Molecular Weight Distribution in Polymers: Fundamentals, Analysis, and Impact on Drug Delivery Systems

This article provides a comprehensive overview of molecular weight distribution (MWD) in polymers, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Molecular Weight Distribution in Polymers: Fundamentals, Analysis, and Impact on Drug Delivery Systems

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of molecular weight distribution (MWD) in polymers, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It covers foundational concepts, including the definitions of Mn, Mw, Mz, and the polydispersity index (PDI), and explains how MWD intrinsically influences key polymer properties. The piece details state-of-the-art characterization techniques like SEC/GPC and light scattering, and explores the application of MWD control in designing advanced materials, such as ultra-high molecular weight polymers and sustained-release drug formulations. Furthermore, it addresses common challenges in MWD analysis and optimization, and discusses the critical role of MWD in validating polymer performance for biomedical applications, including its impact on drug release profiles and crystallization behavior.

The Fundamentals of Polymer Molecular Weight Distribution: Why Mn, Mw, and PDI Matter

In polymer science, the molecular weight (more accurately, molar mass) is a fundamental property that dictates material characteristics such as tensile strength, viscosity, elasticity, and processability [1] [2]. Unlike small molecules or monodisperse biological polymers like proteins, synthetic polymers are complex mixtures composed of chains of varying lengths [1] [3]. Consequently, a polymer sample does not possess a single molecular weight but rather a distribution of molecular weights [1] [4]. This distribution arises from the random nature of polymerization kinetics, where individual polymer chains terminate or grow at different rates [5]. The molecular weight distribution (MWD) is thus a critical quality index, providing comprehensive insight into the molecular structure of polymeric materials and their anticipated performance [5]. Characterizing this distribution requires specific averaging methods, the most fundamental of which are the number-average (Mn), weight-average (Mw), and z-average (Mz) molecular weights. These parameters are indispensable for researchers and scientists, particularly in fields like drug development where polymer properties can influence drug encapsulation, release profiles, and biocompatibility.

Defining the Molecular Weight Averages

Mathematical Foundations and Formulas

The different molecular weight averages are defined as statistical moments of the molecular weight distribution, each providing a unique perspective on the population of polymer chains [4]. The following table summarizes the key definitions and their mathematical formulations.

Table 1: Summary of Molecular Weight Averages

| Average Type | Symbol | Mathematical Definition | Basis of Calculation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number-Average | ( M_n ) | ( Mn = \frac{\sum{i} Ni Mi}{\sum{i} Ni} ) | Total weight of polymer divided by the total number of molecules [1] [6] [4]. |

| Weight-Average | ( M_w ) | ( Mw = \frac{\sum{i} Ni Mi^2}{\sum{i} Ni M_i} ) | Weighted according to the mass fraction of each chain size [1] [7] [4]. |

| Z-Average | ( M_z ) | ( Mz = \frac{\sum{i} Ni Mi^3}{\sum{i} Ni M_i^2} ) | A higher-order average, sensitive to even larger molecules [4]. |

Where:

- ( Ni ) is the number of molecules of molecular weight ( Mi ) [1].

- The summations are over all the different molecular weights present in the sample.

These definitions can also be expressed in terms of fractions:

- ( Mn = \sum xi Mi ), where ( xi ) is the mole fraction of molecules with weight ( M_i ) [1].

- ( Mw = \sum wi Mi ), where ( wi ) is the weight fraction of molecules with weight ( M_i ) [1] [7].

A Calculated Example

The distinction between ( Mn ) and ( Mw ) is best illustrated with a practical example. Consider a hypothetical polymer sample with the following distribution of molecules [7]:

Table 2: Example Calculation of ( M_n ) and ( M_w )

| Number of Molecules ((N_i)) | Mass of Each Molecule ((M_i)) | Total Mass per Type ((Ni Mi)) | Weight Fraction ((w_i)) | (wi \times Mi) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 800,000 | 800,000 | 0.016 | 12,800 |

| 3 | 750,000 | 2,250,000 | 0.045 | 33,750 |

| 5 | 700,000 | 3,500,000 | 0.070 | 49,000 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| ΣNᵢ = 100 | ΣNᵢMᵢ = 50,000,000 | Σwᵢ = 1.00 | ΣwᵢMᵢ = 531,600 |

Calculating Averages:

- Number-Average Molecular Weight ((Mn)): The total mass is divided by the total number of molecules. ( Mn = \frac{\sum Ni Mi}{\sum N_i} = \frac{50,000,000}{100} = 500,000 ) [7].

- Weight-Average Molecular Weight ((Mw)): The weight fractions are used. ( Mw = \sum wi Mi = 531,600 ) [7].

This example clearly shows that ( Mw ) is greater than ( Mn ) because the larger molecules contribute more significantly to the calculation of ( M_w ).

The Polydispersity Index (PDI)

The Polydispersity Index (PDI), also known as dispersity, is a single value that describes the breadth of the molecular weight distribution [1] [4]. It is defined as the ratio of the weight-average molecular weight to the number-average molecular weight: [ \text{PDI} = \frac{Mw}{Mn} ]

A PDI has a value greater than or equal to one [1]. A value of 1.0 indicates a monodisperse sample where all polymer chains are identical in length, a scenario approached by some proteins but never achieved for synthetic polymers [1] [2]. A value significantly greater than 1 indicates a polydisperse sample with a wide distribution of chain lengths. In the example above, the PDI is ( 531,600 / 500,000 = 1.063 ), indicating a relatively narrow distribution [7]. In general, the averages are related as follows: ( Mn < Mv < Mw < Mz ), where ( M_v ) is the viscosity-average molecular weight [4].

Experimental Protocols for Determination

The determination of these molecular weight averages relies on specific experimental techniques, as each method measures a different physical property of the polymer molecules in solution.

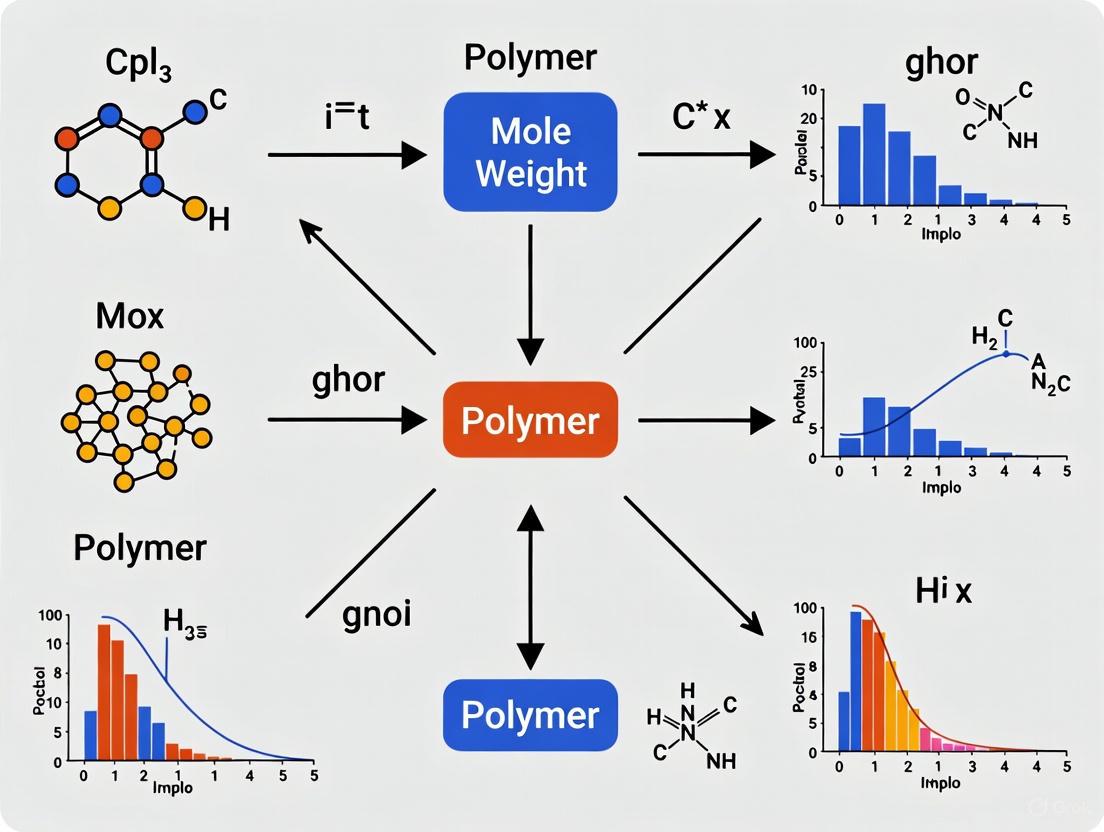

Figure 1: Experimental techniques for molecular weight determination and the primary average they measure.

