Monomers and Polymerization Processes: From Molecular Design to Advanced Drug Delivery Applications

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of monomers and polymerization processes, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Monomers and Polymerization Processes: From Molecular Design to Advanced Drug Delivery Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of monomers and polymerization processes, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of polymer science, including monomer classification and step-growth versus chain-growth mechanisms. The content delves into advanced methodological approaches like emulsion and miniemulsion polymerization, highlighting their critical role in creating sophisticated drug delivery systems. It further addresses key industrial challenges such as residual monomer reduction and morphology control, and discusses validation techniques for characterizing polymeric products. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with cutting-edge applications and troubleshooting insights, this article serves as a valuable resource for innovating in the field of polymeric biomaterials.

Building Blocks of Polymers: A Deep Dive into Monomers and Core Polymerization Mechanisms

In both natural and engineered systems, the creation of complex macromolecular structures begins with fundamental molecular units known as monomers. Derived from the Greek words "mono" (meaning one) and "meros" (meaning part), a monomer represents an individual molecular network or discrete molecule that can chemically unite with analogous monomers to form polymers [1]. This chemical unification process, termed polymerization, enables two monomeric units to link together by sharing electrons, ultimately creating large macromolecular architectures with properties far exceeding those of their constituent parts [1]. The essential feature distinguishing monomers from other molecules is polyfunctionality—the capacity to form chemical bonds to at least two other monomer molecules, thereby enabling chain formation [2].

The significance of monomers extends across biological and synthetic domains. In living organisms, glucose monomers link via glycosidic bonds to form biopolymers such as cellulose and starch [1], while amino acids serve as monomeric building blocks for constructing the vast array of proteins essential for life [3]. In synthetic contexts, simple ethylene molecules (C₂H₄) polymerize to form polyethylene, one of the most widely produced plastics globally [3]. The structural characteristics and chemical functionalities of monomers directly determine the physical, mechanical, and chemical properties of the resulting polymers, making monomer selection and design a critical consideration in materials science, drug delivery development, and numerous industrial applications [1].

Monomer Fundamentals: Structure, Function, and Classification

Chemical Definition and Key Characteristics

Monomers are characterized by their specific chemical structure that enables polymerization. Bifunctional monomers, containing two reactive sites, can form only linear, chainlike polymers, while monomers of higher functionality yield cross-linked, network polymeric products [2]. This functionality arises from specific chemical features, including double bonds between atoms (as in ethylene, styrene, or butadiene) or rings of three to seven atoms (as in caprolactam) that can open and form new bonds [2]. Alternatively, monomers may contain two or more reactive atomic groupings, such as a compound that is both an alcohol and an acid, which can undergo repetitive ester formation to create polyesters [2].

The length-to-diameter (L/D) ratio represents a fundamental distinction between monomers and their resulting polymers. For example, while styrene monomer molecules might be conceptually represented by a dot, polystyrene with a degree of polymerization of 1000 would be represented by a line formed by connecting 1000 of these dots in a linear fashion [1]. This dramatic divergence in the L/D ratio creates the profound differences in physical and mechanical properties observed between small molecules and their polymeric counterparts [1].

Classification Schemes for Monomers

Monomers can be systematically categorized based on their chemical structure, functionality, and origin, as detailed in the table below.

Table 1: Classification of Monomers and Their Characteristics

| Classification Basis | Monomer Type | Key Characteristics | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Natural | Derived from biological sources; often biodegradable | Amino acids, glucose, nucleotides [3] [1] |

| Synthetic | Human-made; designed for specific properties | Ethylene, styrene, caprolactam [2] | |

| Functionality | Bifunctional | Two reactive sites; forms linear polymers | Ethylene glycol, terephthalic acid [2] |

| Polyfunctional | Three or more reactive sites; forms cross-linked networks | Glycerol, divinyl benzene [2] | |

| Polymerization Mechanism | Addition | Contains double bonds or rings; no byproduct | Ethylene, styrene, vinyl chloride [2] [4] |

| Condensation | Contains reactive functional groups; releases byproducts | Diacids, diamines, diols [2] | |

| Chemical Nature | Acidic | Can donate protons; forms hydrogen bonds | Methacrylic acid [1] |

| Basic | Can accept protons; forms ionic interactions | Vinylpyridine [1] |

Monomer-Polymer Relationship

The relationship between monomers and polymers represents a fundamental structural hierarchy in materials science. Monomers serve as the essential repeating units that define a polymer's primary structure, while their sequential arrangement dictates the higher-order properties and applications of the resulting macromolecule [3]. The degree of polymerization (DP), represented by 'n' in Equation 1, quantifies this relationship by calculating the number of repeat units in a polymer molecule [1]:

[ n = \frac{M}{M_0} ]

Where (M) is the molecular weight of the polymer and (M_0) is the molecular weight of the repeat unit [1].

When two or more dissimilar monomeric units combine, the resultant product is a copolymer, and the phenomenon is termed copolymerization [1]. Copolymers can be further classified based on the arrangement of monomeric units along the chain, with alternating, periodic, statistical, and block configurations representing the primary architectural variations [1]. For instance, block copolymers comprise homopolymer subunits connected via covalent bonds, with diblock and triblock copolymers representing important categories for advanced material applications [1].

Polymerization Mechanisms: From Monomers to Macromolecules

Chain-Growth (Addition) Polymerization

Chain-growth polymerization, also known as addition polymerization, involves monomers adding sequentially to a growing polymer chain that possesses an active center, such as a free radical, cation, anion, or coordination complex [5]. This mechanism is responsible for approximately 65% of all synthetic polymers produced globally [5] and is characterized by several distinctive features: rapid chain propagation (with individual chains completing in fractions of a second), high molecular weight polymers formed early in the reaction, and retention of all monomer atoms within the final polymer structure [5].

The process occurs through four distinct stages, each with specific timeframes and temperature parameters [5]:

Table 2: Stages of Chain-Growth Polymerization

| Stage | Timeframe | Key Processes | Temperature Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initiation | 0.1-1 second | Formation of active radical centers from catalysts or heat; monomers become reactive | 50-200°C (system dependent) [5] |

| Propagation | 0.1-10 seconds | Rapid addition of monomers to growing chains; chain extension | 50-200°C (system dependent) [5] |

| Chain Transfer | Variable | Radicals move between molecules; affects molecular weight distribution | 50-200°C (system dependent) [5] |

| Termination | Variable | Chains stop growing through combination or disproportionation | 50-200°C (system dependent) [5] |

The initiation stage begins with activating initiator molecules into reactive species, typically through thermal decomposition (requiring 125-145 kJ/mol for most peroxide initiators), photochemical activation using UV or visible light, or redox activation through electron transfer between reactants [5]. Once generated, these radicals attack monomer molecules, forming new reactive sites. For example, in ethylene polymerization: R• + CH₂=CH₂ → R-CH₂-CH₂• [5].

Propagation represents the core of chain-growth polymerization, where the radical at the chain end repeatedly adds monomer molecules in rapid succession. Each addition step transfers the radical site to the newly added monomer, maintaining continuous reactivity [5]. This process is exceptionally fast, with individual polymer chains potentially forming in less than 0.1 seconds, as each addition requires only 15-30 kJ/mol of activation energy [5]. The propagation rate constant (kₚ) varies significantly with monomer type: styrene at 60°C exhibits kₚ = 165 L/mol·s, methyl methacrylate at 60°C demonstrates kₚ = 515 L/mol·s, while vinyl acetate under the same conditions shows approximately 2300 L/mol·s [5].

Table 3: Thermodynamic Parameters in Chain-Growth Polymerization

| Parameter | Description | Representative Values |

|---|---|---|

| Activation Energy | Energy required for propagation step | 15-30 kJ/mol [5] |

| Heat of Reaction | Energy released per monomer added | ~83 kJ/mol (for ethylene) [5] |

| Ceiling Temperature (T꜀) | Temperature above which depolymerization occurs | α-Methylstyrene: 61°C; Styrene: ~310°C [5] |

During propagation, chains develop critical architectural features that define ultimate polymer properties. Branching occurs when an active radical abstracts hydrogen from an existing polymer chain through "backbiting" mechanisms. Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) contains 15-30 branches per 1000 carbon atoms, resulting in flexibility and lower crystallinity, while High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) exhibits minimal branching, creating stronger, more crystalline materials [5]. Tacticity, referring to the spatial arrangement of side groups, represents another critical structural parameter controlled during propagation [5].

