DFT vs. Coupled-Cluster Theory: Accuracy and Application in Polymer Prediction for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between Density Functional Theory (DFT) and the gold-standard Coupled-Cluster (CC) method for predicting polymer properties critical to biomedical applications, such as drug delivery.

DFT vs. Coupled-Cluster Theory: Accuracy and Application in Polymer Prediction for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between Density Functional Theory (DFT) and the gold-standard Coupled-Cluster (CC) method for predicting polymer properties critical to biomedical applications, such as drug delivery. We explore the foundational principles of both methods, detail their practical application in predicting key properties like band gaps and drug-polymer interactions, and address common challenges and optimization strategies. By synthesizing recent benchmarking studies and the emergence of machine-learning models that bridge the accuracy-cost gap, this review offers researchers a validated framework for selecting and applying computational tools to accelerate the design of advanced polymer-based systems.

Understanding the Quantum Chemistry Toolkit: From DFT to the Coupled-Cluster Gold Standard

The Fundamental Principles of Density Functional Theory (DFT)

Density Functional Theory (DFT) stands as one of the most pivotal computational quantum mechanical modeling methods in modern physics, chemistry, and materials science. This first-principles approach investigates the electronic structure of many-body systems, primarily focusing on atoms, molecules, and condensed phases. According to its core principle, all properties of a many-electron system can be uniquely determined by functionals of the spatially dependent electron density—a revolutionary concept that reduces the complex many-body problem with 3N spatial coordinates to a tractable problem dealing with just three spatial coordinates. The theoretical foundation of DFT rests upon the pioneering Hohenberg-Kohn theorems, which demonstrate that the ground-state electron density uniquely determines the external potential and thus all properties of the system, and that a universal functional for the energy exists where the ground-state density minimizes this functional [1].

The practical implementation of DFT primarily occurs through the Kohn-Sham equations, which map the problem of interacting electrons onto a fictitious system of non-interacting electrons moving in an effective potential. This potential includes the external potential, the classical Coulomb interaction, and the exchange-correlation potential—which encompasses all quantum mechanical interactions and remains the central challenge in DFT development. The versatility and computational efficiency of DFT have made it an indispensable tool across numerous scientific domains, from drug development to polymer science and renewable energy research, where it provides atomic-level insights that complement and often guide experimental efforts [1] [2].

Theoretical Framework: From Quantum Mechanics to Practical Computation

The Hohenberg-Kohn Theorems and Kohn-Sham Equations

The mathematical foundation of DFT rests on two fundamental theorems established by Hohenberg and Kohn. The first theorem proves that the ground-state electron density uniquely determines the external potential (to within an additive constant) and thus all properties of the system. The second theorem provides the variational principle that the correct ground-state density minimizes the total energy functional E[n(r)]. These theorems transform the intractable many-electron Schrödinger equation into a much more manageable form focused on the electron density rather than the many-body wavefunction [1].

The Kohn-Sham approach, which later earned Walter Kohn the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, introduced orbitals for non-interacting electrons that reproduce the same density as the true interacting system. The Kohn-Sham equations take the form:

$$ \left[-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\nabla^2 + V{ext}(\mathbf{r}) + VH(\mathbf{r}) + V{XC}(\mathbf{r})\right]\psii(\mathbf{r}) = \epsiloni\psii(\mathbf{r}) $$

where the terms represent the kinetic energy operator, external potential, Hartree potential (electron-electron repulsion), and exchange-correlation potential, respectively. The electron density is constructed from the Kohn-Sham orbitals: (n(\mathbf{r}) = \sum{i=1}^N |\psii(\mathbf{r})|^2). The critical advantage lies in dealing with a system of non-interacting electrons, making computations feasible for complex systems, though all the challenges are now embedded in the exchange-correlation functional (V_{XC}(\mathbf{r})) [1].

Exchange-Correlation Functionals: The Key to Accuracy

The accuracy of DFT calculations hinges entirely on the approximation used for the exchange-correlation functional. The hierarchy of functionals has evolved significantly from the initial Local Density Approximation (LDA) to more sophisticated approaches:

Local Density Approximation (LDA): Assumes the exchange-correlation energy per electron at a point equals that of a uniform electron gas with the same density. LDA generally overestimates binding energies and yields over-contracted lattice parameters [3].

Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA): Incorporates the local density gradient to account for inhomogeneities, improving accuracy for molecular geometries and cohesive energies. The Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional is among the most widely used GGA functionals [3].

Meta-GGA and Hybrid Functionals: Include exact exchange from Hartree-Fock theory (e.g., B3LYP) or kinetic energy density dependence, offering improved accuracy for band gaps, reaction barriers, and molecular properties, albeit at increased computational cost [4] [5].

The selection of appropriate functionals depends critically on the system and properties under investigation, with different functionals exhibiting distinct strengths and limitations for various chemical environments and material classes.

DFT Versus Coupled-Cluster Theory: A Comparative Analysis

Theoretical Foundation and Computational Scaling

While both DFT and coupled-cluster (CC) theory aim to solve the electronic structure problem, they diverge fundamentally in their theoretical approaches and computational characteristics. Coupled-cluster theory is a wavefunction-based method that systematically accounts for electron correlation through exponential cluster operators, typically including singles, doubles, and sometimes triples excitations (CCSD, CCSD(T)). In principle, CC theory with full inclusion of excitations and a complete basis set provides an exact solution to the Schrödinger equation, making it potentially more accurate than DFT [6].

However, this accuracy comes with a staggering computational cost. The computational scaling of CCSD grows as O(N⁶), with CCSD(T) reaching O(N⁷), where N represents the system size. This prohibitive scaling limits practical CC calculations to systems containing approximately 10-50 atoms, effectively precluding its application to large polymer systems or extended materials without significant approximations [6].

In contrast, DFT with local and semi-local functionals scales as O(N³), with hybrid functionals typically scaling as O(N⁴). This favorable scaling enables DFT to handle systems containing hundreds to thousands of atoms, making it applicable to realistic polymer segments, surface catalysis, and complex materials that remain far beyond the reach of CC methods [6] [2].

Table 1: Theoretical and Practical Comparison Between DFT and Coupled-Cluster Methods

| Aspect | Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Coupled-Cluster Theory |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Foundation | Electron density functionals | Wavefunction expansion with exponential ansatz |

| Systematic Improvability | No systematic approach; functional development empirical | Systematic improvement through excitation levels (CCSD, CCSD(T), CCSDT, etc.) |

| Computational Scaling | O(N³) to O(N⁴) | O(N⁶) to O(N⁷) or higher |

| Practical System Size | Hundreds to thousands of atoms | Typically 10-50 atoms |

| Periodic Systems | Excellent support with plane-wave basis sets | Challenging; active research area |

| Treatment of Dispersion | Requires empirical corrections or non-local functionals | Naturally included in correlation treatment |

| Typical Polymer Applications | Full oligomer segments, structural properties, band gaps | Very small model systems, benchmark accuracy |

Accuracy Comparison for Molecular and Materials Properties

Quantitative comparisons between DFT and coupled-cluster reveal a complex accuracy landscape that varies significantly across different chemical properties and systems. For polymer research specifically, the critical properties include geometric parameters, reaction energies, electronic band gaps, and intermolecular interactions.

Table 2: Accuracy Comparison for Key Properties in Polymer Science

| Property | DFT Performance | Coupled-Cluster Performance | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ground-State Geometries | Generally good with GGA (∼0.01-0.03 Å bond lengths) | Excellent (∼0.001-0.01 Å) | CC provides benchmark accuracy |

| Reaction Barriers | Variable; often underestimated with GGA, improved with hybrids | Excellent with CCSD(T) | CC considered "gold standard" for thermochemistry |

| Band Gaps | Systematic underestimation (10-50% error) | Not applicable to extended systems | GW methods often superior for extended systems |

| Intermolecular Interactions | Poor with LDA/GGA; requires dispersion corrections | Excellent for non-covalent interactions | CCSD(T) near chemical accuracy for van der Waals |

| Polymer Segment Stability | Good trends with appropriate functionals | Limited to very small models | DFT practical for oligomer series [4] |

| Computational Cost for 50-atom system | Minutes to hours | Days to weeks | Hardware-dependent but relative scaling consistent |

For polymer research, the limitations of CC theory become particularly pronounced. As noted in the search results, "coupled-cluster is only used for small molecular systems. Periodic systems tend to be too large to be tractable by CC" [6]. This fundamental limitation restricts CC to small model systems in polymer science, whereas DFT can handle realistic oligomer segments of practical interest.

