Bulk vs Surface Polymerization: Strategic Approaches for Optimizing Impurity Adsorption in Pharmaceutical Development

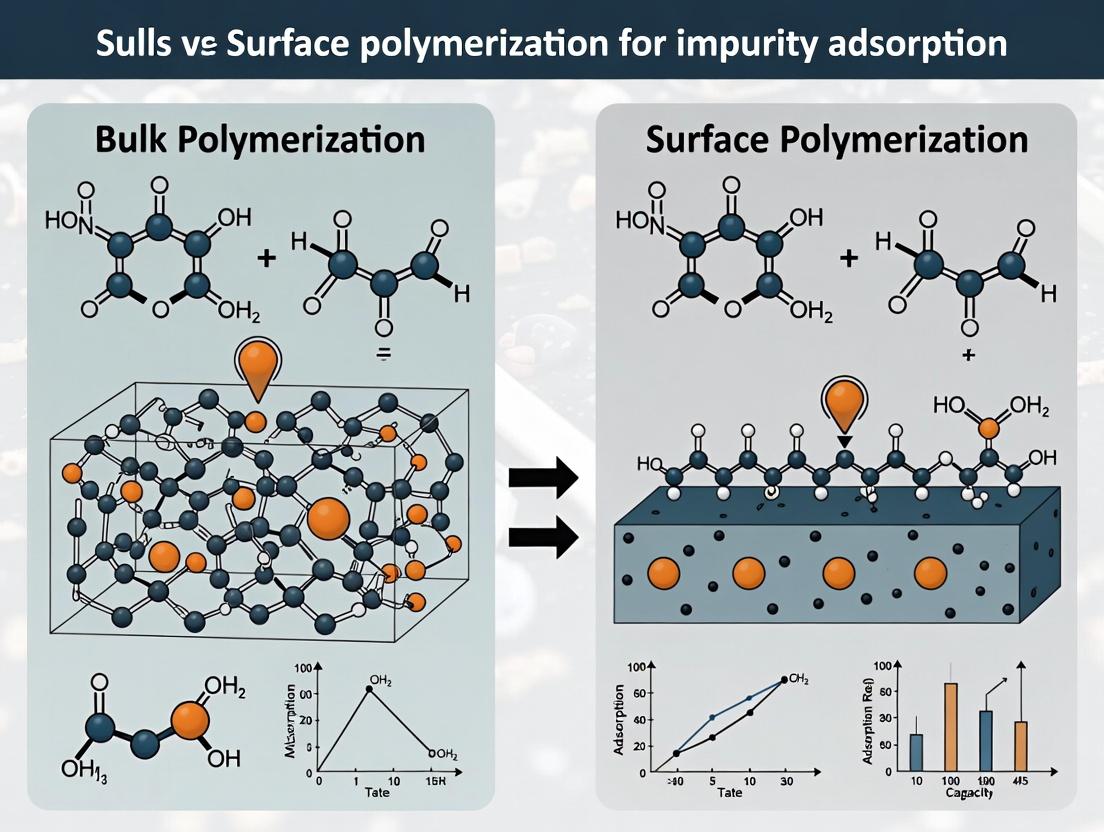

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of bulk and surface polymerization techniques for creating polymeric adsorbents to remove process-related and product-related impurities in drug development.

Bulk vs Surface Polymerization: Strategic Approaches for Optimizing Impurity Adsorption in Pharmaceutical Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of bulk and surface polymerization techniques for creating polymeric adsorbents to remove process-related and product-related impurities in drug development. It explores the foundational science behind each method, details practical application protocols for common impurity challenges (endotoxins, host cell proteins, leachables, product aggregates), addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization parameters, and validates performance through comparative case studies. Aimed at researchers and process scientists, the content synthesizes current literature and best practices to guide the strategic selection and refinement of polymer-based purification strategies for biologics and small molecules, ultimately impacting drug safety, efficacy, and regulatory compliance.

Core Principles: Understanding the Science of Polymer Adsorbents for Impurity Clearance

Within the context of impurity adsorption research, the selection between bulk and surface polymerization strategies defines the physical and chemical battlefield on which materials are synthesized. These techniques dictate critical parameters such as porosity, surface area, functional group accessibility, and mechanical stability of the resultant polymers, directly influencing their adsorption efficiency, kinetics, and selectivity for target impurities in complex matrices like drug formulations.

Core Principles & Comparison

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Bulk vs. Surface Polymerization

| Parameter | Bulk Polymerization | Surface Polymerization (e.g., Grafting-from) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Process | Monomer + initiator polymerized in mass. | Initiator immobilized on substrate; polymer grown from surface. |

| Typical Porosity | Low (non-porous) or macroporous (with porogen). | Highly dependent on substrate; can create thin films or brushes. |

| Surface Area (BET, m²/g) | Low (< 5) for non-porous; High (100-1000) for porous networks. | Variable: Moderate (10-500) depending on graft density & substrate. |

| Functional Group Density | High throughout the bulk. | High, but concentrated at the interface. |

| Mass Transfer Kinetics | Can be slow for non-porous bulk; faster for macroporous. | Typically fast due to thin, accessible layer. |

| Mechanical Stability | High, cross-linked monoliths are robust. | Can be lower; depends on graft/substrate bond strength. |

| Primary Application in Adsorption | High-capacity, batch-mode adsorption of impurities. | Flow-through systems, coatings, selective membranes. |

Table 2: Adsorption Performance Metrics for Model Impurities

| Polymer Type | Synthesis Method | Target Impurity | Max. Adsorption Capacity (mg/g) | Equilibrium Time (min) | Reference Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(HEMA-co-EDMA) Monolith | Bulk (Thermal) | Endotoxin | 12.5 ± 1.8 | 120 | 2023 |

| Poly(NIPAm) Brush on Silica | Surface-Initiated ATRP | Bisphenol A | 45.2 ± 3.1 | 30 | 2024 |

| MIP for β-Lactam Antibiotics | Bulk (Precipitation) | Amoxicillin | 89.7 ± 4.5 | 90 | 2023 |

| Poly(acrylic acid) Grafted Membrane | Surface-Initiated RAFT | Heavy Metal Ions (Pb²⁺) | 156.3 ± 8.2 | < 15 | 2024 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of a Macroporous Bulk Polymer Monolith for Impurity Adsorption

Objective: To create a high-surface-area, cross-linked poly(glycidyl methacrylate-co-ethylene glycol dimethacrylate) [poly(GMA-co-EDMA)] monolith via bulk polymerization for the adsorption of phenolic impurities.

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

- GMA (Glycidyl Methacrylate): Principal monomer providing epoxy functional groups for later modification.

- EDMA (Ethylene Glycol Dimethacrylate): Cross-linker to create a rigid, insoluble porous network.

- Cyclohexanol & 1-Dodecanol (Porogen Mix): Solvent mixture to induce phase separation and create pores.

- AIBN (Azobisisobutyronitrile): Thermal free-radical initiator.

- Toluene (HPLC Grade): Washing solvent to remove porogens and unreacted monomers.

Procedure:

- In a glass vial, mix GMA (24% v/v), EDMA (16% v/v), cyclohexanol (45% v/v), and 1-dodecanol (15% v/v) thoroughly.

- Add AIBN (1% w/w relative to total monomers) and dissolve by sonication.

- Degas the mixture by sparging with nitrogen or argon for 10 minutes.

- Seal the vial and place it in a water bath at 65°C for 24 hours to complete polymerization.

- Carefully break the vial and retrieve the polymer monolith.

- Wash the monolith sequentially with toluene, methanol, and water (500 mL each) over 72 hours using a Soxhlet extractor to remove all porogens and unreacted species.

- Dry the monolith under vacuum at 50°C for 24 hours. Characterize porosity via nitrogen sorption (BET) and microscopy (SEM).

Protocol 2: Surface-Initiated Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization (SI-ATRP) of a Polymer Brush

Objective: To graft a poly(2-(dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate) (PDMAEMA) brush from a silicon wafer substrate for the adsorption of anionic impurities.

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

- ATRP Initiator-Silane (e.g., (11-(2-Bromo-2-methyl)propionyloxy) undecyltrichlorosilane): Provides immobilized initiator sites on the substrate.

- DMAEMA Monomer: Functional monomer providing tertiary amine groups for ionic interaction.

- PMDETA (N,N,N',N'',N''-Pentamethyldiethylenetriamine): Ligand for the ATRP catalyst complex.

- Cu(I)Br: Catalyst for the ATRP reaction.

- Methanol/Toluene Mixture (3:1 v/v): Solvent system for the polymerization.

- Anhydrous Toluene & Ethanol: For substrate cleaning and initiator deposition.

Procedure:

- Clean a silicon wafer with piranha solution (Caution: Extremely corrosive), rinse with water and ethanol, and dry under nitrogen.

- Immerse the wafer in a 1 mM solution of the ATRP initiator-silane in anhydrous toluene for 18 hours under nitrogen atmosphere to form the initiator monolayer.

- Rinse the wafer thoroughly with toluene and ethanol to remove physisorbed silane, then dry under nitrogen.

- In a Schlenk flask, degas a mixture of DMAEMA (10 mL), PMDETA (100 µL), and methanol/toluene (20 mL) by bubbling with nitrogen for 30 minutes.

- Add Cu(I)Br (30 mg) to the flask under nitrogen. Allow the catalyst to form the active complex.

- Quickly transfer the initiator-functionalized wafer into the reaction mixture. Seal and let the SI-ATRP proceed at 40°C for a predetermined time (e.g., 2-6 hours) to control brush thickness.

- Remove the wafer and rinse copiously with methanol and water to terminate the reaction and remove physisorbed polymer.

- Characterize brush thickness via ellipsometry and functionality via X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS).

