Melt Cycle Effects on Polymer Properties: From Molecular Mechanisms to Advanced Applications in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of how melt processing cycles fundamentally alter the structural, thermal, and mechanical properties of polymeric materials.

Melt Cycle Effects on Polymer Properties: From Molecular Mechanisms to Advanced Applications in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of how melt processing cycles fundamentally alter the structural, thermal, and mechanical properties of polymeric materials. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational science, advanced characterization methodologies, optimization strategies for troubleshooting, and comparative validation techniques. By exploring the critical interplay between processing parameters and material performance, this review serves as an essential guide for designing and selecting polymer systems with tailored properties for biomedical and clinical applications, ensuring efficacy, stability, and manufacturability.

Fundamental Principles: How Melt Cycles Dictate Polymer Structure and Performance

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: Why is the viscosity of my polymer melt dropping significantly during processing, leading to poor dimensional stability in the final part?

A: A sharp drop in viscosity is a classic sign of shear thinning, a fundamental non-Newtonian property of polymer melts [1]. As the shear rate increases in processes like extrusion or injection molding, the entangled polymer chains align in the direction of flow, reducing their resistance to movement [2] [1]. To troubleshoot:

- Verify Process Conditions: Ensure the processing shear rates are within the expected range for your material. An unexpectedly high screw speed can induce excessive shear thinning.

- Check Material Structure: Analyze the molecular weight distribution (MWD). A broader MWD can cause the onset of shear thinning at lower shear rates [1]. Rheological measurements can link this behavior directly to the polymer's molecular structure.

Q2: My injection-molded parts are warping after cooling. What could be the cause?

A: Warpage is often caused by non-uniform relaxation and frozen-in stresses during solidification [1]. If the melt has not relaxed stresses before solidifying in the mold, these "frozen-in" stresses can release over time, causing deformation.

- Investigate Melt Elasticity: The polymer's elasticity, characterized by its relaxation time (λ), is a key factor [1]. A material with a long relaxation time behaves more solid-like and may not relax sufficiently within the process cycle time.

- Optimize Cooling & Material: Review cooling rates and mold design for uniformity. Also, consider the Deborah number (De = material relaxation time / process time); a high De number indicates an overly elastic response under your process conditions, which may require a material with a shorter relaxation time [1].

Q3: After several recycling cycles, my polymer blend becomes brittle and exhibits phase separation. Why?

A: Multiple melting-recycling cycles can lead to thermal degradation and differentiation of polymer components [3]. This is especially critical for polymer blends.

- Assess Thermal Stability: Thermoplastic polymers like TPU have poor thermal stability and cannot bear repeated high-temperature processing over multiple cycles without property loss [3].

- Use a Compatibilizer: For blends of immiscible polymers (e.g., thermoplastic polyurethane and polypropylene), a compatibilizer like maleic anhydride grafted polypropylene (MA) is crucial. Research shows that MA significantly mitigates the differentiation effect and poor phase adhesion caused by multiple recycling cycles [3].

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol 1: Characterizing Shear-Thinning Behavior Using Rheometry

Objective: To measure the dependence of melt viscosity on shear rate and determine the zero-shear viscosity (η₀) and degree of shear thinning.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Use a precisely weighed amount of polymer pellets or a pre-molded disk.

- Instrument Setup: Employ a rotational rheometer with a parallel-plate or cone-and-plate geometry. Set the test temperature to the desired processing temperature (e.g., 10-30°C above the melting point) [1].

- Testing Procedure:

- Perform a steady-state flow sweep test.

- Apply a range of shear rates (e.g., 0.01 to 1000 s⁻¹) and measure the resulting shear stress.

- Calculate the viscosity (η) at each shear rate.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot viscosity (η) versus shear rate (γ̇) on a log-log scale.

- The plateau in viscosity at the lowest shear rates is the zero-shear viscosity (η₀).

- The slope of the curve as viscosity decreases indicates the shear-thinning intensity.

Protocol 2: Investigating the Effects of Multiple Melt-Recycling Cycles

Objective: To evaluate the degradation of mechanical and thermal properties of a polymer or blend after successive melt-processing cycles.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare initial blends according to desired weight ratios (e.g., T/P/MA blends) [3].

- Recycling Simulation:

- First Cycle (One-off): Process the blend using a hot press or extruder at the recommended melting temperature and pressure to form a sheet or test specimen [3].

- Mechanical Fracture: Subject the formed specimen to tensile testing until break, as a simulation of mechanical damage during the product's life [3].

- Subsequent Cycles (Post-2nd, Post-3rd): Cut the fractured material into small pieces, mix, and repeat the hot-pressing and mechanical fracture steps [3].

- Evaluation:

- Tensile Testing: After each cycle, prepare new dog-bone specimens and test for tensile stress and strain at break according to ASTM D638 [3].

- Morphological Analysis: Use Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to observe the fracture surface for evidence of phase separation or changes in particle size [3].

- Thermal Analysis: Perform Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) or Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) to check for changes in thermal stability or melting point.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Rheological Parameters and Their Correlation to Polymer Structure and Processing

| Rheological Parameter | Definition & Measurement | Correlation to Molecular Structure | Impact on Processing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-Shear Viscosity (η₀) | The plateau viscosity measured at very low shear rates [1]. | Proportional to ~Mw3.4 for entangled polymers; sensitive to molecular weight [1]. | Determines flow at low stresses (e.g., sag, leveling); high η₀ requires more energy to pump. |

| Relaxation Time (λ) | The characteristic time for polymer chains to relax after deformation; can be estimated as 1/ωc (inverse of crossover frequency) from dynamic tests [1]. | Increases with molecular weight and long-chain branching [1]. | Governs elastic effects (die swell, parison sag); a high λ relative to process time (high De) leads to more solid-like behavior. |

| Crossover Modulus (Gc) | The modulus value where the storage (G') and loss (G") moduli are equal [1]. | A relative measure of molecular weight distribution (MWD); a lower Gc often indicates a broader MWD [1]. | Affects the shear-thinning onset; a broader MWD (lower Gc) generally improves processability. |

Table 2: Effect of Multiple Recycling Cycles on a TPU/PP Blend (Illustrative Data based on [3])

| Blend Composition | Recycling Stage | Tensile Stress at Break (MPa) | Tensile Strain at Break (%) | Key Morphological Observation (SEM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPU/PP (70/30) | Post-1st Cycle | 22.5 | 350 | Some phase separation visible. |

| Post-2nd Cycle | 19.0 | 250 | Increased phase separation. | |

| Post-3rd Cycle | 15.5 | 150 | Severe phase separation; brittle fracture. | |

| TPU/PP/MA (70/30/5) | Post-1st Cycle | 24.0 | 380 | Improved phase adhesion. |

| Post-2nd Cycle | 22.0 | 320 | Minor phase coarsening. | |

| Post-3rd Cycle | 20.5 | 300 | Phase adhesion maintained; mitigated degradation. |

