Amorphous vs Crystalline Polymers: Structure, Properties, and Advanced Applications in Drug Delivery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of amorphous and crystalline polymer structures, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Amorphous vs Crystalline Polymers: Structure, Properties, and Advanced Applications in Drug Delivery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of amorphous and crystalline polymer structures, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental morphological differences, from molecular chain arrangement to thermal transitions like glass transition (Tg) and melting point (Tm). The scope extends to advanced methodological applications, particularly in controlled drug delivery systems, covering diffusion-controlled, solvent-activated, and biodegradable platforms. Practical guidance on material selection, processing challenges, and optimization strategies is included, alongside a rigorous comparative analysis of mechanical, thermal, and chemical properties. The content synthesizes these aspects to empower informed decision-making for biomedical and clinical research applications, highlighting future directions in intelligent polymer-based therapeutics.

The Molecular Blueprint: Understanding Polymer Morphology and Core Principles

Defining Amorphous and Crystalline Polymer Structures

Polymer morphology, which describes the arrangement and state of order of polymer chains, is a fundamental aspect of materials science that directly determines the physical and chemical properties of polymeric materials. Unlike small-molecule compounds that exist in three distinct states of matter—solids, liquids, and gases—polymers exhibit more complex behavior due to their high molecular weight, with molecular weights ranging from tens of thousands to several million atomic mass units [1]. This substantial molecular size significantly impacts their unique properties and classification. Polymers are broadly categorized into two morphological types: amorphous and crystalline [1]. Surprisingly, polymeric solids can simultaneously possess both amorphous and crystalline regions, a concept particularly important to polymer science [1]. Understanding this distinction is crucial for researchers and scientists, especially in drug development, where polymer morphology affects drug loading, release kinetics, and biocompatibility.

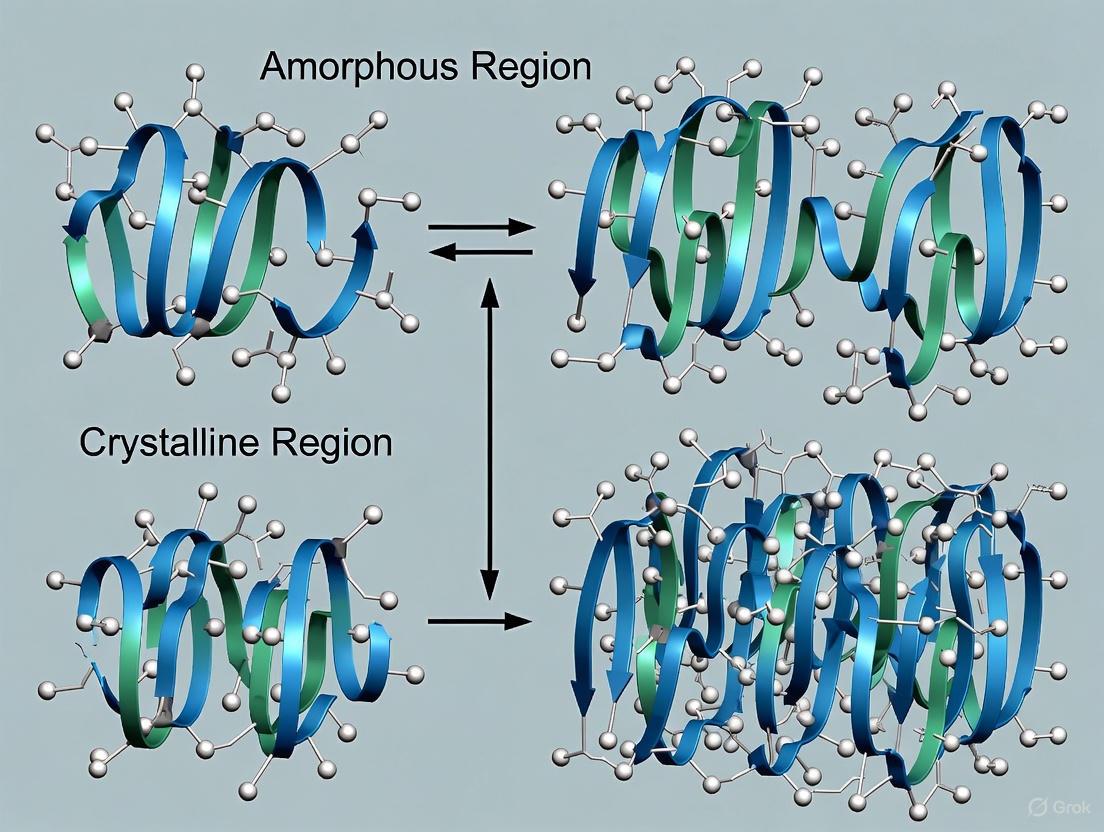

The arrangement of polymer chains differs fundamentally between amorphous and crystalline structures. In amorphous polymers, atoms are held together in a loose, irregular structure without long-range order, similar to a tangled mass of cooked spaghetti [1] [2]. In contrast, chains in crystalline polymers form orderly stacks of folded chains known as lamellae, which bring long-range order to the material [1] [2]. Most crystalline polymers contain amorphous regions, meaning they are never completely crystalline [1]. Scientists refer to a polymer's "degree of crystallinity" to describe its position along the spectrum from entirely amorphous (0%) to entirely crystalline (100%), with most practical polymers falling somewhere between these extremes [1] [2].

Structural Characteristics and Molecular Order

Amorphous Polymer Structure

Amorphous polymers exhibit a random molecular configuration with no long-range order, characterized by a loose, irregular structure where chains are tangled and intertwined [1] [2]. This disordered arrangement is often visualized as a plate of cooked spaghetti noodles, with chains forming a hopelessly entangled mass without predictable patterns [1]. The distances between atoms in amorphous structures can vary substantially, unlike in crystalline materials where atomic distances are much more consistent [2]. This molecular-level disorder manifests in macroscopic properties such as transparency, gradual softening upon heating, and isotropic behavior [3] [4].

The lack of orderly structure in amorphous polymers arises from chain entanglement, where polymer chains become randomly arrayed throughout the material, making atomic positions quasi-random [1]. In this configuration, chemists describe amorphous solids as having no long-range order, though they may exhibit short-range order at the molecular level [2]. This structural characteristic significantly influences the thermal and mechanical behavior of amorphous polymers, particularly through the glass transition temperature (Tg), below which the material becomes glassy, brittle, and rigid [1].

Crystalline and Semi-Crystalline Polymer Structure

Crystalline polymers display a highly ordered molecular structure where chains are arranged in a regular, repeating pattern [3]. Instead of becoming randomly tangled, the polymer chains form orderly stacks of folded chains known as lamellae [1] [2]. These lamellae bring long-range order to polymers, creating a more orderly arrangement similar to atoms in typical crystals [1]. Interestingly, some lamellae in certain polymers feature small numbers of chains that loop out from the orderly stacks, creating amorphous regions within an otherwise crystalline polymer [1].

Most crystalline polymers are more accurately described as semi-crystalline, containing both crystalline and amorphous regions coexisting within the same material [1] [4]. The crystalline regions provide structural strength and stability, while the amorphous regions contribute flexibility and impact resistance [5]. The proportion of crystalline to amorphous regions—the degree of crystallinity—directly influences the polymer's physical properties, including tensile strength, impact resistance, opacity, and chemical resistance [5] [3]. Chain flexibility plays a crucial role in crystal formation, as chains must be able to flex and bend to arrange themselves into orderly structures [1].

Table 1: Fundamental Structural Differences Between Amorphous and Crystalline Polymers

| Structural Characteristic | Amorphous Polymers | Crystalline Polymers |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Arrangement | Random, disordered chains [1] | Ordered, repeating patterns [3] |

| Long-Range Order | Absent [1] [2] | Present [1] |

| Chain Organization | Tangled mass (cooked spaghetti) [1] | Folded stacks (lamellae) [1] [2] |

| Degree of Crystallinity | 0% (theoretically) to low [1] | Ranges from medium to high (never 100%) [1] |

| Representative Diagram | A1 | A2 |

Key Property Differences and Material Behavior

The structural differences between amorphous and crystalline polymers manifest in distinct thermal, mechanical, optical, and chemical properties that determine their suitability for specific applications, particularly in pharmaceutical and biomedical contexts.