Visualizations

Title: Synthesis Pathways for Bulk and Surface Polymers

Title: Impurity Adsorption Mechanisms Comparison

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in Polymerization & Adsorption Research |

|---|---|

| Cross-linkers (e.g., EDMA, DVB) | Creates three-dimensional network in bulk polymers, providing mechanical stability and defining porosity. Critical for surface grafting density. |

| Porogens (e.g., Cyclohexanol, Toluene) | In bulk polymerization, induces phase separation to create pore structure. Removed post-polymerization to reveal high surface area. |

| Controlled Radical Initiators (e.g., ATRP/RAFT agents) | Enables precise growth of polymer chains with controlled thickness and composition from surfaces (SI-ATRP, SI-RAFT). |

| Functional Monomers (e.g., GMA, MAA, DMAEMA) | Provide the specific chemical groups (epoxy, carboxyl, amine) responsible for impurity binding via covalent, ionic, or affinity interactions. |

| Silane Coupling Agents (e.g., ATRP-initiator silane) | Forms a covalent bond between inorganic substrates (SiO₂, metals) and organic polymer initiators, enabling robust surface grafting. |

| Metal Catalyst Systems (e.g., Cu(I)/Ligand) | Catalyzes controlled radical polymerization reactions (e.g., ATRP). Requires careful removal post-synthesis for adsorption applications. |

| Molecular Templates (for MIPs) | Used in bulk/precipitation polymerization to create molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) with shape-specific cavities for target impurity recognition. |

Introduction and Thesis Context Within the research paradigm comparing bulk versus surface polymerization for designing advanced adsorbents, a critical question emerges: how do the fundamental properties of the synthesized polymer dictate its capacity to bind specific impurities? This application note details how systematic investigation of polymer morphology (physical structure) and chemistry (functional groups) reveals the governing mechanisms of impurity adsorption. This knowledge directly informs the choice between bulk polymerization (yielding particles with defined bulk morphology) and surface polymerization (creating thin films on substrates) for target applications in drug purification and impurity clearance.

Key Polymer Properties Dictating Adsorption

The efficacy of a polymeric adsorbent is governed by an interplay of morphological and chemical factors. The following table summarizes the primary properties and their influence.

Table 1: Morphological and Chemical Properties Governing Adsorption

| Property | Description | Influence on Impurity Binding | Typical Characterization Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specific Surface Area (m²/g) | Total accessible area per mass. | Higher area provides more binding sites, crucial for small impurities. | BET (Brunauer-Emmett-Teller) N₂ adsorption. |

| Pore Size Distribution | Volume of micro- (<2 nm), meso- (2-50 nm), and macropores (>50 nm). | Micropores: small molecules. Mesopores: larger organics, peptides. Macropores: facilitate diffusion. | N₂ adsorption/desorption isotherms (BJH method). |

| Particle Size & Shape | Diameter and geometry of polymer beads or film thickness. | Smaller particles/thinner films reduce diffusion path length. Shape affects flow dynamics. | Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS). |

| Swelling Ratio | Volume change in solvent. | High swelling increases intraparticle diffusion but may reduce mechanical stability. | Gravimetric analysis in target solvent. |

| Surface Functional Groups | Chemical moieties (e.g., -OH, -COOH, -N⁺R₃, -C₆H₅) at the interface. | Dictates binding mechanism: hydrogen bonding, electrostatic, hydrophobic, π-π interactions. | Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS). |

| Hydrophilicity/Hydrophobicity | Affinity for water vs. organic solvents. | Determines compatibility with solvent and selectivity for hydrophobic/hydrophilic impurities. | Water Contact Angle measurement. |

Experimental Protocols for Mechanism Elucidation

Protocol 2.1: Synthesis of Model Polymers via Bulk vs. Surface Polymerization Objective: To create polymers with controlled morphology and chemistry for comparative adsorption studies. Materials: Monomer (e.g., styrene, methyl methacrylate, functional monomer like vinylpyridine), cross-linker (divinylbenzene), initiator (AIBN), porogen (toluene, cyclohexanol), substrate for surface polymerization (silica beads, sensor chip). Procedure for Bulk Polymerization:

- Prepare a mixture of monomer (80% v/v), cross-linker (20% v/v), and porogen (50% v/v relative to monomers). Add 1 wt% AIBN initiator.

- Degas via nitrogen bubbling for 15 minutes.

- Polymerize at 70°C for 24 hours in a sealed vial.

- Crush the resulting monolith, wash sequentially with THF, methanol, and water, then sieve to obtain 50-100 µm particles.

- Dry under vacuum at 50°C. Procedure for Surface-Initiated Polymerization (Grafting-from):

- Silanize substrate (e.g., silica beads) with an initiator-bearing silane (e.g., ATRP initiator).

- Immerse initiator-functionalized substrate in a degassed solution of monomer, cross-linker (lower %, e.g., 5%), and porogen in solvent.

- Activate polymerization (via ATRP catalyst or thermal initiation) for a controlled time (e.g., 2-4h) to form a thin film.

- Wash thoroughly and dry.

Protocol 2.2: Batch Adsorption Isotherm Experiment Objective: To quantify impurity binding capacity and affinity. Materials: Model polymer (from Protocol 2.1), target impurity solution (e.g., benzodiazepine in ethanol, endotoxin in buffer), HPLC vials, orbital shaker, HPLC or UV-Vis spectrometer. Procedure:

- Precisely weigh 10 mg of polymer into 2 mL HPLC vials (n=6).

- Prepare a dilution series of the impurity (e.g., 5, 10, 25, 50, 100, 200 µg/mL).

- Add 1 mL of each concentration solution to the polymer vials. Prepare triplicate controls (solution without polymer).

- Seal vials and agitate at 25°C for 24h to reach equilibrium.

- Centrifuge and analyze supernatant concentration (Cₑ, µg/mL).

- Calculate: qₑ = (C₀ - Cₑ) * V / m, where qₑ is adsorbed amount (µg/mg), C₀ is initial concentration, V is volume (L), m is mass (mg).

- Fit data to Langmuir or Freundlich isotherm models.

Protocol 2.3: Kinetics of Adsorption and Diffusion Analysis Objective: To determine the rate of adsorption and identify the rate-limiting step (surface binding vs. pore diffusion). Materials: As in 2.2, with emphasis on precise timekeeping. Procedure:

- Weigh 50 mg polymer into a flask with 50 mL of impurity solution at a known concentration.

- Stir continuously. At fixed time intervals (e.g., 1, 3, 5, 10, 20, 40, 60, 120 min), withdraw 500 µL aliquots.

- Immediately filter (0.2 µm) and analyze residual concentration (Cₜ).

- Calculate: qₜ = (C₀ - Cₜ) * V / m.

- Fit data to Pseudo-First-Order and Pseudo-Second-Order kinetic models. Analyze initial data with the Weber-Morris intraparticle diffusion model.

Visualization of Research Workflow and Mechanisms

Title: Polymer Adsorbent Research Workflow

Title: Morphology & Chemistry Drive Binding Mechanisms

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Polymer Adsorption Research

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Divinylbenzene (DVB) | Cross-linking agent for creating rigid, porous polymer networks. Controls swelling and stability. |

| Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) | Thermal free-radical initiator for standard bulk polymerization reactions. |

| Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization (ATRP) Kit | Enables controlled surface-initiated polymerization for uniform thin films. |

| Porogens (Toluene, Cyclohexanol) | Inert solvents that create pore structure during polymerization; removed post-synthesis. |

| Functional Monomers (e.g., 4-Vinylpyridine, Methacrylic Acid) | Introduce specific chemical groups (basic pyridine, acidic carboxyl) for tailored interactions. |

| Model Impurity Standards | High-purity compounds (e.g., phenol, benzodiazepines, endotoxin) for controlled adsorption studies. |

| Silica Microspheres (3-10 µm) | Common substrate for grafting surface polymers, providing a well-defined base morphology. |

| BET Surface Area Analyzer | Instrument to quantify specific surface area and pore size distribution via gas adsorption. |

Application Notes on Impurity Targets

Endotoxins (Lipopolysaccharides, LPS)

Endotoxins are pyrogenic components of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. Their presence in biologics can cause severe febrile reactions in patients. In the context of bulk vs. surface polymerization research, adsorbents designed for endotoxin removal must address their high negative charge and amphiphilic nature. Bulk polymerized resins with tailored pore architectures are effective for capturing larger LPS aggregates, while surface-functionalized membranes excel in high-throughput, flow-through applications.

Host Cell Proteins (HCPs)

HCPs are a complex mixture of proteins co-produced with the recombinant therapeutic protein. Their persistence can elicit immunogenic responses. Effective removal requires adsorbents with broad selectivity. Bulk polymerized materials with heterogeneous, multimodal surfaces can bind a wider spectrum of HCP isoforms due to varied interaction sites. Surface-polymerized layers on base matrices offer more defined, ligand-specific removal but may have lower capacity for diverse HCP populations.

Aggregates

Protein aggregates, ranging from dimers to large sub-visible particles, are critical quality attributes due to their heightened immunogenicity risk. Separation often relies on size exclusion and hydrophobic interactions. Monolithic columns produced via bulk polymerization provide superior convective mass transfer for aggregate removal in flow-through mode. Surface-grafted polymeric brushes can be engineered to selectively repel aggregates via steric exclusion.

