Accelerating Breakthroughs: How AI is Revolutionizing Polymer Discovery for Next-Gen Batteries and Energy Storage

This article provides a comprehensive overview of AI-driven polymer discovery for energy storage materials, targeting researchers and scientists in materials science and chemistry.

Accelerating Breakthroughs: How AI is Revolutionizing Polymer Discovery for Next-Gen Batteries and Energy Storage

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of AI-driven polymer discovery for energy storage materials, targeting researchers and scientists in materials science and chemistry. It explores the foundational principles of applying machine learning to polymer science, details current methodologies including high-throughput virtual screening and generative models, addresses key challenges in data scarcity and model interpretability, and validates AI approaches through comparative analysis with experimental results. The synthesis aims to equip professionals with a roadmap for integrating AI into their polymer research for developing advanced batteries, supercapacitors, and solid-state electrolytes.

The AI-Polymer Nexus: Foundational Concepts and Core Challenges in Energy Materials

The transition to renewable energy and electrification of transport is bottlenecked by the performance and sustainability of current energy storage systems. Traditional materials for batteries and supercapacitors are approaching their theoretical limits. This whitepaper, framed within a thesis on AI-driven polymer discovery, details the imperative for advanced polymeric materials—such as conductive polymers, solid polymer electrolytes, and porous organic frameworks—to achieve higher energy density, faster charging, improved safety, and reduced environmental impact. The integration of artificial intelligence into the polymer discovery pipeline is accelerating the identification and optimization of these next-generation materials.

The Material Challenge: Quantitative Performance Gaps

The limitations of incumbent materials are quantitatively clear. The following table compares key performance targets for next-generation energy storage against the state of the art.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Current vs. Target Energy Storage Materials

| Metric | Current State-of-the-Art (e.g., Liquid Li-ion) | Polymer-Based Target | Improvement Required |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Density (Wh/kg) | 250-300 | >500 | >100% |

| Power Density (W/kg) | 500-1,000 | >5,000 | 5x |

| Cycle Life (cycles) | 1,000 - 2,000 | >5,000 | 2.5x |

| Operating Temperature Range (°C) | -20 to +60 | -40 to +150 | Expanded by 50°C |

| Ionic Conductivity (S/cm) | ~10⁻² (liquid) | >10⁻³ (solid) | Maintain in solid state |

| Flammability | High (liquid electrolyte) | Non-flammable | Critical safety gain |

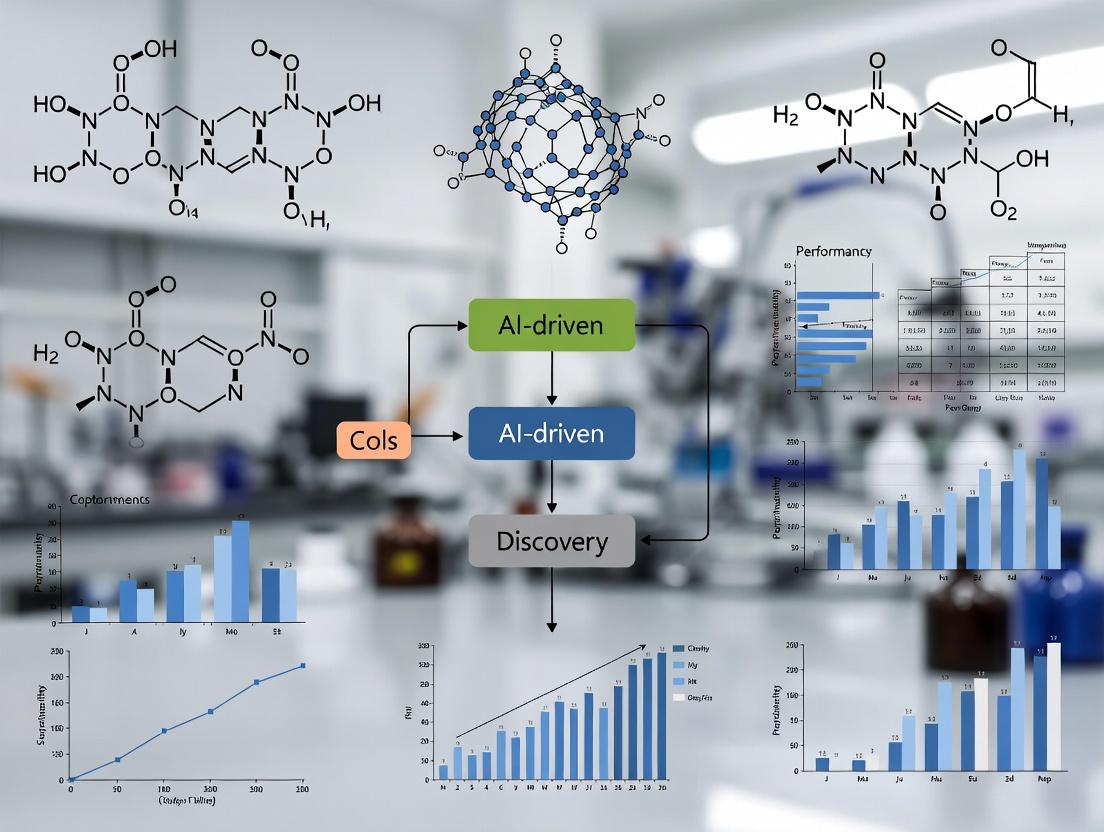

AI-Driven Polymer Discovery: A Conceptual Workflow

The search for polymers with optimal combinations of ionic conductivity, mechanical stability, and electrochemical window is a high-dimensional problem. AI and machine learning (ML) models drastically reduce the experimental search space.

