Bridging the Scale Gap: How AI Revolutionizes Polymer Structure Prediction from Molecules to Materials

This article provides a comprehensive overview of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) methodologies for predicting polymer structures across multiple scales, from monomer sequences to bulk material properties.

Bridging the Scale Gap: How AI Revolutionizes Polymer Structure Prediction from Molecules to Materials

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) methodologies for predicting polymer structures across multiple scales, from monomer sequences to bulk material properties. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores foundational concepts in polymer informatics, details cutting-edge AI techniques like Graph Neural Networks and generative models for structure prediction, addresses critical challenges in data scarcity and model generalization, and validates AI's performance against traditional simulation methods. The review synthesizes how these computational advances are accelerating the rational design of functional polymers for biomedical applications, drug delivery systems, and advanced therapeutics.

Decoding Polymer Complexity: Foundational AI Concepts for Multi-Scale Informatics

The central challenge in polymer science is the prediction of macroscopic material properties—mechanical strength, elasticity, permeability, degradation—from the chemical structure of its constituent monomers and the processing conditions. This multi-scale problem, spanning from Ångströms (chemical bonds) to meters (finished products), has traditionally been addressed through separate, siloed theoretical and experimental frameworks. The emergent thesis of this whitepaper is that artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) provide a transformative framework for integrating data across these scales, enabling predictive models that directly link quantum-chemical calculations to continuum-level properties. This guide details the core technical challenges at each scale and presents experimental and computational protocols necessary to generate the high-fidelity data required to train and validate such AI models.

The Multi-Scale Hierarchy: Definitions and Key Phenomena

The behavior of polymers is governed by interactions and structures emerging at discrete, interconnected scales.

Table 1: The Polymer Multi-Scale Hierarchy and Governing Principles

| Scale | Length/Time Scale | Key Descriptors | Dominant Phenomena | Target Properties Influenced |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum/Atomistic | 0.1–1 nm / fs–ps | Electronic structure, partial charges, torsional potentials | Chemical bonding, rotational isomerism, initiation kinetics | Chemical reactivity, thermal stability, degradation pathways |

| Molecular | 1–10 nm / ns–µs | Chain conformation, persistence length, radius of gyration | Chain folding, solvent-polymer interactions, tacticity | Solubility, glass transition temperature (Tg), chain mobility |

| Mesoscopic | 10 nm–1 µm / µs–ms | Entanglements, crystallinity, phase separation (in blends) | Chain entanglement, nucleation & growth, microphase separation (in block copolymers) | Viscosity (melt/rheology), toughness, optical clarity |

| Macroscopic | >1 µm / ms–s | Morphology, filler dispersion, void content, overall dimensions | Fracture propagation, yield stress, diffusion, erosion | Tensile strength, modulus, permeability, degradation rate |

Experimental Protocols for Cross-Scale Data Generation

Generating a cohesive dataset for AI training requires standardized protocols that probe specific scales while being mindful of their impact on adjacent scales.

Protocol: Atomistic-Scale Characterization (Monomer Reactivity)

- Objective: To determine kinetic parameters for polymerization initiation and propagation.

- Materials: High-purity monomer (e.g., Methyl methacrylate), initiator (e.g., AIBN), deuterated solvent for NMR (e.g., CDCl₃).

- Method:

- Prepare a series of reaction mixtures in sealed NMR tubes under inert atmosphere with constant initiator concentration and varying monomer concentrations.

- Use in situ ¹H NMR spectroscopy at a controlled temperature (e.g., 60°C for AIBN) to monitor the decay of the vinyl proton signal (δ ~5.5-6.5 ppm) over time.

- Fit the time-dependent monomer conversion data to integrated rate equations (e.g., for free-radical polymerization) to extract the propagation rate constant, kₚ.

- AI Data Output: Time-series data of conversion vs. time, yielding precise kₚ and initiator efficiency f. This serves as ground-truth data for validating quantum chemistry-based transition state calculations.

Protocol: Mesoscale Structure Determination (Morphology in Block Copolymers)

- Objective: To characterize the nanoscale phase-separated morphology of a diblock copolymer.

- Materials: Symmetric polystyrene-block-poly(methyl methacrylate) (PS-b-PMMA), annealed film on silicon wafer.

- Method:

- Sample Preparation: Spin-coat a 1% wt solution of PS-b-PMMA in toluene onto a silicon substrate. Anneal under vacuum at 180°C (>Tg of both blocks) for 24 hours to achieve thermodynamic equilibrium morphology.

- Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS): Conduct SAXS measurement using a synchrotron or laboratory source. The sample-to-detector distance and X-ray wavelength are calibrated for a q-range of 0.05–2 nm⁻¹.

- Analysis: Fit the 1D azimuthally averaged scattering intensity I(q) vs. q. A primary scattering peak at q* followed by higher-order peaks at ratios of 1:√3:2... indicates a hexagonally packed cylindrical morphology; peaks at 1:√2:√3... indicate lamellae.

- AI Data Output: The scattering pattern I(q) and the identified morphology (e.g., cylinder diameter, inter-domain spacing). This data links molecular parameters (Flory-Huggins χ parameter, block length N) to mesoscale structure.

Protocol: Macroscopic Property Measurement (Tensile Behavior)

- Objective: To measure the stress-strain response of a semi-crystalline polymer film.

- Materials: Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) film, dog-bone shaped (ASTM D638 Type V), thickness 0.2 mm.

- Method:

- Condition samples at 23°C and 50% relative humidity for 48 hours.

- Perform uniaxial tensile testing using a universal testing machine equipped with a 1 kN load cell and extensometer.

- Apply a constant crosshead displacement rate of 10 mm/min until fracture.

- Record engineering stress vs. strain. Calculate Young's modulus from the initial linear slope (0.1–0.5% strain), yield stress, and ultimate tensile strength.

- AI Data Output: Full stress-strain curve. Key quantitative metrics: Young's Modulus (E), Yield Stress (σᵧ), Strain at Break (ε_b). This is the target property for final AI prediction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Multi-Scale Polymer Characterization

| Item | Function/Application | Example(s) | Critical Consideration for AI Data Fidelity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chain-Transfer Agent (CTA) | Controls polymer molecular weight and end-group functionality during polymerization. | Dodecyl mercaptan, Cyanomethyl dodecyl trithiocarbonate (RAFT agent) | Purity and precise concentration are vital for predicting Mn and dispersity (Đ). |

| Deuterated Solvents | Allows for NMR analysis of reaction kinetics and polymer structure without interfering proton signals. | CDCl₃, DMSO-d6, D₂O | Must be anhydrous for moisture-sensitive polymerizations (e.g., anionic, ROP). |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Standards | Calibrates SEC systems to determine absolute molecular weight (Mn, Mw) and dispersity (Đ). | Narrow dispersity polystyrene, poly(methyl methacrylate) | Requires matching polymer chemistry and solvent (THF, DMF, etc.) for accurate results. |

| SAXS Calibration Standard | Calibrates the q-scale of a SAXS instrument for accurate nanoscale dimension measurement. | Silver behenate, glassy carbon | Regular calibration is essential for accurate mesoscale domain spacing data. |

| Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) Calibration Kit | Calibrates the force and displacement sensors of a DMA/Rheometer for viscoelastic property measurement. | Standard metal springs, reference polymer sheets | Ensures accuracy in measuring storage/loss moduli (G', G") across temperature sweeps. |

