Amorphous vs. Semicrystalline Materials: A Thermal Properties Guide for Pharmaceutical and Material Scientists

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the thermal properties of amorphous and semicrystalline materials, crucial for researchers and drug development professionals.

Amorphous vs. Semicrystalline Materials: A Thermal Properties Guide for Pharmaceutical and Material Scientists

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the thermal properties of amorphous and semicrystalline materials, crucial for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental principles governing molecular mobility, crystallization behavior, and their direct impact on material performance. The scope spans from foundational concepts and advanced characterization methodologies to practical application guidelines, troubleshooting common issues, and validating material performance through comparative analysis. By synthesizing recent research findings, this review serves as a strategic resource for optimizing material selection and processing parameters in pharmaceutical formulation and advanced material design, with particular emphasis on thermal stability, conductivity, and mechanical behavior.

Molecular Origins: Unraveling the Fundamental Thermal Behavior of Amorphous and Semicrystalline Structures

The performance and properties of thermoplastics are fundamentally governed by their internal molecular architecture. Polymers are broadly categorized into two distinct classes based on this architecture: amorphous and semicrystalline [1]. This division is not merely academic; it dictates every aspect of a polymer's behavior, from its thermal response and mechanical strength to its optical characteristics and chemical resistance [2] [3]. Understanding this molecular-level structural order is crucial for researchers and scientists, particularly in advanced fields like drug development, where material selection can influence device performance, drug stability, and release profiles.

The core distinction lies in the arrangement of the polymer chains. Amorphous polymers exhibit a random, entangled structure, often compared to a plate of cooked spaghetti, lacking any long-range order [2] [3]. In contrast, semicrystalline polymers feature a hybrid structure, with organized, tightly packed crystalline regions—called spherulites—embedded within a disordered amorphous matrix [2]. This fundamental architectural difference is the origin of their divergent properties and processing behaviors, a relationship that forms the thesis of this analysis within the broader context of thermal properties research.

Molecular Architecture: A Tale of Two Structures

The Amorphous Phase

In the amorphous phase, polymer chains are arranged in a random, coiled, and entangled manner without any long-range order [3]. This disorganized structure lacks a sharp melting point. Instead, when heated, amorphous polymers gradually soften over a range of temperatures as the material transitions from a hard, glassy state to a soft, rubbery state, and eventually to a viscous liquid [4] [5]. This transition point is known as the glass transition temperature (Tg) [4]. The isotropic nature of the molecular structure means these materials shrink uniformly in all directions during cooling, leading to better dimensional stability and less warpage [6] [2]. The random molecular arrangement also allows light to pass through with less scattering, which is why amorphous polymers are often transparent [3].

The Semicrystalline Phase

Semicrystalline polymers possess a dual-phase structure characterized by organized, tightly packed crystalline areas interspersed with unordered amorphous regions [2] [4]. The crystalline regions, or crystallites, are areas where the polymer chains are folded and aligned in an orderly pattern, creating a highly organized molecular structure [5]. This structured architecture results in a defined melting point (Tm), where the material transitions rapidly from a solid to a low-viscosity liquid upon absorbing a specific amount of heat [1] [3]. The crystalline structure scatters light, typically rendering these materials opaque or translucent [3]. Their flow is anisotropic, meaning they experience non-uniform shrinkage—less in the direction of flow and more in the transverse direction—which can lead to dimensional instability during processing [1] [5].

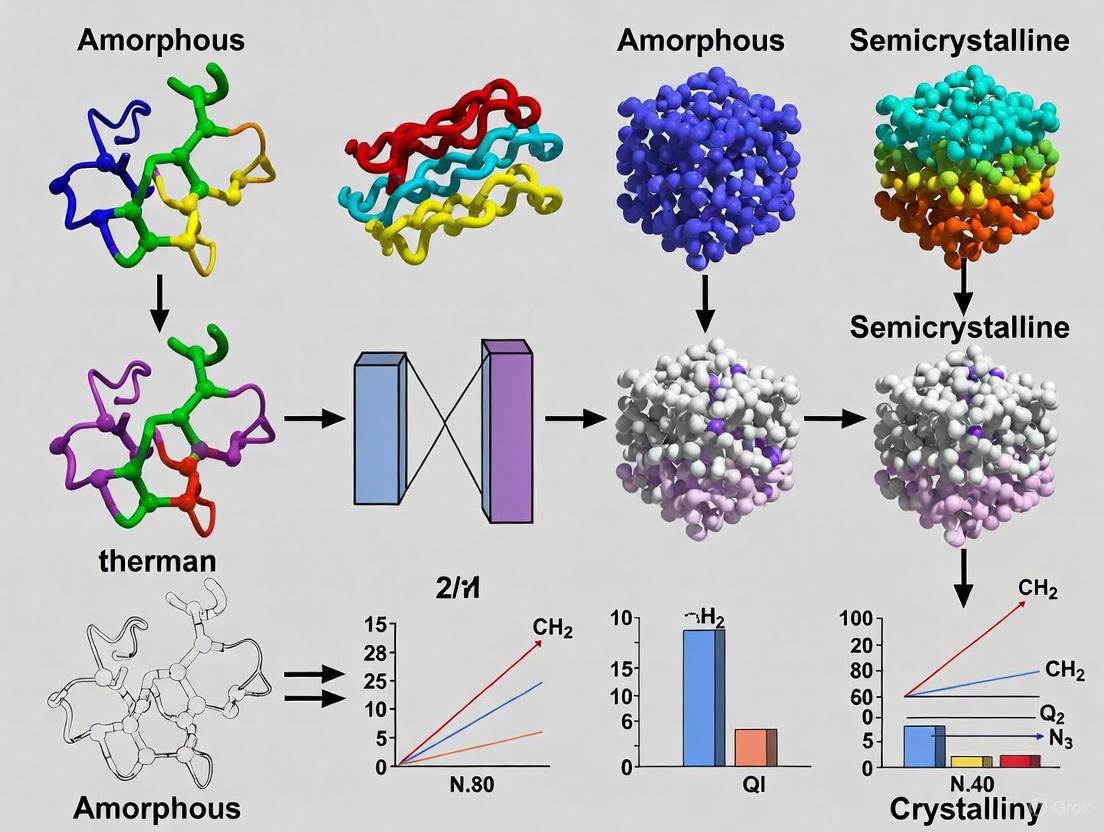

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental architectural differences between these two polymer phases and their direct link to material properties.

Figure 1: Molecular Architecture and Resulting Properties of Polymer Phases

Comparative Analysis of Key Properties

The architectural differences between amorphous and semicrystalline polymers manifest in distinct property profiles, which are critical for material selection in research and development applications.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Amorphous and Semicrystalline Polymers

| Property | Amorphous Polymers | Semicrystalline Polymers |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Structure | Random, coiled, entangled chains [2] [3] | Organized crystalline regions in amorphous matrix [2] [4] |

| Melting Behavior | Gradual softening over a temperature range; no sharp melting point [3] [4] | Sharp melting point at a specific temperature [1] [3] |

| Optical Clarity | Often transparent or translucent [3] | Usually opaque or translucent [3] |

| Density | Higher density polymers [3] | Lower density polymers [3] |

| Chemical Resistance | Generally lower chemical resistance [3] [5] | Excellent chemical resistance [3] [5] |

| Shrinkage & Warpage | Isotropic shrinkage; lower warpage [6] [2] | Anisotropic shrinkage; higher warpage [6] [5] |

| Mechanical Properties | High impact resistance, poor fatigue resistance [2] [3] | Good strength & wear resistance, lower impact resistance [2] [5] |

| Thermoforming | Easier to thermoform [2] | Difficult to thermoform [3] |

Thermal and Mechanical Performance

The thermal behavior of these polymer classes extends beyond melting characteristics. Amorphous polymers, such as polycarbonate (PC) and polysulfone (PSU), typically exhibit superior impact resistance and bond well to substrates, making them suitable for structural applications and environments with mechanical shock [1] [3]. However, they are more prone to stress cracking and offer poor fatigue resistance [2]. Their glass transition temperature (Tg) is a critical parameter, representing the transition from a glassy to a rubbery state [4].

Semicrystalline polymers, including polyamide (PA) and polypropylene (PP), form tough plastics with excellent resistance to wear, bearings, and structural loads [3]. They maintain good stiffness and strength, with a very low coefficient of friction, but their impact resistance is generally inferior to amorphous polymers [3] [5]. The degree of crystallinity is a key variable that influences many material characteristics and can be controlled through processing conditions and thermal history [6].

