Machine Learning for Polymer Process Optimization in Pharmaceutical Development: From R&D to Manufacturing

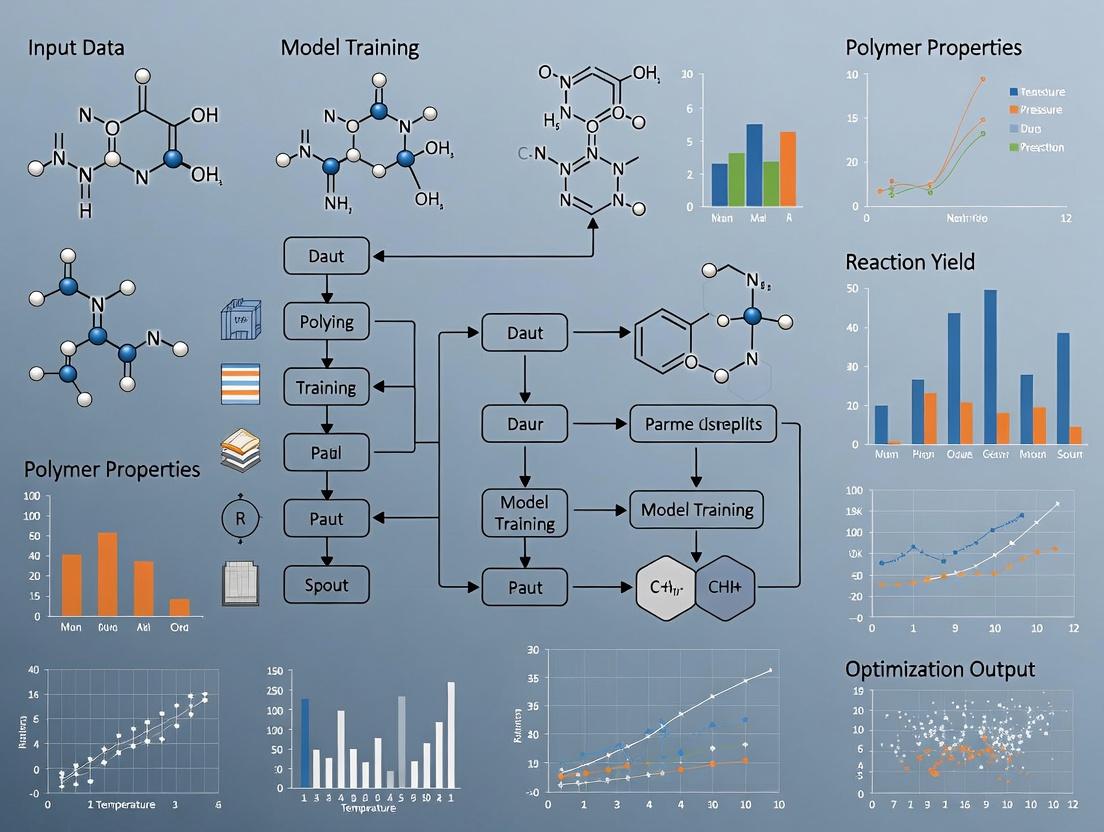

This article explores the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in optimizing polymer processes for pharmaceutical applications.

Machine Learning for Polymer Process Optimization in Pharmaceutical Development: From R&D to Manufacturing

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in optimizing polymer processes for pharmaceutical applications. It provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational concepts of polymers in drug delivery, the methodological implementation of ML models (like artificial neural networks and random forests) for predicting and controlling critical quality attributes, strategies for troubleshooting common process and data challenges, and rigorous validation frameworks for model reliability. We synthesize how ML accelerates formulation development, enhances process robustness, and paves the way for intelligent, data-driven manufacturing of advanced polymeric drug products.

Polymer Science Meets AI: Foundations for Optimizing Drug Delivery Systems

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

This support center is designed for researchers working on controlled-release formulations as part of advanced projects, such as integrating Machine Learning for Polymer Process Optimization. The guides address common experimental challenges with key polymers.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: During PLGA nanoparticle preparation using the single emulsion-solvent evaporation method, my particles are aggregating and have a very large size (>500 nm). What are the primary causes and fixes? A: Aggregation and large size typically result from insufficient stabilization or rapid solvent diffusion.

- Primary Cause 1: Inadequate concentration or choice of stabilizer (e.g., PVA).

- Fix: Increase PVA concentration (e.g., from 1% to 2-3% w/v) or ensure it is fully dissolved. Consider using alternative stabilizers like polysorbate 80 or poloxamer 407.

- Primary Cause 2: Too high polymer concentration or organic phase volume leading to high viscosity.

- Fix: Reduce PLGA concentration in the organic solvent (e.g., from 5% to 2.5% w/v) or reduce the organic-to-aqueous phase ratio.

- Primary Cause 3: Insufficient homogenization/sonication energy or time.

- Fix: Increase homogenization speed (e.g., to 15,000-20,000 rpm) or sonication amplitude/time. Ensure the probe tip is positioned correctly in the emulsion.

Q2: The drug encapsulation efficiency (EE%) in my PLGA microparticles is consistently low. How can I improve it? A: Low EE% is often due to drug partitioning into the aqueous phase during emulsion formation.

- Primary Cause 1: High hydrophilicity (high water solubility) of the drug.

- Fix: Modify the internal aqueous phase pH to decrease drug solubility (ion trapping). For basic drugs, use acidic buffer; for acidic drugs, use basic buffer.

- Fix: Use a double emulsion (W/O/W) method for hydrophilic drugs.

- Primary Cause 2: Rapid diffusion of drug into the external aqueous phase.

- Fix: Add a saturation agent (e.g., NaCl) to the external phase to reduce solubility-driven diffusion.

- Fix: Harden the particles faster by reducing the stirring volume or increasing the temperature (if drug stability allows).

Q3: My PEGylated (PLGA-PEG) nanoparticles show unexpected rapid drug release in the initial burst phase. What might be the reason? A: A high burst release from PEGylated systems often points to surface-associated drug or morphological issues.

- Primary Cause 1: Drug localization near the nanoparticle surface due to the PEGylation process.

- Fix: Optimize the nanoprecipitation or emulsion method. Adding the organic phase to the aqueous phase more slowly can promote better polymer-drug matrix formation.

- Primary Cause 2: Incomplete polymer conjugation or PEG chain entanglement, creating porous structures.

- Fix: Verify the PEG-PLGA block copolymer molecular weight and purity via GPC/NMR. Ensure complete solvent removal during fabrication.

Q4: I am observing variable release profiles between batches of the same PLGA formulation. How can I improve reproducibility? A: Batch-to-batch variability is a critical challenge for ML model training. It stems from poorly controlled process parameters.

- Primary Cause: Inconsistent process parameters (homogenization speed/time, temperature, solvent evaporation rate, phase volumes).

- Fix: Implement strict Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) with precise parameter control. Use automated equipment where possible.

- Fix: Document all parameters meticulously (ambient temperature, humidity, stirring bar shape/size) as features for potential ML analysis. This data is essential for identifying hidden correlations.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

| Symptom | Possible Polymer-Related Cause | Suggested Corrective Action | Relevant ML-Optimization Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incomplete release | PLGA molecular weight too high; crystallinity of polymer or drug. | Use lower Mw PLGA (e.g., 10-20 kDa); incorporate more hydrophilic monomers (e.g., increase PLA:GA ratio); use amorphous drug form. | Key feature for release kinetics prediction models. |

| Lag phase absent or too short | PLGA too hydrophilic (low LA:GA ratio), low Mw, or particles too small. | Use higher Mw PLGA with higher lactide:glycolide ratio (e.g., 75:25) to slow hydration. | A target variable for regression models aiming for delayed release. |

| Poor colloidal stability of PEGylated NPs | PEG chain density too low; insufficient PEG length for effective steric shielding. | Increase the PEG-PLGA copolymer ratio in the blend; use a longer PEG block (e.g., PEG-5k vs. PEG-2k). | A critical quality attribute (CQA) for ML-driven formulation optimization. |

| Irregular particle morphology | Rapid solvent evaporation/polymer precipitation. | Slow down the evaporation rate (reduced pressure, lower temperature); adjust solvent system (e.g., add dichloromethane to acetone). | Morphology is a key image-based feature for ML classification of batch quality. |

Table 1: Properties of Common Controlled Release Polymers

| Polymer | Degradation Time (Approx.) | Key Release Mechanism | Typical Mw Range (kDa) | Solubility Parameter (δ, MPa^1/2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLGA (50:50) | 1-2 months | Bulk erosion, diffusion | 10-100 | ~21.0 |

| PLGA (75:25) | 4-5 months | Bulk erosion, diffusion | 10-100 | ~20.5 |

| PEG | Non-degradable | Diffusion, swelling | 1-40 | ~20.2 |

| PLA | 12-24 months | Bulk erosion, diffusion | 10-150 | ~20.6 |

| PCL | >24 months | Diffusion, slow erosion | 10-100 | ~20.5 |

Table 2: Impact of Formulation Parameters on Nanoparticle Characteristics

| Parameter Changed | Direction of Change | Effect on Particle Size | Effect on Encapsulation Efficiency | Effect on Burst Release |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ↑ Polymer Concentration | Increase | Increases | Increases | May Increase |

| ↑ Homogenization Speed | Increase | Decreases | Variable (can increase) | Can Decrease |

| ↑ Stabilizer (PVA) Conc. | Increase | Decreases | Slight Decrease | Can Decrease |

| ↑ Aqueous Phase Volume | Increase | Decreases | Decreases | Variable |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Single Emulsion-Solvent Evaporation for PLGA Microparticles Objective: To fabricate drug-loaded PLGA microparticles with controlled size.