Leachables

Leachables are chemical compounds that migrate from processing components (e.g., filters, chromatography resins, tubing) into the product stream. Adsorbents for leachable removal, such as activated carbon or polymeric scavengers, benefit from high surface area. Bulk polymerized porous carbons offer high capacity for diverse organic leachables, while surface-imprinted polymers can be designed for specific, high-affinity capture of known problematic leachables like ligands from affinity resins.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Bulk vs. Surface Polymerization Adsorbents for Key Impurities

| Impurity Target | Typical Specification | Bulk Polymerization Adsorbent (Dynamic Binding Capacity*) | Surface Polymerization Adsorbent (Dynamic Binding Capacity*) | Key Removal Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endotoxins | <0.1 EU/mg | 1-2 x 10⁶ EU/mL resin | 5-10 x 10⁵ EU/mL membrane | Ionic/Hydrophobic Interaction |

| HCPs | <10-100 ppm | 10-30 mg HCP/mL resin (broad spectrum) | 5-15 mg HCP/mL resin (targeted) | Multimodal/ Affinity Interaction |

| Aggregates | <1.0% | >95% removal (high molecular weight) | >99% removal (specific size cut-off) | Size Exclusion / Steric Repulsion |

| Leachables | ppb to ppm levels | High capacity (e.g., 50 mg/g for model leachable Tri-n-butyl phosphate) | Selective capacity (e.g., 20 mg/g for Protein A ligand) | Hydrophobic / Molecular Imprinting |

Note: Values are representative ranges from current literature and vendor data sheets. Actual capacity depends on polymer chemistry, feedstock, and process conditions.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Evaluating HCP Removal with a Novel Bulk Polymerized Multimodal Resin

Objective: Determine the dynamic binding capacity (DBC) of a bulk polymerized adsorbent for a complex HCP mixture. Materials: Bulk polymerized multimodal resin (e.g., prototype poly(acrylate-co-vinylamine) beads), clarified CHO cell harvest, binding buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4), elution buffer (50 mM Tris, 1 M NaCl, pH 7.4), HPLC system, HCP ELISA kit. Procedure:

- Column Packing: Pack a 1 mL TRICORN column with the bulk polymerized resin per manufacturer's instructions. Equilibrate with 10 CV of binding buffer.

- Load Preparation: Adjust clarified harvest to conductivity/pH matching binding buffer. Filter through a 0.22 µm membrane.

- Breakthrough Analysis: Load the adjusted harvest onto the column at a linear velocity of 150 cm/h. Collect flow-through fractions.

- DBC Determination: Quantify HCP concentration in flow-through fractions via ELISA. The DBC at 10% breakthrough (DBC₁₀) is calculated as:

DBC₁₀ = (Loaded HCP at 10% breakthrough) / (Resin volume). - Elution: Strip bound material with 5 CV of elution buffer. Regenerate and sanitize.

Protocol: Assessing Leachable Scavenging by Surface-Imprinted Polymers

Objective: Measure the binding kinetics and capacity of a surface-grafted, molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) for a target leachable (e.g., Protein A ligand). Materials: Surface-MIP functionalized beads (base matrix: silica, graft layer: methacrylic acid-co-ethylene glycol dimethacrylate), control non-imprinted polymer (NIP) beads, spiked buffer solution with known concentration of target leachable, LC-MS/MS system. Procedure:

- Batch Binding: In triplicate, add 10 mg of MIP or NIP beads to 1 mL of spiked solution in a microcentrifuge tube. Incubate with mixing for set times (e.g., 5, 15, 30, 60, 120 min).

- Separation: At each time point, centrifuge tubes and collect supernatant.

- Analysis: Quantify the remaining free leachable concentration in the supernatant using a validated LC-MS/MS method.

- Calculation: Calculate amount bound per mg of polymer at each time point. Plot to determine kinetic parameters and saturation capacity.

- Specificity Test: Repeat with structurally similar compounds to assess selectivity of the MIP layer.

Diagrams

Title: Adsorbent Selection Workflow for Impurity Removal

Title: Endotoxin Immunogenic Signaling Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents & Materials for Impurity Adsorption Studies

| Item | Function in Research | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| CHO HCP ELISA Kit | Quantifies total host cell protein concentration in process samples. Critical for assessing HCP clearance by adsorbents. | Commercial kits from Cygnus, F550, etc. |

| Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) Assay Kit | Gold-standard for detecting and quantifying endotoxin (LPS) levels. | Gel-clot, chromogenic, or turbidimetric formats. |

| Size-Exclusion HPLC (SE-HPLC) Columns | Separates and quantifies protein monomers, fragments, and aggregates. | TSKgel, BioResolve, etc. |

| LC-MS/MS System | Identifies and quantifies specific leachables, HCP species, and chemical impurities with high sensitivity. | Triple quadrupole or high-resolution mass spectrometers. |

| Bulk Polymerization Monomers | Building blocks for creating porous, high-capacity adsorbent resins. | e.g., Styrene, divinylbenzene, glycidyl methacrylate. |

| Surface Grafting Initiators | Enable controlled radical polymerization from base matrix surfaces for thin film creation. | e.g., Azo-initiators, atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) initiators. |

| Model Impurity Solutions | Defined mixtures for controlled adsorption experiments. | e.g., Purified LPS, spiked leachable standards, aggregate-enriched mAb samples. |

| Robotic Liquid Handlers | Automates high-throughput screening of adsorption conditions and polymer chemistries. | Essential for Design of Experiments (DoE). |

The development of high-performance adsorbents for impurity removal in pharmaceutical manufacturing hinges on the precise engineering of material properties. Within the broader research thesis comparing bulk versus surface polymerization strategies, the triad of porosity, surface area, and functional group density emerges as the critical determinant of adsorption capacity, kinetics, and selectivity. Bulk polymerization often produces materials with high functional group loadings but may suffer from diffusion limitations due to poor pore connectivity. Conversely, surface polymerization on pre-formed porous substrates can optimize accessibility but may limit total active site density. This application note details protocols and analyses for characterizing this "trinity" to guide rational adsorbent design.

Quantitative Comparison of Adsorbent Materials

The following table summarizes key performance data for representative adsorbents synthesized via bulk and surface polymerization techniques, as reported in recent literature (2023-2024).

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Model Adsorbents for Pharmaceutical Impurity (e.g., Genotoxic Nitrosamine) Removal

| Adsorbent Type & Synthesis Method | BET Surface Area (m²/g) | Total Pore Volume (cm³/g) | Average Pore Width (nm) | Functional Group Density (mmol/g) | Adsorption Capacity for N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) (mg/g) | Key Reference (Recent) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypercrosslinked Polymer (Bulk) | 1200 - 1800 | 1.0 - 1.8 | 1.5 - 3.0 | 4.5 - 6.0 (aryl groups) | 120 - 180 | Micropor. Mesopor. Mat., 2023, 359, 112663 |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (Bulk) | 350 - 600 | 0.4 - 0.7 | 8.0 - 15.0 | 1.8 - 3.2 (carboxy) | 85 - 110 (high selectivity) | Chem. Eng. J., 2024, 481, 148552 |

| Grafted Polymer on Mesoporous Silica (Surface) | 450 - 700 | 0.7 - 1.1 | 6.0 - 10.0 | 2.0 - 3.5 (amine/thiol) | 95 - 130 | J. Hazard. Mater., 2023, 441, 129842 |

| Polymerized Ionic Liquid on Carbon (Surface) | 900 - 1100 | 0.9 - 1.3 | 2.0 - 4.0 | 3.0 - 4.5 (ionic groups) | 140 - 170 | ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2024, 16, 5, 6741 |

| Metal-Organic Framework (Bulk-like) | 1500 - 3000 | 0.7 - 1.4 | 0.8 - 2.5 | 7.0 - 10.0 (open metal sites) | 200 - 250 (humid sensitivity) | Sci. Adv., 2023, 9, eadi6566 |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Synthesis of Amine-Functionalized Adsorbent via Surface-Initiated ATRP

This protocol details the grafting of poly(glycidyl methacrylate) with post-modification to introduce amine groups onto silica substrate.

I. Materials & Reagents:

- Mesoporous silica SBA-15 (pore size ~8 nm).

- (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES), 99%.

- 2-Bromoisobutyryl bromide (BiBB), 98%.

- Glycidyl methacrylate (GMA), purified via inhibitor remover.

- Copper(I) bromide (CuBr), purified by acetic acid washing.

- N,N,N',N'',N''-Pentamethyldiethylenetriamine (PMDETA), 99%.

- Anhydrous toluene and tetrahydrofuran (THF).

- Ethylenediamine for post-grafting ring-opening.

II. Procedure:

- Silica Amine-Functionalization: Suspend 2.0 g of SBA-15 in 100 mL anhydrous toluene. Add 4 mL APTES. Reflux under N₂ for 24h. Cool, filter, and wash with toluene, methanol, and dry under vacuum.

- Initiator Immobilization: Under N₂, suspend aminated silica in 80 mL anhydrous THF in an ice bath. Add 3 mL BiBB dropwise. Stir for 24h at 0°C, then RT. Filter, wash with THF, dry.

- Surface-Initiated ATRP: In a Schlenk flask, degas 20 mL GMA, 20 mL toluene, 0.1 g CuBr, and 0.2 mL PMDETA by three freeze-pump-thaw cycles. Add 1.0 g initiator-functionalized silica. Seal and stir at 60°C for 6h. Quench in liquid N₂.

- Work-up: Dilute with THF, filter. Wash polymer-grafted silica with THF, Cu-removing solution (EDTA), water, methanol. Dry.

- Amine Functionalization: React 1.0 g of PGMA-grafted silica with 50 mL ethylenediamine at 80°C for 48h. Filter, wash with water/methanol, dry.

III. Characterization:

- Porosity/Surface Area: N₂ physisorption at 77K (BET, BJH methods).

- Functional Group Density: Elemental Analysis (N%) or acid-base titration.

- Grafting Confirmation: FT-IR (disappearance of epoxide ring at ~910 cm⁻¹, appearance of amine bands).

Protocol 3.2: Batch Adsorption Isotherm for Impurity Uptake

I. Materials:

- Test adsorbent (e.g., from Protocol 3.1).

- Target impurity stock solution (e.g., 1000 ppm NDMA in water).

- HPLC vials, LC-MS system for analysis.

- Phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) or relevant drug formulation matrix.