Absolute Methods for Number-Average ((M_n))

Colligative Property Methods: Osmometry Principle: Techniques such as membrane osmometry and vapor pressure osmometry measure (M_n) by assessing the colligative properties of a polymer solution, which depend solely on the number of solute particles present, not their size or mass [6] [4]. These properties include boiling point elevation, freezing point depression, vapor pressure lowering, and osmotic pressure [6]. Detailed Protocol (Freezing Point Depression - Cryoscopy):

- Apparatus Setup: A known mass (15-20 g) of pure solvent is placed in a test tube. A stir bar and a precision thermometer (e.g., Beckmann thermometer) are inserted, and the tube is sealed with a rubber stopper [8].

- Freezing Point of Pure Solvent: The test tube apparatus is immersed in a freezing bath (e.g., ice-water). The solvent is stirred continuously and allowed to equilibrate to a few degrees below its freezing point. The temperature at which the solvent crystallizes and remains constant is recorded as the freezing point of the pure solvent ((T_f^\text{solvent})) [8].

- Freezing Point of Solution: The test tube is warmed to melt the solvent. A precisely weighed amount of the polymer solute is dissolved in the solvent. The apparatus is placed back into the freezing bath, and the freezing point of the solution ((T_f^\text{solution})) is determined in the same manner.

- Calculation: The freezing point depression ((\Delta Tf = Tf^\text{solvent} - Tf^\text{solution})) is used to calculate the molality of the solution ((m)) using the formula (\Delta Tf = Kf \cdot m), where (Kf) is the cryoscopic constant specific to the solvent (e.g., 5.12 K·kg/mol for benzene) [8]. The number-average molecular weight is then derived from the molality and the mass of the solute.

End-Group Analysis Principle: This method is applicable to polymers with detectable reactive functional end groups, such as carboxyl-terminated polybutadiene (CTPB) or polyesters [6]. By quantifying the number of end groups per unit mass of polymer, one can calculate the number of polymer chains. Detailed Protocol (Titration of Carboxyl Groups):

- A small, precisely weighed quantity of polymer (e.g., ~0.9 g) is dissolved in a suitable solvent mixture (e.g., toluene and ethanol) [6].

- The solution is titrated with a standardized alcoholic potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution (e.g., 0.125 N) using an indicator like phenolphthalein [6].

- The carboxyl value (number of grams of KOH equivalent to the carboxyl groups in 100 g of polymer) is calculated from the volume of KOH consumed, its normality, and the sample mass [6].

- For a linear polymer with two carboxyl ends per chain, the number-average molecular weight is calculated as: ( M_n = \frac{2 \times \text{(Mass of KOH equivalent per mole)}}{\text{Carboxyl Value}} \times 100 ) [6].

Absolute Methods for Weight-Average ((Mw)) and Z-Average ((Mz))

Static Light Scattering (SLS) Principle: A beam of light is passed through a polymer solution, and the intensity of the light scattered by the polymer molecules is measured, typically at multiple angles [4] [3]. The intensity of the scattered light is directly proportional to the molecular weight of the scattering molecules and their concentration. Multi-angle laser light scattering (MALLS) is a common implementation of this technique [4] [3]. Protocol Outline:

- Sample Preparation: The polymer is dissolved in a suitable solvent to create a series of dilutions (e.g., 3-5 concentrations).

- Measurement: The scattering intensity of each solution and the pure solvent (for background subtraction) is measured at multiple angles.

- Data Analysis (Debye Plot): The data is analyzed using a Zimm or Debye plot, where (Kc/R\theta) is plotted against concentration and angle. Here, (K) is an optical constant, (c) is the concentration, and (R\theta) is the reduced scattering intensity. The y-intercept of this plot yields (1/M_w) directly, providing an absolute molecular weight without the need for calibration standards [4] [3]. A key requirement is the knowledge of the polymer's specific refractive index increment ((dn/dc)) in the solvent used [3].

Analytical Ultracentrifugation (Sedimentation) Principle: This method subjects a polymer solution to a powerful centrifugal force. Heavier and larger molecules sediment faster, allowing for the determination of (M_z) [4]. Protocol Outline:

- The polymer solution is placed in a cell within a rotor that is spun at high speeds in an ultracentrifuge.

- The concentration distribution of the polymer along the length of the cell is monitored over time, often using optical systems like Schlieren or interference optics.

- The sedimentation data is analyzed to calculate the sedimentation and diffusion coefficients, which are then used to determine the z-average molecular weight, (M_z) [4].

Chromatographic and Relative Methods

Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) / Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) Principle: This is the most widely used technique for determining molecular weight distributions. A polymer solution is forced through a column packed with a porous gel [4] [3]. Smaller molecules can enter more pores and thus have a longer path and longer retention time, while larger molecules are excluded from smaller pores and elute first. The retention volume is related to the hydrodynamic volume of the polymer molecule. Detector Configurations and Data Quality:

- Relative Molecular Weight: Using only a concentration detector (e.g., differential refractive index), the retention volume is compared to a calibration curve built using narrow dispersity polymer standards (e.g., polystyrene) [3]. The reported molecular weights are "relative" to these standards and will be inaccurate if the polymer's structure differs significantly from the standards [3].

- Universal Calibration Molecular Weight: Adding an online viscometer detector allows for the application of the "universal calibration" principle, which states that polymers of the same hydrodynamic volume elute at the same volume. This method accounts for differences in polymer structure (e.g., branching) and provides more accurate molecular weights across different polymer types [3].

- Absolute Molecular Weight: Coupling SEC with multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALLS) is the gold standard. The light scattering detector directly measures (M_w) at each elution slice, independent of retention volume, while the concentration detector provides the corresponding concentration. This combination provides absolute molecular weights and detailed information on the molecular weight distribution [4] [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Molecular Weight Analysis

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Narrow Dispersity Polymer Standards | Used to calibrate SEC/GPC systems. Common standards include polystyrene, polyethylene oxide, and polymethyl methacrylate, with known (M_w) and low PDI [3]. |

| High-Purity Solvents (HPLC Grade) | Used to dissolve polymer samples and standards for SEC/GPC, light scattering, and osmometry. Must be free of dust and impurities to avoid signal noise and column damage [8]. |

| Salts and Buffers | For preparing specific solvent environments, especially for biologically relevant polymers or when using aqueous SEC (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline). |

| Refractive Index Increment ((dn/dc)) Standards | Known compounds (e.g., toluene) used to calibrate or verify the (dn/dc) value for a solvent, which is a critical parameter for absolute molecular weight determination via light scattering [3]. |

| Standardized Titrants | Precisely known concentration solutions (e.g., alcoholic KOH) used in end-group analysis to quantify the number of functional groups in a polymer sample [6]. |

| Porous GPC/SEC Columns | The stationary phase in chromatography that separates polymer molecules based on their hydrodynamic size in solution [4] [3]. |

The accurate definition and determination of molecular weight averages—(Mn), (Mw), and (Mz)—are foundational to advanced polymer research. These parameters, along with the polydispersity index, provide a multi-faceted view of the molecular weight distribution that is intricately linked to a polymer's macroscopic properties. The choice of analytical technique, from classical colligative methods for (Mn) to sophisticated hyphenated SEC-light scattering systems for absolute (M_w) and full distribution analysis, is critical. For researchers in drug development, where polymers are used in formulations, coatings, and as active pharmaceutical ingredients themselves, a deep understanding of these averages is not merely academic. It is essential for achieving consistent product quality, predictable performance, and meeting stringent regulatory requirements. As polymerization modeling advances, the ability to predict and control these distributions, such as through analytical expressions for steady-state processes, continues to grow in importance [5].

Understanding Polydispersity Index (PDI) as a Measure of MWD Breadth

In polymer science, unlike small molecules, a polymer sample does not possess a single molecular weight but comprises a mixture of chains of varying lengths. This distribution of chain lengths is described by the Molecular Weight Distribution (MWD), a fundamental characteristic that profoundly influences a polymer's physical and mechanical properties [9]. The Polydispersity Index (PDI), also referred to simply as dispersity (Đ), is a single parameter that quantifies the breadth of this MWD [10] [11]. It provides a measure of the heterogeneity of molecular weights within a given polymer sample. A collection of polymer chains is considered uniform if the chains have the same length, and non-uniform if the chain lengths vary widely [11]. The ability to measure and control PDI is therefore critical for tailoring polymers to specific applications, from drug delivery systems to high-performance materials.