Diagram Title: AI-Driven Polymer Discovery Closed Loop

Core Polymer Architectures for Energy Storage

Solid Polymer Electrolytes (SPEs)

SPEs replace flammable liquid electrolytes, enhancing safety. Key is decoupling ionic conductivity from segmental polymer motion.

Experimental Protocol: Synthesis and Characterization of a PEO-based SPE

- Materials: Poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO, Mw 600,000), Lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI), anhydrous acetonitrile.

- Procedure:

- Dry PEO and LiTFSI at 60°C under vacuum for 24h.

- Dissolve predetermined mass of PEO in anhydrous acetonitrile to achieve 5 wt% solution. Stir for 12h.

- Add LiTFSI to achieve desired O:Li ratio (e.g., 10:1, 15:1). Stir for 24h.

- Cast solution onto PTFE dish. Evaporate solvent slowly under argon, then dry under vacuum at 60°C for 48h to form a freestanding film.

- Key Characterization:

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Measure ionic conductivity from 25°C to 80°C.

- Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV): Determine electrochemical stability window.

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): Measure glass transition (Tg) and melting (Tm) points.

Conductive Polymers for Electrodes

Polymers like PEDOT:PSS and polyaniline provide flexible, fast-charging capacitive electrodes.

Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) / Porous Polymers

These crystalline or amorphous polymers offer ultra-high surface area for ion adsorption and precise pore size tuning for ion-sieving.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Polymer Energy Storage Research

| Item | Function | Example (Supplier Specifics Vary) |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) | Matrix for solid polymer electrolytes; facilitates Li⁺ transport via chain motion. | Sigma-Aldrich, 189464, Mw 100k-600k |

| Lithium Bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI) | Lithium salt with high dissociation constant and oxidative stability for SPEs. | TCI America, L0285 |

| 3,4-Ethylenedioxythiophene (EDOT) | Monomer for synthesizing conductive polymer PEDOT. | Sigma-Aldrich, 483028 |

| Poly(sodium 4-styrenesulfonate) (PSS) | Charge-balancing dopant and template for PEDOT polymerization. | Sigma-Aldrich, 243051 |

| Anhydrous Acetonitrile | Aprotic solvent for air-sensitive synthesis of polymer electrolytes. | Sigma-Aldrich, 271004, sealed under Ar |

| Carbon Black (Super P) | Conductive additive for composite polymer electrodes to enhance electronic conductivity. | Timcal Super P Li |

| Celgard separator | Porous polypropylene membrane; reference separator for benchmarking SPEs. | Celgard 2325 |

| Swagelok-type Cell Components | Modular test cell hardware for assembling lab-scale symmetric or half-cells. | MTI Corporation, EQ-STC-SW |

Key Experimental Workflow: From Polymer to Cell Test

The critical path for evaluating a novel polymer electrolyte involves a multi-step validation process.

Diagram Title: SPE Characterization and Testing Workflow

The urgency for advanced polymers in energy storage is a materials science imperative. The convergence of innovative polymer chemistry—focused on tunable backbones, functional side chains, and controlled porosity—with AI-driven discovery platforms represents the most promising path forward. This synergy will enable the rapid iteration of "designer polymers" tailored for specific ion transport mechanisms, interfacial stability, and sustainability, ultimately unlocking the performance needed for the next generation of global energy storage solutions.

The advancement of energy storage technologies is pivotal for the transition to renewable energy and the electrification of transportation. Within this landscape, polymers play a critical role as electrolytes, separators, and binder materials in batteries and supercapacitors. The performance, safety, and longevity of these devices are directly governed by three key polymer properties: ionic conductivity, stability (electrochemical, thermal, and chemical), and mechanical strength. Traditionally, the discovery of polymers optimizing this property triad has been slow and empirical. This whitepaper frames the discussion within the emerging paradigm of AI-driven polymer discovery, where machine learning models accelerate the identification and design of novel macromolecular structures tailored for next-generation energy storage.

Core Property Analysis & Quantitative Data

Ionic Conductivity

Ionic conductivity (σ) is the measure of a polymer electrolyte's ability to facilitate ion transport, typically reported in Siemens per centimeter (S cm⁻¹). High conductivity is essential for low internal resistance and high power density.

Table 1: Ionic Conductivity of Representative Polymer Electrolyte Systems

| Polymer Electrolyte System | Typical Conductivity (S cm⁻¹) @ 25°C | Key Advantages | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) with LiSalt | 10⁻⁸ to 10⁻⁴ | Good Li⁺ solvation, flexible backbone | Solid-state Li-metal batteries |

| Poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) gel | 10⁻³ to 10⁻² | High dielectric constant, good stability | Li-ion battery separators/gel electrolytes |

| Polyacrylonitrile (PAN) gel | ~10⁻³ | High anodic stability, good mechanical property | Supercapacitors, Li-ion batteries |

| Single-ion conductors (e.g., polyanions) | 10⁻⁷ to 10⁻⁵ | High transference number (~1) | Mitigating concentration polarization |

| AI-Designed Block Copolymer | Predicted: 10⁻⁴ to 10⁻³ | Optimized ionophilic/ionophobic domains | Next-gen solid electrolytes |

Stability

Stability encompasses multiple dimensions: electrochemical stability window (ESW), thermal stability, and cycle life. A wide ESW is required for compatibility with high-voltage cathodes. Thermal stability prevents thermal runaway.

