High-Throughput Screening for Polymer Discovery: Accelerating Materials for Biomedicine and Beyond

High-throughput screening (HTS) has revolutionized polymer discovery by enabling the rapid testing of thousands to billions of materials, drastically accelerating the development of novel polymers for drug delivery, energy storage,...

High-Throughput Screening for Polymer Discovery: Accelerating Materials for Biomedicine and Beyond

Abstract

High-throughput screening (HTS) has revolutionized polymer discovery by enabling the rapid testing of thousands to billions of materials, drastically accelerating the development of novel polymers for drug delivery, energy storage, and biomaterials. This article explores the foundational principles of HTS, detailing advanced methodological approaches from automated synthesis to cell-based assays. It addresses key challenges in data interpretation and scalability, while showcasing how machine learning and AI are optimizing these processes. Finally, it examines the rigorous validation of HTS discoveries through high-fidelity simulations and market analysis, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive roadmap for integrating HTS into their material development workflows.

What is High-Throughput Screening? Core Principles and the Polymer Discovery Challenge

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) represents a foundational methodology in modern scientific research, enabling the rapid experimental analysis of thousands to millions of chemical or biological compounds. This paradigm has revolutionized drug discovery and materials science by allowing researchers to efficiently navigate vast experimental landscapes. Within polymer discovery research, HTS provides a systematic framework for unraveling complex structure-property relationships in soft materials, overcoming the limitations of traditional rational design approaches when dealing with high-dimensional feature spaces [1]. The core principle of HTS involves the miniaturization and automation of assays, combined with sophisticated data analysis, to accelerate the identification of lead compounds or materials with desired characteristics [2]. This article delineates the quantitative landscape, experimental protocols, and practical implementation of HTS workflows specifically contextualized for macromolecular research.

Market Context and Quantitative Landscape

The adoption of HTS technologies continues to expand significantly across pharmaceutical and materials research sectors. Current market analyses project substantial growth, with the global HTS market expected to reach USD 82.9 billion by 2035, advancing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10.0% from 2025 valuations of USD 32.0 billion [3]. Another analysis specifies growth from USD 18.8 billion during 2025-2029 at a CAGR of 10.6% [4]. This growth is primarily driven by increasing R&D investments, technological advancements in automation, and the pressing need for efficient drug discovery pipelines.

Table 1: High-Throughput Screening Market Segmentation and Growth Trends

| Segment | Market Share/Forecast | Key Drivers and Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Leading Technology | Cell-Based Assays (39.4% share) [3] | Provides physiologically relevant data; enables direct assessment of compound effects in biological systems [3]. |

| Leading Application | Primary Screening (42.7% share) [3] | Essential for identifying active compounds from large chemical libraries in initial drug discovery phases [3]. |

| Emerging Technology | Ultra-High-Throughput Screening (uHTS) (12% CAGR) [3] | Capable of screening millions of compounds rapidly; leverages advanced automation and microfluidics [2] [3]. |

| Key Regional Markets | United States (12.6% CAGR), China (13.1% CAGR), South Korea (14.9% CAGR) [3] | Strong biotechnology sectors, government initiatives, and growing R&D investments fuel regional growth [4] [3]. |

North America currently dominates the global market, contributing approximately 50% to global growth, supported by well-established biomedical research infrastructure, robust networks of academic institutions, and regulatory frameworks that foster innovation [4].

HTS Workflow Design for Polymer Discovery

Implementing HTS within polymer research requires a strategic workflow designed to efficiently explore high-dimensional design spaces where multiple variables (e.g., composition, architecture, molecular weight) interact complexly [1]. The universal workflow can be deconstructed into several critical steps that transform a scientific question into predictive models or optimized materials.

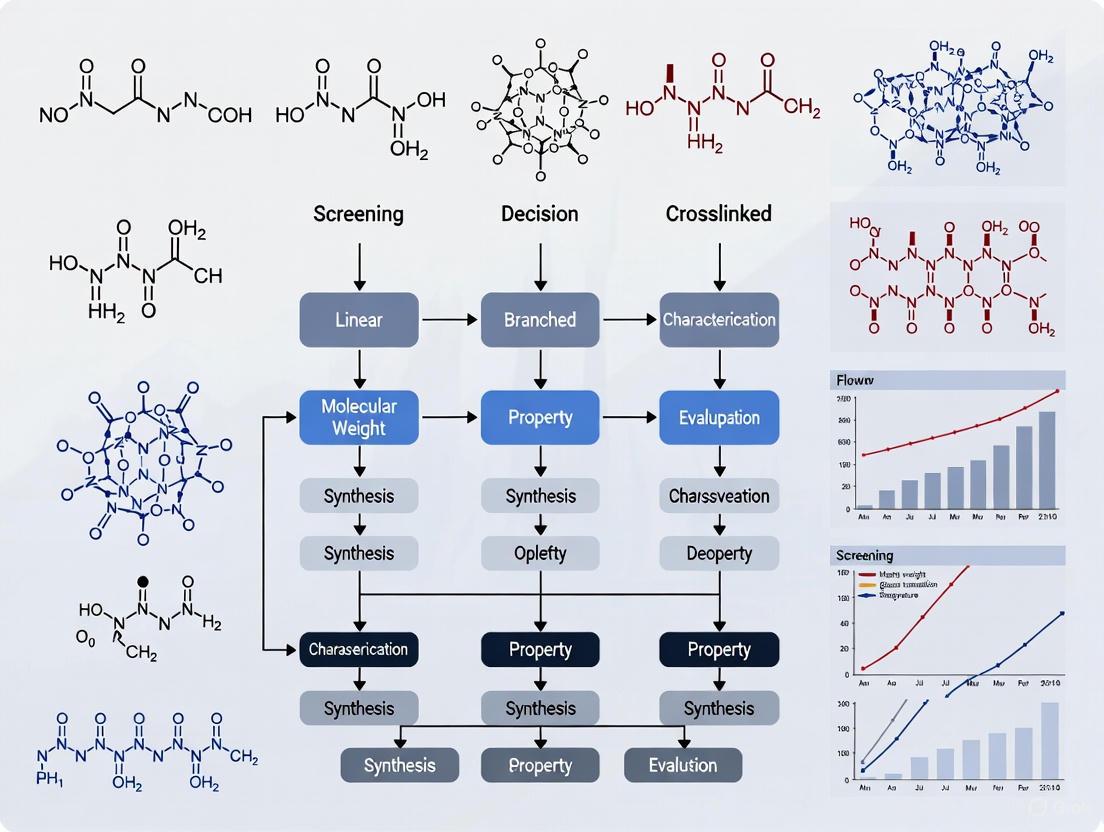

Diagram 1: HTS Workflow for Polymer Discovery. This map outlines the iterative process from objective definition to hit validation or model building.

The initial step involves clearly defining the scientific objective, which typically falls into one of two categories: optimization (finding the highest-performing material) or exploration (mapping structure-property relationships to build predictive models) [1]. As illustrated in Diagram 1, the subsequent path diverges based on this objective.

- Optimization Focus: The goal is to identify "champion" materials by navigating a performance landscape, seeking peaks of high performance while avoiding valleys of poor performance. Success is measured by identifying a material that exceeds a predefined performance threshold [1].

- Exploration Focus: The goal is to generate a comprehensive data set that captures the entire feature space, including both high and low performers, to build quantitative structure-property relationship (QSPR) models. The primary challenge is the "curse of dimensionality," requiring larger, more representative library sizes to create predictive models [1].

Following objective definition, feature selection identifies relevant variables, which for polymers include intrinsic descriptors (composition, architecture, sequence, molecular weight) and extrinsic descriptors (sample preparation protocols, substrate choices) [1]. The selected features are then bounded and discretized to estimate the total size of the design space, guiding the selection of an appropriate library synthesis method.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Biochemical FRET-Based Protease Assay (1536-Well Format)

This protocol details a quantitative HTS (qHTS) approach for identifying enzyme inhibitors, adapted from antiviral discovery research for application in screening polymer libraries for catalytic activity or bioactivity [5].

1. Principle: A fluorogenic peptide substrate containing a specific cleavage site is labeled with a fluorophore and quencher pair. Proteolytic cleavage separates the pair, generating a measurable fluorescence increase. Inhibition of the enzyme reduces the fluorescence signal.

2. Reagents and Materials:

- Recombinant enzyme (e.g., protease domain or full-length protein)

- Fluorogenic peptide substrate (e.g., 15-amino acid peptide with TAMRA/QSY7 pair)

- Assay buffer (optimized for pH and ionic strength)

- Test compounds (polymer libraries in DMSO solution)

- Positive control inhibitor (e.g., ZnAc for specific proteases)

- 1536-well microplates

3. Equipment:

- Automated liquid handling robot

- Fluorescence microplate reader

- Incubator

4. Procedure:

- Step 1: Using an automated dispenser, transfer 2 µL of assay buffer into each well of the 1536-well plate.