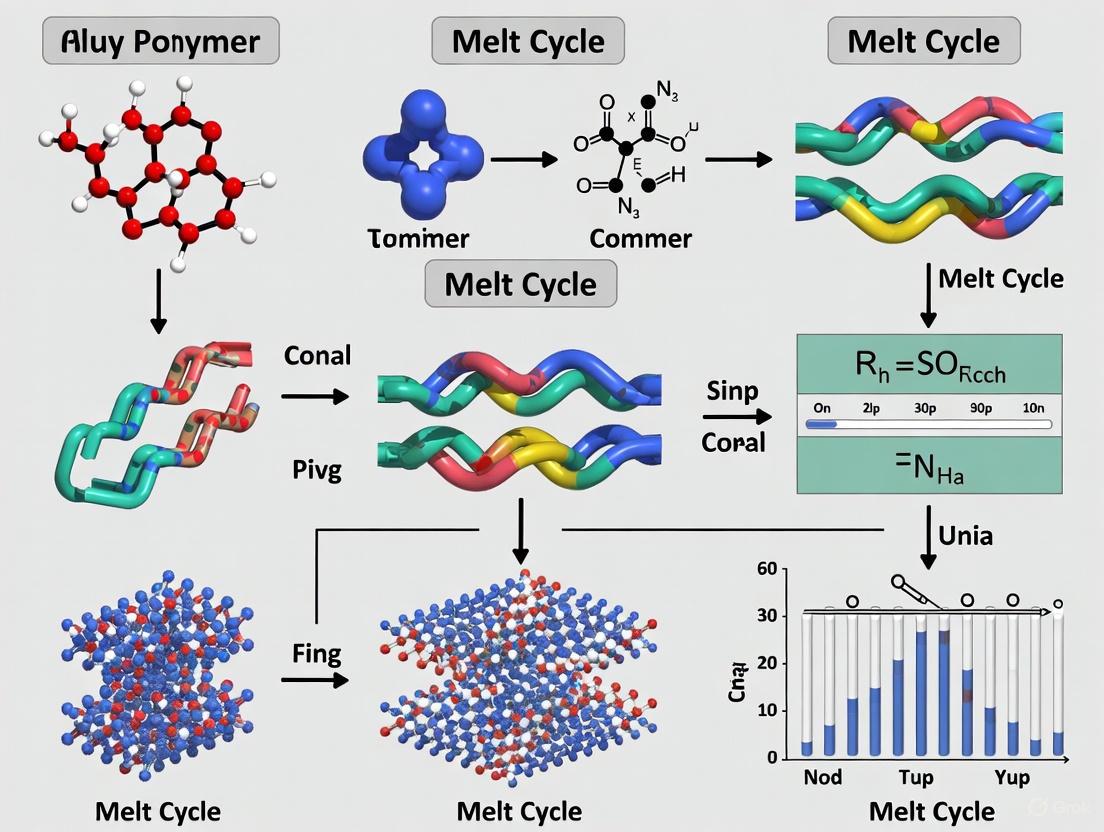

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Polymer Melt Processing Journey

Molecular Structure to Melt Property

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Their Functions in Polymer Melt Research

| Material / Reagent | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Maleic Anhydride Grafted Polypropylene (MA-g-PP) | A compatibilizer used to improve the interfacial adhesion and reduce phase separation in blends of non-polar polypropylene with polar polymers (e.g., TPU), especially during recycling studies [3]. |

| Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU) | A versatile polymer with good toughness and mechanical properties, often used as a base material in blend studies to investigate the effects of melt cycles on materials with lower thermal stability [3]. |

| Polypropylene (PP) | A common semicrystalline polymer with good rigidity and thermal stability, frequently used in blends to modify the properties of other thermoplastics and study crystallization behavior during solidification [3]. |

| Long-Chain Branched Polyethylene (e.g., LDPE) | A model polymer used to study the pronounced effects of long-chain branching on melt elasticity, extensional viscosity (strain hardening), and die swell, compared to linear analogues (LLDPE, HDPE) [1]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does my polymer sample exhibit unexpectedly slow crystallization kinetics during the melt cycle? This is frequently due to the retarding effect of chain entanglements. These topological constraints hinder the rearrangement of polymer chains into an ordered crystal lattice. A higher density of entanglements in the melt has been shown to raise the free energy barrier for primary nucleation and can suppress the ultimate crystallinity of the material [4].

Q2: How does the level of entanglement in the melt influence the final properties of the crystallized polymer? The entanglement density directly impacts material properties. Higher entanglements can lead to the formation of longer loops and tie molecules during crystallization. These topological constraints not only retard crystallization kinetics but also result in reduced lamellar crystal thickness and lower overall crystallinity, which in turn affects mechanical properties like modulus and toughness [4].

Q3: My polymer crystallized under pressure shows a different morphology and higher melting point. Why? The application of pressure during crystallization can fundamentally alter the pathway. Research has demonstrated that under elevated pressures, the typical shear-induced alignment can be suppressed, leading to more isotropic morphologies. Furthermore, pressure can induce the formation of different crystalline polymorphs, resulting in melting temperatures up to 10 K higher than in quiescently crystallized samples [5].

Q4: What are the best techniques to characterize the entanglement state of a polymer melt? While direct measurement is complex, dynamic Monte Carlo simulations can be used to characterize melts by the average number of entangled chains around each polymer, using methods similar to primitive path analysis. Experimentally, rheological measurements and the study of crystallization kinetics can provide insights into the entanglement state [4].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Probable Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent crystallization rates between batches | Variations in initial entanglement density due to different thermal or shear histories. | Standardize the melt-conditioning protocol before crystallization experiments. Ensure consistent pre-shear and annealing steps. |

| Low crystallinity despite favorable supercooling | High degree of entanglements acting as topological constraints that suppress crystal growth and lamellar thickness. | Adjust thermal history to promote partial disentanglement or consider additives that act as nucleating agents. |

| Unexpectedly high melting point | Formation of a different crystalline polymorph induced by specific processing conditions (e.g., high pressure). | Analyze crystalline structure with X-ray scattering to identify the polymorphic form and correlate with processing parameters [5]. |

| Poor reproducibility in shear-induced crystallization | Inadequate control over combined shear and pressure conditions, leading to a shift in crystallization pathway. | Utilize rheological tools capable of applying simultaneous rotational shear flow and precise pressure control [5]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Simulating the Retardation Effect of Entanglements on Melt Crystallization

This protocol is based on dynamic Monte Carlo simulations used to investigate how intermolecular topological entanglements retard polymer melt crystallization [4].

- Objective: To reproduce the weak retardation effects of entanglements on crystallization kinetics and analyze the resulting crystal morphology.

- Methodology:

- Melt Preparation: In a discrete lattice space (e.g., 24 × 128 × 128 cubic entities), arrange polymer chains (e.g., 1344 chains of length 256) in a parallel stacking configuration.

- Athermal Relaxation: Relax the system under athermal conditions for a defined number of Monte Carlo (MC) cycles (e.g., 2 × 10^6 cycles) to generate random coils. To create melts with varying entanglement densities, the period of interpenetration during relaxation can be controlled. The extent of entanglement is characterized by the average number of entangled chains surrounding each polymer.

- Crystallization Simulation: Subject the prepared melts to a linear cooling ramp. During cooling, monitor the formation of crystalline bonds (defined as bonds surrounded by more than a threshold number of parallel bonds, e.g., >10).

- Data Analysis:

- Crystallinity: Calculate as the ratio of crystalline bonds to the total number of bonds in the system over time.

- Kinetic Analysis: Perform an analysis of primary crystal nucleation to determine the fold-end surface free energy.

- Structural Analysis: Analyze the generation of loops and tie molecules during crystallization.

Protocol 2: Investigating Combined Pressure and Shear Flow on Crystallization

This protocol outlines experimental methods for studying crystallization under simultaneous pressure and shear, which can alter the fundamental crystallization pathway [5].

- Objective: To understand the synergistic effects of pressure and shear flow on polymer crystallization kinetics and morphology.

- Methodology:

- Sample Loading: Load a polymer sample (e.g., a commercial isotactic polypropylene) into a rheometer equipped with a pressure cell.

- Application of Conditions: Subject the sample to a defined melting and deformation cycle under simultaneous rotational shear flow and controlled pressure (ranging from moderate ~2 bar to elevated 100–180 bar).

- Quenching: Rapidly cool or quench the sample to solidification.

- Post-Analysis:

- Morphology: Use techniques like X-ray scattering to identify crystalline structures and morphologies, noting the presence of any new crystalline peaks indicative of polymorphism.

- Thermal Properties: Perform Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) to measure the melting temperature and compare it with quiescently crystallized samples.

| Average Entangled Chains | Nucleation Barrier (Fold-end Surface Free Energy) | Retardation Effect on Crystallization | Impact on Lamellar Thickness |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 chains | Lower | Weak | Less suppressed |

| 7 chains | Moderate | Moderate | Moderately suppressed |

| 10 chains | Higher | Significant | Suppressed |

| 13 chains | Highest | Most significant | Most suppressed |

| Applied Pressure | Shear Flow | Resulting Morphology | Melting Temperature Shift | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ~2 bar (Moderate) | Applied | Shish-kebab | Minimal | Conventional flow-induced alignment. |

| 100-180 bar (Elevated) | Applied | Isotropic (Alignment suppressed) | Up to +10 K | Pressure-induced shift in crystallization pathway; potential polymorphism. |

Experimental Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function / Relevance in Research |

|---|---|

| Dynamic Monte Carlo Simulation | A computational method used to investigate the microscopic mechanisms of polymer crystallization, allowing for the preparation of melts with controlled entanglement densities and the analysis of nucleation kinetics and topological constraints [4]. |

| Rheometer with Pressure Cell | An instrumental tool capable of applying simultaneous rotational shear flow and controlled pressure to polymer melts, enabling the study of crystallization under conditions that mimic industrial processing and can fundamentally alter the crystallization pathway [5]. |

| Isotactic Polypropylene (iPP) | A common commercial polymer often used as a model system in crystallization studies due to its well-characterized behavior and relevance in industrial applications. Its response to shear, pressure, and thermal history is actively studied [5]. |

| X-ray Scattering | A critical analytical technique used to determine the crystalline structure and morphology of solidified polymer samples. It can identify different crystalline polymorphs and characterize orientations (e.g., shish-kebab structures) [5]. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | A thermal analysis technique used to measure melting temperatures, crystallization temperatures, and degrees of crystallinity. It is essential for linking processing conditions to the thermal properties of the final material [5]. |

| Brillouin Light Scattering (BLS) | A non-invasive optical technique that probes the propagation of thermal phonons to determine the high-frequency complex mechanical modulus (storage and loss) of materials, providing insights into viscoelastic behavior and glass transition phenomena [5]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How do key processing parameters affect the mechanical properties of polymers like PLA?

