Advanced RAFT Polymerization Optimization: Techniques for Controlled Synthesis and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide to optimizing Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain Transfer (RAFT) polymerization for researchers and drug development professionals.

Advanced RAFT Polymerization Optimization: Techniques for Controlled Synthesis and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to optimizing Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain Transfer (RAFT) polymerization for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers fundamental mechanisms and RAFT agent selection, explores advanced methodological approaches including automated and photo-mediated techniques, and addresses common troubleshooting scenarios. The content includes comparative analysis with other controlled polymerization methods and validates optimization success through practical case studies in biomedicine, offering a strategic framework for achieving precise polymer architectures with tailored properties for advanced applications.

Mastering RAFT Fundamentals: Mechanism, Agent Selection, and Kinetic Principles

Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain Transfer (RAFT) polymerization is a versatile form of reversible-deactivation radical polymerization (RDRP) that provides exceptional control over molecular weight, dispersity, and polymer architecture [1]. Discovered at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) of Australia in 1998, the process is mediated by thiocarbonylthio compounds (RAFT agents) which enable a degenerative chain-transfer mechanism [1]. The core of the RAFT process revolves around two key equilibrium stages – the pre-equilibrium and the main equilibrium – that control the growth of polymer chains and are fundamental to its effectiveness. This mechanism allows for the production of polymers with complex architectures, including linear block copolymers, star, brush, and comb polymers, which are valuable in applications ranging from drug delivery to material science [1] [2]. Understanding the intricacies of these equilibria and their intermediates is crucial for optimizing RAFT polymerization for advanced research and industrial applications.

The RAFT Mechanism: A Step-by-Step Analysis

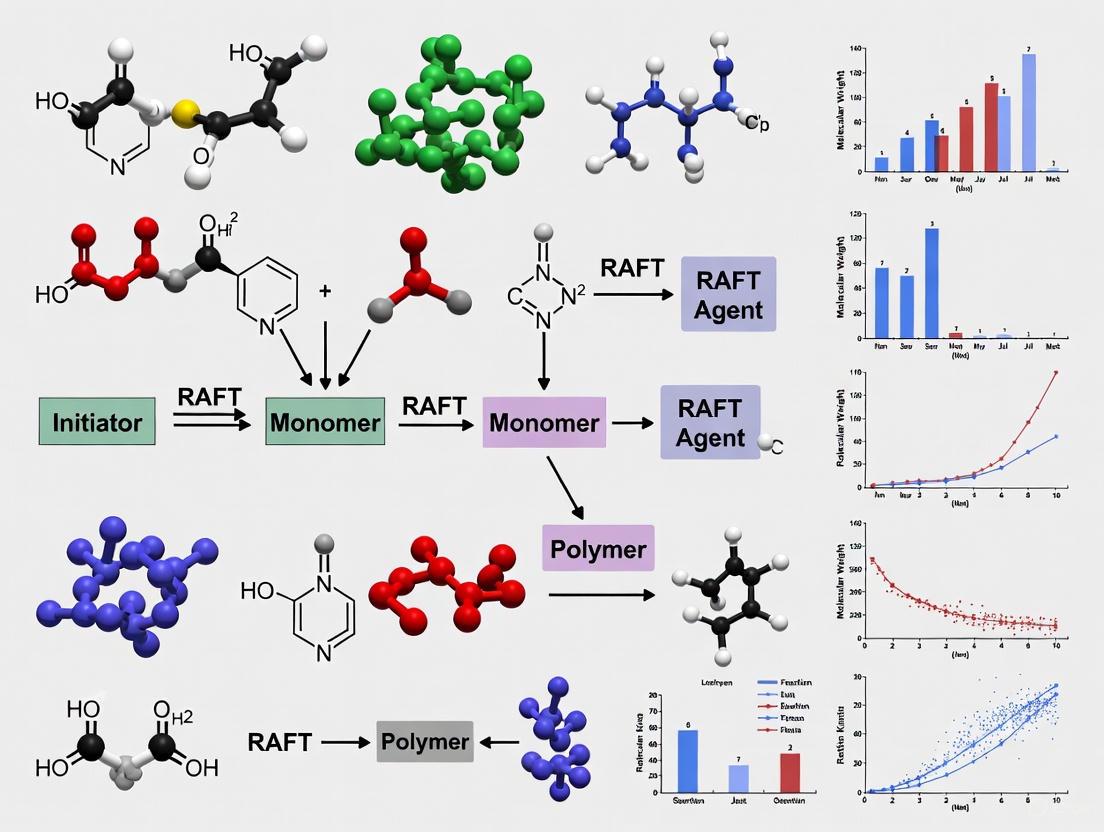

The RAFT mechanism integrates seamlessly with a conventional free radical polymerization process but introduces critical control steps through the RAFT agent [1] [2]. The following diagram illustrates the complete mechanism and the relationships between its key stages.

Initiation and Propagation

The RAFT process begins with the generation of free radicals from an external initiator source, such as azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) or 4,4'-azobis(4-cyanovaleric acid) (ACVA) [1] [2]. These radical initiators decompose thermally to produce radical fragments (I•), which then react with monomer molecules to form the initial propagating polymeric radicals (Pn•). This initiation step is followed by propagation, where these active radical centers sequentially add to monomer units, growing the polymer chain [1]. The concentration of initiator should be carefully controlled, as it influences the number of radical chains and the rate of polymerization [2].

The Pre-Equilibrium Stage

The pre-equilibrium is the first critical control step mediated by the RAFT agent. In this stage, a propagating radical (Pn•) reacts with the thiocarbonylthio group of the RAFT agent (S=C(Z)S-R). This reaction forms a key intermediate adduct radical (Pn-S-C•(Z)-S-R), which is stabilized by the Z-group [1]. This intermediate can then undergo fragmentation in two possible directions [1] [2]:

- It can revert to the original propagating radical (Pn•) and the RAFT agent.

- It can fragment to release the R-group as a new radical (R•), while the polymer chain becomes a macro-RAFT agent (Pn-S-C(Z)=S).

The structure of the RAFT agent is paramount here. The Z-group (e.g., phenyl, alkyl, OR) primarily affects the stability of the C=S bond and the adduct radical, influencing the activity of the RAFT agent and its ability to control the polymerization [1]. The R-group must be a good leaving group, able to stabilize a radical sufficiently to facilitate fragmentation, but also reactive enough to efficiently re-initiate polymerization [1].

Re-initiation

The R• radical generated from the fragmentation of the adduct radical is now available to react with monomer, forming a new propagating radical (Pm•) [1]. This re-initiation step is crucial for ensuring that all polymer chains begin growth at approximately the same time, which is a prerequisite for achieving a narrow molecular weight distribution. The R-group must be chosen so that R• is a efficient re-initiating radical for the specific monomer being polymerized [1].

The Main Equilibrium

The main equilibrium is the central, repetitive cycle that confers living characteristics to the RAFT process. In this stage, a new propagating radical (Pm•) reacts with the macro-RAFT agent (Pn-S-C(Z)=S) to form the same type of intermediate adduct radical (Pn-S-C•(Z)-S-Pm) [1]. This intermediate rapidly fragments to regenerate an equivalent radical (Pn• or Pm•) and a macro-RAFT agent. This reversible activation-deactivation process is extremely fast, allowing all polymer chains to spend an equal amount of time in the active state. This "equal opportunity" growth is the key to producing polymers with low dispersity (Ð) [1]. The position of this equilibrium can be influenced by temperature and the chemical structures of the Z-group and the propagating radical, potentially leading to rate retardation if the adduct radical is too stable [1].

Termination

As in any free-radical polymerization, termination occurs when two propagating radicals (Pn• and Pm•) react with each other via combination or disproportionation, forming "dead" polymer chains that can no longer grow [1] [2]. A significant advantage of the RAFT mechanism is that the intermediate adduct radical is typically hindered and less likely to undergo termination reactions, which helps maximize the number of living chains [2]. The fraction of chains that terminate is minimized by using a high concentration of RAFT agent relative to the initiator [1].

Quantitative Analysis of RAFT Kinetics

Key Kinetic Parameters and Relationships

The rate of polymerization (Rp) in RAFT is primarily governed by the concentration of active propagating radicals [P•] and the propagation rate constant (kpp = kp[P•][M] [1]. The main equilibrium controls [P•]. If the intermediate adduct radical is highly stable, it can lower [P•] and cause rate retardation compared to a conventional radical polymerization. The rate of termination, being second order ([P•]2), is suppressed even more effectively in such retarded systems [1].

Table 1: Apparent Depolymerization Rate Constants for Polymethacrylates with Different Side Chains [3]

| Polymer | Side Chain Structure | Apparent Depolymerization Rate Constant (h⁻¹) | Normalized Rate (Relative to PMMA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PMMA | Methyl | 0.41 | 1.0 |

| PEtMA | Ethyl | ~0.49* | ~1.2 |

| PBuMA | Butyl | ~0.55* | ~1.34 |

| PHexMA | Hexyl | ~0.61* | ~1.49 |

| PLauMA | Lauryl | ~0.70 | ~1.7 |

Note: Values for PEtMA, PBuMA, and PHexMA are estimated from the kinetic profile in [3].