- Step 2: Dispense 10 nL of test polymer compounds or controls into respective wells using a nanoliter pintool.

- Step 3: Add 2 µL of enzyme solution (e.g., 150 nM truncated protease or 80 nM full-length enzyme in assay buffer) to all wells. Centrifuge briefly to mix.

- Step 4: Initiate the reaction by adding 2 µL of peptide substrate (e.g., 5 µM final concentration) in buffer.

- Step 5: Incubate the plate at room temperature for a predetermined time (e.g., 30-60 minutes), protected from light.

- Step 6: Measure fluorescence intensity (excitation/emission: ~540 nm/~580 nm for TAMRA) using a plate reader.

5. Data Analysis:

- Calculate normalized response:

(Fluorescence_sample - Fluorescence_negative_control) / (Fluorescence_positive_control - Fluorescence_negative_control) × 100 - Generate concentration-response curves for qHTS analysis.

- Fit data to a four-parameter Hill model to determine IC₅₀ values for inhibitory compounds [6].

Protocol: Cell-Based Cytotoxicity Screening (1536-Well Format)

This protocol measures compound-mediated cytotoxicity, applicable for profiling the biocompatibility of polymer libraries [6].

1. Principle: The CellTiter-Glo Luminescent assay quantifies intracellular ATP, an indicator of metabolic activity and cell viability. Cytotoxic compounds decrease ATP levels, reducing luminescent signal.

2. Reagents and Materials:

- Cell line of interest (e.g., human HepG2, HEK 293)

- Cell culture medium

- CellTiter-Glo Reagent

- Test polymer compounds

- Doxorubicin or Tamoxifen (positive control)

- 1536-well white-walled microplates

3. Equipment:

- Automated plate washer and dispenser

- Luminescence microplate reader

- CO₂ incubator

4. Procedure:

- Step 1: Seed cells in 2 µL medium at optimal density (e.g., 1,000-2,000 cells/well) into 1536-well plates. Incubate for 4-24 hours.

- Step 2: Pin-transfer 10 nL of test compounds or controls into wells.

- Step 3: Incubate plates for 48-72 hours at 37°C, 5% CO₂.

- Step 4: Equilibrate plates to room temperature for 30 minutes.

- Step 5: Add 2 µL of CellTiter-Glo Reagent to each well.

- Step 6: Shake plates orbially for 2 minutes, then incubate for 10 minutes to stabilize signal.

- Step 7: Measure luminescence on a compatible plate reader.

5. Data Analysis:

- Normalize data to plate-based vehicle controls (0% inhibition) and positive controls (100% inhibition).

- Apply statistical normalization to remove plate location bias [6].

- Model concentration-response relationships using the Hill function to determine AC₅₀ values [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for HTS Workflows

| Reagent/Material | Function and Application in HTS | Specific Examples and Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Assay Kits & Reagents | Pre-optimized biochemicals for specific readouts; ensure reproducibility and reduce setup time [3]. | CellTiter-Glo for viability [6]; FRET-based peptide substrates for protease activity [5]; specialized polymer reagent formulations. |

| Microplates | Miniaturized assay platforms for high-density screening; enable automation and reduce reagent volumes. | 1536-well plates for uHTS [5] [6]; 384-well plates for standard HTS; white plates for luminescence, black plates for fluorescence. |

| Automated Liquid Handlers | Robotic precision dispensing of nanoliter to microliter volumes; essential for reproducibility and throughput [2]. | Instruments for compound reformatting, assay assembly, and reagent addition; capable of handling 1536-well formats [5]. |

| Detection Instruments | Measure assay signal outputs (e.g., fluorescence, luminescence); high-sensitivity for miniaturized volumes. | Fluorescence microplate readers with appropriate filters; luminescence detectors; high-content imaging systems for complex phenotypes. |

| Chemical Libraries | Structurally diverse compound collections for screening; foundation for hit identification. | Drug repurposing libraries (~9,000 compounds) [5]; medicinal chemistry-focused collections (~25,000 compounds) [5]; combinatorial polymer libraries. |

| Data Analysis Software | Statistical analysis and visualization of large screening datasets; triage of false positives and hit identification. | Tools for concentration-response modeling [6]; machine learning platforms for QSPR [1]; cheminformatics software for compound management. |

Data Analysis and Hit Identification Strategies

The massive datasets generated by HTS campaigns require sophisticated statistical approaches for reliable interpretation. A critical first step involves data normalization to remove systematic biases, such as plate location effects or inter-plate variability [6]. For qHTS, where compounds are tested at multiple concentrations, the Hill model is widely used to fit concentration-response relationships and derive key parameters, including potency (AC₅₀ or IC₅₀) and efficacy (maximal response) [6].

Diagram 2: HTS Data Analysis Pipeline. This flowchart shows the statistical pathway from raw data to compound classification.

As shown in Diagram 2, the analysis pipeline progresses from raw data to validated hits through several filtering stages. Statistical tests for significant concentration-response relationships and quality of fit are applied to categorize compounds into activity classes (e.g., active, inactive, inconclusive) [6]. Hit triage strategies then rank outputs based on the probability of success, employing expert rule-based filters or machine learning models to identify and eliminate false positives arising from assay interference, chemical reactivity, or colloidal aggregation [2].

For polymer research, active compounds identified through this pipeline feed directly into the iterative workflow shown in Diagram 1, informing subsequent library design and synthesis cycles to refine structure-property relationships [1].

High-Throughput Screening has evolved into an indispensable methodology for navigating the complex design spaces inherent to polymer discovery and drug development. The integration of automated, miniaturized assays with rigorous statistical analysis and data management creates a powerful pipeline for accelerating materials development and target identification. As the field advances, the convergence of uHTS technologies, sophisticated machine learning analytics, and shared database resources will further enhance our ability to decode intricate structure-property relationships. For polymer scientists, embracing these HTS principles and protocols provides a systematic pathway to overcome the challenges of macromolecular design, ultimately enabling the discovery of next-generation functional materials with tailored properties.

The development of new polymers with tailored properties is a cornerstone of advancements in healthcare, drug delivery, and materials science. However, the traditional research paradigm, heavily reliant on experience-driven trial-and-error, presents a fundamental bottleneck in molecular discovery. This approach is inherently inefficient, often costly, and limited in its ability to navigate the vast, high-dimensional chemical space of potential polymers [7]. The workflow from concept to viable polymer typically spans more than a decade, requiring substantial research and development investment [7]. This inefficiency stems from the immense structural diversity of polymers, which exhibit complexity at multiple levels—from atomic connectivity and chain packing to morphological features like crystallinity and phase separation [8]. Navigating this complex domain with conventional methods significantly restricts the speed and innovative potential of polymer discovery.

The Core Bottlenecks in Traditional Methodologies

The Inefficiency of Edisonian Approaches

The conventional "Edisonian" approach to polymer development is characterized by iterative, manual experimentation guided largely by researcher intuition and conceptual insights. This process is not only slow and costly but is also often biased toward familiar domains of chemical space, potentially overlooking highly promising but non-intuitive compounds [9]. The inability to systematically explore the immense polymer universe means that the probability of stumbling upon optimal candidates, especially for complex applications like drug delivery systems or competitive protein inhibitors, is exceedingly low.

Specific Experimental Hurdles in OBOC Screening

The "one-bead one-compound" (OBOC) combinatorial method exemplifies the challenges of traditional screening. It allows for the synthesis of bead-based libraries containing millions to billions of synthetic compounds but faces two major hurdles that have historically limited its practical application to libraries of only thousands to hundreds of thousands of compounds [10]:

- Screening Throughput: The commercially available technology with the highest throughput for bead screening is fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), which has a theoretical throughput of approximately 100 million beads in a 10-hour period. In practice, however, screening libraries larger than 1 million compounds requires pre-enrichment via pull-down methods to reduce the bead count to a manageable 10,000-50,000 before FACS can be applied cost-effectively [10].

- Hit Sequencing: After identifying a "hit" bead with desired binding properties, determining the polymer's chemical sequence is crucial. For traditional α-amino acid peptides, techniques like Edman degradation or LC-MS/MS are used. However, these methods do not translate well to novel non-natural polymers and typically require large bead sizes (>90 μm) containing over 100 picomoles of polymer to ensure sufficient material for analysis. This requirement makes large libraries prohibitively expensive in terms of material costs [10].

