Advanced Polymer Composites for Soft Robotics: Materials, Manufacturing, and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive review of the latest advancements in polymer composites for soft robotics, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical fields.

Advanced Polymer Composites for Soft Robotics: Materials, Manufacturing, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of the latest advancements in polymer composites for soft robotics, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical fields. It explores the foundational principles of stimuli-responsive materials, including electroactive polymers, magnetic composites, and shape memory systems. The scope covers cutting-edge manufacturing techniques like 3D printing, methodological approaches for creating actuators and sensors, and optimization strategies to overcome material limitations. Finally, it presents a comparative analysis of material performance, validating their potential in transformative biomedical applications such as targeted drug delivery, minimally invasive surgery, and compliant prosthetic devices.

The Building Blocks of Soft Robotics: Understanding Polymer Composites and Their Actuation Mechanisms

The field of soft robotics has transformed drastically in this century, with a pronounced focus on developing machines that are inherently safe, adaptive, and resilient. These robots, characterized by their elasticity and impact resistance, are particularly well-suited for challenging environments, from navigating debris fields to interacting safely with humans [1]. However, the very flexibility that defines soft robots often undermines their structural integrity and limits their movement precision, leading to challenges such as diminished speeds and a dependency on open-curve movement paths [1]. Polymer composites have emerged as a key enabler to overcome this paradox, allowing designers to synergize the strengths of soft and rigid materials within monolithic structures. This document, framed within a broader thesis on polymer composites, provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols to guide researchers in the fabrication and evaluation of these advanced materials for next-generation soft robotic systems.

Key Developments and Material Solutions

Recent breakthroughs in material design and fabrication are directly addressing the core limitations of soft robotics. The following table summarizes two significant advancements that inform the subsequent protocols.

Table 1: Recent Advances in Polymer Composites for Soft Robotics

| Development | Material System | Key Property Achieved | Demonstrated Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Resin Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (FRP) [2] | Epoxy resins (rigid and flexible) combined with fibers | Selective control of rigidity and flexibility; Flexural modulus of 6.95 GPa (rigid) and 0.66 GPa (foldable) [2] | Deployable space structures (e.g., solar panels); Transformer-like robot joints [2] |

| Multi-Material Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) [1] | Thermoplastic Polyurethanes (TPUs) of varying Shore hardness (75D, 95A, 85A) | Bending radius < 0.5 mm in foldable sections; High strain tolerance under repetitive cycles [1] | Legged quadruped robots capable of operating on sand, soil, and rock [1] |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed methodology for fabricating and characterizing multi-material polymer composites, based on the FDM framework [1].

Protocol: Fabrication of Multi-Material Tensile Specimens

Objective: To create and test the interfacial strength between polymer composites with different Shore hardness values.

Materials & Equipment:

- Materials: Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU) filaments with Shore hardness levels of 75D, 95A, and 85A.

- Software: Computer-Aided Design (CAD) software.

- Hardware: Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) 3D printer equipped with a tool-changer and multiple extruders.

Procedure:

- Design: Using CAD software, design standard tensile testing specimens (e.g., conforming to ASTM D638) that incorporate three distinct interfacing methods within their gauge length:

- Straight Interface: A simple, planar interface between the two materials.

- Dovetail Joint: An interlocking joint with a trapezoidal profile.

- Finger Joint: An interlocking joint with a rectangular, comb-like profile.

- Design Note: Maximize the contact area of dovetail and finger joints within the constraints of the specimen size and the printer's resolution [1].

- Preparation: Load the different TPU filaments into separate extruders on the tool-changer.

- Printing: Initiate the sequential printing process. The tool-changer will deposit the different materials within a single layer according to the digital design. Note that the sequential printing allows the previously extruded material to cool, which presents a fusion challenge compared to single-material prints [1].

- Control Group: Fabricate additional specimens from uniform (single-material) TPU to serve as a baseline and to assess any strength degradation in the multi-material prints [1].

Protocol: Tensile and Cyclic Testing

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the mechanical properties and durability of the fabricated multi-material specimens.

Materials & Equipment:

- Universal tensile testing machine.

- Cyclic fatigue testing apparatus (following ASTM standards).

- Fabricated tensile specimens.

Procedure:

- Tensile Test:

- Mount a specimen in the tensile tester.

- Apply a uniaxial tensile force at a constant strain rate until specimen failure.

- Record the stress-strain data throughout the test.

- Calculate the Young's Modulus for each specimen from the linear elastic region of the stress-strain curve [1].

- Document the ultimate tensile force at which failure occurs for each interface type [1].

- Cyclic Fatigue Test:

- Mount a new specimen in the cyclic testing apparatus.

- Subject the specimen to a minimum of 10,000 cycles of tensile loading and unloading at a stress level relevant to the target application (e.g., below 0.9 MPa for walking motions) [1].

- Monitor and record the specimen for signs of delamination or failure.

Data Presentation and Analysis

The experimental protocols yield quantitative data critical for material selection and design.

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of Multi-Material Interfaces [1]

| Material Combination | Interface Type | Key Mechanical Behavior | Performance Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| TPU 75D / 95A / 85A | Straight | Separation at low-stress levels; smallest contact surface area. | Insufficient for high-force applications. |

| TPU 75D / 95A / 85A | Dovetail & Finger Joints | Withstood stress > 4x operational requirement (≥ 4 MPa vs. ~0.9 MPa); endured >10,000 cycles. | Recommended for reliable operation; provides mechanical locking. |

| All Combined Specimens | All | Young's Modulus values between constituent materials; behavior dominated by the more elastomeric component. | Enables tuning of material properties for specific robot functions. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Multi-Material Soft Robotics Research

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU) Filaments | A class of flexible, durable, and abrasion-resistant polymers. Varying Shore hardness (e.g., 75D, 95A, 85A) allows for graded stiffness. | Used as the primary material for printing soft robotic mechanisms and joints [1]. |

| Multi-Resin Epoxy System | A two-component (rigid & flexible) resin system for Fiber-Reinforced Polymers (FRPs). | Enables creation of monolithic composites with selectively patterned rigidity for deployable structures [2]. |

| FDM 3D Printer with Tool-Changer | A fabrication system with multiple extruders for printing with different materials without manual intervention. | Critical for automated fabrication of complex, multi-material soft robotic structures [1]. |

| Dovetail & Finger Joint Interfaces | Mechanical interlocking features designed into the CAD model to enhance bonding between dissimilar materials. | Significantly improves interfacial strength in multi-material prints, preventing delamination under load [1]. |

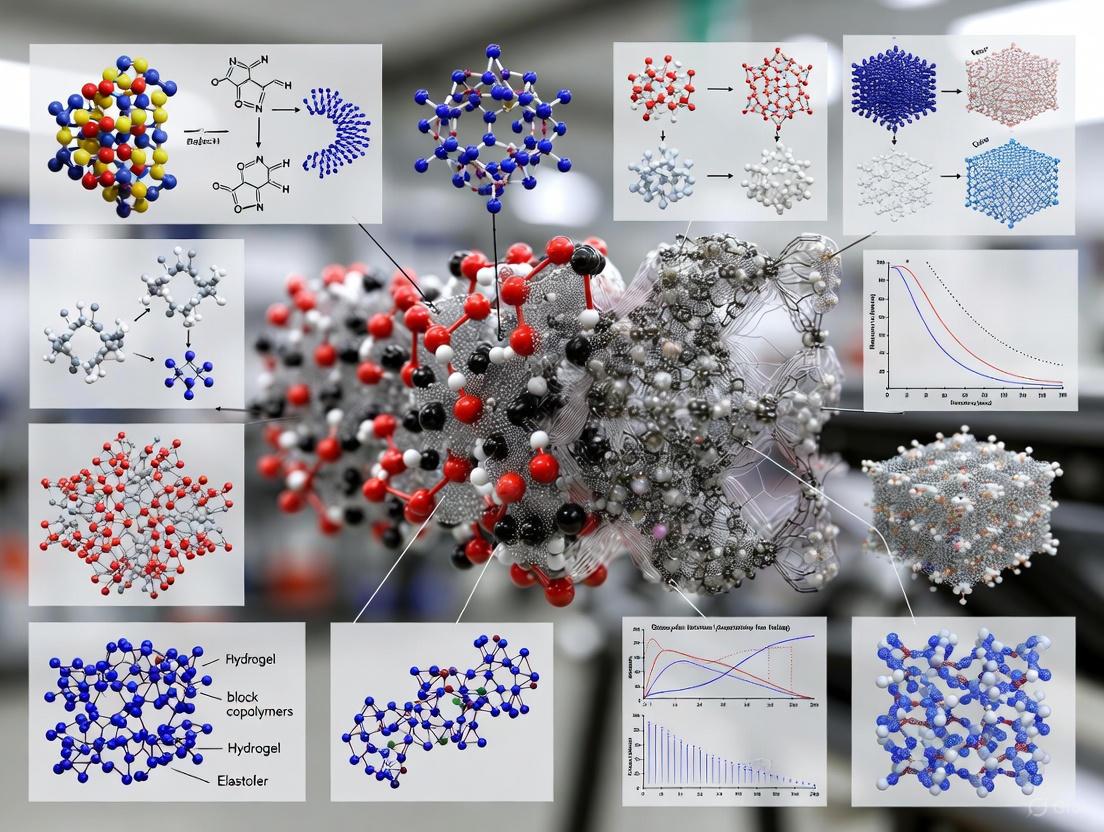

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and design workflow for developing polymer composite-based soft robots, from concept to functional validation.