Step-Growth (Condensation) Polymerization

Step-growth polymerization, alternatively termed condensation polymerization, proceeds through fundamentally different mechanisms than chain-growth pathways. In step-growth systems, monomers react through functional groups, often eliminating small molecules such as water, alcohol, or ammonia as byproducts [5]. This mechanism accounts for approximately 30% of synthetic polymer production [5] and exhibits distinct characteristics, including gradual molecular weight increase throughout the reaction (requiring over 98% conversion for high-performance polymers), byproduct elimination necessitating purification steps, and reactions possible between molecules of any size possessing reactive end groups [5].

The mathematical foundation of step-growth polymerization was established by Carothers' theoretical framework and his famous Carothers equation, which relates the extent of reaction to the average degree of polymerization [5]. Notable examples of condensation polymers include polyesters (PET), polyamides (Nylon 66), polyurethanes, epoxy resins, and polycarbonates, which find extensive applications in fibers, coatings, and engineering plastics [5]. A classic example is the formation of nylon-6,6, where hexamethylenediamine (containing two amine groups) condenses with adipic acid (containing two acid groups), with the elimination of water [2].

The timeframe for step-growth polymerization extends significantly longer than chain-growth processes, typically requiring several hours to achieve high molecular weights, with temperature ranges varying from 50°C to 200°C depending on the specific monomer system [5]. The process generally involves three primary stages: preparation (including monomer purification and precise measurement), polymerization (where functional groups react gradually over hours), and separation (where the polymer is isolated and purified) [5].

Advanced Analytical Techniques for Monomer and Polymer Characterization

NMR Spectroscopy for Microstructural Analysis

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy represents a powerful analytical tool for investigating polymer microstructures, including configurational distribution, chemical composition, and monomer sequences in copolymers [6]. Recent advances in multivariate analysis of NMR spectra have enabled precise prediction of chemical composition and monomer sequences, even for structurally similar acrylate copolymers where conventional analysis approaches face limitations due to signal overlap [6].

Experimental Protocol: Multivariate Analysis of NMR Spectra for Acrylate Copolymers

Sample Preparation: Methyl acrylate (MA) and ethyl acrylate (EA) comonomers are distilled under reduced pressure for purification. Nine copolymer and two homopolymer samples are prepared by radical (co)polymerization with varying monomer feed ratios. Reactions are quenched 10 minutes after initiation to limit conversion, ensuring representative primary structures relative to initial feed compositions [6].

NMR Measurement: ¹H and ¹³C NMR spectra are acquired using standard parameters. For ¹H NMR, typical conditions include 64-128 transients with a relaxation delay of 5-10 seconds. For ¹³C NMR, significantly more transients (1000-2000) are required due to lower natural abundance, with relaxation delays of 2-5 seconds [6].

Multivariate Analysis: Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression is applied to the NMR spectral data, using the spectra as explanatory variables and primary structures as objective variables. This statistical approach enables quantitative predictions of chemical composition and monomer sequences at the diad level, even when comonomers belong to the same structural category and exhibit severe spectral overlap [6].

Data Interpretation: The analysis successfully predicts MA composition from both ¹H and ¹³C NMR spectra, with ¹³C NMR providing superior accuracy due to its wider chemical shift range and enhanced structural sensitivity. Monomer sequences, particularly hetero-diad sequences, are more accurately predicted using ¹³C NMR spectra, while ¹H NMR yields only moderate accuracy for sequence analysis [6].

This methodology demonstrates that NMR spectroscopy combined with statistical multivariate analysis offers a robust approach for determining primary structures of acrylate copolymers without requiring individual signal assignments, providing critical structural information previously inaccessible through conventional integration-based approaches [6].

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) for Monomer Composition and Elution Analysis

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) provides complementary capabilities for characterizing monomer composition and quantifying residual monomer elution, particularly relevant for biomedical and dental applications where monomer leaching presents biocompatibility concerns [7].

Experimental Protocol: LC-MS Analysis of Dental Resins

Sample Preparation: Four commercial 3D-printed resin composites are selected, including two provisional resins (Temporary CB, Formlabs and NextDent C&B MFH) and two permanent 3D-printed resins (Saremco print CrownTec and VarseoSmile Crown plus). Unpolymerized resins undergo untargeted LC-MS for compositional screening, while polymerized specimens are immersed in artificial saliva (37°C, 72 hours) to simulate clinical conditions [7].

Untargeted Analysis: Initial screening detects 4,125 chemical features, which are refined to 39 high-confidence resin-derived compounds across the four materials. These compounds primarily include monomers and derivatives, with some photoinitiators and additives. Compound diversity varies significantly by material, with permanent Saremco and VarseoSmile showing the greatest variety [7].

Targeted Quantitative Analysis: Following immersion, targeted quantitative LC-MS is performed to quantify eluted residual monomers using certified standards calibration curves for HEMA, TEGDMA, UDMA, and Bis-EMA. This approach provides precise measurement of monomer release profiles under simulated clinical conditions [7].

Results and Interpretation: The analysis reveals substantial variability in both composition and monomer elution profiles among commercial 3D-printed dental resins. Bis-EMA predominates in Temporary CB, Saremco, and VarseoSmile, while UDMA is most abundant in NextDent, Saremco, and VarseoSmile. Quantitative assessment shows that Temporary CB and VarseoSmile release the highest levels of Bis-EMA, NextDent demonstrates greatest elution of HEMA and UDMA, and VarseoSmile exhibits the highest TEGDMA release. Saremco generally shows the lowest concentrations of all monitored monomers [7].

These findings underscore the material-specific nature of chemical composition and monomer elution in 3D-printed dental resins, highlighting the need for material-specific biocompatibility testing to ensure long-term clinical safety [7].

Monomer-Functionalized Materials for Advanced Applications

Functionalized Monoliths for Selective Sample Preparation

Monolithic materials functionalized with specific monomers have emerged as powerful tools for selective sample preparation in analytical chemistry. Monoliths with large macropores serve as ideal substrates for solid-phase extraction (SPE) coupled with liquid chromatography (LC) due to their low back pressure and versatility across various formats [8]. The functionalization of these monoliths with biomolecules or nanoparticles significantly enhances their selectivity and sensitivity for target analytes [8].

Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) represent a particularly advanced application of functional monomers in analytical science. Their synthesis is based on the complexation of a template molecule with functional monomers via non-covalent interactions, followed by polymerization of these monomers around the template with the addition of a cross-linking agent and initiator [8]. After polymerization, template removal creates cavities complementary to the template molecule in terms of size, shape, and position of functional groups [8]. The selection of reagents for MIP synthesis must be carefully considered to create cavities highly specific to the target molecule [8].

These functionalized monoliths can be synthesized in situ directly within capillaries or microchip channels, with polymerization conditions carefully controlled to achieve sufficient permeability for solution percolation while maintaining specific molecular recognition capabilities [8]. Applications include monitoring cocaine in human plasma, where injecting only 100 nL of diluted plasma enables detection limits achievable with simple UV detectors coupled with nanoLC, while maintaining minimal solvent consumption [8].

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Monomer-Functionalized Materials

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Monomers | Methacrylic acid, Vinylpyridine [1] | Provide points of electronic recognition for template rebinding in MIPs |

| Cross-linking Agents | Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate, Divinyl benzene [8] | Create rigid polymer network around template molecules |

| Initiators | Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN), Benzoyl peroxide [5] [6] | Generate free radicals to initiate polymerization |

| Template Molecules | Drug compounds, Biomarkers [8] | Create specific recognition cavities during MIP synthesis |

| Porogenic Solvents | Toluene, Cyclohexanol [8] | Control porous structure of resulting monoliths |

Biomedical Polymers for Therapeutic Applications

Monomers and their resulting polymers play increasingly critical roles in biomedical applications, with custom polymer synthesis evolving rapidly to meet healthcare demands. Smart polymers that respond to environmental stimuli such as temperature, pH, or light are gaining significant momentum in healthcare applications [9]. These advanced materials enable controlled drug release based on physiological triggers, create scaffolds that mimic biological environments for tissue engineering, and form the basis for flexible polymers integrated with sensors for real-time health monitoring [9].

The integration of nanotechnology with smart polymers is driving advances in personalized medicine, making treatments more effective and accessible [9]. Hydrogel-based polymers that swell or shrink to release drugs on-demand represent particularly innovative examples, significantly enhancing patient outcomes through precise temporal and spatial control over therapeutic delivery [9].

Biodegradable and bio-based polymers represent another major trend, with sustainability considerations driving adoption of materials that reduce environmental impact while offering comparable or superior properties to conventional polymers [9]. Key drivers include increasingly stringent environmental regulations demanding reduced reliance on fossil fuels and improved waste management, coupled with growing consumer preference for sustainable products [9]. Notable examples include polylactic acid (PLA) for packaging and medical implants, and polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) for biodegradable films and coatings [9].

