Controlling Dispersity in RAFT Polymerization: Methods, Optimization, and Biomedical Applications

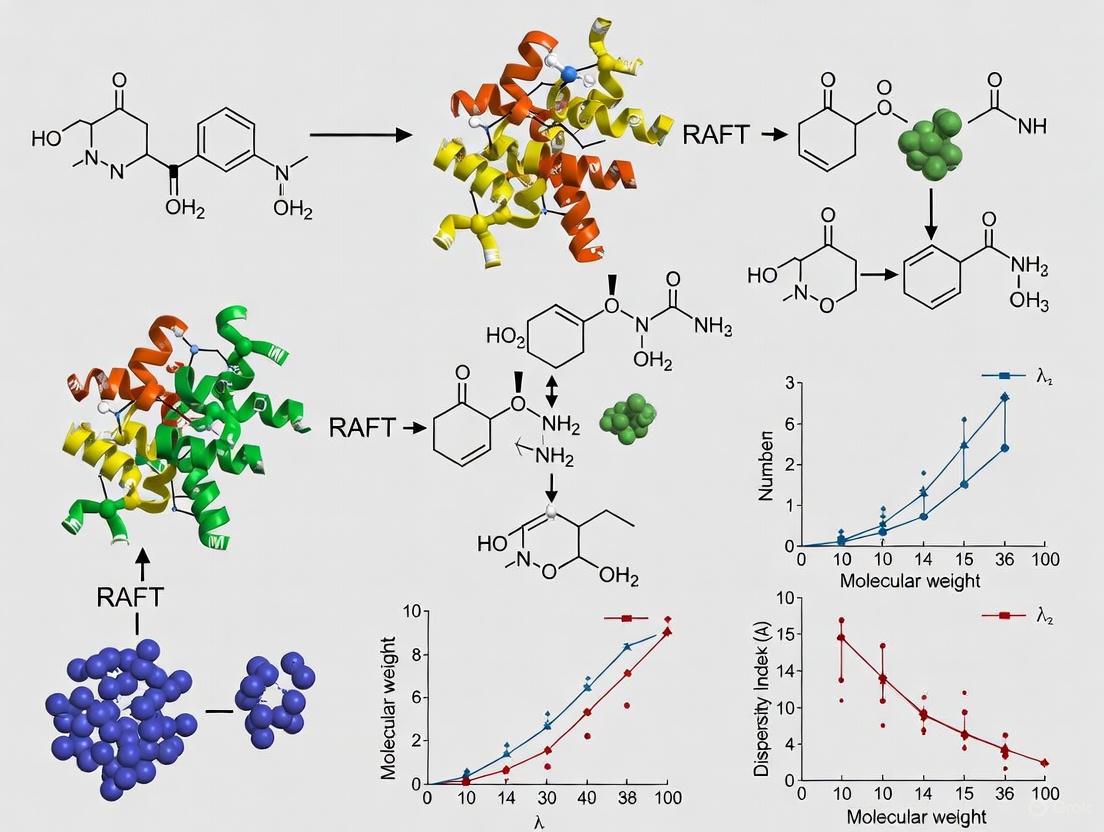

This article provides a comprehensive overview of advanced strategies for controlling the dispersity (Ð) of polymers synthesized via Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain-Transfer (RAFT) polymerization.

Controlling Dispersity in RAFT Polymerization: Methods, Optimization, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of advanced strategies for controlling the dispersity (Ð) of polymers synthesized via Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain-Transfer (RAFT) polymerization. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, innovative methodological approaches including switchable RAFT agents and photoinduced processes, and systematic optimization techniques like Design of Experiments (DoE). The content also includes troubleshooting for common challenges, a comparative analysis with other controlled polymerization techniques, and explores the critical impact of polymer dispersity on material properties and the performance of biomedical applications such as nanocarriers and therapeutic delivery systems.

Dispersity in RAFT Polymerization: Why Molecular Weight Distribution Matters

Defining Dispersity (Ð) and Its Significance for Polymer Properties

What is Dispersity?

Dispersity (Ð), formerly known as the Polydispersity Index (PDI), is a fundamental parameter in polymer science that measures the heterogeneity of sizes of molecules or particles in a mixture. It quantifies the breadth of the molecular weight distribution within a polymer sample [1] [2].

A polymer sample is never a collection of identical chains. Instead, it contains chains of varying lengths, and therefore, different molecular weights. Dispersity describes this distribution [3]. It is calculated as the ratio of the weight-average molecular weight ((Mw)) to the number-average molecular weight ((Mn)):

- Number-Average Molecular Weight ((M_n)): This is a simple average, representing the total weight of all polymer chains divided by the total number of chains. It is determined by techniques that count molecules, such as end-group analysis or colligative property measurements [3].

- Weight-Average Molecular Weight ((M_w)): This average is weighted toward the mass of the polymer chains. It is more sensitive to the presence of higher molecular weight chains and is determined by techniques like static light scattering or size exclusion chromatography (SEC) coupled with multi-angle light scattering (MALS) [2] [3] [5].

Table 1: Key Molecular Weight Averages and Their Significance

| Average | Symbol | Sensitivity | Common Determination Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number-Average | (M_n) | Simple average; counts all chains equally | End-group analysis (e.g., NMR), vapor pressure osmometry |

| Weight-Average | (M_w) | Sensitive to higher mass chains | Static Light Scattering, SEC-MALS |

The value of dispersity provides immediate insight into the uniformity of a polymer sample:

- Ð ≈ 1.0: Indicates a uniform (or monodisperse) polymer, where all chains are nearly identical in length. This is characteristic of many natural polymers (e.g., proteins, DNA) and those made by highly controlled synthetic methods like living anionic polymerization [1] [2].

- Ð > 1.0: Indicates a non-uniform (or polydisperse) polymer, with a distribution of chain lengths. All synthetic polymers have dispersities greater than 1, with values typically ranging from 1.02 to over 20, depending on the polymerization mechanism and conditions [1] [2].

It is crucial to note that two polymers can have the same dispersity value but very different distributions of chain lengths if their number-average molecular weights ((Mn)) are different. The standard deviation of the distribution is related to both Đ and (Mn), meaning a polymer with a higher (M_n) will have a much broader absolute range of molecular weights at the same Đ value [5].

Why is Controlling Dispersity Critical in RAFT Polymerization?

Reversible Addition-Fragmentation chain-transfer (RAFT) polymerization is a powerful controlled radical polymerization technique that allows for the synthesis of polymers with precise control over molecular weight, architecture, and end-group functionality [6]. Controlling dispersity is a central aspect of leveraging RAFT for advanced material design.

Dispersity is a key indicator of the control and fidelity achieved during a RAFT polymerization. A low dispersity (typically Đ < 1.2) suggests a well-behaved polymerization where all polymer chains have had similar opportunities to grow, resulting in a narrow distribution of chain lengths and high end-group fidelity. This is essential for synthesizing well-defined block copolymers, as the second block must efficiently extend from the first [2] [5].

Conversely, dispersity significantly affects the physical properties of the resulting polymers, which in turn dictates their performance in applications. For researchers in drug development and material science, tuning dispersity is not just about synthetic control; it is a direct strategy for tailoring material behavior [2] [7].

Table 2: Effects of Dispersity on Key Polymer Properties

| Property | Low Dispersity (Ð ~1.1) | High Dispersity (Ð > 1.4) |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Strength | More predictable and often higher | Can be reduced; broader chain length distribution can lead to weak points |

| Viscosity | Lower for a given (M_n) | Generally higher for a given (M_n) [8] |

| Thermal Properties | Sharper glass transition temperature ((T_g)) | Broader glass transition temperature ((T_g)) [5] |

| Self-Assembly | Forms more ordered and uniform nanostructures [5] | Can lead to mixed or defective morphologies [5] |

| Processability | More consistent melt flow | Can be easier to process in some cases due to broader melting range |

| Drug Release / Bioavailability | More consistent and predictable release profiles | Can be variable due to a wider range of degradation rates |

How Can Dispersity Be Experimentally Measured and Interpreted?

The primary method for determining the dispersity of a polymer sample is Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), also known as Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) [2].

Experimental Protocol: Determining Dispersity via SEC

- Sample Preparation: The polymer sample is dissolved in an appropriate eluent solvent (e.g., THF, DMF) at a specific concentration (typically 1-5 mg/mL) and filtered to remove any particulate matter.

- Instrument Calibration: The SEC system is calibrated using narrow dispersity polymer standards (e.g., polystyrene or poly(methyl methacrylate) of known molecular weights. This creates a calibration curve that relates retention time to molecular size (hydrodynamic volume) [2].

- Chromatography: The polymer solution is injected into the SEC system. The polymer chains are separated as they pass through a porous column. Larger chains, with a smaller hydrodynamic volume, elute first, followed by progressively smaller chains.