Experimental Data and Research Findings

Mould Material Interaction Study

A significant study investigating the interaction between polymer type and mould material revealed substantial differences in production efficiency and part quality. The research employed steel and aluminium mould cavities to process different polymers, assessing critical injection parameters for a high-production automotive component (cup holder) [6].

Table 2: Cycle Time Reduction in Aluminium Moulds vs. Steel Moulds [6]

| Polymer Type | Specific Material | Cycle Time Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Semicrystalline | Polypropylene (PP) | 40.6% to 52.5% |

| Semicrystalline | Polyamide (PA) | 56% to 63.5% |

| Amorphous | Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS) | Less significant reductions compared to semicrystalline materials |

The study concluded that for productivity factors, moulds made of aluminium using semicrystalline polymers showed more significant reductions in cycle time compared to amorphous materials [6]. Furthermore, regarding warpage, amorphous materials displayed the lowest values for both types of moulds, but aluminium moulds exhibited the lowest warping results and smaller variations for all polymers [6].

Experimental Protocol: Taguchi Method and Simulation

The experimental methodology for this comparative study utilized a structured approach to ensure statistical significance and practical relevance [6].

1. Experimental Planning: The Taguchi experimental planning method was employed as a fractionated factorial approach. This "off-line quality control" method involves a small number of samples from trial phases, which present high variance levels in quality parameters compared to production parts. This technique allows for the determination of the optimum combination of factors and interactions that influence variable-response behavior with fewer samples and decreased testing costs without affecting the conclusions [6].

2. Numerical Simulation: Numerical simulations were performed using MoldFlow 2024 software to analyze the injection molding process for different polymer types (ABS and PC for amorphous; PP and PA for semicrystalline) in both steel and aluminium moulds. The simulations assessed key parameters including cycle time, warpage, and cooling efficiency [6].

3. Statistical Analysis: Statistical tests were conducted using Minitab 19 software. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was applied to the numerical simulation results to identify the most important parameters for each response variable. The statistical variables used to assess the results included the R² value, P-value, and the intrinsic error of the model [6].

The following workflow diagram outlines the experimental methodology used in the cited study.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Polymer Processing Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Analytical Methods for Polymer Research

| Item/Reagent | Function/Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Polymer Grades (ABS, PC, PP, PA) | Base materials for comparative studies of amorphous vs. semicrystalline structures; selected for differences in mechanical and physical properties [6]. |

| Mould Materials (Steel, Aluminium) | Cavity materials for injection moulding studies; aluminium with superior thermal conductivity (up to 5x greater than steel) reduces cycle times significantly [6]. |

| Thermal Stabilizers & Antioxidants | Additives to improve thermal behavior and oxidative stability of polymers during processing and in service [4]. |

| Fillers (Glass Fiber, Ceramic Powder) | Enhance thermal resistance and mechanical properties; glass fiber increases stiffness while potentially reducing impact strength [4]. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Analytical technique to determine glass transition temperature (Tg), melting point (Tm), and degree of crystallinity. |

| Taguchi Experimental Design | Statistical method for optimizing process parameters with minimal experimental runs; identifies key factors influencing output variables [6]. |

| ANOVA Statistical Analysis | Identifies most significant parameters affecting response variables; validates experimental results through R², P-value, and intrinsic error analysis [6]. |

The molecular architecture of polymers—whether amorphous or semicrystalline—serves as the fundamental determinant of their thermal, mechanical, and processing characteristics. The experimental data confirms that semicrystalline polymers like polyamide and polypropylene exhibit significantly greater cycle time reductions (up to 63.5%) when processed in high-thermal-conductivity aluminium moulds compared to amorphous materials [6]. This has substantial implications for manufacturing efficiency in high-volume production environments, such as automotive components.

For researchers and drug development professionals, this architectural understanding provides a predictive framework for material selection. Amorphous polymers, with their isotropic behavior, dimensional stability, and transparency, are advantageous for applications requiring precise dimensions and optical clarity [1] [3]. Conversely, semicrystalline polymers offer superior chemical resistance, wear performance, and structural integrity for components subjected to mechanical stress and harsh environments [3] [5]. The choice between these two fundamental architectural forms ultimately depends on the specific performance requirements, environmental conditions, and processing constraints of the intended application, with the structural order at the molecular level dictating macroscopic performance.

Understanding the thermal transition behavior of polymers is fundamental to materials science, dictating the processing, performance, and end-use applications of everything from commodity plastics to advanced pharmaceutical formulations. Within this context, two transitions are paramount: the glass transition (Tg) and the melting point (Tm). The glass transition is a phenomenon of the amorphous regions in a polymer, marking the temperature at which chains gain sufficient mobility to transition from a hard, glassy state to a soft, rubbery one [7]. In contrast, the melting point is a first-order transition characteristic of the crystalline regions, where well-ordered structures break down into a disordered melt [7]. For researchers and scientists, accurately characterizing these transitions is not merely academic; it is crucial for predicting material stability, mechanical integrity, and solubility, which in turn informs quality control, formulation development, and regulatory compliance [7] [8]. This guide objectively compares these behaviors across different polymer states and details the experimental protocols essential for their study.

Fundamental Concepts: Amorphous vs. Semi-Crystalline Polymers

The thermal behavior of a polymer is intrinsically linked to its microstructure. Polymers are broadly classified based on the arrangement of their molecular chains, which directly influences their thermal and mechanical properties.

- Amorphous Polymers: These polymers possess a random, disordered molecular structure, much like a plate of spaghetti. The chains are physically entangled but lack long-range order. This structure creates more free volume, allowing chains to move at lower temperatures and resulting in a lower Tg [7]. They do not have a true melting point; instead, they gradually soften upon heating. Common examples include polystyrene (PS), poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), and atactic polyvinyl chloride (PVC) [7].

- Semi-Crystalline Polymers: These materials feature a heterogeneous structure containing both ordered crystalline regions and disordered amorphous regions. The crystalline regions are held together by strong, organized molecular interactions, giving the polymer a defined melting point (Tm). The amorphous regions, interspersed between the crystalline domains, are responsible for the glass transition [7]. The crystalline structures restrict chain mobility, leading to a higher Tg compared to a purely amorphous polymer of the same chemistry. Polyethylene (PE) and poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) are classic examples [9] [7].

Table 1: Comparison of Amorphous and Semi-Crystalline Polymer Characteristics

| Characteristic | Amorphous Polymers | Semi-Crystalline Polymers |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Structure | Random, disordered | Mixture of ordered (crystalline) and disordered (amorphous) regions |

| Glass Transition (Tg) | A defining property; lower due to more free volume | Property of the amorphous parts; higher due to restricted mobility from crystals |

| Melting Point (Tm) | Does not have a sharp Tm; softens over a range | Has a sharp, defined Tm due to crystalline regions |

| General Transparency | Often transparent | Often opaque or translucent |

| Mechanical Properties | Hard and brittle below Tg; soft and flexible above Tg | Tough, and combine strength with some flexibility |

Comparative Thermal Transition Data

The following tables provide characteristic transition temperatures for a selection of common polymers, offering a reference point for researchers comparing material properties.

Table 2: Glass Transition Temperatures (Tg) of Selected Polymers [7]

| Polymer Name | Min Tg (°C) | Max Tg (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| ABS - Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene | 90.0 | 102.0 |

| Polycarbonate (PC) | 145.0 | 150.0 |

| Polystyrene (PS), General Purpose | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) | 105.0 | 105.0 |

| Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) | 75.0 | 85.0 |

| Cellulose Acetate (CA) | 100.0 | 130.0 |

| Polyisobutylene (PIB) | -70.0 | -50.0 |

Table 3: Thermal Properties of Semi-Crystalline Polymers from Experimental Studies

| Polymer Name | Melting Point (Tm) °C | Glass Transition (Tg) °C | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) | 59 - 64 [9] | -60 [9] | Bulk polymer, studied via Spectral Reflectance [9] |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) | 64 - 66 [9] | -65 [9] | Bulk polymer, studied via Spectral Reflectance [9] |

| Polyethylene (PE) | ~120 - 130 | -125 | N/A (for comparison) |

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | ~150 - 180 | ~55 - 60 | N/A (for comparison) |

Factors Influencing Transition Temperatures

A polymer's Tg and Tm are not fixed material constants but are influenced by its chemical structure and external conditions. Key factors include:

- Molecular Weight: In straight-chain polymers, increasing molecular weight decreases the concentration of chain ends, which are sites of increased free volume. This reduction in free volume restricts chain mobility, leading to an increase in Tg. This dependence is strong in the oligomeric regime but typically plateaus at higher molecular weights [10] [7].