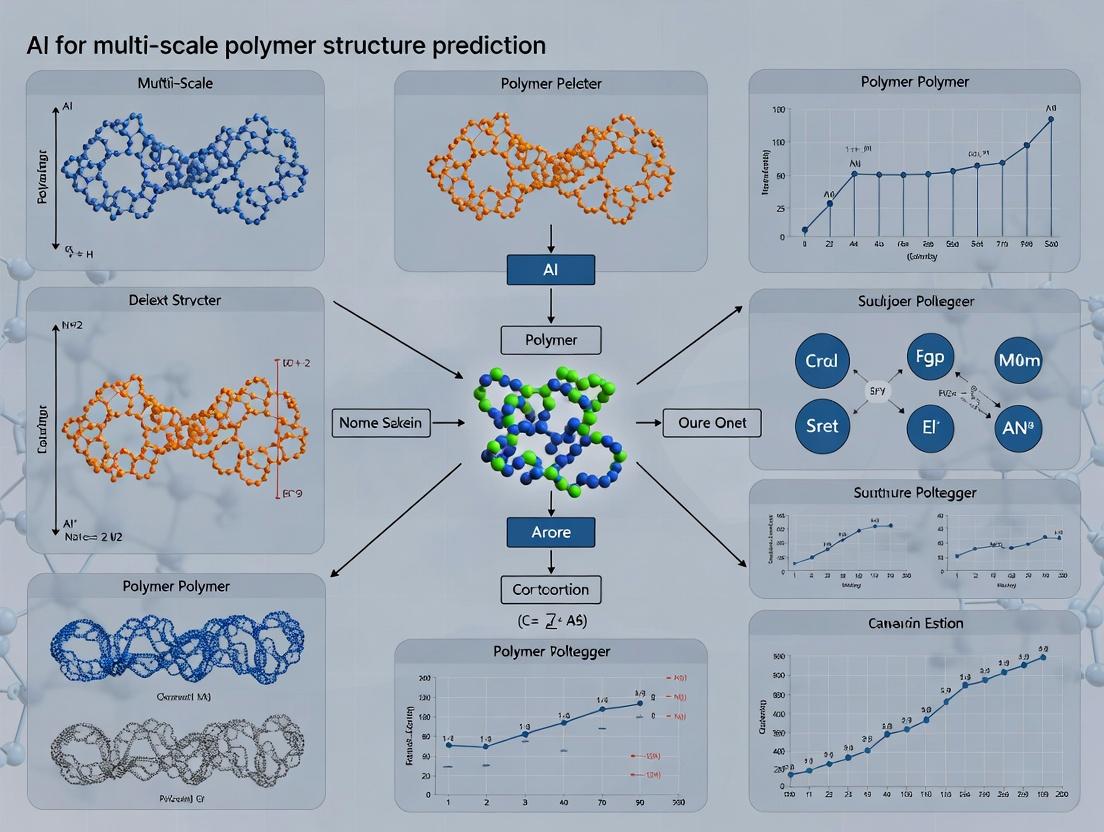

Visualizing the Multi-Scale Integration Workflow for AI

Diagram Title: AI-Driven Multi-Scale Polymer Modeling and Data Integration

A Practical AI-Ready Data Table: From Synthesis to Properties

Table 3: Exemplar Dataset for Poly(L-lactide) (PLLA) AI Model Training

| Sample ID | [M]/[I] | Catalyst | Temp (°C) | Time (h) | Mn (kDa) [SEC] | Đ [SEC] | %Cryst. [DSC] | Tg (°C) [DMA] | Tm (°C) [DSC] | Young's Modulus (GPa) [Tensile] | Ultimate Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLLA-1 | 500 | Sn(Oct)₂ | 130 | 24 | 42.1 | 1.15 | 35 | 58.2 | 172.5 | 2.1 | 55 |

| PLLA-2 | 1000 | Sn(Oct)₂ | 130 | 48 | 85.3 | 1.22 | 40 | 59.1 | 173.0 | 2.4 | 62 |

| PLLA-3 | 500 | TBD | 25 | 2 | 38.5 | 1.08 | 10 | 55.0 | 165.0 | 1.5 | 40 |

| PLLA-4 | 1000 | TBD | 25 | 4 | 78.8 | 1.12 | 15 | 56.0 | 166.5 | 1.8 | 48 |

Abbreviations: [M]/[I]: Monomer to Initiator ratio; Sn(Oct)₂: Tin(II) 2-ethylhexanoate; TBD: 1,5,7-Triazabicyclo[4.4.0]dec-5-ene; SEC: Size Exclusion Chromatography; Đ: Dispersity (Mw/Mn); DSC: Differential Scanning Calorimetry; DMA: Dynamic Mechanical Analysis.

The multi-scale challenge in polymer science is fundamentally a data integration and prediction problem. The experimental protocols and standardized data generation outlined here provide the essential feedstock for AI models. The next frontier involves the development of hybrid physics-informed AI architectures that can seamlessly traverse scales—using quantum-derived parameters to predict entanglement densities, which in turn predict bulk modulus, while simultaneously being constrained and validated by real-world experimental data at each level. This approach will ultimately enable the in silico design of polymers with tailor-made macroscopic properties for specific applications in drug delivery, advanced manufacturing, and sustainable materials.

Polymer informatics emerges as a transformative discipline at the intersection of polymer science, materials engineering, and artificial intelligence. This whitepaper delineates the core principles of polymer informatics, emphasizing its foundational role within a broader thesis on AI-driven multi-scale polymer structure prediction. The integration of machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) techniques is enabling the acceleration of polymer discovery, property prediction, and the rational design of advanced materials, directly impacting fields such as drug delivery systems and biomedical device development.

Traditional polymer development relies on iterative synthesis and testing, a process that is often slow, resource-intensive, and limited by human intuition. Polymer informatics seeks to overcome these bottlenecks by treating polymers as data-driven entities. It involves the systematic collection, curation, and analysis of polymer data—spanning chemical structures, processing conditions, and functional properties—to extract knowledge and build predictive models. Within the context of multi-scale structure prediction, the goal is to establish reliable mappings from monomeric sequences and processing parameters to atomistic, mesoscopic, and bulk properties using AI/ML.

Core Components of Polymer Informatics

Data Curation and Representation

A critical first step is the encoding of polymer structures into machine-readable formats or numerical descriptors.

Key Polymer Representations:

- SMILES/String-based: Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System for monomers and repeating units.

- Fingerprints: Molecular fingerprints (e.g., Morgan fingerprints) capturing substructural features.

- Graph Representations: Polymers represented as graphs where nodes are atoms and edges are bonds, suitable for Graph Neural Networks (GNNs).

- Sequential Descriptors: Treating copolymers as sequences of monomer units, akin to biological sequences.

AI/ML Methodologies in Polymer Informatics

Different ML paradigms address various prediction tasks across the polymer design pipeline.

Table 1: Core AI/ML Models in Polymer Informatics

| Model Category | Typical Algorithms | Primary Application in Polymers | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning | Random Forest, Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Support Vector Regression (SVR) | Predicting continuous properties (e.g., glass transition Tg, tensile strength) from descriptors. | High interpretability, effective on smaller datasets. |

| Deep Learning (DL) | Fully Connected Neural Networks (FCNN), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) | Learning complex non-linear structure-property relationships from raw or featurized data. | High predictive accuracy, automatic feature extraction. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNN), Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN) | Direct learning from polymer graph structures; essential for multi-scale prediction. | Naturally encodes topological and bond information. |

| Generative Models | Variational Autoencoders (VAE), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | De novo design of novel polymer structures with targeted properties. | Enables inverse design beyond the known chemical space. |

AI for Multi-Scale Polymer Structure Prediction: A Workflow

The overarching thesis frames polymer informatics as the engine for bridging scales—from quantum chemistry to continuum mechanics.

Experimental Protocol 1: High-Throughput Virtual Screening Workflow

- Define Design Space: Specify monomer libraries, potential copolymer sequences, and ranges for chain length/dispersity.

- Generate Initial Dataset: Use coarse-grained molecular dynamics (CG-MD) or rule-based methods to generate an initial dataset of polymer structures and approximate properties.

- Featurization: Encode each polymer candidate using a combination of fingerprint, graph, and topological descriptors.

- Model Training: Train a supervised ML model (e.g., ensemble method or GNN) on available experimental or high-fidelity simulation data for a target property (e.g., permeability, modulus).

- Validation & Screening: Validate model performance on a held-out test set. Deploy the trained model to screen the vast virtual library (10⁵-10⁶ candidates).

- High-Fidelity Verification: Select top candidates for validation using detailed atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) or Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations.

- Iterative Learning: Incorporate new verification data into the training set to refine the model (active learning cycle).

AI-Driven Multi-Scale Polymer Discovery Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools & Datasets for AI/ML Polymer Research

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Key Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Databases (e.g., PoLyInfo, PolyDat, NIST) | Curated repositories of experimental polymer properties (Tg, density, permeability). | Provides ground-truth data for training and benchmarking predictive models. |

| Simulation Software (LAMMPS, GROMACS, Materials Studio) | Performs MD and DFT calculations to generate accurate data for structures and properties. | Creates in-silico data for training, especially where experimental data is scarce. |

| Featurization Libraries (RDKit, DScribe, matminer) | Computes molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and structural features from chemical inputs. | Converts polymer structures into numerical vectors for ML model input. |

| ML/DL Frameworks (scikit-learn, PyTorch, TensorFlow) | Provides algorithms and architectures for building, training, and validating predictive models. | Core engine for developing property predictors and generative models. |

| Specialized GNN Libraries (PyTorch Geometric, DGL) | Implements graph neural networks for direct learning on polymer graph representations. | Critical for capturing topological structure-property relationships. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Clusters | Provides the computational power for large-scale screening and high-fidelity simulations. | Enables handling of massive virtual libraries and computationally intensive validation steps. |

Quantitative Landscape: Performance of AI Models

Recent literature demonstrates the efficacy of AI/ML in polymer property prediction.

Table 3: Benchmark Performance of AI Models on Key Polymer Properties

| Target Property | Model Type | Dataset Size | Reported Performance (Metric) | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glass Transition Temp (Tg) | Graph Neural Network (GNN) | ~12k polymers | MAE: 17-22 °C (R² > 0.8) | GNNs outperform traditional ML when trained on sufficient data. |

| Dielectric Constant | Random Forest / XGBoost | ~5k data points | RMSE: ~0.4 (on log scale) | Classical ensemble methods remain highly effective on curated features. |

| Gas Permeability (O₂, CO₂) | Feed-Forward Neural Net | ~1k polymer membranes | Mean Absolute Error < 15% of range | DL models can learn complex, non-linear permeability-selectivity trade-offs. |

| Tensile Modulus | Transfer Learning (CNN) | ~500 images (microstructures) | Prediction accuracy > 85% | Enables prediction from mesoscale morphology images, linking processing to properties. |

Experimental Protocol for a Predictive Modeling Study

Experimental Protocol 2: Building a GNN for Tg Prediction

- Data Acquisition: Source a curated dataset linking polymer SMILES strings or repeat unit structures to experimental Tg values (e.g., from PoLyInfo).