Soft Robotics Development Workflow

Electroactive polymers (EAPs) represent a versatile class of smart materials capable of converting electrical energy into mechanical motion and vice versa, positioning them as foundational components for the next generation of soft robotics and artificial muscles [3] [4]. Their high strain capability, flexibility, low density, and mechanical compliance make them ideal for applications where rigid robots are unsuitable, such as biomedical devices, wearable electronics, and adaptive grippers that interact safely with humans or delicate objects [4] [5]. The intrinsic properties of EAPs—including affordability, ease of fabrication, high power density, and silent operation—allow them to eliminate the need for traditional gears, bearings, and other complex mechanical components, thereby enabling more natural, fluid movements that closely mimic biological tissues [4] [5].

The historical development of EAPs dates back to 1880 with Wilhelm Roentgen's early experiments on electrically-induced deformation in rubber [3]. Significant milestones include the discovery of piezoelectric polymers in the 1920s, the introduction of ionic polymer-metal composites (IPMCs) and conductive polymers in the 1970s-80s, and the emergence of dielectric elastomer actuators (DEAs) in the 1990s [3]. Recent advancements in additive manufacturing, nanocomposite engineering, and AI-integrated control systems have further expanded their potential, making EAPs central to the development of intelligent, adaptive soft robotic systems [3] [4]. For researchers and scientists focused on polymer composites for soft robotics, understanding the fundamental classification, operational mechanisms, and application-specific selection criteria for EAPs is paramount.

Classification and Fundamental Operating Mechanisms

EAPs are broadly categorized into two distinct classes based on their underlying activation mechanism: Electronic EAPs and Ionic EAPs [3] [4] [6]. This classification is critical as it dictates fundamental performance parameters such as driving voltage, response speed, achievable strain, and suitable application environments. The following sections delineate the operational principles and material characteristics of each category.

Electronic EAPs (Field-Activated)

Electronic EAPs operate through Coulombic forces generated by the application of an external electric field, leading to electrostatic deformation without significant ionic movement [3] [4]. Their actuation mechanism is governed by Maxwell stress, which causes a compressive pressure on the polymer, leading to lateral expansion. This pressure P can be described as:

P = ϵ₀ϵᵣ(V/d)²

where ϵ₀ is the vacuum permittivity, ϵᵣ is the relative permittivity of the elastomer, V is the applied voltage, and d is the thickness of the film [3]. The resulting actuation strain ε is approximately ε = P/Y, where Y is the elastic modulus of the material [3].

- Dielectric Elastomers (DEs): These function as variable capacitors, typically consisting of a thin elastomeric dielectric film (e.g., acrylics, silicones, polyurethanes) sandwiched between two compliant electrodes [3] [4]. Upon voltage application, electrostatic forces compress the film, causing it to expand in area. They are known for large strain responses (>100%) but typically require high voltages (1–10 kV) [3].

- Ferroelectric Polymers: Materials like polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) and its copolymers exhibit piezoelectric properties, generating a mechanical strain in response to an applied electric field due to molecular dipole alignment. They are valuable in energy harvesting, biomedical sensors, and MEMS [3] [4].

- Liquid Crystal Elastomers (LCEs): These materials undergo molecular reorientation under electric fields, enabling programmable and reversible shape changes. They are being explored for adaptive optics, artificial muscles, and biomedical devices [3] [4].

Ionic EAPs (Ion-Activated)

Ionic EAPs deform due to the migration of ions within the polymer structure when stimulated by a low-voltage potential (typically < 5 V) [3] [6]. The actuation is driven by electrochemical processes, such as redox reactions, which induce volume changes in the material.

- Ionic Polymer-Metal Composites (IPMCs): These consist of a hydrated ion-conductive polymer membrane (e.g., Nafion) sandwiched between metal electrodes. Application of a low voltage causes cation migration and subsequent swelling/contraction, resulting in a bending motion [3] [7].

- Conducting Polymers (CPs): Polymers like polypyrrole (PPy), polyaniline (PANI), and Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) undergo reversible volume changes during electrochemical oxidation and reduction (redox) cycles. Ions and solvent molecules move into and out of the polymer matrix to balance charge, leading to expansion and contraction [6].

- Ionic Gels and Polyelectrolyte Gels: These networks swell or contract under an electric field due to ion mobility and electrostatic interactions, making them suitable for drug delivery systems and soft actuators [3] [7].

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental operational mechanisms and common device architectures for these two primary classes of EAPs.

Comparative Analysis: Ionic vs. Electronic EAPs

Selecting the appropriate EAP for a specific application in soft robotics requires a clear understanding of the performance trade-offs between ionic and electronic types. The following tables provide a quantitative and qualitative comparison of their key characteristics.

Table 1: Performance and Operational Parameters of Ionic vs. Electronic EAPs

| Parameter | Ionic EAPs | Electronic EAPs |

|---|---|---|

| Actuation Voltage | Low (1–5 V) [4] [6] | High (hundreds of V to several kV) [3] [6] |

| Power Consumption | Low power, but often requires continuous current for holding position [6] | Low current, primarily reactive power, can hold position with voltage [3] |

| Typical Strain | Moderate to high (e.g., Conducting Polymers: ~6%; IPMCs: large bending) [4] [6] | Very high (e.g., Dielectric Elastomers: >100%) [3] [4] |

| Response Speed | Slower (hundreds of milliseconds to seconds) due to ion diffusion [6] | Faster (millisecond range) [3] [6] |

| Mechanical Force/Stress | Lower force output | High force output; high energy density [4] |

| Key Advantages | Low-voltage operation, significant bending displacements, suitable for wet environments [3] [7] | Fast response, high strain and energy density, stable in dry environments, good positional holding [3] [4] |

| Major Challenges | Shorter cycle life due to electrolyte degradation, prone to creep, often requires liquid electrolyte [6] | Requires high-voltage circuitry, viscoelastic creep, premature dielectric breakdown [3] |

Table 2: Material Composition and Application Suitability

| Aspect | Ionic EAPs | Electronic EAPs |

|---|---|---|

| Common Materials | Conducting Polymers (PPy, PANI, PEDOT), Ionic Polymers (Nafion), Ionic Liquids/Gels [3] [6] | Dielectric Elastomers (Acrylics, Silicones, TPU), Ferroelectric Polymers (PVDF), Liquid Crystal Elastomers [3] [4] |

| Typical Electrodes | Platinum, Gold, Carbon-based materials, Conductive polymers [3] [6] | Carbon grease, graphite, silver nanoparticle inks, carbon nanotubes, thin metallic films [3] [4] |

| Ion/Charge Carrier | Mobile ions (H⁺, Li⁺, Na⁺, ionic liquids) [7] [6] | Electrons (electronic polarization) [3] |

| Ideal Applications | Biomedical devices (drug delivery), bio-inspired robotics, micro-manipulators, underwater applications [3] [4] | Soft grippers, tunable lenses, haptic interfaces, loudspeakers, large-stroke actuators, aerospace morphing structures [3] [4] |

Experimental Protocols for EAP Actuator Fabrication and Testing

This section provides detailed methodologies for fabricating and characterizing two common types of EAP actuators, serving as a practical guide for researchers developing functional prototypes for soft robotics.

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a Dielectric Elastomer Actuator (DEA)

Principle: A DEA operates as a compliant capacitor. Electrostatic Maxwell stress induced by a high electric field causes thickness compression and area expansion of the dielectric layer [3].

Materials:

- Dielectric Layer: VHB 4905/4910 tape (3M), Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), or Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU).

- Compliant Electrodes: Carbon grease, carbon black/silicone mixtures, screen-printable carbon or silver ink, PEDOT:PSS.

- Frame: Rigid (e.g., acrylic) or flexible (e.g., PET) frame to support the pre-strained film.

Procedure:

- Film Pre-straining: Mount a sheet of the dielectric elastomer (e.g., VHB) on a mechanical stretcher. Apply a biaxial pre-strain (e.g., 300% x 300%). Pre-strain enhances actuation strain and prevents electromechanical instability [3]. Transfer the pre-strained film onto a rigid or flexible support frame.

- Electrode Deposition: Apply compliant electrode material to both sides of the pre-strained dielectric film, ensuring full coverage of the active area. Common methods include:

- Curing/Setting: Allow the electrode material to set. For silicone-based electrodes, this may involve thermal curing. Carbon grease can be used immediately.

- Electrical Connections: Attach thin, flexible wires (e.g., copper tape) to the electrode areas using a small amount of conductive adhesive or the electrode material itself.

Protocol 2: Fabrication of a Conducting Polymer (CP) Bilayer Actuator

Principle: A bilayer actuator is constructed by laminating a conducting polymer film to a passive, flexible substrate. Volume changes in the CP during electrochemical redox cycling induce bending motion [6].

Materials:

- Conducting Polymer (CP): Polypyrrole (PPy) or Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) film.

- Passive Substrate: Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF), polyimide tape, or thin polyester.

- Electrolyte: Ionic liquid (e.g., 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, [EMIM][BF₄]) or aqueous salt solution (e.g., LiCl).

- Electrodes: Platinum or stainless steel foil for counter and reference electrodes.

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Cut the passive substrate to the desired dimensions. Clean the surface with ethanol to ensure good adhesion.

- CP Film Synthesis/Adhesion:

- Electropolymerization: Immerse the substrate (acting as a working electrode) along with counter and reference electrodes in a monomer solution (e.g., 0.1 M pyrrole). Apply a constant current or potential to electropolymerize a CP film directly onto the substrate [6].

- Adhesive Lamination: Alternatively, a pre-synthesized CP film can be bonded to the substrate using a thin layer of a compatible adhesive or by hot-pressing.

- Actuator Assembly: Attach electrical leads to the CP layer and the metal substrate (if conductive) using silver paint or conductive tape. If the substrate is insulating, the lead is attached only to the CP layer.

- Electrochemical Actuation:

- Immerse the actuator strip in the chosen electrolyte.

- Connect the CP layer as the working electrode and a separate metal foil as the counter/reference electrode.

- Using a potentiostat, apply a low-voltage square wave or cyclic voltammetry (typically between -1.0 V and +0.5 V vs. reference) to induce redox reactions. Oxidation causes ion insertion and swelling, while reduction causes ion expulsion and contraction, resulting in reversible bending [6].

Protocol 3: Performance Characterization of an EAP Actuator

Objective: To quantitatively measure the free displacement, blocking force, and frequency response of a fabricated EAP actuator.

Setup:

- Test Chamber: If testing ionic EAPs, a container for the electrolyte with integrated electrodes.

- Optical Measurement: A laser displacement sensor (e.g., Keyence) or a camera-based motion tracking system.

- Force Measurement: A micro-force sensor (e.g., from Futek or Transducer Techniques).

- Signal Generation: A function/arbitrary waveform generator.

- Data Acquisition: A computer with DAQ card and control software (e.g., LabVIEW, Python).

Procedure:

- Free Displacement Test: Clamp one end of the actuator. Using the laser sensor or camera, measure the tip displacement at the free end while applying the driving signal (voltage for DEAs, potential for CPs). Record the maximum displacement for a given input.

- Blocking Force Test: Bring the force sensor into contact with the tip of the actuator, preventing movement. Apply the same driving signal and record the peak force generated by the actuator.

- Frequency Response Test: Drive the actuator with a constant-amplitude sinusoidal signal while sweeping the frequency. Measure the displacement amplitude at each frequency to plot a Bode diagram and identify the actuator's bandwidth and resonant frequency.

- Cycle Life Test: Subject the actuator to continuous cycling (e.g., 10,000 cycles) at a specified frequency and amplitude. Periodically measure displacement and force to monitor performance degradation over time [9] [6].

The workflow for the fabrication and characterization of a typical EAP actuator is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for EAP Actuator Research

| Material/Reagent | Function and Rationale |

|---|---|

| VHB 4905/4910 Tape (3M) | A widely used acrylic dielectric elastomer known for its high dielectric constant and ability to achieve large strains when pre-strained [3]. |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | A silicone-based elastomer (e.g., Sylgard 184) used as a dielectric layer; offers excellent elasticity and faster response than acrylics, though often requires additives to enhance dielectric properties [3]. |

| Polypyrrole (PPy) / PEDOT | Common conducting polymers for ionic EAPs. They undergo volume change during electrochemical redox reactions, providing the actuation mechanism [6]. |

| Nafion Membrane | A perfluorosulfonate ion-exchange membrane used as the core material for Ionic Polymer-Metal Composites (IPMCs) [3] [7]. |

| Ionic Liquids (e.g., [EMIM][BF₄]) | Serve as non-volatile, stable electrolytes for ionic EAPs, enabling operation in air and enhancing device lifetime by preventing drying [6]. |

| Carbon Grease / Carbon Black | Standard materials for creating compliant, stretchable electrodes in Dielectric Elastomer Actuators (DEAs) [3] [4]. |

| Barium Titanate (BaTiO₃) Nanoparticles | High-permittivity ceramic nanoparticles used as fillers in dielectric elastomer composites to significantly increase the dielectric constant, enabling higher actuation strain at lower fields [3]. |

| Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) | A ferroelectric polymer used for its piezoelectric properties, making it suitable for sensors and energy harvesters integrated into soft robotic systems [3] [4]. |

The strategic selection between ionic and electronic EAPs is fundamental to advancing soft robotics research. As outlined in this application note, the choice hinges on a clear trade-off between operational voltage, response speed, and strain requirements. Electronic EAPs, particularly dielectric elastomers, offer high strain and force under fast response times but necessitate high-voltage driving electronics. Ionic EAPs, such as conducting polymers and IPMCs, provide significant deformation at low voltages, ideal for biomedical and portable applications, albeit with slower response speeds and potential longevity concerns in air [3] [4] [6].

The future of EAPs in soft robotics is being shaped by several key research frontiers. The integration of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) is proving transformative, with convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and deep reinforcement learning (DRL) being deployed to mitigate viscoelastic hysteresis and enhance real-time control in complex, untethered soft robotic systems [3] [4]. The push for sustainability is driving the development of renewable and biodegradable ionic EAPs, with biopolymeric actuators expected to see significant market growth [7]. Furthermore, innovations in additive manufacturing and nanocomposite engineering are enabling the fabrication of complex, miniaturized EAP structures with enhanced performance [3] [10]. Finally, the creation of multimodal, self-powered systems that combine actuation, sensing, and energy harvesting within a single material structure represents a crucial step towards fully autonomous, intelligent soft robots [11] [12]. For researchers, focusing on these interdisciplinary areas will be key to unlocking the full potential of electroactive polymers in the next generation of soft robotic technologies.

Dielectric elastomers (DEs) are a class of electroactive polymers that demonstrate significant deformation under an applied electric field, making them exceptional candidates for soft robotics and artificial muscle applications [13] [14]. These materials function as compliant capacitors, where an elastomer film is sandwiched between two compliant electrodes. Upon voltage application, electrostatic Maxwell stress compresses the film in thickness and causes it to expand in planar area [14]. This fundamental principle enables DEs to achieve large strains, possess high energy density, and offer fast response times, closely mimicking the behavior of natural muscle [15].

The performance of dielectric elastomer actuators (DEAs) is critically dependent on the intrinsic properties of the elastomer material. The key figures of merit are a high dielectric constant to maximize electrostatic forces and a low elastic modulus to minimize mechanical resistance to deformation [16]. The interplay of these properties is encapsulated in the electromechanical sensitivity factor (β = ε/Y), which must be maximized to achieve large actuation strains at low driving electric fields [17]. This application note details the core principles, material design strategies, and experimental protocols for developing high-performance DEAs, framed within the context of advanced polymer composites for soft robotics research.

Fundamental Working Principles

The actuation mechanism of DEAs is governed by electrostatic forces arising from an applied electric field. When a voltage V is applied across the compliant electrodes, the generated Maxwell stress (P) compresses the elastomer film [18]. This stress is described by:

where ε₀ is the vacuum permittivity, εᵣ is the relative dielectric constant of the elastomer, and z is the film thickness [18]. For strains below approximately 20%, the resulting thickness strain S_z can be estimated as:

where Y is the Young's modulus of the elastomer and E is the applied electric field strength (V/z) [18] [17]. This equation highlights that the actuation strain is directly proportional to the material's electromechanical sensitivity factor, β = εᵣ/Y [17].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental working principle and key performance relationships of a Dielectric Elastomer Actuator (DEA).