- Dissolution: Dissolve 100 mg PLGA (50:50, 20 kDa) and 10 mg of hydrophobic drug (e.g., Dexamethasone) in 2 mL of dichloromethane (DCM) to form the organic phase.

- Emulsification: Pour the organic phase into 100 mL of 1% (w/v) polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) aqueous solution. Immediately homogenize using a high-speed homogenizer at 12,000 rpm for 2 minutes over an ice bath to form an O/W emulsion.

- Solvent Evaporation: Transfer the emulsion to 200 mL of 0.1% PVA solution. Stir magnetically at 500 rpm for 3-4 hours at room temperature to evaporate DCM.

- Collection: Collect particles by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 15 minutes. Wash three times with distilled water to remove PVA and unencapsulated drug.

- Lyophilization: Resuspend the pellet in a minimal volume of water (or a cryoprotectant like 5% trehalose) and freeze-dry for 48 hours to obtain a free-flowing powder.

Protocol 2: Nanoprecipitation for PEG-PLGA Nanoparticles Objective: To prepare small, sterically stabilized nanoparticles.

- Organic Phase: Dissolve 20 mg of PEG-PLGA (e.g., PEG5k-PLGA20k) and 3 mg of drug in 2 mL of acetone.

- Aqueous Phase: Prepare 10 mL of deionized water or a weak buffer.

- Formation: Under moderate magnetic stirring (500-700 rpm), slowly inject the organic phase into the aqueous phase using a syringe pump (e.g., 1 mL/min).

- Solvent Removal: Stir the suspension for 2 hours to allow acetone diffusion. Optionally, place under vacuum for 30 minutes to ensure complete removal.

- Concentration/Purification: Concentrate using ultrafiltration (e.g., 100 kDa MWCO) or centrifugal filter devices. Wash with buffer to remove free drug.

Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Polymer-Based Controlled Release Research

| Item | Function/Application | Key Consideration for Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|

| PLGA (varied LA:GA ratios & Mw) | The core biodegradable matrix. Determines degradation time and release kinetics. | Source and batch variability are high. Always record inherent viscosity, end group, and manufacturer's data sheet. |

| mPEG-PLGA Diblock Copolymer | For creating sterically stabilized, long-circulating nanoparticles. | The PEG block length and coupling efficiency critically affect stealth properties. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA, 87-89% hydrolyzed) | The most common stabilizer for emulsion methods. | Degree of hydrolysis and molecular weight significantly impact particle size and stability. Use the same product lot for a study series. |

| Dichloromethane (DCM) & Acetone | Common organic solvents for polymer dissolution. | Purity and evaporation rate are critical. Use HPLC/ACS grade. Control evaporation rate during process. |

| Dialysis Membranes (Float-A-Lyzer or similar) | For in-vitro release studies under sink conditions. | Molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) must be appropriate (typically 3.5-14 kDa). Pre-treatment is essential. |

| Polysorbate 80 (Tween 80) | Alternative surfactant/stabilizer, also used in release media for sink conditions. | Can affect drug partitioning. Concentration must be standardized. |

| Trehalose or Sucrose | Cryoprotectant for lyophilization of nanoparticle dispersions. | Prevents aggregation during freeze-drying. Critical for long-term storage stability. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) with Azide | Standard release medium for in-vitro testing. | pH (7.4) and ionic strength must be controlled. Sodium azide (0.02% w/v) prevents microbial growth. |

Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) and Quality Attributes (CQAs) in Polymer Processing

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

This support center addresses common experimental challenges in defining CPPs and CQAs for polymer processing within machine learning (ML) optimization research. The guidance links specific process upsets to their impact on quality and data integrity for ML model training.

Troubleshooting Guide

Issue 1: Inconsistent Polymer Melt Viscosity During Extrusion

- Observed Symptom: Fluctuating die pressure or motor torque, leading to variable strand diameter.

- Potential CPP Deviation: Barrel temperature profiles (Zones 1-4), screw speed, or feedstock moisture content.

- Impact on CQA: Alters crystallinity (CQA), molecular weight distribution (CQA), and ultimately tensile strength (CQA).

- ML Data Impact: Introduces noise and non-stationarity into time-series sensor data, compromising model predictions.

- Corrective Action: Calibrate thermocouples, pre-dry polymer resin to a specified moisture content (e.g., <0.05%), and verify screw speed controller PID settings.

Issue 2: Poor Dispersion of Nanofiller in Composite Film

- Observed Symptom: Agglomerates visible under SEM, leading to poor barrier properties.

- Potential CPP Deviation: Insufficient shear mixing (screw design/speed), incorrect compatibilizer ratio, or feed rate inconsistency.

- Impact on CQA: Compromises film uniformity, optical clarity, and gas permeability (CQAs).

- ML Data Impact: Creates misleading correlations between simple CPPs (like screw speed) and CQAs if mixing efficacy is not directly measured.

- Corrective Action: Implement a masterbatch step, optimize screw design for distributive mixing, and use in-line rheometry to monitor dispersion quality directly.

Issue 3: Batch-to-Batch Variability in Drug-Eluting Implant Properties

- Observed Symptom: In vitro release profile does not meet specification.

- Potential CPP Deviation: Degradation during processing (temperature/time), inhomogeneous drug-polymer blending, or injection molding pack/hold pressure.

- Impact on CQA: Directly affects drug release kinetics (Critical Quality Attribute - CQA) and device mechanical integrity.

- ML Data Impact: Limits the generalizability of an ML model trained on a single batch or small dataset.

- Corrective Action: Incorporate real-time UV/Vis or NIR probes to monitor blend homogeneity. Use Design of Experiments (DoE) to define safe processing windows for ML training data generation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do I initially identify which process parameters are critical (CPPs) for my ML model? A: Start with a risk assessment (e.g., Ishikawa diagram) and prior knowledge. Then, conduct a screening Design of Experiments (DoE), such as a Plackett-Burman or Fractional Factorial design. Parameters with a statistically significant (p < 0.05) effect on a CQA are candidate CPPs. Your ML feature selection algorithm (e.g., LASSO, Random Forest importance) will later validate this from high-dimensional process data.

Q2: What are the key CQAs for a biodegradable scaffold made via thermal-induced phase separation (TIPS)? A: Primary CQAs include porosity (target: 85-95%), pore size distribution (e.g., 50-250 µm), compressive modulus (target: match native tissue), and degradation rate in vitro. These must be linked to CPPs like polymer concentration, quenching temperature, and solvent ratio.

Q3: My sensor data for CPPs is noisy. How does this affect ML for optimization? A: Noise can lead to overfitting and poor model performance on new data. Pre-process data with filtering (e.g., Savitzky-Golay) or wavelet denoising. Use feature engineering to create more robust inputs (e.g., moving averages, Fourier transforms) before training models like Random Forests or Neural Networks, which have varying noise tolerance.

Q4: What is a practical protocol for linking CPPs to CQAs in film blowing? A:

- Define CQAs: Film thickness uniformity, tear strength, oxygen transmission rate (OTR).

- Monitor CPPs: Melt temperature, blow-up ratio, frost line height, take-up speed.

- Experiment: Perform a Central Composite DoE varying CPPs.

- Characterize: Measure CQAs for each batch (see table below).

- Model: Use Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression or a Gaussian Process model to map CPPs to CQAs. This model becomes the target for subsequent ML-based real-time optimization.