II. Procedure:

- Prepare impurity solutions in relevant matrix at concentrations (C₀) ranging from 1 to 100 ppm.

- In separate 8 mL vials, add 10.0 mg of adsorbent to 5.0 mL of each solution.

- Seal vials and agitate in a thermostated shaker (25°C, 250 rpm) for 24h to reach equilibrium.

- Filter solutions through 0.22 µm nylon syringe filter.

- Analyze filtrate concentration (Cₑ) via calibrated HPLC-MS.

- Calculate equilibrium adsorption capacity: qₑ (mg/g) = (C₀ - Cₑ) * V / m, where V is volume (L), m is adsorbent mass (g).

- Fit qₑ vs. Cₑ data to Langmuir/Freundlich isotherm models.

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: Trinity Governing Adsorbent Performance

Diagram 2: Bulk vs Surface Polymerization Pathways

Diagram 3: Adsorbent Performance Evaluation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Adsorbent Research

| Item Name | Function/Benefit | Key Consideration for Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Mesoporous Silica (SBA-15, MCM-41) | High-surface-area, tunable pore size substrate for surface polymerization. Provides well-defined porosity. | Pore diameter should accommodate monomer/growing polymer chains. High purity to avoid catalytic side reactions. |

| Functional Silanes (e.g., APTES, MPTMS) | Coupling agents to attach polymerization initiators or functional groups to oxide surfaces. | Anhydrous conditions required for consistent monolayer formation. |

| Controlled Radical Polymerization Kits (ATRP, RAFT) | Enable precise grafting of polymer brushes with controlled thickness and functionality from surfaces. | Choice of initiator/chain transfer agent and metal ligand (for ATRP) critical for control. Requires degassing. |

| High-Purity Crosslinkers (DVB, EGDMA) | Create rigid, porous networks in bulk polymerization. Define mesh size and swelling properties. | Divinylbenzene (DVB) grade (% isomers) significantly impacts final polymer morphology. |

| Pharmaceutical Impurity Standards | Certified reference materials for adsorption studies (e.g., nitrosamines, APIs, genotoxic impurities). | Must match the impurity profile of the actual drug process. Stability in solution is key. |

| Porous Polymer Reference Materials | Commercially available adsorbents (e.g., HP-20 resin, Zorbax) for benchmarking performance. | Provides a baseline for comparing novel synthetic adsorbents. |

| BET Surface Area & Pore Analyzer | Instrument for measuring the trinity's first two components: surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution. | Analysis model (BET, DFT, BJH) must be chosen based on material type (micro/mesoporous). |

Recent Advances in Monomer Design and Polymer Architecture for Selective Adsorption

Application Notes

Selective adsorption materials are critical for applications ranging from pharmaceutical impurity scavenging to environmental remediation. The efficacy of these materials is governed by the synergistic combination of monomer functionality and polymer architectural control. Within the broader thesis context of Bulk vs. Surface Polymerization for Impurity Adsorption Research, recent advances highlight a strategic shift. Bulk polymerization techniques (e.g., precipitation, suspension) are being refined to create high-capacity, monolithic adsorbents with tailored porosity. Conversely, surface polymerization methods (e.g., grafting, thin-film deposition) are engineered to create thin, conformal, and accessible binding layers on inert substrates, minimizing diffusion limitations. The choice between these paradigms depends on the target impurity's concentration, accessibility of binding sites, and the required mechanical stability of the polymer composite.

Table 1: Comparison of Bulk vs. Surface Polymerization Approaches for Selective Adsorption

| Feature | Bulk Polymerization (Precipitation/Suspension) | Surface Polymerization (Grafting-from) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Architecture | Beads, monoliths, macroporous networks | Polymer brushes, thin films on substrates (e.g., silica, membranes) |

| Binding Site Location | Throughout the particle bulk (may be diffusion-limited) | Primarily on the surface (easily accessible) |

| Typical Capacity (Quantitative Example) | High (e.g., 150-300 mg/g for heavy metals) | Lower but highly efficient (e.g., 50-100 mg/g for proteins) |

| Kinetics | Often slower, controlled by pore diffusion | Typically faster, controlled by surface binding |

| Mechanical Stability | High (self-supported) | Dependent on substrate; grafting improves stability |

| Best Suited For | High-concentration impurities, flow-through columns | Low-concentration targets, sensor interfaces, coating complex geometries |

Table 2: Recent Monomer Designs for Targeted Impurities

| Target Impurity Class | Monomer Functionality | Proposed Interaction Mechanism | Reported Adsorption Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical Impurities (Endotoxins) | Cationic groups (e.g., vinylbenzyl trimethylammonium) | Electrostatic binding to lipid A phosphates | >99% removal from solution in batch studies |

| Heavy Metals (Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺) | Amidoxime, carboxylate, dithiocarbamate | Chelation / Ion exchange | Qmax ~220 mg/g for Pb²⁺ (pH 5.0) |

| Organic Dyes (Methylene Blue) | Sulfonic acid, carboxylic acid | Ionic & π-π interactions | Qmax ~400 mg/g for cationic dyes |

| Bisphenol A (Endocrine Disruptor) | Methacrylic acid, β-cyclodextrin derivatives | Hydrogen bonding & host-guest inclusion | >85% removal from wastewater streams |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of Bulk Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) Beads for Selective Dye Adsorption

- Objective: To prepare bulk MIP beads selective for methylene blue (MB) via precipitation polymerization.

- Materials: Methacrylic acid (MAA, functional monomer), ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA, crosslinker), AIBN (initiator), methylene blue (template), acetonitrile (porogen).

- Procedure:

- Dissolve the template (MB, 0.25 mmol) and MAA (1.0 mmol) in 50 mL of acetonitrile in a sealed glass vial. Pre-polymerize for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Add EGDMA (5.0 mmol) and AIBN (20 mg). Purge with nitrogen for 10 minutes to remove oxygen.

- Place the vial in a water bath at 60°C for 24 hours under constant agitation.

- Collect the polymer beads by filtration. Wash sequentially with methanol:acetic acid (9:1 v/v) until no MB is detected in the eluent (UV-Vis), then with pure methanol to neutralize.

- Dry the beads under vacuum at 50°C for 12 hours. Non-imprinted polymer (NIP) controls are synthesized identically but without the MB template.

Protocol 2: Surface-Initiated Polymer Brush Grafting for Protein A Capture

- Objective: To graft poly(glycidyl methacrylate) (PGMA) brushes from silica particles for antibody purification.

- Materials: Silica microparticles, (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES), glycidyl methacrylate (GMA), CuBr/PMDETA (ATRP catalyst system), sodium L-ascorbate.

- Procedure:

- Surface Amination: Silica particles are refluxed with 2% APTES in toluene for 6 hours, then washed and dried to introduce amine initiator sites.

- ATRP Grafting: In a Schlenk flask under N₂, mix GMA (10 mmol), CuBr (0.1 mmol), and PMDETA (0.1 mmol) in 20 mL water/methanol (1:1). Add aminated silica (1 g) and sodium ascorbate (0.2 mmol).

- React at 30°C for 4 hours with gentle stirring.

- Stop the reaction by exposing to air. Wash particles thoroughly with water and methanol.

- Ligand Immobilization: Incubate PGMA-grafted silica with a Protein A solution (1 mg/mL in carbonate buffer, pH 9.5) at 25°C for 24 hours. The epoxy groups of PGMA will covalently bind to amine groups on Protein A.

Visualizations

Title: Polymer Synthesis Path Selection

Title: MIP vs NIP Synthesis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Relevance |

|---|---|

| Functional Monomers (e.g., MAA, 4-VP) | Provide complementary chemical groups (COOH, pyridine) to interact with target impurities via H-bonding, ionic, or van der Waals forces. |

| Cross-linkers (e.g., EGDMA, DVB) | Create the 3D polymer network. Ratio to monomer controls architecture porosity, rigidity, and binding site accessibility. |

| RAFT/ATRP Initiators | Enable controlled radical polymerization for precise architecture engineering (e.g., block copolymers, polymer brushes). |

| Porogens (e.g., Toluene, Cyclohexanol) | Solvents that dictate the morphology in bulk polymerization, creating the pore structure essential for diffusion. |

| Silane Coupling Agents (e.g., APTES) | Modify inorganic substrate surfaces (silica, glass) with initiator groups for subsequent surface polymerization. |

| Template Molecules | The impurity or analog around which an MIP is synthesized, creating specific recognition sites upon removal. |

From Lab to Process: Practical Protocols for Implementing Polymer Adsorption Strategies

This application note provides a detailed protocol for the bulk (or mass) polymerization of adsorbents, framed within a broader research thesis comparing bulk versus surface polymerization for impurity adsorption. Bulk polymerization, characterized by the reaction of pure monomer(s) with an initiator in the absence of a solvent, offers advantages in producing high-purity, dense polymer networks ideal for selective adsorption in downstream pharmaceutical purification. This guide is intended for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to synthesize tailored adsorbents for the removal of specific impurities, such as genotoxic compounds, catalysts, or process-related by-products.

Core Principles & Thesis Context

In impurity adsorption research, the polymerization method dictates critical adsorbent properties. Bulk polymerization creates a homogeneous polymer matrix with consistent cross-linking density, often leading to high capacity but potentially slower diffusion kinetics for large impurities. This contrasts with surface polymerization techniques (e.g., grafting), which modify a pre-existing substrate, creating a heterogeneous structure with potentially faster binding kinetics but lower total capacity. The choice hinges on the target impurity's size, polarity, and concentration.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

The following table details key reagents and their functions for a generalized bulk polymerization protocol for adsorbent synthesis.

