Advanced Fabrication Methods for Polymer Nanocomposites: Techniques, Innovations, and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive review of contemporary fabrication techniques for polymer nanocomposites, with a specific focus on meeting the needs of researchers and drug development professionals.

Advanced Fabrication Methods for Polymer Nanocomposites: Techniques, Innovations, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of contemporary fabrication techniques for polymer nanocomposites, with a specific focus on meeting the needs of researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of nanomaterial-polymer interactions, details advanced synthesis methodologies like in situ polymerization and electrospinning, and addresses critical challenges such as nanofiller dispersion and biocompatibility. The content systematically compares the performance outcomes of different fabrication routes and highlights transformative applications in drug delivery, antimicrobial coatings, and tissue engineering. By integrating troubleshooting strategies with a forward-looking perspective, this review serves as a strategic guide for the development of next-generation, high-performance nanocomposites for clinical translation.

The Building Blocks of Polymer Nanocomposites: Nanofillers, Matrices, and Interfacial Science

Definition and Core Significance

Polymer nanocomposites (PNCs) are a class of advanced materials composed of a polymer or copolymer matrix into which nanoscale fillers (typically 1–50 nm in at least one dimension) are dispersed [1] [2]. The fundamental distinguishing factor of PNCs, compared to traditional composites, is the immense amount of interfacial area between the polymer matrix and the nanoscale fillers [1]. This extensive interface is pivotal for transferring the exceptional properties of the nanofillers—such as high strength, electrical conductivity, or thermal stability—to the overall composite, resulting in performance characteristics that often surpass those of conventional materials [1] [3].

The significance of polymer nanocomposites stems from their ability to be uniquely designed for specific applications, offering a combination of properties not found in their individual components [4]. By incorporating small amounts (a few weight percent) of nanofillers, manufacturers can dramatically enhance the polymer's mechanical properties (strength, stiffness, toughness), thermal stability, barrier properties (resistance to gas permeation), and electrical conductivity [1] [4] [3]. This has led to their widespread adoption across a diverse range of industries, from aerospace and automotive to biomedical and electronics.

Types of Nanofillers and Material Properties

Nanofillers are categorized based on their geometry and number of nanoscale dimensions. The selection of nanofiller type is critical for tailoring the properties of the resulting nanocomposite for its intended application [1].

Table 1: Classification and Properties of Common Nanofillers in Polymer Nanocomposites

| Nanofiller Type | Number of Nanoscale Dimensions | Examples | Key Property Enhancements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanoplatelets | One (1D) | Nanoclays (e.g., Montmorillonite), Graphene [1] [3] | Improved barrier properties, enhanced flame retardancy, increased stiffness [4] [3] |

| Nanofibers | Two (2D) | Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs), Electrospun Nanofibers [1] [5] | Superior tensile strength, electrical and thermal conductivity, toughness [1] [2] [3] |

| Nanoparticulates | Three (3D) | Nano-Oxides (e.g., SiO₂, TiO₂, ZnO), Metal Nanoparticles (e.g., Silver, Gold) [1] [3] | Antimicrobial properties, UV resistance, catalytic activity, enhanced thermal stability [4] [6] [3] |

Carbon-based nanomaterials, particularly Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) and graphene, are among the most prominent nanofillers due to their extraordinary combination of mechanical, electrical, and thermal properties [1] [3]. CNTs are further classified into Single-Walled (SWCNTs) and Multi-Walled (MWCNTs), with MWCNTs being more economically feasible for widespread industrial applications [1].

Key Synthesis Techniques and Methodologies

The successful fabrication of high-performance PNCs relies on achieving a homogeneous dispersion of nanofillers within the polymer matrix and ensuring strong interfacial adhesion. Agglomeration of nanoparticles due to strong van der Waals forces is a primary challenge that these synthesis methods aim to overcome [1] [3].

Protocol 3.1: Solution Blending

Principle: This technique involves dispersing the nanofillers and dissolving the polymer in a suitable solvent, followed by mixing and eventual solvent evaporation to form the composite [1].

- Dispersion: The nanofillers are added to a compatible solvent and dispersed using high-shear mixing or ultrasonication to break up agglomerates [1].

- Polymer Introduction: The polymer is dissolved in the same or a compatible solvent to form a separate solution.

- Mixing: The dispersed nanofiller solution and the polymer solution are combined and mixed thoroughly, often with continued mechanical stirring or ultrasonication.

- Solvent Removal: The mixture is cast onto a substrate and the solvent is evaporated, leaving behind a solid nanocomposite film. For complete removal, the film may be placed under vacuum. Considerations: Best for polymers soluble in common solvents. Residual solvent can affect properties, and the process may not be environmentally friendly or economical on a large scale [1].

Protocol 3.2: Melt Blending

Principle: This method involves mixing nanofillers directly with a thermoplastic polymer above its melting temperature using high-shear equipment like a twin-screw extruder [1].

- Drying: The polymer and nanofillers are dried to prevent hydrolysis or degradation during processing.

- Melt Processing: The polymer is fed into an extruder and heated until molten. Nanofillers are fed into the polymer melt via a hopper.

- Shear Mixing: The rotating screws generate high shear forces, which disperse the nanofillers throughout the polymer melt.

- Extrusion and Pelletizing: The homogenized melt is extruded through a die and cooled, then cut into pellets for subsequent shaping (e.g., injection molding). Considerations: Highly compatible with existing industrial infrastructure. Limited to thermoplastics that can withstand the processing temperatures, with potential risk of polymer degradation under high shear [1].

Protocol 3.3: In Situ Polymerization

Principle: Nanofillers are first dispersed in a low-viscosity monomer solution, and the polymerization reaction is initiated to form the polymer matrix around the dispersed fillers [1] [4].

- Monomer Preparation: The monomer and any required catalysts or initiators are prepared.

- Filler Dispersion: The nanofillers are dispersed in the monomer solution using mechanical stirring or ultrasonication.

- Polymerization: Polymerization is initiated thermally, with UV light, or by adding a catalyst, converting the monomer into a solid polymer with embedded nanofillers. Considerations: Excellent for achieving good filler dispersion, especially for insoluble or thermally unstable polymers. Adds complexity due to the chemical process involved [1].

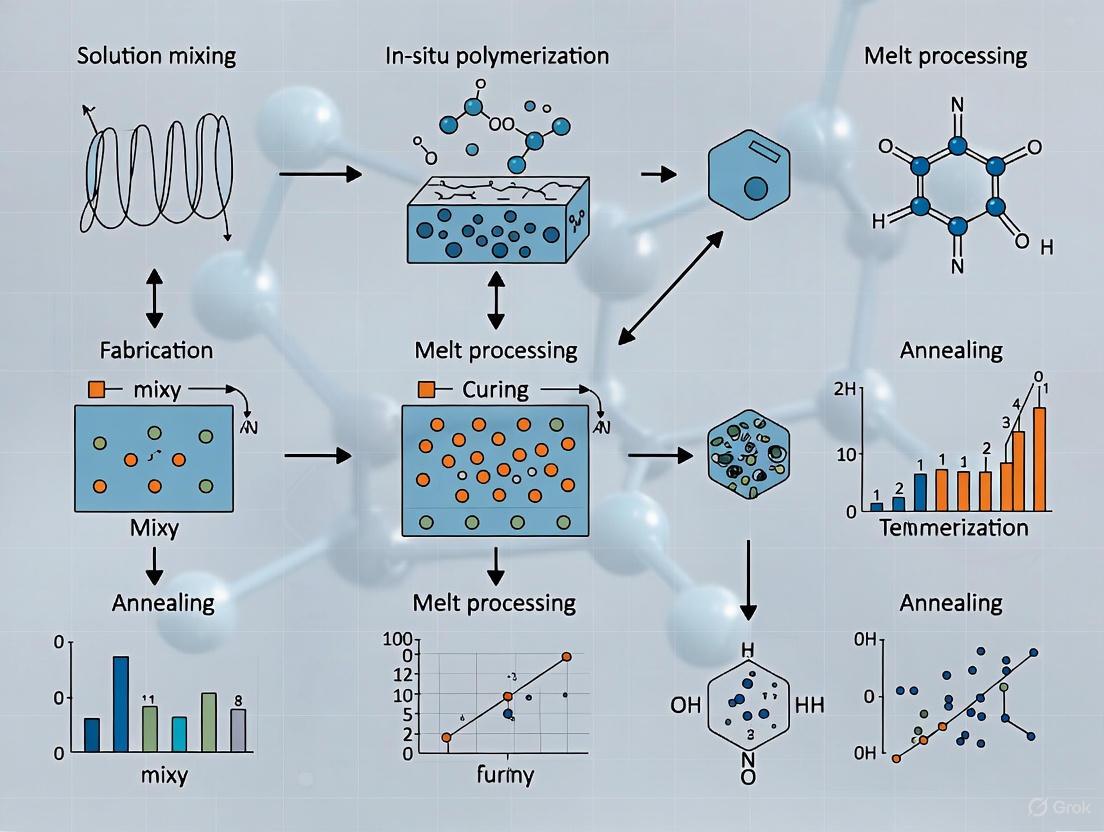

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting an appropriate synthesis technique:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Fabricating and characterizing polymer nanocomposites requires a range of specialized materials and instruments. The table below details key components essential for research in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Polymer Nanocomposite Fabrication