- Detection and Analysis: A detector (commonly a refractive index detector) measures the concentration of polymer eluting at each retention time. Advanced setups use multiple detectors, such as Multi-Angle Light Scattering (MALS) and viscometers, to obtain absolute molecular weights without relying on polymer standards [5]. Software then uses the calibration curve and detector signal to calculate (Mn), (Mw), and subsequently, the dispersity (Ð).

Interpreting SEC Data:

- A symmetrical, narrow peak on the SEC chromatogram indicates a low dispersity.

- A broad peak indicates a high dispersity.

- A peak with a "tail" at either high or low molecular weights indicates an asymmetric distribution, which can be quantified by an asymmetry factor (As) [2] [5].

Workflow for Determining Dispersity

What Methods Are Used to Tune Dispersity in RAFT Polymerization?

In RAFT polymerization, dispersity is not a fixed parameter; it can be deliberately tailored for specific applications. Several advanced strategies have been developed to control both the breadth (dispersity) and shape of the molecular weight distribution [2] [7].

1. Polymer Blending:

- Methodology: This is the most straightforward approach. Pre-synthesized polymer samples with different, well-defined molecular weights (and thus different dispersities) are physically mixed in precise ratios to achieve a target overall dispersity [2].

- Advantages: Simple, requires no reaction optimization, and provides access to any dispersity value within the range of the starting materials.

- Limitations: Produces bimodal or multimodal molecular weight distributions, which may not be desirable for all applications. It can be tedious, requiring the synthesis and purification of multiple polymer batches [2].

2. Temporal Regulation of Initiation:

- Methodology: The initiator is fed into the polymerization reaction at a controlled rate instead of being added all at once. By varying the addition profile (rate, timing), chains are initiated at different times, leading to a controlled distribution of chain lengths [2].

- Advantages: Allows for precise control over both dispersity and the shape (symmetry) of the distribution (e.g., creating peaks skewed towards high or low molecular weight) while maintaining high end-group fidelity for block copolymer synthesis [2].

- Limitations: Requires specialized equipment for controlled feeding and is less practical for heterogeneous structures like polymer brushes [2].

3. Using Switchable or Mixed RAFT Agents:

- Methodology: This involves using a single RAFT agent whose activity can be switched (e.g., by a change in pH or solvent composition) or by employing a mixture of two or more chain-transfer agents (CTAs) with different transfer activities in the same polymerization [9] [7].

- Advantages: A highly versatile one-pot method that can yield a wide range of dispersity values (e.g., from 1.16 to 1.58 in one study [9]) for homopolymers and block copolymers. It leverages the standard RAFT toolkit.

- Protocol Example: In one study, a switchable RAFT agent was used in mixtures of water and organic solvents like acetonitrile (ACN). The dispersity was controlled by varying the amount of acid added or the solvent composition, with ACN requiring the lowest acid amount to achieve low dispersity (e.g., 2 equivalents of acid yielded Đ ~1.19) [9].

4. Flow Chemistry and Continuous Processing:

- Methodology: Polymerization is conducted in a continuous flow reactor rather than a traditional batch reactor. Parameters like flow rate, residence time, and reagent concentrations are adjusted to control the molecular weight distribution [2].

- Advantages: Enables the continuous production of polymers with customized molecular weight distributions and allows for in-situ mixing of different polymer fractions [2].

- Limitations: Cannot be easily adapted to all polymer architectures, such as polymer brushes [2].

Troubleshooting Common Dispersity Issues in RAFT Polymerization

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for Dispersity Control in RAFT

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions & Reagent Adjustments |

|---|---|---|

| Dispersity too high | - Slow initiation or re-initiation [6]- Inefficient RAFT agent- High termination rate- Incorrect solvent or temperature | - Ensure the R-group of the RAFT agent is a good leaving group and re-initiates rapidly [6]- Increase the ratio of [RAFT] to [Initiator] to reduce the fraction of chains formed by initiator-derived radicals [6]- Optimize temperature and solvent to favor the main RAFT equilibrium [9] |

| Cannot achieve low Đ (<1.3) | - Poor choice of RAFT agent for the monomer [6]- Impurities in the system- Side reactions (e.g., chain transfer to polymer) | - Select a RAFT agent where the Z-group is appropriate for the monomer family (e.g., dithioesters for methacrylates) [6]- Rigorously purify monomers and solvent; degas solutions to remove oxygen- For acrylic monomers, consider lower temperatures to minimize side reactions |

| Inconsistent Đ between batches | - Variable impurity levels- Inaccurate dosing of reagents- Fluctuations in temperature control | - Establish strict purification and handling protocols- Use precise syringes or balances for small-volume/high-dilution reagents- Use a temperature-controlled reactor with consistent stirring |

| Broadening of Đ during chain extension | - Low end-group fidelity of the macro-CTA- Presence of "dead" chains in the first block | - Characterize the macro-CTA by SEC and NMR to confirm end-group retention before chain extension [5]- Optimize the synthesis of the first block to minimize termination events |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions for RAFT

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Dispersity Control in RAFT Polymerization

| Reagent / Material | Function & Importance | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| RAFT Agent (CTA) | The core control agent. The Z-group controls the reactivity of the C=C bond; the R-group must be a good leaving group and re-initiating radical. | Dithioesters (e.g., CDB) for (meth)acrylates. Trithiocarbonates for wider monomer scope. Switchable CTAs for tuning Đ in situ [9] [6]. |

| Radical Initiator | Source of primary radicals to start the polymerization. | AIBN and ACVA are common thermal initiators. Concentration must be kept low relative to RAFT agent for low Đ [6]. |

| Solvent | Medium for the reaction. Can affect the rate of propagation and the RAFT equilibrium. | Choice (e.g., water, DMF, dioxane, ACN) can be used to control dispersity in switchable systems [9]. Must be purified. |

| Monomer | The building block of the polymer. Purity is critical. | (Meth)acrylates, acrylamides, styrene, vinyl acetate, etc. Must be purified to remove inhibitors and protic impurities [6]. |

| Acid/Base Additives | Used in switchable RAFT systems to perturb the RAFT equilibrium and actively control dispersity. | e.g., Acid addition in aqueous/organic solvent mixtures can be used to target specific Đ values [9]. |

Troubleshooting Logic for Dispersity Issues

Reversible Addition-Fragmentation chain Transfer (RAFT) polymerization is a powerful form of Controlled Radical Polymerization (CRP) [10]. Since its discovery in 1998, it has become a versatile method for synthesizing polymers with precise architectures [6] [10]. Its key advantage lies in its exceptional tolerance for a wide range of functional groups and monomers, allowing researchers to design complex polymers for applications from drug delivery to materials science [11] [12].

At the heart of this technique is the RAFT agent, which mediates a dynamic equilibrium between actively growing chains and dormant ones. This process enables control over molecular weight and, crucially, the dispersity (Đ, a measure of molecular weight distribution), which is a central theme in advanced polymer research [9] [13].

The Core RAFT Mechanism

The RAFT process incorporates all the steps of a conventional free-radical polymerization—initiation, propagation, and termination—with the addition of a crucial reversible chain-transfer process mediated by the RAFT agent [6] [10].

The following diagram illustrates the key equilibrium that confers "living" characteristics to the polymerization.

The mechanism proceeds through several key stages [6] [12]:

- Initiation & Propagation: A standard radical initiator (e.g., AIBN) generates a primary radical that reacts with monomer, beginning the growth of an active polymer chain (Pn•).

- RAFT Pre-equilibrium: The active chain (Pn•) adds to the thiocarbonylthio group of the RAFT agent. The resulting intermediate radical fragments, releasing a new radical (R•) and forming a dormant polymeric RAFT species.

- Re-initiation: The released R• must be a good leaving group and efficient at re-initiating polymerization, starting a new active chain (Pm•).

- Main RAFT Equilibrium: This is the central, repetitive cycle that confers control. Active chains of any length (Pm•) rapidly exchange with dormant polymeric RAFT chains (Pn-S-C(Z)=S-R). This equilibrium allows all chains to grow at a similar rate, leading to low dispersity.

This "living" character is preserved in the major product, which has the R-group from the RAFT agent on the α-end and the thiocarbonylthio group on the ω-end, allowing for further chain extension or block copolymer synthesis [12] [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components for RAFT

A standard RAFT polymerization requires only a few key components, but their careful selection is critical to success [6].

| Component | Key Function | Critical Considerations & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| RAFT Agent (CTA) | Mediates the reversible chain transfer; primary controller of molecular weight and dispersity. | Z-group stabilizes the C=S bond. R-group must be a good leaving/ re-initiating group. Choice depends entirely on the monomer [11] [10]. |

| Radical Initiator | Provides a steady, low flux of primary radicals to initiate chains. | Common thermally-activated initiators include AIBN and ACVA. Concentration is typically 5-10x lower than RAFT agent to minimize dead chains [6] [10]. |

| Monomer | The building block of the polymer chain. | Must be capable of free-radical polymerization. RAFT is compatible with (meth)acrylates, (meth)acrylamides, styrene, vinyl acetate, and more [11] [10]. |

| Solvent | Provides the reaction medium. | Can be bulk, organic solvent, or water. Must solubilize all components. Choice can influence dispersity control [9] [10]. |

The table below outlines the essential compatibility between the RAFT agent's structure and the monomer family, which is the most critical decision in experimental design [11] [10].

| Monomer Family | Example Monomers | Recommended RAFT Agent (General) |

|---|---|---|

| More-Activated Monomers (MAMs) | Styrene, (Meth)acrylates, (Meth)acrylamides, Acrylonitrile | Dithioesters, Trithiocarbonates |

| Less-Activated Monomers (LAMs) | Vinyl acetate, N-Vinylpyrrolidone | Xanthates (MADIX), Dithiocarbamates |

Controlling Dispersity in RAFT Polymerization

While achieving low dispersity is a classic goal of RAFT, modern research focuses on actively tailoring dispersity over a wide range to tune material properties [9] [13]. The following diagram and table summarize key strategies.