Table 1: Key Bottlenecks in Traditional "One-Bead One-Compound" (OBOC) Screening

| Bottleneck | Traditional Challenge | Impact on Library Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Screening Throughput | Practical FACS screening limited without pre-enrichment steps [10]. | Libraries historically limited to ~10^4-10^5 compounds [10]. |

| Hit Sequencing | Requires large beads (>90 μm) with >100 pmol of polymer for analysis [10]. | Material costs become prohibitive for large libraries of high-MW polymers [10]. |

| Material & Cost | Large bead sizes and low-throughput sequencing increase cost per data point. | Constrains library diversity and innovation potential. |

High-Throughput Solutions and Experimental Protocols

Mega-High-Throughput Screening with FAST

A transformative technology for overcoming the screening bottleneck is the Fiber-Optic Array Scanning Technology (FAST). Originally developed for detecting rare circulating tumor cells in blood, FAST has been adapted for ultra-high-throughput screening of bead-based polymer libraries [10].

Key Protocol Steps for FAST Screening:

- Library Preparation: Synthesize a combinatorial library of sequence-defined non-natural polymers (e.g., polyamides) on TentaGel beads with diameters of 10-20 μm using the mix-and-split OBOC method [10].

- Target Incubation: Incubate the bead library with the fluorescently labeled protein target of interest (e.g., K-Ras, IL-6, TNFα). Use fluorophores like Alexa Fluor 555, which emit in the yellow/orange spectrum, to minimize interference from bead autofluorescence [10].

- Bead Plating: Plate the beads as a monolayer on a 108 x 76 mm glass slide at an optimized density:

- 5 million beads per plate for 10 μm beads.

- 2.5 million beads per plate for 20 μm beads. This ensures well-dispersed beads for automated analysis and subsequent picking [10].

- FAST Scanning: Scan the plate using the FAST system. A 488 nm laser excites the fluorophores, and emitted fluorescence is collected through a fiber-optic bundle. The system measures emissions at two different wavelengths (e.g., 520 nm and 580 nm) to differentiate true positive signals from autofluorescence [10].

- Hit Identification and Picking: The system records the Cartesian coordinates of fluorescently labeled beads with an ~8 μm resolution. Positive hit beads are then automatically picked for downstream sequencing [10].

Performance: This platform can screen bead-based libraries at a rate of 5 million compounds per minute (approximately 83,000 Hz), achieving a detection sensitivity of over 99.99% [10]. This allows for the practical screening of libraries containing up to a billion compounds.

Advanced Sequencing for Non-Natural Polymers

For the sequencing bottleneck, a sensitive method is required to determine the chemical structure of hits from single beads as small as 10 μm in diameter.

Key Protocol Steps for Sequencing:

- Hit Bead Isolation: Following FAST screening, individually pick the hit beads identified by their coordinates.

- Chemical Cleavage and Processing: Subject the single bead to chemical fragmentation processes tailored to the polymer's backbone chemistry. This step breaks the polymer into smaller, analyzable fragments.

- High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry: Analyze the fragments using high-resolution mass spectrometry (MS) at the femtomole scale. The fragmentation pattern and precise mass measurements allow for the reconstruction of the polymer's complete sequence without prior knowledge of the polymer backbone, making it suitable for novel non-natural polymers [10].

The Data-Driven Paradigm: AI and Machine Learning

Beyond physical screening technologies, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) represent a fundamental paradigm shift for overcoming the trial-and-error bottleneck.

Machine Learning in Polymer Design

Machine learning accelerates discovery by establishing complex, non-linear relationships between polymer structures and their macroscopic properties, enabling inverse design where polymers are designed to meet specific property targets [7] [8].

Key Workflow for ML-Assisted Discovery:

- Data Collection: Utilize existing polymer databases (e.g., PoLyInfo, PI1M, Khazana) as a foundation for model training. These databases contain structural information and property data (e.g., glass transition temperature Tg, melting temperature Tm, thermal conductivity) [8] [11].

- Feature Representation: Convert polymer chemical structures into machine-readable numerical descriptors or fingerprints. This can include molecular fingerprints, topological descriptors, or learned representations from graph-based models [7] [8].

- Model Training: Train ML models (e.g., Deep Neural Networks, Graph Neural Networks, Random Forests) to predict target properties from the structural descriptors. A prominent example is the prediction of the glass transition temperature (Tg), a key property for high-temperature polymers [9] [11].

- Virtual Screening and Inverse Design: Use trained models to screen vast virtual libraries of hypothetical polymers or to generate new polymer structures with desired properties using generative models and molecular design algorithms [11].

Case Study: One study used a Bayesian molecular design algorithm trained on limited data to identify thousands of hypothetical polymers with predicted high thermal conductivity. From these, three were synthesized and experimentally validated, achieving thermal conductivities of 0.18–0.41 W/mK, comparable to state-of-the-art thermoplastics [11]. This demonstrates a successful transition from in-silico prediction to laboratory validation.

Table 2: Key AI/ML Solutions for Polymer Discovery Bottlenecks

| Solution | Technology/Method | Application & Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Property Prediction | Deep Neural Networks (DNNs), Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [7]. | Predicts properties like glass transition temperature and modulus from structure, bypassing costly synthesis [7] [9]. |

| Inverse Design | Bayesian Molecular Design, Generative Models [11]. | Algorithmically designs novel polymer structures to meet specific, multi-property targets [11]. |

| Process Optimization | Reinforcement Learning (RL) [7]. | Automatically optimizes polymerization process parameters (e.g., temperature, catalyst), reducing experimental iterations. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for High-Throughput Polymer Discovery

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| TentaGel Beads (10-20 μm) | A common solid support for OBOC library synthesis. Their small size reduces material costs and enables high-density plating for FAST screening [10]. |

| FAST System | The core platform for ultra-high-throughput fluorescence-based screening of bead libraries at rates of millions per minute [10]. |

| Non-Natural Polymer Building Blocks | Diverse chemical monomers (e.g., non-α-amino acids) used to create libraries with vast chemical diversity beyond natural peptides [10]. |

| Alexa Fluor 555 (or CF555) | A fluorophore with emission properties that minimize interference from the autofluorescence of TentaGel beads, improving signal-to-noise ratio [10]. |

| High-Resolution Mass Spectrometer | Essential for sequencing the minimal amounts of polymer (femtomole scale) present on a single 10-20 μm hit bead [10]. |

| Machine Learning Platforms (e.g., Polymer Genome) | AI-driven informatics platforms for predicting polymer properties and performing virtual screening to prioritize candidates for synthesis [12]. |

Integrated Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated high-throughput workflow that combines advanced screening and AI to overcome traditional bottlenecks.

Diagram 1: High-throughput polymer discovery workflow.

The synergy between physical and computational screening is key. AI can design and pre-screen virtual libraries, guiding the synthesis of more focused and promising physical libraries for FAST screening, thereby creating a highly efficient discovery cycle.

The bottleneck in polymer discovery, long imposed by traditional trial-and-error methods, is being decisively overcome by a new generation of technologies. Integrated platforms that combine ultra-high-throughput physical screening using FAST, femtomole-scale sequencing, and data-driven AI design are creating a new paradigm. This convergence enables the practical exploration of billion-member polymer libraries and the rational discovery of non-natural polymers with high affinity and specific functionality against challenging biological targets. By adopting these integrated workflows, researchers can accelerate the development of innovative polymers for advanced therapeutics, diagnostics, and materials.

High-throughput screening (HTS) has emerged as a transformative approach in polymer discovery, enabling the rapid assessment of key properties critical for advanced applications in energy storage, biomedical devices, and flexible electronics. This paradigm shift from traditional trial-and-error methods to data-driven experimentation allows researchers to navigate vast combinatorial design spaces efficiently. The integration of machine learning with automated experimental systems has further accelerated the identification of polymer formulations with tailored characteristics. This document presents standardized application notes and protocols for screening three fundamental properties—ionic conductivity, mechanical strength, and biocompatibility—within the context of a comprehensive polymer discovery pipeline. These protocols are designed specifically for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in the development of next-generation polymeric materials.

Key Property Screening Data

The following tables consolidate quantitative data and performance metrics for polymeric materials screened across the three target properties, providing a reference framework for research and development initiatives.