Thermal Properties

Thermal behavior represents one of the most fundamental distinctions between amorphous and crystalline polymers. Amorphous polymers do not have a true melting point but instead undergo a gradual transition from a glassy to a rubbery state as temperature increases [1] [3]. This transition occurs over a temperature range known as the glass transition temperature (Tg) [1] [2]. Below Tg, amorphous polymers are hard, rigid, and brittle, while above Tg, they become softer and more flexible as the entangled chains gain mobility [1]. In contrast, crystalline polymers have a definite melting point (Tm) at which the orderly arrangement of their long-chain structure transitions to a random, disorganized arrangement [1] [3]. Highly crystalline polymers melt suddenly at a specific temperature rather than softening gradually [1].

Mechanical and Physical Properties

The mechanical behavior of polymers is strongly influenced by their morphology. Crystalline polymers generally exhibit superior mechanical strength, stiffness, and dimensional stability due to their ordered structure and tight molecular packing [3] [4]. These materials typically have higher density and undergo greater shrinkage during cooling as the polymer chains pack more efficiently [3]. However, this ordered structure can make them more brittle and prone to fracture under impact [4]. Amorphous polymers, with their random chain arrangement, tend to be more flexible, less brittle, and more resistant to stress cracking [3]. They demonstrate better impact resistance at room temperature but lose toughness quickly above their glass transition temperature, becoming malleable and prone to elongation [2].

Optical and Chemical Properties

Optical properties differ significantly between amorphous and crystalline polymers. Amorphous polymers, with their random entanglement of chains, tend to allow light to pass through them, resulting in transparent materials [2] [4]. As the percentage crystallinity increases, polymers become progressively less transparent due to light scattering at the boundaries between crystalline and amorphous regions [2]. Chemical resistance is another area of differentiation, with crystalline polymers generally offering excellent chemical resistance due to their tight molecular packing that impedes solvent penetration [3]. Amorphous polymers are typically more susceptible to chemical attack and solvent penetration, though specific polymers may exhibit notable chemical resilience [3] [4].

Table 2: Comparative Properties of Amorphous and Crystalline Polymers

| Property | Amorphous Polymers | Crystalline Polymers |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal Behavior | Glass transition temperature (Tg); softens gradually [1] [3] | Definite melting point (Tm); melts suddenly [1] [3] |

| Mechanical Strength | Lower strength, higher flexibility [3] [4] | Higher strength, stiffness [3] [4] |

| Impact Resistance | Good at room temperature [4] | Poor [4] |

| Optical Clarity | Transparent [2] [4] | Opaque to translucent [2] |

| Chemical Resistance | Moderate to low [3] | Excellent [3] |

| Shrinkage During Cooling | Minimal [3] | Significant [3] |

| Density | Lower [3] | Higher [3] |

| Wear Resistance | Poor [4] | Excellent [4] |

Characterization Techniques and Experimental Protocols

Analyzing polymer crystallinity requires sophisticated characterization techniques that can probe material structure at molecular and atomic levels. These methods are essential for quality control, research and development, and understanding structure-property relationships in pharmaceutical applications.

X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

X-ray diffraction is a powerful technique for determining the crystalline structure of polymers by measuring the distances between atoms [5]. When X-rays interact with a crystalline polymer, they produce a diffraction pattern that reveals information about the atomic arrangement and degree of crystallinity [5] [6]. The experimental protocol involves placing a polymer sample in the XRD instrument and exposing it to X-ray radiation. The diffraction pattern is then collected and analyzed to identify crystalline phases and determine the percentage crystallinity [5]. XRD can also monitor changes in crystallinity during processing or under strain, providing insights into structure-property relationships [6]. Modern XRD systems like Malvern Panalytical's Aeris and Empyrean offer modular designs that can be adapted for various sample types and analysis requirements [5].

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Differential scanning calorimetry measures heat flow into or out of a polymer sample during controlled heating or cooling, providing information about thermal transitions [2] [6]. The experimental protocol involves placing a small polymer sample (typically 5-10 mg) in a sealed pan alongside an empty reference pan in the DSC instrument [2]. The temperature is increased at a controlled rate (e.g., 10°C per minute), and the heat flow difference between the sample and reference is measured. This allows detection of thermal events such as the glass transition temperature (Tg) in amorphous polymers and melting point (Tm) in crystalline polymers [2] [6]. DSC provides valuable information about a polymer's thermal history, crystallinity, and stability, which is crucial for pharmaceutical processing and drug delivery system design [6].

Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

Dynamic mechanical analysis applies oscillatory force to a polymer sample while measuring its response across a temperature range, providing information about viscoelastic behavior [2]. In a typical DMA experiment, a polymer sample of specific dimensions is clamped in the instrument and subjected to a small oscillating deformation while temperature is varied. The instrument measures the complex modulus, including storage modulus (elastic response) and loss modulus (viscous response), revealing the polymer's stiffness and damping characteristics [2]. DMA is particularly sensitive for detecting glass transitions and other secondary relaxations that might be missed by DSC, making it invaluable for understanding polymer behavior in biomedical applications [2].

Additional Characterization Methods

Other important techniques for polymer characterization include tensile testing, which measures force required to pull polymer films until breakage to determine tensile strength and elongation at break [2]; polarized optical microscopy (POM) with hot-stage capability for visualizing crystalline structures and morphology development [7]; scanning electron microscopy (SEM) for examining surface morphology [7]; and atomic force microscopy (AFM) for high-resolution imaging of polymer surfaces [7]. Each technique provides complementary information, and researchers often use multiple methods to fully characterize polymer structure [2] [7].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for Polymer Characterization

| Reagent/Equipment | Function/Application | Experimental Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| XRD Instrument (e.g., Aeris, Empyrean) [5] | Measures atomic distances and crystallinity [5] | Identifies crystalline phases; quantifies degree of crystallinity [5] [6] |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter [2] [6] | Measures heat flow during thermal transitions [2] [6] | Determines Tg (amorphous) and Tm (crystalline); analyzes thermal stability [2] [6] |

| Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer [2] | Applies oscillatory force to measure viscoelastic properties [2] | Characterizes stiffness and damping across temperature ranges [2] |

| Tensile Testing Machine [2] | Pulls polymer film to measure mechanical properties [2] | Determines tensile strength and elongation at break [2] |

| Polarized Optical Microscope with hot-stage [7] | Visualizes crystalline structures and morphology [7] | Observes spherulite formation and crystalline development [7] |

| Etching Reagents (e.g., acids, permanganate) [7] | Selectively removes amorphous regions [7] | Enhances contrast for microscopy; reveals lamellar structure [7] |

Applications in Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Fields

The distinct properties of amorphous and crystalline polymers make each suitable for specific biomedical and pharmaceutical applications, particularly in drug delivery, bioimaging, and medical devices.

Drug Delivery Systems

Polymer morphology plays a crucial role in drug delivery system design, influencing drug loading capacity, release kinetics, and degradation behavior. Amorphous polymers often demonstrate higher drug loading capacity due to their more open molecular structure, while the release profile can be modulated by the polymer's glass transition temperature [2]. The random molecular structure of amorphous polymers lacking a sharp melting point allows them to soften gradually as temperature increases, which can be exploited for controlled release applications [1] [3]. Their deformability enables them to bond well with substrates, making them suitable for transdermal patches and adhesive drug delivery systems [2].

Crystalline polymers, with their excellent chemical resistance and tight molecular packing, provide effective barriers that can protect drugs from degradation and control release rates [3]. Their well-defined melting behavior and structural stability make them suitable for implantable devices that require predictable erosion profiles [1] [3]. The balance between crystalline and amorphous regions in semi-crystalline polymers can be tailored to achieve specific drug release profiles, with crystalline regions providing structural integrity and amorphous regions allowing drug diffusion [5].

Bioimaging and Theranostic Applications

Polymer-based nanostructures have emerged as valuable tools for bioimaging, serving as carriers for contrast agents in various imaging modalities including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), and optical imaging [8] [9]. The versatility of polymer design allows creation of sophisticated bioimaging probes with prolonged plasma half-lives, enhanced stability, reduced toxicity, and improved targeting compared to small molecule agents [8] [9].