Answer: Processing parameters directly influence mechanical properties by affecting the polymer's internal structure, particularly its degree of crystallinity. For polylactide (PLA), parameters such as injection temperature, injection pressure, and mold temperature have a documented impact on tensile strength and hardness [6]. Higher processing temperatures can increase molecular mobility, potentially leading to a higher crystallinity percentage, which generally enhances strength and hardness but may reduce elongation at break. The table below summarizes specific experimental findings for PLA [6].

Table 1: Effect of Injection Molding Parameters on PLA Properties

| Processing Parameter | Effect on Degree of Crystallinity | Effect on Tensile Strength | Effect on Hardness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increased Injection Temperature | Increases | Increases | Increases |

| Increased Injection Pressure | Increases | Increases | Increases |

| Increased Mold Temperature | Increases | Increases | Increases |

FAQ 2: Why does my material degrade after multiple processing cycles?

Answer: Subjecting polymers to repeated heating and cooling cycles, known as thermal cycling, can lead to thermo-oxidative degradation [7]. This is a significant concern in the context of research on melt cycle effects. During each cycle, the polymer is exposed to elevated temperatures in the presence of oxygen, which can cause chain scission or cross-linking. For polyamides like PA6, this degradation manifests as:

- Increased Melt Viscosity: A drastic increase in viscosity can occur, which may prevent proper impregnation in composite processes [7].

- Changes in Molar Mass: Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) can reveal lower molar masses after long exposure [7].

- Reduced Mechanical Performance: Degradation ultimately compromises the material's structural integrity.

Troubleshooting Guide: To mitigate degradation during multiple melt cycles:

- Identify Processing Window: Determine the time-temperature profile before the viscosity increases drastically [7].

- Incorporate Antioxidants: Add phosphorous-based antioxidants to improve thermal stability, though their efficiency may decrease with very long dwell times [7].

- Minimize Exposure: Restrict processing to short times at elevated temperatures to maintain initial polymer properties [7].

FAQ 3: How can I control the final properties of a polymer from the beginning of the process?

Answer: For batch processes like free-radical polymerization, a model-based feedback control strategy can be employed to target specific Molecular Weight Distributions (MWD), which are critical for end-use properties [8]. This involves:

- Process Modeling: Using a deterministic model of the polymerization kinetics.

- Optimal Trajectory Calculation: Computing a sequence of reactor temperature setpoints that will theoretically produce the target MWD.

- On-line Estimation: Using an Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) to incorporate infrequent and delayed off-line MWD measurements, updating the state estimates to account for model-plant mismatch.

- Feedback Control: Recomputing and updating the temperature setpoints at each sampling point during the batch to steer the process toward the desired final MWD [8].

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Protocol 1: Assessing the Impact of Injection Molding Parameters on PLA

This protocol is adapted from research investigating the effect of process parameters on the properties of Polylactide (PLA) [6].

1. Objective: To evaluate the influence of injection temperature, pressure, and mold temperature on the mechanical properties and degree of crystallinity of PLA.

2. Materials:

- Polymer: Polylactide (PLA), e.g., Ingeo Biopolymer 3251D.

- Equipment: Horizontal screw injection molding machine (e.g., UT90 from Ponar Żywiec), thermostat, dryer, electronic scales.

3. Methodology:

- Material Preparation: Dry the PLA granules for 8 hours at 80°C to remove moisture.

- Sample Preparation: Inject samples using the machine parameters outlined in Table 2.

- Systematic Variation: Produce sample sets by systematically varying one parameter at a time (e.g., create three groups with injection temperatures of 180°C, 195°C, and 210°C while keeping other parameters constant).

- Testing and Analysis:

- Tensile Test: Perform static tensile tests according to ASTM D638 on dog-bone shaped samples.

- Hardness Test: Measure material hardness using an appropriate scale.

- DSC Analysis: Perform Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) to determine the thermal properties and calculate the degree of crystallinity.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Polymer Processing Studies

| Material / Reagent | Function in Experiment | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Polylactide (PLA) | A biodegradable thermoplastic polymer; the base material under investigation. | Evaluating the effect of melt cycles on crystallinity and mechanical properties [6]. |

| Polyamide (PA6) | An engineering thermoplastic; subject to thermo-oxidative degradation. | Studying viscosity change and degradation during thermal cycling模拟复合材料生产过程 [7]. |

| Antioxidant (e.g., Phosphonite-based) | Additive to improve the thermal stability of polymers during processing. | Mitigating the increase in melt viscosity during repeated heating cycles [7]. |

| Compatibilizer (e.g., Maleic Anhydride grafted PP) | A chemical agent used to improve interfacial adhesion in polymer blends. | Enhancing the properties of recycled thermoplastic polyurethane and polypropylene blends [3]. |

Protocol 2: Investigating the Effects of Multiple Melting-Recycling Cycles

This protocol is based on a study simulating the recycling of polymer waste blends [3].

1. Objective: To explore the impacts of repeated melting-recycling cycles and the presence of a compatibilizer on the properties of thermoplastic blends.

2. Materials:

- Polymers: Thermoplastic Polyurethane (T) and Polypropylene (P) waste blends.

- Compatibilizer: Maleic anhydride grafted polypropylene (MA).

3. Methodology:

- Blend Preparation: Trim T/P and T/P/MA blends into small pieces and mix according to predetermined ratios (e.g., 90/10/0, 70/30/0, 50/50/0, and with MA).

- Hot-Pressing Cycle: Use a hot-pressing machine to form blended samples. The specified hot-pressing temperature will depend on the blend composition, typically ranging from 165°C to 210°C at a pressure of 20 MPa.

- Mechanical Fracture: Subject the hot-pressed samples to a tensile test to simulate one-off mechanical damage.

- Recycling Simulation: The fractured pieces are then collected, mixed, and hot-pressed again. Samples that undergo this process once are denoted as "post-2nd-recycling"; repeating the cycle produces the "post-3rd-recycling" group.

- Analysis:

- SEM Observation: Observe the fracture morphology of the blends to assess phase separation and compatibilizer effectiveness.

- Tensile Testing: Measure tensile stress and strain at break for each recycling group.

- DSC Analysis: Monitor changes in thermal properties through multiple cycles.

Cause-and-Effect Analysis of Processing-Property Relationships

The following diagram synthesizes information from the search results to illustrate the core cause-and-effect relationships between processing parameters, structural changes in the polymer, and the final material properties, with a particular focus on the effects of multiple melt cycles.

Diagram Title: Cause-Effect Map of Polymer Processing

This diagram visually maps the logical relationships identified in the research. For instance, increasing temperature (a processing parameter) can lead to thermo-oxidative degradation (a structural change), which in turn increases melt viscosity and reduces tensile strength (final properties). The use of additives like antioxidants can mitigate this degradation pathway.

Phase Morphology Development in Blends and Composites During Processing

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Problem: Inability to Achieve or Maintain Fibrillar Morphology

- Issue: The dispersed phase forms droplets or coarse particles instead of the desired fibrils during melt spinning or extrusion.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Insufficient Elongational Force: The take-up velocity or draw ratio may be too low. Fibril formation requires sufficient elongational stress to deform and stretch the dispersed phase [9]. Solution: Systematically increase the take-up speed or draw ratio.

- Unfavorable Viscosity Ratio: A viscosity ratio (dispersed phase/matrix) far from unity can hinder droplet deformation [10]. Solution: Adjust processing temperature to modify the viscosity of the components.

- Coalescence: The stretched fibrils break up into droplets before solidification [9]. Solution: Increase the cooling rate to shorten the time available for break-up, or optimize the composition to reduce droplet-droplet interactions.

Problem: Phase Coarsening or Inconsistent Morphology During Reprocessing

- Issue: Phase dimensions increase or become irregular after multiple extrusion cycles (mechanical recycling).

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Polymer Degradation: Chain scission during thermal processing can alter viscosity and interfacial tension, leading to coalescence [11]. Solution: Characterize molecular weight changes via Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC). Consider using stabilizers.