The concept of PDI has been integral to polymer science since its early days. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) now recommends the term "dispersity" (symbol Đ) over "polydispersity index," though both terms are used extensively in the literature [11]. Initially, PDI was measured using techniques such as fractionation and light scattering. However, the advent of Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), also known as Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC), has made the measurement of MWD and PDI more accurate and efficient [9] [12]. These advanced techniques have enabled researchers to precisely determine the MWD of polymers, leading to a better understanding of the relationship between PDI and ultimate polymer properties.

Theoretical Foundations of PDI

Defining the Averages: Mn, Mw, and the PDI Calculation

The calculation of PDI relies on two primary average molecular weights: the number-average molecular weight (Mn) and the weight-average molecular weight (Mw). These averages are defined by the following equations [12]:

[ Mn = \frac{\sum Ni Mi}{\sum Ni} ]

[ Mw = \frac{\sum Ni Mi^2}{\sum Ni M_i} ]

Here, (Ni) is the number of molecules with a molecular weight of (Mi). The number-average molecular weight, (Mn), is a simple arithmetic mean, sensitive to the total number of polymer chains regardless of their size. In contrast, the weight-average molecular weight, (Mw), is weighted towards the mass of the molecules, making it more sensitive to the presence of higher molecular weight chains in the distribution.

The Polydispersity Index (PDI) is then calculated as the ratio of these two averages [10] [11] [12]:

[ PDI = \frac{Mw}{Mn} ]

This ratio provides a dimensionless measure of the broadness of the MWD. Its value is always greater than or equal to 1.

Interpreting PDI Values

The value of the PDI offers a quick snapshot of the uniformity of a polymer sample:

- Đ ≈ 1.0: Indicates a uniform (or monodisperse) polymer, where all chains are nearly the same length. Natural polymers like proteins and DNA often exhibit this characteristic, and it can be approached with highly controlled synthetic methods like living anionic polymerization [10] [11].

- Đ > 1.0: Indicates a non-uniform (or polydisperse) polymer, with a broad distribution of chain lengths. Most synthetic polymers fall into this category, with PDI values varying based on the polymerization mechanism and conditions [10].

Table: Typical PDI Values for Different Polymerization Methods [10] [11]

| Polymerization Method | Typical PDI Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Living Anionic Polymerization | ~1.0 (e.g., 1.01–1.10) | Achieves near-uniform chains; used for calibration standards [10]. |

| Step-Growth Polymerization | ~2.0 | Theoretical limit described by Carothers' equation [10] [11]. |

| Free Radical Polymerization | 1.5 – 20 (Often ~2.0) | Broad range due to random chain termination events [10] [11]. |

| Controlled Radical Polymerization | ~1.1 – 1.5 | Includes ATRP, RAFT; offers a balance of control and monomer scope [9]. |

Figure 1: Interpretation of PDI values and their correlation with common polymerization techniques.

Experimental Determination of PDI

Core Measurement Techniques

The primary technique for determining MWD and calculating PDI is Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), also known as Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) [9] [12]. In this chromatographic method, a polymer solution is passed through a column packed with a porous gel. Smaller polymer chains can penetrate the pores more easily and thus take a longer path through the column, resulting in a longer retention time. Larger chains are excluded from smaller pores and elute first. By detecting the concentration of polymer in the eluent, a chromatogram is generated, from which the MWD, (Mn), (Mw), and consequently the PDI, can be determined relative to standards of known molecular weight [9].

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) is another vital technique, particularly for characterizing nanoparticles, liposomes, and other colloidal systems in suspension [13] [14]. DLS measures the fluctuations in scattered light intensity caused by the Brownian motion of particles. The diffusion coefficient is derived from these fluctuations and converted to a hydrodynamic diameter via the Stokes-Einstein equation. DLS analysis, often using the cumulant method, provides a z-average hydrodynamic size and a polydispersity index (PDI({}_{\text{DLS}})) that reflects the width of the size distribution [14]. It is crucial to note that the PDI from DLS relates to the distribution of particle sizes, not directly to the molecular weight distribution of individual polymer chains, though for polymeric nanoparticles the two are closely linked.

Detailed Protocol: Determining PDI of Liposomal Nanoparticles via DLS

Liposomal nanoparticles are a key drug delivery system, and their size and PDI are critical quality attributes [13] [15]. The following protocol outlines a standard procedure for preparing and characterizing liposomes.

1. Materials and Reagents Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Liposome Preparation [15] [16]

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Phospholipids (e.g., HSPC, DPPG) | Main structural lipid components forming the bilayer. |

| Cholesterol | Incorporated to enhance membrane stability and rigidity. |

| DSPE-mPEG2000 | PEGylated lipid used for "stealth" properties, reducing immune clearance. |

| Organic Solvent (e.g., Chloroform) | Solvent for dissolving lipids during thin film formation. |

| Hydration Buffer (e.g., PBS, NaCl solution) | Aqueous medium for hydrating the lipid film and forming liposomes. |

| Drug/Active Compound | The active pharmaceutical ingredient to be encapsulated (e.g., Zinc sulfate [16], Curcumin [15]). |

2. Methodology

- Thin Film Hydration: Lipids are dissolved in an organic solvent (e.g., chloroform) in a round-bottom flask. The solvent is then evaporated under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator, forming a thin, uniform lipid film on the inner wall of the flask. The film is further dried under a nitrogen stream or in a vacuum desiccator to remove residual solvent [15] [16].

- Hydration: The dried lipid film is hydrated with an aqueous buffer (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline or a solution of the active compound) at a temperature above the phase transition temperature ((T_m)) of the phospholipids. This process produces large, multilamellar vesicles (MLVs) [15] [16].

- Size Reduction: The MLV suspension is processed to achieve smaller, more uniform vesicles. Common methods include:

- Sonication: The suspension is subjected to ultrasonic energy using a probe or bath sonicator to form small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) [15].

- Extrusion: The suspension is passed repeatedly through polycarbonate membranes with defined pore sizes (e.g., 400 nm down to 50 nm or 100 nm) using a thermobarrel extruder [15].

3. Characterization via DLS [13] [14] [15]

- The liposome suspension is diluted appropriately in a clean, dust-free cuvette.

- The cuvette is placed in the DLS instrument, which measures the intensity autocorrelation function at a controlled temperature (e.g., 25°C).

- The data are analyzed using the cumulant method to obtain the z-average hydrodynamic diameter and the PDI. For a high-quality, monodisperse formulation, a PDI value of less than 0.2-0.3 is typically targeted, indicating a narrow size distribution [13] [15] [16]. The NNLS (non-negative least squares) inversion method can also be applied to obtain a size distribution histogram, though this method requires careful interpretation [14].

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for the preparation and PDI characterization of liposomal nanoparticles.

The Impact of PDI on Polymer and Nanoparticle Properties

The dispersity of a polymer sample is not merely a statistical descriptor; it has profound implications on its physical, mechanical, and rheological properties, which in turn dictate its performance in various applications.

- Mechanical Properties: Polymers with a low PDI (narrow MWD) tend to have more predictable and superior mechanical properties. The uniform chain lengths allow for tighter molecular packing and more efficient load transfer, leading to higher strength, stiffness, and toughness [17] [12]. In contrast, the presence of low molecular weight chains in a high-PDI polymer can act as defects, reducing overall mechanical performance [12].

- Thermal Properties: A narrow MWD results in more defined thermal transitions. Monodisperse polymers exhibit sharper melting points and more distinct crystallization behavior. Polydisperse polymers, however, have a broader melting range and less distinct transitions due to the presence of chains with different thermal stabilities [17] [12].

- Rheological Behavior: The flow behavior of polymers is significantly affected by PDI. Low PDI polymers generally have more predictable rheology, such as a consistent viscosity profile. High PDI polymers can exhibit more complex, non-Newtonian behavior due to the entanglement of long chains and the lubricating effect of short chains, affecting processes like extrusion and injection molding [17] [12].

- Performance in Drug Delivery: For lipid-based nanocarriers like liposomes, the PDI (as a measure of size distribution) is a critical quality attribute. A low PDI ensures uniform cellular uptake, predictable drug release profiles, and consistent in vivo behavior, including bio-distribution and circulation time [13]. Nanoparticles with a high PDI may have inconsistent behavior, as smaller particles might distribute to different tissues compared to larger ones [13].

Controlling and Tuning PDI in Polymer Synthesis

The inherent PDI of a polymer is primarily determined by the mechanism of its polymerization. However, advanced synthetic strategies have been developed to exercise precise control over the MWD.