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Experimental Parameters to Tune | Achievable Dispersity (Đ) Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Switchable RAFT Agents [9] [11] | The CTA's structure/activity is altered by an external stimulus (e.g., pH), changing its control over the polymerization. | Amount of acid/base; solvent composition; targeted Degree of Polymerization (DP). | 1.16 - 1.58 (in pure aqueous media); can be broader with organic solvent. |

| Mixed CTAs [13] | Using two CTAs with different transfer constants creates populations of chains growing at different rates. | Molar ratio of the two CTAs; their relative transfer activities. | Tunable from low (~1.1) to high (~2.0+) unimodal distributions. |

| Intermittent Initiator Feeding [13] | New chains are initiated at different times, leading to a distribution of chain lengths. | Initiator addition rate and timing. | Allows for precise tailoring of the dispersity profile. |

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

My polymerization has high dispersity (Đ > 1.5). What went wrong?

This is a common issue with several potential causes:

- Incorrect RAFT Agent: Ensure your RAFT agent's Z and R groups are appropriate for your monomer family (see Table 2) [11] [10]. Using a CTA for LAMs on a MAM will lead to poor control.

- Initiator Ratio Too High: A high concentration of initiator relative to the RAFT agent increases the proportion of "dead" chains from termination, broadening the distribution. Solution: Reduce the initiator concentration (typically to 1/5 to 1/10 of [RAFT]) [10].

- Slow Fragmentation: If the R-group is a poor leaving group, the intermediate radical may undergo side reactions. Solution: Select a RAFT agent where R is a good homolytic leaving group for your monomer (e.g., cyanalkyl groups for methacrylates) [11].

My reaction is slow or doesn't start. How can I troubleshoot this?

- Oxygen Inhibition: Oxygen is a potent radical scavenger. Solution: Ensure thorough deoxygenation of your solution via freeze-pump-thaw cycles or nitrogen/argon sparging [14].

- Incorrect Temperature: The initiator may not be decomposing at a sufficient rate. Solution: Confirm the half-life temperature of your initiator (e.g., AIBN is commonly used at 60-80°C) [10].

- Poor Re-initiation: If the R-group radical is not reactive enough, it won't start new chains efficiently, leading to an inhibition period. Solution: Refer to selection guides to choose an R-group that is a good re-initiating radical for your monomer [11] [6].

Are there methods to perform RAFT polymerization without deoxygenation?

Yes, recent advances have led to oxygen-tolerant RAFT systems. One robust method is the methylene blue (MB+)/triethanolamine (TEOA) system under red light [14].

- Protocol Summary: In an open-to-air vial, prepare your reaction mixture with monomer, RAFT agent, MB+ (e.g., 150 µM), and TEOA (e.g., 20 mM) in water/DMSO or pure water. Irradiate with red light (λmax = 640 nm). This metal-free system can achieve high conversion with low dispersity (Đ < 1.3) in the presence of air [14].

How can I install specific functional groups at the chain end of my polymer?

The ω-end thiocarbonylthio group is a versatile handle for post-polymerization modification [12] [10].

- Azide-Termination Example: You can synthesize an azide-functionalized RAFT agent or initiator (Az-ACVA). After polymerization, the polymer possesses an azide group at its α-end, allowing for efficient "click" conjugation with alkyne-containing molecules (e.g., dyes, targeting ligands) [12].

- General Method: The thiocarbonylthio group can be aminolyzed, reduced, or reacted under other mild conditions to introduce thiols, aldehydes, or other bio-orthogonal functionalities [10].

What is Dispersity?

In polymer science, dispersity (Đ), also known as the polydispersity index (PDI), is a measure of the breadth of the molecular weight distribution within a polymer sample. It is defined as the ratio of the weight-average molecular weight (Mw) to the number-average molecular weight (Mn) [15]. Unlike small molecules, which typically have a single, well-defined molecular weight, polymers are composed of chains of varying lengths, making them heterogeneous mixtures [15]. The dispersity index quantifies this heterogeneity.

- Đ = 1.0: Indicates a monodisperse system where all polymer chains are of identical length (theoretical ideal) [8].

- Đ > 1.0: Indicates a polydisperse system with a broad distribution of chain lengths. Most synthetic polymers fall into this category [15] [8].

The PDI is a critical parameter because it significantly influences key material properties, including mechanical strength, thermal stability, solubility, and processability [9] [16]. Controlling dispersity is, therefore, a fundamental aspect of tailoring polymers for specific applications, from everyday commodity plastics to high-performance precision plastics.

Dispersity in Commodity vs. Precision Plastics

The required dispersity differs significantly between commodity and precision plastics, reflecting their distinct functional roles.

Commodity Plastics (e.g., Polyethylene (PE), Polypropylene (PP), Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC)) are mass-produced for high-volume, cost-sensitive applications like packaging, containers, and household goods [17] [18] [19]. They are designed for basic mechanical strength and thermal stability. For these materials, broader dispersity is often acceptable and can even be beneficial for processability, such as in extrusion or injection molding.

Precision Plastics (or Engineering Plastics), such as Polycarbonate (PC), Polyamide (Nylon), and Polyetheretherketone (PEEK), are designed for demanding applications in automotive, aerospace, electronics, and medical devices [17] [18] [19]. They require superior mechanical strength, heat resistance, chemical stability, and predictable long-term performance. For these materials, narrow dispersity is often crucial. A narrow molecular weight distribution ensures consistent and reliable properties, as it minimizes the presence of very low molecular weight chains that can act as plasticizers and weaken the material, or very high molecular weight chains that can cause processing difficulties [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for Dispersity Control

Controlling dispersity requires specific reagents and techniques. The following table outlines key materials used in controlled polymerization, particularly RAFT.

Table 1: Key Reagents for Controlled Dispersity in RAFT Polymerization

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Switchable RAFT Agent | A chain transfer agent (CTA) whose activity can be toggled using external stimuli (e.g., acid), allowing real-time control over the growth of polymer chains and the final dispersity [9]. | Used to produce polymers with a tunable dispersity range (e.g., Đ 1.16 to 1.58) by varying acid addition in aqueous media [9]. |

| Monomer | The building block of the polymer chain (e.g., N-Vinylpyrrolidone for making PVP) [16]. | The purity and controlled addition of monomer are essential for achieving predictable molar mass and low dispersity. |

| Initiator | A molecule that starts the polymerization reaction (e.g., AIBN - 2,2'-Azobis(isobutyronitrile)) [16]. | Must be used in the correct ratio with the RAFT agent to maintain control over the polymerization. |

| Solvent System | The medium in which the polymerization occurs. The choice of solvent can significantly impact the degree of control and the achievable dispersity [9]. | Acetonitrile (ACN) was found to be highly effective, requiring low acid to achieve narrow dispersity (Đ ~1.19) [9]. |

| Chain Transfer Agent (CTA) | A general term for agents, like RAFT agents, that regulate chain growth and help control molecular weight and dispersity [16]. | Xanthate derivatives (e.g., XMe, XAr, XCOOH) are used in RAFT/MADIX polymerization to control the architecture of PVP [16]. |

Experimental Protocols for Dispersity Control and Analysis

Controlling Dispersity via Switchable RAFT Agents

Methodology Summary: This protocol describes using a switchable RAFT agent to synthesize polymers with tailored dispersity, as demonstrated in recent literature [9].

Detailed Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Dissolve the monomer, switchable RAFT agent, and initiator in a chosen solvent. Common solvents include pure water, DMF-water mixtures, or acetonitrile (ACN).

- Polymerization Initiation: Purge the reaction mixture with an inert gas (e.g., Nitrogen or Argon) to remove oxygen. Heat the mixture to the required temperature to activate the initiator (e.g., 60-70°C for AIBN).

- Dispersity Control: To achieve low dispersity (Đ ~1.2), add a specific amount of acid (e.g., 2 equivalents in ACN) during the reaction. The acid modulates the activity of the RAFT agent, promoting uniform chain growth.

- Achieving High Dispersity: To synthesize a polymer with broader dispersity, reduce or omit the acid addition. This allows for a less uniform polymerization process, resulting in a wider molecular weight distribution.