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of monomer science and polymer synthesis continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping future research directions and applications. Artificial intelligence-driven design represents a particularly transformative trend, with machine learning algorithms increasingly employed to predict and optimize polymer properties, significantly accelerating materials discovery and development [9]. These data-driven models are revolutionizing custom polymer development, optimizing formulations, and reshaping R&D workflows across academic and industrial settings [9].

Advanced manufacturing techniques including additive manufacturing (3D printing) and continuous flow synthesis are enabling the production of polymers with unprecedented precision and efficiency [9]. Custom polymers specifically designed for additive processes facilitate intricate designs and rapid prototyping, while continuous flow methods provide scalable pathways to produce high-purity polymers with minimal batch-to-batch variation [9].

Sustainable polymer recycling technologies are addressing growing environmental concerns associated with polymer disposal. Innovative approaches including chemical recycling methods that break down polymers into reusable monomers for high-value applications, and enzyme-based recycling systems that decompose plastics into reusable components, represent promising directions for achieving circular economy objectives in polymer science [9].

The expanding applications of functional polymers for electronics continue to drive innovations, with the electronics industry increasingly adopting custom polymers to meet demands for lightweight, flexible, and high-performance materials [9]. Conductive polymers for flexible displays and sensors, dielectric materials for energy storage, and thermally stable polymers for high-performance circuits represent active research frontiers with significant technological implications [9].

As these trends converge, the future of monomer science and polymer synthesis appears positioned to address increasingly complex global challenges while unlocking new opportunities across healthcare, energy, electronics, and sustainability domains. The continued refinement of analytical techniques for characterizing monomer composition and polymer microstructure will remain essential for advancing these developments and ensuring the rational design of next-generation polymeric materials with tailored properties and functions.

In monomer and polymerization process research, the fundamental mechanism by which monomers assemble into macromolecules dictates the strategy for synthesizing polymers with tailored properties. The two primary pathways, step-growth polymerization and chain-growth polymerization, are distinguished by their fundamental reaction mechanisms, kinetics, and the resulting polymer architectures [10]. For researchers and scientists in drug development and material science, selecting the appropriate pathway is critical for controlling molecular weight, dispersity, and ultimate material performance [11]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical comparison of these mechanisms, supported by quantitative data, experimental protocols, and visualization tools to guide research and development efforts.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Kinetic Profiles

The processes of step-growth and chain-growth polymerization are fundamentally distinct in their mechanisms and kinetic behavior [12].

Step-Growth Polymerization Mechanism

In step-growth polymerization (SGP), bi-functional or multi-functional monomers react to form dimers, trimers, and longer oligomers in a non-chain reaction process [13] [14]. Any two molecular species with complementary reactive groups can react, and the polymer molecular weight increases gradually throughout the reaction [12]. High molecular weight polymers are only achieved at high conversion rates (typically >98%) of the functional groups [14]. Common examples include polyesters, polyamides (e.g., nylons), and polyurethanes, often formed through reactions like nucleophilic acyl substitution [13].

Chain-Growth Polymerization Mechanism

Chain-growth polymerization (CGP) is a chain reaction characterized by three core steps: initiation, propagation, and termination [15] [16]. An active center—a free radical, cation, anion, or transition metal complex—is generated during initiation. This active center adds monomer units one at a time to a rapidly growing chain during propagation [16] [17]. The reaction mixture thus consists mainly of unreacted monomer and high-molecular-weight polymer, with only a minimal concentration of growing chains [15] [17]. High molecular weight is achieved rapidly, even at low monomer conversion [10].

Table 1: Core Mechanistic Differences Between Step-Growth and Chain-Growth Polymerization

| Characteristic | Step-Growth Polymerization | Chain-Growth Polymerization |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Profile | Growth occurs throughout the matrix between any reactive species [14] | Growth occurs by addition of monomer only at the active chain end(s) [14] [17] |

| Monomer Consumption | Rapid loss of monomer early in the reaction [14] | Monomer concentration decreases steadily over time; some remains at long reaction times [14] [17] |

| Reaction Steps | Similar steps repeated throughout the process [14] | Distinct stages: initiation, propagation, and termination [14] [16] |

| Molecular Weight Build-Up | Molecular weight increases slowly at low conversion; high extents of reaction are required for long chains [12] [14] | Molar mass of the backbone chain increases rapidly at an early stage and remains approximately the same throughout [14] |

| Active Chain Ends | Chain ends remain active throughout the reaction (no termination step) [14] | Chains are not active after termination [14] |

| Initiator Requirement | No initiator is necessary [14] | An initiator or catalyst is required to start the reaction [14] [17] |

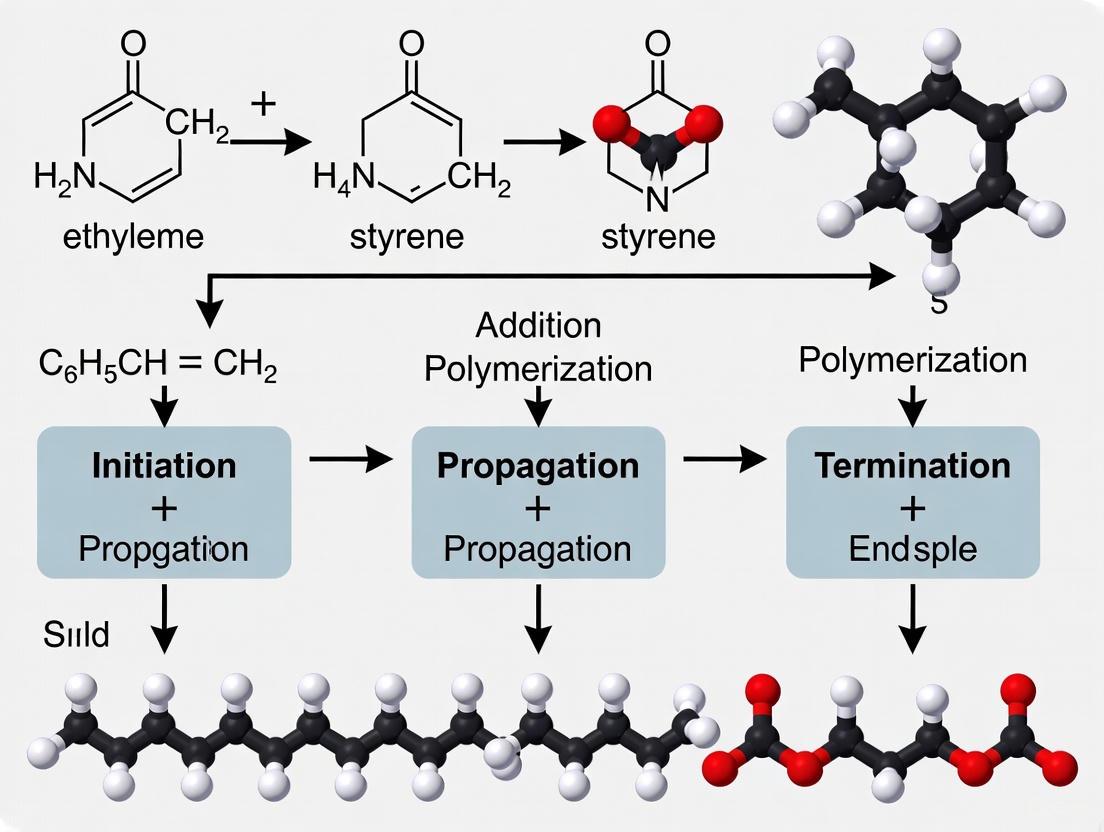

Diagram 1: Polymerization mechanisms comparison.

Quantitative Comparison and Kinetics

The kinetic profiles of step-growth and chain-growth polymerizations are fundamentally different, which has direct implications for reaction monitoring and control in research and industrial settings [10].

Step-Growth Kinetics

The kinetics can be modeled using a polyesterification reaction. For an externally catalyzed system, the rate of polymerization is first order in each functional group [14]. The number-average degree of polymerization ((Xn)) is given by: [ Xn = \frac{1}{1-p} ] where (p) is the extent of reaction (fraction of functional groups that have reacted). This shows that (Xn) increases proportionally with time, and a high molecular weight (e.g., (Xn = 100)) requires a very high conversion ((p = 0.99)) [14].

Chain-Growth Kinetics

In contrast, chain-growth polymerization exhibits a rapid increase in molecular weight early in the reaction, with the molecular weight remaining relatively constant throughout the majority of the process [15] [14]. The rate of polymerization is proportional to both the concentration of monomer and the concentration of active centers [10].

