Computational Design of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers: From AI-Powered Virtual Screening to Biomedical Applications

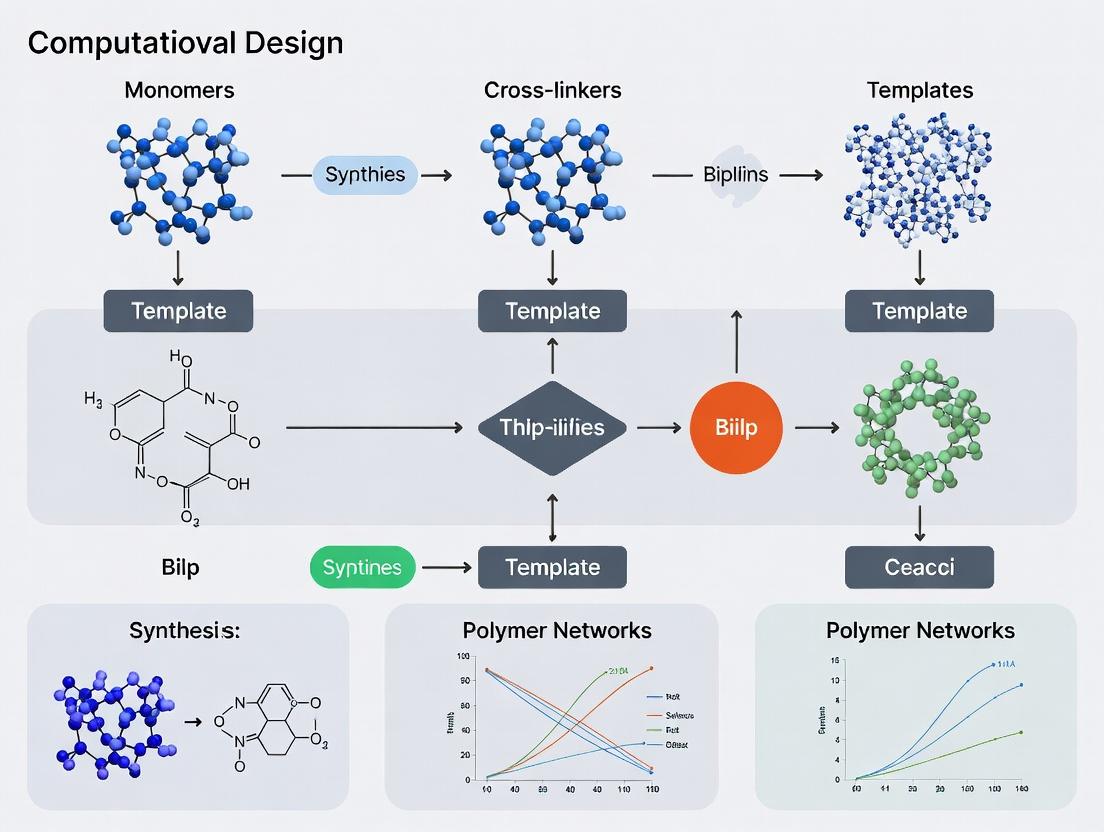

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the computational design of molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs).

Computational Design of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers: From AI-Powered Virtual Screening to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the computational design of molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs). We begin by exploring the fundamental principles of molecular imprinting and the critical role of computation in transitioning from trial-and-error to rational design. The core methodological section details the workflow, from virtual screening of monomers and cross-linkers using density functional theory (DFT) and molecular dynamics (MD) to the prediction of polymer morphology and binding site distribution. We address common computational pitfalls, optimization strategies for enhancing selectivity and affinity, and methods to simulate real-world conditions. Finally, the article covers the validation of computational models through experimental techniques like SPR and QCM, and compares MIP performance against natural antibodies and aptamers. The conclusion synthesizes key takeaways and outlines future directions for personalized medicine, point-of-care diagnostics, and therapeutic delivery systems.

Molecular Imprinting 2.0: The Computational Foundation for Rational MIP Design

Molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) are synthetic polymeric networks possessing specific recognition sites complementary to a target molecule (template) in shape, size, and functional group orientation. Their synthesis involves copolymerization of functional and cross-linking monomers in the presence of the template. Subsequent template removal leaves cavities with a "memory," enabling selective rebinding. This application note details their computational design, synthesis protocols, and key applications within drug development, providing researchers with actionable methodologies.

Within the thesis on computational design, MIPs represent the tangible output of in silico predictions. Computational tools (e.g., molecular dynamics, density functional theory) are employed to screen monomers, simulate pre-polymerization complexes, and predict binding affinity and selectivity before synthesis. This rational design approach minimizes costly empirical trial-and-error, accelerating the development of MIPs as "synthetic antibodies" for sensing, separations, and drug delivery.

Application Notes & Quantitative Performance

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Computationally Designed MIPs in Analytical Applications

| Target Analyte (Template) | Computed Binding Energy (ΔG, kcal/mol) | Experimental Binding Affinity (Kd, nM) | Selectivity Factor (vs. Structural Analog) | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortisol | -8.2 | 0.45 | 12.5 | Diagnostic Sensors |

| Enrofloxacin | -9.7 | 1.8 | 9.3 | Food Safety Assays |

| Lysozyme | -10.5 | 2.1 | 15.8 | Protein Separation |

| Theophylline | -7.5 | 85.0 | 22.0 (vs. Caffeine) | Therapeutic Monitoring |

Table 2: Key Advantages of Computational MIP Design

| Parameter | Traditional Combinatorial Screening | Computational Pre-Screening | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to optimal monomer selection | 4-6 weeks | 1-2 weeks | ~3-4x |

| Material consumption (monomers/solvents) | High | Very Low | >10x reduction |

| Success rate (Kd < 10 nM) | ~15% | ~60% | ~4x |

| Optimal cross-linker ratio prediction accuracy | ± 25% | ± 8% | ~3x precision |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1:In SilicoMonomer Screening for a Small-Molecule Target

Objective: To identify the most promising functional monomer for MIP synthesis targeting a specific template.

- Template Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure (SDF/MOL file) of the target molecule (e.g., from PubChem). Optimize its geometry using DFT (e.g., Gaussian, B3LYP/6-31G* basis set).

- Monomer Library: Create a digital library of common functional monomers (e.g., methacrylic acid, acrylamide, vinylpyridines).

- Docking Simulation: Use molecular docking software (AutoDock Vina, GOLD) or molecular dynamics (GROMACS) to simulate template-monomer interactions in a defined virtual solvent box.

- Scoring & Ranking: Calculate the binding free energy (ΔG) for each complex. Rank monomers based on the most negative ΔG, indicating strongest interaction.

- Complex Optimization: Take the top 3 monomers and simulate pre-polymerization ternary complexes (template:monomer:cross-linker) to assess stability.

Title: Computational Monomer Screening Workflow

Protocol 3.2: Solid-Phase Synthesis of MIP Nanoparticles (Core-Shell Format)

Objective: To synthesize uniform MIP nanoparticles with high binding capacity using a solid-phase imprinting approach. Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit" below. Procedure:

- Silica Core Functionalization: Disperse 1.0 g of amino-functionalized silica nanoparticles (200 nm) in 50 mL anhydrous DMSO. Add 2 mL of template-acrylate derivative (e.g., cortisol methacrylate). React under N₂ with gentle shaking for 24h at 25°C. Wash extensively with methanol/acetic acid (9:1 v/v) to remove physisorbed template.

- Surface-Initiated Polymerization: Re-disperse template-functionalized cores in 40 mL acetonitrile in a three-neck flask. Add the computationally pre-selected functional monomer (e.g., methacrylic acid, 4 mmol) and cross-linker (ethylene glycol dimethacrylate, 20 mmol). Degas with N₂ for 15 min.

- Initiation: Add the initiator (AIBN, 0.2 mmol). React under N₂ at 60°C for 24h with mechanical stirring.

- Core Etching & Template Removal: Recover nanoparticles by centrifugation. Re-suspend in 50 mL of 4M ammonium hydrogen fluoride solution and stir for 48h to etch the silica core. Dialyze the resulting hollow MIP shells against water for 5 days. Perform a final wash with methanol/acetic acid (8:2 v/v) to ensure complete template removal. Characterize by DLS and SEM.

Title: Solid-Phase MIP Nanoparticle Synthesis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

| Item & Specification | Function in MIP Development | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Methacrylic Acid (MAA), 99% | Primary functional monomer for H-bond/donor-acceptor templates. | Versatile, strong carboxylic acid interaction group; predicted frequently by computation for basic/neutral targets. |

| Ethylene Glycol Dimethacrylate (EGDMA), 98% | Cross-linking monomer. | Provides mechanical stability and defines cavity rigidity. Computational MD predicts optimal EGDMA ratio for porosity. |

| 2,2'-Azobis(2-methylpropionitrile) (AIBN), recrystallized | Thermal radical initiator. | Standard for polymerization in organic solvents at 60-70°C; ensures reproducible initiation. |

| Amino-functionalized Silica Nanoparticles (200nm) | Solid-phase sacrificial core. | Enables uniform spherical MIP shell formation; etched to leave controlled, accessible cavities. |

| Acetonitrile (HPLC Grade) | Porogenic solvent. | Common non-protic solvent for non-covalent imprinting; affects polymer morphology and template-monomer interaction strength. |

| Molecular Modeling Suite (e.g., Schrödinger, AutoDock Tools) | In silico screening platform. | Enables virtual screening of monomer libraries and prediction of binding site geometry prior to synthesis. |

Within the thesis on the computational design of molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs), this application note details the quantitative and procedural limitations of the traditional, empirical development approach. The transition from this costly trial-and-error paradigm to a rational, computationally guided workflow is imperative for advancing MIP applications in diagnostics, sensing, and drug development.