Performance Metrics and Material Comparison

The advancement of DEAs relies on developing elastomer materials that exhibit large actuation strain and high energy density under low electric fields. The following table summarizes the performance characteristics of various state-of-the-art dielectric elastomers documented in recent literature.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Advanced Dielectric Elastomers

| Material System | Dielectric Constant (εᵣ) @1kHz | Young's Modulus (MPa) | Max. Actuation Strain (%) | Driving Electric Field | Energy Density (J kg⁻¹) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polar Fluorinated Polyacrylate [15] | 10.23 | ~0.09 | 253 | 46 MV m⁻¹ | 225 | Ultrahigh specific energy, fast running speed (20.6 BL s⁻¹) |

| Bimodal-Network DE [19] | 6.64 | ~0.075 | 200 | 60 V μm⁻¹ | 283 | Multiple hydrogen bonds, rapid response, low loss |

| Acrylate-Polyurethane (Acry-PU3) [17] | 3.7 | 0.083 | 28.0 | 15.34 kV mm⁻¹ | - | Molecular-level hybrid network, high actuation stability |

| PUA-PEGDA Copolymer [18] | Increased vs. pristine PUA | Increased vs. pristine PUA | - | 10 V μm⁻¹ | - | Reduced viscoelasticity, fast response (<1 s), no prestretch needed |

| MWCNT/Ecoflex Multilayer [16] | Significantly increased vs. pure Ecoflex | Maintained low | - | - | - | Layer-by-layer structure, high dielectric constant, low loss |

Material Design Strategies for Enhanced Performance

Molecular Engineering of Elastomer Networks

Molecular design is paramount for optimizing the electromechanical properties of DEs. Effective strategies include:

- Introducing Polar Groups: Incorporating highly polar chemical groups, such as fluorinated segments (e.g., 2,2,3,4,4,4-hexafluorobutyl acrylate - HFBA), directly increases the dielectric constant of the polymer. The polar CF₃ groups in HFBA, for instance, raise the dielectric constant to 10.23, compared to 4.77 for commercial VHB 4910 [15].

- Creating Bimodal Network Structures: Utilizing crosslinkers of different chain lengths creates a bimodal network. Long-chain crosslinkers (e.g., CN9021) maintain low modulus and high elongation, while short-chain crosslinkers (e.g., TPGDA) form rigid, high-density crosslinking points that enhance stress transfer and impart strain-hardening behavior, which is crucial for high energy density and mitigating electromechanical instability [19].

- Utilizing Physical Crosslinks and Dynamic Bonds: Incorporating nanodomains aggregated by long alkyl side chains (e.g., from dodecyl acrylate - DA) or multiple hydrogen bonds (e.g., via 2-hydroxyethyl acrylate - HEA) creates reversible physical crosslinks. These dynamic bonds dissociate under high strain to dissipate energy and re-form, improving toughness, reducing permanent set, and minimizing viscoelastic hysteresis [15] [19].

- Modulating Viscoelasticity with Crosslinking: Copolymerizing with polar crosslinkers like Polyethylene Glycol Diacrylate (PEGDA) reduces chain slippage and viscoelastic drift. This results in more precise and stable actuation, with a faster response time (<1 s to reach 90% of maximum actuation), eliminating the need for mechanical prestretching [18].

Composite and Multilayer Approaches

- Layer-by-Layer Composites: Constructing composites with alternating conductive (e.g., MWCNT/Ecoflex) and insulating (pure Ecoflex) layers creates a multilayer capacitor structure. This architecture significantly enhances the effective dielectric constant while maintaining low modulus and preventing the formation of conductive paths that lead to high dielectric loss and premature breakdown [16].

- Polar Crosslinking Networks: Designing polyurethane acrylate (PUA) networks copolymerized with PEGDA simultaneously addresses multiple requirements. The chemical crosslinks reduce viscoelasticity, while the polar groups in the crosslinker enhance the dielectric constant, counteracting the increased modulus from crosslinking [18].

Experimental Protocols

This protocol describes the synthesis of a high-performance DE via one-step UV photopolymerization.

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials: Table 2: Key Reagents for Polar Fluorinated Polyacrylate Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| 2,2,3,4,4,4-Hexafluorobutyl Acrylate (HFBA) | Monomer providing high dielectric constant | Highly polar fluorinated (CF₃) groups |

| 2-Ethylhexyl Acrylate (EA) | Comonomer to lower Young's modulus | Large steric hindrance side chains |

| Dodecyl Acrylate (DA) | Comonomer forming physical crosslinks | Long alkyl side chains form nanodomains |

| UV Photo-initiator | Initiates free radical polymerization | e.g., 2-Hydroxy-2-methylpropiophenone |

Procedure:

- Monomer Mixture Preparation: Mix the comonomers HFBA, EA, and DA at a predetermined molar ratio (e.g., PFED10: HFBA/EA/DA with DA at 10 mol% relative to HFBA). Add 1 wt% of UV photo-initiator relative to the total monomer mass and mix thoroughly until a homogeneous precursor solution is obtained.

- UV Curing: Pour the precursor solution into a mold. Place the mold in a UV curing chamber. Purge the chamber with an inert gas (e.g., Nitrogen) to displace oxygen. Expose the mixture to UV light for a specified duration to achieve complete polymerization.

- Film Recovery: Carefully peel the cured elastomer film from the mold. The resulting film should be transparent and uniform in thickness.

This protocol outlines the fabrication of a buckling-mode actuator that exhibits out-of-plane deformation without prestretching.

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials:

- Dielectric Elastomer Film: Synthesized PUA-PEGDA copolymer film (e.g., thickness ~0.43 mm) or commercial equivalent.

- Compliant Electrodes: Carbon grease.

- Electrical Connections: Copper tape.

- Holder: In-house built glass holder with a central hole (e.g., 2 cm x 2 cm).

- High Voltage Supply: DC power supply (e.g., capable of 0-10 kV).

- Displacement Sensor: Laser displacement sensor (e.g., Epsilon optoNCDT).

Procedure:

- Film Mounting: Secure the DE film over the hole in the glass holder, ensuring it is taut but not prestretched.

- Electrode Application: Using a stencil or mask, coat a circular area (e.g., 3 mm diameter) on the top and bottom surfaces of the film with carbon grease to form compliant electrodes. Ensure the electrodes are aligned.

- Electrical Connection: Attach copper tape to the edge of each electrode area to provide a connection to the high-voltage supply.

- Static Actuation Test: Place the laser displacement sensor to measure the vertical deflection at the center of the electrode.

- Gradually increase the applied voltage in steps (e.g., 0.5 kV every 10 seconds).

- Record the displacement at each voltage step until the breakdown field is approached.

- The actuation strain can be calculated from the displacement using geometric relations.

- Dynamic Response Test: Connect the actuator to a high-voltage amplifier driven by a function generator.

- Apply a cyclic voltage (e.g., 0.1 Hz sine wave at 10 V μm⁻¹).

- Use the laser sensor to record the displacement over time.

- The response time

t_0.9can be quantified as the time taken to reach 90% of the maximum displacement for each cycle.

The following diagram summarizes the experimental workflow for fabricating and characterizing a DEA.

Application in Soft Robotics

DEAs' large strain, high energy density, and compliance make them ideal for a wide range of soft robotics applications.

- Fast Moving and Jumping Robots: DEAs based on polar fluorinated polyacrylate have powered soft robots to an unprecedented running speed of 20.6 body lengths per second, which is 60 times faster than robots using commercial VHB and comparable to a cheetah's relative speed. These robots can also climb slopes up to 45° and carry loads 17 times their own weight [15].

- Soft Grippers and Bio-inspired Artificial Arms: DEAs enable the creation of grippers that can handle delicate or irregularly shaped objects with inherent compliance, mimicking the functionality of biological appendages [13] [19].

- Tunable Lenses and Optical Systems: The large, controllable deformation of DEAs allows for the development of lenses with electrically tunable focal lengths [13]. Furthermore, DEAs have been used to manipulate chiral liquid crystal elastomers (CLCEs) for omnidirectional color wavelength tuning in advanced photonic devices [20].

- Biomimetic Flying Robots and Linear Actuators: The high specific power of advanced DEs enables the creation of flapping-wing robots and compact linear actuators that produce substantial displacement and output force, suitable for micro-robotics and precision positioning [17] [19].

Ionic Polymer-Metal Composites (IPMCs) represent a class of electroactive polymers (EAPs) garnering significant interest in soft robotics and biomedical engineering due to their ability to function as artificial muscles [4] [21]. These smart materials are characterized by a large bending strain response under low activation voltages (typically 1–5 V), flexibility, softness, light weight, and mechanical compliance [22] [4]. The inherent capability of IPMCs to convert electrical energy into mechanical motion (actuation) and mechanical deformation into electrical signals (sensing) makes them particularly suitable for applications requiring safe human-robot interaction, miniaturization, and operation in aqueous environments [22] [23]. This document details the working principles, applications, and standardized experimental protocols for IPMCs, framing them within the broader context of advanced polymer composites for soft robotics research.