Data Presentation: Representative Experimental Results

Table 1: Impact of Extrusion CPPs on Poly(Lactic Acid) (PLA) Filament CQAs

| Batch | Nozzle Temp. (°C) CPP | Screw Speed (RPM) CPP | Coolant Temp. (°C) CPP | Avg. Diameter (mm) CQA | Crystallinity (%) CQA | Tensile Strength (MPa) CQA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 190 | 40 | 25 | 1.75 ± 0.05 | 12.1 | 58.3 ± 2.1 |

| 2 | 210 | 40 | 25 | 1.72 ± 0.08 | 9.8 | 52.1 ± 3.0 |

| 3 | 190 | 60 | 25 | 1.69 ± 0.10 | 13.5 | 56.7 ± 2.8 |

| 4 | 190 | 40 | 10 | 1.77 ± 0.04 | 25.4 | 62.5 ± 1.9 |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item Name | Function / Relevance |

|---|---|

| Poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) | Model biodegradable polymer for drug delivery; degradation rate CPP-controlled via LA:GA ratio. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Conductive nanofiller; dispersion quality is a key CQA for composite properties. |

| DSC Calibration Standards | (Indium, Zinc) Essential for accurate measurement of thermal transitions (Tm, Tg) as CQAs. |

| GPC/SEC Standards | Narrow dispersity polystyrene for calibrating molecular weight (MW, PDI) analysis, a vital CQA. |

| In-line Rheometer Probe | Provides real-time viscosity data as a response variable for ML model training and control. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing the CPP-CQA Relationship via DoE Objective: Statistically link extrusion CPPs to filament CQAs for ML training data generation.

- Select CPPs: Choose 3-5 parameters (e.g., temperatures, screw speed, puller speed).

- Define Ranges: Set minimum and maximum bounds based on polymer stability.

- Design Experiment: Use a Response Surface Methodology (RSM) design like Box-Behnken.

- Execute Runs: Randomize run order to minimize confounding noise.

- Measure CQAs: For each batch, quantify diameter (micrometer), tensile strength (ASTM D638), crystallinity (DSC).

- Analyze: Fit a quadratic model. Significant terms (p<0.05) confirm CPP status.

Protocol 2: Real-Time Monitoring for Adaptive ML Control Objective: Capture high-frequency process data for digital twin or adaptive control.

- Instrument Process: Install calibrated sensors for temperature, pressure, and in-line rheology.

- Data Acquisition: Use a PLC or DAQ system to log data at ≥10 Hz.

- Synchronization: Timestamp all sensor data and off-line CQA measurements.

- Data Structuring: Create a time-synchronized database where each batch run is a separate file with columns for CPPs (sensor data) and final CQAs.

- Feature Extraction: Before ML, generate features (mean, std, FFT components) from time-series data for each batch.

Process Visualization

Diagram Title: ML-Driven CPP-CQA Linkage Workflow for Polymer Processing

Diagram Title: Troubleshooting Filament Diameter Variation

This technical support center is designed to assist researchers within the context of a thesis on Machine Learning for Polymer Process Optimization Research. The following guides address common issues in experimental data handling.

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

Q1: My supervised learning model for predicting polymer yield is overfitting. It performs excellently on training data but poorly on new batch data. What should I do? A: This is common with high-dimensional, collinear process data (e.g., multiple temperature/pressure sensors). Solutions include:

- Feature Selection: Use techniques like Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with cross-validation to identify the most critical process parameters.

- Regularization: Apply Lasso (L1) or Ridge (L2) regression to penalize model complexity.

- Data Augmentation: Use domain knowledge to create synthetic data points within known process windows (e.g., via SMOTE).

- Simplify the Model: Start with simpler models (e.g., Partial Least Squares regression) before using complex ensembles.

Q2: When applying unsupervised clustering (e.g., k-Means) to my batch process data, the clusters do not correspond to known quality grades. How can I improve this? A: This indicates your features may not capture the variance relevant to final product quality.

- Preprocess Data: Apply feature scaling (StandardScaler). Process data often has different units (temperature, pressure, viscosity) which skews distance-based algorithms.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or t-SNE to reduce noise and visualize if separability exists in lower dimensions.

- Incorporate Domain Labels Semi-Supervised: Try techniques like constrained clustering or use the known grades to guide feature engineering (e.g., create features like "time above melt temperature").

Q3: My process data is a time-series from extrusion. Should I treat it as tabular data or use a specialized approach? A: Standard ML treats data as i.i.d. (independent and identically distributed), which loses temporal context.

- Feature Engineering: Create time-window aggregates (mean, slope, variance) for key sensors as new tabular features for supervised learning.

- Specialized Models: For sequence prediction, use Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) or 1D Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) which can learn from raw time-series data.

- Data Formatting: Structure data into supervised learning format using a sliding window approach.

Table 1: Model Performance Comparison on Polymer Tensile Strength Prediction

| Model Type | Key Hyperparameters Tested | Avg. R² (Train) | Avg. R² (Test) | Primary Data Preprocessing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Regression (Ridge) | Alpha = [0.1, 1.0, 10.0] | 0.87 | 0.85 | Standard Scaling, PCA (n=8) |

| Random Forest | nestimators=100, maxdepth=5 | 0.92 | 0.88 | Raw Data, Feature Selection (top 10) |

| Support Vector Regressor | C=1.0, kernel='rbf' | 0.91 | 0.82 | Standard Scaling, Outlier Removal |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Building a Supervised Model for Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) Index Prediction

- Data Collection: Log all process parameters (zone temperatures, screw speed, pressure, feed rate) synchronized with final GPC measurements (Mn, Mw) for 50+ production batches.

- Feature Engineering: Calculate lagged features (e.g., temperature 5 minutes prior), moving averages, and rate-of-change for key sensors.

- Train/Test Split: Split data chronologically (80%/20%) to avoid temporal leakage.

- Model Training & Validation: Train a Random Forest regressor using 5-fold time-series cross-validation. Optimize hyperparameters (maxdepth, nestimators) to minimize test fold error.

- Deployment: Save the trained model pipeline (including scaler) to predict GPC index in real-time from live process data.

Protocol: Applying PCA & Clustering for Batch Process Anomaly Detection

- Data Alignment: Align data from multiple batches of varying duration using Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) or interpolation to a fixed time grid.

- Scale Data: Apply StandardScaler to each process variable across all batches.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Fit PCA on the scaled data. Retain enough components to explain >95% variance.

- Clustering: Apply k-Means clustering to the PCA-reduced scores. Use the Elbow Method on Within-Cluster-Sum-of-Squares to estimate optimal clusters.

- Analysis: Map clusters back to original batches and correlate with lab-measured defect types (e.g., discoloration, gel formation).

Visualizations

Title: Decision Workflow for Polymer Process Data ML Analysis

Title: PLS Regression for Process & Quality Data

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Solution Essentials

Table 2: Key Materials for ML-Driven Polymer Process Research

| Item | Function in ML Research Context |

|---|---|

| High-Frequency Data Logger | Captures real-time process variables (temp, pressure) at high resolution, creating the dense datasets needed for time-series ML models. |

| Lab-Scale Extruder/Reactor with Digital Controls | Provides a controlled environment to generate consistent, labeled batch data for supervised learning experiments. |

| Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) System | Generates the critical target labels (Molecular Weight Distribution, PDI) for supervised learning models predicting quality. |

| Rheometer | Provides labeled data on melt viscosity, a key quality metric and process parameter for model training. |

| Python/R with scikit-learn, TensorFlow/PyTorch | Core software ecosystems for implementing data preprocessing, ML algorithms, and neural network models. |

| Data Historian/Process Mgmt Software (e.g., OSIsoft PI) | Industrial systems for aggregating and storing large-scale historical process data used for model training. |

| Chemometrics Software (e.g., SIMCA) | Offers specialized implementations of PLS, PCA, and other models common in process analytics. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our polymer synthesis dataset has inconsistent property labels (e.g., "Tg" vs. "Glass Transition" vs. "glass-transition temperature"). How do we standardize this for ML feature engineering?

A: Implement a canonicalization pipeline. First, create a controlled vocabulary (CV) JSON file mapping all variants to a single term (e.g., "glass_transition_temperature_c"). Use a rule-based script (see protocol below) to normalize the dataset before feature extraction.

- Experimental Protocol 1.1: Text Normalization for Polymer Properties

- Input: Raw dataset column with property names.

- CV Load: Load the predefined JSON mapping dictionary.

- Fuzzy Matching: For each unique entry, apply a Levenshtein distance algorithm (

fuzzywuzzylibrary in Python) to find matches in the CV with >90% similarity for un-mapped terms. - Review & Update: Manually review fuzzy matches and update the CV.

- Transform: Apply the final CV to transform the entire dataset's column.

- Output: New column with canonicalized property names.

Q2: We are combining data from multiple labs, and the molecular weight distributions (MWD) are reported with different dispersity (Đ) formats (some as Mw/Mn, others as PDI). How should we structure this? A: Create a structured table with separate, clearly defined columns for each fundamental metric. Derived metrics should be calculated from primary data.

| Primary Data Column | Definition | Required Unit | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

mw_weight_avg_g_per_mol |

Weight-average molecular weight (Mw) | g/mol | 150,000 |

mw_number_avg_g_per_mol |

Number-average molecular weight (Mn) | g/mol | 100,000 |

dispersity_calculated |

Derived: Đ = Mw / Mn | Dimensionless | 1.50 |

Q3: When sourcing historical data, we encounter missing solvent entries for polymerization reactions. What is the best imputation strategy? A: Do not impute categorical data like specific solvent names. Instead, create a Boolean flag and an "Unknown" category.

| Original Data | Structured Column 1: solvent_name |

Structured Column 2: solvent_absent_flag |

|---|---|---|

| "Toluene" | "Toluene" | 0 |

| (Blank Cell) | "Unknown" | 1 |

| "DMF" | "N,N-Dimethylformamide" | 0 |

Q4: Our reaction yield data has outliers (>100%). How should we handle these before training a yield prediction model? A: Follow a two-step validation and capping protocol.