Quantitative Analysis of Traditional MIP Development Costs

The traditional MIP development cycle involves iterative screening of monomers, cross-linkers, porogens, and polymerization conditions. The resource expenditure is substantial, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Resource Allocation in a Traditional Empirical MIP Development Project

| Development Phase | Average Time (Weeks) | Approximate Material Cost (USD) | Number of Synthesis Iterations (Typical Range) | Success Rate for High-Performance MIPs (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Template & Monomer Selection | 2-3 | 500 - 2,000 | 10 - 30 (theoretical) | < 5 |

| Polymerization & Optimization | 6-10 | 3,000 - 8,000 | 50 - 200 | 10 - 20 |

| Characterization & Validation | 4-6 | 2,000 - 5,000 | 10 - 50 | 30 - 50 |

| Total Per Target | 12-19 | 5,500 - 15,000 | 70 - 280 | ~1-3 (Final) |

The Traditional Trial-and-Error Workflow Protocol

The following protocol exemplifies the standard empirical approach for developing a MIP for a small-molecule target (e.g., a pharmaceutical contaminant).

Protocol: Empirical Screening of Functional Monomers

Objective: To identify a suitable functional monomer for a target molecule via bulk polymerization and binding assessment.

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" (Section 6).

Procedure:

- Template-Monomer Complex Preparation:

- Dissolve the target template molecule (0.05 mmol) and one candidate functional monomer (0.2 mmol) in 5 mL of selected porogen (e.g., acetonitrile or chloroform) in a glass vial.

- Seal the vial and incubate at 4°C for 2 hours to allow pre-complexation.

- Bulk Polymerization:

- To the mixture, add cross-linker (e.g., EGDMA, 1.0 mmol) and radical initiator (e.g., AIBN, 0.02 mmol). Purge the solution with nitrogen or argon for 5 minutes to remove oxygen.

- Seal the vial and place it in a water bath or thermal block at 60°C for 18-24 hours.

- Polymer Processing:

- Crush the resulting monolithic polymer block and grind it mechanically.

- Sieve the particles to obtain a 25-50 μm fraction.

- Perform Soxhlet extraction with methanol:acetic acid (9:1, v/v) for 24 hours to remove the template molecule.

- Dry the resulting MIP particles under vacuum at 40°C overnight.

- Batch Rebinding Test:

- Weigh 10 mg of dry MIP into a 2 mL HPLC vial.

- Add 1 mL of a solution containing the template at a known concentration (e.g., 0.1 mM in the porogen).

- Agitate the suspension on a shaker for 6 hours at room temperature.

- Centrifuge and filter the supernatant. Analyze the free template concentration using HPLC-UV.

- Calculate the amount of template bound to the polymer (Q = (Cinitial - Cfree) * V / m).

- Control Experiment: Repeat steps 1-4 using the Non-Imprinted Polymer (NIP), synthesized identically but in the absence of the template.

- Analysis: Calculate the imprinting factor (IF) = QMIP / QNIP. An IF > 1.5 is typically considered indicative of successful imprinting. Repeat the entire process for each candidate monomer (e.g., MAA, 4-VP, acrylamide).

Protocol: Optimization of Polymerization Conditions

Objective: To empirically optimize the ratio of monomer:cross-linker:porogen for the best-performing monomer from Protocol 3.1.

Procedure:

- Design a factorial matrix varying:

- Monomer:Template ratio (e.g., 2:1, 4:1, 8:1)

- Cross-linker percentage (e.g., 70%, 80%, 90% mol relative to monomer)

- Porogen type (e.g., acetonitrile, toluene, dimethyl sulfoxide)

- Synthesize MIPs and NIPs for each condition in the matrix using the bulk polymerization method (Steps 2-3 from Protocol 3.1).

- Perform batch rebinding tests (Protocol 3.1, Step 4) for all polymers.

- Select the condition yielding the highest imprinting factor and binding capacity. This process typically requires 20-50 parallel syntheses and analyses.

Visualizing the Costly Empirical Cycle

The iterative, non-predictive nature of traditional MIP development leads to a resource-intensive cycle with a low probability of success.

Diagram Title: The Costly Empirical MIP Development Cycle

Key Limitations & Data on Failed Iterations

The empirical approach's inefficiency is further highlighted by data on common failure points.

Table 2: Common Failure Modes in Traditional MIP Development

| Failure Mode | Frequency (% of Iterations) | Consequence | Primary Cause |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor Binding Affinity | 40-60% | Low imprinting factor (IF < 1.5) | Incorrect monomer-template interaction or stoichiometry |

| Inadequate Selectivity | 20-30% | High cross-reactivity with analogs | Poor spatial fidelity of imprinted cavity |

| Template Leaching/Incomplete Removal | 10-15% | High background, false positives | Irreversible binding or physical entrapment |

| Low Batch-to-Batch Reproducibility | 15-25% | Inconsistent performance data | Sensitive dependence on subtle variations in procedure |

| Poor Morphology/Kinetics | 10-20% | Slow binding, low capacity | Suboptimal porogen and cross-linker choice |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Traditional MIP Development

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Empirical MIP Development

| Reagent / Material | Typical Function in MIP Synthesis | Notes & Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Monomers | Provide complementary interactions with the target template (non-covalent imprinting). | Methacrylic acid (MAA, H-bond donor/acceptor), 4-Vinylpyridine (4-VP, base), Acrylamide (H-bond donor). Large libraries exist for screening. |

| Cross-linkers | Create a rigid, porous polymer network that stabilizes the imprinted cavities. | Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA), Trimethylolpropane trimethacrylate (TRIM). High purity (>98%) is critical for reproducibility. |

| Porogens (Solvents) | Dissolve all components and dictate polymer morphology (pore size and surface area). | Acetonitrile (polar, aprotic), Chloroform (non-polar, H-bonding), Toluene (non-polar). Choice is largely empirical. |

| Radical Initiators | Initiate the free-radical polymerization reaction. | Azoisobutyronitrile (AIBN), activated thermally (60-70°C). Must be purified by recrystallization. |

| Template Molecules | The target analyte around which the complementary cavity is formed. | Often expensive/pharmaceuticals. Must be soluble in porogen and stable during polymerization. |

| Extraction Solvents | Remove the template molecule from the polymer post-synthesis to reveal binding sites. | Methanol:Acetic Acid (9:1 v/v) is standard for breaking non-covalent interactions. |

Computational Design as the Rational Alternative

The thesis posits that integrating computational tools—such as molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and density functional theory (DFT) calculations for monomer screening, and molecular modeling for cavity design—into the workflow directly addresses the limitations outlined above. This rational approach aims to replace the initial, costly empirical cycles with in silico prediction, dramatically reducing the number of physical experiments required to arrive at an optimal MIP formulation.

The traditional development of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) has been plagued by a laborious, Edisonian trial-and-error approach. The broader thesis of this work posits that integrating computational chemistry at the outset of MIP design fundamentally shifts the paradigm from empirical screening to rational, first-pass design. This approach enables the in silico prediction of monomer-template interactions, polymer composition, and binding site characteristics before synthesis, drastically reducing development time and cost while improving MIP performance for applications in drug sensing, separation, and delivery.

Application Notes: Core Computational Workflows

Note 1: Virtual Screening of Functional Monomers

Objective: To identify the most promising functional monomers for a given target molecule (template) through computational screening. Protocol: Using density functional theory (DFT) or molecular mechanics, calculate the binding energy (ΔE) between the template and a library of candidate monomers (e.g., methacrylic acid, acrylamide, vinylpyridine) in a simulated solvent environment. The formation of pre-polymerization complexes is modeled, and interaction energies are ranked.

Table 1: Exemplar Virtual Screening Results for Theophylline Imprinting

| Monomer | Calculated ΔE (kJ/mol) | Primary Interaction Type | Recommended Mole Ratio (Monomer:Template) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methacrylic Acid (MAA) | -28.5 | Hydrogen bonding | 4:1 |

| Acrylamide (AAM) | -24.1 | Hydrogen bonding | 6:1 |

| 2-Vinylpyridine (2-VP) | -19.7 | Ionic/van der Waals | 8:1 |

| Itaconic Acid (IA) | -26.8 | Hydrogen bonding | 4:1 |

| Trifluoromethylacrylic Acid (TFMAA) | -31.2 | Strong H-bond/Electrostatic | 4:1 |

Note 2: Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations of Polymerization

Objective: To simulate the cross-linking process and predict the morphology and stability of the polymer matrix. Protocol: Construct a simulation box containing the template-monomer complex(es), cross-linker (e.g., ethylene glycol dimethacrylate - EGDMA), initiator molecules, and solvent. Run MD simulations under periodic boundary conditions, applying a simulated temperature and pressure cycle to mimic thermo-initiated polymerization. Analyze the resulting polymer network for porosity, cross-link density, and template distribution.

