Molecular Dynamics Simulations for Polymers: From Fundamental Principles to Advanced Applications in Drug Delivery and Materials Science

This comprehensive review explores the transformative role of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in polymer science, with particular emphasis on applications in drug delivery and biomedical research.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations for Polymers: From Fundamental Principles to Advanced Applications in Drug Delivery and Materials Science

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the transformative role of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in polymer science, with particular emphasis on applications in drug delivery and biomedical research. It covers fundamental principles of MD methodology, detailed applications in optimizing polymer-based drug carriers and materials, strategies for overcoming computational challenges, and protocols for validating simulations against experimental data. By synthesizing recent advances and practical implementation guidelines, this article provides researchers and drug development professionals with an essential resource for leveraging MD simulations to accelerate the design of novel polymeric systems for therapeutic applications.

Fundamental Principles: Understanding Molecular Dynamics and Polymer Physics at the Atomic Scale

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation serves as a foundational computational tool in polymer science, enabling researchers to investigate polymer behavior at the atomic and molecular levels. The core theoretical framework of MD is firmly rooted in Newtonian mechanics, which governs the motion of atoms and molecules within simulated polymer systems. By applying this physical framework through computational algorithms, scientists can predict intricate polymer properties and behaviors that are often challenging to observe experimentally. This approach has become particularly valuable in pharmaceutical and materials research, where understanding molecular-scale interactions drives the development of new polymeric drug delivery systems, biomaterials, and functional polymers with tailored characteristics. The integration of MD simulations allows researchers to bridge the gap between theoretical predictions and experimental observations, providing unprecedented insights into polymer dynamics and enabling more efficient design of polymer-based solutions for medical and industrial applications.

Theoretical Foundations

Newtonian Mechanics in Molecular Dynamics

The molecular dynamics approach to polymer simulation is fundamentally built upon Newton's second law of motion, which provides the mathematical foundation for calculating atomic trajectories over time. In MD simulations, this principle is applied at the atomic scale, where the force acting on each atom is derived from the potential energy of the system, and mass is the atomic mass. The resulting acceleration is then used to compute atomic velocities and positions through numerical integration over discrete time steps [1].

The mathematical representation of this relationship can be expressed as:

Fi = m~i~ai = m~i~(d²ri/dt²) = -∇~i~E~pot~

Where Fi is the force exerted on atom i, m~i~ is its mass, ai is its acceleration, ri is its position, and E~pot~ is the potential energy of the system [1]. This equation demonstrates how the spatial gradient of the potential energy function determines the forces that drive atomic motion in polymer systems.

The selection of an appropriate time step represents a critical consideration in MD simulations, as it directly impacts both computational efficiency and numerical stability. Excessively large time steps can lead to system instability or simulation failure, while overly small steps significantly increase computational costs. Typical MD simulations employ time steps ranging from 1 to 2 femtoseconds (fs), though shorter intervals may be necessary for capturing specific rapid molecular processes [1].

Force Fields: Mathematical Representation of Interatomic Interactions

Force fields provide the mathematical framework that describes how atoms in a polymer system interact with each other. These computational models comprise analytical functions and parameters that collectively define the potential energy surface of a molecular system. In polymer simulations, force fields encapsulate the complex interplay of bonded and non-bonded interactions that govern polymer conformation, dynamics, and thermodynamics [1].

The total potential energy in a typical classical force field is decomposed into multiple contributions:

E~total~ = E~bond~ + E~angle~ + E~torsion~ + E~non-bonded~

Where E~bond~ represents energy associated with chemical bond stretching, E~angle~ accounts for angle bending between three connected atoms, E~torsion~ describes rotational barriers around chemical bonds, and E~non-bonded~ encompasses van der Waals and electrostatic interactions [1].

Each component employs specific mathematical functions to capture the physics of molecular interactions:

- Bond stretching is typically modeled using harmonic potentials: E~bond~ = ∑~bonds~ k~b~(r - r~0~)²

- Angle bending also follows harmonic approximations: E~angle~ = ∑~angles~ k~θ~(θ - θ~0~)²

- Torsional rotations employ periodic functions: E~torsion~ = ∑~dihedrals~ k~φ~[1 + cos(nφ - δ)]

- Non-bonded interactions combine Lennard-Jones potential for van der Waals forces: E~LJ~ = 4ε[(σ/r)¹² - (σ/r)⁶] and Coulomb's law for electrostatic interactions: E~elec~ = (q~i~q~j~)/(4πε~0~r) [1]

Table 1: Fundamental Components of Classical Force Fields in Polymer Simulations

| Energy Component | Mathematical Formulation | Physical Interaction | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | E = k~b~(r - r~0~)² | Vibrational motion between bonded atoms | k~b~ (force constant), r~0~ (equilibrium distance) |

| Angle Bending | E = k~θ~(θ - θ~0~)² | Angle vibration between three connected atoms | k~θ~ (angle force constant), θ~0~ (equilibrium angle) |

| Torsional Rotation | E = k~φ~[1 + cos(nφ - δ)] | Rotation around chemical bonds | k~φ~ (barrier height), n (periodicity), δ (phase angle) |

| van der Waals | E = 4ε[(σ/r)¹² - (σ/r)⁶] | Short-range attraction and repulsion | ε (well depth), σ (collision diameter) |

| Electrostatic | E = (q~i~q~j~)/(4πε~0~r) | Interaction between charged atoms | q~i~, q~j~ (atomic charges), ε~0~ (permittivity) |

Advanced Force Field Methodologies

Machine Learning Force Fields

The emergence of machine learning force fields represents a paradigm shift in polymer simulation methodologies. Unlike classical force fields with fixed analytical forms, MLFFs learn the relationship between atomic configurations and potential energies directly from quantum-chemical reference data [2]. This approach addresses fundamental limitations of traditional force fields, particularly their limited transferability across diverse chemical environments and inability to accurately model bond-breaking and formation processes [2].

MLFF architectures such as Vivace employ local SE(3)-equivariant graph neural networks (GNNs) engineered for the computational speed and accuracy required for large-scale atomistic polymer simulations [2]. These models capture complex atomic interactions through innovative computational approaches:

- Lightweight tensor products that efficiently capture crucial three-body interactions without expensive learnable parameters

- Multi-cutoff strategies that balance accuracy and efficiency by handling short-range and mid-range interactions separately

- Efficient inner-product operations that replace computationally expensive equivariant operations for weaker interactions [2]

The development of specialized training datasets like PolyData has been instrumental in advancing MLFF applications for polymers. This collection includes structurally perturbed polymer chains at various densities (PolyPack), single polymer chains in varying unit cell sizes (PolyDiss), and polymer fragments in vacuum (PolyCrop), providing comprehensive coverage of the complex intra- and intermolecular interactions in polymeric systems [2].

Classical Force Fields in Polymer Research

Despite advances in MLFFs, classical force fields remain widely used in polymer simulations due to their computational efficiency and well-established parameterization for many polymer systems. These force fields describe interatomic interactions through parameterized energy terms designed to capture both covalent and non-covalent interactions [2]. The parametrization process typically involves fitting to a combination of computational and experimental data, making them particularly valuable for simulating established polymer systems with abundant reference data [2].

However, classical force fields face significant challenges in polymer modeling, including:

- Limited transferability beyond specific chemical environments for which they were optimized

- Inability to model chemical reactions due to fixed bonding topologies

- System-specific parameterization requirements that hinder application to novel polymer systems [2]

These limitations have motivated the development of specialized force fields for specific polymer classes and the ongoing refinement of parameters for improved accuracy across diverse polymer systems.