Table 1: Ionic Conductivity Screening Data for Electrolyte Materials

| Material System | Screening Method | Performance (Ionic Conductivity) | Reference/Model Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| LiFSI-based liquid electrolytes [13] | Generative AI & experimental validation | 82% improvement over baseline [13] | SMI-TED-IC model [13] |

| LiDFOB-based liquid electrolytes [13] | Generative AI & experimental validation | 172% improvement over baseline [13] | SMI-TED-IC model [13] |

| Doped LiTi₂(PO₄)₃ solid electrolytes [14] | Machine Learning (DopNet-Res&Li) & AIMD validation | Predicted: Up to 1.12 × 10⁻² S/cm for Li₂.₀B₀.₆₇Al₀.₃₃Ti₁.₀(PO₄)₃ [14] | DopNet-Res&Li model (R² = 0.84) [14] |

| Polymer Electrolytes [15] | Automated HTS (SPOC platform) | Modified amorphous character in semi-crystalline PEG-based systems [15] | Studying-Polymers-On-a-Chip (SPOC) [15] |

Table 2: Mechanical Property Screening Data for Structural Polymers

| Material System | Screening Method | Key Performance Outcome | Relevant Standards |

|---|---|---|---|

| PVA with HCPA cross-linker [16] | Tensile testing, SAXS, IR spectroscopy | 48% ↑ tensile strength, 173% ↑ strain at break, 370% ↑ toughness [16] | N/A |

| Liquid Crystalline Polyimides [17] | ML classification & experimental synthesis | Thermal conductivity: 0.722 - 1.26 W m⁻¹ K⁻¹ [17] | N/A |

| High-Performance Polymers [18] | Fatigue, Tensile, and DMA testing | Quantified endurance limits, stiffness (storage modulus), and glass transition [18] | ASTM D638, D790, D4065 |

Table 3: Biocompatibility Testing Matrix for Polymeric Biomaterials

| Test Category | Specific Assays | Application Context | Governing Standards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical/Chemical Tests [19] | Strength, stability, ethylene oxide residue, substance release [19] | All medical device categories [20] | ISO 10993 [19] [20] |

| In-Vitro Tests [19] | Cytotoxicity, cell adhesion, blood compatibility, genetic toxicity, endotoxin testing [19] | Initial safety screening [20] | ISO 10993 [19] [20] |

| In-Vivo Tests [19] | Irritation, sensitization, implantation, systemic toxicity [19] | Surface devices, external communicating devices, implants [20] | ISO 10993 [19] [20] |

| Cationic Polymers for mRNA Delivery [21] | Cellular uptake, cytotoxicity, mRNA transfection efficiency [21] | Polymer-based mRNA delivery systems [21] | N/A |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for High-Throughput Ionic Conductivity Screening

Principle: This protocol uses a machine-learning-guided workflow to discover novel electrolyte formulations with high ionic conductivity, fine-tuning a chemical foundation model on a curated dataset of experimental measurements [13].

Materials:

- SMI-TED-IC Model: A fine-tuned chemical foundation model for ionic conductivity prediction [13].

- Literature Dataset: A curated set of 13,666 electrolyte formulations with ionic conductivity values [13].

- SPOC Platform: An automated system for formulation and impedance characterization (optional for validation) [15].

Procedure:

- Model Fine-Tuning: Fine-tune the pre-trained SMI-TED model using the curated dataset of electrolyte formulations. Each formulation is represented by the canonical SMILES strings of its constituents and their respective concentration fractions [13].

- Virtual Screening: Use the fine-tuned model to screen a computationally generated library of candidate formulations (e.g., >100,000 candidates) [13].

- Candidate Selection: Identify top candidate formulations predicted to have significantly enhanced ionic conductivity.

- Experimental Validation: Synthesize the lead candidates and measure their ionic conductivity using standard impedance spectroscopy techniques. Automated platforms like the SPOC system can be employed for high-throughput validation [15].

Protocol for Screening Mechanics via Multiple Hydrogen-Bonded Networks

Principle: This protocol assesses the enhancement of mechanical strength and toughness in polymers (e.g., PVA) by incorporating small molecule cross-linkers (e.g., HCPA) that form multiple hydrogen-bonded networks [16].

Materials:

- Polymer Matrix: e.g., Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA).

- Cross-linker: e.g., HCPA molecule.

- Testing Equipment: Universal testing machine, Rheometer, FTIR spectrometer, SAXS instrument, Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM), Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC).

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare PVA films with varying concentrations of HCPA (e.g., 1, 5, 10 wt%) [16].

- Tensile Testing: Measure stress-strain curves to determine tensile strength, elongation at break, and toughness [18] [16].

- Structural Analysis:

- Thermal and Rheological Characterization:

Protocol for Biocompatibility Assessment of Polymer-Based Materials

Principle: This protocol outlines a standardized biological safety evaluation for polymers intended for medical applications, following the ISO 10993 framework [19] [20].

Materials:

- Test Article: A finished, sterilized representative sample of the polymer device.

- Extraction Media: Physiological saline, vegetable oil, DMSO, ethanol, or cell-culture medium.

- Biological Systems: Cell cultures for in-vitro tests (e.g., murine fibroblasts for cytotoxicity); appropriate animal models for in-vivo tests.

Procedure:

- Device Characterization: Define the device category (surface, externally communicating, implant) and contact duration (limited, prolonged, permanent) based on intended use [20].

- Test Selection: Refer to the ISO 10993-1 matrix to identify required tests (e.g., cytotoxicity, sensitization, irritation, systemic toxicity, implantation) for the device category [20].

- Sample Preparation (Extraction):

- Extract the test article at 37°C for 24-72 hours using relevant media.

- Maintain a surface area-to-volume ratio of 1.25-6 cm²/mL [20].

- Test Execution:

Workflow Visualization

The diagram above illustrates the integrated high-throughput screening workflow for evaluating key polymer properties. This parallel processing approach enables rapid iteration and data-driven decision-making, significantly accelerating the discovery timeline for advanced polymeric materials.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for High-Throughput Polymer Screening

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Foundation Models [13] | Predicts formulation properties from chemical structure (SMILES). | SMI-TED-IC model for ionic conductivity [13]. |

| High-Throughput Screening Platforms [15] | Automates formulation, characterization, and data collection. | SPOC (Studying-Polymers-On-a-Chip) platform [15]. |

| Polymer Cross-linkers [16] | Enhances mechanical strength and toughness via dynamic bonds. | HCPA for PVA; forms multiple H-bond networks [16]. |

| Standardized Test Materials [20] | Provides positive/negative controls for biocompatibility assays. | Reference materials per ISO 10993-12 [20]. |

| Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer (DMA) [18] | Measures viscoelastic properties (storage/loss modulus) vs. temperature. | Essential for fatigue and thermomechanical analysis [18]. |

| RDKit & XenonPy [17] | Calculates molecular descriptors from polymer chemical structures. | Used for featurization in ML-based discovery [17]. |

The Role of Automation and Miniaturization in Enabling HTS

In modern polymer discovery and drug development, High-Throughput Screening (HTS) has become an indispensable methodology for rapidly evaluating vast libraries of compounds. The efficiency and scalability of HTS are fundamentally enabled by two interconnected technological pillars: automation and miniaturization. Automation replaces manual, variable-prone laboratory processes with robotic systems that operate with precision around the clock, while miniaturization drastically reduces assay volumes to conserve precious reagents and samples [22]. Together, these approaches transform polymer research from a sequential, low-output endeavor into a parallel, data-rich scientific process. This application note details the practical implementation of automated, miniaturized HTS platforms, with a specific focus on their transformative impact in polymer therapeutics discovery research.

Automation in HTS: Integrated Robotic Platforms

Automation in HTS involves the integration of robotic systems to manage all aspects of the screening workflow, from sample preparation and liquid handling to incubation and data acquisition. This creates a continuous, operator-independent process that maximizes throughput and data consistency.

Core Components of an Automated HTS Platform

A fully integrated automated HTS platform comprises several modular workstations linked by a robotic arm or conveyor system. The key modules and their functions are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Core Modules in an Integrated Automated HTS Platform

| Module Type | Primary Function | Key Requirement in HTS |

|---|---|---|

| Robotic Liquid Handler | Precise fluid dispensing and aspiration | Sub-microliter accuracy; low dead volume [22] |

| Plate Incubator | Temperature and atmospheric control | Uniform heating/cooling across microplates [22] |

| Microplate Reader | Signal detection (e.g., fluorescence, luminescence) | High sensitivity and rapid data acquisition [22] [23] |

| Plate Washer | Automated washing cycles | Minimal residual volume and cross-contamination control [22] |

| Central Scheduler Software | Orchestrates timing and sequencing of all actions | Enables 24/7 continuous operation [22] |

Protocol: Operator-Independent Polymerization Screening

Background: Traditional polymerization screening protocols are time-consuming and susceptible to operator bias, creating a bottleneck in establishing quantitative structure-property relationships (QSPRs) [24] [25]. This protocol describes an automated, continuous-flow platform for kinetic studies of polymerizations, such as Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain Transfer (RAFT) polymerization.