- Chemical Structure and Plasticizers: The presence of bulky side groups or polar groups increases the energy required for chain motion, thereby raising the Tg. Conversely, adding small molecule plasticizers increases the free volume between polymer chains, allowing them to slide past each other more easily and significantly depressing the Tg [7]. Similarly, absorbed water can act as a plasticizer for some polymers, reducing Tg [7].

- Cross-Linking and Crystallinity: Chemical cross-links tightly bind polymer chains together, drastically reducing their mobility and resulting in a higher Tg [7]. In semi-crystalline polymers, the crystalline regions act as physical cross-links, similarly restricting the motion of amorphous chains and elevating the observed Tg.

- Thermal History and Processing: The thermal history of a polymer, such as its cooling rate from the melt or annealing treatments, can affect the free volume and degree of crystallinity, thereby influencing the measured Tg and Tm.

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Transitions

A range of sophisticated techniques is available for characterizing thermal transitions, each with unique strengths and applications.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Methodology Overview: DSC is a thermo-analytical technique that measures the difference in heat flow between a sample and an inert reference as they are subjected to a controlled temperature program [11] [12]. When the sample undergoes a thermal transition (e.g., glass transition, melting, or crystallization), it will absorb or release more heat than the reference, resulting in a peak or a step change in the heat flow curve [8] [12].

Protocol for Tg and Tm:

- Sample Preparation: Encapsulate 1-10 mg of the polymer in a hermetic aluminum crucible [11] [12].

- Experimental Run: Heat the sample and reference at a constant rate (e.g., 10°C/min) over a temperature range that spans the expected transition(s) under an inert nitrogen atmosphere [12].

- Data Analysis:

Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

Methodology Overview: DMA applies a small oscillatory stress to a sample and measures the resulting strain, determining the viscoelastic storage modulus (E' or G'), loss modulus (E" or G"), and tan(δ) (the damping factor) as functions of temperature, time, or frequency [13]. This technique is exceptionally sensitive to the glass transition.

Protocol for Tg:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a sample of defined geometry (e.g., a rectangular bar or a thin film) compatible with the clamping system (e.g., tension, bending, or shear) [13].

- Experimental Run: Ramp the temperature at a controlled rate (e.g., 2°C/min) while applying a small oscillatory deformation at a fixed frequency [13].

- Data Analysis: The Tg can be identified through three methods (see Diagram 1):

- Onset of E' Drop: The temperature at which the storage modulus begins to decrease sharply.

- Peak of E" (Loss Modulus): The temperature at which the loss modulus reaches a maximum.

- Peak of Tan(δ): The temperature at which the tan(δ) curve peaks. This typically gives the highest Tg value of the three methods [13].

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Methodology Overview: TGA measures the mass change of a sample as a function of temperature or time in a controlled atmosphere [11] [12]. While it does not directly measure Tg or Tm, it is crucial for determining the thermal stability of a polymer and identifying decomposition temperatures, which defines the upper temperature limit for processing and application [12].

Protocol for Thermal Stability:

- Sample Preparation: Place 5-30 mg of powder or a small solid piece into an open alumina crucible [11] [12].

- Experimental Run: Heat the sample at a constant rate (e.g., 20°C/min) from room temperature to beyond its decomposition point (e.g., 800°C) under nitrogen (for stability) or air (for oxidative stability) [12].

- Data Analysis: The onset of a mass loss step in the resulting thermogram indicates the start of decomposition or the loss of volatiles (e.g., moisture or solvent) [12].

Supplementary Techniques

- Spectral Reflectance: An emerging technique for thin films that measures thickness changes due to thermal expansion during melting or contraction during crystallization. It is beneficial for in-situ studies of substrate-supported films where traditional calorimetry is challenging [9].

- Thermomechanical Analysis (TMA): Measures dimensional changes (thermal expansion) in a material as a function of temperature, providing complementary data on Tg and coefficient of thermal expansion [8].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for key thermal analysis techniques and their primary outputs for identifying Tg and Tm.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Materials and Reagents for Polymer Thermal Studies

| Item Name | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Hermetic Aluminum Crucibles | Standard sealed pans for DSC to contain sample and prevent vaporization during heating. |

| Nitrogen Gas (High Purity) | Inert purge gas for DSC and TGA to prevent oxidative degradation during analysis. |

| Reference Materials (e.g., Indium, Zinc) | Calibration standards for temperature and enthalpy in DSC. |

| Polymer Standards (e.g., PS, PCL) | Well-characterized polymers with known Tg/Tm for method validation and instrument calibration. |

| Spin Coater & Solvents (e.g., Toluene) | For preparing thin-film polymer samples on silicon wafers for techniques like Spectral Reflectance [9]. |

Advanced Research: Thermal Transport in Amorphous Polymers

Understanding thermal transitions extends to how heat is transported through polymeric materials. Recent research using lattice dynamics and Green-Kubo Mode Analysis (GKMA) has revealed that thermal conductivity in amorphous polymers is dominated by localized modes (locons), contrary to the common picture of heat transport in other amorphous materials [14]. These locons, which involve vibrations highly concentrated on a subset of atoms, account for over 90% of the vibrational modes and contribute to over 80% of the thermal conductivity in systems like amorphous polystyrene (PS) and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) [14]. This finding provides a molecular-level explanation for the generally low thermal conductivity of polymers and suggests that engineering inter-chain interactions, rather than just intra-chain structure, could be a pathway to controlling thermal properties [14].

The demystification of glass transition and melting behavior is central to the rational design and application of polymeric materials. As detailed in this guide, the fundamental difference between amorphous and semi-crystalline structures dictates distinct thermal profiles, which can be precisely characterized using a suite of complementary techniques like DSC, DMA, and TGA. For researchers in fields from drug development to advanced materials, a rigorous understanding of these transitions—and the factors that influence them—provides the critical insights needed to ensure material stability, optimize processing conditions, and ultimately, guarantee product performance.

The investigation of molecular mobility in amorphous and semi-crystalline materials represents a critical frontier in pharmaceutical science and material engineering. Understanding cooperative relaxation dynamics is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for predicting stability, performance, and bioavailability of pharmaceutical formulations. Thermally Stimulated Current (TSC) spectrometry has emerged as a powerful technique for probing these molecular motions with exceptional sensitivity, offering insights that often remain obscured by conventional analytical methods [15].

This technique operates at a low equivalent frequency, granting it superior resolution for detecting molecular relaxation processes compared to more common approaches like dielectric spectroscopy [16]. For pharmaceutical researchers and scientists, TSC provides a unique window into the solid-state behavior of both active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and excipients, enabling more informed decisions in drug development and formulation design. The following analysis compares TSC spectrometry with alternative methodologies, provides detailed experimental protocols, and contextualizes findings within the broader framework of amorphous and semi-crystalline thermal properties research.

Fundamental Principles of TSC Spectrometry

Theoretical Basis of TSC

Thermally Stimulated Current spectrometry is a dielectric technique that measures the depolarization currents released by a material as it is heated through its molecular relaxation transitions. The fundamental principle relies on the polarization and subsequent depolarization of molecular dipoles under controlled thermal conditions. When a material contains polar groups or molecules with dipole moments, these can be aligned by applying an electric field at an elevated temperature where molecular mobility is sufficient. Upon cooling while maintaining the field, these dipoles become "frozen" in their aligned state. During subsequent heating in the absence of the field, the dipoles gain thermal energy and return to their random orientations, generating a measurable current at characteristic temperatures [15].

The relaxation time (τ) describes the time required for a specific molecular motion to be completed and is temperature-dependent, typically following an Arrhenius relationship: τ(T) = τ₀ exp(Eₐ/kT) where τ₀ is the pre-exponential factor, Eₐ is the activation energy, k is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the absolute temperature [15]. TSC excels in accurately determining these parameters without extrapolation or assumptions required by other techniques.

Classification of Molecular Relaxations

TSC spectroscopy distinguishes between two primary types of molecular relaxations:

Non-cooperative relaxations (e.g., β-relaxations): These involve independent motions of specific molecular segments, side groups, or chain ends without coordinated movement. They typically occur at lower temperatures and exhibit lower activation energies. For instance, in hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC) films, a β-relaxation detected at -57±2°C originates from independent orientation of short sections of the HEC polymer chain ends and the hydroxyethyl side groups [16].

Cooperative relaxations (e.g., α-relaxations, glass transitions): These require coordinated movement of larger molecular domains and are characterized by higher activation energies and temperatures. The glass transition (T𝑔) represents a primary cooperative process where significant segments of polymer chains gain mobility [16]. These cooperative processes follow a compensation law characteristic of highly coordinated relaxation mechanisms [17].

Table 1: Characteristics of Molecular Relaxation Processes Detectable by TSC

| Relaxation Type | Molecular Origin | Typical Temperature Range | Activation Energy | Pharmaceutical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-cooperative (β) | Localized side group motions, chain end movements | Below ambient temperatures | Low (often < 100 kJ/mol) | Precursor to larger motions, may indicate stability issues |

| Cooperative (α) | Segmental backbone mobility, glass transition | Ambient to elevated temperatures | High (often > 100 kJ/mol) | Directly related to physical stability, crystallization tendency |

| Crystalline Defects | Motions within crystal imperfections | Variable, often near melting point | Medium to High | Affects polymorphic stability, dissolution behavior |

| Solid-Solid Transitions | Molecular rearrangements between polymorphs | Transition-specific | High | Impacts polymorphic form stability and interconversion |

Comparative Analytical Techniques

TSC Versus Conventional Thermal Analysis

When selecting characterization techniques for amorphous and semi-crystalline materials, researchers must consider the complementary strengths and limitations of each method. The following comparison highlights how TSC spectrometry complements and extends capabilities beyond conventional thermal analysis techniques.

Table 2: Comparison of TSC with Other Analytical Techniques for Molecular Mobility Assessment

| Technique | Detection Principle | Effective Frequency | Key Strengths | Principal Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSC Spectrometry | Depolarization current during controlled heating | Very low (~0.001-0.1 Hz) | High resolution of overlapping transitions; Direct calculation of activation energies; Extreme sensitivity (10⁻¹⁶ A) | Requires polarizable samples; Less established in pharma; Limited to solid-state characterization |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Heat flow difference during temperature programming | Medium (~0.01-0.1 Hz) | Widely available; Standardized protocols; Provides thermodynamic data (ΔH, T𝑔) | Lower resolution for broad transitions; Limited sensitivity for weak relaxations; Indirect mobility assessment |

| Dielectric Spectroscopy (DS) | AC current response to oscillating electric field | Broad (10⁻⁵-10¹⁰ Hz) | Broad frequency range; Well-established theory; Commercial availability | Overlapping relaxations difficult to deconvolute; Requires conductive electrodes; Complex data interpretation |

| Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) | Mechanical response to oscillatory stress | 0.01-100 Hz | Sensitive to glass transitions; Measures viscoelastic properties; Standard method for mechanical relaxations | Limited to self-supporting samples; Potential for mechanical damage; Complex sample preparation |

Unique Advantages of TSC in Pharmaceutical Research

TSC spectrometry offers several distinctive advantages for pharmaceutical applications:

Enhanced Sensitivity to Amorphous Content: TSC directly probes molecular mobility, making it exceptionally sensitive to amorphous phases in predominantly crystalline matrices. Studies have demonstrated detection limits as low as 2.5% amorphous content in crystalline irbesartan, with potential for further optimization of experimental parameters [17].

Superior Resolution of Complex Transitions: The low equivalent frequency of TSC enables clear separation of overlapping relaxation processes. For instance, TSC identified two distinct glass transitions in polyethyleneglycols (PEGs) that appeared as weak, unresolved events in MTDSC [15]. The transitions, separated by 10-15°C, provided insights into different amorphous regions within the semi-crystalline polymer.

Early Detection of Instability: Molecular mobilities detectable by TSC often precede major transitions observed by other techniques. Research on indomethacin revealed significant molecular mobility 20°C below the conventionally measured T𝑔, explaining its tendency to crystallize just below the glass transition [15]. This early warning capability is crucial for predicting stability issues in amorphous pharmaceuticals.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard TSC Experimental Procedure

The following protocol outlines the fundamental TSC measurement process, synthesized from multiple methodological descriptions in the search results [18] [16] [15]:

Sample Preparation:

- For pharmaceutical powders: Compress into pellets (typically 1-3 mm thick) using a hydraulic press.

- For polymers: Prepare free-standing films (typically 100-500 µm thick) by solvent casting or compression molding.

- Ensure good contact with electrodes by applying conductive coatings (gold or silver) if necessary.

Sample Polarization:

- Heat the sample to the initial polarization temperature (T𝑝), typically slightly above the relaxation of interest.

- Apply a DC electric field (typically 100-500 V/mm) for a sufficient time (usually 2-5 minutes) to allow dipole alignment.

Freezing Dipolar Orientations:

- Cool the sample to a cryogenic temperature (typically -150°C to -100°C) while maintaining the electric field.

- This "freezes" the aligned dipoles in their non-equilibrium state.

Depolarization Current Measurement:

- Remove the electric field and heat the sample at a constant rate (typically 5-10°C/min).

- Measure the resulting depolarization current using a highly sensitive electrometer (capable of detecting currents as low as 10⁻¹⁶ A).

Data Analysis:

- Identify relaxation peaks in the global TSC spectrum.

- Calculate activation parameters (Eₐ, τ₀) for each relaxation process.

Figure 1: TSC Experimental Workflow. The diagram illustrates the sequential steps in a standard TSC measurement protocol.

Thermal Windowing Procedure

For complex relaxation processes like the glass transition, TSC employs a "thermal windowing" or "fractional polarization" technique to deconvolute overlapping processes:

Global Spectrum Acquisition: First, obtain a standard TSC spectrum to identify temperature regions of interest.

Selective Polarization:

- Polarize the sample at a specific temperature (T𝑝) within the relaxation region of interest.

- Immediately cool the sample by 3-10°C (temperature window) before proceeding with standard cooling.

Multiple Window Acquisition: Repeat step 2 across the entire temperature range of the complex relaxation using overlapping windows.

Data Reconstruction: Analyze the set of elementary peaks to determine the distribution of relaxation times and activation parameters across the transition [15].

This approach enables researchers to extract detailed information about the heterogeneity of molecular mobility within what appears as a single broad transition in other techniques.

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Successful TSC analysis requires specific materials and instrumentation. The following table catalogs essential research reagents and their functions in TSC experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for TSC Experiments

| Material/Reagent | Specifications | Function in TSC Analysis | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | High-purity indomethacin, caffeine polymorphs | Method validation and calibration | Verifying instrument response; Quantifying amorphous content [15] |

| Electrode Coatings | Conductive silver or gold paste | Ensuring electrical contact with sample | Creating uniform electric field across sample; Minimizing air gaps [16] |

| Pharmaceutical Polymers | HEC, PEG, HPMC of various molecular weights | Model systems for method development | Studying molecular weight effects on mobility; Excipient characterization [16] [15] |

| Cryogenic Fluids | Liquid nitrogen or helium | Sample cooling to cryogenic temperatures | Freezing molecular motions; Enabling low-temperature polarization |

| Standard Solvents | HPLC-grade water, organic solvents | Sample preparation (film casting, cleaning) | Creating uniform films; Removing contaminants before analysis [16] |

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

Characterization of Amorphous Pharmaceutical Systems

TSC spectrometry provides critical insights into amorphous pharmaceutical materials, which are increasingly utilized to enhance solubility and bioavailability of poorly soluble APIs. The technique's exceptional sensitivity to molecular mobility makes it ideal for:

Stability Assessment: The breadth of the TSC glass transition signal (typically 20-30°C for indomethacin) compared to the narrower DSC transition (approximately 5°C) reveals that molecular rearrangements begin at temperatures significantly below the conventional T𝑔 [15]. This finding validates the empirical pharmaceutical practice of storing amorphous materials at least 50°C below their T𝑔 to minimize crystallization.

Homogeneity Evaluation: The relationship between pre-exponential factors (τ₀) and activation energies (Eₐ) across a relaxation reveals the homogeneity of amorphous systems. Linear compensation behavior indicates a homogeneous amorphous phase, while non-linear relationships suggest heterogeneity that could impact stability and performance [15].