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Bulk Polymerization of Adsorbents

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Monomer(s) (e.g., Methacrylic acid, Vinylpyridine, Divinylbenzene) | Primary building block(s) providing the polymeric backbone and functional groups for adsorption. | Choice dictates selectivity (e.g., acidic monomers for basic impurities). |

| Cross-linking Agent (e.g., Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate - EGDMA) | Creates a three-dimensional, insoluble network, controlling porosity and mechanical stability. | Concentration directly affects surface area, pore size, and swelling. |

| Free Radical Initiator (e.g., Azobisisobutyronitrile - AIBN) | Thermally decomposes to generate free radicals, initiating the chain-growth polymerization. | Must be soluble in the monomer mixture; decomposition temperature sets reaction conditions. |

| Porogen (e.g., Toluene, Cyclohexanol) | Inert solvent added to the monomer mixture to create pores during polymerization, later removed. | Critically controls the final adsorbent's surface area and pore morphology. |

| Inhibitor Remover Columns | Used to purify monomers by removing polymerization inhibitors (e.g., hydroquinone) before reaction. | Essential for achieving predictable polymerization kinetics and high molecular weight. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Synthesis of a Methacrylate-Based Bulk Polymer Adsorbent

Objective

To synthesize a high-capacity, macroporous poly(methacrylic acid-co-ethylene glycol dimethacrylate) adsorbent via bulk thermal polymerization for the adsorption of basic pharmaceutical impurities.

Materials Preparation

- Monomers: Methacrylic acid (MAA), Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA).

- Initiator: Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN).

- Porogen: Toluene.

- Equipment: Three-neck round-bottom flask, reflux condenser, nitrogen inlet, heating mantle with stirrer, oil bath, vacuum oven.

Step-by-Step Procedure

1. Monomer Mixture Preparation:

- Pass MAA and EGDMA through basic alumina columns to remove inhibitors.

- In a beaker, combine MAA (20.0 mL, 20 mol%), EGDMA (80.0 mL, 80 mol% cross-linker), and toluene (100 mL, 50% v/v relative to total monomers) as a porogen.

- Add AIBN (0.5 g, 1% w/w relative to total monomers). Stir magnetically until complete dissolution.

2. Polymerization Setup:

- Transfer the homogeneous mixture to a three-neck round-bottom flask.

- Attach a reflux condenser and a nitrogen gas inlet.

- Sparge the mixture with dry nitrogen gas for 20 minutes while stirring to remove dissolved oxygen, a radical inhibitor.

3. Thermal Polymerization:

- Submerge the flask in a pre-heated oil bath at 70°C.

- Maintain under a gentle nitrogen atmosphere with continuous stirring for 24 hours. The mixture will become viscous and eventually form a rigid monolith.

4. Post-Polymerization Processing:

- Carefully break the polymer monolith into small pieces.

- Soxhlet extract the polymer with ethanol for 24 hours to remove the porogen, unreacted monomers, and oligomers.

- Dry the extracted polymer particles in a vacuum oven at 60°C to constant weight.

- Grind the monolith and sieve to obtain a desired particle size fraction (e.g., 100-200 μm).

Characterization & Performance Metrics

Key properties of the synthesized adsorbent should be characterized and compared against adsorbents made via surface polymerization.

Table 2: Typical Characterization Data for Bulk-Polymerized Adsorbent

| Property | Method | Typical Result (Bulk Polymerization) | Comparative Note (vs. Surface Polymerization) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BET Surface Area | N₂ Physisorption | 350 - 600 m²/g | Generally higher than surface-grafted materials. |

| Average Pore Diameter | BJH Analysis | 20 - 50 nm | Tunable via porogen ratio; often broader distribution. |

| Swelling Ratio | Gravimetric in Solvent | 1.5 - 3.0 (in MeOH) | Lower than lightly cross-linked gels but significant. |

| Functional Group Density | Elemental Analysis/Titration | 4 - 8 mmol COOH/g | High, as the entire matrix is functionalized. |

| Adsorption Capacity | Batch binding for model amine | 0.8 - 1.5 mmol/g | High capacity, but kinetics may be pore-diffusion limited. |

| Adsorption Kinetics (t₉₀) | Batch kinetic study | 60 - 120 min | Often slower than thin surface films due to bulk diffusion. |

Experimental Protocol for Batch Adsorption Testing

Objective

To evaluate the adsorption capacity and kinetics of the synthesized bulk polymer for a target basic impurity (e.g., 4-dimethylaminopyridine, DMAP).

Procedure

- Prepare a standard solution of the impurity (e.g., 1.0 mM DMAP in methanol-water mixture).

- Accurately weigh 20.0 mg of the sieved polymer adsorbent into a series of glass vials.

- Add 10.0 mL of the impurity solution to each vial. Run in triplicate.

- Agitate the vials in a thermostated shaker at 25°C for predetermined time intervals (e.g., 5, 15, 30, 60, 120, 240 min).

- At each time point, centrifuge a vial and analyze the supernatant via UV-Vis spectroscopy to determine residual impurity concentration.

- Calculate adsorption capacity (Q, mmol/g) and plot Q vs. time for kinetics, and Q at equilibrium vs. concentration for isotherm modeling (e.g., Langmuir, Freundlich).

Decision Workflow & Synthesis Pathways

Title: Adsorbent Synthesis Method Decision Tree

Bulk Polymerization Reaction Mechanism & Process

Title: Bulk Polymerization to Adsorbent Workflow

Within the broader research comparing bulk versus surface polymerization for impurity adsorption, this guide focuses on surface-specific techniques. Bulk polymerization creates homogeneous resins with adsorptive sites distributed throughout, often leading to slower diffusion kinetics and inaccessible sites for large impurities. Surface polymerization, or grafting, confines the polymer layer to the substrate exterior, creating a high-density, easily accessible interface ideal for selectively capturing impurities like host cell proteins, DNA, or endotoxins in biopharmaceutical streams. This application note details practical protocols for grafting on three key substrates: beads, membranes, and fibers.

Key Substrate Properties and Selection

Table 1: Comparative Substrate Properties for Surface Grafting

| Property | Polymeric Beads (e.g., PS, Agarose) | Polymeric Membranes (e.g., PES, Nylon) | Polymeric Fibers (e.g., PP, PET) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Geometry | Spherical, 10-100 µm diameter | Flat-sheet, hollow fiber; 0.1-1 mm thickness | Diameter: 1-50 µm; woven/nonwoven mats |

| Surface Area (m²/g) | 50-500 (porous) | 5-50 (highly porous) | 1-10 (non-porous fiber) |

| Typical Grafting Target | Interior & exterior pore surfaces | Pore lumen surfaces and top layer | Fiber exterior surface |

| Key Advantage for Adsorption | Very high capacity, packed-bed operation | Low pressure drop, fast convective flow | High mechanical strength, modular formats |

| Common Grafting Method | RAFT, ATRP, "graft-from" | UV-Initiated, Plasma-Activated, "graft-to" | γ-Ray Initiated, Thermal "graft-from" |

Protocols for Surface Polymerization

Protocol 3.1: UV-Initiated Grafting on Polyethersulfone (PES) Membranes

This protocol is optimal for creating a thin, uniform polymer brush layer for high-flow adsorption.

- Substrate Pre-treatment: Cut PES membrane (0.45 µm pore) into 5 cm diameter discs. Soak in 50% ethanol for 30 min, rinse with DI water, and dry under N₂.

- Photo-initiator Coating: Prepare a 5 mM solution of Benzophenone in acetone. Immerse membrane discs for 10 sec, then air-dry in the dark for 5 min.

- Monomer Solution Preparation: In a Schlenk tube, degass 20 mL of an aqueous solution containing 10% (w/v) acrylamide monomer and 1% (w/v) N,N'-methylenebisacrylamide crosslinker by bubbling N₂ for 30 min.

- Grafting Reaction: Place initiator-coated membrane in a quartz reaction chamber. Add degassed monomer solution to submerge the membrane. Illuminate with UV light (365 nm, 100 W) for 2-10 minutes under N₂ atmosphere. Time controls graft density.

- Post-processing: Rinse grafted membrane extensively with 60°C DI water for 24h to remove homopolymer and unreacted monomer. Characterize via ATR-FTIR for C=O stretch at ~1650 cm⁻¹ and gravimetric analysis for grafting yield (%GY = [(Wg - W0)/W0] * 100).

Protocol 3.2: ATRP "Graft-From" on Polystyrene Beads

This controlled radical technique allows precise control over brush length and density on bead surfaces.

- Surface Initiation Site Immobilization: Suspend 1 g of chloromethylated polystyrene beads (100 µm, 1 mmol Cl/g) in 20 mL anhydrous toluene. Add 2 mmol of 2-Bromoisobutyryl bromide and 2 mmol of triethylamine. React at 40°C for 12h under argon.

- Beads Washing: Filter beads and sequentially wash with toluene, methanol, and dichloromethane. Dry under vacuum.

- ATRP Grafting Reaction: In a Schlenk flask, add 0.5 g of initiator-functionalized beads, 10 mL degassed anisole, 10 mmol of glycidyl methacrylate monomer, 0.1 mmol of CuBr catalyst, and 0.2 mmol of bipyridine ligand. Conduct three freeze-pump-thaw cycles.

- Polymerization: React at 60°C for 4-8h with stirring. Terminate by exposing to air and diluting with THF.

- Cleaning: Filter beads and wash with THF, EDTA solution (to remove Cu), and methanol. Soxhlet extract with methanol for 24h. Characterize graft density via elemental analysis (Bromine %).

Protocol 3.3: Plasma-Activated Grafting on Polypropylene Fibers

A versatile method for activating inert fiber surfaces to enable subsequent grafting.

- Plasma Activation: Place nonwoven polypropylene fiber mat in a plasma chamber. Evacuate to 0.2 mbar and introduce argon gas at a flow rate of 20 sccm. Apply RF plasma (40 W) for 60 seconds to generate surface peroxides.

- In-situ Vapor Phase Grafting: Immediately after plasma treatment, introduce acrylic acid vapor into the chamber (from a reservoir heated to 50°C) at 1 mbar for 15 minutes, allowing graft polymerization via peroxide decomposition.