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

Protocol for Density Prediction Using MLFFs

Accurately predicting polymer densities represents a fundamental application of molecular dynamics simulations in polymer research. The following protocol outlines the key steps for obtaining reliable density predictions using machine learning force fields:

System Preparation

- Construct polymer chains with appropriate degrees of polymerization (typically 10-50 repeat units)

- Assign initial chain configurations using random walk or pre-equilibrated structures

- Apply periodic boundary conditions to simulate bulk conditions [2]

Simulation Parameters

- Employ integration time steps of 1-2 femtoseconds for numerical stability

- Implement Nosé-Hoover or Berendsen thermostats to maintain constant temperature

- Use Parrinello-Rahman or Berendsen barostats for pressure control

- Set simulation boxes with initial dimensions corresponding to approximate experimental density [2]

Equilibration Procedure

- Conduct energy minimization using steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithms

- Perform gradual heating from 0K to target temperature over 100-500ps

- Execute isothermal-isobaric (NPT) equilibration for 1-10ns until density stabilizes

- Monitor convergence through potential energy, temperature, and density profiles [2]

Production Run and Analysis

- Extend NPT simulation for 5-20ns to collect statistical data

- Calculate average density from trajectory data, discarding initial equilibration period

- Estimate statistical uncertainty using block averaging or bootstrap methods [2]

Protocol for Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) Determination

The glass transition temperature (Tg) is a critical property governing polymer application. MD simulations can capture this second-order phase transition through the following protocol:

System Preparation and Equilibration

- Generate amorphous polymer cells with multiple chains (typically 5-20 chains)

- Employ simulated annealing from high temperature (e.g., 600K) to room temperature

- Verify amorphous structure through radial distribution functions [2]

Temperature Cycling Procedure

- Set up a series of simulations across a temperature range (e.g., 100-500K)

- At each temperature, perform sequential NPT equilibration (1-5ns) and production (2-10ns)

- Utilize temperature intervals of 10-25K, with finer spacing near expected Tg [2]

Property Monitoring and Analysis

- Track specific volume (or density) as a function of temperature

- Calculate potential energy, mean squared displacement, and other relevant properties

- Identify Tg as the intersection point of linear fits to the glassy and rubbery states [2]

Validation and Error Assessment

- Compare with experimental Tg values when available

- Perform multiple independent runs to assess statistical uncertainty

- Evaluate system size effects through simulations with different chain counts and lengths [2]

Benchmarking and Validation Frameworks

Robust benchmarking is essential for validating force field performance in polymer simulations. The PolyArena benchmark provides a standardized framework for evaluating MLFFs on experimentally measured polymer properties, including densities and glass transition temperatures for 130 polymers with diverse chemical compositions [2].

Table 2: PolyArena Benchmark Scope and Diversity

| Characteristic | Range/Coverage | Polymer Families Included | Elemental Composition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Polymers | 130 | Polyolefins, polyesters, polyethers, polyacrylates, polycarbonates, polyimides, polystyrenes, siloxanes, perfluorinated polymers | H, C, N, O, F, Si, S, Cl |

| Molecular Weight Range | 28-593 g/mol | AB-alternating copolymers, complex architectures | - |

| Density Range | 0.8-2.0 g/cm³ | - | - |

| Glass Transition Range | 152-672 K | - | - |

| Functional Groups | Alkyl chains, nitriles, carboxylic acid derivatives, halogens | - | - |

Key benchmarking metrics include:

- Density prediction accuracy: Mean absolute error (MAE) compared to experimental values

- Glass transition temperature accuracy: MAE and correlation with experimental Tg

- Computational efficiency: Simulation time per nanosecond for comparable systems

- Transferability assessment: Performance on polymer chemistries not included in training [2]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Polymer Simulations

| Tool/Dataset | Type | Function in Polymer Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vivace MLFF | Machine Learning Force Field | Accurately predicts polymer properties using local SE(3)-equivariant GNN | Density prediction, phase transition modeling [2] |

| PolyData | Training Dataset | Provides quantum-chemical reference data for polymer MLFF development | Training transferable force fields for diverse polymers [2] |

| PolyArena | Benchmark | Evaluates MLFF performance on experimental polymer properties | Comparing force field accuracy across 130 polymers [2] |

| Allegro | ML Architecture | Base for local MLFF architectures requiring efficient multi-GPU calculations | Large-scale polymer simulations [2] |

| OpenMM | MD Software Package | Performs molecular dynamics simulations with hardware acceleration | DNA and polymer dynamics simulations [3] |

| PolyPack | Structural Dataset | Contains structurally-perturbed polymer chains at various densities | Probing strong intramolecular interactions [2] |

| PolyDiss | Structural Dataset | Consists of single polymer chains in unit cells of varying sizes | Studying weak intermolecular interactions [2] |

| Lennard-Jones Potential | Potential Function | Models van der Waals interactions in classical force fields | Simulating non-bonded interactions in polymers [1] |

| Coulomb Potential | Potential Function | Describes electrostatic interactions between charged atoms | Modeling ionic polymers or polar functional groups [1] |

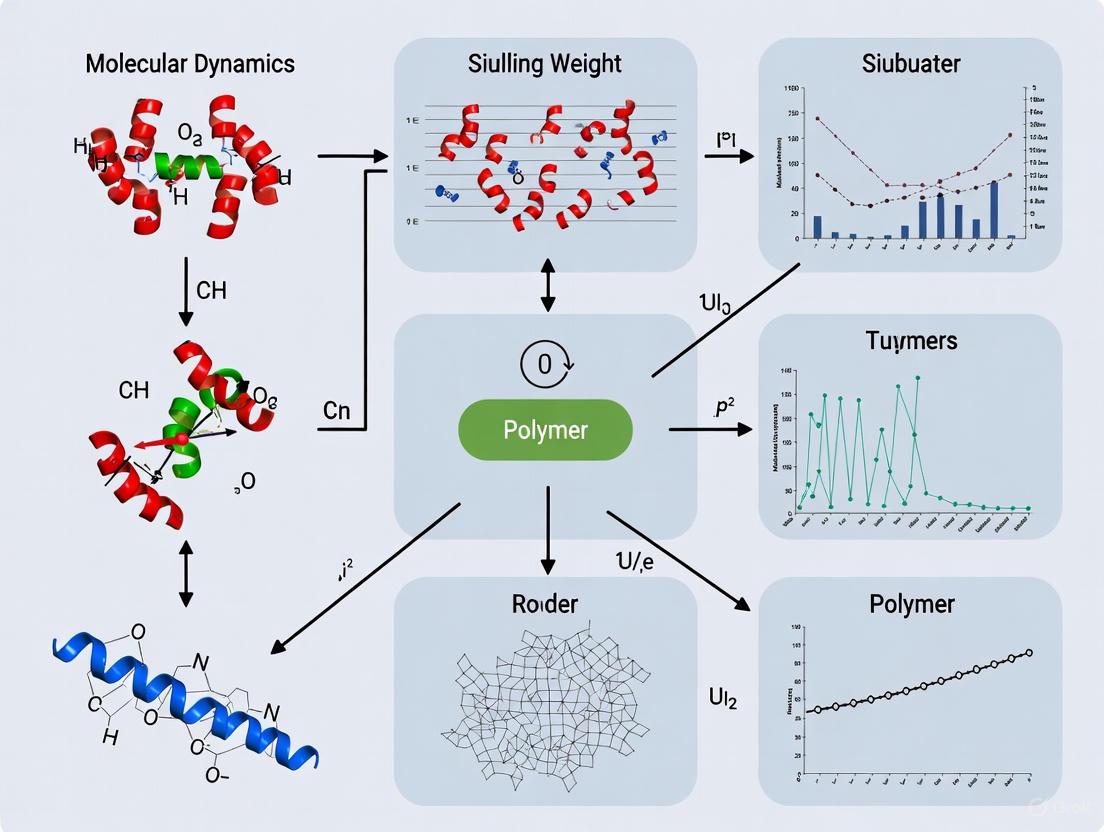

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Comprehensive Workflow for Polymer Molecular Dynamics Simulations

The theoretical framework of Newtonian mechanics, implemented through classical and machine learning force fields, provides a powerful foundation for molecular dynamics simulations of polymer systems. While classical force fields remain valuable for many applications due to their computational efficiency, MLFFs offer promising advances in accuracy and transferability for complex polymer systems. The development of standardized benchmarks like PolyArena and specialized datasets like PolyData is accelerating progress in this field, enabling more reliable predictions of polymer properties directly from first principles. As these computational methodologies continue to evolve, they will increasingly serve as essential tools for researchers and drug development professionals working to design next-generation polymeric materials with tailored properties for specific pharmaceutical and medical applications.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of polymers, accurately modeling the interplay of atomic and molecular forces is paramount for predicting macroscopic material properties. These essential interaction models—comprising bonding forces, van der Waals interactions, and electrostatics—form the fundamental computational framework that governs the dynamic behavior of polymer chains at the atomic scale. The fidelity of these force models directly determines the reliability of simulations in predicting experimentally verifiable phenomena, from glass transition temperatures to bulk rheological properties. For polymer researchers and drug development professionals, mastering these interaction models enables the in silico design of novel polymeric materials with tailored characteristics, significantly accelerating the development cycle for applications ranging from enhanced oil recovery to pharmaceutical formulations and advanced nanomaterials.

The complex, multi-scale nature of polymers presents unique modeling challenges, as their behavior arises from diverse local monomer interactions and long-range inter-chain forces that collectively determine bulk properties. Conventional force fields describe these interatomic interactions through parameterized energy terms for covalent and non-covalent interactions, but they often lack the transferability required for the vast chemical space of synthetic polymers. Emerging machine learning force fields (MLFFs) trained on quantum-chemical data now offer promising alternatives by overcoming fundamental limitations of classical force fields, enabling more accurate predictions of polymer densities and phase transitions without extensive parameterization.

