agents | Chemically or thermally labile compounds used to control the initiation of specific polymerization reactions (e.g., for urethanes) [28]. | Various agents that deblock at different temperatures to control reaction onset [28]. |

FTIR spectroscopy, with its diverse sampling modalities and powerful data analysis capabilities, is a cornerstone technique for the in-depth study of polymer reactions and stability. The protocols outlined herein for monitoring polymerization kinetics and quantifying degradation provide a robust framework for research. When integrated with other characterization techniques such as NMR, TGA, and rheology, FTIR significantly enhances the comprehensive understanding of polymer properties and behavior, forming a critical component of modern polymer characterization methodology.

NMR for Determining Monomer Composition, Copolymer Sequences, and Branching

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy serves as a powerful analytical technique for determining the intricate architectural details of polymers. Its capability to provide insights at the molecular level makes it indispensable for elucidating monomer composition, sequencing in copolymers, and branching structures, all of which are critical for understanding polymer properties and behavior. This article provides detailed application notes and protocols for employing NMR in polymer characterization, framed within the broader context of a thesis on polymer characterization methods. It is structured to offer researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with both foundational knowledge and advanced, practical methodologies.

Application Note 1: Quantitative Determination of Monomer Composition

Principle and Scope

Quantitative NMR (qNMR) enables precise determination of monomer ratios in copolymers by integrating characteristic proton (¹H) or carbon (¹³C) signals unique to each monomer unit. The technique relies on the direct proportionality between the signal intensity and the number of nuclei contributing to that signal [33]. This application is vital for quality control, verifying synthesis outcomes, and correlating composition with material properties.

Experimental Protocol for qNMR

Materials and Reagents:

- Polymer Sample: 10-50 mg for high-field NMR.

- Deuterated Solvent: Suitable for dissolving the polymer (e.g., CDCl₃, THF-d₈, or tetrachloroethane-d₂ for high-temperature analysis) [34] [33].

- Internal Standard: A certified quantitative standard, such as Dimethyl sulfone (DMSO₂), with a known, precise concentration [35] [33].

Instrumentation and Parameters:

- Spectrometer: High-field spectrometer (e.g., 400 MHz or higher) is recommended. The use of a cryoprobe significantly enhances sensitivity, reducing experiment time [34].

- Key Acquisition Parameters:

- Pulse Delay (d1): Must be sufficiently long (≥ 60 seconds for ¹³C NMR) to allow for complete spin-lattice relaxation (T1) and ensure quantitative conditions [34] [33].

- Number of Scans: Adjusted based on sample concentration and instrument sensitivity to achieve an adequate signal-to-noise ratio.

- Acquisition Temperature: Elevated temperatures (e.g., 393 K) are often used for polyolefins to increase solubility and reduce solution viscosity [34].

Sample Preparation:

- Accurately weigh the polymer sample (~45 mg for ¹³C NMR) into a vial.

- Add the deuterated solvent (e.g., tetrachloroethane-d₂) to prepare a homogeneous solution with a known concentration.

- Add a precise amount of the internal standard (e.g., DMSO₂) to the solution [33].

- Transfer the solution to a standard 5 mm NMR tube for analysis.

Data Analysis and Quantification:

- Process the acquired spectrum with appropriate phase and baseline corrections.

- Identify and integrate the resolved signals corresponding to each monomer unit.

- The concentration of the monomer unit, ( Cu ), is calculated using the formula:

( Cu = Cr \times (Au / Ar) \times (nr / nu) )

Where:

- ( Cr ) = concentration of the internal standard

- ( Au ) = integral of the monomer signal

- ( Ar ) = integral of the internal standard signal

- ( nr ) = number of protons in the internal standard signal

- ( nu ) = number of protons in the monomer signal [33]

Table 1: Detection Limits for Common Polymers by qNMR

| Polymer | Solvent | Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | Key Proton Signals (δ, ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene (PS) | CDCl₃ | 0.2 - 1 µg/mL [33] | Aromatic 6.2-7.2 |

| Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) | THF-d₈ | 1 - 8 µg/mL [33] | Methylene 4.5-3.8 |

| Polybutadiene-cis (PB) | CDCl₃ | 0.01 - 1 µg/mL [33] | Olefinic 5.0-5.8 |

| Polyisoprene-cis (PI) | CDCl₃ | 0.01 - 1 µg/mL [33] | Olefinic 5.0-5.8 |

| Polyurethane (PU) | THF-d₈ | 1 - 10 µg/mL [33] | Varies by type |

Diagram 1: qNMR Workflow for Monomer Composition.