- Polymerization Mechanism: The choice of polymerization method is the first step in controlling PDI. Living polymerizations (e.g., anionic, cationic) offer the highest level of control, capable of producing polymers with PDI values very close to 1 [10] [11]. Controlled radical polymerizations (e.g., ATRP, RAFT) are versatile techniques that provide polymers with low PDI (≈1.1–1.5) while tolerating a wider range of functional groups and reaction conditions [9]. Conventional free radical and step-growth polymerizations typically yield polymers with higher, less controlled PDI values [10].

- Advanced Synthetic Strategies:

- Temporal Regulation of Initiation: This sophisticated method involves controlling the rate at which initiator is added to the polymerization reaction. By modulating the initiator feed rate, researchers can tailor both the dispersity and the shape (symmetry) of the MWD without changing the number-average molecular weight ((M_n)). This has been successfully demonstrated in both Nitroxide-Mediated Polymerization (NMP) and anionic polymerization, allowing for the production of polymers with predefined, often broadened, MWDs for specific applications [9].

- Polymer Blending: A more traditional but effective method to achieve a target dispersity is the physical blending of two or more pre-synthesized polymers with different, well-defined molecular weights. While straightforward, this approach often results in bimodal or multimodal MWDs, which may not be suitable for all applications [9].

- Catalyst and Reactor Engineering: In catalytic polymerizations (e.g., Ziegler-Natta), varying the catalyst concentration or using mixed catalyst systems can influence the PDI of the resulting polymer [9]. Furthermore, the type of reactor used (e.g., batch reactor vs. Continuous Stirred-Tank Reactor (CSTR)) can significantly impact the MWD, especially for living and step-growth polymerizations, due to differences in residence time distributions [11].

The Polydispersity Index is far more than a simple descriptor; it is a fundamental parameter that bridges the gap between polymer synthesis, characterization, and application performance. A deep understanding of PDI—from its theoretical underpinnings to its practical measurement and control—is indispensable for researchers and scientists designing next-generation polymeric materials and nanomedicines. As polymer science continues to advance, the strategic tuning of MWD breadth will remain a powerful tool for optimizing material properties, whether the goal is to achieve the uniform behavior required for a biomedical device or the tailored performance of a specialized industrial coating. The ongoing development of sophisticated synthesis and characterization techniques will further enhance our ability to precisely engineer polymers with dispersities tailored for specific functions.

The Direct Influence of MWD on Mechanical, Thermal, and Rheological Properties

Molecular Weight Distribution (MWD) is a fundamental characteristic of synthetic polymers, describing the statistical distribution of individual polymer chain lengths within a given sample. Unlike small molecules, polymers are polydisperse, consisting of chains of varying lengths, and the breadth and shape of this distribution intrinsically govern material properties [18]. The MWD is not merely a statistical parameter but a central design variable that directly dictates the performance and processability of polymeric materials across research and industrial applications, from drug delivery systems to high-performance thermoplastics [19] [20]. This whitepaper delineates the direct, mechanistic influence of MWD on the mechanical, thermal, and rheological properties of polymers, providing a foundational context for a broader thesis on MWD in polymer research. For researchers and scientists, a precise understanding of these structure-property relationships is paramount for the molecular design of next-generation materials, enabling the targeted optimization of properties such as tensile strength, impact resistance, thermal stability, and melt flow behavior [18] [21].

Fundamental Concepts of Molecular Weight Distribution

The molecular weight of a polymer is typically described by its average, most commonly the number-average molecular weight (Mₙ) and weight-average molecular weight (Mᵥ). The dispersity (Đ, also known as polydispersity index, PDI), defined as the ratio Mᵥ/Mₙ, quantifies the breadth of the MWD [19]. A Đ of 1 indicates a perfectly monodisperse polymer, while higher values signify a broader distribution of chain lengths.

Critically, a polymer's properties are not solely determined by average molecular weight but by the entire shape of the MWD curve [19] [21]. This shape includes the relative proportions of low molecular weight (LMW) and high molecular weight (HMW) components. LMW chains generally act as plasticizers, enhancing chain mobility and processability, whereas HMW chains contribute to mechanical integrity through increased chain entanglement density [18] [22]. The cooperative and often competing roles of these different chain fractions underlie the complex property profiles observed in polydisperse systems. The ability to precisely control MWD breadth and shape—moving beyond simple blending to tailored distributions—has emerged as a key frontier in polymer science, enabling the creation of materials with previously unattainable combinations of properties [19] [20] [21].

Influence of MWD on Mechanical Properties

The mechanical performance of a polymer, including its tensile strength, toughness, and impact resistance, is profoundly affected by its MWD. The underlying mechanism involves the synergistic effect of different molecular weight fractions on the formation of the polymer's solid-state structure, particularly its crystalline morphology.

Mechanisms and Structural Relationships

The primary mechanism through which MWD influences mechanical properties is molecular segregation during crystallization [18]. In a polydisperse melt, LMW and HMW chains do not co-crystallize uniformly. HMW components, with their higher entanglement density, often nucleate first but exhibit slower crystallization kinetics. LMW components, possessing higher chain mobility, can subsequently crystallize into distinct regions, leading to a spatially heterogeneous crystalline texture [18]. For instance, in poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) blends, this segregation results in composite structures with thin-lamellar dendrites in the interior (rich in HMW chains) surrounded by thicker lamellae at the periphery (rich in LMW chains) [18]. This spatial distribution of MWD directly creates a composite crystalline texture, which is key to the material's mechanical performance.

Furthermore, LMW components are more likely to form extended-chain crystals or exhibit a higher ratio of chains exiting lamellae without folding. This behavior influences the formation of tie molecules and dangling chains that interconnect crystalline regions, thereby enhancing toughness and impact resistance by facilitating stress transfer across the material [18]. Conversely, the HMW fractions, through their high entanglement density, form the backbone of the amorphous phase, providing the strength and creep resistance essential for load-bearing applications [18] [22].

Quantitative Effects and Experimental Data

The relationship between MWD and key mechanical properties is quantified in the table below, synthesizing data from research on polymers like high-density polyethylene (HDPE) and emulsion copolymers.

Table 1: Influence of MWD on Key Mechanical Properties

| Mechanical Property | Narrow MWD | Broad MWD | Mechanistic Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength | High and consistent [22] | Can be high, but less consistent [22] | High entanglement density from HMW fractions; consistent crystalline morphology. |

| Impact Resistance / Toughness | Can be lower [22] | Enhanced [22] | LMW fractions fill voids and facilitate energy dissipation; formation of tie molecules. |

| Strain at Break | Less sensitive to MWD shape [21] | Less sensitive to MWD shape [21] | Governed by fundamental material strength, independent of MWD skew in HDPE [21]. |

| Overall Consistency | Predictable and uniform performance [22] | Variable, requires precise processing control [22] | Uniform chain lengths lead to consistent crystallization and entanglement. |

A pivotal study on HDPE demonstrated that while the strain at break remained unaffected, the MWD shape (specifically, its skew) had a measurable impact on rheological and processing behavior without compromising this key indicator of material strength [21]. This finding is critical for product design, as it allows for the independent tuning of processability and mechanical integrity.

Influence of MWD on Thermal Properties

The thermal behavior of a polymer, including its melting temperature, crystallinity, and crystallization kinetics, is intrinsically governed by the MWD. Different chain lengths possess varying propensities to nucleate, fold, and incorporate into the crystal lattice, leading to MWD-dependent thermal profiles.

Crystallization Kinetics and Morphology

MWD exerts a governing effect on both the nucleation and growth stages of polymer crystallization [18]. LMW chains, with their high mobility, can rapidly diffuse to the growth front and crystallize quickly. However, very short chains (e.g., polyethylene below 5000 g/mol) may not co-crystallize at all under certain conditions [18]. HMW chains, despite their slow dynamics, can act as effective nucleation sites due to their ability to form stable nuclei with multiple chain folds [18]. In a polydisperse system, these behaviors occur synergistically. The Lauritzen−Hoffman model accounts for this by including an additional energy barrier for HMW chains, representing the energy required to disentangle and reel the chain into the crystal [18].

This molecular segregation during crystallization directly determines the resulting crystalline morphology. Research has shown that the curvature of edge-on lamellae in poly(L-lactide)/poly(D-lactide) (PLLA/PDLA) stereocomplexes is dictated by the chirality of the LMW component [18]. This is because LMW chains have a higher propensity to form extended chains (a higher "unfolding ratio"), which generates surface stress on the lamellae, causing them to curve and twist [18]. The final crystallinity and the distribution of lamellar thicknesses are thus a direct consequence of the initial MWD.