Table 2: MD Simulation Parameters and Outputs for a Standard MIP System

| Parameter | Value/Description | Relevance to MIP Design |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field | GAFF2 or OPLS-AA | Describes interatomic potentials |

| Simulation Time | 50-100 ns | Allows for network formation |

| Cross-linker % (Simulated) | 70-80 mol% | Governs matrix rigidity & site stability |

| Calculated Average Pore Size | 1.5 - 3.0 nm | Indicates accessibility for target |

| Template Entrapment Efficiency (Simulated) | ~85% | Predicts success of imprinting step |

Note 3: Binding Affinity and Selectivity Prediction

Objective: To computationally assess the binding strength and selectivity of the designed MIP for the target versus structural analogs. Protocol: After simulating template removal, use molecular docking or free energy perturbation (FEP) methods to compute the binding free energy (ΔG) of the target and competing molecules to the imprinted cavity. A lower (more negative) ΔG indicates stronger binding.

Table 3: Computed Binding Free Energies for a Propranolol MIP and Analogues

| Ligand | Computed ΔG (kcal/mol) | Selectivity Factor (vs. Atenolol) | Key Interaction Residues in Cavity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Propranolol (Target) | -8.24 | 1.00 (Reference) | Carboxyl, aromatic π-stacking |

| Atenolol | -5.91 | 3.9 | Weak H-bond only |

| Metoprolol | -7.05 | 1.7 | Partial H-bond, weaker π-stack |

| Warfarin | -6.32 | 2.6 | Mismatched geometry |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: Synthesis of Computationally-Designed MIPs

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below. Method:

- Pre-complexation: Dissolve the template (0.25 mmol) and the computationally selected optimal monomer (at the recommended mole ratio from Table 1) in 10 mL of the designated porogenic solvent (e.g., acetonitrile) in a glass vial. Sonicate for 10 minutes.

- Polymerization Mixture: Add the cross-linker (EGDMA, total monomer molar percentage as per simulation, e.g., 80%) and initiator (AIBN, 1% w/w of total monomers) to the vial. Sparge with nitrogen for 5 minutes to remove oxygen.

- Polymerization: Seal the vial and place it in a water bath at 60°C for 24 hours.

- Processing: Crush the resulting bulk polymer and sieve to 25-50 μm particles.

- Template Extraction: Wash particles sequentially with methanol/acetic acid (9:1, v/v) until no template is detectable by UV-Vis (typically 8-10 cycles), followed by methanol to neutrality. Dry under vacuum at 40°C.

Protocol 2: Binding Isotherm Analysis and Characterization

Method:

- Batch Rebinding: Suspend 10 mg of dry MIP or Non-Imprinted Polymer (NIP, control) in 2 mL of solutions containing the template at varying concentrations (0.05 - 2.0 mM) in a suitable buffer.

- Equilibration: Agitate for 6 hours at 25°C.

- Quantification: Separate polymer by centrifugation (13,000 rpm, 5 min). Analyze supernatant concentration via HPLC-UV.

- Data Fitting: Calculate bound amount (Q). Fit data to the Langmuir isotherm model:

Q = (Q_max * C) / (K_d + C), whereQ_maxis the apparent maximum number of binding sites andK_dis the dissociation constant.

Validation: Compare experimental K_d and Q_max with computationally predicted binding affinity trends and site density estimates.

Visualizations

Title: Computational MIP Design & Validation Workflow

Title: From Virtual Screening to Binding Site

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Computational MIP Development |

|---|---|

| Software Suite (e.g., Schrödinger, Gaussian, GROMACS) | Provides platforms for DFT, molecular dynamics, and docking simulations to model interactions and polymer networks. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Enables the processing of large-scale molecular dynamics simulations and virtual screenings in a feasible timeframe. |

| Functional Monomer Library (e.g., MAA, 4-VP, AAM) | A curated set of compounds for virtual screening to identify optimal template-monomer interactions. |

| Cross-linker (EGDMA, TRIM, DVB) | Modeled in MD simulations to determine optimal percentage for creating a rigid, porous polymer scaffold. |

| Porogenic Solvent (Acetonitrile, Toluene, Chloroform) | The solvent environment is a critical variable in simulations, affecting complex formation and pore morphology. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymer Particles (Validated) | The final synthesized material used for experimental validation of computational predictions (binding isotherms, selectivity). |

| HPLC-UV/MS System | Essential for quantifying template concentration during extraction efficiency studies and binding experiments. |

| Reference Analogue Molecules | Used in both computational selectivity predictions and experimental cross-reactivity assays. |

Within the broader thesis on the computational design of molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs), the integration of Density Functional Theory (DFT), Molecular Dynamics (MD), and Molecular Docking has emerged as a critical paradigm. This computational toolbox enables the in silico screening of functional monomers, the rational design of cross-linkers, and the prediction of template-polymer binding affinity and specificity before synthesis. This shifts MIP development from a trial-and-error process to a rational, computationally guided engineering discipline, accelerating the creation of synthetic receptors for sensing, separation, and drug development.

Application Notes

Density Functional Theory (DFT): Electronic Structure for Monomer Selection

DFT calculations are used to evaluate the fundamental interactions between the template molecule (target) and candidate functional monomers. The primary goal is to predict the binding energy and optimal interaction geometry in the pre-polymerization complex.

Key Applications:

- Binding Energy Calculation: Computing the interaction energy (ΔE) between the template and monomer in the gas phase or implicit solvent models to rank monomer efficacy.

- Intermolecular Interaction Analysis: Identifying specific non-covalent interactions (hydrogen bonds, π-π stacking, electrostatic) that stabilize the complex.

- Charge Distribution Analysis: Using Mulliken or Natural Population Analysis (NPA) charges to understand electrostatic complementarity.

Recent Data (2023-2024): Studies on antibiotic and mycotoxin templates show computed binding energies correlate strongly (R² > 0.85) with experimental binding capacities for monomers like methacrylic acid (MAA), 4-vinylpyridine (4-VP), and acrylamide derivatives.

Table 1: DFT-Calculated Binding Energies for Common MIP Monomers with Template Vanillin

| Functional Monomer | Calculated ΔE (kJ/mol) | Key Interaction Type | Reference Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methacrylic Acid (MAA) | -42.7 | Hydrogen bonding | 2023 |

| 4-Vinylpyridine (4-VP) | -28.3 | π-π stacking / weak H-bond | 2023 |

| Acrylamide | -38.9 | Strong hydrogen bonding | 2024 |

| 2-Hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA) | -25.1 | Moderate H-bonding | 2024 |

Molecular Dynamics (MD): Simulating Polymerization and Recognition

MD simulations model the dynamic process of pre-polymerization mixture equilibration, polymerization, and template extraction/rebinding in explicit solvent. This provides insights into the morphology, porosity, and dynamic behavior of the polymer matrix.

Key Applications:

- Pre-Polymerization Mixture Analysis: Simulating the solvation and self-assembly of template-monomer-cross-linker complexes in a virtual box.

- Cross-linking Efficiency: Modeling the formation of the polymer network to assess the impact of cross-linker type (e.g., EGDMA, TRIM) and ratio on cavity stability.

- Rebinding Dynamics: Simulating the diffusion and binding of the template (or analogous molecules) into the imprinted cavity in an aqueous environment, providing data on kinetics and selectivity.

Recent Data (2023-2024): Coarse-grained and all-atom MD simulations have successfully predicted the effect of porogen (solvent) polarity on cavity morphology, with correlation lengths matching SAXS data. Simulations of rebinding events for drug molecules like sertraline show residence times predictive of experimental selectivity coefficients.

Table 2: MD Simulation Parameters and Outputs for MIP Design

| Simulation Stage | Key Parameters | Critical Output Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Polymerization | Force field (GAFF, OPLS-AA), Box size, Solvent model (explicit water/acetonitrile) | Radial distribution functions (RDFs), Cluster analysis of complexes |

| Polymer Network Formation | Reactive force fields (ReaxFF), Cross-linker density, Temperature/pressure control | Polymer density, Solvent-accessible surface area (SASA), Pore size distribution |

| Rebinding | Template insertion, Production run (>100 ns), NPT ensemble | Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of template in cavity, Hydrogen bond occupancy, Interaction energy over time |

Molecular Docking: High-Throughput Screening of Analogues

Molecular docking, traditionally used in drug discovery, is adapted to screen the MIP's imprinted cavity (modeled as a rigid or flexible receptor) against a library of template analogues or potential interferents. This predicts cross-reactivity and selectivity.

Key Applications:

- Cavity Model Creation: Generating a 3D structure of the imprinted cavity from MD-snapshot clusters or DFT-optimized complexes.

- Virtual Screening: Docking a series of structurally related compounds to rank their predicted binding affinities (scores).

- Selectivity Prediction: Identifying which functional groups on the template are crucial for binding by analyzing docking poses of analogues.

