Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) Explained: A Foundational Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the glass transition temperature (Tg), a critical thermal property of amorphous materials, with a specific focus on applications in pharmaceutical and drug development...

Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) Explained: A Foundational Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the glass transition temperature (Tg), a critical thermal property of amorphous materials, with a specific focus on applications in pharmaceutical and drug development research. It covers the foundational science behind Tg, including its definition and the distinction between amorphous and semi-crystalline polymers. The content details the methodologies for accurate Tg measurement, such as DSC and DMA, and addresses common challenges like burst release in PLGA-based drug delivery systems. Furthermore, it offers guidance on troubleshooting measurement discrepancies and validates findings through comparative analysis of material data, equipping scientists with the knowledge to optimize material selection and processing for advanced biomedical applications.

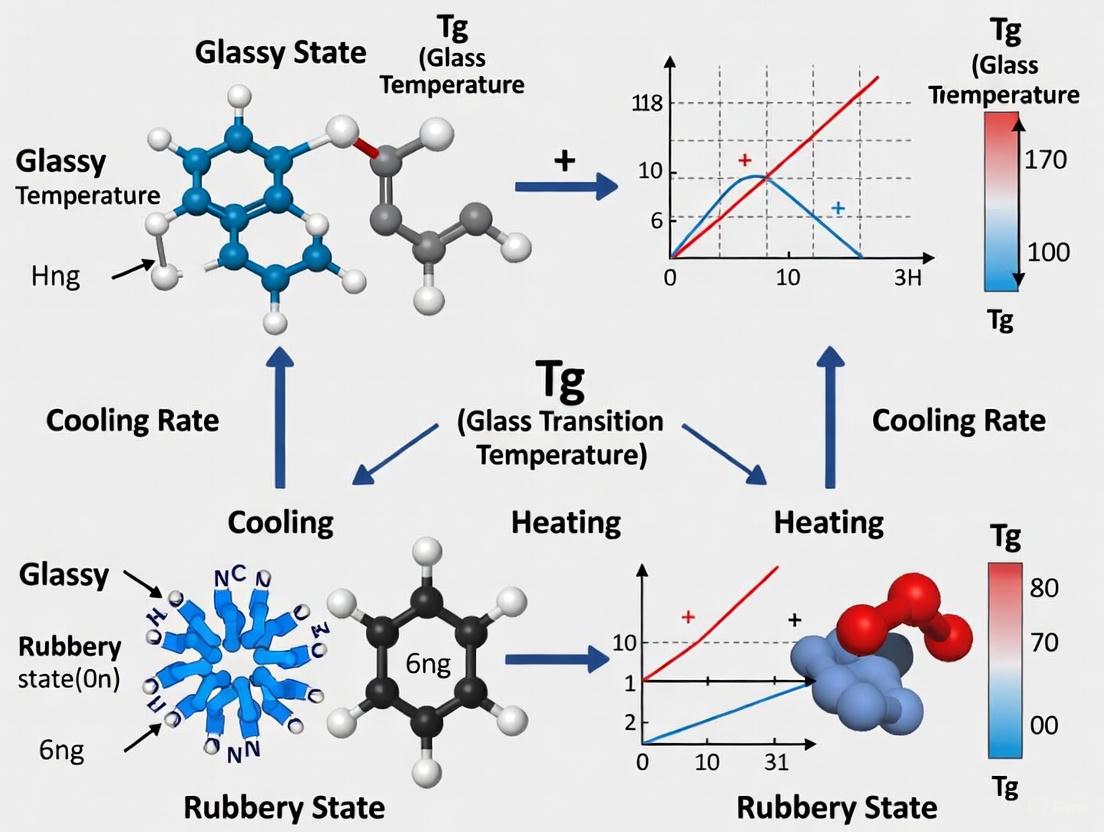

What is Glass Transition Temperature? Core Concepts and Polymer Fundamentals

The glass–liquid transition, or glass transition, is the gradual and reversible transition in amorphous materials (or in amorphous regions within semicrystalline materials) from a hard and relatively brittle "glassy" state into a viscous or rubbery state as the temperature is increased [1]. An amorphous solid that exhibits a glass transition is called a glass. The reverse transition, achieved by supercooling a viscous liquid into the glass state, is called vitrification [1]. The glass transition temperature (Tg) characterizes the range of temperatures over which this transition occurs, and it is always lower than the melting temperature (Tm) of the crystalline state of the material, if one exists [1].

Unlike melting, which is a first-order phase transition involving discontinuities in thermodynamic properties, the glass transition is not considered a true thermodynamic phase transition [1] [2]. Rather, it is a phenomenon extending over a temperature range defined by several conventions. Upon cooling or heating through this glass-transition range, the material exhibits a smooth step in the thermal-expansion coefficient and in the specific heat [1]. The question of whether some phase transition underlies the glass transition remains a matter of ongoing research [1].

Fundamental Principles and Molecular Mechanisms

The Molecular Nature of the Transition

At the molecular level, the glass transition can be understood through the concept of chain mobility and free volume [3]. Polymers are long-chain molecules that, given sufficient thermal energy, undergo bond rotations and conformational changes. At low temperatures, the amorphous regions of a polymer are in the glassy state where molecules are effectively frozen in place—they may vibrate slightly but lack segmental motion [2].

As the polymer is heated, its volume expands, increasing the free volume—the space not occupied by polymer chains. This additional space allows chain segments to wiggle and slide past one another [3]. At the glass transition temperature, the free volume becomes sufficient to enable coordinated molecular motion, and the material transitions to its rubbery state [3]. This increased molecular mobility below Tg, the material is hard, rigid, and brittle because molecular motion is severely restricted [4]. Above Tg, the increased mobility of polymer chain segments allows the material to become soft and flexible [2] [4].

Key Differences from Melting

It is crucial to distinguish the glass transition from melting, as these are fundamentally different processes:

Table 1: Comparison between Glass Transition and Melting

| Characteristic | Glass Transition | Melting |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Nature | Second-order transition range [2] | First-order phase transition [2] |

| Molecular Process | Onset of segmental motion in amorphous regions [4] | Transition from ordered crystal to disordered melt [4] |

| Thermodynamics | No latent heat; change in heat capacity [2] | Absorbs latent heat of fusion [3] |

| Volume Change | Continuous change in slope [2] | Abrupt discontinuity [2] |

| Structural Order | Property of disordered amorphous regions [2] | Property of ordered crystalline regions [4] |

Experimental Characterization of Tg

Measurement Techniques

The glass transition temperature is operationally defined, and different measurement techniques yield slightly different values [1]. The most common methods include:

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

DSC monitors the difference in heat flow between a sample and reference as temperature changes. The glass transition appears as a step change in the baseline of the heat flow curve due to the change in heat capacity (Δcp) [4] [5]. Standard test methods include ASTM E1356 and ISO 11357-2 [4] [5]. DSC is suitable for solids, powders, and liquids [5].

Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

DMA applies oscillatory stress to measure stiffness (storage modulus, E') and energy dissipation (loss modulus, E'') as functions of temperature. Tg is identified from the peak in E'' or tan δ (E''/E') [6] [4] [5]. DMA is extremely sensitive to glass transitions and can detect transitions not easily visible by DSC [6]. Standard methods include ASTM E1640 [4].

Thermomechanical Analysis (TMA)

TMA measures dimensional changes versus temperature. The glass transition is observed as an inflection point in the thermal expansion curve due to the change in the coefficient of thermal expansion [1] [5]. This method is described in standards such as ASTM E1545 [5].

The following diagram illustrates the generalized experimental workflow for characterizing the glass transition:

Experimental Protocol for DMA Measurement

For researchers requiring detailed methodologies, the following protocol for determining Tg via Dynamic Mechanical Analysis has been documented in recent studies:

- Sample Preparation: Process the material (e.g., rice flour) by milling and sieving to obtain a fraction below 177 μm [6]. Determine the moisture content gravimetrically according to established standards like AACCI Method 44-15.02 [6].

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate the DMA (e.g., PerkinElmer 8000) according to manufacturer specifications [6].

- Temperature Program: Conduct temperature sweeps by heating samples at a controlled rate (e.g., 2°C/min) from below to above the anticipated Tg range [6].

- Frequency Setting: Maintain a constant frequency during the sweep (e.g., 1 Hz) [6].

- Data Acquisition: Monitor storage modulus (E'), loss modulus (E''), and tan δ as functions of temperature [6].