Recent research on RAFT depolymerization has provided profound insights into the kinetics of the reverse process. A 2025 study by Felician et al. systematically investigated the effect of the polymer side chain on depolymerization kinetics [3]. As shown in Table 1, a clear trend of increasing depolymerization rate with increasing alkyl side chain length was observed for polymethacrylates. This acceleration is attributed to a lower energy barrier for the key fragmentation step in the main equilibrium during depropagation. Crucially, the addition of a radical initiator during depolymerization equilibrated the rates for different side chains, identifying chain activation as the rate-determining step in RAFT depolymerization [3]. This finding underscores the critical role of the main equilibrium's kinetics in both polymerization and depolymerization.

Kinetic Modeling of Photo-Mediated RAFT Step-Growth

Advanced kinetic models have been developed for specific RAFT systems. For photo-mediated RAFT step-growth polymerization, the rate of polymerization (Rp) has been derived based on a mechanism where initiation occurs via photolysis of the end-group RAFT agent (Activation Pathway I) [4]. Assuming monomer addition is the rate-limiting step (kadd, kfrag >> ki), the model simplifies to a three-halves order dependence [4]:

Rp = kp (kPI/kt)1/2 [M] [CTA]1/2

Where:

- kp is the propagation rate constant

- kPI is the photoactivation rate constant of the RAFT agent

- kt is the general termination rate constant

- [M] is the monomer concentration

- [CTA] is the RAFT agent concentration

This model highlights the distinct kinetic behavior of photo-RAFT systems compared to thermally initiated ones and provides a quantitative framework for optimizing reaction conditions.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Investigating the Main Equilibrium via Depolymerization Kinetics

This protocol is adapted from recent research that used depolymerization to elucidate the rate-determining step in the RAFT main equilibrium [3].

Objective: To determine the effect of side-chain length on the depolymerization rate and identify the rate-determining step.

Materials:

- Polymers: Well-defined poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), poly(ethyl methacrylate) (PEtMA), poly(butyl methacrylate) (PBuMA), poly(hexyl methacrylate) (PHexMA), and poly(lauryl methacrylate) (PLauMA) synthesized via RAFT polymerization (Target DP = 30, Đ ≈ 1.1).

- Solvent: Anhydrous 1,4-dioxane.

- Radical Initiator: AIBN or similar thermal initiator.

Equipment:

- Schlenk line or glove box for inert atmosphere operation.

- Heated reaction vessel with magnetic stirrer.

- NMR spectrometer for time-resolved conversion analysis.

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare separate solutions of each polymer in 1,4-dioxane with a repeat unit concentration (RUC) of 20 mM.

- Depolymerization Initiation: Transfer 5-10 mL of each polymer solution into separate reaction vessels. Seal the vessels and purge with inert gas (N2 or Ar) to remove oxygen. Heat the solutions to 120 °C with constant stirring to initiate depolymerization.

- Kinetic Sampling: At regular intervals (e.g., 0, 10, 20, 40, 60, 90, 120 min), withdraw 100-200 µL aliquots from the reaction mixture.

- Analysis: Analyze each aliquot by 1H NMR spectroscopy to determine the concentration of regenerated monomer. Plot monomer conversion versus time.

- Data Processing: For the initial hour of the reaction, plot the logarithm of depolymerization conversion versus time to obtain a pseudo-first-order kinetic plot. The slope of the linear fit gives the apparent depolymerization rate constant (kapp).

- Initiator Addition Experiment: Repeat the depolymerization of PMMA and PHexMA with the addition of a small, controlled amount of radical initiator (e.g., AIBN). Compare the new apparent rate constants.

Expected Outcomes: A significant acceleration of depolymerization rate with increasing side-chain length will be observed. The addition of a radical initiator should equilibrate the rates of PMMA and PHexMA, providing direct experimental evidence that chain activation is the rate-determining step in the main equilibrium during depolymerization [3].

Protocol 2: Electron Spin Resonance (ESR) Spectroscopy for Radical Intermediates

This protocol is based on a 2025 study using ESR to confirm the dominant initiation pathway in photo-RAFT step-growth polymerization [4].

Objective: To use spin trapping to detect and identify the radical intermediates generated during the photolysis of RAFT agents, specifically to confirm the dominance of Activation Pathway I (end-group cleavage).

Materials:

- RAFT Agents: 2-(Butylthiocarbonothioylthio)-2-methylpropanoic acid (BDMAT), maleimide SUMI adduct, (propanoic acid)yl butyl trithiocarbonate (PABTC).

- Spin Trap: 5,5-Dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO).

- Solvents: Anhydrous 1,4-dioxane and toluene.

Equipment:

- X-band ESR spectrometer.

- Photoreactor equipped with LEDs (λmax = 405 nm).

- Quartz ESR flat cells suitable for in-situ irradiation.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare solutions in an inert atmosphere glove box. For each RAFT agent (BDMAT, maleimide SUMI adduct, PABTC), create a mixture with a 1:3 molar ratio of RAFT agent to DMPO spin trap in 1,4-dioxane and toluene (e.g., 1 mM RAFT agent, 3 mM DMPO).

- Irradiation and Measurement: Transfer the solution to a quartz ESR cell. Irradiate the sample directly within the ESR cavity using 405 nm light for 15 minutes.

- Spectra Acquisition: Immediately record the X-band ESR spectrum after the irradiation period.

- Control Experiments: Repeat the procedure by separately irradiating solutions containing only DMPO and only each RAFT agent.

Expected Outcomes: For the RAFT agent BDMAT with a tertiary carboxyalkyl R-group, a characteristic ESR signal (e.g., two series of six hyperfine lines) will be observed, confirming the generation of the R• radical via Activation Pathway I. In contrast, for the backbone RAFT agents (maleimide SUMI adduct and PABTC), no discernible signals are expected, indicating that Activation Pathway II (backbone cleavage) does not occur under these conditions [4]. This provides direct experimental verification of the preferred fragmentation pathway.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RAFT Mechanistic Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Mechanism | Example & Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| RAFT Agent | Mediates pre- and main equilibria. The core control agent. | BDMAT: Common for methacrylates. Z-group (e.g., Ph) stabilizes adduct radical. R-group (e.g., -C(CH3)2CN) must be a good leaving/re-initiating group [1]. |

| Thermal Initiator | Source of primary radicals to initiate chains. | AIBN, ACVA. Use at low concentration relative to RAFT agent to minimize chains born from initiator and thus termination [1] [2]. |

| Solvent | Reaction medium. | 1,4-Dioxane, Toluene, DMF. Must dissolve all components (monomer, polymer, RAFT agent). Inert to radicals. Concentration affects rate and equilibrium [3] [5]. |

| Monomer | Building block of the polymer chain. | Methyl Methacrylate, n-Alkyl Methacrylates. Structure affects propagation rate (kp) and fragmentation efficiency in the main equilibrium [3]. |

| Spin Trap | Traps transient radicals for ESR detection. | DMPO (5,5-Dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide). Forms stable adducts with radical intermediates (R•, Pn•) for mechanistic verification [4]. |

| Radical Scavenger | Quenches polymerization for analysis. | Hydroquinone, BHT. Used to stop reactions at specific time points for kinetic studies. |

A deep mechanistic understanding of the RAFT pre-equilibrium and main equilibrium is fundamental to harnessing the full potential of this powerful polymerization technique. The key intermediate adduct radical sits at the heart of the control mechanism, and its formation and fragmentation kinetics dictate the success of the polymerization. Quantitative kinetic studies, such as recent depolymerization experiments, have directly identified chain activation as a critical rate-determining step, influenced by factors like the polymer side chain [3]. Furthermore, advanced spectroscopic techniques like ESR spectroscopy provide direct experimental evidence for the radical intermediates involved [4]. The integration of kinetic modeling, mechanistic probes, and carefully designed experimental protocols, as outlined in this application note, provides researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for optimizing RAFT polymerization and depolymerization processes, ultimately enabling the precise synthesis of next-generation polymeric materials.

Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain Transfer (RAFT) polymerization is a versatile controlled radical polymerization technique that enables precise synthesis of macromolecules with complex architectures, including block, graft, star, and comb structures [6] [2]. Discovered in 1998, RAFT polymerization has become a fundamental tool in polymer science due to its compatibility with a wide range of vinyl monomers and reaction conditions [7] [6]. The core mechanism of RAFT polymerization relies on chain transfer agents (CTAs) containing thiocarbonylthio groups (Z-C(=S)S-R), which mediate polymerization through a reversible chain-transfer process, effectively reducing the concentration of free radicals and enabling controlled chain growth [7] [2].

The molecular structure of RAFT agents plays a critical role in determining polymerization kinetics and the degree of structural control achieved. Each RAFT agent features two key substituents: the Z-group (or activating group) and the R-group (or leaving group) [6]. The Z-group, attached directly to the thiocarbonyl group, influences the reactivity of the C=S bond toward radical addition and the stability of the intermediate radical. The R-group must be a good leaving group capable of re-initiating polymerization and is typically a free radical stabilized by neighboring substituents [6]. Proper selection of these groups is essential for achieving controlled polymerization with narrow molecular weight distributions and high end-group fidelity [6].