Materials:

- Automated synthesis platform with continuous flow reactors

- Inline NMR spectrometer

- Online Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) system

- Custom software for autonomous system control and data acquisition

Method:

- System Setup: Configure the continuous flow system with integrated real-time analytics (inline NMR, online SEC). The software is programmed with the desired reaction parameters and analysis schedule [24].

- Reaction Execution: Initiate the polymerization reactions autonomously within the flow system. The platform precisely controls reactant mixing, temperature, and residence times.

- Real-Time Monitoring: The inline NMR probe acquires data on monomer conversion kinetics continuously. Simultaneously, the online SEC system periodically samples the reaction stream to determine molecular weight distributions [24].

- Data Handling: Automated algorithms process the raw analytical data, detect experimental inaccuracies, and clean the data. The final, structured data is aggregated in a machine-readable format for subsequent analysis [24].

Application Note: This platform enabled 8 different operators, from students to professors, to generate a coherent dataset of 3600 NMR spectra and 400 molecular weight distributions for 8 different monomers. The operator-independent nature of the platform eliminated individual user biases, resulting in a high-quality, consistent "big data" set for kinetic analysis [24].

Miniaturization in HTS: Scaling Down for a Big Impact

Miniaturization involves scaling down assay volumes from traditional microliter scales to nanoliter or even picoliter volumes, typically using high-density microplates (384-, 1536-well) or microfluidic devices [26] [27] [28].

Quantitative Benefits of Assay Miniaturization

The transition to smaller assay formats yields direct and significant cost savings and efficiency gains, particularly when screening valuable compound libraries or primary cells.

Table 2: Economic and Practical Impact of Assay Miniaturization

| Parameter | 96-Well Format | 384-Well Format | 1536-Well Format | Microfluidic Device |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Assay Volume | ~100-200 μL [27] | ~10-50 μL [27] | ~1-5 μL [27] [23] | ~1 μL or less [29] |

| Cell Requirement (for 3,000 data points) | ~23 million cells [26] | ~4.6 million cells [26] | Further reduction | ~300 cells per compartment [29] |

| Cost Implication | Baseline | Significant savings on reagents and cells [26] | Further cost savings | ~150-fold lower reagent usage; estimated savings of $1-2 per data point [29] |

Protocol: High-Content Screening (HCS) in a Microfluidic Format

Background: HCS in traditional multi-well plates is hindered by inefficient usage of expensive reagents and precious primary cells. Microfluidics technology offers a path to extreme miniaturization for complex cell-based assays [29].

Materials:

- Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) microfluidic device with 32 separate compartments and integrated membrane valves.

- Automated system for valve actuation and fluid control.

- Motorized fluorescence microscope or scanner.

- Primary cells or cell lines, staining reagents, and compounds for screening.

Method:

- Device Priming: Load a suspension of approximately 300 cells into each compartment of the microfluidic device [29].

- Stimulation: Using the automated valve control system, expose each compartment to different combinations or concentrations of exogenously added factors (e.g., polymer therapeutics, drugs) for defined periods. The system can generate complex temporal stimuli, such as periodic pulses [29].

- Staining and Fixation: Automatically introduce fixative and immunocytochemical staining reagents into the compartments via the fluidic network.

- Imaging and Analysis: Image the cells using a motorized microscope. Analyze images to determine readouts such as protein localization, cell shape, and signaling pathway activation. Statistical significance is achieved by comparing distributions across hundreds of cells per condition [29].

Application Note: This microfluidic HCS platform has been used to study signaling dynamics in the TNF-NF-κB pathway and to identify off-target effects of kinase inhibitors. Its ability to perform detailed, time-varying stimulation experiments with minimal reagent consumption makes it ideal for probing complex biological responses to polymer therapeutics [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of automated and miniaturized HTS relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HTS in Polymer Discovery

| Item | Function/Application | Relevance to HTS |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density Microplates (384-, 1536-well) | The physical platform for miniaturized assays in a standard footprint [27] [23]. | Enables parallel processing and significant reagent savings; compatible with automated liquid handlers and readers. |

| TR-FRET/HTRF Assay Kits | Homogeneous, mix-and-read assays for studying biomolecular interactions (e.g., protein-protein, ligand-receptor) [26] [23]. | Robust, miniaturization-friendly readouts that are easily automated. The TR-FRET laser on readers like the PHERAstar FSX allows ultra-fast measurement of 1536-well plates [23]. |

| Polymer Libraries (for PIHn) | Arrays of distinct polymers used as heteronucleants to promote the crystallization of different polymorphs [30]. | A high-throughput method for exhaustive polymorph screening of new polymer therapeutics, using only ~1 mg of material [30]. |

| I.DOT Non-Contact Liquid Handler | An automated dispenser for accurate transfer of nanoliter volumes [28]. | Critical for reliable miniaturization, enabling low-volume assay setup in 1536-well plates or on custom microfluidic chips without cross-contamination. |

Visualizing HTS Workflows and Miniaturization Benefits

The integration of automation and miniaturization creates a streamlined, high-efficiency workflow. The following diagram illustrates this seamless process from sample preparation to data analysis.

Diagram 1: Integrated HTS Workflow. This diagram shows the seamless integration of automated modules, orchestrated by a central scheduler, with miniaturization enabling key steps in the process.

The decision to miniaturize an assay is driven by a clear set of advantages and technical considerations, which are mapped out below.

Diagram 2: Miniaturization Drivers and Enablers. A logic map showing the primary motivations for assay miniaturization and the critical technologies required to implement it successfully.

HTS in Action: Techniques, Technologies, and Real-World Applications

Automated synthesis involves the use of robotic equipment and software control to perform chemical synthesis, significantly enhancing efficiency, reproducibility, and safety in research and industrial settings [31]. Within polymer science, the advent of air-tolerant polymerization techniques has been a pivotal development, enabling their integration with accessible robotic platforms on the benchtop without the need for stringent inert-atmosphere conditions [32]. This combination is particularly powerful for high-throughput screening and polymer discovery research, as it allows for the rapid generation of large, systematic polymer libraries to establish structure-property relationships [21] [32]. These Application Notes detail the protocols and resources for leveraging automated synthesis platforms to accelerate polymer discovery.

The Automated and Air-Tolerant Polymer Synthesis Platform

The robotic platform makes use of advanced liquid handling robotics commonly found in pharmaceutical laboratories to automatically calculate, combine, and catalyze reaction conditions for each new polymer design [32]. The core innovation enabling this open-air operation is the application of oxygen-tolerant controlled radical polymerization reactions, such as certain modes of Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain Transfer (RAFT) polymerization [32] [33]. This overcomes a major historical barrier to the automation of benchtop polymer synthesis.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues the essential reagents and materials required for establishing an automated, air-tolerant polymer synthesis workflow.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Automated Air-Tolerant Polymerization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| RAFT Agents | Controls the polymerization to produce polymers with well-defined structures, target molecular weights, and low dispersity [34]. | Synthesis of cationic polymers for mRNA delivery [21]. |

| Methacrylate Monomers | Provides a versatile monomer family for creating polymers with diverse properties. Tertiary amine-containing variants can impart cationic character [21]. | Building block for combinatorial polymer libraries [21]. |

| Thermal Initiators | Generates free radicals upon heating to initiate the polymerization reaction [35]. | Thermally initiated RAFT polymerization [35]. |

| Oxygen-Tolerant Catalyst Systems | Enables polymerization to proceed in the presence of air, which is critical for open-air robotic platforms [32]. | Enzymatic degassing (Enz-RAFT) or photoinduced electron/energy transfer RAFT (PET-RAFT) [33]. |

| Anhydrous Solvents | Reaction medium; purity is critical for achieving predictable polymerization kinetics and final polymer properties. | Polymerization of methacrylamide in water [35]. |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Automated High-Throughput Synthesis of a Cationic Polymer Library

This protocol describes the combinatorial synthesis of a library of tertiary amine-containing methacrylate-based cationic polymers via automated RAFT polymerization for screening mRNA delivery vectors [21].

Experimental Workflow:

Detailed Methodology:

Reagent Preparation:

- Prepare stock solutions of the methacrylate monomer, RAFT agent, and thermal initiator in an appropriate anhydrous solvent (e.g., DMF, DMSO) [21] [35]. The robotic system will use these for precise dispensing.

- Typical RAFT Agent: A trithiocarbonate-based RAFT agent (e.g., CTCA) can be used for (meth)acrylamide/acrylate monomers [35].

- Typical Initiator: A water-soluble azo-initiator such as ACVA is suitable for aqueous polymerizations [35].

Robotic Library Setup:

- The liquid-handling robot is programmed to dispense variable volumes of the stock solutions into an array of reaction vials (e.g., 12 mL screw-capped vials) [35].

- The robot automatically calculates and delivers reagents to achieve target molecular weights and monomer-to-RAFT agent ratios (

R_M) and initiator-to-RAFT agent ratios (R_I), thereby creating a library of polymers with diverse chemical characteristics [21] [32].

Automated Polymerization:

- After dispensing, the robot seals the vials and initiates the reaction by transferring the rack to a heated stirrer.

- Typical Reaction Conditions: The polymerization proceeds under air-tolerant conditions [32]. A representative thermal initiation is conducted at 80 °C for 260 minutes with stirring at 600 rpm [35].

Work-up and Purification:

- The robotic system quenches the reactions by rapid cooling.

- An automated purification step, such as precipitation, can be integrated. The robot adds the reaction mixture dropwise to a cold non-solvent (e.g., ice-cold acetone). The precipitate is then isolated via filtration and dried in vacuo [35] [32].

Polyplex Formation and Screening:

- The synthesized cationic polymers are complexed with mRNA to form polyplexes.

- The biological responses—including cellular uptake, cytotoxicity, and mRNA transfection efficiency—are evaluated using high-throughput screening assays [21].

Protocol 2: DoE-Optimized RAFT Polymerization of Methacrylamide

This protocol utilizes Design of Experiments (DoE) to efficiently optimize a thermally initiated RAFT solution polymerization, moving beyond the inefficient one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approach [35].

Logical Workflow for DoE Optimization:

Detailed Methodology:

Define Goal and Factors:

- Goal: Optimize the RAFT polymerization of methacrylamide (MAAm) for a specific target, such as minimum dispersity (Đ) and target molecular weight.

- Key Numeric Factors: Reaction temperature (

T), reaction time (t), ratio of monomer to RAFT agent (R_M), and ratio of initiator to RAFT agent (R_I) [35].

Select DoE Design:

- A Face-Centered Central Composite Design (FC-CCD) is an effective response surface methodology for this purpose [35].

- This design defines a set of experimental runs that systematically explores the defined factor space.

Execute Automated Synthesis Runs:

- The robotic platform is programmed to execute the series of polymerizations as specified by the DoE. An example reaction at center point conditions is [35]:

- Monomer: MAAm (533 mg, 6.26 mmol,

R_M= 350) - RAFT Agent: CTCA (5.6 mg, 18 µmol)

- Initiator: ACVA (31 µg, 1.12 µmol,

R_I= 0.0625) - Solvent: Water (3.000 g)

- Conditions: 80 °C for 260 minutes.

- Monomer: MAAm (533 mg, 6.26 mmol,

- The robotic platform is programmed to execute the series of polymerizations as specified by the DoE. An example reaction at center point conditions is [35]:

Analyze Data and Build Prediction Models:

- Responses like monomer conversion (by

1H NMR), theoretical (M_n,th) and apparent molecular weight, and dispersity (Đ) are measured for each run [35]. - Statistical software is used to fit the data and generate predictive mathematical models (equations) that accurately relate the factor settings to each response.

- Responses like monomer conversion (by

Validate Optimal Conditions:

- The models are used to identify the factor settings predicted to achieve the optimal result.

- A final validation polymerization is performed at these predicted conditions to confirm the model's accuracy.

Data Presentation and Analysis

The following table summarizes the key performance metrics and characterization data that should be collected from the synthesized polymer libraries to facilitate high-throughput analysis and comparison.

Table 2: Polymer Characterization Data from High-Throughput Screening

| Polymer ID | Monomer(s) | Target M_n (kDa) | Measured M_n (kDa) | Đ (Dispersity) | Key Performance Metric (e.g., Transfection Efficiency %) | Cytotoxicity (Relative to Control) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP-001 | DMAEMA | 25 | 28.5 | 1.12 | 85% | 110% |

| CP-002 | HPMA | 30 | 31.2 | 1.08 | 45% | 95% |

| CP-003 | NVP | 40 | 35.8 | 1.21 | 60% | 105% |

| CP-004 | AEMA | 20 | 18.9 | 1.15 | 92% | 125% |

| Benchmark (PEI) | - | - | - | - | 65% | 150% |

Note: DMAEMA: 2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate; HPMA: 2-Hydroxypropyl methacrylate; NVP: N-Vinylpyrrolidone; AEMA: 2-Aminoethyl methacrylate hydrochloride. Data in table is illustrative of the data structure used in high-throughput screening [21].

DoE Model Factors and Responses

For protocols utilizing Design of Experiments, the factors and their investigated ranges, along with the measured responses, should be clearly documented.

Table 3: Example Factors and Responses for a DoE-Optimized RAFT Polymerization

| Factor Name | Symbol | Low Level (-1) | Center Level (0) | High Level (+1) | Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | T | 70 | 80 | 90 | °C |

| Time | t | 120 | 260 | 400 | min |

| [M]:[RAFT] Ratio | R_M | 200 | 350 | 500 | - |

| [I]:[RAFT] Ratio | R_I | 0.025 | 0.0625 | 0.1 | - |

| Response Name | Symbol | Target | Observed Range | Units | |

| Monomer Conversion | X | Maximize | 25 - 95 | % | |

| Apparent M_n | M_n | Target | 5 - 45 | kDa | |

| Dispersity | Đ | Minimize | 1.05 - 1.30 | - |

Note: Adapted from a DoE study on RAFT polymerization of methacrylamide [35].

Application Note: High-Throughput Thermal Stability Screening for Polymer and Biologic Formulations

Thermal stability serves as a primary metric for evaluating the physical properties of proteins and polymeric materials in high-throughput screening pipelines. The determination of melting temperature (Tm) provides a critical indicator of thermodynamic equilibrium and structural integrity, essential for predicting stability under various conditions. This application note details the implementation of high-throughput differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) for rapid characterization of material stability, enabling data-driven stabilization in polymer design and biopharmaceutical development [36] [37].

Key Instrumentation and Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparison of High-Throughput Thermal Analysis Techniques

| Technique | Instrument/System | Sample Throughput | Key Metrics | Sample Volume | Temperature Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | TA Instruments RS-DSC | Up to 24 samples per run | Tm, ΔH (unfolding enthalpy) | 5-11 μL | 25°C to 100°C |

| Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) | Brevity (Brevibacillus system) | 384 samples in 4 days | Tm (melting temperature) | Not specified | Method-dependent |

| Plate-based Thermal Shifting | Various | 96, 384, or 1536-well formats | Tm, aggregation temperature | 50-200 μL | Typically 25°C to 99°C |

Experimental Protocol: High-Throughput DSC for Biologic Formulations

Materials and Equipment

- TA Instruments RS-DSC with NanoAnalyze software

- Disposable microfluidic chips (11 μL capacity)

- Purified protein or polymer samples (concentration range: 0.1-10 mg/mL)

- Reference buffer matching sample composition

- 96-well or 384-well sample plates for automated loading

Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Prepare samples in appropriate formulation buffers. Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove particulates.

- Instrument Calibration: Perform daily calibration using manufacturer-recommended standards (e.g., indium, water).

- Method Programming:

- Set temperature range according to sample requirements (typically 25°C to 100°C for biologics)

- Configure heating rate at 1°C/min for optimal resolution

- Establish baseline with reference buffer

- Loading and Run:

- Load samples using automated liquid handling system

- Insert microfluidic chips into instrument carousel

- Initiate method and monitor run progress via software interface

- Data Analysis:

- Process thermograms using NanoAnalyze software

- Identify Tm from peak transition temperature

- Calculate ΔH from integrated peak area

- Export data for statistical analysis

Workflow Visualization

Key Advantages in Polymer Discovery Research

The RS-DSC system enables dilution-free analysis of high-concentration biotherapeutics and polymer formulations, maintaining sample integrity throughout characterization. The implementation of disposable microfluidic chips eliminates cross-contamination and reduces cleaning requirements between runs. This approach significantly accelerates formulation screening cycles, reducing typical characterization time from weeks to days while providing high-quality thermodynamic data essential for predictive modeling of material stability [36].

Application Note: Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy for Solid-State Battery Materials

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) provides critical insights into the dynamics of various energy storage systems, particularly solid-state batteries (SSBs). This non-destructive operando characterization technique enables researchers to investigate ionic transport mechanisms, interface interactions, and charge transfer phenomena at electrode-electrolyte interfaces. For high-throughput polymer discovery in energy applications, EIS serves as an indispensable tool for screening solid-state electrolytes and composite materials [38] [39].