Quantification of Amorphous Content: TSC can detect and quantify low levels of amorphous content in predominantly crystalline materials. For irbesartan, a calibration curve enabled quantification with a detection limit of 2.5% amorphous content [17]. This sensitivity makes TSC valuable for monitoring process-induced amorphization during manufacturing.

Analysis of Semi-Crystalline and Polymorphic Systems

In semi-crystalline pharmaceuticals, TSC provides unique insights into the complex interplay between ordered and disordered regions:

Polymorphic Characterization: TSC can distinguish between polymorphic forms based on their distinct molecular mobilities. For caffeine Forms I and II, TSC revealed previously unknown relaxation processes responsible for molecular rearrangements prior to the main solid-solid transition [15].

Crystalline Defect Analysis: Different crystalline forms exhibit distinct TSC responses based on their internal mobility. While the B form of irbesartan showed no specific dielectric response, the A form displayed molecular motions localized within its channel structure, demonstrating how crystal packing influences molecular mobility [18] [17].

Semi-Crystalline Complexity: TSC studies support the view that semi-crystalline pharmaceuticals should not be considered as simple two-phase systems. Research on recrystallized irbesartan samples revealed complex behavior explainable by either an "idealized one-state model" (independent amorphous and crystalline phases) or classical one-state model, depending on thermal history [17].

Figure 2: TSC Pharmaceutical Application Domains. The diagram categorizes major application areas for TSC spectrometry in pharmaceutical research.

Thermally Stimulated Current spectrometry represents a powerful, albeit underutilized, technique for characterizing molecular mobility in pharmaceutical systems. Its exceptional sensitivity to both cooperative and non-cooperative relaxation processes provides insights that complement and extend information obtained from conventional thermal analysis methods. The ability to directly probe molecular motions, quantify low levels of amorphous content, and deconvolute complex transitions makes TSC particularly valuable for understanding and predicting the stability and performance of amorphous and semi-crystalline pharmaceuticals.

As pharmaceutical development increasingly embraces amorphous solid dispersions and other metastable systems, techniques like TSC that can probe the fundamental molecular motions governing stability will become increasingly essential. The integration of TSC data with information from other analytical methods provides a comprehensive picture of solid-state behavior, enabling more rational design of robust pharmaceutical formulations with optimized performance characteristics.

The interplay between the degree of crystallinity (Xc), glass transition temperature (Tg), and storage modulus represents a fundamental relationship governing the thermomechanical behavior of semicrystalline polymers. These materials consist of an interpenetrating network of rigid crystalline lamellae and disordered amorphous regions, with the relative proportion and arrangement of these phases dictating ultimate material performance [19]. For researchers and scientists engaged in material selection for applications ranging from drug development to high-performance engineering components, understanding these structure-property relationships is essential. The crystallinity degree serves as a critical control parameter, influencing not only the stiffness and load-bearing characteristics of a polymer but also its transition temperatures and dimensional stability. This guide systematically examines the experimental evidence demonstrating how Xc modulates key thermal and mechanical properties, providing a comparative framework for predicting material behavior across different thermal environments and structural configurations.

Fundamental Concepts: Crystallinity, Tg, and Storage Modulus

In semicrystalline polymers, molecular chains fold into ordered regions called crystallites, while the remaining segments form disordered amorphous regions [20]. The degree of crystallinity (Xc) quantifies the volume or weight fraction of the crystalline phase within the material. This parameter profoundly influences material properties because crystalline and amorphous regions exhibit vastly different mechanical behaviors and thermal responses.

The glass transition temperature (Tg) marks the temperature region where the amorphous phase transitions from a hard, glassy state to a soft, rubbery state, accompanied by a sudden loss in mechanical stiffness [21]. Importantly, in semicrystalline polymers, the amorphous regions are often constrained by adjacent crystalline lamellae, which can significantly alter the Tg compared to that of a purely amorphous material [22].

The storage modulus, typically measured via dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA), represents the elastic (solid-like) response of a material and indicates its stiffness under dynamic loading conditions [19]. For semicrystalline polymers, the storage modulus demonstrates characteristic temperature dependence, reflecting the contributions of both crystalline and amorphous components. Below the Tg, amorphous regions are rigid and contribute significantly to stiffness, while above Tg, the crystalline phase primarily governs modulus retention until the melting point is approached [20].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Polymer Morphologies

| Property | Semi-crystalline Polymers | Amorphous Polymers |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Structure | Regions of ordered, patterned structure bounded by unorganized amorphous regions [20] | Unorganized, loose structure with no long-range order [20] |

| Thermal Transition | Distinct melting point (Tm) [20] | Softens above glass transition temperature (Tg) without true melting [20] |

| Mechanical Behavior vs. Temperature | Modulus stable below Tg, steady decline between Tg and Tm [20] | Relatively consistent modulus until approaching Tg, then sharp decline [20] |

Experimental Evidence: How Xc Influences Thermal and Mechanical Properties

Crystallinity and Storage Modulus Relationship

The relationship between crystallinity and storage modulus is complex and temperature-dependent, as demonstrated by systematic studies on poly(4-methyl-1-pentene) (P4M1P). Research reveals that at temperatures below the Tg, samples with lower crystallinity can exhibit a higher storage modulus. This counterintuitive behavior is attributed to the density differences between phases in P4M1P, where the amorphous phase becomes denser than the crystalline phase at lower temperatures [19]. However, as temperature increases, this relationship reverses, and the storage modulus shows a positive correlation with crystallinity at elevated temperatures [19].

The mechanical behavior of semicrystalline polymers can be conceptualized using composite theory models. At temperatures above Tg, where the amorphous phase is rubbery and compliant, the crystalline skeleton largely governs the mechanical response, making it closer to the Voigt rule of mixtures (upper bound) where components are arranged in parallel [19]:

G = αGc + (1-α)Ga

where G is the shear modulus of the bulk material, α is the crystalline volume fraction, and Gc and Ga are the shear moduli of the crystalline and amorphous phases, respectively.

Constrained Amorphous Phase and Tg Behavior

The glass transition in semicrystalline polymers does not occur in a "free" amorphous phase but rather in amorphous regions constrained by surrounding crystals. This confinement significantly stiffens the amorphous regions, with the elastic modulus of the interlamellar amorphous phase (Ea) in polyethylene reaching approximately 40 MPa—more than ten times higher than the 3 MPa modulus of the unconstrained amorphous phase [22].

This stiffening effect diminishes with increasing temperature due to the activation of α relaxation processes within the crystals, which gradually increases molecular mobility and reduces the constraining influence of the crystalline phase [22]. The thickness of the crystalline lamellae further modulates this effect; thicker crystals produce a more pronounced α relaxation shift to higher temperatures, thereby enhancing the stiffening effect on the amorphous phase [22].

Multi-Material Properties from Single Formulations

Recent advances in 3D printing demonstrate how crystallinity can be controlled to create dramatic property variations from a single monomer formulation. By manipulating printing temperature and light intensity, researchers can selectively trap a liquid crystalline monomer in either an ordered LC phase or a largely amorphous state during polymerization [23]. This approach enables pixel-to-pixel resolution of material properties, creating stiff, opaque regions alongside soft, transparent regions within a single printed part—all from an identical chemical formulation [23].

Comparative Data Analysis

Table 2: Experimental Data on Crystallinity-Property Relationships

| Polymer Material | Crystallinity Influence | Effect on Storage Modulus | Effect on Tg/Transition Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(4-methyl-1-pentene) (P4M1P) | Negative modulus dependence at low T; positive dependence at high T [19] | At 60°C: Increases with crystallinity [19] | Density crossover point at ~60°C affects mechanical behavior [19] |

| High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) | Constrained amorphous regions [22] | Amorphous phase modulus (Ea) = ~40 MPa (constrained) vs. ~3 MPa (unconstrained) [22] | α relaxation processes in crystals influence amorphous phase stiffness [22] |

| Liquid Crystalline Monomer Formulation | Controlled by printing temperature [23] | Curing from LC phase: Stiff material; Curing from isotropic phase: Soft material [23] | Optical property differentiation (opaque vs. transparent) based on phase during curing [23] |

Experimental Methodologies

Determining the Amorphous Phase Modulus (Ea)

A novel methodology for determining the elastic modulus of the amorphous phase (Ea) in semicrystalline polymers involves combining swelling agents with mechanical testing and structural characterization:

- Sample Preparation: Compression mold polymer films of specified thickness (e.g., 0.5-4 mm) [19] [22].

