Conducting Polymers in Electronics: Pioneering Sustainable LEDs and Advanced Photovoltaics

This article provides a comprehensive review for researchers and scientists on the application of conducting polymers in light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and photovoltaic cells.

Conducting Polymers in Electronics: Pioneering Sustainable LEDs and Advanced Photovoltaics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review for researchers and scientists on the application of conducting polymers in light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and photovoltaic cells. It explores the foundational principles of conductive organic materials, detailing their unique electronic structures and the mechanisms behind their optical and electrical properties. The scope extends to advanced synthesis techniques, device architecture, and integration strategies for both OLED displays and third-generation solar cells. The content critically addresses key challenges in stability and scalability while presenting optimization methodologies. A comparative analysis validates the performance of polymer-based devices against conventional technologies, highlighting their transformative potential for flexible, lightweight, and sustainable electronic applications.

The Molecular Foundation of Conducting Polymers: From Discovery to Electronic Structure

The discovery that polymers, traditionally considered insulators, could conduct electricity fundamentally reshaped the landscape of materials science and electronics. This breakthrough centered on polyacetylene, a simple conjugated polymer that, when properly doped, could achieve metallic levels of conductivity. The pioneering work of Hideki Shirakawa, Alan G. MacDiarmid, and Alan J. Heeger in the mid-1970s unveiled this transformative potential, earning them the 2000 Nobel Prize in Chemistry [1] [2]. Their discovery did not merely introduce a new class of materials; it bridged the conceptual gap between the worlds of plastics and metals, launching the field of organic electronics and enabling the development of technologies ranging from flexible transparent conductors to organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) and biomedical sensors [3] [4].

This article situates the discovery of conductive polyacetylene within the broader context of research on conducting polymers for LEDs and photovoltaic cells. We detail the historical accident that led to the synthesis of processable polyacetylene films, the critical experiments that revealed their exceptional electronic properties, and the subsequent development of experimental protocols that have become foundational to the field.

The Accidental Discovery and Key Experiments

The path to conductive polyacetylene began with a "fortuitous error" in Hideki Shirakawa's laboratory in 1967. A visiting scientist, Hyung Chick Pyun, inadvertently used a catalyst concentration that was a thousand times too high while attempting to polymerize acetylene [2] [5]. Instead of the typical unprocessable black powder, this mistake yielded a beautiful, silvery, freestanding polyacetylene film with a metallic luster [5]. This serendipitous synthesis was the crucial first step, as it provided a polyacetylene sample in a form suitable for detailed physical and chemical experimentation [6].

The pivotal collaboration began when Shirakawa met Alan MacDiarmid in Tokyo. MacDiarmid, who was working on the inorganic metallic polymer (SN)ₓ, became intrigued upon learning about Shirakawa's silvery organic film [2]. He invited Shirakawa to the University of Pennsylvania, where he and physicist Alan Heeger were conducting research. This interdisciplinary partnership—between a synthetic chemist (Shirakawa), an inorganic chemist (MacDiarmid), and a physicist (Heeger)—proved to be immensely fruitful.

Their key experiment involved exposing the trans-polyacetylene film to iodine vapor (oxidative doping) [2]. When one of Heeger's students measured the conductivity of the iodine-doped film, they observed a staggering increase—the conductivity had jumped by a factor of ten million compared to the pristine film, achieving a conductivity of up to 10³ S/cm [1] [2] [4]. This single experiment demonstrated that an organic polymer could exhibit conductivity comparable to that of metals. The team published their landmark findings in 1977, announcing the synthesis of electrically conducting organic polymers to the world [5].

Table 1: Key Properties of pristine and Iodine-Doped Polyacetylene Films

| Property | Pristine cis-rich film | Pristine trans-rich film | Iodine-Doped trans film |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrical Resistivity | 2.4 x 10⁸ Ω·cm [6] | 1.0 x 10⁴ Ω·cm [6] | ~10⁻³ Ω·cm (Conductivity ~10³ S/cm) [4] |

| Energy Gap | 0.93 eV [6] | 0.56 eV [6] | Not Applicable (Metallic behavior) |

| Appearance | Copper-coloured [2] | Silvery [2] | Not Specified |

The Molecular Basis of Conductivity

The exceptional electronic properties of polyacetylene and other conductive polymers arise from their unique molecular structure:

- Conjugated Backbone: Polyacetylene consists of a linear chain of carbon atoms with alternating single (σ) and double (π) bonds. This conjugation creates a system where the π-electrons are delocalized across the entire chain, forming a one-dimensional electronic band [2] [4].

- Doping: The pristine polymer is a semiconductor. Doping is the critical process that dramatically enhances conductivity. It involves either oxidation (removing electrons, p-type) or reduction (adding electrons, n-type). In the case of the seminal experiment, oxidation with iodine (I₂) created positively charged sites (holes) along the polymer chain [2].

- Charge Carriers: Upon doping, the polymer backbone undergoes structural changes. The resulting charge carriers are not free electrons as in a metal, but quasiparticles such as polarons and solitons. These are radical cations (or anions) coupled with a local lattice distortion, which can move rapidly along the polymer chain when an electric field is applied [2].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The discovery of conductive polyacetylene was made possible by specific experimental protocols, which have since been refined and become standard in the field.

Synthesis of Polyacetylene Films via the Shirakawa Method

This protocol describes the synthesis of freestanding polyacetylene films, a crucial enabling technique [6] [5].

- Primary Reagents: Acetylene gas (monomer), Ziegler-Natta catalyst (e.g., Ti(OBu)₄ / Al(Et)₃ in an organic solvent like toluene).

- Procedure:

- Catalyst Preparation: Under a strict inert atmosphere (e.g., in a glovebox or using Schlenk techniques), prepare a concentrated solution of the Ziegler-Natta catalyst in toluene.

- Film Formation: Pour the catalyst solution into a reaction vessel. Do not stir. Instead, allow the solution to remain quiescent.

- Polymerization: Introduce acetylene gas into the vessel at a controlled pressure and temperature (e.g., -78°C to room temperature). A polyacetylene film will begin to form on the surface of the catalyst solution.

- Harvesting: After a predetermined reaction time (minutes to hours), carefully remove the resulting freestanding film from the solution.

- Washing: Repeatedly wash the film with an appropriate solvent (e.g., toluene, followed by methanol) to remove any residual catalyst.

- Drying: Dry the film under vacuum to constant weight. The morphology (cis/trans ratio) can be controlled by varying the polymerization temperature [2].

Chemical Doping of Polyacetylene Films

This protocol outlines the process of enhancing the electrical conductivity of the synthesized films through chemical doping [2].

- Primary Reagents: Freestanding polyacetylene film, doping agent (e.g., iodine crystals for p-type, sodium vapor for n-type).

- Procedure:

- Setup: In a sealed glass apparatus (e.g., a two-legged reactor under vacuum), place the pristine polyacetylene film in one leg and the solid doping agent (e.g., I₂) in the other.

- Doping: Cool the leg containing the doping agent (e.g., with liquid N₂) and evacuate the entire system. Isolate the system from the vacuum line.

- Vapor Exposure: Allow the doping agent leg to warm to room temperature, causing its vapor to fill the chamber and contact the polyacetylene film.

- Reaction Monitoring: Observe a rapid color change in the film, indicating the doping reaction. For iodine, the silvery film turns a golden-bronze color.

- Completion: The doping process can be controlled by varying the exposure time and vapor pressure of the dopant. The reaction is typically rapid (seconds to minutes).

- Characterization: The doped film can be removed for conductivity measurements, which typically show an increase in conductivity of many orders of magnitude.

Table 2: Common Doping Agents and Their Effects on Polyacetylene

| Doping Type | Doping Agent | Chemical Reaction | Effect on Conductivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative (p-type) | Iodine (I₂) | [CH]ₙ + 3x/2 I₂ → [CH]ₙˣ⁺ + x I₃⁻ [2] | Increase of up to 10⁹ times [2] |

| Oxidative (p-type) | Bromine (Br₂) | Not Specified | Similar to Iodine (High increase) [3] |

| Reductive (n-type) | Sodium (Na) | [CH]ₙ + x Na → [CH]ₙˣ⁻ + x Na⁺ [2] | Significant increase (n-type conductor) |

Electrical Characterization: Four-Point Probe Measurement

To accurately measure the high conductivity of doped films, a four-point probe technique is essential to eliminate the contribution of contact resistances.

- Equipment: Four-point probe station, DC constant current source, high-impedance voltmeter, sample stage.

- Procedure:

- Sample Mounting: Place the doped polyacetylene film on a flat, insulating stage. Ensure good contact.

- Probe Alignment: Position four equally spaced, collinear probes in contact with the surface of the film.

- Current Application: Apply a known, constant DC current (I) between the two outer probes using the current source.

- Voltage Measurement: Measure the voltage drop (V) between the two inner probes using the voltmeter.