- Post-treatment: Vent chamber and remove fibers. Wash in a 50°C stirred 0.1M NaOH solution for 6h to remove poly(acrylic acid) homopolymer. Rinse with DI water to neutral pH and dry.

- Characterization: Confirm grafting via Toluidine Blue O dye assay (carboxyl group quantification) and SEM for surface morphology changes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Surface Polymerization

| Item | Function & Role in Grafting | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Benzophenone | Type II Photo-initiator. Abstracts H from substrate, creating surface radicals for grafting. | Used in UV-initiation on polymers like PES, Nylon. Light-sensitive. |

| 2-Bromoisobutyryl bromide | ATRP initiator precursor. Functionalizes surfaces with alkyl halide groups to initiate polymerization. | Key for "graft-from" ATRP. Handle under inert, anhydrous conditions. |

| CuBr/Bipyridine Complex | ATRP catalyst system. Controls the equilibrium between active and dormant polymer chains. | Enables controlled polymer growth. Must be degassed. |

| Acrylic Acid Monomer | Common grafting monomer. Imparts hydrophilic, anionic, and reactive carboxyl groups. | Used for ion-exchange or further conjugation. Inhibited (e.g., MEHQ). |

| Glycidyl Methacrylate | Epoxy-containing monomer. Grafted brushes provide reactive epoxides for ligand coupling. | Useful for immobilizing proteins, amines post-grafting. |

| Argon Plasma | Surface activation. Creates radicals, peroxides, or reactive groups on inert polymer surfaces. | Enables grafting on PP, PTFE. Must be used immediately post-activation. |

| Degassed Solvents | Reaction medium for controlled polymerization. Oxygen removal is critical to prevent radical quenching. | Anisole, toluene, water treated by N₂ bubbling or freeze-pump-thaw. |

Table 3: Adsorptive Performance of Surface-Grafted Materials for Impurity Removal

| Substrate & Grafting Method | Target Impurity | Grafted Polymer/Ligand | Key Performance Metric | Reported Value (Range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PES Membrane (UV-Grafting) | Bovine Serum Albumin | Poly(N-vinyl pyrrolidone) | Dynamic Binding Capacity (10% breakthrough) | 18-25 mg/mL membrane volume |

| Polystyrene Beads (ATRP) | Endotoxin (LPS) | Poly(cationic methacrylate) | Removal Efficiency in spiked buffer | >99.5% (from 100 EU/mL) |

| Polypropylene Fibers (Plasma + Graft) | Metal Ions (Cu²⁺) | Poly(acrylic acid) | Maximum Adsorption Capacity (Qmax) | 45-60 mg/g dry fiber |

| Agarose Beads (RAFT Grafting) | Monoclonal Antibody (aggregates) | Poly(ionic liquid) | Aggregate Reduction in harvest feed | 85-95% clearance, >95% monomer recovery |

| Nylon Membrane (Redox-Initiated) | Genomic DNA | Poly(ethyleneimine) | Capacity for DNA (flow-through mode) | 2-4 mg DNA/m² membrane surface |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Title: Decision Workflow for Grafting vs Bulk Polymerization

Title: UV-Initiated Surface Grafting Mechanism

Within the thesis context of Bulk vs Surface Polymerization for Impurity Adsorption Research, selecting the appropriate polymerization strategy is critical. The choice hinges on the physicochemical nature of the target impurity. This framework provides a decision protocol and application notes for matching impurity types to polymerization methods to optimize adsorbent performance in pharmaceutical purification.

Application Notes & Decision Framework

Framework for Matching Impurity to Polymerization Method

The polymerization method dictates the adsorbent's morphology, accessibility of functional groups, and kinetic profile. Bulk polymerization creates highly cross-linked networks with high capacity for small molecules, while surface polymerization (e.g., grafting) creates brush-like layers ideal for accessing large biomolecules.

Table 1: Impurity Characteristics and Recommended Polymerization Method

| Impurity Type | Typical Size (MW/Da) | Key Physicochemical Property | Recommended Polymerization Method | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Molecule APIs/Intermediates | 150 - 500 | High Log P, specific H-bonding | Bulk (Precipitation) | High cross-linking density for molecular imprinting; high capacity. |

| Genotoxic Impurities (GTIs) | 70 - 250 | Electrophilic, often aromatic | Bulk (Suspension) | Creates porous beads with high surface area for covalent or π-π interactions. |

| Endotoxins (LPS) | 10,000 - 1,000,000 | Amphiphilic, aggregate-forming | Surface Grafting | Grafted cationic polymer brushes interact with LPS lipid A without pore blockage. |

| Host Cell Proteins (HCPs) | 10,000 - 100,000+ | Diverse pI, complex 3D structures | Surface-Initiated ATRP | High-density, tunable functional brushes for multimodal or affinity interactions. |

| Viral Particles | 20 - 400 nm | Particulate, surface glycoproteins | Surface Grafting + Cross-linking | Creates a hydrated, functional "soft" layer for size exclusion & binding. |

| Metal Ions (Catalyst residues) | N/A | Charged, small ionic radius | Bulk (Emulsion) | Fine particles/beads with chelating ligands (e.g., iminodiacetate) distributed throughout. |

| Oligonucleotide Fragments | 1,000 - 10,000 | Poly-anionic backbone | Surface-Initiated RAFT | Precise control over graft density/chain length for ion-exchange or hybridization. |

Table 2: Comparative Performance Metrics of Polymerization Methods

| Polymerization Method | Typical Capacity (mg/g) for Model Impurity* | Binding Kinetics (Time to 90% qₑ) | Scalability (1-10) | Suitability for Continuous Flow |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk (Monolithic) | 120-180 (Small Molecule) | Slow (2-4 hrs) | 3 | Low |

| Bulk (Suspension Beads) | 80-150 (GTIs) | Moderate (30-60 min) | 9 | High |

| Surface Grafting (ATRP) | 40-80 (HCP) | Fast (<10 min) | 5 | Medium |

| Surface Grafting (RAFT) | 30-70 (Oligonucleotide) | Fast (<10 min) | 5 | Medium |

*Capacity varies widely with ligand and impurity. Values are indicative ranges.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 2.1: Bulk Suspension Polymerization for GTI Adsorbent

Objective: Synthesize porous, functional polymeric beads for adsorption of aromatic GTIs like N-nitrosamines. Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit" below. Procedure:

- Prepare the organic phase: Dissolve 20 g of styrene, 5 g of divinylbenzene (cross-linker), and 0.5 g of benzoyl peroxide (initiator) in 25 mL of toluene (porogen).

- Prepare the aqueous phase: Dissolve 1.0 g of poly(vinyl alcohol) stabilizer in 200 mL of deionized water in a 500 mL round-bottom flask equipped with a condenser, overhead stirrer, and nitrogen inlet.

- Purge both phases with nitrogen for 15 minutes to remove oxygen.

- Add the organic phase to the aqueous phase with vigorous stirring (400-500 rpm) to form a stable droplet suspension. Maintain a nitrogen atmosphere.

- Heat the reaction mixture to 70°C and polymerize for 18 hours with continuous stirring.

- Cool to room temperature. Filter the beads and wash extensively with water, ethanol, and acetone.

- Soxhlet extract the beads with acetone for 24 hours to remove porogen and unreacted monomers.

- Dry under vacuum at 60°C for 12 hours. Characterize by BET (surface area), SEM (morphology), and FTIR (functionality).

Protocol 2.2: Surface-Initiated ATRP for HCP Adsorbent

Objective: Grow a dense poly(glycidyl methacrylate) brush from silica substrate for subsequent functionalization with affinity ligands. Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit" below. Procedure:

- Substrate Silanization: Activate 10 g of silica particles (100 µm, 300 Å pores) by heating at 120°C under vacuum for 2 hours. Cool under nitrogen. In anhydrous toluene, react with (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES, 2% v/v) under reflux for 12 hours. Wash with toluene and dry.

- Initiator Immobilization: React APTES-silica with α-bromoisobutyryl bromide (BiBB, 2 equiv.) in anhydrous THF with triethylamine as acid scavenger, at 0°C for 1 hour, then RT for 12 hours. Wash with THF and dry. This yields the ATRP initiator-functionalized silica (Si-Br).

- Surface-Initiated ATRP: In a Schlenk flask, dissolve glycidyl methacrylate (GMA, 10 mL) in 50 mL of anisole. Add the ligand complexes: Cu(I)Br (20 mg) and N,N,N',N'',N''-pentamethyldiethylenetriamine (PMDETA, 40 µL). Degass by three freeze-pump-thaw cycles.

- Under nitrogen, quickly add 2.0 g of Si-Br to the monomer/catalyst solution. Seal and place in an oil bath at 60°C for 2 hours with gentle agitation.

- Terminate the reaction by exposing to air and diluting with THF. Filter the particles (now Si-PGMA).

- Wash sequentially with THF, water, and methanol. Dry under vacuum. Characterize graft density by TGA (weight loss %).