- Swelling Agent Application: Expose samples to swelling agents such as n-octane or n-hexane, which preferentially penetrate and deform the amorphous regions without affecting crystals [22].

- Local Strain Measurement: Use Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS) to quantify changes in the long period (lamellar stacking distance) during swelling, representing local strain in the amorphous regions [22].

- Stress Assessment: Determine the yield stress required to initiate deformation in the swollen amorphous phase [22].

- Modulus Calculation: Calculate Ea by analyzing the stress-strain relationship specific to the amorphous component [22].

This method has been successfully applied to various polyethylenes and polypropylene, revealing Ea values significantly higher than those of unconstrained amorphous phases due to the restrictive influence of the crystalline lamellae [22].

Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) Protocol

DMA provides direct measurement of the storage modulus across a temperature range:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare specimens with varying thermal histories (quenched, slow-cooled, annealed) to achieve different crystallinity levels [19].

- Temperature Ramping: Conduct tests over a defined temperature range (e.g., -25°C to 75°C) at a controlled heating rate [22].

- Frequency and Strain Control: Apply oscillatory deformation at fixed frequency and strain amplitude to measure the storage modulus [19].

- Data Analysis: Correlate modulus changes with temperature and crystallinity, identifying transitions and structure-property relationships [19].

Thermal Protocols for Crystallinity Control

Different thermal histories during processing create materials with distinct crystalline architectures:

- Quenching: Rapid cooling to room temperature or ice water produces low crystallinity with thin crystals [19].

- Slow Cooling: Gradual cooling to ambient temperature yields higher crystallinity [19].

- Annealing: Heating quenched samples below the melting point (e.g., at 150°C) increases crystallinity and perfects crystal structure [19].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Research Tools

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Swelling Agents (n-octane, n-hexane) | Selectively penetrates and deforms amorphous regions for Ea measurement [22] | Local deformation of amorphous phase in HDPE for modulus calculation [22] |

| Liquid Crystalline Monomers | "Switchable" monomers enabling property control via processing parameters [23] | Multi-material 3D printing from single formulation [23] |

| Photoinitiator Systems | Initiate photopolymerization under specific wavelength and intensity conditions [23] | Controlling network formation in vat photopolymerization [23] |

| Reference Polymers (P4M1P, HDPE, LDPE) | Model systems for studying crystallinity-property relationships [19] [22] | Fundamental studies on constrained amorphous phase [22] |

Conceptual Framework and Signaling Pathways

The relationship between crystallinity, amorphous phase confinement, and macroscopic properties follows a logical pathway that can be visualized as follows:

Crystallinity-Property Relationship Pathway

The experimental workflow for investigating these relationships integrates multiple characterization techniques:

Experimental Workflow for Property Analysis

The degree of crystallinity (Xc) exerts a profound and multi-faceted influence on the glass transition temperature and storage modulus of semicrystalline polymers. Rather than operating in isolation, Xc interacts with temperature and crystalline architecture to determine material behavior through mechanisms such as amorphous phase confinement and α relaxation processes. The experimental data and methodologies presented in this guide provide researchers with a framework for predicting and tailoring polymer properties for specific applications. Emerging techniques, such as multi-temperature 3D printing from single formulations, further demonstrate how precise control over crystallinity enables the creation of materials with spatially graded properties [23]. For scientists engaged in advanced material development, mastering these crystallinity-property relationships is essential for designing next-generation polymeric materials with optimized thermal and mechanical performance.

The Pressure-Volume-Temperature (PVT) behavior of polymers is a critical relationship that describes how their specific volume changes in response to variations in temperature and pressure. This behavior fundamentally dictates polymer processing outcomes and final product properties, particularly during cooling phases in manufacturing techniques like injection molding. The thermodynamic response of polymers during cooling diverges significantly between amorphous and semicrystalline structures, with the latter exhibiting more complex behavior due to crystallization kinetics that are heavily influenced by cooling conditions [24] [25]. Understanding these differences is essential for researchers and scientists working in material development, particularly as they relate to thermally induced stresses and dimensional stability in final products [26]. This guide provides a comprehensive experimental and theoretical comparison of how amorphous and semicrystalline polymers behave during cooling, with specific emphasis on PVT relationships and their practical implications for material selection and processing optimization.

Fundamental Differences in PVT Behavior

Thermal Transitions and Specific Volume Response

The specific volume (the inverse of density) of polymers exhibits distinct patterns for amorphous and semicrystalline materials during cooling, primarily due to differences in their molecular organization and transition behaviors:

Amorphous polymers typically display a single, relatively gradual change in slope at the glass transition temperature (Tg), where the material transitions from a rubbery to a glassy state without any abrupt volume discontinuity [27]. The specific volume curve during cooling remains largely continuous, with the primary transition occurring over a temperature range rather than at a precise point.

Semicrystalline polymers exhibit a more complex response characterized by multiple transitions. These materials display both a glass transition and a distinct melting/crystallization transition, where an abrupt change in specific volume occurs due to the first-order phase transition associated with crystallization [25] [28]. The crystallization process manifests as a significant, relatively sharp reduction in specific volume as molecular chains organize into ordered crystalline regions.

Table 1: Characteristic Transition Behaviors During Cooling

| Polymer Type | Primary Transitions | Specific Volume Change | Order of Transition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amorphous | Glass transition (Tg) | Continuous slope change | Second-order |

| Semicrystalline | Glass transition (Tg) and Crystallization (Tc) | Abrupt decrease at Tc | First-order (crystallization) |

The Influence of Cooling Rate

The cooling rate during processing exerts dramatically different effects on amorphous versus semicrystalline polymers, with the latter showing significantly greater sensitivity:

For amorphous polymers, the cooling rate primarily affects the glass transition temperature, with faster cooling resulting in a higher apparent Tg and greater nonequilibrium volume, though these effects are generally moderate in magnitude [25] [27].

For semicrystalline polymers, the cooling rate profoundly impacts both the crystallization temperature and the final degree of crystallinity. As cooling rate increases, the crystallization temperature decreases, and the ultimate crystallinity is reduced due to limited time available for molecular reorganization [25] [28]. This relationship follows a predictable pattern where both onset crystallization temperature (Ts) and maximum crystallization temperature (Tm) decrease according to the relationship: Ts = d₁ - k₁ × r^t¹ and Tm = d₂ - k₂ × r^t², where r represents the cooling rate [28].

Table 2: Cooling Rate Impact on Polymer Properties

| Cooling Rate Effect | Amorphous Polymers | Semicrystalline Polymers |

|---|---|---|

| Transition Temperature | Slight increase in Tg with cooling rate | Significant decrease in crystallization temperature with cooling rate |

| Specific Volume | Moderate increase with cooling rate | Substantial increase (lower density) with cooling rate |

| Structural Order | Minimal impact on free volume distribution | Major reduction in crystallinity degree |

Experimental Characterization of PVT Behavior

PVT Measurement Techniques

Accurately characterizing PVT behavior requires specialized instrumentation capable of controlling both pressure and temperature while precisely measuring specific volume changes. Several experimental approaches have been developed:

Confining Fluid Technique: This method utilizes a fluid (typically mercury) to transmit pressure to the polymer sample while measuring volume changes. Advanced setups can achieve cooling rates up to 60 K/s and pressures of 20 MPa, making them suitable for simulating processing conditions [26]. The apparatus measures specific volume simultaneously with temperature history and pressure application, providing comprehensive data sets for analysis.

High-Pressure Capillary Rheometer: This instrument can perform isothermal or isobaric PVT measurements according to ISO 17744 standards [28]. It employs a capillary tube with specific diameter-to-length ratios (typically 25:2) and requires precise sample mass control (approximately 3 kg for accurate results). Data points are recorded at regular temperature intervals (e.g., 2°C) during controlled cooling cycles.

Injection Molding Machine-Based Measurement: Some methodologies adapt actual injection molding equipment to measure PVT relationships, providing data under truly process-relevant conditions [27]. This approach benefits from direct relevance to processing environments but may sacrifice some measurement precision.

Flash Differential Scanning Calorimetry (FSC)

For characterizing crystallization behavior at high cooling rates relevant to actual processing, Flash DSC has emerged as a powerful tool:

Instrument Capabilities: Modern FSC instruments (e.g., Flash DSC 2+) can achieve ultra-high cooling rates of up to 40,000 K/s, far exceeding conventional DSC limitations and matching the extreme conditions encountered in injection molding [28].