DFT Methodologies for Polymer Research: Protocols and Applications

Standard Computational Protocol for Polymer Properties

The application of DFT to polymer systems follows well-established computational protocols that balance accuracy with feasibility. A typical workflow for investigating polymer electronic properties involves:

Step 1: Molecular Structure Preparation

- Construct initial oligomer structures using chemical modeling software

- For conjugated polymers, typical oligomer lengths range from 3-8 repeat units to approximate polymer behavior [7]

- Apply alkyl side chain truncation to reduce computational cost while preserving electronic structure [7]

Step 2: Geometry Optimization

- Employ DFT functionals such as B3LYP, ωB97XD, or PBE with appropriate basis sets (e.g., 6-311++G(d,p) for molecular systems) [4] [5]

- Perform structural relaxation until forces converge below 0.001 eV/Å

- For periodic systems, optimize both atomic positions and lattice parameters

Step 3: Electronic Property Calculation

- Compute HOMO-LUMO energies from optimized structures

- Calculate molecular electrostatic potentials and natural bond orbitals

- For band structures of periodic systems, perform k-point sampling along high-symmetry directions

Step 4: Property Analysis

- Derive global reactivity descriptors: electronegativity ( \chi = \frac{(E{HOMO} + E{LUMO})}{2} ), hardness ( \eta = E{LUMO} - E{HOMO} )

- Predict optical spectra using Time-Dependent DFT (TD-DFT)

- Calculate vibrational frequencies for IR and Raman spectra [4]

This methodology has been successfully applied to polymer components for concrete impregnation, where DFT calculations at the B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level provided insights into structural, electronic, and vibrational properties of styrene, divinyl benzene, and their oligomers [4].

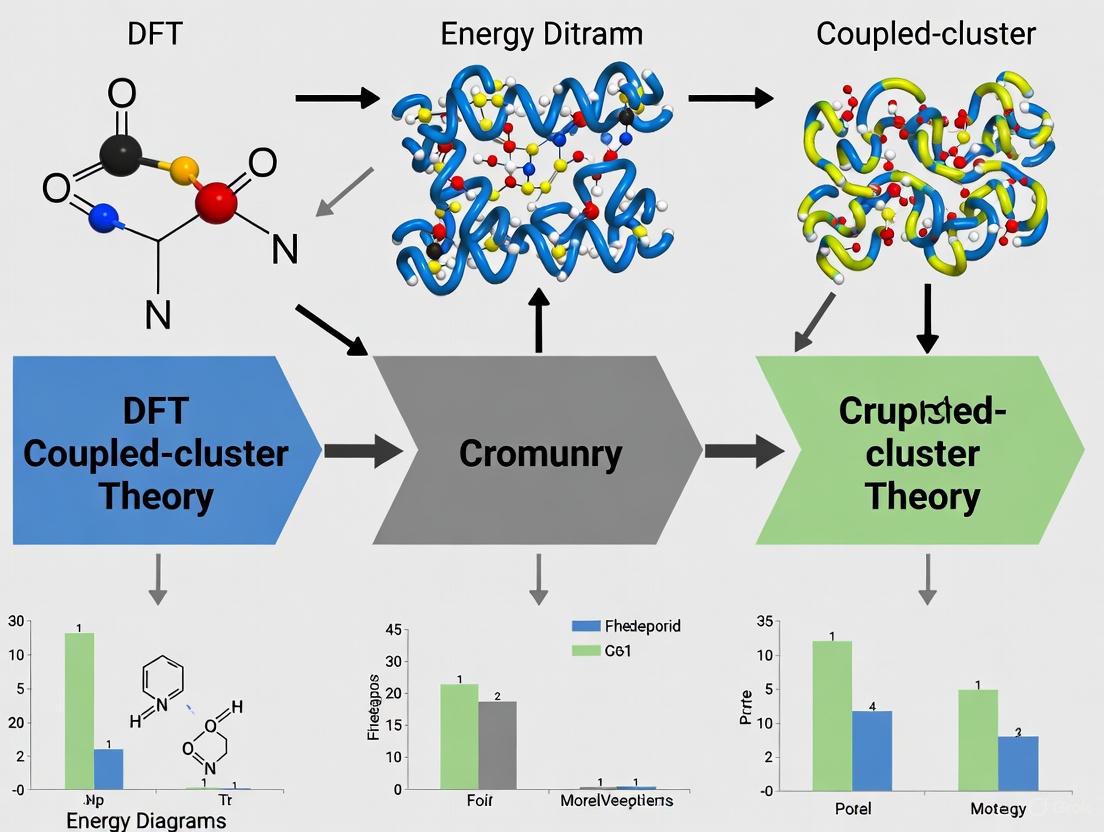

Diagram 1: DFT Computational Workflow for Polymer Studies. This standardized protocol ensures consistent and reproducible results for polymer electronic properties.

Advanced Integration: DFT with Machine Learning

Recent advances have demonstrated the powerful synergy between DFT calculations and machine learning (ML) for polymer property prediction. Liu et al. (2025) developed an integrated DFT-ML approach for predicting optical band gaps of conjugated polymers, using oligomer structures with extended backbones and truncated alkyl chains to effectively capture polymer electronic properties [7]. Their methodology achieved a remarkable R² value of 0.77 and MAE of 0.065 eV for predicting experimental band gaps, falling within experimental error margins.

The research established that "modified oligomers effectively capture the electronic properties of CPs, significantly improving the correlation between the DFT-calculated HOMO–LUMO gap and experimental gap (R² = 0.51) compared to the unmodified side-chain-containing monomers (R² = 0.15)" [7]. This demonstrates how thoughtfully designed DFT calculations can provide high-quality input features for ML models, enabling accurate prediction of experimental polymer properties.

Similar success was reported in Nature Communications (2025), where researchers discovered that "the calculated binding energy of supramolecular fragments correlates linearly with the mechanical properties of polyurethane elastomers," suggesting that small molecule DFT calculations can offer efficient prediction of polymer performance [8]. This approach enabled the design of elastomers with toughness of 1.1 GJ m⁻³, demonstrating how DFT-guided design can lead to exceptional material performance.

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools for Polymer DFT

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Polymer DFT Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Software/Package | Primary Function | Application in Polymer Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Packages | Gaussian 09/16, PSI4 | DFT energy, optimization, and property calculations | Molecular oligomer calculations; electronic structure analysis [4] [5] |

| Periodic DFT Codes | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO | Solid-state calculations with periodic boundary conditions | Polymer crystals; band structure of conductive polymers |

| Basis Sets | 6-311++G(d,p), def2-TZVP, LanL2DZ | Atomic orbital basis functions | Flexibility for different elements; polarization/diffuse functions for accuracy [4] [5] |

| Exchange-Correlation Functionals | B3LYP, ωB97XD, PBE, M06-2X | Approximate electron exchange-correlation | Tuned for specific properties: B3LYP for general purpose, ωB97XD for dispersion [5] |

| Visualization & Analysis | GaussView, ChemCraft, VESTA | Molecular structure visualization and analysis | Orbitals, electrostatic potentials, vibrational modes [4] |

| Machine Learning Integration | RDKit, Scikit-learn | Descriptor generation and model training | Bridge DFT calculations with experimental properties [7] |

Limitations and Future Perspectives

Despite its widespread success, DFT faces several fundamental limitations that researchers must acknowledge. The theory inherently struggles with van der Waals interactions, charge transfer excitations, strongly correlated systems, and accurate band gap prediction [1]. For polymers, this can manifest as inaccurate prediction of intermolecular packing or charge transport properties. Recent research shows that "DFT-computations have significant discrepancy against experimental observations," with formation energy MAEs of 0.078-0.095 eV/atom compared to experimental values [9].

The integration of machine learning with DFT represents a promising direction to overcome these limitations. As demonstrated by Jha et al., AI models can actually outperform standalone DFT computations, predicting formation energy with MAE of 0.064 eV/atom compared to experimental values, significantly better than DFT alone (>0.076 eV/atom) [9]. This suggests a future where DFT calculations provide high-quality training data for ML models that can achieve experimental-level accuracy.

For polymer research specifically, the combination of DFT with machine learning enables the development of models that can rapidly screen potential polymer structures with optimized properties. Aljaafreh (2025) demonstrated such an approach for photovoltaic polymers, where "extra gradient boosting regressor and random forest regressor are the best-performing models among all the tested ML models, with R² values of 0.96-0.98" for predicting optical density [5]. This integrated computational strategy accelerates the design cycle for advanced polymeric materials while reducing reliance on costly experimental trial-and-error.