Melting Behavior and Thermal Stability

The melting temperature (Tₘ) of a polymer is closely related to lamellar thickness, with thicker crystals melting at higher temperatures. Since MWD influences the range and distribution of lamellar thicknesses, it directly broadens the melting endotherm. A narrow MWD typically results in a sharper melting peak, whereas a broad MWD leads to a wide melting range, reflecting the coexistence of thin (from LMW) and thick (from HMW) lamellae [18]. Furthermore, the thermal stability of the material is enhanced by the HMW fraction, as the high entanglement density impedes chain mobility and flow at elevated temperatures [18].

Table 2: Summary of MWD Effects on Thermal Properties

| Thermal Property | Influence of LMW Components | Influence of HMW Components | Overall System Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleation | Fast diffusion, but may not form stable nuclei [18] | Form stable nuclei with multiple folds; act as nucleation sites [18] | Cooperative nucleation; rate depends on MWD shape and temperature. |

| Crystal Growth | High growth rate due to high mobility [18] | Slow growth due to slow relaxation and high entanglement [18] | Complex growth kinetics; molecular segregation leads to spatial MWD. |

| Crystalline Morphology | Form thicker, extended-chain lamellae at crystal edges [18] | Form thin lamellae with non-integer folding in crystal interior [18] | Composite structures (e.g., nested spherulites); defines final property profile. |

| Melting Behavior | Lower melting point due to thinner crystals. | Higher melting point potential from thicker crystals. | Broader MWD results in a broader melting range. |

Experimental Protocol: Investigating MWD Effects on Crystallization

Objective: To observe the effect of MWD on the isothermal crystallization kinetics and resulting crystalline morphology of a semicrystalline polymer.

Materials:

- Polymer samples with identical average molecular weight but different MWDs (e.g., narrow dispersity vs. broad dispersity).

- Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC).

- Polarized Optical Microscope (POM) with a hot stage.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Place a few milligrams of each polymer sample into sealed DSC pans.

- Erase Thermal History: Heat the samples in the DSC to a temperature 30°C above their melting point at a standard rate (e.g., 10°C/min). Hold at this temperature for 5 minutes to erase any previous thermal and mechanical history.

- Isothermal Crystallization: Rapidly quench the samples (at a controlled rate of 50-100°C/min) to a predetermined isothermal crystallization temperature (T꜀). Hold at T꜀ and monitor the heat flow as a function of time until the crystallization exotherm is complete.

- Data Analysis: Analyze the DSC exotherms to determine the half-time of crystallization (t₁/₂) and the overall crystallization rate. The evolution of relative crystallinity with time can be modeled using the Avrami equation.

- Morphological Observation (Parallel Experiment): For each sample, prepare a thin film on a microscope slide. Repeat the thermal program (melt-hold-quench to T꜀) in the hot stage attached to the POM. Record the development and growth of spherulites in real-time, noting the nucleation density and final spherulitic texture.

Expected Outcome: The polymer with a broader MWD will likely exhibit a broader crystallization exotherm and a more complex spherulitic morphology due to molecular segregation, compared to the narrow MWD sample.

Influence of MWD on Rheological Properties

The rheological behavior of a polymer melt—its deformation and flow under stress—is critically important for processing and is one of the properties most sensitive to MWD. The MWD dictates the entanglement network and relaxation dynamics of the polymer chains.

Melt Viscosity and Shear Thinning

A polymer's zero-shear viscosity is strongly dependent on its molecular weight, typically scaling with Mᵥ to the 3.4 power above the critical molecular weight for entanglement. Consequently, the HMW fractions in a polydisperse sample disproportionately contribute to the melt viscosity [22]. A broad MWD polymer will generally have a higher melt viscosity at low shear rates compared to a narrow MWD polymer of the same Mₙ, due to the presence of these long, highly entangled chains [22].

Under shear, such as during extrusion or injection molding, polymers exhibit shear-thinning behavior, where viscosity decreases with increasing shear rate. The breadth and shape of the MWD profoundly influence this phenomenon. Research on HDPE has demonstrated that polymers with opposite MWD skews exhibit clear differences in their complex viscosity and shear thinning behavior [21]. The HMW components, which relax slowly, are responsible for the strong shear-thinning effect, as their entanglements cannot re-form quickly under high shear rates. This makes broad MWD polymers easier to process at high speeds, despite their higher zero-shear viscosity [22] [21].

Flow-Induced Crystallization and Advanced Structures

The application of flow fields during processing dramatically alters crystallization. A key morphology formed under flow is the shish-kebab structure, which consists of an oriented central core (shish) overlaid with folded-chain lamellae (kebabs) [18]. The formation of this structure is highly dependent on MWD. HMW components, with their long relaxation times, are more easily oriented and stretched by the flow field to form the central shish. The LMW components then crystallize epitaxially on this oriented backbone to form the kebabs [18]. This demonstrates how MWD can be leveraged to create hierarchical structures that enhance properties like mechanical strength and orientation in the final product.

Diagram: The direct influence of MWD on rheological behavior and flow-induced structure formation.

Experimental Protocol: Tailoring MWD via Flow Reactor Synthesis

Objective: To synthesize a polymer with a precisely tailored MWD using a computer-controlled tubular flow reactor, as an advanced alternative to traditional batch synthesis or blending [19] [20].

Materials:

- Monomer (e.g., lactide for ROP, styrene for anionic polymerization).

- Appropriate initiator and catalyst/activator system for the chosen controlled polymerization.

- Solvent (anhydrous).

- Tubular Flow Reactor System: consisting of:

- Precise syringe or piston pumps.

- Mixing tee.

- Long, coiled tubular reactor (material compatible with reagents, e.g., PTFE or stainless steel).

- Computer-controlled actuation for initiator introduction.

- Collection vessel.

Methodology:

- Reactor Calibration: Determine the relationship between reactor parameters (radius R, length L, flow rate Q) and the resulting "plug" volume of a narrow MWD polymer pulse using established design rules (Plug volume ∝ R²√LQ) derived from Taylor dispersion principles [19] [20]. This is done via tracer experiments.

- MWD Design: Define the target MWD curve. The synthesis protocol translates this curve into a series of sequential flow rates (Q) for the monomer/initiator streams, each producing a narrow dispersity polymer fraction of a specific molecular weight.

- Synthesis Execution: The computer controller executes the predefined flow rate program. As the flow rate changes, the residence time in the reactor changes, resulting in polymers of different molecular weights (Mn ∝ [Monomer]₀/[Initiator]₀ × Conversion). The sequential narrow MWD pulses accumulate in the collection vessel, building up the final, broad MWD profile.

- Validation: Analyze the final polymer product using Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) to verify the synthesized MWD matches the design target.

Expected Outcome: This protocol enables the synthesis of polymers with custom, smooth MWD shapes (e.g., unimodal, bimodal, skewed), moving beyond the limitations of simple blending which can result in multimodality [19] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental study and manipulation of MWD require specific reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions used in the field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MWD Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Purpose | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Chain Transfer Agent (CTA) [23] | Controls molecular weight by terminating growing chains and initiating new ones. | Used in emulsion polymerization to tailor MWD by manipulating the monomer/CTA ratio [23]. |

| Tubular Flow Reactor [19] [20] | Enables precise control over polymerization kinetics (residence time, mixing). | Synthesizing polymers with pre-defined, complex MWD shapes via a "design-to-synthesis" protocol [19] [20]. |

| Metallocene / Coordination Catalysts [21] | Single-site catalysts for producing polymers with narrow MWD; temporal regulation allows MWD shape control. | Living coordination-insertion polymerization of ethylene to study the impact of MWD skew on physical properties [21]. |

| Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) | The primary analytical tool for directly measuring the MWD of a polymer sample. | Essential for validating synthesis outcomes and characterizing polymer samples for structure-property studies. |

Molecular Weight Distribution is a powerful and intrinsic polymer parameter that directly and mechanistically governs mechanical, thermal, and rheological properties. The interplay between LMW and HMW fractions through phenomena like molecular segregation dictates the formation of complex crystalline morphologies, which in turn define mechanical performance and thermal behavior. The MWD's control over the entanglement network directly determines key rheological properties like viscosity and shear thinning, impacting both processability and the potential for creating advanced oriented structures. For researchers, moving beyond average molecular weight to consider the full distribution is no longer optional but necessary for sophisticated material design. The development of advanced synthetic techniques, such as flow reactor polymerization, now provides the tools to precisely tailor MWD, opening new pathways for engineering polymers with customized, high-performance property profiles tailored for specific applications in drug delivery, materials science, and beyond.