- Step 1 (Validation): Cross-reference the outlier entry with lab notebook notes or catalyst loading. Yields >100% often indicate incomplete purification or residual solvent mass.

- Step 2 (Capping): If no experimental error is found, apply a winsorizing technique. Cap yields at the 99th percentile of your dataset (e.g., if 99th %ile = 98%, set all values >98% to 98%).

Q5: How do we structure time-series data from in-situ FTIR monitoring for a machine learning-ready format? A: Use a tall (long) format for time-series data, linking each timepoint to the unique experiment ID. This is optimal for most ML frameworks.

experiment_id |

time_min |

wavenumber_cm_1 |

absorbance |

conversion_calculated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXP_001 | 0.0 | 1720 | 0.15 | 0.00 |

| EXP_001 | 0.5 | 1720 | 0.14 | 0.05 |

| EXP_001 | 1.0 | 1720 | 0.12 | 0.15 |

| EXP_002 | 0.0 | 1720 | 0.16 | 0.00 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Polymer/ML Research |

|---|---|

| RAFT Chain Transfer Agents (CTAs) | Provide controlled radical polymerization, enabling precise tuning of polymer molecular weight and architecture for structured dataset generation. |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆) | Essential for NMR spectroscopy to quantify monomer conversion, composition, and end-group fidelity, providing key numerical targets for ML models. |

| Internal Standards (e.g., mesitylene for GC) | Allow for accurate quantitative analysis of reaction components by chromatography, ensuring reliable label data for supervised learning. |

| Functional Initiators/Monomers | Introduce tags (e.g., halides, azides) for post-polymerization modification, creating diverse polymer libraries with trackable properties. |

| Silica Gel & Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Standards | For polymer purification and accurate molecular weight calibration, respectively, which are critical for generating high-fidelity ground-truth data. |

| In-situ ATR-FTIR Probes | Enable real-time kinetic data collection, generating rich, time-series datasets for ML-driven reaction monitoring and optimization. |

Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Title: Polymer Data Pipeline from Sourcing to ML Readiness

Title: ML-Driven Experimental Feedback Loop

Implementing ML Models: Predicting and Controlling Polymer Process Outcomes

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Why is my trained regression model (e.g., for predicting nanoparticle size) showing high error on new experimental batches? A: This is often due to dataset shift or inadequate feature engineering. Ensure your training data encompasses the full operational design space (ODS) of your polymer synthesis process (e.g., solvent ratio, stirring speed, polymer molecular weight ranges). Standardize all input features (mean=0, variance=1). For polymer-based nanoparticles, include derived features like the logP of solvents or the polymer:solvent viscosity ratio, which critically impact size. Retrain the model with data augmented by techniques like SMOTE if certain process conditions are underrepresented.

Q2: How can I improve model predictions for drug release kinetics, which often show a biphasic profile?

A: A single linear model may be insufficient. Implement a multi-output regression model (e.g., Random Forest or Gaussian Process Regression) that predicts key release parameters simultaneously, such as the burst release percentage (α) and the sustained release rate constant (β). Alternatively, use a hybrid approach: train one model for the initial burst phase (0-24h) and another for the sustained phase (24h+), using initial conditions from the first phase as inputs to the second.

Q3: My PLSR model for drug loading efficiency is overfitting despite using cross-validation. What should I check? A: First, verify the variable importance in projection (VIP) scores. Remove features with VIP < 0.8. Second, ensure the number of latent variables (LVs) is optimized via a separate validation set, not just k-fold CV on the training set. Third, pre-process spectroscopic or chromatographic data correctly: use Savitzky-Golay smoothing and standard normal variate (SNV) scaling before input to PLSR. Overfitting often arises from uncorrected baseline shifts in raw data.

Q4: What are common pitfalls when using regression to optimize the emulsion-solvent evaporation process for particle size control? A: Key pitfalls include:

- Ignoring non-linear interactions: The effect of surfactant concentration on size is often logarithmic, not linear. Use models like Support Vector Regression (SVR) with a non-linear kernel (RBF) or include interaction terms (e.g.,

Polymer Conc. * Stirring Rate). - Poorly controlled categorical variables: The "type of surfactant" (e.g., PVA, Poloxamer) must be one-hot encoded. Its interaction with solvent type (e.g., DCM, ethyl acetate) is critical.

- Inadequate response measurement: Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) provides a polydispersity index (PDI). Use PDI as a second response variable in a multi-target model, as a single size prediction is misleading if PDI is high.

Q5: How do I validate a machine learning regression model for a regulatory submission in drug development? A: Follow the ASTM E3096-19 standard. Beyond standard train/test splits, implement:

- Temporal Validation: Train on older batches, test on newest.

- Process-Scale Validation: Train on lab-scale (e.g., 100mL) data, test on pilot-scale (e.g., 10L) data, explicitly including scale as a feature.

- External Validation: Use data generated by a different operator or equipment lot. Report Q² (prediction coefficient) for external sets. Document all data pre-processing steps as part of the model's "recipe."

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Generating Data for Drug Loading & Release Kinetics Modeling

Objective: To produce a consistent dataset for training regression models predicting loading efficiency (LE%) and release rate constant (k).

- Nanoparticle Synthesis (Double Emulsion): For each run, vary: Polymer (PLGA) concentration (10-50 mg/mL), Aqueous phase volume (5-20% v/v), Homogenization speed (10,000-20,000 rpm, 2 min). Fix drug (e.g., Doxorubicin) at 2 mg.

- Drug Loading Quantification: Lyophilize particles from 3 replicate batches. Dissolve 5 mg of particles in 1 mL DMSO. Measure drug absorbance via HPLC (UV-Vis at 480 nm for Doxo). Calculate

LE% = (Mass of drug in particles / Total mass of particles) * 100. - In Vitro Release Study: Place 10 mg of particles in 10 mL PBS (pH 7.4, 37°C) under gentle agitation (100 rpm). Sample (1 mL) and replace with fresh PBS at time points: 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24, 48, 96, 168h. Analyze drug content via HPLC. Fit cumulative release data to the Korsmeyer-Peppas model (

M_t/M∞ = k*t^n) to extractkandn. - Feature Recording: Record all process parameters, ambient conditions (temperature, humidity), and material attributes (polymer lot, solvent purity).

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Particle Size Analysis for Model Training

Objective: To generate precise size (Z-Avg) and PDI data as response variables.

- Sample Preparation: Dilute nanoparticle suspension 1:20 in filtered (0.2 µm) deionized water. Perform dilution in triplicate.

- DLS Measurement: Use a Zetasizer Nano ZS. Equilibrate samples at 25°C for 2 min. Perform 3 measurements per replicate, each consisting of 13-15 sub-runs.

- Data Curation: Record Z-Average (nm) and PDI. Apply an outlier filter: discard any run where the difference between mean and median size is >10%. Use the mean of the remaining runs as the final data point.

- Feature Association: Immediately link each size measurement to the exact process parameter set from Protocol 1 in a structured database (e.g., .csv file).

Table 1: Representative Dataset for Regression Modeling (Polymer: PLGA 50:50, Drug: Model Hydrophobic Compound)

| Batch ID | PLGA Conc. (mg/mL) | Homogenization Speed (rpm) | Surfactant (%w/v) | Z-Avg (nm) | PDI | Drug Loading (%) | Release k (h⁻ⁿ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B001 | 20 | 12,500 | 1.0 (PVA) | 215 | 0.12 | 4.3 | 0.15 |

| B002 | 40 | 12,500 | 1.0 (PVA) | 168 | 0.09 | 8.1 | 0.09 |

| B003 | 20 | 17,500 | 1.0 (PVA) | 142 | 0.15 | 4.0 | 0.21 |

| B004 | 40 | 17,500 | 2.0 (PVA) | 121 | 0.08 | 7.8 | 0.11 |

| B005 | 30 | 15,000 | 1.5 (Poloxamer188) | 185 | 0.10 | 6.2 | 0.18 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Regression Models for Predicting Particle Size

| Model Type | Key Features Used | R² (Test Set) | RMSE (nm) | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) | Polymer Conc., Speed, Surfactant Conc. | 0.72 | 28.4 | Initial screening, linear parameter spaces. |

| Support Vector Regression (RBF) | MLR features + (Polymer Conc. * Speed) interaction | 0.91 | 12.7 | Capturing complex, non-linear interactions. |

| Random Forest (RF) | MLR features + solvent logP, temperature | 0.94 | 10.1 | High-dimensional data, automatic feature importance ranking. |

| Partial Least Squares (PLS) | Spectral data (FTIR) of pre-emulsion + process vars | 0.88 | 16.3 | When inputs are highly collinear (e.g., spectroscopic). |