Table 2: Kinetic and Molecular Weight Characteristics

| Parameter | Step-Growth Polymerization | Chain-Growth Polymerization |

|---|---|---|

| Kinetic Order | Rate depends on concentration of functional groups [10] | Rate proportional to monomer and initiator concentration [10] |

| Molecular Weight vs. Conversion | Increases slowly at low conversion, sharply near completion [12] [14] | High molecular weight achieved immediately at low conversion [14] |

| Typical Dispersity (Đ) | Đ = 1 + p (theoretically 2 at full conversion) [11] | Varies by mechanism; often broad, but can be controlled (e.g., Đ ≤ 1.5 in living polymerization) [16] [11] |

| Key Mathematical Relationship | (X_n = \frac{1}{1-p}) (Carothers Equation) [14] | Molecular weight controlled by [M]/[I] ratio in living systems [16] |

Diagram 2: Kinetic profiles of polymerization pathways.

Representative Polymer Classes and Applications

The choice of polymerization mechanism directly influences the properties and applications of the resulting material.

Step-Growth Polymers

- Polyamides (Nylon): Synthesized from diamines and dicarboxylic acids (e.g., Nylon-6,6 from 1,6-hexanediamine and adipic acid). They possess high strength, good elasticity, abrasion resistance, and toughness, finding use in fibers, ropes, gears, and bearings [13] [14].

- Polyesters (PET): Formed from dicarboxylic acids and diols (e.g., Polyethylene terephthalate from terephthalic acid and ethylene glycol). They exhibit high Tg and Tm, good mechanical properties, and are used in fibers, films, and beverage bottles [13] [12].

- Polycarbonates: Known for transparency, high impact strength, and good thermal stability. Applications include eyewear lenses, automotive components, and medical devices [14].

Chain-Growth Polymers

- Polyolefins (PE, PP): Produced via coordination catalysis, these are among the most widely produced polymers. Used in packaging, containers, and automotive parts due to their low cost, toughness, and ease of processing [10] [16].

- Polyvinyls (PVC, PS): Synthesized via free-radical polymerization. Polystyrene is used in disposable utensils and insulation, while PVC is used in piping, cables, and siding [16].

- Acrylics (PMMA): Known for optical clarity and weather resistance, used as a glass alternative and in medical devices [16].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of Nylon-6,6 via Step-Growth Polymerization

Principle: This two-stage synthesis involves the formation of a nylon salt from 1,6-hexanediamine and adipic acid, followed by melt polycondensation at elevated temperature to form the polyamide [13] [12].

Procedure:

- Nylon Salt Preparation: Dissolve equimolar amounts of 1,6-hexanediamine (0.1 mol) and adipic acid (0.1 mol) in a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of methanol and water. The salt precipitates upon mixing. Isolate the salt by filtration and recrystallize from methanol.

- Polymerization: Place the dry nylon salt (10 g) in a polymerization tube equipped with an inlet for nitrogen and a vacuum outlet. Flush the tube with nitrogen.

- Heat the tube to 210–220 °C under a slow nitrogen stream for 1–2 hours to initiate the reaction.

- Gradually increase the temperature to 270–280 °C. Slowly apply a vacuum (e.g., < 1 mmHg) to remove the condensed water vapor and drive the equilibrium towards polymer formation.

- Maintain these conditions for 2–3 hours. The completion of the reaction can be monitored by the increase in melt viscosity and the cessation of water evolution.

- After cooling under nitrogen, the solid polymer can be isolated and, if necessary, processed by remelting and extrusion.

Key Considerations: Strict stoichiometric balance between the diamine and diacid is crucial for achieving high molecular weight. The removal of the condensate (water) is essential to shift the equilibrium towards the polymer [12].

Protocol 2: Free-Radical Polymerization of Styrene

Principle: This chain-growth polymerization uses a thermal initiator to generate free radicals that add to styrene monomers, propagating a chain reaction until termination occurs [15] [16].

Procedure:

- Purification: Purify styrene monomer by washing with an aqueous NaOH solution to remove inhibitor, followed by drying over anhydrous calcium chloride. Distill under reduced pressure before use.

- Reaction Setup: In a Schlenk flask, add purified styrene (10 mL, 0.087 mol) and a magnetic stir bar. Degas the solution by performing several freeze-pump-thaw cycles.

- Initiation: Under a positive pressure of inert gas (N₂ or Ar), add a free-radical initiator such as 2,2'-Azobis(2-methylpropionitrile) (AIBN) (10 mg, 0.061 mmol). Seal the flask.

- Propagation & Termination: Place the flask in an oil bath pre-heated to 60–70 °C with constant stirring. The polymerization will proceed for 6–12 hours. The increase in viscosity indicates polymer formation.

- Isolation: After cooling, dissolve the viscous mixture or solid polymer in a minimal amount of a suitable solvent like toluene. Precipitate the polymer by slowly pouring the solution into a large excess of vigorously stirred methanol. Filter the precipitated polystyrene and dry under vacuum until constant weight.

Key Considerations: The concentration of the initiator controls the number of growing chains and thus the average molecular weight. The reaction must be conducted under oxygen-free conditions, as oxygen is an effective radical scavenger that can inhibit the reaction [15].

Advanced Research: Controlling Dispersity in Step-Growth Polymers

A significant challenge in step-growth polymerization is the inherent lack of control over molecular weight distribution (dispersity, Đ), which typically approaches 2.0 at high conversion according to the Flory model (Đ = 1 + p) [11]. Recent advanced research has introduced new methods to overcome this limitation.

Asymmetric Dynamic Bond-mediated Polymerization (ADBP): This novel approach, reported in 2025, uses asymmetric and reversibly deactivated AA'-type dielectrophiles (e.g., isophorone diisocyanate, IPDI) reacting with B₂-type dinucleophiles (e.g., a diol) [11]. The reversibly deactivated A' group (using diisopropylamine, DIPA) creates a preferential reaction pathway.

Mechanism: The polymerization proceeds in two stages. First, an oligomerization stage (conversion, p ≤ 0.6) primarily forms well-defined dimers and trimers, keeping Đ low (≤1.2). This is followed by a polymerization stage (p ≥ 0.6) where these oligomers react, resulting in final polymers with Đ ≈ 1.5, significantly narrower than traditional SGP [11].

Significance for Researchers: This method provides a route to synthesize step-growth polymers like polyurethanes with controlled dispersities (Đ ≤ 1.5), leading to improved nanoscale order, enhanced microphase separation in block copolymers, and superior mechanical properties [11]. It represents a major step towards achieving the level of control in step-growth polymerization that has long been available in controlled chain-growth techniques.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Polymerization Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Diisopropylamine (DIPA) | Reversible deactivator for isocyanates in ADBP for controlled step-growth [11] | Enables asymmetry in monomer reactivity, crucial for achieving narrow dispersity. |

| AIBN (Azobisisobutyronitrile) | Thermal free-radical initiator for chain-growth polymerizations [15] [17] | Half-life is temperature-dependent; concentration directly influences molecular weight. |

| Dibutyltin Dilaurate (DBTDL) | Common catalyst for polyurethane formation and esterification reactions [11] | Highly effective Lewis acid catalyst; amounts as low as 0.1 mol% are often sufficient. |

| Isophorone Diisocyanate (IPDI) | Asymmetric diisocyanate monomer for polyurethane synthesis [11] | The asymmetry of the -NCO groups is exploited in ADBP to control the reaction pathway. |

| Nylon Salt | Pre-formed, stoichiometric 1:1 salt of diamine and diacid [13] [12] | Ensures exact monomer balance for achieving high molecular weight in polyamides. |

Polymerization, the process of linking small molecules (monomers) into large chains (polymers), is fundamental to creating a vast array of synthetic materials. For chain-growth polymerization, this process is governed by three essential steps: initiation, propagation, and termination. Together, this trilogy of reactions determines the molecular weight, architecture, and ultimate properties of the resulting polymer. For researchers in materials science and drug development, precise control over these steps is paramount for designing polymers with specific functionalities, such as those used in drug delivery systems, biomedical devices, or advanced plastics [18] [19]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these core mechanisms, with a focus on modern controlled radical polymerization techniques that have revolutionized polymer synthesis.

The Fundamental Mechanism: A Detailed Analysis

The journey of creating a polymer chain begins with the generation of an active center and culminates in the cessation of its growth. The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and key intermediates in this fundamental process.