RAFT Agent Classes and Their Properties

RAFT agents are primarily categorized based on the nature of their Z-group, which significantly impacts their transfer constants, stability, and monomer compatibility [6]. The four main classes of RAFT agents include:

- Dithiobenzoates: Characterized by an aromatic Z-group, these agents exhibit very high transfer constants but are prone to hydrolysis and may cause polymerization retardation at high concentrations [6].

- Trithiocarbonates: Featuring a sulfur-based Z-group, these compounds offer high transfer constants with greater hydrolytic stability than dithiobenzoates and cause less retardation [6].

- Dithiocarbamates: Their activity is determined by substituents on the nitrogen atom, making them particularly effective with electron-rich monomers [6].

- Xanthates: With an oxygen-based Z-group, these agents have lower transfer constants and are more effective with less activated monomers, with activity enhanced by electron-withdrawing substituents [6].

The selection of appropriate RAFT agents depends heavily on the monomer type being polymerized, as the reactivity of both Z and R groups must be matched to the monomer's radical stability and electronic characteristics [6].

RAFT Agent to Monomer Compatibility Guidelines

The table below summarizes compatibility between major RAFT agent classes and common monomer types, using a rating system where "++" indicates excellent compatibility, "+" indicates good compatibility, "+-" indicates moderate compatibility, and "-" indicates poor compatibility [6]:

Table 1: RAFT Agent to Monomer Compatibility Guide

| RAFT Agent (Example Product Number) | Styrenes | Methacrylates | Methacrylamides | Acrylates | Acrylamides | Vinyl Esters | Vinyl Amides |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dithiobenzoates | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | - | - |

| Trithiocarbonates (723037) | ++ | ++ | ++ | +- | +- | - | - |

| Dithiocarbamates | + | +- | +- | ++ | ++ | +- | +- |

| Xanthates | - | - | - | +- | +- | ++ | ++ |

This compatibility framework stems from the need to match RAFT agent reactivity with monomer properties. More activated monomers (MAMs) such as styrenes, methacrylates, and methacrylamides require RAFT agents with higher chain transfer constants, typically provided by dithiobenzoates and trithiocarbonates [6]. Less activated monomers (LAMs) including vinyl esters and vinyl amides pair effectively with less active RAFT agents such as xanthates [6]. Acrylates and acrylamides, which fall between these categories, demonstrate moderate compatibility with multiple RAFT agent classes [6].

Mechanistic Basis for RAFT Agent Selection

The RAFT Polymerization Equilibrium

The RAFT polymerization mechanism operates through a series of reversible addition-fragmentation steps that establish dynamic equilibrium between active and dormant chain species [7]. The process begins when conventional initiation (thermal, photochemical, or redox) generates primary radicals that react with monomers to form propagating chains [2]. These active chains (Pn•) then react with the RAFT agent's thiocarbonylthio group, forming an intermediate radical that fragments to yield a new radical (R•) and a dormant thiocarbonylthio-terminated chain [7] [2].

The R-group must be a good leaving group capable of efficiently re-initiating polymerization. A well-designed R-group forms a radical that readily reacts with monomers but does not undergo undesirable side reactions [6]. The Z-group controls the reactivity of the C=S bond by modifying its electrophilicity and stabilizing the intermediate radical adduct [6]. Electron-withdrawing Z-groups enhance the reactivity of the C=S bond toward radical addition, while electron-donating Z-groups decrease it [8].

Diagram: RAFT Polymerization Mechanism

Structure-Reactivity Relationships

The Z-group's electronic properties directly impact the stability of the intermediate radical formed during the RAFT equilibrium. Electron-withdrawing Z-groups stabilize the intermediate radical through resonance delocalization, enhancing the fragmentation rate of the leaving R-group [8]. This principle was demonstrated in depolymerization studies where dithiobenzoates with electron-donating Z-groups (e.g., methoxy, tertiary butoxy) exhibited accelerated bond fragmentation compared to those with electron-withdrawing groups (e.g., trifluoromethyl, trifluoromethoxy) [8].

The R-group must be a good leaving group relative to the propagating radical and an efficient re-initiating species. As a general guideline, the R-group should be similar to or better than the propagating chain end at adding to monomers [6]. For instance, cyanoisopropyl and cyanopentanoic acid-derived R-groups work effectively with methacrylates and styrenes, while less stabilized R-groups (e.g., phenyl) are more suitable for less activated monomers like vinyl acetate [6].

Experimental Protocols for RAFT Agent Evaluation

Thermal RAFT Polymerization Protocol

Materials:

- Monomer (e.g., methyl acrylate, styrene, or methyl methacrylate)

- Selected RAFT agent (see Table 1 for compatibility guidance)

- Thermal initiator (e.g., AIBN or ACVA)

- Solvent (if required, depending on monomer solubility)

- Schlenk flask or reaction vessel with septum

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: In a suitable container, prepare a reaction mixture containing monomer (typically 2-4 M in solvent), RAFT agent (concentration determined by target molecular weight: DP = [Monomer]/[CTA]), and thermal initiator (typically 0.1-0.2 × [CTA]) [6] [2].

- Deoxygenation: Transfer the solution to a Schlenk flask and degas using three freeze-pump-thaw cycles or by sparging with inert gas (N₂ or Ar) for 20-30 minutes [2].

- Polymerization: Place the reaction vessel in a preheated oil bath at the appropriate temperature (typically 60-70°C for AIBN initiation). Monitor reaction progress over time [2].

- Sampling and Analysis: At predetermined intervals, withdraw small aliquots for conversion analysis (e.g., by ¹H NMR spectroscopy) and molecular weight characterization (by size exclusion chromatography) [4].

- Termination and Purification: After reaching desired conversion, cool the reaction mixture to room temperature, expose to air to terminate polymerization, and recover polymer by precipitation into a non-solvent [2].

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Broad molecular weight distribution may indicate improper RAFT agent selection or insufficient deoxygenation [6].

- Low conversion may suggest initiator decomposition issues or inappropriate R-group selection [6].

- Retardation effects are common with certain dithiobenzoate RAFT agents at high concentrations [6].

Photo-Mediated RAFT Polymerization Protocol

Materials:

- Monomer

- RAFT agent

- Photocatalyst (for PET-RAFT, e.g., erythrosin B, conjugated cross-linked phosphine) or none (for photo-iniferter)

- Light source (wavelength appropriate for RAFT agent or photocatalyst)

- Reaction vessel with transparent window for illumination

Procedure:

- Reaction Mixture: In a vial, combine monomer, RAFT agent, and photocatalyst (if using PET-RAFT) at appropriate concentrations [4] [9].

- Deoxygenation: Sparge the mixture with inert gas for 15-20 minutes to remove oxygen, which inhibits radical polymerization [10].

- Irradiation: Place the reaction vessel at a fixed distance from the light source (e.g., blue LEDs at 405-470 nm for many PET-RAFT systems) and initiate polymerization [4] [9].

- Kinetic Monitoring: Withdraw aliquots at timed intervals for conversion and molecular weight analysis to establish polymerization kinetics [4].

- Polymer Recovery: After desired conversion, turn off light source and recover polymer by precipitation [9].

Application Notes:

- Photo-iniferter RAFT (without photocatalyst) works effectively with trithiocarbonates that directly undergo photolysis [4].

- PET-RAFT provides greater flexibility in wavelength selection and oxygen tolerance [9].

- Recent advances enable scale-up to multiliter volumes using sunlight or white light irradiation [9].

Advanced Applications and Emerging Trends

RAFT Step-Growth Polymerization

RAFT step-growth polymerization represents an innovative approach that combines the versatility of step-growth polymerization with the controlled nature of RAFT chemistry [11] [4]. This methodology employs bifunctional RAFT agents and complementary monomers that undergo single unit monomer insertion (SUMI), creating polymers with embedded thiocarbonylthio groups throughout the backbone [11] [4]. These embedded RAFT agents enable unique functionality, including deconstruction via RAFT interchange with exogenous RAFT agents, generating smaller uniform species with narrow molecular weight distribution [11]. This approach provides a promising method for recycling common vinyl polymers, as the telechelic bifunctional RAFT agents generated after deconstruction allow repolymerization [11].

The Z-group approach to RAFT step-growth polymerization has been successfully implemented with both xanthate and trithiocarbonate RAFT agents [11] [12]. For instance, symmetric trithiocarbonate-based RAFT agents combined with bismaleimide monomers produce step-growth polymers that can undergo chain expansion via controlled chain growth to yield linear multiblock copolymers [11]. Similarly, xanthate-based systems with vinyl ether monomers enable construction of degradable multiblock copolymers using less activated monomers like vinyl acetate [12].

Sensing and Biomedical Applications

RAFT polymerization has found significant applications in sensing and biomedical fields due to its ability to precisely incorporate functional groups and create complex polymer architectures [7]. The technique enables synthesis of functional polymers with specific recognition groups (e.g., antigens/antibodies, aptamers, molecular imprints) for selective capture of analytes, significantly improving sensor selectivity and sensitivity [7]. Additionally, RAFT polymerization serves as a powerful signal amplification method by introducing numerous signal probes (e.g., fluorescent dyes, electroactive tags) into polymer chains through controlled chain growth [7] [10].