- Calculation: The sheet resistance (Rₛ) can be calculated from I and V, and the bulk conductivity (σ) can be derived if the film thickness (t) is known: σ = 1 / (Rₛ * t).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Conducting Polymer Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Ziegler-Natta Catalyst | A coordination catalyst (e.g., Ti(OBu)₄ / Al(Et)₃) for stereospecific polymerization of acetylene [6]. | Synthesis of polyacetylene films with controllable cis/trans isomeric content [5]. |

| Iodine (I₂) | A strong oxidative (p-type) doping agent that accepts electrons from the polymer backbone [2]. | Used in the seminal doping experiment to dramatically increase polyacetylene conductivity [2]. |

| Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene): Polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS) | A commercially available, water-dispersible conductive polymer complex. PSS acts a counterion and doping agent [3] [7]. | Transparent conductive layers in OLEDs and OPVs; electrochromic devices; bioelectronics [3] [7]. |

| Polyaniline (PANI) | A conductive polymer whose conductivity is highly dependent on both oxidation state and protonation (acid doping) [4]. | Antistatic coatings, corrosion inhibition, printed circuit board manufacturing [2] [4]. |

Impact on Modern Electronics and Future Directions

The discovery of conductive polyacetylene served as the foundation for the entire field of organic electronics. The fundamental principles of conjugation and doping have been applied to a wide range of other polymers, leading to materials with tailored properties for specific applications [3] [8].

The impact is particularly evident in two areas central to the thesis context:

- Light-Emitting Diodes (LEDs): Conjugated polymers like poly(p-phenylene vinylene) (PPV) are used as the active layer in Polymer Light-Emitting Diodes (PLEDs). When an electric current is applied, these semiconductors emit light through electroluminescence, enabling flexible, thin-film displays [2] [4].

- Photovoltaic Cells: In organic solar cells (OPVs), conductive polymers such as poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT) act as electron donors, while fullerene or non-fullerene acceptors act as electron acceptors. This bulk heterojunction architecture efficiently converts light into electricity, offering a path toward low-cost, printable solar panels [3] [7].

Future research continues to build upon this historic breakthrough. The development of conjugated polyelectrolytes (CPEs), which feature ionic side groups, allows for simultaneous electronic and ionic transport, opening new possibilities in bioelectronics and energy storage [8]. Furthermore, the exploration of two-dimensional conjugated coordination polymers (2D c-CPs) promises materials with exceptionally high charge mobility, potentially suitable for advanced hot-carrier applications in optoelectronics [9]. The journey that began with a fortuitous error in a chemistry lab continues to drive innovation at the frontiers of materials science.

The conjugated backbone is the fundamental component of conducting polymers, consisting of a chain of organic molecules with alternating single and double bonds. This structure creates a system of delocalized π-electrons from the overlapping pₓ-orbitals along the polymer chain, which is responsible for the unique electrical and optical properties of these materials [10]. In their pristine, undoped state, conjugated polymers are insulators, but they can achieve significant electrical conductivity through various doping methods, including chemical, electrochemical, or photochemical processes that introduce charge carriers into the π-electron system [10] [7].

The electronic band structure arising from this conjugation creates semiconducting characteristics, with a well-defined highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) separated by a band gap typically within the visible light spectrum [8]. The planar configuration of the backbone allows for optimal π-orbital overlap, forming a delocalized pathway that facilitates charge transport along the polymer chain [8]. The development of conductive polymers represents a significant advancement in materials science, earning the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2000, and has opened avenues for applications in optoelectronics, energy storage, and conversion devices [8] [7].

Band Structure Fundamentals

The electronic properties of conjugated polymers are governed by their band structure, which arises from the quantum mechanical interactions within the π-conjugated system. The highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) represent the valence and conduction band edges, respectively, with their energy separation determining the optical band gap of the material [8].

Backbone engineering through strategic molecular design allows precise tuning of these energy levels. A highly effective approach involves creating donor-acceptor (D-A) architectures by alternating electron-rich (donor) and electron-deficient (acceptor) units along the polymer backbone [8]. This D-A interaction facilitates π-electron delocalization and can lead to the formation of a quinoid resonance structure, effectively reducing the band gap and enhancing electronic properties [8]. Experimental modifications, such as incorporating fluorine or chlorine atoms into the backbone, can further modulate energy levels; fluorination deepens HOMO levels, while chlorination can improve morphological packing and red-shift absorption [8].

Table 1: Fundamental Electronic Properties of Common Conjugated Polymer Backbones

| Polymer | HOMO Level (eV) | LUMO Level (eV) | Band Gap (eV) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEH-PPV | ~ -5.0 | ~ -3.0 | ~ 2.0 | Flexible backbone, higher planarity in solution [10] |

| P3HT | ~ -5.0 | ~ -3.0 | ~ 2.0 | Thiophene-based, prone to torsional disorder [10] |

| Th-BDT Polymer | -5.01 | -3.49 | 1.52 | Donor-acceptor design, high planarity [11] |

| O-BDT Polymer | -5.05 | -3.53 | 1.52 | Alkoxy side chains, moderate planarity [11] |

Charge Transport Mechanisms

Charge transport in conjugated polymers occurs through a complex interplay of intra-chain and inter-chain processes that collectively determine the overall charge carrier mobility.

Intra-chain Charge Transport

Intra-chain transport refers to charge movement along individual polymer chains, where the conjugated backbone provides a pathway for charge delocalization. The efficiency of this process depends critically on the planarity and conformational order of the backbone [10]. Torsional disorder between monomer units disrupts π-orbital overlap, reducing transfer integrals and creating energetic barriers that localize charge carriers [10]. Experimental studies comparing isolated chains of poly(phenylene vinylene) (PPV) and polythiophene derivatives have demonstrated that more planar backbones (like PPV) can exhibit hole mobilities over an order of magnitude higher than those with greater torsional freedom (like polythiophene) [10].

Inter-chain Charge Transport

Inter-chain transport occurs between adjacent polymer chains through π-π stacking interactions and is essential for macroscopic charge transport in thin films [8]. In amorphous organic systems, this process is described by an intermolecular hopping mechanism [12]. The charge hopping rate between molecules can be modeled using Marcus theory, which accounts for electronic coupling, reorganization energy, and energetic disorder [12]. Multiscale simulations of amorphous films reveal that charge mobility is not uniform but broadly distributed over several orders of magnitude due to various trapping mechanisms [12].

Table 2: Charge Transport Properties in Different Polymer Systems

| System/Measurement | Hole Mobility (cm² V⁻¹ s⁻¹) | Electron Mobility (cm² V⁻¹ s⁻¹) | Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated MEH-PPV chains | ~10⁻¹ (microwave freq.) | - | Intra-chain transport only | [10] |

| Isolated P3HT chains | ~10⁻² (microwave freq.) | - | Intra-chain transport only | [10] |

| CBP amorphous film | 4.5×10⁻³ (avg) | 1.6×10⁻³ (avg) | Macroscopic measurement | [12] |

| CBP mobility distribution | 8.5×10⁻³ (max) to 4.6×10⁻⁵ (min) | 4.2×10⁻³ (max) to 3.0×10⁻⁵ (min) | 100 nm film, shows variability | [12] |

| Percolation threshold | - | - | Polymer acceptors have lower thresholds than small molecules | [13] |

Three primary trap types limit charge transport efficiency in disordered organic systems:

- Diagonal traps (Energetic): Arise from site energy differences between molecules due to electrostatic fluctuations or structural heterogeneity [12].

- Off-diagonal traps (Structural): Result from unfavorable molecular packing that reduces electronic coupling between adjacent sites [12].

- Backward hopping traps: Occur when charges hop against the electric field direction, particularly at low fields or in highly disordered regions [12].

Diagram 1: Charge transport pathways and limitations in conjugated polymer systems, showing how intra-chain and inter-chain processes contribute to overall mobility, with torsional disorder and trapping mechanisms as primary limiting factors [10] [12].

Experimental Characterization Methods

Pulse Radiolysis-Time-Resolved Microwave Conductivity (PR-TRMC)

The PR-TRMC technique enables direct measurement of intra-chain charge mobility by eliminating inter-chain contributions [10]. This electrodeless method involves generating charge carriers through pulsed electron beam irradiation of a dilute polymer solution and detecting conductivity changes via microwave absorption [10].

Protocol: PR-TRMC Measurement for Intra-chain Mobility

- Sample Preparation: Prepare dilute polymer solutions (typically ~1 mg/mL) in an appropriate solvent (e.g., benzene) to ensure chain isolation [10].

- Pulse Radiolysis: Irradiate the solution with a short electron beam pulse (e.g., 10-ns pulse of 3-MeV electrons) to generate charge carriers through solvent ionization [10].

- Charge Transfer: Allow positive charges (holes) to transfer to polymer chains via reaction with solvent radical cations [10].