| Category | Item / Reagent | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Matrices | Epoxy Resin, Polyamide (Nylon), Polyethylene (PE), Polypropylene (PP), Polybutylene Succinate (PBS) [7] [5] | Serves as the continuous phase or host material; provides bulk form, processability, and determines baseline chemical resistance. |

| Nanofillers | Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNTs/MWCNTs), Nanoclays (Montmorillonite), Graphene, Nano-Oxides (SiO₂, TiO₂, ZnO), Metal Nanoparticles (Ag) [3] [5] | The reinforcing phase; imparts enhanced mechanical, thermal, electrical, or barrier properties to the composite. |

| Solvents | Tetrahydrofuran (THF), Dimethylformamide (DMF), Chloroform, Toluene | Dissolves polymer for solution processing; medium for dispersing nanofillers. |

| Functionalization Agents | Silane coupling agents, Surfactants | Chemically modifies nanofiller surface to improve compatibility and dispersion within the polymer matrix [1]. |

| Processing Aids | Plasticizers, Thermal Stabilizers | Improves processability and prevents thermal degradation during high-temperature processing like melt blending. |

| Characterization Equipment | Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM), Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM), X-ray Diffractometer (XRD), Spectroscopic Ellipsometry | Analyzes morphology, dispersion state, crystalline structure, and thermal transitions of the nanocomposite [7]. |

Applications and Market Impact

The global market for polymer nanocomposites was valued at $14.61 billion in 2024 and is projected to grow rapidly to $32.39 billion by 2029, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 17.8% [5]. This growth is driven by increasing demand across multiple high-tech industries.

Table 3: Key Application Areas for Polymer Nanocomposites

| Industry Sector | Specific Applications | Key Property Utilized |

|---|---|---|

| Automotive & Aerospace | Interior/exterior parts, engines/powertrains, suspensions, lightweight structural components [5] | Reduced weight, improved mechanical strength, enhanced thermal stability [8] [5] |

| Electronics & Electricals | Conductive films, sensors, thermal management systems, organic solar cells [4] [6] | Enhanced electrical conductivity, thermal stability, unique optical properties [6] [3] |

| Biomedical & Healthcare | Drug delivery systems, tissue engineering scaffolds, biosensors, biomedical implants [4] [2] [3] | Biocompatibility, tailored functionality, high drug-loading capacity, improved cell attachment [4] [2] |

| Packaging | Food packaging, barrier films | Improved gas/water vapor barrier properties, antimicrobial activity, mechanical strength [4] [5] |

| Energy | Solar cells, energy storage devices | Enhanced light absorption, charge transport, and storage capabilities [6] |

In the biomedical field, PNCs are particularly transformative. They act as sophisticated nanocarriers for targeted drug delivery, protecting therapeutic agents and controlling their release kinetics at specific sites in the body, thereby minimizing side effects [4] [2]. In tissue engineering, nanofibrous PNC scaffolds provide a favorable environment for cell attachment and growth, facilitating the regeneration of tissues such as bone and nerve [4] [2]. The following diagram outlines the primary biomedical applications of polymer nanocomposites:

Polymer nanocomposites (PNCs) represent a advanced class of materials where nanofillers, with at least one dimension in the 1-100 nanometer range, are incorporated into a polymer matrix to dramatically enhance its intrinsic properties [1] [9]. The foundation of this enhancement lies in the nanoscale interactions between the polymer and the filler. Unlike traditional microcomposites, which require high filler loading (20-30% by weight) for modest improvement, nanocomposites achieve superior reinforcement at significantly lower loadings (3-5% by weight) due to the exceptionally high specific surface area of the nanofillers, which can be as large as 2630 m²/g for materials like graphene [10] [11]. This high surface area enables profound interfacial interactions, leading to unprecedented improvements in mechanical strength, thermal stability, electrical conductivity, and barrier properties without compromising the polymer's processability or increasing its density [12] [9].

The dispersion state of the nanofiller is a critical determinant of the nanocomposite's final performance. Ideally, nanoparticles should be uniformly dispersed and individually coated by the polymer to achieve optimal load transfer and uniform stress distribution [11]. Three primary morphologies are possible: conventional composites (phase-separated, with properties similar to traditional composites), intercalated nanocomposites (where polymer chains insert between filler layers, creating a well-ordered multilayer structure), and exfoliated nanocomposites (where filler layers are completely and uniformly separated and dispersed in the polymer matrix) [9]. The exfoliated structure provides maximum reinforcement due to the largest possible interfacial area between the matrix and the nanoparticles [9].

Classification and Properties of Key Nanofillers

Nanofillers can be systematically classified into three broad categories based on their composition and origin: carbon-based, metal/oxide, and organic nanomaterials. The table below provides a comparative overview of the primary nanofiller types, their key properties, and common applications.

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Key Nanofillers

| Nanofiller Category | Specific Types | Key Properties | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon-Based | Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) [12] [13] | Exceptional mechanical strength (Tensile strength: 50-150 GPa, Modulus: ~1 TPa), high electrical & thermal conductivity [13] [11] | Aerospace, automotive, sensors, supercapacitors, electromagnetic absorbers [13] [14] |

| Graphene [10] [11] | High surface area (2630 m²/g), excellent electrical conductivity (6000 S/cm), superior thermal conductivity (~5000 W/m·K), gas impermeability [10] [11] | Advanced composites, energy storage, sensors, gas barrier coatings [10] [9] | |

| Fullerenes [12] | Unique cage-like structure, good electron acceptor properties | Pharmaceutical, cosmetic additives, organic photovoltaics | |

| Metal/Oxide | Metal Oxides (e.g., ZnO, TiO₂, Al₂O₃, CuO) [15] [16] | Good thermal stability, photocatalytic activity (TiO₂), UV-blocking, antimicrobial properties (ZnO, CuO) [15] | Food packaging, antimicrobial coatings, biomedical implants, catalysts, solar cells [15] [16] |

| Nanoclays (e.g., Montmorillonite) [9] [11] | Layered silicate structure, high modulus (178-265 GPa), excellent barrier properties, flame retardancy [11] | Automotive parts, food packaging, flame-retardant materials [9] [11] | |

| Metal Nanoparticles (e.g., Ag, Au, Fe₃O₄) [16] | Unique optical properties (Surface Plasmon Resonance), magnetic properties (Fe₃O₄), antimicrobial activity (Ag) | Drug delivery, biosensors, medical imaging, catalysis [16] | |

| Organic | Nanocellulose (CNC, CNF) [10] [14] | Biodegradability, biocompatibility, low density, high strength, good stiffness [10] [14] | Biomedical applications, biodegradable packaging, reinforcement in bioplastics [15] [14] |

| Dendrimers [10] [16] | Highly branched, tree-like structure, monodisperse size, tunable surface functionality | Drug delivery, gene therapy, imaging agents [10] [16] | |

| Liposomes/Micelles [16] | Hollow sphere structure, ability to encapsulate hydrophilic/hydrophobic substances | Targeted drug delivery, nanoreactors [16] |

The following diagram illustrates the hierarchical classification of these nanofillers and their structural relationships.

Experimental Protocols for Nanocomposite Fabrication and Characterization

Fabrication Methods

The successful integration of nanofillers into a polymer matrix is crucial for achieving the desired properties in the nanocomposite. The following protocols detail the most common and effective fabrication methods.

Protocol 1: Solution Blending Method

Principle: This method involves dispersing the nanofiller in a suitable solvent, mixing it with a polymer solution, and subsequently removing the solvent to form the composite [1] [17].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Polymer Dissolution: Dissolve the selected polymer (e.g., Polyvinyl alcohol, Polystyrene) in an appropriate solvent (e.g., water, toluene, chloroform) under constant magnetic stirring at 40-60°C until a homogeneous solution is obtained.

- Nanofiller Dispersion: In a separate container, disperse the predetermined weight percentage (e.g., 0.5-5 wt%) of nanofiller (e.g., CNTs, graphene oxide) in the same solvent. Subject this mixture to probe ultrasonication (e.g., 300-500 W) for 15-60 minutes in an ice bath to prevent solvent evaporation and agglomerate breakdown.

- Mixing: Combine the polymer solution and the nanofiller dispersion. Stir the mixture vigorously for 1-2 hours, followed by additional bath ultrasonication for 30 minutes to ensure homogeneous distribution.

- Solvent Removal: Cast the final mixture into a petri dish and allow the solvent to evaporate at room temperature or in a vacuum oven at elevated temperature (e.g., 50°C) for 12-24 hours to ensure complete solvent removal.

- Post-Processing: The resulting solid nanocomposite film can be further dried and cut for testing.

Advantages and Limitations:

- Advantages: Simple, effective for lab-scale production, allows for good control over filler dispersion, suitable for polymers with low thermal stability [1].

- Limitations: Use of large quantities of solvent (economic and environmental concerns), potential for residual solvent affecting properties, not easily scalable for industrial production [1].

Protocol 2: Melt Blending Method

Principle: This method involves the direct mechanical mixing of nanofillers with a molten thermoplastic polymer under high shear forces, typically using an internal mixer or a twin-screw extruder [1] [17].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Drying: Pre-dry both the polymer pellets (e.g., Polypropylene, Nylon) and the nanofiller in a vacuum oven at 80°C for at least 6 hours to remove moisture.

- Melt Processing: Feed the pre-mixed polymer and nanofiller into a twin-screw extruder or an internal mixer (e.g., Haake Rheomix). The processing temperature should be set above the glass transition temperature (Tg) for amorphous polymers or the melting temperature (Tm) for semicrystalline polymers.

- Shear Mixing: Process the mixture at a specified rotor speed (e.g., 50-100 rpm) and temperature profile for a residence time of 5-10 minutes to ensure sufficient shear stress for de-agglomeration and dispersion of the nanofiller.

- Pelletization and Molding: The extruded strand is water-cooled and pelletized. The pellets are then injection-molded or compression-molded into standard test specimens (e.g., ASTM dog-bone shapes) for characterization.

Advantages and Limitations:

- Advantages: Solvent-free, environmentally friendly, compatible with existing industrial equipment (high scalability), simplicity [1] [17].

- Limitations: Limited to processable thermoplastics, potential for polymer degradation at high shear and temperature, may be less effective for achieving exfoliation compared to solution methods [1].

Protocol 3: In Situ Polymerization Method

Principle: In this method, nanofillers are first dispersed in a low-viscosity monomer or monomer solution, followed by the polymerization of the monomer around the filler [1] [17].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Monomer-Filler Dispersion: Add the nanofiller to the liquid monomer (e.g., ε-caprolactam for Nylon 6, methyl methacrylate for PMMA). Disperse the filler using magnetic stirring and ultrasonication for 30-60 minutes.

- Polymerization Initiation: Transfer the mixture to a reaction vessel. Add the required initiator or catalyst under an inert atmosphere (e.g., Nitrogen or Argon gas).

- Polymerization: Carry out the polymerization reaction at a specified temperature and time according to the polymer system (e.g., 100°C for 12-24 hours).

- Product Recovery: After polymerization, the resulting nanocomposite solid is crushed, washed, and dried to remove any unreacted monomer or by-products.

Advantages and Limitations:

- Advantages: Enables excellent filler dispersion and strong filler-matrix interaction, suitable for insoluble or thermally unstable polymers, monomers can infiltrate filler agglomerates [1] [17].

- Limitations: Complexity of the chemical process, requires precise control over polymerization parameters, may not be universally applicable to all polymer systems [1].

Characterization Techniques

Confirming the structure, morphology, and properties of the synthesized nanocomposites is a critical step. The following workflow outlines the standard characterization pathway.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials, reagents, and equipment required for the fabrication and characterization of polymer nanocomposites, as derived from the experimental protocols.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for Nanocomposite Fabrication

| Category | Item | Specification / Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Matrices | Thermoplastics | Polypropylene (PP), Nylon 6 (PA6), Polyethylene terephthalate (PET), Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU) [14] [9] | Primary matrix; determines bulk processability and properties. |

| Thermosets | Epoxy, Phenol-formaldehyde (PF) [13] [9] | Cross-linked matrix for high-performance applications. | |

| Biopolymers | Chitosan, Poly(lactic acid) (PLA), Starch, Poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) [15] [9] | Sustainable and biocompatible matrix for green composites. | |

| Nanofillers | Carbon-Based | SWCNTs, MWCNTs, Graphene nanoplatelets, Graphene Oxide [12] [13] [11] | Provide electrical/thermal conductivity and mechanical reinforcement. |

| Metal/Oxide | ZnO nanoparticles, TiO₂ nanoparticles, CuO nanoparticles, Montmorillonite clay [15] [11] | Impart UV resistance, photocatalytic activity, antimicrobial properties, and barrier improvement. | |

| Organic | Nanocrystalline Cellulose (NCC), Dendrimers [10] [14] | Provide reinforcement in bio-nanocomposites or act as carriers for drug delivery. | |

| Solvents & Chemicals | Dispersion Solvents | Deionized Water, Toluene, Chloroform, Dimethylformamide (DMF) [1] [11] | Medium for solution blending and filler dispersion. |

| Surfactants | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS), Sodium Dodecyl Benzenesulfonate (SDBS) [11] | Stabilize nanoparticle dispersion and prevent re-agglomeration. | |

| Coupling Agents | (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES), other silanes [17] | Chemically modify filler surface to improve compatibility with polymer matrix. | |

| Equipment | Dispersion | Ultrasonic Bath, Ultrasonic Probe Homogenizer [1] [11] | Apply mechanical energy to break up nanofiller agglomerates. |

| Mixing & Processing | Twin-Screw Extruder, Internal Mixer (e.g., Haake Rheomix), Magnetic Stirrer/Hotplate [1] [17] | Melt and homogenize the polymer-nanofiller mixture. | |

| Molding | Injection Molding Machine, Compression Press | Shape the final nanocomposite into test specimens or products. | |

| Characterization | Tensile Testing Machine, TGA, DSC, SEM, TEM, XRD, FTIR [9] | Analyze morphology, structure, and properties of the final nanocomposite. |

The strategic classification of nanofillers into carbon-based, metal/oxide, and organic categories provides a structured framework for researchers to select the most appropriate material for tailoring the properties of polymer nanocomposites. The efficacy of the final material is contingent upon a deep understanding of the intrinsic properties of the nanofiller and the selection of a suitable fabrication protocol—be it solution blending, melt blending, or in situ polymerization—to overcome the perennial challenge of achieving homogeneous dispersion and strong interfacial adhesion. As this field advances, the focus is shifting towards sustainable and functional nanocomposites, particularly those utilizing biopolymers and organic nanofillers like nanocellulose for biomedical and green packaging applications [15] [10]. Furthermore, the development of hybrid nanocomposites, which combine multiple nanofillers such as polymer/fiber/CNT systems, presents a promising frontier for creating multifunctional materials with synergistic properties that meet the demanding requirements of next-generation applications in aerospace, automotive, and advanced biomedicine [13]. The ongoing research into more efficient, scalable, and eco-friendly fabrication methods will be pivotal in unlocking the full commercial potential of these advanced materials.

The selection of an appropriate polymer matrix is a foundational step in the design of polymer nanocomposites (PNCs) for advanced applications, including drug delivery and biomedical devices. The polymer matrix serves as the continuous phase that hosts the nanoscale fillers, critically determining the composite's mechanical integrity, degradation profile, biocompatibility, and overall functionality [4]. The core dichotomy in selection lies between natural polymers, prized for their innate bioactivity and compatibility, and synthetic polymers, which offer superior and tunable mechanical properties and processability [18]. A third, rapidly evolving category is that of biodegradable polymers, both natural and synthetic, which are engineered to break down into environmentally benign or metabolizable byproducts after their useful life [19] [20]. This document provides structured application notes and experimental protocols to guide researchers in selecting and working with these polymer matrices within the context of nanocomposites fabrication.

Comparative Analysis of Polymer Matrices

A systematic selection of a polymer matrix requires a clear understanding of the properties and trade-offs associated with each class. The following tables summarize the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of natural, synthetic, and biodegradable polymers.

Table 1: Comparison of Natural and Synthetic Polymer Matrices

| Aspect | Natural Polymers | Synthetic Polymers |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Extracted from biomass (e.g., plants, animals, microorganisms) [20]. | Chemically synthesized from petroleum-based or renewable monomers [20]. |

| Key Examples | Collagen, chitosan, alginate, starch, cellulose, silk fibroin [18] [20]. | Poly(lactic acid) (PLA), Poly(glycolic acid) (PGA), Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL), Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) [18] [20]. |

| Biocompatibility | Typically excellent, due to biological recognition [18]. | Variable; can be designed to be high, but may elicit inflammatory responses [18]. |

| Biodegradability | Inherently biodegradable; enzymatic degradation [20]. | Not inherent; must be engineered (e.g., aliphatic polyesters) [19] [20]. |

| Mechanical Properties | Often limited; can be weak and brittle [18]. | Broadly tunable; can achieve high strength, toughness, and elasticity [18]. |

| Processability & Reproducibility | Can be challenging; batch-to-batch variability is common [18]. | Excellent; highly reproducible with consistent properties [18]. |

| Cost | Often lower raw material cost, but purification can be expensive [21]. | Can be cost-effective at scale, though some high-performance polymers are expensive [21]. |

Table 2: Properties of Common Biodegradable Polymers for Nanocomposites

| Polymer | Origin | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Young's Modulus (GPa) | Melting Temp. (°C) | Degradation Time | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGA [20] | Synthetic | 70 - 117 | 6.1 - 7.2 | 220 - 231 | Months | Sutures, tissue scaffolds |

| PLA [20] | Synthetic | 48 - 53 | 3.1 - 3.6 | 170 - 180 | 12-24 months | Packaging, medical devices |

| PCL [18] | Synthetic | 20 - 42 | 0.3 - 0.5 | 58 - 65 | 2-3 years | Long-term implants, drug delivery |

| Thermoplastic Starch [20] | Natural | 16 - 22 | N/A | N/A | Variable | Bio-based packaging, agriculture |

| Chitosan [18] | Natural | N/A | N/A | N/A | Enzyme-dependent | Wound dressings, drug carriers |

Experimental Protocols for Nanocomposite Fabrication and Testing

Protocol: Fabrication of a Biodegradable Polymer/Nanoclay Nanocomposite via Melt Blending

Principle: This protocol describes the integration of nanoclays into a thermoplastic biodegradable polymer (e.g., PLA) using melt blending, a common and scalable industrial method. The high shear forces at elevated temperatures disperse the nanofillers within the polymer matrix [22].

Materials:

- Polymer Matrix: Polylactic acid (PLA) pellets.

- Nanofiller: Organically modified Montmorillonite (MMT) nanoclay.

- Equipment: Twin-screw extruder, injection molding machine, vacuum oven.

Procedure:

- Drying: Dry PLA pellets and nanoclay in a vacuum oven at 80°C for at least 12 hours to remove moisture.

- Pre-mixing: Manually pre-mix the dried PLA pellets with nanoclay (e.g., at 3-5 wt%) in a container to ensure initial homogeneity.

- Melt Compounding: Feed the pre-mixed material into a co-rotating twin-screw extruder. Typical processing parameters for PLA:

- Temperature Profile: 170°C (hopper) to 190°C (die).

- Screw Speed: 100-200 rpm.

- Maintain a consistent feed rate to ensure proper shear and residence time.

- Pelletizing: The extruded strand is water-cooled and pelletized to form the masterbatch of nanocomposite.

- Specimen Fabrication: Process the pellets using an injection molding machine to form standard test specimens (e.g., ASTM D638 tensile bars). The molding temperature should be slightly below the extrusion temperature to prevent degradation.

Protocol: Assessment of Polymer Nanocomposite Biodegradation

Principle: This protocol outlines a method to evaluate the biodegradation rate of a nanocomposite under controlled composting conditions, simulating an industrial composting environment [19] [20].

Materials:

- Test Material: Nanocomposite specimens (e.g., 20 mm x 20 mm x 1 mm sheets).

- Control: Cellulose (positive control), polyethylene (negative control).

- Inoculum: Mature compost from municipal solid waste, sieved to ≤ 10 mm.

- Equipment: Bioreactors or glass jars, controlled temperature chamber, analytical balance, pH meter.

Procedure:

- Preparation: Weigh the initial mass (W₀) of each test specimen. Characterize the compost inoculum for pH and dry solid content.

- Setup: Mix the solid inoculum with the test and control materials in bioreactors. The test material concentration should be less than 1% on a dry solids basis. Maintain the compost moisture content at around 50-55%.

- Incubation: Incubate the bioreactors in the dark at a constant thermophilic temperature of 58°C ± 2°C. This is a standard condition for industrial composting [19].

- Aeration & Monitoring: Aerate the compost periodically with CO₂-free air to maintain aerobic conditions. Monitor the temperature, and adjust the moisture content with deionized water as needed.

- Analysis:

- Biodegradation Rate: Measure the evolved CO₂ periodically using titration or GC analysis. The percentage of biodegradation is calculated as the ratio of the measured CO₂ from the test material to the theoretical maximum CO₂ it could produce.

- Material Analysis: At the end of the test (typically 180 days), retrieve the specimens. Carefully clean and dry them to determine the residual dry mass (Wᵣ). Calculate the percentage of mass loss: [(W₀ - Wᵣ) / W₀] x 100. Analyze the surface morphology of retrieved specimens using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to observe physical deterioration and microbial colonization.

Decision Workflow and Experimental Process Visualization

The following diagrams, generated using DOT language, illustrate the logical decision-making process for polymer selection and the experimental workflow for nanocomposite fabrication and testing.

Polymer Matrix Selection Workflow

Nanocomposite Fabrication and Testing Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Polymer Nanocomposites Research

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) [20] [21] | A versatile, bio-based, biodegradable synthetic polymer matrix. Used in packaging, biomedical scaffolds, and 3D printing. | Exists in L- and D- isomers; ratio affects crystallinity and degradation rate. Can be brittle; often blended or plasticized. |

| Chitosan [18] | A natural cationic polymer derived from chitin. Excellent for wound healing dressings and drug delivery due to its hemostatic and antimicrobial properties. | Solubility is highly dependent on pH and degree of deacetylation. Viscosity is molecular weight dependent. |

| Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) [19] [21] | A family of natural, biodegradable polyesters produced by microorganisms. Used in biocomposites for medical implants and packaging. | Properties vary widely with monomer composition. Can be expensive to produce at scale. |

| Joncyl ADR Series [21] | A commercial styrene-acrylic multi-functional epoxide oligomer used as a reactive compatibilizer and chain extender in PLA/PBAT and other blends. | Improves miscibility and interfacial adhesion in polymer blends, leading to enhanced mechanical properties and melt strength. |

| Maleic Anhydride [21] | A chemical used to graft onto polymer chains (e.g., PLA, PP) to create compatibilizers for natural fibre-reinforced composites. | The grafted maleic anhydride groups can react with hydroxyl groups on natural fibres, improving fibre-matrix bonding. |

| Montmorillonite Clay [4] [3] | A layered silicate nanoclay used as a nanofiller to improve mechanical strength, thermal stability, and barrier properties of polymer matrices. | Must be organically modified to become organophilic and achieve proper exfoliation/dispersion in most polymer matrices. |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) [4] [3] | A carbon-based nanomaterial used to enhance electrical conductivity, mechanical strength, and thermal stability of composites. | High surface area and functional groups facilitate dispersion and interaction with the polymer matrix. Can be reduced to conductive graphene. |

In polymer nanocomposites (PNCs), the interface between the nanoscale filler and the polymer matrix is not merely a boundary but a dynamic, three-dimensional region that dictates ultimate material performance [23]. The fundamental challenge in PNC design lies in overcoming inherent thermodynamic barriers to achieve uniform nanoparticle dispersion and strong interfacial adhesion [24]. When the interface is optimally engineered, it facilitates efficient stress transfer, modifies local polymer chain dynamics, and enhances barrier properties, leading to unprecedented improvements in mechanical, thermal, and functional characteristics [23]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for characterizing and manipulating interfacial interactions in polymer nanocomposites, with specific methodologies relevant to advanced materials research and development.

Key Concepts & Quantitative Data

The Critical Role of the Interfacial Region

The interfacial region in PNCs consists of polymer chains whose conformation, mobility, and density are altered by interactions with the nanoparticle surface [23]. Traditionally, polymers adsorbed onto nanoparticles exhibit slowed relaxation and form a high-density, immobilized "dead layer" that can embrittle the composite [23]. Recent research demonstrates that by engineering the architecture of the interfacial polymers—specifically by creating bound polymer loops (BLs) on nanoparticle surfaces—it is possible to design relaxation-enhanced PNCs. These materials exhibit simultaneously improved processability (reduced melt viscosity) and enhanced mechanical properties (increased strength and toughness) in the glassy state [23].

Quantifying Interfacial Effects on Composite Properties

Table 1: Experimental Data on Interfacial Engineering in Polymer Nanocomposites

| Material System | Interfacial Engineering Strategy | Key Quantitative Results | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer-Polymer Composite | Cold drawing of polymer blend to create nanofibrils; "creating instead of adding" | Tensile strength and modulus increases of 300-400%; up to tenfold improvement over older techniques [24] | [24] |

| Polystyrene/Silica PNC | Introduction of bound polystyrene loops (6 nm thick) on silica nanoparticle surfaces | Formation of a dynamic, loose particle network; maintained fluid-like, low-viscosity dynamics at high NP loading; glassy materials showed enhanced toughness and strength [23] | [23] |

| Epoxy/Magnetic NP PNC | Bulk & surface modification: Co-doping + PEG-functionalization of Fe₃O₄ NPs | Achieved "Excellent" cure state (Cure Index) at 0.1 wt.% loading; higher activation energy vs. neat epoxy [25] | [25] |

| PLA/PCL/Silica Blend | Use of nano-silica (Aerosil200) as compatibilizer | SEM-EDS showed Si concentration up to 10x nominal value at protrusions; encapsulation by PCL; increased contact angle (more hydrophobic) [26] | [26] |

| Concrete Nanocomposite Coating | Organoclay (Cloisite 30B) in acrylic-fluorinated resin at 2-6 wt.% | Enhanced barrier properties: reduced water transport, improved sulfate attack resistance; low impact on color [27] | [27] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of "Genuine" Nanofibrillar Polymer-Polymer Composites

This protocol outlines a method to bypass dispersion challenges by creating nanofibrils in situ during processing [24].