Initiation

The initiation step generates the active species that will propagate the polymer chain. In free-radical polymerization, this typically involves a two-part process. First, a thermolabile initiator, such as Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN), decomposes upon heating to form two primary radical fragments (I•) [20] [21] [22]. Second, these primary radicals react with a monomer molecule (e.g., a methacrylate or styrene derivative), adding across its carbon-carbon double bond. This reaction forms the initial propagating radical (P1•), which is the nucleus for the growing polymer chain [22]. The efficiency of initiation depends on the initiator's decomposition rate and the reactivity of the resulting radicals toward the monomer.

Propagation

Propagation is the chain-elongation stage where the polymer's molecular weight rapidly increases. The active propagating radical (Pn•) at the end of a growing chain successively adds to the double bonds of many monomer molecules [19] [22]. Each addition regenerates the active site at the chain end, allowing the process to continue. This step is extremely fast and is responsible for the bulk of the polymer's mass. The rate of propagation is governed by the concentration of monomer and active chains, as well as the intrinsic reactivity of the monomer-radical pair.

Termination

Termination is the bimolecular reaction that deactivates the propagating radicals, ending chain growth. The two most common pathways are combination and disproportionation [22]. In combination, two growing chains (Pn• and Pm•) couple to form a single dead polymer chain (Pn+m). In disproportionation, a hydrogen atom is transferred from one chain to another, resulting in two dead chains: one with a saturated end-group (Pn-H) and one with an unsaturated end-group (Pm=) [19]. Because termination is a diffusion-controlled process between two highly reactive species, it is often the most difficult step to control in conventional free-radical polymerization.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of the Fundamental Polymerization Steps

| Step | Primary Function | Key Reactants | Products Formed | Kinetic Order |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initiation | Generate active centers | Initiator, Monomer | Initial Propagating Radical (P1•) |

First-order in initiator |

| Propagation | Chain elongation | Propagating Radical (Pn•), Monomer |

Longer Propagating Radical (Pn+1•) |

First-order in monomer and active chains |

| Termination | Cease chain growth | Two Propagating Radicals (Pn• and Pm•) |

Dead Polymer (Pn+m or Pn-H + Pm=) |

Second-order in active chains |

Advanced Control: Reversible Deactivation Radical Polymerization (RDRP)

Traditional free-radical polymerization provides limited control over molecular weight and architecture due to irreversible termination. The advent of Reversible Deactivation Radical Polymerization (RDRP) techniques, such as Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain Transfer (RAFT), has enabled unprecedented precision [21] [22] [23].

The RAFT process introduces a critical equilibrium between active and dormant chain ends, mediated by a chain transfer agent (CTA). The following workflow details the mechanism of this controlled process.

The RAFT Mechanism

The mechanism of RAFT polymerization introduces additional equilibria to the classic trilogy, enabling control [21] [22] [23]:

- Pre-equilibrium: A propagating radical (

Pn•) reacts with the RAFT agent (a thiocarbonylthio compound) in a reversible addition-fragmentation cycle. The radical adds to the C=S bond of the RAFT agent, forming an intermediate radical. This intermediate fragments, yielding a new radical (R•) and a dormant polymeric chain ending with a thiocarbonylthio group (S=C(Z)S-Pn). - Re-initiation: The expelled

R•radical reacts with monomer to start a new chain, forming a new propagating radical (Pm•). - Main Equilibrium: The core of RAFT control is the rapid equilibrium between all active propagating chains (

Pn•,Pm•) and all dormant chains. This reversible exchange allows all chains to grow at a similar rate, resulting in polymers with narrow molecular weight distributions (low dispersity, Đ). The active species spend most of their time in the dormant state, minimizing irreversible termination events.

Novel Initiation Methods in RAFT

While thermal initiators like AIBN are common, recent advances have introduced sophisticated initiation methods that offer superior spatiotemporal control [21] [24]:

- Photoiniferter (PI)-RAFT: In this approach, the CTA itself acts as the initiator upon irradiation with light. Direct photolysis of the CTA's C–S bond generates the radical species needed to initiate and control the polymerization [24]. A key advantage is the ability to precisely start and stop the reaction by switching the light on and off.

- Photoinduced Electron/Energy Transfer (PET)-RAFT: This method uses a photoredox catalyst under light irradiation to mediate the activation of the RAFT agent via an electron or energy transfer process, rather than direct bond homolysis [21].

Table 2: Comparison of RAFT Polymerization Initiation Methods

| Method | Radical Source | Key Advantage | Typical Conditions | Spatiotemporal Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Initiation | Thermal decomposition of initiators (e.g., AIBN) [21] [22] | Simplicity, wide applicability | Elevated temperature (e.g., 60-80°C) | No |

| Photoiniferter (PI)-RAFT | Direct photolysis of the RAFT agent [24] | Avoids separate initiator, highly "living" nature | Room temperature, Blue/Green light | Yes, via light switching |

| PET-RAFT | Photoredox catalyst under light [21] | Tolerance to oxygen, wider wavelength range | Room temperature, Visible light | Yes, via light switching |

Experimental Protocols and Reagent Solutions

Detailed Methodology: Photoiniferter (PI)-RAFT Polymerization of Poly(PEGMA)

This protocol describes the synthesis of poly(poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate) (P(PEGMA)), a biocompatible bottle-brush polymer, using PI-RAFT, adapted from recent research [24].

Principle: The trithiocarbonate Chain Transfer Agent (CTA) is directly activated by blue light, acting as a photoiniferter to control the polymerization without a separate chemical initiator.

Materials and Equipment:

- Monomer: PEGMA (Mn = 300 g/mol).

- RAFT Agent: A trithiocarbonate-type CTA (e.g., 2-(((Butylthio)carbonothioyl)thio)propanoic acid).

- Solvent: Anisole, DMSO, or other suitable solvents.

- Reactor: Schlenk tube or vial with a magnetic stir bar.

- Light Source: Blue LED array (λmax = 470 nm, intensity ~1.6 mW cm⁻²).

- Inert Atmosphere: Nitrogen (N₂) gas supply.

- Purification: Dialysis membrane (e.g., 3.5 kDa MWCO).

Procedure:

- Reaction Mixture Preparation: In a vial, dissolve PEGMA and the CTA in the chosen solvent (e.g., 50% v/v monomer concentration) to achieve a molar ratio of

[M]₀ : [CTA] = 100 : 1. Mix thoroughly until a homogeneous solution is obtained. - Degassing: Transfer the solution to a Schlenk tube equipped with a stir bar. Sparge the solution with N₂ gas for 45-60 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen, which inhibits radical polymerization.

- Polymerization: Place the degassed reaction vessel under the blue LED light source at a controlled temperature (e.g., 22°C) with continuous stirring. Initiate the reaction by turning on the light.

- Kinetic Monitoring: At predetermined time intervals (e.g., 0.5, 1, 2, 3 hours), withdraw small aliquots (~0.1 mL) from the reaction mixture under N₂.

- Conversion Analysis: Determine monomer conversion for each aliquot using ¹H NMR spectroscopy in CDCl₃. Compare the integral of the vinyl methylene protons of the remaining monomer (~4.23 ppm) with the corresponding signal of the polymer (~4.01 ppm) [24].

- Polymer Isolation: After the target conversion (e.g., 50%) is reached, stop the reaction by turning off the light and exposing the mixture to air. Dilute the final mixture and dialyze it against deionized water for 48 hours, changing the water regularly. Recover the pure polymer by lyophilization.

Key Considerations: The choice of solvent significantly impacts the polymerization kinetics and control. Anisole has been shown to maintain low dispersity (Đ ~1.30) even at elevated temperatures (40°C) for this system [24]. The wavelength and intensity of the light must be optimized for the specific CTA used.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Controlled Polymerization

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Controlled Radical Polymerization Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Initiators | AIBN, ACVA, V-60 [20] [23] | Thermal source of primary radicals to start the polymerization chain reaction. |

| RAFT Agents (CTAs) | Trithiocarbonates, Dithiobenzoates, Dithiocarbamates, Xanthates [21] [22] [23] | Core agent for control; mediates the equilibrium between active and dormant chains to dictate molecular weight and dispersity. |

| Functional Monomers | Methyl methacrylate (MMA), n-Butyl Acrylate (nBA), Styrene, P(PEGMA) [20] [24] [23] | Building blocks of the polymer chain. Functional groups (e.g., phosphate, PEG) impart final material properties. |

| Solvents | Anisole, 1,4-Dioxane, DMSO, DMF [24] | Medium for reaction. Polarity and properties can influence reaction rate, control, and polymer solubility. |

| Specialized Additives | Photoredox Catalysts (for PET-RAFT) [21] | Enable alternative activation pathways (e.g., with light) for greater control and milder reaction conditions. |

Quantitative Data and Performance Metrics

The success of controlled polymerization protocols is quantified by key metrics such as molecular weight control, dispersity (Đ = Mw/Mn), and conversion.