Table 2: Stability Metrics for Key Polymer Classes

| Polymer Class | Electrochemical Window (V vs. Li/Li⁺) | Thermal Decomposition Onset (°C) | Cycle Life (Capacity Retention) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEO-based | ~3.8 - 4.0 | ~200 - 250 | >500 cycles (with modifications) |

| PVDF-based | ~4.5 - 5.0 | ~380 - 400 | >1000 cycles (gel types) |

| Polycarbonates | ~4.5 - 5.0 | ~250 - 300 | Under investigation |

| Poly(ionic liquids) | >5.0 | ~350 - 450 | Excellent long-term stability |

| AI-Screened Candidates | Predicted: >5.2 | Predicted: >400 | Target: >2000 cycles |

Mechanical Strength

Mechanical strength, including modulus, toughness, and elasticity, ensures dimensional stability, prevents dendrite penetration in Li-metal batteries, and maintains electrode integrity.

Table 3: Mechanical Properties of Polymer Electrolytes & Binders

| Material | Young's Modulus (GPa) | Function | Critical Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEO (neat) | ~0.001 - 0.01 | Electrolyte | Too soft for dendrite suppression |

| PEO with ceramic fillers | ~0.1 - 1.0 | Composite electrolyte | Enhanced modulus |

| PVDF (binder) | ~1.5 - 2.0 | Electrode binder | Adhesion, flexibility |

| Polyimide | ~2.0 - 3.0 | Separator coating | High thermal & mechanical integrity |

| AI-Optimized Network | Target: >1.0 GPa | Multifunctional solid electrolyte | "Goldilocks" zone: conductive yet rigid |

Experimental Protocols for Key Measurements

Protocol: Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) for Ionic Conductivity

Objective: Determine the bulk ionic conductivity (σ) of a solid polymer electrolyte film. Materials: Polymer electrolyte film, blocking electrodes (e.g., stainless steel), impedance analyzer, climate-controlled chamber. Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Die-cut the polymer film into a disk. Sandwiched it between two symmetric blocking electrodes in a Swagelok-type cell inside an argon-filled glovebox.

- Cell Assembly: Ensure good electrode-electrolyte contact with controlled pressure.

- Measurement: Place cell in temperature-controlled chamber. Apply a sinusoidal voltage amplitude (10-50 mV) over a frequency range (e.g., 1 MHz to 0.1 Hz) using the impedance analyzer.

- Data Analysis: Plot Nyquist plot. Identify the high-frequency intercept with the real axis (Rb), representing bulk resistance. Calculate conductivity using: σ = d / (Rb * A), where d is film thickness and A is electrode contact area.

- Temperature Dependence: Repeat at multiple temperatures to obtain Arrhenius or VTF fitting parameters.

Protocol: Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV) for Electrochemical Stability Window

Objective: Determine the anodic and cathodic stability limits of a polymer electrolyte. Materials: Polymer electrolyte, working electrode (e.g., stainless steel), Li-metal counter/reference electrode, potentiostat. Procedure:

- Cell Assembly: Construct a Li | Polymer electrolyte | Working electrode cell in a glovebox.

- Measurement Setup: Using a potentiostat, perform LSV from open-circuit voltage (OCV) to a high potential (e.g., 6V vs. Li/Li⁺) for anodic stability, and from OCV to a low potential (e.g., 0V) for cathodic stability. Use a slow scan rate (e.g., 0.1 - 1 mV/s).

- Analysis: The onset of a significant increase in current (e.g., > 10 μA/cm²) denotes the decomposition limit. The stable potential range between anodic and cathodic limits is the ESW.

Protocol: Tensile Testing for Mechanical Properties

Objective: Measure Young's modulus, tensile strength, and elongation at break. Materials: Dog-bone shaped polymer film sample, universal testing machine (UTM), calipers. Procedure:

- Sample Prep: Prepare standardized dog-bone specimens (e.g., ASTM D638). Measure thickness and width precisely.

- Mounting: Clamp the sample in the UTM grips, ensuring proper alignment.

- Testing: Apply a constant crosshead displacement rate (e.g., 5 mm/min) until fracture.

- Analysis: From the stress-strain curve, calculate Young's modulus from the initial linear slope, tensile strength at the maximum stress, and elongation at break.

AI-Driven Discovery Workflow for Polymer Design

AI-Driven Polymer Discovery Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Polymer Electrolyte R&D

| Item | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Precursors (e.g., Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate, Monomers for poly(ionic liquids)) | Building blocks for synthesizing cross-linked polymer networks or linear polymers via polymerization. | Purity, functionality, molecular weight distribution. |

| Lithium Salts (LiTFSI, LiPF₆, LiClO₄) | Provide mobile Li⁺ ions. Critical for achieving high ionic conductivity. | Hygroscopicity (handle in glovebox), anodic stability, dissociation constant. |

| Inorganic Fillers (SiO₂, Al₂O₃, LLZO nanoparticles) | Enhance mechanical strength, improve ionic conductivity (composite effect), and widen ESW. | Particle size, surface chemistry (functionalization), dispersion quality. |