- Functionalization: React the epoxide groups of the PGMA brush with a chosen ligand (e.g., 1,2-ethylenediamine for cation exchange, or Cibacron Blue for affinity) in appropriate buffer at 50°C for 24 hours.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Polymerization & Adsorption Studies

| Item | Function/Explanation | Example in Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Divinylbenzene (DVB) | High-efficiency cross-linker in bulk polymerization. Creates rigid, porous 3D network. | Protocol 2.1: Creates porous bead structure. |

| Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) | Thermally decomposing radical initiator for bulk/solution polymerizations. | Alternative to BPO in Protocol 2.1. |

| (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) | Coupling agent. Provides amino groups to anchor initiators or polymers onto oxide surfaces. | Protocol 2.2: Step 1, links silica to ATRP initiator. |

| α-Bromoisobutyryl bromide (BiBB) | ATRP initiator precursor. Reacts with surface amines to install alkyl halide initiator sites. | Protocol 2.2: Step 2, creates the surface-bound ATRP initiator. |

| Cu(I)Br / Ligand Complex | ATRP catalyst system. Controls the equilibrium between active and dormant species for living polymerization. | Protocol 2.2: Step 3, enables controlled brush growth. |

| Glycidyl methacrylate (GMA) | Versatile monomer with an epoxide ring. The ring allows post-polymerization modification with various ligands. | Protocol 2.2: Primary brush-forming monomer. |

| Dynamic Binding Capacity (DBC) Test Column | Small-scale chromatography column (e.g., 0.5 cm ID) to measure adsorbent capacity under flow conditions. | Used in performance validation post-Protocols 2.1 & 2.2. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) MALS | Analyzes polymer brush molecular weight and dispersity (Đ) cleaved from the surface. | Characterization post-Protocol 2.2. |

Visualizations

Decision Framework for Polymerization Method Selection

ATRP Grafting Protocol Workflow

Within the context of a broader thesis comparing bulk versus surface polymerization strategies for designing adsorbents for impurity removal, the integration of these materials into downstream processing (DSP) configurations is a critical research frontier. The choice of operational configuration—Batch, Packed-Bed, or Membrane Adsorber—profoundly impacts binding capacity, throughput, impurity clearance, and scalability. This application note provides detailed protocols and comparative analysis for evaluating novel polymeric adsorbents synthesized via bulk or surface methods across these three primary DSP configurations, focusing on applications like host cell protein (HCP) and DNA clearance in monoclonal antibody (mAb) purification.

Comparative Analysis of Configurations

The performance of adsorbents is highly dependent on their integration format. The table below summarizes key operational and performance parameters.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Adsorber Configurations

| Parameter | Batch Adsorption | Packed-Bed Chromatography | Membrane Adsorber |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contact Mode | Stirred-tank, suspension | Fixed-bed, percolation | Convective flow-through pores |

| Binding Kinetics | Diffusion-limited (slow) | Diffusion-limited (pore diffusion) | Convection-dominated (fast) |

| Typical Residence Time | 30 - 120 minutes | 2 - 6 minutes | 0.1 - 0.5 minutes |

| Pressure Drop | Very Low | High (scale-dependent) | Low to Moderate |

| Dynamic Binding Capacity (DBC10%) | Not applicable (static) | 25 - 75 g/L for Protein A; 10-50 g/L for ion-exchange | 1 - 5 g/mL (volumetric) |

| Scalability | Simple in principle, but large volumes | Challenging (bed uniformity, pressure) | Straightforward (membrane stacking) |

| Best Suited for | Pre-treatment, nucleic acid removal, endpoint polishing | High-resolution capture and polishing | High-throughput flow-through polishing, virus removal |

| Compatibility with Bulk Polymer | High (beads, particles) | High (beads must withstand pressure) | Low (requires coating on pre-formed membrane) |

| Compatibility with Surface Polymer | Medium (coated particles) | Medium (grafted beads) | High (ideal for grafting on membranes) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Batch Adsorption for HCP Reduction

Objective: Evaluate static binding capacity and kinetics of bulk-polymerized adsorbent beads for HCP removal from clarified harvest. Materials:

- Test adsorbent: Bulk-polymerized polymeric beads (e.g., 50 µm diameter).

- Solution: Clarified CHO cell harvest containing mAb (~5 g/L) and HCPs (~100,000 ppm).

- Equipment: Orbital shaker, centrifuge, HPLC system, HCP ELISA kit.

Procedure:

- Equilibration: Suspend 0.1 g of adsorbent beads in 10 mL of equilibration buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5). Shake for 15 minutes. Centrifuge and discard supernatant.

- Adsorption: Add 10 mL of clarified harvest to the equilibrated beads. Shake at 150 rpm at room temperature.

- Sampling: Withdraw 1 mL samples at t = 5, 15, 30, 60, and 120 minutes. Immediately centrifuge to separate beads.

- Analysis: Analyze supernatant via HCP ELISA to determine residual HCP concentration. Calculate binding capacity (mg HCP / g adsorbent) over time.

- Regeneration: Wash beads with 1 M NaCl, then 0.1 M NaOH, and re-equilibrate for reuse studies.

Protocol 2: Packed-Bed Chromatography for Aggregate Removal

Objective: Determine the dynamic binding capacity (DBC) of surface-polymerized grafted agarose resin for mAb aggregate removal. Materials:

- Column: Tricorn 5/50 (5 mm diameter).

- Adsorbent: Agarose resin functionalized with surface-polymerized cationic grafts.

- Sample: Partially purified mAb solution spiked with 10% aggregates.

- Equipment: ÄKTA pure or similar FPLC system, UV detector, SEC-HPLC.

Procedure:

- Packing: Prepare a 50% slurry of the resin. Pack into the column at 300 cm/hr using packing buffer. Determine bed height (target ~5 mL column volume).

- Equilibration: Equilibrate with 5 CVs of 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.0.

- Loading: Load the mAb sample at 10 g/L resin loading, at a linear flow velocity of 150 cm/hr. Collect flow-through.

- Wash & Elution: Wash with 5 CVs of equilibration buffer. Elute bound aggregates using a linear gradient from 0 to 1 M NaCl over 20 CVs.

- Analysis: Analyze load, flow-through, and elution fractions by SEC-HPLC to quantify aggregate removal. Calculate DBC at 10% breakthrough (DBC10%).

Protocol 3: Membrane Adsorber for Flow-Through DNA Clearance

Objective: Assess the performance of a membrane adsorber functionalized with surface-polymerized anion-exchange ligands for DNA clearance in flow-through mode. Materials:

- Membrane: Commercial 1 mL (0.5 mL/cm²) anion-exchange capsule adsorber (e.g., Mustang Q).

- In-situ modification solution for surface grafting (e.g., monomer + initiator).

- Sample: Purified mAb in 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, spiked with 1000 ppm host cell DNA.

- Equipment: Peristaltic pump or syringe pump, UV monitor, fraction collector, qPCR system.

Procedure:

- Surface Modification (if applicable): Flush virgin membrane with grafting solution. Initiate polymerization via UV or thermal treatment. Wash extensively.

- System Setup: Install the membrane capsule in a flow path. Avoid introducing air bubbles.

- Equilibration: Equilibrate with 10 CVs of 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0.

- Loading & Flow-Through: Load the DNA-spiked mAb solution at a challenge of 5 kg mAb per L membrane volume, using a residence time of 0.2 minutes (e.g., 5 mL/min for 1 mL device). Collect the entire flow-through pool.

- Strip & Clean: Strip bound DNA with 5 CVs of 1 M NaCl, followed by 0.5 M NaOH.

- Analysis: Quantify DNA in load and product pool using qPCR. Calculate log reduction value (LRV).

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Context |

|---|---|

| Bulk-Polymerized Beads | Macroporous polymer particles (e.g., poly(styrene-divinylbenzene)) for batch or packed-bed use, offering high surface area from internal pores. |

| Surface-Grafting Monomer Solution | Contains monomers (e.g., [2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl]trimethylammonium chloride) and initiators to create polymer brushes on existing bead/membrane surfaces. |

| Clarified Cell Harvest | Complex feedstock containing the product, HCPs, DNA, and other impurities; used for realistic binding studies. |

| HCP ELISA Kit | Quantifies host cell protein concentrations pre- and post-adsorption to determine clearance efficiency. |

| qPCR Reagents | For ultra-sensitive detection and quantification of trace levels of host cell DNA in process streams. |

| SEC-HPLC Column | Size-exclusion chromatography to separate and quantify mAb monomers, aggregates, and fragments. |

| ÄKTA or FPLC System | Provides precise control over flow rates, gradients, and detection for packed-bed experiments. |

| Anion-Exchange Membrane Capsule | Pre-formed, scalable membrane device ideal for testing surface-modified convective adsorbers. |

| Regeneration Buffers (NaOH, NaCl) | Critical for cleaning and sanitizing adsorbents to restore capacity and ensure longevity. |

Process Configuration Decision Workflow

Title: DSP Configuration Selection Workflow

Adsorbent Integration & Performance Pathway

Title: From Polymer Synthesis to DSP Performance

The optimization of downstream purification is critical in biopharmaceutical development. This case study is framed within a broader research thesis comparing bulk polymer synthesis versus surface-initiated polymerization for creating advanced adsorbents. The core hypothesis is that while bulk polymerization yields materials with high capacity due to a porous network, surface-initiated polymerization on pre-formed supports (e.g., beads) allows for precise, thin, and accessible polymer grafts optimized for capturing specific, challenging impurities like Protein A leachate and silicone oil emulsion droplets.

Application Notes: Custom Polymer Functionality

Target Impurities and Binding Mechanisms

Protein A Leachate: Fragments of immobilized Protein A ligand that leach from chromatography resins during monoclonal antibody (mAb) purification. Custom polymers are designed with mixed-mode ligands (e.g., incorporating hydrophobic, cation-exchange, or metal-chelating groups) that selectively bind the leached Protein A (≈5-50 kDa) over the much larger mAb.

Silicone Oil: Used as a lubricant in pre-filled syringes and process vessels, it can form sub-micron droplets (0.1-10 µm) that co-purify with biologics, posing immunogenicity risks. Hydrophobically tuned polymers with optimized surface energy and pore morphology are designed to capture these droplets via hydrophobic interactions and size exclusion.