- Data Analysis: Determine Tg using multiple criteria [6]:

- Tg-onset: Inflection point temperature of the E' curve.

- Tg-midpoint: Peak temperature of the E'' curve.

- Tg-endset: Peak temperature of the tan δ curve.

Glass Transition in Material Systems

Tg Values for Engineering Polymers

The glass transition temperature varies significantly with chemical structure. The following table provides characteristic Tg values for common polymers:

Table 2: Glass Transition Temperatures of Selected Polymers

| Polymer | Tg (°C) | State at Room Temperature | Commercial/Technical Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tire Rubber | -70 [1] | Rubbery (Above Tg) | - |

| Polypropylene (atactic) | -20 [1] [2] | Transitional | - |

| Poly(vinyl acetate) (PVAc) | 28-30 [1] [2] | Transitional | - |

| Poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) | 80-81 [1] [2] | Glassy (Below Tg) | - |

| Poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) | 85 [1] [2] | Glassy (Below Tg) | - |

| Polyethylene terephthalate) (PET) | 69-70 [1] [2] | Glassy (Below Tg) | - |

| Polystyrene | 100 [1] [2] | Glassy (Below Tg) | - |

| Poly(methyl methacrylate) | ~100-105 [1] [2] | Glassy (Below Tg) | PMMA |

| Polypropylene (isotactic) | 100 [2] | Glassy (Below Tg) | - |

Factors Influencing Tg

The glass transition temperature is not an intrinsic material constant but depends on multiple factors:

- Molecular Weight: In straight-chain polymers, increasing molecular weight decreases chain end concentration, reducing free volume and increasing Tg [4].

- Chemical Cross-linking: Increased cross-linking restricts polymer chain mobility, decreasing free volume and raising Tg [4].

- Plasticizers: Addition of plasticizers increases free volume between polymer chains, allowing them to slide past each other at lower temperatures and thus decreasing Tg [4].

- Moisture Content: Water acts as a plasticizer. Increased moisture content forms hydrogen bonds between chains, increasing free volume and decreasing Tg [6] [5].

- Molecular Structure: Bulky side groups restrict chain mobility, increasing Tg, while flexible backbone linkages lower Tg [4].

- Pressure: Increased pressure reduces free volume, resulting in a higher Tg [4].

The relationship between these factors and the resulting material properties is summarized below:

Advanced Applications and Current Research

Pharmaceutical Development

In pharmaceutical sciences, the glass transition is critical for enhancing drug bioavailability. Amorphous drugs often exhibit higher water solubility than their crystalline counterparts, but they are physically and chemically less stable [7]. Understanding Tg helps prevent recrystallization from supercooled and glassy states, ensuring drug stability and efficacy [7]. Recent research focuses on drug-biopolymer dispersions to improve physical stability, investigating molecular mechanisms in systems like the anxiolytic drug nordazepam mixed with biodegradable biopolymers [7].

Cryopreservation and Thermal Stress Management

Recent groundbreaking research has explored the role of Tg in cryopreservation by vitrification—stabilizing biological matter in a glassy state at low temperatures [8]. This approach could transform organ transplantation and wildlife conservation. A key challenge is avoiding thermal stress cracking during temperature cycling [8].

A 2025 study in Scientific Reports provided experimental and computational evidence that thermal stresses are strongly dependent on the Tg of the vitrification solution [8]. Using a custom cryomacroscope platform and deep learning-based image segmentation, researchers demonstrated that solutions with higher Tg (e.g., 63 wt% Sucrose, Tg = -82°C) experience lower stress and reduced cracking compared to those with lower Tg (e.g., 49 wt% DMSO, Tg = -131°C) when thermally cycled under identical conditions [8]. This relationship is attributed to an inverse correlation between Tg and thermal expansion coefficient—solutions with higher Tg expand and contract less during temperature changes, generating lower thermal stress [8]. This insight suggests that conventional vitrification solutions may be ill-suited for avoiding thermal stress, opening new avenues for designing next-generation cryopreservation protocols.

Food Science and Grains

In food science, Tg explains phenomena like fissure formation in rice during drying. Research on IRGA 424 rice has shown that drying and tempering above Tg preserves quality by preventing regions with different mechanical properties that cause fissuring [6]. Tg of rice flour decreases from approximately 104.7°C to 42.1°C (tan δ peak) as moisture content increases from 9.3% to 22.3% [6], demonstrating water's plasticizing effect.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Glass Transition Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Cryoprotectant agent | Aqueous vitrification solutions for cryopreservation [8] |

| Glycerol | Cryoprotectant and plasticizer | Vitrification solutions; modulates Tg and thermal expansion [8] |

| Xylitol | Polyol plasticizer | Binary aqueous solutions for studying Tg-stress relationship [8] |

| Sucrose | Disaccharide modifying Tg | High-Tg vitrification solutions to reduce thermal stress cracking [8] |

| Sorbitol | Plasticizer and sugar substitute | Model system for studying water plasticization effects on Tg [5] |

| Poly-L-lactide (PLLA) | Biodegradable biopolymer | Drug-polymer dispersions for pharmaceutical stability studies [7] |

| Schiff Bases | Model glass-formers | Investigating relaxation behaviors and tunable Tg values [7] |

The glass transition represents a fundamental property of amorphous materials with far-reaching implications across scientific disciplines and industrial applications. From the design of polymers with tailored mechanical properties to the stabilization of pharmaceutical formulations and the advancement of cryopreservation technologies, a deep understanding of Tg and its controlling factors is indispensable. Current research continues to unravel the complexities of this transition, exploring the interplay between molecular structure, thermodynamic properties, and material performance. The ongoing investigation into relationships between Tg and other material properties, such as thermal expansion, promises to enable new engineering solutions in fields ranging from biomedical engineering to materials science.

The physical and mechanical properties of polymers are profoundly influenced by their internal microstructure, specifically the arrangement of their long molecular chains. This arrangement falls primarily into two categories: amorphous and semi-crystalline structures. Amorphous polymers possess a random, disordered molecular structure, often compared to a bowl of cooked spaghetti, where the chains are tangled without long-range order [9] [10]. In contrast, semi-crystalline polymers feature a mixed morphology consisting of highly ordered, packed crystalline regions (lamellae) embedded within a disordered amorphous matrix [11] [12]. The degree of crystallinity, which can range from 10% to 80%, is a critical factor determining the final properties of the material [11]. For semi-crystalline polymers, this crystalline fraction typically must exceed approximately 25% to exhibit characteristic semi-crystalline behavior [11]. Understanding this fundamental structural distinction is essential for researchers and scientists to predict material performance, select appropriate polymers for specific applications, and design novel materials with tailored properties.

Structural Architecture and Molecular Order

The foundational difference between amorphous and semi-crystalline polymers lies in the spatial organization of their polymer chains, which directly dictates their thermal transitions and ultimate material characteristics.

Amorphous Polymers: In amorphous polymers, the molecular chains are arranged in a random, haphazard fashion, resulting in a structure that lacks any long-range order [9] [10]. This disorganization means the chains are physically entangled but do not pack into a consistent, repeating pattern. When heated, these materials do not possess a sharp melting point. Instead, they undergo a gradual softening as the temperature increases, eventually becoming a viscous liquid [9] [11]. This gradual softening occurs because the polymer transitions through a leathery or rubbery state before achieving full flow.

Semi-Crystalline Polymers: Semi-crystalline polymers exhibit a more complex, two-phase structure. Within these materials, the polymer chains fold and organize into tight, ordered packs known as lamellae, which form the crystalline regions [11] [12]. These lamellae act as robust physical cross-links, reinforcing the material. However, it is thermodynamically improbable for all chain segments to incorporate into these perfect crystals. Therefore, the lamellae are dispersed within and connected by regions of disordered, amorphous chains [12]. This dual nature gives semi-crystalline polymers a distinct melting point (Tm), corresponding to the dissociation of the crystalline lamellae, while the amorphous parts still undergo a glass transition (Tg) [11].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental structural differences between these two polymer classes.

The Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) in Context

The glass transition temperature (Tg) is a critical thermal property, defined as the temperature at which the amorphous regions of a polymer transition from a hard, glassy state to a softer, rubbery state upon heating [13] [4] [1]. This is not a phase transition with a latent heat, like melting, but rather a second-order transition marked by a change in the rate of physical properties, such as a step change in the heat capacity or coefficient of thermal expansion [1] [14].