Diagrams

Title: ML Workflow for Polymer Nanoparticle Process Optimization

Title: Multi-Target Regression Modeling Drug Release Kinetics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Reagent | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| PLGA (50:50, acid-terminated) | The biodegradable polymer matrix. Lactide:glycolide ratio & Mw are critical features for release regression. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA, 87-89% hydrolyzed) | Common surfactant/stabilizer in emulsion processes. Concentration is a key model input for size prediction. |

| Dichloromethane (DCM, HPLC grade) | Organic solvent for polymer dissolution. Volatility influences particle formation kinetics. |

| Poloxamer 188 | Non-ionic surfactant alternative to PVA. Used as a categorical variable in models to compare stabilizers. |

| PBS (pH 7.4), 0.01M | Standard release medium. Ionic strength and pH must be controlled as constants in release studies. |

| Dialysis Membranes (MWCO 12-14 kDa) | For purification of nanoparticles. Consistent MWCO ensures reproducible impurity removal across batches. |

| Zetasizer Nano ZS | DLS instrument for measuring particle size (Z-Avg) and PDI—the primary response variables for size models. |

| HPLC System with UV-Vis Detector | Quantifies drug loading and release kinetics. Precision directly affects regression model target accuracy. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: During feature engineering for polymer batch spectral data, I encounter severe overfitting when using a Random Forest classifier. The cross-validation accuracy is high, but the model fails on new production batches. What is the likely cause and solution?

A: The most common cause is data leakage or non-representative features. In polymer spectroscopy (e.g., NIR, Raman), environmental factors (humidity, temperature) can create batch-to-batch spectral shifts that are not chemically relevant.

- Solution Protocol:

- Apply Standard Normal Variate (SNV) or Detrending: Preprocess all spectral data to remove scatter effects.

- Method: For each spectrum, subtract its mean and divide by its standard deviation.

- Use Domain-Invariant Features: Instead of raw absorbance at all wavelengths, extract features using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the preprocessed training set. Retain only the first n components that explain >95% variance. Apply the same PCA transformation to new data.

- Re-train: Train the Random Forest on the PCA-reduced features. Perform nested cross-validation to tune hyperparameters (maxdepth, minsamples_leaf) on the inner loop.

- Apply Standard Normal Variate (SNV) or Detrending: Preprocess all spectral data to remove scatter effects.

Q2: My SVM model for classifying defective injection-molded polymer parts performs poorly on imbalanced data (only 5% defective). How can I improve recall for the defective class without compromising overall integrity?

A: Class imbalance causes the SVM to favor the majority class. You need to adjust class weights and potentially use anomaly detection techniques.

- Solution Protocol:

- Apply Class Weights: Set

class_weight='balanced'in your SVM implementation (e.g., sklearn's SVC). This penalizes mistakes on the minority class proportionally more. - Synthetic Data Generation: Use SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) only on the training set to generate synthetic defective samples.

- Threshold Moving: After training, adjust the decision threshold by analyzing the Precision-Recall curve on the validation set. Choose a threshold that meets your target recall (e.g., 90%).

- Validate: Use metrics like F2-score (emphasizes recall) or Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) instead of accuracy for final evaluation.

- Apply Class Weights: Set

Q3: When implementing a real-time CNN for visual inspection of polymer film defects, the model's inference time is too slow for the production line speed. How can I optimize it?

A: This is a model compression and hardware optimization problem.

- Solution Protocol:

- Model Pruning: Use a library like TensorFlow Model Optimization Toolkit to prune your trained CNN (remove low-weight neurons). Fine-tune the pruned model.

- Quantization: Convert the model's weights from 32-bit floating-point to 16-bit float or 8-bit integers. This drastically reduces size and latency with minimal accuracy loss.

- Architecture Switch: Consider replacing your CNN backbone with a more efficient architecture like MobileNetV3 or EfficientNet-Lite specifically designed for edge deployment.

- Hardware Acceleration: Deploy the quantized model on hardware with dedicated AI accelerators (e.g., Google Coral TPU, NVIDIA Jetson).

Research Reagent & Solutions Toolkit

| Item | Function in Polymer QC ML Research |

|---|---|

| NIR Spectrometer | Captures near-infrared spectra of polymer batches; raw data source for chemical fingerprinting. |

| Rheometer | Measures melt flow index (MFI) and viscoelastic properties; provides critical target variables for regression-based quality prediction. |

| Pyrometer (Infrared Thermometer) | Non-contact temperature measurement crucial for ensuring consistent thermal history across training data batches. |

| Digital Image Microscopy System | Captures high-resolution images of film surfaces or part fractures for defect detection via computer vision models. |

| Lab-Scale Twin-Screw Extruder | Allows for controlled, small-batch polymer processing with variable parameters (screw speed, temperature zones) to generate structured experimental data. |

| MATLAB/Python with Scikit-learn, TensorFlow/PyTorch | Core software for developing, training, and validating classification algorithms. |

| Minitab or JMP Statistical Software | Used for Design of Experiments (DoE) to plan data acquisition runs and for preliminary statistical process control (SPC) analysis. |

| Reference Polymer Resins (Certified) | Provide consistent baseline material to calibrate sensors and validate that observed variations are process-related, not material-related. |

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking Classifiers for Batch QC

Objective: Compare the performance of Logistic Regression, Random Forest, and XGBoost in classifying polymer batches as Acceptable or Defective based on process parameter data.

Methodology:

- Data Generation: Use a lab-scale extruder to produce 300 batches of polypropylene. Systematically vary four key parameters: Barrel Temperature (°C), Screw Speed (RPM), Cooling Rate (°C/min), and Feed Rate (kg/h). Each batch is labeled by a human expert based on final product testing (tensile strength, discoloration).

- Feature-Label Pairing: Each batch is a data point with four process parameters as features and a binary label (0=Acceptable, 1=Defective).

- Model Training: Split data 70/30 (train/test). Train three models using 5-fold cross-validation on the training set.

- Logistic Regression: Use L2 regularization. Standardize all features.

- Random Forest: Tune

n_estimators=200,max_depth=10,min_samples_leaf=4. - XGBoost: Tune

n_estimators=150,max_depth=6,learning_rate=0.1.

- Evaluation: Apply trained models to the held-out test set. Record performance metrics.

Results Summary:

| Algorithm | Accuracy | Precision (Defective) | Recall (Defective) | F1-Score (Defective) | Inference Time per Batch (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression | 88.9% | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.5 |

| Random Forest | 93.3% | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 4.2 |

| XGBoost | 94.4% | 0.93 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 1.8 |

Visualizations

ML Workflow for Polymer Batch QC

Ensemble Decision Logic for Batch Classification

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

This technical support center is designed for researchers employing deep learning (DL) for pattern recognition in spectroscopy (e.g., Raman, FTIR, NIR) and imaging (e.g., SEM, microscopy) data within the context of machine learning for polymer process optimization and drug development research. It addresses common pitfalls encountered during experimental workflows.

FAQ 1: My convolutional neural network (CNN) for spectral classification achieves >99% accuracy on training data but performs poorly (<60%) on validation data. What is happening and how can I fix it?

- Answer: This indicates severe overfitting. Your model has memorized the training data, including noise, instead of learning generalizable features.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Data Augmentation: Artificially increase your dataset size. For spectral data, apply controlled perturbations (e.g., adding Gaussian noise, scaling, random offset, or simulating baseline drift). For imaging data, use rotations, flips, and crops.

- Regularization: Implement L1/L2 regularization in your dense layers and use Dropout layers. A typical starting point is a dropout rate of 0.3-0.5.

- Simplify Architecture: Reduce the number of trainable parameters (fewer filters or dense units). A complex model is more prone to overfitting on small datasets.

- Early Stopping: Monitor validation loss and halt training when it stops improving for a set number of epochs (patience).

- Check Data Splitting: Ensure your training and validation sets are statistically similar and representative of the same process conditions. Random shuffling before splitting is critical.

FAQ 2: When using an autoencoder for denoising Raman spectra, the output is overly smooth and loses critical subtle peaks. How do I preserve these features?

- Answer: This is often due to an imbalance in the loss function, favoring overall reconstruction error over fine-detail preservation.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Loss Function Modification: Use a combination of Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Spectral Angle Mapper (SAM) or Cosine Similarity loss. SAM is less sensitive to intensity and more focused on spectral shape.

- Example Code Snippet (Conceptual):

total_loss = alpha * mse_loss(reconstructed, target) + beta * cosine_loss(reconstructed, target)

- Example Code Snippet (Conceptual):

- Architecture Adjustment: Implement a skip-connection (U-Net style) architecture. This allows the decoder to access high-resolution features from the encoder, helping to reconstruct fine details.