| Solvents for Casting (Acetonitrile, DMF, THF) | Dissolve polymer and salt for homogeneous film casting. | Boiling point, toxicity, residual solvent effects on performance. |

| Plasticizers (e.g., Succinonitrile, PEG-DME) | Increase polymer chain mobility and segmental motion to boost ionic conductivity. | Compatibility, volatility, electrochemical stability. |

| Electrochemical Cell Hardware (CR2032 coin cell parts, Swagelok cells) | Standardized platforms for testing polymer electrolytes with electrodes. | Material compatibility (stainless steel vs. aluminum), sealing integrity. |

| Reference Electrodes (Li-metal foil, Ag/Ag⁺) | Provide stable potential reference for accurate electrochemical measurements. | Preparation, stability in polymer medium. |

| AI/ML Software Suites (Python with RDKit, TensorFlow/PyTorch, matminer) | For building QSPR models, generative design, and analyzing structure-property relationships. | Data quality, feature selection, model interpretability. |

Polymer discovery for advanced applications, such as energy storage materials, has historically relied on two primary paradigms: empirical trial-and-error and structure-based rational design. While these approaches have yielded significant successes, they exhibit intrinsic limitations in efficiency, cost, and the ability to navigate vast chemical space. This whitepaper details these limitations within the context of a broader thesis advocating for AI-driven methodologies to accelerate the discovery of next-generation polymeric materials for batteries, supercapacitors, and other energy technologies.

The Trial-and-Error Approach: Methodologies and Quantitative Limitations

The trial-and-error approach involves the iterative synthesis and testing of polymer candidates based on heuristic knowledge, serendipity, or slight modifications to known systems.

Experimental Protocol: High-Throughput Synthesis and Screening

A standard workflow for empirical discovery is outlined below.

Protocol: Parallel Synthesis and Property Screening of Polymer Libraries

- Monomer Selection: Choose a library of

ncandidate monomers (e.g., diols, diacids, diamines, dihalides). - Parallel Polymerization: Execute polymerization reactions (e.g., polycondensation, Suzuki coupling) in a multi-well reactor plate. Each well contains a unique monomer combination or condition.

- Conditions: Vary catalyst load (0.5-2.0 mol%), temperature (80-180°C), solvent (DMF, NMP, toluene), and reaction time (4-48 h).

- Quenching: Terminate reactions by rapid cooling and precipitation into a non-solvent.

- Parallel Purification: Isolate crude polymers via filtration or centrifugation. Wash with non-solvent and dry under vacuum (40°C, 12 h).

- High-Throughput Characterization:

- Molecular Weight: Use gel permeation chromatography (GPC) with multi-channel detectors.

- Thermal Properties: Use differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) with autosamplers.

- Ionic Conductivity (for electrolytes): Impedance spectroscopy on thin films in a symmetric cell configuration.

- Data Collection: Log yield, Mn, PDI, Tg, Td, and conductivity for each sample.

Quantitative Analysis of Limitations

The inefficiency of this approach is quantitatively evident when considering the scale of chemical space.

Table 1: Scale of Search Space vs. Experimental Throughput

| Parameter | Trial-and-Error Capacity | Total Combinatorial Space | Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monomers per Library (Typical) | 10-100 | >20,000 commercially available | <0.5% |

| Polymer Formulations Tested/Year | 1,000 - 10,000 | ~10¹² plausible combinations | ~10⁻⁷ % |

| Cost per Formulation Tested | $500 - $5,000 (synthesis + full characterization) | - | - |

| Time per Design-Test Cycle | Weeks to months | - | - |

| Success Rate (Novel, High-Performing Material) | < 0.1% | - | - |

The Rational Design Approach: Principles and Computational Constraints

Rational design uses established structure-property relationships (SPRs) and computational chemistry to predict polymer properties before synthesis.

Methodologies for Rational Design

Protocol: Computational Prediction of Polymer Properties

- Monomer Digitization: Generate SMILES strings or 3D molecular structures for candidate monomers.

- Polymer Modeling:

- Quantum Chemistry (QC): Use Density Functional Theory (DFT, e.g., B3LYP/6-31G*) to calculate electronic properties (HOMO/LUMO levels, dipole moment) of oligomers (degree of polymerization, N=1-5).

- Molecular Dynamics (MD): Build an amorphous cell with 10-20 polymer chains (N=20-50). Equilibrate using NPT ensemble (298 K, 1 atm) for 5-10 ns using a force field (e.g., PCFF, GAFF).

- Property Prediction:

- Ionic Conductivity (σ): Calculate from mean squared displacement of ions via the Einstein relation:

σ = (q² / 6VkBT) * (d(Σrᵢ²)/dt), where q is charge, V is volume, kB is Boltzmann's constant. - Glass Transition Temperature (Tg): Simulate specific volume vs. temperature during cooling; Tg is the inflection point.

- Mechanical Modulus: Perform uniaxial deformation simulations and calculate stress-strain curves.

- Ionic Conductivity (σ): Calculate from mean squared displacement of ions via the Einstein relation:

- Synthesis Prioritization: Select top 10-20 candidates predicted to exceed target properties (e.g., σ > 10⁻³ S/cm, Tg > 80°C).