Key Parameters and Equivalent Circuit Modeling

Table 2: Critical EIS Parameters for Solid-State Battery Characterization

| Parameter | Symbol | Physical Meaning | Typical Range (SSBs) | Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ohmic Resistance | Rohm | Ionic resistance of electrolyte | 10-100 Ω·cm² | Membrane thickness, conductivity |

| Charge Transfer Resistance | Rct | Kinetics of electrode reaction | 100-1000 Ω·cm² | Electrode material, temperature |

| Double Layer Capacitance | Cdl | Interface capacitance | 10-100 μF/cm² | Electrode surface area |

| Warburg Impedance | ZW | Li+ diffusion in electrodes | Variable | Diffusion coefficient, morphology |

| Constant Phase Element | Q, α | Non-ideal capacitance | α: 0.8-1.0 | Surface heterogeneity |

Experimental Protocol: EIS for Solid-State Polymer Electrolytes

Materials and Equipment

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat with EIS capability (e.g., Zahner IM6)

- Symmetric cells (SSB configuration)

- Temperature-controlled test station

- Environmental chamber for humidity control

- Electrolyte samples (polymer membranes or composite films)

Procedure

Cell Assembly:

- Prepare symmetric cells with polymer electrolyte sandwiched between electrodes

- Apply controlled pressure to ensure intimate contact (typically 1-10 MPa)

- Connect to test fixtures in environmental chamber

Experimental Conditions:

- Set temperature according to application requirements (typically 25°C, 40°C, 60°C)

- Maintain inert atmosphere for moisture-sensitive systems

- Allow thermal equilibration for 30 minutes before measurement

EIS Measurement Parameters:

- Frequency range: 1 MHz to 10 mHz

- AC amplitude: 10-20 mV (ensure linear response)

- DC bias: 0 V (or at open circuit potential)

- Points per decade: 10-15 for optimal resolution

Data Collection:

- Perform duplicate measurements to ensure reproducibility

- Include Kramers-Kronig validation to verify data quality

- Record temperature and environmental conditions for each measurement

Equivalent Circuit Fitting:

- Select appropriate physical model (e.g., transmission line model for porous electrodes)

- Perform non-linear least squares fitting

- Validate model with statistical parameters (χ², error distribution)

Equivalent Circuit Modeling Workflow

Applications in High-Throughput Polymer Screening

EIS enables rapid characterization of ion transport properties in novel polymer electrolytes, facilitating the screening of composite materials for solid-state batteries. The technique provides critical parameters including ionic conductivity, interface stability, and charge transfer kinetics essential for predicting battery performance. Implementation of multi-channel EIS systems allows parallel measurement of multiple formulations, dramatically increasing throughput for polymer discovery programs focused on energy storage applications [38] [39].

Application Note: Cell-Based Assays for High-Content Screening in Drug Discovery

Cell-based assays provide biologically relevant systems for compound screening in drug discovery, offering significant advantages over target-based biochemical approaches. The global cell-based assays market is projected to grow from USD 17.84 billion in 2025 to USD 27.55 billion by 2030, at a CAGR of 9.1%, reflecting increasing adoption in pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries [40] [41]. These assays bridge the gap between in vitro screening and in vivo efficacy, delivering more physiologically relevant data for decision-making in polymer discovery and therapeutic development.

Market Landscape and Technology Trends

Table 3: Cell-Based Assay Platforms and Applications

| Platform Type | Key Features | Throughput Capability | Primary Applications | Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Monolayer Culture | Standardized, cost-effective | 96 to 1536-well formats | Primary screening, toxicity | Fluorescence, luminescence |

| 3D Culture Systems | Enhanced physiological relevance | 96 to 384-well formats | Disease modeling, efficacy | Imaging, metabolic assays |

| Microfluidic Platforms | Precise microenvironment control | Medium throughput | Organ-on-a-chip, specialized assays | Electrochemical, optical |

| Flow Cytometry | Multiplexed single-cell analysis | High throughput (up to 10,000 cells/sec) | Immunophenotyping, signaling | Scattering, fluorescence |

| Thread-based Sensors | Minimally invasive, multiplexed | 24 to 96-well formats | Metabolite monitoring | Potentiometric, amperometric |

Experimental Protocol: High-Throughput Cell-Based Screening Assay

Materials and Equipment

- Cell lines (primary or engineered)

- 384-well microtiter plates

- Automated liquid handling system

- Multimodal plate reader (e.g., confocal imaging, fluorescence, luminescence)

- Compound libraries (small molecules, polymers, biologics)

- Cell culture reagents and assay kits

Procedure

Cell Culture and Plating:

- Maintain cells in appropriate culture conditions

- Harvest at 70-80% confluence using standard dissociation methods

- Prepare cell suspension at optimized density (typically 5,000-50,000 cells/mL)

- Dispense into 384-well plates using automated liquid handler (50-100 μL/well)

- Incubate for 24 hours to allow cell attachment (37°C, 5% CO2)

Compound Treatment:

- Prepare compound dilutions in DMSO or aqueous buffer

- Transfer compounds to assay plates using pin tool or acoustic dispensing

- Include appropriate controls (vehicle, positive, negative)

- Incubate for desired treatment period (typically 24-72 hours)

Endpoint Detection:

- Viability Assessment: Add MTT, PrestoBlue, or CellTiter-Glo reagents

- Apoptosis Detection: Caspase activation assays, Annexin V staining

- Morphological Analysis: High-content imaging with nuclear/cytoskeletal stains

- Metabolic Monitoring: pH, O2 consumption using thread-based sensors [42]

Signal Measurement:

- Read plates using appropriate detection modality

- Configure instrument settings for optimal dynamic range

- Export raw data for analysis

Data Analysis:

- Normalize data to vehicle controls

- Calculate Z' factor for quality control (acceptable >0.5)

- Determine IC50, EC50 values using non-linear regression

- Apply statistical analysis for significance testing

High-Throughput Screening Workflow

Advanced Applications in Polymer Discovery

Cell-based screening platforms have evolved to address complex biological questions in polymer discovery research. The integration of 3D culture models and organ-on-a-chip technologies provides more physiologically relevant environments for evaluating polymer-biomolecule interactions. Multiplexed sensing systems with thread-based electrochemical sensors enable real-time monitoring of cellular responses, including pH, dissolved oxygen, and metabolic rates [42]. These advancements facilitate the development of polymers with optimized biocompatibility and functionality for biomedical applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Core Screening Techniques

| Category | Specific Items | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Analysis | Disposable microfluidic chips | Sample containment, elimination of cross-contamination | RS-DSC analysis of protein formulations |

| PANI-coated pH sensors | Potentiometric pH monitoring | Cell culture metabolic assessment [42] | |

| Reference materials (indium, water) | Instrument calibration | Daily validation of thermal instruments | |

| Impedance Spectroscopy | Polymer electrolyte membranes | Solid-state ion conduction | SSB characterization [38] [39] |

| Symmetric cell fixtures | Controlled electrochemical measurements | Standardized EIS of materials | |

| Equivalent circuit modeling software | Data analysis and interpretation | Physical parameter extraction | |

| Cell-Based Assays | 384-well microtiter plates | High-density screening format | Compound library profiling |

| Viability/toxicity assay kits | Cellular response quantification | MTT, CellTiter-Glo, PrestoBlue | |

| Thread-based electrochemical sensors | Multiplexed metabolite monitoring | pH, O2 detection in bioreactors [42] | |

| Polymer microarrays | High-throughput biomaterial screening | Cell-biomaterial interaction studies [43] |

The integration of impedance spectroscopy, thermal analysis, and cell-based assays creates a powerful toolkit for high-throughput polymer discovery research. These complementary techniques provide comprehensive characterization of material properties, from molecular-level interactions to biological responses. The continued advancement of these platforms, including miniaturization, multiplexing, and integration of artificial intelligence for data analysis, will further accelerate the discovery and development of novel polymers for biomedical and energy applications.

Fiber-Optic Array Scanning Technology (FAST) represents a paradigm shift in ultra-high-throughput screening, originally developed to identify rare circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in blood samples with exceptional sensitivity and specificity [44] [45]. This laser-based scanning system achieves remarkable throughput by combining high-speed optics with sophisticated fluorescence detection capabilities, enabling the screening of millions of analytes per minute [10]. The technology's core innovation lies in its ability to rapidly scan large surfaces containing biological or chemical samples while maintaining the sensitivity required to detect rare events within complex mixtures.