Recent innovations include PET-RAFT electrochemical biosensors for ultrasensitive miRNA detection, where RAFT polymerization significantly amplifies detection signals [10]. These systems employ peptide nucleic acid recognition probes with RAFT agents conjugated via phosphate-Zr(IV)-carboxylate complexes, enabling controlled polymerization of electroactive monomers (e.g., ferrocenylmethyl methacrylate) for signal generation [10]. Such biosensors demonstrate remarkable sensitivity, with detection limits as low as 12.4 aM for miRNA-21, highlighting the power of RAFT-based signal amplification in diagnostic applications [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for RAFT Polymerization Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| RAFT Agents | Dithiobenzoates, Trithiocarbonates, Dithiocarbamates, Xanthates | Mediate polymerization control through reversible chain transfer [6] |

| Thermal Initiators | AIBN, ACVA | Generate primary radicals through thermal decomposition [2] |

| Photocatalysts | Erythrosin B, conjugated cross-linked phosphine (PPh3-CHCP) | Facilitate photoinduced electron/energy transfer in PET-RAFT [10] [9] |

| Monomers | Methyl acrylate, Styrene, Methyl methacrylate, Vinyl acetate | Polymerizable vinyl monomers with varying activation levels [6] |

| Solvents | 1,4-Dioxane, Toluene, DMF | Reaction medium for solution polymerization [4] |

| Spin Traps | DMPO (5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide) | ESR studies to elucidate radical initiation mechanisms [4] |

RAFT agent selection represents a critical consideration in designing controlled polymerization systems with predictable molecular weights, narrow dispersity, and high end-group fidelity. The guidelines presented herein establish a framework for matching Z and R groups to target monomers based on both empirical compatibility data and mechanistic principles. As RAFT polymerization continues to evolve through innovations in photo-mediated processes, step-growth methodologies, and advanced applications in sensing and biomedicine, rational RAFT agent design remains fundamental to success. The experimental protocols and reagent toolkit provided offer researchers practical resources for implementing these guidelines in both fundamental studies and applied polymer synthesis.

Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain Transfer (RAFT) polymerization has emerged as one of the most versatile controlled radical polymerization techniques, enabling precise synthesis of polymers with complex architectures and tailored functionalities. The fundamental principle governing RAFT polymerization revolves around its unique kinetic and thermodynamic characteristics, which allow for control over molecular weight, dispersity, and chain-end functionality. At the heart of the RAFT process lies a degenerative chain-transfer mechanism mediated by thiocarbonylthio compounds (RAFT agents), which establishes a dynamic equilibrium between active and dormant polymer chains [1]. This equilibrium is crucial for minimizing termination reactions and ensuring uniform chain growth throughout the polymerization process.

The kinetics of RAFT polymerization are characterized by several distinct stages: initiation, pre-equilibrium, re-initiation, main equilibrium, propagation, and termination. Unlike conventional free radical polymerization, where chain termination occurs rapidly and unpredictably, RAFT polymerization maintains a low concentration of active radicals at any given time, significantly reducing termination events and enabling living characteristics [13]. The thermodynamic driving forces governing the RAFT equilibrium are influenced by multiple factors including the structure of the RAFT agent, monomer reactivity, temperature, and solvent environment. Understanding the intricate balance between these kinetic and thermodynamic parameters is essential for optimizing RAFT polymerization processes for specific applications, particularly in biomedical and pharmaceutical fields where precise polymer characteristics are critical [14].

Kinetic Principles in RAFT Polymerization

Fundamental Rate Processes

The kinetic framework of RAFT polymerization comprises several interconnected processes that collectively determine the overall rate of polymerization and the quality of the resulting polymer. The core kinetic scheme involves conventional radical polymerization steps superimposed with reversible chain transfer equilibria. Initiation begins with the decomposition of a radical initiator (e.g., AIBN), generating primary radicals that react with monomer to form propagating radicals [1]. Propagation occurs as these propagating radicals add successive monomer units, while termination happens when two propagating radicals react with each other [13].

The distinctive kinetic feature of RAFT polymerization is the RAFT equilibrium, which consists of two interconnected cycles. In the pre-equilibrium, a propagating radical (Pn•) reacts with the RAFT agent to form an intermediate radical, which subsequently fragments to yield a polymeric RAFT agent and a new radical (R•). This R• species then initiates a new polymer chain in the re-initiation step. The main equilibrium involves the reversible transfer of radical activity between active and dormant chains through the same addition-fragmentation mechanism [1]. The rate of polymerization (Rp) in photo-mediated RAFT systems has been shown to follow a three-half order dependence on monomer conversion, with the relationship expressed as:

[Rp = -\frac{d[M]}{dt} = kp[P•][M] \approx k'[M]^{3/2}]

where (k_p) is the propagation rate constant, [P•] is the concentration of propagating radicals, [M] is the monomer concentration, and k' is an apparent rate constant that incorporates the various equilibrium constants [4].

Key Kinetic Parameters and Optimization

The control over RAFT polymerization kinetics is highly dependent on several adjustable parameters. Temperature significantly influences the rate of initiation, propagation, and the RAFT equilibrium constants. For instance, in the RAFT polymerization of p-acetoxystyrene, increasing temperature from 70°C to 80°C resulted in a three-fold increase in polymerization rate [15]. The initiator concentration determines the radical flux, with higher initiator concentrations generally accelerating the polymerization but potentially leading to increased termination products. Research has demonstrated that increasing AIBN concentration from 5 mol% to 20 mol% (relative to RAFT agent) enhanced the polymerization rate of p-acetoxystyrene by approximately 2.7-fold [15].

The monomer-to-RAFT agent ratio directly determines the target degree of polymerization, while the RAFT agent structure (particularly the Z and R groups) profoundly affects the kinetics of the addition-fragmentation equilibrium. Solvent effects can also be significant, influencing both the rate of polymerization and the degree of control. For example, in the polymerization of p-acetoxystyrene, bulk polymerization proceeded faster than solution polymerization in 1,4-dioxane (1:1 v/v), though the solution polymerization provided better control at higher conversions [15].

Table 1: Key Kinetic Parameters and Their Effects on RAFT Polymerization

| Parameter | Effect on Polymerization Rate | Effect on Molecular Weight Control | Optimal Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Increases with temperature | Broader dispersity at higher temps | 70-80°C for many systems |

| Initiator Concentration | Increases with [I] | Reduced control at high [I] | 5-10 mol% (relative to CTA) |

| Monomer:CTA Ratio | Minimal direct effect | Determines target molecular weight | 50-400 for good control |

| Solvent Concentration | Decreases in more dilute systems | Improved control in appropriate solvents | Bulk to 1:1 monomer:solvent |

Thermodynamic Equilibrium in RAFT

The RAFT Equilibrium and Molecular Control

The thermodynamic equilibrium in RAFT polymerization represents the delicate balance between active propagating radicals and dormant polymeric RAFT species. This equilibrium is established through reversible chain transfer reactions that rapidly interchange radical activity between different polymer chains. The position of this equilibrium is governed by the relative thermodynamic stabilities of the intermediate RAFT adduct radical compared to its fragmentation products [1]. When the formation of the RAFT adduct radical is thermodynamically favorable, the concentration of active propagating species decreases, potentially leading to rate retardation compared to conventional radical polymerization.

The Z-group of the RAFT agent plays a crucial role in determining the thermodynamic stability of the C=S bond and the intermediate radical. Electron-withdrawing Z-groups enhance the reactivity of the RAFT agent toward radical addition, while also stabilizing the formed intermediate radical. The R-group must be a good leaving group relative to the propagating radical and must efficiently re-initiate polymerization. The delicate balance between the stability of the R-group radical and its reactivity toward monomer addition is essential for effective RAFT agent design [1]. Temperature also significantly influences the thermodynamics of the RAFT equilibrium, with higher temperatures generally favoring the fragmentation of the intermediate radical back to the reactants [4].

Thermodynamic Factors in Advanced RAFT Systems

Recent advances in RAFT polymerization have revealed additional thermodynamic considerations in specialized systems. In photo-mediated RAFT polymerization, including both photo-iniferter and PET-RAFT processes, light energy provides the thermodynamic driving force for the initiation step. Electron spin resonance (ESR) studies have confirmed that in photo-RAFT systems, cleavage of the end-group RAFT agent (activation pathway I) is thermodynamically favored over cleavage of the backbone RAFT agent (activation pathway II) [4]. This preference is attributed to the greater stability of the tertiary radical generated from the end-group compared to the secondary radical from the backbone.

In mechanoredox RAFT polymerization, mechanical force provides the activation energy for the RAFT process, enabling solvent-free or minimal-solvent polymerization under ball-milling conditions. This approach demonstrates how mechanical energy can shift the thermodynamic equilibrium by providing an alternative activation pathway [16]. Similarly, in PET-RAFT polymerization, the photocatalyst lowers the activation energy for RAFT agent fragmentation through electron or energy transfer, effectively altering the thermodynamic landscape of the initiation step [17]. The hierarchical pore architecture of heterogeneous COP catalysts in PET-RAFT systems further influences reaction thermodynamics by affecting mass transport and substrate adsorption [17].