Comparative Performance Data

Table 1: Performance of Bulk vs. Surface Polymer Adsorbents for Impurity Removal

| Parameter | Bulk Polymer (Polymer Monolith) | Surface-Grafted Polymer (on Agarose Bead) |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Morphology | Macroporous, continuous network | Thin film (< 100 nm) on spherical support |

| Primary Target | Silicone oil droplets | Protein A leachate |

| Dynamic Binding Capacity | 12 mg silicone oil / mL adsorbent | 8 mg Protein A / mL adsorbent |

| Removal Efficiency | >95% (from 500 ppm to <25 ppm) | >99% (from 1000 ng/mL to <10 ng/mL) |

| Flow Rate Compatibility | Moderate (high pressure drop) | High (low pressure drop) |

| Regeneration Cycles | 5 cycles before 15% capacity loss | 20 cycles before 10% capacity loss |

| Thesis Advantage | High capacity for particulate impurities | Superior selectivity & kinetics for soluble impurities |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Synthesis of Bulk Polymer Monolith for Silicone Oil Capture

Objective: Synthesize a hydrophobic copolymer monolith via bulk free-radical polymerization. Materials:

- Monomer Mix: Butyl methacrylate (BuMA, 24% v/v), ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA, 16% v/v) as crosslinker.

- Porogens: Cyclohexanol (48% v/v), 1-dodecanol (12% v/v).

- Initiator: 2,2'-Azobis(2-methylpropionitrile) (AIBN, 1% w/w wrt monomers). Procedure:

- Weigh and mix porogens in a 20 mL vial.

- Add monomers and AIBN to the porogen mixture. Vortex until AIBN dissolves.

- Degas the solution by sparging with nitrogen for 10 minutes.

- Transfer the solution to a suitable mold (e.g., a 5 mL polypropylene syringe barrel sealed at the bottom).

- Incubate the mold in a water bath at 60°C for 20 hours to complete polymerization.

- Wash the resulting monolith exhaustively with ethanol and then PBS to remove porogens and unreacted components.

- Characterize pore size distribution by mercury intrusion porosimetry (expected range: 1-10 µm).

Protocol: Surface-Initiated ATRP for Protein A Leachate Adsorbent

Objective: Graft a mixed-mode polymer brush (cationic/hydrophobic) onto agarose beads. Materials:

- Support: NHS-activated Sepharose 4 Fast Flow beads.

- Initiator: 2-Bromo-2-methylpropionic acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester.

- Monomer Solution: 2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate (DMAEMA, 80 mol%), hydroxypropyl methacrylate (HPMA, 20 mol%) in 50:50 water/methanol.

- Catalyst: Cu(I)Br / Tris(2-pyridylmethyl)amine (TPMA) complex. Procedure:

- Initiator Immobilization: Suspend 10 mL NHS-agarose beads in 20 mL ice-cold 1 mM HCl. Add 5 mL of a 50 mM initiator solution in anhydrous DMF. React on a rotary mixer for 2 hours at 4°C. Block excess NHS groups with 1 M ethanolamine. Wash with water and methanol.

- Deoxygenation: Transfer initiator-functionalized beads to a Schlenk flask. Add monomer solution and catalyst (CuBr:TPMA at 1:1.1 molar ratio). Seal and perform three freeze-pump-thaw cycles to remove oxygen.

- Polymerization: Backfill the flask with nitrogen and place it in an oil bath at 30°C. Allow polymerization to proceed under gentle agitation for 4 hours.

- Termination & Cleanup: Expose the reaction mixture to air to terminate ATRP. Filter the beads and wash sequentially with EDTA solution, methanol, and 0.1 M acetic acid. Store in 20% ethanol.

Protocol: Impurity Removal and Quantification

Protein A Leachate Assay:

- Pack a 1 mL column with surface-grafted polymer beads.

- Load 50 column volumes (CV) of a clarified mAb harvest spiked with 1000 ng/mL recombinant Protein A at a linear flow rate of 150 cm/hr.

- Collect the flow-through and measure Protein A concentration via a validated ELISA.

- Regenerate the column with 5 CV of 0.1 M glycine-HCl, pH 2.5.

Silicone Oil Emulsion Capture Test:

- Prepare a standardized silicone oil emulsion (500 ppm in PBS) by high-pressure homogenization.

- Incubate 1 mL of bulk polymer monolith (crushed to particles) with 10 mL of the emulsion in an end-over-end mixer for 1 hour.

- Filter the suspension through a 0.45 µm filter (to capture polymer particles).

- Analyze the filtrate for silicone oil concentration using infrared spectroscopy or nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA).

Diagrams

Title: Thesis Framework Linking Polymer Synthesis to Case Studies

Title: Bulk Polymer Synthesis & Silicone Oil Testing Workflow

Title: Surface Polymer Grafting & Leachate Assay Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Materials for Custom Polymer Adsorbent Research

| Item | Function & Relevance in Research |

|---|---|

| Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA) | Crosslinking agent in bulk polymerization. Controls mesh size and mechanical stability of monoliths. |

| 2-Bromo-2-methylpropionic acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester | ATRP initiator functionalized for covalent immobilization on amine-reactive supports (e.g., NHS-agarose). |

| Cu(I)Br / TPMA Catalyst System | Robust catalyst for aqueous ATRP. Enables controlled grafting from surfaces with minimal termination. |

| NHS-activated Sepharose 4 Fast Flow | Model spherical support for surface polymerization. Provides defined geometry and high flow for chromatography. |

| Butyl methacrylate (BuMA) | Hydrophobic monomer for synthesizing polymers targeting silicone oil via hydrophobic interactions. |

| 2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate (DMAEMA) | Cationic monomer providing ion-exchange functionality for capturing negatively charged Protein A leachate. |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer (NTA) | Instrument for quantifying and sizing residual silicone oil droplets in the sub-micron range post-adsorption. |

| Protein A ELISA Kit | High-sensitivity analytical method for quantifying leachate levels in process streams before and after adsorption. |

Solving Real-World Challenges: Optimizing Polymer Adsorbent Performance and Stability

Application Notes: Bulk vs. Surface Polymerization for Impurity Adsorption

Within the broader thesis investigating bulk versus surface polymerization strategies for selective impurity adsorption in biopharmaceuticals, three critical operational pitfalls consistently compromise performance: non-specific binding (NSB), dynamic capacity loss, and polymer degradation. Bulk polymerization, forming three-dimensional monoliths or beads, offers high volumetric capacity but risks poor mass transfer and inaccessible binding sites. Surface polymerization, grafting thin functional layers onto solid supports, provides superior accessibility and kinetics but often at the cost of total capacity and long-term stability.

Recent studies (2023-2024) highlight that NSB of product molecules to adsorption media can exceed 5% in poorly optimized systems, directly impacting yield. Capacity loss over 10-15 cycles frequently falls between 20-40%, linked to polymer degradation or fouling. The choice of polymerization method dictates the primary degradation pathway: bulk polymers suffer more from hydrolytic or mechanical cleavage, while surface-grafted layers are prone to oxidative or shear-induced loss.

Key Quantitative Findings

Table 1: Comparative Performance and Pitfalls of Polymerization Methods

| Parameter | Bulk Polymerization | Surface Polymerization | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Static Binding Capacity (Target Impurity) | 45-120 mg/g | 15-50 mg/g | Batch Adsorption Isotherm (Langmuir) |

| Common NSB Level (Product) | 2-8% | 1-5% | Radiolabeled Tracer / HPLC Assay |

| Avg. Capacity Loss after 20 Cycles | 25-40% | 15-30% | Cyclic Adsorption-Desorption |

| Primary Degradation Mode | Hydrolytic cleavage, cracking | Oxidative scission, shear erosion | FTIR, SEM, Leachable Analysis |

| Ligand Density | High (but may be inaccessible) | Moderate to High (accessible) | Elemental Analysis, Titration |

| Impact of Pore Diffusion Limitation | Severe | Minimal | Uptake Kinetics Modeling |

Table 2: Mitigation Strategies and Their Efficacy

| Pitfall | Mitigation Strategy | Typical Efficacy Improvement | Key Trade-off |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Specific Binding | Incorporation of hydrophilic co-monomers (e.g., PEG-DA) | 60-80% reduction in NSB | May reduce total capacity by 10-20% |

| Capacity Loss | Post-polymerization cross-linking (e.g., with glutaraldehyde) | Extends cycle life by ~50% | Can increase NSB |

| Polymer Degradation (Hydrolytic) | Use of hydrolysis-resistant monomers (e.g., acrylamides vs. acrylates) | Degradation rate reduced by factor of 3-5 | Cost, polymerization kinetics |

| Fouling-Induced Loss | Periodic NaOH/CIP cleaning | Restores >95% of lost capacity | Risk of degrading base matrix |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Non-Specific Binding in Batch Adsorption

Objective: Measure the percentage of the target therapeutic protein (e.g., a monoclonal antibody) that binds non-specifically to bulk or surface-polymerized adsorbents. Materials: Polymer adsorbent, PBS (pH 7.4), target mAb solution (1 mg/mL), irrelevant protein (e.g., BSA, 1 mg/mL), low-binding microcentrifuge tubes, HPLC system with SEC column. Procedure:

- Weigh 10 mg of dry polymer into a low-binding tube (n=3).

- Add 1 mL of PBS, equilibrate on rotator for 30 min. Centrifuge (5000g, 2 min), discard supernatant.

- Add 1 mL of mAb solution. Incubate on rotator for 60 min at 25°C.

- Centrifuge (5000g, 5 min). Carefully collect supernatant.

- Quantify unbound mAb in supernatant via HPLC-SEC, using a pre-established calibration curve.

- Calculate NSB: % NSB = [(Initial mAb - Unbound mAb) / Initial mAb] x 100%.

- Repeat steps 1-6 using an irrelevant protein (BSA) to assess general protein adsorption.

Protocol 2: Accelerated Aging for Degradation and Capacity Loss

Objective: Simulate long-term use and identify degradation pathways. Materials: Polymer adsorbent, relevant buffer (e.g., acetate, pH 5.0), oxidative challenge (0.1% H₂O₂), shaking incubator. Procedure: