AI and Machine Learning in Polymer Optimization: A New Paradigm for Drug Development

This article explores the transformative role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) in optimizing polymers for pharmaceutical and biomedical applications.

AI and Machine Learning in Polymer Optimization: A New Paradigm for Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) in optimizing polymers for pharmaceutical and biomedical applications. It provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of AI in polymer science, key methodologies like supervised learning and graph neural networks for property prediction, and strategies to overcome critical challenges such as data scarcity and model interpretability. The content further examines the validation of AI tools through case studies and benchmarks their performance against traditional methods, concluding with a forward-looking perspective on the future of AI-driven polymer discovery in clinical research.

The AI Revolution in Polymer Science: Foundations and Core Concepts

Shifting from Trial-and-Error to a Data-Driven Paradigm in Polymer Research

The development of polymer composites has long been reliant on traditional trial-and-error methods that are often time-consuming and resource-intensive [1]. Today, artificial intelligence and machine learning are revolutionizing this field by enabling data-driven insights into material design, manufacturing processes, and property prediction [1]. This technical support center provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with practical guidance for implementing AI-driven approaches in their polymer research workflows, addressing common challenges, and providing troubleshooting for specific experimental issues.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary advantages of replacing traditional polymer research methods with AI-driven approaches?

AI-driven approaches offer multiple advantages over traditional methods. Machine learning algorithms can analyze large datasets, identify complex patterns, and make accurate predictions without the need for extensive physical testing [1]. This significantly accelerates material discovery and optimization cycles. For instance, companies like CJ Biomaterials have utilized AI platforms such as PolymRize to quickly assess the performance of new PHACT materials, enabling faster decision-making while reducing time and costs compared to traditional methods [2].

Q2: What types of machine learning techniques are most effective for polymer property prediction?

Multiple ML techniques have shown effectiveness in polymer informatics. Supervised learning algorithms are commonly used for property prediction tasks, while unsupervised learning can help identify patterns in unlabeled data. Deep learning approaches offer enhanced capabilities for handling complex, high-dimensional data [1]. For specific polymer property prediction, comprehensive ML pipelines have been developed that implement the CRISP-DM methodology with advanced feature engineering to predict key properties including glass transition temperature (Tg), fractional free volume (FFV), thermal conductivity (Tc), density, and radius of gyration (Rg) [3].

Q3: How can researchers address the challenge of limited standardized datasets in polymer informatics?

The limited availability of standardized datasets remains a significant challenge in broader adoption of ML in polymer research [1]. To address this, researchers can implement Scientific Data Management Systems (SDMS) that provide centralized, structured access to research data [4]. These systems help maintain traceability, reduce manual overhead, and support scalable, reproducible research. Furthermore, leveraging data from existing polymer databases like PEARL (Polymer Expert Analog Repeat-unit Library) can provide initial datasets for model development [5].

Q4: What specialized software tools are available for AI-driven polymer research?

Several specialized software platforms have emerged to support AI-driven polymer research:

Table: AI-Driven Polymer Research Software Platforms

| Software Platform | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| PolymRize (Matmerize) | Polymer informatics and optimization | AI-driven property prediction, generative AI (POLY), natural language interface (AskPOLY) [2] |

| Polymer Expert | De novo polymer design | Rapid generation of novel candidate polymer repeat units, quantitative structure-property relationships (QSPR) [5] |

| MaterialsZone | Materials informatics platform | AI-driven analytics, domain-specific workflows, experiment optimization [4] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Model Performance in Polymer Property Prediction

Problem: Machine learning models for polymer property prediction demonstrate poor accuracy and generalization.

Solution:

- Advanced Feature Engineering: Implement comprehensive feature engineering from SMILES molecular structures, including topological, electronic, and geometric descriptors [3].

- Ensemble Methods: Combine multiple ML algorithms to improve prediction accuracy and robustness.

- Domain-Specific Validation: Incorporate domain knowledge to validate feature selection and model outputs.

Prevention: Utilize established polymer informatics platforms that incorporate patented fingerprint schemas and multitask deep neural networks designed specifically for polymer property prediction [2].

Issue 2: Data Management and Integration Challenges

Problem: Research data is fragmented across multiple instruments, formats, and systems, hindering effective AI implementation.

Solution:

- Implement SDMS: Deploy a Scientific Data Management System (SDMS) to centralize and structure research data [4].

- Standardize Metadata: Apply consistent metadata tagging to ensure data traceability and searchability.

- Integration Strategy: Select SDMS platforms with API access and integration capabilities for existing lab infrastructure.

Table: Categories of Scientific Data Management Systems

| SDMS Category | Best For | Key Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Standalone SDMS | Labs adding structured data management without replacing existing systems | Dedicated data management, metadata tagging, long-term archiving [4] |

| SDMS Integrated with ELN | Labs focused on experiment reproducibility | Combines data management with experimental documentation, improves traceability [4] |

| AI-Enhanced SDMS | Labs with complex, high-volume data | Automated classification, anomaly detection, intelligent insights [4] |

| Materials Informatics Platforms | Materials science R&D | Domain-specific metadata, AI-driven property prediction, experiment optimization [4] |

Issue 3: Experimental Validation of AI-Generated Polymer Designs

Problem: Difficulty in experimentally validating polymer structures and properties predicted by AI models.

Solution:

- Spectroscopic Validation: Employ computational spectroscopy to validate predicted polymer properties. For example, Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations can generate theoretical spectra for meta-conjugated polymers to guide experimental validation [6].

- Electrochemical Characterization: Use cyclic voltammetry and differential pulse voltammetry to evaluate electrochemical properties of synthesized polymers [6].

- Spectro-electrochemistry: Implement in situ spectro-electrochemical analysis to study the conversion of neutral polymers into charged species [6].

Verification Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational-experimental workflow for validating AI-generated polymer designs:

Issue 4: Implementation of Full-Color Emission Polymer Systems

Problem: Difficulty in achieving predictable full-color emission in polymer systems using traditional approaches.

Solution:

- Machine Learning Guidance: Utilize ML models to explore through-space charge transfer polymers with full-color-tunable emission [7].

- Donor-Acceptor Design: Employ aromatic monomers with varied electron-donating ability polymerized with electron-withdrawing fluorophores as initiators [7].

- Spatial Control: Maintain donor-acceptor spatial proximity within ∼7 Å to influence redshifted charge transfer emission [7].

Experimental Protocol:

- Polymerization Method: Controlled radical polymerization (ATRP) for precise structural control [7].

- Characterization: Combine computational calculations with experimental validation of charge transfer-dependent emission.

- Application Testing: Evaluate performance in practical applications such as photochromic fluorescence and encryption systems [7].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for AI-Driven Polymer Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Meta-Conjugated Linkers (MCLs) | Interrupt charge delocalization to increase band gap | Transparent electrochromic polymers [6] |

| Aromatic Monomers (Carbazole, Biphenyl, Binaphthalene) | Provide electron-donating capability | Full-color emission polymers, electrochromic devices [7] [6] |

| Thiophene-based Comonomers | Serve as aromatic moieties for conjugation tuning | Color-tunable electrochromic polymers [6] |

| Electron-Withdrawing Fluorophores | Act as initiators for charge transfer | Through-space charge transfer polymers [7] |

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Machine Learning-Assisted Exploration of Charge Transfer Polymers

Objective: Develop full-color-tunable emission polymers through ML-guided design [7].

Methodology:

- Data Collection: Compile dataset of polymer structures and corresponding emission properties.

- Model Training: Train ML models to predict emission characteristics based on molecular descriptors.

- Polymer Synthesis: Perform controlled radical polymerization of selected aromatic monomers with electron-withdrawing initiators.

- Characterization: Analyze charge transfer behavior and emission properties.

Key Parameters:

- Donor-acceptor spatial proximity (~7 Å)

- Donor group concentration in polymers

- Electron-donating ability of aromatic monomers

Protocol 2: Development of Transparent Electrochromic Polymers

Objective: Create transparent-to-colored electrochromic polymers with high optical contrast [6].

Methodology:

- Polymer Design: Incorporate meta-conjugated linkers (MCLs) and aromatic moieties along polymer backbones.

- Computational Screening: Perform DFT calculations to predict spectroscopic properties of designed polymers.

- Synthesis: Synthesize selected polymer candidates.

- Electrochemical Testing: Evaluate using cyclic voltammetry and differential pulse voltammetry.

- Performance Validation: Assess optical contrast, switching stability, and color tunability.

Quality Control:

- Target optical contrast exceeding 90%

- Cycling stability over 5000 cycles with minimal contrast decay

- Wide color tunability across visible spectrum

The following diagram illustrates the decision pathway for developing high-performance electrochromic polymers:

The transition from trial-and-error to data-driven paradigms in polymer research represents a fundamental shift in materials development. By leveraging AI and machine learning tools, implementing robust data management systems, and following structured experimental protocols, researchers can significantly accelerate innovation in polymer science. The troubleshooting guides and FAQs provided in this technical support center address common implementation challenges and provide practical methodologies for successful adoption of polymer informatics approaches.

Core AI and Machine Learning Concepts for Polymer Scientists

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses common challenges polymer scientists face when integrating AI and machine learning into their research workflows.

FAQ 1: How can we overcome the scarcity of high-quality, labeled polymer data for training ML models?

- Challenge: High-quality, diverse datasets are often unavailable, and their acquisition is high-cost and low-efficiency [8]. This data scarcity hinders the development of robust ML models.

- Solution:

- Utilize Collaborative Data Platforms: Leverage existing databases like the Cambridge Structural Database (as used in the MIT/Duke ferrocene study) [9], Polydat [10], or PolyInfo [8]. These platforms provide structured data on polymer structures and properties.

- Implement Active Learning Strategies: Use algorithms that can identify the most informative data points to be validated experimentally. This iterative process maximizes model performance while minimizing costly experiments [8].

- Adopt High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE): Shift from traditional sequential research to parallel processing using automated platforms. HTE enables systematic data accumulation and dramatically increases research efficiency [11].

FAQ 2: Our ML model for predicting polymer properties is a "black box." How can we improve its interpretability and build trust in its predictions?

- Challenge: The lack of interpretability of many AI models, especially deep learning, makes it difficult to understand the underlying scientific relationships, leading to skepticism [8] [12].

- Solution:

- Incorporate Explainable AI (XAI) Methodologies: Use techniques like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) or LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) to interpret model predictions and identify which molecular descriptors most influence the output.

- Leverage Domain-Adapted Descriptor Frameworks: Develop and use descriptors that are physically meaningful to polymer scientists, such as the Hildebrand and Hansen solubility parameters for solubility prediction [11]. This aligns the model's reasoning with established scientific principles.

- Perform Feature Impact Analysis: After an optimization process, analyze and interpret the impact of various input features. Eliminating features with minimal impact streamlines the workflow and provides a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms [10].

FAQ 3: What is the most effective way to integrate AI for optimizing polymer synthesis conditions?

- Challenge: Optimizing synthesis parameters like temperature, catalyst concentration, and reaction time is a complex, multi-variable problem.

- Solution:

- Employ Multi-Objective Optimization Algorithms: Use frameworks like Thompson sampling efficient multi-objective optimization (TS-EMO) to find the Pareto front for conflicting objectives (e.g., high yield vs. low dispersity) [10].

- Establish Closed-Loop Automated Workflows: Integrate AI with flow chemistry synthesis and automated chemical analysis (e.g., inline NMR or SEC). The AI model processes the analytical data and automatically suggests the next set of conditions to test, creating a self-optimizing system [10].

Experimental Protocols for Key AI-Driven Polymer Experiments

Protocol 1: ML-Accelerated Discovery of Mechanophores for Tougher Plastics

This protocol is based on the pioneering work by researchers at MIT and Duke University to discover ferrocene-based mechanophores that enhance polymer toughness [9].

1. Objective: To identify and experimentally validate weak crosslinker molecules (mechanophores) that, when incorporated into a polymer network, increase its tear resistance.

2. Methodology:

- Step 1: Data Curation

- Source a large set of candidate molecules from an existing database of synthesized compounds (e.g., the Cambridge Structural Database) to ensure synthesizability [9].

- Step 2: Initial Simulation and Feature Calculation

- Perform quantum mechanical calculations or molecular dynamics simulations on a subset (e.g., 400 compounds) to compute the force required to break critical bonds [9].

- Calculate molecular descriptors for each compound.

- Step 3: Machine Learning Model Training

- Train a neural network model using the simulation data. The input is the molecular structure/descriptors, and the output is the predicted mechanical strength or activation force [9].

- Step 4: High-Throughput Prediction

- Use the trained model to predict the properties of thousands of other compounds in the database [9].

- Step 5: Experimental Validation

- Synthesize the top-ranking AI-predicted mechanophore (e.g., m-TMS-Fc).

- Incorporate it as a crosslinker into a polymer (e.g., polyacrylate).

- Perform mechanical testing (e.g., tear resistance tests) to compare its performance against control materials.

3. Key Data from MIT/Duke Study:

Table 1: Quantitative results from AI-driven discovery of ferrocene mechanophores

| Parameter | Standard Ferrocene Crosslinker | AI-Identified m-TMS-Fc Crosslinker | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Toughness (Tear Resistance) | Baseline | ~4x tougher | 300% increase |

Protocol 2: AI-Guided Inverse Design of Polymers with Targeted Properties

1. Objective: To design a polymer structure that meets a specific set of target properties, such as a defined glass transition temperature (Tg) and biodegradability.

2. Methodology:

- Step 1: Define Target Properties

- Specify the desired properties as continuous values (e.g., Tg = 80°C) or categorical labels (e.g., biodegradable: Yes).

- Step 2: Leverage a Trained ML Model

- Step 3: Generate Candidate Structures

- Inverse Design: Use generative models (e.g., Generative Adversarial Networks or variational autoencoders) to propose novel polymer structures that are predicted to exhibit the target properties [13] [11].

- Virtual Screening: Use the predictive model to screen a virtual library of candidate structures [13].

- Step 4: Synthesis and Validation

- Synthesize the most promising AI-proposed structures.

- Characterize the synthesized polymers to validate if the target properties have been achieved.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential materials and tools for AI-driven polymer research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application in AI Workflow |

|---|---|

| Ferrocene-based Compounds | Act as weak crosslinkers (mechanophores) in polymer networks to enhance toughness and damage resilience [9]. |

| BigSMILES Notation | A standardized language for representing polymer structures, including repeating units and branching, enabling data sharing and ML model training [10]. |

| Polymer Descriptors | Numerical representations of chemical structures (e.g., molecular weight, topological indices, solubility parameters) that serve as input for ML models [8] [10]. |

| Thompson Sampling Efficient Multi-Objective Optimization (TS-EMO) | A Bayesian optimization algorithm used to efficiently navigate complex parameter spaces and balance multiple, conflicting objectives in polymer synthesis [10]. |

| Chromatographic Response Function (CRF) | A scoring function that quantifies the quality of a chromatographic separation, essential for driving ML-based optimization of analytical methods for polymers [10]. |