Application Note 2: Elucidating Copolymer Sequences

Principle and Scope

The sequence distribution of monomers (e.g., random, alternating, block, gradient) in a copolymer profoundly affects its physical properties. NMR can distinguish these sequences by detecting subtle changes in the chemical environment of nuclei influenced by neighboring units, a phenomenon known as the "sequence effect" [36] [37].

Experimental Protocol for Sequence Analysis

Method 1: Advanced ¹³C NMR Analysis

- Technique: High-resolution ¹³C NMR spectroscopy.

- Procedure: Analyze the carbonyl or quaternary carbon region, which often exhibits higher sensitivity to sequence distribution. Complex spectra can be interpreted using multivariate analysis, such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Partial Least-Squares (PLS) regression, to predict chemical composition and sequence without manual peak assignment [37].

Method 2: Machine Learning-Enhanced NMR

- Technique: Correlating NMR data with machine learning (ML) models.

- Procedure:

- Input Representation: Represent the copolymer using Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) of its monomers. Convert these into numerical feature vectors (e.g., using Morgan fingerprints) that capture compositional and sequence information [36].

- Model Training: Train machine learning models (e.g., Feed-Forward Neural Networks (FFNN), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), or Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN)) using known copolymer structures and their corresponding NMR data or target properties.

- Prediction: Use the trained model to predict properties or sequence-dependent features for new copolymers based on their NMR-derived inputs [36].

Table 2: Machine Learning Models for Copolymer NMR Analysis

| Model | Acronym | Key Feature | Application in Sequence Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feed-Forward Neural Network | FFNN | Uses weighted monomer fingerprints | Considers composition, ignores sequence [36] |

| Convolutional Neural Network | CNN | Processes stacked monomer vectors | Explicitly considers sequence distribution [36] |

| Recurrent Neural Network | RNN | Analyzes sequential data | Models monomer sequence directly [36] |

| Fusion Model (FFNN/RNN) | - | Combines multiple architectures | Leverages both composition and sequence [36] |

Application Note 3: Detection and Quantification of Branching

Principle and Scope

Branching significantly alters polymer properties like crystallinity, density, and melt behavior. ¹³C NMR is the primary technique for quantifying branching types and frequency in polymers such as polyethylene (PE). The chemical shift of carbon atoms near a branch point (e.g., methine, Cα, Cβ) is diagnostic of branch length [34].

Experimental Protocol for Branching Analysis in Polyethylene

Materials and Instrumentation:

- Polymer Sample: Polyethylene (e.g., LDPE, LLDPE, HDPE).

- Solvent: Tetrachloroethane-d₂, stabilized with BHT, for operation at high temperature (393 K) [34].

- Instrument: High-field NMR spectrometer (e.g., 400 MHz) equipped with a high-temperature cryoprobe for enhanced sensitivity [34].

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a concentrated solution (~45 mg/mL) of the polyethylene sample in tetrachloroethane-d₂.

- Ensure complete dissolution at high temperature.

Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Acquire a quantitative ¹³C NMR spectrum with a sufficiently long pulse delay (d1 ≥ 60 s) to ensure complete relaxation for accurate integration [34].

- Standard Method (Methine Carbon Analysis): Identify branches by integrating the methine carbon signals (branch points). However, this method cannot distinguish between branches with 6 or more carbon atoms (e.g., hexyl branches vs. Long Chain Branches (LCB)) as their methine carbons resonate at the same chemical shift [34].