Table 4: Performance Metrics from Representative RAFT Polymerization Experiments

| Polymer System | Conditions | Final Mn (g/mol) | Dispersity (Đ) | Conversion | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(n-butyl acrylate) [23] | Bulk, 70°C, Thermal RAFT | 25,900 | 1.09 | Not Specified | Linear increase in Mn with conversion, indicative of excellent control. |

| P(PEGMA) in Anisole [24] | 50% v/v, 40°C, PI-RAFT | Not Specified | 1.30 | Target: 50% | Anisole identified as a superior solvent for maintaining low Đ at higher temperatures. |

| P(PEGMA) in DMSO [24] | 50% v/v, 22°C, PI-RAFT | Not Specified | >1.30 | Target: 50% | Demonstrated the significant effect of solvent choice on the livingness of the polymerization. |

The trilogy of initiation, propagation, and termination forms the foundational framework of chain-growth polymerization. Mastery of these steps, particularly through advanced techniques like RAFT, allows researchers to transcend the limitations of traditional synthesis. The ability to precisely control molecular weight, architecture, and end-group functionality is no longer a theoretical goal but a practical reality. This empowers scientists, especially in drug development and biomaterials, to engineer bespoke polymeric materials with tailored properties for applications ranging from targeted therapeutics to functional hydrogels. As research continues to refine these processes with novel activation methods and deeper mechanistic understanding, the precision and scope of polymer science will continue to expand.

Monomers, derived from the Greek words mono (one) and meros (part), are fundamental molecular units that serve as the foundation for constructing larger polymer chains or three-dimensional networks through polymerization [25]. These building blocks occupy a central role in both biological systems and industrial processes, creating a diverse landscape of materials with tailored properties. The distinction between natural and synthetic monomers represents more than just origin—it encompasses differences in molecular complexity, functionality, and application potential that are critical for researchers exploring polymerization processes.

Natural monomers such as amino acids, nucleotides, and monosaccharides have evolved over millennia to form the complex biopolymers essential to life, including proteins, nucleic acids, and polysaccharides [26] [25]. In contrast, synthetic monomers are engineered through chemical processes to create materials with specific characteristics not readily available in nature. The growing field of pseudo-natural products (PNPs) further blurs these boundaries by combining natural product fragments in novel arrangements not accessible through biosynthesis pathways [27], creating exciting opportunities for drug discovery and material science.

This technical guide examines the fundamental properties, experimental methodologies, and research applications of both natural and synthetic monomers, with particular emphasis on their roles in pharmaceutical development and biomedical innovation. By providing a comprehensive comparison and detailed experimental protocols, this resource aims to equip researchers with the knowledge necessary to select appropriate monomers for specific applications within their polymerization process research.

Classification and Fundamental Properties

Natural Monomers

Natural monomers are organic molecules found in biological systems that serve as the constitutional units for essential biopolymers [26]. These building blocks share common characteristics of biological origin, specific functionality, and the ability to form complex structures through enzymatic processes.

Table 1: Fundamental Natural Monomers and Their Polymer Forms

| Monomer Class | Specific Examples | Resulting Polymer | Key Functional Groups | Primary Biological Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acids | Glycine, Glutamine, Valine, Arginine, Cysteine [26] | Proteins (via peptide bonds) [26] | Amino group (-NH₂), Carboxyl group (-COOH) [26] | Catalysis, structure, movement |

| Nucleotides | Adenine, Guanine, Cytosine, Thymine (DNA); Adenine, Guanine, Cytosine, Uracil (RNA) [25] | DNA/RNA (via phosphodiester bonds) [26] [25] | Nitrogenous base, Pentose sugar, Phosphate group [26] | Genetic information storage and transfer |

| Monosaccharides | Glucose, Fructose, Galactose [26] | Cellulose, Starch, Glycogen (via glycosidic bonds) [26] [25] | Hydroxyl groups (-OH), Carbonyl group (-C=O) | Energy storage, structural support |

| Isoprene | 2-methyl-1,3-butadiene [26] | Natural rubber (cis-1,4-polyisoprene) [26] [25] | Conjugated diene | Elasticity, specialized plant functions |

The twenty proteinogenic amino acids represent a key class of natural monomers characterized by the presence of both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups, allowing them to form peptide bonds through condensation reactions [26]. These monomers contain variable side chains that dictate the higher-order structure and function of the resulting proteins. Nucleotides, consisting of a nitrogenous base (purine or pyrimidine), pentose sugar, and phosphate group, serve as monomers for DNA and RNA through phosphodiester linkages [26]. The most abundant natural monomer is glucose, which polymerizes via glycosidic bonds to form cellulose, starch, and glycogen [25]. Isoprene (2-methyl-1,3-butadiene) represents another significant natural monomer that forms cis-1,4-polyisoprene, the primary component of natural rubber [26] [25].

Synthetic Monomers

Synthetic monomers are human-made compounds deliberately designed and produced for specific polymerization processes and applications. These monomers typically feature simpler chemical structures than their natural counterparts and are derived predominantly from petrochemical sources.

Table 2: Common Synthetic Monomers and Their Industrial Applications

| Monomer | Chemical Structure | Polymer Form | Polymerization Mechanism | Primary Industrial Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethylene | H₂C=CH₂ [28] [25] | Polyethylene [28] [25] | Addition polymerization [28] | Plastic bags, bottles, containers [28] |

| Vinyl Chloride | H₂C=CHCl [28] | Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) [28] | Addition polymerization [28] | Plumbing pipes, electrical insulation [28] |

| Tetrafluoroethylene | F₂C=CF₂ [26] | Polytetrafluoroethylene (Teflon) [26] | Addition polymerization | Non-stick coatings, chemical-resistant materials |

| Caprolactam | (CH₂)₅C(O)NH [26] | Nylon-6 [26] | Ring-opening polymerization [26] | Textile fibers, engineering plastics |

| Ethyl Methacrylate | H₂C=C(CH₃)COOCH₂CH₃ [25] | Poly(methyl methacrylate) variants | Addition polymerization | Acrylic plastics, artificial nails [25] |

Ethylene represents the simplest and most widely used synthetic monomer, forming polyethylene through addition polymerization [28] [25]. This process involves free radical initiation that opens the double carbon bond, allowing chain propagation through successive monomer additions [28]. Modified ethylene derivatives including vinyl chloride and tetrafluoroethylene expand the property range of resulting polymers [25]. Specialty monomers represent an advanced category of synthetic monomers engineered with specific functional groups to impart tailored properties such as enhanced durability, flexibility, or chemical resistance to the resulting polymers [29].

Comparative Analysis: Structural and Functional Relationships

The fundamental distinction between natural and synthetic monomers lies in their structural complexity and functional diversity. Natural monomers have evolved to perform specific biological functions through precise molecular recognition, while synthetic monomers are designed primarily for processability and material properties.

Molecular Complexity and Side Groups

Natural monomers exhibit considerable structural complexity with diverse functional groups that enable sophisticated molecular interactions. Amino acids feature side chains ranging from simple hydrogen atoms (glycine) to complex aromatic and heterocyclic systems (tryptophan, histidine). This diversity allows proteins to fold into precise three-dimensional structures with specific binding pockets and catalytic capabilities. Similarly, nucleotides contain heterocyclic base pairs capable of specific hydrogen bonding (Watson-Crick base pairing) that enables precise genetic coding [30].

In contrast, most industrial synthetic monomers prioritize structural simplicity and symmetry to facilitate efficient polymerization and create materials with uniform properties. Ethylene, propylene, and vinyl monomers feature straightforward hydrocarbon structures with minimal functionalization, allowing for high molecular weight polymers with regular chain structures. This fundamental difference in complexity directly impacts the functionality and applications of the resulting polymers.

Polymerization Mechanisms and Byproducts

Natural monomers typically undergo enzymatic polymerization processes that are highly regulated and efficient under mild physiological conditions. Amino acids polymerize through ribosome-catalyzed reactions at ambient temperatures and neutral pH, with water as the only byproduct [26]. Nucleotide polymerization involves similarly precise enzymatic control during DNA replication and transcription.

Synthetic polymerization employs more energetically demanding processes, often requiring high temperatures, pressures, and catalyst systems. Addition polymerization of monomers like ethylene involves free radical initiation that breaks double bonds to form active chain carriers [28]. Condensation polymerization, used for producing nylons and polyesters, generates small molecule byproducts such as water or methanol that must be removed to drive the reaction to completion [26].