AI and Machine Learning Workflows in Polymer Science

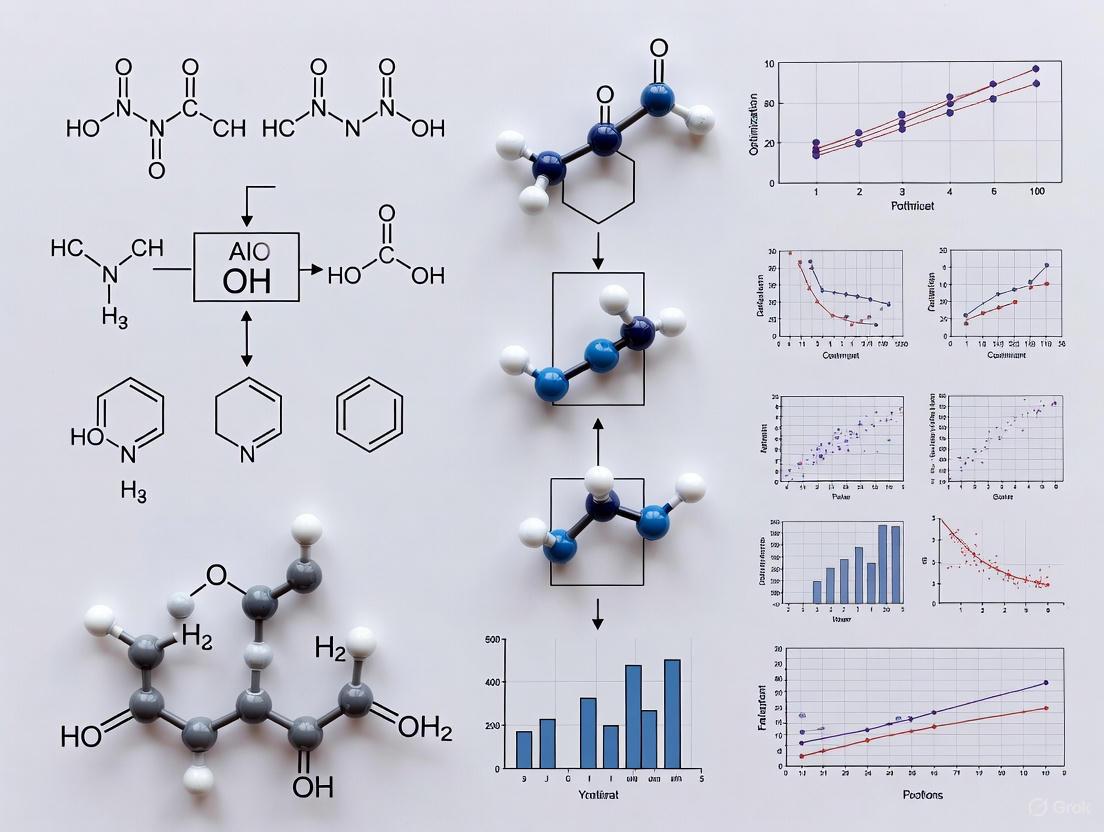

The following diagrams illustrate the logical flow of two primary AI applications in polymer science: the discovery of new materials and the inverse design of polymers.

Diagram 1: AI-driven discovery workflow for new polymer materials. This closed-loop process integrates computational prediction with experimental validation, continuously refining the model with new data [9] [11] [10].

Diagram 2: Inverse design workflow for polymers. This process starts with the desired properties and uses AI to generate molecular structures predicted to achieve them [13] [11].

For researchers and scientists in drug development, understanding key polymer properties is fundamental to designing effective drug delivery systems. The glass transition temperature (Tg), permeability, and degradation profile of a polymer directly influence the stability, drug release kinetics, and overall performance of a pharmaceutical formulation. Within the emerging paradigm of AI-driven polymer optimization, these properties serve as critical targets for predictive modeling and inverse design. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance and foundational knowledge to address common experimental challenges, framing solutions within the context of modern, data-driven research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How does the glass transition temperature (Tg) affect drug release from a polymer matrix?

The Tg is a critical determinant of drug release kinetics. Below its Tg, a polymer is in a rigid, glassy state with minimal molecular mobility, which slows down drug diffusion. When the temperature is at or above the Tg, the polymer transitions to a soft, rubbery state, where increased chain mobility and free volume facilitate faster drug release [14] [15]. This principle is fundamental for controlled-release formulations, such as PLGA-based microspheres, where the Tg can be engineered to control the onset and rate of drug release [14].

2. What experimental factors can influence the measured Tg of a polymer formulation?

Several factors related to your experimental process can impact Tg:

- Residual Solvents and Water: These act as plasticizers, lowering the observed Tg [14] [15].

- Drug-Polymer Interactions: The incorporation of a drug can significantly depress the Tg if it is miscible and acts as a plasticizer. The extent of this effect can be investigated using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) to probe molecular interactions [16].

- Processing and Thermal History: The rate of solvent removal during microparticle formation or film coating is analogous to a cooling rate. Faster solvent removal can result in a glassy polymer with higher excess energy and a different Tg profile. Subsequent physical aging below the Tg can also lead to a gradual reduction in free volume, altering the Tg and the resulting drug release profile over time [14].

3. How can machine learning assist in optimizing polymers for drug delivery?

Machine learning (ML) revolutionizes polymer design by moving beyond traditional trial-and-error approaches.

- Property Prediction: ML models, such as support vector regression (SVR) and graph neural networks (GNNs), can predict key properties like Tg, permeability, and degradation rate from molecular descriptors, significantly accelerating initial screening [17] [8].

- Generative Design: Inverse molecular design algorithms can generate entirely new molecular structures of monomers or polymers optimized for a specific set of target properties (e.g., a specific Tg range and CO2 permeability) [17].

- Release Profile Modeling: Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) and other ML models can analyze complex formulation data to predict drug release profiles from systems like matrix tablets, microspheres, and implants, accounting for the interplay of multiple variables [18].

4. What are the key differences in degradation behavior between a polymeric coating and a bulk polymer?

Polymeric coatings present a unique set of degradation characteristics compared to bulk materials:

- Surface-to-Volume Ratio: Coatings have a very high surface-to-volume ratio, which can lead to faster degradation and drug release kinetics due to enhanced interaction with the aqueous environment [19].

- Interfacial Effects: The adhesion and interaction between the coating and its substrate can influence stress states and water penetration, thereby altering the degradation pathway [19].

- Drug Release Profile: The release of a drug from a biodegradable coating often involves an initial burst release due to drug dissolution or diffusion from the surface, a lag phase, and a final controlled release phase governed by polymer erosion [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Uncontrolled Burst Release from PLGA Microspheres

Problem: An initial burst release is higher than desired, depleting the drug too quickly.

| Possible Cause | Investigation Method | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Low Tg at storage temperature | Perform DSC on the microspheres to determine actual Tg. | Increase the lactide-to-glycolide ratio or molecular weight of the PLGA to raise the intrinsic polymer Tg [14] [15]. |

| Porosity & surface-bound drug | Use SEM to analyze surface morphology. | Optimize the solvent removal rate during manufacturing. Slower hardening can produce a denser matrix [14]. |

| Drug acting as plasticizer | Use DSC and FTIR to analyze drug-polymer miscibility and interactions [16]. | Select a less hydrophilic drug or modify the polymer chemistry to reduce drug-polymer miscibility if plasticization is excessive. |

Issue 2: Inconsistent Drug Release Profiles Between Batches

Problem: Reproducibility is low, with different batches showing variable release kinetics.

| Possible Cause | Investigation Method | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Uncontrolled physical aging | Use DSC to measure enthalpy relaxation in samples with different storage times [14]. | Implement a controlled annealing step post-production to stabilize the polymer matrix and achieve a more consistent energetic state [14]. |

| Variations in residual solvent | Use techniques like Gas Chromatography (GC) to quantify residual solvent. | Standardize and tightly control the drying process (time, temperature, vacuum) across all batches [14]. |

| Inconsistent polymer properties | Thoroughly characterize the intrinsic viscosity and molecular weight of the raw polymer from different lots. | Establish strict quality control (QC) criteria for raw material attributes and leverage ML models to understand how CMA variations affect CQAs [14] [18]. |

Issue 3: Poor Prediction Accuracy of Machine Learning Models for Polymer Properties

Problem: An ML model trained to predict a property like Tg or permeability performs poorly on new data.

| Possible Cause | Investigation Method | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient or low-quality data | Perform statistical analysis of the training dataset for coverage and noise. | Use data augmentation techniques or collaborate to build larger, shared datasets [8]. Apply domain adaptation or active learning strategies to prioritize the most informative experiments [8]. |

| Ineffective molecular descriptors | Analyze feature importance from the ML model. | Move beyond simple descriptors to graph-based representations (e.g., using SMILES strings) that better capture polymer topology [17] [8]. |

| Poor model generalization | Perform k-fold cross-validation and inspect learning curves. | Try ensemble-based models (e.g., Random Forest) which can be robust for complex relationships. For deep learning, ensure the model architecture is suited for the data size and complexity [18] [17]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and their functions in developing and testing polymeric drug delivery systems.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| PLGA (Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)) | A biodegradable polymer used in microspheres, implants, and coatings for controlled release [14] [19]. | The lactide:glycolide ratio and molecular weight are CMAs that directly control Tg, degradation rate, and drug release kinetics [14] [15]. |

| PVP (Polyvinylpyrrolidone) | A common polymer used in film coatings and as a component in solid dispersions to enhance drug solubility [16] [20]. | Its high Tg can stabilize amorphous drugs. Drug-polymer miscibility, assessable via FTIR, is critical to prevent crystallization and control Tg of the blend [16]. |

| DSC (Differential Scanning Calorimetry) | The primary technique for measuring the glass transition temperature (Tg) of polymers and formulations [14] [20]. | For complex pharmaceutical materials, use Modulated DSC to separate the Tg signal from overlapping thermal events like enthalpy relaxation or dehydration [20]. |

| FTIR Spectroscopy | Used to investigate drug-polymer interactions at a molecular level, such as hydrogen bonding [16]. | This helps explain and predict the plasticizing or anti-plasticizing effect of a drug on the polymer's Tg, informing formulation stability [16]. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) via DSC

Principle: DSC measures the heat flow difference between a sample and a reference as a function of temperature. The glass transition appears as a step change in the baseline heat capacity.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Place 3-5 mg of the polymer or formulation in a sealed DSC pan. An empty pan is used as a reference.

- Method Setup: Run a method with the following segments:

- Equilibrate at a starting temperature well below the expected Tg (e.g., 0°C for a Tg of ~50°C).

- Heat the sample and reference at a constant rate (e.g., 10°C/min) to a temperature well above the expected Tg.

- For complex samples, use a modulated DSC method with an underlying heating rate of 2°C/min, a modulation amplitude of ±0.5°C, and a period of 60 seconds to separate reversible transitions (like Tg) from non-reversible events [20].

- Data Analysis: In the resulting thermogram, identify the Tg as a step-like shift in the baseline. The Tg value is typically reported as the midpoint of the transition [20].

Protocol 2: Investigating Drug-Polymer Interactions via FTIR

Principle: FTIR spectroscopy detects changes in vibrational energy levels of chemical bonds. Shifts in absorption bands (e.g., carbonyl stretch) indicate molecular interactions like hydrogen bonding between a drug and polymer.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare thin, homogeneous films of the pure polymer, pure drug, and drug-polymer blends using a solvent casting method [16].

- Data Acquisition: Acquire FTIR spectra for all samples over a defined wavenumber range (e.g., 4000-400 cm⁻¹) using an appropriate spectrometer.

- Analysis: Compare the spectra of the blend with those of the pure components. A shift, broadening, or change in intensity of key functional group bands (e.g., C=O, O-H, N-H) in the blend indicates a molecular-level interaction. The presence of such interactions can help explain observed Tg changes and miscibility [16].

AI-Driven Polymer Optimization Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate how machine learning integrates with experimental research to accelerate polymer design.

AI-Polymer Design Workflow

Experimental Data Feedback Loop

Key Properties of Common Pharmaceutical Polymers

| Polymer | Typical Tg Range (°C) | Degradation Mechanism | Common Drug Delivery Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLGA | 40 - 60 [15] [20] | Hydrolysis of ester bonds [14] [19] | Long-acting injectables, microspheres [14] |

| PLA (Polylactic Acid) | 60 - 65 [20] | Hydrolysis [19] | Biodegradable implants, controlled release [20] |

| PCL (Polycaprolactone) | -60 to -65 [20] | Hydrolytic & enzymatic degradation [19] | Long-term delivery (e.g., caplets, implants) [20] |

| Ethylcellulose | ~130 [20] | Not readily biodegradable; drug release by diffusion [19] | Insulating coating, matrix former for controlled release [20] |

| PVP (K-90) | ~175 [16] | Not readily biodegradable | Film coating, solid dispersions [16] |

Factors Influencing Polymer Tg and Degradation

| Factor | Impact on Tg | Impact on Degradation/Drug Release |

|---|---|---|

| Lactide:Glycolide Ratio | Higher lactide increases Tg [15]. | Higher glycolide content generally increases degradation rate [14]. |

| Molecular Weight | Higher molecular weight increases Tg [14]. | Higher molecular weight typically slows degradation [14]. |

| Presence of Water | Acts as a plasticizer, significantly lowers Tg [14]. | Initiates hydrolytic degradation; increased water uptake accelerates erosion [14] [19]. |

| Drug as Plasticizer | Can depress Tg based on miscibility and interactions [16]. | Altered Tg and matrix mobility can change diffusion and erosion rates. |

The Processing-Structure-Properties-Performance (PSPP) Relationship and AI

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues in AI-Driven Polymer Research

FAQ 1: My AI model for property prediction has high error. What could be wrong?

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Insufficient or Low-Quality Training Data: This is a primary bottleneck in polymer informatics [8] [21]. The available data are often sparse, non-standardized, or lack the specific properties you need.

- Solution: Utilize data augmentation techniques or transfer learning. A model pre-trained on a large, simulated dataset can be fine-tuned with a smaller set of your high-quality experimental data [21]. Explore collaborative data platforms like the Community Resource for Innovation in Polymer Technology (CRIPT) to access broader datasets [21].

Ineffective Polymer Representation (Fingerprinting): Traditional AI models rely on numerical descriptors (fingerprints) of the polymer structure. Standard fingerprints may not capture the complexity and multi-scale nature of polymers [8] [22].

Incorrect Model Choice for the Task: Using a generic model without considering the specific polymer challenge can lead to poor performance.

FAQ 2: How can I accelerate the experimental validation of AI-predicted polymers?

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- The "Synthesis Bottleneck": Manually synthesizing and testing every AI-generated candidate is slow and resource-intensive.

- Solution: Implement a human-in-the-loop or closed-loop workflow [24] [25]. In this approach, the AI suggests experiments, which are then conducted using automated synthesis and characterization platforms (e.g., flow chemistry reactors coupled with inline NMR or SEC). The results are fed back to the AI model to refine its next suggestions, creating an iterative discovery cycle [24] [25] [26].

FAQ 3: My AI model is a "black box." How can I trust its predictions for critical applications like drug delivery?

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Lack of Model Interpretability: Many powerful AI models, particularly deep learning networks, do not inherently provide insights into the reasoning behind their predictions [8].

- Solution: Integrate Explainable AI (XAI) methodologies into your workflow [8]. Techniques like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) or LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) can help identify which structural features or descriptors the model is using to make a prediction, building trust and providing valuable scientific insights [8].

The table below summarizes key AI/ML methods and their applications in modeling the Polymer Processing-Structure-Properties-Performance (PSPP) relationship, helping you select the right tool for your research challenge.

| AI/ML Method | Primary Application in Polymer PSPP | Key Advantages | Reported Performance / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [8] [22] | Property prediction from molecular structure (e.g., Tg, modulus) [8]. | Naturally models molecular structures as graphs, capturing atomic interactions effectively. | polyGNN model offers a strong balance of prediction speed and accuracy [22]. |

| Transformer Models (e.g., polyBERT) [22] | Property prediction from polymer SMILES or BigSMILES strings [22]. | Uses self-attention to weigh important parts of the input string; domain-specific pre-training available. | A traditional benchmark that outperforms general-purpose LLMs in accuracy [22]. |

| Large Language Models (LLMs - Fine-tuned) [27] [22] | Predicting thermal properties (Tg, Tm, Td) directly from text-based SMILES [22]. | Eliminates need for manual fingerprinting; uses transfer learning from vast text corpora. | Fine-tuned LLaMA-3-8B outperformed GPT-3.5 but generally lagged behind traditional fingerprint-based models in accuracy and efficiency [22]. |

| Reinforcement Learning (RL) [8] [24] | Optimization of polymerization process parameters and inverse material design [8] [24]. | Well-suited for sequential decision-making, ideal for navigating complex design spaces. | Successfully used in a "human-in-the-loop" approach to design strong and flexible elastomers [24]. |

| Active Learning / Bayesian Optimization [25] [21] | Guiding high-throughput experiments to efficiently explore formulation and synthesis space. | Reduces the number of experiments needed by focusing on the most informative data points. | Used in closed-loop systems with Thompson sampling for multi-objective optimization (e.g., monomer conversion and dispersity) [25]. |

Experimental Protocol: AI-Guided Discovery of Tough Elastomers

This protocol details a methodology for combining AI with automated experimentation to develop polymers with targeted mechanical properties [24].

1. Problem Definition and Target Property Identification

- Objective: Discover a rubber-like polymer that is both strong and flexible, a traditionally difficult property combination [24].

- Target Properties: Define a quantitative scoring function that represents the desirability of the polymer, combining metrics for both strength (e.g., toughness) and flexibility (e.g., elongation at break) [24] [25].

2. AI Model Setup and Human-in-the-Loop Configuration

- AI Model: Employ a Reinforcement Learning (RL) or Bayesian optimization algorithm [24].

- Input: The model is provided with a defined chemical and parameter space (e.g., available monomers, cross-linkers, reaction conditions) [24].

- Workflow: The AI does not run autonomously. Instead, it operates in an iterative "human-in-the-loop" mode where it suggests an experiment, and researchers provide feedback on the results [24].

3. Iterative Experimentation and Model Refinement

- AI Suggestion: The RL model proposes a specific polymer composition or synthesis condition predicted to improve the target score [24].

- Automated Synthesis & Testing: Chemists conduct the proposed experiment using automated tools (e.g., flow reactors, robotic synthesizers). The resulting material is synthesized, and its properties (e.g., tensile strength) are measured [24].

- Feedback and Model Update: The experimental results (property data) are fed back into the AI model. The model learns from this new data and dynamically adjusts its internal parameters to suggest a better-performing experiment in the next iteration [24].

- Convergence: This loop continues until a material meeting the target criteria is identified or the experimental budget is exhausted.

AI-Human Workflow for Polymer Discovery

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in AI-Driven Polymer Research |

|---|---|

| Mechanophores (e.g., ferrocenes) [9] | Act as force-responsive cross-linkers. When identified by ML and incorporated into polymers, they can create materials that become stronger when stress is applied, increasing tear resistance. |

| BigSMILES Notation [25] [21] | A line notation (extension of SMILES) designed to unambiguously represent polymer structures, including repeating units, branching, and stochasticity. Serves as a standardized input for AI models. |

| polyBERT / Polymer Genome [22] [28] | Pre-trained, domain-specific AI models and fingerprinting tools. They provide a head-start for property prediction tasks, reducing the need for large, in-house datasets and complex feature engineering. |

| Thompson Sampling EMO [25] | A Bayesian optimization algorithm particularly effective for multi-objective optimization (e.g., maximizing yield while minimizing cost) in closed-loop, automated synthesis platforms. |

Experimental Protocol: AI-Augmented Discovery of Tough Plastics

This protocol details a specific approach using ML to identify molecular additives that enhance plastic durability [9].

1. Molecular Database Curation

- Source a database of known, synthesizable molecules to ensure practical relevance. The study used ~5,000 ferrocenes from the Cambridge Structural Database [9].

2. High-Throughput Computational Screening

- Simulation: Use quantum chemical calculations (e.g., Density Functional Theory) to simulate the force required to break a critical bond in each candidate molecule. This calculates the molecule's suitability as a "weak cross-linker" [9].

- Feature Engineering: Extract molecular descriptors and structural features for each compound.

3. Machine Learning Model Training and Prediction

- Training: Train a neural network model on the data from Step 2 (~400 molecules) to learn the relationship between molecular structure and the mechanical activation force [9].

- Prediction: Use the trained model to predict the properties of the remaining thousands of molecules in the database, as well as thousands of similar virtual compounds [9].

4. Synthesis and Validation

- Candidate Selection: Select top-performing candidate molecules identified by the ML model (e.g., m-TMS-Fc) [9].

- Polymerization: Synthesize the polymer (e.g., polyacrylate) incorporating the selected molecule as a cross-linker.

- Mechanical Testing: Experimentally test the tear resistance of the new polymer. The validated polymer showed a fourfold increase in toughness compared to the baseline [9].

AI-Driven Discovery of Tougher Plastics

Overcoming the Combinatorial Complexity of Polymer Discovery with AI

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: How can I start using AI for polymer discovery if I have a small dataset?

Challenge: A common concern is that robust AI models require impractically large amounts of data, which can be a barrier to entry for many research labs.

Solution: Successful AI implementation is possible with smaller, targeted datasets. The key is to use specialized ML strategies designed for data-scarce environments.

- Data Requirements: Machine learning can be successfully applied with data sets containing as few as 50 to several hundred polymers [29]. The choice of algorithm is crucial, as some models perform better with smaller data sets.

- Recommended Strategy: Active Learning. This iterative ML paradigm is particularly effective. Ensemble or statistical ML methods provide uncertainty estimates alongside predictions, helping to identify regions of the feature space with high uncertainty. This guides you to run new, focused experiments that provide the most informative data for the model, dramatically improving efficiency compared to large, random library screens [29].

- Alternative Techniques: Other methods to overcome data scarcity include:

- Transfer Learning: Using a pre-trained model as a starting point for your specific task.

- Bayesian Inference: Incorporating prior knowledge to supplement limited experimental data [29].

FAQ: How do I handle the complexity of polymer properties and processing in AI models?

Challenge: Polymer quality is multi-faceted, encompassing molecular properties (e.g., MWD, CCD) and morphological properties (e.g., PSD), which are difficult to control and predict simultaneously [30].

Solution: Implement a population balance modeling framework combined with real-time optimization.

- Modeling Approach: Use population balance equations (PBE) to create a unified framework that tracks changes in both molecular weight distributions (MWD) and morphological properties like particle size distributions (PSD) [30]. This provides a comprehensive quantitative understanding of how process conditions affect the final product.

- Operational Strategy: For industrial processes, adopt an on-line estimation–optimization approach [30]. This involves:

- State/Parameter Estimation: Using available process measurements to obtain reliable estimates of state variables and time-varying model parameters.

- Dynamic Re-optimization: Periodically re-evaluating time-optimal control policies based on the most recent process information to account for disturbances and uncertainties [30].

FAQ: My AI model suggests a novel polymer. How can I validate its performance in the lab?

Challenge: Transitioning from an AI-predicted polymer structure to a physically realized, tested material requires a structured experimental protocol.

Solution: Follow a closed-loop "Design-Build-Test-Learn" paradigm [29].

Experimental Workflow for AI-Suggested Polymer Validation

Detailed Protocol:

Design & Synthesis:

- Input: The AI model suggests a specific polymer structure, such as a ferrocene-based crosslinker (e.g., m-TMS-Fc) for toughening plastics [9].

- Action: Synthesize the polymer or compound using standard techniques (e.g., free-radical polymerization). For the ferrocene example, it would be incorporated as a crosslinker into a polyacrylate network [9].

Processing:

- Action: Process the synthesized polymer into a form suitable for testing (e.g., a thin film, a molded dog-bone specimen, or a 3D-printed structure) [31]. The processing conditions (temperature, pressure, etc.) should be carefully controlled and documented.

Characterization & Testing:

- Action: Perform relevant tests to measure the properties predicted by the AI.

- Example Tests:

- Mechanical Testing: Perform tear tests or tensile tests. For instance, apply force to the polymer until it tears to measure its toughness and resilience [9].

- Thermal Analysis: Use techniques like Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) and Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) to determine thermal stability [28].

- Structural Characterization: Use Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) for molecular weight, or NMR for chemical structure confirmation.

Data Analysis & Model Feedback:

- Action: Compare the experimental results with the AI's predictions.

- Example Outcome: In the MIT/Duke study, the polymer with the m-TMS-Fc crosslinker was found to be about four times tougher than the control polymer, validating the AI's prediction [9]. This new experimental data is then fed back into the AI model, refining its future predictions and closing the loop [29].

FAQ: How can AI help with industrial-scale polymerization and reduce off-spec product?

Challenge: Industrial polymer plants face issues like process drifts, feedstock variability, and lag times in quality measurement, leading to 5-15% of output being off-specification [32].

Solution: Implement closed-loop AI optimization systems that use reinforcement learning (RL).

- How it Works: RL algorithms are trained on thousands of historical production campaigns. They then analyze live sensor data from the plant and write optimized setpoints back to the distributed control system (DCS) in real-time [32].

- Key Features:

- Real-Time Quality Prediction: Uses inferential quality predictors to estimate critical properties (e.g., melt flow index) in real time, overcoming the hours-long lag of lab samples [32].

- Handling Variability: The model automatically adjusts setpoints to compensate for fluctuations in monomer quality or the use of bio-based/recycled feedstocks [32].

- Catalyst Life Extension: The system can smooth thermal profiles and precisely meter feeds to shield catalysts from deactivation, extending production campaigns and reducing downtime [32].

Key Experimental Data & Protocols

Quantitative Results from AI-Driven Polymer Discovery

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent research, demonstrating the tangible impact of AI in the field.

Table 1: Experimental Outcomes from AI-Driven Polymer Discovery Studies

| AI Application | Polymer System | Key Experimental Results | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identification of novel mechanophores for tougher plastics | Polyacrylate with ferrocene-based crosslinker (m-TMS-Fc) | The resulting polymer was ~4 times tougher than a control polymer using standard ferrocene. | [9] |

| Human-in-the-loop optimization for 3D-printable elastomers | Rubber-like polymers (elastomers) | Successfully created a polymer that is both strong and flexible, overcoming the typical trade-off between these properties. | [31] |

| Closed-loop AI control in an industrial reactor | Not specified (industrial context) | Demonstrated 1-3% increase in throughput and 10-20% reduction in natural gas consumption. | [32] |

| AI-guided discovery of polymers for capacitors | Polymers from polynorbornene and polyimide subclasses | Achieved materials with simultaneously high energy density and high thermal stability for electrostatic energy storage. | [28] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for AI-Guided Polymer Research

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Specific Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Ferrocene-based Mechanophores | Acts as a force-responsive crosslinker. Incorporation into a polymer network can create a "weak link" that increases tear resistance by causing cracks to break more bonds. | m-TMS-Fc, identified from a database of 5,000 ferrocenes, was used to create a tougher polyacrylate plastic [9]. |

| Polynorbornene / Polyimide Monomers | Building blocks for polymers used in advanced applications like electrostatic energy storage (capacitors). | AI identified these polymer subclasses as capable of achieving both high energy density and high thermal stability, a combination difficult to achieve with previous materials [28]. |

| Specialized Catalysts | Initiate and control the polymerization reaction. The choice of catalyst is critical for achieving desired molecular weight and structure. | In industrial settings, AI-driven closed-loop systems can precisely meter catalyst feeds to extend catalyst life and maintain reactor stability [32]. |

| Crosslinking Agents | Molecules that form bridges between polymer chains, determining the network structure and mechanical properties. | AI can identify weak crosslinkers that, counter-intuitively, make the overall material stronger by guiding crack propagation through more, but weaker, bonds [9]. |

Workflow Visualization

The AI-Driven Polymer Discovery Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete iterative cycle, from initial data collection to the final validation of a new polymer, integrating both computational and experimental work.

Active Learning for Data-Efficient Discovery

This diagram details the "Active Learning" loop, a powerful strategy for optimizing experiments when data is limited.

AI Tools in Action: Methodologies and Real-World Applications

Supervised Learning for Predicting Critical Polymer Properties

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental concept behind using supervised learning for polymer property prediction? Supervised learning (SL) trains models on labeled datasets where each input (e.g., a polymer's molecular structure) is associated with a known output (e.g., glass transition temperature). The model learns the underlying relationships between structure and property, enabling it to predict properties for new, unseen polymers. This approach is transformative for polymer informatics, as it can navigate the immense combinatorial complexity of polymer systems far more efficiently than traditional trial-and-error methods [12].

FAQ 2: How are polymer structures converted into a format that machine learning models can understand? Polymers are typically represented using machine-readable formats or numerical descriptors. A common method is using SMILES (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System) strings, which are text-based representations of molecular structures. For LLMs, these strings are used directly as input. Alternatively, in traditional ML, structures are converted into numerical fingerprints or descriptors. These can be hand-crafted features capturing atomic, block, and chain-level information (like Polymer Genome fingerprints), graph-based representations, or descriptors calculated from the structure that encode information like molecular weight, polarity, and topology [22] [33] [12].

FAQ 3: What are the key differences between traditional ML and Large Language Models (LLMs) in this field? Traditional ML methods often require a two-step process: first, creating a handcrafted numerical fingerprint of the polymer, and second, training a model on these fingerprints. In contrast, fine-tuned LLMs can interpret SMILES strings directly, learning both the polymer representation and the structure-property relationship in a single step, which simplifies the workflow [22]. However, LLMs generally require substantial computational resources and can underperform traditional, domain-specific models in terms of predictive accuracy and efficiency for certain tasks [22].

FAQ 4: What is the role of multi-task learning in polymer informatics? Multi-task learning (MTL) is a framework where a single model is trained to predict multiple properties simultaneously (e.g., glass transition, melting, and decomposition temperatures). This allows the model to learn from correlations between different properties, which can improve generalization and predictive performance, especially when the amount of data available for each individual property is limited [22].

FAQ 5: Can AI not only predict but also help design new polymers? Yes, this is a primary goal. Once a reliable supervised learning model is trained, it can be used inversely. Researchers can specify a set of desired properties, and the model can help identify or generate polymer structures that are predicted to meet those criteria. This accelerates the discovery of novel materials for specific applications, such as more durable plastics or polymers for energy storage [9].

Troubleshooting Guide

Issue 1: Poor Model Performance and Low Predictive Accuracy

| Possible Cause | Recommendations & Solutions |

|---|---|

| Insufficient or Low-Quality Data | - Curate larger, high-quality datasets: Ensure your dataset is large enough and contains accurate, experimentally verified property values. For thermal properties, a dataset of over 10,000 data points has been used successfully [22].- Clean and standardize data: Perform canonicalization of SMILES strings to ensure consistent polymer representation [22]. |

| Suboptimal Data Representation | - Explore different fingerprinting methods: If using traditional ML, test different molecular descriptors (e.g., topological, constitutional) or graph-based representations [33] [12].- For LLMs, optimize the input prompt: The structure of the prompt can significantly impact LLM performance. Systematically test different prompt formats [22]. |

| Inappropriate Model Selection | - Benchmark multiple algorithms: Test various models, from simpler ones like Random Forests to more complex Graph Neural Networks or fine-tuned LLMs, to find the best fit for your data [22] [12].- Consider domain-specific models: Models pre-trained or designed specifically for chemical structures (like polyBERT or polyGNN) may outperform general-purpose models [22]. |

Issue 2: Handling Small or Imbalanced Datasets

| Possible Cause | Recommendations & Solutions |

|---|---|

| Limited Data for a Specific Property | - Employ Multi-Task Learning (MTL): Train a single model on multiple related properties to leverage shared information and improve performance on tasks with scarce data [22].- Use Transfer Learning: Start with a model pre-trained on a larger, general chemical dataset and fine-tune it on your specific polymer data [22]. |

| Structural Diversity Not Captured | - Apply data augmentation: For SMILES strings, use different, but equivalent, syntactic variants (after canonicalization) to artificially expand the dataset.- Use simpler models or strong regularization: To prevent overfitting when data is scarce, choose less complex models or apply techniques like L1/L2 regularization [12]. |

Issue 3: Computational Efficiency and Resource Management

| Possible Cause | Recommendations & Solutions |

|---|---|

| Long Training Times for Large Models | - Utilize Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT): For LLMs, use methods like Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) which significantly reduce the number of trainable parameters and memory requirements, speeding up training [22].- Leverage cloud computing or high-performance computing (HPC) clusters: Scale your computational resources to handle demanding model training [22]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Benchmark Dataset for Thermal Properties

The following table summarizes a curated dataset used for benchmarking supervised learning models for predicting key polymer thermal properties [22].

| Property | Value Range (K) | Number of Data Points |

|---|---|---|

| Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) | 80.0 - 873.0 | 5,253 |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 226.0 - 860.0 | 2,171 |

| Thermal Decomposition Temperature (Td) | 291.0 - 1167.0 | 4,316 |

| Total | 11,740 |

Sample Dielectric Constant Prediction Data

The table below shows a subset of experimental and predicted dielectric constant values for various polymers from a QSPR study, demonstrating model performance [33].