The Critical Role of MWD in Polymer Crystallization and Morphology

Molecular Weight Distribution (MWD) is a fundamental intrinsic property of synthetic polymers, describing the statistical variation of chain lengths within a given material. Unlike small molecules, polymers are not composed of identical chains but contain a mixture of species with different degrees of polymerization. This polydispersity profoundly influences polymer processability, crystalline structure formation, and ultimate material properties [18]. The crystallization behavior of polymers—how ordered structures form from disordered melts or solutions—is particularly sensitive to MWD, as chains of varying lengths possess different mobility, entanglement densities, and thermodynamic driving forces for crystallization [18] [24].

Understanding and controlling MWD effects has emerged as a core challenge in polymer crystallography, with significant implications for designing high-performance materials. Recent advances have shifted from interpreting MWD as a single parameter to recognizing the distinct, cooperative contributions of various molecular weight fractions within the distribution curve [18]. This whitepaper systematically examines the critical role of MWD in polymer crystallization and morphology, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive technical guide to this fundamental relationship.

Fundamental Concepts: MWD and Crystallization Kinetics

Thermodynamic and Kinetic Foundations

Polymer crystallization is driven by a decrease in Gibbs free energy when transitioning from a disordered to an ordered state, occurring below the melting temperature (Tₘ) when ΔG < 0 [24]. This process involves two primary stages: nucleation (formation of stable crystalline embryos) and crystal growth (expansion of these nuclei into larger ordered structures) [24]. The long-chain nature of polymers and their potential entanglements make their crystallization behavior fundamentally different from small molecules [24].

MWD influences both nucleation and growth processes through several interconnected mechanisms:

- Chain Mobility: Low molecular weight (LMW) components possess high chain segment mobility but may lack sufficient length for effective crystallization, while high molecular weight (HMW) components exhibit high entanglement density and slow relaxation kinetics [18].

- Entanglement Effects: Longer chains have increased topological constraints that impede reorganization and folding into crystalline structures [18].

- Transport Barriers: The energy required for a polymer chain to disentangle from the melt and be reeled into the crystal growth front creates an additional molecular weight-dependent barrier [18].

Quantitative Crystallization Kinetics Models

Several mathematical models describe polymer crystallization kinetics, with the Avrami and Hoffman-Lauritzen theories being most prominent:

Avrami Equation: Describes overall crystallization kinetics including nucleation and growth: [ Xt = 1 - \exp(-kt^n) ] where (Xt) represents relative crystallinity at time (t), (k) is the crystallization rate constant, and (n) is the Avrami exponent related to nucleation type and growth dimensionality [24].

Hoffman-Lauritzen Theory: Focuses on secondary nucleation and crystal growth kinetics, describing temperature dependence of crystal growth rate ((G)): [ G = G0 \exp\left(-\frac{U^*}{R(T-T∞)}\right) \exp\left(-\frac{Kg}{T\Delta Tf}\right) ] where (U^*) represents activation energy for polymer diffusion, (K_g) is the nucleation parameter related to surface free energies, and (f) is a correction factor [24].

Table 1: Key Parameters in Polymer Crystallization Models

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | MWD Dependence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avrami Exponent | (n) | Related to nucleation mechanism and growth dimensionality | Affected by relative crystallization rates of different MW components |

| Crystallization Rate Constant | (k) | Overall kinetics parameter | Determined by cooperative effects across MWD |

| Growth Rate | (G) | Crystal growth rate | Varies across MWD; LMW fractions typically grow faster |

| Nucleation Activation Barrier | (K_g) | Energy barrier for secondary nucleation | MW-dependent due to chain folding requirements |

Experimental Evidence: MWD Shape and Crystallization Behavior

Unimodal vs. Bimodal MWD Systems

The shape of the MWD curve—not just its breadth—significantly impacts crystallization behavior. Systematic studies using well-defined linear unimodal and bimodal polyethylenes (PEs) with molecular weights ranging from 300-1200 kg/mol reveal profound differences [25]. At the same weight-average molecular weight ((M_w)), PEs with bimodal MWD exhibit:

- Faster nucleation rates at low isothermal crystallization temperatures

- Enhanced crystallization rates

- Smaller lamellar width

- Higher crystallization enthalpy in non-isothermal experiments [25]

The mechanism behind these differences suggests that MWD shapes primarily affect the small-scale nucleation process without altering the large-scale growth process, enabling manipulation of crystallization kinetics without changing chemical composition, chain structure, or average molecular weight [25].

Molecular Segregation and Spatial Distribution

A fundamental phenomenon in polydisperse polymers is molecular segregation—the separation of molecular weight components during crystallization [18]. This segregation manifests as the spatial distribution of MW components into distinct fractions, forming the basis of crystallization fractionation techniques [18].

Richards demonstrated that HMW fractions of branched polyethylene crystallize preferentially at elevated temperatures in solutions [18]. Subsequent studies have established that during isothermal crystallization from the melt under high temperature and pressure, only sufficiently long polymer chains can achieve the requisite number of chain folds to attain stable nucleus size at the crystal growth front [18].

This molecular segregation profoundly influences developing crystalline structures. In blends of different poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) fractions, partial segregation occurs during co-crystallization, resulting in crystalline textures comprising thin-lamellar dendrites in the interior surrounded by thicker lamellae at the periphery [18]. Research suggests HMW components (e.g., 35k-PEO) nucleate first, forming lamellae with non-integer fold chains, while crystal edges develop extended-chain lamellae from LMW components (e.g., 5k-PEO) [18]. This creates a spatial MW distribution yielding composite crystalline textures with distinct lamellar structures and thicknesses in different regions.

Figure 1: Molecular Segregation During Crystallization

Quantitative Data on MWD Effects

Table 2: Experimental Crystallization Data for Different MWD Shapes

| MWD Type | Weight-Average Molecular Weight (Mₐ) | Nucleation Rate | Crystallization Rate | Lamellar Width | Crystallization Enthalpy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unimodal PE | 300-1200 kg/mol | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| Bimodal PE | 300-1200 kg/mol | Faster | Faster | Smaller | Higher |

| Narrow MWD | Variable | Slower nucleation | More uniform | More consistent | Temperature-dependent |

| Broad MWD | Variable | Faster nucleation | Multi-stage | Wider distribution | Enhanced |

MWD Effects on Crystalline Morphology and Structure

Lamellar Thickness and Crystal Morphology

MWD significantly influences the fundamental building blocks of polymer crystals—lamellae—which consist of folded chain segments with typical thicknesses of 10-20 nm [24]. Lamellar thickness is influenced by crystallization temperature and polymer characteristics, with MWD affecting the fold length preferences of different molecular weight fractions [18] [24].

In polydisperse systems, LMW components can adopt extended-chain configurations within crystals, while HMW components predominantly form folded-chain structures [18]. This diversity in chain folding behavior across the MWD creates a distribution of lamellar thicknesses within a single material, directly impacting mechanical properties, thermal stability, and diffusion characteristics [18].

Spherulitic Superstructures

Spherulites—characteristic spherical structures formed during polymer crystallization—exhibit MWD-dependent morphological features [24]. These radiating aggregates of lamellar crystals range in size from micrometers to millimeters depending on crystallization conditions [24].

MWD affects spherulite development through:

- Nucleation Density: The abundance and distribution of nucleation sites are influenced by the relative concentrations of HMW (high nucleation tendency) and LMW (low nucleation tendency) components.

- Growth Patterns: The radial growth rate of spherulites depends on the cooperative crystallization of different MW fractions.

- Impingement Boundaries: The polygonal boundaries formed when growing spherulites meet are determined by the spatial and temporal development of crystalline regions, which is MWD-dependent.

In systems with broad MWD, composite spherulitic structures can form, where interior and peripheral regions exhibit different lamellar arrangements due to molecular segregation during growth [18].

Polymorphism and Crystal Curvature

MWD can influence the propensity for different crystal polymorphs to form. In poly(L-lactide) (PLLA)/poly(D-lactide) (PDLA) stereocomplexes with equal mass but different MW, distinctive curvature patterns emerge [18]. When HMW PLLA (PLLA-h) is blended with LMW PDLA (PDLA-l), edge-on crystals curve predominantly to the left (Z-shape), while PLLA-l/PDLA-h structures curve predominantly to the right (S-shape) [18]. When PLLA and PDLA components have equivalent MW, edge-on lamellae grow linearly [18].