- Cross-Linking: In some blends, cross-linking can occur, which may help preserve morphology but also change rheological behavior [11]. Solution: Monitor complex viscosity via rheology; a significant increase suggests cross-linking.

Problem: Poor Interfacial Adhesion and Mechanical Failure

- Issue: The blend exhibits brittle behavior or delamination, indicating weak adhesion between the phases.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Lack of Compatibility: Immiscible polymers have high interfacial tension [12]. Solution: Incorporate a compatibilizer (e.g., PP-g-MA for PP/PET blends) to reduce interfacial tension and improve adhesion [12].

- Insufficient Dispersion: The initial dispersed phase size is too large [12]. Solution: Optimize the initial melt mixing conditions (screw speed, shear rate) to create a finer initial morphology.

Quantitative Data for Morphology Prediction

The table below summarizes key parameters and their typical impact on phase dimensions and morphology, based on experimental data [13] [12].

Table 1: Influence of Processing and Material Parameters on Phase Morphology

| Parameter | Effect on Phase Dimensions | Effect on Morphology Type | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capillary Number (Ca) | Rapid decrease during initial "sheeting" stage; final dimensions often become independent of Ca at high values [13]. | Low Ca: Promotes droplet formation. High Ca (>1): Promotes stable fiber/thread formation [13]. | [13] |

| Viscosity Ratio | Influences the ease of droplet deformation and breakup. A ratio closer to 1 is generally favorable for fibrillation [10]. | Determines whether the dispersed phase deforms into fibrils or remains as droplets [10]. | [10] |

| Compatibilizer Addition | Dramatically reduces the size of the dispersed phase in the isotropic state (e.g., from several microns to sub-micron) [12]. | Improves adhesion, prevents coalescence, but can lead to shorter fibrils after drawing due to reduced initial droplet size [12]. | [12] |

| Take-up Velocity / Draw Ratio | Diameter of the dispersed phase decreases with increasing take-up speed due to higher elongational stress [9]. | Promotes transformation from spherical/ellipsoidal domains to long continuous nanofibrils [9]. | [9] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the "sheeting mechanism" often reported in initial blending stages? The sheeting mechanism describes the initial, rapid morphology development where polymer pellets are deformed into irregular, sheet-like or striated structures. This occurs concurrently with melting in the early stages of mixing in extruders or batch mixers. These sheets subsequently break up into threads or droplets, largely determining the final phase dimensions [13].

FAQ 2: Why does my compatibilized blend sometimes show inferior mechanical properties after drawing compared to the uncompatibilized one? This counterintuitive result is often related to fibril morphology. While a compatibilizer creates a finer initial dispersion, it also coats the dispersed phase particles, preventing them from coalescing during the drawing process. This can result in shorter microfibrils with a lower aspect ratio in the compatibilized blend compared to the long, continuous microfibrils that can form in an uncompatibilized blend, leading to less effective reinforcement [12].

FAQ 3: How does the viscosity ratio affect the morphology of my blend? The viscosity ratio (typically defined as viscosity of the dispersed phase divided by viscosity of the matrix) is a critical parameter. A ratio close to 1 generally facilitates the deformation and fibrillation of the dispersed phase under elongational flow. Ratios much larger or smaller than 1 can make it difficult to stretch the dispersed phase, favoring the formation of a droplet-matrix morphology instead of a fibrillar one [10].

FAQ 4: Can I predict the final morphology of my blend before experimentation? While predictive models exist, they often require complex calculations. However, recent advances use machine learning. For instance, a Support Vector Machine (SVM) model has been developed with high accuracy to predict the morphology (e.g., column, hole, island) of spin-coated PS/PMMA blend thin films based on parameters like weight fraction, molecular weight, and substrate surface energy [14]. Such data-driven approaches are becoming increasingly valuable for guiding experimental design.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Tracking Morphology Development Along a Spinning Line

Objective: To capture and analyze the evolution of the dispersed phase morphology at different stages of the melt spinning process [9].

Materials and Equipment:

- Immiscible polymer pellets (Components A and B)

- Twin-screw extruder with a spin pack

- Melt spinning unit

- Self-made fiber capturing device (or a high-speed quenching bath that can be positioned at different points along the spin line)

- Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

- Selective solvents for etching one polymer component

Methodology:

- Blend Preparation: Dry blend the polymers at the desired weight ratio and feed into the extruder.

- Extrusion & Spinning: Process the blend through the extruder. Set a constant mass throughput and a chosen take-up velocity.

- Sample Collection: Use the capturing device to quench and collect running filament samples at various distances from the spinneret (e.g., immediately at the die, before the solidification point, and at the take-up godet).

- Sample Preparation:

- For cross-sectional analysis, freeze the collected filaments in liquid nitrogen and fracture them.

- For dispersed phase analysis, immerse the samples in a selective solvent to dissolve and remove the matrix polymer, leaving the dispersed phase structure intact.

- Morphology Characterization: sputter-coat the samples with gold and analyze them under SEM. Measure the diameter and aspect ratio of the dispersed phase at each sampling point.

Expected Outcome: A detailed profile of morphology development, typically showing the deformation of the initial dispersed phase from spherical/elliptical domains into long, continuous fibrils as the elongational stress increases along the spinning line [9].

Protocol 2: Assessing the Impact of Multiple Melt Processing Cycles

Objective: To simulate mechanical recycling and evaluate the effect of repeated extrusion on the morphology and properties of a polymer blend [11].

Materials and Equipment:

- Polymer blend pellets

- Laboratory-scale twin-screw extruder

- Injection molding machine

- Rheometer, Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC), Tensile Tester

Methodology:

- Baseline Processing: Subject the virgin blend to a single extrusion cycle, followed by injection molding to create standard test specimens (Cycle 0).

- Reprocessing: Grind the test specimens and subject the material to subsequent extrusion and injection molding cycles (e.g., up to 10 cycles).

- Characterization After Each Cycle:

- Rheological Properties: Perform oscillatory shear tests to measure complex viscosity. An increase may indicate cross-linking, while a decrease suggests chain scission [11].

- Molecular Weight: Use GPC to track changes in number-average and weight-average molecular weight.

- Thermal Stability: Conduct TGA to monitor changes in the thermal degradation onset temperature (T5%).

- Mechanical Properties: Perform tensile tests to measure Young's modulus, tensile strength, and elongation at break.

- Morphology: Analyze the fracture surfaces of tensile bars using SEM to observe phase dimensions and interfacial adhesion.

Expected Outcome: Understanding the stability of the blend morphology and properties over multiple processing cycles. A balance between chain scission (reducing molecular weight) and cross-linking can lead to complex changes in rheology and mechanics, with ductility often being the most sensitive property to degradation [11].

Essential Diagrams and Workflows

Diagram 1: Morphology Development Pathways

Morphology Development Pathways: This flowchart outlines the key morphological states during processing, highlighting the critical role of the capillary number (Ca) and elongational flow in determining the final structure.

Diagram 2: Melt Spinning & Analysis Workflow

Melt Spinning & Analysis Workflow: This diagram visualizes a standardized experimental protocol for investigating morphology development in polymer blend fibers, from material selection to data correlation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Polymer Blend Morphology Studies

| Item | Function in Experiment | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Compatibilizer | Reduces interfacial tension between immiscible phases, improves dispersion, and enhances adhesion. | PP-g-MA (Maleic Anhydride grafted Polypropylene): Commonly used for blends involving PP and polar polymers like PET or PA [12]. |

| Selective Solvent | Used for selective etching of one polymer phase to isolate and visualize the morphology of the other phase via SEM. | Tetrahydrofuran (THF), Xylene, N-butanol: Choice depends on the chemical resistance of the polymer components [15] [9]. |

| Thermal Stabilizer | Minimizes polymer degradation (chain scission or cross-linking) during multiple melt processing cycles. | Phosphites/Phenolics (e.g., Irganox, Irgafos): Crucial for reprocessing studies to isolate morphology effects from degradation effects [11]. |

| Rheology Modifier | Used to adjust the viscosity ratio of the blend components to a favorable range for target morphology. | Processing Oil, Low-MW polymer grade: Adjusting processing temperature is another common method to modify viscosity [10]. |

The Impact of Thermal History on Crystallinity and Amorphous Region Dynamics

FAQs: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: How does repeated thermal processing, such as multiple extrusion cycles, affect a biodegradable polymer blend's properties? Repeated mechanical recycling via extrusion has a measurable but complex impact on polymer blends. Research on a commercial polylactic acid (PLA) and polybutylene succinate (PBS) blend subjected to ten extrusion cycles showed a balance between chain scission and cross-linking. While the average molecular weight decreased by approximately 8.4%, cross-linking helped preserve mechanical properties, with only a 53% decrease in ductility and a minor 2.3% decline in the initial thermal decomposition temperature (T5% onset). The complex viscosity of the blend increased over the cycles, further evidencing the cross-linking phenomenon [11].