- Training Data: Ensure your training pairs of "noisy" and "clean" spectra are perfectly aligned. Misalignment will force the network to learn an averaging function.

- Loss Function Modification: Use a combination of Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Spectral Angle Mapper (SAM) or Cosine Similarity loss. SAM is less sensitive to intensity and more focused on spectral shape.

FAQ 3: My model's predictions for polymer crystallinity from imaging data show high variance between different batches processed under nominally identical conditions. Is this a model or data issue?

- Answer: This is likely a data domain shift issue, where the training data does not encompass the full natural variability of the process (e.g., slight changes in lighting, staining, or sample preparation between batches).

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Domain Adaptation: Incorporate techniques like Domain Adversarial Neural Networks (DANN) to learn features invariant to batch-specific variations.

- Input Normalization: Apply robust, per-image normalization (e.g., scaling to [0,1] based on image percentiles) instead of global dataset normalization.

- Data Collection: Systematically include data from all known process variations in your training set. The model can only recognize patterns it has seen.

FAQ 4: How much data do I realistically need to train a robust model for a classification task in this domain?

- Answer: There is no universal number, but the following table provides benchmarks based on published studies and best practices. Complexity refers to the number of distinct, non-overlapping classes or the granularity of the regression target.

| Task Complexity | Minimum Recommended Samples per Class | Recommended Model Starting Point | Typical Reported Accuracy Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binary Classification (e.g., Contaminant Present/Absent) | 500 - 1,000 | Simple CNN (3-4 conv layers) or 1D-CNN for spectra | 92% - 98% |

| Multi-class (5-10 classes, e.g., Polymer Types) | 1,000 - 2,500 | Moderate CNN / ResNet-18 | 85% - 95% |

| High-fidelity Regression (e.g., Predicting Molecular Weight) | 5,000+ total samples | Deep CNN with attention mechanisms or ensemble | R²: 0.88 - 0.97 |

Note: These figures assume high-quality, well-annotated data. Data augmentation can effectively multiply these numbers.

Experimental Protocol: Deep Learning Workflow for Polymer Phase Identification from Spectral Imaging Data

Objective: To train a CNN that automatically identifies amorphous and crystalline phases from Raman spectral image hypercubes of a polymer film.

Protocol:

Data Acquisition:

- Acquire Raman hypercubes using a confocal Raman microscope. Each pixel contains a full spectrum (e.g., 500-3200 cm⁻¹).

- Process Conditions: Acquire data from films processed at different cooling rates (e.g., quenched, slow-cooled) to induce varying crystallinity.

Ground Truth Labeling:

- Manually label regions in a subset of hypercubes as "Amorphous," "Crystalline," or "Interface" using known spectral signatures (e.g., peak sharpness at 1416 cm⁻¹).

- Split data into Training (70%), Validation (15%), and Test (15%) sets, ensuring pixels from the same physical region do not leak across sets.

Data Preprocessing (Per Spectrum):

- Subtract rolling-ball baseline.

- Normalize using Standard Normal Variate (SNV) or Min-Max scaling.

- Augment training data by adding random Gaussian noise (SNR ~30) and random baseline tilt.

Model Training:

- Architecture: Use a 1D-CNN accepting a single spectrum as input.

- Layers: Input -> Conv1D(64, kernel=5) -> ReLU -> Dropout(0.3) -> Conv1D(128, kernel=3) -> ReLU -> GlobalAveragePooling1D() -> Dense(64, activation='relu') -> Dense(3, activation='softmax').

- Training: Use Adam optimizer (lr=0.001), categorical crossentropy loss. Employ Early Stopping (patience=10) monitoring validation loss.

Validation & Application:

- Evaluate on the held-out test set using confusion matrix and F1-score.

- Apply the trained model to all pixels in a new hypercube to generate a predicted phase map.

Workflow Diagram: DL for Polymer Spectral Analysis

Diagram Title: Workflow for DL Analysis of Polymer Spectroscopy & Imaging Data

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Solution | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| PyTorch / TensorFlow | Core open-source libraries for building and training deep neural networks with GPU acceleration. |

| SciKit-Learn | Used for initial data exploration, traditional ML baselines (PCA, SVM), and model evaluation metrics. |

| Hyperopt or Optuna | Frameworks for automated hyperparameter optimization (e.g., learning rate, layers, dropout) to maximize model performance. |

| Domino or Weights & Biases (W&B) | MLOps platforms to track experiments, log hyperparameters, metrics, and model versions for reproducibility. |

| Standard Reference Materials (SRM) | Certified polymer samples with known crystallinity or composition for model validation and instrument calibration. |

| Spectral Databases (e.g., IRUG, PubChem) | Curated libraries of reference spectra for feature identification and aiding ground truth labeling. |

| MATLAB Image Processing Toolbox | Alternative/companion tool for advanced pre-processing of imaging data (segmentation, filtering) before DL. |

| Jupyter Notebook / Google Colab | Interactive development environment for prototyping code, visualizing results, and sharing analyses. |

Overcoming Challenges: Troubleshooting Data and Process Issues with AI

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My polymer tensile strength prediction model is severely overfitting on a dataset of only 50 samples. What are my primary mitigation strategies? A: For polymer datasets under 100 samples, employ a combined strategy:

- Algorithm Choice: Use simple, interpretable models like Ridge Regression or Gaussian Process Regression as a baseline before complex neural networks.

- Aggressive Regularization: Apply L2 regularization and consider dropout rates >50% if using a neural network.

- Data-Centric Augmentation: Use domain-informed techniques. For polymer stress-strain curves, apply safe, physics-guided transformations like additive Gaussian noise (σ = 0.5-1% of signal mean) or linear elastic region scaling (±5%). Avoid unrealistic deformations that violate polymer physics.

- Leverage Pre-trained Models: Utilize Transfer Learning. Fine-tune a model pre-trained on large, public material science datasets (e.g., MatBench, PolymerNet) on your small proprietary dataset. Freeze initial feature extraction layers.

Q2: How can I validate my model reliably when I cannot afford to hold out a large test set? A: Standard train/test splits are unreliable. Implement rigorous resampling:

- Nested Cross-Validation (CV): Use an outer loop (e.g., 5-fold) for performance estimation and an inner loop (e.g., 4-fold) for hyperparameter tuning. This prevents data leakage and optimistic bias.

- Leave-One-Out (LOO) or Leave-P-Out CV: Ideal for very small sets (n<30). Provides nearly unbiased estimates but is computationally expensive and high variance.

- Bootstrapping: Randomly sample your dataset with replacement to create many training sets, evaluate on the unsampled points. Good for confidence intervals.

Q3: I have spectroscopic data for 20 novel copolymer formulations. Are there techniques to generate plausible synthetic data? A: Yes, with caution. For small, high-dimensional data like spectra:

- Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE): Creates synthetic samples by interpolating between nearest neighbors in feature space. Preferable to simple duplication.

- Generative Models: Use Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) to learn a latent distribution of your spectra and sample from it. This requires careful validation that generated spectra maintain physically plausible peak shapes and relationships.

- Leverage Public Data: Train a VAE on a large public spectral library (e.g., NIST), then fine-tune the decoder on your small dataset to generate spectra consistent with your chemical domain.

Q4: What is Bayesian Optimization, and why is it recommended for small-data R&D experiments? A: Bayesian Optimization (BO) is a sample-efficient sequential design strategy for optimizing black-box functions (like polymer formulation for maximum yield). It builds a probabilistic surrogate model (often a Gaussian Process) of the objective and uses an acquisition function to decide the next most informative experiment. It is ideal for small datasets because it explicitly models uncertainty, reducing the number of costly physical experiments needed to find an optimum.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Small-Data Validation Techniques for Polymer Datasets (n=30-100)

| Technique | Best For | Computational Cost | Variance of Estimate | Key Consideration in Polymer Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hold-Out (80/20) | Initial prototyping | Low | Very High | Risky; test set may not be representative of complex formulation space. |

| k-Fold CV (k=5) | Most general use cases | Medium | Medium | Ensure folds are stratified by key properties (e.g., monomer class). |

| Leave-One-Out CV | Extremely small sets (n<30) | High | High | Can be useful for final evaluation of a fixed model. |

| Nested CV | Hyperparameter tuning & unbiased evaluation | Very High | Low | Gold standard for publishing results from small-scale studies. |

| Bootstrapping | Estimating confidence intervals | Medium | Medium | Useful for quantifying uncertainty in predicted polymer properties. |

Table 2: Data Augmentation Techniques for Common Polymer Data Types

| Data Type | Technique | Example Parameters | Physicality Constraint |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stress-Strain Curve | Elastic Noise Addition | Add N(0, 0.5 MPa) to stress values | Do not alter the linear elastic region's positive slope. |

| FTIR Spectrum | Warping & Scaling | Random stretch/shrink by ±2% on wavenumber axis | Maintain peak absorbance ratios characteristic of functional groups. |

| DSC Thermogram | Baseline Shift | Add linear baseline with random slope ≤ 0.01 mW/°C | Do not shift the glass transition (Tg) or melting (Tm) peak temperatures. |

| Formulation Table | Mixup (Linear Interpolation) | λ=0.1-0.3 for two formulations | Check for chemical incompatibility or unrealistic ratios (e.g., >100% wt.). |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Nested Cross-Validation for a Polymer Property Predictor

- Define Outer Loop: Split your dataset of

Nsamples intok_outer(e.g., 5) folds. Maintain class/distribution stratification. - Iterate Outer Loop: For each of the

k_outeriterations: a. Hold out one fold as the test set. b. The remainingk_outer - 1folds form the development set. - Define Inner Loop: Split the development set into

k_inner(e.g., 4) folds. - Hyperparameter Tuning: For each candidate hyperparameter set:

a. Train on

k_inner - 1folds, validate on the held-out inner fold. Repeat for allk_innerfolds. b. Compute the average validation score across all inner folds. - Select Best Model: Choose the hyperparameter set with the best average inner-loop validation score.