Table 2: Thermodynamic Parameters and Their Influence on RAFT Equilibrium

| Parameter | Effect on RAFT Equilibrium | Impact on Polymer Properties | Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Z-Group Electronic Properties | Stabilizes intermediate radical | Affects polymerization rate and control | Select Z-group based on monomer type |

| R-Group Leaving Ability | Determines re-initiation efficiency | Impacts block copolymer synthesis | Match R-group to monomer reactivity |

| Temperature | Favors fragmentation at higher temperatures | Affects molecular weight distribution | Optimize for specific monomer/CTA pair |

| Solvent Polarity | Influences stability of intermediate species | Can affect dispersity and end-group fidelity | Choose solvent compatible with CTA and monomer |

Experimental Protocols for Kinetic and Thermodynamic Studies

Standard RAFT Polymerization Procedure for Kinetic Analysis

This protocol outlines a standardized approach for conducting RAFT polymerization with kinetic analysis, suitable for gathering data on rate constants and equilibrium parameters. The procedure is adapted from established methodologies with modifications for enhanced reproducibility [15] [18].

Materials and Equipment:

- Monomer (e.g., methyl methacrylate, p-acetoxystyrene, or oligo(ethylene glycol) acrylate)

- RAFT agent (e.g., DDMAT, CDB, or other appropriate thiocarbonylthio compound)

- Radical initiator (e.g., AIBN, ACVA)

- Solvent (e.g., 1,4-dioxane, DMF, toluene) if solution polymerization is desired

- Inert gas source (nitrogen or argon)

- Schlenk flask or sealed reaction vessel with septum

- Heating bath or thermostated reactor

- Aliquot system for sampling (optional but recommended for kinetic studies)

Procedure:

- Prepare a reaction mixture containing monomer, RAFT agent, initiator, and solvent (if used) in the desired ratios. A typical formulation for a target degree of polymerization of 100 might include: [Monomer]:[RAFT]:[Initiator] = 100:1:0.1 [15].

- Transfer the solution to a reaction vessel and degas by purging with inert gas for 20-30 minutes or through freeze-pump-thaw cycles (3 cycles recommended for optimal oxygen removal).

- Place the reaction vessel in a thermostated oil bath or heater at the desired temperature (typically 60-80°C for thermal initiation).

- For kinetic studies, remove aliquots at regular time intervals (e.g., every 30 minutes for the first 3-4 hours, then less frequently). Each aliquot should be immediately cooled to 0°C and exposed to air to quench the reaction.

- Analyze aliquots for monomer conversion (e.g., by ¹H NMR spectroscopy by monitoring the decrease in vinyl proton signals) and molecular weight parameters (by GPC).

- Continue the polymerization until the desired conversion is reached, then terminate by cooling and exposure to air.

- Purify the polymer by precipitation into a non-solvent (e.g., methanol for PMMA) and dry under vacuum.

Kinetic Analysis:

- Plot ln([M]₀/[M]ₜ) versus time to determine the apparent rate constant (kₚᵃᵖᵖ) from the slope.

- Monitor molecular weight evolution with conversion to assess the livingness of the polymerization.

- Plot dispersity (Đ) versus conversion to evaluate the level of control throughout the polymerization.

Automated RAFT Polymerization with Controlled Monomer Addition

Advanced kinetic studies often require precise control over monomer addition to investigate copolymerization parameters or to achieve specific chain architectures. This protocol describes an automated approach using robotic platforms such as the Chemspeed Swing XL system [5].

Materials and Equipment:

- Chemspeed Swing XL robotic platform or equivalent automated synthesis system

- Commercially available RAFT agents (e.g., trithiocarbonates for acrylates or acrylamides)

- Purified monomers (e.g., oligo(ethylene glycol) acrylate and fluorescein o-acrylate)

- Initiator (AIBN or ACVA)

- Anhydrous solvents (DMF, THF, or toluene) with appropriate drying

- Disposable reaction vials compatible with the automated system

- Inert atmosphere chamber or nitrogen sparging system

Procedure:

- Prepare separate stock solutions: (A) primary monomer (e.g., OEGA), RAFT agent, and initiator in solvent; (B) comonomer solution (e.g., FluA) in the same solvent.

- Load both solutions into the automated system through a vacuum/N₂-purged antechamber to maintain inert conditions.

- Program the automated system to execute one of three addition modes:

- Batch mode: Combine all reagents at the beginning of the reaction.

- Incremental addition: Add comonomer solution in discrete aliquots (e.g., 250 µL every 30 minutes over 3.5 hours).

- Continuous addition: Feed comonomer solution at a controlled rate (e.g., 0.3-1.0 mL/hr) using the syringe pump system.

- Set the reaction temperature to 70°C with continuous shaking to simulate stirring.

- Program automatic aliquot collection (50 µL) every 30 minutes for time-resolved ¹H NMR analysis.

- For NMR kinetic monitoring, use internal standards (e.g., DMF at 5 wt% of total reaction mass) and track vinyl proton signals for monomer conversion and characteristic signals for copolymer composition.

- After 12 hours, terminate the polymerization and collect the final product for further analysis.

Data Processing:

- Calculate monomer conversion from the decrease in vinyl proton signals relative to the internal standard.

- Determine copolymer composition from the integration of characteristic signals (e.g., fluorescein aromatic protons at 6.4-6.5 ppm and ethylene glycol signals at 3.9-4.1 ppm).

- Plot cumulative composition and instantaneous composition as functions of conversion to assess monomer sequence distribution.

Visualization of RAFT Kinetic and Thermodynamic Relationships

RAFT Polymerization Mechanism and Equilibrium

RAFT Mechanism and Equilibrium Dynamics

This diagram illustrates the key mechanistic steps in RAFT polymerization, highlighting the kinetic pathways and thermodynamic equilibria. The pre-equilibrium establishes the initial control by converting propagating radicals to dormant species, while the main equilibrium enables continuous exchange between active and dormant chains throughout the polymerization. The balance between these states determines the overall rate of polymerization and the degree of molecular weight control [13] [1].

Experimental Workflow for Kinetic Studies

Kinetic Study Experimental Workflow

This workflow outlines the systematic approach for conducting kinetic studies in RAFT polymerization. The process begins with careful experimental design, including selection of appropriate RAFT agent, initiator concentration, and temperature parameters. The automated aliquot sampling coupled with time-resolved NMR and GPC analysis enables comprehensive kinetic profiling, essential for understanding rate constants and equilibrium dynamics [5] [15].

Research Reagent Solutions for RAFT Kinetic Studies

Table 3: Essential Reagents for RAFT Polymerization Kinetic Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in RAFT System | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| RAFT Agents | DDMAT, CDB, BDMAT, CPDB | Mediates reversible chain transfer; controls molecular weight and dispersity | Select Z-group based on monomer type; R-group should be good leaving group |

| Initiators | AIBN, ACVA, V-501 | Generates primary radicals to initiate polymerization | Concentration typically 10 mol% relative to RAFT agent; affects radical flux |

| Monomers | Methyl methacrylate, p-acetoxystyrene, OEGA, NIPAM | Forms polymer backbone; reactivity influences rate and equilibrium | Purify to remove inhibitors; consider relative reactivity in copolymers |

| Solvents | 1,4-Dioxane, DMF, Toluene | Medium for polymerization; can affect rate and control | Choose based on monomer/CTA solubility; DMF preferred for automated systems |

| Catalysts | Erythrosin B, conjugated organic polymers (COP) | Photocatalysts for PET-RAFT; enable visible light initiation | Heterogeneous COP catalysts allow easy separation and recycling |

Advanced Kinetic Modeling and Optimization Approaches

Computational Methods for RAFT Kinetics

Advanced computational approaches have been developed to model the complex kinetics of RAFT polymerization, providing insights that are challenging to obtain through experimental methods alone. Monte Carlo methods offer particularly powerful tools for simulating RAFT polymerizations, as they can track individual molecules and account for complex macromolecular architectures. The mcPolymer algorithm, for instance, enables simulation of each single molecule from a huge initial batch, calculating reaction probabilities based on pseudo-random numbers [19]. This approach allows direct implementation of reactions leading to sophisticated architectures and provides access to full molecular weight distributions of all resulting polymeric materials.

Kinetic modeling of RAFT polymerization must account for several competing processes, including the pre-equilibrium, main equilibrium, potential intermediate radical termination, and conventional radical polymerization steps. For methyl acrylate polymerization mediated by cumyl dithiobenzoate, the kinetic scheme includes initiation (kₑ), propagation (kₚ), chain transfer to RAFT agent (kₜᵣ), fragmentation of intermediate (kₑ), and termination (kₜ) [19]. The rate coefficients for these processes can be estimated by modeling experimental kinetic data, such as time-resolved average molecular weight and monomer conversion data. These models have revealed that stable intermediate RAFT radicals with average lifetimes of seconds can form, potentially contributing to rate retardation effects observed in some RAFT systems [19].