FAQ 2: My DSC thermogram shows multiple thermal anomalies. Could these be related to amorphous region dynamics? Yes. While a single glass transition (α-relaxation) is typical, some homopolymers can exhibit a second, lower-temperature thermal anomaly attributable to β-relaxation. This is distinct from having two separate glass transitions. For instance, in poly(diethyl fumarate) (PDEF), β-relaxation is detectable via DSC and is linked to very local molecular motions within the rigid amorphous structure. This β-relaxation can influence mechanical properties, such as brittleness, even at temperatures above its occurrence [16].

FAQ 3: What is the most accurate method for calculating the degree of crystallinity from DSC data? The conventional method of drawing a linear baseline from the onset to the end of melting and using the enthalpy of a 100% crystalline polymer at its equilibrium melting point can be misleading. The recommended First Law procedure calculates the residual enthalpy of fusion at a lower temperature (T1, e.g., ambient or just above Tg). This accounts for concurrent recrystallization and melting during heating and provides a crystallinity value representative of the material at its use temperature, showing better agreement with other methods like density measurement [17].

FAQ 4: How does the addition of a compatibilizer influence the recycling of immiscible polymer blends? The presence of a compatibilizer can significantly mitigate property degradation during recycling. In blends of thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) and polypropylene (PP), multiple melting-recycling cycles led to significant "differentiation effects" and property changes. However, the addition of maleic anhydride-grafted PP (MA) as a compatibilizer reduced this overall differentiation effect, helping to stabilize the blend's properties against the detrimental impacts of repeated thermal processing [3].

FAQ 5: What is the "rigid amorphous fraction" and how is it detected? In semi-crystalline polymers, a portion of the amorphous phase can be constrained by the crystalline lamellae and does not contribute to the glass transition. This is the rigid amorphous fraction. It can be identified via broadband dielectric spectroscopy as a separate α'-relaxation process, which is distinct from the primary α-relaxation of the mobile amorphous phase. This α'-relaxation is temperature and composition-dependent and is attributed to the molecular motions in the amorphous regions located between adjacent lamellae within crystal stacks [18].

Table 1: Impact of Multiple Extrusion Cycles on a PLA/PBS Blend's Properties [11]

| Property | Impact of 10 Extrusion Cycles | Attributed Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Number Average Molecular Weight | Decreased by ~8.4% | Molecular chain scission |

| Ductility (Strain at Break) | Decreased by 53% | Molecular degradation |

| Initial Thermal Decomposition Temp (T5%) | Decreased by 2.3% | Reduction in thermal stability |

| Complex Viscosity | Increased | Cross-linking phenomenon |

| Overall Mechanical Properties | Largely maintained | Balance of chain scission and cross-linking |

Table 2: Comparison of Crystallinity Measurement Techniques [17] [19]

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DSC (First Law Procedure) | Measures residual enthalpy of fusion at temperature T1 | Accounts for specific heat changes; provides crystallinity at use temperature | Requires careful baseline correction and known Cp of amorphous phase |

| Conventional DSC (ΔHf/ΔHf°) | Measures enthalpy of fusion at Tm relative to 100% crystal | Simple and widely used | Ignores recrystallization during heating; can be inaccurate |

| Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD) | Measures scattering from crystalline planes | Robust for quantifying crystalline/amorphous ratios; not limited by drug loading | Can be affected by the presence of other excipients |

| Solid-state NMR (SSNMR) | Measures local molecular environments | Provides quantitative data and insight into crystal quality | Complex data analysis; requires specialized expertise |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Simulating Mechanical Recycling via Repeated Extrusion

This protocol assesses the impact of multiple melt-processing cycles on a polymer's properties, simulating mechanical recycling [11].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Polymer Material: Commercial biodegradable polymer blend (e.g., PLA/PBS blend).

- Extruder: Twin-screw extruder with temperature control.

- Injection Molding Machine: To standardize sample shape after each extrusion.

Methodology:

- Preparation: Dry the polymer granules to remove moisture.

- Initial Extrusion: Process the virgin material through the extruder at a specified temperature profile suitable for the polymer blend. Pelletize the extrudate.

- Reprocessing Cycles: Subject the pelleted material to repeated cycles of extrusion (e.g., 10 cycles). Use consistent processing parameters (temperature, screw speed) for all cycles.

- Sample Preparation: After each extrusion cycle, use injection molding to create standardized test specimens (e.g., for tensile testing, impact bars).

- Characterization: After designated cycles (e.g., 1, 5, 10), characterize the samples.

- Rheological Properties: Measure complex viscosity via oscillatory rheometry.

- Thermal Properties: Use TGA for thermal stability (e.g., T5% onset temperature) and DSC for thermal transitions and crystallinity.

- Mechanical Properties: Perform tensile tests to determine stress at break, strain at break (ductility), and elastic modulus.

- Molecular Weight: Use Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) to track changes in molecular weight distribution.

Protocol: Accurate Crystallinity Measurement via DSC Using the First Law Method

This protocol details the correct procedure for determining the degree of crystallinity at a relevant use temperature [17].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- DSC Instrument: Calibrated for temperature and enthalpy.

- Reference Materials: Indium for calibration.

- Hermetic Sample Pans: To prevent sample degradation.

Methodology:

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate the DSC using a known standard like indium.

- Sample Preparation: Place a small, precisely weighed sample (3-5 mg) into a hermetic pan.

- DSC Run: Heat the sample from a temperature (T1) below its glass transition to a temperature (T2) above its melting point at a controlled rate (e.g., 10°C/min). Use an empty pan as a reference.

- Data Analysis - First Law Method:

- Select T1 (e.g., room temperature or just above Tg) where the sample's crystallinity is stable and representative of its use condition.

- Select T2 just above the temperature where the last trace of crystallinity melts.

- Determine the total enthalpy change (ΔHtotal) of the sample from T1 to T2.

- Calculate the virtual enthalpy change (ΔHvirtual) for cooling the completely amorphous melt from T2 to T1 without crystallization. This requires knowledge of the specific heat capacity (Cp) of the supercooled liquid.

- The residual enthalpy of fusion at T1 is given by: ΔHf(T1) = ΔHvirtual - ΔHtotal.

- The degree of crystallinity at T1 is: Xc = ΔHf(T1) / ΔHf°(T1), where ΔHf°(T1) is the enthalpy of fusion of a 100% crystalline polymer at T1.

Protocol: Investigating Relaxation Dynamics in Amorphous Regions

This protocol uses Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) and Dielectric Spectroscopy to study molecular motions in amorphous regions, including the rigid amorphous fraction [16] [18].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Polymer Samples: Amorphous or semi-crystalline polymers (e.g., poly(fumarate)s, PHB/PVAc blends).

- DMA Instrument: Equipped with a dual cantilever or tension clamp.

- Broadband Dielectric Spectrometer: Capable of measuring a wide frequency range (e.g., 10⁻² to 10⁷ Hz).

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare rectangular specimens of precise dimensions for DMA. For dielectric spectroscopy, prepare thin films with conductive electrodes.

- DMA Measurement:

- Clamp the sample and subject it to a small sinusoidal strain at a fixed frequency (e.g., 1 Hz).

- Measure the storage modulus (E'), loss modulus (E"), and tan delta while ramping the temperature at a controlled rate (e.g., 2°C/min).

- Identify the primary α-relaxation (glass transition) peak in the E" or tan delta curve. Look for secondary, smaller β-relaxation peaks at lower temperatures.

- Dielectric Spectroscopy Measurement:

- At a fixed temperature, measure the complex permittivity over a broad frequency range.

- Repeat these frequency sweeps across a wide temperature range.

- Plot the loss tangent or dielectric loss against frequency/temperature to identify relaxation peaks (α, α', β).

- Data Analysis:

- The α-relaxation corresponds to the glass transition of the mobile amorphous fraction.

- The α'-relaxation, often observed in semi-crystalline polymers at higher frequencies/lower temperatures than the α-relaxation, is assigned to the rigid amorphous fraction constrained by crystals.