- Final Training & Evaluation: Train a new model with the best hyperparameters on the entire development set. Evaluate it on the held-out outer test fold. Record this score.

- Repeat & Aggregate: Repeat steps 2-6 for all

k_outerfolds. The final model performance is the average of allk_outertest scores. The model presented in the paper is the one trained on the full dataset using the optimal hyperparameters found.

Protocol 2: Bayesian Optimization for Reaction Condition Optimization

- Define the Objective Function: This is your experimental outcome (e.g., polymer molecular weight, yield). It takes parameters like temperature, catalyst concentration, and time as input.

- Define Parameter Space: Set min/max bounds for each parameter (e.g., Temp: [60, 120]°C).

- Initial Design: Perform a small space-filling design (e.g., Latin Hypercube Sampling) of 5-10 initial experiments. Measure the objective.

- Build/Update Surrogate Model: Fit a Gaussian Process (GP) model to all data collected so far. The GP provides a prediction and uncertainty estimate for any point in the parameter space.

- Maximize Acquisition Function: Calculate an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) across the space. Select the parameter set where this function is maximized. This point balances exploration (high uncertainty) and exploitation (high predicted value).

- Run Experiment & Iterate: Conduct the proposed experiment, measure the outcome, and add the new (parameters, outcome) pair to your dataset. Repeat from step 4 until a performance target or experiment budget is reached.

Mandatory Visualization

Small-Data Research Workflow for Polymers

Nested Cross-Validation for Small Datasets

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Small-Data Polymer R&D

| Tool / Solution | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| scikit-learn | Primary Python library for traditional ML, CV, and simple preprocessing. | Implementing Ridge Regression, SVM, and k-fold CV for property prediction. |

| GPyTorch / scikit-optimize | Libraries for building Gaussian Process models and Bayesian Optimization. | Creating a surrogate model to optimize catalyst concentration for yield. |

| SMOTE (imbalanced-learn) | Algorithm for generating synthetic samples for minority classes/formulations. | Balancing a dataset where high-impact strength formulations are rare. |

| MatMiner & matminer | Toolkits for accessing and featurizing materials data from public sources. | Generating features from polymer chemical formulas for transfer learning. |

| TensorFlow / PyTorch | Deep learning frameworks for building custom neural networks and VAEs. | Constructing a VAE to generate synthetic FTIR spectra for data augmentation. |

| Matplotlib / Seaborn | Visualization libraries for creating clear, publication-quality plots. | Plotting Bayesian Optimization convergence or CV results. |

| Chemoinformatics Library (RDKit) | Computational chemistry toolkit for molecule manipulation and descriptor calculation. | Converting SMILES strings of monomers/molecules into numerical features. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: During feature creation for a twin-screw extrusion process, my domain-knowledge features (like Specific Mechanical Energy) are highly correlated, causing multicollinearity in my ML model. How do I handle this? A1: This is a common issue. You have several options:

- Feature Selection: Use regularization techniques (Lasso Regression) which can force coefficients of less important correlated features to zero.

- Feature Aggregation: Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to transform correlated features into a smaller set of uncorrelated principal components that capture most of the variance.

- Domain-Based Combination: Create a single, physically meaningful composite feature. For example, instead of using barrel temperature and screw speed separately, use a derived "thermal history" index validated by prior research.

Q2: My dataset from a series of injection molding trials is imbalanced—very few rows represent the optimal "sweet spot" for mechanical properties. How can I engineer or select features to improve model performance on this critical class? A2: Imbalanced data requires careful strategy:

- Synthetic Data Generation: Use techniques like SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) to create synthetic samples of the optimal class in feature space. However, ensure the synthetic data points are physically plausible in your process parameter ranges.

- Algorithmic Approach: Use tree-based models (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost) that can handle imbalance better. Adjust the

class_weightorscale_pos_weightparameters to penalize misclassification of the minority optimal class more heavily. - Performance Metrics: Do not rely on accuracy. Use Precision, Recall (Sensitivity), F1-Score, and AUC-ROC for the optimal class to guide feature selection.

Q3: When using automated feature selection methods (like Recursive Feature Elimination - RFE), the selected parameters sometimes lack physical interpretability for our polymer scientists. How can we bridge this gap? A3: Maintain a hybrid, iterative approach:

- Two-Stage Selection: First, use RFE or feature importance ranking to shortlist 15-20 features. Then, have a domain expert review this list to veto or justify features based on polymer chemistry/processing principles.

- Constraint-Based Engineering: Build a "plausibility check" into your pipeline. Any selected feature must be explainable within the context of known structure-property-process relationships. If not, investigate the feature's interaction effects.

- Visual Validation: Use SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) plots to explain model predictions. This highlights how each selected feature influences the output, aligning ML findings with domain knowledge.

Q4: For my film casting optimization, I have high-frequency sensor data (melt pressure, temperature). What are effective methods to transform this time-series data into static features for my ML model? A4: You must extract summary statistics that capture process stability:

- Statistical Features: Mean, variance, skewness, kurtosis of the signal over a stable window.

- Stability Features: Slope of a linear trend, range (max-min), or standard deviation.

- Domain-Specific Features: Number of pressure spikes exceeding a threshold, frequency of dominant oscillation via FFT.

- Structured Aggregation: Calculate these features for distinct phases of the process (e.g., startup, stable operation, shutdown) separately.

Table 1: Common Feature Engineering Techniques for Polymer Processing Data

| Feature Type | Example for Extrusion | Example for Injection Molding | Purpose in ML Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Parameter | Barrel Zone T3 (°C) | Packing Pressure (MPa) | Direct process input. |

| Derived / Composite | Specific Mech. Energy = Motor Torque * Screw Speed / Mass Flow Rate | Cooling Rate = (Melt Temp - Mold Temp) / Cooling Time | Captures synergistic physical effects. |

| Interaction Term | Screw Speed * Viscosity Index | Injection Speed * Melt Flow Index | Models non-linear parameter interactions. |

| Statistical Aggregation | Std. Dev. of Melt Pressure (last 5min) | Rate of Pressure Drop during Packing | Captures process stability and dynamics. |

| Polynomial Term | (Mold Temp)^2 | (Clamp Force)^2 | Captures non-linear, single-parameter effects. |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Feature Selection Methods on a Polymer Grade Classification Task

| Selection Method | Num. Features Selected | Model Accuracy | Model Interpretability | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variance Threshold | 28 | 0.82 | Low | Very Low |

| Correlation Filtering | 19 | 0.85 | Medium | Low |

| L1 Regularization (Lasso) | 12 | 0.88 | High | Medium |

| Tree-Based Importance | 15 | 0.90 | High | Medium |

| Recursive Feature Elim. (RFE) | 10 | 0.91 | Medium | High |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Method for Generating and Validating Composite Features (e.g., Specific Mechanical Energy - SME)

- Data Collection: Conduct designed experiments (e.g., DoE) on a twin-screw extruder, recording motor torque (N-m), screw speed (RPM), and mass flow rate (kg/hr) at steady state.

- Calculation: Compute SME (kWh/kg) for each run using the formula:

SME = (Motor Torque * 2π * Screw Speed) / (60 * 1000 * Mass Flow Rate). - Physical Validation: Correlate the calculated SME with an independent measure of melt temperature rise (ΔT) or polymer degradation (via GPC) to confirm its physical relevance.

- ML Integration: Use the validated SME feature alongside raw parameters in your regression model for predicting properties like tensile strength.

Protocol 2: Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) Cross-Validation Workflow

- Preprocessing: Standardize all features (mean=0, std=1). Split data into training (70%) and hold-out test (30%) sets.

- Base Model: Choose an estimator (e.g., Support Vector Regressor).

- RFE Loop: Initialize RFE to select the top

kfeatures. Use 5-fold cross-validation on the training set to score different values ofk. - Selection: Identify the

kthat yields the highest mean CV score. RFE refits the model using only thosekfeatures on the full training set. - Final Evaluation: Test the final model with the selected

kfeatures on the untouched hold-out test set.