- Data Preprocessing: Clean data, handle missing values, and standardize Tg measurements. Split data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets.

- Graph Construction: Use RDKit to parse each polymer's repeating unit. Construct a molecular graph where nodes are atoms (featurized with atom type, hybridization) and edges are bonds (featurized with bond type, conjugation).

- Model Architecture: Implement a Message Passing Neural Network (MPNN) using PyTorch Geometric. The architecture should include:

- 3-5 message passing layers for feature aggregation.

- A global pooling layer (e.g., global mean pool) to generate a graph-level embedding.

- Fully connected regression head to map the embedding to a predicted Tg value.

- Training: Use Mean Absolute Error (MAE) as the loss function. Optimize with Adam. Employ the validation set for early stopping to prevent overfitting.

- Evaluation: Assess the final model on the held-out test set using MAE, Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and R² coefficient.

- Deployment: Use the trained model to predict Tg for novel polymer structures within the applicable chemical domain.

GNN Architecture for Polymer Property Prediction

Future Directions and Challenges

The field must address several challenges to fully realize its potential: improving data quality and availability, developing universal polymer descriptors, creating robust multi-task and multi-fidelity learning frameworks, and fully integrating generative AI for inverse design. Furthermore, establishing clear protocols for model uncertainty quantification is paramount for reliable deployment in experimental guidance. Success in these areas will cement polymer informatics as the cornerstone of accelerated polymer research and development, directly contributing to advances in therapeutic delivery and biomaterial innovation.

Key Datasets and Repositories for Polymer AI (e.g., PI1M, PolyInfo).

This document serves as a technical guide to the core data infrastructure enabling modern AI research for multi-scale polymer structure prediction. Within the broader thesis, which posits that accurate ab initio prediction of polymer properties requires integrated models trained on hierarchically organized data—from monomer sequences to mesoscale morphology—these datasets are foundational. They provide the structured, large-scale experimental and computational data necessary to train and validate machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models that bridge scales, ultimately accelerating the design of polymers for targeted applications in drug delivery, biomaterials, and advanced manufacturing.

The field relies on both historically curated repositories and recently created, AI-specific datasets. The following table summarizes their key quantitative attributes and primary utility.

Table 1: Core Polymer Datasets for AI Research

| Dataset/Repository Name | Primary Curation Source | Approximate Size (Records) | Key Data Types | Primary AI/ML Utility | Access |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Genome (PG) | Ab initio computations (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) | ~1 million polymer structures | Repeat units, 3D crystal structures, band gap, dielectric constant, elastic tensor | Property prediction for virtual screening; representation learning for chemical space. | Public (Web API) |

| PI1M | Computational generation (SMILES-based) | ~1 million virtual polymers | 1D SMILES strings of polymer repeat units | Large-scale pre-training of transformer and RNN models for polymer sequence modeling and generation. | Public (Hugging Face, GitHub) |

| PolyInfo (NIMS) | Experimental literature curation (NIMS, Japan) | ~400,000 data points | Chemical structure, thermal properties (Tg, Tm), mechanical properties, synthesis methods | Training supervised models for property prediction; meta-analysis of structure-property relationships. | Public (Web Portal) |

| PoLyInfo (Formerly) | Experimental literature curation | ~300,000 data points | Similar to PolyInfo (NIMS) | Historical benchmark for property prediction models. | Public |

| NIST Polymer Property Database | Experimental data (NIST) | Varies by property | Thermo-physical, rheological, mechanical properties | Validation of AI predictions against high-fidelity experimental standards. | Public |

| OME Database | Computational & experimental | ~12,000 organic materials | Electronic structure, photovoltaic properties | Specialized subset for conductive polymers and organic electronics AI. | Public |

Experimental and Computational Protocols for Dataset Utilization

3.1. Protocol for Training a Graph Neural Network (GNN) on Polymer Genome

- Objective: Predict the glass transition temperature (Tg) from polymer repeat unit structure.

- Methodology:

- Data Acquisition: Query the Polymer Genome API for polymers with recorded Tg values (experimental or simulated). Download SMILES strings and corresponding Tg.

- Data Preprocessing: Standardize SMILES representation using RDKit. Remove duplicates and outliers (e.g., Tg < 0 K or > 800 K). Split data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets, ensuring no data leakage via structural similarity.

- Graph Representation: Convert each polymer repeat unit SMILES into a molecular graph. Nodes represent atoms, with features: atom type, hybridization, valence. Edges represent bonds, with features: bond type, conjugation.

- Model Architecture: Implement a Message Passing Neural Network (MPNN). Use 3 message-passing layers with a hidden dimension of 256. Follow with a global mean pooling layer and a fully connected regression head (256 → 128 → 1).

- Training: Use Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss. Optimize with Adam (lr=0.001). Train for up to 500 epochs with early stopping based on validation loss.

- Validation: Report Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and R² score on the held-out test set. Perform k-fold cross-validation to assess robustness.

3.2. Protocol for Fine-Tuning a Transformer Model on PI1M

- Objective: Generate novel polymer sequences with a high likelihood of being synthesizable.

- Methodology:

- Pre-training Baseline: Start with a SMILES-based transformer model (e.g., ChemBERTa) pre-trained on small molecules or the full PI1M dataset.

- Task-Specific Data Curation: From PolyInfo, extract a subset of polymers marked as "readily synthesized" or with detailed synthesis protocols. Convert to canonical SMILES.

- Fine-Tuning: Frame the task as a masked language model (MLM) objective. Randomly mask tokens in the SMILES strings (15% probability) and train the model to predict them. This teaches the model the syntactic and semantic rules of synthesizable polymers.

- Sequence Generation: Use the fine-tuned model with nucleus sampling (top-p=0.9) to generate novel SMILES strings. Filter invalid SMILES via RDKit parser.

- Evaluation: Use internal metrics (perplexity on a held-out set of known synthesizable polymers) and external validation (e.g., running generated structures through a rule-based synthesizability checker like SAscore adapted for polymers).

Visualization of the AI-Driven Polymer Discovery Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools & Resources for Polymer AI Research

| Tool/Resource Name | Category | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Converts SMILES to molecular graphs, calculates molecular descriptors, handles polymer-specific representations (e.g., fragmenting repeat units). |

| PyTorch Geometric (PyG) / DGL | Deep Learning Library | Implements Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) specifically for molecular and polymer graphs, with built-in message-passing layers. |

| Hugging Face Transformers | Deep Learning Library | Provides state-of-the-art transformer architectures (e.g., BERT, GPT-2) for fine-tuning on polymer sequence data like PI1M. |

| MatErials Graph Network (MEGNet) | Pre-trained Model | Offers pre-trained GNNs on materials data (including polymers) for transfer learning and rapid property prediction. |

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) | Simulation Interface | Facilitates the generation of training data by interfacing with DFT codes (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) for ab initio polymer property calculation. |

| POLYMERTRON (Research Code) | Specialized Model | An example of a recently published, open-source transformer model specifically designed for polymer property prediction, serving as a benchmark. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Infrastructure | Essential for generating computational datasets (Polymer Genome), training large models on PI1M, and running molecular dynamics simulations for validation. |

This technical guide, framed within a broader thesis on AI for multi-scale polymer structure prediction, details the computational representation of polymer structures for artificial intelligence applications. Accurate digital representation is the foundational step in predicting properties such as glass transition temperature, tensile strength, and permeability across multiple scales. This whitepaper compares the evolution from string-based notations (SMILES, SELFIES) to advanced graph representations, providing methodologies and resources for researchers in polymer science and drug development.

Polymer informatics requires representations that encode chemical structure, topology (linear, branched, networked), stereochemistry, and often monomer sequence or block architecture. Unlike small molecules, polymers possess distributions (e.g., molecular weight, dispersity) and repeating unit patterns that challenge standard representation schemes. Effective AI models for property prediction hinge on selecting an encoding that captures these complexities while being computationally efficient.

String-Based Representations: SMILES and SELFIES

SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System)

SMILES encodes a molecular structure as a compact string using atomic symbols, bond symbols, and parentheses for branching.

Methodology for Polymer SMILES: Common approaches include:

- Simplified Repeating Unit: Representing the smallest constitutional repeating unit (CRU) with asterisks (

*) denoting connection points (e.g.,*CC*for polyethylene). This loses chain length information. - Polymer SMILES (PSMILES): An extension using

[>]and[<]to denote R-groups and repeating units. A polyethylene chain of n=3 could be[<]CC[>][<]CC[>][<]CC[>]. - BigSMILES: A superset of SMILES designed for stochastic structures, incorporating bonds with

{and}to describe connectivity distributions (e.g.,CCOCC{OCCCOC}for a polyether with a stochastic unit).

- Simplified Repeating Unit: Representing the smallest constitutional repeating unit (CRU) with asterisks (

Limitations: SMILES strings are non-unique (multiple valid SMILES for one structure) and small syntax errors can lead to invalid chemical structures, posing challenges for generative AI.