The adaptability of FAST has been demonstrated across multiple scientific domains, from biomedical diagnostics to drug discovery. Initially configured for rare cell detection in oncology, the platform scans cells pre-incubated with fluorescently labeled markers plated as monolayers on glass slides [10]. The system excites fluorescence with a 488 nm laser and collects emitted light through a fiber-optic bundle, analyzing it through bandpass filters and photomultiplier tubes [10]. This well-free assay format can identify single rare cells among 25 million white blood cells in approximately one minute with approximately 8 μm resolution [45] [10]. More recently, researchers have successfully adapted FAST for screening massive combinatorial libraries of synthetic non-natural polymers, demonstrating its versatility beyond cellular applications [10].

FAST Technology: Operational Principles and System Components

Core Technological Framework

The FAST platform operates on fundamental principles of fluorescence cytometry enhanced with specialized fiber-optic array components. The system detects fluorescently labeled targets within a sample by scanning with a laser excitation source and capturing emitted signals through thousands of individual optical fibers arranged in a coherent bundle [10]. This configuration enables parallel processing of signals from multiple points simultaneously, dramatically increasing throughput compared to conventional single-point scanning systems.

A critical innovation in FAST is its dual-wavelength detection capability, which measures emissions at two different wavelengths (typically 520 nm for green and 580 nm for red/orange) to distinguish specific fluorescence from background autofluorescence [10]. This wavelength comparison technique is particularly valuable when screening samples with inherent autofluorescence, such as TentaGel beads used in combinatorial chemistry, as it significantly improves signal-to-noise ratios and detection specificity [10].

System Architecture and Components

The complete FAST system integrates several specialized components that work in concert to achieve ultra-high-throughput screening:

- Laser Excitation Module: Utilizes a 488 nm laser to excite fluorescent labels within the sample [10].

- Fiber-Optic Array: A coherent bundle of thousands of optical fibers that collect emitted fluorescence from multiple points on the sample simultaneously [10].

- Emission Filter System: Bandpass filters that separate fluorescence signals at specific wavelengths (520 nm and 580 nm) [10].

- Photomultiplier Tubes (PMTs): Highly sensitive detectors that convert optical signals to electrical signals for analysis [10].

- Coordinate Mapping System: Tracks Cartesian coordinates of fluorescently labeled objects on a pixel map along with intensity measurements [10].

- Automated Digital Microscopy (ADM): Secondary validation system that captures high-resolution images of detected targets for confirmation and further characterization [44] [45].

Detection Sensitivity and Specificity

The FAST platform achieves exceptional detection sensitivity, with demonstrated capability to identify single rare cells spiked into blood samples at frequencies as low as 1 cell per 10^7 leukocytes [46]. In optimized bead-based screening applications, the system demonstrates detection sensitivity exceeding 99.99% when identifying biotin-labeled beads spiked into a pool of underivatized beads [10]. This high sensitivity is maintained even at remarkable scanning speeds of up to 5 million compounds per minute (approximately 83,000 Hz) in polymer screening applications [10].

FAST in Polymer Discovery Research: Applications and Workflows

Screening of Combinatorial Polymer Libraries

The application of FAST to polymer discovery represents a significant advancement in combinatorial screening methodologies. Traditional "one-bead-one-compound" (OBOC) libraries have been limited to thousands or hundreds of thousands of compounds due to screening bottlenecks [10]. FAST overcomes this limitation by enabling the screening of libraries containing up to billions of synthetic compounds [10]. This massive throughput expansion allows researchers to explore unprecedented chemical diversity in search of novel polymers with desired properties.

In practice, FAST screens synthetic non-natural polymers (NNPs) synthesized on solid support beads. These sequence-defined foldamers are screened against biological targets of interest, including proteins such as K-Ras, asialoglycoprotein receptor 1 (ASGPR), IL-6, IL-6 receptor (IL-6R), and TNFα [10]. The platform has successfully identified hits with low nanomolar binding affinities, including competitive inhibitors of protein-protein interactions and functionally active uptake ligands facilitating intracellular delivery [10].

Integration with Downstream Analysis

A key advantage of the FAST platform in polymer discovery is its compatibility with downstream analytical techniques. After ultra-high-throughput screening identifies hit beads, the system's coordinate mapping capability enables precise location and retrieval of individual beads for sequencing [44] [10]. This integration is crucial for identifying the chemical structures of active compounds.

For novel non-natural polymers where traditional sequencing methods like Edman degradation or LC-MS/MS are ineffective, researchers have developed specialized sequencing approaches with femtomole sensitivity [10]. These methods utilize chemical fragmentation and high-resolution mass spectrometry to determine polymer sequences from minimal material, enabling the identification of hit compounds from libraries synthesized on 10-20 μm diameter beads [10].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete FAST screening workflow for polymer discovery applications, from library preparation through hit identification and sequencing:

Research Reagent Solutions for FAST-Based Screening

Successful implementation of FAST screening protocols requires specific research reagents and materials optimized for the platform's requirements. The following table details essential components for FAST-based polymer discovery campaigns:

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for FAST-Based Polymer Discovery Screening

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Solid Support Beads | TentaGel beads (10-20 μm diameter) | Solid phase for combinatorial synthesis of polymer libraries; smaller sizes enable larger libraries with reduced material costs [10] |

| Fluorescent Labels | Alexa Fluor 555 or CF555 | Fluorophore conjugation to target proteins; selected for reduced interference with bead autofluorescence compared to FITC [10] |

| Binding Buffers | Physiological pH with appropriate ionic strength | Maintain target protein structure and function during screening incubation steps [10] |

| Plating Materials | 108 × 76 mm glass slides | Surface for creating monolayer bead distribution optimal for FAST scanning [10] |

| Wash Solutions | Mild detergents in buffer (e.g., PBS with Tween-20) | Remove non-specifically bound target proteins while preserving specific interactions [10] |

| Sequencing Reagents | Chemical fragmentation cocktails | Cleave polymers from single beads at specific sites for mass spectrometry analysis [10] |

Experimental Protocols for FAST-Based Screening

Protocol 1: Bead Library Preparation and Plating

Objective: Prepare OBOC polymer library beads for FAST screening at optimal density and distribution.

Materials:

- Synthetic non-natural polymer library synthesized on TentaGel beads (10-20 μm diameter)

- Glass slides (108 × 76 mm)

- Ethanol (70% v/v)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4

Procedure:

- Suspend bead library in PBS to achieve concentration of 5 million beads/mL for 10 μm beads or 2.5 million beads/mL for 20 μm beads [10].

- Apply 1 mL bead suspension to glass slide and spread evenly using a bent glass rod.

- Allow beads to settle and adhere to slide for 15 minutes at room temperature.

- Carefully rinse slide with PBS to remove non-adherent beads and create uniform monolayer.

- Verify bead distribution and density using brightfield microscopy.

- Proceed immediately to target incubation or store prepared slides in humidified chamber at 4°C for up to 24 hours.

Technical Notes:

- Optimal bead density is critical to prevent aggregation and ensure accurate detection [10].

- For 10 μm diameter beads, plate at density of 5 million beads per slide [10].

- For 20 μm diameter beads, plate at density of 2.5 million beads per slide [10].

Protocol 2: Target Incubation and FAST Scanning

Objective: Screen bead library against fluorescently labeled target proteins and identify hits using FAST system.

Materials:

- Prepared bead library slides

- Target protein (K-Ras, ASGPR, IL-6, IL-6R, or TNFα) labeled with Alexa Fluor 555

- Blocking buffer (PBS with 1% BSA)

- Wash buffer (PBS with 0.05% Tween-20)

- FAST scanning system

Procedure:

- Block prepared bead slides with blocking buffer for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Incubate with fluorescently labeled target protein (typical concentration 10-100 nM) in blocking buffer for 60 minutes at room temperature with gentle agitation [10].

- Wash slides three times with wash buffer (5 minutes per wash) to remove unbound target.

- Perform final rinse with PBS to reduce background fluorescence.

- Load slide into FAST scanner and initiate scanning protocol.

- Set laser excitation to 488 nm and configure emission detection at 520 nm and 580 nm [10].

- Execute scan at rate of approximately 5 million beads per minute [10].

- Record Cartesian coordinates and fluorescence intensity values for all detected hits.

Technical Notes:

- Dual-wavelength detection discriminates specific binding from autofluorescence [10].

- Typical scan identifies fluorescently labeled beads with >99.99% sensitivity [10].

- Hit threshold should be established based on negative control beads.

Protocol 3: Hit Recovery and Sequencing

Objective: Recover hit beads from FAST screening for polymer sequence determination.

Materials:

- FAST scan results with hit coordinates

- Automated bead picking system