- Microwave Probing: Monitor time-dependent conductivity using microwave frequencies (e.g., ~30 GHz) to detect charge motion along isolated chains [10].

- Mobility Calculation: Determine the charge carrier mobility from the radiation chemical yield of charges and the maximum change in microwave conductivity [10].

Transient Absorption Spectroscopy

Transient absorption spectroscopy probes charge transfer dynamics by monitoring spectral changes following photoexcitation, providing insights into both intra-chain and inter-chain processes [14].

Protocol: Transient Absorption Measurement of Charge Transfer Dynamics

- Sample Preparation: Prepare polymer solutions at various concentrations (e.g., 0.01-1 mg/mL) or thin films to study concentration-dependent effects [14].

- Pump-Probe Setup: Use a nanosecond laser flash photolysis system with a pulsed Nd:YAG laser as the excitation source and a xenon lamp as the probe light [14].

- Spectral Acquisition: Record time-resolved absorption spectra at delays from nanoseconds to milliseconds after excitation [14].

- Feature Identification: Identify characteristic signals including ground-state bleaching (GSB), stimulated emission (SE), and photoinduced absorption (PIA) features [14].

- Kinetic Analysis: Analyze decay dynamics to distinguish between intra-chain (slower decay) and inter-chain (faster decay) processes [14].

Space-Charge-Limited Current (SCLC) Measurements

The SCLC method determines charge carrier mobility in thin films through electron-only or hole-only devices, particularly useful for studying percolation thresholds and impurity effects [13].

Protocol: SCLC Mobility Measurement in Electron-Only Devices

- Device Fabrication: Fabricate electron-only devices with structure ITO/ZnO/Active Layer/PFN-Br/Ag, optimizing active layer thickness (~100 nm) [13].

- J-V Characterization: Measure current density-voltage (J-V) characteristics in the dark, focusing on the space-charge-limited region [13].

- Mobility Extraction: Fit J-V curves to the Mott-Gurney law: ( J = \frac{9}{8} \epsilon \epsilon_0 \mu \frac{V^2}{L^3} ), where μ is mobility, ε is dielectric constant, ε₀ is vacuum permittivity, and L is active layer thickness [13].

- Percolation Analysis: Measure mobility at different acceptor weight fractions to determine the percolation threshold [13].

- Impurity Tolerance Testing: Introduce insulating polymers (e.g., polystyrene) at varying concentrations to simulate degradation effects on electron transport connectivity [13].

Table 3: Comparison of Experimental Techniques for Characterizing Charge Transport

| Technique | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Key Measured Parameters | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR-TRMC | Molecular scale (intra-chain) | Nanoseconds | Intra-chain mobility, radiation chemical yield | Eliminates inter-chain effects; measures isolated chains | Requires specialized radiation source; solution-based |

| Transient Absorption Spectroscopy | Molecular to aggregate scale | Femtoseconds to milliseconds | Excited-state dynamics, charge transfer rates, spectral signatures | Provides detailed kinetic information; identifies species | Complex data interpretation; requires modeling |

| SCLC | Device scale (macroscopic) | Steady-state | Charge carrier mobility, trap density, percolation threshold | Simple device structure; directly relevant to devices | Requires complete devices; assumes ideal SCLC regime |

| Time-of-Flight (TOF) | Device scale (macroscopic) | Microseconds | Charge carrier mobility, transit time, disorder parameters | Measures both electrons and holes; established technique | Requires thick films (>1 μm); may not represent thin-film devices |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Conjugated Polymer Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conjugated Polyelectrolytes (CPEs) | Dual ionic-electronic conductors; interfacial layers | π-conjugated backbone with ionic side groups; tunable energy levels | PFN-Br, PDTzTI [8] [15] |

| Donor-Acceptor Polymers | Low-bandgap semiconductors; photoactive layers | Alternating electron-rich and electron-deficient units; enhanced charge separation | Th-BDT, O-BDT [8] [11] |

| Conjugated Polymer Ligands | Quantum dot surface functionalization; passivation | Strong π-π interactions with surfaces; improved charge transport | Th-BDT with ethylene glycol side chains [11] |

| PEDOT:PSS | Hole transport layer; transparent electrode | High conductivity (>1000 S cm⁻¹); excellent processability | Commercial Clevios products [7] [15] |

| Polymeric Acceptors | Electron transport in all-polymer solar cells | Enhanced electron transport connectivity; lower percolation thresholds | PY-V-γ [13] |

| Reorganization Energy Standards | Reference for charge transfer calculations | Well-characterized λ values for theoretical modeling | Nelsen's four-point method compounds [12] |

Diagram 2: Integrated experimental workflow for comprehensive charge transport analysis in conjugated polymers, combining multiple characterization techniques to elucidate mechanisms across different length scales [10] [14] [12].

Application in Optoelectronic Devices

The relationship between backbone structure, band properties, and charge transport mechanisms directly influences the performance of conjugated polymers in optoelectronic devices. In organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs), charge transport and recombination efficiency in the amorphous emission layer determine device efficiency and lifetime [12]. The broad distribution of charge mobilities in amorphous organic films (spanning up to two orders of magnitude) significantly impacts recombination profiles and contributes to efficiency roll-off at high currents [12].

In organic photovoltaics, charge transport connectivity is a critical factor influencing device stability [13]. Polymer acceptors with extended conjugation lengths form more robust electron transport networks with superior connectivity compared to small molecular acceptors, maintaining higher electron mobilities even under adverse conditions such as impurity incorporation or partial degradation [13]. This enhanced connectivity provides greater tolerance to compositional variations, a key advantage for long-term operational stability [13].

For perovskite solar cells, conjugated polymers serve multiple functions including charge transport layers, interfacial passivants, and electrodes [15]. As electron transport layers (ETLs), n-type conjugated polymers like PDTzTI and PFNDI provide favorable energy level alignment while passivating surface defects through coordination between heteroatoms in the polymer backbone and undercoordized Pb²⁺ ions on the perovskite surface [15]. The planar, conjugated structure enables efficient charge extraction while the polymeric nature improves film formation and processing compatibility.

The conjugated backbone serves as the fundamental building block that dictates the electronic and transport properties of conducting polymers. Through strategic backbone engineering, including donor-acceptor architectures and side-chain functionalization, key parameters such as band gap, energy levels, and intermolecular packing can be precisely controlled to optimize material performance for specific applications. Charge transport occurs through a complex hierarchy of intra-chain and inter-chain processes, with overall mobility often limited by various trapping mechanisms arising from energetic and structural disorder. Advanced characterization techniques, particularly PR-TRMC for intra-chain transport and transient absorption spectroscopy for dynamics, provide crucial insights into these processes across multiple length and time scales. As research progresses, a continued deeper understanding of the structure-property relationships governing conjugated backbones will enable the development of next-generation materials with enhanced performance and stability for advanced optoelectronic and energy applications.

π-Conjugated polymers represent a cornerstone of modern organic electronics, merging the electronic properties of semiconductors with the mechanical flexibility and processability of plastics [16]. Their fundamental structure features alternating single and double bonds along the polymer backbone, leading to a delocalized π-electron system that enables electrical conductivity and optical activity [16]. Among these materials, polyaniline (PANI), polypyrrole (PPy), and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) have emerged as the most technologically significant polymer families, finding extensive applications in photovoltaics, light-emitting diodes, sensors, and energy storage devices [17] [18]. Their utility in optoelectronic devices stems from tunable energy levels, diverse synthesis routes, and the ability to function as both active and interfacial layers [16]. This application note details the properties, synthesis protocols, and photovoltaic applications of these three key polymer families within the context of ongoing research in conducting polymers for energy conversion and storage.

Material Properties and Comparative Analysis

The three polymer families exhibit distinct chemical structures and resulting electronic properties that dictate their specific applications in optoelectronic devices.

Polyaniline (PANI) is characterized by its three distinct oxidation states: leucoemeraldine (fully reduced), emeraldine (partially oxidized), and pernigraniline (fully oxidized) [17]. The emeraldine salt form is electrically conductive, with conductivity that can reach up to 30 S/cm upon doping with protonic acids [17]. PANI demonstrates excellent environmental stability, reversible doping/dedoping chemistry, and remarkable anti-corrosion properties [17].

Polypyrrole (PPy) offers high environmental stability, good electrical conductivity, and biocompatibility [19]. Its conductivity is highly dependent on synthesis conditions and dopants, with reported values typically ranging from 10 to 400 S/cm [19] [20]. PPy is generally insoluble and infusible, presenting processing challenges that are often addressed through the formation of composites and hybrid nanostructures [19].