Process Optimization Workflow Diagram

Feature Selection for Process Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Solution Guide

| Item | Function in ML for Polymer Process Optimization |

|---|---|

| Design of Experiments (DoE) Software | Plans efficient experimental runs to maximize information gain (features) while minimizing costly trials. |

| Process Historian / SCADA Data | Primary source for time-series raw parameters (temperatures, pressures, speeds) used for feature creation. |

| Material Characterization Data | Provides target variables (e.g., Mw, tensile strength) and material-based features (e.g., MFR, viscosity). |

| Python/R with ML Libraries | Environment for coding feature engineering (Pandas, NumPy) and selection (scikit-learn, XGBoost). |

| SHAP or LIME Libraries | Tools for post-model interpretability, explaining how selected features influence predictions. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Resources for computationally intensive feature selection methods (e.g., RFE with large datasets). |

Handling Noisy and Imbalanced Data from Pilot-Scale and Manufacturing Runs

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our process sensor data from the reactor is extremely noisy, causing poor model performance. What are the first steps to mitigate this? A1: Begin with a systematic signal processing and feature engineering pipeline. First, apply a rolling median filter (window size = 5-7 samples) to remove spike noise without lag. Then, use Savitzky-Golay smoothing (2nd order polynomial, window 11) to preserve key trends. For critical process parameters (e.g., temperature, pressure), calculate rolling statistical features (mean, standard deviation, min, max over a 60-second window) to use as model inputs instead of raw values. Always validate smoothing by comparing the processed signal to known process upsets in a separate validation batch.

Q2: Our dataset has 95% "In-Spec" batches and only 5% "Fault" batches. How can we train a reliable classifier?

A2: Imbalanced batch classification requires strategic resampling and algorithm choice. Do not use random oversampling of the minority class. Instead, use the SMOTEENN hybrid technique: Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) generates synthetic fault examples, followed by Edited Nearest Neighbors (ENN) to clean overlapping data. Use algorithms robust to imbalance, such as Random Forest with class weighting (set class_weight='balanced') or XGBoost with the scale_pos_weight parameter set to (number of majority samples / number of minority samples). Always evaluate performance using metrics like Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) or the F1-score for the fault class, not overall accuracy.

Q3: How do we validate a model when we have only a handful of faulty manufacturing runs? A3: Employ rigorous, iterative validation protocols. Use Leave-One-Group-Out (LOGO) cross-validation, where each "group" is a single fault batch and all its associated data. This ensures the model is tested on a completely unseen fault type. Supplement this with bootstrapping (1000+ iterations) on the available fault data to estimate confidence intervals for your performance metrics. This combines limited real fault data with simulated scenarios.

Q4: Pilot-scale data distributions differ significantly from manufacturing-scale data. How can we adapt our models? A4: Implement Domain Adaptation techniques. Use Scaler Autotuning: Fit your scaling transform (e.g., StandardScaler) on pilot data, but then calculate and apply a linear correction factor for the manufacturing data mean and variance for each key feature. A more advanced method is Correlation Alignment (CORAL), which minimizes domain shift by aligning the second-order statistics of the source (pilot) and target (manufacturing) features without requiring target labels.

Q5: What is a robust experimental protocol for testing data preprocessing strategies? A5: Follow this controlled protocol:

- Data Segmentation: Split data by batch ID. Never split data randomly across batches.

- Baseline Establishment: Train a simple model (e.g., logistic regression) on raw features. Record MCC/F1-score.

- Preprocessing Module Test: Test each preprocessing step (smoothing, feature engineering, resampling) in isolation using the same LOGO CV split.

- Combination & Tuning: Combine the best-performing modules into a pipeline. Perform hyperparameter tuning within each LOGO fold to prevent data leakage.

- Final Evaluation: Report performance on a completely held-out temporal set (the most recent batches).

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Imbalance Handling Techniques

| Technique | Algorithm | MCC | Fault Class F1-Score | In-Spec Class Recall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class Weighting | Random Forest | 0.72 | 0.71 | 0.98 |

| SMOTE | XGBoost | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.96 |

| SMOTEENN | XGBoost | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.97 |

| Under-Sampling | Random Forest | 0.61 | 0.65 | 0.89 |

Table 2: Impact of Signal Processing on Feature Stability

| Processing Method | Feature Noise (Std Dev) | Correlation with Yield | Lag Introduced (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Signal | 4.83 | 0.65 | 0 |

| Moving Average | 2.15 | 0.68 | 3 |

| Savitzky-Golay | 1.92 | 0.71 | 1 |

| Median Filter | 1.88 | 0.69 | 0 |

Experimental Workflow: ML for Process Data

ML Pipeline for Noisy Imbalanced Process Data

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Context |

|---|---|

| Savitzky-Golay Filter | A digital signal processing tool for smoothing noisy time-series data (e.g., pH, temperature) while preserving the width and height of waveform peaks, critical for identifying true process events. |

| SMOTEENN (imbalanced-learn) | A Python library class that combines synthetic oversampling and intelligent undersampling to create a balanced dataset, crucial for learning from rare fault events. |

| CORAL (CORrelation Alignment) | A domain adaptation algorithm that linearly transforms the source (pilot) features to match the covariance of the target (manufacturing) features, reducing distribution shift. |

| XGBoost Classifier | A gradient boosting algorithm with built-in regularization and native support for handling imbalanced data via the scale_pos_weight parameter, providing robust, non-linear models. |

| Leave-One-Group-Out CV | A cross-validation scheme where each unique batch ID is held out as a test set once. This is the gold standard for batch process data to avoid optimistic bias and test generalizability. |

| Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) | A single metric ranging from -1 to +1 that provides a reliable statistical rate for binary classification, especially on imbalanced datasets, considering all four quadrants of the confusion matrix. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Bayesian Optimization for Formulation Experiments

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: The optimization is stuck on a local optimum and isn't exploring new formulation regions. How can I increase exploration?

A: Increase the value of the acquisition function's exploration parameter (e.g., kappa in Upper Confidence Bound or xi in Expected Improvement). Decrease the length-scale prior in your kernel function to make the model less smooth, allowing it to capture more abrupt changes in polymer properties.

Q2: My experimental noise is high, leading to unreliable model predictions. How should I configure the Gaussian Process?

A: Explicitly model the noise by setting and optimizing the alpha or noise_level parameter in the Gaussian Process Regressor. Consider using a Matern kernel (e.g., nu=2.5) instead of the Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel, as it is better suited for handling noisy data.

Q3: The optimization suggests impractical formulations that violate material compatibility constraints. How do I incorporate constraints? A: Use a constrained Bayesian Optimization approach. You can model the constraint as a separate Gaussian Process classifier (for binary constraints) or regressor (for continuous constraints). The acquisition function is then multiplied by the probability of satisfying the constraint. Popular libraries like BoTorch and Ax provide built-in support for constrained optimization.

Q4: How many initial Design of Experiments (DOE) points are needed before starting the Bayesian Optimization loop for a polymer blend? A: A rule of thumb is 5-10 points per input dimension. For a formulation with 4 critical components (e.g., polymer ratio, plasticizer %, filler %, curing agent), start with 20-40 initial DOE points using a space-filling design like Latin Hypercube Sampling to build a reasonable prior model.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Convergence Failure or Erratic Performance

- Check Data Scaling: Ensure all input variables (formulation percentages) are scaled to the same range (e.g., [0,1]). Output variables (e.g., tensile strength, viscosity) should also be standardized.

- Verify Kernel Choice: For continuous variables (ratios, temperatures), use RBF or Matern kernels. For categorical variables (polymer type, catalyst choice), use a Hamming distance-based kernel.

- Review Acquisition Function: Switch from Expected Improvement (EI) to Probability of Improvement (PI) for more exploitation, or to Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) for more exploration if progress stalls.

- Examine Hyperparameters: Re-optimize the GP hyperparameters (length scale, noise) after each iteration or use a kernel that automatically adapts.

Issue: Long Computation Time with High-Dimensional Formulations

- Implement Dimensionality Reduction: Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on historical formulation data to identify the most influential components for active optimization.

- Use Sparse Models: Employ sparse Gaussian Process regression methods (e.g., using inducing points) to reduce computational complexity from O(n³) to O(m²n), where m is the number of inducing points.

- Parallelize Evaluations: Use a batch acquisition function (e.g., q-EI, q-UCB) to propose multiple formulations for parallel experimental testing in a single iteration.

Data Presentation: Performance Comparison of Optimization Algorithms

Table 1: Algorithm Performance in Optimizing Polymer Tensile Strength (Simulated Benchmark)

| Algorithm | Number of Experiments to Reach Target | Best Tensile Strength (MPa) Found | Computational Time per Iteration (s) | Handles Noise Well? |

|---|---|---|---|---|