FAIR Data Principles for Polymer Informatics: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide to implementing FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data principles in polymer informatics.

FAIR Data Principles for Polymer Informatics: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to implementing FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data principles in polymer informatics. It explores the foundational concepts and unique challenges of applying FAIR to polymeric data, presents practical methodologies for data management and pipeline integration, addresses common pitfalls and optimization strategies for large datasets, and offers frameworks for validation and comparison of approaches. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content bridges the gap between data science best practices and the specific needs of polymer-based biomedical research, ultimately aiming to accelerate innovation in drug delivery, biomaterials, and therapeutic development.

What Are FAIR Data Principles and Why Are They Critical for Polymer Informatics?

Polymer informatics research, a critical discipline for accelerating materials discovery in drug delivery systems and biomedical devices, generates vast and complex datasets. The heterogeneity of data—spanning molecular structures, synthesis protocols, physicochemical properties, and performance metrics—creates significant barriers to data integration and knowledge discovery. The FAIR Guiding Principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) provide a structured framework to overcome these barriers, transforming fragmented data into a cohesive, machine-actionable knowledge ecosystem. This technical guide deconstructs each FAIR principle within the polymer informatics context, providing methodologies for implementation.

Core Principles and Technical Specifications

Findable (F)

The first step in data utility is ensuring it can be discovered by both humans and computational agents.

- F1: (Meta)data are assigned a globally unique and persistent identifier (PID).

- Protocol: Assign PIDs like Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs) via a registry (e.g., DataCite, Crossref) or use resolvable URIs/IRIs. For internal datasets, use UUIDs or handles. The identifier must resolve to the metadata or the data itself.

- F2: Data are described with rich metadata.

- Protocol: Define a minimum metadata schema specific to polymer science. For example, for a polymer nanoparticle dataset, required fields may include: monomer SMILES, polymer architecture (e.g., linear, star), molecular weight (Mn, Mw), dispersity (Đ), nanoparticle size (DLS), zeta potential, and encapsulation efficiency.

- F3: Metadata clearly and explicitly include the identifier of the data it describes.

- Protocol: The PID must be an explicitly defined field within the metadata record, not merely embedded in a text description.

- F4: (Meta)data are registered or indexed in a searchable resource.

- Protocol: Deposit metadata in a public or institutional repository (e.g., Zenodo, Figshare, specialized repositories like the Materials Data Facility) or a domain-specific portal with a search API.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Findability Measures on Data Discovery

| Metric | Non-FAIR Baseline | With Basic Metadata (Title, Author) | With Rich FAIR Metadata (Structured Fields, PIDs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Search Recall | 15-30% | 40-60% | >85% |

| Machine-Actionable Discovery | <5% | 10-20% | 70-90% |

| Time to Locate Key Dataset | Hours-Days | Minutes-Hours | Seconds-Minutes |

Accessible (A)

Once found, data and metadata must be retrievable using standard, open protocols.

- A1: (Meta)data are retrievable by their identifier using a standardized communications protocol.

- Protocol: Provide data access via HTTPS/HTTP, FTP, or APIs (e.g., REST, GraphQL). The protocol must be open, free, and universally implementable.

- A1.1: The protocol is open, free, and universally implementable.

- A1.2: The protocol allows for an authentication and authorization procedure, where necessary.

- Protocol: Implement OAuth 2.0, API keys, or other standard authentication/authorization mechanisms for sensitive data (e.g., pre-publication data). Access controls must be clearly documented.

- A2: Metadata are accessible, even when the data are no longer available.

- Protocol: Ensure metadata records persist independently and state the data's availability status (e.g., "deprecated," "withdrawn," "embargoed until [date]").

Interoperable (I)

Data must be able to integrate with other data and applications through shared vocabularies and formats.

- I1: (Meta)data use a formal, accessible, shared, and broadly applicable language for knowledge representation.

- Protocol: Use standardized, open file formats (e.g., JSON-LD, XML, CSV with defined schema) instead of proprietary formats (e.g., raw instrument files, proprietary spreadsheet formats).

- I2: (Meta)data use vocabularies that follow FAIR principles.

- Protocol: Use ontologies and controlled vocabularies. For polymer informatics: ChEBI (chemical entities), SIO (semantic science), PDO (polymer ontology), and QUDT (quantities, units, dimensions).

- I3: (Meta)data include qualified references to other (meta)data.

- Protocol: Link data to related resources using their PIDs. For example, link a polymer dataset to the relevant monomer entries in PubChem using InChIKeys or PubChem CIDs.

Table 2: Interoperability Tools for Polymer Data

| Data Type | Recommended Format/Standard | Recommended Controlled Vocabulary/Ontology |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Structure | SMILES, InChI, MOL/SDF File | IUPAC nomenclature, ChEBI, PubChem Compound |

| Polymer Characterization | JSON, XML with defined schema | PDO, ChEBI, QUDT (for units like g/mol, nm) |

| Experimental Procedure | TEI (Text Encoding Initiative), Markdown with tags | Ontology for Biomedical Investigations (OBI) |

| Material Property Data | CSV with JSON Schema, HDF5 | EMPReSS, MAT-DB Ontology |

Reusable (R)

The ultimate goal is to optimize data reuse, requiring detailed provenance and domain-relevant community standards.

- R1: (Meta)data are richly described with a plurality of accurate and relevant attributes.

- Protocol: Provide comprehensive metadata covering: creator, publisher, date, funding, license, methodological details, data processing steps, and parameters relevant to polymer science (as in F2).

- R1.1: (Meta)data are released with a clear and accessible data usage license.

- Protocol: Attach a machine-readable license (e.g., Creative Commons CC-BY, CC0, MIT) using SPDX license identifiers.

- R1.2: (Meta)data are associated with detailed provenance.

- Protocol: Document the origin, processing, and transformation history of the data. Use standards like PROV-O.

- R1.3: (Meta)data meet domain-relevant community standards.

- Protocol: Adhere to guidelines from relevant consortia (e.g., Materials Genome Initiative (MGI) standards, IUPAC polymer reporting guidelines).

FAIR Data Implementation Workflow

Experimental Protocol: Implementing FAIR for a Polymer Nanoparticle Dataset

This protocol outlines the steps to publish a dataset from a study on "Polymer Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery" following FAIR principles.

1. Preparation Phase:

- Data Curation: Consolidate all raw and processed data (e.g., GPC chromatograms, DLS correlation functions, HPLC drug release profiles).

- Define Schema: Create a JSON Schema defining the structure for the final dataset, including required fields (PID, polymer properties, experimental conditions).

2. Findability Implementation:

- Generate a unique UUID for the dataset.

- Create a

metadata.jsonfile. Populate with fields:dataset_id(UUID),title,creators,description,keywords(e.g., "block copolymer", "nanoprecipitation"),publication_date. - Map all chemical structures to InChIKeys and SMILES strings.

3. Accessibility & Interoperability Implementation:

- Convert all data files to open formats (CSV for tables, JSON for structured metadata).

- Annotate data columns using terms from controlled vocabularies. Example:

"measurement": {"value": 25.5, "unit": "nm", "label": "hydrodynamic diameter", "ontology_id": "PDO:001234"}. - Write a

README.mdfile detailing the experimental methods.

4. Reusability Implementation:

- Attach a

license.txtfile (CC-BY 4.0). - Document provenance in a

provenance.jsonfile using PROV-O templates, detailing instrument models, software versions (e.g., Gaussian 16, Malvern Zetasizer), and data processing scripts. - Package all files into a compressed archive.

5. Deposition:

- Upload the archive to a repository like Zenodo, which will mint a DOI (fulfilling F1 and A1).

- The repository's API makes the data accessible programmatically.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for FAIR Polymer Data

Table 3: Essential Tools for Creating FAIR Polymer Informatics Data

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Example(s) | Function in FAIRification |

|---|---|---|

| Persistent Identifier Services | DataCite DOI, Handle.Net, UUID | Provides globally unique, resolvable identifiers for datasets (F1). |

| Metadata Schema Tools | JSON Schema, XML Schema (XSD), Dublin Core | Defines the structure and required fields for metadata, ensuring consistency (F2, R1). |

| Controlled Vocabularies & Ontologies | Polymer Ontology (PDO), ChEBI, QUDT, OBI | Provides standardized terms for describing materials, processes, and measurements, enabling interoperability (I2). |

| Data Repository Platforms | Zenodo, Figshare, Materials Data Facility (MDF), Institutional Repositories | Provides a searchable resource for registration, storage, and access with standardized APIs (F4, A1). |

| Provenance Tracking Tools | PROV-O, Research Object Crates (RO-Crate) | Captures and formally represents the origin and processing history of data, critical for reuse and reproducibility (R1.2). |

| Data Format Converters | Open Babel (chemical formats), pandas (Python dataframes), custom scripts | Converts proprietary or raw data into open, standardized formats (I1). |

Components Enabling FAIR Data Interoperability

The systematic application of the FAIR principles is not merely a data management exercise but a foundational requirement for advancing polymer informatics. By making data findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable, the research community can build upon a cumulative knowledge base, accelerating the design of novel polymers for drug delivery, diagnostics, and therapeutics. The technical protocols and toolkits outlined here provide a concrete starting point for researchers to contribute to and benefit from this transformative paradigm.