PEDOT:PSS is a polymer complex where positively charged PEDOT chains are stabilized by negatively charged PSS chains in an aqueous dispersion [21] [22]. This complex exhibits high transparency in the visible region, adjustable electrical conductivity (from 10⁻⁴ to over 4000 S/cm with appropriate treatments), and excellent film-forming properties [18] [22]. The work function of PEDOT:PSS ranges from 5.0 to 5.2 eV, making it particularly suitable as a hole-injection/transport layer [21].

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Key Conducting Polymer Families

| Property | PANI | PPy | PEDOT:PSS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Conductivity Range | 10⁻¹⁰ to 30 S/cm [17] [23] | 10–400 S/cm [19] [20] | 10⁻⁴ to >4000 S/cm [18] [22] |

| Primary Dopants | Protonic acids (HCl, CSA) [17] | Anionic surfactants, FeCl₃, APS [19] | PSS (intrinsic), polar solvents [21] |

| Solubility/Processability | Soluble with functionalized acids [17] | Generally insoluble, requires composites [19] | Excellent water dispersibility [22] |

| Key Advantages | Environmental stability, low cost [17] | High stability, biocompatibility [19] | High transparency, tunable WF [21] |

| Common PV Applications | Hole injection layer, counter electrode [24] [23] [25] | Electrolyte additive, composite electrode [20] | HTL, flexible transparent electrode [21] [22] |

Table 2: Representative Solar Cell Performance Metrics

| Polymer | Device Architecture | Reported Efficiency | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| PANI | Organic PV (P3HT:PCBM) [23] | ~2.5% [23] | Hole injection layer |

| PANI@2D-MoSe₂ | Dye-sensitized Solar Cell [25] | 7.38% [25] | Counter electrode |

| PPy/NL Composite | Dye-sensitized Solar Cell [20] | Optimized at 50% NL [20] | Electrolyte component |

| PEDOT:PSS | Organic Solar Cell [22] | >12% [22] | Flexible electrode |

| PEDOT:PSS | Perovskite Solar Cell [21] | Varies with modification [21] | Hole transport layer |

Experimental Protocols

Synthesis and Fabrication Methods

Electrochemical Synthesis of PANI@2D-MoSe₂ Binary Composite

This protocol describes the synthesis of a PANI and molybdenum selenide composite for use as a high-performance counter electrode in dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs), adapted from established procedures [25].

Materials:

- Aniline monomer

- Hydrochloric acid (HCl, 0.1 M)

- Two-dimensional molybdenum selenide (2D-MoSe₂) synthesized via hydrothermal method [25]

- Fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) conductive glass substrates

Procedure:

- Prepare the electrolyte solution by dissolving 0.3 g of 2D-MoSe₂ in 50 mL of 0.1 M HCl electrolyte solution.

- Dissolve aniline monomer in 0.1 M HCl to achieve a concentration of approximately 0.1 M.

- Set up a standard three-electrode electrochemical cell:

- Working Electrode: FTO glass substrate

- Counter Electrode: Platinum wire or mesh

- Reference Electrode: Standard calomel electrode (SCE) or Ag/AgCl

- Perform electrochemical polymerization using cyclic voltammetry (CV) with the following parameters:

- Potential window: -1.0 V to +2.0 V (vs. reference electrode)

- Scan rate: 50 mV/s

- Number of cycles: 10

- After polymerization, remove the FTO substrate with the deposited PANI@2D-MoSe₂ film.

- Rinse gently with deionized water and dry under ambient conditions or in a vacuum oven at moderate temperature (50-60°C).

Characterization: The resulting composite can be characterized by FE-SEM and HR-TEM to observe the polymer-covered sheet-like morphology, and by XRD to confirm the octahedral crystalline phase [25].

Chemical Oxidative Polymerization of PPy-PEI Hybrid Nanoparticles

This protocol describes the synthesis of hybrid polypyrrole-polyethyleneimine (PPy-PEI) nanoparticles with tunable size and conductivity for potential use in sensors and energy applications [19].

Materials:

- Pyrrole monomer (distilled under vacuum before use)

- Polyethyleneimine (PEI, hyperbranched polymer)

- Iron(III) chloride (FeCl₃, oxidant)

- Hydrochloric acid (HCl, for acidic medium)

- Methanol (for washing)

Procedure:

- Prepare an acidic aqueous solution (e.g., using HCl) as the reaction medium.

- Dissolve PEI template in the acidic solution. The [PEI]/[PY] ratio can be varied to control particle size.

- Add the distilled pyrrole monomer to the solution.

- In a separate container, dissolve FeCl₃ in cold distilled water. The [FeCl₃]/[PY] molar ratio influences yield and conductivity [19].

- Slowly add the oxidant solution to the monomer/PEI solution in a one-step addition without stirring to initiate polymerization.

- Allow the reaction to proceed for 24 hours at room temperature. A black precipitate of PPy-PEI will form.

- Recover the product by filtration.

- Wash the precipitate thoroughly with methanol and water to remove unreacted monomers and oligomers.

- Dry the final product in a vacuum oven at 70°C.

Notes: Particle size (85-300 nm) can be tuned by varying reactant concentrations. Conductivity can range from 0.1 to 6.9 S/cm [19].

Preparation of High-Conductivity PEDOT:PSS Electrodes

This protocol outlines the processing and post-treatment methods for creating PEDOT:PSS films with high electrical conductivity suitable for use as flexible transparent electrodes in solar cells [21] [22].

Materials:

- PEDOT:PSS aqueous dispersion (e.g., Clevios PH1000)

- Conductivity-enhancing solvent additives: Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), ethylene glycol (EG), or sorbitol

- Substrates (glass or flexible PET)

Procedure:

- Solution Formulation: Mix the PEDOT:PSS aqueous dispersion with a conductivity-enhancing additive.

- A typical recommendation is 5-7% v/v of DMSO or EG added to the dispersion [22].

- Stir the mixture thoroughly for several hours to ensure homogeneity.

- Film Deposition: Deposit the formulated solution onto the substrate.

- Spin-coating: A common method for lab-scale devices. Typical spin speeds range from 2000-4000 rpm for 30-60 seconds to achieve films ~30-100 nm thick.

- Other methods like spray-coating, inkjet printing, or doctor blading can also be used.

- Thermal Annealing: Bake the deposited films on a hotplate.

- Typical annealing temperature: 110-140°C

- Typical annealing time: 10-20 minutes

- Post-Treatment (Optional): For further enhancement of conductivity, implement a post-treatment step.

- Acid Treatment: Carefully treat the film with concentrated sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄) for a short duration, followed by thorough rinsing with water [22].

- Solvent Treatment: Dip-coat or drop-cast a secondary solvent like EG or glycerol onto the annealed film, followed by a second annealing step.

Notes: The chosen formulation and processing parameters significantly impact final conductivity, transparency, and mechanical properties. Films prepared with Clevios PH1000 and optimized treatment can achieve conductivities exceeding 1000 S/cm and transmittance >90% at 550 nm [22].

Device Fabrication Workflow

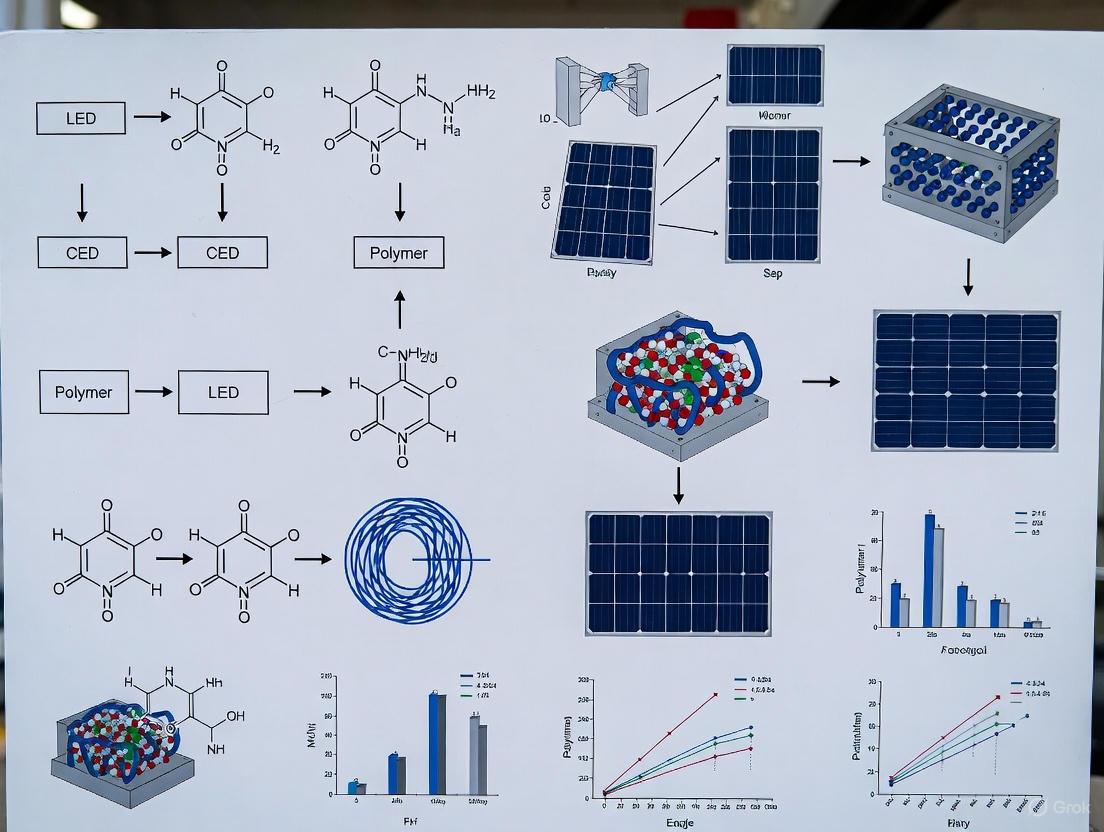

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for fabricating a solution-processed organic or hybrid solar cell, highlighting the integration points for PANI, PPy, and PEDOT:PSS.