Behavior Below and Above Tg: Below its Tg, an amorphous polymer is in a glassy state; the molecular chains are frozen in place, lacking the thermal energy to slide past one another. This results in a material that is hard, rigid, and often brittle [4] [10]. Above the Tg, the amorphous regions enter a rubbery state. Sufficient thermal energy allows for segmental chain motion, granting the material flexibility, leather-like properties, and the ability to undergo large deformations [13] [4].

Role in Semi-Crystalline Polymers: In semi-crystalline polymers, the Tg specifically pertains to the behavior of the amorphous regions between the crystalline lamellae [13] [12]. Below the Tg, these amorphous regions are glassy and brittle. Above the Tg, they become rubbery. However, the material often retains significant mechanical integrity because the crystalline lamellae, which remain solid until the melting point (Tm), act as a reinforcing scaffold [13] [11]. This allows many semi-crystalline polymers like polypropylene (PP) to be used at service temperatures between their Tg and Tm [13].

The following table provides the Tg values for common polymers, illustrating the wide range across different material types.

Table 1: Glass Transition Temperatures of Common Polymers

| Polymer | Abbreviation | Type | Tg (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Purpose Polystyrene | GPPS | Amorphous | 100 [13] |

| Polycarbonate | PC | Amorphous | 145 [13] |

| Polysulfone | PSU | Amorphous | 190 [13] |

| Polyetherimide | PEI | Amorphous | 210 [13] |

| Polypropylene (atactic) | PP | Semi-Crystalline | -20 [13] |

| High-Density Polyethylene | HDPE | Semi-Crystalline | -120 [13] |

| Liquid Silicone Rubber | LSR | Thermoset | -125 [13] |

| Polyetheretherketone | PEEK | Semi-Crystalline | 140 [13] |

Comparative Analysis of Key Properties

The structural differences between amorphous and semi-crystalline polymers manifest in distinct mechanical, thermal, optical, and chemical properties. The following table summarizes these key differences, providing a clear overview for material selection.

Table 2: Property Comparison of Amorphous and Semi-Crystalline Polymers

| Property | Amorphous Polymers | Semi-Crystalline Polymers |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Structure | Random, disordered chains [9] [10] | Ordered crystalline regions + amorphous regions [11] [12] |

| Thermal Behavior | Gradual softening over a temperature range; no true melting point [9] [11] | Sharp melting point (Tm); remains structured above Tg until Tm [13] [11] |

| Optical Clarity | Typically transparent [13] [9] | Typically opaque or translucent [13] [11] |

| Mechanical Properties | High impact resistance; good stiffness at low temps [13] [9] | High stiffness, strength, and toughness; poor impact resistance [9] [15] |

| Chemical Resistance | Generally poor [9] [11] | Excellent, due to tight molecular packing [13] [15] |

| Wear & Fatigue | Poor wear and fatigue resistance [11] | Excellent wear and fatigue resistance [11] |

| Shrinkage & Dimensional Stability | Low, isotropic shrinkage; good stability [13] [15] | High, anisotropic shrinkage; can warp [9] [15] |

| Bonding | Bonds well with adhesives [11] | Difficult to bond with adhesives [11] |

Detailed Discussion of Properties

Mechanical Properties: Semi-crystalline polymers generally exhibit superior strength, stiffness, and toughness compared to amorphous polymers because the densely packed crystalline lamellae effectively resist mechanical deformation [9] [15]. This makes them suitable for structural and load-bearing components. However, amorphous polymers typically possess higher impact resistance at room temperature, as their tangled chains can absorb more energy before fracturing [9].

Thermal Properties: The defining thermal difference is the presence of a sharp melting point (Tm) in semi-crystalline polymers, which amorphous materials lack [11]. Furthermore, semi-crystalline polymers can often be used at temperatures above their Tg, as the crystalline regions maintain structural integrity. Amorphous polymers, however, will soften and lose their shape once the service temperature significantly exceeds their Tg [13].

Chemical and Environmental Resistance: The tight molecular packing in the crystalline regions of semi-crystalline polymers creates a tortuous path, making it difficult for chemicals and solvents to penetrate. This results in excellent chemical resistance [13] [15]. Amorphous polymers, with their more open and disordered structure, are generally more susceptible to chemical attack and solvent-induced swelling [9].

Optical Properties: The random structure of amorphous polymers does not scatter visible light significantly, which is why materials like polycarbonate (PC) and polystyrene (PS) are often transparent [13] [9]. In contrast, the crystalline regions in semi-crystalline polymers have a different refractive index than the amorphous matrix. This interface scatters light, rendering these materials typically opaque [11].

Experimental Characterization and Protocols

Accurately characterizing polymer morphology and thermal transitions is fundamental to research and development. The following section details key experimental methodologies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment

Table 3: Key Reagents and Equipment for Polymer Thermal Analysis

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Measures heat flow into/out of a sample vs. temperature. Primarily used to determine Tg (as a step change in heat capacity) and Tm (as an endothermic peak) [4] [10]. |

| Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer (DMA) | Applies an oscillatory stress to a sample and measures the resulting strain over a temperature range. Highly sensitive for detecting Tg via dramatic changes in storage (E') and loss (E") moduli [4] [16]. |

| Tensile Testing Machine | Pulls a standardized polymer specimen at a constant rate to measure mechanical properties like tensile strength, elongation at break, and elastic modulus [10]. |

| Inert Gas (e.g., N₂) | Purging gas used in thermal analysis equipment (DSC, DMA) to prevent polymer oxidation or degradation at high temperatures [4]. |

| Standard Reference Materials | Calibration standards (e.g., indium, zinc) with known melting points and enthalpies, used to calibrate DSC instruments for accurate temperature and enthalpy measurement [4]. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Determining Tg by Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Principle: DSC monitors the difference in heat flow between a polymer sample and an inert reference as they are heated or cooled at a controlled rate. The glass transition is observed as a step change in the heat flow curve due to the change in heat capacity of the amorphous regions as they become mobile [4] [10].

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Place a small, precisely weighed sample (5-10 mg) in a hermetic aluminum DSC pan. An empty pan of the same type is used as a reference.

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate the DSC cell for temperature and enthalpy using high-purity standards like indium.

- Thermal Cycle:

- Equilibration: Equilibrate at a starting temperature well below the expected Tg (e.g., 50°C below).

- Heating Scan: Heat the sample and reference at a standardized rate (commonly 10°C/min) through the transition region to a temperature above the expected Tg.

- Data Analysis: Identify the Tg from the resulting thermogram. It is conventionally reported as the midpoint of the step transition in the heat flow curve, as defined by standards like ASTM E1356 [4].

Determining Tg by Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

Principle: DMA applies a small oscillatory deformation to a sample and measures the resulting stress, allowing the calculation of the storage modulus (E', elastic response), loss modulus (E", viscous response), and tan δ (E"/E', damping). The Tg is marked by a rapid drop in E' and peaks in E" and tan δ, indicating the onset of large-scale molecular motion [16].

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a polymer specimen compatible with the DMA clamping system (e.g., a rectangular bar for dual cantilever bending).

- Experimental Parameters:

- Deformation Mode: Select an appropriate mode (e.g., tension, bending).

- Frequency: Set a fixed oscillation frequency (e.g., 1 Hz).

- Temperature Ramp: Program a constant heating rate (e.g., 2-5°C/min) over a suitable temperature range.

- Data Collection: The instrument automatically records E', E", and tan δ as a function of temperature.

- Data Analysis: The Tg can be defined in multiple ways from DMA data, offering sensitivity to different aspects of the transition:

- Onset of E' Drop: Indicates the beginning of mechanical softening.

- Peak of E" Curve: Correlates with the energy dissipation maximum.

- Peak of Tan δ Curve: Represents the point of greatest damping [16].

The experimental workflow for thermal characterization is outlined below.

Factors Influencing Polymer Morphology and Tg

The tendency of a polymer to form amorphous or semi-crystalline structures, as well as the specific value of its Tg, is governed by its chemical architecture and processing conditions.

Molecular Structure:

- Chain Flexibility: Flexible polymer backbones (e.g., with C-O or Si-O bonds) have low energy barriers for bond rotation, leading to lower Tg values. Rigid backbones (e.g., with aromatic rings) result in higher Tg values [14].

- Side Groups: The presence of bulky or polar side groups (e.g., Cl, CN, phenyl rings) increases steric hindrance and intermolecular forces, restricting chain mobility and raising the Tg [4] [14].

- Cross-linking: Chemical cross-links tether polymer chains together, drastically reducing their mobility. An increase in cross-link density leads to a significant increase in Tg [4] [14].