3.1.1. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Nanofibrillar Composite Fabrication

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Polymer Blend Components | A two-polymer system where the minor component can be transformed into a fibrillar morphology. |

| Melt Blending Equipment | (e.g., Twin-screw extruder) For initial homogenization of the polymer blend. |

| Cold Drawing Apparatus | Equipment to uniaxially stretch the solid blend below the melting point of the minor component. |

| Selective Solvent | A chemical that selectively dissolves the matrix polymer to isolate nanofibrils for characterization. |

3.1.2. Methodology

- Melt Blending: Process the selected polymer components under controlled temperature and shear rate conditions to form an initial blend with a dispersed phase of the minor component [24].

- Cold Drawing: Subject the solid blend to uniaxial stretching at a temperature below the melting point of the minor component but above the glass transition temperature of both polymers. This process deforms the dispersed phase into uniformly dispersed nanofibrils [24].

- Formation of Composite:

- Path A: Nanofibrillar Polymer-Polymer Composite: The cold-drawn material, containing nanofibrils of one polymer within the matrix of the other, is the final composite product [24].

- Path B: Nanofibrillar Single Polymer Composite: The matrix polymer is selectively extracted from the cold-drawn blend, leaving behind neat nanofibrils. These nanofibrils are then processed (e.g., via compression molding) to form a composite where the fibrils reinforce a matrix of the same polymer [24].

3.1.3. Workflow Visualization

Protocol: Designing Relaxation-Enhanced PNCs with Bound Polymer Loops

This protocol details the molecular design of nanoparticle interfaces to enhance polymer dynamics and composite performance [23].

3.2.1. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Relaxation-Enhanced PNCs

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Silica Nanoparticles (SiOx) | Model filler (e.g., 65 ± 10 nm diameter). |

| Statistical Copolymer | Poly(styrene-ran-4-hydroxystyrene) [P(S-ran-HS)] of varying HS mole fractions (f_HS). |

| Matrix Polymer | e.g., Polystyrene (PS), M_w = 370 kg mol⁻¹. |

| Solvents | Methyl ethyl ketone (MEK), Toluene, Chloroform. |

| Annealing Oven | For thermal treatment under vacuum. |

3.2.2. Methodology

Preparation of Loop-Covered Nanoparticles:

- Disperse silica nanoparticles in a solution of P(S-ran-HS) in methyl ethyl ketone.

- Cast and dry the composite dispersion.

- Anneal the resulting solid composite at

T_g + 50 °C(e.g., 150 °C for PS) for 24 hours under vacuum. This promotes the adsorption of the 4-hydroxystyrene (HS) segments onto the nanoparticle surface via H-bonding with surface silanol groups, creating bound loops (BLs) of the polystyrene segments [23]. - Remove non-attached polymer chains by solvent leaching with chloroform to obtain the final BL–SiOx nanoparticles [23].

Characterization of Bound Loops:

- Use Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) to visualize and measure the thickness of the bound loop layer (hBL). The thickness decreases with increasing HS mole fraction (fHS) [23].

- Perform Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) to quantify the grafting density of the polymer loops.

- Employ Solid-state Proton NMR (¹H-NMR) on the final composite melt to confirm enhanced molecular mobility of the bound loops compared to densely adsorbed layers [23].

Fabrication and Testing of PNCs:

- Incorporate the BL–SiOx nanoparticles into the PS matrix via solution casting.

- Perform rheological measurements on the molten PNCs to demonstrate reduced viscosity and enhanced flowability.

- Conduct mechanical tests on the glassy PNCs to confirm enhanced toughness and strength [23].

3.2.3. Workflow Visualization

Characterization Techniques for Interfacial Analysis

A multi-technique approach is essential to fully characterize the interface in PNCs.

- Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS): Provides quantitative analysis of filler distribution and location within a polymer blend. EDS mapping can reveal component affinity, such as the encapsulation of nano-silica by PCL in a PLA matrix [26].

- Solid-state Proton NMR (¹H-NMR): Directly probes the molecular mobility of polymers at the interface in the composite melt, differentiating the dynamics of bound loops from immobilized adsorbed layers [23].

- X-ray Reflectivity (XRR): Measures the density profile of interfacial polymer layers, confirming the presence or absence of a high-density "dead layer" [23].

- Rheology: The temperature-dependent shifting factors (a_T) from rheological measurements are sensitive to the constrained dynamics of interfacial polymers and are a key indicator of the success of relaxation-enhancement strategies [23].

- Water Contact Angle Measurements: Used to determine changes in surface free energy and hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity induced by the addition of nanofillers (e.g., increased hydrophobicity with nano-silica) [26].

The performance of polymer nanocomposites is profoundly governed by the properties of the polymer-filler interface. Strategic interfacial engineering moves beyond simple mixing to create advanced materials with tailored properties. The protocols outlined herein—ranging from the fabrication of genuine nanocomposites via cold drawing to the molecular design of relaxation-enhanced interfaces with bound polymer loops—provide a robust toolkit for researchers. The critical insights are that optimizing the nanostructure of the interface can break traditional trade-offs, leading to materials that are both easier to process and mechanically superior [24] [23]. Success in this field relies on the rigorous application of the quantitative characterization techniques described to validate interfacial design and its direct link to macroscopic performance.

Polymer nanocomposites represent a advanced class of materials formed by dispersing nanoscale fillers into polymer matrices, resulting in synergistic property enhancements far exceeding conventional composite performance. These materials leverage the unique effects emerging at the nanoscale to overcome inherent limitations of polymers while introducing new functionalities. Within the broader thesis on polymer nanocomposites fabrication methods, this application note systematically examines the fundamental mechanisms governing the enhancement of electrical, mechanical, and thermal properties. We provide researchers with structured quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols, and visual workflows to facilitate the rational design and fabrication of advanced polymer nanocomposites for specialized applications across electronics, aerospace, and biomedical fields.

Electrical Property Enhancement

Percolation and Conductive Network Formation

The electrical property enhancement in conductive polymer nanocomposites primarily follows a percolation phenomenon, where a continuous conductive network forms throughout the insulating polymer matrix at a critical filler concentration known as the percolation threshold [28]. Below this threshold, the composite remains insulating; above it, electrical conductivity increases dramatically by several orders of magnitude.

Carbon-based nanofillers, particularly carbon black (CB), carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and graphene nanoplatelets (GnP), excel as conductive fillers due to their high intrinsic conductivity, stability against oxidation, and ability to form interconnected networks at low loadings [28] [29]. The nanoscale dimensions and high aspect ratio of these fillers enable electron transport through tunneling effects between adjacent particles, significantly reducing the percolation threshold compared to conventional micron-sized fillers.

Table 1: Electrical Property Enhancement in Polymer Nanocomposites

| Nanocomposite System | Filler Content | Electrical Conductivity | Enhancement Factor | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA/CNT [30] | 3 wt% | - | 11,400% (at 100 kHz) | Formation of conductive percolating network |

| GnP/LCP [29] | 5 wt% | 0.05 S/m | - | Homogeneous dispersion & platelet alignment |

| CB/Polysiloxane [28] | 1 wt% | - | - | Pulsed electric field-induced chain formation |

External Field-Assisted Alignment

A significant advancement in controlling percolation structures involves applying external fields during processing. Traditional DC electric fields face limitations due to dielectric breakdown at high voltages [28]. The innovative use of nanosecond pulsed electric fields allows the application of substantially higher field strengths (up to 7500 V/mm in one study) without causing material breakdown, enabling precise control over the formation of linear CB percolation networks [28].

Diagram 1: This workflow illustrates the formation of conductive percolation networks in a polymer nanocomposite under a nanosecond pulsed electric field.

Experimental Protocol: Nanosecond Pulsed Electric Field Alignment

Objective: To induce controlled percolation structures of carbon black in a polysiloxane matrix using a nanosecond pulsed electric field.

Materials:

- Conductive Filler: Carbon Black (CB), average diameter 50 nm, resistivity 100 Ω·m

- Polymer Matrix: Polysiloxane prepolymer (e.g., Part A: low viscosity ~0.1-0.2 Pa·s; Part B: high viscosity ~0.8-1.0 Pa·s)

- Solvent: Toluene for initial dispersion

Equipment:

- Nanosecond pulsed power generator (e.g., semiconductor switching devices like MOSFETs)

- Custom parallel-plate electrode cell (copper electrodes)

- Vacuum oven for solvent removal and curing

- Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) for characterization

- Impedance analyzer for electrical conductivity measurement

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve the polysiloxane prepolymer Part A in toluene using a magnetic stirrer. Add 1 wt% CB relative to the total polymer weight and disperse using high-shear mixing (e.g., 2000 rpm for 10 minutes) followed by bath sonication for 30 minutes.

- Solvent Evaporation: Remove toluene by heating the mixture at 60°C with continuous stirring until a viscous, solvent-free suspension is obtained.

- Crosslinker Addition: Mix the CB/Part A suspension with polysiloxane Part B (crosslinker) in a 1:1 weight ratio. Degas the mixture under vacuum to remove air bubbles.

- Electric Field Application: Pour the mixture into the parallel-plate electrode cell. Apply the nanosecond pulsed electric field with the following parameters:

- Field strength: 1875 - 7500 V/mm

- Pulse width: 200 ns

- Pulse repetition frequency: 100 Hz

- Application time: Maintain field during crosslinking (typically 1-2 hours at room temperature)

- Curing: Allow the composite to fully crosslink under the applied field.

- Characterization: Analyze the resulting percolation structure using SEM and measure electrical conductivity via a four-point probe method or impedance analyzer.

Key Parameters:

- The viscosity of the polymer matrix must be optimized to allow filler alignment while preventing sedimentation.

- Field strength must remain below the dielectric breakdown threshold of the composite.

Mechanical Property Enhancement

Reinforcement Mechanisms

The incorporation of nanoscale fillers such as graphene, CNTs, and ceramic nanoparticles enhances mechanical properties through several mechanisms:

- Stress Transfer Efficiency: The high surface-area-to-volume ratio of nanofillers creates an extensive polymer-filler interface, enabling efficient stress transfer from the polymer matrix to the stiffer reinforcement phase [31]. For instance, functionalized graphene/polymer nanocomposites have demonstrated 57% and 70% enhancements in Young's modulus and tensile strength, respectively [31].

- Crack Deflection and Barrier Effects: Well-dispersed nanoparticles act as physical obstacles to propagating cracks, forcing them to deviate from their path and thereby increasing the fracture energy [32].

- Constrained Polymer Dynamics: Nanoparticles restrict the mobility of surrounding polymer chains, particularly in the interfacial region, leading to increased modulus [32].

Table 2: Mechanical Property Enhancement in Polymer Nanocomposites

| Nanocomposite System | Filler Content | Tensile Strength | Young's Modulus | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA/CNT [30] | 3 wt% | +28% | - | Enhanced stress transfer |

| Graphene/Epoxy [31] | 0.45 wt% | +31.3% | - | Homogeneous dispersion & interfacial adhesion |

| Graphene/PMMA [31] | - | - | +30% vs. CNT/PMMA | High surface area & 2D geometry |

| GnP/LCP [29] | 5 wt% | +21% | +32% | Filler alignment & strong interfacial interaction |

The Critical Role of Dispersion and Novel Fabrication Routes

Achieving homogeneous nanofiller dispersion is paramount, as agglomeration creates stress concentration points that compromise mechanical performance [31]. Genuine nanocomposites represent a paradigm shift by bypassing traditional dispersion challenges. This approach involves creating nanoscale reinforcement in situ during processing (e.g., by cold-drawing polymer blends to form nanofibrils) rather than blending pre-formed nanofillers. This method can potentially increase tensile strength and modulus by 300-400% compared to conventional techniques [24].

Diagram 2: This diagram outlines the primary mechanisms and critical factors responsible for mechanical property enhancement in polymer nanocomposites.

Experimental Protocol: Solution Casting for Graphene Nanocomposites

Objective: To fabricate exfoliated graphene nanoplatelet (GnP)/liquid crystalline polymer (LCP) nanocomposite films with enhanced mechanical properties via solution casting.

Materials:

- Matrix: Liquid crystalline polymer (e.g., Parmax, poly(benzoyl-1,4-phenylene)-co-(1,3-phenylene))

- Filler: Exfoliated graphite nanoplatelets (GnP-15, ~10-15 μm diameter)

- Solvent: Chloroform (suitable for the polymer and filler)

Equipment:

- Fume hood

- Ultrasonic bath and probe sonicator

- Vacuum oven

- Teflon-coated glass plates

- Universal testing machine (for tensile testing)

- Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (FESEM)

Procedure:

- Polymer Solution Preparation: Dissolve LCP pellets in chloroform (e.g., 2% w/v) using mechanical stirring at room temperature until a clear, homogeneous solution is obtained.

- Filler Dispersion: Separately, disperse the desired weight percentage (e.g., 1-5 wt%) of GnP in chloroform using a combination of magnetic stirring and probe sonication (e.g., 200-300 W, 15-20 minutes in an ice bath to prevent overheating).

- Solution Mixing: Combine the GnP dispersion with the LCP solution. Stir the mixture vigorously for 1-2 hours, followed by bath sonication for 30-60 minutes to ensure homogeneous dispersion.

- Film Casting: Pour the final mixture onto a clean, level Teflon-coated glass plate. Cover the plate loosely with an inverted glass funnel to control the solvent evaporation rate.

- Solvent Evaporation: Allow the solvent to evaporate slowly at room temperature for 12-24 hours, followed by further drying in a vacuum oven at 50-60°C for 6-12 hours to remove residual solvent.

- Post-Processing (Optional - Alignment): For enhanced alignment, the dried film can be subjected to a mechanical buffing process using a soft cloth under light pressure to induce shear, aligning the LCP chains and GnP platelets.

- Characterization: Perform tensile tests according to ASTM D638. Examine the fracture surface and filler dispersion using FESEM.

Key Parameters:

- Solvent choice is critical and must adequately wet both the polymer and filler.

- Controlled, slow solvent evaporation helps prevent filler agglomeration and film defects.

- The highly aromatic structure of LCPs promotes strong π-π interactions with the graphene basal plane, enhancing interfacial adhesion [29].

Thermal Property Enhancement

Thermal Conductivity Mechanisms

Enhancing thermal conductivity in typically insulating polymers relies on establishing continuous pathways for efficient phonon transport. The key strategies include:

- Formation of Thermal Percolation Networks: Similar to electrical conductivity, a interconnected network of high-thermal-conductivity fillers (e.g., graphene, BN, CNTs) provides a low-resistance path for heat flow [33].

- Reduction of Interfacial Thermal Resistance: The high surface area of nanofillers, if coupled with good interfacial adhesion, minimizes Kapitza resistance (phonon scattering at interfaces) [33].

- Alignment of Anisotropic Fillers: Orienting high-aspect-ratio fillers (e.g., CNTs, graphene) in the through-plane or in-plane direction can lead to directional thermal management, which is critical for applications like electronics cooling [33].

Table 3: Thermal Property Enhancement in Polymer Nanocomposites

| Nanocomposite System | Filler Content | Thermal Conductivity | Enhancement | Application Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA/CNT [30] | 3 wt% | - | +15% | Thermal management in 3D printed parts |

| BN/Polysiloxane [28] | - | - | - | Thermally conductive electrical insulator |

| Polymer Nanocomposites [33] | Low loadings | Isotropic & Anisotropic | Significant | Battery thermal management, TIMs |

Application-Oriented Thermal Management

The enhancement of thermal conductivity is not merely a numerical improvement but is driven by application demands. Key application areas highlighted in research include wearable electronics, thermal interface materials (TIMs), battery thermal management, dielectric capacitors, and solar thermal energy storage [33]. For instance, in electronic devices, polymer nanocomposites can dissipate heat efficiently, preventing performance degradation and failure.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Polymer Nanocomposites Research

| Material Category | Specific Examples | Key Function/Property | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Nanofillers | Carbon Black (CB) [28] | Low-cost, forms conductive networks | Requires high loading (~15-20 wt%) for percolation in composites. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) [30] | High aspect ratio, excellent electrical & thermal conductivity | Tendency to agglomerate; requires dispersion strategies. | |

| Graphene Nanoplatelets (GnP) [29] | 2D structure, high modulus (~1 TPa), high conductivity | Large surface area promotes strong interfacial interaction. | |

| Polymer Matrices | Polysiloxane [28] | Insulating, flexible, crosslinkable | Suitable for electric field-assisted alignment studies. |

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) [30] | Biodegradable, thermoplastic | Common matrix for fused deposition modeling (FDM) 3D printing. | |

| Liquid Crystalline Polymer (LCP) [29] | Inherently high strength and stiffness, can be aligned | Aromatic structure promotes π-π interaction with graphene. | |

| Specialty Additives | Boron Nitride (BN) [28] | Thermally conductive but electrically insulating | Ideal for thermal management where electrical insulation is critical. |

| Silica Nanoparticles [7] | Improves piezoelectric-elastic response | Used as secondary filler in multifunctional composites. |

This application note has detailed the principal mechanisms and methodologies for enhancing the electrical, mechanical, and thermal properties of polymer nanocomposites. The key to success lies in the strategic selection of nanofillers, the implementation of advanced processing techniques—such as external field alignment and solution casting that ensure optimal dispersion and distribution—and the thoughtful design of the polymer-filler interface. The provided protocols, data, and visual guides serve as a foundation for researchers to develop next-generation polymer nanocomposites with tailored multifunctional properties, pushing the boundaries of their application in advanced technological fields. Future research directions should continue to focus on overcoming dispersion challenges, precisely controlling nanofiller orientation in three dimensions, and achieving the synergistic enhancement of multiple properties simultaneously.