Core Interaction Models: Theoretical Framework and Parameters

Bonding Interactions: Covalent Force Constraints

Bonding forces maintain the structural integrity of polymer chains through potential energy functions that model covalent chemical bonds. These interactions are characterized by their high energy constants, which constrain atomic movements to physically realistic vibrations and deformations. The following table summarizes the primary bonding interactions and their mathematical representations:

Table 1: Bonding Interaction Potentials in Polymer Simulations

| Interaction Type | Functional Form | Key Parameters | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | $E{bond} = \frac{1}{2}kb(r - r_0)^2$ | $kb$: force constant, $r0$: equilibrium bond length | Harmonic potential modeling vibration between directly bonded atoms |

| Angle Bending | $E{angle} = \frac{1}{2}kθ(θ - θ_0)^2$ | $kθ$: angle force constant, $θ0$: equilibrium angle | Energy cost of deviating from preferred bond angles |

| Dihedral/Torsional | $E{dihedral} = kφ[1 + cos(nφ - δ)]$ | $k_φ$: barrier height, $n$: periodicity, $δ$: phase angle | Energy for rotation around central bonds in four-atom sequences |

| Improper Dihedral | $E{improper} = \frac{1}{2}kψ(ψ - ψ_0)^2$ | $kψ$: force constant, $ψ0$: equilibrium angle | Maintains planar geometry and chirality at stereocenters |

In polymer simulations, these bonding potentials collectively determine chain flexibility, persistence length, and conformational entropy. The accurate parameterization of these terms is particularly crucial for capturing polymer-specific phenomena such as glass transitions, where the balance between constrained local motions and large-scale chain dynamics dictates the transition temperature. Recent advances in machine learning force fields demonstrate that improved representations of bonding interactions can yield more accurate predictions of polymer densities and thermal properties compared to established classical force fields.

Non-Bonded Interactions: Van der Waals and Electrostatics

Non-bonded interactions operate between atoms that are not directly connected by covalent bonds and play a decisive role in determining polymer-polymer, polymer-solvent, and polymer-surface interactions. These forces govern phase separation, adhesion, solubility, and mechanical properties in polymeric materials.

Table 2: Non-Bonded Interaction Potentials in Polymer Simulations

| Interaction Type | Functional Form | Key Parameters | Cut-off Range | Physical Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Van der Waals (Lennard-Jones) | $E_{LJ} = 4ε[(σ/r)^{12} - (σ/r)^6]$ | $ε$: potential well depth, $σ$: finite distance at which E=0 | 1-1.5 nm | Combined effect of short-range repulsion and longer-range dispersion attraction |

| Electrostatics (Coulomb) | $E{elec} = \frac{1}{4πϵ0}\frac{qiqj}{ϵr}$ | $qi$, $qj$: partial atomic charges, $ϵ$: dielectric constant | Long-range (requires PME) | Interaction between permanently charged or partially charged atoms |

| Solvation Effects (Implicit) | $E{GB} = -\frac{1}{2}(1/ϵ{in} - 1/ϵ{out})\frac{qiqj}{f{GB}}$ | $ϵ{in}$, $ϵ{out}$: dielectric constants, $f_{GB}$: screening function | N/A | Approximates solvent effects without explicit water molecules |

Van der Waals interactions, typically modeled using the Lennard-Jones potential, are particularly important for describing the cohesive energy density of polymer melts and the interfacial behavior in multiphase systems. The $r^{-12}$ term represents Pauli repulsion at short distances due to overlapping electron orbitals, while the $r^{-6}$ term describes the attractive London dispersion forces arising from correlated electron fluctuations. Electrostatic interactions in polymers originate from permanent dipoles in functional groups (e.g., carbonyl, hydroxyl, amine) and ionic species in polyelectrolytes. These long-range forces significantly influence chain conformation through intra-chain and inter-chain interactions, especially in aqueous environments where dielectric screening effects must be properly accounted for using methods like Particle Mesh Ewald (PME).

Experimental Protocols: Implementation in Polymer Simulations

Protocol 1: MD Simulation of Polymer Melt Dynamics

Objective: Characterize the bulk behavior and thermodynamic properties of a homogeneous polymer melt using classical force fields.

Materials and Reagents:

- Software: GROMACS 2022.3+ or equivalent MD package

- Force Field: OPLS-AA, CHARMM, or GAFF with polymer-specific parameters

- Initial Structure: Polymer chain with defined tacticity and molecular weight

- Computational Resources: Multi-core CPU cluster or GPU-accelerated workstations

Procedure:

- System Setup:

- Build polymer chain with 20-50 repeat units using chemical sketching software

- Replicate chains in simulation box to achieve target density (e.g., 0.8-1.2 g/cm³ based on experimental values)

- Apply periodic boundary conditions to all dimensions

Energy Minimization:

- Employ steepest descent algorithm for 50,000 steps or until energy convergence

- Set maximum force threshold of <1000 kJ/mol/nm to eliminate steric clashes

Equilibration Phases:

- NVT Ensemble: Run for 5 ns at 300 K using velocity-rescaling thermostat

- NPT Ensemble: Run for 16 ns at 1 bar pressure using Berendsen barostat

- Monitor potential energy, temperature, pressure, and density for stability

Production Run:

- Extend simulation to 50-100 ns using Nose-Hoover thermostat and Parrinello-Rahman barostat

- Use integration time step of 2 fs with LINCS constraint algorithm

- Configure trajectory saving every 10-100 ps for subsequent analysis

Analysis:

- Calculate mean squared displacement for diffusion coefficients

- Compute radial distribution functions for local ordering

- Determine polymer density and compare with experimental values

- Analyze end-to-end distance and radius of gyration for chain conformation

Validation: Compare simulated density with experimental measurements for the target polymer. For polypropylene at 300K, expected density is ~0.855 g/cm³ with OPLS-AA force field.

Protocol 2: MLFF Simulation for Glass Transition Temperature Prediction

Objective: Predict the glass transition temperature (Tg) of an amorphous polymer using machine learning force fields.

Materials and Reagents:

- Software: Vivace MLFF or equivalent machine learning potential

- Training Data: PolyData dataset containing quantum-chemical reference structures

- Initial Structures: Amorphous polymer cells with varying chain lengths

- Computational Resources: High-performance computing cluster with GPU acceleration

Procedure:

- System Preparation:

- Generate amorphous polymer cells using Monte Carlo packing algorithms

- Create systems with 10-20 polymer chains of 10-50 repeat units each

- Initialize at low density (0.6-0.8 g/cm³) to facilitate equilibration

Force Field Training:

- Train Vivace MLFF on PolyData dataset using active learning strategy

- Validate against quantum-chemical references for energies and forces

- Assess transferability across chemical space of target polymer

Thermal Ramp Simulation:

- Equilibrate system at 600K for 5 ns to erase thermal history

- Perform stepwise cooling from 600K to 100K in 25K increments

- Run 2-5 ns simulation at each temperature with NPT ensemble

- Use pressure coupling to 1 bar with Parrinello-Rahman barostat

Density Analysis:

- Calculate average density during final 1 ns at each temperature

- Plot density versus temperature curve

- Identify Tg as the intersection point of linear fits to rubbery and glassy states

Validation:

- Compare predicted Tg with experimental differential scanning calorimetry data

- Assess accuracy against established force fields (OPLS-AA, CHARMM)

- Calculate mean absolute error across polymer series

Expected Outcomes: Vivace MLFF has demonstrated the ability to capture second-order phase transitions, enabling prediction of polymer glass transition temperatures with improved accuracy over classical force fields. The methodology successfully reproduces the characteristic change in slope of the density-temperature curve at Tg.

Visualization of Workflows and Methodologies

Polymer Simulation Workflow

ML Force Field Development Pipeline

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools and Datasets

Table 3: Essential Computational Resources for Polymer MD Simulations

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Frameworks | Primary Function | Application in Polymer Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Engines | GROMACS, LAMMPS, OpenMM, HOOMD-blue | Perform high-performance molecular dynamics calculations | Simulation of polymer melts, solutions, and interfaces at atomic scale |

| Force Fields | OPLS-AA, CHARMM, GAFF, CGenFF | Provide parameters for bonding and non-bonded interactions | Prediction of thermodynamic and mechanical properties of polymers |

| Machine Learning Force Fields | Vivace (SimPoly), Allegro, ANI-2x | Learn potential energy surfaces from quantum data | Accurate property prediction (density, Tg) with quantum accuracy |

| Quantum Chemical Datasets | PolyData, QDπ, SPICE, ANI | Provide reference data for MLFF training | Training and validation of machine learning potentials for polymers |

| Analysis Tools | MDAnalysis, MDTraj, VMD | Process and visualize simulation trajectories | Calculation of polymer characteristics (Rg, MSD, end-to-end distance) |

| Specialized Polymer Tools | PyPoly, Polydisperse Systems Generator | Create initial configurations for polymer systems | Preparation of amorphous cells with controlled molecular weight distributions |

The Vivace MLFF architecture represents a significant advancement for polymer simulations, employing a local SE(3)-equivariant graph neural network engineered for the speed and accuracy required for large-scale atomistic polymer simulations. Its multi-cutoff strategy balances accuracy and efficiency by handling weaker mid-range interactions with invariant operations up to 6.5 Å, while reserving computationally expensive equivariant operations for short-range interactions below 3.8 Å. For classical simulations, the OPLS-AA force field has demonstrated particular effectiveness for polymer systems, with parameters optimized to reproduce experimental densities and structural properties across diverse polymer chemistries.