Solar Cell Fabrication Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Conducting Polymer-Based Photovoltaics

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS Aqueous Dispersions | Hole transport layer (HTL), flexible transparent electrode [21] [22] | Clevios P VP AI 4083: Standard HTL (1:6 PEDOT:PSS). Clevios PH1000: High-conductivity electrode (1:2.5 PEDOT:PSS) [21]. |

| Polar Solvent Additives | Secondary dopants to enhance PEDOT:PSS conductivity [21] [22] | Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), Ethylene Glycol (EG). Typically added at 5-7% v/v to dispersion. |

| Aniline Monomer | Precursor for PANI synthesis [17] [25] | Requires distillation before electrochemical synthesis to ensure purity. |

| Protonic Acids | Dopants for PANI to achieve conductive emeraldine salt form [17] [23] | Camphorsulfonic Acid (CSA), HCl. Functionalized acids (e.g., CSA) improve solubility [17]. |

| Pyrrole Monomer | Precursor for PPy synthesis [19] [20] | Requires distillation before chemical oxidative polymerization [19]. |

| Chemical Oxidants | Initiators for chemical polymerization of PANI and PPy [19] [20] | Ammonium Persulfate (APS), Iron(III) Chloride (FeCl₃). Choice affects conductivity and yield [19]. |

| FTO/ITO Coated Glass | Transparent conductive substrates for device fabrication [25] | FTO is often preferred for high-temperature processing. |

| High Boiling Point Solvents | Used for post-treatment of PEDOT:PSS films [21] | Glycerol, Sorbitol. Post-treatment can further enhance film conductivity and morphology. |

Performance and Optimization Strategies

PANI in Photovoltaics

PANI serves effectively as a hole injection layer (HIL) in organic photovoltaic cells (OPVCs). Research demonstrates that both water-based and organic solvent-based PANI dispersions can achieve power conversion efficiencies (PCE) of approximately 2.5% in poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT) and [6,6]-phenyl C61 butyric acid methyl ester (PCBM) bulk heterojunction cells [23]. Performance is highly dependent on the conductivity, thickness, and dopant of the PANI film, with optimal results requiring high transparency (>90%) and a conductivity around 10⁻² S/cm [23]. Recent advancements focus on PANI nanocomposites, such as the PANI@2D-MoSe₂ binary composite, which demonstrates superior performance as a counter electrode in DSSCs, achieving an efficiency of 7.38%, significantly outperforming pristine PANI (5.07%) and even Pt (6.61%) in some configurations [25]. This enhancement is attributed to the combined high conductivity and catalytic activity of the composite.

PPy in Energy Applications

PPy's role in photovoltaics often involves its use in composite materials to enhance electrical properties and device performance. For instance, in DSSCs, incorporating PPy into nanolignin (NL)-based electrolytes significantly improves performance compared to pure NL electrolytes [20]. The PPy/NL composite's electrical conductivity is tunable based on the NL content, with a DC conductivity decrease from 2.88 × 10⁻⁵ S/cm to 1.82 × 10⁻⁸ S/cm as the NL concentration increases tenfold [20]. Optimizing the NL ratio to 50% in the composite maximizes DSSC efficiency [20]. PPy's high stability and conductivity make it a valuable component for creating conductive networks within otherwise insulating or semiconducting matrices.

PEDOT:PSS in State-of-the-Art Solar Cells

PEDOT:PSS is the most widely deployed conducting polymer in organic and hybrid photovoltaics, primarily as a hole transport layer (HTL) and flexible transparent electrode [21] [22]. Its high work function (5.0-5.2 eV) enables efficient hole collection, while its aqueous processability allows for facile integration into device architectures [21]. When employed as a flexible electrode in single-junction PSCs, PEDOT:PSS has enabled PCEs exceeding 12% [22]. However, limitations include acidity (potentially corrosive to ITO) and hygroscopicity, which can accelerate device degradation [21]. Optimization strategies focus on:

- Conductivity Enhancement: Using solvent additives (DMSO, EG) and post-treatments (acid, solvent) to achieve conductivities over 1000 S/cm [21] [22].

- Stability Improvement: Employing cross-linking agents, base treatments (KOH, NaOH) to neutralize acidity, and moisture-blocking interlayers [21].

- Work Function Tuning: Modifying with polar solvents or specific dopants (e.g., PSS-Na, PFI) to optimize energy level alignment with the active layer [21].

PANI, PPy, and PEDOT:PSS each offer a unique portfolio of electronic, optical, and processing properties that make them indispensable for research and development in organic and hybrid photovoltaics. PANI provides excellent environmental stability and customizable conductivity through doping. PPy is valued for its high stability and utility in composites. PEDOT:PSS stands out for its high conductivity, transparency, and commercial availability, making it the current material of choice for interfacial layers and flexible electrodes. The continued advancement of these materials hinges on overcoming challenges related to long-term operational stability, parasitic absorption, and further optimization of cost-effective, scalable processing techniques. The development of novel nanocomposites and sophisticated chemical modification protocols, as outlined in this note, will be crucial for enhancing device performance and pushing the boundaries of conducting polymer-based electronics.

Doping, the intentional introduction of impurities into a material, serves as a fundamental paradigm for precisely tuning the electrical properties of semiconductors. In the context of conducting polymers, this process transforms insulating or semiconducting organic materials into conductors with metallic-like performance, enabling their application in organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs), photovoltaic cells, and other advanced electronic devices [26]. The breakthrough discovery that doping could enhance polyacetylene's conductivity by several orders of magnitude earned the 2000 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, establishing conductive polymers as a pivotal research field [26] [27].

This article details the experimental frameworks and mechanistic principles underpinning doping strategies for conducting polymers. We provide application notes and standardized protocols to facilitate the rational design of materials with tailored electronic properties for optoelectronic applications, particularly focusing on organic electronics and energy conversion systems where controlled conductivity is paramount.

Doping Mechanisms and Classifications

Doping in conjugated polymers operates through distinct mechanisms that introduce charge carriers into the π-conjugated backbone, dramatically altering their electronic structure. Unlike inorganic semiconductors where dopants substitutionally replace host atoms, organic semiconductor doping primarily relies on charge transfer reactions [26].

Charge Transfer Mechanisms

p-type doping occurs when the polymer acts as an electron donor, transferring electrons to an acceptor dopant. This leaves behind positively charged holes on the polymer backbone, forming polarons or bipolarons that serve as charge carriers [26]. Common p-type dopants include halogen atoms (e.g., iodine), Lewis acids (e.g., FeCl₃), and organic acceptors like F₄TCNQ (2,3,5,6-tetrafluoro-7,7,8,8-tetracyanoquinodimethane) [28] [26].

n-type doping involves the polymer acting as an electron acceptor, where dopants donate electrons to the polymer backbone, creating negative charge carriers [26]. This process is more challenging due to the instability of n-doped polymers in ambient conditions, but can be achieved using reagents such as sodium naphthalide or N-DMBI [26].

Advanced Doping Strategies

Recent advances have introduced sophisticated doping strategies that overcome thermodynamic limitations:

Coupled Reaction Doping leverages a thermodynamically favorable reaction to drive an otherwise unfavorable doping process. By adding additives that are highly reactive to the reduction product of the dopant, this approach creates a coupled reaction system that significantly improves electron transfer efficiency. For instance, adding Lewis acids like tris(pentafluorophenyl)borane (BCF) to nitroxide derivative dopants can enhance electrical conductivity by 3-7 orders of magnitude [29].

Acid-Triggered Side Chain Cleavage represents an innovative chemical approach where treating a specially designed polymer (POET-T2-COOH) with a strong acid (TfOH) removes insulating side chains, dramatically improving backbone planarity and charge delocalization. When combined with traditional dopants like F₄TCNQ, this "cleavage with doping" approach can boost conductivity by up to 100,000 times compared to conventional doping methods [27].