Synthesis Techniques and Transformative Biomedical Applications of Polymer Nanocomposites

Polymer nanocomposites (PNCs) represent a advanced class of materials formed by dispersing nanoscale fillers within a polymer matrix, leading to significant enhancements in mechanical, thermal, electrical, and barrier properties compared to conventional polymers or microcomposites [4]. The fabrication methodology critically determines the dispersion state of nanoparticles and the resulting material performance. Achieving optimal nanoparticle dispersion remains a fundamental challenge due to thermodynamic drivers for agglomeration, which can cause conventional blending to yield microcomposite-like behavior rather than true nanocomposite performance [24] [34]. This application note details three core fabrication methodologies—in-situ polymerization, solution blending, and melt compounding—within the context of advanced materials research, providing structured protocols and analytical frameworks for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in nanocomposite development.

Comparative Analysis of Fabrication Methods

Table 1: Comparative analysis of core fabrication methodologies for polymer nanocomposites

| Parameter | In-Situ Polymerization | Solution Blending | Melt Compounding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Nanoparticles dispersed in monomer followed by polymerization [35] [36] | Nanoparticles and polymer dissolved/dispersed in solvent followed by solvent removal [36] | Nanoparticles mixed with polymer melt using high-shear equipment [37] [36] |

| Dispersion Quality | Generally good; particles nucleate on active polymer sites [36] | Good with optimal solvent selection [36] | Variable; dependent on shear forces and compatibility [38] [37] |

| Key Advantages | Strong nanoparticle-polymer adhesion [36]; applicable to complex shapes [35] | Simple process [36]; good for laboratory-scale research [39] | Solvent-free [36]; industrially scalable [37]; compatible with standard polymer processing |

| Key Limitations | Viscosity increase during process [36]; potential polymerization interference | Solvent toxicity and removal challenges [36]; environmental concerns | High-temperature exposure risk [36]; potential nanoparticle degradation/agglomeration |

| Industrial Scalability | Moderate | Moderate (solvent management challenges) | High |

| Energy Consumption | Moderate | High (due to solvent removal) | Moderate to High |

| Common Applications | Conductive composites [40]; antimicrobial textiles [36]; biomedical devices [4] | Membrane technology [36]; sensor materials; specialty coatings | Automotive components [4] [40]; packaging materials [4]; structural composites |

Table 2: Property enhancement ranges achieved through different methodologies

| Property Enhancement | In-Situ Polymerization | Solution Blending | Melt Compounding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength Increase | Up to 300-400% with optimal systems [24] | 50-200% depending on filler dispersion [39] | 30-150% dependent on compounding parameters [37] |

| Electrical Conductivity | Can achieve conductive networks at low percolation [40] | Good for creating conductive pathways [40] | Conductive with sufficient shear and dispersion [40] |

| Thermal Stability | Significant improvement [4] | Moderate to significant improvement [39] | Moderate improvement [4] |

| Barrier Properties | Good enhancement reported [4] | Excellent enhancement possible [4] | Good enhancement for packaging [4] |

Methodological Deep Dive

In-Situ Polymerization

In-situ polymerization involves dispersing nanoparticles within a monomer or monomer solution followed by polymerization, enabling the growth of polymer chains in the presence of nanofillers. This method often results in excellent filler dispersion and strong polymer-filler interfacial adhesion because nanoparticles can nucleate and grow on active sites of the macromolecular chains [36]. This approach is particularly valuable for creating nanocomposites with metals (silver, gold), carbon-based nanomaterials, and other functional fillers for advanced applications.

Experimental Protocol: In-Situ Polymerization of Nylon 6/MWCNT Nanocomposites

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs): Provide reinforcement and electrical conductivity [40].

- ε-Caprolactam Monomer: Precursor for nylon 6 polymerization [36].

- Polymerization Initiator/Catalyst: (e.g., anionic catalyst for ring-opening polymerization) - Facilitates the polymerization reaction [36].

- Compatibilizer/Surfactant: (e.g., polyvinylpyrrolidone - PVP) - Aids in nanotube dispersion and prevents agglomeration [36].

Equipment: Ultrasonic bath or probe sonicator, three-neck reaction flask equipped with mechanical stirrer, nitrogen purge system, temperature-controlled oil bath, vacuum oven.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Nanofiller Pre-dispersion: Suspend MWCNTs (e.g., 1-5 wt%) in the liquid ε-caprolactam monomer. Subject the mixture to high-intensity probe sonication for 30-60 minutes under a nitrogen atmosphere to achieve a homogeneous dispersion.

- Reactor Setup: Transfer the dispersion to a clean, dry three-neck flask equipped with a mechanical stirrer and nitrogen inlet.

- In-Situ Polymerization: Heat the mixture to the polymerization temperature (e.g., ~250°C for anionic polymerization of nylon 6) with continuous stirring. Add the catalyst system to initiate the ring-opening polymerization of ε-caprolactam. Maintain reaction conditions for 2-4 hours.

- Product Recovery: After completion, allow the reaction mass to cool. Crush the resulting solid and purify by washing with appropriate solvents to remove residual monomer and catalyst.

- Post-Processing: Dry the purified nanocomposite in a vacuum oven at 80°C for 24 hours. The resulting material can be processed via melt extrusion for pelletization or direct molding [36] [40].

Solution Blending

Solution blending relies on dispersing nanoparticles and dissolving the polymer matrix in a suitable solvent, followed by mixing and subsequent solvent removal to form the nanocomposite. This method is particularly effective for achieving good nanoparticle dispersion with minimal agglomeration, making it ideal for laboratory-scale research and applications requiring high optical clarity or specific interfacial properties.

Experimental Protocol: Solution Blending for PVDF-HFP/Clay Nanocomposites

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) (PVDF-HFP) Matrix: Provides piezoelectric properties and flexibility [36].

- Organically Modified Nanoclays (e.g., Montmorillonite): Enhance mechanical strength and dielectric properties [36].

- Solvent: N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) - Effectively dissolves PVDF-HFP and disperses nanoclays [36].

- Non-Solvent: Deionized Water or Methanol - Acts as an anti-solvent for coagulation [36].

Equipment: Magnetic stirrer/hotplate, ultrasonic bath or sonicator, solvent-resistant containers, coagulation bath, vacuum filtration setup, vacuum oven.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Polymer Solution Preparation: Dissolve PVDF-HFP pellets (e.g., 10-15% w/v) in DMF with continuous stirring at 50-60°C until a clear, homogeneous solution is obtained.

- Nanofiller Dispersion: Separately, disperse the desired weight percentage (e.g., 1-7 wt%) of nanoclays in DMF using ultrasonication for 30-45 minutes to exfoliate the clay layers.

- Blending: Gradually add the nanoclay dispersion to the polymer solution with vigorous stirring. Continue stirring for several hours (e.g., 4-6 h) to ensure homogeneous mixing.

- Solvent Removal & Coagulation: Pour the blended solution slowly into a large excess of vigorously stirred non-solvent (e.g., water or methanol). This causes the polymer nanocomposite to coagulate and precipitate.

- Washing and Drying: Collect the precipitated nanocomposite by vacuum filtration. Wash thoroughly with fresh non-solvent to remove residual DMF. Dry the final product in a vacuum oven at 60-80°C for at least 24 hours until constant weight is achieved [36].

Melt Compounding

Melt compounding involves the mechanical mixing of nanoparticles with a polymer melt using high-shear equipment, typically twin-screw extruders. This solvent-free process is highly attractive for industrial-scale production due to its compatibility with existing polymer processing infrastructure, environmental friendliness, and high efficiency.

Experimental Protocol: Melt Compounding of PA6/Organoclay Nanocomposites

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Polyamide 6 (PA6) Matrix: Engineering thermoplastic with good mechanical properties.

- Organically Modified Clay (e.g., Cloisite 15A): Swells and exfoliates under shear to enhance properties [37].

- Compatibilizer: Maleic anhydride-grafted polypropylene (PP-g-MA) - Improves interfacial adhesion in non-polar systems (optional for PA6) [37] [40].