- Termination and Purification: After the desired reaction time, cool the mixture and precipitate the polymer into a non-solvent. Isolate the polymer via filtration or centrifugation and dry it under vacuum.

Key Parameters:

- Targeted Degree of Polymerization (DP): Dispersity control is effective for a wide range of DPs (e.g., from 50 to 800) in aqueous media. In organic solvent mixtures, control may be limited to lower DPs (e.g., up to 200) [9].

- Solvent Choice: The required amount of acid and the achievable dispersity range are highly solvent-dependent. ACN was identified as particularly efficient [9].

Formulating Amorphous Solid Dispersions (ASDs) for Drug Delivery

Methodology Summary: This protocol outlines the preparation of ASDs using well-defined polymers synthesized by RAFT, highlighting the impact of polymer dispersity on drug stability [16].

Detailed Procedure (Ball Milling):

- Material Preparation: Weigh the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), such as Curcumin (CUR), and the synthesized polymer (e.g., Polyvinylpyrrolidone - PVP) in the desired ratio.

- Milling: Place the powder mixture in a ball mill jar with grinding balls.

- Processing: Mill the mixture for a predetermined time (e.g., several hours) at a specific frequency to induce mechanical alloying and form a homogeneous amorphous mixture.

- Analysis: Characterize the resulting ASD using Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) to confirm the absence of API crystallinity and to determine the glass transition temperature (Tg).

Alternative Method (Solvent Evaporation):

- Dissolution: Dissolve both the API and the polymer in a volatile common organic solvent.

- Evaporation: Remove the solvent rapidly under reduced pressure or by spray drying to form a solid amorphous matrix.

- Analysis: As above, use DSC to verify the formation of the ASD.

Role of Dispersity: Using PVP with low dispersity synthesized via RAFT allows for a clearer understanding of the structure-property relationships in ASDs, such as the impact of chain-end functionality and molar mass on drug solubility and stability, compared to using commercial PVP with broader dispersity [16].

Measuring Dispersity using Gel Permeation Chromatography/Size-Exclusion Chromatography (GPC/SEC)

Methodology Summary: GPC/SEC is the primary technique for determining the molar mass distribution and dispersity of polymers [15].

Detailed Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve the polymer sample in an appropriate eluent (e.g., THF) at a specific concentration. Allow sufficient time for complete dissolution, which can range from hours to days, especially for high molar mass or broad dispersity samples [15].

- Chromatography: Inject the solution into the GPC/SEC system, which consists of a column packed with porous beads.

- Separation: As the solution passes through the column, smaller polymer chains penetrate deeper into the pores and take longer to elute, while larger chains are excluded and elute first.

- Detection: Use a concentration-sensitive detector (e.g., Refractive Index detector) to measure the amount of polymer eluting at each volume. For absolute molar mass determination, couple the system with a multi-angle laser light scattering (MALLS) detector [15].

- Data Analysis: Construct a calibration curve using polymer standards of known molar mass. Calculate the number-average (Mn) and weight-average (Mw) molar masses, and compute the dispersity (Đ = Mw/Mn).

Critical Consideration: When setting up a GPC/SEC method, the column set must have a sufficient separation range to cover the entire molar mass distribution of the sample. For a polymer with a dispersity of 2, the column's upper exclusion limit should be at least 10 times the sample's weight-average molar mass (Mw) to avoid artificial shoulders in the chromatogram [15].

Table 2: Impact of Dispersity on GPC/SEC and Light Scattering Analysis

| Polymer Characteristic | Impact on GPC/SEC Analysis | Impact on Light Scattering Detection |

|---|---|---|

| Narrow Dispersity (Đ ~1.1) | Easier column selection; requires a smaller separation range. | A Right-Angle Laser Light Scattering (RALLS) detector may be sufficient if the entire sample consists of isotropic scatterers (size < λ/20). |

| Broad Dispersity (Đ > 1.5) | Requires a column with a very wide separation range (high exclusion limit) to avoid inaccurate results [15]. | A Multi-Angle Laser Light Scattering (MALLS) detector is often necessary, as the high molar mass fractions will be anisotropic scatterers, which RALLS underestimates [15]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why can't I achieve narrow dispersity (Đ < 1.2) in my RAFT polymerization, even with a switchable agent? A: This is a common challenge. First, verify your solvent system. The efficiency of acid-based switching is highly solvent-dependent. For instance, switching is very effective in acetonitrile (ACN) but may require more acid or not work as well in other solvents like DMAc [9]. Second, ensure your targeted degree of polymerization (DP) is within a controllable range; for non-aqueous systems, control can be lost at high DPs (e.g., >200) [9]. Finally, check for potential side reactions or impurities that could deactivate the RAFT agent.

Q2: How does polymer dispersity affect the performance of lipid-based drug delivery systems? A: While not a polymer property, the polydispersity index (PDI) of lipid nanoparticles is equally critical. A high PDI indicates a broad particle size distribution, which can lead to inconsistent cellular uptake, unpredictable drug release profiles, and variable in vivo behavior. For instance, only nanocarriers with a small, uniform size (≤150 nm) can effectively extravasate through the leaky vasculature of tumors [20]. A low PDI is therefore essential for batch-to-batch reproducibility and clinical efficacy.

Q3: My GPC/SEC results show a shoulder at the high molecular weight end. Is this a problem with my polymer or my method? A: This is a classic symptom of a column set with an insufficiently high exclusion limit. If the pores in the column are too small to accommodate the largest polymer chains in your sample, those chains will all elute together at the void volume, creating an artificial shoulder. This cannot be corrected by data processing. You must select a column or column combination with a broader separation range that can fully resolve your sample's molar mass distribution, especially if it has broad dispersity [15].

Q4: When should I use a MALLS detector instead of a RALLS detector with my GPC system? A: The choice depends on the size and dispersity of your polymer. RALLS detectors provide correct molar masses only for "isotropic scatterers," typically small, compact molecules (size < λ/20). For synthetic polymers with broad dispersity, a significant portion of the sample (the high molar mass "tail") will be large enough to scatter light anisotropically. For these samples, a MALLS detector is required to obtain accurate molar mass data across the entire distribution [15].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common Problems in Dispersity-Control Experiments

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Inability to control dispersity in RAFT | - Incorrect solvent [9]- Targeted DP too high [9]- Impurities or side reactions | - Switch to an optimal solvent like ACN.- Lower the targeted DP and scale up.- Ensure high-purity reagents and strict anaerobic conditions. |

| Poor dissolution of polymer for GPC/SEC | - Insufficient dissolution time- Molar mass too high- Broad dispersity | - Allow more time for dissolution (hours to days) [15].- Gently agitate but avoid ultrasonication, which can degrade chains.- For broad dispersity samples, the high-Mw fractions need the longest to dissolve. |

| Broad or unpredictable dispersity in block copolymers | - Poor end-group fidelity from previous block- Incomplete purification between steps | - Characterize the first block's end-group fidelity by mass spectrometry before chain extension [9].- Improve purification techniques (e.g., reprecipitation, dialysis) to remove dead chains. |

| Irreproducible drug release from ASDs | - Variable polymer dispersity between batches- Drug crystallization upon storage | - Use polymers with low and consistent dispersity for predictable drug-polymer interactions [16].- Analyze Tg of the ASD; a higher Tg (antiplasticization) improves physical stability. |

Key Data and Visualizations

Quantitative Data on Dispersity Control

The following table summarizes experimental data from recent studies on controlling polymer dispersity, providing a reference for expected outcomes.

Table 4: Experimental Data for Dispersity Control via Switchable RAFT Agents [9]

| Solvent System | Acid Equivalents | Achieved Dispersity (Đ) | Targeted DP | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure Aqueous Media | Varied | 1.16 - 1.58 | 50 to 800 | Dispersity controllable regardless of DP in water. |

| [DMF]:[H2O] = 4:1 | Varied | Tailored up to DP=200 | 50 to >200 | Loss of dispersity control for DP > 200. |

| Acetonitrile (ACN) | 2 | ~1.19 | Not Specified | Most efficient solvent; lowest acid required. |

| Dioxane, DMSO | Varied | Efficient Control | Not Specified | Successful dispersity control achieved. |

| DMAc | Varied | Less Efficient | Not Specified | Side reactions observed due to high acid amounts. |

Workflow Diagram for Dispersity-Tailored Polymer Synthesis

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow for synthesizing polymers with tailored dispersity and their subsequent application in drug formulation.

Dispersity Impact on Material Properties and Analysis

This diagram summarizes how dispersity influences both the final properties of a plastic and the choices made during its analytical characterization.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

FAQ 1: How does the structure of the RAFT agent influence the polymerization control and dispersity?

The RAFT agent's structure is paramount for exerting control over the polymerization and the properties of the resulting polymer. The choice of the Z-group and R-group directly impacts the stability of intermediate radicals, the rate of addition and fragmentation, and the final molecular weight distribution [6].