Experimental Protocols

Bulk Iodine Doping of Titanocene Polyamine

Principle: This protocol utilizes elemental iodine as a p-type dopant for the condensation polymer derived from titanocene dichloride and 2-nitro-1,4-phenylenediamine. The doping process increases bulk conductivity by 10 to over 1,000-fold through charge transfer complex formation [28].

Materials:

- Titanocene polyamine polymer (synthesized from titanocene dichloride and 2-nitro-1,4-phenylenediamine)

- Crystalline iodine (I₂)

- Hydraulic pellet press

- Heating mantle with temperature control

- Impedance analyzer for conductivity measurements

Procedure:

- Polymer Synthesis: Synthesize the titanocene polyamine polymer via classical aqueous interfacial polycondensation of titanocene dichloride and 2-nitro-1,4-phenylenediamine, achieving a molecular weight of approximately 2.4 × 10⁴ g/mol [28].

- Sample Preparation: Grind the polymer to a fine powder and compress into discs using a hydraulic press at standardized pressure.

- Doping Process: Mechanically mix polymer discs with precise amounts of iodine (3-15% by weight). For uniform doping, the mixture can be briefly heated (10-60 seconds) to volatilize iodine and enhance dispersion within the polymer matrix.

- Conductivity Measurement: Measure bulk conductivity using a two-electrode system with an impedance analyzer across a frequency range of 100 Hz to 1 MHz. Calculate conductivity from impedance data accounting for sample dimensions.

- Characterization: Employ FTIR spectroscopy to identify the formation of C-I compounds (band at 664 cm⁻¹) and monitor the shift in Ti-N band from 496 to 473 cm⁻¹, confirming successful doping [28].

Notes: Conductivity increases with iodine concentration up to 10-15% doping level. Heating beyond 60 seconds causes iodine evaporation, progressively reducing conductivity until returning to pre-doped levels after 480 seconds of heating [28].

Coupled Reaction Doping for Polymeric Semiconductors

Principle: This advanced protocol enhances p-type doping efficiency in donor-acceptor copolymers like DPP4T by introducing a coupled reaction system. A Lewis acid additive forms a thermodynamically favorable complex with reduced dopant species, driving complete electron transfer from polymer to dopant [29].

Materials:

- DPP4T polymer (poly(2,5-bis(2-octyldodecyl)-3,6-di(thiophen-2-yl)diketopyrrolo[3,4-c]pyrrole-1,4-dione-alt-thieno[3,2-b]thiophene))

- Nitroxide derivative dopants (e.g., TEMPO)

- Lewis acid additives (e.g., tris(pentafluorophenyl)borane, BCF)

- Anhydrous chlorobenzene or chloroform

- Nitrogen glove box

- Glass substrates

- Spin coater or drop-casting equipment

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare separate solutions of DPP4T (5-10 mg/mL), dopant (molar ratio 0.01-0.9 relative to polymer repeating unit), and Lewis acid additive in anhydrous chlorobenzene within a nitrogen glove box.

- Solution Mixing: Combine dopant and Lewis acid solutions at 1:1 molar ratio, then mix with polymer solution to achieve desired final concentration.

- Film Deposition: Deposit doped polymer films via drop-casting or spin-coating onto cleaned glass substrates under inert atmosphere.

- Film Drying: Slowly dry films under nitrogen protection at room temperature for 12-24 hours to facilitate solvent evaporation and doping process completion.

- Electrical Characterization: Measure electrical conductivity using four-point probe method and Seebeck coefficient with specialized instrumentation.

Notes: The coupled reaction system enables two-electron transfer per dopant molecule, significantly enhancing doping efficiency. Optimal dopant-to-polymer molar ratio is approximately 0.9, achieving conductivities up to 15.5 S/cm in DPP4T systems [29].

Acid-Triggered Side Chain Cleavage Doping

Principle: This innovative approach simultaneously removes insulating alkyl side chains and introduces dopants, dramatically enhancing backbone planarity and charge transport. The process synergistically combines strong acids with primary dopants to achieve unprecedented conductivity levels [27].

Materials:

- POET-T2-COOH polymer (specially designed with cleavable side chains)

- Trifluoromethanesulfonic acid (TfOH) or similar strong acid

- F₄TCNQ dopant

- Anhydrous solvents (chloroform, toluene)

- Nitrogen glove box

- Thermal annealing equipment

Procedure:

- Polymer Design: Utilize POET-T2-COOH polymer incorporating hydrolysable ester groups in side chains and carboxyl groups for enhanced dopant interaction.

- Solution Preparation: Prepare polymer solution in anhydrous chloroform (5-10 mg/mL) and separate solutions of TfOH and F₄TCNQ.

- Sequential Doping: First treat polymer films with TfOH vapor or solution to cleave insulating butyl side chains (releasing isobutylene), converting side chains to hydroxyl groups.

- Primary Doping: Subsequently expose the side chain-modified polymer to F₄TCNQ solution to p-dope the conjugated backbone.

- Post-treatment: Thermally anneal films at 100°C for 1 hour to enhance molecular ordering and remove residual solvents.

Notes: This approach achieves conductivity enhancements of ~100,000× compared to conventional doping of similar polymers. Doped films exhibit exceptional stability, retaining conductivity after 50 days in inert conditions and showing resistance to solvent exposure and thermal degradation [27].

Data Presentation and Analysis

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Doping Methods for Conducting Polymers

| Doping Method | Polymer System | Dopant/Additive | Maximum Conductivity Achieved | Conductivity Enhancement | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk Iodine Doping | Titanocene polyamine | Iodine (3-15 wt%) | Not specified | 10-1,000× | Conductivity increases with iodine concentration up to 10-15%; heating reverses effect due to iodine evaporation [28] |

| Coupled Reaction Doping | DPP4T | TEMPO + BCF (Lewis acid) | 15.5 S/cm | 3-7 orders of magnitude | Enables two-electron transfer; optimal dopant ratio of 0.9; maintains p-type character with high Seebeck coefficient [29] |

| Acid-Triggered Side Chain Cleavage | POET-T2-COOH | F₄TCNQ + TfOH (acid) | Not specified | 100,000× | Simultaneous side chain removal and doping; exceptional environmental and thermal stability [27] |

| Vapor Phase Doping | Polyacetylene | Iodine vapor | Metallic conductivity | Several million times | Nobel Prize-winning approach; established foundation for conducting polymer field [26] |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Doping Experiments

| Reagent | Chemical Classification | Function in Doping Process | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iodine (I₂) | Halogen oxidant | p-type dopant through electron acceptance | Effective for vapor-phase or bulk mixing; reversible with heating; used in titanocene polyamine systems [28] |

| F₄TCNQ | Organic acceptor molecule | Strong p-type dopant with high electron affinity | Often used with acid additives; effective for high-conductivity applications [26] [27] |

| TEMPO Derivatives | Nitroxide-based dopants | p-type dopants for coupled reaction systems | Require Lewis acid additives for enhanced efficiency; enable two-electron transfer [29] |

| Tris(pentafluorophenyl)borane (BCF) | Lewis acid | Additive for coupled reaction doping | Binds to reduced dopant species, driving thermodynamically favorable doping reaction [29] |

| Trifluoromethanesulfonic Acid (TfOH) | Strong Brønsted acid | Triggers side chain cleavage and enhances doping | Removes insulating alkyl chains while synergistically enhancing primary dopant effect [27] |

| FeCl₃ | Metal salt oxidant | p-type dopant through oxidation of polymer backbone | Effective for various conjugated polymers; requires controlled conditions [26] |

Doping Workflow Visualization

Doping Strategy Selection Workflow

Charge Transfer Mechanism in p-type Doping

Application in Organic Electronics

The strategic doping of conjugated polymers enables their application across diverse organic electronic devices, particularly OLEDs and photovoltaic cells, where tailored conductivity is essential for device performance.

In organic photovoltaics (OPVs), doped conjugated polymers serve as hole transport materials (HTMs) and electron transport materials (ETMs) that enhance charge separation and reduce recombination losses [30] [31]. For instance, in perovskite solar cells (PSCs), doped polymers like poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) facilitate efficient hole extraction from the perovskite active layer, critically influencing power conversion efficiencies [30]. Similarly, in dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs), doped polymers function as catalytic counter electrodes and solid-state electrolytes, enabling improved charge transport and device stability [30].

For organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs), doping enables precise control over charge injection and transport layers, balancing electron and hole flux within the emission layer to maximize radiative recombination efficiency [31] [26]. Doped charge transport layers also facilitate exciton confinement within the active region, significantly enhancing device efficiency and operational lifetime.

The development of advanced doping strategies continues to expand the application scope of conducting polymers into emerging technologies including flexible electronics, bioelectronic sensors, and thermoelectric energy harvesting systems, where the combination of tunable electronic properties and mechanical flexibility offers distinct advantages over conventional inorganic semiconductors [26] [27].