Amorphous polymers are particularly useful in designing bioimaging probes due to their flexibility and ability to accommodate various imaging moieties [2] [8]. Their random structure allows incorporation of contrast agents like gadolinium for MRI or fluorescent dyes for optical imaging [8] [9]. Crystalline polymers, with their more ordered structure, provide stability and protection for imaging agents, making them suitable for applications requiring long circulation times or resistance to degradation [3]. The development of polymer-based theranostic agents that combine imaging and therapeutic functions represents a significant advancement in personalized medicine [8].

Medical Devices and Implants

Both amorphous and crystalline polymers find extensive applications in medical devices and implants, with material selection based on required mechanical properties, biocompatibility, and degradation behavior. Crystalline polymers like polyether ether ketone (PEEK) are favored for load-bearing implants due to their high strength, stiffness, and excellent wear resistance [3]. Their chemical inertness makes them suitable for long-term implants, while their predictable melting behavior facilitates processing and sterilization [3].

Amorphous polymers such as polycarbonate (PC) and polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) are widely used in applications requiring transparency, including optical devices, lenses, and surgical instruments [4]. Their impact resistance and ability to be sterilized make them valuable for medical equipment housings and disposable devices [4]. The glass transition temperature of amorphous polymers must be carefully considered for medical devices that undergo heat sterilization, as temperatures above Tg can cause deformation [2].

Emerging Trends and Research Directions

Polymer science continues to evolve with emerging technologies enabling more precise control and characterization of amorphous and crystalline structures.

Machine learning (ML) approaches are increasingly applied to understand the complex relationships between polymer composition, processing conditions, structure, and properties [10]. ML algorithms can analyze vast datasets to predict polymer crystallinity based on chemical structure and processing parameters, accelerating materials discovery and optimization [10]. These techniques are particularly valuable for designing polymers with tailored crystallinity for specific pharmaceutical applications, such as controlled-release formulations or biodegradable implants [10].

Advanced characterization techniques are providing new insights into polymer morphology at multiple length scales. The combination of multiple analytical methods, including X-ray diffraction, thermal analysis, and electron microscopy, allows researchers to develop comprehensive understanding of structure-property relationships in both amorphous and crystalline polymers [6] [7]. These insights are driving the development of novel polymer systems with hierarchical structures that optimize performance for specific biomedical applications [7].

Sustainable polymer design represents another important research direction, with growing emphasis on developing biodegradable polymers with controlled crystallinity for pharmaceutical and medical applications [6]. Understanding how crystallinity affects degradation rates is crucial for designing implantable devices and drug delivery systems that maintain structural integrity until their function is complete, then safely degrade in the body [6].

The distinction between amorphous and crystalline polymer structures represents a fundamental concept in polymer science with significant implications for pharmaceutical and biomedical applications. Amorphous polymers, with their random molecular arrangement and glass transition behavior, offer advantages including transparency, impact resistance, and gradual softening. Crystalline polymers, characterized by their ordered structure and definite melting points, provide superior strength, chemical resistance, and thermal stability. Most practical polymers exist in a semi-crystalline state with varying degrees of crystallinity that can be tailored to achieve specific performance characteristics.

Characterization techniques such as XRD, DSC, and DMA provide essential tools for analyzing polymer morphology and understanding structure-property relationships. These methods enable researchers to optimize polymer systems for specific drug delivery, bioimaging, and medical device applications. Emerging technologies including machine learning and advanced microscopy techniques continue to enhance our understanding of polymer crystallinity and its influence on material behavior. As polymer science advances, the ability to precisely control amorphous and crystalline structures will continue to drive innovation in pharmaceutical development and biomedical engineering.

In polymer science, the macroscopic properties of a material are fundamentally dictated by its molecular architecture. Unlike small molecules, polymers possess high molecular weights, leading to complex behaviors and interactions between their long chains [1]. These structures are broadly categorized into two distinct morphologies: amorphous and crystalline. Amorphous polymers are characterized by a loose, random arrangement of molecular chains with no long-range order, akin to a pile of cooked spaghetti. In contrast, crystalline polymers feature regions where chains fold into orderly, stacked structures known as lamellae [1]. Most crystalline polymers are, in fact, semi-crystalline, containing both these ordered lamellae and disordered amorphous regions. The proportion of crystalline material is defined by a polymer's degree of crystallinity, which ranges from 0% (entirely amorphous) to 100% (entirely crystalline), with most practical polymers existing between these extremes [1]. This morphological dichotomy governs critical material properties, including mechanical strength, thermal behavior, optical clarity, and chemical resistance.

Structural Fundamentals: Amorphous Architecture

The Role of Chain Entanglement

In amorphous polymers, the molecular chains are arranged in a random, loose structure without any predictable, long-range order. This configuration is a direct result of chain entanglement, where the lengthy polymer chains become hopelessly intertwined [1]. A single polymer chain can be visualized as a piece of spaghetti; when multiple chains are present, they form a wildly random pile of intertwined "polymers" with quasi-random atomic positions. This extensive entanglement is the key structural feature governing the behavior of amorphous materials.

Thermal Transitions: The Glass Transition

Amorphous solids lack a sharp melting point. Instead, they undergo a gradual transition over a range of temperatures known as the glass transition temperature (Tg) [1]. Below the Tg, the entangled amorphous polymer chains are frozen and cannot move, resulting in a hard, rigid, and brittle glassy state. When the temperature rises above the Tg, small portions of the chains gain sufficient mobility to move, leading to a soft and flexible rubbery state [1]. This transition is a defining characteristic of amorphous polymers.

Structural Fundamentals: Crystalline Architecture

Formation of Lamellae Stacks

In crystalline polymers, the molecular chains do not become randomly tangled. Instead, they form orderly stacks of folded chains, known as lamellae [1]. These lamellae introduce long-range order to the polymer, creating a more structured arrangement similar to the orderly atomic packing in typical crystals. The folding allows the long chains to organize into tight, structured zones. Interestingly, not every part of a chain is incorporated into a lamella; some portions may form loops or extend out from the orderly stacks, creating amorphous regions within an otherwise crystalline polymer [1].

The Semi-Crystalline Reality and Inter-Lamellar Connections

Most crystalline polymers are semi-crystalline, meaning they contain a mixture of crystalline lamellae and amorphous regions [11]. On a sub-micron scale, the morphology consists of stacks of crystal lamellae sandwiching intermediate amorphous layers. The polymer chains within these amorphous regions can adopt several configurations, including tight folds, statistical loops, loose chain ends (cilia), and crucially, tie chains and trapped entanglements [11].

- Tie Chains: Polymer chains that extend from one crystalline lamella and connect directly to an adjacent lamella, threading through the amorphous region.

- Trapped Entanglements: Chains that connect to adjacent crystal layers via permanently entangled loops.

These inter-lamellar connections are extremely important for the material's mechanical performance, particularly its fracture toughness and resistance to slow crack growth [11]. In branched polyethylenes, for example, the rejection of bulky branches from the crystal lattice can lead to thinner lamellae but also increase the number of these vital inter-lamellar connections, enhancing fracture toughness [11].

Comparative Analysis: Property Implications

The fundamental structural differences between amorphous and crystalline polymers lead to distinct property profiles, which are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Property Differences Between Amorphous and Crystalline Polymers [1] [3] [4]

| Property | Amorphous Polymers | Crystalline Polymers |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Structure | Randomly entangled chains; no long-range order [1] | Ordered lamellae stacks of folded chains; long-range order [1] |

| Thermal Behavior | No sharp melting point; softens over a temperature range (characterized by Tg) [1] [3] | Sharp melting point (Tm) due to ordered structure [1] [3] |

| Mechanical Properties | More flexible, better impact resistance, less brittle [4] | Superior mechanical strength, stiffness, and dimensional stability [3] [4] |

| Optical Properties | Often transparent [3] [4] | Typically opaque or translucent [3] |

| Chemical Resistance | More prone to chemical attack and solvent penetration [1] [3] | Excellent chemical resistance due to tight molecular packing [1] [3] |

| Density & Shrinkage | Lower density; minimal shrinkage during cooling [3] | Higher density; greater shrinkage due to crystallization [3] |

Table 2: Examples of Amorphous and Crystalline Polymers and Their Transitions [1]

| Polymer | Type / Tacticity | Glass Transition Temp (Tg) | Melting Point (Tm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polypropylene | Atactic (Amorphous) | -17°C (1.4°F) | Does not apply |

| Polystyrene | Atactic (Amorphous) | 100°C (212°F) | Does not apply |

| Polybutadiene | Amorphous | -106°C (-159°F) | Does not apply |

| Poly(methyl methacrylate) | Amorphous | 120°C (248°F) | Does not apply |

| Polypropylene | Isotactic (Crystalline) | Does not apply | 174°C (345°F) |

| Polyethylene | Crystalline | Does not apply | 137°C (279°F) |

| Nylon | Crystalline | Does not apply | 260°C (500°F) |

| Polystyrene | Syndiotactic (Crystalline) | Does not apply | 270°C (518°F) |

Advanced Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Monte Carlo Simulation of Semi-Crystalline Polyethylene

To quantitatively assess the concentration of critical inter-lamellar features like tie chains and trapped entanglements, advanced computational models are employed.