Recent Data (2023-2024): Docking studies using AutoDock Vina or Glue into cavities derived from MD trajectories have successfully predicted the selectivity profiles of corticosteroid MIPs, with docking scores correlating with experimental imprinting factors for 80% of tested analogues.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: DFT-Based Monomer Screening

Objective: To compute and rank the binding energy between a target molecule (Template T) and a set of candidate functional monomers (M).

Software: Gaussian 16, ORCA, or similar quantum chemistry package.

- Geometry Optimization: Independently optimize the geometries of T and each monomer M using DFT (e.g., B3LYP functional with 6-31G(d) basis set).

- Complex Building: Manually or algorithmically construct initial guess geometries for the T---M complex, focusing on plausible H-bond or π-interaction sites.

- Complex Optimization: Fully optimize the geometry of each T---M complex using the same DFT method and basis set.

- Frequency Calculation: Perform a vibrational frequency calculation on the optimized complex to confirm it is a true minimum (no imaginary frequencies) and to obtain zero-point energy (ZPE) corrections.

- Energy Calculation: Perform a single-point energy calculation on the optimized species using a higher-level basis set (e.g., 6-311++G(d,p)) and include an implicit solvation model (e.g., SMD for acetonitrile).

- Binding Energy Calculation: Compute the binding energy (ΔEbind) as: ΔEbind = E(T---M) - [E(T) + E(M)], correcting for ZPE and basis set superposition error (BSSE) using the counterpoise method.

Protocol 3.2: MD Simulation of MIP Rebinding

Objective: To simulate the binding event of a template molecule to a pre-modeled MIP cavity in explicit solvent.

Software: GROMACS, AMBER, or LAMMPS.

- Cavity Preparation: Extract a snapshot of a stable imprinted cavity from a previous MD simulation of the polymer matrix. Alternatively, create a model cavity by arranging polymer chains around a minimized T---M complex and then energy-minimizing the system after removing T.

- System Solvation: Place the cavity model in the center of a cubic simulation box. Fill the box with explicit solvent molecules (e.g., water, acetonitrile) using tools like

gmx solvate. - Template Insertion: Place the template molecule at a random position > 1.0 nm from the cavity surface using

gmx insert-molecules. - Energy Minimization: Minimize the energy of the entire system using the steepest descent algorithm to remove bad contacts.

- Equilibration:

- Perform a 100 ps NVT equilibration at 300 K using a V-rescale thermostat.

- Perform a 1 ns NPT equilibration at 1 bar using a Parrinello-Rahman barostat.

- Production MD: Run an unrestrained production simulation for 50-100 ns in the NPT ensemble. Save coordinates every 10 ps.

- Trajectory Analysis:

- Binding Event: Calculate the distance between the center of mass of the template and the cavity over time.

- Interaction Analysis: Use

gmx hbondandgmx energyto compute hydrogen bond occupancy and intermolecular energy between the template and cavity residues. - Pose Clustering: Cluster the poses of the bound template using the

gmx clusterutility.

Protocol 3.3: Docking for Selectivity Assessment

Objective: To dock a series of template analogues into a static model of the MIP cavity and rank their predicted affinity.

Software: AutoDock Vina, GOLD, or LeDock.

- Receptor Preparation: Use the most representative cavity structure from an MD cluster analysis. Prepare the receptor file (

.pdbqtfor Vina) by adding polar hydrogens, assigning Gasteiger charges, and defining the cavity as a rigid entity. - Ligand Preparation: Prepare the 3D structures of the template and all analogues. Generate likely protonation states at target pH, perform energy minimization, and convert to the required format (

.pdbqt). - Grid Box Definition: Define a search space (grid box) that encompasses the entire imprinted cavity and its immediate surroundings. The box center and size should be consistent for all docking runs.

- Docking Execution: Run the docking program for each ligand. Use an exhaustiveness setting of 20-32 for robust sampling. Request multiple poses (e.g., 10) per ligand.

- Result Analysis: Extract the docking score (e.g., Vina score in kcal/mol) for the best pose of each ligand. Analyze the poses to identify key interaction patterns (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts) responsible for binding.

Diagrams and Workflows

Diagram Title: Integrated Computational Workflow for MIP Design

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools & Resources for MIP Design

| Tool/Resource | Category | Function in MIP Design | Example Vendor/Software |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Software | DFT Calculation | Computes electronic structure, binding energies, and optimal complex geometries for monomer selection. | Gaussian, ORCA, CP2K |

| Molecular Dynamics Engine | MD Simulation | Simulates the dynamic processes of polymerization, cavity formation, and template rebinding in solvent. | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, LAMMPS |

| Docking Program | Virtual Screening | Docks template and analogues into a static cavity model to predict binding poses and rank affinities. | AutoDock Vina, GOLD, LeDock |

| Force Field Parameters | Simulation Foundation | Provides mathematical functions and constants to calculate potential energy in MD simulations. | GAFF (General Amber), OPLS-AA, CHARMM |

| Chemical Database | Ligand Source | Provides 3D structures of template molecules, functional monomers, and analogues for screening. | PubChem, ZINC, Cambridge Structural Database |

| Visualization Software | Analysis & Presentation | Visualizes molecular structures, complexes, trajectories, and docking poses. | PyMOL, VMD, ChimeraX |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Hardware Infrastructure | Provides the necessary computational power to run DFT, MD, and large-scale docking jobs efficiently. | Local university clusters, Cloud computing (AWS, Azure), National supercomputing centers |

Within computational design of molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs), the rational selection of functional monomers is paramount. The formation of a stable template-monomer complex (TMC) in the pre-polymerization mixture is the critical first step determining the subsequent polymer's affinity and selectivity. Virtual screening (VS) offers a high-throughput, cost-effective methodology to identify optimal monomers by computationally simulating and ranking these interactions. This Application Note details the protocols for conducting this crucial VS step, framed within a comprehensive MIP design workflow.

Core Principles and Data

The stability of the TMC is governed by non-covalent interactions, which can be quantified computationally. The table below summarizes key computational metrics used to evaluate and rank monomer candidates.

Table 1: Key Computational Metrics for TMC Evaluation in Virtual Screening

| Metric | Description | Optimal Range/Value | Relevance to MIP Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binding Energy (ΔG, kcal/mol) | Calculated free energy of complex formation. | More negative values indicate stronger, more favorable binding. | Directly correlates with expected monomer-template affinity in pre-polymerization phase. |

| Intermolecular Interaction Energy (kcal/mol) | Decomposed energy contributions (e.g., electrostatic, van der Waals). | Strong, complementary contributions (e.g., H-bond, π-π). | Identifies the nature of binding, guiding monomer selection for specific template functional groups. |

| Binding Constant (K, M⁻¹) | Estimated from ΔG (ΔG = -RT lnK). | Higher values indicate greater complex stability. | Predicts the concentration of complex formed under experimental conditions. |

| Intermolecular Distance (Å) | Distance between key interacting atoms (e.g., H-bond donors/acceptors). | Typically 1.5-3.0 Å for H-bonds; < 5.0 Å for strong electrostatic. | Validates the geometry and chemical feasibility of the proposed interaction. |

| Number of Stable Conformers | Count of low-energy bound-state configurations identified via conformational sampling. | Higher numbers suggest a robust, multi-faceted interaction. | Indicates reduced dependence on a single, potentially non-representative, conformation. |

Application Notes & Detailed Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Initial System Preparation and Conformational Sampling

Objective: To generate an ensemble of low-energy conformations for the template and candidate monomers, ensuring comprehensive coverage of possible interaction modes.

Materials/Software:

- Template & Monomer Libraries: 3D structures in SDF or MOL2 format (e.g., from PubChem, ZINC15).

- Software: Molecular mechanics software (e.g., Open Babel, RDKit) for initial minimization and format conversion; Conformational search tool (e.g., OMEGA, CONFAB, RDKit's ETKDG method).

Procedure:

- Structure Preparation: For each molecule, add explicit hydrogens, assign correct protonation states (consider experimental pH, e.g., using Epik or MOE), and perform a preliminary geometry optimization using a molecular mechanics forcefield (e.g., MMFF94, UFF).

- Conformational Generation: For the template and each monomer candidate, execute a systematic or stochastic conformational search.

- Using RDKit (Python): Apply the

ETKDGv3method with an energy window filter (e.g., 10-15 kcal/mol above the global minimum) and a maximum number of conformers (e.g., 50-100 per molecule).

- Using RDKit (Python): Apply the

- Output: Save the ensemble of low-energy conformers for each molecule as multi-structure SDF files.

Protocol 3.2:In SilicoDocking and Complex Generation

Objective: To systematically dock monomer conformers onto template conformers and identify plausible TMC geometries.

Materials/Software:

- Input: Multi-conformer SDF files from Protocol 3.1.

- Software: Molecular docking software suitable for small molecule-small molecule docking (e.g., AutoDock Vina, rDock, GOLD).

Procedure:

- Receptor and Ligand Definition: Designate the template as the "receptor" (fixed) and the monomer as the "ligand" (flexible). Use a pre-generated template conformer as the receptor structure.

- Binding Site Definition: Since the site is undefined, use a "blind docking" approach. Create a large grid box (e.g., 40x40x40 Å) centered on the centroid of the template molecule to allow exploration of all surfaces.