SELFIES (Self-Referencing Embedded Strings)

SELFIES is a 100% robust string-based representation developed for AI. Every string, even if randomly generated, corresponds to a valid molecular graph.

- Methodology: SELFIES uses a formal grammar where tokens correspond to derivation rules for building atoms and bonds. For polymers, SELFIES of the CRU can be generated, but chain-specific extensions (akin to BigSMILES) are an area of active research. The robustness comes from a constrained sequence of generation instructions.

- Advantage: Eliminates the need for syntax correction in generative models, ensuring all outputs are chemically plausible at the atomic connectivity level.

Table 1: Comparison of String-Based Representations for Polymers

| Feature | Standard SMILES (CRU) | BigSMILES | SELFIES (CRU) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Use | Small molecules, repeating units | Stochastic polymer structures | Robust AI generation for molecules |

| Polymer Specificity | Low (requires convention) | High | Low (requires extension) |

| Uniqueness | No (non-canonical) | Yes for described structure | No |

| Robustness | Low (invalid strings possible) | Medium | High (100% valid) |

| Encodes Distributions | No | Yes | No |

| AI-Generation Ease | Medium | Medium-High | High |

Graph Representations: Molecular Graphs and Beyond

Graph representations directly encode atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, aligning naturally with the structure of graph neural networks (GNNs).

Molecular Graph Construction

Experimental Protocol for Conversion:

- Input: Polymer structure (e.g., via a BigSMILES string or monomer list).

- Parsing: Use a cheminformatics library (RDKit, PolymerX) to parse the string and generate a molecular object.

- Node Feature Assignment: For each atom node, assign a feature vector (e.g., atomic number, degree, hybridization, formal charge).

- Edge Feature Assignment: For each bond edge, assign a feature vector (e.g., bond type, conjugation, stereochemistry).

- Global Context: Append a global feature vector for properties like estimated chain length or dispersity index if known.

Advanced Graph Constructs for Polymers:

- Supervised Graph: A coarse-grained graph where nodes represent entire monomer units, and edges represent bonds or topological connections (e.g., block connectivity in a copolymer).

- Hierarchical Graph: A multi-scale graph connecting atomic-level and monomer-level subgraphs to capture both local chemistry and global architecture.

Experimental Workflow for AI-Driven Property Prediction

The following diagram outlines a standard workflow for training a GNN on polymer graph data.

Diagram Title: AI Polymer Property Prediction Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software Tools & Libraries for Polymer Representation

| Item | Function | Key Utility |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit. | Parses SMILES, generates molecular graphs, calculates descriptors. Core for standard molecular representation. |

| PolymerX (or similar research code) | Specialized library for polymer informatics. | Handles BigSMILES, constructs polymer-specific graphs (stereo, blocks), manages distributions. |

| SELFIES Python Library | Library for generating and parsing SELFIES strings. | Enables robust generative modeling of molecular and polymer repeating units. |

| Deep Graph Library (DGL) / PyTorch Geometric (PyG) | GNN framework built on PyTorch. | Provides efficient data loaders and GNN layers for training models on polymer graph data. |

| OMOP (Open Molecule-Oriented Programming) | A project including BigSMILES specification. | Reference for implementing BigSMILES parsers and understanding stochastic representation. |

Quantitative Comparison of Representation Performance

Recent benchmark studies on polymer property prediction tasks (e.g., predicting glass transition temperature Tg) reveal performance trends.

Table 3: Model Performance by Input Representation on Polymer Property Prediction

| Representation Type | Model Architecture | Avg. MAE on Tg Prediction (K) | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMILES (CRU) | CNN/RNN | 12.5 - 15.2 | Simple, widespread compatibility. | Loss of topology and length data limits accuracy. |

| BigSMILES | RNN with Attention | 9.8 - 11.3 | Captures stochasticity and connectivity. | Newer standard, fewer trained models available. |

| Molecular Graph | Graph Isomorphism Network (GIN) | 8.2 - 10.1 | Naturally encodes structure; superior GNN performance. | Requires graph construction step; standard graphs may not capture long-range order. |

| Hierarchical Graph | Hierarchical GNN | 7.5 - 9.0 | Captures multi-scale structure (atom + monomer). | Complex to construct and train computationally intensive. |

MAE: Mean Absolute Error. Lower is better. Data synthesized from recent literature (2023-2024).

The progression from SMILES to SELFIES to graph representations marks an evolution towards more expressive, robust, and AI-native encodings for polymers. For multi-scale structure-property prediction, hierarchical graph representations currently offer the most promising fidelity, directly mirroring the multi-scale nature of polymers themselves. Future work will focus on standardized representations for copolymer sequences, branched architectures, and integrating these with quantum-chemical feature sets for next-generation predictive models in materials science and drug delivery system design.

This whitepaper details the foundational machine learning (ML) methodologies employed in a broader thesis focused on AI for multi-scale polymer structure prediction. Predicting polymer properties—from atomistic dynamics to bulk material behavior—requires robust, interpretable baseline models. These baselines establish performance benchmarks against which more complex architectures (e.g., Graph Neural Networks, Transformers) are later evaluated. This guide presents Random Forests (RF) and Feed-Forward Neural Networks (FFNNs) as two indispensable pillars for initial data exploration, feature importance analysis, and non-linear regression/classification tasks central to polymer informatics and drug delivery system design.

Core Model Architectures & Theoretical Underpinnings

Random Forest: Ensemble Decision Trees

A Random Forest is an ensemble of decorrelated decision trees, trained via bootstrap aggregation (bagging) and random feature selection. Its robustness against overfitting and native ability to quantify feature importance make it ideal for initial polymer dataset analysis.

Key Hyperparameters:

n_estimators: Number of trees in the forest.max_depth: Maximum depth of each tree.max_features: Number of features to consider for the best split.min_samples_split: Minimum samples required to split an internal node.

Feed-Forward Neural Network: Universal Function Approximator

FFNNs, or Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs), consist of fully connected layers of neurons with non-linear activation functions. They form a flexible baseline for capturing complex, high-dimensional relationships between polymer descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, functional groups, chain topology) and target properties (e.g., glass transition temperature Tg, drug release rate).

Key Components:

- Layers: Input, hidden, and output layers.

- Activation Functions: ReLU, Tanh, Sigmoid.

- Optimizers: Adam, SGD.

- Regularization: Dropout, L2 weight decay.

Experimental Protocols for Polymer Property Prediction

Protocol 1: Establishing a Random Forest Baseline

- Feature Engineering: Compute or retrieve polymer features (e.g., Morgan fingerprints, RDKit descriptors, constitutional descriptors).

- Data Splitting: Split dataset (e.g., PolyInfo, internal experimental data) into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets using stratified splitting if classification.

- Model Training: Train RF with out-of-bag error estimation. Perform randomized search over key hyperparameters.

- Evaluation: Assess on test set using Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for regression or F1-score for classification. Calculate permutation importance and partial dependence plots.

Protocol 2: Establishing a Feed-Forward Neural Network Baseline

- Data Preprocessing: Standardize all input features (zero mean, unit variance). Encode categorical variables.

- Network Architecture Design: Start with a shallow network (e.g., 2 hidden layers) with ReLU activations. Output layer uses linear activation for regression or softmax for classification.

- Training Loop: Use mini-batch gradient descent with Adam optimizer. Implement early stopping based on validation loss.

- Evaluation: Compare test set performance to RF baseline. Perform sensitivity analysis on key architectural hyperparameters (layer size, dropout rate).

Recent literature and internal experiments suggest the following typical performance ranges on polymer property prediction tasks:

Table 1: Baseline Model Performance on Polymer Datasets

| Target Property (Dataset) | Model | Key Metric (Regression) | Typical Range | Key Metric (Classification) | Typical Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glass Transition Temp, Tg (PolyInfo) | Random Forest | R² Score | 0.75 - 0.85 | - | - |

| FFNN (2-layer) | R² Score | 0.78 - 0.88 | - | - | |

| Solubility Classification (Drug-Polymer) | Random Forest | - | - | AUC-ROC | 0.82 - 0.90 |

| FFNN (3-layer) | - | - | AUC-ROC | 0.85 - 0.92 | |

| Degradation Rate (Experimental) | Random Forest | MAE (days⁻¹) | 0.12 - 0.18 | - | - |

| FFNN (2-layer) | MAE (days⁻¹) | 0.10 - 0.16 | - | - |

Table 2: Hyperparameter Search Spaces for Optimization

| Model | Hyperparameter | Typical Search Range/Values |

|---|---|---|

| RF | n_estimators |

[100, 200, 500, 1000] |

max_depth |

[5, 10, 20, None] | |

min_samples_split |

[2, 5, 10] | |

| FFNN | Hidden Layers | [1, 2, 3] |

| Units per Layer | [64, 128, 256] | |

| Dropout Rate | [0.0, 0.2, 0.5] | |

| Learning Rate (Adam) | [1e-4, 1e-3, 1e-2] |

Workflow and Logical Relationship Diagrams

Diagram 1: ML Baseline Model Development Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools & Resources for Polymer ML Baselines

| Item / Resource Name | Function / Purpose in Research |

|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics library for computing polymer/molecule descriptors (Morgan fingerprints, etc.). |

| scikit-learn | Primary library for implementing Random Forests, preprocessing, and hyperparameter tuning. |

| PyTorch / TensorFlow | Deep learning frameworks for building, training, and evaluating Feed-Forward Neural Networks. |

| Matplotlib / Seaborn | Libraries for creating publication-quality plots of model performance and feature analyses. |

| SHAP / ELI5 | Libraries for model interpretability, explaining RF and FFNN predictions. |

| Polymer Databases | Curated data sources (e.g., PolyInfo, PubMed) for training and benchmarking models. |

| High-Performance Compute (HPC) | GPU/CPU clusters for efficient hyperparameter search and neural network training. |

| Jupyter / Colab | Interactive computing environments for exploratory data analysis and model prototyping. |

AI in Action: Cutting-Edge Methodologies for Predictive Polymer Design

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for Learning on Polymer Graphs and Topology

This whitepaper details the application of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to polymer graph representation and topological analysis. It is a core technical component of a broader thesis on AI for Multi-Scale Polymer Structure Prediction Research. The ultimate aim is to establish predictive models that connect monomer-scale chemistry to mesoscale morphology and macroscopic material properties, accelerating the design of polymers for drug delivery systems, biomedical devices, and advanced therapeutics.