In conclusion, while coupled-cluster theory remains the gold standard for accuracy in quantum chemistry, its prohibitive computational cost limits applications to small model systems in polymer science. DFT, despite its known limitations, provides the best balance of accuracy and feasibility for practical polymer research, particularly when enhanced with machine learning approaches. As computational power increases and methodological developments continue, the synergy between first-principles calculations and data-driven modeling will likely further narrow the gap between computational prediction and experimental reality in polymer science and materials design.

In computational chemistry, the accurate prediction of molecular and material properties represents a cornerstone for scientific advancement across diverse fields, including polymer science, drug development, and materials engineering. The ongoing research discourse often centers on the comparison between two predominant electronic structure methods: Density Functional Theory (DFT) and Coupled-Cluster Theory. Within this landscape, the Coupled-Cluster with Single, Double, and Perturbative Triple Excitations (CCSD(T)) method has emerged as the uncontested "gold standard" for quantum chemical calculations due to its exceptional accuracy and systematic improvability [10] [11]. This designation stems from its demonstrated ability to deliver results "as trustworthy as those currently obtainable from experiments" [11], establishing it as a critical benchmark for evaluating the performance of more computationally efficient methods, including various DFT functionals.

The significance of CCSD(T) is particularly pronounced in the context of polymer prediction research, where understanding catalytic mechanisms, bond dissociation energies, and redox properties at a quantum mechanical level informs the design of novel materials [12]. For transition-metal complexes relevant to polymerization catalysis, such as zirconocene catalysts, CCSD(T) provides reference-quality data that can identify discrepancies in both experimental measurements and less sophisticated computational methods [12]. This review provides a comprehensive overview of the CCSD(T) methodology, its performance relative to alternative quantum chemical approaches, and its evolving role in addressing complex challenges in computational chemistry and materials science.

Theoretical Foundations of Coupled-Cluster Theory

The Exponential Ansatz

Coupled-cluster theory is a sophisticated ab initio quantum chemistry method that builds upon the fundamental Hartree-Fock molecular orbital approach by systematically incorporating electron correlation effects. The core of the method lies in its exponential wavefunction ansatz [10]:

- |Ψ₀⟩: The exact many-electron wavefunction.

- |Φ₀⟩: The reference Slater determinant, typically the Hartree-Fock wavefunction.

- T: The cluster operator, which excites electrons from occupied to unoccupied orbitals.

This elegant formulation differs fundamentally from configuration interaction (CI) approaches, as it ensures size extensivity, meaning the energy scales correctly with the number of particles—a critical property for studying molecular systems of varying sizes [10].

The cluster operator T is expressed as a sum of excitation operators of increasing complexity:

- T₁: Produces all single excitations.

- T₂: Produces all double excitations.

- T₃: Produces all triple excitations.

In practice, the expansion must be truncated to make computations feasible. The CCSD method includes T₁ and T₂ explicitly, while the CCSD(T) method adds a perturbative treatment of triple excitations, dramatically improving accuracy without the prohibitive computational cost of full CCSDT [10]. The computational demands of these methods are substantial: CCSD scales with the 6th power of the system size, while CCSD(T) scales with the 7th power, effectively limiting their application to small-to-medium-sized molecules in conventional implementations [13] [11].

CCSD(T) as the Gold Standard: Performance and Validation

Benchmarking Against Experimental Data

The reputation of CCSD(T) as the gold standard rests on extensive validation against experimental measurements across diverse molecular systems and properties. The following table summarizes its performance for key molecular properties:

Table 1: Accuracy of CCSD(T) for Various Molecular Properties

| Property | System Type | Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Dissociation Enthalpies (BDEs) | Zirconocene polymerization catalysts | Identifies discrepancies in experimental values; provides most accurate values | [12] |

| Interaction/Binding Energies | Group I metal-nucleic acid complexes | Reference values for benchmarking DFT methods | [14] |

| Formation Enthalpies | C-, H-, O-, N-containing closed-shell compounds | Uncertainty of ~3 kJ·mol⁻¹, competitive with calorimetry | [15] |

| Dipole Moments | Diatomic molecules | Generally accurate, though some unexplained discrepancies with experiment | [16] |

| Intermolecular Interactions | Ionic liquids | Chemical accuracy (≤4 kJ·mol⁻¹) with appropriate settings | [17] |

Comparative Performance Against DFT

Density Functional Theory remains the workhorse of computational chemistry due to its favorable cost-accuracy balance, but its performance is highly dependent on the choice of exchange-correlation functional. CCSD(T) serves as the critical benchmark for evaluating DFT performance:

Table 2: CCSD(T) versus DFT Performance Benchmarks

| Study Context | Best-Performing DFT Methods | Deviation from CCSD(T) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group I metal-nucleic acid complexes | mPW2-PLYP (double-hybrid), ωB97M-V | ≤1.6% MPE; <1.0 kcal/mol MUE | [14] |

| Zirconocene catalysts | Not specified (multiple tested) | Large deviations for BDEs; excellent for redox potentials | [12] |

| General molecular properties | Varies by functional (B3LYP common) | CCSD(T) significantly more accurate, especially for reactive species | [13] |

For the particularly challenging case of polymer catalysis, while DFT excellently reproduces redox potentials and ionization potentials for zirconocene catalysts, it shows "relatively large deviations" for bond dissociation enthalpies compared to CCSD(T) references [12]. This highlights the critical role of CCSD(T) in identifying potential shortcomings in DFT approaches for specific chemical properties.

Computational Methodologies and Protocols

Standard CCSD(T) Implementation

A typical CCSD(T) calculation follows a well-defined protocol, often implemented in quantum chemistry packages like PySCF [18]:

- Geometry Optimization: Initial molecular structure preparation (often at lower levels of theory like DFT).

- Hartree-Fock Calculation: Solution of the reference wavefunction

mf = scf.HF(mol).run(). - CCSD Correlation Energy: Calculation of the coupled-cluster singles and doubles energy

mycc = cc.CCSD(mf).run(). - Perturbative Triples Correction: Evaluation of the (T) correction

et = mycc.ccsd_t(). - Total Energy Summation: Final CCSD(T) energy = CCSD energy + (T) correction.

This workflow provides the foundation for computing various molecular properties, including analytical gradients, excitation energies (via EOM-CCSD), and reduced density matrices [18].

Local Correlation Approximations: The DLPNO-CCSD(T) Advance

A significant breakthrough in applying CCSD(T) to larger systems came with the development of local correlation approximations, particularly the Domain-based Local Pair Natural Orbital (DLPNO) approach. This method dramatically reduces computational cost while maintaining high accuracy [17]:

- Principle: Exploits the local nature of electron correlation by projecting orbitals into local domains.

- Efficiency: Enables application to systems with hundreds of atoms.

- Accuracy: Can achieve "chemical accuracy" (≤4 kJ·mol⁻¹) or even "spectroscopic accuracy" (1 kJ·mol⁻¹) with appropriate settings [17].

- Validation: Successfully applied to ionic liquids, formation enthalpies, and intermolecular interactions [17] [15].

Table 3: DLPNO-CCSD(T) Performance for Different Accuracy Targets

| Accuracy Target | Parameter Settings | Computational Cost | Recommended For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Accuracy (<4 kJ/mol) | Standard (NormalPNO) | Baseline | Screening, large systems |

| Spectroscopic Accuracy (~1 kJ/mol) | TightPNO, iterative triple excitations | ~2.5x higher | Hydrogen-bonded systems, halides, final reporting |

The following diagram illustrates a typical CCSD(T) application workflow in polymer catalyst research, integrating both conventional and DLPNO approaches:

Table 4: Key Computational Tools and Concepts for CCSD(T) Calculations

| Tool/Concept | Category | Function/Purpose | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| PySCF | Software Package | Python-based quantum chemistry with efficient CC implementations | Supports CCSD, CCSD(T), EOM-CCSD [18] |

| DLPNO Approximation | Algorithm | Reduces computational cost for large systems | Enables CCSD(T) on ionic liquids [17] |

| Frozen Core Approximation | Computational Technique | Freezes core electrons to reduce cost | frozen=[0,1] in PySCF [18] |

| Basis Sets | Mathematical Basis | Set of functions to represent molecular orbitals | cc-pVDZ, cc-pVTZ, 6-31G(2df,p) |

| EOM-CCSD | Method Extension | Calculates excited states, ionization potentials | mycc.eeccsd(nroots=3) [18] |

| Complete Basis Set (CBS) Extrapolation | Technique | Estimates infinite basis set limit | Combined with CCSD(T) for accuracy [14] |

Emerging Frontiers and Future Directions

Integration with Machine Learning

Recent pioneering work by MIT researchers demonstrates how machine learning can dramatically accelerate CCSD(T) calculations. Their "Multi-task Electronic Hamiltonian network" (MEHnet) achieves CCSD(T)-level accuracy for molecules thousands of times faster than conventional computations [11]. This approach:

- Extracts multiple electronic properties from a single model (dipole/quadrupole moments, polarizability, excitation gaps).