This curvature phenomenon is attributed to the MW-dependent ratio of chains exiting lamella surfaces without folding. As MW decreases, polymer chains find it progressively more difficult to fold under identical crystallization conditions, ultimately adopting more extended chains within the crystal [18]. The LMW components exhibit higher ratios of chains exiting without folding, governing surface stress on lamellar crystals and resulting in curving and twisting behaviors [18].

Flow-Induced Crystallization and Shish-Kebab Formation

Polymer processing conditions dramatically alter crystalline morphology, with flow fields exerting particularly profound influences [18]. Applied flow perturbs chain conformation, affecting crystallization behavior and driving shear-induced crystallization phenomena [18].

Shish-Kebab Formation Mechanism

Shish-kebab is a frequently observed crystalline morphology under shear fields, consisting of an oriented central fiber core (shish) overlaid with periodic lamellar overgrowths (kebabs) [18] [24]. MWD plays a critical role in shish-kebab formation through distinct分工 of different molecular weight fractions:

- HMW Components: Form the central shish structure through chain extension and alignment in the flow direction [18]. Their high entanglement density and slow relaxation enable maintenance of oriented conformations long enough to nucleate the fibrous core.

- LMW Components: Preferentially form the kebabs through epitaxial growth on the existing shish structure [18]. Their high mobility enables rapid crystallization once nucleated.

Figure 2: Shish-Kebab Formation Under Flow Fields

MWD Optimization for Flow-Induced Crystallization

The effectiveness of flow-induced crystallization depends critically on MWD characteristics. Bimodal distributions containing both HMW and LMW fractions often produce the most developed shish-kebab structures, as they provide both sufficient chain entanglement for shish formation and highly mobile species for kebab growth [18] [25]. This has important implications for industrial processing techniques such as fiber spinning, film extrusion, and injection molding, where flow-induced crystallization determines final product properties [24].

Experimental Methodologies and Characterization Techniques

Measuring Crystallization Kinetics

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): Measures heat flow associated with crystallization, allowing determination of crystallization temperature, enthalpy, and kinetics through both isothermal and non-isothermal studies [24]. Avrami analysis can be performed on isothermal DSC data to extract nucleation and growth parameters [24].

Optical Microscopy: Enables direct observation of crystal growth and morphology development, particularly when equipped with hot stages for temperature control and polarized light for visualizing birefringent spherulitic structures [24].

X-ray Scattering Techniques: Provide information on crystal structure and degree of crystallinity [24]:

- Wide-Angle X-ray Scattering (WAXS): Reveals unit cell structure and crystal perfection

- Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS): Provides insights into lamellar spacing and organization

- Time-resolved Studies: Allow monitoring of crystallization kinetics, especially with synchrotron sources for high-speed measurements

MWD Characterization Methods

Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): Also known as Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC), separates polymer chains by hydrodynamic volume, enabling determination of MWD parameters (Mₙ, Mₚ, Mᵥ, polydispersity index) [26]. Hyphenation with multiple detectors (UV, RI, light scattering) provides complementary information.

SEC-Mass Spectrometry (SEC-MS): Combines separation by size with mass-specific detection, enabling correlation of molecular weight with chemical composition distribution (CCD) and end-group functionality (FTD) [26]. For biodegradable polyesters like PLGA, careful optimization of ionization conditions (e.g., using CsI salts) minimizes fragmentation and enables accurate microstructure characterization [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for MWD-Crystallization Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Well-Defined Polymer Standards | Model systems for isolating MWD effects | Unimodal/bimodal PEs with controlled MWD; narrow dispersity samples for baseline studies |

| Crystallization Solvents | Medium for solution crystallization studies | High purity; appropriate boiling point; chemical compatibility with polymer |

| Nucleating Agents | Modifiers of crystallization kinetics | Talc, sodium benzoate, sorbitol derivatives; particle size and dispersion critical |

| Alkali Metal Salts (e.g., CsI) | Stabilizers for SEC-MS analysis | Minimize fragmentation during analysis of polyesters like PLGA |

| Hot-Stage Microscopy Accessories | In-situ crystallization observation | Temperature control stability ±0.1°C; compatible with polarized light |

| Synchrotron X-ray Sources | Time-resolved crystal structure analysis | High flux enables millisecond resolution for kinetics studies |

Applications and Industrial Implications

Processing-Structure-Property Relationships

Understanding MWD effects on crystallization enables precise control of polymer properties through molecular design and processing optimization:

Mechanical Properties: Crystalline structures determined by MWD influence modulus, strength, and toughness [18]. Broader MWD often produces composite crystalline textures with enhanced mechanical performance.

Thermal Stability: Lamellar thickness distribution affects melting behavior and thermal resistance [18]. Tailored MWD can optimize thermal properties for specific applications.

Electrical Properties: In organic electronics, MWD of polymer additives significantly influences semiconductor crystallization and charge transport [27].

Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Applications

In drug delivery systems using biodegradable polyesters like PLGA, MWD critically determines:

- Crystallization kinetics during microsphere formation

- Degradation profiles through crystalline/amorphous ratios

- Drug release kinetics affected by crystalline morphology

Advanced characterization techniques like SEC-MS enable precise MWD analysis, facilitating development of optimized formulations with predictable release behavior [26].

Organic Electronics

MWD of polymer additives significantly influences semiconductor crystallization and charge transport [27]. For TIPS pentacene-based organic thin-film transistors:

- Low-MW polystyrene (PS < 20k) typically results in smaller, more uniform crystals, enhancing charge transport and interface quality

- Medium-MW PS (20k-250k) balances film stability and crystallinity

- High-MW PS (>250k) promotes larger crystalline domains and better long-range order, though may increase phase separation [27]

Similar principles apply to other organic semiconductors, where MWD optimization helps address dendritic crystal formation, thermal cracks, and grain boundaries that compromise device performance [27].

Emerging Research Directions and AI Applications

Artificial Intelligence in Polymer Crystallization Research

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) are emerging as transformative tools for understanding complex MWD-crystallization relationships [28]. Key applications include:

Predictive Modeling: ML algorithms can predict crystallization behavior and properties from MWD data, identifying patterns that may not be evident through traditional analysis [28].

Experimental Optimization: AI-driven "self-driving laboratories" can iteratively refine synthesis and processing conditions to achieve target crystalline structures [28].

Data Integration: AI enables correlation of MWD parameters with multi-scale structural characteristics, from lamellar-level features to macroscopic properties [28].

Tailored MWD Design for Advanced Materials

Future research directions focus on precise MWD engineering to achieve specific crystalline architectures:

- Synthesizing polymers with programmed MWD shapes for targeted crystallization behavior

- Developing multi-modal distributions that optimize both processing characteristics and end-use properties

- Designing smart MWDs that direct hierarchical structure formation across multiple length scales

Molecular Weight Distribution represents a fundamental parameter governing polymer crystallization and morphology, with profound implications across academic research and industrial applications. Rather than being a mere statistical descriptor, MWD actively directs crystallization processes through molecular segregation, cooperative behavior between different chain lengths, and spatial organization of crystalline architectures. The systematic understanding of MWD effects enables precise control of polymer properties without altering chemical composition, offering powerful strategies for material design in fields ranging from pharmaceutical formulations to organic electronics. As characterization techniques and computational methods continue to advance, the deliberate engineering of MWD will play an increasingly critical role in developing next-generation polymeric materials with tailored structure-property relationships.

Spatial Molecular Segregation and Its Effect on Material Texture

Spatial molecular segregation (SMS) is a fundamental phenomenon in polymer science where molecules of different sizes or chemistries separate into distinct domains within a material. This process is intrinsically governed by the polymer's molecular weight distribution (MWD), a core characteristic of any synthetic polymer system. The resulting texture—the spatial arrangement of these domains—directly dictates critical material properties, including mechanical strength, thermal stability, and transport characteristics [18]. For drug development professionals, understanding and controlling SMS is vital for designing polymer-based drug delivery systems, where the spatial distribution of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and polymer components can determine release kinetics and stability. This guide provides a technical overview of the mechanisms, characterization, and implications of SMS, framing it within the broader context of MWD research.

Theoretical Foundations: Linking MWD to Segregation

In polydisperse polymers, chains of varying lengths do not mix uniformly. During processes like crystallization or solvent evaporation, these chains can separate based on their molecular weight, a process known as molecular segregation [18].

- The Role of Chain Length: The driving forces for segregation stem from the differing behaviors of high molecular weight (HMW) and low molecular weight (LMW) components. HMW chains possess a high entanglement density and slow relaxation dynamics, while LMW components exhibit high chain segment mobility [18]. This dynamic disparity causes each fraction to respond differently to kinetic processes such as crystallization or flow.