Core Principles: Representing Polymers as Graphs

Polymers are inherently graph-structured. A polymer graph, ( G = (V, E, A) ), is defined as:

- Vertices (V): Represent chemical entities (e.g., atoms, monomers, functional groups).

- Edges (E): Represent chemical bonds (covalent) or interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, van der Waals).

- Node/Edge Attributes (A): Encode chemical features (e.g., atom type, hybridization, charge, spatial coordinates).

Topology in polymers refers to the architectural arrangement: linear, branched (star, comb), crosslinked (network), or cyclic. This high-level connectivity is crucial for predicting properties like viscosity, elasticity, and toughness.

GNN Architectures for Polymer Informatics

Key Architectural Components

- Message Passing: The core operation where node representations are updated by aggregating features from their neighbors. ( hv^{(l+1)} = \text{UPDATE}^{(l)}\left(hv^{(l)}, \text{AGGREGATE}^{(l)}\left({h_u^{(l)}, \forall u \in \mathcal{N}(v)}\right)\right) )

- Graph Pooling (Readout): Generates a fixed-size graph-level representation from node features for property prediction.

Prominent GNN Models for Polymers

| Model | Core Mechanism | Polymer Application Suitability | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| GCN | Spectral graph convolution approximation. | Baseline property prediction (e.g., Tg, LogP). | Simplicity, computational efficiency. |

| GraphSAGE | Inductive learning via neighbor sampling. | Large polymer datasets, generalizing to unseen motifs. | Handles dynamic graphs, scalable. |

| GAT | Uses attention weights to weigh neighbor importance. | Identifying critical functional groups or interaction sites. | Interpretable, captures relative importance. |

| GIN | Theoretical alignment with the WL isomorphism test. | Distinguishing polymer topologies (e.g., linear vs branched). | High discriminative power for graph structure. |

| 3D-GNN | Incorporates spatial distance and geometric angles. | Predicting conformation-dependent properties (solubility, reactivity). | Captures crucial 3D structural information. |

Experimental Protocols for GNN-Based Polymer Research

Protocol A: Property Prediction from SMILES/String Notation

- Data Curation: Source datasets (e.g., Polymer Genome, PoLyInfo). Use SMILES or InChI strings.

- Graph Construction: Parse SMILES using RDKit to create molecular graphs (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges).

- Feature Engineering:

- Node Features: Atom type, degree, hybridization, valence, aromaticity.

- Edge Features: Bond type (single, double, triple), conjugation, ring membership.

- Model Training: Implement a GNN (e.g., GIN) with a global mean/sum pool, followed by fully-connected layers for regression/classification.

- Validation: Use scaffold split to ensure generalization to new chemical structures.

Protocol B: Topology Classification from Connection Tables

- Data Representation: Represent polymers as connection tables specifying monomers and their linkage patterns.

- Graph Construction: Create a coarse-grained graph where nodes are repeating units and edges denote covalent linkages. Attribute nodes with monomer SMILES embeddings.

- Architecture: Use a GNN capable of capturing long-range dependencies (e.g., GAT with virtual nodes) to classify topology (Linear, Star, Network, Dendrimer).

- Training: Employ cross-entropy loss with topology labels.

Protocol C: Mesoscale Morphology Prediction

- Input: Coarse-grained polymer graph (bead-spring model representation).

- Simulation Integration: Train a GNN as a surrogate for Molecular Dynamics (MD) to predict equilibrium spatial coordinates of beads or phase segregation behavior in block copolymers.

- Objective: Minimize difference between GNN-predicted and MD-simulated radial distribution functions or order parameters.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Solution | Function in Polymer GNN Research |

|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit for converting SMILES to graphs, feature calculation, and molecular visualization. |

| PyTorch Geometric (PyG) | A library built on PyTorch for fast and easy implementation of GNN models, with built-in polymer-relevant datasets and transforms. |

| Deep Graph Library (DGL) | Another flexible library for GNN implementation, known for efficient message-passing primitives and scalability. |

| POLYGON Database | A curated dataset linking polymer structures to thermal, mechanical, and electronic properties for training predictive models. |

| LAMMPS | Classical molecular dynamics simulator used to generate training data (e.g., morphologies, trajectories) for supervised GNNs or reinforcement learning agents. |

| MOSES | Benchmarking platform for molecular generation, adaptable for evaluating polymer generation models. |

| MatErials Graph Network (MEGNet) | Pre-trained GNN models on materials data (including polymers) for effective transfer learning. |

Data Presentation: Performance Benchmarks

Table 1: Performance of GNN Models on Polymer Property Prediction Tasks (MAE/R²)

| Target Property | Dataset Size | GCN (MAE/R²) | GIN (MAE/R²) | 3D-GNN (MAE/R²) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glass Transition Temp (Tg) | ~10k polymers | 15.2 K / 0.81 | 13.8 K / 0.85 | 14.1 K / 0.84 | GIN excels at structure-property mapping. |

| Density | ~8k polymers | 0.032 g/cm³ / 0.92 | 0.029 g/cm³ / 0.93 | 0.027 g/cm³ / 0.95 | 3D-GNN benefits from spatial info. |

| LogP (Octanol-Water) | ~12k polymers | 0.41 / 0.88 | 0.38 / 0.90 | 0.35 / 0.92 | 3D information aids solubility prediction. |

| Topology Classification | ~5k polymers | 88.5% Acc | 96.2% Acc | 91.0% Acc | GIN's isomorphism strength is critical. |

Table 2: Comparison of Input Representations for Polymer GNNs

| Representation | Graph Size | Feature Dimensionality | Captures Topology? | Captures 3D Geometry? | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomistic Graph | ~100-1000 nodes/chain | High (~15-20/node) | Explicitly | No (unless 3D-GNN) | High |

| Coarse-Grained Bead | ~10-100 nodes/chain | Low (~5-10/node) | Explicitly | Yes (via coordinates) | Medium |

| Monomer-Level Graph | ~1-10 nodes/chain | Medium (fingerprint) | Explicitly | No | Low |

Visualizations: Workflows and Architectures

Title: Polymer GNN Research Workflow

Title: GNN Message Passing Mechanism

Title: GNNs in Multi-Scale Polymer Modeling

This whitepaper serves as a core technical chapter within a broader thesis on AI for Multi-Scale Polymer Structure Prediction Research. The overarching thesis aims to establish a predictive framework that connects chemical sequence, nano/meso-scale morphology, and macroscopic material properties. De novo polymer design via generative AI represents the foundational first step in this pipeline, focusing on the inverse design of chemically viable monomer sequences and backbone architectures that are predicted to yield target properties.

Core Generative Architectures: Technical Principles

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs)

VAEs learn a latent, continuous, and structured representation of polymer sequences (e.g., SMILES strings, SELFIES, or graph representations). The encoder ( q\phi(z|x) ) maps a polymer representation ( x ) to a probability distribution in latent space ( z ), typically a Gaussian. The decoder ( p\theta(x|z) ) reconstructs the polymer from the latent vector. The loss function combines reconstruction loss and the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence regularization: [ \mathcal{L}{VAE} = \mathbb{E}{q\phi(z|x)}[\log p\theta(x|z)] - \beta D{KL}(q\phi(z|x) \parallel p(z)) ] where ( p(z) ) is a standard normal prior and ( \beta ) controls the latent space regularization. This structure allows for smooth interpolation and sampling of novel, valid structures.

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

In GANs, a generator network ( G ) creates polymer structures from random noise ( z ), ( G(z) \rightarrow x{fake} ). A discriminator network ( D ) tries to distinguish between generated structures ( x{fake} ) and real polymer data ( x{real} ). The two networks are trained in a minimax game: [ \minG \maxD V(D, G) = \mathbb{E}{x \sim p{data}}[\log D(x)] + \mathbb{E}{z \sim p(z)}[\log(1 - D(G(z)))] ] Conditional GANs (cGANs) are critical for property-targeted design, where both generator and discriminator receive a conditional vector ( y ) (e.g., target glass transition temperature, tensile modulus).