Fundamental Optical Properties for Light Emission and Absorption

The exploration of fundamental optical properties is paramount for advancing the performance of optoelectronic devices based on conducting organic polymers. These materials have transitioned from their traditional role as electrical insulators to becoming versatile semiconductors capable of efficient light emission and absorption, enabling transformative technologies in photovoltaics and light-emitting diodes (LEDs) [32]. Their unique capabilities stem from a π-conjugated electron system along the polymer backbone, where alternating single and double bonds create delocalized π-electron clouds that significantly reduce the energy gap between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) to semiconductor-like levels of 1–3 eV [33] [34]. This electronic structure forms the foundation for their distinctive light-matter interactions, including strong absorption across visible wavelengths and efficient light emission properties that can be systematically tuned through molecular engineering [35] [34].

Within the context of a broader thesis on conducting polymers for LEDs and photovoltaic cells, understanding these optical properties provides the critical link between molecular design and device performance. When these organic semiconductors absorb photons, they primarily generate excitons (electron-hole pairs bound by Coulombic interactions) rather than free charge carriers, with binding energies typically ranging from 0.3 to 1.0 eV [34]. This fundamental characteristic necessitates careful device engineering, particularly in photovoltaic applications where donor-acceptor heterojunctions provide the necessary energy level offset to dissociate these excitons into free charges [34]. Conversely, in LED applications, injected electrons and holes form excitons that recombine radiatively, producing light whose color and efficiency depend intimately on the polymer's optical characteristics and electronic structure [32] [34].

Fundamental Optical Properties and Characterization

Key Optical Parameters

The optical behavior of conducting polymers is quantified through several fundamental parameters that directly influence device performance in LEDs and photovoltaics. These parameters can be systematically measured and engineered to optimize materials for specific applications.

Table 1: Fundamental Optical Properties of Conducting Polymers and Their Significance

| Optical Property | Symbol | Definition | Significance in Optoelectronics | Typical Range/Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption Maximum | λabs, max | Wavelength of maximum photon absorption | Determines light-harvesting range in photovoltaics; defines material color | 380–700 nm (visible range for 63% of chromophores) [35] |

| Emission Maximum | λemi, max | Wavelength of maximum photon emission | Determines emission color in LEDs; indicates bandgap energy | 380–700 nm (visible range for 88% of chromophores) [35] |

| Extinction Coefficient | εmax | Measure of absorption strength at specific wavelength | Indicates absorption efficiency; crucial for thin-film device design | log₁₀(εmax) > 2.5 for most chromophores [35] |

| Photoluminescence Quantum Yield | ΦQY | Ratio of photons emitted to photons absorbed | Measures light emission efficiency; critical for LED performance | Ranges from 0 to 1; standards include rhodamine 6G (ΦQY ≈ 1) [35] |

| Fluorescence Lifetime | τ | Average time a molecule remains in excited state before emission | Informs about excited state dynamics; affects device response times | Typically 0.1–20 ns (≈5% > 20 ns) [35] |

| Bandwidth (FWHM) | σabs, σemi | Full width at half maximum of absorption/emission peaks | Indicates spectral purity; narrower bands provide more saturated colors | Typically extracted from spectra in nm or cm⁻¹ [35] |

The absorption and emission properties of conducting polymers arise from electronic transitions between the HOMO and LUMO levels, modified by vibrational states that create characteristic spectral features [34]. When a photon is absorbed, electrons are excited from the HOMO to LUMO, creating a vibronic progression in the absorption spectrum due to coupling with molecular vibrations. Emission occurs when excited electrons return to the ground state, typically showing a Stokes shift (energy difference between absorption and emission maxima) due to geometric relaxation in the excited state [34]. This vibronic structure leads to characteristic absorption and emission bands rather than sharp transitions, with the spectral shape influenced by both electronic and vibrational states.

Experimental Protocol: Characterization of Optical Properties

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Optical Characterization of Conducting Polymers

Purpose: To quantitatively measure the fundamental optical properties of conducting polymers, including absorption maxima, emission maxima, extinction coefficients, photoluminescence quantum yield, and fluorescence lifetime.

Materials and Equipment:

- Ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectrophotometer

- Spectrofluorimeter with integrating sphere accessory

- Time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy system

- Quartz cuvettes (for solution measurements)

- Solid sample holders (for thin-film measurements)

- Reference standards (e.g., rhodamine 6G, quinine sulfate for quantum yield calibration)

- High-vacuum system for thin-film preparation (optional)

- Solvents (high-purity, spectroscopic grade)

Procedure:

Sample Preparation:

- For solution measurements: Prepare polymer solutions in appropriate solvents at concentrations typically yielding absorbance < 0.1 at the absorption maximum to avoid inner-filter effects. Ensure complete dissolution and homogeneity.

- For thin-film measurements: Deposit polymer films on optically transparent substrates (e.g., quartz) using appropriate methods (spin-coating, drop-casting, or thermal evaporation). Ensure uniform thickness and optical clarity.

Absorption Measurements:

- Calibrate the UV-Vis spectrophotometer with a blank reference (pure solvent or clean substrate).

- Record absorption spectra across the UV-Vis range (typically 250-800 nm) with appropriate resolution (1-2 nm).

- Determine the absorption maximum (λabs, max) and full width at half maximum (σabs) from the corrected spectrum.

- For extinction coefficient (εmax) calculation: Measure absorbance at λabs, max for a series of dilutions and apply the Beer-Lambert law (A = εcl, where A is absorbance, c is concentration, and l is path length). Plot absorbance versus concentration; the slope gives εmax.

Emission Measurements:

- Calibrate the spectrofluorimeter using appropriate wavelength and intensity standards.

- Select an excitation wavelength typically corresponding to the absorption maximum or a nearby peak.

- Record emission spectra, ensuring the detection range covers from slightly below the excitation wavelength to well beyond the expected emission maximum.

- Determine the emission maximum (λemi, max) and bandwidth (σemi) from the corrected spectrum.

- Correct spectra for instrument response function using manufacturer-provided correction files.

Quantum Yield Determination:

- Using an integrating sphere attached to the spectrofluorimeter, measure the integrated photoluminescence intensity of both the sample and a reference standard with known quantum yield.

- For solution measurements: Use matched concentrations with absorbance < 0.1 at excitation wavelength.

- Calculate absolute photoluminescence quantum yield (ΦQY) using established protocols, comparing the integrated emission of the sample to that of the reference standard with correction for refractive index differences.

Fluorescence Lifetime Measurements:

- Using time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy (typically time-correlated single photon counting), excite the sample with a pulsed laser source at an appropriate wavelength.

- Collect the fluorescence decay curve at the emission maximum.

- Fit the decay curve to appropriate models (single or multi-exponential) to extract fluorescence lifetime components (τi) and amplitudes (Ai).

- Calculate the average lifetime: τ = Σ(Aiτi)/ΣAi.

Data Analysis and Interpretation:

- Compile all measured parameters into a comprehensive optical properties table.

- Analyze the Stokes shift (λemi, max - λabs, max) as an indicator of structural reorganization in the excited state.

- Compare emission spectra obtained with different excitation wavelengths to check for sample heterogeneity.

- For thin films, consider effects of molecular packing, intermolecular interactions, and potential aggregation on optical properties.

Troubleshooting:

- If absorption is too high (>2), dilute samples further to avoid detector saturation and inner-filter effects.

- If emission signals are weak, increase integration times or concentration (while maintaining absorbance < 0.1 at excitation wavelength).

- For quantum yield measurements, ensure reference standards are freshly prepared and properly matched to sample conditions.

Figure 1: Optical property characterization workflow for conducting polymers

Material Design and Synthesis Protocols

Backbone Engineering and Side-Chain Modification

The optical and electronic properties of conducting polymers can be systematically tuned through strategic molecular design, primarily through backbone engineering and side-chain modification. The conjugated backbone largely determines the energy level distribution and electronic conductivity of these materials [8]. In organic semiconductors, charge carriers are transported along the conjugated polymer backbone via intra-chain transport and inter-chain π-π stacking interactions [8]. The chemical structure features alternating single and double bonds, where the σ bonds form the molecular backbone, and the conjugated π electrons become delocalized, creating conductive pathways for mobile charges within the polymer [8].

A highly effective strategy for designing low-bandgap semiconducting polymers involves alternating donor (D) and acceptor (A) units along the polymer backbone in a regular pattern [8]. The interactions between the D and A components facilitate π electron delocalization, leading to a quinoid mesomeric structure along the polymer main chain, resulting in a reduced bandgap [8]. This D-A approach enables precise tuning of the HOMO and LUMO energy levels, which directly influence the absorption and emission characteristics of the material. For instance, incorporating fluorine into polymer backbones can deepen the HOMO energy levels without significantly affecting the bandgap or light-harvesting properties [8].