The accurate representation of bonding forces, van der Waals interactions, and electrostatics in molecular dynamics simulations forms the cornerstone of predictive polymer modeling. As research advances, the integration of machine learning force fields with traditional molecular dynamics promises to overcome the transferability limitations of classical force fields while maintaining computational efficiency. The development of specialized datasets like PolyData and QDπ, coupled with active learning strategies for efficient sampling of chemical space, enables increasingly accurate predictions of experimentally relevant polymer properties directly from first principles.

For researchers investigating polymer behavior across diverse applications—from drug delivery systems to enhanced oil recovery and advanced materials—these computational protocols provide robust frameworks for connecting molecular-level interactions to macroscopic properties. The continued refinement of these essential interaction models will further establish molecular dynamics as an indispensable tool for the rational design of next-generation polymeric materials, ultimately reducing development timelines and experimental costs through reliable in silico prediction.

Within the broader scope of a thesis on molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for polymers research, the precise selection of simulation parameters is not merely a procedural step but a cornerstone of obtaining physically meaningful and reliable results. Molecular dynamics serves as a computational microscope, enabling researchers to observe atomic-scale phenomena that are critical to understanding polymer behavior, from glass transition temperatures to mechanical properties and transport mechanisms [4]. The accuracy of these observations, however, is fundamentally governed by the choices made in setting up the simulation. Key parameters such as time step, which determines the discrete intervals for solving equations of motion; temperature, which dictates the kinetic energy and thermodynamic state of the system; and pressure, which controls the density and stress conditions, collectively define the stability, accuracy, and physical fidelity of the simulation [1] [4]. For researchers and scientists in both materials science and drug development, where in silico predictions can guide expensive experimental campaigns, a rigorous protocol for parameter selection is indispensable. This application note provides detailed methodologies and structured data to standardize this critical aspect of polymer simulation.

Theoretical Foundations

The fundamental principle of MD simulation is the numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion for a system of atoms. The force acting on each atom, derived from the negative gradient of the potential energy function (or force field), determines its acceleration [4]. The choice of time step is critical in this integration process. An excessively large time step can lead to instability and inaccurate dynamics, as the simulation may fail to capture the fastest vibrational modes, while an excessively small one needlessly increases computational cost [1]. Typical MD simulations use time steps on the order of femtoseconds (10⁻¹⁵ seconds) to accurately track atomic movements [4].

Temperature and pressure are state variables that are controlled via thermostats and barostats, respectively. These algorithms ensure the simulation samples the appropriate thermodynamic ensemble (e.g., NVT for constant number of particles, volume, and temperature; or NPT for constant number of particles, pressure, and temperature). For polymer systems, maintaining the correct temperature is vital for simulating properties like the glass transition, while pressure control is essential for obtaining realistic densities [2]. The selection of thermostat and barostat algorithms, and their associated parameters, directly influences the quality of the generated trajectory and the derived material properties.

Parameter Selection and Optimization

Time Step Selection

The time step (Δt) is the most fundamental parameter governing the numerical integration of the equations of motion. Its selection is a balance between computational efficiency and the accurate representation of the system's highest frequency motions.

Table 1: Guidelines for Time Step Selection in Polymer MD Simulations

| System Characteristics | Recommended Time Step (fs) | Rationale and Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Polymer Systems (C-H, C-C bonds) | 1.0 - 2.0 | Balances efficiency with stability for common organic polymers; can capture C-C bond vibrations [1] [4]. |

| Systems with Light Atoms (e.g., explicit H-bonding) | 0.5 - 1.0 | Necessary to capture the fast vibrations of hydrogen atoms, preventing energy drift and instability [4]. |

| Coarse-Grained Systems | > 2.0 | Softer potentials and eliminated fast degrees of freedom allow for larger effective time steps. |

| Use of Constraint Algorithms (e.g., SHAKE, LINCS) | 2.0 - 4.0 | These algorithms freeze the fastest bond vibrations (e.g., C-H), permitting a larger time step while conserving energy. |

The core principle is that the time step must be significantly smaller than the period of the fastest vibration in the system. The Verlet algorithm and its variants, such as the leap-frog algorithm, are commonly used for time integration due to their favorable numerical stability and energy conservation properties over long simulations [4].

Temperature Control

Temperature in an MD simulation is proportional to the average kinetic energy of the atoms. Thermostats maintain the desired temperature by scaling atom velocities or acting as a heat bath.

Table 2: Common Thermostat Algorithms and Their Parameters

| Thermostat Algorithm | Key Control Parameters | Best Use Cases in Polymer Research |

|---|---|---|

| Berendsen | T_target (K), tau_t (coupling time constant) |

Rapid equilibration; provides weak coupling to a heat bath but does not generate a rigorous canonical ensemble. |

| Nosé-Hoover | T_target (K), Q (mass of the thermostat) |

Production runs; generates a correct NVT ensemble, suitable for calculating equilibrium properties [5]. |

| Langevin | T_target (K), gamma (friction coefficient, ps⁻¹) |

Systems with implicit solvent; adds stochastic and frictional forces, useful for damping and thermalization. |

The tau_t parameter (time constant) determines how tightly the thermostat couples the system to the desired temperature. A too-strong coupling (very small tau_t) can artificially suppress temperature fluctuations, while a too-weak coupling (very large tau_t) may result in poor temperature control.

Pressure Control

Pressure is a function of the virial stress and kinetic energy within the simulation cell. Barostats adjust the simulation cell volume to maintain a constant pressure.

Table 3: Common Barostat Algorithms and Their Parameters

| Barostat Algorithm | Key Control Parameters | Best Use Cases in Polymer Research |

|---|---|---|

| Berendsen | P_target (bar), tau_p (coupling time constant), compressibility (bar⁻¹) |

Rapid equilibration of density; scales cell coordinates for efficient relaxation but does not produce a rigorous isobaric ensemble. |

| Parrinello-Rahman | P_target (bar), tau_p (coupling time), compressibility (bar⁻¹) |

Production runs; generates a correct NPT ensemble and allows for shape fluctuations of the simulation cell, important for anisotropic systems. |

The compressibility parameter, an estimate of the system's physical compressibility, is required by many barostats to calculate the correct volume scaling. An inaccurate value can lead to unstable oscillations in the cell volume.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: System Equilibration for an Amorphous Polymer

Objective: Generate a well-equilibrated, relaxed configuration of an amorphous polymer (e.g., polystyrene) at a specific temperature and pressure for subsequent production simulation.

Workflow:

Steps:

- Initialization: Build a polymer system using tools like

Packmolor built-in builders in software like GROMACS or LAMMPS. Assign initial velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at the target temperature [4]. - Energy Minimization: Use a steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithm to remove bad contacts and high-energy configurations from the initial structure. This step is crucial before starting a dynamics run. Run until the maximum force is below a chosen threshold (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm).

- NVT Equilibration: Run a short simulation (e.g., 100-500 ps) in the NVT ensemble to stabilize the temperature.

- Thermostat: Use Nosé-Hoover with a coupling constant (

tau_t) of 0.5-1.0 ps. - Time Step: 1.0 fs.

- Monitor: System temperature and potential energy for stability.

- Thermostat: Use Nosé-Hoover with a coupling constant (

- NPT Equilibration: Run a longer simulation (e.g., 1-5 ns) in the NPT ensemble to achieve the correct density.

- Barostat: Use Parrinello-Rahman with a coupling constant (

tau_p) of 2.0-5.0 ps and an estimated isotropic compressibility of ~4.5e-5 bar⁻¹ for organic systems. - Time Step: 1.0 or 2.0 fs (if using constraints).

- Monitor: System density, potential energy, and box volume until they plateau and fluctuate around a stable average.