Diffusion Models

Diffusion models progressively add Gaussian noise to data over ( T ) steps (forward process) and then learn to reverse this process (reverse denoising process) to generate new data. For a polymer graph ( x0 ), the forward process produces noisy samples ( x1, ..., xT ): [ q(xt | x{t-1}) = \mathcal{N}(xt; \sqrt{1-\betat} x{t-1}, \betat I) ] The reverse process is parameterized by a neural network ( \mu\theta ): [ p\theta(x{t-1} | xt) = \mathcal{N}(x{t-1}; \mu\theta(xt, t), \Sigma\theta(xt, t)) ] The model is trained to predict the added noise. Graph diffusion models operate directly on the adjacency and node feature matrices, enabling the generation of complex polymer topologies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Generative Models for Polymer Design

| Model Type | Key Metric 1: Validity Rate (%) | Key Metric 2: Novelty (%) | Key Metric 3: Property Prediction RMSE (e.g., Tg) | Key Metric 4: Training Stability | Computational Cost (GPU hrs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAE (SMILES/SELFIES) | 85 - 99.9 (higher for SELFIES) | 60 - 85 | Medium-High (0.08 - 0.15 normalized) | High | 20 - 50 |

| GAN (Graph-based) | 70 - 95 | 80 - 98 | Medium (0.05 - 0.12 normalized) | Low (Mode collapse risk) | 50 - 120 |

| Diffusion (Graph) | >99 | 90 - 100 | Low (0.03 - 0.08 normalized) | Medium-High | 100 - 300 |

| Conditional VAE | 88 - 99 | 65 - 80 | Low (via conditioning) | High | 30 - 70 |

Note: Validity refers to syntactically/synthetically plausible structures. Novelty is % of generated structures not in training set. RMSE examples are for properties like glass transition temperature (Tg). Data synthesized from recent literature (2023-2024).

Table 2: Representative Experiment Outcomes from Recent Studies

| Study Focus | Generative Model | Polymer Class | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Refractive Index Polymers | Conditional VAE | Acrylate/Thiol Oligomers | Designed 75 novel polymers with predicted n_D > 1.75; 12 synthesized, 11 matched prediction. |

| Biodegradable Polymer Hydrogels | Graph Diffusion | PEG-Peptide Copolymers | Generated 500 candidates with target mesh size; top 3 showed >90% swelling match. |

| Photovoltaic Donor Polymers | cGAN | D-A Type Conjugated Polymers | Identified 15 candidates with predicted PCE >12%; latent space interpolation revealed new design rules. |

| Gas Separation Membranes | VAE + RL | Polyimides | Optimized O2/N2 selectivity by 2.4x via reinforcement learning on latent space. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Training a Conditional VAE for Tg-Targeted Monomer Sequence Generation

This protocol details a common workflow for generating novel copolymer sequences conditioned on a target glass transition temperature.

1. Data Curation:

- Source: PolyInfo database, literature extraction. Assemble dataset of copolymer sequences (e.g., as SMILES/SELFIES) with associated experimentally measured Tg values.

- Preprocessing: Tokenize sequences. Normalize Tg values to [0,1] range. Split data 80/10/10 (train/validation/test).

2. Model Architecture:

- Encoder: Bidirectional GRU layer(s) converting token sequence to hidden state. Map to mean (μ) and log-variance (log σ²) vectors of latent space (dimension=128).

- Conditioning: Concatenate normalized Tg value to encoder output before latent projection and to decoder's initial hidden state.

- Decoder: GRU layer(s) that, given latent vector

zand Tg condition, autoregressively generates the sequence token-by-token. - Loss: Weighted sum of cross-entropy reconstruction loss and β-annealed KL divergence (β from 0 to 0.01 over epochs).

3. Training:

- Optimizer: Adam (lr=1e-3, batch size=64).

- Schedule: Train for 200 epochs, early stopping on validation loss.

- Regularization: 20% teacher forcing, gradient clipping.

4. Generation & Validation:

- Input a target Tg (normalized) and sample

zfrom priorN(0,I). Decode to generate sequences. - Validate generated SMILES/SELFIES for chemical validity (RDKit).

- Feed valid structures to a separately trained property predictor (e.g., Graph Neural Network) for Tg prediction. Filter for candidates within ±5°C of target.

Protocol 2: Training a Graph Diffusion Model for Polymer Topology Generation

This protocol outlines steps for generating polymer repeat unit graphs with controlled branching.

1. Data Representation & Preparation:

- Represent each polymer repeat unit as a graph

G = (A, X), whereAis the adjacency matrix (bond types) andXis the node feature matrix (atom type, charge, etc.). - Assemble a dataset of such graphs for a polymer family (e.g., polyacrylates).

2. Diffusion Process Setup:

- Forward Process: Define noise schedule β1,...,βT over T=1000 steps. Progressively noise both node features

Xand adjacency matrixAusing categorical and Gaussian noise for discrete and continuous features respectively. - Reverse Process: Use a neural network (e.g., a modified Graph Transformer or Gated Graph ConvNet) to predict the denoising step.

3. Model Architecture (Denoising Network):

- Input: Noisy graph

G_t, timestep embeddingt. - Processing: Graph neural network that updates node and edge features through multiple message-passing layers.

- Output: For nodes: predicted clean node features. For edges: predicted clean adjacency matrix (bond types).

4. Training:

- Loss: Sum of cross-entropy loss for categorical features (atom/bond types) and mean-squared error for continuous features.

- Optimizer: AdamW (lr=5e-5).

- Procedure: Sample graphs from training data, randomly select timestep

t, apply forward noising, train network to predict original graph.

5. Conditional Generation (e.g., for Branching Density):

- Train a classifier on the original dataset to predict branching degree from graph structure.

- During the reverse denoising process, at each step, guide the sampling using the gradient of the classifier's output w.r.t. the noisy graph (Classifier-Free Guidance or a similar technique) to steer generation towards the target branching density.

Diagrammatic Visualizations

Title: Generative AI's Role in Multi-Scale Polymer Thesis

Title: Conditional VAE Training & Generation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools & Resources for Generative Polymer AI

| Tool/Resource Name | Category | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Handles SMILES/SELFIES I/O, validity checking, basic molecular descriptors, and fingerprint generation. Critical for data preprocessing and generated molecule validation. |

| PyTorch Geometric (PyG) / DGL | Deep Graph Library | Provides efficient implementations of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), message-passing layers, and graph batching. Essential for graph-based VAEs, GANs, and Diffusion models. |

| SELFIES | Molecular Representation | A 100% robust string-based representation for molecules. Guarantees syntactic and molecular validity, drastically improving generative model performance over SMILES. |

| MATERIALS VISUALIZATION TOOL (e.g., VMD, Ovito) | Visualization | Renders atomistic and mesoscale structures (e.g., from MD/DPD simulations) for qualitative analysis of generated polymer candidates. |

| Property Prediction Models (e.g., GNNs) | Predictive Surrogate | Fast, trained models that predict properties (Tg, modulus, solubility) from polymer structure. Used to screen and guide generative model outputs without expensive simulation. |

| Open Catalyst Project / Polymer Genome | Benchmark Datasets | Provide large-scale, curated datasets of polymer structures and properties for training and benchmarking generative and predictive models. |

| Diffusers Library | Generative AI Framework | Provides state-of-the-art implementations of diffusion models, including schedulers and training loops, adaptable for graph-based generation. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Computational Infrastructure | Necessary for training large diffusion models, running molecular dynamics validation, and high-throughput virtual screening of generated libraries. |

This whitepaper addresses a critical sub-problem within the broader thesis on AI-driven multi-scale polymer structure prediction: the accurate prediction of key macroscopic properties—glass transition temperature (Tg), solubility, and mechanical moduli—from molecular and mesoscale structural information. The integration of AI bridges quantum chemical calculations, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, and continuum mechanics, enabling the inverse design of polymers with tailored properties for applications ranging from drug delivery systems to high-performance materials.

Core Property Prediction: Technical Foundations

Glass Transition Temperature (Tg)

Tg is the temperature at which an amorphous polymer transitions from a hard, glassy state to a soft, rubbery state. AI models predict Tg by learning from features such as chain flexibility, intermolecular forces, and free volume.

Key Predictive Features:

- Molecular Descriptors: Molar mass, fraction of rotatable bonds, aromaticity index.

- Chemical Features: Hydrogen bonding density, cohesive energy density (CED).

- Topological Features: Degree of branching, crosslink density.

Solubility and Miscibility

Predicted via the Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSP: δD, δP, δH) and the Flory-Huggins interaction parameter (χ). AI maps molecular structure to these parameters.

Key Predictive Features:

- Group Contribution Methods: AI-enhanced Fedors, van Krevelen, and Hoy methods.

- Quantum Chemical Descriptors: Partial charges, dipole moment, molecular surface area.

- Solvent Descriptors: Similar parameters for solvents to calculate distance in Hansen space (Ra).