Working Principle and Material Composition

The quintessential IPMC structure is a sandwich-like laminate consisting of a thin ion-exchange polymer membrane (typically 100–200 μm thick) coated on both surfaces with conductive metal electrodes (typically 5–10 μm thick) [22] [23].

Actuation Mechanism

When a low DC voltage (1–5 V) is applied across the thickness of the IPMC, an electric field is established within the polymer electrolyte. This field drives the migration of hydrated cations (e.g., Li⁺, Na⁺) dispersed in the polymer network toward the cathode. The resultant asymmetric distribution of water and ions causes swelling near the cathode and contraction near the anode, generating a bending stress that deflects the IPMC strip toward the anode [22] [24] [21]. This process efficiently transforms electrical energy directly into mechanical motion.

Sensing Mechanism

Conversely, when an external force bends the IPMC, the internal ion-rich clusters are displaced due to the strain gradient, creating a charge imbalance detectable as a voltage (on the order of millivolts) between the two surface electrodes [23]. This self-sensing capability allows IPMCs to be used as deformation, force, or tactile sensors.

Key Material Components

The performance of an IPMC is heavily influenced by its constituent materials.

- Polymer Membrane: The most common membrane is Nafion (a perfluorosulfonic acid ionomer), prized for its strong mechanical properties and high ionic conductivity [24] [23]. Alternatives include Flemion or hydrocarbon-based polymers, which can offer cost or performance advantages [24].

- Electrodes: Precious metals like Platinum (Pt) and Gold (Au) are widely used due to their excellent conductivity and chemical stability. Palladium (Pd) is also employed, and research into carbon-based electrodes is ongoing [22] [23].

- Mobile Cations: The type of cation (Li⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, or ionic liquids) significantly impacts actuation speed, force, and the relaxation effect observed under DC voltage [22] [23].

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental actuation and sensing mechanisms of an IPMC.

Applications in Soft Robotics and Biomedicine

IPMCs' unique properties have led to their exploration in diverse fields. The table below summarizes key application areas.

Table 1: Key Application Areas for IPMC Actuators

| Application Domain | Specific Examples | Key IPMC Advantage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-inspired Robotics | Underwater robotic fish fins, jellyfish-like microrobots, snake-like swimmers, insect-inspired flapping wings | Large bending deformation, low noise, efficient in aquatic environments, low drive voltage | [22] [24] [25] |

| Biomedical Devices | Active catheter-guidewires, implantable drug delivery pumps, braille displays, endoscopic steering | Biocompatibility, softness, low-power operation, precise micro-scale control | [22] [26] |

| Opto-Mechatronic Systems | Auto-focus camera modules, optical positioners, tunable lenses | Precision positioning, miniaturization, fast response | [22] [4] |

A prominent example of a advanced application is a remote-control drug delivery implantable chip for localized cancer therapy. In this device, a small IPMC strip acts as an active cap for a drug reservoir. Upon receiving a low-voltage wireless signal, the IPMC bends to open the reservoir, releasing the drug on demand. This design addresses the limitations of passive diffusion systems by providing precise, therapist-controlled release, minimizing systemic side effects [26].

Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed methodology for fabricating and characterizing IPMC actuators, essential for research replication and development.

Fabrication Protocol: Electroless Plating with Pt Electrodes

The following protocol describes a common method for creating Pt-Nafion IPMCs [27] [25].

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for IPMC Fabrication

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example/Chemical Formula |

|---|---|---|

| Nafion Membrane | Ionic polymer backbone providing ion channels and mechanical structure. | Nafion-117 (Dupont) |

| Platinum Salt | Source for metallic electrode layer formation. | Tetraammineplatinum chloride hydrate, [Pt(NH₃)₄]Cl₂ |

| Reducing Agents | Chemically reduce metal ions to form electrodes on the polymer surface. | Sodium borohydride (NaBH₄), Hydroxylammonium chloride (NH₂OH·HCl), Hydrazine hydrate (N₂H₄·H₂O) |

| Sandpaper | Roughens membrane surface to enhance electrode adhesion and penetration. | 1600# grit |

| Cleaning Solutions | Removes organic/inorganic impurities from the membrane. | Sulfuric Acid (H₂SO₄), Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Pretreatment & Roughening: Cut a Nafion membrane (e.g., 30 mm x 29 mm) to desired dimensions. Roughen both surfaces with 1600# sandpaper to increase surface area for better electrode adhesion [27] [25]. Clean the membrane by boiling in dilute H₂SO₄ (0.5%), then H₂O₂ (15%), and finally deionized (DI) water, for 1 hour each, to remove impurities [25].

- Ion Exchange (Primary Adsorption): Immerse the cleaned membrane in an aqueous solution of [Pt(NH₃)₄]Cl₂ (approx. 3 mg Pt per mm² of membrane) for at least 14 hours. This allows Pt-complex cations to diffuse into the membrane and replace its native counter-ions (e.g., H⁺) [27] [25].

- Primary Reduction: Slowly add a warm aqueous solution of sodium borohydride (NaBH₄, 5%) to the platinum salt bath. Maintain the temperature at ~40°C. This chemical reduction step reduces the Pt ions to metallic Pt, forming a initial nanoparticle electrode layer within the surface region of the polymer. Stir for 2 hours [27].

- Secondary Reduction (Electrode Growth): To thicken and consolidate the electrode layers, perform a secondary reduction. Place the IPMC in a bath containing a solution of ammonium hydroxide, hydrazine hydrate (20%), and hydroxylammonium chloride (5%). Gradually increase the temperature from 40°C to 60°C over the course of the reaction. This step builds a denser, more conductive surface electrode [27] [25].

- Ion Exchange (Final): Rinse the fabricated IPMC thoroughly with DI water. To tailor actuation performance, immerse the IPMC in a salt solution (e.g., 1 mol/L LiCl) for several hours to exchange the mobile cations to the desired type (e.g., Li⁺) [25].

- Hydration: Store the final IPMC in DI water before testing to ensure hydration, which is critical for ion mobility.

The workflow for this fabrication process is visualized below.

Protocol for Characterizing Bending Actuation

Objective: To measure the tip displacement of a cantilevered IPMC actuator under varying voltage and frequency.

Equipment:

- Function generator

- Laser displacement sensor (or high-speed camera)

- Data acquisition system (e.g., oscilloscope)

- Clamping fixture and electrical contacts

- IPMC sample cut into a cantilever strip (e.g., 20mm x 5mm)

Procedure:

- Setup: Clamp one end of the IPMC strip securely to create a cantilever beam. Ensure good electrical contact with both surface electrodes. Position the laser displacement sensor (or camera) at the free tip of the IPMC to measure displacement [27].

- DC Characterization: Apply a low DC voltage (e.g., 1–3 V) across the IPMC electrodes. Measure the maximum tip displacement and observe any relaxation behavior (back-relaxation) over time [22].

- AC Characterization: Drive the IPMC with a sinusoidal AC voltage (e.g., 0.1–5 Hz, 3–5 V amplitude). Measure the peak-to-peak tip displacement at each frequency. The displacement typically decreases with increasing frequency due to the finite time required for ion and water transport [27] [25].

- Data Recording: Record the tip displacement (in mm) for each combination of voltage and frequency. Plot displacement versus time for DC inputs, and displacement versus frequency for AC inputs.

Protocol for Torsional Actuation Characterization

IPMCs can be engineered for torsional motion, which is valuable for biomimetic applications like fins and wings [25].

Fabrication Modifier: Patterned Electrodes To induce torsion, fabricate an IPMC with a patterned electrode. This can be achieved by covering parts of the Nafion membrane with masking tape (e.g., polyimide) during the electroless plating process, creating isolated electrode strips [25].

Characterization:

- Setup: Clamp the IPMC with patterned electrodes at one end. Apply an AC voltage (e.g., 3–5 V, 0.1–0.3 Hz) across the specific electrode pairs designed to induce twist.

- Measurement: Use a digital camera to record the twisting motion. Analyze the video frames to measure the maximum twist angle (in degrees) of the free end [25].

- Parameter Study: Investigate the effect of electrode separation (e.g., 3 mm, 5 mm, 7 mm) on the twist angle. Research indicates that larger electrode separations can significantly enhance torsional performance by reducing lateral stiffness [25].

Performance Data and Material Selection

The performance of IPMC actuators varies based on material choices and fabrication parameters. The tables below summarize key performance metrics and material trade-offs.