- Generalizes from small molecules to larger systems, potentially handling "thousands of atoms".

- Could eventually enable CCSD(T)-level accuracy across the periodic table at DFT cost [11].

Expanding Applications in Materials Science

The enhanced accessibility of CCSD(T) through methods like DLPNO and machine learning is opening new frontiers:

- Polymer Design: Accurate prediction of catalyst performance and bond interactions [12].

- Energy Materials: Development of improved batteries through understanding of metal-ion interactions [14] [11].

- Pharmaceutical Design: Precise characterization of drug-receptor interactions and spectroscopic properties.

- Environmental Science: Sensing of metal contaminants via nucleic acid sensors [14].

Coupled-cluster theory, particularly the CCSD(T) method, maintains its position as the gold standard of computational chemistry, providing benchmark-quality data essential for validating more approximate methods like DFT. While its computational demands historically limited applications to small systems, advances in local correlation techniques (DLPNO) and machine-learning acceleration are rapidly expanding its reach to biologically and materially relevant systems. In the context of polymer prediction research and beyond, CCSD(T) serves as the critical anchor point in the computational chemist's toolbox, enabling the precise prediction of molecular properties that guide the design of novel materials, catalysts, and pharmaceuticals. As these methodological advances mature, CCSD(T)-level accuracy may become routinely accessible for systems across chemistry and materials science, fundamentally transforming our ability to predict and design molecular behavior from first principles.

The rational design of polymers for advanced drug delivery systems (DDS) has been revolutionized by computational chemistry techniques. These tools enable researchers to predict key polymer properties at the molecular level before synthesis, significantly accelerating development cycles. Within this field, a critical methodological comparison exists between the established Density Functional Theory (DFT) and the high-accuracy coupled-cluster theory, particularly CCSD(T). DFT has been widely adopted for studying polymer-drug interactions due to its favorable balance between computational cost and accuracy for large systems. Meanwhile, CCSD(T) is recognized as the "gold standard" of quantum chemistry for its superior accuracy, though traditionally limited to small molecules by prohibitive computational expense [19]. Recent advances in neural network architectures and machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) are now bridging this gap, making CCSD(T)-level accuracy feasible for larger molecular systems, including polymers relevant to drug delivery [19] [20]. This guide objectively compares the performance of these computational approaches in predicting the essential polymer properties that govern drug delivery efficacy.

Comparative Analysis of DFT and Coupled-Cluster Theory

Fundamental Methodological Differences

The core distinction between these methods lies in their approach to calculating molecular system energies. Density Functional Theory (DFT) determines the total energy by examining the electron density distribution, which is the average number of electrons located in a unit volume around points in space near a molecule [19]. While successful, DFT has known drawbacks, including inconsistent accuracy across different systems and providing limited electronic information without additional computations [19]. In contrast, Coupled-Cluster Theory (CCSD(T)) offers a more sophisticated, wavefunction-based approach. It achieves much higher accuracy, often matching experimental results, by more completely accounting for electron correlation effects. However, this comes at a significant computational cost; doubling the number of electrons in a system can make computations 100 times more expensive, historically restricting its use to molecules with approximately 10 atoms [19].

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Computational Methods

| Feature | Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Coupled-Cluster Theory (CCSD(T)) |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Electron density distribution [19] | Wavefunction theory (electron correlation) [19] |

| Computational Cost | Relatively low, scalable to large systems | Very high, traditionally limited to small molecules [19] |

| Typical Accuracy | Good, but inconsistent; depends on functional [20] | High, considered the "gold standard" [19] |

| Primary Output | Total system energy [19] | Energy and multiple electronic properties [19] |

| Common Drug Delivery Applications | Polymer-drug adsorption energy, HOMO-LUMO gap, molecular geometry [21] [22] [23] | Creating benchmark datasets, training ML potentials, small model systems [19] [20] |

Performance Benchmarking and Accuracy

Discrepancies between DFT and CCSD(T) predictions are particularly pronounced for systems involving unpaired electrons, bond breaking/formation, and transition state energetics—critical aspects of drug loading and release dynamics [20]. For instance, when a neural network potential was trained on a UCCSD(T) dataset of organic molecules, it demonstrated a marked improvement of over 0.1 eV/Å in force accuracy and over 0.1 eV in activation energy reproduction compared to models trained on DFT data [20]. This highlights that the choice of the underlying quantum mechanical method fundamentally limits the accuracy of derived models.

DFT's performance can also vary significantly with the choice of the exchange-correlation functional and the need for empirical corrections. For example, many DFT studies on polymer-drug interactions explicitly incorporate Grimme's dispersion correction (DFT-D3) to account for weak long-range van der Waals forces, which are crucial for accurately modeling non-covalent interactions but are poorly described by standard functionals [23]. A study on the pectin-biased hydrogel delivery of Bezafibrate used the B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-311G level of theory, demonstrating DFT's capability to yield useful, experimentally relevant data when properly configured [23].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison for Drug Delivery Applications

| Performance Metric | DFT Performance | Coupled-Cluster (CCSD(T)) Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Adsorption Energy Prediction | Good with dispersion corrections; e.g., -42.18 kcal/mol for FLT@Cap [21] | Higher fidelity; used to benchmark and correct DFT data [20] |

| HOMO-LUMO Gap Calculation | Standard output; e.g., predicts gap reduction upon drug adsorption [21] [22] | High accuracy; improves ML potential transferability [19] [20] |

| Non-Covalent Interaction Analysis | Enabled via QTAIM/RDG; identifies H-bonding, van der Waals [21] [23] | More reliable description of electron correlation in interactions |

| Computational Scalability | Suitable for large systems (1000s of atoms) [24] | Traditionally for small molecules, now scaling to 1000s of atoms via ML [19] |

| Force/Geometry Optimization | Reasonable accuracy | >0.1 eV/Å improvement in force accuracy vs. DFT [20] |

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Standard DFT Workflow for Polymer-Drug Analysis

The typical DFT protocol for investigating a polymer-based drug delivery system involves a multi-step computational and experimental validation process, as exemplified by studies on nanocapsules and biopolymers [21] [23].

- System Preparation and Geometry Optimization: The molecular structures of the polymer carrier (e.g., benzimidazolone capsule, pectin biopolymer) and the drug molecule (e.g., Flutamide, Gemcitabine, Bezafibrate) are built. These structures are then optimized to their most stable, minimum-energy configuration using DFT software like Gaussian 09 at a level such as B3LYP [21] [23].

- Complex Formation and Interaction Energy Calculation: The optimized drug molecule is placed in various orientations on the polymer surface. The system is re-optimized, and the complexation energy is calculated, often applying dispersion corrections (D3) and solvent models (PCM) for physiological relevance [21] [23].

- Electronic Property Analysis: Key electronic properties are calculated for the complex and its components. This includes Frontier Molecular Orbital (FMO) analysis to determine the HOMO-LUMO energy gap, Density of States (DOS) spectra, and molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) surfaces [21] [22].

- Interaction Characterization: Advanced analyses like Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules (QTAIM) and Non-Covalent Interaction (NCI) analysis based on Reduced Density Gradient (RDG) are performed to identify and quantify interaction types (e.g., hydrogen bonding, van der Waals) [21] [22] [23].

- In Vitro/In Vivo Correlation (Optional): Computational predictions are correlated with experimental results such as drug release profiles under different pH conditions to validate the model [25].

Advanced Workflow: CCSD(T)-Trained Machine Learning Potentials

A cutting-edge approach leverages CCSD(T) to create highly accurate and transferable machine learning models, overcoming its traditional scalability limitations [19] [20].

- Reference Data Generation: Perform high-level UCCSD(T) calculations on a diverse set of small organic molecules and reaction intermediates. This includes automated construction of unrestricted Hartree-Fock references and application of basis set corrections for energies and forces [20].

- Active Learning and Dataset Curation: Use an ensemble of exploratory machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) to run molecular dynamics and sample reactive configurations. Structures with high prediction uncertainty are identified and added to the training set, ensuring efficient coverage of the chemical space [20].