- Barostat: Use Parrinello-Rahman with a coupling constant (

Protocol 2: Simulating a Temperature Ramp for Glass Transition (T_g) Analysis

Objective: Determine the glass transition temperature of a polymer by simulating a cooling process and analyzing the change in specific volume.

Workflow:

Steps:

- Initial Equilibration: Start from a well-equilibrated polymer melt at a high temperature (e.g., 500 K, which is above the expected T_g), using Protocol 1.

- Cooling Run: Initiate an NPT simulation where the temperature is linearly decreased from the high temperature to a low temperature (e.g., 200 K) over a sufficiently long timescale (e.g., 50-100 ns). A slow cooling rate is critical for obtaining a realistic T_g.

- Thermostat/Barostat: Nosé-Hoover and Parrinello-Rahman are recommended.

- Parameters:

tau_t = 1.0 ps,tau_p = 2.0 ps. - Time Step: 2.0 fs (with constraints).

- Data Analysis: From the simulation output, calculate the specific volume (or density) of the system at regular temperature intervals throughout the cooling process.

- Identify Tg: Plot the specific volume versus temperature. The Tg is identified as the point where a clear change in slope occurs, marking the transition from a rubbery to a glassy state [2]. Fit linear regressions to the high-temperature and low-temperature data; their intersection provides a quantitative estimate of T_g.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function / Role in Simulation | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field | Defines the potential energy function and parameters for interatomic interactions. | Classical FFs (e.g., OPLS-AA, GAFF), Machine Learning FFs (e.g., Vivace, Allegro) for quantum-accurate predictions [2]. |

| Initial Structure Database | Source of initial atomic coordinates for building simulation systems. | PDB (proteins), PubChem (small molecules), Materials Project (crystals) [4]. |

| Thermostat Algorithm | Maintains the simulated system at a target temperature. | Nosé-Hoover (production), Berendsen (equilibration) [5]. |

| Barostat Algorithm | Maintains the simulated system at a target pressure. | Parrinello-Rahman (production), Berendsen (equilibration). |

| Software Suite | Provides the computational engine to run simulations and perform analysis. | GROMACS, LAMMPS, OpenFOAM, OpenMM [5]. |

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potential (MLIP) | A ML-based model trained on quantum data for highly accurate and efficient force calculations. | Key for simulating complex polymer behavior and chemical reactions [2] [4]. |

The rigorous selection and control of time step, temperature, and pressure are not merely technical details but foundational to the validity of molecular dynamics simulations in polymer research. As the field advances with the integration of machine learning force fields and high-performance computing, the protocols outlined here provide a critical framework for ensuring that simulations yield accurate, reproducible, and physically meaningful data. Adherence to these detailed application notes will empower researchers to reliably leverage MD simulations as a powerful tool for the in silico design and characterization of next-generation polymeric materials, ultimately accelerating innovation in materials science and drug development.

The accurate prediction of polymer behavior through molecular dynamics (MD) simulations is foundational to modern materials science and drug development. The fidelity of these simulations is intrinsically linked to the force field employed—the mathematical model that describes the potential energy of a system of atoms. The complex, multi-scale nature of polymeric systems, characterized by diverse local interactions and long-range chain entanglements, presents unique challenges that extend beyond the capabilities of traditional, general-purpose force fields [2]. This application note details the critical accuracy considerations and protocols for employing polymer-specific force fields, providing researchers with a framework for reliable simulation of macromolecular systems. We focus on the latest advancements, including machine learning force fields and modified classical potentials, which promise to bridge the long-standing gap between computational efficiency and quantum-chemical accuracy.

Force Field Paradigms: A Comparative Analysis

The selection of a force field dictates the domain of applicability and the physical phenomena that can be captured in a simulation. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of contemporary force field classes used in polymer research.

Table 1: Comparison of Force Field Paradigms for Polymer Simulations

| Force Field Class | Key Features | Strengths | Limitations | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Fixed-Bond (Class I) | Harmonic bonds, fixed point charges, non-reactive. | High computational efficiency; well-established for equilibrium properties [6]. | Limited transferability; cannot model bond dissociation or chemical reactions [2] [7]. | OPLS-AA, CHARMM, GROMOS [8]. |

| Classical with Cross-Terms (Class II) | Anharmonic potentials; cross-coupling terms (e.g., bond-angle). | Improved accuracy for vibrational spectra and material densities [7]. | Complex parameterization; instability upon bond stretching without reformulation [7]. | PCFF, COMPASS [7]. |

| Reactive Force Fields | Bond-order based interactions; dynamic bonding topology. | Capable of modeling chemical reactions, bond breaking/formation [2]. | Very high computational cost (30-50x fixed-bond); system-specific parameterization [7]. | ReaxFF [2] [7]. |

| Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs) | Neural networks trained on quantum-chemical data. | Near quantum-chemical accuracy; transferability; can model reactions [2] [9]. | High computational cost vs. classical FFs (10-100x); data-intensive training [2] [9]. | Vivace (SimPoly), NeuralIL [2] [9]. |

| Coarse-Grained | Groups of atoms represented as single "beads". | Enables simulation of large systems and long timescales. | Loss of atomic detail; potentials are state-dependent [8]. | MARTINI, PLUM [8]. |

Quantifying Accuracy: Performance on Key Polymer Properties

The true test of a force field's accuracy is its ability to predict experimentally measurable bulk properties. The following table benchmarks the performance of various force fields against two fundamental polymer characteristics: density and glass transition temperature (Tg).

Table 2: Force Field Performance Benchmarking for Polymer Properties

| Force Field / Approach | Reported Density Accuracy | Reported Tg Capability | Key Validation Polymers |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCFF-xe (Reformulated Class II) | Deviations < 3% for most systems; up to 7% for cellulose and glassy carbon [7]. | Not explicitly reported, but designed for mechanical property prediction including failure [7]. | PEEK, polybenzoxazine, epoxy, cyanate ester, cellulose Iβ [7]. |

| Vivace (MLFF) | Accurately predicts densities, outperforming established classical FFs [2]. | Captures second-order phase transitions, enabling Tg prediction [2]. | 130 diverse polymers including polyolefins, polyesters, polyimides, siloxanes [2]. |

| Classical FFs (OPLS-AA, etc.) | Performance varies; used as a baseline in benchmarking studies [2] [6]. | Inaccuracies in Tg prediction can lead to errors in ion transport properties [6]. | 19 polymer electrolytes for battery applications [6]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Accuracy Polymer Property Prediction with MLFFs

This protocol is adapted from the SimPoly methodology for using machine learning force fields to predict bulk properties like density and Tg from first principles [2].

1. System Preparation:

- Structure Generation: Construct atomistic models of the polymer repeating unit. For the SimPoly benchmark, molecular weights of repeating units ranged from 28 to 593 g/mol [2].

- Initial Packing: Use software like PACKMOL to pack multiple polymer chains into a simulation box with periodic boundary conditions. The number of chains should be sufficient to represent the bulk state.

2. Force Field Assignment:

- MLFF Selection: Employ a specialized MLFF such as Vivace. Its architecture uses a multi-cutoff strategy, handling short-range interactions (< 3.8 Å) with SE(3)-equivariant operations and mid-range interactions (up to 6.5 Å) with efficient invariant operations [2].

3. Simulation Procedure:

- Equilibration - Density:

- Ensemble: NPT (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature).

- Temperature: 300 K.

- Pressure: 1 atm.

- Duration: Sufficiently long to achieve plateau in density (typically > 1 ns).

- Equilibration - Tg:

- Perform a series of NPT simulations across a temperature range (e.g., 200 K to 500 K).

- At each temperature, equilibrate the system thoroughly.

- Record the equilibrium density at each temperature.

4. Data Analysis:

- Density: Calculate as the average over the stable production phase of the NPT simulation at 300 K.

- Glass Transition Temperature (Tg): Plot the specific volume (1/density) against temperature. Fit two linear regressions to the high-temperature (rubbery) and low-temperature (glassy) data. The intersection point of these two lines is the estimated Tg [2].

Protocol 2: Ultrafast Equilibration of Complex Polymer Electrolytes

This protocol outlines a computationally efficient method for equilibrating complex polymers like perfluorosulfonic acid (PFSA), which can be ~200% more efficient than conventional annealing [10].

1. System Preparation:

- Morphological Model: Build the polymer system with a sufficient number of chains. For PFSA, 14 to 16 chains are found to be adequate for converging transport and structural properties, minimizing computational resource use [10].

- Force Field Selection: Apply a suitable all-atom Class II force field (e.g., PCFF) or a reactive force field if chemistry is involved.

2. Equilibration Workflow:

- Step 1 - Energy Minimization: Use the steepest descent algorithm to remove high-energy clashes in the initial structure.

- Step 2 - Short NVT Ensemble: Run a short simulation in the NVT (canonical) ensemble to stabilize the temperature.

- Temperature: 300 K.

- Duration: ~50-100 ps.

- Step 3 - Compressed NPT Ensemble: Execute an NPT (isothermal-isobaric) simulation at an elevated pressure to rapidly achieve target density.

- Temperature: 300 K.

- Pressure: 1 atm (or slightly higher to accelerate compaction).

- Duration: Run until density converges. This method avoids the lengthy cycling of annealing [10].

3. Production Run:

- Ensemble: NPT or NVT based on the property of interest.

- Duration: Long enough to obtain statistically meaningful data for properties like mean squared displacement (MSD) or radial distribution functions (RDF).

Workflow: Developing a Machine Learning Force Field for Polymers

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end workflow for developing and validating a specialized MLFF for polymer systems, integrating key steps from the SimPoly approach [2].

A robust computational study requires a suite of software tools and datasets. The following table catalogs essential resources for conducting polymer simulations with high accuracy.

Table 3: Essential Resources for Polymer Force Field Simulations

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| PolyArena Benchmark [2] | Experimental Dataset | Provides experimental densities and Tg for 130 polymers to validate force field accuracy. | Used in Protocol 1, Step 4 for benchmarking MLFF predictions. |

| PolyData [2] | Quantum-Chemical Dataset | Contains quantum-chemically labeled polymer structures for training MLFFs. | Foundational for developing MLFFs as in the workflow diagram. |

| LUNAR [7] | Parameterization Software | Provides a user-friendly interface for rapid parameterization of MD models, including PCFF-xe. | Assists in parameterizing reformulated Class II force fields for new polymers. |

| Vivace [2] | MLFF Architecture | A fast, scalable, local SE(3)-equivariant GNN for large-scale polymer simulations. | The core force field used in Protocol 1. |

| GROMACS [8] | MD Simulation Engine | High-performance software for performing MD simulations. Supports many force fields. | Can be used to run simulations in Protocol 2. |

| LAMMPS [7] | MD Simulation Engine | A highly versatile MD simulator with extensive force field support. | Used for simulations with reformulated force fields like PCFF-xe [7]. |

Enhanced sampling techniques are a class of computational methods in molecular dynamics (MD) designed to overcome the timescale limitation inherent in standard simulations. The core challenge in MD is that high energy barriers often separate metastable states of a system, causing conventional simulations to become trapped in local energy minima and fail to explore the full configuration space on practical computational timescales [11]. Enhanced sampling methods address this fundamental problem by modifying the sampling process to accelerate the exploration of configuration space while maintaining the correct thermodynamic statistics.

Within the specific context of polymer research, where conformational complexity and rugged energy landscapes are paramount, these techniques enable the study of phenomena such as glass transitions, chain dynamics, and phase behavior that would otherwise be inaccessible [2]. This application note focuses on two powerful approaches: Metadynamics and Variationally Enhanced Sampling, detailing their theoretical foundations, practical implementation protocols, and applications specifically for polymer systems.

Theoretical Framework

Collective Variables and Free Energy Landscape

The foundation of many enhanced sampling methods is the concept of collective variables (CVs), which are low-dimensional functions of the atomistic coordinates that describe the slow modes or reaction coordinates of the system [11]. Formally, for a system with 3N atomic coordinates x ≡ (xi|i = 1 … 3N), CVs are defined as a set of functions θ1(x), θ2(x),…, θM(x) that map the high-dimensional configuration space to an M-dimensional CV space z ≡ (zj|j = 1 … M), where usually M ≪ 3N [11].

The probability of finding the system at a point z in CV space at thermal equilibrium is given by:

[ P(\mathbf{z}) = \langle \delta[\boldsymbol{\theta}(\mathbf{x}) - \mathbf{z}] \rangle ]

The associated free energy surface (FES) is defined as:

[ F(\mathbf{z}) = -k_{\mathrm{B}}T \ln P(\mathbf{z}) ]

where (k_{\mathrm{B}}) is Boltzmann's constant and T is the temperature [11]. Local minima in F(z) correspond to metastable states, while the barriers between them represent the free energy costs of transitions.

Metadynamics

Metadynamics is an adaptive bias potential method that facilitates barrier crossing by discouraging the system from revisiting previously explored regions of CV space [11]. In its standard form, it achieves this by depositing repulsive Gaussian potentials at the current location in CV space during the simulation. The bias potential at time t is given by:

[ V(\mathbf{z}, t) = \sum{t' = \tau{\mathrm{G}}, 2\tau{\mathrm{G}}, \dots}^{t} w \exp\left( -\sum{j=1}^{M} \frac{(zj - zj(t'))^2}{2\sigma_j^2} \right) ]

where w is the Gaussian height, σj determines the width of the Gaussians in the direction of the j-th CV, and τG is the deposition stride [11]. As the simulation progresses, this filling process compensates for the underlying free energy barriers, enabling the system to explore previously inaccessible regions. After sufficient sampling, the accumulated bias potential provides an estimate of the underlying free energy surface: ( F(\mathbf{z}) \approx -V(\mathbf{z}, t \to \infty) + C ).

Well-Tempered Metadynamics introduces a scaling factor that reduces the height of the added Gaussians as the simulation progresses, leading to more convergent free energy estimates [12]. The Gaussian height is tempered according to:

[ w(t) = w0 \exp\left( -\frac{V(\mathbf{z}(t), t)}{k{\mathrm{B}}\Delta T} \right) ]

where w0 is the initial Gaussian height, and ΔT is an effective temperature parameter that controls the bias deposition rate [12].

Variationally Enhanced Sampling

Variationally Enhanced Sampling (VES) is based on a different principle – it constructs the bias potential by minimizing a convex functional defined as:

[ \Omega[V] = \frac{1}{\beta} \ln \frac{\int e^{-\beta [F(\mathbf{z}) + V(\mathbf{z})]} d\mathbf{z}}{\int e^{-\beta F(\mathbf{z})} d\mathbf{z}} + \int p_{\mathrm{target}}(\mathbf{z}) V(\mathbf{z}) d\mathbf{z} ]

where β = 1/kBT, F(z) is the free energy, and ptarget(z) is a target probability distribution [13]. The bias potential that minimizes Ω[V] drives the system to sample according to ptarget(z), and the free energy can be recovered from the relation ( F(\mathbf{z}) = -V(\mathbf{z}) - \frac{1}{\beta} \ln p_{\mathrm{target}}(\mathbf{z}) ).

In practice, the bias potential is expanded in a basis set, and the coefficients are optimized during the simulation. This method benefits from not being affected by the underlying barriers and providing a clear convergence criterion [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential software tools for implementing enhanced sampling in polymer research.

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features for Polymer Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| PySAGES [12] | Software Library | Advanced sampling methods | GPU acceleration; Interfaces with HOOMD-blue, LAMMPS, OpenMM; JAX-based automatic differentiation |

| PLUMED [14] | Software Library | Enhanced sampling & free energy calculations | Extensive CV library; Community-developed methods; Compatible with major MD engines |

| SSAGES [12] | Software Suite | Advanced General Ensemble Simulations | Python interface; Multiple enhanced sampling methods; Cross-platform compatibility |

| OpenMM [12] | MD Engine | High-performance MD simulations | GPU optimization; Custom force support; Python API |

| HOOMD-blue [12] | MD Engine | Particle dynamics simulations | Native GPU support; Python scripting; Polymer system capabilities |

Application to Polymer Systems

Relevant Collective Variables for Polymers

The selection of appropriate CVs is critical for successful enhanced sampling simulations of polymers. Effective CVs should capture the slow degrees of freedom governing structural transitions and phase behavior.

Table 2: Key collective variables for polymer systems.

| Collective Variable | Mathematical Definition | Polymer Property Measured | Application Examples | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radius of Gyration | ( Rg = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N}\sum{i=1}^{N} (\mathbf{r}i - \mathbf{r}{\mathrm{cm}})^2} ) | Chain compactness & folding | Conformational sampling [15]; collapse transitions | ||

| End-to-End Distance | ( R_{\mathrm{ee}} = | \mathbf{r}N - \mathbf{r}1 | ) | Chain flexibility & stretching | Elastic properties; polymer stretching |

| Number of Contacts | ( Q = \sum{i |

Intra/inter-molecular interactions | Folding; aggregation; glass formation | ||

| Torsion Angles | φ = dihedral angle of backbone | Chain conformation | Helix-coil transitions; tacticity effects | ||

| Polymer Thickness | Spatial density distribution | Structural morphology | Thin film formation; interface properties |

Case Study: Conformer Generation with Moltiverse

The Moltiverse protocol demonstrates the effective combination of enhanced sampling methods for polymer-related applications, specifically for generating molecular conformers of drug-like molecules and macrocycles [15]. This approach integrates the extended Adaptive Biasing Force (eABF) method with Metadynamics, using the radius of gyration (RDGYR) as the primary collective variable to drive conformational sampling [15].

In benchmark studies against established software like RDKit and CONFORGE, Moltiverse achieved comparable or superior accuracy, particularly for challenging flexible systems such as macrocycles [15]. This success highlights how physics-based enhanced sampling can overcome limitations of knowledge-based or distance geometry approaches, especially when conformational complexity increases.

Machine Learning-Enhanced Sampling

Recent advances integrate machine learning (ML) with enhanced sampling to address the challenge of CV selection and high-dimensional free energy surfaces [13]. ML techniques can:

- Automatically discover relevant CVs from simulation data using nonlinear dimensionality reduction methods

- Approximate complex free energy surfaces with neural networks

- Accelerate convergence of methods like VES through efficient basis set representations

For polymer systems, this is particularly valuable where traditional CVs might miss important collective motions. ML-derived CVs can capture emergent structural features and phase behaviors that are difficult to pre-specify [13].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Well-Tempered Metadynamics for Polymer Folding

Application: Sampling conformational transitions of a polymer chain from extended to compact states.

Required Tools: PySAGES or PLUMED coupled with an MD engine (e.g., GROMACS, LAMMPS, OpenMM) [12].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

System Preparation:

- Construct initial extended polymer structure using molecular builder software.

- Solvate the polymer in an appropriate solvent box using packing tools.

- Add ions to neutralize system charge if required.

Equilibration:

- Energy minimization using steepest descent algorithm until convergence (Fmax < 1000 kJ/mol/nm).

- NVT equilibration for 100 ps with position restraints on polymer heavy atoms.

- NPT equilibration for 200-500 ps until density stabilizes.

Collective Variable Selection:

- Define radius of gyration (Rg) as the primary CV using all or subset of polymer backbone atoms.

- Optionally include number of intramolecular contacts as a secondary CV.

Metadynamics Parameters:

- Gaussian height (w₀): 0.5-1.0 kJ/mol

- Gaussian width (σ): Determine from short unbiased simulation CV fluctuations

- Deposition stride: 500-1000 MD steps

- Bias factor (ΔT): 10-60 (higher values for larger barriers)

Production Simulation:

- Run well-tempered metadynamics for sufficient time to observe multiple folding/unfolding transitions.

- Monitor convergence by checking stabilization of bias potential.

Analysis:

- Reconstruct free energy surface as a function of Rg.

- Identify metastable states and transition barriers.

- Extract representative structures from free energy minima.

Protocol: Adaptive Biasing Force for Polymer-Polymer Interactions

Application: Calculating potential of mean force (PMF) between polymer chains.

Required Tools: PySAGES with ABF method or PLUMED with ABF functionality [12].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

System Setup:

- Create simulation box with two polymer chains at varying initial separations.

- For efficient sampling, use a constrained or harmonic potential to maintain separation along the reaction coordinate.

Reaction Coordinate Definition:

- Define CV as the distance between centers of mass of the two polymer chains.

ABF Configuration:

- Divide the reaction coordinate range into bins (typically 0.1 Å width).

- Set minimum samples per bin before applying bias (typically 100-500).

- Define the full range of the reaction coordinate to cover both associated and dissociated states.

Simulation Execution:

- Run ABF simulation until sufficient sampling is achieved across all bins.

- Monitor convergence by checking stability of the mean force estimate in each bin.

PMF Calculation:

- Integrate the accumulated mean force to obtain the PMF.

- Apply appropriate statistical analysis to estimate errors.

Table 3: Key parameters for enhanced sampling methods in polymer applications.

| Parameter | Metadynamics | Adaptive Biasing Force | Variationally Enhanced Sampling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Critical Settings | Gaussian height, width, deposition stride | Bin width, samples before bias | Basis set size, target distribution |

| Typical Values | σ = 0.05-0.2 nm, τG = 500 steps | Bin width = 0.05-0.1 nm, 500 samples | Legendre polynomials (order 10-20) |

| Convergence Metrics | Bias potential stability | Mean force stability in all bins | Ω[V] functional minimization |

| Polymer-Specific Considerations | Multiple CVs for complex transitions; Careful σ selection for polymer dimensions | Extended ABF for torsional CVs | ML-derived CVs for unknown pathways |

Metadynamics and Variationally Enhanced Sampling provide powerful frameworks for extending the timescales accessible to molecular dynamics simulations of polymer systems. When implemented with appropriate collective variables and parameters, these methods enable the study of complex polymer phenomena such as folding transitions, glass formation, and self-assembly processes. The integration of machine learning approaches with these established enhanced sampling techniques represents a promising direction for addressing increasingly complex questions in polymer physics and materials design. For researchers investigating polymer behavior, these protocols provide a foundation for implementing enhanced sampling methods that can reveal thermodynamic and kinetic properties inaccessible to standard simulation approaches.

Practical Applications: Leveraging MD Simulations for Polymer Design in Drug Delivery and Biomedical Engineering

Application Notes

The Critical Role of Drug-Polymer Interactions in Modern Therapeutics

Drug-polymer interactions form the foundational basis of advanced drug delivery systems (DDSs), directly influencing key performance parameters including drug stability, release kinetics, and overall bioavailability. For poorly water-soluble drugs (PWSDs), which represent a significant challenge in pharmaceutical development, amorphous solid dispersions (ASDs) where the drug is molecularly dispersed within a polymeric matrix have emerged as a pivotal strategy to enhance solubility and achieve effective oral delivery [16] [17]. The compatibility between the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and the polymer is paramount; it dictates the physical stability of the amorphous formulation by preventing drug recrystallization and enables controlled release profiles tailored to therapeutic needs [18] [19]. Understanding these interactions at a molecular level, facilitated by techniques like molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, allows researchers to rationally design superior formulations, moving away from traditional trial-and-error approaches.

Key Analytical and Computational Findings

Recent studies employing a combination of experimental and computational methods have yielded quantitative insights into drug-polymer behavior. The data below summarizes critical findings on miscibility and stability from current research.

Table 1: Experimental Data on API-Polymer Miscibility and Stability

| API / Formulation | Polymer | Key Finding | Quantitative Result | Analysis Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malonic Acid | HPMCAS | Saturation concentration | 17% (w/w) | DSC, Optical Microscopy |

| Ibuprofen | HPMCAS | Saturation concentration | 23% (w/w) | DSC, Optical Microscopy |

| Naproxen | HPMCAS | Saturation concentration | 13% (w/w) | DSC, Optical Microscopy |

| Celecoxib (CEL) | PVP-VA | Drug-Polymer Miscibility (Δδ) | 1.01 MPa¹/² | Hildebrand Solubility Parameter |

| Celecoxib (CEL) | HPMCAS | Drug-Polymer Miscibility (Δδ) | 0.65 MPa¹/² | Hildebrand Solubility Parameter |

| CEL-Na⁺-PVP-VA | ASSD | Interaction Energy (from MD) | Most Stable | Molecular Dynamics (MD) |

Table 2: Controlled Release Profiles from Phase-Separated Polymer Blends

| Polymer Blend (PLA/HPMC) | Drug Loading | Release Profile Description | % Drug Released (at 6 h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30/70 | 10 wt% Nicotinamide | Rapid, burst release | ~100% |

| 50/50 | 10 wt% Nicotinamide | Fast initial release, transitioning to slower linear release | ~60% |

| 70/30 | 10 wt% Nicotinamide | Slow, extended, nearly linear release | ~20% |

The data demonstrates that solubility parameters, such as those calculated by Hildebrand and Hansen, can provide an initial miscibility screen. A difference (Δδ) of less than 7 MPa¹/² between drug and polymer suggests good miscibility [16] [17]. However, as evidenced by the Celecoxib systems, traditional solubility parameters may not always correlate perfectly with experimental performance, necessitating more advanced modeling approaches [17]. Furthermore, the morphology of multi-polymer systems, such as phase-separated blends, is a powerful tool for tuning drug release, with the hydrophilic polymer fraction acting as a release-controlling channeling agent [19].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Preparation of Amorphous Solid Dispersions via Solvent Evaporation

This protocol details the preparation of binary and ternary amorphous solid dispersions using a solvent evaporation method, adapted from recent research [16].

Materials and Equipment

- Materials: Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) (e.g., Ibuprofen, Naproxen, Celecoxib), Polymer (e.g., HPMCAS, PVP-VA), organic solvents (e.g., Acetone, Chloroform, HPLC grade).

- Equipment: Magnetic stirrer with hotplate, analytical balance, glass vials/beakers, pipettes, solvent-resistant casting surface (e.g., Teflon plates or Petri dishes), fume hood, drying oven or desiccator.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Solution Preparation: Precisely weigh the API(s) and dissolve them in a suitable solvent mixture (e.g., Acetone/Chloroform 3:2 v/v) within a sealed glass vial to prevent solvent evaporation.

- Polymer Addition: Gradually add the pre-weighed polymer to the API solution under constant stirring (e.g., 300-500 rpm) until it is completely dissolved, ensuring a clear, homogeneous solution is obtained.

- Casting: Pour the final drug-polymer solution onto a leveled, solvent-resistant casting surface placed inside a fume hood.

- Solvent Evaporation: Allow the solvent to evaporate slowly at ambient temperature and pressure for a minimum of 24-48 hours.

- Drying: Transfer the cast film to a vacuum desiccator or drying oven to remove any residual solvent for at least one week. Confirm complete solvent removal using techniques like Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA).

- Milling (Optional): For powder formulations, gently grind the dried film using a mortar and pestle and sieve it to obtain a uniform particle size.

Critical Notes

- All procedures involving organic solvents must be performed in a fume hood with appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE).

- The drug-to-polymer ratio and choice of solvent are critical and should be based on preliminary solubility and miscibility studies.

- The formed films should be stored in a moisture-free environment, such as a desiccator, to maintain physical stability.

Protocol 2: Molecular Dynamics Simulation for Drug-Polymer Compatibility

This protocol outlines the use of atomistic MD simulations to predict drug-polymer compatibility and interaction strength, a method that has shown superior correlation with experimental performance compared to classical models [17].

System Setup and Parameterization

- Structure Preparation: Obtain or build 3D molecular structures of the drug and polymer. For large polymers, use a representative oligomer chain (e.g., 3-5 monomer units) [18].

- Force Field Selection: Choose an appropriate classical force field (e.g., CHARMM, GAFF, OPLS-AA) and assign partial atomic charges, typically derived from quantum mechanical calculations.

- Simulation Box Construction: Place multiple copies of the drug and polymer molecules in a periodic simulation box using packing software (e.g., PACKMOL). Solvate the system with explicit water molecules (e.g., TIP3P model).

- Energy Minimization: Perform energy minimization to remove any bad contacts and relax the initial structure using a steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithm.

Production Simulation and Analysis

- Equilibration: Run simulations in the NVT (constant Number, Volume, Temperature) and NPT (constant Number, Pressure, Temperature) ensembles to equilibrate the system's density and temperature (e.g., 310 K).

- Production Run: Conduct a long-timescale production simulation (tens to hundreds of nanoseconds) in the NPT ensemble to collect trajectory data for analysis.

- Interaction Energy Calculation: From the trajectory, calculate the non-bonded interaction energy (van der Waals and electrostatic) between the drug and polymer molecules using standard energy decomposition methods available in MD software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER, LAMMPS).

- Stability Assessment: A more negative (favorable) drug-polymer interaction energy correlates with a prolonged stability of the supersaturated amorphous state and improved biopharmaceutical performance [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Studying Drug-Polymer Interactions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Specific Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Cellulosic Polymers | Hydrophobic or enteric polymer matrix for amorphous solid dispersions. | Hypromellose Acetate Succinate (HPMCAS) [16] [17], Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose (HPMC) [19] |

| Vinyl-Based Polymers | Hydrophilic polymer providing miscibility and inhibiting crystallization. | Polyvinylpyrrolidone-vinyl acetate (PVP-VA) [17], Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP K12) [18] |

| Biodegradable Polyesters | Hydrophobic polymer for extended release; forms phase-separated blends. | Polylactic Acid (PLA) [19] |

| Model Drug Compounds | Poorly water-soluble APIs for testing solubility and release enhancement. | Ibuprofen, Naproxen, Flurbiprofen [16], Celecoxib [17], Nicotinamide [19] |

| Salts for ASSDs | Form in-situ amorphous salts to enhance stability and solubility. | Sodium (Na⁺), Potassium (K⁺) salts [17] |

| Organic Solvents | Dissolve drug and polymer for solvent-based preparation methods. | Acetone, Chloroform (HPLC grade) [16] |

Visualization of a Phase-Separated Controlled Release System

The following diagram illustrates the mechanism of controlled drug release from a phase-separated polymer blend, a strategy that leverages morphology to fine-tune release profiles [19].

Understanding and predicting the interactions between synthetic polymers and proteins is a cornerstone of modern drug development and biomaterials science. These interactions govern critical processes, including the stability of polymer-based drug formulations, the performance of protein-binding polymers in diagnostic assays, and the design of polymers that can disrupt pathological protein-protein interactions (PPIs) [20] [21]. The binding affinity, quantified by the dissociation constant ((K_d)), defines the strength of these interactions, while the accompanying conformational changes in the protein and/or polymer determine the functional outcome [22]. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide a powerful computational framework to probe these phenomena at an atomic level, offering insights that are often challenging to obtain experimentally. This Application Note details protocols for using MD simulations to predict binding affinities and characterize conformational changes in polymer-protein systems, providing a standardized approach for researchers and drug development professionals.

Theoretical Background and Key Challenges

Fundamentals of Polymer-Protein Interactions

Polymer-protein complexation is driven by a combination of non-covalent forces, such as electrostatics, hydrophobic association, and hydrogen bonding, much like native PPIs [20]. A key advantage of synthetic polymers is the unparalleled flexibility in tuning their properties—including size, charge density, rigidity, and topology—to achieve desired binding characteristics. Unlike small molecules, polymers can make polyvalent contacts with protein surfaces, which can cooperatively enhance the interaction strength [20]. The binding process is often entropically driven due to the release of counterions and water molecules from the interacting surfaces [20].

Challenges in Prediction

A significant challenge in the field is predicting binding affinity from structural models. While the buried surface area upon complex formation is a known physico-chemical correlate, it does not hold for flexible complexes, which incur a significant entropic penalty upon binding [22]. Furthermore, protein surfaces are polyampholytic, meaning they contain patches of positive, negative, and neutral charges. Interactions can therefore occur even when the net charges of the protein and polymer are the same, via charge-patch or charge-regulation mechanisms [20]. These complexities necessitate computational approaches that can account for dynamic behavior and solvation effects.

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for setting up and running MD simulations to study polymer-protein interactions, from initial system preparation to final analysis.

Protocol 1: MD Simulations of Polymer-Protein Binding

Objective: To simulate the formation and stability of a polymer-protein complex and calculate key interaction metrics. Application: Studying binding mechanisms, identifying critical interaction sites, and performing in silico screening of polymer designs.

| Step | Procedure | Key Parameters & Software |

|---|---|---|

| 1. System Preparation | Obtain 3D structures of the protein (e.g., from PDB) and polymer. Optimize polymer geometry using quantum chemistry methods (e.g., Gaussian). | Software: GaussView, Gaussian [21]. Method: Density Functional Theory (DFT) with 6-31 basis sets. |

| 2. Topology Building | Generate topology and parameter files for the protein and polymer using an appropriate force field. | Software: ACPYPE (AnteChamber Python Parser interface) [21]. Force Fields: AMBER99SB-ILDN for proteins, GAFF for polymers [21]. |

| 3. Solvation and Neutralization | Place the protein-polymer system in a simulation box, solvate with water molecules, and add ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) to neutralize the system charge. | Software: GROMACS [21]. Water Model: TIP3P or SPC. Ion Concentration: As per physiological or experimental conditions. |

| 4. Energy Minimization | Minimize the energy of the system to remove steric clashes and unfavorable contacts. | Algorithm: Steepest descent or conjugate gradient. Convergence Criterion: Force below a selected threshold (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm). |

| 5. System Equilibration | Equilibrate the system in two phases: first with position restraints on solute atoms at constant volume and temperature (NVT), then at constant pressure and temperature (NPT). | NVT Thermostat: Berendsen or Nosé-Hoover (e.g., 300 K, 100 ps). NPT Barostat: Berendsen or Parrinello-Rahman (e.g., 1 bar, 100 ps) [21]. |

| 6. Production MD | Run an unrestrained simulation to collect data for analysis. The length of the simulation depends on the system size and dynamics. | Ensemble: NPT is standard. Simulation Time: Typically 100 ns to 1 µs. Time Step: 2 fs [21]. |

| 7. Analysis | Analyze the trajectory to compute RMSD, RMSF, Rg, SASA, hydrogen bonds, and other interaction metrics. | Software: Built-in GROMACS modules (gmx rms, gmx rmsf, gmx gyrate, gmx sasa, gmx hbond) [21]. |

The following workflow diagram outlines the key stages of this protocol:

Protocol 2: Characterizing Conformational Changes with PCA