- Docking Execution: Dock each monomer conformer ensemble against each template conformer. Set exhaustiveness high (e.g., 50-100 for Vina) to ensure adequate sampling.

- Post-Processing: Cluster all resulting poses (e.g., by RMSD < 2.0 Å) and retain the lowest energy pose from each major cluster. This yields a diverse set of putative TMC structures.

Protocol 3.3: Binding Affinity Calculation and Ranking

Objective: To accurately calculate the binding free energy (ΔG) for each putative TMC and rank monomer candidates.

Materials/Software:

- Input: Top TMC pose clusters from Protocol 3.2.

- Software: Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation package (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD) for MM-PBSA/GBSA; or advanced scoring functions (e.g., ΔΔNN, Prime MM-GBSA).

Procedure (MM-GBSA using MD):

- System Setup: Solvate each TMC in an explicit solvent box (e.g., TIP3P water). Add ions to neutralize the system. Use appropriate forcefields (e.g., GAFF2 for small molecules, AMBER ff14SB/TIP3P).

- Equilibration: Perform energy minimization, followed by NVT and NPT ensemble equilibration (typically 100 ps each) to stabilize temperature and pressure.

- Production MD: Run an unrestrained MD simulation (1-10 ns) to sample the bound state.

- MM-GBSA Calculation: Extract snapshots from the stable trajectory (e.g., every 100 ps). Calculate the average binding free energy using the MM-GBSA method:

ΔG_bind = G_complex - (G_template + G_monomer)- Where

G = E_MM + G_solv - TS.E_MMis molecular mechanics gas-phase energy,G_solvis solvation free energy (GB model), and-TSis the entropic contribution (often estimated via normal mode analysis).

- Ranking: Rank all monomer candidates based on their calculated ΔG_bind values. Cross-reference with interaction analysis (hydrogen bonds, π-stacking) from the trajectory.

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Virtual Screening Workflow for MIP Monomer Selection

Key Non-Covalent Interactions in a Stable TMC

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for TMC Virtual Screening

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Database | Source of 2D/3D structures for templates and large monomer libraries. | PubChem, ZINC15, MolPort. Provide SMILES/SDF files for thousands of commercial monomers. |

| Cheminformatics Toolkit | Handles file conversion, basic modeling, and automated scripting of workflows. | RDKit (Open Source), Open Babel. Critical for preprocessing and batch operations. |

| Molecular Docking Suite | Performs the core task of sampling binding modes between template and monomer. | AutoDock Vina, rDock, GOLD. Configurable for flexible ligand-flexible receptor docking. |

| Molecular Dynamics Engine | Simulates the dynamic behavior and enables rigorous binding free energy calculations. | GROMACS (Open Source), AMBER, NAMD. Used for MM-PBSA/GBSA and alchemical free energy methods. |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Provides high-accuracy electronic structure calculations for final validation of top candidates. | Gaussian, ORCA, Psi4. Used for DFT-level optimization and interaction energy decomposition (e.g., NCI, EDA). |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Essential computational resource to run docking, MD, and QM calculations in parallel. | Local clusters or cloud computing services (AWS, Azure). |

A Step-by-Step Computational Workflow: From Virtual Screening to Predictive Polymerization

This application note details the systematic workflow for the computational design of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs), a critical component of a broader thesis advancing rational design in molecular recognition. This five-stage framework integrates in silico modeling and experimental validation to enhance selectivity and affinity for target analytes, accelerating development for diagnostics, sensors, and drug delivery.

The Five-Stage Computational MIP Design Workflow

Stage 1: Target and Template Analysis

Objective: Identify the optimal template molecule and understand its molecular interactions. Protocol:

- Target Selection: Obtain the 3D molecular structure (.mol2, .pdb) from databases (PubChem, ZINC).

- Conformational Analysis: Using software like OpenBabel or Gaussian, perform a conformational search to identify low-energy conformers.

- Interaction Site Mapping: Employ ab initio or DFT calculations (e.g., with ORCA or GAMESS) to map electrostatic potential surfaces and identify key functional groups for monomer interaction.

- Template Derivatization (if needed): Design a dummy template or fragment if the original target is unstable or costly, ensuring key interaction motifs are preserved.

Research Reagent Solutions:

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Gaussian 16 | Software for electronic structure modeling, used for conformational and interaction energy calculations. |

| Avogadro | Open-source molecular editor and visualizer for preparing initial 3D structures. |

| Merck Molecular Force Field (MMFF94) | A common force field used for energy minimization and preliminary conformational analysis. |

Stage 2: Virtual Monomer Screening

Objective: Screen a virtual library of functional monomers to identify candidates with high binding affinity to the template. Protocol:

- Library Preparation: Curate a digital library of common MIP monomers (e.g., methacrylic acid, vinylpyridine, acrylamide derivatives).

- Docking/Molecular Dynamics (MD): Use AutoDock Vina or GROMACS to dock monomer(s) to the template. Perform MD simulations (e.g., 10-100 ns in explicit solvent) to assess complex stability.

- Binding Affinity Calculation: Calculate binding free energy (ΔG) using methods like MM-PBSA/GBSA on trajectory snapshots.

- Selection: Rank monomers based on calculated ΔG and analyze interaction types (hydrogen bonds, π-π stacking).

Quantitative Data Table: Exemplary Virtual Screening Results for Theophylline Template

| Monomer | Calculated ΔG (kJ/mol) | No. of H-bonds | Key Interaction Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methacrylic Acid (MAA) | -28.5 | 3 | Ionic/H-bond |

| Acrylamide | -22.1 | 2 | H-bond |

| 4-Vinylpyridine | -24.7 | 1 | Hydrophobic/π-stacking |

| 2-Hydroxyethyl methacrylate | -18.3 | 2 | H-bond |

Stage 3: Polymer Matrix & Cross-linker Optimization

Objective: Model the full pre-polymerization mixture to optimize cross-linker type and ratio for cavity stability. Protocol:

- System Building: Construct a simulation box containing template, selected functional monomer(s), cross-linker (e.g., EGDMA, TRIM), initiator, and solvent molecules using Packmol.

- Molecular Dynamics Simulation: Run an extended MD simulation (>50 ns) of the full mixture using NPT ensemble to observe self-assembly.

- Radical Polymerization Simulation (Optional): Apply reactive force fields (ReaxFF) or simulated polymerization algorithms to model network formation.

- Analysis: Calculate cross-linker density around the template, radial distribution functions (g(r)), and cavity persistence after template extraction in silico.

Stage 4:In SilicoPolymerization & Template Extraction

Objective: Simulate the formation of the polymer network and the subsequent removal of the template to evaluate cavity quality. Protocol:

- Periodic Cell Modeling: Create a periodic cell representation of the pre-polymerization mixture from Stage 3.

- Simulated Polymerization: Use Monte Carlo methods or MD with reactive dynamics to simulate bond formation between monomers and cross-linkers.

- Template Removal: Delete the template molecule coordinates from the polymerized network.

- Cavity Characterization: Analyze the resulting cavity for shape complementarity (using RMSD of template re-docking), volume, and accessibility (using HOLE or CAVER software).

Diagram: Five-Stage Computational MIP Design Workflow

Stage 5: Binding Performance Prediction & Experimental Validation

Objective: Predict MIP selectivity and affinity for the target vs. structural analogs and guide experimental synthesis. Protocol:

- Selectivity Modeling: Re-dock the original template and structural analogs into the simulated cavity from Stage 4. Calculate comparative binding energies.

- Isotherm Prediction: Use Langmuir or Freundlich models parameterized with binding energies to predict adsorption isotherms.

- Protocol Generation: Output a recommended experimental protocol specifying monomers, ratios, solvents, and predicted optimal polymerization conditions.

- Validation Loop: Compare experimental binding data (Qmax, KD from Scatchard plots) with computational predictions to refine the model.

Diagram: Computational-Experimental Validation Feedback Loop

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Software for Computational MIP Design

| Category | Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Software | AutoDock Vina/GROMACS | Molecular docking and MD simulations for monomer screening and complex stability. |

| Software | Gaussian/ORCA | Quantum chemistry calculations for template analysis and accurate interaction energies. |

| Software | PyMOL/Avogadro | 3D visualization and structure preparation. |

| Chemical | Ethylene Glycol Dimethacrylate (EGDMA) | Common cross-linker; provides mechanical stability to the polymer matrix. |

| Chemical | Methacrylic Acid (MAA) | Versatile functional monomer for H-bonding and ionic interactions. |

| Chemical | Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) | Thermo-labile initiator for free-radical polymerization. |

| Analytical | Reference Analogs | Structurally similar molecules used in computational and experimental selectivity assays. |

In the computational design of molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs), the precise selection and analysis of the template molecule is the foundational step that dictates the success of subsequent stages. This phase directly informs virtual screening, monomer selection, and polymerization simulation within the broader thesis workflow. A rigorous conformational analysis ensures the chosen template structure(s) accurately represent the molecule's behavior in the pre-polymerization complex, preventing the design of non-selective or low-affinity binding sites.

Key Considerations for Template Preparation

- Protonation State & Tautomers: The template's charge and form at the expected polymerization pH critically influence ionic/hydrogen-bonding interactions with functional monomers.