Design of Experiments for RAFT Optimization

The Design of Experiments (DoE) approach provides a systematic methodology for optimizing RAFT polymerization conditions while efficiently exploring the complex factor space. Unlike traditional one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approaches, DoE enables researchers to study multiple factors simultaneously and identify significant interactions between parameters [14]. For RAFT polymerization optimization, key factors typically include reaction time, temperature, concentrations of reactants, and ratios between them.

A face-centered central composite design (FC-CCD) has been successfully applied to optimize thermally initiated RAFT solution polymerization of methacrylamide (MAAm) in water [14]. This approach generated highly accurate prediction models for responses including monomer conversion, theoretical and apparent number-average molecular weights, and dispersity. The mathematical models obtained not only facilitate thorough understanding of the system but also allow selection of synthetic targets for each individual response by predicting the respective optimal factor settings. This methodology demonstrates superior efficiency compared to conventional approaches, as it can identify optimal conditions with fewer experiments while also quantifying interactions between factors that would be missed in OFAT experimentation [14].

The kinetics and thermodynamics of RAFT polymerization represent a complex interplay of multiple competing processes that collectively determine the outcome of the polymerization. Understanding the rate control mechanisms and equilibrium dynamics enables precise manipulation of polymer properties including molecular weight, dispersity, architecture, and functionality. The experimental protocols and analytical methods outlined in this work provide researchers with standardized approaches for investigating these fundamental parameters across diverse monomer systems and reaction conditions.

Recent advances in automated synthesis platforms, computational modeling, and design of experiments methodologies have significantly enhanced our ability to probe and optimize RAFT polymerization processes. These tools enable more efficient exploration of the complex parameter space and facilitate the development of predictive models for polymer design. As RAFT polymerization continues to evolve through techniques such as photo-RAFT, mechanoredox RAFT, and heterogeneous catalytic systems, the fundamental kinetic and thermodynamic principles outlined in this work will remain essential for guiding future innovations in controlled radical polymerization.

Reversible Addition-Fragmentation chain Transfer (RAFT) polymerization has emerged as one of the most versatile controlled radical polymerization techniques due to its exceptional tolerance to functional groups and compatibility with a wide range of monomers [20] [21]. The success of RAFT polymerization fundamentally depends on understanding monomer reactivity and its profound influence on selecting appropriate RAFT agents [22]. Monomers in RAFT polymerization are classified into two primary categories based on their inherent reactivity: More-Activated Monomers (MAMs) and Less-Activated Monomers (LAMs) [20]. This classification is crucial because the reactivity of the monomer directly determines the optimal chemical structure of the chain transfer agent (CTA), particularly the Z-group, which governs the activity of the C=S bond and stabilizes the intermediate radical [20] [21]. Selecting an incompatible RAFT agent for a given monomer can lead to poor control over molecular weight, broad molecular weight distributions (high dispersity, Đ), or even complete inhibition of the polymerization [22]. This application note provides a comprehensive guide to monomer compatibility strategies, enabling researchers to design and synthesize well-defined polymers with complex architectures.

Theoretical Foundation: Monomer Classes and Their Characteristics

The reactivity of a vinyl monomer in RAFT polymerization is primarily determined by the ability of the substituent group to stabilize the propagating radical [20] [22]. This stabilization governs whether a monomer is classified as a More-Activated Monomer (MAM) or a Less-Activated Monomer (LAM).

More-Activated Monomers (MAMs)

MAMs are characterized by having a vinyl group conjugated to an aromatic ring, carbonyl, or nitrile group [20]. This conjugation allows for effective delocalization of the unpaired electron in the propagating radical, making the radical more stable and less reactive. This stabilization is the origin of their "activated" status.

Typical examples of MAMs include:

- Styrene and its derivatives

- (Meth)acrylates (e.g., methyl methacrylate, n-butyl acrylate)

- (Meth)acrylamides (e.g., N-isopropylacrylamide)

- Acrylonitrile [20] [22]

MAMs can be further subdivided based on the stability of the resulting radical. For instance, methacrylates form tertiary propagating radicals, which are more stable than the secondary radicals formed from acrylates or styrenes. This subtle difference influences the choice of the R-group on the RAFT agent, which must be a good leaving group and able to re-initiate polymerization efficiently [22] [21].

Less-Activated Monomers (LAMs)

LAMs possess a vinyl bond adjacent to a single oxygen or nitrogen atom, or have saturated carbons attached to the vinyl carbon atoms [20]. These substituents are less effective at stabilizing the propagating radical, resulting in a more reactive, less stable species.

Typical examples of LAMs include:

The high reactivity of LAMs means that the intermediate radical formed during the RAFT equilibrium is relatively stable. Consequently, RAFT agents with highly active C=S bonds (e.g., dithioesters) would generate an overly stable intermediate radical that fragments too slowly, leading to poor control. Therefore, RAFT agents with less active C=S bonds must be used to destabilize this intermediate and maintain a rapid equilibrium between active and dormant chains [20] [21].

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Common Monomers in RAFT Polymerization

| Monomer Class | Typical Examples | Radical Stability | Key Structural Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| More-Activated Monomers (MAMs) | Styrene (St), Methyl Methacrylate (MMA), n-Butyl Acrylate (nBA), Acrylamide | High | Vinyl group conjugated to aromatic ring, carbonyl, or nitrile |

| Less-Activated Monomers (LAMs) | Vinyl Acetate (VAc), N-Vinylpyrrolidone (NVP) | Low | Vinyl group adjacent to single oxygen or nitrogen atom |

RAFT Agent Selection Guide

The cornerstone of successful RAFT polymerization is the strategic pairing of the monomer with the RAFT agent's structural features. The thiocarbonylthio group (S=C-S) of the RAFT agent contains two critical substituents: the Z-group (which modulates the reactivity of the C=S bond) and the R-group (which must be a good leaving group and able to re-initiate polymerization) [20] [21].

Compatibility of RAFT Agent Types with Monomer Classes

The Z-group is the primary determinant of compatibility with monomer classes. The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for selecting the appropriate RAFT agent based on the monomer class.

Quantitative Compatibility Table

The table below provides a detailed summary of the performance of different RAFT agent classes with specific monomers, including achievable molecular weight control and dispersity (Ð).

Table 2: RAFT Agent Compatibility and Performance with Representative Monomers

| RAFT Agent Class | Z-Group | Compatible Monomer Class | Example Monomer & Performance | Typical Dispersity (Ð) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trithiocarbonate | -SC(S)S- | MAMs | n-Butyl Acrylate: Excellent control | <1.1 [23] |

| Dithioester | -C(S)S- | MAMs (esp. Styrene, Acrylates) | Styrene: Good control at high T | <1.3 [22] |

| Xanthate (MADIX) | -OC(S)S- | LAMs | Vinyl Acetate: Good control | 1.1 - 1.5 [20] |

| Dithiocarbamate | -NC(S)S- | LAMs | N-Vinylpyrrolidone: Moderate control | ~1.3 [20] |

| Pyrazole-based | Heterocyclic | Versatile (MAMs & LAMs) | MAMs: Excellent (Đ <1.1); LAMs: Moderate (Đ 1.1-1.3) [23] |

Experimental Protocols for Controlled Polymerization

Protocol 1: Thermal RAFT Polymerization of a More-Activated Monomer (n-Butyl Acrylate)

Principle: This is a conventional RAFT polymerization using a thermal radical initiator to generate radicals, which are then mediated by a suitable RAFT agent for MAMs [20] [21].

Materials:

- Monomer: n-Butyl acrylate (nBA)

- RAFT Agent: Trithiocarbonate (e.g., 2-(((Butylthio)carbonothioyl)thio)propanoic acid) [23]

- Initiator: Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN)

- Solvent: Toluene or bulk

- Equipment: Schlenk flask or reaction tube, oil bath, source of inert gas (N₂ or Ar)

Procedure:

- Formulation: In a reaction vial, combine n-butyl acrynate (5 g, 39 mmol, 100 eq.), trithiocarbonate RAFT agent (11.4 mg, 0.039 mmol, 1 eq.), and AIBN (0.64 mg, 0.0039 mmol, 0.1 eq.). Dissolve the mixture in 5 mL of toluene [20] [21].

- Degassing: Transfer the solution to a Schlenk tube. Seal the tube and degass by performing three freeze-pump-thaw cycles to remove dissolved oxygen.

- Polymerization: Place the degassed reaction vessel in a pre-heated oil bath at 70 °C with stirring.

- Monitoring: Monitor the conversion over time by withdrawing aliquots and analyzing via ( ^1H ) NMR spectroscopy.

- Termination: After reaching the desired conversion (typically 4-8 hours), cool the reaction mixture rapidly in an ice bath. Expose to air to terminate the polymerization.

- Purification: Precipitate the polymer into a large excess of cold methanol/water (10:1 v/v). Isolate the polymer by filtration or decantation, and dry under vacuum until constant weight is achieved.

Notes: The concentration of the thermal initiator (AIBN) should be low (typically 0.1-0.2 equivalents relative to the RAFT agent) to minimize chain termination and reduce dispersity [20] [21].