Objective: To simulate the semi-crystalline structure of branched polyethylene and study how short-chain branching affects the concentrations of tie chains and trapped entanglements [11].

Methodology - The Extended Nilsson Model: This method uses an off-lattice Monte Carlo algorithm to generate alternating parallel crystalline and amorphous layers [11].

- System Generation: The model creates a simulation domain representing the polymer, incorporating the entire crystal thickness distribution rather than single values, allowing for a more realistic morphology.

- Chain Walking: A numerical algorithm uses the stored atomic coordinates to perform a random walk, simulating the path of polymer chains through the semi-crystalline structure.

- Parameter Evaluation: The algorithm identifies and quantifies parameters of interest:

- A tie chain is identified when a single chain connects two different crystal lamellae.

- A trapped entanglement is counted when two chains originating in different lamellae are permanently entangled within the amorphous region [11].

- Input Data: The model is calibrated and validated using data from real polyethylene samples characterized by techniques like Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) for molar mass and

13CNMR for branch content [11].

Key Findings:

- The presence of short-chain branches (e.g., butyl branches) increases the number of inter-lamellar tie chains and trapped entanglements.

- This increase in connectivity leads to a stronger mechanical network and enhanced fracture toughness, explaining the superior performance of certain branched polyethylenes in applications requiring resistance to slow crack growth [11].

AI-Guided High-Throughput Investigation of Polymer Doping

The electronic properties of conjugated polymers for applications like bioelectronics are highly dependent on their structure and doping efficiency.

Objective: To understand how processing parameters affect the electronic properties of doped conjugated polymers and identify key structural variables for high conductivity [12].

Methodology - The DopeBot System: This approach combines artificial intelligence (AI) with high-throughput experimentation to efficiently explore a vast parameter space.

- AI-Guided Experimentation: An AI algorithm (DopeBot) was tasked with producing a wide range of conductivities using a model polymer (pBTTT) and a dopant (F4TCNQ). The system designed cycles of 32 experiments at a time, varying parameters like solvent and temperature [12].

- Characterization: The results of each batch (e.g., electronic properties, molecular structure) were characterized and fed back to the AI.

- Informed Iteration: The AI used the results to design the subsequent batch of experiments, leading to 224 informed experiments in total [12].

- Causal Analysis: Advanced analytic techniques identified correlations, and quantum chemical calculations were used to establish causality between dopant location and electronic properties [12].

Key Findings:

- Achieving high conductivity (>100 S/cm) requires processing conditions that promote ordered polymer domains.

- Local polymer order and dopant-polymer separation are critical. "Peripheral" counterions located at greater distances (≈1.3–1.8 nm) from the polymer backbone result in highly delocalized polarons and higher carrier mobility compared to intercalated counterions [12].

Periodicity-Aware Deep Learning for Polymer Discovery

The unique periodicity of polymer structures has traditionally challenged machine learning models.

Objective: To develop a deep learning framework that accurately represents the periodic nature of polymers for property prediction and material discovery [13].

Methodology - The PerioGT Framework: This novel framework integrates chemical knowledge-driven periodicity priors into its architecture.

- Pre-training with Contrastive Learning: The model is pre-trained using contrastive learning techniques that emphasize the periodic nature of polymers, building a foundational understanding of how periodicity influences properties [13].

- Fine-Tuning with Periodicity Prompts: In the fine-tuning phase, the model learns periodicity prompts based on the established prior, enhancing its focus on periodic attributes [13].

- Graph Augmentation: An innovative graph augmentation strategy using virtual nodes allows the model to integrate additional conditions and model complex chemical interactions [13].

Key Findings:

- PerioGT demonstrated state-of-the-art performance across 16 different downstream tasks.

- Its real-world applicability was validated through wet-lab experiments, where it successfully identified two novel polymers with potent antimicrobial properties [13].

Research Reagents and Materials Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Featured Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(ethylene-co-1-hexene) | Model short-chain branched polyethylene for studying the effect of branching on semi-crystalline morphology and mechanical performance [11]. | Single-site metallocene-catalyzed; narrow molar mass distribution; specified butyl branch content (e.g., 1.0, 1.8, 2.7 mol.%) [11]. |

| pBTTT (Polymer) | A model conjugated polymer for investigating the relationship between processing, doping, structure, and electronic charge transport properties [12]. | -- |

| F4TCNQ (Dopant) | A molecular p-type doping agent used to introduce charge carriers into the conjugated polymer matrix, modifying its electronic properties [12]. | -- |

| Monte Carlo Simulation Code | Computational tool for simulating chain behavior in amorphous and semi-crystalline phases and quantifying topological features [11]. | Implements algorithms like the "Nilsson model" for tie chain and trapped entanglement calculation [11]. |

| AI/ML Framework (PerioGT) | A specialized deep learning framework for polymer informatics that incorporates periodicity as a prior knowledge, improving property prediction and material discovery [13]. | Uses graph-based models with contrastive learning and periodicity prompts [13]. |

Structural Visualization of Polymer Morphologies

The following diagram illustrates the key architectural differences between amorphous and semi-crystalline polymers, highlighting the roles of chain entanglement and lamellae formation.

Diagram: Amorphous vs. Semi-Crystalline Polymer Architecture. This graph contrasts the disordered, entangled structure of amorphous polymers with the ordered lamellae stacks of semi-crystalline polymers. It highlights key features such as the glass transition (Tg) in amorphous materials and critical inter-lamellar connections like tie chains and trapped entanglements in semi-crystalline materials that govern mechanical integrity.

The molecular architecture of polymers—specifically, the dichotomy between random chain entanglement in amorphous regions and ordered lamellae stacks in crystalline domains—forms the foundational principle governing material performance. The properties of a polymer, from its mechanical strength and thermal behavior to its chemical resistance, are direct consequences of this nanoscale structure. Modern research leverages sophisticated tools, from Monte Carlo simulations that quantify critical topological features like tie chains, to AI-guided high-throughput experimentation and periodicity-aware deep learning models that accelerate the discovery of polymers with tailored properties. Understanding and controlling this molecular architecture is therefore paramount for the rational design of next-generation polymeric materials for advanced applications in drug development, bioelectronics, and sustainable technology.

In polymer science, the concept of crystallinity represents a fundamental structural parameter that profoundly influences material properties and performance. Unlike small-molecule compounds that exhibit distinct solid, liquid, and gaseous states, polymers demonstrate more complex structural behavior classified along a spectrum from completely amorphous to highly crystalline forms [1]. This spectrum is quantified as the degree of crystallinity, which describes the weight or volume fraction of crystalline material within a polymeric substance, ranging from 0% (entirely amorphous) to 100% (perfectly crystalline), though most practical polymers fall somewhere between these extremes [1]. The arrangement of polymer chains dictates this structural organization: amorphous regions feature randomly entangled and coiled molecular chains lacking long-range order, while crystalline regions exhibit chains folded into orderly stacks known as lamellae with predictable, repeating patterns [1].

The crystallinity spectrum provides a crucial framework for understanding polymer behavior, particularly within materials research and drug development where structural characteristics directly influence mechanical properties, chemical stability, degradation profiles, and bioavailability. For pharmaceutical applications, the amorphous-crystalline balance can determine dissolution rates, solubility, and ultimately drug efficacy. This technical guide examines the fundamental principles, characterization methodologies, and practical implications of crystallinity in polymeric systems, with specific emphasis on experimental protocols and quantitative analysis techniques relevant to research scientists.

Theoretical Foundations: Structural Organization in Polymers

Molecular Architecture of Crystalline and Amorphous Regions

The structural differences between crystalline and amorphous polymers originate at the molecular level. In amorphous polymers, atoms are held together in a loose, unpredictable structure without long-range order, much like a tangled mass of cooked spaghetti [1]. This molecular configuration creates materials that are typically transparent, softer, and more flexible than their crystalline counterparts. When heated, amorphous polymers do not melt at a specific temperature but gradually transition from a hard, glassy state to a soft, rubbery state at what is known as the glass transition temperature (Tg) [1].