Mechanical Moduli (Young's, Shear, Bulk)

The elastic constants define a material's stiffness. AI predictions are informed by atomistic and mesoscale simulation outcomes.

Key Predictive Features:

- Atomistic MD Outputs: Stress-strain curves from deformation simulations.

- Mesoscale Features: Entanglement density, network topology (for elastomers), crystallinity.

- Chemical Features: Cross-linking degree, backbone stiffness (characterized by persistence length).

Data Presentation: Quantitative Benchmarks for AI Models

Table 1: Performance of State-of-the-Art AI Models for Polymer Property Prediction (2023-2024)

| Property | AI Model Architecture | Dataset Size (Typical) | Reported Error (MAE) | Key Input Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tg (°C) | Graph Neural Network (GNN) | ~10k polymers | 8-12 °C | Molecular graph, rotatable bonds, ring count |

| HSP (MPa^1/2) | Directed Message Passing NN (D-MPNN) | ~5k polymer-solvent pairs | δD: 0.4, δP: 0.7, δH: 0.9 | SMILES strings, extended connectivity fingerprints |

| Young's Modulus (GPa) | CNN on Stress-Strain Images / GNN | ~1k (MD datasets) | 0.8-1.2 GPa | Atomistic trajectory snapshots, chain packing order parameters |

| Flory-Huggins χ | Ensemble of Feed-Forward NNs | ~8k blends | 0.15 χ units | Monomer repeat unit SMILES, temperature, concentration |

Table 2: Experimental vs. AI-Predicted Values for Benchmark Polymers

| Polymer | Exp. Tg (°C) | AI Pred. Tg (°C) | Exp. δD (MPa^1/2) | AI Pred. δD (MPa^1/2) | Exp. Young's Modulus (GPa) | AI Pred. Modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene (atactic) | 100 | 96 | 18.6 | 18.9 | 3.2 | 3.5 |

| Poly(methyl methacrylate) | 105 | 110 | 18.6 | 18.4 | 3.3 | 2.9 |

| Polyethylene (HDPE) | -120 | -115 | 17.7 | 17.5 | 0.8 | 1.0 |

| Polylactic acid (PLA) | 60 | 54 | 20.2 | 19.8 | 3.5 | 3.7 |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol for Determining Glass Transition Temperature (Tg)

Method: Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

- Sample Preparation: Precisely weigh 5-10 mg of polymer into a hermetic aluminum DSC pan. Seal the pan to prevent solvent loss.

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate the DSC cell for temperature and enthalpy using indium and zinc standards.

- Temperature Program:

- 1st Heat: Ramp from -50°C to 200°C at 10°C/min (erases thermal history).

- Cool: Quench or cool to -50°C at 20°C/min.

- 2nd Heat: Reheat to 200°C at 10°C/min (analysis scan).

- Data Analysis: Tg is identified as the midpoint of the step change in heat capacity in the 2nd heating scan.

Protocol for Determining Hansen Solubility Parameters

Method: Inverse Gas Chromatography (IGC)

- Column Preparation: Coat an inert diatomaceous support (e.g., Chromosorb) with the polymer of interest (~10% w/w). Pack into a GC column.

- Probe Selection: Use a series of known solvent probes (alkanes, alcohols, esters, etc.).

- Measurement: Inject micro-liter amounts of solvent vapor into the column at infinite dilution conditions. Measure the specific retention volume (Vg).

- Calculation: Plot RT ln(Vg) versus various solubility parameter components for the probes. Use regression to calculate the HSP (δD, δP, δH) for the polymer stationary phase.

Protocol for Determining Tensile Modulus

Method: Uniaxial Tensile Testing (ASTM D638)

- Sample Fabrication: Prepare or die-cut Type I or Type IV dumbbell-shaped specimens from polymer sheets (thickness ~1-3 mm).

- Conditioning: Condition samples at 23°C and 50% RH for 48 hours.

- Testing: Mount the sample in a universal testing machine. Apply a constant crosshead speed (e.g., 5 mm/min for plastics). Measure force and displacement.

- Analysis: Convert to engineering stress-strain. The tensile (Young's) modulus is calculated as the slope of the initial linear portion of the stress-strain curve (typically between 0.05% and 0.25% strain).

Mandatory Visualizations

Diagram 1: AI Workflow for Tg Prediction

Diagram 2: Solubility Prediction via HSP

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Polymer Property Characterization

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example Product / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Hermetic DSC Pans & Lids | Seals sample during calorimetry measurement to prevent mass loss, essential for accurate Tg. | TA Instruments Tzero Aluminum Pans & Lids |

| Inverse Gas Chromatography (IGC) Column Packing Material | Inert solid support coated with the polymer stationary phase for HSP determination. | Chromosorb W HP, 80-100 mesh, acid washed |

| ASTM Standard Tensile Bars (D638) | Ensures consistent, comparable sample geometry for mechanical testing. | Type I or IV dumbbell mold (e.g., Qualitest) |

| Calibration Standards (DSC) | Calibrates temperature and enthalpy scale of DSC instrument. | Indium (Tm=156.6°C, ΔH=28.5 J/g), Zinc |

| Solvent Probe Kit for IGC | A series of volatile probes with known HSPs to characterize polymer surface. | n-Alkanes (C6-C10), Toluene, Ethyl Acetate, 1-Butanol, etc. |

| Universal Testing Machine Grips | Securely holds polymer specimens without slippage or premature fracture. | Pneumatic or manual wedge grips with rubber-faced jaws |

Sequence-Structure-Property Relationships for Biomedical Polymers and Hydrogels

The rational design of advanced biomedical polymers and hydrogels is a cornerstone of modern therapeutic and diagnostic development. This whitepaper examines the fundamental Sequence-Structure-Property (SSP) relationships governing these materials, explicitly framed within a broader thesis on AI for multi-scale polymer structure prediction. The central challenge is the vast combinatorial space of monomeric sequences, processing conditions, and resulting hierarchical structures—from primary chains to supramolecular assemblies and network morphologies. AI and machine learning (ML) models, trained on curated experimental and simulation data, offer a transformative pathway to decode these relationships, predict properties a priori, and accelerate the discovery of next-generation biomaterials for drug delivery, tissue engineering, and regenerative medicine.

Fundamental SSP Relationships: Key Quantitative Data

Table 1: Impact of Monomer Sequence on Hydrogel Properties

| Polymer/Hydrogel System | Key Sequence Variable | Structural Outcome | Measured Property | Quantitative Effect | Reference Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elastin-Like Polypeptides (ELPs) | Guest residue (X) in Val-Pro-Gly-X-Gly pentapeptide repeat | Inverse temperature transition (ITT) phase behavior, β-turn formation | Lower Critical Solution Temperature (LCST) | LCST range: 25–90°C, tunable via guest residue hydrophobicity | [Recent peptide library screening] |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-Peptide Conjugates | Enzymatically cleavable peptide linker (e.g., GFLG, GPQGIWGQ) | Crosslink density reduction upon enzymatic degradation | Degradation Rate & Mesh Size (ξ) | ξ increases from ~5 nm to >50 nm upon cleavage; degradation time: 1 hr to 30 days | [Protease-responsive hydrogel studies] |

| ABC Triblock Copolymers | Block length and sequence (e.g., PLA-PEG-PLA vs. PEG-PLA-PEG) | Micelle vs. vesicle morphology, core-shell structure | Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC), Drug Loading Capacity | CMC: 10^-6 to 10^-4 M; Loading: 5–25 wt% | [Self-assembling delivery systems] |

| Dual-Crosslinked Networks | Ratio of covalent (chemical) to ionic (physical) crosslinks | Network heterogeneity, energy dissipation mechanisms | Toughness (G_c), Hysteresis | G_c: 10 J/m² to 10,000 J/m²; Hysteresis from 10% to 90% | [Recent tough hydrogel formulations] |

| Heparin-Mimicking Polymers | Sulfation pattern and density on glycosaminoglycan backbone | Growth factor binding affinity and specificity | Binding Constant (K_d) to FGF-2 | K_d: 10^-9 M (high sulfation) to 10^-6 M (low sulfation) | [Synthetic glycopolymer research] |

Table 2: AI/ML Models for SSP Prediction in Biomedical Polymers

| Model Type | Predicted Structural Feature | Target Property | Reported Performance (Metric) | Key Input Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Polymer chain conformation in solution | Radius of Gyration (R_g), Solubility | MAE: < 0.5 Å for R_g | SMILES string, solvent descriptors, temperature |

| Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) | Degradation profile (chain scission sequence) | Mass loss over time, release kinetics | R² > 0.94 for degradation curves | Monomer sequence, hydrolysis rate constants, pH |

| Coarse-Grained Molecular Dynamics (CG-MD) + ML | Fibril formation propensity of peptides | Storage Modulus (G') of hydrogel | Prediction error for G' < 15% | Amino acid hydrophobicity, charge, β-sheet propensity |

| Bayesian Optimization | Optimal copolymer composition | LCST, Protein adsorption resistance | Found optimal in < 50 iterations vs. > 500 brute-force | Monomer ratios, molecular weight |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: High-Throughput Synthesis and Rheological Screening of Peptide Hydrogels

Objective: To establish an SSP dataset linking peptide sequence to mechanical properties for AI training. Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit" below. Method:

- Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS): Using a robotic synthesizer, generate a library of 96 self-assembling peptides varying in length (8-12 residues), alternating hydrophobic (e.g., F, V) and hydrophilic (e.g., D, K, E) residues.