Table 3: Typical IPMC Actuation Performance under Low Voltage (1-5 V)

| Performance Metric | Typical Range | Conditions / Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tip Displacement | >10 mm | For a ~20-30 mm cantilever under DC voltage. | [22] [21] |

| Blocking Force | Several mN (e.g., 5-50 mN) | Relatively low output force is a current research challenge. | [22] [28] |

| Response Time | Up to ~100 Hz | Faster response is possible with optimized materials and ionic liquids. | [24] [23] |

| Torsional Angle | Up to ~38° | For patterned electrodes (7 mm separation) at 0.1 Hz, 5 V. | [25] |

Table 4: Material Selection Guide for IPMC Components

| Component | Option | Advantages | Disadvantages / Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Membrane | Nafion (Perfluorinated) | High ionic conductivity, good chemical stability | Expensive, solvent evaporation in air |

| Polymer Membrane | Hydrocarbon-based | Lower cost, tunable structure | Can have lower ionic conductivity or stability |

| Electrode Metal | Platinum (Pt) | Excellent conductivity, stable performance | High cost |

| Electrode Metal | Gold (Au) | High conductivity, corrosion resistant | Very high cost |

| Electrode Metal | Palladium (Pd) | Good performance, used in combination with Pt | High cost |

| Mobile Cation | Li⁺ | Small hydrated radius, fast response | Can exhibit relaxation under DC |

| Mobile Cation | Na⁺ | Common and inexpensive | Performance varies |

| Mobile Cation | Ionic Liquids | Non-volatile, enables long-term air operation | Can be more viscous, slowing response |

IPMCs are promising soft smart materials that align with the demands of next-generation soft robotics and biomedical devices for compliant, low-voltage, and noiseless actuators. While challenges remain—particularly regarding their output force and long-term stability in air—ongoing research in material optimization (e.g., nanoparticle incorporation [28], alternative solvents [22]), advanced manufacturing (e.g., 3D printing [21]), and sophisticated modeling [27] [23] is steadily overcoming these limitations. The standardized application notes and protocols provided here offer a foundation for researchers to explore, characterize, and integrate these versatile artificial muscles into innovative applications, pushing the boundaries of what is possible with polymer composites in soft robotics.

Magnetic polymer composites (MPCs) represent a class of advanced functional materials that amalgamate the pliability and compliance of polymers with the responsive nature of magnetic fillers. These composites have ushered in a transformative era for soft robotics, particularly in applications demanding remote and precise actuation such as minimally invasive medical devices, drug delivery systems, and adaptive grippers [29] [30]. The fundamental operating principle of MPCs lies in their ability to undergo predictable and controllable deformation—including bending, twisting, extension, and contraction—when subjected to external magnetic fields [31]. This wireless actuation modality enables operation in confined and inaccessible spaces, including through biological tissue, making these materials exceptionally suited for biomedical applications within the broader context of soft robotics research [29] [30]. This document provides a detailed overview of the performance characteristics, fabrication protocols, and essential research tools for developing and utilizing MPCs.

Fundamental Actuation Principles and Performance Metrics

The actuation of MPCs is governed by the interaction between embedded magnetic particles and an applied magnetic field. The resulting torque and force cause alignment of the composite's magnetic easy axis with the field lines, inducing macroscopic deformation [31]. The specific nature of this deformation—bending, twisting, or contraction—is dictated by the pre-programmed spatial distribution and alignment of the magnetic particles within the polymer matrix [29] [31].

Quantitative Performance of Advanced MPCs

The table below summarizes key performance metrics for representative MPC systems, illustrating the broad range of achievable properties.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Representative Magnetic Polymer Composites

| Material System | Max. Actuation Strain (%) | Stiffness Switching Ratio (Erigid/Esoft) | Work Density (kJ m⁻³) | Key Actuation Features | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(SMA-co-EGDMA)/NdFeB | >800 | 2.7 × 10³ | 129.5 | Reversible extension, contraction, bending, twisting | [32] |

| Alginate-based Magnetic Hydrogel | N/A | N/A | N/A | Bending, twisting, biomimetic motion | [31] |

| Magnetic Elastomer (Jellyfish Robot) | N/A | N/A | N/A | Forward propulsion, fluid manipulation | [29] |

Visualization of the Magnetic Actuation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow from composite fabrication to magnetic actuation and its resulting applications.

Figure 1: MPC Fabrication and Actuation Workflow

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of Anisotropic MPCs via Molding and Magnetic Field-Assisted Alignment

This protocol details the creation of MPCs with anisotropic magnetic properties, enabling complex, pre-programmed actuation modes such as bending and twisting [29] [31].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Polymer Matrix: Silicone elastomer (e.g., PDMS) or a hydrogel precursor (e.g., Alginate solution).

- Magnetic Fillers: Neodymium-Iron-Boron (NdFeB) microparticles or Iron Oxide (Fe₃O₄) nanoparticles.

- Solvents/Dispersants: (If required) Toluene for PDMS or Deionized Water for Alginate, potentially with a surfactant (e.g., 1% w/w Silane coupling agent) to improve particle dispersion [33] [30].

- Molding Materials: 3D-printed or machined mold in the desired on-field shape (the shape the composite will assume under a strong magnetic field) [31].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Mixture Preparation: Thoroughly mix the magnetic particles into the polymer precursor (e.g., two-part silicone or alginate solution) at a predetermined weight ratio (e.g., 11-13 g of NdFeB per gram of polymer [32]). Use mechanical stirring or shear mixing to achieve a homogeneous dispersion.

- Degassing: Place the mixture in a vacuum desiccator to remove entrapped air bubbles, which can create defects and weaken the final composite.

- Mold Filling: Pour or inject the degassed mixture into the pre-fabricated mold that defines the on-field shape.

- Magnetic Structuring: Place the filled mold between the poles of an electromagnet. Apply a spatially uniform, homogeneous magnetic field (e.g., 100 kA/m [31]) while the polymer is still in a liquid or low-viscosity state. The field strength and direction will dictate the formation of particle chains and the composite's magnetic easy axis.

- Curing/Gelation: Maintain the applied magnetic field throughout the polymer's curing process (thermal cure for silicones, ionic cross-linking for alginate). The particle-chain structures become permanently fixed at the gel point.

- Demolding and Post-Processing: Once fully cured, remove the composite from the mold. The material is now an anisotropic MPC, "programmed" with a magnetization profile that will cause it to deform into the mold's shape upon re-application of a sufficiently strong magnetic field [31].

Protocol 2: Actuation and Performance Characterization of MPCs

This protocol outlines methods for quantifying the actuation performance and mechanical properties of fabricated MPCs.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Fabricated MPC Sample

- Electromagnet or Permanent Magnet Setup: Capable of generating defined, uniform, or gradient magnetic fields.

- Characterization Equipment: Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer (DMA), Optical Camera for deformation tracking, and a Magnetometer (e.g., SQUID).

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Stiffness Characterization:

- Using a DMA, perform a temperature sweep on the MPC sample to determine its storage modulus (G') below and above the polymer's thermal transition temperature (e.g., melting point, Tm).

- Calculate the Stiffness Switching Ratio (SSR) as the ratio of the elastic modulus in the rigid state (Erigid, at 25°C) to that in the soft state (Esoft, at 70°C) [32].

- Actuation Strain and Shape Morphing:

- Clamp the MPC sample in a test setup with an optical camera positioned to record its profile.

- Expose the sample to a controlled magnetic field (strength and direction). For thermally activated systems, first use a remote laser to heat the composite above its Tm [32].

- Record the deformation (bending angle, axial strain, twisting angle) using the camera. Analyze the footage to quantify the maximum actuation strain and strain rate.

- Work Density and Energy Efficiency:

- Perform loading-unloading mechanical tests on the MPC at various strains (e.g., 100% to 500%).

- Calculate the energy density (u) from the area under the loading curve.

- Calculate the energy efficiency (η) as the ratio of the area under the unloading curve to the area under the loading curve [32].

- Magnetic Characterization:

Table 2: Summary of Key Fabrication Techniques for MPCs

| Fabrication Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Ideal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molding & Magnetic Alignment | Particle chains form and align in a magnetic field during curing [31]. | Simple principle, low cost, enables complex anisotropy [29]. | Bending/twisting actuators, biomimetic robots [29] [31]. |

| 3D Printing (DIW, FDM) | Layer-by-layer deposition of MPC ink or filament [34]. | High structural complexity, integrated fabrication [34] [30]. | Complex 3D architectures, custom-designed robots [34]. |

| Surface Coating | Deposition of a magnetic layer onto a polymeric substrate [34]. | Decouples mechanical and magnetic properties. | Sensors, simple bending actuators [34]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

The following table catalogues essential materials and reagents required for the fabrication and characterization of MPCs for soft robotics.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MPC Development

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| NdFeB Microparticles | Magnetically "hard" filler providing high remanent magnetization and strong actuation forces [32] [30]. | Particle size: 1-50 µm, Saturation Magnetization: >358 kA/m [32]. |

| Iron Oxide (Fe₃O₄) Nanoparticles | Biocompatible, magnetically "soft" filler, often superparamagnetic, suitable for biomedical applications [31] [30]. | Particle size: 10-100 nm, often used in hydrogels [31]. |

| PDMS (Sylgard 184) | A common, biocompatible silicone elastomer used as the polymer matrix for flexible and stretchable composites [30]. | Base:Cross-linker = 10:1, Young's Modulus: ~1-2 MPa [30]. |

| Alginate Biopolymer | A natural, biodegradable polymer for forming hydrogels; ideal for creating biocompatible/transient devices [31] [30]. | 2-4% (w/v) in aqueous solution, cross-linked with Ca²⁺ ions [31]. |

| Octadecyltrichlorosilane (ODTS) | A silane coupling agent used to functionalize magnetic particles, improving dispersion and interfacial bonding within hydrophobic polymers [32]. | Grafted onto NdFeB particles to form physical entanglements with polymer chains [32]. |

| Programmable Electromagnet | Provides a controllable magnetic field for both particle alignment during fabrication and for actuation of the final composite. | Capable of generating uniform fields >100 kA/m [31]. |

Shape Memory Polymer Composites (SMPCs) represent a advanced class of stimuli-responsive materials that have revolutionized the concept of programmable shape transformation in soft robotics and biomedical devices [35]. These materials can be deformed and fixed into a temporary shape and subsequently recover their original, permanent shape upon exposure to an external stimulus such as heat, light, electricity, or magnetic fields [36] [37]. This unique functionality stems from their molecular architecture, which combines a cross-linked network determining the permanent shape with molecular switches that temporarily fix the deformed shape [38].