- The β-relaxation is typically a local, non-cooperative motion within the amorphous phase.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Polymer Thermal History Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Biodegradable Polymer Blends | Model system for studying recycling effects on properties | PLA (Polylactic Acid) / PBS (Polybutylene Succinate) blends [11] |

| Compatibilizer | Improves interfacial adhesion in immiscible blends, stabilizing properties during recycling | Maleic Anhydride-grafted Polypropylene (MA) [3] |

| Carbon Fiber (CF) | Reinforcing filler to enhance thermal stability and mechanical properties of polymers | Short carbon fibers in PLA matrix [20] |

| Model Polymers for Dynamics | Studying β-relaxation and local amorphous motions | Poly(diethyl fumarate) - PDEF [16] |

| Miscible Blend Components | Investigating dynamics in amorphous/crystalline blends | Poly(hydroxy butyrate) - PHB / Poly(vinyl acetate) - PVAc [18] |

Experimental Workflow and Property Relationships

Diagram 1: Thermal processing impact on polymer structure and properties.

Diagram 2: How polymer structural elements influence final material properties.

Advanced Techniques for Analyzing Melt-Induced Property Changes

FAQs: Core Techniques and Melt Cycle Fundamentals

Q1: How do DSC and TGA provide complementary information for analyzing melt cycles?

DSC and TGA are foundational techniques in thermal analysis that provide different but complementary data. DSC measures heat flow into or out of a sample, capturing thermal events like melting points, glass transitions, crystallization, and curing reactions. In contrast, TGA measures changes in a sample's mass as a function of temperature, providing data on thermal stability, decomposition temperatures, moisture content, and composition analysis [21].

During melt cycle analysis, this combination is powerful. For instance, DSC can detect the melting temperature and enthalpy of fusion of a polymer, while TGA can determine if that same polymer undergoes decomposition or loses volatiles (like water or solvents) simultaneously. One study on amoxicillin trihydrate demonstrated this synergy: a DSC endothermic peak at 107°C was confirmed by TGA-FT-IR to be water evaporation and not melting, as it was associated with a 12.9% mass loss [22].

Q2: Why is rheology critical for understanding polymer behavior during multiple processing cycles?

While thermal analysis reveals stability and transitions, rheology characterizes the flow and deformation of materials, which is directly relevant to processing behavior. The melt flow index (MFI) or melt flow rate (MFR) is a common but limited quality control measure [23].

Rheology becomes essential when shear viscosity flow curves are insufficient. In processes like blow molding, the material experiences extensional flow. Research has shown that two batches of ABS material can have identical shear viscosity curves but vastly different extensional viscosities, leading to processing failures like blow breakage in one batch [23]. Furthermore, multiple melt cycles can significantly alter melt viscosity. Studies on polyamides have shown that thermal cycling during processing can lead to a drastic increase in viscosity, which can prevent proper impregnation of fibers in composite manufacturing [7].

Q3: How does FT-IR enhance the capabilities of TGA in degradation studies?

Coupled TGA-FT-IR is a powerful hyphenated technique that identifies the volatile products evolved during thermal degradation. While TGA quantifies the mass loss, FT-IR provides the chemical identity of the gases being released [22] [21].

This is crucial for melt cycle analysis to understand degradation mechanisms. For example, in the amoxicillin study, TGA showed a mass loss step at 185°C. The coupled FT-IR identified that degradation began with the release of carbon dioxide and ammonia. At higher temperatures (294°C), the FT-IR spectrum additionally detected -C-H bonds and aromatics, providing a detailed picture of the breakdown pathway [22].

Q4: What common property changes are induced by repeated melt cycles?

Multiple melting-recycling cycles can significantly alter a polymer's properties, a phenomenon often referred to as thermo-oxidative degradation. Key changes include [7] [3]:

- Increased Melt Viscosity: A drastic increase in viscosity is commonly observed, which can hinder further processing [7].

- Changes in Thermal Properties: Decreasing melting temperatures and the onset of decomposition can be detected by DSC and TGA [7].

- Reduced Molar Mass: Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) often shows a decrease in molar mass and a broadening of the molecular weight distribution after repeated processing in an oxidative atmosphere [7].

- Embrittlement: Tensile tests often show a reduction in elongation at break, making the material more brittle [3].

- Phase Separation: In polymer blends like thermoplastic polyurethane and polypropylene (T/P), repeated cycles can lead to significant phase separation, which can be mitigated by using compatibilizers [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

DSC: No Clear Melting Endotherm or Unusual Glass Transition

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No clear melting peak | Sample has degraded; overly rapid heating rate | Run TGA to check for decomposition. Use a standard heating rate (e.g., 10°C/min) [21]. |

| Glass transition (Tg) is weak/noisy | Sample size is too small; sensitivity is low | Increase sample mass within the recommended range (1-10 mg). Ensure proper contact between pan and sample [21]. |

| Multiple melting peaks | Polymer has different crystal structures or morphologies; thermal history | Develop a standardized thermal protocol (heating-cooling-reheating) to erase previous history and check for consistency [24]. |

| Irreproducible enthalpy values | Sample mass is inconsistent; pan is not hermetically sealed | Use a precision microbalance. Ensure pans are properly crimped. For volatile samples, use high-pressure pans [21]. |

TGA: Baseline Drift and Erratic Mass Loss

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Significant baseline drift | Buoyancy effects; gas convection; thermal expansion of support | Perform and subtract a blank baseline measurement under identical conditions [25]. |

| Mass loss occurs at unexpected temperatures | Crucible type and atmosphere are influential | Use open crucibles for better gas exchange. Control atmosphere (N₂ for inert, air/O₂ for oxidative) [22] [25]. |

| Overlapping decomposition steps | Heating rate is too fast | Slow down the heating rate (e.g., from 20 K/min to 10 K/min) to better separate mass loss events [25]. |

| Results not reproducible | Sample mass too large; poor gas flow control | Use a small, representative sample (1-20 mg). Ensure consistent gas flow rates throughout the experiment [25] [21]. |

Rheology: Inconsistent Viscosity Data

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Viscosity is higher than expected | Polymer degradation has increased molecular weight | Confirm with GPC. Use antioxidants to suppress thermo-oxidative degradation [7]. |

| Poor reproducibility between tests | Sample history and loading conditions are not consistent | Develop a strict protocol for sample preparation and loading into the rheometer. Pre-shear the sample to create a uniform history [23]. |

| Flow curve doesn't match processing behavior | Only shear viscosity was measured for an extensional process | Use a capillary rheometer with a zero-length (orifice) die to measure extensional viscosity for processes like blow molding and film stretching [23]. |

| Data points are noisy | Sample has dried out or degraded in the instrument; edge fracture | Use a solvent trap to prevent evaporation. For time sweeps, ensure the selected strain is within the linear viscoelastic region. |

FT-IR: Unidentifiable Bands in Evolved Gas Analysis

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Weak signal from evolved gases | Transfer line temperature is too low, causing condensation | Heat the transfer line temperature above the condensation point of the evolved gases [22]. |

| Bands are saturated or too strong | Concentration of evolved gas is too high | Dilute the gas stream or reduce the sample mass in the coupled TGA [22]. |

| Cannot match spectra to known compounds | Spectral library is insufficient; multiple gases are co-eluting | Use specialized polymer degradation libraries. Analyze the TGA mass loss steps to narrow down potential compounds [22] [26]. |

Experimental Protocols for Melt Cycle Analysis

Protocol: Simulating Thermal Cycling with DSC and TGA

Objective: To evaluate the thermal stability and oxidative resistance of a polymer (e.g., Polyamide 6) subjected to repeated heat cycles.

Materials:

- Polymer sample (e.g., PA6 pellets)

- Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC)

- Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA)

- Analytical balance

- Antioxidants (e.g., phosphorous-based P-EPQ) (optional) [7]

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Dry all samples in an oven at 80°C for 24 hours to remove moisture. For stabilized samples, compound the polymer with an antioxidant (e.g., 0.1-0.5 wt%) [7].

- Initial Characterization:

- Thermal Cycling:

- DSC Cycling: Program the DSC to simulate multiple processing cycles: Heat from 30°C to Tm+30°C, hold for 5 minutes (simulating processing dwell time), cool rapidly to 30°C, hold for 2 minutes, and repeat for 3-5 cycles [7].

- Isothermal TGA: Hold samples isothermally in the TGA at a temperature just above the melting point (e.g., 250°C for PA6) in an air atmosphere for a set time (e.g., 60 minutes) to simulate extended exposure to processing temperatures. Monitor mass loss over time [7].

- Post-Cycling Analysis:

- After cycling in the DSC, run a final heating scan identical to the initial one. Compare the Tm and enthalpy to quantify degradation.

- Analyze the TGA data for the onset temperature of decomposition and the percentage of residue after cycling.