- Problem: Poor control over molecular weight and high dispersity (Đ) values.

Solution: Select a RAFT agent whose Z- and R-groups are optimized for your specific monomer.

- The Z-Group's Role: This group primarily affects the stability of the C=S bond and the intermediate radical. For example, phenyl groups (as in dithiobenzoates) enhance the stability of the adduct radical, which can lead to rate retardation but offers good control for monomers like styrene and acrylates. Less stabilizing groups, like in xanthates, are better suited for less active monomers such as vinyl acetate [6].

- The R-Group's Role: This group must be a good leaving group, able to stabilize a radical sufficiently to facilitate fragmentation from the intermediate, but also reactive enough to efficiently re-initiate polymerization. A good R-group radical should be similar in reactivity to the propagating polymer radical [6].

Problem: Rate retardation, particularly with certain RAFT agents.

- Solution: Understand that rate retardation is often linked to the stability of the RAFT adduct radical (Pn-S-C•(Z)-S-Pm). If this radical is too stable, it reduces the concentration of active propagating chains (Pm•), slowing the overall polymerization rate [6]. This is more common with RAFT agents featuring radical-stabilizing Z-groups (e.g., dithiobenzoates) and monomers that produce less stable propagating radicals. Switching to a trithiocarbonate may mitigate this issue [6] [21].

FAQ 2: My monomer does not polymerize in a controlled manner. What is the issue?

Not all monomers are equally suitable for every RAFT agent. The monomer's inherent reactivity dictates the necessary reactivity of the RAFT agent's R-group.

- Problem: Failure to achieve low dispersity or targeted molecular weight with a specific monomer.

- Solution: Match the RAFT agent to the monomer family.

- Active Monomers (e.g., styrenes, acrylates, methacrylates, acrylamides): These require RAFT agents with activated R-groups, such as cyanoalkyl or benzyl groups (e.g., cumyl dithiobenzoate or cyanoisopropyl dithiobenzoate) [6].

- Less Active Monomers (e.g., vinyl acetate, N-vinylpyrrolidone): These require more active R-groups, such as xanthates or dithiocarbamates, where the R-group is a good leaving group like –OEt or –NEt₂ [6].

FAQ 3: How do solvent and temperature affect the outcome of a RAFT polymerization?

Solvent and temperature are critical reaction parameters that influence kinetics, monomer solubility, and the RAFT equilibrium itself.

- Problem: Inconsistent results between different solvents, including issues with monomer solubility and phase separation.

Solution: Prioritize solvent selection based on monomer solubility and compatibility with the RAFT agent. A recent automated study highlighted this challenge, noting that poor solubility of a fluorescein acrylate (FluA) comonomer in toluene caused issues in automated feeding. The study successfully switched to dimethyl formamide (DMF) to ensure solubility and reproducible dosing [22]. Furthermore, the solvent can influence the position of the RAFT equilibrium and the rate of fragmentation steps.

Problem: Inability to control the reaction rate or polymer tacticity.

- Solution: Utilize temperature as a precise control knob. Increasing the temperature generally favors the fragmentation of the RAFT adduct radical, increasing the polymerization rate [6]. Research has also shown that temperature can be used to control polymer tacticity, as demonstrated in the photoiniferter RAFT polymerization of vinyl acetate, where temperature adjustments altered solvent-monomer hydrogen bonding [23].

FAQ 4: How can I deliberately synthesize polymers with broader dispersity?

While low dispersity is often a goal, there are applications where a broader molecular weight distribution is desirable.

- Problem: Need to synthesize polymers with tailored, wide dispersity.

- Solution: Employ a mixture of chain-transfer agents (CTAs) with different activities. A 2020 study described a versatile method where mixing two CTAs or catalysts of different activity in RAFT polymerization enabled the preparation of homopolymers and block co-polymers with a wide range of dispersity values [7]. This approach provides a systematic way to tailor the molecular weight distribution, moving beyond the traditional focus on narrow dispersity.

The following table summarizes key parameters and their quantitative or qualitative impact on RAFT polymerization outcomes.

Table 1: Key Influencing Factors and Their Impact on RAFT Polymerization

| Factor | Specific Parameter | Impact on Polymerization/Polymer Properties | Experimental Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| RAFT Agent Structure | Z-Group (e.g., -Ph, -OR, -NR₂) | Determines C=S bond reactivity and intermediate radical stability; influences rate retardation and control [6]. | A phenyl Z-group (dithiobenzoate) offers good control for styrene/acrylates but may cause retardation. |

| R-Group (Leaving Group) | Must be a good re-initiating radical; matching R-group reactivity to monomer type is critical for control [6]. | For (meth)acrylates, use tertiary cyanoalkyl R-groups (e.g., from AIBN-derived fragments). | |

| Monomer | Reactivity (e.g., Styrene vs. Vinyl Acetate) | Dictates the required activity of the RAFT agent's R-group [6]. | High reactivity monomers require less active R-groups. Low reactivity monomers require more active R-groups (xanthates). |

| Solvent | Polarity & Solubility | Affects monomer/RAFT agent solubility, the position of the RAFT equilibrium, and can prevent phase separation [22]. | Poor solvent choice can lead to clogging and inconsistent feeding in automated systems [22]. |

| Temperature | Reaction Temperature | Higher temperatures increase the rate of initiator decomposition, propagation, and fragmentation of the RAFT intermediate [6]. | Can be used to control reaction rate and, in some cases, polymer tacticity [23]. |

| Initiator | Concentration relative to CTA | A lower initiator-to-CTA ratio reduces the proportion of "dead chains" formed by termination, preserving the "livingness" of the polymer [12]. | A typical ratio is [CTA]:[I] = 10:1 or higher, to ensure most chains are CTA-derived [12]. |

Experimental Protocol: Tuning Dispersity by Mixing Chain-Transfer Agents

This protocol is adapted from a 2020 study for preparing polymers with tailored dispersity [7].

Objective: To synthesize a polymer with a controlled, non-uniform molecular weight distribution by using a mixture of two RAFT agents with different transfer activities.

Materials:

- Monomer of choice (e.g., a common acrylate or styrene derivative).

- Two RAFT agents (CTAs) with the same functional group but different R- or Z-groups designed to have high and low chain-transfer activity, respectively.

- Thermal initiator (e.g., AIBN or ACVA).

- Anhydrous solvent (e.g., toluene, DMF), chosen for its ability to dissolve all reagents.

Methodology:

- Solution Preparation: In a sealed vessel under inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen or argon), prepare a reaction mixture containing the monomer, solvent, thermal initiator, and a predetermined mixture of the high-activity and low-activity RAFT agents. The molar ratio of the two CTAs will be the primary variable for controlling the final dispersity.

- Polymerization: Place the reaction vessel in a heated bath or block at the appropriate temperature (e.g., 60-70 °C for AIBN) to initiate the polymerization. Allow the reaction to proceed for a predetermined time or until a target conversion is reached.

- Monitoring: Withdraw aliquots at regular intervals to monitor monomer conversion (e.g., by 1H NMR spectroscopy) and molecular weight evolution (by Size Exclusion Chromatography, SEC).

- Termination and Purification: Once the target conversion is achieved, cool the reaction mixture to room temperature. Expose the solution to air to quench the radicals. Recover the polymer by precipitation into a non-solvent and dry it under vacuum.

Key Considerations:

- The choice of CTA pair is critical and should be informed by kinetic parameters such as the chain-transfer coefficient.

- The ratio of the two CTAs in the mixture directly dictates the breadth of the molecular weight distribution. A 50:50 mixture will produce a broader dispersity than a 95:5 mixture.

Visual Workflow: Interplay of Factors in RAFT Dispersity Control

The diagram below illustrates the logical relationship between the four key influencing factors and how they converge to determine the properties of the final polymer, with a focus on dispersity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for RAFT Polymerization Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Specific Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Chain Transfer Agent (CTA) | Mediates the controlled chain growth via reversible chain transfer; defines the α- and ω-chain ends [6]. | Dithioesters (e.g., CPDB), Trithiocarbonates (e.g., TTC), Xanthates [6]. |

| Radical Initiator | Provides a source of free radicals to initiate the polymerization process [6]. | AIBN (thermal), ACVA (thermal, water-soluble), Photoredox catalysts (e.g., ZnTPP for PET-RAFT) [6] [23]. |

| Functional Monomers | The building blocks of the polymer; choice determines polymer properties and functionality. | Standard: Benzyl acrylate (BA), Oligo(ethylene glycol) acrylate (OEGA). Functional: Fluorescein o-acrylate (FluA) [22]. |

| Solvents | Dissolves reagents, enables heat transfer, and can influence reaction kinetics. | Toluene, THF, DMF (chosen for solubility and boiling point) [22]. |

| Azide-Functionalized Reagents | Enables precise post-polymerization modification via click chemistry for bioconjugation [12]. | Azide-derivatized CTA (Az-CTA) or initiator (Az-ACVA) [12]. |

Advanced Techniques for Tunable Dispersity: From Switchable Agents to Scalable Processes

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the primary function of a switchable RAFT agent? A switchable RAFT agent is a specialized chain transfer agent that allows for the controlled polymerization of both "more-activated monomers" (MAMs) and "less-activated monomers" (LAMs). Its behavior is altered by an external stimulus, most commonly the addition of an acid. In its neutral form, it effectively controls the polymerization of LAMs. Upon the addition of one equivalent of a strong acid, its character changes, making it effective for controlling the polymerization of MAMs. This switchability is key to synthesizing block copolymers containing both MAM and LAM segments, which is difficult with conventional RAFT agents [24] [25].