- Enhanced Method (Cβ Carbon Analysis):

- For more critical discrimination, analyze the resonances of methylene carbons in the β-position relative to the branch point.

- The Cβ carbon of the branch itself is more sensitive to the branch length, allowing for better discrimination between hexyl-type Short Chain Branches (SCB) and LCB.

- This method can provide up to a three-fold enhancement in detection sensitivity for LCB compared to methine carbon analysis [34].

Table 3: ¹³C NMR Chemical Shifts for Branching in Polyethylene

| Branch Type | Branch Length (C atoms) | Methine Carbon (δ, ppm) | Cβ Carbon (δ, ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methyl | 1 | ~34.0 | Not Applicable |

| Ethyl | 2 | ~37.5 | ~26.5 |

| Butyl | 4 | ~34.5 | ~26.5 |

| Hexyl | 6 | ~34.5 | ~26.5 |

| Long Chain (LCB) | ≥ 6 | ~34.5 | ~26.8-26.9 [34] |

Diagram 2: NMR Workflow for PE Branching Analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Polymer NMR Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Chloroform (CDCl₃) | Common solvent for NMR sample preparation | Dissolving PS, PB, PI, and PLA for analysis [35] [33] |

| Deuterated Tetrahydrofuran (THF-d₈) | Solvent for polymers insoluble in CDCl₃ | Dissolving PVC and PU for qNMR quantification [35] [33] |

| Deuterated 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane | High-bopoint solvent for high-temperature NMR | Analyzing polyolefins like polyethylene at 393 K [34] |

| Dimethyl Sulfone (DMSO₂) | Internal standard for quantitative NMR (qNMR) | Precise concentration measurement of polymers in solution [35] [33] |

| Butylated Hydroxytoluene (BHT) | Antioxidant stabilizer | Added to solvents for high-temperature analysis to prevent polymer degradation [34] |

Integrated Characterization: The Synergy of NMR and FTIR

Within a comprehensive polymer characterization thesis, NMR and FTIR are highly complementary techniques. FTIR spectroscopy is often the starting point for rapid polymer identification and functional group analysis, requiring minimal sample preparation [20] [38]. It excels in detecting specific functional groups and can be used for the surface analysis of inorganic materials within polymer composites [20].

However, when deeper structural elucidation is required—such as quantifying monomer ratios, determining precise stereochemistry, or quantifying branching—NMR is the unequivocal technique [38]. It provides atomic-level resolution and quantitative data that FTIR cannot. Therefore, an effective characterization strategy often begins with FTIR for general identification, followed by targeted NMR analysis for detailed structural investigation. This synergistic approach leverages the strengths of both techniques to provide a complete picture of polymer structure.

Within the broader context of a thesis on polymer characterization methods, this application note provides a detailed protocol for analyzing thermosetting polyphenylene oxide (PPO) cross-linked with triallyl isocyanurate (TAIC). These copolymer systems have been identified as superior resin matrices for high-performance copper clad laminates (CCLs) in 5G network devices due to their exceptional dielectric properties, specifically an ultralow dielectric loss (Df) and low dielectric constant (Dk) at high frequencies [39] [40]. The performance of these materials is intrinsically linked to their cross-linked chemical structure and morphology. Therefore, this document outlines a comprehensive characterization workflow, leveraging Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) and Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy as core analytical techniques, to establish critical composition–process–structure–property relationships [41] [39].

Experimental Protocols

Materials and Sample Preparation

- Polymer Matrix: Methyl methacrylate-capped PPO oligomer (e.g., NORYL SA9000, Mn = 2300) [39] [40].

- Cross-linking Agent: Triallyl isocyanurate (TAIC) [39] [40].

- Free Radical Initiator: Bis(tert-butyldioxyisopropyl) benzene (e.g., BIPB) [39] [40].

- Reinforcement: Low-loss glass fabric (e.g., Style 2116) [39] [40].

- Solvent: Methyl Ethyl Ketone (MEK) [39] [40].