The integration of SMPCs into soft robotic systems addresses a critical need for flexible, adaptable machines that can operate safely in unstructured environments, particularly for biomedical applications where traditional rigid robots face limitations [35]. Unlike shape memory alloys, SMPCs offer significant advantages including lightweight properties, high deformability, and tunable transition temperatures compatible with biological systems [37]. Recent advances in additive manufacturing have further expanded their potential through 4D printing, where 3D-printed structures can transform their shape over time in response to specific stimuli [39] [40].

This application note details the fundamental principles, material formulations, experimental protocols, and performance metrics of SMPCs, with particular emphasis on their implementation within soft robotics research and drug development applications. We provide structured quantitative data and detailed methodologies to enable researchers to effectively leverage these programmable materials in their investigative work.

Material Compositions and Functional Mechanisms

Fundamental SMPC Formulations

SMPCs can be engineered using various polymer matrices and reinforcement strategies to achieve desired thermomechanical properties and activation mechanisms. The composition directly influences key parameters including glass transition temperature (Tg), recovery stress, and actuation speed.

Table 1: Common SMPC Material Compositions and Properties

| Polymer Matrix | Reinforcement/Filler | Stimulus | Key Properties | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epoxy resin [37] | Carbon fibers (0/90° weave) | Thermal | Recovery stress: 16-47 MPa, Rr: >90% | Aerospace deployables |

| PLA/TPU (70:30) [38] | Thermochromic microcapsules, SMA fibers | Electro-thermal | Simultaneous shape memory and color change | Biomedical sensors, camouflage |

| PLA [40] | Graphite flakes (5-15 wt%) | Microwave (2.45 GHz) | Rapid heating (seconds to Tg), tunable conductivity | Rapid actuators |

| Cholesteric polymer [36] | Poly(benzyl acrylate) | Thermal (10-54°C) | Large color response (~155 nm) | Optical sensors, indicators |

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table summarizes essential materials and their functions for developing SMPC-based systems:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for SMPC Development

| Material Category | Specific Examples | Function in SMPC System |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Matrices | Epoxy resin (3M Scotchkote 206N) [37], Poly(lactic acid) (PLA) [40], Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU) [38] | Provides shape memory capability, determines transition temperature, and offers mechanical integrity |

| Reinforcements | Carbon fibers (woven/unidirectional) [37], Shape Memory Alloy (SMA) fibers [38] | Enhances mechanical properties, enables electrical conductivity for joule heating, provides recovery stress |

| Functional Additives | Graphite flakes (5-15 wt%) [40], Carbon nanotubes [37], Thermochromic microcapsules (TMC) [38] | Enables responsive heating (microwave, joule), introduces multifunctionality (color change), improves thermal conductivity |

| Photoinitiators | Irgacure 651 [36] | Initiates photopolymerization for UV-curable SMP systems |

| Solvents | Tetrahydrofuran (THF) [36], Dichloromethane (DCM) [40] | Processing and fabrication of polymer composites |

Experimental Protocols and Characterization

Fabrication of SMPC Laminates for Actuation

Protocol Objective: To manufacture carbon fiber-reinforced SMPC laminates with an integrated shape memory interlayer for deployable structures [37].

Materials and Equipment:

- Carbon fiber prepreg (0/90° weave, e.g., Cycom 132 977-2)

- Uncured epoxy resin powder (e.g., 3M Scotchkote 206N, density: 1.44 g/cm³)

- Aluminum mold with rectangular cavity (30 × 100 mm²)

- Compression molding apparatus with hot plates

- Universal material testing machine (e.g., MTS Insight 5)

- Type K thermocouple for temperature monitoring

Procedure:

- Prepreg Preparation: Cut carbon fiber prepreg plies to nominal dimensions of 30 × 100 mm².

- Interlayer Deposition: Manually deposit uncured epoxy resin powder onto prepreg surface. For a 100 μm interlayer, use 0.43 g powder; for 200 μm, use 0.86 g. Ensure uniform distribution without gaps.

- Stacking Sequence: Assemble the desired number of plies (typically 2-8 plies) using hand lamination technique.

- Compression Molding: Place stacked laminate in aluminum mold with polyethylene release film. Cure at 200°C and 70 kPa pressure for 1 hour.

- Consolidation: Cool molded laminate and extract from mold. The interlayer thickness will be reduced due to edge bleeding during processing.

- Thermo-mechanical Programming: Program the permanent shape by heating the composite above its glass transition temperature (Tg = 120°C [37]), deforming to the desired configuration, and cooling while maintaining deformation.

Quality Control:

- Verify final laminate dimensions and check for voids or delamination.

- Conduct three-point bending tests at 1 mm/min with 80 mm load span to determine stiffness and elastic modulus.

4D Printing of Multi-Responsive SMPCs

Protocol Objective: To fabricate 3D-printed SMPC structures exhibiting simultaneous shape memory and color-changing capabilities via fused deposition modeling (FDM) [38].

Materials and Equipment:

- PLA/TPU blend (70:30 mass ratio) filament

- Thermochromic microcapsules (TMC, 6 wt% of polymer matrix)

- Shape Memory Alloy (SMA) fibers

- Filament extruder (e.g., Noztek)

- FDM 3D printer (e.g., MakerBot Replicator 2X)

- Ultrasonic cleaner (e.g., KODO NXP-1002)

Procedure:

- Composite Filament Preparation:

- Dissolve PLA/TPU blend in dichloromethane (DCM) and mix for 90 minutes.

- Add TMC (6 wt%) to the polymer solution and sonicate for 10 minutes to ensure uniform dispersion.

- Evaporate solvent in fume hood for 8 hours until complete solidification.

- Chop solidified composite into small pieces and extrude into uniform filament (diameter: ~1.75 mm).

Dual-Material 3D Printing:

- Design model incorporating both SMPC composite and pure polymer regions.

- Utilize dual-extrusion FDM printing to create structures with SMPC and SMA fibers.

- Set nozzle temperature appropriate for PLA/TPU composite (typically 190-210°C).

- Program SMA fibers during printing process to enable conductive pathways.

Actuation and Characterization:

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 3: Shape Memory Performance Metrics of Various SMPC Formulations

| SMPC Architecture | Shape Fixity (Rf) | Shape Recovery (Rr) | Recovery Time | Actuation Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 μm/6-ply laminate [37] | 94.8% | 95.7% | - | Thermal (120°C) |

| 200 μm/2-ply with microheater [37] | - | 86.2° recovery in 90s | 90 s | Electrical (24 V) |

| PLA/Graphite (15 wt%) [40] | - | Full recovery | <15 s | Microwave (360 W) |

| Photonic semi-IPN film [36] | - | Multiple stage recovery | - | Thermal (10-54°C) |

Application Workflows in Soft Robotics

Soft Actuator Programming and Activation

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for developing SMPC-based soft actuators, from material preparation to functional deployment:

Advanced Multi-Material Actuation System

Complex soft robotic systems often require selective actuation of different components, achieved through multi-material SMPC designs:

Application Scenarios in Biomedical Research

Drug Delivery System Actuation

SMPC-based devices offer significant potential for controlled drug delivery applications. Temperature-responsive SMPCs can be programmed to change shape at specific physiological temperatures, enabling targeted release of therapeutic agents. The integration of conductive fillers allows for precise external triggering via electromagnetic fields, providing temporal control over drug release profiles [35]. Such systems are particularly valuable for implanted devices that require minimally invasive deployment followed on-demand activation.