Experimental Protocol: The measurement process involves (1) heating the sample to erase thermal history (e.g., 220°C for PP), (2) cooling to a low temperature (e.g., 0°C) at precisely controlled rates, and (3) reheating to detect melting behavior. The cooling scans reveal temperatures of crystallization, while heating scans analyze the crystallinity developed during prior cooling [28].

Data Interpretation: From FSC curves, researchers extract the onset crystallization temperature (Ts) and maximum crystallization temperature (Tm). The extrapolated start temperature (Ts) is determined where the extrapolated baseline intersects with the tangent to the curve at the point of inflection, corresponding to the start of the transition. The peak temperature (Tm) is the temperature where the exothermic peak reaches its maximum [28].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the experimental methodology for characterizing polymer crystallization behavior using Flash DSC:

Mathematical Modeling of PVT Behavior

The Two-Domain Tait Equation

The Tait equation represents the most widely used model for describing PVT behavior in polymers, particularly for processing simulations. The standard form of the two-domain Tait equation is expressed as:

[ v(p,T) = v0(p0,T) \left[1 - C \ln\left(1 + \frac{p}{B(T)}\right)\right] + v_t(p,T) ]

Where:

- ( v(p,T) ) is the specific volume at pressure p and temperature T

- ( v0(p0,T) ) is the specific volume at zero pressure

- ( C ) is a universal constant (0.0894)

- ( B(T) ) represents pressure sensitivity as a function of temperature

- ( v_t(p,T) ) accounts for the specific volume decrease due to crystallization [25] [29]

The model utilizes different parameter sets for the melt (m) and solid (s) states, with the transition between domains defined by a transition temperature ( Tt ) that varies with pressure according to ( Tt = b5 + b6p ) [25] [29].

Cooling Rate Dependent Modifications

Traditional Tait equations lack cooling rate dependence, limiting their accuracy for simulating real processing conditions. Recent advances have introduced cooling rate dependencies through parameter modifications:

For semicrystalline polymers, the transition temperature parameter ( b_5 ) (representing crystallization onset) is made cooling rate-dependent using the relationship:

[ b5 = b{51} - b_{52} \times \ln(q) ]

where ( q = \frac{\dot{T}}{\dot{T}_0} ) represents the ratio of current cooling rate to the reference cooling rate [29].

The zero-pressure specific volume parameter in the melt state ( b_{1m} ) is adjusted according to:

[ b{1m} = b{11m} - ((b{52} \times \ln(q)) \times b{2m}) ]

This modification ensures proper continuity during phase transition while accounting for crystallization shifts [29].

The following diagram illustrates the structure and modifications of the cooling rate-dependent PVT model:

Model Implementation in Process Simulation

The practical application of cooling rate-dependent PVT models has been demonstrated through integration with commercial simulation software:

Moldflow Integration: Researchers have successfully implemented enhanced PVT models in Autodesk Moldflow Insight via the Solver API interface, enabling more accurate predictions of shrinkage and warpage in injection-molded components [25] [29].

3D Tetrahedron Mesh Compatibility: The cooling rate-dependent models have been validated using 3D tetrahedron meshed calculation models, confirming their suitability for complex geometries where simplified approaches (e.g., middle-layer or surface meshing) prove inadequate [25].

Experimental Validation: Modified PVT models show excellent agreement with experimental data, achieving remarkable statistical accuracy with R² values of 99.82% and average absolute percent deviations as low as 0.21% [24].

Table 3: Essential Equipment for PVT and Crystallization Studies

| Equipment/Reagent | Primary Function | Key Specifications | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flash DSC 2+ | High-rate crystallization analysis | Cooling rates to 40,000 K/s | Characterization of crystallization at processing-relevant conditions |

| High-Pressure Capillary Rheometer | PVT diagram measurement | ISO 17744 compliance | Isobaric and isothermal PVT data collection |

| Confining Fluid Dilatometer | Specific volume measurement | 60 K/s cooling, 20 MPa pressure | PVT behavior at intermediate cooling rates |

| Polypropylene Reference Material | Benchmark semicrystalline polymer | MFR: 18 g/10 min (230°C, 2.16 kg) | Model material for crystallization studies |

| Tait Model Parameters | Mathematical modeling | b₁-b₉ coefficients | PVT behavior simulation |

Comparative Analysis and Research Implications

Quantitative Comparison of PVT Behaviors

The differences between amorphous and semicrystalline polymers manifest clearly in quantitative PVT measurements:

Specific Volume Values: At processing temperatures (e.g., 200°C), amorphous polymers such as polycarbonate typically exhibit specific volumes of approximately 0.95-1.05 cm³/g, while semicrystalline polymers like polypropylene show similar values in the melt state. However, upon cooling to room temperature, amorphous polymers contract to about 0.85-0.95 cm³/g, while semicrystalline materials achieve significantly lower values of 0.75-0.85 cm³/g due to crystalline packing [27].

Cooling Rate Sensitivity: Research demonstrates that for semicrystalline polypropylene, increasing cooling rate from 2°C/min to 10°C/min can reduce crystallinity by 15-25%, with corresponding specific volume increases of 1.5-3.0% [30] [28]. Amorphous polymers show less than 0.5% specific volume change over the same cooling rate variation.

Implications for Processing and Product Development

The differential PVT behavior between amorphous and semicrystalline polymers has significant practical implications:

Injection Molding: For semicrystalline polymers, the cooling rate variation through part thickness creates through-thickness crystallinity gradients, leading to differential shrinkage and potential warpage. Amorphous materials exhibit more uniform shrinkage due to their weaker cooling rate dependence [26].

Dimensional Stability: Semicrystalline products may experience post-molding crystallization and subsequent dimensional changes over time, particularly when exposed to elevated temperatures. Amorphous components generally demonstrate superior dimensional stability once initially cooled [26].

Process Simulation Accuracy: Traditional simulation approaches that neglect cooling rate effects for semicrystalline polymers can exhibit significant errors in predicting final part dimensions and properties. Implementing cooling rate-dependent PVT models improves prediction accuracy by 20-40% for critical dimensions [25] [29].

The PVT behavior during cooling diverges fundamentally between amorphous and semicrystalline polymers, with the latter exhibiting complex cooling rate dependence due to crystallization kinetics. These differences necessitate distinct approaches to material characterization, process optimization, and simulation modeling. Experimental techniques such as Flash DSC have revealed the profound influence of cooling rate on crystallization temperatures and ultimate crystallinity in semicrystalline systems. Mathematical models incorporating cooling rate parameters through modified Tait equations now enable more accurate process simulations, particularly for injection molding applications. Understanding these differential behaviors provides researchers and development professionals with critical insights for material selection, process design, and quality optimization in polymer-based products and drug delivery systems.

Advanced Characterization and Processing: Techniques for Analyzing and Manipulating Thermal Properties

Understanding the thermal properties of amorphous and semicrystalline materials is a cornerstone of advanced materials science, polymer research, and pharmaceutical development. These properties dictate material behavior under thermal stress, directly influencing performance, stability, and processing conditions. This guide provides an objective comparison of four pivotal analytical techniques—Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC), Dynamic Mechanical Thermal Analysis (DMTA), Thermally Stimulated Current (TSC), and Heat Accumulation Spectroscopy (HAS)—framed within contemporary research on amorphous semicrystalline thermal properties. The selection of an appropriate analytical tool is critical, as each technique probes distinct material properties through different physical principles. For researchers investigating complex phenomena such as glass transitions, molecular mobility, crystallization kinetics, and viscoelastic behavior, a nuanced understanding of the capabilities, limitations, and complementary nature of these techniques is essential. This article synthesizes current methodologies, experimental data, and practical protocols to serve as a foundational resource for scientists making informed decisions in thermal analysis.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

DSC operates on the principle of measuring the heat flow difference between a sample and an inert reference as they are subjected to a controlled temperature program. It directly assesses enthalpic changes associated with thermal transitions. There are two primary types: Heat-Flux DSC, where the sample and reference are contained in a single furnace and the temperature difference is measured, and Power-Compensated DSC, which uses separate furnaces and measures the power required to maintain the sample and reference at the same temperature [31] [32]. Power-compensated DSC is noted for its superior sensitivity and precise temperature control, making it suitable for materials requiring fine thermal resolution [33]. Key measurements include glass transition temperature (Tg), melting point, crystallization temperature, heat of fusion, and specific heat capacity.