Equipment: Twin-screw extruder, drying oven, gravimetric feeders, water bath, pelletizer.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Material Pre-conditioning: Dry PA6 pellets and organoclay in a vacuum oven at 80°C for 12 hours to remove moisture.

- Feeding: Pre-mix the dried PA6 pellets with the target weight percentage (e.g., 2-5 wt%) of organoclay using a tumble blender. For polyolefin matrices, include 2-5% compatibilizer.

- Melt Compounding: Feed the pre-mix into a twin-screw extruder using a gravimetric feeder. Set appropriate temperature profiles along the extruder barrels (e.g., 230-260°C for PA6) and screw speed (e.g., 200-300 rpm) to achieve optimal shear mixing.

- Strand Pelletizing: Extrude the melt through a strand die, cool the strands in a water bath, and pelletize using a rotary cutter.

- Post-Processing: Dry the pellets again before subsequent processing steps like injection molding or compression molding [37].

Advanced Considerations and Emerging Trends

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential materials for polymer nanocomposite fabrication

| Material Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanofillers | Carbon nanotubes (CNTs), Graphene, Nanoclays, Silver nanoparticles | Impart enhanced mechanical, electrical, thermal, or antimicrobial properties [4] [36] [40] | Surface energy and aspect ratio critically influence dispersion and percolation threshold [40] |

| Polymers | Polyamide (PA), Polypropylene (PP), Poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) | Act as the continuous matrix material | Polarity and functional groups affect nanoparticle compatibility |

| Compatibilizers | Maleic anhydride-grafted polymers (e.g., PP-g-MA) | Improve interfacial adhesion between filler and matrix [40] | Essential for non-polar polymers with polar nanofillers |

| Surfactants/Stabilizers | Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Prevent nanoparticle agglomeration in solutions and melts [36] | Used in in-situ and solution methods; choice depends on nanoparticle surface chemistry |

| Solvents | N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF), Toluene, Chloroform | Dissolve polymer and disperse nanoparticles in solution blending [36] | Selection based on solubility parameters, boiling point, and toxicity |

Advanced Methodological Frameworks

Future developments are increasingly focused on overcoming dispersion limitations through "create rather than add" approaches, such as in-situ generation of nanoparticles within polymer matrices [24] [36]. This strategy skips the thermodynamically challenging dispersion step entirely, instead creating nanoreinforcements during composite manufacturing. Examples include the cold drawing of polymer blends to generate nanofibrils or the chemical transformation of precursors directly within the polymeric host [24] [36]. Furthermore, advanced manufacturing techniques like 3D printing are being integrated with nanocomposite fabrication, enabling the creation of complex, multifunctional architectures with precise nanofiller placement for applications in biomedicine, soft robotics, and electronics [35].

The convergence of electrospinning and 3D/4D printing represents a transformative advancement in the fabrication of polymer nanocomposites with complex architectures. While electrospinning enables the production of nano- to micro-scale fibrous structures that closely mimic the native extracellular matrix, it often results in scaffolds with insufficient mechanical properties for structurally complex tissues [41]. Conversely, 3D printing offers unparalleled geometrical freedom and control over macroscale architecture but typically struggles to achieve the nanoscale resolution required for optimal cellular interaction [41]. The synergy between these technologies creates a powerful platform for developing multi-scale hierarchical structures that overcome the individual limitations of each technique [42] [43].

This integration is particularly significant for biomedical applications, where the structural and functional complexity of native tissues demands sophisticated manufacturing approaches. The combination of electrospun nanofibers with 3D printed elements produces composite structures with superior properties, including enhanced mechanical strength, tailored porosity, and biomimetic topography that directs cellular behavior [42] [43] [44]. Furthermore, the emergence of 4D printing—which introduces the dimension of time through stimuli-responsive materials—adds dynamic functionality to these architectures, enabling shape-morphing behaviors or controlled degradation profiles that better replicate physiological processes [45].

Fundamental Principles and Technologies

Electrospinning Fundamentals

Electrospinning is a nanofabrication technique that utilizes high electric voltages to produce polymeric fibers with diameters ranging from micro- to nanometers [44]. The process involves applying a strong electric field between a polymer solution or melt contained in a spinneret (typically a metallic needle connected to a syringe) and a conductive collector. When the electrostatic forces overcome the surface tension of the polymer solution, a Taylor cone forms at the needle tip, and a charged polymer jet is ejected toward the collector [41]. This jet undergoes stretching and whipping instabilities during its trajectory, leading to extreme fiber thinning and eventual solidification through solvent evaporation or cooling, resulting in the deposition of solid nanofibers on the collector [41] [44].

Critical Parameters Influencing Electrospinning:

Solution and Polymer Parameters: Polymer molecular weight and concentration directly affect solution viscosity, which determines fiber morphology. Lower molecular weights or concentrations often result in bead formation instead of continuous fibers, while excessively high values can cause clogging [41]. Solvent choice impacts solution conductivity, dielectric constant, and evaporation rate, all influencing final fiber diameter and morphology [41].

Process Parameters: Applied voltage (typically 10-25 kV) controls the electrostatic forces driving fiber formation and stretching [41]. The tip-to-collector distance affects jet flight time and solvent evaporation rate, with greater distances generally producing thinner, more uniform fibers [41]. Flow rate determines solution volume available for electrospinning, with lower rates typically yielding thinner fibers [41].

3D/4D Printing Technologies

3D printing, or additive manufacturing (AM), encompasses a suite of technologies that build three-dimensional objects layer-by-layer from digital models, offering unrivalled geometrical freedom and customization capabilities [44]. In the context of polymer nanocomposites, extrusion-based methods like fused filament fabrication (FFF) are particularly relevant, where thermoplastic filaments are melted and deposited through a nozzle according to computer-controlled paths [46]. These techniques allow the fabrication of highly complex components with tailored architectures but are generally considered "low-resolution" techniques compared to electrospinning, with limited ability to manipulate structural details at the submicrometric scale [41].

4D printing represents an advanced evolution of 3D printing, where the fabricated structures can change their shape, properties, or functionality over time in response to external stimuli such as temperature, moisture, light, or magnetic fields [45]. This dynamic behavior is achieved through the use of smart materials, including shape-memory polymers, hydrogels, and stimuli-responsive composites. When combined with electrospun nanofibers, 4D printing enables the creation of sophisticated structures that can undergo programmed morphological changes, offering exciting possibilities for advanced biomedical applications such as self-fitting implants or programmable drug delivery systems [45].

Integrated Fabrication Approaches and Quantitative Analysis

Hybrid Fabrication Strategies

The integration of electrospinning and 3D/4D printing has primarily been realized through two distinct fabrication approaches, each offering unique advantages for specific applications.

Multi-Layered Architectures: This approach involves the sequential or alternating deposition of electrospun nanofibers and 3D printed elements to create composite scaffolds with multi-scale hierarchical organization [43] [44]. In one implementation, a 3D printed framework provides structural support and macroscopic geometry, while electrospun nanofibers integrated between printed layers enhance biomimetic topography and cellular interaction [41] [44]. This strategy has been successfully applied to tissue engineering scaffolds, where the 3D printed components maintain structural integrity while the electrospun layers improve cell seeding efficiency and tissue formation [44]. For instance, primary bovine articular chondrocyte entrapment and extracellular matrix production were significantly enhanced in alternating layers of electrospun nanofibers and 3D printed meshes compared to single-technology constructs [44].

Fiber-Reinforced Composite Inks: This approach incorporates electrospun nanofibers directly into 3D printing inks prior to the printing process, creating composite materials with enhanced mechanical properties and functionality [43] [44]. The nanofibers act as reinforcement within the printed matrix, improving tensile strength, storage modulus, and other mechanical characteristics while maintaining printability [46] [43]. This method overcomes challenges associated with poor dispersion of conventional nanoscale additives in polymer melts and the difficult processability of resulting high-viscosity materials [46]. A notable example includes the fabrication of poly(lactide acid) (PLA) nanocomposites with electrospun nanofiber interleaves, where systematic variation of nanofiber content demonstrated significant improvements in mechanical properties [46].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Hybrid Fabrication Approaches

| Parameter | Multi-Layered Architecture | Fiber-Reinforced Composite Inks |

|---|---|---|

| Fabrication Sequence | Sequential deposition of electrospun mats and 3D printed elements | Pre-incorporation of fibers into printing ink before fabrication |

| Mechanical Reinforcement | Through interlayer adhesion and distribution | Through homogeneous dispersion within matrix |

| Structural Control | Macroscopic (3D printing) and microscopic (electrospinning) | Primarily macroscopic with enhanced bulk properties |

| Material Compatibility | Can combine disparate materials in discrete layers | Requires compatibility between fibers and matrix material |

| Key Advantages | Independent optimization of each layer, high customizability | Improved mechanical properties, simplified fabrication process |

| Limitations | Potential delamination, complex process optimization | Potential nozzle clogging, fiber alignment challenges |