In contrast, crystalline polymers contain regions where molecular chains align in highly ordered, repeating patterns. These crystalline zones coexist with amorphous regions in a semi-crystalline structure [3]. The crystalline domains form orderly stacks of folded chains called lamellae, which bring long-range order to the polymer [1]. This molecular organization creates materials that are generally opaque, stiffer, and more resistant to chemicals and heat. Highly crystalline polymers have a definite melting point (Tm) where their orderly arrangement transitions to a random, disorganized state [1].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Amorphous and Crystalline Polymers

| Characteristic | Amorphous Polymers | Crystalline Polymers |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Structure | Randomly arranged chains, no long-range order | Ordered, repeating patterns with lamellae formation |

| Transparency | Typically transparent | Typically opaque or translucent |

| Thermal Behavior | Glass transition temperature (Tg), no sharp melting point | Definite melting point (Tm) |

| Mechanical Properties | Softer, more flexible | Harder, stiffer, more brittle |

| Chemical Resistance | More susceptible to solvent penetration | High resistance due to tight molecular packing |

| Density | Lower density | Higher density |

| Processing Shrinkage | Minimal shrinkage | Significant shrinkage during cooling |

Factors Influencing Crystallinity

Several molecular and processing factors determine where a polymer falls on the crystallinity spectrum:

- Chain flexibility: Both flexing along the entire chain and flexing in bonds between atoms plays a significant role in polymer crystal formation [1].

- Molecular branching: Polymers with long branches (like LDPE) do not pack well into crystals, resulting in lower crystalline fractions and higher free volume compared to more linear chains (like HDPE) [14].

- Tacticity: The arrangement of pendant groups along the polymer backbone significantly impacts crystallinity. Isotactic and syndiotactic polymers (with ordered pendant groups) tend to be crystalline, while atactic polymers (with randomly arranged pendant groups) are generally amorphous [1].

- Processing conditions: Cooling rates, annealing procedures, and mechanical stretching during processing can dramatically influence crystallinity development [15].

Quantitative Measurement of Crystallinity

Established Characterization Techniques

Accurately determining a polymer's position on the crystallinity spectrum requires specialized analytical techniques, each with distinct principles and applications.

X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

XRD is the most widely employed method for crystallinity determination, particularly for cellulose materials [16]. The technique analyzes diffraction patterns generated when X-rays interact with the periodic structures of crystalline domains. For polyethylene, characteristic diffraction peaks appear at q = 1.51 Å⁻¹ (110) and 1.67 Å⁻¹ (200), with peak shifts under compression indicating changes in unit cell volume [14]. The most common XRD approach is the Segal peak height method, which calculates the Crystallinity Index (CrI) using the formula: CrI = (I₂₀₀ - Iₐₘ)/I₂₀₀ × 100%, where I₂₀₀ represents the intensity of the 200 crystalline peak and Iₐₘ the intensity of the amorphous background [16]. However, this method provides only a rough approximation, as the minimum intensity position used for Iₐₘ does not always correspond to the actual maximum of the amorphous peak [16].

Experimental Protocol: XRD Crystallinity Measurement

- Sample Preparation: Prepare polymer samples as thin films or powdered specimens mounted on standard XRD holders.

- Instrument Calibration: Use a polycrystalline silicon standard to calibrate sample-to-detector distance and q-range.

- Data Collection: Expose samples to X-ray beam (typically Cu Kα radiation, λ = 1.5406 Å) with parameters set to 40 kV and 40 mA. Scan 2θ range from 5° to 40° with step size of 0.02° and counting time of 2 seconds per step.

- Pattern Analysis: Identify crystalline peaks and amorphous halo in the diffraction pattern.

- Crystallinity Calculation: Apply peak deconvolution methods or the Segal method to determine crystalline and amorphous fractions.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

Solid-state ¹³C NMR provides complementary crystallinity information by analyzing the chemical environment of carbon atoms. For cellulose, crystallinity is typically estimated based on the spectral region assigned to the C-4 carbon [16]. The technique relies on spectral deconvolution to distinguish signals from crystalline and amorphous regions, though this presents inherent limitations due to multiple possible ways to resolve overlapping peaks [16]. Recent advances have also utilized ¹⁹F low-field NMR relaxometry for characterizing crystallinity in fluoropolymers, offering an alternative approach for specialized applications [17].

Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy

FT-IR spectroscopy offers a rapid, complementary approach for crystallinity estimation based on vibrational band intensity ratios. For cellulose, characteristic bands include:

- 1429 cm⁻¹: "Crystallinity band" from asymmetric CH₂ bending vibrations

- 893 cm⁻¹: "Amorphous band" from C-O-C stretching of β-(1→4)-glycosidic linkages

- 1372 cm⁻¹: CH bending vibrations (crystallinity indicator)

- 2900 cm⁻¹: CH stretching vibrations (amorphous characteristic) [16]

The Total Crystallinity Index (TCI) is calculated as the intensity ratio of the 1372 cm⁻¹ and 2900 cm⁻¹ bands [16]. While FT-IR provides valuable chemical bonding information, it is highly sensitive to sample thickness, density, and measurement conditions, limiting its accuracy as a standalone quantitative method [16].

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

DSC determines crystallinity by measuring the heat flow associated with polymer melting transitions. The degree of crystallinity (Xc) is calculated using the formula: Xc = (ΔHf/ΔHf⁰) × 100%, where ΔHf is the measured enthalpy of fusion and ΔHf⁰ is the theoretical enthalpy of fusion for a 100% crystalline polymer. DSC also provides glass transition temperatures (Tg) for amorphous regions and melting points (Tm) for crystalline domains.

Emerging Approaches: Machine Learning-Enhanced Analysis

Recent advances have integrated spectroscopic methods with machine learning algorithms to improve crystallinity estimation accuracy. For cellulose materials, machine learning models trained on IR spectroscopy data have demonstrated enhanced capability in predicting crystallinity compared to traditional heuristic peak assignment approaches [16]. These models employ feature contribution analysis to identify informative spectral variables and can be applied to diverse cellulose-containing materials, including wood pulps, microcrystalline cellulose, and cellulose nanomaterials [16]. This approach represents a paradigm shift from isolated band analysis to comprehensive spectral profiling, potentially overcoming limitations of conventional FT-IR crystallinity assessment.

Table 2: Comparison of Crystallinity Measurement Techniques

| Technique | Principle | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) | Analysis of crystalline diffraction patterns | Most widely used method; suitable for various polymers | Requires crystalline standards; complex data interpretation |

| Solid-State NMR | Spectral differentiation of crystalline and amorphous carbon environments | Cellulose crystallinity; polymer microstructure | Limited sensitivity; complex instrumentation |

| FT-IR Spectroscopy | Absorbance ratio of crystalline vs. amorphous bands | Rapid screening; chemical bonding information | Sensitive to measurement conditions; semi-quantitative |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Measurement of melting enthalpies | Thermal behavior analysis; widely accessible | Requires reference values; thermal history effects |

| Machine Learning + Spectroscopy | Multivariate analysis of spectral features | High-throughput screening; complex materials | Model training required; limited interpretability |

Experimental Protocols for Crystallinity Analysis

Sample Preparation Standards

Consistent sample preparation is critical for reliable crystallinity measurements. For XRD analysis, polymer specimens should be processed as flat sheets or compressed powders to ensure uniform diffraction geometry. For transmission-based techniques like FT-IR, sample thickness should be optimized to achieve absorbance values in the linear range of the Beer-Lambert law (typically 0.3-0.8 AU). For comparative studies, all samples should undergo identical thermal history and conditioning protocols to minimize processing-induced crystallinity variations.

Reference Material Preparation

Accurate crystallinity quantification requires appropriate reference materials. For cellulose crystallinity assessment, common standards include:

- Microcrystalline cellulose (MCC): Crystalline standard with average particle size of 50μm [16]

- Ball-milled cellulose: Amorphous reference prepared by planetary milling with zirconia balls [16]

- Xylan and lignin powders: Additional amorphous standards for mixture models [16]

Binary mixtures of crystalline and amorphous standards in known proportions can establish calibration curves for quantitative crystallinity determination.