Q2: Why is controlling dispersity important in polymer design? Dispersity (Đ), a measure of the breadth of a polymer's molecular weight distribution, significantly affects material properties and their subsequent applications. A lower dispersity indicates a more uniform polymer chain length, which is crucial for achieving consistent mechanical, thermal, and self-assembly behavior. Controlling dispersity allows researchers to fine-tune these properties for specific uses, such as in drug delivery, coatings, and advanced materials [9] [26].

Q3: My switchable RAFT agent is not effectively controlling polymerization in a high DP target. What could be wrong? The effectiveness of dispersity control with switchable RAFT agents is highly dependent on the targeted degree of polymerization (DP) and the solvent system. If you are targeting a high DP (e.g., above 200), the solvent choice is critical. For instance, while aqueous media can provide excellent dispersity control from DP 50 to DP 800, solvent mixtures like DMF:Water (4:1) may only successfully tailor dispersity up to DP 200. For higher DPs, switching to a solvent like acetonitrile (ACN) might be necessary [9].

Q4: I am observing side reactions in my polymerization. Could the solvent be the cause? Yes. Some solvents can interact with the high amounts of acid required for the switching process. For example, when using DMAc as a solvent, side reactions have been observed, which are attributed to the high acid concentration [9]. It is recommended to use alternative solvents such as dioxane, DMSO, or ACN, which have been shown to provide efficient control over dispersity without reported side reactions under these conditions [9].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor control over MAM polymerization | Insufficient acid to trigger the switch | Ensure at least 1 equivalent of a strong acid (e.g., p-toluenesulfonic acid) is added relative to the RAFT agent [24]. |

| Low dispersity control in organic solvent | Suboptimal solvent or acid amount | Switch to ACN, which requires low acid (e.g., 2 equivalents for Đ ~1.19); avoid problematic solvents like DMAc [9]. |

| Inability to achieve high dispersity values | High acid content or incorrect solvent | For high Đ, reduce acid amount and use pure aqueous media or specific organic solvent mixtures (e.g., [DMF]:[H₂O] = 4:1) [9]. |

| Failure to form block copolymers | Macro-RAFT agent lacks fidelity | Synthesize the first block with high end-group fidelity by using optimal conditions; confirm fidelity via mass spectrometry [9]. |

| Control loss at high DP (>200) | Inefficient solvent system for high DP | Perform polymerizations in pure aqueous media for broad DP range (50-800) or use ACN for better control at higher DPs [9]. |

Table 1: Troubleshooting common problems in switchable RAFT polymerization.

Quantitative Data for Experimental Design

Effect of Solvent and Acid on Dispersity

| Solvent System | Acid Equivalents | Typical Dispersity (Đ) | Notes / Targeted DP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pure Aqueous Media | Varying addition | 1.16 - 1.58 | Effective for a wide DP range (50 to 800) [9]. |

| [DMF]:[H₂O] = 4:1 | Varying addition | Broader range possible | Dispersity control successful only up to DP 200 [9]. |

| Acetonitrile (ACN) | 2 | ~1.19 | Requires the lowest amount of acid for low dispersity [9]. |

| Dioxane | Not Specified | Efficient control | No major side reactions reported [9]. |

| DMSO | Not Specified | Efficient control | No major side reactions reported [9]. |

| DMAc | High amounts | Side reactions | Not recommended due to side reactions with high acid [9]. |

Table 2: How solvent composition and acid equivalents influence the resulting polymer dispersity.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Tuning Dispersity in Aqueous Media for a Broad DP Range

This protocol is adapted from the study demonstrating that dispersity can be efficiently controlled in pure aqueous media regardless of the targeted degree of polymerization (from DP 50 to DP 800) [9].

- Solution Preparation: In a reaction vial, dissolve the chosen monomer and the switchable RAFT agent (e.g., an N-(4-pyridinyl)-N-methyldithiocarbamate) in pure deionized water.

- Acid Addition: Vary the addition of a strong acid (e.g., p-toluenesulfonic acid). The amount added will determine the final dispersity, with a range from 1.16 to 1.58 achievable.

- Initiation: Add a radical initiator (e.g., V-70 or ACVA) and purge the reaction mixture with an inert gas (N₂ or Ar) to remove oxygen.

- Polymerization: Seal the vial and place it in a heated bath or block at the appropriate temperature for the initiator (e.g., 60-70°C) for the required time to reach high conversion.

- Purification: After polymerization, precipitate the polymer into a cold non-solvent (e.g., diethyl ether or hexanes) and isolate it by filtration or centrifugation.

- Analysis: Analyze the polymer by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) to determine the molecular weight distribution and dispersity.

Protocol 2: Low-Dispersity Polymerization in Acetonitrile (ACN)

This protocol utilizes ACN, which requires the lowest amount of acid to achieve very low dispersity values [9].

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve the monomer and the switchable RAFT agent in anhydrous acetonitrile.

- Acid Addition: Add 2 equivalents of a strong acid (relative to the RAFT agent) to the solution. This amount has been shown to yield dispersities around 1.19.

- Initiation & Polymerization: Add the radical initiator, purge with inert gas, and allow the reaction to proceed as described in Protocol 1.

- Work-up: Precipitate and purify the polymer as before.

- Analysis: Characterize the final polymer via SEC and mass spectrometry to confirm low dispersity and high end-group fidelity.

Mechanism and Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: The switching mechanism of a pyridyl-based RAFT agent.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for tuning dispersity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Switchable RAFT Polymerization |

|---|---|

| N-(4-pyridinyl)-N-methyldithiocarbamates | The switchable RAFT agent. Controls LAM polymerization in its neutral form and MAM polymerization in its protonated form [24] [25]. |

| Strong Organic Acid (e.g., p-toluenesulfonic acid) | The switching trigger. Protonates the pyridyl group on the RAFT agent, changing its reactivity from suitable for LAMs to suitable for MAMs [24]. |

| More-Activated Monomers (MAMs) | Monomers with conjugated double bonds (e.g., styrenics, acrylates, acrylonitrile). Polymerization is controlled by the protonated (switched) form of the RAFT agent [24]. |

| Less-Activated Monomers (LAMs) | Monomers where the double bond is adjacent to a heteroatom (e.g., vinyl acetate, N-vinylpyrrolidone). Polymerization is controlled by the neutral form of the RAFT agent [24]. |

| Acetonitrile (ACN) | An optimal organic solvent for achieving low dispersity (e.g., Đ ~1.19) with a low required amount of acid [9]. |

| Radical Initiator (e.g., ACVA) | The source of radicals to initiate the polymerization chain process [24]. |

Table 3: Essential reagents and their roles in experiments with switchable RAFT agents.

Metered Addition of Chain Transfer Agents (CTAs) for MWD Shape Control

The Molecular Weight Distribution (MWD), also referred to as dispersity (Đ), is a fundamental characteristic of polymers that profoundly influences their physical properties and processability. While narrow MWDs are often targeted for fundamental studies, broad and tailored MWDs are crucial for many industrial and high-performance applications, influencing characteristics such as mechanical strength, melt rheology, and microphase separation behavior [2]. Controlled radical polymerization techniques, such as Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain-Transfer (RAFT), offer a versatile platform for synthesizing polymers with complex architectures. The metered addition of Chain Transfer Agents (CTAs) has emerged as a powerful synthetic strategy to precisely control both the breadth and the shape of the MWD, moving beyond the narrow distributions typically associated with these methods [27]. This guide provides troubleshooting and best practices for researchers aiming to implement this technique within the broader context of controlling dispersity in RAFT polymerization.

Core Concepts and Key Reagents

What is the relationship between CTA addition and MWD shape?

In a conventional RAFT polymerization with a single charge of CTA, the reaction proceeds in a controlled manner, typically yielding a polymer with a narrow molecular weight distribution (Đ ≈ 1.1-1.3). In contrast, metering the CTA during the polymerization creates populations of polymer chains that begin growing at different times. Chains initiated early in the process grow for a longer period, resulting in higher molecular weights. Chains initiated later by the added CTA grow for a shorter time, resulting in lower molecular weights. By carefully controlling the addition rate and profile of the CTA, one can dictate the relative proportion of chains growing at different times, thereby directly designing the shape—whether symmetric, or skewed high or low—of the final MWD [2].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below summarizes key materials and their functions in metered CTA experiments.