Experimental Approaches and Research Methodologies

Analyzing DNA Polymerase Interactions with Synthetic Nucleotides

The study of how DNA polymerases recognize and utilize synthetic nucleotides provides critical insights for multiple research domains, including mutagenesis studies, cancer research, and the development of novel therapeutics [30].

Experimental Protocol:

- Template Design: Synthesize DNA oligonucleotides containing specific synthetic nucleotide analogs at defined positions using solid-phase synthesis [30]. Common modifications include abasic sites (tetrahydrofuran derivatives), base analogs with altered hydrogen bonding patterns, or fluorescent nucleotides for FRET studies [30].

Polymerase Assay: Incubate the modified template with the DNA polymerase of interest (e.g., Klenow fragment, Taq polymerase, or Y-family translesion polymerases) in appropriate reaction buffer containing Mg²⁺ ions and natural or modified nucleoside triphosphates [30].

Product Analysis: Separate extension products using polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis to determine insertion efficiency opposite synthetic nucleotides and subsequent extension capability. Alternatively, use mass spectrometry for precise characterization of incorporated nucleotides [30].

Kinetic Analysis: Employ steady-state or pre-steady-state kinetic measurements to determine catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) for nucleotide incorporation opposite natural and synthetic templates [30].

Structural Studies: When possible, conduct X-ray crystallography of polymerase-DNA-dNTP ternary complexes to visualize molecular interactions between synthetic nucleotides and polymerase active sites [30].

Diagram 1: Nucleotide Incorporation Assay

Evaluating Synthetic Polymer Mimics of Natural Proteins

Recent advances have enabled the creation of synthetic polymers that mimic specific functions of natural proteins using simplified building blocks [31] [32].

Experimental Protocol:

- Computational Design: Utilize deep learning algorithms (e.g., modified variational autoencoder) trained on natural protein databases (approximately 60,000 proteins) to identify key physicochemical parameters (charge distribution, hydrophobicity profiles) required for specific functions [32].

Monomer Selection: Select 2-6 synthetic building blocks (typically acrylate or methacrylate derivatives used in plastics) that match the identified physicochemical properties of the target natural protein [32].

Random Heteropolymer (RHP) Synthesis: Conduct controlled radical polymerization of selected monomers in specific ratios to create RHP libraries with statistical distributions of functional groups [32].

Functional Validation:

- For artificial blood plasma: Test ability to stabilize natural protein biomarkers without refrigeration using UV-Vis spectroscopy, circular dichroism, and ELISA assays [32].

- For artificial cytosol: Assess capability to support ribosomal protein synthesis in cell-free systems using radiolabeled amino acids or fluorescent tags [32].

- Perform single-molecule optical tweezers studies to compare RHP structural mechanics with natural proteins [32].

Biocompatibility Testing: Evaluate immune response, cytotoxicity, and degradation profiles using mammalian cell cultures and appropriate biological assays [32].

Research Reagent Solutions for Monomer Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Monomer and Polymerization Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Polymerases | Klenow Fragment (A family), Taq polymerase, Dpo4 (Y family) [30] | Study nucleotide incorporation efficiency & fidelity | Different families show varying ability to utilize synthetic nucleotides [30] |

| Synthetic Nucleotides | Abasic site analogs, Base analogs, Fluorescent nucleotides [30] | Probe DNA polymerase specificity & mechanism | Template or incoming dNTP position; reveals polymerase active site constraints [30] |

| Computational Tools | Modified Variational Autoencoders, Deep Learning Algorithms [32] | Design synthetic polymers mimicking natural proteins | Trained on natural protein databases to identify key physicochemical parameters [32] |

| Polymerization Initiators | Hydrogen peroxide, Azo compounds [28] | Free radical initiation for addition polymerization | Thermal cleavage generates free radicals with unpaired electrons [28] |

| Characterization Methods | Single-molecule optical tweezers, FRET, Mass spectrometry [30] [32] | Analyze polymer structure, mechanics & interactions | Reveals forces maintaining synthetic polymer structures vs natural proteins [32] |

Emerging Applications and Research Directions

Pseudo-Natural Products (PNPs) in Drug Discovery

Pseudo-natural products (PNPs) represent an innovative approach that combines natural product fragments in novel arrangements not accessible through natural biosynthesis pathways [27]. This strategy advances beyond the chemical space explored by nature by integrating principles of biology-oriented synthesis (BIOS) and fragment-based compound design. Notably, 60% of chemotherapeutic agents originate from natural products, highlighting the continued importance of natural monomer-derived compounds in drug discovery [27]. PNPs enable the exploration of alternative molecular scaffolds that maintain biological relevance while exhibiting improved drug-like properties compared to purely natural or synthetic compounds.

Research applications of PNPs focus primarily on target identification, mechanism of action studies, and development of new therapeutic agents for numerous diseases employing the newest techniques in pharmacology, biotechnology, and genetic engineering [27]. These compounds are particularly valuable for targeting protein-protein interactions and allosteric binding sites that have proven challenging for traditional small molecule drugs.

Synthetic Polymers as Protein Replacements

Groundbreaking research has demonstrated that synthetic polymers composed of just 2-6 building blocks can mimic specific functions of natural proteins, challenging the paradigm that biological complexity requires molecular diversity [31] [32]. These random heteropolymers (RHPs) successfully replicated functions of blood plasma by stabilizing natural protein biomarkers without refrigeration and even enhanced thermal stability of natural proteins—an improvement over real blood plasma [32]. Artificial cytosol created using this approach supported functional ribosomes that continued protein synthesis in test tube environments [32].

Diagram 2: Synthetic Polymer Design Workflow

The design framework employs deep learning methods to match natural protein properties with synthetic polymer characteristics, focusing primarily on electric charges and hydrophobicity rather than precise atomic-level structural mimicry [32]. This approach successfully "fools" biological systems into accepting synthetic polymers as part of the natural protein environment, opening possibilities for hybrid biological systems where plastic polymers interact seamlessly with natural proteins [32].

Natural-Synthetic Polymer Blends for Biomedical Applications

Blends of natural and synthetic polymers represent a growing research area that combines the biocompatibility of natural polymers with the mechanical strength and processability of synthetic polymers [33]. These hybrid materials are being developed for diverse biomedical applications including wound healing, tissue engineering, drug delivery systems, and medical implants [33].

Table 4: Applications of Natural-Synthetic Polymer Blends in Biomedicine

| Application Domain | Natural Polymer Component | Synthetic Polymer Component | Key Advantages | Current Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wound Healing | Chitosan, Collagen, Gelatin [33] | Polycaprolactone (PCL), Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) [33] | Enhanced fluid exchange, antimicrobial properties, improved healing | Advanced development for diabetic wound treatment [33] |

| Tissue Engineering | Silk fibroin, Collagen, Hyaluronic acid [33] | Polycaprolactone (PCL), Polylactic acid (PLA) [33] | Superior cell proliferation, mechanical resilience, biodegradability | Research phase with promising in vitro results [33] |

| Drug Delivery | Albumin, Chitosan [33] | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), Polyesters [33] | Controlled release kinetics, targeted delivery, reduced side effects | Several systems in clinical trials [33] |

| Nerve Regeneration | Chitosan, Collagen [33] | Polycaprolactone (PCL), Graphene-doped polymers [33] | Guided nerve growth, electrical conductivity in composites | Pre-clinical development for peripheral nerve repair [33] |

These blended systems address the mechanical limitations of natural polymers while maintaining biological recognition signals necessary for optimal tissue integration and function. Current research focuses on optimizing blend composition, manufacturing processes, and characterization methods to create materials with precisely tailored properties for specific clinical applications [33].

The distinction between natural and synthetic monomers continues to blur as research advances in areas such as pseudo-natural products, synthetic biological polymers, and sophisticated natural-synthetic hybrid systems. The future of monomer research lies in developing increasingly sophisticated integration strategies that leverage the unique advantages of both natural and synthetic building blocks.

Several key trends are likely to shape future research directions. AI-driven design of synthetic polymers will expand beyond current charge and hydrophobicity parameters to incorporate more sophisticated biomimetic principles [32]. The development of dynamic monomer systems that respond to environmental stimuli will enable "smart" polymers with adaptive properties. Sustainable sourcing of both natural and synthetic monomers will become increasingly important, with growing emphasis on renewable feedstocks and biodegradable polymer systems [33]. Additionally, the convergence of synthetic biology with polymer science will create new production pathways for monomeric building blocks through engineered metabolic pathways rather than traditional chemical synthesis.