- Solvent Environment: Conformational preferences and electronic properties differ drastically between vacuum, implicit solvent (e.g., water, acetonitrile), and explicit solvent models.

- Flexibility: Highly flexible templates require extensive sampling to identify low-energy conformations relevant for imprinting.

Experimental Protocols for Conformational Analysis

Protocol 3.1: Initial Structure Preparation & Optimization

- Source the 3D structure of your target molecule (template) from reliable databases (PubChem, DrugBank).

- Using software like Open Babel, RDKit, or Avogadro, add hydrogens and assign appropriate bond orders.

- Determine the probable protonation state at target pH using tools like ChemAxon Marvin or Epik (Schrödinger). Generate major microspecies and tautomers.

- Perform an initial geometry optimization using semi-empirical methods (e.g., PM7 in MOPAC) or density functional theory (DFT) with a small basis set (e.g., B3LYP/6-31G*) in vacuum to relieve severe steric clashes.

Protocol 3.2: Conformational Sampling

- For small, rigid molecules (<10 rotatable bonds): Perform a systematic conformational search using RDKit's

ETKDGalgorithm or CONFGEN (Schrödinger). Set energy window cutoff to 10-15 kcal/mol. - For large, flexible molecules: Employ enhanced sampling techniques.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) in Explicit Solvent: Solvate the pre-optimized template in a box of explicit solvent molecules (e.g., acetonitrile/water mixture). Run a short MD simulation (1-5 ns) at 300 K using NAMD, GROMACS, or OpenMM. Save snapshots at regular intervals (e.g., 10 ps).

- Meta-dynamics or Hamiltonian Replica Exchange MD: Use for particularly challenging, rugged energy landscapes to ensure comprehensive sampling.

Protocol 3.3: Cluster Analysis and Representative Conformer Selection

- Align all generated conformers from Protocol 3.2 to a reference structure using root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of atomic positions.

- Perform cluster analysis (e.g., using the Butina algorithm in RDKit or hierarchical clustering) based on heavy-atom RMSD. A typical RMSD cutoff is 1.0-1.5 Å.

- Select the lowest-energy conformer from each major cluster (representing >5% of the population) as a representative structure for subsequent monomer screening steps.

Protocol 3.4: Electronic Property Calculation

- For each selected representative conformer, perform a higher-level geometry optimization and frequency calculation using DFT (e.g., ωB97XD/6-311+G(d,p)) with an implicit solvent model (e.g., SMD for acetonitrile).

- Calculate molecular electrostatic potential (MESP) surfaces and extract quantum chemical descriptors:

- Electrostatic Potential (ESP) Min/Max: For identifying hydrogen bonding sites.

- Partial Atomic Charges (e.g., Merz-Singh-Kollman, CHELPG): For assessing Coulombic interactions.

- Frontier Molecular Orbital Energies (HOMO, LUMO): For evaluating charge-transfer potential.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Representative Conformer Analysis for Template Molecule: Theophylline

| Conformer ID | Relative Energy (kcal/mol) | Population (%) | Cluster Size | Dominant Interaction Sites (from MESP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TheoConf1 | 0.00 | 42.5 | 127 | N7 (H-bond acceptor), C8-H (H-bond donor) |

| TheoConf2 | 0.15 | 38.1 | 114 | N9 (H-bond acceptor), C6=O (H-bond acceptor) |

| TheoConf3 | 1.22 | 12.3 | 37 | N7, C6=O (bifurcated acceptor region) |

| TheoConf4 | 2.87 | 7.1 | 21 | N9, C8-H (distinct spatial orientation) |

Table 2: Key Quantum Chemical Descriptors for Theophylline Conformers (ωB97XD/6-311+G(d,p)/SMD(ACN))

| Descriptor | Conformer 1 | Conformer 2 | Conformer 3 | Conformer 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EHOMO (eV) | -7.23 | -7.19 | -7.31 | -7.25 |

| ELUMO (eV) | -0.51 | -0.48 | -0.55 | -0.53 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 4.78 | 5.12 | 3.95 | 4.56 |

| ESP Min (kcal/mol) | -52.1 (at C6=O) | -55.3 (at N9) | -49.8 (at C6=O) | -57.6 (at N9) |

| ESP Max (kcal/mol) | 42.3 (at C8-H) | 38.9 (at N7-H) | 40.1 (at C8-H) | 41.5 (at N7-H) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions & Computational Materials

| Item | Function in Template Preparation & Analysis |

|---|---|

| Chemical Databases (PubChem, ChEMBL) | Source canonical SMILES and initial 3D coordinates for the target template molecule. |

| Structure Preparation Suite (ChemAxon Marvin, Open Babel) | Handle protonation, tautomerization, and file format conversion for computational input. |

| Conformer Generator (RDKit ETKDG, CONFGEN, OMEGA) | Perform rule-based or knowledge-based systematic conformational searches. |

| Molecular Dynamics Engine (GROMACS, NAMD, OpenMM) | Execute explicit-solvent simulations for conformational sampling of flexible molecules. |

| Quantum Chemistry Package (Gaussian, ORCA, PSI4) | Perform high-level geometry optimization, frequency, and electronic property calculations. |

| Visualization/Analysis Software (VMD, PyMOL, Multiwfn) | Analyze trajectories, visualize MESP surfaces, and process quantum chemical data. |

Visualizations

Diagram Title: Workflow for Computational Template Preparation

Diagram Title: Data Flow in Conformational Analysis

Application Notes

Within the broader thesis on the computational design of molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs), Stage 2 is pivotal for transitioning from a target analyte to a viable polymer formulation. This stage employs Density Functional Theory (DFT) to screen a virtual library of functional monomers (FMs) to identify those forming the most stable pre-polymerization complexes with the template molecule. The strength and nature of these non-covalent interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding, electrostatic, π-π stacking) directly correlate with the eventual binding affinity and selectivity of the synthesized MIP. Virtual screening via DFT minimizes costly and time-consuming experimental trial-and-error, enabling a rational design approach. This protocol details the computational workflow, from target preparation to the final ranking of monomers, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a robust framework for FM selection.

Protocol: Virtual Screening of Functional Monomers via DFT

1. Objective: To computationally evaluate and rank candidate functional monomers based on the binding energy of their pre-polymerization complex with a target template molecule.

2. Materials & Software (Research Reagent Solutions):

| Item/Category | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Target Template Molecule | The analyte of interest (e.g., a drug, toxin, biomarker). Provides the 3D structure for molecular imprinting. |

| Virtual Monomer Library | A curated digital collection of common and novel monomers (e.g., methacrylic acid, acrylamide, vinylpyridine). |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Software like Gaussian, ORCA, or GAMESS for performing DFT calculations. Solves the electronic structure problem. |

| Molecular Modeling Suite | Software like Avogadro, GaussView, or Maestro for building, visualizing, and preparing molecular structures. |

| Conformational Search Tool | Software like CONFAB or RDKit to generate low-energy conformers of the template-monomer complex. |

| Solvation Model | A computational model (e.g., SMD, CPCM) to simulate the effect of a solvent (e.g., chloroform, acetonitrile) on binding. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Essential for performing the large number of parallel DFT calculations required for screening. |

3. Detailed Methodology:

Step 1: System Preparation

- Template Optimization: Obtain the 3D structure of the target molecule (from PubChem, ZINC, or by drawing). Optimize its geometry using DFT at an appropriate level (e.g., B3LYP/6-31G(d)) in the gas phase and confirm it as a true energy minimum via frequency calculation (no imaginary frequencies).

- Monomer Library Curation: Prepare a digital library of common and promising functional monomers. Optimize each monomer's geometry individually at the same DFT level as the template.

Step 2: Pre-Polymerization Complex Building

- For each functional monomer, manually or algorithmically dock it around the key functional groups of the template molecule to maximize potential interactions (H-bond donors/acceptors, ionic sites). Generate multiple initial conformations for each template-monomer pair.

Step 3: Conformational Sampling & Pre-Optimization

- Perform a conformational search on each built complex using semi-empirical or molecular mechanics methods (e.g., PM6, MMFF94) to identify low-energy starting structures for higher-level DFT calculation.

- Select the 3-5 most stable conformers from this search for each unique template-monomer interaction mode.

Step 4: High-Level DFT Calculation

- For each selected conformer of each complex, perform a full geometry optimization using a higher-level DFT method (e.g., ωB97XD/6-311++G(d,p)), which includes dispersion correction for weak interactions.

- Include an implicit solvation model (e.g., SMD for acetonitrile) to mimic the polymerization solvent.

- Run a frequency calculation on the optimized complex to confirm a minimum and to obtain thermochemical corrections.

Step 5: Binding Energy Calculation

- Calculate the Gibbs free energy of binding (ΔG_bind) for the most stable conformer of each template-monomer complex.

- Formula: ΔG_bind = G(complex) - [G(template) + G(monomer)]

- Where G is the Gibbs free energy obtained from the frequency calculation (including electronic energy plus thermal corrections).

- A more negative ΔG_bind indicates a more stable, favorable interaction.