Table: Essential Reagents for MWD Shape Control via Metered CTA

| Reagent | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Chain Transfer Agent (CTA) | The core reagent used to control molecular weight and initiate new polymer chains. Its metered addition dictates the MWD shape. |

| Monomer | The building block of the polymer. Its consistent feeding may also be required to maintain reaction kinetics. |

| Initiator | Generates free radicals to start the polymerization process. Must be chosen for compatibility with the RAFT process. |

| Solvent | Provides the reaction medium. Must be inert and appropriately chosen for the monomer and polymer solubility. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: Metered CTA Addition in Batch RAFT

The following protocol is adapted from established methods for tailoring MWDs in RAFT polymerizations [27].

- Step 1: Reaction Setup. In a typical experiment, a Schlenk flask or sealed reactor is charged with the monomer, solvent, and a portion of the CTA. The mixture is degassed via several freeze-pump-thaw cycles or by sparging with an inert gas (e.g., N₂ or Ar) to remove oxygen.

- Step 2: Initiating Polymerization. The reaction is heated to the desired temperature with constant stirring. The initiator (e.g., a thermal initiator like AIBN) is added to commence the polymerization.

- Step 3: Metered CTA Addition. A solution of the CTA in solvent (and potentially additional initiator) is prepared in a separate, sealed vessel. This solution is added to the main reaction mixture gradually over a prolonged period using a syringe pump or other metering device. The addition profile (rate, timing) is the key variable for MWD control.

- Step 4: Reaction Quenching & Purification. After the monomer conversion has reached the desired level (and the CTA addition is complete), the reaction is cooled and exposed to air to quench the polymerization. The polymer is isolated by precipitation into a non-solvent and dried under vacuum.

Quantitative Data for Experimental Design

The table below summarizes data from published studies demonstrating the achievable range of dispersity through CTA feed ratio and metered addition.

Table: Dispersity Control via CTA Feed Ratios in Different Polymerization Systems

| Polymerization System | Monomer | Key Control Parameter | Achievable Dispersity (Đ) Range | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAFT (Metered CTA) | Styrene (model) | CTA addition rate/profile | ~1.17 to 3.9 | [2] |

| Cationic RAFT | Vinyl Ethers | Metered CTA addition | Tailored MWD breadth and shape | [27] |

| Organocatalyzed ROP | Ethylene Oxide | [MeOH]₀/[MTFA]₀ feed ratio | 1.05 to 2.05 | [13] |

| Organocatalyzed ROP | Propylene Oxide | [MeOH]₀/[MTFA]₀ feed ratio | 1.05 to 1.69 | [13] |

Experimental Workflow for Metered CTA Addition

Troubleshooting FAQs

The observed MWD is broader/narrower than predicted. What could be wrong?

- Incorrect Addition Rate: The calculated MWD profile is highly sensitive to the CTA addition rate. A faster-than-intended addition will result in a narrower distribution, while a slower addition will lead to a broader one. Solution: Calibrate your syringe pump or metering device before the experiment to ensure accurate flow rates.

- Fluctuations in Addition Rate: Pulsatile or inconsistent flow from the addition system can create multimodal or abnormally broad distributions. Solution: Ensure all fluidic connections are secure and use a high-precision pump designed for continuous, pulseless flow.

- Side Reactions or Poor CTA Fidelity: If the CTA is not efficient or decomposes under reaction conditions, its consumption will not lead to the efficient re-initiation of new chains, invalidating the kinetic model. Solution: Confirm the purity and stability of your CTA. Choose a CTA with a high re-initiation rate constant (kiT ≥ kp) for the monomer in use to avoid retardation [28].

My MWD is multimodal instead of monomodal. How can I fix this?

Multimodality is a classic sign of improper mixing or discrete, rather than continuous, initiation events.

- Poor Mixing: If the added CTA solution is not rapidly and homogeneously distributed throughout the reaction mixture, localized zones of high CTA concentration will form, leading to bursts of new chain initiation and multiple distinct chain populations. Solution: Optimize stirring efficiency. Consider using a reactor design with enhanced mixing, such as a stirred cell with baffles or, for flow systems, implementing static mixers or leveraging Taylor dispersion for homogenization [29].

- Incorrect CTA Transfer Constant: If the transfer constant (Ctr) of the CTA is too high (>>1), it will be consumed immediately upon addition, creating a distinct batch-like effect with each addition. If it is too low (<<1), it will accumulate and may lead to a sudden burst of initiation later. Solution: Select a CTA with a transfer constant close to 1 for "ideal" behavior, where the [T]:[M] ratio remains relatively constant, minimizing broadening of the distribution [28]. Incremental monomer addition can also help maintain a constant [T]:[M].

How does the choice of CTA impact the final MWD shape?

The chemical structure of the CTA is a critical variable.

- Transfer Constant (Ctr): As per the Mayo equation, the degree of polymerization is inversely related to Ctr × [T]/[M] [28]. A CTA with a high Ctr will be highly effective at limiting molecular weight but may be consumed too quickly, making fine control over the MWD shape difficult. A CTA with a low Ctr will require higher concentrations and may lead to broader-than-desired distributions at high conversion.

- Addition-Fragmentation Efficiency: The CTA must rapidly fragment after addition to the propagating chain end to generate the new initiating radical. Slow fragmentation can lead to retardation and poor control.

- Re-initiation Efficiency: The radical generated from the CTA must be highly reactive and able to re-initiate polymerization at a rate comparable to or greater than propagation (kiT ≥ kp). If kiT < kp, the polymerization will be retarded, and the MWD may broaden uncontrollably [28].

CTA Troubleshooting Logic Map

Within modern polymer science, controlling the dispersity (Đ)—a measure of the distribution of molecular weights in a polymer sample—is a fundamental goal. Precise control over this parameter allows researchers to tailor polymer properties for specific applications, from drug delivery to advanced materials manufacturing. Photoinduced Electron/Energy Transfer-Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain Transfer (PET-RAFT) polymerization has emerged as a powerful "green" technique that offers exceptional command over molecular weight, dispersity, and polymer architecture. Recent breakthroughs have successfully scaled this once lab-bound method to industrial-relevant volumes using sunlight as an energy source, marrying precision with sustainability [30] [31] [32]. This technical support center addresses the key experimental challenges and provides proven methodologies for implementing these advances in your research.

Core Technology: Sunlight-Driven PET-RAFT

PET-RAFT polymerization combines the precise control of RAFT chemistry with the energy of light. A photocatalyst, upon absorbing light, enters an excited state that can transfer energy or an electron to a RAFT agent. This interaction triggers a reversible activation-deactivation cycle, maintaining a low concentration of growing radicals and enabling control over the polymerization.

Diagram 1: The PET-RAFT polymerization mechanism involves a photocatalyst that, when excited by light, activates the dormant RAFT species, allowing for controlled chain growth.

The PPh₃-CHCP Photocatalyst Breakthrough

A major advancement in scalable PET-RAFT is the development of the heterogeneous photocatalyst PPh₃-CHCP (conjugated cross-linked phosphine). This material addresses critical limitations of previous catalysts [30] [31]:

- Broad Wavelength Absorption: Functions effectively under various light sources, including blue light, white light, and natural sunlight.

- Heterogeneous Nature: Can be easily separated from the reaction mixture via filtration and reused without significant loss of catalytic efficiency.

- Robust Stability: Resists structural deterioration under high-intensity sunlight irradiation.

- Favorable Redox Potential: With a reduction potential (Eox*) of -1.35 V, it can effectively reduce common chain transfer agents like BTPA (Ered = -0.6 V) [31].

Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sunlight-Driven PET-RAFT

| Reagent/Material | Function/Role | Key Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Photocatalyst | Absorbs light and activates RAFT agent | PPh₃-CHCP (Heterogeneous, recyclable) [30] [31] |

| Chain Transfer Agent (CTA) | Controls chain growth and molecular weight | BTPA, CPADB [31] |

| Monomer | Polymer building block | Methyl Acrylate (MA), others [30] |

| Solvent | Reaction medium | DMSO used in scale-up studies [31] |

| Deoxygenation System | Removes inhibitory oxygen | Freeze-pump-thaw cycles or nitrogen bubbling [31] |

Large-Scale Experimental Protocols

Sunlight-Driven Polymerization at 2-Liter Scale

This protocol is adapted from the successful scale-up to 2 L using direct sunlight irradiation, achieving 93% conversion of methyl acrylate (MA) with a dispersity (Đ) of 1.13 [30] [31] [32].

Reagents:

- Monomer: Methyl Acrylate (MA)

- Chain Transfer Agent (CTA): BTPA

- Photocatalyst: PPh₃-CHCP (2 mg per mL of reaction volume)

- Solvent: DMSO

Procedure:

- Reactor Setup: Use a transparent, flat-bottomed 2 L reactor to maximize sunlight exposure and penetration.

- Charge Reactor: Add MA, BTPA ([M]/[CTA] = 200:1 for ~17 kg/mol polymer), and DMSO to the reactor.