Protocol 2: Acid-Triggered RAFT Polymerization in Aqueous Media

Principle: This initiator-free method uses abundant acids (e.g., H₂SO₄) to trigger and control the RAFT polymerization in the dark, minimizing termination and ensuring high end-group fidelity [24].

Materials:

- Monomer: N,N-Dimethylacrylamide (DMA)

- RAFT Agent: 2-(((Butylsulfanyl)carbothioyl)sulfanyl)propanoic acid (PABTC)

- Acid Initiator: Sulfuric Acid (H₂SO₄), 1 M aqueous solution

- Solvent: Deionized Water

- Equipment: Schlenk flask, oil bath

Procedure:

- Formulation: In a Schlenk flask, dissolve the PABTC RAFT agent (1 eq., 10.8 mg) and DMA monomer (500 eq., 5.0 g) in deionized water. Add sulfuric acid (10 eq. relative to CTA) to the solution. The final pH should be approximately 1.7 [24].

- Degassing: Seal the flask and degas the solution by sparging with an inert gas (N₂ or Ar) for 20-30 minutes.

- Polymerization: Place the flask in a pre-heated oil bath at 70 °C in the dark. Allow the reaction to proceed for 10 hours.

- Monitoring: Monitor the reaction kinetics in situ by ( ^1H ) NMR spectroscopy or by withdrawing aliquots for GPC analysis.

- Termination and Purification: After achieving high conversion (>90%), cool the mixture and neutralize if necessary. Purify the polymer by dialysis against water or precipitation. Lyophilize to obtain the final product.

Notes: This method is particularly advantageous for synthesizing high molecular weight polymers and multi-block copolymers with low dispersity (Ð < 1.15) as it avoids the use of exogenous radical initiators that cause termination [24].

Protocol 3: Base-Enhanced Photo-RAFT (PET-RAFT) Under Low Light Intensity

Principle: This protocol leverages base addition to enhance the reactivity of acidic CTAs with Zn-based photocatalysts, enabling efficient polymerization under very low light intensity (microwatt range) [25].

Materials:

- Monomer: Butyl acrylate (BA) or Benzyl methacrylate (BzMA)

- RAFT Agent: Acidic CTA (e.g., 2-(Butylthiocarbonothioylthio)propanoic acid, BTPA)

- Photocatalyst: Zinc Tetraphenylporphyrin (ZnTPP)

- Base: Tetrabutylammonium hydroxide (n-Bu₄NOH) solution in MeOH

- Solvent: Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)

- Light Source: White LED (0.25 mW cm⁻² intensity)

Procedure:

- Formulation: In a glass vial, combine BA (100 eq., 1.28 g), BTPA (1 eq., 2.8 mg), and ZnTPP (0.02 eq., 0.26 mg) in DMSO (50% v/v monomer). Add 1 equivalent of n-Bu₄NOH to deprotonate the BTPA completely [25].

- Degassing: Transfer the solution to a reaction tube equipped with a magnetic stir bar. Seal the tube and degas by bubbling with argon for 15-20 minutes.

- Polymerization: Place the reaction tube in front of the white LED light source, ensuring uniform irradiation. Maintain the temperature at 50 °C with stirring.

- Monitoring: Withdraw aliquots at regular intervals to monitor conversion via NMR and molecular weight/dispersity via GPC.

- Termination: Turn off the light source and expose the reaction mixture to air.

- Purification: Precipitate the polymer into a large excess of cold hexane or methanol. Collect the polymer by filtration and dry under vacuum.

Notes: The base induces a shift in the mechanism from bimolecular to unimolecular electron transfer, drastically improving efficiency under low-energy light, which is beneficial for energy efficiency and scalability [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and their specific functions for designing RAFT polymerization experiments, drawing from commercially available and research-grade reagents.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for RAFT Polymerization Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Example | Function/Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Versatile RAFT Agents | 900161 (Sigma-Aldrich) | Aqueous/organic soluble; excellent control for both 2° and 3° MAMs with Đ <1.1 [23]. |

| Specialized RAFT Agents | 900157 (Pyrazole, Sigma-Aldrich) | "Versatile" organic-soluble agent for all monomer classes (MAMs & LAMs); low odor [23]. |

| Thermal Initiators | Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN), VA-044 | Source of radicals in thermal RAFT; use at low concentration (0.1-0.2 eq. vs. CTA) [20] [21]. |

| Photocatalysts | Zinc Tetraphenylporphyrin (ZnTPP) | Enables PET-RAFT under visible light; used in base-enhanced systems for low-energy initiation [25]. |

| Chemical Triggers | Sulfuric Acid, Tetrabutylammonium Hydroxide | Acids can trigger initiation without conventional initiators [24]; bases enhance PET-RAFT efficiency [25]. |

Advanced Strategies and Concluding Remarks

Synthesis of Block Copolymers Involving Both MAMs and LAMs

A powerful application of RAFT polymerization is the synthesis of block copolymers. However, special consideration is required when combining MAM and LAM segments. A general and robust strategy is to synthesize the MAM block first, which acts as a macro-RAFT agent for the subsequent polymerization of the LAM [23]. For example, a trithiocarbonate-capped polystyrene macro-CTA can be chain-extended with vinyl acetate by switching to a xanthate Z-group, or more conveniently, by using a versatile RAFT agent (e.g., pyrazole-based 900158) that can control both blocks without the need for agent switching [23]. This approach is fundamental to techniques like Polymerization-Induced Self-Assembly (PISA), which enables the one-pot synthesis of block copolymer nanoparticles at high solids content [20].

Mastering monomer compatibility is fundamental to exploiting the full potential of RAFT technology. The strategic selection of the RAFT agent based on the monomer's activation class—MAM or LAM—is the critical first step in designing any successful polymerization. The protocols and guidelines provided here, including conventional thermal, acid-triggered, and advanced photo-induced methods, offer researchers a comprehensive toolkit for synthesizing well-defined polymers and block copolymers with precise control over architecture, molecular weight, and dispersity. Adherence to these compatibility principles ensures high end-group fidelity and enables the creation of sophisticated polymeric materials for applications ranging from drug delivery to optoelectronics.

Reversible addition-fragmentation chain-transfer (RAFT) polymerization is a versatile reversible deactivation radical polymerization (RDRP) technique that enables precise synthesis of polymers with controlled molecular weight, narrow dispersity (Ð), and complex architectures [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, optimizing RAFT polymerization is crucial for producing well-defined polymers for biomedical applications such as drug delivery systems, polymer-drug conjugates, and biocompatible materials [26]. The critical process parameters—initiator types, temperature, and solvent effects—directly influence polymerization kinetics, control, and the properties of the resulting polymers. This protocol examines these parameters within the broader context of RAFT polymerization optimization techniques, providing structured experimental guidance for reproducible synthesis of functional polymeric materials.

Experimental Protocols

Photoiniferter (PI)-RAFT Polymerization of PEG Methacrylate

Objective: To synthesize poly(poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate) (P(PEGMA)) with narrow molecular weight distribution using photoiniferter RAFT polymerization [27] [28].

Materials:

- Monomer: PEGMA (M_n = 300 g/mol)

- RAFT agent: Trithiocarbonate chain transfer agent (CTA)

- Solvents: Anisole, DMSO, 1,4-dioxane, THF, EtOH, MeOH, DMF

- Purification gases: Nitrogen or argon

Equipment:

- Blue light LED source (λ_max = 470 nm, 1.6 mW/cm²)

- Green light LED source (λ_max = 515 nm, 1.6 mW/cm²)

- Schlenk tube or polymerization vessel with optical access

- Nitrogen sparging or freeze-pump-thaw apparatus

- Dialysis membrane (3.5 kDa molecular weight cutoff)

- Lyophilizer

- NMR spectrometer for conversion analysis

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve PEGMA monomer in selected solvent (50 vol%, 1.75 M) with [M]_0:[CTA] = 100:1 [28].

- Degassing: Sparge the solution with nitrogen gas for 1 hour to remove oxygen [28].

- Photopolymerization:

- Irradiate the reaction mixture at controlled temperature (12-40°C)

- For blue light: irradiate for 1.5 hours

- For green light: irradiate for 4 hours

- For switched initiation: irradiate with blue light for 0.5 hours then green light for 2.5 hours [28]

- Monitoring: Collect samples at various time points for NMR analysis to determine monomer conversion [28].

- Purification: Terminate polymerization by exposing to oxygen or cooling. Dialyze against deionized water using 3.5 kDa membrane for 2 days, then lyophilize to isolate polymer [28].

Analysis:

- Conversion: Calculate via ^1H NMR by comparing integrals of monomer methylene protons (4.23 ppm) and polymer methylene protons (4.01 ppm) [28].

- Molecular Weight and Dispersity: Determine via size exclusion chromatography (SEC).

- Kinetic Parameters: Calculate propagation constant (kp), chain transfer constant (Ctr), and Arrhenius parameters [27].

RAFT Polymerization of N-(2-hydroxypropyl) methacrylamide (HPMA)

Objective: To synthesize well-defined poly(N-(2-hydroxypropyl) methacrylamide) (PHPMA) in various solvents, examining hydrogen bonding effects [26].