- Crystallization as a Fractionation Tool: Molecular segregation is the fundamental mechanism behind crystallization fractionation. A classic manifestation is that polyethylene fractions with narrower MWDs can be collected through crystallization and filtration at different temperatures [18]. During isothermal crystallization from a polydisperse melt, research shows that only sufficiently long polymer chains can achieve the requisite number of chain folds to form a stable nucleus, leading to the segregation of longer chains at the growth front [18].

Experimental Manifestations and Textural Outcomes

SMS driven by MWD leads to a variety of complex and technologically important material textures.

Nested Crystalline Structures

In polymer blends with MWDs, the presence of distinct MW components leads to the formation of different crystalline structures within the same material [18]. For instance, in blends of two poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) fractions, HMW components (e.g., 35k-PEO) nucleate first, forming lamellae with non-integer fold chains. Subsequently, the crystal edges are filled with extended-chain lamellae formed by the LMW component (e.g., 5k-PEO) [18]. This results in a spatial distribution of MW and a composite crystalline texture featuring distinct lamellar structures and thicknesses in the interior and periphery of the crystalline entity [18].

Flow-Induced Textures

The application of flow, such as during polymer processing, exerts a profound influence on crystalline morphology. Shish kebab is a typical crystalline morphology formed under shear fields, comprising an oriented central fiber core (shish) overlaid with perpendicular lamellae (kebab) [18]. The formation of this structure is highly dependent on MWD, as HMW and LMW components play distinct roles in determining the nucleation and growth steps under flow fields [18].

Surface Segregation in Thin Films and Glasses

SMS is not limited to bulk crystallization. In polymer blend thin films, such as those composed of polystyrene (PS) and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), phase separation during spin-coating leads to mesoscale morphologies (e.g., columns, holes, or islands) [29]. Machine learning models have demonstrated that parameters including the molecular weight of the components are critical in predicting the final phase-separated morphology [29]. Furthermore, studies on polymer glasses have revealed that the conformation of surface chains, such as the formation of loops that penetrate into the film interior, can significantly suppress surface mobility through intramolecular dynamic coupling, thereby altering the surface texture and properties [30].

Table 1: Experimentally Observed Textures Resulting from Spatial Molecular Segregation

| Material System | Processing Condition | Resulting Texture | Key Segregating Components |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEO Blends [18] | Isothermal Crystallization | Nested Spherulites: Thin-lamellar dendrites in the interior, surrounded by thicker lamellae at the periphery. | HMW vs. LMW PEO fractions |

| Polyethylene [18] | Shear Flow | Shish-Kebab Structure: Oriented central fiber (shish) with overlaid lamellar crystals (kebab). | HMW (for shish) vs. LMW (for kebab) |

| PS/PMMA Blends [29] | Spin-Coating | Phase-Separated Domains: Columns, holes, or islands morphology in thin films. | PS vs. PMMA polymers |

| P(MMA-sta-PFS) [30] | Surface Segregation & Annealing | Gradient Surface Mobility: Surface loops of varying penetration depths altering local dynamics. | PFS-rich (surface) vs. MMA-rich (bulk) |

Quantitative Characterization of Segregation

Advanced characterization and modeling techniques are essential to quantify the energy landscapes and spatial patterns of SMS.

Energetic Landscapes: Segregation Energy Spectra

In metallic alloys, the concept of segregation energy (E_seg) is used to quantify the tendency of a solute atom to segregate to a defect site like a grain boundary (GB) versus remaining in the bulk [31]. Calculating E_seg for millions of potential sites across a wide range of GBs generates a segregation energy spectrum, which reveals the probability distribution of segregation strengths [31]. This approach, while demonstrated in metals, provides a conceptual framework for understanding segregation in polymeric systems based on thermodynamic driving forces.

Table 2: Key Metrics for Quantifying Molecular Segregation

| Metric | Definition | Experimental/Computational Method | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

Segregation Energy (E_seg) [31] |

Energy difference between a solute at a defect site and in the bulk. | Atomistic simulation (Molecular Statics/Dynamics). | Quantifies the thermodynamic driving force for segregation at a specific site. |

| Segregation Energy Spectrum [31] | Distribution of E_seg values across all possible sites in a microstructure. |

High-throughput simulation & statistical analysis. | Describes the heterogeneity of segregation behavior across an entire material volume. |

| Surface Loss Tangent (tan δ) [30] | Ratio of loss modulus to storage modulus, measured at the surface. | Amplitude Modulation-Frequency Modulation Atomic Force Microscopy (AM-FM AFM). | Probes nanoscale variations in surface mobility and energy dissipation due to segregation. |

Loop Depth (d_loop) [30] |

Average penetration depth of surface polymer chains into the film interior. | Dynamic Monte Carlo (MC) simulations; experimental inference. | Links surface chain conformation to the spatial extent and effect of surface segregation. |

Data-Driven Prediction of Segregation and Morphology

The complexity of SMS necessitates the use of machine learning (ML) for prediction. ML models can use atomic environment descriptors to predict site-specific segregation energies, enabling the population of large-scale structures with segregants without computationally expensive simulations [32]. Similarly, for polymer blend thin films, ML classification models can predict the final phase-separated morphology (e.g., column, hole, or island) based on input parameters such as molecular weight, blend composition, and substrate surface energy, achieving high accuracy [29].

Methodologies for Investigation

A multi-pronged approach combining simulation and experiment is required to fully characterize SMS.

Computational and Modeling Protocols

Protocol 1: Multiscale Molecular Modeling of Amorphous Polymer Structure [33] This protocol generates equilibrated bulk amorphous structures for polymers like poly(propylene oxide) (PPO).

- Coarse-Graining (CG): Map the atomistic polymer chain onto a high-coordination lattice based on its rotational isomeric state (RIS) model.

- Lattice Monte Carlo (MC) Simulation: Perform MC simulations on the CG model to achieve structural relaxation and equilibration of the bulk system. Monitor relaxation via orientation autocorrelation functions and mean square displacement.

- Reverse-Mapping: Transform the equilibrated CG structure back to a fully atomistic model.

- Geometry Optimization and Validation: Conduct energy minimization and molecular dynamics relaxation on the atomistic model. Validate the final structure by comparing simulated properties (e.g., X-ray/neutron scattering intensity, density) with experimental data.

Protocol 2: Machine Learning Prediction of Grain Boundary Segregation [32] This protocol, developed for metallic GBs, is a paradigm for predicting segregation landscapes.

- Descriptor Calculation: For each atom in a structure, calculate a set of rotationally invariant higher-order atomic descriptors (e.g., Strain Functional Descriptors - SFDs) that fingerprint its local environment.

- Training Data Generation: Use molecular statics simulations to compute the segregation energy (

E_seg) for a representative set of atomic sites. - Model Training: Train a machine learning model (e.g., Gradient Boosted Machine) using the atomic descriptors as input features and the calculated

E_segas the target output. - Prediction and Analysis: Use the trained model to rapidly predict

E_segfor all atoms in a large-scale microstructure. Analyze the resulting segregation energy spectrum and spatial distribution.

Experimental Characterization Techniques

Protocol 3: Analyzing Surface Segregation and Dynamics in Polymer Films [30] This protocol investigates how surface molecular architecture affects nanoscale mobility.

- Sample Preparation: Synthesize random copolymers (e.g., P(MMA-sta-PFS)) with varying mole fractions of the low-surface-energy component (PFS). Blend these copolymers into a polymer matrix (e.g., PMMA) and prepare thin films via spin-casting.

- Annealing: Anneal the films above the glass transition temperature (

T_g) to allow for surface segregation of the PFS units, forming chain loops of various penetration depths. - Surface Characterization:

- Use X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and contact angle measurements to confirm surface composition.

- Use atomic force microscopy (AFM) to determine surface topography.

- Surface Dynamics Measurement: Employ amplitude modulation-frequency modulation AFM (AM-FM AFM) to map the surface loss tangent (tan δ), which quantifies local energy dissipation and segmental mobility.

Protocol 4: Protein Microarray Fabrication on Phase-Separated Polymer Blends [34] This protocol leverages SMS for creating bioactive patterns.

- Substrate Patterning: Use microcontact printing to create a patterned self-assembled monolayer (e.g., of APTES) on a silicon wafer.

- Polymer Film Deposition: Deposit a thin film of an immiscible polymer blend (e.g., PMMA and PtBMA) onto the patterned substrate using spin-coating or horizontal-dip coating.