Crystallinity-Property Relationships in Polymeric Systems

Mechanical Performance

Crystallinity profoundly influences polymer mechanical behavior. Highly crystalline polymers like PTFE, PEEK, and UHMWPE exhibit superior tensile strength, stiffness, and dimensional stability [3]. The crystalline regions act as physical crosslinks, enhancing load transfer and resistance to deformation. Under dynamic loading, crystalline polymers like polyethylene demonstrate chain alignment parallel to the shock direction, with diffraction studies revealing anisotropic reorganization during compression [14]. In contrast, amorphous polymers such as PEI and polyimide tend toward greater flexibility, reduced brittleness, and higher resistance to stress cracking [3].

The relationship between crystallinity and mechanical properties is particularly evident in polyethylene variants. UHMWPE, with long linear chains that effectively transfer load to the polymer backbone, demonstrates exceptional impact resistance despite having lower density than HDPE due to increased free volume from extended chains [14]. LDPE, with its long-chain branching that inhibits crystal packing, exhibits lower crystalline fractions and consequently different mechanical responses under compression [14].

Thermal Behavior

Thermal properties show perhaps the most direct correlation with crystallinity. Highly crystalline polymers display sharp melting points (Tm) due to their ordered structure, while amorphous polymers lack definite melting points and instead undergo glass transitions (Tg) over a temperature range [1]. For example, crystalline polymers like PVDF retain strength and stability at elevated temperatures, while amorphous polymers like PVC soften gradually, allowing versatile processing [3].

Table 3: Thermal Transitions of Common Polymers by Crystallinity Type

| Polymer | Type | Tg (°C) | Tm (°C) | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTFE | Crystalline | ~127 | ~327 | Seals, filters, non-stick coatings |

| PEEK | Crystalline | ~143 | ~343 | Aerospace, medical implants |

| UHMWPE | Crystalline | ~-100 | - | Wear-resistant components, artificial joints |

| PVDF | Crystalline | ~-35 | ~177 | Piping, chemical processing |

| PA66 | Crystalline | ~70 | ~255 | Automotive parts, textiles |

| PEI | Amorphous | ~215 | None | Aerospace, medical applications |

| Polyimide | Amorphous | ~250 | None | Electronics, flexible circuits |

| PVC | Amorphous | ~85 | None | Construction, healthcare tubing |

Chemical Resistance and Barrier Properties

Crystalline polymers generally exhibit superior chemical resistance due to their tight molecular packing, which limits solvent penetration and diffusion [3]. PTFE represents an extreme example, with exceptional chemical inertness making it ideal for harsh environments [3]. Recent developments in two-dimensional polymers like 2D polyaramid (2DPA-1) have demonstrated unprecedented barrier properties, with nitrogen permeability below 3.1 × 10⁻⁹ Barrer - nearly four orders of magnitude lower than conventional polymers and approaching the impermeability of graphene [18]. These materials achieve molecular impermeability through layered, orientational ordering with interlayer spacing of 3.3±0.2Å, effectively eliminating free volume between monolayers [18].

Optical Characteristics

The structural organization of polymers directly affects their optical properties. Amorphous polymers typically offer high transparency due to their homogeneous structure at the molecular level, which minimizes light scattering. In contrast, crystalline polymers are generally opaque or translucent because the refractive index differences between crystalline and amorphous regions scatter visible light. This property relationship makes amorphous polymers preferable for applications requiring optical clarity, while crystalline polymers dominate where opacity is acceptable or desirable.

Advanced Applications and Emerging Research Frontiers

Two-Dimensional Amorphous Materials

Recent breakthroughs in two-dimensional amorphous materials approaching the single-layer limit have revealed unique disorder-dominated properties with significant implications for electronics, catalysis, and energy applications [19]. These ultra-thin amorphous systems exhibit distinctive structural descriptors including local bonding variations, topological disorder characterized by parameters like disordered hyperuniformity (DHU) and ring statistics, and flexible chemical composition [19]. Monolayer amorphous carbon (MAC), for instance, demonstrates remarkable mechanical strength and tunable electrical conductivity dependent on synthesis temperature, with materials produced at 300°C showing electrical conductivity nine orders of magnitude higher than those synthesized at 400°C [19].

Crystalline Two-Dimensional Conjugated Polymers

The synthesis of crystalline two-dimensional conjugated polymers (2DCPs) via irreversible chemistry under mild conditions represents another frontier in polymer crystallinity research [20]. These materials feature long-range molecular ordering, robust olefin linkages, and well-controlled thickness from monolayer to multilayer architectures [20]. The pre-assembly of trimethylpyridinium monomers at water interfaces significantly enhances condensation reactivity, enabling crystalline 2DCP formation under ambient conditions [20]. Such advances highlight how molecular organization strategies can overcome traditional crystallinity limitations.

Multi-Material 3D Printing via Crystallinity Control

Innovative manufacturing approaches exploit crystallinity control for multi-material 3D printing from single formulations. By adjusting printing temperature and light intensity, researchers can selectively produce semi-crystalline or amorphous domains within a single printed part [15]. Using liquid crystalline monomers that form highly stable phases with trifunctional thiol crosslinkers, this approach achieves pixel-to-pixel resolution of material properties guided solely by printing parameters [15]. The technique enables fabrication of complex structures with spatially controlled crystallinity for shape memory applications, data storage, and encryption systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful crystallinity research requires specialized materials and analytical tools. The following table summarizes key resources for experimental investigations of polymer crystallinity.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Crystallinity Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) | Crystalline standard for calibration | Average particle size ~50μm [16] |

| Ball-milled Cellulose | Amorphous reference material | Prepared by planetary milling with zirconia balls [16] |

| Xylan & Lignin Powders | Amorphous standards for mixture models | Commercial purity grades [16] |

| Polycrystalline Silicon | XRD calibration standard | Certified reference material |

| Deuterated Solvents | NMR spectroscopy | DMSO-d6, CDCl3 for polymer dissolution |

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | FT-IR pellet preparation | FT-IR grade, purified |

| Langmuir-Blodgett Trough | 2D polymer monolayer assembly | Precision temperature control [20] |

| Trimethylpyridinium Monomers | 2D conjugated polymer synthesis | Alkyl-quaternized for interfacial polycondensation [20] |

| Liquid Crystalline Monomers | Multi-material 3D printing | Smectic X phase with sharp LC-isotropic transition [15] |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Comprehensive Workflow for Polymer Crystallinity Characterization. This workflow integrates multiple analytical techniques with machine learning enhancement for robust crystallinity quantification.

The spectrum of crystallinity from 0% to 100% provides a fundamental framework for understanding and engineering polymer properties. As characterization methodologies advance from traditional XRD to machine learning-enhanced spectroscopy, and synthesis techniques evolve toward two-dimensional polymers with controlled disorder, researchers gain unprecedented capability to tailor materials for specific applications. For pharmaceutical scientists, these developments offer new pathways to optimize drug delivery systems through precise crystallinity control, balancing stability, dissolution, and bioavailability. The continuing investigation of crystallinity relationships across material classes promises to unlock further innovations in polymer science and drug development.

Within polymer science, the concepts of the Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) and the Melting Point (Tm) are fundamental to understanding material behavior. These thermal transitions are not merely data points but are direct consequences of a polymer's molecular architecture, dictating its mechanical properties, processing conditions, and ultimate application suitability. Framed within the critical context of amorphous versus crystalline polymer structures, this guide delves into the distinct nature of Tg and Tm. For researchers and drug development professionals, a precise grasp of these transitions is indispensable for tasks ranging from selecting a polymer for a drug-delivery matrix to predicting the long-term stability of a medical device. The transition temperatures are not intrinsic material constants in the strictest sense but are influenced by molecular weight, thermal history, and the presence of additives, making their accurate measurement and interpretation a cornerstone of polymeric material science [21] [22].

Defining the Fundamental Transitions

Glass Transition Temperature (Tg)

The Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) is the critical temperature range below which an amorphous polymer or the amorphous regions of a semi-crystalline polymer behave as a rigid, glassy solid, and above which they become soft, flexible, and rubbery [23] [22]. This is a second-order transition, meaning it is not a true phase change between states of thermodynamic equilibrium but rather a kinetic and reversible change in the physical properties of the material [21] [22]. At the molecular level, below the Tg, the polymer chains are frozen in place, lacking the thermal energy for large-scale segmental motion. As the temperature surpasses the Tg, the chains gain sufficient mobility to begin sliding past one another, leading to the rubbery state [23] [24]. This transition dramatically alters key properties, including hardness, elasticity, volume, and thermal expansion coefficient [22].