Materials:

- Monomer: HPMA

- RAFT agent: Chain transfer agent (e.g., trithiocarbonate)

- Initiator: VA-044 or AIBN

- Solvents: Water, methanol, 2-propanol, acetonitrile, DMF, DMSO, DMAC

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Use [monomer]:[CTA]:[initiator] = 1400:10:1 [26].

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve HPMA, CTA, and initiator (VA-044) in 6.2 mL of selected solvent or buffer [26].

- Degassing: Perform three freeze-pump-thaw cycles under high vacuum (<10 Pa) [26].

- Polymerization: Heat at 45°C for prescribed time [26].

- Termination: Cool rapidly in ice water and expose to air [26].

- Purification: Dialyze and lyophilize for polymer isolation [26].

Analysis:

- Hydrogen Bonding Effects: Use variable temperature ^1H NMR to investigate solvent-polymer interactions [26].

- Molecular Characterization: Determine molecular weight, dispersity, and conversion via SEC and NMR [26].

- Chain Extension: Test retention of RAFT end-group functionality by chain extension experiments [26].

Quantitative Data Analysis

Solvent and Temperature Effects in PI-RAFT Polymerization

Table 1: Solvent Performance in PI-RAFT Polymerization of PEGMA at Different Temperatures [27] [28]

| Solvent | Temperature (°C) | Dispersity (Ð) | Chain Transfer Constant (C_tr) | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anisole | 40 | 1.30 | >1 (decreases with temperature) | Best solvent, maintains low Đ even at elevated temperature |

| Anisole | 25 | <1.30 | >1 | Good control |

| Anisole | 12 | <1.30 | >1 | Good control |

| DMSO | 40 | >1.30 | >1 | Moderate control |

| DMSO | 31 | >1.30 | >1 | Moderate control |

| DMSO | 25 | >1.30 | >1 | Moderate control |

| 1,4-Dioxane | 40 | >1.30 | >1 | Moderate control |

| 1,4-Dioxane | 32 | >1.30 | >1 | Moderate control |

| 1,4-Dioxane | 22 | >1.30 | >1 | Moderate control |

Table 2: Solvent Effects on RAFT Polymerization of HPMA [26]

| Solvent | Conversion (%) | Dispersity (Ð) | Hydrogen Bonding Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMAC | >90 | ~1.20 | Moderate |

| H₂O | >90 | ~1.20 | Strong, beneficial |

| Methanol | ~80 | ~1.25 | Strong |

| DMSO | ~70 | ~1.30 | Moderate |

| Aprotic solvents (e.g., DMF) | <70 | >1.30 | Inter-chain hydrogen bonding causes retardation |

Initiator Systems for RAFT Polymerization

Table 3: Initiator Types and Applications in RAFT Polymerization [1] [29] [21]

| Initiator Type | Examples | Temperature Range | Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Azo Initiators | AIBN, ACVA, V-60 | 50-70°C (AIBN), 45°C (VA-044) | Conventional RAFT for various monomers | Wide compatibility, predictable decomposition |

| Photoiniferters | Direct CTA activation | Room temperature to 40°C | PI-RAFT of PEGMA, acrylates, methacrylates | No additional initiator needed, oxygen tolerance, temporal control |

| Photoredox Catalysts | Organocatalysts, metal complexes | Room temperature | PET-RAFT, controlled polymerization | Mild conditions, visible light activation |

| Redox Initiators | Persulfate systems | Room temperature to 40°C | Aqueous RAFT polymerization | Low temperature initiation |

Visualization of RAFT Optimization Workflow

RAFT Parameter Optimization Workflow

This diagram illustrates the decision pathway for optimizing critical parameters in RAFT polymerization, highlighting the interconnected relationships between monomer selection, RAFT agent choice, initiation method, solvent selection, and temperature control [27] [26] [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for RAFT Polymerization Optimization [27] [26] [29]

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| RAFT Agents (CTAs) | Trithiocarbonates, Dithioesters, Xanthates, Dithiocarbamates | Mediates reversible chain transfer, controls molecular weight and dispersity | Select based on monomer type: Trithiocarbonates for MAMs, Xanthates for LAMs |

| Thermal Initiators | AIBN, ACVA, V-60, VA-044 | Generates primary radicals to initiate polymerization | Decomposes thermally at specific temperatures; concentration affects livingness |

| Photoiniferters | Trithiocarbonates (blue light), Dithiocarbamates | Directly activated by light, serves as both initiator and CTA | Enables spatial and temporal control; oxygen tolerant |

| Solvents | Anisole, DMSO, DMAC, Water, Alcohols | Medium for polymerization, affects kinetics and control | Anisole optimal for PEGMA; water beneficial for HPMA; avoid inter-chain H-bonding in aprotic solvents |

| Monomers | PEGMA, HPMA, Styrenics, (Meth)acrylates | Building blocks for polymer synthesis | PEGMA for biomedical applications; HPMA for drug conjugates; consider reactivity in RAFT equilibrium |

The optimization of initiator types, temperature, and solvent effects represents fundamental considerations in designing efficient RAFT polymerization processes. Recent advances in photoiniferter systems demonstrate that solvent selection profoundly influences polymerization control, with anisole emerging as particularly effective for maintaining low dispersity even at elevated temperatures [27] [28]. The critical relationship between solvent properties and hydrogen bonding interactions further highlights the need for systematic evaluation of solvent effects for each monomer system [26]. By implementing the protocols and analytical methods outlined in this document, researchers can achieve precise control over polymer characteristics essential for pharmaceutical applications, including narrow molecular weight distributions, preserved chain-end functionality, and tailored material properties. These optimization principles provide a foundation for advancing RAFT polymerization techniques toward more efficient and reproducible synthesis of functional polymeric materials for drug delivery and other biomedical applications.

Advanced RAFT Methodologies: Automated, Photo-Mediated, and Application-Specific Protocols

Advances in automation, robotics, and high-throughput experimentation (HTE) are transforming materials discovery, catalysis, and polymer synthesis. [5] Controlled radical polymerization (CRP) techniques, particularly reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization, offer a robust platform for automation due to their broad monomer scope, operational simplicity, and ability to produce polymers with well-defined architectures. [5] RAFT polymerization is particularly attractive for systematic kinetic studies because it is compatible with thermal and photochemical reactions and can tolerate a wide range of solvents, functional groups, and reaction conditions. [5] This application note details automated RAFT copolymerization strategies using a Chemspeed robotic platform capable of executing batch, incremental, and continuous monomer addition workflows under inert conditions, specifically for synthesizing fluorescent polymers for biomedical applications. [5]

Comparative Analysis of Automated RAFT Methodologies

Performance Metrics Across Addition Methods

Automated RAFT polymerizations of oligo(ethylene glycol) acrylate (OEGA) with fluorescein o-acrylate (FluA) were performed using three distinct methodologies on a Chemspeed Swing XL platform. [5] The table below summarizes the key performance characteristics of each method:

Table 1: Performance comparison of automated RAFT addition methodologies

| Addition Method | Key Characteristics | FluA Distribution | Optical Properties | Optimal Solvent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batch | All components mixed initially; simplest workflow | Blocky, FluA-rich segments near chain end | Promotes self-quenching and aggregation | DMF |

| Incremental | 250 µL aliquots added every 30 min over 3.5 hr | More uniform than batch | Improved optical clarity | DMF |

| Continuous | Comonomer fed at 0.3-1.0 mL/hr over several hours | Most uniform, randomized distribution | Optimal transparency and fluorescence | DMF |

Kinetic Profiling and Analytical Monitoring

Reaction kinetics were monitored via time-resolved ^1H NMR spectroscopy with automatic aliquot collection (50 µL every 30 min for batch and incremental methods; hourly for continuous flow). [5] The emerging Hb signal (6.4-6.5 ppm) from the fluorescein side chain was used to track monomer conversion, compared to the emerging Hc signal (3.9-4.1 ppm) from the ethylene glycol side chain to evaluate instantaneous copolymer composition. [5] FluA consistently demonstrated higher reactivity than OEGA, reaching near-complete conversion within the first 2-3 hours of polymerization in both batch and incremental modes. [5] Even under continuous flow conditions with FluA added gradually over periods up to three hours, FluA conversion was nearly complete by the end of the reaction, while residual OEGA remained. [5] The 3.5-hour timeframe for comonomer addition and 12-hour total polymerization duration were selected based on prior kinetic studies demonstrating high monomer conversions and reproducible copolymer compositions. [5]

Experimental Protocols

Automated Platform Configuration

The automated workflow was implemented using a Chemspeed Swing XL robotic synthesis platform at the NSF BioPACIFIC Materials Innovation Platform. [5] Key system capabilities include:

- Inert Atmosphere Maintenance: Nitrogen sparging and vacuum/N₂-purged antechamber for deoxygenated conditions [5]

- Temperature Control: Reactions conducted at 70°C with shaking to simulate stirring [5]

- Automated Sampling: Capability for automatic aliquot collection for time-resolved analysis [5]

- Flexible Fluid Handling: Precision dispensing for incremental and continuous addition protocols [5]

Reagent Preparation