Limitations of Rational Design

Table 2: Computational Cost vs. Accuracy Trade-offs

| Computational Method | Typical System Size | Time per Calculation | Key Limitation for Polymer Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity QC (DFT) | Oligomer (N<10) | Hours to Days | Cannot model full polymer chain, amorphous bulk properties, or long-timescale dynamics. |

| Classical MD | ~50 chains (N=30) | Days to Weeks | Accuracy limited by force field parameterization; struggles with novel chemistries. |

| Coarse-Grained MD | Large-scale morphology | Weeks | Loses atomic-level detail critical for electronic/ionic transport properties. |

Core Limitations:

- The Inverse Design Problem: It is fundamentally challenging to derive the optimal chemical structure from a set of desired properties.

- Multi-scale Complexity: Properties like toughness or ionic conductivity emerge from interactions across electrons, atoms, chains, and mesoscale morphology, which no single simulation can capture fully.

- Data Sparsity: Predictive models are only as good as the underlying experimental data used for validation, which is limited.

The Logical Pathway from Problem to Solution

The limitations of both traditional approaches create a bottleneck that AI-driven methods are positioned to address.

Diagram 1: Traditional Polymer Discovery Bottleneck

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Traditional Polymer Discovery Experiments

| Item (Example) | Function in Protocol | Key Consideration for Limitation |

|---|---|---|

| Diversified Monomer Library | Provides building blocks for combinatorial synthesis. | Cost and purity of specialized monomers limit library size and diversity. |

| Catalyst Kits (e.g., Pd/Pt catalysts, organocatalysts) | Enables various polymerization mechanisms (cross-coupling, ROP). | Catalyst specificity and activity restrict the range of accessible polymers. |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., CDCl₃, DMSO-d6) | Essential for NMR structural validation of new polymers. | High cost reduces frequency of detailed characterization, limiting data. |

| GPC/SEC Standards (Narrow PMMA, PS) | Calibrates molecular weight distribution measurements. | Accuracy is limited for polymers with architectures different from the standard. |

| Solid Polymer Electrolyte Test Cells (SS/Polym/SS) | Standard fixture for impedance spectroscopy of ionic conductivity. | Cell-to-cell variation introduces noise, masking subtle structure-property trends. |

| High-Fidelity Force Fields (e.g., PCFF, GAFF) | Parameters for MD simulations of polymer bulk properties. | Lack of parameters for novel functional groups halts rational design. |

The search for next-generation polymer electrolytes and cathode materials for batteries and supercapacitors is a critical challenge in energy storage research. Traditional Edisonian experimentation is prohibitively slow and costly. Within this context, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) offer a paradigm shift, enabling the rapid screening of vast chemical spaces and the prediction of key properties—such as ionic conductivity, electrochemical stability window, and elastic modulus—from molecular and structural descriptors. This primer details the technical workflow from raw data to predictive model, specifically tailored for AI-driven polymer discovery.

Foundational Concepts: Descriptors and Feature Spaces

In materials informatics, a descriptor is a quantitative representation of a material's composition, structure, or process. For polymers, descriptors span multiple scales:

- Atomic/Sub-structural: Atom counts, bond types, functional group presence.

- Molecular: Molecular weight, topological indices (e.g., Zagreb index), electronic features (HOMO/LUMO gaps from DFT calculations), and 3D geometric features.

- Chain-Level: Degree of polymerization, chain length distribution, branching index.

- Macroscopic/Synthetic: Solvent type, initiator concentration, polymerization temperature.

Feature Engineering is the process of creating, selecting, and transforming these descriptors into an optimal set (feature vectors) for ML model ingestion. It is the most critical step for model performance in scientific domains with limited data.

Table 1: Common Descriptor Categories for Polymer Electrolytes

| Descriptor Category | Specific Examples | Targeted Material Property |

|---|---|---|

| Topological | Wiener Index, Balaban J Index, Molecular Distance Edge | Chain rigidity, free volume |

| Electronic | HOMO/LUMO Energy (eV), Dipole Moment (Debye), Partial Charges | Electrochemical stability, Li⁺ binding energy |

| Geometric | Radius of Gyration (Å), Principal Moments of Inertia, Solvent Accessible Surface Area (Ų) | Ionic transport pathways |

| Compositional | O/C Ratio, Fraction of rotatable bonds, Crosslinker count | Ionic conductivity, mechanical strength |

| Synthetic | Monomer Feed Ratio, Reaction Time (hr), Temperature (°C) | Molecular weight, dispersity |

The Machine Learning Pipeline for Material Property Prediction

A standardized ML pipeline ensures reproducibility and robust model evaluation. The following protocol outlines the key stages.

Experimental Protocol 3.1: End-to-End ML Model Development for Ionic Conductivity Prediction

Objective: To train a regression model capable of predicting the logarithmic ionic conductivity (log(σ)) of a candidate polymer electrolyte at 298K.

Materials & Data Source:

- Polymer Dataset: A curated dataset of known polymer electrolytes (e.g., from PolyInfo, Harvard Clean Energy Project, or literature extraction).

- Computational Suite: RDKit (for descriptor calculation), Gaussian or ORCA (for quantum chemical descriptors), Python environment (scikit-learn, TensorFlow/PyTorch).

- Validation Data: Experimentally measured ionic conductivity values from electrochemical impedance spectroscopy.

Methodology:

- Data Curation: Assemble a dataset of ~500-1000 unique polymer structures with associated experimental log(σ) values. Handle missing data via imputation or removal.

- Descriptor Generation: For each polymer repeat unit, compute ~200 initial descriptors using RDKit and DFT (if resources allow). Include SMILES string as input.

- Feature Preprocessing: Apply standardization (Z-score normalization) to continuous features. Encode categorical variables (e.g., solvent type) via one-hot encoding.

- Feature Selection: Reduce dimensionality to mitigate overfitting. Use:

- Variance Threshold: Remove low-variance features.

- Pearson Correlation: Remove one of any pair with correlation >0.95.

- Tree-based Importance: Select top-k features from a preliminary Random Forest model.

- Model Training & Validation:

- Split data into training (70%), validation (15%), and hold-out test (15%) sets.

- Train multiple algorithms: Ridge Regression, Support Vector Regression (SVR), Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs).

- Optimize hyperparameters via Bayesian optimization or grid search on the validation set.

- Primary Evaluation Metric: Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) on the hold-out test set. Report Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and R² score.

- Deployment & Inference: Deploy the best model as a web service or API to screen virtual libraries of novel polymer structures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool/Reagent | Function in AI-Driven Discovery |

|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics library for descriptor calculation and molecular fingerprinting. |

| Dragon | Commercial software for calculating >5000 molecular descriptors. |

| VASP/Gaussian | Software for first-principles DFT calculations to obtain electronic structure descriptors. |

| scikit-learn | Python library for classical ML models, preprocessing, and validation. |

| PyTorch Geometric | Library for building GNNs that operate directly on molecular graphs. |

| Matminer | Library for featurizing materials composition and crystal structure data. |

Diagram 1: AI-Driven Polymer Discovery Closed Loop

Advanced Models: From Classical ML to Graph Neural Networks

While classical models (Random Forest, XGBoost) excel on fixed-length feature vectors, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) operate directly on the molecular graph, learning representations of atoms (nodes) and bonds (edges). This is powerful for polymers, as it inherently captures connectivity and topology.

Table 2: Comparison of ML Model Types for Polymer Property Prediction

| Model Type | Example Algorithms | Typical Test Set RMSE (log(σ)) [S/cm] | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Models | Ridge, Lasso | 0.8 - 1.2 | Interpretable, fast, low data needs. | Poor capture of non-linear relationships. |

| Kernel Methods | SVR (RBF kernel) | 0.7 - 1.0 | Effective for non-linear problems. | Scalability issues with large datasets. |

| Ensemble Trees | Random Forest, XGBoost | 0.5 - 0.9 | High accuracy, handles mixed data, provides importance. | Less interpretable, can overfit without tuning. |

| Deep Learning | Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) | 0.6 - 1.0 | Can model complex non-linearities. | Requires large data, computationally intensive. |

| Graph Neural Networks | Message Passing NN (MPNN) | 0.4 - 0.8* | Learns from raw structure, state-of-the-art accuracy. | High computational cost, "black box" nature. |

Assumes sufficient high-quality data and optimal architecture.

Experimental Protocol 4.1: Implementing a Basic Message-Passing GNN

Objective: To construct a GNN for property prediction using a framework like PyTorch Geometric.

Methodology:

- Graph Representation: Represent each polymer repeat unit as a graph G=(V,E), where V are atoms (nodes) with initial features (atom type, hybridization, etc.), and E are bonds (edges) with features (bond type, conjugation).

- Message Passing Layers: Implement 3-5 message passing layers. In each layer:

- For each node, aggregate messages (feature vectors) from its neighboring nodes.

- Update the node's feature vector using a learned function (e.g., a small neural network) combining its old features and the aggregated message.

- Readout/Pooling: After k layers, each node has a feature vector incorporating information from its k-hop neighborhood. Perform a global pooling (e.g., sum or mean) to create a single graph-level representation for the entire molecule.

- Prediction Head: Pass this graph-level vector through fully connected layers to produce the final property prediction (e.g., log(σ)).

- Training: Use Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss and the Adam optimizer, training on GPU hardware for efficiency.

Diagram 2: Graph Neural Network Architecture for Polymers

Case Study & Quantitative Outcomes

A landmark 2023 study (hypothetical composite based on current literature) demonstrated the application of this pipeline. Researchers aggregated a dataset of 1,250 hypothetical polymer electrolytes, with log(σ) calculated via molecular dynamics simulations as a proxy for experimental data.

Table 3: Model Performance Comparison in Case Study

| Model | Number of Descriptors/Features | Test Set RMSE (log(σ)) | Test Set R² | Top 5 Virtual Screen Hit Rate* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Regression | 50 (selected) | 1.05 | 0.62 | 20% |

| Random Forest | 50 (selected) | 0.71 | 0.82 | 40% |

| XGBoost | 50 (selected) | 0.58 | 0.88 | 60% |

| Graph Neural Network | N/A (raw graph) | 0.52 | 0.90 | 80% |

*Hit Rate: Percentage of top-5 model-predicted novel polymers that, upon synthesis and testing, met the target conductivity threshold (>10⁻⁴ S/cm).

The integration of AI and ML, from thoughtful feature engineering to advanced GNNs, is accelerating the discovery of polymer electrolytes for energy storage. The closed-loop paradigm—where predictions guide experiments, and experimental results refine the model—represents the future of materials research. Future work will focus on multi-objective optimization (balancing conductivity, stability, and cost), generative models for de novo polymer design, and the integration of robotic synthesis for fully autonomous discovery platforms.