- Add Catalyst: Disperse the calculated amount of PPh₃-CHCP photocatalyst into the solution.

- Deoxygenate: Purge the reaction mixture with nitrogen gas for 30-45 minutes. Alternatively, for smaller volumes, use freeze-pump-thaw cycles.

- Initiate Polymerization: Place the reactor under direct sunlight. The reaction typically reaches high conversion (>90%) within a few hours.

- Monitor Reaction: Track monomer conversion over time using techniques such as 1H NMR spectroscopy.

- Terminate and Purify: Once the desired conversion is reached, stop the reaction by blocking sunlight. Separate the heterogeneous PPh₃-CHCP catalyst by filtration. Recover the polymer by precipitating the filtrate into a non-solvent (e.g., hexane or methanol), followed by drying under vacuum.

White Light-Driven Polymerization at 6-Liter Scale

For environments with unreliable sunlight, white LED light serves as a controllable and effective alternative, demonstrated at a 6 L scale [30] [31].

Procedure: The procedure mirrors the sunlight-driven process, with the following key differences:

- Light Source: Utilize a high-intensity white LED array.

- Reactor Design: For optimal light penetration in large volumes (e.g., 6 L), consider a flow reactor or a reactor with a large surface-area-to-volume ratio.

- Typical Outcome: This setup has yielded 91% MA conversion with a dispersity (Đ) of 1.27, demonstrating excellent control even at a very large scale [30] [31].

Performance Data and Control

The effectiveness of the PPh₃-CHCP catalyzed PET-RAFT is demonstrated by its performance across different molecular weight targets.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of PPh₃-CHCP Catalyzed PET-RAFT under Blue Light [31]

| [M]/[CTA] | Time (h) | Conversion (%) | Theoretical Mn (g/mol) | Achieved Mn (g/mol) | Dispersity (Đ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50:1 | 9 | 97 | 4,400 | 4,500 | 1.08 |

| 100:1 | 9 | 97 | 8,600 | 8,400 | 1.08 |

| 200:1 | 9 | 97 | 16,900 | 17,000 | 1.07 |

| 400:1 | 8 | 92 | 31,900 | 35,000 | 1.10 |

| 1000:1 | 6 | 90 | 77,700 | 75,800 | 1.17 |

The data shows a linear relationship between theoretical and achieved molecular weights with low dispersity values, confirming high livingness and control throughout the polymerization.

Troubleshooting Guide (FAQs)

Q1: My polymerization rate is slow, even in sunny conditions. What could be wrong?

- Catalyst Loading: Verify the concentration of PPh₃-CHCP. The standard is 2 mg/mL of reaction volume. Too little catalyst will slow the reaction significantly [31].

- Light Penetration: Ensure your reaction vessel is clear and positioned for maximum light exposure. For very large scales (>2L), consider reactor geometry or internal lighting.

- Oxygen Contamination: Oxygen is a potent inhibitor. Confirm your deoxygenation method (nitrogen bubbling or freeze-pump-thaw) is thorough. Using a sealed system is recommended.

Q2: How can I control the dispersity (Đ) of my polymers?

- Chain Transfer Agent (CTA) Selection and Ratio: The structure of the CTA's Z and R groups and the [M]/[CTA] ratio are primary tools for controlling molecular weight and dispersity [33].

- Introducing a Chain Transfer Agent (for ROP): For ring-opening polymerization (ROP) of epoxides, research shows that introducing an editable chain-transfer agent like trifluoroacetate (TFA) can tailor dispersity from 1.05 to 2.00. The dispersity increases with the feed ratio of the TFA chain-transfer agent [13].

Q3: The polymer I obtained has a higher dispersity than expected. How can I improve it?

- Check Catalyst Activity: If the photocatalyst has been reused multiple times, test its activity. PPh₃-CHCP is stable, but performance can eventually decline.

- Minize Termination: While PET-RAFT suppresses termination, it is not eliminated. Using a lower concentration of radical initiator (if used) relative to CTA can reduce the proportion of dead chains and lower dispersity [12] [33].

- Verify CTA Purity: Ensure your RAFT agent is pure and has been stored correctly, as degradation can lead to loss of control.

Q4: Can I reuse the PPh₃-CHCP photocatalyst, and how?

- Yes. A key advantage of PPh₃-CHCP is its reusability. After the polymerization is complete, simply filter the reaction mixture to recover the solid catalyst. Wash it with an appropriate solvent (e.g., acetone or DCM) and dry it before using it in a subsequent polymerization. Studies show it can be reused without a significant decrease in efficiency [30].

Q5: I am working with a functional monomer. Will this method work?

- Likely yes. The PPh₃-CHCP system has shown success with various monomers. The versatility also depends on choosing the correct RAFT agent for your monomer family (e.g., trithiocarbonates for more-activated monomers like acrylates, or xanthates for less-activated monomers) [33]. Test on a small scale first.

The integration of sunlight as a sustainable energy source with the precise control of PET-RAFT polymerization marks a significant leap toward green and industrially viable polymer synthesis. The development of robust, heterogeneous photocatalysts like PPh₃-CHCP provides researchers with the tools to perform large-scale reactions with excellent control over molecular weight and dispersity. By leveraging the protocols and troubleshooting guidance provided, scientists can overcome common experimental hurdles and contribute to the advancement of precision polymer manufacturing.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Dispersity Issues in RAFT Polymerization

This section addresses frequent challenges researchers face when trying to control dispersity (Đ) in Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain-Transfer (RAFT) polymerization for block copolymer synthesis.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Dispersity Control in RAFT Polymerization

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| High or uncontrollable dispersity in aqueous media | Incorrect acid addition or solvent composition | Vary acid addition in pure aqueous media to achieve a dispersity range of 1.16-1.58. | [9] |

| Inability to control dispersity for high DPs (Degree of Polymerization) in organic solvent mixtures | Using solvent systems unsuitable for long chains | For targeted DP > 200, avoid [DMF]:[H2O] = 4:1 mixtures. Use acetonitrile (ACN) which allows control even at DP 800. | [9] |

| High dispersity and side reactions in DMAc solvent | High amounts of acid leading to side reactions | Avoid DMAc when high acid concentration is needed. Switch to alternative solvents like dioxane, DMSO, or ACN. | [9] |

| Difficulty achieving low dispersity (Đ) | Suboptimal reaction conditions (factor interactions) | Use Design of Experiments (DoE) to optimize factors like temperature, time, monomer/RAFT agent ratio (RM), and initiator/RAFT agent ratio (RI). | [34] |

| Broadened molar mass distribution in final polymer | Inaccurate interpretation of dispersity (Đ) value | Remember that the standard deviation (Sn) of the distribution increases with molecular weight even at constant Đ. Two polymers with identical Đ but different Mn have very different distribution breadths. | [5] |

| Inefficient chain extension or blocking | Dead chains from termination or incorrect RAFT agent selection | Ensure the R-group of the RAFT agent is a good re-initiating radical for the second monomer. For ATRP or NMP, use macroinitiators to improve blocking efficiency. | [5] [6] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why should I care about controlling dispersity if my main goal is self-assembled nanostructures? Dispersity is not just a number indicating purity; it fundamentally influences self-assembly outcomes. While one might assume lower dispersity always leads to more uniform nanostructures, research shows this is not necessarily true. Increasing the dispersity of the core-forming block in a block copolymer can, counterintuitively, lead to a reduction in the overall dispersity of the resulting nanoparticles. This unravels the fundamental role of the molecular weight distribution's shape and introduces it as a new tool for tuning particle properties [35].

Q2: What is the most effective way to optimize multiple reaction parameters for low dispersity? The conventional "one-factor-at-a-time" (OFAT) approach is inefficient and can miss important factor interactions. Instead, use Design of Experiments (DoE). DoE is a statistical approach that systematically explores the entire experimental space (e.g., varying temperature, time, and concentration ratios simultaneously) to build accurate prediction models. This allows you to find optimal reaction conditions with fewer experiments and understand how factors interact to affect responses like conversion, Mn, and dispersity [34].

Q3: Which solvents are best for controlling dispersity with switchable RAFT agents? The solvent choice is critical. While aqueous media provide good control across a wide DP range (50-800), organic solvents offer different advantages. Acetonitrile (ACN) has been identified as particularly effective, requiring the lowest amount of acid to achieve low dispersity values (e.g., ~1.19 with 2 acid equivalents). Dioxane and DMSO also perform well, while DMAc should be used with caution due to potential side reactions with high acid amounts [9].

Q4: How does dispersity in one block affect the morphology of a block copolymer in the bulk state? Polydispersity influences nearly every aspect of diblock copolymer self-assembly in the melt. Increasing the dispersity of one block can lead to several effects:

- An increase in the lattice constant or domain size.

- An increase in interfacial thickness between domains.

- Induction of phase transitions (e.g., from spheres to cylinders).

- A change in the order–disorder transition (ODT) temperature [36].