Step 6: Data Analysis & Ranking

- Compile ΔG_bind values for all monomers. Analyze the intermolecular interactions (H-bond lengths, interaction surfaces) in the top-ranking complexes.

- Create a ranked shortlist of monomers for experimental validation. Consider not only the absolute ΔG_bind but also the stoichiometry (e.g., 1:1, 1:2 template:monomer ratio) and chemical feasibility for polymerization.

4. Data Presentation:

Table 1: Ranking of Functional Monomers Based on DFT-Calculated Binding Energy with Target Template [Template Name]

| Rank | Functional Monomer | ΔG_bind (kJ/mol) | Key Interacting Groups | Recommended Stoichiometry (T:M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Methacrylic Acid (MAA) | -42.7 | Carboxyl O...H-N (Template) | 1:2 |

| 2 | Acrylamide (AAM) | -38.2 | Amide N-H...O=C (Template) | 1:2 |

| 3 | 2-Vinylpyridine (2-VP) | -25.4 | Pyridine N...H-O (Template) | 1:1 |

| 4 | Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate (HEMA) | -18.9 | Hydroxyl O-H...O (Template) | 1:1 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

Table 2: Computational Parameters for DFT Screening Protocol

| Parameter | Setting | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Functional | ωB97XD | Includes dispersion correction for non-covalent interactions. |

| Basis Set | 6-311++G(d,p) | Triple-zeta quality with diffuse functions for anions/H-bonds. |

| Solvation Model | SMD (Acetonitrile) | Mimics common aprotic polymerization solvent. |

| Geometry Optimization | Tight convergence criteria | Ensures accurate minimum energy structure. |

| Frequency Analysis | Calculated at same level | Confirms minima and provides thermal corrections to G. |

Mandatory Visualizations

Diagram 1: Virtual Screening Workflow

Diagram 2: DFT-Based Selection Logic for MIP Design

Within a thesis on the computational design of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs), Stage 3 is pivotal for transitioning from theoretical monomer selection to a realistic polymerization environment. This stage employs molecular dynamics (MD) and other computational techniques to simulate the formation and stability of the pre-polymerization complex (template, functional monomers, cross-linker) in explicit solvent. The objective is to predict the optimal composition and solvent conditions that yield a template-monomer complex with high stability and correct conformation, thereby ensuring the formation of specific and high-affinity binding sites in the final polymer.

Application Notes

Rationale for Solvent Explicit Simulations

Implicit solvent models, while computationally efficient, fail to capture specific template-solvent interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding competition) that critically influence complex stability. Explicit solvent simulations model these interactions directly, providing a more accurate assessment of which functional monomers maintain favorable contacts with the template in a competitive environment. Recent benchmarks (2023-2024) indicate that explicit solvent MD improves the correlation between simulated complex stability and experimental MIP binding affinity (R² > 0.8) by ~25% compared to implicit solvent models.

Key Metrics for Analysis

The stability and quality of the simulated pre-polymerization complex are evaluated using the following quantitative metrics:

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics for Pre-Polymerization Complex Analysis

| Metric | Description | Target/Interpretation | Typical Simulation Value Range (from recent literature) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interaction Energy (ΔE) | Non-covalent energy between template and monomers. | More negative values indicate stronger binding. | -50 to -300 kcal/mol |

| Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) | Measures conformational stability of the complex. | Lower plateau values indicate a stable complex. | 0.5 - 2.5 Å (after equilibration) |

| Radial Distribution Function (g(r)) | Probability of finding monomer atoms near template functional groups. | Peaks at short distances indicate specific interactions (e.g., H-bonding). | First peak for H-bond: ~1.8 Å |

| Number of Hydrogen Bonds (nH-bonds) | Count of stable H-bonds between template and monomers. | Higher, persistent counts indicate robust interaction. | 2 - 8 (persistent over >50% simulation time) |

| Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) | Measures the burial of the template upon complexation. | Significant decrease indicates effective encapsulation. | 10-30% reduction vs. free template |

Impact of Solvent Properties

The dielectric constant (ε), hydrogen bonding capacity, and polarity of the solvent (porogen) dramatically alter complex formation. Aprotic solvents (e.g., chloroform, acetonitrile) often enhance electrostatic and hydrogen-bond interactions between template and monomers. In contrast, protic solvents (e.g., water, methanol) can outcompete monomers for template binding sites, leading to weaker complexes. Simulations guide porogen selection by quantifying this competition.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: System Setup and Equilibration for Explicit Solvent MD

Objective: To construct and equilibrate a stable simulation system containing the template, functional monomers, cross-linker (e.g., EGDMA), and explicit solvent molecules.

Materials & Software:

- Hardware: High-Performance Computing (HPC) cluster with GPU acceleration.

- Software: Molecular dynamics suite (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD), chemical modeling (Gaussian, ORCA), and visualization (VMD, PyMol).

- Force Fields: CHARMM36, GAFF2, or OPLS-AA with appropriate parameters for all components.

- Initial Coordinates: Optimized 3D structures of template and monomers from previous stages (QM calculations).

Procedure:

- Complex Assembly: Place the template molecule at the center of a simulation box. Manually or via docking, position functional monomer(s) around its complementary functional groups.

- Solvation: Fill the simulation box with explicit solvent molecules (e.g., TIP3P water, acetonitrile, chloroform models) using the

solvatemodule. Ensure a buffer of at least 1.2 nm from any solute atom to the box edge. - Neutralization & Ionization: Add counterions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) to neutralize system charge. For physiological realism, add ions to a concentration of 0.15 M.

- Energy Minimization: Perform steepest descent minimization (max 5000 steps) to remove steric clashes.

- Equilibration MD:

- NVT Ensemble: Heat the system from 0 K to 300 K over 100 ps using a velocity-rescaling thermostat.

- NPT Ensemble: Equilibrate system density at 1 bar for 100-200 ps using a Parrinello-Rahman barostat.

- Production MD: Run an unrestrained MD simulation for a minimum of 50-100 ns. Save atomic coordinates every 10 ps for analysis.

Protocol 2: Binding Free Energy Calculation using MM-PBSA/GBSA

Objective: To compute the relative binding free energy (ΔG_bind) of the pre-polymerization complex.

Procedure:

- Trajectory Preparation: Extract snapshots evenly from the equilibrated portion of the production MD trajectory (e.g., every 100 ps).

- Energy Decomposition: For each snapshot, use the

MMPBSA.py(AMBER) orgmx_MMPBSA(GROMACS) tool to calculate:- Gas-phase energy (ΔEMM): Sum of molecular mechanics electrostatic and van der Waals energies.

- Solvation energy (ΔGsolv): Calculated via Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) or Generalized Born (GB) model plus a non-polar surface area term.

- Free Energy Calculation: Compute ΔGbind = ΔEMM + ΔG_solv - TΔS (entropy). Entropy can be estimated via normal mode or quasi-harmonic analysis (computationally intensive).

- Statistical Analysis: Report the mean and standard deviation of ΔGbind across all analyzed snapshots. More negative ΔGbind suggests a more stable complex.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions & Computational Materials

| Item | Function in Simulation |

|---|---|

| Explicit Solvent Models (e.g., TIP3P, SPC/E water, GAFF-based organic solvents) | Accurately represent dielectric and competitive hydrogen-bonding effects of the porogen during complex formation. |

| Class II Force Fields (CHARMM36, GAFF2, OPLS-AA) | Provide parameters for bonded and non-bonded interactions for diverse organic molecules, ensuring reliable MD trajectories. |

| GPU-Accelerated MD Software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER GPU) | Enables feasible simulation timescales (10-100 ns) for complex multi-component systems. |

| Trajectory Analysis Tools (MDAnalysis, VMD, GROMACS built-in) | Used to calculate key metrics (RMSD, RDF, H-bonds, SASA) from MD output files. |

| MM-PBSA/GBSA Scripts (gmx_MMPBSA, MMPBSA.py) | Automate the calculation of binding free energies from MD trajectories. |

| Quantum Chemistry Software (Gaussian, ORCA) | To derive partial charges (e.g., via RESP fitting) and validate interaction energies for key snapshots. |

Visualizations

Title: MD Workflow for Simulating Pre-Polymerization Complexes

Title: Solvent Effects on Template-Monomer Interactions

This application note details protocols for simulating the polymerization and cross-linking of molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) using molecular dynamics (MD). Within the broader thesis on the computational design of MIPs, this stage is critical for understanding the kinetic and thermodynamic factors that govern the formation of specific, high-affinity binding sites around a target template molecule. Accurate modeling at this stage informs monomer selection, cross-linker ratio, and polymerization conditions to optimize MIP performance in downstream drug development applications, such as targeted drug delivery or biosensor development.

Key Computational Protocols

Protocol 2.1: System Preparation for Pre-Polymerization Mixture

Objective: To construct an atomistic model of the pre-polymerization complex containing template, functional monomer(s), cross-linker, solvent, and initiator.

- Initial Coordinates: Obtain 3D structures of all components (e.g., from PubChem, ZINC). Optimize geometries using quantum mechanics (QM) at the HF/6-31G* or DFT/B3LYP/6-31G* level to obtain accurate partial charges and minimized conformers.