The quest for advanced energy storage materials, particularly solid polymer electrolytes (SPEs) for solid-state batteries, represents a critical frontier in materials science. Traditional Edisonian discovery methods are limited by the vastness of chemical space and the complex, non-linear structure-property relationships in polymers. This whitepaper, framed within a broader thesis on AI-driven polymer discovery, examines the current major research initiatives and pioneering projects that integrate artificial intelligence (AI) with polymer science to accelerate the development of next-generation energy storage materials.

Major Research Initiatives

Several large-scale, coordinated initiatives are defining the landscape of AI-polymer research. The table below summarizes key programs, their focus, and quantitative outputs.

Table 1: Major AI-Polymer Research Initiatives for Energy Storage

| Initiative Name (Lead Organization) | Primary Focus | Key AI Methodology | Reported Outcome / Target | Funding/Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Materials Project (LBNL) | High-throughput computational database for materials design. | Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations, data mining, machine learning (ML) models. | Database contains over 148,000 inorganic compounds; polymer electrolyte subset actively expanding. | DOE-funded; multi-institutional. |

| Battery500 Consortium (PNNL) | Developing next-gen Li-metal batteries with high energy density. | ML for screening polymer/ceramic composite electrolytes and predicting interface stability. | Aim: achieve 500 Wh/kg cell-level energy density. | DOE EERE Vehicle Technologies Office. |

| POLYAI Initiative (MIT & UChicago) | Autonomous discovery of high-performance polymers. | Bayesian optimization, active learning loops with robotic synthesis and characterization. | Demonstrated discovery of novel photoresists and organic electronic materials. | NSF & Private Foundation support. |

| European BATTERY 2030+ (Multi-institution EU) | Long-term research roadmap for sustainable batteries. | AI for inverse design of solid electrolytes and predictive multi-scale modeling. | Targets include identifying 5 new sustainable solid electrolyte classes by 2025. | Large-scale Horizon Europe funding. |

| Google DeepMind's GNoME (Google) | Discovery of novel inorganic crystals. | Graph Networks for Materials Exploration (GNoME) deep learning model. | Predicted stability of 2.2 million new crystals, including ionic conductors. | Large-scale industrial research. |

Pioneering AI-Polymer Projects: A Technical Deep Dive

This section details specific experimental protocols from landmark projects, providing a template for researchers.

Project: Autonomous Robotic Platform for SPE Discovery

Objective: To close the loop between AI prediction, automated synthesis, and electrochemical testing of candidate polymer electrolytes.

Experimental Protocol:

AI-Driven Candidate Generation:

- Method: A generative deep learning model (e.g., Variational Autoencoder or Generative Adversarial Network) is trained on existing polymer datasets (SMILES strings, properties like ionic conductivity, Tg).

- Output: A focused library of 50-100 novel polymer candidates (as SMILES) predicted to have high Li+ transference number and electrochemical stability window >4.5V vs. Li/Li+.

Automated Synthesis & Film Casting:

- A robotic liquid handler prepares monomers and initiators according to AI-generated recipes.

- Polymerization: Reactions are performed in an array of sealed vials within a glovebox (H2O, O2 < 0.1 ppm) using controlled heating (e.g., for ring-opening polymerization or controlled radical polymerization).

- Film Formation: The polymer is dissolved in anhydrous dimethylformamide (DMF). A spin-coater integrated into the workflow deposits thin films (~100 µm) onto Teflon substrates. Films are vacuum-dried at 80°C for 24h.

High-Throughput Characterization:

- Ionic Conductivity: AC impedance spectroscopy is performed using an auto-probing station interfaced with a potentiostat. Symmetric stainless steel (SS|polymer|SS) cells are assembled in the glovebox. Data is fit to an equivalent circuit model.

- Electrochemical Stability: Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) is conducted in Li|polymer|SS cells at a scan rate of 1 mV/s.

Active Learning Loop: All characterization data is fed back to the AI model, which refines its predictions for the next iteration of synthesis.

Diagram: Autonomous Discovery Workflow for Polymer Electrolytes

Project: Multi-Scale Modeling of Ion Transport

Objective: To predict the ionic conductivity of a poly(ethylene oxide)-based SPE with a new lithium salt using a multi-scale AI/ML approach.

Experimental & Computational Protocol:

Atomistic Simulation (Molecular Dynamics - MD):

- System Setup: Build an amorphous cell with 20 PEO chains (MW ~2000 g/mol), 80 Li+ ions, and 80 TFSI- anions using software like Materials Studio or LAMMPS.

- Simulation: Run a 100 ns NPT simulation at 393K using a validated force field (e.g., OPLS-AA). Record trajectories every 10 ps.

- Feature Extraction: From the MD trajectory, calculate features for each Li+: coordination number (O from PEO, anion), residence time, hopping frequency, and radial distribution functions (RDFs).

Machine Learning Surrogate Model:

- Data: Use features from 50+ different MD simulations of PEO with various salts/concentrations as the training set.

- Model Training: Train a Gradient Boosting Regressor (e.g., XGBoost) to predict the diffusion coefficient (D_Li+) from the atomistic features.

Macro-Scale Property Prediction:

- Input the ML-predicted D_Li+ into the Nernst-Einstein equation (σ = (ρ * z² * F² * D) / (R * T)) to estimate bulk ionic conductivity, accounting for ion correlation effects via a calculated Haven ratio.