Protocol: Analyzing Flow Behavior Degradation with Rheology

Objective: To monitor changes in shear and extensional viscosity after multiple extrusion cycles.

Materials:

- Twin-bore capillary rheometer (e.g., Rosand) [23]

- Polymer granules

- Drying oven

Methodology:

- Sample Processing: Subject the polymer to multiple passes through a twin-screw extruder or a compounder to simulate recycling. Collect samples after each pass (1st, 3rd, 5th cycle).

- Shear Viscosity Measurement:

- Load the sample into the capillary rheometer equipped with a long die (e.g., 16:1 L/D ratio).

- Perform a constant shear rate test at the relevant processing temperature (e.g., 210°C for ABS). Generate a flow curve (viscosity vs. shear rate) for each cycled sample [23].

- Extensional Viscosity Measurement:

- Using the same capillary rheometer and a zero-length (orifice) die, perform an identical test.

- Use the Cogswell model to calculate the extensional viscosity from the pressure drop through the orifice die [23].

- Data Analysis:

- Overlay the shear and extensional viscosity curves for all samples.

- Note any significant increase in low-shear-rate viscosity (indicating cross-linking) or decrease (indicating chain scission).

- Correlate changes in extensional viscosity with the performance in relevant processes (e.g., blow molding).

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Diagram 1: Integrated Workflow for Melt Cycle Analysis. This diagram outlines the sequential process of preparing a polymer sample, subjecting it to multiple melt cycles, and then characterizing it using a suite of complementary techniques to synthesize a complete picture of property changes.

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting with Extensional Rheology. This logic flow demonstrates a common troubleshooting path where conventional shear viscosity analysis fails to explain processing issues, necessitating the measurement of extensional viscosity.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in Melt Cycle Analysis | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphorous-based Antioxidant (e.g., P-EPQ) | Suppresses thermo-oxidative degradation during high-temperature exposure, helping to maintain initial polymer properties like molar mass and viscosity [7]. | Effectiveness can decrease with increasing dwell times at high temperatures [7]. |

| Inert Gas (Nitrogen, N₂) | Creates an oxygen-free atmosphere in TGA, DSC, or rheometry to study pure thermal degradation without oxidation [25] [21]. | Essential for establishing baseline thermal stability before studying oxidative effects. |

| Reactive Gas (Synthetic Air, O₂) | Used in TGA or DSC to intentionally study the oxidative stability and degradation pathways of polymers [25] [21]. | Allows for measurement of the Oxidation Induction Time (OIT). |

| Compatibilizer (e.g., Maleic Anhydride grafted PP) | Improves interfacial adhesion in polymer blends (e.g., TPU/PP) during recycling, mitigating phase separation and property loss over multiple cycles [3]. | Selection is specific to the polymer blend system. |

| Calibration Standards (for GPC) | Provide reference for accurate molecular weight determination via Gel Permeation Chromatography, essential for quantifying chain scission or cross-linking [27]. | Must be structurally similar to the analyzed polymer for accurate results [27]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common mistakes that cause MD simulations of polymers to fail? Several common pitfalls can undermine MD simulations. These include poor preparation of starting structures (e.g., missing atoms or incorrect protonation states), using an incorrect time step that leads to instability, neglecting artefacts caused by Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC) during analysis, and inadequate minimization and equilibration before production runs. These errors can cause simulations to crash or produce physically unrealistic results [28].

Q2: My simulation failed with an "Out of memory" error. What should I do? This error occurs when the program attempts to allocate more memory than is available. Solutions include reducing the number of atoms selected for analysis, shortening the trajectory file being processed, or using a computer with more memory. The computational cost of various activities scales with the number of atoms (N), so it is crucial to consider the underlying algorithm's demands [29].

Q3: How do I handle a "Residue not found in residue topology database" error in GROMACS? This error means the force field you selected does not contain an entry for the residue "XXX". This is common when simulating non-standard molecules. Solutions include checking if the residue exists under a different name in the database, manually parameterizing the residue, finding a pre-existing topology file for the molecule, or using a different force field that includes the necessary parameters [29].

Q4: Why is proper equilibration critical in MD simulations of polymer melts? Equilibration allows temperature, pressure, and density to stabilize before production runs begin. In polymer melts, this step is vital for achieving the correct thermodynamic ensemble. If skipped or shortened, the system will not represent realistic conditions, and subsequent measurements of properties like diffusion, binding, or conformational stability will be unreliable [28].

Q5: How can I ensure my simulation results are statistically meaningful? A single trajectory is often insufficient due to the vast conformational space of polymers. To obtain statistically meaningful results, you should perform multiple independent simulation replicates with different initial velocities. This approach helps ensure that observed behaviors are representative and not artefacts of being trapped in a local energy minimum [28].

Troubleshooting Guide

This guide addresses specific issues you might encounter when using MD simulations to study polymers, particularly in the context of melt cycles and property prediction.

Table 1: Common Simulation Errors and Solutions

| Error / Issue | Probable Cause | Solution | Relevant Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation crash during energy minimization | Poor starting structure with steric clashes or high-energy bonds [28]. | Perform thorough energy minimization until convergence. Use algorithms like steepest descent or conjugate gradient to relax the structure [28]. | Essential for relaxing high-energy regions in recycled polymer blends before MD [3]. |

| Unstable simulation (blows up) | Incorrect time step is too large, causing numerical instability [28]. | Reduce the time step (e.g., to 1-2 fs). Use constraints for bonds involving hydrogen atoms [28]. | Critical for maintaining stability during long-scale simulations of polymer melt dynamics. |

| "Atom index in position_restraints out of bounds" | Position restraint files are included in the topology in the wrong order [29]. | Ensure #include directives for position restraints are placed immediately after the corresponding [moleculetype] directive [29]. |

Important when applying restraints to specific particles or polymers in a composite. |

| "Found a second defaults directive" | The [defaults] directive appears more than once in the topology or force field files [29]. |

Ensure [defaults] appears only once, typically in the main force field file (forcefield.itp). Comment out duplicate entries [29]. |

Necessary for maintaining consistency when simulating systems with multiple components. |

| Misleading analysis results (e.g., RMSD) | Failure to correct for Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC) before analysis [28]. | Use tools like gmx trjconv (GROMACS) with the -pbc mol or -center options to make molecules whole and remove jumps across the box [28]. |

Crucial for accurate measurement of chain conformation and dispersion in polymer nanocomposites (PNCs) [30]. |

Table 2: Force Field and Parameterization Issues

| Problem | Impact on Simulation | Correction | Thesis Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Using an unsuitable force field | Inaccurate energetics, incorrect conformations, unstable dynamics [28]. | Select a force field parameterized for your specific polymer system (e.g., CGenFF for organics, CHARMM36m for proteins) [28]. | Using a force field not validated for a specific polymer (e.g., polyurethane) can lead to incorrect predictions of melt behavior [3]. |

| Mixing incompatible force fields | Unphysical interactions due to differing functional forms, charges, or combination rules [28]. | Use parameter sets explicitly designed to work together (e.g., GAFF2 with AMBER ff14SB). Avoid ad-hoc mixing [28]. | Critical when simulating polymer blends (e.g., TPU/PP) where components have different polarities [3]. |

| Missing parameters for a ligand or residue | Simulation cannot run; "residue not found" error [29]. | Parameterize the molecule yourself, find a pre-existing topology, or use a program like x2top or ACPYPE [29]. |

Essential for incorporating compatibilizers (e.g., maleic anhydride grafted PP) into blend simulations [3]. |

Experimental Protocols from Literature

The following detailed methodologies are adapted from recent research and can serve as a guide for setting up simulations related to polymer melts and composites.

Protocol 1: Investigating Relaxation-Enhanced Polymer Nanocomposites

This protocol is based on a study designing low-viscosity, high-strength polymer nanocomposites (PNCs) by engineering the polymer-filler interface [30].

- 1. System Preparation: The study utilized silica nanoparticles (NPs) with a diameter of 65 ± 10 nm. A statistical copolymer, poly(styrene-ran-4-hydroxystyrene) [P(S-ran-HS)], was used to create bound loops on the NP surface. The hydroxyl groups in HS form strong H-bonds with silanol groups on the silica, pinning the polymer and creating loops.

- 2. Building the Interface: Composites of silica NPs and P(S-ran-HS) were prepared by casting from methyl ethyl ketone and dried. The composite was annealed at 150 °C (Tg + 50 °C) for 24 hours under vacuum to promote polymer adsorption onto the NP surface.