As these fields continue to evolve, researchers will benefit from maintaining a holistic perspective that considers not only the structural and chemical properties of monomers but also their biological interactions, environmental impact, and manufacturing scalability. The most significant breakthroughs will likely emerge from interdisciplinary approaches that combine insights from chemistry, biology, materials science, and computational modeling to create the next generation of functional monomers and polymers.

Synthetic Strategies and Biomedical Breakthroughs: Applying Polymerization in Drug Delivery

Advanced heterogeneous polymerization techniques are fundamental to the production of a wide array of polymeric materials, from commodity plastics to specialized medical and electronic components. These processes—emulsion, miniemulsion, and suspension polymerization—enable precise control over molecular architecture, particle morphology, and final material properties by leveraging the principles of radical polymerization within compartmentalized environments. Within the broader context of monomer and polymerization process research, the selection of an appropriate technique is dictated by the target polymer's application, required purity, molecular weight, and particle characteristics. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of these core methods, emphasizing their mechanistic foundations, experimental protocols, and contemporary applications to equip researchers and scientists with the knowledge to navigate their development projects effectively.

Suspension polymerization is a heterogeneous radical polymerization technique where water-insoluble liquid monomers, along with oil-soluble initiators, are dispersed into droplets (typically 10-500 μm) within a continuous aqueous phase. The system is stabilized by suspending agents (e.g., polyvinyl alcohol or inorganic salts) and vigorous agitation, with each droplet functioning as an isolated micro-reactor. This process mimics bulk polymerization on a microscale, yielding discrete spherical polymer particles that are easily isolated by filtration or centrifugation [34].

Miniemulsion polymerization also involves dispersing a monomer phase in a continuous aqueous phase, but it produces much smaller droplets, typically in the submicron range (50-500 nm). A key distinction is the use of a surfactant and a costabilizer (a water-insoluble compound) to suppress Ostwald ripening, thereby achieving droplet stability for periods ranging from hours to months. Prevalent nucleation of these monomer droplets is a unique feature, minimizing the need for mass transfer through the aqueous phase during polymerization [35].

Emulsion polymerization traditionally relies on the nucleation of particles in monomer-swollen micelles (heterogeneous nucleation) or by precipitation of oligomers from the aqueous phase (homogeneous nucleation). Monomer droplets are large (1-10 μm) and generally do not serve as the primary locus for particle nucleation. The process requires a surfactant concentration above the critical micelle concentration (CMC) and typically uses water-soluble initiators [35].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Advanced Polymerization Techniques

| Feature | Suspension Polymerization | Miniemulsion Polymerization | Conventional Emulsion Polymerization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Droplet/Particle Size | 10 - 500 μm [34] | 50 - 500 nm [35] | Final particles: 10 - 200 nm; Monomer droplets: 1 - 10 μm [35] |

| Stabilizing System | Suspending agents (e.g., PVA, inorganic salts) [34] | Surfactant + Costabilizer (e.g., hexadecane, cetyl alcohol) [35] | Surfactant (above CMC) [35] |

| Initiator Type | Oil-soluble (e.g., BPO, AIBN) [34] | Oil-soluble [35] | Typically water-soluble [35] |

| Primary Locus of Nucleation | Monomer droplets [34] | Monomer droplets [35] | Micelles or aqueous phase [35] |

| Mass Transfer Dependence | Not applicable (isolated droplets) | Low (minimized via costabilizer) [35] | High (monomer diffuses from droplets) [35] |

| Key Advantage | Simple product isolation, high purity, efficient heat removal [34] | Incorporation of highly hydrophobic monomers, encapsulation [35] | High polymerization rates, high molecular weights [35] |

| Typical Applications | PVC, polystyrene beads, ion-exchange resins [34] | Hybrid polymers, controlled radical polymerization, encapsulation [35] | Synthetic rubber, paints, adhesives [35] |

Mechanism and Workflow Diagrams

Suspension Polymerization Mechanism

Suspension polymerization proceeds through a free-radical mechanism confined within individual monomer droplets. The process begins with the thermal decomposition of an oil-soluble initiator within the droplet, generating primary radicals that initiate chain growth with monomer molecules. Propagation continues within the isolated droplet, and termination occurs primarily via bimolecular radical recombination or disproportionation. The high surface area of the droplets and the high heat capacity of the surrounding aqueous phase facilitate efficient heat dissipation, mitigating the risk of runaway reactions due to the exothermic nature of polymerization [34].

Miniemulsion Polymerization Workflow

The miniemulsion process is characterized by a workflow that ensures the formation and polymerization of stable submicron droplets. The key steps include: 1) Preparation of a coarse pre-emulsion by mixing the aqueous and organic phases; 2) Subjecting the pre-emulsion to high-shear homogenization (e.g., ultrasonication or high-pressure homogenizers) to form minidroplets; 3) Polymerizing the stabilized miniemulsion using an oil-soluble initiator, with nucleation occurring primarily within the droplets [35].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Suspension Polymerization of Polystyrene Beads

This protocol outlines the synthesis of polystyrene beads, a classic application of suspension polymerization [34].

Dispersion Preparation:

- In a suitable reaction vessel equipped with a mechanical stirrer, condenser, and thermometer, prepare the aqueous continuous phase by dissolving 0.5 g of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA, Mw ~89,000-98,000, 99+% hydrolyzed) in 150 mL of deionized water. Heat gently (~60°C) with moderate stirring (200-300 rpm) until the PVA is fully dissolved.

- Prepare the monomer phase by mixing 30 g of purified styrene (inhibitor removed by passing through a basic alumina column) with 0.15 g of benzoyl peroxide (BPO, 75% remainder water). Ensure the initiator is completely dissolved in the monomer.

- Add the monomer phase to the aqueous phase in the reaction vessel. The typical monomer-to-water ratio in this protocol is 1:5.

Droplet Formation and Stabilization:

- Increase the agitation speed to 400-500 rpm to disperse the monomer phase into droplets. Maintain this speed for 20-30 minutes to achieve a stable dispersion of monomer droplets. The droplet size distribution is controlled by the balance between disruptive hydrodynamic forces and restorative interfacial tension.

Polymerization:

- Heat the reaction mixture to 70 ± 1 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere to initiate the decomposition of BPO.

- Maintain vigorous agitation and temperature for 6-8 hours. Monitor the reaction to ensure the droplet suspension remains stable and to prevent coalescence.

Product Isolation:

- After the reaction is complete, cool the mixture to room temperature.

- Isolate the polymer beads by filtration or centrifugation.

- Wash the beads repeatedly with deionized water and finally with methanol to remove any residual stabilizer or monomer.

- Dry the resulting polystyrene beads under vacuum at 50°C for 12 hours.

Protocol for Miniemulsion Polymerization with Hydrophobic Monomers

This protocol is designed for polymerizing hydrophobic monomers (e.g., lauryl methacrylate) that are difficult to handle via conventional emulsion polymerization due to diffusional limitations [35].

Miniemulsion Formulation:

- Prepare the aqueous phase by dissolving 0.5 g of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in 150 g of deionized water.

- Prepare the organic phase by mixing 30 g of lauryl methacrylate with 1.2 g of hexadecane (as costabilizer) and 0.18 g of lauroyl peroxide.

Pre-emulsification and Homogenization:

- Combine the aqueous and organic phases with mild magnetic stirring to form a coarse pre-emulsion.

- Subject the coarse pre-emulsion to high-shear homogenization. Using a ultrasonic processor (e.g., 400 W, ½" tip), sonicate the mixture for 5 minutes at 80% amplitude while cooling in an ice bath to dissipate heat. Alternatively, use a high-pressure homogenizer at 5000 psi for 5 cycles.

Polymerization:

- Transfer the resulting milky miniemulsion to a reactor equipped with a stirrer, condenser, and nitrogen inlet.

- Purge the system with nitrogen for 20 minutes to remove oxygen while stirring at 200 rpm.

- Heat the reaction to 70 ± 1 °C to initiate polymerization. Continue the reaction for 4-6 hours.

Latex Characterization:

- Cool the final latex to room temperature.

- Analyze the particle size and distribution using dynamic light scattering (DLS). Filter the latex through a glass wool plug to remove any coagulum before analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Advanced Polymerization

| Reagent/Material | Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | Suspending agent / Stabilizer | Provides steric stabilization in suspension polymerization; molecular weight and degree of hydrolysis affect droplet size and stability [34]. |

| Benzoyl Peroxide (BPO) | Oil-soluble initiator | Common radical initiator for suspension and miniemulsion; half-life should align with reaction duration (e.g., ~10h at 70°C) [34]. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Surfactant | Anionic surfactant used in emulsion and miniemulsion to lower interfacial tension and stabilize droplets/particles [35]. |