Table 2: Common Building Blocks for Conducting Polymer Design

| Material Component | Representative Examples | Function in Polymer Design | Impact on Optical Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Donor Units | Thiophene, Carbazole, Triphenylamine | Provide electron-rich character; determine HOMO energy level | Influence absorption onset and emission color [8] |

| Acceptor Units | Perylenediimide (PDI), Fluorene derivatives | Provide electron-deficient character; determine LUMO energy level | Narrow bandgap; enhance charge separation [8] |

| Side Chains | Alkyl, Ethylene glycol, Ionic groups | Improve solubility and processability; control molecular packing | Affect interchain interactions and film morphology [8] |

| Dopants | Dodecylbenzenesulfonic acid (DBSA) | Enhance conductivity through oxidative or reductive doping | Can modify absorption characteristics and quenching efficiency [33] |

Side-chain engineering plays an equally crucial role in determining the ultimate optical properties and device performance. The attachment of polar side chains to create conjugated polyelectrolytes (CPEs) enables simultaneous electronic and ionic transport, expanding their applicability in various optoelectronic devices [8]. These side chains not only aid in processing but also facilitate the use of these materials in organic multilayer devices, including organic solar cells (OSCs) and perovskite solar cells (PSCs) [8]. The presence of specific side chains can influence molecular packing, thin-film morphology, and ultimately the efficiency of light emission and absorption processes in functional devices.

Experimental Protocol: Chemical Synthesis of Polyaniline

Protocol 2: Chemical Oxidation Synthesis of Polyaniline for Optoelectronic Applications

Purpose: To synthesize conductive polyaniline (PANI) via chemical oxidation polymerization, producing material suitable for optical and electronic characterization.

Materials and Equipment:

- Aniline monomer (distilled under reduced pressure before use)

- Oxidizing agent: Ammonium persulfate (APS) or ammonium peroxy disulfate

- Dopant acid: Hydrochloric acid (HCl) or camphorsulfonic acid (CSA)

- Solvents: Deionized water, toluene (for interfacial polymerization)

- Inert atmosphere setup (nitrogen or argon gas)

- Magnetic stirrer with temperature control

- Ice bath

- Filtration setup (Buchner funnel and filter paper)

- Vacuum oven for drying

Procedure:

Chemical Oxidation Polymerization (Standard Method):

- Dissolve aniline monomer (1.0 M) in 1 M HCl solution (100 mL) in a round-bottom flask.

- Cool the solution to 0-5°C using an ice bath while stirring under inert atmosphere.

- Prepare a separate solution of ammonium persulfate (1.0 M) in 1 M HCl, pre-cooled to 0-5°C.

- Slowly add the oxidant solution to the aniline solution dropwise with vigorous stirring, maintaining temperature below 5°C.

- Continue stirring for 4-24 hours, allowing the reaction mixture to gradually warm to room temperature.

- Observe color change to dark green, indicating formation of emeraldine salt form of PANI.

Product Isolation and Purification:

- Filter the resulting dark green precipitate using a Buchner funnel.

- Wash repeatedly with deionized water, followed by acetone or ethanol to remove oligomers and unreacted starting materials.

- Dry the product under dynamic vacuum at 40-60°C for 24 hours.

- Characterize the product using UV-Vis spectroscopy (dissolved in appropriate solvents or as thin film) and four-point probe conductivity measurements.

Alternative Method: Interfacial Polymerization:

- Dissolve aniline monomer in organic solvent (toluene or chloroform) in a beaker.

- Carefully layer an aqueous solution of oxidant (ammonium persulfate) and dopant acid over the organic phase without mixing.

- Polymerization occurs at the interface between the two immiscible liquids, forming a PANI film.

- Carefully collect the interfacial film for characterization and device fabrication.

Critical Parameters for Optical Quality:

- Temperature control: Maintaining low temperature during initial polymerization stages controls reaction kinetics and polymer chain length.

- Oxidant to monomer ratio: Typically 1:1 molar ratio for optimal conductivity and molecular weight.

- Dopant selection: Different dopant acids (HCl vs. CSA) can significantly influence optical properties and solubility.

- Reaction time: Longer reaction times generally yield higher molecular weight polymers with shifted optical spectra.

Characterization:

- UV-Vis spectroscopy of polymer solutions or films should show characteristic peaks at ~330-360 nm (π-π* transition) and ~400-450 nm (polaron-π* transition) for the conductive emeraldine salt form.

- The conductivity of PANI is dependent upon dopant concentration, reaching metal-like conductivity only when pH is less than 3 [33].

- FT-IR spectroscopy can verify the oxidation state and doping level of the product.

Figure 2: Polyaniline synthesis and processing workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Conducting Polymer Synthesis and Characterization

| Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monomer Precursors | Aniline, Pyrrole, Thiophene, Acetylene | Building blocks for polymer synthesis | Require purification (distillation/recrystallization) before use [33] |

| Oxidizing Agents | Ammonium persulfate, Iron(III) chloride | Initiate chemical oxidation polymerization | Concentration and addition rate affect polymer structure [33] |

| Dopants | HCl, Camphorsulfonic acid, DBSA | Enhance conductivity; modify optical properties | Determine electrical and optical characteristics of final product [33] |

| Solvents | Chloroform, Toluene, THF, Water | Medium for synthesis and processing | Affect molecular weight and morphology during polymerization [33] |

| Catalysts | Ziegler-Natta, Luttinger catalysts | Facilitate specific polymerization routes | Essential for polyacetylene synthesis [33] |

| Optical Standards | Rhodamine 6G, Quinine sulfate | Calibrate quantum yield measurements | Require careful preparation and handling [35] |

| Spectroscopic Tools | UV-Vis spectrophotometer, Spectrofluorimeter | Characterize absorption and emission | Require regular calibration with reference standards [35] |

The fundamental optical properties of conducting polymers—including absorption and emission characteristics, quantum yields, and excited-state dynamics—provide the critical foundation for their application in advanced optoelectronic devices. Through systematic material design incorporating donor-acceptor backbone engineering and strategic side-chain functionalization, researchers can precisely tune these properties to meet specific application requirements in photovoltaics and LED technologies [8]. The experimental protocols outlined for both characterization and synthesis provide robust methodologies for developing and evaluating new materials in this rapidly advancing field.

The unique advantage of conducting polymers lies in their ability to combine the electronic and optical properties of semiconductors with the processing flexibility and mechanical properties of plastics [34]. This combination enables innovative device architectures, including flexible displays, lightweight photovoltaic cells, and biocompatible sensors. As research continues to advance our understanding of the relationship between molecular structure, optical properties, and device performance, conducting polymers are poised to play an increasingly important role in next-generation optoelectronic technologies. The quantitative framework presented here for measuring, analyzing, and optimizing fundamental optical properties provides researchers with the necessary tools to contribute to this exciting field.

Synthesis, Fabrication, and Device Integration for LEDs and Photovoltaics

Advanced fabrication techniques are pivotal in transitioning conducting polymer research from laboratory-scale curiosities to commercially viable technologies for light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and photovoltaic cells. The unique physical and chemical properties of conductive polymers—including mechanical flexibility, tunable electronic characteristics, and solution processability—demand specialized manufacturing approaches that preserve their functional integrity while enabling scalable production [7]. Electrochemical deposition, roll-to-roll printing, and spray coating have emerged as three particularly promising methodologies that address these requirements while offering complementary advantages for different applications and device architectures [36] [37]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for implementing these techniques within research and development settings focused on organic electronic devices.

Electrochemical Deposition

Application Notes

Electrochemical deposition enables controlled synthesis of conductive polymer thin films directly onto conductive substrates through electrochemical oxidation of monomer species. This technique offers significant advantages for applications requiring precise thickness control, high conductivity, and conformal coatings on complex geometries [38]. Unlike chemical synthesis methods, electrochemical approaches produce polymers with enhanced conductivity and controllable morphology by regulating deposition parameters such as applied potential, current density, and electrolyte composition [7]. The method is particularly valuable for creating uniform, pinhole-free films for electrode interfaces in supercapacitors, battery systems, and as charge transport layers in photovoltaic devices [7].

The process leverages the intrinsic doping capabilities of conjugated polymer systems, where the electrochemical parameters directly control the doping level and consequently the electronic properties of the resulting film [7]. Commonly deposited polymers include polyaniline (PANI), polypyrrole (PPy), and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT), each offering distinct electrical and morphological characteristics suited to different device applications [7].

Experimental Protocol: Electrodeposition of PEDOT Films

Materials and Equipment:

- Monomer Solution: 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene (EDOT) monomer (0.01-0.05M) in appropriate electrolyte (e.g., lithium perchlorate in acetonitrile or propylene carbonate)

- Working Electrode: Conducting substrate (ITO, FTO, or metal electrodes)