| Polymer Name | Experimental Value | Predicted Value | Residual |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(1,4-butadiene) | 2.51 | 2.41 | -0.10 |

| Bisphenol-A Polycarbonate | 2.90 | 2.87 | -0.03 |

| Poly(ether ketone) | 3.20 | 3.08 | -0.12 |

| Polyacrylonitrile | 4.00 | 3.96 | -0.04 |

| Polystyrene | 2.55 | 2.38 | -0.17 |

Workflow Visualization

Supervised Learning Workflow for Polymer Properties

Data Preprocessing and Model Training Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Resource | Function & Application in Polymer Informatics |

|---|---|

| SMILES Strings | A text-based representation of polymer molecular structure that serves as direct input for many models, especially LLMs [22]. |

| Molecular Descriptors/Fingerprints | Numerical representations (e.g., Polymer Genome, topological indices) that encode structural features for traditional machine learning models [22] [33]. |

| polyBERT / polyGNN | Domain-specific models that provide pre-trained, polymer-aware embeddings, often leading to superior performance compared to general-purpose models [22]. |

| Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) | A parameter-efficient fine-tuning method that dramatically reduces computational resources needed to adapt large LLMs to polymer prediction tasks [22]. |

| Ferrocene Database | A library of organometallic compounds (e.g., from the Cambridge Structural Database) used with ML to identify novel mechanophores for designing tougher plastics [9]. |

Leveraging Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for Polymer Structure Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common data-related challenges when applying GNNs to polymers, and how can I overcome them? Polymer informatics faces several data hurdles [34]:

- Challenge: Limited Labeled Data. Experimentally measuring polymer properties is time-consuming and expensive, leading to small datasets that are insufficient for training accurate GNNs [34] [35].

- Solution: Self-Supervised Learning (SSL). You can pre-train a GNN model on a large dataset of polymer structures without needing property labels. The model learns general, meaningful representations of polymer chemistry, which can later be fine-tuned on your small, labeled dataset for a specific task, significantly boosting performance [35].

- Challenge: Data Heterogeneity and Dispersal. Crucial polymer data is often spread across disparate sources, making it difficult to aggregate for effective model training [34].

2. My GNN model for property prediction is not generalizing well to new polymer compositions. What could be wrong? This is often a problem of input representation. Many models only consider the monomer or repeat unit, which fails to capture essential macromolecular characteristics [34].

- Solution: Use a Graph Representation that Includes Macromolecular Features. Ensure your polymer graph encodes more than just the repeat unit. Look for representations that can include features like [35]:

- Stochastic chain architecture

- Monomer stoichiometry in copolymers

- Branching information For example, a model that differentiates between linear and branched polyesters will be more accurate than one that does not [36].

3. How do I represent a complex polymer structure, like a branched copolymer, for a GNN? Traditional simplified representations struggle with this. The solution is to use a graph structure that mirrors the polymer's composition.

- Solution: Represent Monomers as Separate Graphs with a Pooling Mechanism. In this approach, each distinct monomer (e.g., diacids and diols in polyesters) is represented as its own molecular graph. A GNN processes these graphs, and then a pooling mechanism aggregates the information from all monomers into a single, centralized vector that represents the entire polymer. This allows the model to handle a variable number of monomers in a single composition [36].

4. Are there specific GNN architectures that are more effective for polymer property prediction? Yes, research has shown that specific architectures and learning frameworks can enhance performance.

- Solution: Use a Hybrid Architecture. A successful architecture, like PolymerGNN, uses a multi-block design [36]:

- Molecular Embedding Block: Uses a combination of Graph Attention Network (GAT) and GraphSAGE layers to process individual monomer graphs.

- Central Embedding Block: Aggregates information from all monomer units.

- Prediction Network: Outputs the final property estimates. Furthermore, integrating the GNN with a Time Series Transformer has proven effective for predicting complex thermomechanical behaviors by combining structural and temporal data [37].

5. How can I validate that my GNN model is learning chemically relevant patterns and not just memorizing data?

- Solution: Perform Explainability Analysis. Use model explainability techniques to probe which structural features the model identifies as important for a given prediction. Studies have done this to show that GNNs learn chemically intuitive patterns from the data, which builds trust in the model's predictions and can even lead to new scientific insights [36].

Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Approaches

The table below summarizes the quantitative performance of different ML methods for predicting key polymer properties, as reported in the literature. This can help you benchmark your own models.

| Polymer Type | ML Method | Key Architectural Features | Target Property | Performance (Metric) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diverse Polyesters | PolymerGNN (Multitask GNN) | GAT + GraphSAGE layers; separate acid/glycol inputs | Glass Transition (Tg) | R² = 0.8624 [36] | [36] |

| Diverse Polyesters | PolymerGNN (Multitask GNN) | GAT + GraphSAGE layers; separate acid/glycol inputs | Inherent Viscosity (IV) | R² = 0.7067 [36] | [36] |

| General Polymers | Self-Supervised GNN | Ensemble pre-training (node, edge, graph-level) | Electron Affinity | 28.39% RMSE reduction vs. supervised [35] | [35] |

| General Polymers | Self-Supervised GNN | Ensemble pre-training (node, edge, graph-level) | Ionization Potential | 19.09% RMSE reduction vs. supervised [35] | [35] |

| Thermoset SMPs | GNN + Time Series Transformer | Molecular graph embedding fused with temporal data | Recovery Stress | High Pearson Correlation [37] | [37] |

Experimental Protocol: Self-Supervised Pre-training for Low-Data Scenarios

This protocol is designed for situations where labeled property data is scarce but a large corpus of polymer structures (e.g., as SMILES strings) is available [35].

1. Objective: To create a robust GNN model for polymer property prediction when fewer than 250 labeled data points are available.

2. Materials/Software:

- Dataset: A collection of polymer SMILES strings.

- Computing Environment: Python with deep learning libraries (e.g., PyTor, PyTorch Geometric, Deep Graph Library).

- GNN Model: A GNN architecture suitable for your polymer graph representation.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Data Preprocessing and Graph Representation. Convert polymer SMILES strings into graph representations. Each atom becomes a node (with features like atom type), and each bond becomes an edge (with features like bond type). The graph should capture essential polymer features, such as monomer combinations and chain architecture [35] [37].

- Step 2: Self-Supervised Pre-training.

Pre-train the GNN model on the unlabeled polymer graphs using an ensemble of tasks at multiple levels [35]:

- Node-level: Mask some atom features and task the model with predicting them.

- Edge-level: Mask some bond features or existence and task the model with predicting them.

- Graph-level: Use a context prediction task where the model must match a subgraph to its larger context graph. This multi-level pre-training forces the model to learn general, transferable knowledge about polymer chemistry.

- Step 3: Supervised Fine-tuning.

- Take the pre-trained GNN model.

- Replace the pre-training head with a new prediction head suitable for your target property (e.g., a regression layer for glass transition temperature).

- Re-train the entire model on your small, labeled dataset. The model will start from a much more informed state, leading to faster convergence and higher accuracy.

4. Expected Outcome: The self-supervised model is expected to achieve a significantly lower Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) (e.g., reductions of 19-28% as shown in the table above) on the target property prediction task compared to a model trained only with supervised learning on the small dataset [35].

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools for GNN-Based Polymer Analysis

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| PolymerGNN Architecture [36] | Machine Learning Model | A specialized GNN framework for predicting multiple polymer properties from monomer compositions, using a pooling mechanism to handle variable inputs. |

| Graph Attention Network (GAT) [36] | Neural Network Layer | Allows the model to weigh the importance of neighboring nodes differently, capturing nuanced atomic interactions within a monomer. |

| GraphSAGE [36] | Neural Network Layer | Efficiently generates node embeddings by sampling and aggregating features from a node's local neighborhood, suitable for larger molecular graphs. |

| Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) [35] | Machine Learning Paradigm | Reduces the demand for labeled property data by pre-training GNNs on large volumes of unlabeled polymer structure data. |

| SMILES Strings [37] | Data Representation | A text-based method for representing molecular structures, which can be programmatically converted into graph representations for GNN input. |

| Time Series Transformer [37] | Neural Network Model | Captures temporal dependencies in experimental data, which can be integrated with GNNs to predict dynamic properties like recovery stress. |

Workflow Diagram: GNN for Polymer Property Prediction

Generative AI and Deep Learning for Novel Polymer Design

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): Foundations of AI in Polymer Science

Q1: What is the core advantage of using a machine-learning-driven "inverse design" approach over traditional methods for polymer discovery?