Processing and External Factors:

- Cooling Rate: Rapid cooling (quenching) from the melt can prevent polymer chains from having sufficient time to organize into crystals, resulting in an amorphous solid with a higher frozen-in free volume and a lower effective Tg. Slow cooling promotes crystallization [11] [14].

- Plasticizers: The addition of small-molecule plasticizers increases the free volume between polymer chains, spacing them apart and allowing them to slide more easily. This effectively lowers the Tg of the material [4] [14].

- Molecular Weight: In general, increasing the molecular weight of a polymer decreases the concentration of chain ends, which are sites of increased free volume. This reduction in free volume leads to an increase in Tg, which eventually plateaus at very high molecular weights [4].

The glass transition temperature ((Tg)) is a critical physical parameter that marks the reversible transition of an amorphous material from a hard, glassy state into a rubbery or viscous liquid state. Unlike the sharp phase transition of crystalline melting, the glass transition occurs over a temperature range and represents a profound change in molecular mobility without a change in molecular structure. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding (Tg) is essential for designing polymer-based drug delivery systems, stabilizing biological formulations, and developing advanced materials with tailored mechanical properties. This phenomenon finds relevance in diverse applications, from the stabilization of dried Bacillus cereus in low-moisture foods to the performance of polymeric excipients in solid dispersions [17].

This guide explores the molecular origins of (T_g) through two interconnected theoretical frameworks: the kinetic perspective of chain mobility and the thermodynamic concept of free volume. These principles provide the foundation for predicting and manipulating the glass transition to achieve desired material behaviors in scientific and industrial contexts.

The Chain Mobility Perspective: A Kinetic Theory of Tg

The kinetic approach to the glass transition focuses on the molecular motions of polymer chains and the energy required for these motions to occur. Below (T_g), the thermal energy available is insufficient to allow large-scale segmental motion, effectively freezing the polymer chains into a rigid, amorphous solid [14].

Molecular Mechanism of Chain Motion

In a polymer chain, elastic deformation involves altering the distance between chain-ends. This requires changes in polymer conformation, which are achieved at the molecular level by the rotation of individual carbon-carbon (C-C) bonds, shifting between trans and gauche positions. This change in torsion angles is a thermally activated process [14].

- Below (T_g): Thermal energy is inadequate to overcome the energy barrier for bond rotation. Molecular conformations are frozen, and the material behaves as a glass.

- Above (T_g): Sufficient thermal energy exists to permit torsion angle changes. Chains can change shape, and the material exhibits rubbery or liquid behavior.

The apparent value of (T_g) is not absolute but depends on the time-scale of observation due to the kinetic nature of this process [14].

Factors Influencing Chain Mobility and (T_g)

The bulk response of a polymer is governed by chain mobility, which is influenced by several molecular and architectural factors [14].

Table 1: Molecular Factors Affecting Chain Mobility and (T_g)

| Factor | Effect on Chain Mobility | Effect on (T_g) | Molecular Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chain Length | Increases | Increases | Shorter chains have more chain ends per unit volume, creating more free volume and reducing (T_g). |

| Chain Flexibility | Increases | Decreases | A flexible backbone (e.g., siloxanes) has a lower activation energy for conformational changes. |

| Bulky Side Groups | Decreases | Increases | Large, rigid side groups (e.g., benzene rings) sterically hinder bond rotation. |

| Polar Groups | Decreases | Increases | Strong intermolecular forces (e.g., from -Cl, -CN, -OH groups) restrict chain movement. |

| Branching | Variable | Variable | More branches increase chain ends (decreasing (Tg)) but also hinder rotation (increasing (Tg)). The net effect is system-dependent. |

| Cross-linking | Decreases | Increases | Chemical bonds between chains drastically reduce mobility, raising (T_g). |

| Plasticizers | Increases | Decreases | Small molecules between chains act as molecular lubricants, increasing free volume and mobility. |

The Free Volume Theory: A Thermodynamic Perspective

Free volume theory provides a complementary, intuitive framework for understanding the glass transition. It posits that the total volume ((V{Tot})) of a rubber or polymer is composed of the intrinsic volume ((Vi)) occupied by the molecules themselves and the free volume ((V_f))—the empty space or voids between molecules not occupied by molecular chains [18].

The free volume fraction ((f)) is calculated as: [ f = \frac{Vf}{V{Tot}} = \frac{V{Tot} - Vi}{V_{Tot}} ] [18]

Free Volume and Molecular Diffusion

This theory is crucial for explaining diffusion processes. For a molecule (e.g., a gas like hydrogen or a small-molecule drug) to diffuse through a polymer, it requires a critical local free volume to move into. The diffusion coefficient ((D)) is exponentially related to the free volume fraction [18]: [ D = R T Ad \exp\left(-\frac{Bd}{f}\right) ] where (R) is the gas constant, (T) is temperature, and (Ad) and (Bd) are parameters related to the size and shape of the diffusing molecule and the polymer, respectively [18].

The Free Volume Interpretation of (T_g)

As a polymer melt is cooled, its total volume decreases. The occupied volume contracts linearly, but the free volume is squeezed out more rapidly. At (Tg), the free volume reaches a critical minimum, and segmental motions cease as there is insufficient space for chains to rearrange. In the liquid state above (Tg), free volume forms a percolating structure allowing large-scale rearrangements. Below (Tg), free volume exists only in small, isolated pockets, arresting global structural changes [18]. The reduction of free volume with temperature explains the dramatic increase in viscosity and relaxation times observed near (Tg).

Experimental Protocols for Measuring (T_g)

Several experimental techniques probe the changes in molecular mobility or free volume at the glass transition.

Thermal Rheological Analysis (TRA)

This method measures the mechanical response of a material to stress as a function of temperature, which is directly linked to molecular mobility.

- Principle: As a material passes through (T_g), its mechanical modulus (e.g., storage modulus, G') drops significantly due to the onset of molecular flow.

- Protocol: A small, oscillatory stress or strain is applied to a sample while it is heated at a controlled rate. The temperature at which a sharp decrease in storage modulus or a peak in the mechanical loss factor (tan δ) occurs is reported as (T_g) [17].

- Application: This method has been used to measure the (T_g) of dried bacterial cells like Bacillus cereus and Salmonella enterica to understand their survival in low-moisture environments [17].

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

DSC is one of the most common techniques for measuring (T_g).

- Principle: DSC detects the change in heat capacity ((Cp)) that occurs at (Tg) as the material transitions from a glass to a rubber.

- Protocol: A sample and an inert reference are heated at a constant rate (e.g., 10°C/min). At (Tg), the sample's heat capacity increases, requiring more heat to raise its temperature at the same rate as the reference. This appears as a step change in the DSC heat flow curve. The midpoint of the step transition is typically taken as (Tg) [14].

Visualizing the Interplay of Theories and Experiment

The following diagram synthesizes the kinetic, thermodynamic, and experimental concepts of the glass transition into a single workflow, illustrating their interconnected relationships.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Research into glass transition and its applications requires specific materials and analytical tools.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Tg Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Context |

|---|---|---|

| Model Polymers | Fundamental studies on the effects of chain structure, length, and tactility on (T_g). | Amorphous polymers like polystyrene and poly(methyl methacrylate). |

| Plasticizers | To study the reduction of (T_g) and understand free volume and mobility. | Small esters (e.g., phthalates) added to polymers like PVC [14]. |

| Cross-linking Agents | To investigate the increase in (T_g) and the restriction of chain mobility. | Peroxides or multifunctional monomers used in rubber vulcanization [14]. |

| Bacterial Cultures | For studying the role of vitrification in the desiccation tolerance of biologics. | Gram-positive (e.g., Bacillus cereus) and Gram-negative (e.g., Salmonella) strains [17]. |

| Cryoprotectants | To stabilize biological structures during freezing/drying by influencing (T_g). | Trehalose, sucrose, or glycerol used in lyophilization of proteins or bacteria [17]. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | The primary instrument for directly measuring (T_g) via heat capacity change. | Used for characterizing polymers, pharmaceuticals, and biological samples. |

| Thermal Mechanical Analyzer (TMA)/TRA | Measures dimensional changes (TMA) or mechanical properties (TRA) vs. temperature. | Determining softening point and coefficient of thermal expansion [17]. |

The glass transition temperature (Tg) is a critical thermal property that defines the temperature at which an amorphous polymer transitions from a hard, glassy state to a soft, leathery, or rubbery state [13] [19]. This transition is not a phase change like melting but a second-order transition characterized by a change in the heat capacity of the material without a latent heat of transition [20]. Below the Tg, polymer chains are frozen in place, lacking the mobility to slide past one another, resulting in a material that is hard, rigid, and often brittle [4] [20]. Above the Tg, the polymer chains gain sufficient thermal energy to initiate long-range segmental motion, allowing the material to become soft and flexible [13] [20].