Preparation of PPO/TAIC Composite Laminates: The typical formulation involves a PPO to TAIC weight ratio of 1.33:1.0 [39] [40].

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve PPO resin, TAIC, and the BIPB initiator (e.g., at 1.0-2.0 parts per hundred parts of resin, phr) in MEK solvent.

- Prepreg Manufacturing: Impregnate the glass fabric with the prepared resin solution and dry to remove the solvent, resulting in a "prepreg."

- Lamination and Curing: Stack the prepregs and cure under heat and pressure (e.g., via hot-pressing) to initiate the free radical cross-linking reaction, forming the final laminate [39] [40].

Characterization Workflow

The following integrated workflow is recommended for a full characterization of the cross-linked system. Key techniques like NMR and FTIR are used in tandem to monitor the consumption of reactive groups and identify the final chemical structure.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Techniques

Protocol for Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Analysis

Objective: To determine the polymer structure, tacticity, and identify low molecular weight degradation by-products or unreacted components that can affect dielectric performance [42] [41].

Sample Preparation:

- For Solid-State NMR: Analyze cured laminate samples directly. Use Cross-Polarization Magic Angle Spinning (CP/MAS) to enhance signal and reduce line broadening from anisotropic interactions [43] [26].

- For Solution-State NMR: Dissolve uncured resin mixtures or extract soluble components from cured composites in deuterated chloroform (CDCl₃). For degradation studies, thermally degrade the polymer in an inert atmosphere and trap evolved gases in a CDCl₃ trap for analysis [41].

Data Acquisition:

- Instrumentation: High-field NMR spectrometer (e.g., 500 MHz).

- Parameters: Acquire ¹H and ¹³C NMR spectra. For quantitative analysis, use long relaxation delays (e.g., >5 times the longitudinal relaxation time T1) to ensure complete relaxation of nuclei between pulses [43].

Data Interpretation:

- Monitor the disappearance of the allyl proton signals (e.g., around 5.8-5.9 ppm and 5.1-5.3 ppm for TAIC) and the methacrylate vinyl protons of the PPO oligomer to track cross-linking conversion [41] [39].

- Identify by-products from initiator decomposition or polymer degradation, such as residual monomers or carbonyl sulfide from functionalized systems, which can act as polar impurities [41] [39].

Protocol for Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Analysis

Objective: To monitor the cross-linking reaction in real-time, identify functional groups, and confirm chemical modifications [41] [44].

Sample Preparation:

- Transmission Mode: Prepare thin, uncured polymer films on KBr windows.

- Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) Mode: Analyze cured laminate samples directly by pressing the material against the ATR crystal. This method is highly suitable for solid, cross-linked composites [41].

Data Acquisition:

- Instrumentation: FTIR spectrometer equipped with an ATR accessory.

- Parameters: Record spectra over a range of 4000–600 cm⁻¹ with a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹, averaging 16 scans per spectrum.

- In Situ Curing Analysis: Use a heated stage in the FTIR to monitor the decrease in the intensity of the C=C stretching band (∼1640 cm⁻¹) from TAIC and methacrylate groups during the cross-linking reaction [44].

Data Interpretation:

- The conversion of C=C bonds can be calculated by comparing the integrated area of the ∼1640 cm⁻¹ band to that of an internal reference band (e.g., the aromatic C–C stretch from PPO at ∼1500 cm⁻¹) that remains constant throughout the reaction [44].

- Post-curing, the spectrum should show a significant reduction or disappearance of the C=C band, indicating successful cross-linking [41] [44].

Results and Data Presentation

Dielectric and Thermal Properties

The efficacy of the cross-linking process, influenced by initiator concentration, directly impacts the final material properties. The following table summarizes key performance metrics.

Table 1: Dielectric and Thermal Properties of PPO/TAIC-Based Composites

| Initiator (BIPB) Content (phr) | Dielectric Constant (Dk) at 10 GHz | Dielectric Loss (Df) at 10 GHz | Glass Transition Temp. (Tg) [°C] | Decomposition Temp. (Td) [°C] | Primary Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|