- 3. Creating the Model System: Solvent leaching with chloroform was used to remove non-attached polymer chains, leaving only the bound polymer loops on the silica NPs (BL–SiOx NPs). The thickness of this bound loop layer (hBL) was controlled by the mole fraction of HS (fHS) in the copolymer.

- 4. Incorporation into Matrix & Analysis: The BL–SiOx NPs were dispersed in a toluene solution of polystyrene (PS) matrix (Mw = 370 kg mol-1) and dried to form the final PNC. Key characterization techniques included:

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): To confirm the formation of the bound loop layer and assess NP dispersion in the matrix.

- Solid-state ¹H-NMR: To directly probe the molecular mobility of polymers in the PNC melt, showing enhanced relaxation in the loop-based system.

- Rheology: To measure the shifting factors (aT) and moduli, demonstrating reduced viscosity and improved flow in the relaxation-enhanced PNCs [30].

Protocol 2: Simulating the Effects of Multiple Melt-Recycling Cycles

This protocol outlines an experimental approach to study the degradation of polymer blends under repeated processing, which can be modeled using MD [3].

- 1. Materials & Blending: The study used blends of Thermoplastic Polyurethane (T) and Polypropylene (P), with Maleic Anhydride grafted Polypropylene (MA) as a compatibilizer. Blends with ratios like 90/10/0, 70/30/0, 50/50/0, and their compatibilized counterparts (e.g., 90/10/5) were prepared.

- 2. Simulating Melt-Recycling Cycles:

- Materials were trimmed into small pieces, mixed, and hot-pressed to form initial blends (1st cycle).

- To simulate a recycling step, the samples were subjected to a mechanical fracture (e.g., tensile testing until break) and then the fragments were hot-pressed again. This combined process (fracture + hot-pressing) defined one recycling cycle, creating "post-2nd-recycling" and "post-3rd-recycling" groups.

- Hot-pressing was conducted at temperatures ranging from 165°C to 200°C (depending on P content) at a pressure of 20 MPa for 5 minutes.

- 3. Property Evaluation:

- Tensile Testing: Measured stress and strain at break/yield to quantify mechanical degradation.

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): Observed fracture morphology and phase separation to assess the compatibilizing effect of MA.

- Thermal Analysis: Techniques like TGA and DSC were used to study thermal stability and transitions [3].

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: MD Simulation Workflow for Polymer Properties

MD Simulation Workflow

Diagram 2: Polymer Melt Recycling Simulation

Polymer Melt Recycling Simulation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Polymer Nanocomposite Modeling

| Item | Function / Relevance in Research | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Silica Nanoparticles (NPs) | Common filler used to enhance mechanical properties and modify relaxation dynamics in polymer nanocomposites (PNCs). | 65 nm diameter silica NPs were used as the core filler to study interfacial polymer dynamics [30]. |

| Functional Copolymers | Used to engineer the polymer-filler interface. Specific comonomers can anchor the chain to the surface, creating bound loops. | Poly(styrene-ran-4-hydroxystyrene) was used, where 4-hydroxystyrene anchors to silica, forming relaxed PS loops [30]. |

| Compatibilizers | Agents that improve adhesion between immiscible polymer phases, crucial for simulating and creating stable polymer blends. | Maleic Anhydride grafted Polypropylene (MA) was used to mitigate phase separation in Thermoplastic Polyurethane/Polypropylene (T/P) blends [3]. |

| Polymer Matrices | The bulk material in which fillers are dispersed. Common examples include polystyrene (PS) and thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU). | A PS matrix (Mw = 370 kg/mol) was used to study the dispersion and effect of loop-coated silica NPs [30]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Software packages like GROMACS, AMBER, and LAMMPS used to run simulations and predict material properties. | GROMACS is extensively used, and understanding its common errors is essential for successful simulation [29] [28]. |

Primitive Path Analysis (PPA) and Inverse PPA for Simulating Polymer Melt Dynamics

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How can I confirm that my iPPA transformation has preserved the topological state of the system?

Issue: Uncertainty in verifying whether the Inverse Primitive Path Analysis (iPPA) process has successfully maintained the original topology of the polymer melt.

Solution:

- Validation through Cyclic Transformation: Perform multiple PPA-iPPA cycles (e.g., 100 cycles) on a ring polymer melt and check for conservation of topological constraints. A successful preservation will show no change in the entanglement mesh structure after full cycles. [31] [32]

- Monitor Contour Length Re-introduction: The iPPA should gradually reintroduce contour length into the PPA mesh. Ensure the process is continuous and controlled, transforming the mesh back into a topologically equivalent Kremer-Grest (KG) model polymer melt without allowing chains to slip through each other. [32]

- Check for Synthesis of Model Materials: Use iPPA to generate a KG melt from a synthetic PPA mesh designed with a regular 2D cubic lattice of entanglement points. Success is confirmed if the resulting melt possesses the designed, well-controlled topology. [31] [32]

FAQ 2: My simulations show unexpected stress relaxation behavior after deformation. How can PPA/iPPA help analyze and accelerate this?

Issue: Stress relaxation in highly entangled polymer melts after fast deformation is computationally expensive to simulate and shows complex, non-affine relaxation patterns.

Solution:

- Employ PPA for Force Distribution Analysis: Use Primitive Path Analysis to investigate the force distribution along the primitive path (the tube backbone). After elongation, PPA can reveal a non-homogeneous, long-lived clustering of topological constraints (kinks/entanglement points) and sign switches in the intramolecular tension forces, which deviate from the affine deformation assumption. [33]

- Utilize iPPA for Acceleration: To reduce computational cost, apply a deformation to the PPA mesh (instead of the full KG melt) and allow for fast mesh relaxation via energy minimization. Then, use the iPPA algorithm to convert the relaxed mesh back into a KG melt state. This protocol can accelerate stress relaxation by approximately an order of magnitude in simulation time. [31] [32]

FAQ 3: What could cause a failure in generating a well-equilibrated model polymer material with a specific topology?

Issue: Standard algorithms for generating model polymer melts may not preserve topology because the initial push-off process to minimize bead overlap allows chains to pass through one another.

Solution:

- Use iPPA with a Synthetic Mesh: Start with a synthetic PPA mesh designed with the desired topology (e.g., a knitted structure with entanglements forming a regular lattice). The iPPA algorithm will gradually reintroduce contour length, transforming this mesh into a topologically equivalent KG melt without allowing chains to slip through each other during the initial equilibration phase. [32]

- Ensure Proper Force Field Switching: The iPPA method employs a continuous transformation between the PPA and KG force fields. Verify that the switching potential for intra-molecular pair interactions (e.g., using a windowed potential based on chemical distance) is correctly implemented to preserve distant self-entanglements along the chain. [32]

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: PPA-iPPA Cycle for Topology Validation

This protocol validates the topology preservation of the PPA-iPPA transformation process. [31] [32]

- Initial System Preparation: Prepare a fully equilibrated model polymer melt, such as a ring polymer melt.

- Apply Standard PPA: Transform the melt into its primitive path mesh using the PPA algorithm.

- Fix chain ends in space.

- Switch off all intrachain interactions (except within a specified window to preserve self-entanglements).

- Keep interchain excluded volume interactions.

- Minimize the system energy until chains contract to their primitive paths.

- Apply Inverse PPA (iPPA): Transform the mesh back into a melt.

- Gradually reintroduce contour length by continuously switching the force field from the PPA potential back to the full KG potential.

- Cycle the Transformation: Repeat steps 2 and 3 for multiple cycles (e.g., 100 cycles).

- Validation Check: Analyze the resulting mesh or melt after full cycles. Successful topology preservation is confirmed if the entanglement network structure remains identical to the initial state.

Protocol: Accelerated Stress Relaxation using PPA-iPPA

This protocol accelerates stress relaxation in a deformed melt, reducing computational cost. [31] [32]

- Generate Initial Melt: Start with a well-equilibrated, highly entangled polymer melt (e.g., using the Kremer-Grest bead-spring model).

- Create PPA Mesh: Apply the PPA algorithm to the initial melt to obtain its topological mesh.

- Deform the Mesh: Apply the desired mechanical deformation (e.g., isochoric elongation) directly to the PPA mesh.

- Relax the Mesh: Allow the deformed mesh to relax rapidly using energy minimization. This step is computationally cheaper than relaxing the full KG melt.

- Revert to Melt with iPPA: Use the iPPA algorithm to convert the relaxed mesh back into a topologically equivalent KG melt conformation.

- Final Analysis: The resulting KG melt is now significantly closer to a relaxed state, reducing the required subsequent simulation time for full equilibration.

Quantitative Data from PPA and Recycling Studies