The Tg is fundamentally tied to the mobility of the polymer chains. Upon heating, the increased thermal energy overcomes the intermolecular forces holding the chains together, increasing the "free volume" and allowing the chains to begin moving [19] [4]. The Free Volume Theory posits that at the Tg, the polymer achieves a consistent critical value of free volume (approximately 2.5%) that permits this segmental motion [19]. This change in molecular mobility manifests macroscopically as a dramatic shift in material properties, including tensile strength, modulus of elasticity, and impact resistance [13]. Understanding Tg is therefore essential for predicting and designing a polymer's performance in its end-use application.

Tg and Polymer Class Fundamentals

The relationship between a polymer's Tg and its service temperature is a primary factor in classifying its behavior and application.

- Below Tg: The material is in a glassy state. It is hard, rigid, and brittle, similar to glass [4] [20].

- Above Tg: The material is in a rubbery or leathery state. It is soft, flexible, and can undergo large deformations [13] [4].

The following diagram illustrates how the service temperature relative to Tg defines the material class and its resulting mechanical properties.

Amorphous vs. Semi-Crystalline Morphology

A polymer's morphology fundamentally influences its thermal transitions.

- Amorphous Polymers: These possess a random and disordered molecular structure [13] [4]. They do not have a sharp melting point but gradually soften upon heating through the glass transition. These materials are typically transparent and are used either well below their Tg (as rigid plastics) or above it (as rubbers) [13]. Examples include polystyrene (PS) and polycarbonate (PC) [13].

- Semi-Crystalline Polymers: These feature a mix of ordered crystalline regions and disordered amorphous regions [13] [4]. They exhibit both a Tg (associated with the amorphous parts) and a distinct melting temperature (Tm) (associated with the crystalline parts). The crystalline regions provide structure and integrity even above the Tg, allowing these materials to be used in applications beyond their Tg [13]. Polypropylene (PP) is a common example [13].

The table below summarizes the key differences.

Table 1: Characteristics of Amorphous and Semi-Crystalline Polymers

| Feature | Amorphous Polymers | Semi-Crystalline Polymers |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Structure | Random, disordered chains [13] | Ordered crystalline regions + amorphous regions [13] |

| Glass Transition (Tg) | A defining property; only transition for purely amorphous materials [4] | Exhibited by the amorphous portions [4] |

| Melting Point (Tm) | None defined; softens gradually [13] | Distinct, sharp melting point [13] |

| Shrinkage | Low [13] | High [13] |

| Common Examples | ABS, PC, PS, PMMA [13] | PP, PEEK, PET, POM [13] |

Tg by Polymer Class

Thermoplastics

Thermoplastics are polymers that become soft and moldable upon heating and solidify upon cooling, a process that is reversible [13]. Their behavior is heavily influenced by whether they are amorphous or semi-crystalline.

- Amorphous Thermoplastics: These materials are used below their Tg in their glassy state, where they are hard and rigid [20]. For instance, general-purpose polystyrene (GPPS) with a Tg of ~100°C is a stiff, transparent plastic at room temperature [13].

- Semi-Crystalline Thermoplastics: The amorphous regions of these polymers undergo the glass transition. However, the crystalline regions remain ordered and provide mechanical strength above the Tg until the melting point is reached [13]. Polypropylene (PP), with a Tg of approximately -20°C, is tough and flexible at room temperature but becomes brittle in freezing conditions when the temperature drops below its Tg [13].

Thermosets

Thermoset polymers possess a three-dimensional, cross-linked network structure formed during curing [21]. These cross-links profoundly restrict the mobility of the polymer chains. While the amorphous regions of a thermoset still have a Tg, the extensive cross-linking typically results in a high Tg [13] [19]. The cross-links prevent the polymer from melting upon heating; instead, thermosets will degrade or decompose at high temperatures [13]. They are often used below their Tg, making them rigid and dimensionally stable, as seen in epoxies and phenolics [13]. The Tg of an epoxy resin, for example, is affected by the cross-link density, the choice of curing agent, and fillers [21] [19].

Elastomers

Elastomers are a class of polymers defined by their ability to undergo large, reversible deformations. They are typically used well above their Tg, which is often far below room temperature, ensuring they are in a soft, rubbery state during application [4] [20]. This low Tg allows the polymer chains to be highly mobile and flexible. While some thermoplastic elastomers exist, most conventional elastomers, like liquid silicone rubber (LSR), are lightly cross-linked thermosets. This limited cross-linking provides recovery and prevents permanent flow while maintaining a very low Tg, such as -125°C for LSR [13].

Table 2: Glass Transition Temperature and Application of Common Polymers

| Polymer Class | Material | Tg (°C) | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amorphous Thermoplastic | General Purpose Polystyrene (GPPS) | 100 [13] | Used below Tg; rigid and glassy at room temperature [20] |

| Amorphous Thermoplastic | Polycarbonate (PC) | 145 [13] | Used below Tg; high strength and rigidity at room temperature [13] |

| Semi-Crystalline Thermoplastic | Polypropylene (PP) | -20 [13] | Used above Tg at room temperature; crystalline regions provide structure [13] |

| Semi-Crystalline Thermoplastic | Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) | 140 [13] | High-performance plastic; Tg and Tm allow for high service temperatures. |

| Thermoset | Epoxy Resin | 50 - >250 [19] | High Tg from cross-linking; used for coatings, composites, and adhesives [21] |

| Thermoset Elastomer | Liquid Silicone Rubber (LSR) | -125 [13] | Used far above Tg; highly flexible and rubbery at room temperature [13] |

Factors Influencing Glass Transition Temperature

The Tg of a polymer is not an intrinsic fixed value but is governed by its chemical structure and formulation.

- Molecular Structure and Rigidity: The presence of bulky, inflexible side groups on the polymer backbone restricts rotation around chemical bonds, leading to a higher Tg [19] [4]. A rigid polymer chain, such as that in polyetherimide (PEI, Tg = 210°C), has a much higher Tg than a flexible chain like polyethylene (Tg ≈ -120°C) [13].

- Cross-linking: Chemical cross-links tie polymer chains together, drastically reducing their mobility. An increase in cross-link density leads to a direct increase in Tg [19] [4]. This is a key mechanism for controlling Tg in thermosets like epoxies [21].

- Plasticizers: These are small molecules that insert themselves between polymer chains, effectively increasing the free volume and allowing chains to slide past each other more easily. This results in a decrease in Tg [19] [4]. Plasticizers are commonly used to make materials like PVC flexible.

- Molecular Weight: In linear polymers, increasing molecular weight leads to a higher Tg. This is because chain ends, which constitute regions of higher free volume, become less concentrated as chains get longer [19] [4].

Experimental Determination of Tg

Accurately measuring Tg is crucial for material development and quality control. Several thermo-analytical techniques are employed, each with its own advantages.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

DSC is a widely used technique that measures the difference in heat flow between a sample and a reference as a function of temperature [22] [4]. As the polymer undergoes the glass transition, its heat capacity changes, resulting in a shift in the baseline of the heat flow curve. The Tg is typically reported as the midpoint of this step transition [4].

- Standards: ASTM E1356, ASTM D3418, ISO 11357-2 [4].

- Protocol Outline:

- A small sample (5-10 mg) is sealed in an aluminum crucible.

- The sample and an inert reference are heated at a controlled, constant rate (e.g., 10°C/min) under a nitrogen purge.

- The instrument measures the heat flow difference required to maintain both at the same temperature.

- The resulting thermogram is analyzed for the glass transition step.

Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

DMA is an exceptionally sensitive method for determining Tg as it directly probes the mechanical motions of the polymer chains [22] [23]. A sinusoidal stress is applied to the sample, and the resulting strain is measured. The Tg is identified by a dramatic drop in the storage modulus (E'), which represents the elastic component, and a peak in the loss modulus (E'') or tan δ, which represent the viscous component and damping, respectively [23].

- Standards: ASTM E1640 [4].

- Protocol Outline:

- A sample of defined geometry (e.g., a tension film, a 3-point bend bar) is mounted in the instrument.

- A temperature sweep is conducted at a fixed frequency and strain amplitude.

- The storage modulus (E'), loss modulus (E''), and tan δ are recorded as a function of temperature.

- The Tg can be reported as the onset of the drop in E', or the peak temperature of the E'' or tan δ curves [23].

The following workflow contrasts the operational principles of DSC and DMA, the two most prominent techniques for Tg determination.

Advanced Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Beyond experimental methods, Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation is a powerful computational tool for predicting Tg and understanding its molecular origins. Researchers simulate the behavior of polymer chains at different temperatures using force fields like COMPASS or UFF [21]. Properties such as density, free volume, or mean-squared displacement are tracked, and the Tg is identified by a change in the slope of these properties versus temperature [21]. This method is particularly valuable for screening new polymer compositions or studying the effect of nanofillers (e.g., ZIF-8 metal-organic frameworks in epoxy) before synthesis [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials for Tg Research

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Polymer Tg Analysis

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter | Instrument for measuring heat flow changes associated with Tg and other thermal transitions [22] [4]. |

| Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer | Instrument for applying oscillatory stress to measure viscoelastic properties (E', E'', tan δ) and determine Tg with high sensitivity [22] [23]. |

| High-Purity Indium | A metal standard used for calibration of DSC instruments, due to its sharp and well-defined melting point [4]. |

| Inert Gas Supply (N₂) | Used to purge the DSC and DMA instruments to prevent oxidative degradation of samples during heating [4]. |

| Molecular Simulation Software | Software platforms (e.g., Material Studio) used to build polymer models and perform molecular dynamics simulations to predict Tg [21]. |

| Reference Pan (for DSC) | An empty, sealed crucible used as the inert reference in a DSC experiment [4]. |

| Standard Polymer Samples | Polymers with known and well-characterized Tg values (e.g., Polystyrene) used for method validation and instrument qualification. |

| Curing Agents (e.g., TETA) | Amine-based hardeners used to cross-link epoxy resins, directly influencing the final Tg of the thermoset [21]. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (e.g., ZIF-8) | Nanoporous fillers studied in nanocomposites to modify mechanical properties and Tg of the polymer matrix [21]. |

Why Tg is a Temperature Range, Not a Single Point

The glass transition temperature (Tg) is a critical parameter in material science, particularly for polymers and amorphous solids, dictating their mechanical properties and operational limits. Contrary to common simplification, Tg is not a discrete thermodynamic phase transition but a kinetically controlled process occurring over a temperature range. This whitepaper elucidates the fundamental principles behind the range-like nature of Tg, examining the roles of molecular mobility, thermal history, and experimental conditions. Through detailed experimental protocols and data analysis, we provide researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for accurately characterizing and applying Tg concepts in advanced material design and pharmaceutical development.

The glass–liquid transition, or glass transition, is the gradual and reversible transition in amorphous materials (or in amorphous regions within semicrystalline materials) from a hard and relatively brittle "glassy" state into a viscous or rubbery state as the temperature is increased [1]. An amorphous solid that exhibits a glass transition is called a glass. The glass-transition temperature Tg characterizes the temperature range over which this transition occurs, typically marked by a change in relaxation time on the order of 100 seconds [1]. It is crucial to recognize that this transition is not a first-order phase change like melting or freezing, which occur at a single, well-defined temperature with discontinuous changes in properties such as volume and enthalpy. Instead, the glass transition is a kinetic phenomenon where the material's response is intrinsically linked to the timescale of observation.

The molecular origin of Tg lies in the behavior of polymer chains or the molecules of a glass-forming liquid. Below the Tg range, these molecular segments are frozen in place, resulting in a rigid, glassy state. As temperature increases, these segments gain sufficient thermal energy to initiate rotational and translational motions, leading to a gradual softening of the material over a range of temperatures [13] [1]. This change is a second-order transition marked by a continuous change in primary derivatives of the Gibbs free energy (such as volume and enthalpy) but a discontinuous change in secondary derivatives (such as the thermal expansion coefficient and heat capacity) [1]. The following sections will explore the theoretical underpinnings, experimental evidence, and practical implications of this critical material property.

The Theoretical Foundation: Why Tg is a Range

The Kinetic Nature of the Glass Transition

The fundamental reason Tg manifests as a range, not a point, is its inherent kinetic character. Unlike a true thermodynamic phase transition, the glass transition does not occur at equilibrium. When an amorphous material is cooled, the relaxation time—the time required for molecular segments to reconfigure—increases dramatically. At a certain temperature during cooling, the relaxation time becomes so long that the material cannot reach equilibrium on a practical timescale. The system falls out of equilibrium, and the liquid structure becomes "frozen-in," forming a glass [1]. The temperature at which this occurs depends directly on the cooling rate; a faster cooling rate results in a higher observed Tg because the system has less time to relax and thus falls out of equilibrium at a higher temperature. This direct link between the timescale of the experiment and the measured Tg value is a hallmark of a kinetic process.

The Role of Free Volume and Molecular Mobility

A complementary perspective involves the concept of free volume—the unoccupied space between molecular chains that facilitates movement. As a polymer melt cools, its volume decreases, and the available free volume is reduced. The glass transition range corresponds to the temperature interval where the free volume reaches a critical low value such that the coordinated large-scale motion of chain segments ceases [1]. This process is gradual. Upon heating through the Tg range, the increased molecular vibrations lead to a gradual expansion, creating more free volume and allowing for the onset of molecular mobility. Because the distribution of chain segment lengths and local molecular environments is not uniform, this "unfreezing" does not happen simultaneously for all segments. Segments in less constrained environments may gain mobility at a lower temperature than those in more densely packed or restricted regions, leading to a broadened transition observed over a range.

Experimental Evidence and Measurement Variability

The kinetic nature of Tg is unequivocally demonstrated by the fact that its measured value is dependent on experimental conditions. Various techniques probe different aspects of molecular mobility, and each operates on a specific timescale, leading to variations in the reported Tg.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Protocol

Objective: To determine the glass transition temperature by measuring the change in heat capacity as a function of temperature.

- Sample Preparation: Precisely weigh 5-10 mg of the sample into an aluminum DSC crucible and seal it with a lid. An empty, sealed crucible serves as a reference.

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate the DSC cell for temperature and enthalpy using high-purity standards such as indium and zinc.

- Experimental Method:

- Purge the DSC cell with an inert gas (e.g., Nitrogen at 50 mL/min).

- Load the sample and reference crucibles.

- Cool the sample to at least 50°C below the expected Tg at a controlled rate (e.g., 10°C/min) and hold isothermally for 5 minutes to establish a uniform thermal history.

- Heat the sample at a standard rate (e.g., 10°C/min) to a temperature above the transition.

- Data Analysis: Identify the Tg from the resulting heat flow curve. It is conventionally reported as the midpoint of the step change in heat capacity, as illustrated in the figure below. The onset and endset temperatures of this step clearly define the range of the transition [1].

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) and Derivative (DTG) Protocol

Objective: To assess thermal stability and decomposition, which can be related to the upper limits of material use, often informed by Tg.

- Sample Preparation: Load approximately 7 mg of sample into a platinum pan.

- Instrument Setup: Utilize a TGA Q500 thermal gravimetric analyzer or equivalent. Maintain a nitrogen atmosphere with a flow rate of 90 mL/min [24].

- Experimental Method:

- Begin at 30 ± 5 °C.

- Heat the sample to 1000 °C at a constant heating rate of 10 °C/min.

- Data Analysis: Record the mass loss (TG curve). The derivative of the TG curve (DTG) identifies temperatures of maximum mass loss rate. While not a direct measure of Tg, this protocol characterizes degradation events that constrain the practical application temperature window relative to Tg [24].

Impact of Measurement Parameters on Tg

The measured Tg value is not a fixed material constant but is influenced by operational definitions, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Impact of Experimental Conditions on Measured Tg

| Experimental Factor | Effect on Measured Tg | Theoretical Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Heating/Cooling Rate | Faster rates lead to a higher measured Tg. | A faster rate gives molecular chains less time to relax, so the system falls out of equilibrium at a higher temperature [1]. |

| Measurement Technique | Different methods (DSC, Dilatometry, DMA) yield different Tg values. | Each technique probes different physical properties (heat capacity, volume, modulus) with different characteristic timescales [1]. |

| Material History | Annealing below Tg can lower the measured Tg; prior stress can raise it. | Thermal and mechanical history alters the non-equilibrium frozen-in structure, affecting the energy required to initiate molecular motion [1]. |

This variability is not an experimental error but a direct consequence of the kinetic nature of the glass transition. Therefore, reporting Tg requires specifying the experimental method and conditions to be scientifically meaningful.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Characterizing Tg and developing materials based on its principles requires a specific set of reagents and analytical tools. The following table outlines essential solutions and materials used in this field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Tg Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Polymer Standards (e.g., PS, PMMA) | Used for calibration of thermal analyzers like DSC and TGA. Their well-established Tg values provide a reference for method validation [1]. |

| Inert Gas (e.g., Nitrogen, 50-90 mL/min) | Purge gas in thermal analysis instruments (DSC, TGA) to prevent oxidative degradation of samples at high temperatures, ensuring data reflects thermal transitions rather than chemical decomposition [24]. |

| Dielectric Spectroscopy Fluids | Immersion fluids for dielectric analysis (DEA), a technique that measures molecular mobility by monitoring dielectric loss, providing another way to characterize the Tg range via relaxation times. |

| Enteric-Coating Polymers (e.g., Cellulose Acetate Phthalate) | Used in pharmaceutical development to create drug delivery systems with targeted release. Their Tg and dissolution pH are critical for controlling drug release kinetics in the gastrointestinal tract [25]. |

| Biodegradable Polymers (e.g., PLA, PLGA) | Key materials in modern drug delivery systems. Their Tg dictates drug release profiles, device stability, and degradation rates in vivo [25]. |

| Ligand-Functionalized Nanocarriers | Components of actively targeted drug delivery systems. The Tg of the nanocarrier material influences its stability, drug release, and ability to accumulate at target tissues [25]. |

Implications for Drug Development and Material Science

Understanding Tg as a range, not a point, has profound implications, especially in the development and manufacturing of biologics and solid dosage forms.

Stability of Amorphous Solid Dispersions

Many modern drugs are formulated as amorphous solid dispersions to enhance bioavailability. These metastable systems are prone to crystallization, which can reduce drug absorption. The breadth of the Tg range informs the storage conditions and shelf-life predictions. Storage closer to or above the Tg range dramatically increases molecular mobility, potentially leading to rapid crystallization. Understanding the range allows formulators to define a safe storage temperature margin rather than relying on a single, potentially misleading, Tg point [25].

Process Development and Manufacturing

In processes like lyophilization (freeze-drying) of biologics, the product is often stabilized in an amorphous glassy matrix. The primary drying phase must be conducted below Tg' (the glass transition temperature of the maximally concentrated freeze-concentrate) to avoid collapse, which compromises stability and product appearance. As Tg is a range, process design must account for this, ensuring the product temperature remains safely within the glassy state throughout the process, guaranteeing stability and efficacy of the final drug product [26].

Material Selection and Performance

For polymeric materials used in medical devices or packaging, the Tg range determines their mechanical behavior in use. A polymer with a broad Tg transition may exhibit a gradual softening, which can be desirable for certain applications, while a sharp transition might be needed for others. The relationship between Tg and other thermal properties is critical for selection, as shown in the comparative data for common polymers below.

Table 3: Glass Transition Temperature Data for Selected Polymers [27] [13] [1]

| Polymer | Tg Range / Value (°C) | Material Class | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polycarbonate (PC) | 145 - 150 | Amorphous | High impact strength, transparency, used well below its Tg in its glassy state [13] [1]. |

| Polystyrene (PS) | 83 - 102 | Amorphous | Hard, rigid plastic; used in its glassy state well below Tg [27] [1]. |

| Polypropylene (PP) | -20 to -10 | Semi-crystalline | Becomes brittle below its Tg; used above Tg where crystalline regions provide structure and flexibility [27] [13]. |

| Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) | 140 - 157 | Semi-crystalline | High-performance thermoplastic; can be used above its Tg due to strong crystalline structure [27] [13]. |

| Liquid Silicone Rubber (LSR) | -125 | Thermoset Elastomer | Crosslinked structure allows it to be used far above its Tg, remaining flexible and rubbery [13]. |

| Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) unplasticized | 60 - 100 | Amorphous | Tg range shows dependence on formulation and molecular weight; rigid at room temperature [27] [1]. |

The glass transition temperature, Tg, is fundamentally a temperature range due to its kinetic nature and the distribution of molecular relaxation times within amorphous materials. It is not a single point and is unequivocally influenced by experimental parameters and material history. A deep understanding of this concept is not merely academic; it is essential for robust material selection, predictive stability modeling, and reliable process development in advanced industries, including pharmaceutical drug product development. Framing Tg as a range provides a more accurate and powerful framework for designing and characterizing the next generation of advanced materials and therapeutic formulations.

Measuring Tg and Its Critical Role in Drug Delivery and Material Design

The glass transition temperature (Tg) is a fundamental thermal property of amorphous materials and the amorphous regions of semi-crystalline polymers. It defines the critical temperature at which a polymer transitions from a hard, glassy state to a soft, rubbery state [4]. This transition is not a first-order phase change like melting but a second-order transition associated with a change in the slope of physical properties such as volume, enthalpy, and modulus [28]. Understanding and accurately measuring Tg is crucial for predicting material performance, including mechanical properties, thermal stability, and solubility, which is vital for applications ranging from pharmaceutical formulation to plastic manufacturing [28] [4].

At the molecular level, below the Tg, polymer chains are frozen in place, lacking the mobility to slide past one another. Above the Tg, sufficient thermal energy allows for the onset of coordinated molecular motion, leading to a dramatic change in material properties [4]. The value of Tg is influenced by several factors, including molecular weight, chemical structure, the presence of plasticizers (like water), and cross-link density [28] [4]. For instance, increasing molecular weight generally increases Tg, while the addition of plasticizers decreases it [28].

Principal Techniques for Tg Measurement

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Principle of Operation: Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) is a thermo-analytical technique that measures the difference in heat flow between a sample and an inert reference as they are subjected to a controlled temperature program [29] [30]. When a material undergoes its glass transition, the heat capacity changes, resulting in a shift in the baseline of the heat flow curve [30] [31]. This shift appears as a step change in the DSC thermogram, as the amorphous regions require more energy to increase in temperature once the chains gain mobility [4].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: A small sample (typically 5-20 mg) is placed in a hermetic or vented crucible. For solids, a thin disk or powder is used to ensure good thermal contact [30] [31].

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate the instrument for temperature and enthalpy using high-purity standards like indium [32].

- Method Development: Select a temperature range that encompasses the expected Tg. A common heating rate is 10°C/min under an inert nitrogen purge [30] [33]. For more complex transitions, Temperature Modulated DSC (MDSC) can be employed to separate overlapping thermal events [30].

- Data Analysis: The glass transition is identified as a step change in the heat flow curve. The Tg value is typically reported as the mid-point of the transition between the extrapolated onset and endset temperatures, as defined by standards like ASTM E1356 [4].

Strengths and Limitations:

- Strengths: The technique is relatively fast, requires a small sample size, and provides quantitative data on other thermal events like melting, crystallization, and cure enthalpy [30] [31]. It is a standardized and widely accessible method.

- Limitations: DSC can lack sensitivity for detecting Tg in materials with very weak heat capacity changes, such as highly cross-linked polymers, filled materials, or thin layers [34] [31]. The signal can also be obscured if decomposition occurs in the same temperature region [30].

Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

Principle of Operation: Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) applies a sinusoidal oscillating stress to a sample and measures the resulting strain [34] [30]. This technique characterizes the viscoelastic properties of a material by determining the storage modulus (E' or G'), which represents the elastic component; the loss modulus (E" or G"), which represents the viscous component; and the damping factor (tan δ = E"/E') [34] [30]. The glass transition is marked by a dramatic drop in the storage modulus and a distinct peak in the tan δ curve, as the material's ability to dissipate energy (damping) reaches a maximum [30].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: The sample must be machined or molded into a specific geometry (e.g., a rectangular bar, thin film, or fiber) compatible with the clamping mode (tension, compression, flexure, or shear) [30].

- Clamping and Alignment: The sample is securely mounted in the chosen clamp, ensuring proper alignment and contact. An initial low force may be applied to keep the sample taut [30].

- Method Development: An amplitude sweep is first performed to determine the Linear Viscoelastic Range (LVR). A temperature ramp is then defined with a specific oscillatory frequency (e.g., 1 Hz) and a controlled heating rate (e.g., 2-5°C/min) [34] [30].

- Data Analysis: The glass transition temperature is most sensitively identified from the peak maximum of the tan δ curve. The onset of the drop in the storage modulus can also be reported [34] [30].

Strengths and Limitations:

- Strengths: DMA is the most sensitive method for detecting Tg, capable of characterizing subtle transitions like β-relaxations and measuring Tg in thin films or highly filled composites where DSC might fail [34] [31]. It provides a full viscoelastic profile of the material.

- Limitations: The technique is more complex and expensive than DSC. Sample preparation is more involved, and the sample must be self-supporting in a defined geometry [31].

Thermomechanical Analysis (TMA)

Principle of Operation: Thermomechanical Analysis (TMA) measures the dimensional changes of a material (such as expansion or penetration) under a static load as a function of temperature or time [29] [34]. Below the Tg, the material expands at a certain rate. As it passes through the glass transition into the rubbery state, the rate of expansion increases significantly due to greater molecular mobility, which appears as a change in the slope of the dimensional change curve [34]. In penetration mode, the probe will noticeably sink into the sample as the material softens at Tg [34].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: A solid sample with flat, parallel surfaces is required. Typical sample thickness is around 0.5 mm for penetration mode [34].

- Probe Selection: Choose the appropriate probe (e.g., flat-ended for expansion, spherical-ended for penetration) based on the property of interest [34].

- Method Development: A very low constant force (e.g., 0.005 N for expansion, 0.1-0.5 N for penetration) is applied to the probe. A controlled heating rate (e.g., 5-20°C/min) is set [34].

- Data Analysis: The Tg is determined from the onset or intersection point of the two linear portions of the dimensional change curve, indicating the change in the coefficient of thermal expansion [34].

Strengths and Limitations:

- Strengths: TMA is excellent for directly measuring properties like the coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) and softening point [34] [31]. It can be more accurate than DSC for measuring Tg in highly cross-linked or filled materials [31].

- Limitations: The measured Tg can be influenced by the applied load and heating rate. Sample preparation must ensure good contact and parallelism [34] [33].

Comparative Analysis of Techniques

Table 1: Comparison of Key Tg Measurement Techniques

| Feature | DSC | DMA | TMA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Property Measured | Heat Flow (Change in Heat Capacity) [29] [30] | Viscoelastic Moduli (E', E", tan δ) [34] [30] | Dimensional Change (Expansion/Penetration) [29] [34] |

| Typical Tg Indicator | Mid-point of step change in baseline [4] | Peak of tan δ curve [34] [30] | Onset of change in slope (expansion) [34] |

| Sensitivity to Tg | Moderate | Very High [34] [31] | Moderate to High [31] |

| Sample Requirements | Small (1-20 mg); powder, film, or chip [30] [31] | Specific geometry required (bar, film); self-supporting [30] [31] | Solid with flat surfaces; defined geometry helpful [34] [31] |

| Additional Information | Melting point, crystallization, enthalpy, purity [30] [31] | Full viscoelastic spectrum, sub-Tg relaxations, cross-link density [34] [30] | Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE), softening point [34] [31] |

Table 2: Example Tg Values for Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Measured by Different Techniques [34]

| Technique | Experimental Conditions | Reported Tg |

|---|---|---|

| DSC | Heating rate: 20 K/min | 80 °C |

| TGA/DSC | Heating rate: 20 K/min, in N₂ | 81 °C |

| TMA | Heating rate: 20 K/min | 77 °C |

| DMA | Frequency: 1 Hz, Heating rate: 2 K/min (tan δ peak) | 81 °C |

The data in Table 2 demonstrates that while different techniques can yield slightly different absolute values for Tg due to their specific measurement principles and conditions, the results are generally consistent. DMA, reporting from the tan δ peak, is often considered the most sensitive indicator of the molecular mobility associated with the glass transition [34].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Tg Analysis

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Hermetic Crucibles/Pans (DSC) | To encase samples and prevent vaporization of volatile components during heating, ensuring accurate mass and heat flow measurement [30]. |

| Inert Purge Gas (e.g., Nitrogen) | Standard atmosphere for DSC and TGA to prevent oxidative degradation during heating, allowing for the measurement of intrinsic thermal properties [30] [31]. |

| Calibration Standards (e.g., Indium, Zinc) | High-purity metals with known melting points and enthalpies used for accurate temperature and heat flow calibration of DSC instruments [32]. |

| Polymer Reference Materials | Well-characterized polymers with known Tg values (e.g., Polystyrene) used for verification of method accuracy and instrument performance across all techniques [4]. |

| Clamp Kits and Probes (DMA/TMA) | Various fixtures (tension, 3-point bend, compression, shear) and probes (expansion, penetration) to accommodate different sample types and measurement modes [34] [30]. |

DSC, DMA, and TMA are the three primary techniques for measuring the glass transition temperature (Tg), each with distinct principles and applications. DSC is a versatile and widely used method for general thermal characterization. DMA offers superior sensitivity for detecting Tg and other transitions, providing a deep understanding of a material's mechanical behavior. TMA is the preferred technique when dimensional stability and thermal expansion are critical parameters.

These techniques are highly complementary. A comprehensive material characterization strategy often begins with DSC for a broad overview, followed by DMA for detailed mechanical analysis and TMA for dimensional studies. The choice of technique depends on the specific material, the property of interest, and the required sensitivity, enabling researchers and product developers to make informed decisions for material selection, processing, and application performance.

The glass transition temperature (Tg) is a critical physical parameter in polymer science, marking the temperature at which an amorphous material transitions from a hard, glassy state to a soft, rubbery state [35]. This transition profoundly impacts material properties, including stiffness, ductility, and thermal stability [35]. Within the broader context of Tg research, understanding the capabilities and limitations of different measurement techniques is paramount. This guide provides an in-depth comparative analysis of the primary methods for Tg determination, focusing on their relative sensitivity and the intricacies of data interpretation, to aid researchers in selecting the most appropriate methodology for their specific applications.

Fundamental Principles of Glass Transition

The glass transition is a second-order transition, manifesting as a step change in physical properties rather than a distinct phase change with latent heat [35]. At the molecular level, as temperature increases, thermal energy overcomes the intermolecular forces restricting the polymer chains, allowing them to undergo large-scale molecular motions [23]. This increase in chain mobility results in significant changes in the material's thermal, mechanical, and electrical properties [35]. Unlike melting, which is a first-order transition at a specific temperature (Tm) for crystalline regions, the glass transition occurs over a temperature range and is a property of the amorphous regions of a polymer [4].

Several analytical techniques are employed to characterize the glass transition, each probing different material properties affected by this transition. The most prominent methods include Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA), Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC), and Thermomechanical Analysis (TMA). The choice of technique often depends on the nature of the sample and the specific property of interest for the application.

Table 1: Summary of Primary Tg Measurement Methods

| Method | Property Measured | Principle of Operation | Best For Applications Involving |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) [16] [23] | Changes in mechanical properties (storage modulus E', loss modulus E", tan δ) | Applies a small oscillatory stress/deformation and measures the resultant strain. | Structural polymers, composites, and materials where mechanical performance is critical [35] [16]. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) [35] [4] | Heat flow difference between sample and reference | Measures the energy absorbed or released by the sample during thermal transitions. | Polymers used in thermal applications, quality control, and general thermal characterization [35]. |

| Thermomechanical Analysis (TMA) [35] | Dimensional changes (thermal expansion/compression) | Measures the change in size of a sample under a negligible load as a function of temperature. | Coatings, adhesives, and films where dimensional stability is key [35]. |

| Dielectric Analysis (DEA) [35] | Changes in electrical properties (dielectric constant, loss factor) | Monitors the material's response to an oscillating electrical field. | Polymers for electronics, insulation, and materials with polar groups [35]. |

Figure 1: Tg Measurement Techniques and Properties Probed

In-Depth Methodological Analysis

Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

Experimental Protocol

DMA characterizes the viscoelastic properties of a material by applying a small, sinusoidal deformation and measuring the resulting stress [16]. Standard test specimens, such as rectangular bars (e.g., 50 mm x 10 mm x 2 mm) or cylindrical rods, are used [36]. The experiment involves a temperature ramp, typically at a rate of 2°C/min to 5°C/min, while the sample is subjected to oscillatory stress at a fixed frequency, commonly 1 Hz [16] [36]. It is critical to validate that the chosen ramp rate does not introduce thermal lag, which can be done by comparing results with a temperature sweep method that allows for full thermal equilibration at each step [16]. The key parameters measured are:

- Storage Modulus (E' or G'): The elastic component, representing the energy stored and recovered per cycle.