The adoption of FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) data principles is critical for accelerating discovery in materials science. For polymer informatics, achieving FAIR compliance presents unique, multidimensional challenges that extend far beyond those encountered in small-molecule or protein research. Unlike discrete chemical entities, polymers are defined by distributions—in molecular weight, chain length, sequence, and stereochemistry—creating a complex data landscape that demands specialized solutions.

The Multifaceted Nature of Polymer Data

Polymer data is intrinsically hierarchical and probabilistic. A single "polymer" is an ensemble of chains, each with potential variations. Key data dimensions include:

Table 1: Core Data Dimensions in Polymer Science

| Data Dimension | Description | Key Metrics | Contrast with Small Molecules/Proteins |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | Distribution, not a single value. | Mn, Mw, Đ (Dispersity). | Single, exact molecular weight. |

| Chain Topology | Arrangement of linear, branched, network, or cyclic structures. | Branching density, degree of crosslinking. | Proteins have defined folding; small molecules have fixed connectivity. |

| Chemical Composition | May include copolymers with sequence distributions. | Block length, randomness index, tacticity. | Defined sequence (proteins) or single structure (small molecules). |

| Synthesis Conditions | Non-linear effects on final properties. | Temperature, time, catalyst/initiator concentration, pressure. | Often less sensitive to exact conditions for reproducibility. |

| Processing History | Thermomechanical history greatly influences properties. | Shear rate, cooling rate, annealing time. | Largely irrelevant for small molecules; proteins can denature. |

This ensemble nature requires that any FAIR-compliant data repository must capture distribution functions and correlate them with synthesis parameters and multi-scale properties.

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Key Polymer Properties

Protocol 2.1: Determining Molecular Weight Distribution via Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC/SEC)

Objective: To separate polymer chains by hydrodynamic volume and determine the molecular weight distribution (MWD). Materials: Polymer solution (0.5-1.0 mg/mL in appropriate eluent), degassed eluent (e.g., THF with 250 ppm BHT for polystyrene), GPC/SEC system (pump, injector, columns, detectors). Method:

- Column Calibration: Inject a series of narrow dispersity polymer standards of known molecular weight. Construct a calibration curve of log(M) vs. retention time.

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve the unknown polymer sample completely and filter (0.2 µm PTFE filter) to remove particulates.

- System Equilibration: Flow eluent through columns at 1.0 mL/min until a stable baseline is achieved on the refractive index (RI) and light scattering (LS, if used) detectors.

- Injection & Separation: Inject 100 µL of sample. Polymers are separated as they pass through porous column packing; larger chains elute first.

- Data Analysis: Using the calibration curve and detector response (RI for concentration, LS for absolute molecular weight), calculate number-average (Mn), weight-average (Mw) molecular weights, and dispersity (Đ = Mw/Mn). Advanced analysis with a multi-detector system (RI, LS, viscometer) provides absolute molecular weight and branching information.

Protocol 2.2: Characterizing Thermal Transitions via Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Objective: To measure glass transition (Tg), melting (Tm), and crystallization (Tc) temperatures and associated enthalpies. Materials: Hermetically sealed aluminum DSC pans, reference pan, purified polymer sample (5-10 mg). Method:

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate temperature and enthalpy using indium and zinc standards.

- Sample Encapsulation: Precisely weigh the sample into a pan and seal it. Prepare an empty, sealed pan as a reference.

- Thermal Program: (i) First heat: Ramp from -50°C to 200°C at 10°C/min to erase thermal history. (ii) Cool: Ramp down to -50°C at 10°C/min. (iii) Second heat: Repeat the heating ramp to 200°C at 10°C/min.

- Data Collection: Record heat flow (mW) as a function of temperature.

- Analysis: Analyze the second heating curve. The Tg is identified as the midpoint of the step change in heat capacity. Tm and Tc are identified as the peak of the endothermic and exothermic events, respectively. Enthalpies (ΔH) are calculated from the area under these peaks.

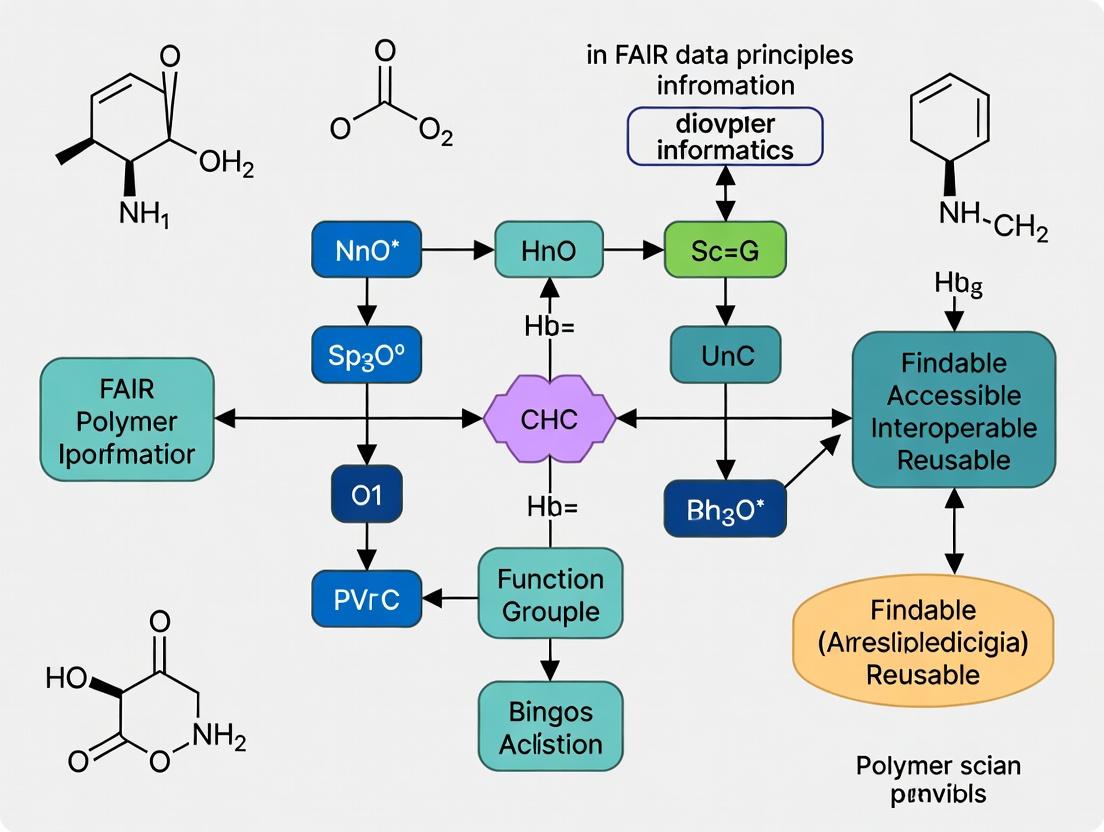

Visualization of Polymer Informatics Workflow and Challenges

Title: Polymer FAIR Data Workflow & Challenges

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Polymer Characterization

| Item | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Narrow Dispersity Polymer Standards | Calibration of GPC/SEC for accurate molecular weight distribution analysis. | Must match polymer chemistry (e.g., polystyrene, PMMA) and column/solvent system. |

| Deuterated Solvents for NMR (e.g., CDCl3, DMSO-d6) | Provide a signal for spectrometer locking and enable structural analysis via 1H/13C NMR. | Must fully dissolve polymer; must be dry to prevent chain degradation for some polymers. |

| Thermal Analysis Standards (Indium, Zinc, Tin) | Calibration of temperature and enthalpy scales in DSC and TGA instruments. | High purity (≥99.99%) required for accurate calibration. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography Columns | Separation of polymer chains by hydrodynamic size in solution. | Pore size must be selected to match the molecular weight range of the analyte. |

| Rheometer Parallel Plates | Measure viscoelastic properties (viscosity, moduli) of polymer melts or solutions. | Plate material (e.g., steel, aluminum) and diameter must be chosen based on sample stiffness and volume. |

| Functionalized Initiators/Chain Transfer Agents | Introduce specific end-groups during controlled radical polymerization (ATRP, RAFT). | Critical for synthesizing block copolymers or telechelic polymers for further reaction. |

| High-Temperature GPC Solvents (e.g., 1,2,4-Trichlorobenzene) | Dissolve and characterize semi-crystalline polymers (e.g., polyolefins) at elevated temperatures. | Requires a dedicated, heated GPC system with appropriate columns and detectors. |

Pathway to FAIR Polymer Data: A Roadmap

Implementing FAIR principles necessitates community-wide standards for representing polymer complexity.

Title: FAIR Data Implementation Roadmap for Polymers

Conclusion: The path to FAIR data in polymer science is not merely an extension of existing cheminformatics frameworks. It requires a fundamental rethinking of data representation to capture stochastic synthesis, hierarchical structure, and process-dependent properties. Success hinges on developing specialized tools, ontologies, and repositories that embrace polymer complexity, thereby unlocking the transformative potential of data-driven polymer discovery and design.

The application of FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data principles to polymer informatics is revolutionizing the discovery and development of advanced materials for biomedical applications. By creating structured, machine-actionable datasets from historically disparate experimental results, researchers can dramatically accelerate the design cycle for drug delivery systems, biomaterials, and formulations. This technical guide details the methodologies, tools, and data frameworks enabling this paradigm shift.

Polymer informatics applies data-driven methodologies to the complex design space of macromolecules for biomedical use. The inherent heterogeneity of polymer structures (monomer composition, sequences, architectures, molecular weights) and their processing-dependent properties creates a vast multivariate challenge. FAIR principles provide the necessary scaffold to convert isolated experimental data into a predictive knowledge graph.

Core Challenge: Traditional discovery relies on serial, intuition-driven experimentation, leading to prolonged development timelines (often 10-15 years for new biomaterials). The informatics approach, built on FAIR data, enables parallel virtual screening and predictive modeling.

Quantitative Impact: Acceleration Metrics

The implementation of a FAIR-compliant polymer informatics platform yields measurable reductions in development timelines and costs.

Table 1: Comparative Metrics for Discovery Timelines

| Development Phase | Traditional Approach (Months) | FAIR Informatics Approach (Months) | Acceleration Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excipient/ Polymer Selection | 6-12 | 1-2 | ~6x |

| Formulation Optimization | 12-24 | 3-6 | ~4x |

| In Vitro Biocompatibility Screening | 6-9 | 1-3 | ~4x |

| Lead Candidate Identification | 24-36 | 6-12 | ~3-4x |

| Total (Estimated) | 48-81 | 11-23 | ~4x |

Table 2: Data Reuse Efficiency Gains

| Metric | Pre-FAIR Implementation | Post-FAIR Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Data Findability | <30% | >90% |

| Data Interoperability (Standardized Formats) | Low (Proprietary Formats) | High (JSON-LD, .polymer) |

| Machine-Actionable Data Readiness | <10% | >75% |

| Reduction in Redundant Experiments | Baseline | 40-60% |

Experimental Protocols for Generating FAIR Polymer Data

To build a high-quality informatics knowledge base, standardized experimental protocols are essential. Below are detailed methodologies for key characterization experiments.

Protocol 3.1: High-Throughput Polymer Synthesis & Characterization for FAIR Databasing

Objective: To synthesize a library of polymeric carriers with systematic variation in properties and record all data in a FAIR-compliant schema.

- Synthesis (RAFT Polymerization Example):

- Reagents: Monomer(s), RAFT agent, initiator (e.g., AIBN), solvent.

- Procedure: In a 96-well plate reactor, prepare stock solutions. Dispense varying ratios of monomers and chain transfer agent using liquid handling robots. Initiate polymerization under inert atmosphere at 70°C for 24h. Terminate by cooling and exposure to air.

- FAIR Data Capture: Record all parameters (SMILES strings of reagents, exact molar ratios, temperature, time) using a structured electronic lab notebook (ELN) with pre-defined fields linked to ontologies (e.g., CHEBI, ChEBI).

- Characterization:

- GPC/SEC: Measure Mn, Mw, and Đ. Metadata: Include solvent, column type, calibration standard, and raw data file link (e.g., .txt).

- NMR: Confirm composition and end-group fidelity. Metadata: Solvent, frequency, pulse sequence.

- FAIR Output: A single JSON file linking all characterization data to the specific synthesis parameters via a unique polymer identifier (e.g., using IUPAC BigSMILES notation).

Protocol 3.2: Automated Drug Release Kinetics Profiling

Objective: To generate standardized release kinetics data for polymer-drug conjugates or encapsulated formulations.

- Formulation: Prepare nanoparticles (e.g., by nanoprecipitation or emulsification) from the polymer library. Load with a model drug (e.g., Doxorubicin).

- Release Assay: Use a dialysis method in a 96-well format. Place formulation in dialysis membrane (MWCO 3.5-14 kDa). Immerse in release buffer (PBS, pH 7.4, with or without 0.1% w/v Tween 80). Maintain at 37°C with continuous agitation.

- Sampling & Analysis: At predetermined time points (0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24, 48, 72h), automatically sample from the external buffer using a robotic liquid handler. Quantify drug concentration via UV-Vis plate reader or HPLC.

- FAIR Data Capture: Record complete experimental conditions (buffer pH, ionic strength, sink conditions, temperature, agitation speed). Fit data to kinetic models (zero-order, first-order, Higuchi, Korsmeyer-Peppas). Store raw kinetic curves and fitted parameters together in a searchable database, tagged with the polymer identifier and environmental conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Polymer Informatics Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function & Role in FAIR Data Generation |

|---|---|

| Controlled Radical Polymerization Agents (e.g., RAFT, ATRP initiators) | Enables precise synthesis of polymers with tailored architecture and end-group functionality, creating a structured design of experiments (DoE) library. |

| Functional Monomers (e.g., N-isopropylacrylamide, caprolactone, aminoethyl methacrylate) | Provides chemical diversity (hydrophobicity, stimuli-responsiveness, bioactivity) for building structure-property relationship models. |

| Biocompatibility Assay Kits (e.g., MTT, LDH, Hemolysis) | Generates standardized, quantitative biological response data (cytotoxicity, hemocompatibility) for predictive toxicology models. |

| Reference Drug Compounds (e.g., Doxorubicin, Paclitaxel, siRNA) | Acts as standard probes for evaluating encapsulation efficiency, release kinetics, and therapeutic efficacy across polymer libraries. |

| Standardized Polymer Characterization Kits (e.g., for GPC, DSC, DLS) | Ensures consistency in measuring core properties (molecular weight, thermal transition, hydrodynamic size) across labs for data interoperability. |

| FAIR-Compliant Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) Software | The critical platform for capturing all experimental metadata in a structured, ontology-linked format at the point of generation. |

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Diagram 1: FAIR Data-Driven Polymer Discovery Cycle (97 chars)

Diagram 2: Endosomal Escape Pathway for Polymeric Carriers (77 chars)

Implementing the FAIR Data Schema: A Technical Guide

A practical FAIR implementation for polymer data requires a structured schema. Below is a simplified example of a JSON-LD object for a polymeric nanoparticle:

Key Actions for Researchers:

- Adopt Standard Identifiers: Use InChIKey for small molecules and develop institutional or community identifiers for polymers (e.g., based on BigSMILES).

- Leverage Ontologies: Tag data using existing ontologies (CHEBI for chemicals, SIO for measurements, PO for polymer-specific terms).

- Implement Minimal Metadata Standards: Define a core set of required metadata for every experiment (e.g., Polymer ID, synthesis method, characterization conditions).

- Utilize Repositories: Deposit datasets in domain-specific (e.g., NIH BioPolymer) or general (e.g., Zenodo, Figshare) repositories with rich metadata.

The systematic application of FAIR data principles is not merely a data management exercise but a foundational accelerator for discovery in polymer-based drug delivery, biomaterials, and formulations. By transforming isolated data points into an interconnected, machine-learning-ready knowledge graph, researchers can move from sequential trial-and-error to predictive, rationale-driven design. This whitepaper provides the methodological and technical framework to begin this transition, promising a future where new, life-saving polymeric therapies reach patients in a fraction of the current time.

This whitepaper explores the critical impact of non-FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) data on polymer informatics research, a specialized field crucial for advanced drug delivery systems, biomaterials, and pharmaceutical development. UnFAIR data practices directly contribute to failed reproducibility, wasted resources, and siloed innovation, creating significant financial and scientific costs for researchers and organizations.

The Quantifiable Cost of UnFAIR Data in Research

The following tables summarize the economic and scientific burdens identified through recent analyses of data management practices in materials science and life sciences research.

Table 1: Economic Impact of Poor Data Management

| Cost Factor | Estimated Range/Impact | Source Context |

|---|---|---|

| Time Spent Searching for Data | 30-50% of researcher time | Surveys in academic materials science labs |

| Cost of Irreproducible Research (Biomedical) | ~$28B USD annually | Estimated from published studies on preclinical irreproducibility |

| Data Re-creation Cost | 60-80% of original project cost | Case studies in polymer characterization |

| Grant Funding Wasted on Duplication | 10-25% | Analysis of public grant databases |

Table 2: Reproducibility Crisis Linked to Data Quality

| Issue | Frequency in Polymer/MatSci Literature | Primary FAIR Principle Violated |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Synthesis Protocols | 40-60% of papers | Reusable (R1) |

| Missing Characterization Raw Data | 70-85% of papers | Accessible (A1, A2) |

| Proprietary/Undisclosed Software | 30-40% of papers | Interoperable (I1) |

| Non-Standardized Nomenclature | >80% of papers | Interoperable (I2) |

Experimental Protocols for FAIR Data Generation in Polymer Informatics

To combat these issues, the following detailed methodologies are proposed as standards for generating FAIR-compliant data.

Protocol 1: FAIR Data Capture for Polymer Synthesis

Objective: To document a polymerization reaction ensuring all parameters are Findable and Reusable.

- Pre-experiment Registration:

- Register a Digital Object Identifier (DOI) for the planned experiment using a repository like Zenodo or Figshare before beginning lab work.

- Use a standardized electronic lab notebook (ELN) template with pre-defined fields for all variables.

- Material Documentation:

- Record all monomers, initiators, catalysts, and solvents using unique identifiers (e.g., InChIKey, CAS RN).

- Log batch numbers, purity certificates, and supplier information.

- Procedure Recording:

- Use controlled vocabulary (e.g., from CHMO - Chemical Methods Ontology).

- Record time-stamped parameters: temperature (±0.1 °C), stir rate (±1 rpm), pressure, reagent addition rates.

- Capture sequential photos/videos of reaction progression.

- Post-reaction Data Packaging:

- Compile all data (structured metadata, raw sensor logs, media files) into a single, compressed archive.

- Generate a

data_card.jsonfile adhering to the ISA (Investigation, Study, Assay) framework. - Deposit the archive in a domain-specific repository (e.g., NIH's ChemMLab) or a generalist repository, linking to the pre-registered DOI.

Protocol 2: FAIR Characterization Data Management

Objective: To ensure spectroscopic and chromatographic data are Accessible and Interoperable.

- Instrument Output Standardization:

- Save raw output files in open, non-proprietary formats (e.g.,

.csvfor chromatograms,.jcamp-dxfor NMR/FTIR). - Alongside raw data, include instrument calibration logs and standard sample data collected during the same session.

- Save raw output files in open, non-proprietary formats (e.g.,

- Metadata Attachment:

- Embed metadata using a standardized schema (e.g., PMD - Polymer Metadata Dictionary) within the data file or as a paired

.jsonfile. - Required metadata: Sample ID (linked to synthesis DOI), instrument model & software version, acquisition parameters, analyst name, date/time in ISO 8601 format.

- Embed metadata using a standardized schema (e.g., PMD - Polymer Metadata Dictionary) within the data file or as a paired

- Data Validation:

- Run automated checks using tools like

fair-checkerto ensure compliance with FAIR principles before publication. - Perform a basic reproducibility test by having a second team member attempt to load and interpret the raw data using open-source software (e.g., Python's

scipyfor chromatography).

- Run automated checks using tools like

Visualizing the FAIR Data Workflow and UnFAIR Consequences

FAIR Data Lifecycle in Research

Consequences of UnFAIR Data Practices

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Solutions for FAIR Polymer Informatics

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for FAIR Data Generation

| Item/Category | Function in FAIR Data Generation | Example/Standard |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) | Centralized, structured digital record of experiments, replacing paper. Enforces metadata capture. | Benchling, LabArchives, eLabFTW, openBIS |

| Persistent Identifier (PID) Services | Provide unique, permanent references for digital objects (data, code, samples). Critical for Findability. | Digital Object Identifier (DOI), Research Resource Identifier (RRID), Handle.net |

| Metadata Schemas & Ontologies | Controlled vocabularies and structured frameworks that make data Interoperable. | Polymer Metadata Dictionary (PMD), Chemical Methods Ontology (CHMO), EDAM-Bioimaging |

| Domain Repositories | Specialized, curated archives for specific data types that ensure long-term Access and preservation. | NIH's ChemMLab, PolyInfo (NIMS), PubChem, Zenodo (general) |

| Data Validation Tools | Software that checks data files and metadata for compliance with FAIR principles and community standards. | FAIR Data Stewardship Wizard, F-UJI, community-specific validators |

| Open File Format Converters | Tools to convert proprietary instrument data into open, machine-readable formats for Interoperability. | OpenChrom, BWF MetaEdit, Bio-Formats (for microscopy) |

| Containerization Software | Packages code, environment, and data dependencies together to guarantee computational Reproducibility. | Docker, Singularity/Apptainer |

Adopting FAIR data principles is not an administrative burden but a foundational requirement for robust, reproducible, and collaborative polymer informatics research. The protocols, tools, and practices outlined herein provide a concrete pathway to mitigate the high costs of irreproducibility and siloed science. By investing in FAIR data infrastructure and culture, the research community can accelerate the discovery of novel polymers for drug delivery, regenerative medicine, and sustainable materials, ensuring that every experiment contributes maximally to the collective scientific knowledge base.

The advancement of polymer informatics is critically dependent on the ability to discover, access, interoperate, and reuse (FAIR) data. Within this framework, three core technical components form the backbone of a functional data ecosystem: structured metadata, persistent and unique identifiers, and community-adopted standards. This guide details these components within the context of enabling FAIR data principles for polymer science, with a focus on applications in materials research and drug development (e.g., polymeric excipients, drug delivery systems).

Metadata Schemas for Polymeric Materials

Metadata provides the essential context for experimental data, making it interpretable and reusable. For polymers, metadata must capture the inherent complexity of macromolecular structures, synthesis, processing, and characterization.

Table 1: Core Metadata Categories for Polymeric Structures

| Category | Key Descriptors | Example / Standard | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monomeric Building Blocks | SMILES, InChI, molecular weight, functionality (e.g., f=2) | IUPAC International Chemical Identifier (InChI), PubChem CID | Defines the chemical identity of repeating units and end groups. |

| Polymer Characterization | Average molecular weights (Mn, Mw), dispersity (Đ), degree of polymerization (DP), sequence (random, block) | IUPAC Purple Book definitions, ISO 80004-1:2023 | Quantifies polydispersity and macromolecular size. |

| Topology & Architecture | Linear, branched, star, dendrimer, network, cyclic | IUPAC "Glossary of terms relating to polymers" | Describes the shape and connectivity of polymer chains. |

| Synthesis Protocol | Mechanism (ATRP, RAFT, ROMP), catalyst, temperature, time, solvent, monomer conversion | MIAPE (Minimum Information About a Polymer Experiment) emerging guidelines | Enables experimental reproducibility. |

| Property Data | Glass transition temp (Tg), melting temp (Tm), tensile strength, solubility parameter | ISO 11357 (Thermal analysis), ASTM D638 (Tensile properties) | Links structure to function and performance. |

Identifiers for Unique and Persistent Referencing

Identifiers are the cornerstone of data linkage. For polymers, the challenge lies in addressing chemical diversity and distributions.

- Chemical Identifiers for Repeating Units: Standard small-molecule identifiers (e.g., InChIKey, SMILES) are used for defined monomeric units and end-groups. They enable connection to vast chemical databases like PubChem.

- Polymer-Specific Identifiers: Generalized, non-linear representations are needed for complex structures.

- BigSMILES: An extension of SMILES designed for stochastic structures. It incorporates stochastic objects

($...$)to describe distributions in repeating units, branching, and chain lengths. - Self-Referred Encrypted String (SELFIES): A robust string-based representation gaining traction for machine learning applications due to its guaranteed validity.

- BigSMILES: An extension of SMILES designed for stochastic structures. It incorporates stochastic objects

- Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs): A DOI must be assigned to every published dataset, linking directly to a repository landing page with metadata and the data itself. This is non-negotiable for FAIR compliance.

- Dataset Internal IDs: Unique, immutable IDs (e.g., UUIDs) for each sample, experiment, and measurement within a laboratory information management system (LIMS).

Diagram Title: Identifier Ecosystem for FAIR Polymer Data

Standards and Nomenclature

Adherence to standards ensures interoperability across databases and research groups.

- IUPAC Nomenclature: The IUPAC "Purple Book" provides the authoritative source for naming polymers based on constitutional repeating units (CRUs).

- ISO Standards: ISO 80004 (Nanotechnology) and ISO 2078 (Textile glass) include definitions for polymers and composites. ISO/ASTM 52900 governs additive manufacturing data formats.

- File Format Standards:

- IUPAC Polymer Crystallography Data (PDBxt): An extension of the Protein Data Bank format for synthetic polymer crystallography.

- JCAMP-DX for Spectroscopy: Standard for exchanging spectral data (NMR, IR, Raman).

- CSD-Core Module (CCDC): For polymeric crystal structure data deposition.

- Minimum Information Standards: Initiatives like MIAPE-Polymers are under development to define the minimum data required to interpret and replicate a polymer synthesis experiment.

Experimental Protocol: Generating a FAIR Polymer Dataset

This protocol outlines the steps for a RAFT polymerization and characterization, ensuring FAIR data capture.

Objective: Synthesize and characterize poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM), a thermoresponsive polymer.

Materials & Reagents:

- N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAM) monomer

- 2-Cyano-2-propyl dodecyl trithiocarbonate (CPDT) as RAFT agent

- Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) as initiator

- Anhydrous 1,4-dioxane as solvent

- Deuterated chloroform (CDCl3) for NMR analysis

Procedure:

- Synthesis: In a Schlenk tube, combine NIPAM (1.0 g, 8.8 mmol), CPDT (14.5 mg, 0.044 mmol), and AIBN (1.2 mg, 0.0073 mmol) in 1,4-dioxane (2.5 mL). Degas via three freeze-pump-thaw cycles. React at 70°C for 4 hours. Terminate by cooling and exposure to air. Precipitate into cold diethyl ether, collect via filtration, and dry in vacuo.

- Characterization:

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (¹H NMR): Dissolve ~5 mg polymer in CDCl3. Calculate monomer conversion from vinyl proton integrals vs. polymer backbone integrals. Determine number-average molecular weight (Mn,NMR) from end-group analysis.

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): Use THF as eluent with PMMA standards. Determine Mn,SEC, Mw, and dispersity (Đ = Mw/ Mn).

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): Perform a heat-cool-heat cycle from -20°C to 150°C at 10°C/min under N2. Report the glass transition temperature (Tg) from the second heating scan.

FAIR Data Capture Workflow:

Diagram Title: FAIR Data Capture Workflow for Polymer Synthesis

Table 2: Example FAIR Data Output Table

| Sample ID | BigSMILES (Simplified) | Mn,theo (g/mol) | Mn,NMR (g/mol) | Mn,SEC (g/mol) | Đ | Tg (°C) | Data DOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNIPAM-1 | O=C(C(C)C)NCC{[$]CC(C(=O)N(C(C)C))C[$]}C |

22,500 | 24,100 | 28,400 | 1.12 | 135.5 | 10.1234/zenodo.xxxxxxx |

| PNIPAM-2 | O=C(C(C)C)NCC{[$]CC(C(=O)N(C(C)C))C[$]}C |

45,000 | 47,800 | 51,200 | 1.09 | 136.1 | 10.1234/zenodo.yyyyyyy |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for FAIR Polymer Informatics Research

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Provider |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Identifier Resolver | Converts between different chemical representations (SMILES, InChI, name). | NCI/CADD Chemical Identifier Resolver, PubChem API. |

| BigSMILES Line Notation Tool | Generates and validates BigSMILES strings for polymeric structures. | BigSMILES GitHub repository (bigsmiles). |

| FAIR Data Repository | Domain-specific repository for depositing and sharing polymer data with a DOI. | Zenodo (general), Polymer Genome (specialized). |

| Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) | Captures experimental metadata, procedures, and results in a structured, machine-readable format. | RSpace, LabArchives, SciNote. |

| Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) | Manages samples, workflows, and associated data at scale. | Labguru, Benchling. |

| Standard Thermoplastic Reference Materials | Calibrants for SEC, DSC, and other analytical techniques. | NIST Standard Reference Materials (e.g., SRM 706b for PS). |

| Polymer Property Database | Source of curated, historical data for validation and machine learning. | Polymer Properties Database (PPD), PoLyInfo. |

How to Implement FAIR Principles in Your Polymer Informatics Workflow: A Step-by-Step Guide

The advancement of polymer informatics is contingent upon the availability of high-quality, reusable data. This whitepaper, framed within a broader thesis on implementing FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data principles, addresses the critical first step: designing a data capture system for polymer synthesis and characterization. FAIR-compliant data capture is foundational for enabling machine-readable datasets, predictive modeling, and accelerating materials discovery in fields ranging from drug delivery to sustainable materials.

Core Principles and Data Structure

FAIR-compliant capture necessitates structured metadata and controlled vocabularies. Data must be recorded with globally unique and persistent identifiers (PIDs), rich contextual metadata, and in standardized formats.

Table 1: Essential Metadata Elements for FAIR Polymer Data Capture

| Metadata Category | Specific Element | Description & Standard | Example / Controlled Vocabulary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identification | Persistent Identifier (PID) | Globally unique ID for dataset. | DOI, handle, accession number |

| Provenance | Synthesis Protocol ID | Link to detailed, machine-readable method. | Protocol PID or URI |

| Provenance | Researcher ORCID | Unambiguously identifies contributor. | 0000-0002-1825-0097 |

| Data Description | Polymer Class | Type of polymer synthesized. | polyacrylate, polyester, polyolefin |

| Data Description | Monomer(s) | SMILES notation or InChIKey. | C=CC(=O)O, InChIKey=... |

| Data Description | Characterization Method | Technique used. | Size Exclusion Chromatography, NMR |

| Access | License | Clear usage rights. | CC BY 4.0, MIT |

| Interoperability | Ontology Terms | Links to community ontologies. | CHEBI:60027 (polyester), ChEBI Ontology |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain-Transfer (RAFT) Polymerization

- Objective: Synthesize poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) with controlled molecular weight and low dispersity (Ð).

- Materials: Methyl methacrylate (MMA, 99%), RAFT agent (cyanomethyl dodecyl trithiocarbonate, CDTC), initiator (AIBN, 98%), anhydrous toluene.

- Procedure:

- In a Schlenk flask, combine MMA (10.0 g, 100 mmol), CDTC (134 mg, 0.4 mmol), and AIBN (6.6 mg, 0.04 mmol) in toluene (20 mL).

- Degass the mixture via three freeze-pump-thaw cycles. Backfill with argon after the final cycle.

- Seal the flask and place it in an oil bath pre-heated to 70°C. React for 6 hours.

- Terminate polymerization by cooling in an ice bath and exposing to air.

- Purify by precipitation into cold methanol (10x volume). Filter and dry the polymer in vacuo at 40°C for 24h.

- FAIR Data Capture: Record exact masses, molar ratios, timestamps, temperature, and link to the detailed, versioned protocol (e.g., on protocols.io with PID).

Protocol B: Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Characterization

- Objective: Determine molecular weight distribution of synthesized polymer.

- Materials: Tetrahydrofuran (THP, HPLC grade), polystyrene standards, SEC columns (e.g., 3x PLgel Mixed-C).

- Procedure:

- Prepare polymer solution at a concentration of 2-3 mg/mL in THF. Filter through a 0.45 μm PTFE syringe filter.

- Calibrate the SEC system using a set of narrow dispersity polystyrene standards (e.g., 1kDa to 1000kDa).

- Inject 100 μL of sample. Use a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min at 30°C.

- Analyze chromatogram using dedicated software. Report number-average molecular weight (Mn), weight-average molecular weight (Mw), and dispersity (Đ = Mw/Mn).

- FAIR Data Capture: Report all instrument parameters (column IDs, flow rate, temperature), raw data files (in open format, e.g., .csv), calibration curve data, and processed results linked to the synthesis sample PID.

Visualizing the FAIR Data Capture Workflow

Diagram 1: FAIR data capture workflow for polymer research

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for FAIR Polymer Synthesis & Characterization

| Item | Function | FAIR-Compliant Capture Note |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) | Centralized, digital record of experiments, parameters, and observations. | Must export structured data (e.g., JSON-LD) with audit trail. |

| Monomer with Purity/Lot Number | Building block of the polymer chain. Critical for reproducibility. | Record vendor, CAS, lot number, purity, and link to chemical identifier (InChIKey). |

| Controlled Vocabulary Lists | Predefined lists for parameters (e.g., solvent names, technique names). | Ensures consistency and interoperability. Use community standards (IUPAC, NIST). |

| Persistent Identifier (PID) Service | Generates unique, long-term references for datasets and samples. | Integrate with DataCite DOI or similar for dataset registration upon completion. |

| Structured Data Templates | Pre-formatted forms within the ELN for specific experiment types (e.g., "RAFT Polymerization"). | Guides complete metadata capture and enforces required fields. |

| Open File Format Converters | Tools to convert proprietary instrument output (e.g., .ch, .spc) to open formats (.csv, .txt). | Preserves raw data in accessible, long-term readable formats. |

Key Quantitative Data Standards

Table 3: Minimum Required Quantitative Data for Polymer Characterization

| Characterization Technique | Key Parameters to Report | Standard Format / Units | Required Metadata |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Mn, Mw, Đ, elution volume | g/mol, dimensionless | Solvent, temperature, flow rate, column type, calibration standard PIDs |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Chemical shift (δ), integration ratio, coupling constant (J) | ppm, dimensionless, Hz | Solvent, nucleus (¹H/¹³C), frequency, referencing standard |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Glass Transition Temp (Tg), Melting Temp (Tm), Enthalpy (ΔH) | °C or K, J/g | Heating/cooling rate, atmosphere, sample mass |

| Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) | Wavenumber, transmittance/absorbance | cm⁻¹, % or a.u. | Scan resolution, number of scans, atmosphere (e.g., ATR) |

Implementing the systematic data capture design outlined here is the essential first step in building a FAIR ecosystem for polymer informatics. By embedding structured metadata, PIDs, and standardized protocols at the point of generation, researchers create a robust foundation for data sharing, re-analysis, and machine learning, ultimately accelerating the discovery and development of next-generation polymeric materials.

Within polymer informatics research, the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) principles provide a critical framework for managing complex, multi-dimensional data. Selecting and applying a robust metadata schema is the foundational step in operationalizing these principles. This guide details the technical process of evaluating and implementing schemas influenced by consortia like the Pistoia Alliance and the Earth Science Information Partners (ESIP), contextualized for polymer datasets encompassing chemical structures, processing conditions, and performance properties.

Core Metadata Schemas in Scientific Research

A metadata schema is a structured set of elements for describing a resource. For FAIR polymer data, the schema must capture both the chemical entity and its experimental context. The table below compares prominent frameworks.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Metadata Schema Frameworks

| Framework/Schema | Primary Origin | Key Strengths | Relevance to Polymer Informatics |

|---|---|---|---|

| ISA (Investigation, Study, Assay) | Life Sciences, Bioengineering | Hierarchical structure for experimental design; machine-actionable. | Excellent for capturing polymer synthesis (Investigation), formulation (Study), and characterization (Assay) workflows. |

| Schema.org (Bioschemas Extensions) | Web Consortium, Life Sciences | Enables rich snippet discovery on the web; broad adoption. | Useful for making polymer datasets discoverable via search engines; can describe chemicals, datasets, and creative works. |

| ESIP Science-on-Schema | Earth Sciences (ESIP) | Domain-agnostic, implements schema.org for scientific data; emphasizes provenance. | Adaptable for polymer processing data (e.g., environmental conditions); strong on data lineage and instruments. |

| Pistoia Alliance USDI Guidelines | Life Sciences R&D (Pistoia) | Focus on unifying data standards across drug discovery; promotes interoperability. | Directly applicable for polymeric drug delivery systems and biomaterials; aligns with industry data models. |

| DCAT (Data Catalog Vocabulary) | Data Catalogs | Standard for describing datasets in catalogs; supports linked data. | Essential for registering polymer datasets in institutional or community repositories. |

Technical Methodology for Schema Selection and Application

Experimental Protocol: Schema Needs Assessment

- Inventory Data Artifacts: Catalog all digital objects: chemical structures (SMILES, InChI), spectral files (FTIR, NMR), thermal analyses (DSC, TGA), mechanical test data, and simulation outputs.

- Map the Experimental Workflow: Document each step from monomer selection to property measurement. Identify all measurable parameters, instruments, and software used.

- Stakeholder Interview: Conduct structured interviews with researchers to identify key search queries (e.g., "find all polycarbonates with Tg > 150°C").

- Crosswalk Analysis: Create a spreadsheet mapping your identified data elements to potential elements in candidate schemas (e.g., ISA's

Assay Nameto ESIP'sobservedProperty).

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Hybrid Schema

Based on current best practices, a hybrid approach using schema.org as a top-layer with domain-specific extensions is recommended. The following protocol details implementation for a polymer tensile test dataset.

- Core Definition: Use

schema.org/Datasetas the root entity. - Chemical Entity Annotation: Use

schema.org/ChemicalSubstanceand link to authoritative identifiers (PubChem CID, ChemSpider ID). For polymers, includemolecularWeightandmonomericMolecularFormulaproperties. - Provenance Capture: Use the PROV-O ontology, integrated via

schema:prov. Describe the instrument (schema:Instrument), the processing software, and the person who performed the test. - Measurement Description: Use the ESIP Science-on-Schema pattern for

Observation. Define theobservedProperty(e.g., "tensile strength"), theresult(value with units), and relevant conditions (hasFeatureOfInterest). - Serialization: Serialize the metadata as JSON-LD, enabling both human-readability and machine-actionability.

Visualizing the Metadata Application Workflow

Diagram 1: Polymer Metadata Schema Implementation Workflow (97 chars)

Diagram 2: Hybrid FAIR Metadata Schema Structure (82 chars)

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for FAIR Polymer Metadata Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Category | Function in Metadata Process |

|---|---|---|

| ISAcreator Software | Metadata Authoring Tool | Enables creation of ISA-Tab formatted metadata, providing a user-friendly interface for capturing investigation-study-assay hierarchies. |

| FAIRifier | Data Transformation Tool | Assists in converting legacy data and metadata into FAIR-compliant formats, often using RDF and ontologies. |

| JSON-LD Playground | Validation & Debugging | Online tool to validate, frame, and debug JSON-LD metadata, ensuring correct linked data structure. |

| BioSchemas Generator | Schema Markup Generator | Guides users in generating structured schema.org markup for datasets and chemical entities. |

| Ontology Lookup Service (OLS) | Vocabulary Service | Provides access to biomedical ontologies (e.g., ChEBI, MS) for identifying standardized terms for polymer properties and processes. |

| FAIR Data Stewardship Wizard | Planning Tool | Interactive checklist to guide researchers through the FAIR data planning process, including metadata schema selection. |

| RO-Crate Metadata Specification | Packaging Standard | Provides a method to package research data with their metadata in a machine-readable manner, building on schema.org. |

Within the framework of FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) data principles for polymer informatics, the implementation of Persistent Identifiers (PIDs) is a critical technical step. PIDs provide unambiguous, long-term references to digital objects, such as datasets, chemical structures, and computational models, which are essential for reproducibility and data linkage in polymer science and drug development. This guide details the application of specific PID systems to polymers, their constituent monomers, and associated experimental or simulation datasets.

PID Systems in Polymer Informatics

Multiple PID systems exist, each with specific governance, resolution mechanisms, and typical use cases. The table below summarizes the key systems relevant to polymer research.

Table 1: Comparison of Key PID Systems for Polymer Informatics

| PID System | Administering Organization | Typical Resolution Target | Key Features for Polymer Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Object Identifier (DOI) | International DOI Foundation (IDF) | Published articles, datasets, software, specimens | Ubiquitous in publishing; used for datasets in repositories like Zenodo, Figshare. |

| InChI & InChIKey | IUPAC & NIST | Chemical substances | Algorithmic derivative of molecular structure; InChIKey is a 27-character hashed version for database indexing. |

| International Chemical Identifier (InChI) | |||

| Research Resource Identifier (RRID) | Resource Identification Initiative | Antibodies, model organisms, software tools, databases | Ensures precise citation of critical research resources in literature. |

| Handle System | DONA Foundation | Generic digital objects | Underlying technology for DOIs; used in some institutional repositories. |

| Archival Resource Key (ARK) | California Digital Library | Cultural heritage objects, data | Offers flexibility with optional metadata and promise of access. |

Assigning PIDs to Polymers and Monomers

Protocol: Generating InChI/InChIKey for Monomers and Defined Polymers

Objective: To create standard, reproducible chemical identifiers for monomeric units and chemically defined (e.g., sequence-defined) polymers.

Materials & Software:

- Chemical structure drawing/editing software (e.g., ChemDraw, Avogadro).

- InChI generation software (e.g., Open Babel, Chemoinformatics toolkits like RDKit, or online IUPAC validator).

- Standard IUPAC monomer naming reference.

Methodology:

- Structure Definition: Draw or generate a precise molecular structure file (e.g., SMILES, MOL file) for the monomer or defined oligomer.

- Standardization: Apply standard valency, neutralize charges where appropriate, and remove stereochemical information unless it is defined.

- InChI Generation: Use the chosen software/API to generate the standard InChI (version 1) and its corresponding InChIKey.

- Verification: Cross-check the generated InChIKey by submitting the structure to a public resolver (e.g., the NCI/CADD Chemical Identifier Resolver).

- Recording: Store the InChI, InChIKey, and the source structure file together as core metadata for the compound.

Limitations: InChI for polymers is most reliable for defined structures. For complex, polydisperse mixtures, a single InChI is not sufficient. Supplementary metadata (e.g, average DP, dispersity) must be linked via a dataset PID.

Protocol: Minting DOIs for Polymer Datasets

Objective: To obtain a persistent, citable DOI for a research dataset encompassing polymer characterization, synthesis details, or simulation results.

Materials & Software:

- Curated dataset following community standards (e.g., based on Polymer Schema).

- Selected data repository (e.g., Zenodo, Dryad, institutional repository, or discipline-specific repository like Materials Cloud).

- Repository user account.

Methodology:

- Dataset Preparation: Bundle all relevant files (synthesis protocols, characterization data - NMR, GPC, DSC - simulation input/output, analysis scripts). Include a

README.txtfile describing the project structure. - Metadata Completion: On the repository platform, complete all metadata fields:

- Creators: List all contributing researchers with ORCIDs.

- Title: Descriptive title of the dataset.

- Description: Abstract detailing the polymer system, experiments, and key results.

- Keywords: Include terms like "polymer," "monomer," specific polymer class, techniques used.

- Related Publications: Link to preprint or article DOI if applicable.

- License: Choose an open license (e.g., CC BY 4.0, MIT).

- Upload & Mint: Upload the dataset bundle. The repository will automatically mint and assign a new DOI upon publication of the dataset.

- Citation: Use the provided citation format (including the DOI) in any related publication.

Table 2: Essential Metadata for a FAIR Polymer Dataset

| Metadata Field | Example Entry | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Dataset Title | GPC, NMR, and DSC data for PMMA synthesized via ATRP from initiator XYZ |

Quickly identifies content. |

| Persistent Identifier | 10.5281/zenodo.1234567 |

Provides permanent reference. |

| Creator(s) with ORCID | Smith, Jane (0000-0001-2345-6789) |

Ensures author attribution. |

| Polymer Description | Poly(methyl methacrylate), Mn=52 kDa, Ð=1.12 |

Core chemical information. |

| Synthesis Protocol PID | RRID:SCR_123456 or link to protocol DOI |

Links to methodology. |

| Monomer InChIKey | VQCBHWLJZDBDQB-UHFFFAOYSA-N (Methyl methacrylate) |

Links to chemical building block. |

| Measurement Technique | Size Exclusion Chromatography |

Describes data origin. |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

Defines reuse terms. |

Integration into a FAIR Data Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between research objects and their corresponding PIDs within a polymer informatics project.

PID Integration in Polymer FAIR Workflow

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for PID Implementation

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose | Example / Provider |

|---|---|---|

| ORCID iD | A persistent identifier for researchers, disambiguating authors and linking their outputs. | https://orcid.org/ |

| IUPAC International Chemical Identifier (InChI) | The algorithm and software for generating standard, machine-readable chemical identifiers. | InChI Trust software, integrated into ChemDraw, RDKit. |

| Data Repository with DOI Minting | A platform to archive, publish, and obtain a DOI for research datasets. | Zenodo, Dryad, Figshare, Materials Cloud. |

| RRID Portal | A portal to search for and cite research resources (antibodies, cell lines, software) with an RRID. | https://scicrunch.org/resources |

| PID Graph Resolver | A service to discover connections between different PIDs (e.g., which datasets cite a specific chemical). | EOSC PID Graph, DataCite Commons. |

| Metadata Schema | A structured template to ensure complete and interoperable dataset description. | Polymer Schema, Dublin Core, Schema.org. |

| FAIR Data Management Plan Tool | A tool to guide the planning of PID usage and data stewardship throughout a project. | DMPTool, ARGOS. |

Within the broader thesis on implementing FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data principles for polymer informatics research, the adoption of standardized structural representation formats is a critical enabler. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, these standards transform ambiguous, textual descriptions into machine-readable, computable, and universally interpretable identifiers. This step is fundamental for creating interoperable databases, enabling large-scale virtual screening, and facilitating reproducible research in macromolecular and polymer-based therapeutic design.

Three primary formats have emerged as standards for representing chemical and biomolecular structures at different levels of complexity.

SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System)

SMILES is a line notation for describing the structure of small organic molecules and monomers using ASCII strings. It represents molecules as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, employing rules for hydrogen suppression, branching, cycles, and aromaticity.

Key Methodology for Generation:

- Select a starting atom.

- Perform a depth-first traversal of the molecular graph.

- Write atomic symbols (in brackets for non-standard valence, e.g.,

[Na+]). - Denote bonds: Single (

-), double (=), triple (#) (single bond and aromatic bonds are often implicit). - Indicate branching with parentheses

(). - Close rings by assigning numerical ring closure digits to the two connecting atoms.

- Specify aromaticity using lowercase atomic symbols (e.g.,

c1ccccc1for benzene).

InChI (International Chemical Identifier)

InChI is a non-proprietary, algorithmic identifier generated from structural information. It is designed to be a unique representation of the substance's core structure (excluding stereochemistry, isotopes) in its "standard" form, with layers adding more detail.

Experimental Protocol for InChIKey Generation (via software):

- Input: A connection table or SMILES string.

- Standardization: The algorithm normalizes the structure (e.g., tautomer normalization, metal bonding representation).

- Layer Generation: The software creates sequential layers:

- Main Layer: Formula and connectivity (no hydrogens).

- Charge Layer: Protonation and charge information.

- Hashing: The final InChI string is hashed using SHA-256 to produce a fixed-length (27-character) InChIKey (e.g.,

AAOVKJBEBIDNHE-UHFFFAOYSA-N). The first 14 characters represent the connectivity, the next 8 characters represent the stereochemistry, and the final character is a verification flag.

HELM (Hierarchical Editing Language for Macromolecules)

HELM is a standardized notation for complex biomolecules like peptides, oligonucleotides, and antibodies, which cannot be adequately described by SMILES or InChI. It represents macromolecules as sequences of monomers (natural or non-natural) with defined connectivity, modifications, and chemical groups.

Methodology for Constructing a HELM Notation:

- Define Monomers: Create a unique identifier for each monomeric unit in the polymer (e.g.,

Pfor phosphate backbone,[dR]for deoxyribose,A,C,G,Tfor nucleobases). - Create a Polymer Sequence: List monomers in order within parentheses:

RNA1{[dR](A)C.G.T}. - Define Connections: Specify connections between monomers using

-or$for backbone and branch linkages. - Add Annotations: Include attachments (e.g., dyes, peptides) and chemical modifications as nested notations.

Quantitative Comparison of Standardized Formats

Table 1: Core Characteristics and Applicability of Structural Representation Formats

| Feature | SMILES | InChI | HELM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Scope | Small organic molecules, monomers | Small organic molecules, up to medium polymers | Complex biomolecules (peptides, oligonucleotides, conjugates) |

| Representation Basis | Graph-based, human-readable | Algorithmic, layer-based | Hierarchical, sequence-based |

| Canonical/Unique | Can be canonicalized | Always canonical | Always canonical |

| Human Readability | Moderate (requires training) | Low (not designed for reading) | Low (machine-oriented) |

| Support for Polymers | Limited (single chain, R-group notation) | Limited (up to ~1,000 atoms, connectivity only) | Excellent (native support for sequences, branching) |

| Support for Stereochemistry | Yes (with specific symbols) | Yes (as a separate layer) | Yes (explicitly defined in monomer) |

| FAIR Alignment (Interoperability) | High for small molecules | Very High (open, non-proprietary, unique) | Very High (domain-specific standard) |

Table 2: Statistical Analysis of Database Coverage (Representative Data from Recent Search)

| Database | Total Compounds | % with SMILES | % with InChI | % with HELM | Primary Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PubChem | ~111 million | ~100% | ~100% | <0.1% | Small Molecules |

| ChEMBL | ~2.3 million | ~100% | ~100% | <0.1% | Bioactive Molecules |

| RCSB PDB | ~210,000 | ~95% (ligands) | ~95% (ligands) | ~5% (biopolymers) | Macromolecules |

| HELM Monomer Library | ~3,500 | 100% (per monomer) | 100% (per monomer) | 100% | Polymer Building Blocks |

Visualization of Logical Relationships

Figure 1: Standardized Formats Enable FAIR Data Interoperability

Figure 2: InChIKey Generation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software Tools and Libraries for Handling Standardized Formats

| Tool/Library | Primary Function | Key Application in Polymer Informatics |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit | Generation, canonicalization, and manipulation of SMILES; fingerprint generation for ML. |

| Open Babel | Chemical file format conversion | Batch conversion between SMILES, InChI, and other formats for data integration. |

| InChI Trust Software | Official InChI generator/parser | Creating and validating standard InChI identifiers for database submission. |

| HELM Toolkit (Pistoia Alliance) | Java/C# libraries for HELM | Assembling, editing, and rendering complex polymer and biomolecule notations. |

| CDK (Chemistry Development Kit) | Java library for chemo- and bioinformatics | Programmatic handling of SMILES/InChI and polymer descriptor calculation. |

| Peptide & Oligonucleotide Synthesizers | Automated solid-phase synthesis | Direct translation of HELM-defined sequences into synthesis instructions. |

Polymer informatics research generates complex, multi-dimensional data, encompassing chemical structures, synthesis protocols, characterization results (e.g., DSC, GPC, rheology), and performance metrics. Adherence to FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) is critical for accelerating discovery. This step moves beyond isolated databases to create integrated, semantically rich ecosystems. A FAIR data repository ensures persistent storage and access, while a Knowledge Graph (KG) provides the semantic layer for interconnection and intelligent reasoning, enabling the prediction of structure-property relationships for novel polymer-based materials, including drug delivery systems.