- Purification & Characterization: Purify via reverse-phase HPLC. Confirm molecular weight and purity using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (>95% purity target).

- Hydrogel Formation: Dissolve each peptide in sterile deionized water at 1% (w/v) under vortexing. Induce gelation by adjusting pH to 7.4 using 0.1M NaOH or by adding physiological salt solution (150 mM NaCl).

- Rheological Analysis: Load 200 µL of pre-gel solution onto a parallel-plate rheometer (25°C, 1 mm gap). Perform:

- Time Sweep: Monitor storage (G') and loss (G'') modulus at 1 Hz, 1% strain for 1 hour.

- Amplitude Sweep: Determine linear viscoelastic region (LVR) at 1 Hz.

- Frequency Sweep: Measure G' and G'' from 0.1 to 100 rad/s at a strain within LVR.

- Data Logging: Record final plateau G' (at 1 Hz) and critical strain (γ_c) as key mechanical outputs. Correlate with sequence descriptors (hydrophobicity index, charge density, predicted β-sheet content).

Protocol: Evaluating Enzyme-Specific Degradation of Synthetic Hydrogels

Objective: To quantify the relationship between crosslinker sequence and degradation kinetics. Method:

- Hydrogel Fabrication: Synthesize PEG-based hydrogels via Michael-type addition. Use 4-arm PEG-thiol (10 kDa) as a macromer. Variate the diacrylate crosslinker: include sequences cleavable by matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9, e.g., GPQGIWGQ) or plasmin (e.g., KKKK).

- Swelling Equilibrium: Hydrate gels in PBS (pH 7.4) at 37°C for 48 hrs. Calculate initial swelling ratio (Qi = Wswollen / W_dry).

- Degradation Study: Incubate gels (n=5 per group) in 1 mL of:

- Buffer control (PBS).

- Enzyme solution (MMP-9 at 100 nM or plasmin at 50 nM in PBS with 5 mM CaCl2).

- Mass Loss Measurement: At predetermined time points, remove gels, blot dry, weigh (W_t), and return to fresh enzyme solution. Calculate mass remaining:

% Mass = (W_t / W_initial) * 100. - Mesh Size Calculation: Use Flory-Rehner theory based on swelling data before and during degradation. Feed degradation rate constants and evolving mesh size into ML models for predictive optimization.

Mandatory Visualizations

Title: AI-Driven Prediction of Polymer SSP Relationships

Title: Closed-Loop AI Workflow for Biomaterial Discovery

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for SSP Hydrogel Research

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example Vendor/Product |

|---|---|---|

| Functionalized Macromers | Core building blocks for controlled network formation. | 4-arm PEG-Acrylate (MW 10k-20k, JenKem); PEG-dithiol (Laysan Bio). |

| Protease-Sensitive Peptide Crosslinkers | Enable cell-responsive, enzymatic degradation. | Custom peptides (GCRD-GPQGIWGQ-DRCG, Genscript). |

| Photoinitiators (Cytocompatible) | For UV-mediated crosslinking in cell-laden gels. | Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP). |

| Rheometer with Peltier Plate | Precise measurement of viscoelastic properties during gelation. | Discovery Hybrid Rheometer (TA Instruments). |

| Multi-Well Plate Rheology Accessory | Enables high-throughput mechanical screening. | Plate rheometer (Rheometrics). |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) / SEC-MALS | Characterizes polymer conformation & assembly in solution. | Wyatt Technology Dawn Heleos II. |

| LCST Measurement System | Accurately determines thermal transition of smart polymers. | UV-Vis spectrometer with temperature control. |

| Automated Peptide/Polymer Synthesizer | Enables generation of sequence libraries for SSP datasets. | Biotage Initiator+ Alstra. |

| Curation Software & Databases | Manages experimental data for AI training (FAIR principles). | PolyInfo Database; custom SQL/NoSQL platforms. |

This case study is situated within a broader thesis on the application of Artificial Intelligence (AI) for multi-scale polymer structure prediction. The central challenge in designing advanced polymers for biomedical applications lies in accurately modeling the relationship between monomeric sequences, processing conditions, hierarchical structure (from Angstroms to microns), material properties, and in vivo performance. Traditional design relies on iterative, empirical experimentation, which is prohibitively slow and costly. AI, particularly machine learning (ML) and molecular dynamics (MD) enhanced by neural networks, offers a paradigm shift. By learning from existing experimental and simulation data, AI models can predict the self-assembly behavior, degradation profiles, drug encapsulation efficiency, and biocompatibility of novel polymer architectures before synthesis, thereby dramatically accelerating the design cycle from years to months.

Core AI Methodologies for Polymer Prediction

Data-Driven Property Prediction

Recent advances utilize graph neural networks (GNNs) to represent polymer repeat units as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges. These models are trained on curated datasets like Polymer Genome to predict key properties.

Table 1: AI Model Performance on Key Polymer Property Predictions

| Target Property | AI Model Type | Dataset Size | Reported Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Key Reference (2023-2024) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glass Transition Temp (Tg) | Attentive FP GNN | ~12k polymers | < 15°C | Guo et al., npj Comput Mater, 2023 |

| LogP (Hydrophobicity) | Directed Message Passing NN | ~10k polymers | 0.35 | Wu et al., Sci Data, 2024 |

| Degradation Rate (Relative) | CNN on SMILES Strings | ~2k biodegradable polymers | 0.12 (Normalized RMSE) | Patel et al., Biomacromolecules, 2023 |

| Critical Micelle Concentration | Multimodal GNN | ~800 amphiphilic copolymers | 0.20 log(mM) | Zhang & Li, ACS Appl Mater Interfaces, 2024 |

Experimental Protocol for Generating Training Data (Degradation Rate):

- Polymer Library Synthesis: A diverse set of biodegradable polyesters (e.g., PLGA, PCL variants) are synthesized via ring-opening polymerization with controlled molecular weights (5-50 kDa) using a high-throughput automated synthesizer.

- In Vitro Degradation Study: Polymers are processed into thin films (100 µm thickness) via spin-coating. Films (n=6 per polymer) are immersed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) at 37°C with gentle agitation.

- Time-Point Sampling: At predetermined intervals (e.g., 1, 7, 14, 28, 56 days), samples are removed, rinsed, and dried to constant weight.

- Data Acquisition: Mass loss (%) is measured gravimetrically. Molecular weight loss is quantified via gel permeation chromatography (GPC). The time to 50% mass loss (t½) is calculated and log-transformed to create the target 'degradation rate' label for ML training.

Generative AI for de novo Polymer Design

Inverse design models, such as variational autoencoders (VAEs) or generative adversarial networks (GANs), are trained to generate novel polymer structures that satisfy a set of target property constraints (e.g., high drug loading, specific release profile).

Table 2: Generated Polymer Candidates for Doxorubicin Delivery (2024 Simulation Study)

| Generated Polymer ID | Architecture (AI-Proposed) | Predicted Dox Loading (%) | Predicted Burst Release (24h) | Predicted Cytocompatibility (Viability %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gen-Poly-01 | PEG-b-Poly(caprolactone-co-trimethylene carbonate) | 18.5 ± 2.1 | < 10% | 92.3 |

| Gen-Poly-47 | Hyperbranched Polyglycerol-PLA dendrimer | 22.7 ± 3.0 | < 5% | 88.7 |

| Gen-Poly-89 | Linear Poly(β-amino ester) with imidazole side chain | 15.8 ± 1.8 | 35% (pH-sensitive) | 85.1 |

Integrated AI-Experimental Workflow

Diagram 1: AI-driven polymer design and testing pipeline

Key Experimental Protocol: AI-Guided Nanoparticle Formulation & Testing

This protocol details the validation of an AI-predicted copolymer for mRNA delivery.

Title: Validation of AI-Designed Polymeric Nanoparticles

Materials & Reagent Solutions:

- AI-Identified Lead Polymer: A triblock copolymer of poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly((diethylamino)ethyl methacrylate)-block-poly(butyl methacrylate) (PEG-PDEAEMA-PBMA), predicted to have high mRNA complexation and endosomal escape potential.

- mRNA: EGFP-encoding mRNA, purified, capped, and polyadenylated.

- Microfluidic Mixer: A staggered herringbone nanoprecipitation chip.

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) / Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): For size and PDI measurement.

- HEK-293T Cells: For in vitro transfection.

- Flow Cytometry Buffer: PBS with 1% BSA.

Procedure:

- Nanoparticle Formulation: Prepare separate solutions of polymer in anhydrous DMSO (10 mg/mL) and mRNA in citrate buffer (pH 4.0, 50 µg/mL). Load solutions into separate syringes, connect to a microfluidic chip, and mix at a controlled total flow rate (10 mL/min) and polymer-to-mRNA ratio (predicted optimal by AI, e.g., 20:1 w/w). Collect nanoparticles in PBS.