- Machine Learning Model Training: Train a final MLIP (e.g., HIP-NN-TS) on the curated UCCSD(T) dataset of energies and forces. This model learns to reproduce CCSD(T)-level accuracy [20].

- Validation and Application: The trained MLIP is validated on known reaction barriers and energies. It can then be deployed to predict the properties of much larger systems, such as polymer-drug complexes, at a computational cost far lower than CCSD(T) and with superior accuracy to DFT-based models [19] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and analysis of polymeric drug delivery systems rely on a specific set of computational and material tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials in Polymer-Based Drug Delivery

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Benzimidazolone Capsule | A nanocapsule used as a nanocarrier for anticancer drugs like flutamide and gemcitabine [21]. | DFT investigation showed strong adsorption energies and good loading capacity [21]. |

| Pectin Biopolymer | A natural, water-soluble polysaccharide used as a biodegradable and non-toxic drug carrier [23]. | Forms strong hydrogen bonds with Bezafibrate drug, favorable for delivery [23]. |

| B12N12 Nanocluster | A boron nitride nanocluster known for high stability and non-toxicity, often doped with metals [22]. | Serves as a nanocarrier for β-Lapachone; doping with Au enhances conductivity and drug adsorption [22]. |

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | A biodegradable copolymer widely used in polymeric nanoparticles for drug encapsulation [26]. | Commonly optimized via DoE for attributes like particle size and drug release profile [26]. |

| Central Composite Design (CCD) | A statistical response surface methodology for optimizing formulation parameters [26]. | Reduces experimental workload while modeling complex variable interactions in polymer-based DDS [26]. |

The choice between DFT and coupled-cluster methodologies is a fundamental consideration in the computational design of polymeric drug delivery systems. DFT remains the practical workhorse for directly modeling large polymer-drug complexes, providing valuable insights into adsorption energies, electronic property changes, and non-covalent interactions, especially when employing modern dispersion corrections and solvent models [21] [22] [23]. In contrast, the gold-standard accuracy of CCSD(T) is increasingly accessible through innovative machine learning approaches, offering a path to more reliable predictions of reaction energetics and intermolecular forces that are critical for understanding drug loading and release mechanisms [19] [20].

The future of this field lies in the synergistic use of both methods. CCSD(T)-trained machine learning potentials can provide the accurate reference data needed to benchmark and refine DFT functionals for specific polymer-drug systems. Furthermore, advanced experimental design tools like Central Composite Design (CCD) will continue to play a crucial role in efficiently optimizing the critical quality attributes of these complex systems, bridging the gap between computational prediction and practical formulation [26]. As these computational and experimental methodologies continue to co-evolve, they will undoubtedly accelerate the development of next-generation, precision-targeted polymeric drug delivery vehicles.

In the pursuit of predicting molecular behavior with absolute confidence, computational chemists face a fundamental dilemma: choosing between the highly accurate but prohibitively expensive coupled cluster (CC) methods and the computationally efficient but sometimes approximate density functional theory (DFT). This trade-off between computational cost and accuracy forms the core challenge in modern quantum chemistry, particularly in fields like polymer science and drug development where reliable predictions can dramatically accelerate discovery timelines. While DFT has served as the workhorse for computational studies of large systems, its limitations in achieving uniform accuracy across diverse chemical spaces have driven the search for methods that can deliver coupled-cluster level precision at manageable computational cost. The emergence of novel computational frameworks, including machine-learning augmented quantum chemistry, is now reshaping this landscape, offering potential pathways to resolve this long-standing trade-off.

Theoretical Foundations: DFT and Coupled Cluster Theory

Density Functional Theory (DFT): The Workhorse of Computational Chemistry

Density Functional Theory has become the most widely used electronic structure method in computational chemistry and materials science due to its favorable balance between accuracy and computational cost. DFT operates on the fundamental principle that the ground-state energy of a quantum system can be expressed as a functional of the electron density, dramatically simplifying the computational problem compared to wavefunction-based methods. The accuracy of DFT crucially depends on the approximation used for the exchange-correlation functional, with popular choices including the B3LYP functional and the PBE0+MBD method used for geometry optimizations in benchmark studies [4] [27]. The key advantage of DFT lies in its scalability, with computational cost typically scaling as O(N³) with system size, making it applicable to systems containing hundreds or even thousands of atoms [6].

Coupled Cluster Theory: The Gold Standard for Accuracy

Coupled cluster theory, particularly the CCSD(T) method (coupled cluster with singles, doubles, and perturbative triples), represents the current "gold standard" in quantum chemistry for achieving high accuracy [19] [27]. Unlike DFT, coupled cluster theory systematically accounts for electron correlation effects through a wavefunction-based approach, with its limiting behavior approaching an exact solution to the Schrödinger equation [6]. This method delivers exceptional accuracy, typically within 1 kcal/mol of experimental values for small molecules, making it indispensable for benchmarking and applications requiring high precision [28]. However, this accuracy comes at a steep computational price, with canonical CCSD(T) scaling as O(N⁷) with system size, effectively limiting its application to molecules of approximately 10 atoms without additional approximations [19] [6].

Quantitative Comparison: Accuracy and Computational Cost

Performance Metrics for Quantum Chemistry Methods

Table 1: Comparative Accuracy of Quantum Chemistry Methods for Non-Covalent Interactions

| Method | Typical MAE (kcal/mol) | Application Domain | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCSD(T) | 0.5-1.0 [27] | Small molecules, benchmark studies | Gold standard accuracy, reliable for diverse systems | Prohibitive cost for large systems (>10 atoms) |

| Double-Hybrid DFT | 1.0-2.0 [28] | Medium-sized molecules | Near-CCSD(T) accuracy for some systems | Higher cost than standard DFT |

| Hybrid DFT (PBE0+MBD) | Varies widely [27] | Large systems, materials | Good balance for diverse applications | Inconsistent accuracy across chemical spaces |

| Semiempirical Methods | >2.0 [27] | Very large systems | High computational speed | Poor description of non-covalent interactions |

Table 2: Computational Scaling and Practical Limitations

| Method | Computational Scaling | Typical System Size Limit | Basis Set Dependence | Hardware Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canonical CCSD(T) | O(N⁷) [19] [6] | ~10 atoms [19] | Strong | High-performance computing clusters |

| Local CCSD(T) (DLPNO/LNO) | O(N⁴)-O(N⁵) [29] | ~100 atoms [29] | Moderate | Large memory nodes |

| Hybrid DFT | O(N⁴) [6] | Hundreds of atoms | Moderate | Standard computational nodes |

| Local DFT | O(N³) [6] | Thousands of atoms | Weak | Workstation to cluster |

Benchmark Studies: Direct Performance Comparison

Recent benchmark studies have quantitatively compared the performance of DFT and coupled cluster methods. The QUID (QUantum Interacting Dimer) benchmark framework, containing 170 non-covalent systems modeling ligand-pocket interactions, revealed that robust binding energies obtained using complementary CC and quantum Monte Carlo methods achieved agreement of 0.5 kcal/mol – a level of precision essential for reliable drug design [27]. The study found that while several dispersion-inclusive DFT approximations provide accurate energy predictions, their atomic van der Waals forces differ significantly in magnitude and orientation compared to high-level references. Meanwhile, semiempirical methods and empirical force fields showed substantial limitations in capturing non-covalent interactions for out-of-equilibrium geometries [27].

In the context of polymer research, DFT has demonstrated utility but with notable limitations. Studies on conjugated polymers found only weak correlation (R² = 0.15) between DFT-calculated HOMO-LUMO gaps and experimentally measured optical gaps when using unmodified monomer structures [30]. Through strategic modifications including alkyl side chain truncation and conjugated backbone extension, this correlation could be improved to R² = 0.51, yet this still highlights the inherent accuracy limitations of standard DFT approaches for complex materials [30].

Machine Learning Bridges the Gap: Emerging Solutions

ML-Augmented Quantum Chemistry Methods

Table 3: Machine Learning Approaches for Quantum Chemistry

| Method | Base Theory | Target Accuracy | Key Innovation | Demonstrated Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEHnet [19] | CCSD(T) | CCSD(T)-level for large molecules | Multi-task E(3)-equivariant graph neural network | Thousands of atoms with CCSD(T) accuracy |

| DeePHF [28] | DFT → CCSD(T) | CCSD(T)-level for reactions | Maps local density matrices to correlation energies | Reaction energies and barrier heights |

| Δ-Learning [29] | DFT → CCSD(T) | CCSD(T)-level for condensed phases | Corrects baseline DFT with cluster-trained MLP | Liquid water with CCSD(T) accuracy |

| NEP-MB-pol [31] | Many-body → CCSD(T) | CCSD(T)-level for water | Neuroevolution potential trained on MB-pol data | Water's thermodynamic and transport properties |

Recent advancements have introduced machine learning techniques to bridge the accuracy-cost gap between DFT and coupled cluster theory. The Multi-task Electronic Hamiltonian network (MEHnet) represents a novel neural network architecture that can extract multiple electronic properties from a single model while achieving CCSD(T)-level accuracy [19]. This approach utilizes an E(3)-equivariant graph neural network where nodes represent atoms and edges represent bonds, incorporating physics principles directly into the model architecture. When tested on hydrocarbon molecules, MEHnet outperformed DFT counterparts and closely matched experimental results [19].

The Deep post-Hartree-Fock (DeePHF) framework establishes a direct mapping between the eigenvalues of local density matrices and high-level correlation energies, achieving CCSD(T)-level precision while maintaining DFT efficiency [28]. This approach has demonstrated particular success in predicting reaction energies and barrier heights, significantly outperforming traditional DFT and even advanced double-hybrid functionals while maintaining O(N³) scaling [28].

For condensed phase systems, Δ-learning approaches have shown remarkable success. These methods combine a baseline machine learning potential trained on periodic DFT data with a Δ-MLP fitted to energy differences between baseline DFT and CCSD(T) from gas phase clusters [29]. This strategy has enabled CCSD(T)-level simulations of liquid water, including constant-pressure simulations that accurately predict water's density maximum – a property notoriously difficult to capture with conventional DFT [29].

ML-Augmented Quantum Chemistry Workflow - This diagram illustrates how machine learning bridges the cost-accuracy gap by combining efficient DFT calculations with neural network corrections to achieve coupled-cluster level accuracy.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking Non-Covalent Interactions: The QUID Protocol

The QUID benchmark framework exemplifies rigorous methodology for assessing quantum chemistry methods [27]. The protocol begins with selecting nine chemically diverse drug-like molecules (including C, N, O, H, F, P, S, and Cl atoms) from the Aquamarine dataset, representing common fragments in pharmaceutical compounds. Two small monomers (benzene and imidazole) are selected to represent ligand interactions. Initial dimer conformations are generated with aromatic rings aligned at distances of 3.55 ± 0.05 Å, followed by geometry optimization at the PBE0+MBD level of theory. The resulting 42 equilibrium dimers are classified into 'Linear', 'Semi-Folded', and 'Folded' categories based on structural morphology. For non-equilibrium conformations, 16 representative dimers are selected and geometries are generated along dissociation pathways using eight dimensionless scaling factors (q = 0.90, 0.95, 1.00, 1.05, 1.10, 1.25, 1.50, 1.75, 2.00) relative to equilibrium distances. Interaction energies are computed using both CCSD(T) and DFT methods, with the CCSD(T) calculations serving as the reference "platinum standard" when consistent with quantum Monte Carlo results.

Machine Learning Potential Development: The Δ-Learning Protocol

The Δ-learning approach for developing CCSD(T)-accurate machine learning potentials follows a multi-stage protocol [29]. First, a baseline machine learning potential is trained on periodic DFT data using molecular dynamics simulations to ensure robust sampling of configuration space. Next, representative clusters are extracted from equilibrium molecular dynamics trajectories, typically containing 64 water molecules for aqueous systems. Single-point CCSD(T) calculations are performed on these clusters using local correlation approximations (DLPNO or LNO) to make computations tractable. A Δ-machine learning potential is then trained to predict the energy differences between the high-level CCSD(T) and baseline DFT for these clusters. The final model combines the baseline MLP and Δ-MLP, with forces obtained through automatic differentiation. This composite model is validated against experimental properties such as radial distribution functions and diffusion constants, with path-integral molecular dynamics simulations incorporated to account for nuclear quantum effects.

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools for Quantum Chemistry

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Quantum Chemistry Research

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Packages | Gaussian, ORCA, PySCF | Perform DFT and CC calculations | Core quantum chemistry computations |

| Local Correlation Methods | DLPNO-CCSD(T), LNO-CCSD(T) | Reduce CC computation cost | Extending CC to ~100 atoms [29] |

| Machine Learning Potentials | DeePHF, MEHnet, NEP | Learn CCSD(T) accuracy from data | Large systems with CC accuracy [19] [28] [31] |

| Benchmark Datasets | QUID, Grambow's dataset | Method validation and training | Testing method accuracy [27] [28] |

| Molecular Dynamics Engines | LAMMPS, i-PI | Perform MD simulations | Sampling configurational space [29] [31] |

The critical trade-off between computational cost and accuracy in quantum chemistry is being fundamentally transformed by methodological innovations. While the distinction remains that coupled cluster theory should be preferred when the highest accuracy is essential and computational resources permit, and DFT when studying larger systems where approximate solutions are sufficient, machine learning approaches are rapidly blurring these boundaries. The emerging paradigm of ML-augmented quantum chemistry demonstrates that CCSD(T)-level accuracy can be achieved for systems containing thousands of atoms – previously the exclusive domain of DFT – by leveraging physical insights and efficient neural network architectures [19]. As these methods continue to mature, their integration into commercial and open-source computational chemistry packages will make gold-standard accuracy more accessible to researchers across polymer science, pharmaceutical development, and materials design, potentially reshaping the landscape of computational molecular discovery.

Practical Applications: Predicting Polymer Properties for Drug Delivery Systems

The rational design of polymer-based drug delivery systems represents a paradigm shift from traditional empirical methods to a precision-driven approach grounded in computational molecular engineering. At the heart of this transformation lies density functional theory (DFT), a quantum mechanical modeling method that has become indispensable for predicting and analyzing drug-polymer interactions at the atomic level. By solving the Kohn-Sham equations with precision approaching 0.1 kcal/mol, DFT enables researchers to reconstruct electronic structures and elucidate the fundamental driving forces behind molecular recognition, binding affinity, and controlled release mechanisms in pharmaceutical formulations [32]. This computational methodology provides critical insights that guide the development of advanced drug delivery systems while significantly reducing the need for resource-intensive experimental trial-and-error.

The application of DFT must be contextualized within the broader spectrum of quantum chemical methods, particularly when assessing its performance against the gold standard of coupled-cluster theory with single, double, and perturbative triple excitations (CCSD(T)). While CCSD(T) approaches the exact solution to the Schrödinger equation and provides benchmark accuracy for molecular systems, its computational expense scales prohibitively with system size, making it impractical for the large, complex polymer-drug systems typical in pharmaceutical applications [33]. This accuracy-efficiency dichotomy frames the ongoing research imperative: to develop and validate computational approaches that balance chemical accuracy with practical computational feasibility for drug delivery applications.

Theoretical Framework: DFT Versus Coupled-Cluster Theory

Fundamental Methodological Differences

Density functional theory operates on the fundamental principle that the ground-state properties of a multi-electron system are uniquely determined by its electron density, elegantly simplifying the complex many-body problem through the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems and Kohn-Sham equations [32] [34]. This density-based approach stands in stark contrast to the wavefunction-based coupled-cluster theory, which systematically accounts for electron correlation effects through exponential excitation operators [33]. The mathematical and conceptual distinctions between these methodologies create significant differences in their computational scaling, application range, and predictive reliability for pharmaceutical systems.

CCSD(T) is widely regarded as the gold standard for quantum chemical calculations, particularly for thermochemical properties and non-covalent interactions. When combined with complete basis set (CBS) extrapolation, it provides benchmark accuracy that can quantitatively predict even challenging intermolecular interactions [33]. However, this accuracy comes at a staggering computational cost that scales as N⁷ (where N represents the system size), effectively limiting its practical application to systems with approximately 10-20 non-hydrogen atoms [33]. This severe limitation renders CCSD(T) unsuitable for direct application to most polymer-drug systems, which typically comprise hundreds to thousands of atoms.

Comparative Performance in Molecular Property Prediction

Table 1: Accuracy Comparison Between DFT Functionals and CCSD(T) for Molecular Properties

| Computational Method | Functional Class | Mean Absolute Deviation (kcal/mol) | Best For Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCSD(T)/CBS | Coupled-Cluster | 0.0 (Reference) | Benchmark accuracy for small systems | Prohibitively expensive for >20 atoms |

| OPBE | GGA | ~2.0 | SN2 reactions, geometries [35] | Inaccurate for dispersion forces |

| OLYP | GGA | ~2.0 | Reaction geometries [35] | Poor for van der Waals interactions |

| B3LYP | Hybrid | >2.0 | General-purpose, molecular spectroscopy [35] [32] | Underestimates barrier heights |

| B3LYP-D3(BJ) | Hybrid with dispersion | ~1.0-2.0 | Drug-polymer interactions with dispersion [23] | Empirical dispersion correction |

| mPW1PW91 | Hybrid | Varies | IR spectra, NMR chemical shifts [36] | Parameter dependent |

DFT achieves its remarkable efficiency through various approximations of the exchange-correlation functional, which encompass different trade-offs between accuracy and computational cost. The local density approximation (LDA) represents the simplest functional but inadequately describes weak interactions crucial for drug-polymer systems. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) significantly improves upon LDA by incorporating density gradient corrections, with functionals like OPBE and OLYP achieving mean absolute deviations of approximately 2 kcal/mol relative to CCSD(T) benchmarks for reaction energies and barriers [35]. Hybrid functionals such as B3LYP and mPW1PW91 include a portion of exact Hartree-Fock exchange and offer improved accuracy for many molecular properties, though their performance varies significantly across different chemical systems [35] [36].

For pharmaceutical applications involving drug-polymer interactions, the accurate description of non-covalent interactions presents a particular challenge for standard DFT functionals. These limitations are addressed through empirical dispersion corrections, such as the DFT-D3 method with Becke-Johnson damping, which incorporates van der Waals interactions that are crucial for modeling adsorption processes in drug delivery systems [23]. This approach has demonstrated considerable success in predicting binding energies and interaction mechanisms in polymer-based drug delivery platforms.

DFT Applications in Drug-Polymer Systems: Methodologies and Protocols

Computational Analysis of Polymer-Based Drug Delivery

Table 2: DFT Applications in Drug-Polymer Interaction Studies

| Study System | DFT Method | Key Interactions Analyzed | Binding Energy (kJ/mol) | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bezafibrate-Pectin [23] | B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-311G | Hydrogen bonding (1.56 Å, 1.73 Å) | -81.62 | FT-IR spectra |

| Curcumin-PLGA-MMT [34] | Not specified | π-π stacking, hydrogen bonding | Not reported | Compatibility studies |

| Gemcitabine-h-BN [34] | Not specified | π-π stacking | -15.08 | Not reported |

| Gemcitabine-PEG-h-BN [34] | Not specified | π-π stacking, hydrogen bonding | -90.74 | Not reported |

| Letrozole-MAA-TMPT [34] | Not specified | Hydrogen bonding | Not reported | Adsorption experiments |

The investigation of bezafibrate interaction with pectin biopolymer exemplifies a comprehensive DFT protocol for drug delivery applications [23]. This study employed Gaussian 09 software with the B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-311G theoretical level, incorporating Grimme's D3 dispersion correction with Becke-Johnson damping to account for long-range van der Waals interactions. The polarizable continuum model (PCM) was applied to simulate aqueous solvent effects, a critical consideration for pharmaceutical applications [23]. Geometry optimization procedures began with structural construction of individual components, followed by energy minimization to locate ground-state configurations. The drug-polymer complex was then assembled, and its geometry was re-optimized to identify the most thermodynamically stable configuration.

Quantum chemical descriptors derived from these calculations provide crucial insights into interaction mechanisms. The quantum theory of atoms in molecules (QTAIM) analysis enables topological characterization of bond critical points, revealing the nature and strength of specific interactions. Natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis quantifies charge transfer and donor-acceptor interactions, while the reduced density gradient (RDG) method visualizes non-covalent interaction regions through isosurface plots [23] [34]. For the bezafibrate-pectin system, RDG analysis revealed strong hydrogen bonding at two distinct sites with bond lengths of 1.56 Å and 1.73 Å, which played a critical role in the binding mechanism [23].

Electronic Properties and Reactivity Descriptors

Frontier molecular orbital analysis provides essential parameters for predicting reactivity trends in drug-polymer systems. The energy gap (E₉) between highest occupied and lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals (HOMO-LUMO) serves as a valuable indicator of stability and charge transfer propensity. DFT calculations enable the computation of molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) maps, which visualize charge distributions and identify nucleophilic and electrophilic regions susceptible to interaction [32]. Additionally, conceptual DFT indices including chemical hardness (η), electrophilicity (ω), and Fukui functions enable quantitative predictions of reactive sites and interaction preferences in complex drug-polymer systems [34].

Diagram 1: DFT Workflow for Drug-Polymer Interaction Studies

Performance Benchmarking: Quantitative Accuracy Assessment

Systematic Comparison with Coupled-Cluster Benchmarks

A comprehensive evaluation of DFT performance for chemical systems relevant to pharmaceutical applications was conducted through systematic benchmarking against CCSD(T)/CBS reference data [35]. This study assessed multiple DFT functionals across various classes—including LDA, GGA, meta-GGA, and hybrid functionals—for their ability to reproduce coupled-cluster potential energy surfaces of nucleophilic substitution reactions. The results demonstrated that the most accurate GGA, meta-GGA, and hybrid functionals yield mean absolute deviations of approximately 2 kcal/mol relative to CCSD(T) benchmarks for reactant complexation, reaction barriers, and reaction energies [35].

Notably, the study identified OPBE (a GGA functional) and OLYP (another GGA functional) as top performers for both energies and geometries, with average absolute deviations in bond lengths of 0.06 Å and 0.6 degrees—surpassing even meta-GGA and hybrid functionals [35]. The popular B3LYP functional delivered suboptimal performance, significantly underperforming relative to the best GGA functionals for these chemical systems [35]. These findings highlight the critical importance of functional selection for specific application domains, as no single functional excels across all chemical domains.

Emerging Approaches: Neural Network Potentials and Multiscale Modeling

Recent advances in machine learning have enabled the development of neural network potentials that approach coupled-cluster accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency comparable to classical force fields. The ANI-1ccx potential represents a groundbreaking achievement in this domain, utilizing transfer learning to first train on DFT data then refine on a targeted set of CCSD(T)/CBS calculations [33]. This approach achieves CCSD(T)-level accuracy for reaction thermochemistry, isomerization energies, and drug-like molecular torsions while being billions of times faster than direct CCSD(T) calculations [33].

The integration of DFT with multiscale modeling frameworks addresses another critical challenge in drug-polymer system simulation. The ONIOM method combines high-precision DFT calculations for core regions of interest with molecular mechanics treatments of the surrounding environment, enabling realistic simulation of large-scale polymer systems [32]. Additionally, the emergence of machine learning-augmented DFT approaches and high-throughput screening frameworks promises to further accelerate the digitalization of molecular engineering in pharmaceutical formulation science [32].

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools for Drug-Polymer Studies

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for DFT Studies of Drug-Polymer Systems

| Tool Category | Specific Software/Package | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT Software | Gaussian 09/16 [23] [34] | Geometry optimization, frequency calculation | Bezafibrate-pectin interaction [23] |

| Plane-Wave DFT | CASTEP, ABINIT, VASP [34] | Periodic boundary calculations | Polymer crystal structure |

| Atomic Simulation | Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE) [33] | Atomistic simulation environment | Neural network potential integration |

| Wavefunction Analysis | Multiwfn, AIMAll [34] | Electron density analysis | QTAIM, RDG analysis |

| Visualization | GaussView, VMD, ChemCraft [34] | Molecular structure visualization | Complex structure rendering |

| Neural Network Potential | ANI-1x, ANI-1ccx [33] | Machine learning potentials | Coupled-cluster accuracy approximation |

The selection of appropriate basis sets represents another critical consideration in DFT studies of drug-polymer systems. The 6-31G(d) and 6-31G(d,p) basis sets are widely employed for their balance between accuracy and computational efficiency for organic systems [36] [34]. For more demanding applications, the 6-311G basis set provides improved accuracy through triple-zeta quality valence orbitals [23]. Different DFT codes employ various representations for electron wavefunctions, including Gaussian-type orbitals (Gaussian, GAMESS), numerical atomic orbitals (DMol³), and plane-wave basis sets (CASTEP, ABINIT) [34], each with distinct strengths for specific application scenarios.

Diagram 2: Computational Parameters for Drug-Polymer DFT Studies

Density functional theory has established itself as an indispensable computational tool for modeling drug-polymer interactions and predicting binding energies in pharmaceutical formulation development. While methodological limitations persist—particularly in describing dispersion-dominated systems and dynamic processes in solution—ongoing advancements in functional development, dispersion corrections, and solvation models continue to expand DFT's applicability and reliability. The systematic benchmarking against coupled-cluster benchmarks provides crucial validation of DFT's quantitative accuracy, with the best functionals achieving mean absolute deviations of approximately 2 kcal/mol for relevant energy properties [35].

The emerging paradigm of multiscale modeling combines DFT with machine learning approaches and classical simulation methods, offering a comprehensive framework for addressing the complex, hierarchical nature of polymer-based drug delivery systems [32]. The development of neural network potentials like ANI-1ccx that approach coupled-cluster accuracy with dramatically reduced computational expense represents particularly promising direction for future research [33]. As these methodologies continue to mature and integrate with high-throughput screening platforms, computational approaches will play an increasingly central role in accelerating the design and optimization of advanced drug delivery systems, ultimately reducing development timelines and improving therapeutic outcomes.

For researchers investigating drug-polymer interactions, the recommended protocol employs dispersion-corrected hybrid functionals (e.g., B3LYP-D3(BJ)) with triple-zeta basis sets (6-311G) and implicit solvation models (PCM) for optimal accuracy-efficiency balance [23]. This approach, combined with advanced charge analysis and non-covalent interaction visualization techniques, provides comprehensive atomistic insights into the binding mechanisms and energetics governing drug delivery system performance.

Benchmarking DFT Performance for Conjugated Polymer Band Gaps

The accurate prediction of the optical band gap in conjugated polymers (CPs) represents a fundamental challenge in computational materials science and organic electronics development. This property directly governs key performance characteristics in applications ranging from organic photovoltaics (OPV) to flexible displays and biosensors. Within this context, density functional theory (DFT) has emerged as the predominant computational workhorse for initial screening and design, while coupled cluster (CC) theory is widely recognized as a more accurate—but computationally demanding—alternative. This review performs a critical benchmarking analysis of DFT's performance for conjugated polymer band gap prediction, situating its capabilities and limitations within the broader framework of electronic structure theory, and highlighting recent methodological advances that integrate machine learning to enhance predictive accuracy.

Table 1: Computational Method Comparison for Electronic Property Prediction

| Method | Theoretical Foundation | Scaling with System Size | Typical Application Scope | Key Limitation for Polymers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Approximate exchange-correlation functional | N³ (for local functionals) | Systems of hundreds of atoms; periodic structures | Systematic band gap underestimation; functional dependence |

| Coupled Cluster (CC) Theory | Wavefunction-based; iterative solution | N⁷ (for CCSD) to N¹⁰ (for CCSD(T)) | Small molecules (<50 atoms) | Prohibitively expensive for polymer repeats; difficult periodic implementation |

| DFT+Machine Learning | DFT generates training data for ML models | Varies (ML model-dependent) | High-throughput screening of thousands of polymers | Dependent on quality and diversity of training data |

Theoretical Framework: DFT vs. Coupled Cluster Theory

Fundamental Methodological Differences

The divergence between DFT and coupled cluster theory originates from their fundamentally different approaches to solving the electronic Schrödinger equation. DFT operates within the paradigm of electronic density as the central variable, relying on approximate exchange-correlation functionals to describe electron-electron interactions. In contrast, coupled cluster theory employs a wavefunction-based approach, constructing an exponential ansatz to systematically account for electron correlation effects. The theoretical limiting behavior of CC theory—inclusion of all possible excitations with a complete orbital basis set—converges to an exact solution of the Schrödinger equation, a guarantee that no known approximate DFT functional can provide [6].

This theoretical superiority comes with severe practical constraints. The computational cost of canonical coupled cluster theory scales combinatorically with system size, making it intractable for the extended molecular structures characteristic of conjugated polymers. As one analysis notes, "About the largest molecule you could expect to calculate accurately using canonical CC theory is benzene, and even that would be very expensive" [6]. For conjugated polymers, which require substantial molecular structures to accurately model their extended π-systems, this limitation is particularly debilitating.

Practical Considerations for Polymer Systems

The implementation of quantum chemical methods for conjugated polymers presents unique challenges beyond those encountered with small molecules. Periodic boundary conditions, essential for modeling bulk polymer properties, remain exceptionally difficult to implement for coupled cluster methods and constitute an active area of research [6]. Furthermore, the presence of alkyl side chains—critical for processability but electronically inert—adds to the computational burden without contributing meaningfully to electronic properties of interest. One benchmarking study highlighted this challenge, noting that using unmodified side-chain-containing monomers resulted in a poor correlation (R² = 0.15) between calculated HOMO-LUMO gaps and experimental optical gaps [7].

Figure 1: Theoretical Methods Landscape for Polymer Band Gap Prediction

Benchmarking DFT Performance: Methodologies and Metrics

Standard Protocols for Accurate Oligomer Modeling

Recent research has established sophisticated protocols to enhance the predictive accuracy of DFT for conjugated polymers. A critical advancement involves structural modifications to monomeric units that better approximate the electronic environment of extended polymers. One comprehensive study utilizing 1,096 data points demonstrated that through alkyl side chain truncation and conjugated backbone extension, the modified oligomers significantly improve the correlation between DFT-calculated HOMO-LUMO gaps (Eoligomergap) and experimental optical gaps (Eexpgap), increasing R² from 0.15 for unmodified monomers to 0.51 for optimized structures [7].

The selection of appropriate exchange-correlation functionals represents another critical methodological consideration. While generalized gradient approximation (GGA) functionals often severely underestimate band gaps, range-separated hybrids such as CAM-B3LYP have demonstrated improved performance for conjugated systems with extended π-delocalization [37]. One systematic investigation of donor-acceptor polymers highlighted that functionals with exact exchange admixture better describe charge transfer states, which are particularly relevant in the push-pull architectures common in modern organic photovoltaics.

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

The integration of machine learning with DFT calculations has produced remarkable improvements in predictive accuracy for conjugated polymer band gaps. In one landmark study, researchers manually curated a dataset of 3,120 donor-acceptor conjugated polymers and systematically investigated how different descriptors and fingerprint types impact model performance [38] [39]. Their findings revealed that kernel partial least-squares (KPLS) regression utilizing radial and molprint2D fingerprints achieved exceptional accuracy in predicting band gaps, with R² values of 0.899 and 0.897, respectively [38] [39].

Another approach focused specifically on predicting experimentally measured optical gaps achieved similarly impressive results. By employing the XGBoost algorithm with two categories of features—DFT-calculated oligomer gaps to represent the extended backbone and molecular features of unmodified monomers to capture alkyl-side-chain effects—researchers developed a model (XGBoost-2) that achieved an R² of 0.77 and MAE of 0.065 eV, falling within the experimental error margin of ∼0.1 eV [7]. Notably, this model demonstrated both excellent interpolation for common polymer classes and exceptional extrapolation capability for emerging materials systems when validated on a dataset of 227 newly synthesized conjugated polymers collected from literature without further retraining [7].

Table 2: Benchmarking DFT and ML-DFT Hybrid Methods for Band Gap Prediction

| Methodology | System Size | Key Structural Features | Prediction Accuracy (R²) | Mean Absolute Error (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFT (Unmodified monomers) | 1,096 data points | Full side chains | 0.15 | Not reported |

| DFT (Modified oligomers) | 1,096 data points | Truncated side chains, extended backbones | 0.51 | Not reported |

| XGBoost-2 (ML-DFT hybrid) | 1,096 training, 227 validation | DFT oligomer gaps + monomer features | 0.77 | 0.065 |

| KPLS with Radial Fingerprints | 3,120 donor-acceptor polymers | Radial and molprint2D fingerprints | 0.899 | Not reported |

| Random Forest Model | 563 small organic molecules | Aromatic ring count, TPSA, MolLogP | 0.86 | Not reported |

Integrated DFT-Machine Learning Workflows

The limitations of standalone DFT for band gap prediction have catalyzed the development of sophisticated hybrid workflows that leverage machine learning to bridge the accuracy gap between computational efficiency and experimental fidelity. These approaches typically employ DFT as a data generation engine, followed by ML models that learn the systematic relationships between chemically intuitive descriptors and target electronic properties.

Figure 2: Integrated DFT-ML Workflow for Band Gap Prediction

Descriptor Selection and Feature Importance

The success of ML-DFT hybrid approaches critically depends on judicious selection of molecular descriptors that effectively capture the essential physics governing optical transitions in conjugated polymers. Analysis of feature importance in high-performing models has consistently identified aromatic ring count as the most significant predictor (feature importance: 0.47), followed by topological polar surface area (TPSA) and molecular lipophilicity (MolLogP) [37]. For predicting hole reorganization energy (λh)—another critical parameter for charge transport—models integrating electronic descriptors such as frontier orbital energy levels significantly improved performance, achieving an R² value of 0.830 [38] [39].