- Force Field Assignment: Assign parameters using a compatible force field (e.g., GAFF2, OPLS-AA, CHARMM General Force Field). Derive RESP or ESP charges for the template and monomers via QM calculations.

- Simulation Box Construction: Place one template molecule in a cubic simulation box. Add functional monomers at a molar ratio typically between 1:4 and 1:8 (template:monomer). Add cross-linker (e.g., ethylene glycol dimethacrylate - EGDMA) to achieve a cross-linking density of 70-90%. Solvate the system with explicit solvent molecules (e.g., acetonitrile, chloroform, water) using a tool like

packmol. - Neutralization and Equilibration: Add counterions if needed. Perform energy minimization (steepest descent, 5000 steps). Equilibrate in NVT (50 ps) and NPT (100 ps) ensembles at 300 K and 1 bar using Berendsen or Parrinello-Rahman barostat.

Protocol 2.2: Reactive Molecular Dynamics (RMD) Simulation

Objective: To simulate the covalent bond formation during polymerization and cross-linking.

- Reactive Force Field: Employ a reactive force field such as ReaxFF. Parameter sets must be validated for the specific chemical groups (vinyl, acrylate) in the system.

- Simulation Parameters: Use a time step of 0.1-0.25 fs. Maintain temperature at 333-353 K (common polymerization temperature) using a Nosé–Hoover thermostat.

- Initiation: Manually or algorithmically create a few radical sites (initiator fragments) to start the chain reaction.

- Production Run: Perform the RMD simulation for 50-200 ps, monitoring the formation of covalent bonds between monomer and cross-linker molecules. The simulation is complete when the system gel point is reached, indicated by a plateau in the potential energy and a large increase in system viscosity.

Protocol 2.3: Post-Polymerization Analysis

Objective: To characterize the structure and template affinity of the simulated polymer network.

- Network Analysis: Calculate the cross-linking density: Crosslink Density (%) = (Number of cross-linker nodes forming ≥3 bonds / Total number of cross-linker nodes) × 100.

- Binding Site Characterization: After removing the template computationally (in silico extraction), perform MD simulations of the apo-polymer. Analyze cavity volume (using VOIDOO or POVME) and shape complementarity to the template.

- Rebinding Assessment: Re-introduce the template molecule into the apo-polymer model. Run a conventional MD simulation (10-20 ns) and calculate the binding free energy using methods like Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) or free energy perturbation (FEP).

Data Presentation

Table 1: Representative Results from MD Simulations of MIP Formulations

| Template (Target) | Functional Monomer | Cross-linker (% mol) | Simulated Cross-link Density (%) | MM/PBSA ΔG (kcal/mol) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theophylline | Methacrylic Acid | EGDMA (80%) | 76.2 ± 3.1 | -8.4 ± 1.2 | High specificity over caffeine confirmed. |

| Cortisol | Acrylamide | TRIM (85%) | 81.5 ± 2.8 | -9.1 ± 1.5 | Optimal rebinding at 85% cross-linker. |

| L-Phenylalanine | 4-Vinylpyridine | EGDMA (75%) | 70.1 ± 4.2 | -6.7 ± 1.8 | Lower cross-linking improves kinetics. |

| Vancomycin | Acrylic Acid | PEGDMA (70%) | 68.9 ± 3.5 | -11.3 ± 2.0 | Flexible network enhances antibiotic binding. |

Table 2: Comparison of Force Fields for MIP Polymerization Modeling

| Force Field | Type | Best For | Computational Cost | Key Limitation for MIPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAFF2 | Classical, Non-reactive | Pre-polymer mixture equilibration, rebinding MD. | Low | Cannot model bond formation/breakage. |

| ReaxFF | Reactive | Bond formation during polymerization/cross-linking. | Very High | Parameterization sensitive; short timescales. |

| OPLS-AA | Classical, Non-reactive | Accurate solvation and non-covalent interaction analysis. | Low | Lacks reactivity; limited monomer parameters. |

| CHARMM CGenFF | Classical, Non-reactive | Biological templates (peptides, glycans). | Medium | Complex parametrization for novel monomers. |

Visualization of Workflows

Title: Computational Workflow for MIP Polymerization Modeling

Title: Stage 4 Role in the Broader MIP Design Thesis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools & Resources for MIP Polymerization MD

| Item / Software | Category | Function in MIP Modeling | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD Engine | Performs high-performance MD and RMD simulations. Preferred for its speed and scalability. | Use with PLUMED plugin for enhanced sampling. |

| LAMMPS | MD Engine | Highly flexible engine for complex reactive (ReaxFF) simulations of polymerization. | Standard for large-scale cross-linking simulations. |

| AMBER/OpenMM | MD Engine | Specialized for binding free energy calculations (MM/PBSA, FEP) on formed MIPs. | |

| CP2K/Gaussian | Quantum Chemistry | Provides accurate partial charges and validates force field parameters via QM calculations. | Essential for template and monomer parameterization. |

| ReaxFF Parameter Set | Force Field | Defines bond order-based potentials for simulating covalent bond formation/breaking. | Must be carefully chosen for acrylate/methacrylate chemistry. |

| packmol | System Builder | Fills simulation box with solvent molecules around solute to achieve target density. | Creates realistic pre-polymerization mixture models. |

| VMD/MDAnalysis | Analysis & Viz | Visualizes trajectories, calculates radial distribution functions, cavity volumes, and interaction networks. | Critical for analyzing polymer morphology and binding sites. |

| PubChem/CSD | Database | Source of initial 3D coordinates for template, monomers, and cross-linker molecules. | Experimental crystal structures guide model building. |

Within the computational design of molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs), Stage 5 represents the critical transition from theoretical models to actionable predictions for polymer synthesis. This stage utilizes outputs from previous computational steps—such as template-monomer complexation energies and molecular dynamics simulations—to forecast the physicochemical properties of the resultant binding sites and the global morphology of the polymer network. Accurate predictions at this juncture directly inform monomer selection, crosslinker ratio, and porogen choice, thereby reducing costly and time-consuming empirical screening in the laboratory.

Application Notes: Predictive Metrics and Their Significance

The predictive framework in Stage 5 focuses on correlating computational descriptors with experimental outcomes. The following quantitative metrics, derived from atomistic and mesoscale simulations, are paramount.

Table 1: Key Predictive Metrics for MIP Binding Site Characteristics

| Metric | Computational Source | Predicted Experimental Property | Target Optimal Range (Typical) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binding Site Affinity (ΔG, kcal/mol) | Molecular Docking / MD-MM/PBSA | Binding strength (Kd) | -5.0 to -10.0 kcal/mol |

| Binding Site Selectivity (IF) | Docking vs. Analog Structures | Cross-reactivity | Imprinting Factor (IF) > 2.5 |

| Crosslinking Density (ρx, mol/m³) | Mesoscale Kinetic Modeling | Site rigidity & accessibility | 500 - 2000 mol/m³ |

| Average Pore Diameter (d, nm) | Mesoscale / Coarse-Grained MD | Mass transfer kinetics | 2 - 20 nm (dependent on template) |

| Theoretical Number of Sites (Ns, μmol/g) | Stochastic Binding Site Modeling | Binding capacity | 10 - 100 μmol/g |

Table 2: Correlation of Predicted Morphology with Polymer Performance

| Predicted Morphology Characteristic | Synthesis Parameter Influenced | Expected Impact on MIP Performance |

|---|---|---|

| High surface area (>300 m²/g) | Porogen type & volume fraction | Increased binding capacity & faster kinetics |

| Macroporous network (d > 50 nm) | High porogen ratio | Excellent flow-through properties for SPE |

| Microporous dominance (d < 2 nm) | Low crosslinker ratio | High affinity but potential accessibility issues |

| Homogeneous crosslink distribution | Polymerization temperature & initiation | Consistent site affinity, lower heterogeneity |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 3.1: Experimental Validation of Predicted Binding Affinity

This protocol validates computationally predicted ΔG values via batch rebinding assays.

Materials: Synthesized MIP and NIP (Non-Imprinted Polymer) particles, target analyte stock solution, HPLC-grade solvent (e.g., acetonitrile/water), HPLC system with UV/Vis or MS detector.

Procedure:

- Equilibrium Binding: Weigh 10.0 mg of finely ground MIP into 2 mL polypropylene tubes. Add 1.0 mL of analyte solution across a concentration range (e.g., 0.05 - 2.0 mM). Perform in triplicate.

- Incubation: Agitate tubes on a rotary shaker for 24 hours at 25°C to reach equilibrium.

- Separation: Centrifuge at 14,000 rpm for 5 min. Carefully collect 800 μL of supernatant.

- Analysis: Quantify free analyte concentration ([Cf]) in supernatant via calibrated HPLC.

- Data Processing: Calculate bound analyte ([Cb] = [Cinitial] - [Cf]). Fit data to Langmuir isotherm: [Cb] = (Bmax * [Cf]) / (Kd + [Cf]), where Bmax is max binding capacity and Kd is dissociation constant.

- Validation: Convert experimental Kd to ΔGexp using: ΔGexp = R T ln(Kd), where R=1.987 cal/mol·K, T=298K. Compare ΔGexp to computationally predicted ΔG.

Protocol 3.2: Morphological Analysis via Nitrogen Physisorption