Laboratory Automation and Sample Handling

In drug development laboratories, SMPC grippers and manipulators can enhance automation systems for delicate sample handling. These soft actuators can be designed to apply gentle, conformal forces that prevent damage to fragile biological specimens. The ability to undergo large deformations allows for adaptive grasping of irregularly shaped containers and tissues, improving processing efficiency while reducing contamination risks [35].

Technical Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite significant advances, several challenges remain in the widespread implementation of SMPCs for soft robotics and biomedical applications. Actuation speed continues to be a limitation, with many thermal SMPCs requiring tens of seconds to complete shape recovery [37]. The integration of conductive fillers such as graphite flakes (15 wt%) has demonstrated remarkable improvements, enabling recovery times of less than 15 seconds through microwave activation [40]. Fatigue resistance and long-term durability under cyclic activation represent additional hurdles, particularly for implantable medical devices that require repeated functionality.

Future development trajectories include the creation of multi-stimuli-responsive SMPCs that can be activated through different energy sources depending on environmental conditions [38]. The integration of artificial intelligence for predicting and optimizing shape recovery paths represents another promising frontier [35]. Furthermore, advances in 4D printing technologies will enable more complex architectures with spatially controlled material properties, opening new possibilities for biomimetic soft robots capable of sophisticated, programmable motions [39].

As material formulations continue to evolve and manufacturing techniques become more sophisticated, SMPCs are poised to become increasingly integral to soft robotic systems for biomedical research and drug development applications.

In the rapidly advancing field of soft robotics, polymer composites have emerged as fundamental materials for creating actuators that mimic biological muscles. These materials are pivotal for developing systems that require high compliance, adaptability, and multifunctionality for applications ranging from biomedical devices to rescue operations [41]. The performance of these soft actuators is primarily governed by four key properties: actuation strain, force, response time, and compliance. Accurately measuring and comparing these properties is essential for selecting the appropriate material system for specific research and application goals. This document provides detailed application notes and standardized experimental protocols to characterize these critical parameters, framed within the context of developing advanced polymer composites for soft robotics research.

Quantitative Properties of Key Actuator Materials

The tables below summarize the key performance metrics for major categories of soft actuator materials, providing a benchmark for comparison and selection. The data highlights the trade-offs between different material systems, such as the high strain of Dielectric Elastomers versus the high force of Conducting Polymers.

Table 1: Performance Properties of Electronic Electroactive Polymer (EAP) Actuators

| Material Class | Actuation Strain | Force | Response Time | Compliance | Driving Voltage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dielectric Elastomers | Large deformation [4] | High energy density [4] | Fast [4] | High (Low elastic modulus) [4] | High voltage range [4] |

| Liquid Crystal Elastomers (LCEs) | Reversible strain >200% [4] | --- | Seconds (for large strain) [4] | High [4] | --- |

| Piezoelectric Polymers | --- | --- | --- | High [4] | --- |

Table 2: Performance Properties of Ionic Electroactive Polymer (EAP) Actuators

| Material Class | Actuation Strain | Force | Response Time | Compliance | Driving Voltage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conducting Polymers | Up to 6% strain [4] | Up to 34 MN/m² [4] | Strain rate of 4%/s [4] | High [4] | Low voltage (< 3 V) [4] |

| Ionic Polymer-Metal Composites (IPMCs) | Large deformations [4] | --- | --- | High [4] | Low voltage range [4] |

Table 3: Performance Properties of Magnetic Polymer Composites

| Material Property | Description |

|---|---|

| Actuation Strain | Capable of massive and dynamic deformations (e.g., bending, gripping, rolling) [29]. |

| Response Time | Fast, reversible actuation enabled by external magnetic fields [29]. |

| Compliance | Soft and compliant matrix allows passive physical adaptation [29]. |

| Force | High-power density actuators [29]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Measuring Actuation Strain in Dielectric Elastomers

Principle: This protocol quantifies the planar strain of a Dielectric Elastomer Actuator (DEA) under an applied electric field. The Maxwell stress causes the film to expand in area and contract in thickness [4].

- Materials Required: Dielectric elastomer film (e.g., acrylic, silicone), compliant electrodes (e.g., carbon grease, carbon nanotube), high-voltage source, high-speed camera, optical markers.

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Cut the dielectric film to a standardized size (e.g., 50x50 mm). Apply compliant electrodes to both surfaces.

- Marker Placement: Place optical markers on the film surface for motion tracking.

- Testing Setup: Clamp the sample edges to create a fixed boundary. Position the camera perpendicular to the film surface.

- Actuation & Recording: Apply a controlled voltage ramp from 0V to the target voltage. Record the deformation at a high frame rate.

- Data Analysis: Use video analysis software to track marker displacement. Calculate the linear strain (%) in both planar directions.

Protocol for Measuring Blocked Force in Conducting Polymer Actuators

Principle: This protocol measures the maximum force (blocked force) a conducting polymer actuator can generate when its displacement is fully constrained, indicating its peak force capability [4].

- Materials Required: Conducting polymer actuator (e.g., polypyrrole, polyaniline), low-voltage source, force transducer (load cell), rigid fixture, data acquisition system.

- Procedure:

- Sample Mounting: Securely fix one end of the actuator to a rigid fixture. Connect the other end to the load cell, ensuring the actuator is in its neutral position.

- Electrical Connection: Connect the actuator to the voltage source using compliant wires.

- Constrained Actuation: Apply the operating voltage (typically 1-3 V). The load cell measures the force generated while the actuator is prevented from moving.

- Data Collection: Record the steady-state force output from the load cell. Repeat for multiple cycles to ensure consistency.

Protocol for Characterizing Response Time in Magnetic Polymer Composites

Principle: This protocol determines the time taken for a magnetic soft composite to transition from its initial state to a predefined actuated state under a pulsed magnetic field [29].

- Materials Required: Magnetic polymer composite sample, programmable electromagnetic coil, high-speed camera, timing synchronization circuit.

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Fabricate the composite (e.g., by moulding) with dispersed magnetic particles [29].

- Synchronization: Connect the electromagnetic coil driver and the high-speed camera to a trigger.

- Actuation Cycle: Subject the sample to a magnetic field pulse with a square wave profile.

- Kinetic Analysis: Record the deformation. The response time is calculated as the time between the field trigger and the moment the actuator reaches 90% of its full displacement.

Protocol for Quantifying Mechanical Compliance

Principle: This protocol uses a tensile test to measure the elastic modulus (a inverse measure of compliance) of the polymer composite.

- Materials Required: Universal testing machine, standardized dog-bone shaped samples of the composite.

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare specimens according to ASTM D638 standard.

- Tensile Test: Mount the sample in the tester and apply a uniaxial tensile strain at a constant rate.

- Stress-Strain Analysis: Record the stress-strain curve. The elastic modulus (E) is calculated from the slope of the initial linear region. A lower modulus indicates higher compliance.

Experimental Workflow and Material Composition

The following diagrams illustrate the standard workflow for developing and testing soft actuators, and the functional composition of a multifunctional hybrid actuator.

Diagram 1: Soft Actuator Research Workflow

Diagram 2: Composition of a Multifunctional Actuator Hybrid

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details key materials and their functions for developing and testing polymer composite actuators.

Table 4: Essential Materials for Soft Actuator Research

| Material/Reagent | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Dielectric Films (Acrylics, Silicones) | Primary component in Dielectric Elastomer Actuators (DEAs); properties like high dielectric constant and breakdown strength are critical for performance [4]. |

| Compliant Electrodes (Carbon Grease, CNTs) | Form conductive, stretchable surfaces on dielectric films for charge distribution without constraining deformation [4]. |

| Magnetic Particles (NdFeB, Ferrites) | Active filler in magnetic polymer composites; enables remote actuation and shape programming when embedded in a polymer matrix [29]. |

| Liquid Crystal Elastomers (LCEs) | Base material for actuators capable of large, reversible shape changes (strains >200%) in response to thermal or optical stimuli [4]. |

| Conducting Polymers (Polypyrrole, PEDOT:PSS) | Serve as active material in low-voltage ionic EAPs, providing fast actuation speeds and self-sensing capabilities [4]. |

| Shape Memory Polymers (SMPs) | Polymer matrix that can be programmed into a temporary shape and recover to a permanent shape upon external stimulus, used in moulding composites [29]. |

From Concept to Clinic: Fabrication Methods and Biomedical Applications

Advanced manufacturing techniques are foundational to the development of soft robotics, enabling the creation of complex, compliant structures that mimic biological systems. These processes allow for the precise integration of polymer composites, yielding actuators and sensors with tailored mechanical, electrical, and thermal properties. This document details the core protocols for molding, 3D printing, and shape deposition, framing them within the context of manufacturing functional soft robotic components. The focus is on the fabrication of devices that exhibit adaptive functionalities, such as actuation and sensing, using conductive polymer composites and electroactive polymers [5] [12].