Traditional polymer discovery often relies on a "trial-and-error" or "bottom-up" approach, where materials are synthesized and then tested, a process that is time-consuming, resource-intensive, and inefficient for navigating the vast polymer design space [38]. In contrast, the AI-driven inverse design approach flips this paradigm. It starts with the desired properties and uses machine learning (ML) models to rapidly identify candidate polymer structures or optimal fabrication conditions that meet those objectives [38]. This data-driven method can dramatically accelerate the research and development cycle, reducing a process that traditionally takes over a decade to just a few years [8] [39].

Q2: What are the most common types of machine learning models used in polymer property prediction and design?

The application of ML in polymer science utilizes a diverse array of algorithms, each suited for different tasks. The table below summarizes the common models and their typical applications in polymer research.

Table 1: Common Machine Learning Models in Polymer Research

| Class of Algorithm | Specific Models | Common Applications in Polymer Science |

|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning | Random Forest, Support Vector Machines (SVM), Gaussian Process Regression [39] | Predicting properties like glass transition temperature, Young's modulus, and gas permeability from molecular descriptors [8]. |

| Deep Learning | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [8] | Mapping complex molecular structures to properties; analyzing spectral or image data from characterization [8]. |

| Generative Models | Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) [39] | Designing novel polymer molecules with targeted properties [40]. |

Q3: Our research lab faces a challenge with limited high-quality experimental data. How can we still leverage AI?

Data scarcity is a recognized challenge in the field [8]. Several strategies can help mitigate this:

- Leverage Public Databases: Utilize existing databases such as PolyInfo, the Materials Project, and AFLOW which contain extensive material data from experiments and simulations [8] [39].

- Implement Active Learning: This strategy involves an iterative process where the ML model identifies which data points would be most valuable to acquire next, guiding a focused and efficient experimental campaign to maximize the value of each synthesis [8] [39].

- Use Explainable AI (XAI) Tools: When data is limited, understanding the model's predictions is critical. XAI tools help interpret the model's reasoning and identify the key features influencing its output, adding a layer of validation and trust [38].

Q4: What are "Self-Driving Laboratories (SDLs)" and how do they integrate with AI for polymer research?

Self-Driving Laboratories (SDLs) represent the physical embodiment of AI-driven research. An SDL is an automated laboratory that combines robotics, AI, and real-time data analysis to autonomously conduct experiments [26]. In polymer science, an SDL can set reaction parameters, execute synthesis, analyze results, and then use an ML model to decide the next optimal experiment to run, creating a closed-loop system that operates 24/7. This "intelligent operating system" significantly accelerates the discovery and optimization of new polymers [26].

Technical Troubleshooting Guides

Data-Related Issues

Problem: Poor Model Performance and Generalization Due to Data Quality

- Symptom: Your trained model performs well on its training data but fails to make accurate predictions on new, unseen polymer candidates.

- Solution Checklist:

- Audit Your Data Sources: Ensure data is sourced from consistent experimental protocols. Prefer curated databases like PolyInfo where possible [8].

- Feature Engineering Review: Polymer structures are complex. Confirm that your molecular descriptors (e.g., molecular fingerprints, topological indices) effectively capture the multi-scale features relevant to your target property. Inadequate descriptors are a major cause of poor performance [8] [39].

- Check for Data Leakage: Ensure that no information from your test set (e.g., highly similar polymers) has inadvertently been included in the training process.

Model Implementation & Validation Issues

Problem: The "Black Box" Problem and Lack of Trust in Model Predictions

- Symptom: The AI model suggests a novel polymer design, but the reasoning is opaque, making researchers hesitant to commit resources to synthesis.

- Solution Protocol:

- Implement Explainable AI (XAI): Use techniques like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) or model-specific feature importance analyzers to interpret the prediction [38]. This identifies which structural features or processing parameters the model deems most critical.

- Computational Validation: Before proceeding to lab synthesis, validate the AI-proposed candidate using computational simulation tools like Molecular Dynamics (MD) or Density Functional Theory (DFT) to check for consistency with known physical principles [38].

- Human-in-the-Loop Review: A domain expert should review the XAI insights and computational validation results to provide final approval, ensuring the suggestion is scientifically plausible [26].

Experimental Validation Issues

Problem: AI-Proposed Polymer Cannot Be Synthesized or Does Not Exhibit Predicted Properties

- Symptom: A candidate polymer identified through ML optimization fails during lab-scale synthesis or its measured properties deviate significantly from model predictions.

- Solution Protocol:

- Verify Synthesis Constraints: Re-examine the model's training data and constraints. Was synthesizability a defined criterion? Ensure the model was trained on synthetically feasible molecules, for instance, by using databases of previously synthesized compounds as a starting point [9].

- Refine with High-Throughput Experiments: If resources allow, use high-throughput virtual screening (HTVS) or automated synthesis robots to test a small family of similar structures suggested by the model. This data can be fed back to retrain and improve the model [38].

- Revisit the Hypothesis: The failure may reveal an incomplete structure-property relationship. Use the experimental results to refine the model's features and hypotheses for the next design cycle [8].

Key Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Case Study: ML-Aided Discovery of Tougher Plastics with Ferrocene Mechanophores

This protocol is based on a published study from MIT and Duke University, which used ML to identify ferrocene-based molecules that make plastics more tear-resistant [9].

1. Objective: Discover and validate novel ferrocene-based mechanophores that act as weak crosslinkers in polyacrylate, increasing its tear resistance.

2. Methodology:

- Data Curation: Begin with a known, synthesizable chemical space. The researchers used the Cambridge Structural Database, which contains 5,000 ferrocene structures [9].

- Feature Generation and Initial Training: For a subset of ~400 compounds, perform computational simulations (e.g., molecular mechanics) to calculate the force required to break bonds within the molecule. This data, paired with structural descriptors, is used to train an initial ML model [9].

- High-Throughput Virtual Screening: The trained model predicts the force-response for the remaining thousands of compounds in the database, identifying candidates most likely to function as weak, force-responsive links [9].

- Experimental Validation:

- Synthesis: Select top candidates (e.g., m-TMS-Fc) and synthesize them.

- Polymerization & Fabrication: Incorporate the selected ferrocene crosslinker into a polyacrylate network via standard polymerization techniques.

- Mechanical Testing: Subject the synthesized polymer to tensile or tear tests. The study found the ML-identified polymer to be four times tougher than a control polymer with a standard ferrocene crosslinker [9].

The workflow for this inverse design process is as follows:

Table 2: Key Resources for AI-Driven Polymer Research

| Category | Item / Resource | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Databases | PolyInfo, Materials Project, Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) [9] [8] | Provide foundational data on polymer structures and properties for training and validating machine learning models. |

| Molecular Descriptors | Molecular Fingerprints, Topological Descriptors, SMILES Strings [8] [39] | Translate complex chemical structures into numerical or textual data that machine learning algorithms can process. |

| Simulation & Validation Software | Molecular Dynamics (MD), Density Functional Theory (DFT) [38] | Used for generating initial training data and for computationally validating AI-proposed polymer candidates before synthesis. |

| AI/ML Algorithms & Frameworks | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), Random Forest, Bayesian Optimization (BO) [9] [38] [8] | The core engines for building predictive models, optimizing formulations, and generating novel polymer designs. |

| Explainable AI (XAI) Tools | SHAP, LIME [38] | Provide post-hoc interpretations of ML model predictions, helping researchers understand the "why" behind a proposed design. |

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) is driving a fundamental paradigm shift in polymer science, moving from traditional trial-and-error methods to data-driven discovery [12] [8]. This case study examines the application of this new paradigm to accelerate the discovery and development of bio-based alternatives to polyethylene terephthalate (PET), a petroleum-based plastic widely used in packaging and textiles. The traditional development workflow for new polymer materials is complex and time-consuming, often spanning more than a decade from concept to commercialization [8]. AI technologies are now being deployed to significantly compress this timeline by efficiently navigating the high-dimensional chemical space of sustainable polymers, predicting their properties, and optimizing synthesis pathways [12] [41].