Melting Temperature (Tm)

The Melting Temperature (Tm), in contrast, is the temperature at which the crystalline regions of a polymer melt, transitioning from an ordered solid to a disordered liquid state [21] [25]. This is a first-order transition, characterized by an abrupt, discontinuous change in properties and the absorption of latent heat [21] [26]. Tm is a property of the crystalline regions within a polymer. When heated to Tm, the highly ordered, stable crystalline structure breaks down as the polymer chains gain enough energy to overcome the intermolecular forces holding the crystal lattice together, resulting in a viscous liquid [23] [1]. It is crucial to note that 100% amorphous polymers do not possess a Tm, as they lack any crystalline structure to melt [21].

Comparative Analysis: Tg vs. Tm

The distinction between Tg and Tm is foundational to polymer morphology. The following diagram illustrates the relationship between polymer structure and its thermal transitions.

The core differences between these two transitions are systematized in the table below.

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Tg and Tm

| Characteristic | Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) | Melting Temperature (Tm) |

|---|---|---|

| Governing Principle | Onset of segmental motion in amorphous regions [21] [23] | Dissociation of the crystalline lattice [21] [26] |

| Order of Transition | Second-order (change in slope of properties) [21] [22] | First-order (discontinuity in properties) [21] [26] |

| Molecular Process | Chains gain mobility; transition from frozen to rubbery state [23] [24] | Crystalline structure is lost; transition from solid to liquid melt [21] [1] |

| Physical State Change | Glassy solid Rubbery/Viscous state [22] [27] | Crystalline Solid Isotropic Liquid [25] [26] |

| Dependence on Crystallinity | Property of amorphous regions [21] [1] | Property of crystalline regions [21] [1] |

Factors Influencing Tg and Tm

The specific values of Tg and Tm for a given polymer are not fixed but can be tuned by altering its chemical and physical structure. Understanding these factors is key for material design.

Table 2: Factors Affecting Tg and Tm

| Factor | Effect on Tg | Effect on Tm |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | Increases with molecular weight due to decreased chain-end free volume [23] | Generally increases with molecular weight [23] |

| Chain Stiffness / Rigidity | Increases with rigid backbone chains and bulky side groups [23] [27] | Increases with chain stiffness and restricted rotation [26] |

| Intermolecular Forces | Increases with strong polar groups and high cohesion [23] | Increases with strong intermolecular forces [26] |

| Cross-Linking | Increases significantly by restricting chain motion [23] [28] | Increases; highly cross-linked thermosets decompose before melting [24] |

| Plasticizers | Decreases by increasing free volume and chain mobility [23] [27] | Can be depressed, though less pronounced effect than on Tg [23] |

| Crystallinity | The amorphous regions undergo Tg; higher crystallinity can restrict mobility [27] [28] | Directly corresponds to the melting of the crystalline regions [1] |

| Branching | Random (atactic) branching typically decreases Tg [23] | Can depress Tm by disrupting crystal perfection [23] |

Experimental Determination of Thermal Transitions

Accurately measuring Tg and Tm requires specific and sensitive thermal analysis techniques. The following experimental workflow outlines the primary methods used.

Key Measurement Techniques

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): This is a primary technique where the heat flow into a sample and a reference is monitored as a function of temperature or time. Tg is identified as a step change in the heat flow curve due to a change in heat capacity, while Tm is identified as a distinct endothermic peak as the crystals melt [23] [27]. Standard test methods include ASTM D3418 and ISO 11357-2 [23].

- Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA): DMA is exceptionally sensitive for detecting Tg. It applies a oscillating stress to the sample and measures the resulting strain. The Tg is marked by a dramatic drop in the storage modulus (stiffness) and a peak in the loss modulus (damping), providing information on the mechanical manifestation of the transition [23] [22]. A standard method is ASTM E1640 [23].

- Differential Thermal Analysis (DTA): Similar to DSC, DTA measures the temperature difference between a sample and a reference material under controlled heating. Thermal transitions like Tg and Tm appear as deviations in the temperature difference plot [23].

- Thermomechanical Analysis (TMA): TMA measures dimensional changes in a polymer as it is heated. The Tg is observed as a change in the coefficient of thermal expansion, as the polymer transitions from a glassy to a rubbery state [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions and Materials for Thermal Analysis

| Item | Function / Relevance in Research |

|---|---|

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter | The core instrument for measuring heat flow associated with Tg and Tm transitions; essential for quality control and polymer identification [23] [27]. |

| Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer | Instrument for characterizing the viscoelastic properties of polymers; provides the most sensitive measurement of the mechanical glass transition [23] [27]. |

| Hermetic Sealed Crucibles | Sample pans for DSC that prevent volatile loss from the polymer sample during heating, ensuring data integrity [23]. |

| Inert Reference Materials | High-purity materials like alumina used as references in DSC and DTA to baseline the instrument's heat flow [23]. |

| Plasticizers (e.g., phthalates) | Chemical additives used to deliberately lower the Tg of a polymer system, increasing its flexibility and processability [23] [28]. |

| Cross-Linking Agents (e.g., peroxides) | Reagents used to create covalent bonds between polymer chains, increasing Tg and thermal stability [23] [28]. |

| High-Purity Polymer Standards | Materials with certified Tg and Tm values used for calibration and validation of thermal analysis equipment [23]. |

Tg and Tm Data for Common Polymers

The following table provides the thermal transition values for a selection of polymers relevant to industrial and research applications, illustrating the wide range of properties achievable.

Table 4: Glass Transition and Melting Temperatures of Selected Polymers

| Polymer | Abbreviation | Polymer Type | Tg (°C) | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyisoprene (Natural Rubber) | PIP | Amorphous | -70 [22] | - |

| Polyethylene (High Density) | HDPE | Semi-crystalline | -120 [24] [28] | 137 [1] |

| Polypropylene (atactic) | PP | Amorphous | -20 to -17 [22] [1] | - |

| Polypropylene (isotactic) | PP | Semi-crystalline | 0 [22] | 174 [1] |

| Poly(vinyl acetate) | PVAc | Amorphous | 30 [22] | - |

| Poly(ethylene terephthalate) | PET | Semi-crystalline | 70 [22] [27] | 250 [27] |

| Poly(vinyl chloride) | PVC | Amorphous | 80 [22] | - |

| Polystyrene | PS | Amorphous | ~100 [22] [24] [28] | - |

| Poly(methyl methacrylate) | PMMA | Amorphous | ~105 [22] | - |

| Polycarbonate | PC | Amorphous | ~145 [24] [28] | - |

| Polyetheretherketone | PEEK | Semi-crystalline | 140 [24] | 340* |

| Polyetherimide | PEI | Amorphous | 210 [24] [28] | - |

*Note: Tm value for PEEK is from general scientific knowledge, as the provided search results did not contain it.

The distinction between the glass transition temperature (Tg) and the melting point (Tm) is a fundamental paradigm in polymer science, rooted in the amorphous and crystalline morphological structures of these materials. Tg, a second-order transition governing the rubbery state, and Tm, a first-order transition governing the crystalline melt, collectively define the thermal and mechanical performance window of any polymeric material. For researchers and scientists, particularly in demanding fields like drug development, a deep understanding of these transitions—and the factors that modulate them—is not merely academic. It is the bedrock of rational material selection, predictive performance modeling, and the innovative design of advanced polymeric systems tailored to specific technological and therapeutic challenges.

The properties of polymeric materials are profoundly influenced by their hierarchical structure, ranging from the molecular to the macroscopic scale. Within the context of amorphous versus crystalline polymer structures, the tacticity of a polymer—the stereochemical arrangement of pendant groups along the macromolecular backbone—serves as a critical determinant of its ultimate physical characteristics and application potential [29]. Tacticity arises when a polymer chain contains asymmetric carbon atoms, typically from the polymerization of vinyl monomers (CH2=CHX) [29]. The precise control over this stereoregularity enables materials scientists to tailor polymers for specific needs, from commodity plastics to advanced drug delivery systems.