Dynamic Mechanical Thermal Analysis (DMTA)

DMTA, also referred to as Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA), characterizes a material's viscoelastic properties by applying a oscillatory stress or strain and measuring the resultant strain or stress. It provides data on the storage modulus (E') (elastic response), loss modulus (E") (viscous response), and tan delta (tan δ) (damping, the ratio of loss to storage modulus) as functions of temperature, time, or frequency [34] [35]. DMTA is exceptionally sensitive to the glass transition, which is detected as a peak in tan δ or a sharp drop in the storage modulus, revealing molecular relaxations that are often undetectable by DSC.

Thermally Stimulated Current (TSC)

Thermally Stimulated Current (TSC) is a highly sensitive dielectric technique for studying molecular relaxations in polymers and amorphous materials. In a TSC experiment, the sample is polarized by an electric field at a higher temperature, "freezing" in the dipole orientations by cooling the sample under the field. The field is removed, and the sample is heated at a constant rate. The depolarization current, resulting from the reorientation of molecular dipoles as they gain mobility, is measured as a function of temperature. This yields a spectrum with peaks corresponding to specific molecular relaxation processes, including the glass transition and secondary relaxations [32]. TSC can effectively "resolve" complex relaxations into their constituent processes.

Heat Accumulation Spectroscopy (HAS)

Heat Accumulation Spectroscopy (HAS) is a less common technique mentioned in the user's request. Detailed technical principles and standard methodologies for HAS were not identified in the search results. Based on the name and context among other thermal techniques, it is presumed to be a method for investigating thermal stability or energy release properties, potentially under non-equilibrium conditions. Its specific application to amorphous semicrystalline research could not be substantiated from available sources, and it will be noted where information is unavailable in subsequent sections.

Comparative Performance Analysis

The following tables provide a direct, data-driven comparison of the operational characteristics and performance outputs of DSC, DMTA, and TSC.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Thermal Analysis Techniques

| Feature | DSC | DMTA | TSC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Measured Property | Heat Flow (mW) [35] | Storage/Loss Modulus, Tan Delta [35] | Depolarization Current (A) |

| Key Measured Transitions | Melting (Tm), Crystallization (Tc), Glass Transition (Tg), Curing Enthalpy [32] | Glass Transition (Tg), Sub-Tg Relaxations, Crosslinking Density [35] | Glass Transition (Tg), Localized Dipole Relaxations |

| Typical Sample Mass | 1 - 10 mg [35] | Varies with geometry (e.g., film, bar) | Thin films/coatings |

| Detection Sensitivity for Tg | Moderate (step change in Cp) [34] | High (peak in tan δ) [35] | Very High (direct current measurement) |

| Fundamental Principle | Thermodynamic (Enthalpic) [34] | Mechanical (Viscoelastic) [34] | Dielectric (Dipolar) |

Table 2: Quantitative Data from Experimental Studies

| Experiment / Material | DSC Data | DMTA Data | TSC Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Composite (Epoxy) | Cure exotherm: ~300 J/g [35] | Tan δ peak for crosslinked network | Not available in search results |

| Biomaterial (Collagen Scaffold) | Denaturation Enthalpy: 122 J/g [35] | Storage Modulus drop from 2.1 GPa to 85 MPa at Tg [35] | Not available in search results |

| Starch/Gluten System at Low Moisture | Tg ~50-60°C (heating rate dependent) [34] | Not available in search results | Not available in search results |

| Semicrystalline Polymer (PEEK/CF) | Tm variation: ±5°C [35] | 18% reduction in interfacial adhesion [35] | Not available in search results |

Key Comparative Insights:

- Complementary Nature: DSC and DMTA detect the glass transition through different phenomena. DSC identifies the change in heat capacity, while DMTA detects the associated mechanical relaxation, often at a slightly higher temperature [34] [35]. A 2023 study on epoxy composites confirmed that DMTA better quantifies crosslinking density, whereas DSC is superior for capturing the total enthalpy of the curing reaction [35].

- Sensitivity: DMTA and TSC are recognized as more sensitive than DSC for detecting weak transitions and secondary relaxations, especially in highly crosslinked or rigid amorphous materials where the change in heat capacity is minimal [34].

- Throughput vs. Detail: DSC provides absolute thermodynamic parameters (e.g., ΔH) and is a workhorse for routine characterization. While high-throughput DSC exists, conventional systems have lower throughput compared to some spectroscopic methods. TSC, though highly sensitive, is not typically a high-throughput technique [35].

Experimental Protocols for Key Measurements

Protocol 1: Determining Glass Transition in Amorphous Polymers via DSC and DMTA

Objective: To characterize the glass transition temperature (Tg) of an amorphous polymer film using complementary DSC and DMTA techniques.

Materials:

- Amorphous polymer (e.g., Polystyrene, PMMA)

- DSC instrument (e.g., TA Instruments Discovery series, Mettler Toledo DSC 3+) [36] [37]

- DMTA instrument (e.g., TA Instruments DMA Q800)

- Hermetic aluminum pans for DSC

- Sample clamp for DMTA (e.g., tension or dual-cantilever)

- Sample Preparation: Precisely weigh 5-10 mg of the polymer and seal it in a hermetic aluminum pan. An empty, sealed pan serves as the reference.

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate the DSC for temperature and enthalpy using indium or other certified standards.

- Temperature Program: Equilibrate at -30°C. Heat the sample and reference at a constant rate of 10°C/min to 150°C. Maintain an inert atmosphere (e.g., N2 gas at 50 mL/min).

- Data Analysis: In the resulting heat flow curve, identify the glass transition as a step-like change. The Tg is typically reported as the midpoint of the transition step.

DMTA Methodology [35]:

- Sample Preparation: Cut the polymer film to the dimensions required for the selected clamp (e.g., a rectangular bar of 20mm x 10mm x 0.5mm).

- Instrument Setup: Mount the sample securely in the clamp, ensuring good contact without over-tightening. Set the oscillation frequency (e.g., 1 Hz) and strain amplitude within the linear viscoelastic region.

- Temperature Program: Equilibrate at -30°C. Heat the sample at a constant rate of 3°C/min to 150°C.

- Data Analysis: Plot storage modulus (E') and tan delta (tan δ) versus temperature. The Tg is identified as the peak temperature of the tan δ curve.

Protocol 2: Investigating Curing Kinetics of Thermosets via DSC

Objective: To monitor the curing reaction and determine the kinetics of a thermoset resin using non-isothermal DSC.

Materials:

- Uncured thermoset resin (e.g., epoxy, polyester powder coating) [37]

- DSC instrument (Mettler Toledo DSC 3+ or equivalent)

- High-pressure crucibles (if needed)

Methodology [37]:

- Sample Preparation: Place 5-10 mg of the uncured resin in an aluminum crucible. A lid may be placed on the pan but not hermetically sealed to allow for potential gas escape.

- Experimental Run: Run dynamic scans at multiple heating rates (e.g., 5, 10, 15, and 20°C/min) from room temperature to a temperature well beyond the expected reaction exotherm (e.g., 250°C).

- Data Analysis:

- For each heating rate, integrate the area under the curing exotherm peak to obtain the total reaction enthalpy (ΔH).

- The degree of conversion (α) at any temperature (T) can be calculated as α(T) = ΔH(T) / ΔH

total, where ΔH(T) is the partial area up to T. - Use isoconversional methods (e.g., Friedman or Starink) to calculate the activation energy (E

a) as a function of the degree of conversion.

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a generalized decision-making and experimental workflow for characterizing amorphous semicrystalline materials, integrating the discussed techniques.

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Thermal Analysis

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Materials and Reagents for Thermal Analysis Experiments

| Item Name | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hermetic Aluminum Crucibles | Standard containers for DSC samples, prevent mass loss from volatile components. | Essential for aqueous solutions, organic solvents, or materials that may degrade. [31] |

| High-Pressure Crucibles | Contain samples that may generate high pressure during heating (e.g., decomposition, volatile release). | Used in High-Pressure DSC (HP-DSC) for specific reactions. [31] |

| Indium Calibration Standard | Primary standard for temperature and enthalpy calibration of DSC instruments. | High-purity (99.999%) indium has a sharp melting point of 156.6°C and a well-defined heat of fusion. [32] |