Architectural Framework: Repository and Knowledge Graph Symbiosis

The integrated system consists of two core, interlinked components:

- FAIR Data Repository: A versioned, queryable storage layer for raw and processed data. It assigns Persistent Identifiers (PIDs) and exposes metadata via standardized APIs.

- Polymer Informatics Knowledge Graph: A semantic network where data entities (e.g., Monomer, PolymerizationMethod, GlassTransitionTemperature) are represented as nodes, and their relationships (e.g., isSynthesizedFrom, hasProperty) are edges, defined using community ontologies.

Logical Workflow for Data Integration

Diagram Title: FAIR Data to Knowledge Graph Integration Pipeline

Core Methodology: Implementation Protocols

Protocol: Constructing a FAIR Polymer Data Repository

Technology Stack Selection:

- Storage: Use a hybrid approach. Store large binary files (e.g., chromatograms, spectra) in a structured object store (e.g., AWS S3, MinIO). Use a relational (PostgreSQL) or document (MongoDB) database for tabular and JSON metadata.

- PID Service: Integrate with a service like DataCite or ePIC to generate DOIs or Handles for each dataset.

- API: Implement a RESTful or GraphQL API, following the FAIR Data Point specification to expose dataset metadata.

Metadata Ingestion & Mapping:

- Define a core metadata profile extending schema.org and DCAT. Mandate fields: creator, publication date, license, and links to used ontologies.

- Use JSON-LD to serialize metadata, enabling inherent linkage to semantic web resources.

- Implement an ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) pipeline to automate the conversion of raw lab data (e.g., from Excel, CDF files) into the repository schema.

Protocol: Building the Polymer Informatics Knowledge Graph

Ontology Selection and Alignment:

- Chemical Entities: Use ChEBI (Chemical Entities of Biological Interest) for monomers and small molecules.

- Polymer-Specific Terms: Extend the emerging Polymer Database Ontology (PDO) or Polymer Ontology (POLY).

- General Properties: Use the SemanticScience Integrated Ontology (SIO) for concepts like

SIO:000628(has value) andSIO:000300(measurement value). - Alignment Tool: Use PROMPT or AgreementMakerLight to map local database schemata to these reference ontologies.

Knowledge Graph Population:

- Convert repository records to RDF triples using the RDF Mapping Language (RML). Define mapping rules that link a database column to an ontology class/property.

Example RML rule snippet mapping a database column

tg_valueto an RDF statement:Ingest the generated RDF into a triplestore (e.g., GraphDB, Blazegraph) or a labeled property graph database (e.g., Neo4j).

Quantitative Analysis: Impact of FAIR KG Integration

The value of integration is demonstrated through improved data utility and predictive capability.

Table 1: Comparison of Data Systems in Polymer Informatics

| Metric | Traditional File System | Standard Database | FAIR Repository + Knowledge Graph |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Discovery Time | High (Hours-Days) | Medium (Minutes-Hours) | Low (Seconds) |

| Interoperability | None (Proprietary Formats) | Limited (Within Schema) | High (Via RDF & Ontologies) |

| Reusability Without | Low (Requires Manual Curation) | Medium (Structured Query) | High (Machine-Actionable Links) |

| Complex Query Support | Not Possible | Limited (Joins) | Rich (Graph Traversal, SPARQL) |

| Example Query | "Find all copolymers with Tg > 100°C" | SQL query on single table. | SPARQL query joining synthesis, characterization, and ontology classes. |

Table 2: Performance of a KG-Enhanced Prediction Model for Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) Scenario: A graph neural network (GNN) model trained on a KG versus a traditional QSAR model.

| Model Type | Data Source | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) [°C] | R² | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional QSAR | Curated CSV file | 12.5 | 0.78 | Baseline |

| GNN on Knowledge Graph | Integrated FAIR KG | 8.2 | 0.89 | Learns from network topology and latent relationships |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Digital Tools for Building FAIR Repositories and Knowledge Graphs

| Item / Tool | Category | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| FAIR Data Point (FDP) Software | Repository Framework | Provides a reference implementation for a standard metadata catalog, ensuring API-level FAIRness. |

| CrystalBridge RML Mapper | Semantic Mapping Tool | Converts structured data (CSV, JSON, SQL) into RDF using declarative mapping files, critical for KG population. |

| GraphDB (Ontotext) | Triplestore / Graph Database | High-performance RDF database with reasoning support, used to store and query the knowledge graph. |

| Protégé | Ontology Editor | Allows creation, editing, and alignment of domain ontologies (e.g., extending PDO for local use). |

| SPARQL Endpoint | Query Interface | A HTTP service that allows applications to execute SPARQL queries against the knowledge graph. |

| DataCite API | PID Service | Programmatically mint and manage DOIs for datasets, fulfilling the F and A in FAIR. |

The integration of FAIR data repositories with semantically defined Knowledge Graphs represents the pinnacle of executable FAIR principles for polymer informatics. This infrastructure transforms fragmented data into an interconnected, machine-actionable asset. It directly supports advanced analytical techniques like graph-based machine learning, enabling researchers and drug developers to uncover novel structure-property relationships and accelerate the design of next-generation polymeric materials with unprecedented efficiency. This step is not merely technical but foundational to a collaborative, data-driven research paradigm.

Within the expanding field of polymer informatics, the adoption of FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) data principles is critical for accelerating the discovery of advanced materials, such as polymer-drug conjugates (PDCs). This case study details the practical implementation of FAIR within a high-throughput PDC screening project, serving as a foundational chapter for a broader thesis arguing that systematic FAIRification is a prerequisite for robust, data-driven polymer discovery.

The project aimed to screen a library of 150 distinct polymer-drug conjugates for efficacy against a specific cancer cell line. The primary FAIR-driven objective was to generate a fully annotated, machine-actionable dataset linking polymer chemical descriptors, conjugation chemistry, physicochemical properties, and biological activity.

Table 1: Core Project Metrics and FAIR Alignment

| Project Aspect | Quantity/Scope | FAIR Principle Addressed |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer-Drug Conjugate Library | 150 unique entities | Findable, Interoperable |

| Analytical Assays (HPLC, DLS, etc.) | 5 distinct protocols | Accessible, Reusable |

| Biological Screening Datapoints | 4500 (150 PDCs x 3 reps x 10 conc.) | Findable, Interoperable |

| Unique Metadata Fields | ~75 per PDC sample | Interoperable, Reusable |

| Target Data Repository | Institutional PolyInfoDB | Accessible, Reusable |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Synthesis of Amine-Reactive Polymer-Drug Conjugates

Objective: To covalently link a model drug (e.g., Doxorubicin via amine group) to a poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(lactic acid) (PEG-PLA) copolymer with terminal N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) esters.

Materials:

- NHS-PEG-PLA (5kDa-10kDa): Amphiphilic copolymer, NHS ester provides amine-reactive site.

- Doxorubicin HCl: Chemotherapeutic drug, contains primary amine for conjugation.

- Dimethylformamide (DMF), anhydrous: Reaction solvent.

- N,N-Diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA): Base, catalyzes conjugation.

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4: Quenching and purification buffer.

Procedure:

- Dissolve 50 mg of NHS-PEG-PLA in 5 mL of anhydrous DMF under nitrogen.

- Add 1.2 molar equivalents of Doxorubicin HCl and 2 equivalents of DIPEA.

- React for 12 hours at room temperature, protected from light.

- Quench reaction by adding 50 mL of PBS (pH 7.4).

- Purify conjugate by dialysis (MWCO 3.5 kDa) against PBS for 48 hours.

- Lyophilize and store at -20°C. Confirm conjugation via

¹H NMRandHPLC.

Protocol: High-Throughput Cytotoxicity Screening

Objective: To determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) of each PDC against MCF-7 breast cancer cells.

Materials:

- MCF-7 Cells: Human breast adenocarcinoma cell line.

- CellTiter-Glo 2.0 Assay: Luminescent assay quantifying cellular ATP as a viability readout.

- 96-well White-walled Assay Plates: For cell culture and luminescent signal measurement.

- Automated Liquid Handler: For precise serial dilution and compound dispensing.

Procedure:

- Seed MCF-7 cells at 5,000 cells/well in 90 µL of growth medium. Incubate for 24 h.

- Prepare 10-point, 1:2 serial dilutions of each PDC and free drug control in assay medium.

- Using an automated handler, add 10 µL of each dilution to triplicate wells (final volume 100 µL).

- Incubate cells with compounds for 72 hours.

- Equilibrate plates to room temperature for 30 minutes. Add 50 µL of CellTiter-Glo 2.0 reagent per well.

- Shake for 2 minutes, incubate for 10 minutes, and record luminescence on a plate reader.

- Calculate % viability relative to untreated controls and derive IC₅₀ using a 4-parameter logistic fit.

FAIR Implementation Framework

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PDC Screening

| Item | Function in PDC Research |

|---|---|

| Functionalized Polymers (e.g., NHS-PEG-PLA) | Core scaffold; defines conjugate's pharmacokinetics and drug loading capacity. |