At the most fundamental level, tacticity governs the ability of polymer chains to pack into ordered, crystalline regions or to remain in a disordered, amorphous state [30]. Isotactic and syndiotactic configurations, with their regular structures, facilitate chain alignment and crystallinity, leading to materials with enhanced mechanical strength, thermal resistance, and chemical stability [29] [30]. In contrast, atactic polymers, with their random stereochemistry, typically form amorphous glasses with lower strength and higher permeability but often with greater transparency [2] [30]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of how tacticity influences polymer structure-property relationships, with particular emphasis on implications for pharmaceutical and materials research.

Defining Tacticity Configurations

Structural Isomerism in Polymers

Tacticity refers to the spatial arrangement of pendant groups (X) along the polymer backbone derived from vinyl monomers [29]. This configuration is determined during the polymerization process as each new monomer adds to the growing chain. The classification is based on the arrangement of consecutive stereocenters:

- Isotactic: Pendant groups are consistently located on the same side of the polymer backbone when viewed in a planar projection. This corresponds to a meso (m) diad placement between consecutive monomer units [29] [31].

- Syndiotactic: Pendant groups alternate regularly from one side to the other along the chain, corresponding to a racemic (r) diad placement [29] [31].

- Atactic: Pendant groups are arranged randomly along the polymer backbone with no discernible pattern, resulting in a statistical mixture of diad types [29].

The regularity of isotactic and syndiotactic structures enables long-range order and crystallinity, whereas the randomness of atactic structures generally prevents crystallization [30]. For a sequence of three monomer units (a triad), isotactic triads are denoted mm, syndiotactic triads rr, and heterotactic triads mr [31]. The relative prevalence of these triad sequences quantifies the overall tacticity of a polymer chain.

Historical Context and Significance

The profound implications of tacticity on polymer properties were first systematically recognized through the work of Giulio Natta in 1954 [30]. Natta's investigation of polypropylene demonstrated that the stereoregularity of the polymer chain dramatically influenced its physical characteristics. This discovery, building upon Karl Ziegler's catalyst systems, led to the development of stereospecific polymerization methods that could control the tacticity of the resulting polymers [29] [30]. The commercial impact of this discovery was monumental, creating what has been described as a "billion dollar industry" based on stereoregular polymers [29].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Tacticity Configurations

| Configuration | Stereochemical Pattern | Diad/Triad Notation | Degree of Order | Crystallization Tendency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isotactic | All pendant groups on same side | m diad, mm triad | High long-range order | High |

| Syndiotactic | Alternating pendant groups | r diad, rr triad | Medium-to-high order | Moderate to high |

| Atactic | Random placement of pendant groups | Random m/r | Low order | Low |

Influence of Tacticity on Crystallinity and Physical Properties

Mechanisms of Crystallization in Stereoregular Polymers

The ability of polymer chains to organize into crystalline domains is fundamentally dependent on their stereoregularity [32]. Isotactic and syndiotactic polymers can form ordered structures because their regular configurations allow chains to align parallel to one another and fold into lamellae [2] [33]. These lamellae further organize into larger superstructures called spherulites, which can range from 1 to 100 micrometers in size [32]. In contrast, the irregular structure of atactic polymers prevents this orderly packing, resulting in predominantly amorphous materials [30].

The crystallization process involves nucleation followed by crystal growth [32]. Nucleation begins with small, nanometer-sized areas where chain segments align through thermal motion. These nuclei must reach a critical size to become stable before further growth can occur. For stereoregular polymers like isotactic polypropylene, crystal growth proceeds through the addition of folded polymer chain segments at temperatures between the glass transition (Tg) and melting temperature (Tm) [32]. The resulting crystalline regions act as physical crosslinks, significantly enhancing the mechanical properties of the material.

Comparative Physical Properties

The dramatic effect of tacticity on polymer properties is exemplified by polypropylene [30]. Atactic polypropylene is soft, elastic, somewhat sticky, and soluble in many organic solvents at room temperature. In contrast, isotactic polypropylene is a hard, strong crystalline polymer with a melting point of 175°C, and it is practically insoluble in all organic solvents at room temperature [30]. This striking difference originates solely from the configuration of the methyl groups attached to the polymer backbone.

The melting point difference between isotactic polypropylene (175°C) and polyethylene (110°C), despite the similarity in their chemical structures, arises from their different crystallization patterns [30]. While polyethylene forms extended zig-zag chains, isotactic polypropylene must form helical structures to accommodate the steric demands of the methyl groups. These helical coils are more rigid and exhibit stabilizing interchain interactions, thus requiring higher temperatures for melting [30].

Table 2: Property Comparison of Polypropylene Tacticity Variants

| Property | Atactic Polypropylene | Isotactic Polypropylene |

|---|---|---|

| State at Room Temperature | Soft, elastic, somewhat sticky | Hard, strong, rigid |

| Crystallinity | Amorphous (~0%) [32] | Highly crystalline (70-80%) [32] |

| Melting Point | No sharp melting point | 175°C [30] |

| Solubility | Soluble in solvents like tetrachloroethane | Insoluble in most solvents at room temperature |

| Optical Properties | Transparent | Translucent |

| Typical Applications | Adhesives, sealants | Detergent bottles, automotive parts, fibers |

Quantitative Impact of Tacticity on Polymer Behavior

Research on poly(methacrylic acid) (PMA) has quantitatively demonstrated how subtle changes in tacticity influence polymer behavior [31]. Studies comparing atactic and syndiotactic PMAs with slightly increasing amounts of rr triads (from 60% to 80%) revealed significant differences in solution conformation and interfacial behavior. Syndiotactic PMA with higher rr triad content showed a pronounced maximum in Small-Angle Neutron Scattering (SANS) profiles at pH 5.5, suggesting the presence of ordered conformations and/or aggregates not detectable in the atactic form [31].

Furthermore, the tacticity affected interactions with cationic surfactants like DTAB. Polymers with higher syndiotacticity demonstrated stronger interactions with surfactant micelles, which could significantly impact their performance in drug delivery applications where membrane interactions are crucial [31]. These findings underscore that even relatively small changes in triad content can cause measurable changes in solution and interfacial behavior that could impact biological properties when used as polymeric excipients or polymer therapeutics.

Experimental Characterization Methods

Determining Tacticity and Crystallinity

Several analytical techniques are employed to characterize polymer tacticity and its resulting effect on crystallinity:

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: ¹³C NMR is particularly powerful for determining tacticity, as it can distinguish between the different configurational sequences in polymer chains [30]. The chemical shifts of backbone carbons are sensitive to their stereochemical environment, allowing quantification of mm, mr, and rr triads.

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): DSC measures thermal transitions in polymers, including the glass transition temperature (Tg) and melting point (Tm) [2]. The enthalpy of fusion measured during melting can be used to calculate the degree of crystallinity by comparing it to the value for a 100% crystalline reference material.

- X-Ray Diffraction (XRD): Wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) can distinguish between crystalline and amorphous regions based on their diffraction patterns [32]. Crystalline regions produce sharp diffraction peaks, while amorphous regions result in broad halos.

- Density Measurements: Crystalline regions are typically more densely packed than amorphous areas, leading to density differences up to 15% depending on the material [32]. Density gradient columns provide a simple method to estimate crystallinity based on this principle.

Advanced Characterization Techniques

For more detailed structural analysis, several advanced techniques provide additional insights:

- Small-Angle Neutron Scattering (SANS): Used to study polymer conformation in solution and how tacticity influences chain dimensions and aggregation behavior [31].

- Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA): Measures the viscoelastic properties of polymers as a function of temperature, providing information on stiffness (modulus) and damping characteristics across transitions [2].

- Polarized Light Microscopy: Visualizes spherulitic structures in semi-crystalline polymers, allowing observation of crystal growth and morphology [32].

Diagram 1: Polymer Tacticity and Crystallinity Characterization Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Tacticity Analysis

Protocol 1: Tacticity Determination via ¹³C NMR Spectroscopy

Objective: To determine the relative proportions of isotactic (mm), heterotactic (mr), and syndiotactic (rr) triads in a polymer sample.

Materials and Equipment:

- Polymer sample (≥10 mg)

- Deuterated solvent appropriate for the polymer (e.g., deuterated chloroform, DMSO-d6)

- NMR tubes

- High-resolution NMR spectrometer (300 MHz or higher)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve 10-15 mg of polymer in 0.6 mL of deuterated solvent. Filter if necessary to remove insoluble impurities.