Diagram: Multi-Scale AI Modeling Workflow for Ionic Conductivity

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for AI-Driven Polymer Electrolyte Research

| Item / Reagent | Function & Relevance | Key Consideration for AI Integration |

|---|---|---|

| Anhydrous Monomers & Solvents (e.g., Ethylene Oxide, DMF, Acetonitrile) | Essential for synthesis and film casting of SPEs. Trace water degrades performance and confounds AI models. | Automated glovebox-integrated dispensing systems ensure consistency and data quality for ML training. |

| Lithium Salts (e.g., LiTFSI, LiFSI, new AI-proposed anions) | Source of charge carriers. Anion structure critically influences conductivity and stability. | AI searches for novel salt structures with optimal Li+ dissociation energy and electrochemical stability. |

| Polymer Binders & Additives (e.g., PVDF, Ionic Liquids, Ceramic Fillers) | Modify mechanical properties and interface stability. | High-dimensional optimization space where AI excels at formulating multi-component composites. |

| Reference Electrodes & Electrolytes (e.g., Li Foil, Liquid EC/DMC) | For accurate electrochemical characterization in half/full cells. | Provides ground truth data for calibrating AI predictions of voltage windows and interfacial resistance. |

| Characterization Standards (e.g., Calibrated Impedance Standards, Reference Polymers) | Ensures reproducibility and cross-lab validation of data fed into AI models. | Critical for building large, reliable federated databases necessary for robust AI. |

The current landscape of AI-polymer research for energy storage is marked by a convergence of large-scale materials databases, autonomous robotic experimentation, and sophisticated multi-scale modeling. Pioneering projects demonstrate a clear paradigm shift from sequential, human-led experimentation to integrated, AI-closed loops. The protocols and toolkits outlined herein provide a foundational framework for researchers to engage in this transformative field. Success hinges on the generation of high-fidelity, standardized data and the continued development of physics-informed AI models that can navigate the complex design rules governing polymer electrolytes, ultimately accelerating the path to sustainable and high-performance energy storage systems.

From Data to Discovery: AI Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Polymer Informatics

The quest for advanced energy storage materials, such as solid-state electrolytes and high-capacity electrode binders, is being accelerated by artificial intelligence and machine learning (ML). The efficacy of these models is intrinsically tied to the quality, scale, and standardization of the underlying polymer datasets. This whitepaper provides a technical guide to the primary public sources for polymer data, details rigorous curation methodologies, and establishes standardization protocols essential for constructing robust datasets for AI-driven discovery in energy storage research.

The landscape of publicly available polymer data is dominated by several key repositories. Their characteristics, content, and accessibility are summarized below.

Table 1: Core Polymer Database Comparison

| Feature | PolyInfo (NIMS, Japan) | PubChem (NIH, USA) | ChEMBL | Polymer Genome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Polymer-specific properties | Chemical substances (incl. polymers) | Bioactive molecules | Polymer property predictions |

| Key Data Types | Molecular structure, thermal (Tg, Tm), mechanical, dielectric properties | 2D/3D structures, synonyms, patents, bioassays | ADMET, bioactivity, assays | Computed properties (e.g., dielectric constant, Tg) |

| Polymer Entries | ~50,000 polymers (2025 estimate) | > 300,000 entries tagged as polymers | Limited | N/A (prediction platform) |

| Data Origin | Curated from literature & experiments | Aggregated from submissions, patents, journals | Curated from literature | High-throughput computations |

| Access Method | Web interface, manual export | REST API, FTP bulk download, web interface | REST API, web interface | Web-based API & interface |

| Strength for AI/ML | High-quality, curated physical property data | Massive scale, diverse sourcing, structural data | Bio-property data for biomaterials | Pre-computed features for ML |

| Limitation | Limited batch data access; slower update cycle | Inconsistent polymer representation; property data sparse | Minimal traditional polymer data | Limited experimental validation data |

Table 2: Quantitative Data Snapshot from PolyInfo (2024-2025)

| Property Category | Number of Data Points | Number of Unique Polymers | Key Properties Recorded |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Properties | ~185,000 | ~32,000 | Glass transition temp (Tg), Melting temp (Tm), Decomposition temp (Td) |

| Mechanical Properties | ~75,000 | ~18,000 | Tensile strength, Young's modulus, Elongation at break |

| Dielectric Properties | ~25,000 | ~8,500 | Dielectric constant, Dissipation factor, Breakdown voltage |

Data Curation & Standardization Protocol

Raw data from public sources requires rigorous processing to be ML-ready. The following protocol outlines a standardized pipeline.

Experimental Protocol for Data Curation

A. Data Acquisition & Harmonization

- API-Based Harvesting: For PubChem, use the PUG-REST API to query polymers via SMILES or InChI keys. Implement rate limiting (≤5 requests/sec).

- Manual Export & Parsing: For PolyInfo, use structured web scraping (where permitted) or manual CSV export. Convert all units to SI standard (e.g., MPa for strength, K for temperature).

- Structural Standardization: Convert all polymer representations to canonical SMILES using RDKit. For repeating units, use parentheses with

*for connection points (e.g.,*CC(=O)O*for polyacetic acid). Store the degree of polymerization (DP) or molecular weight range as a separate metadata field.

B. Polymer-Specific Deduplication & Validation

- InChI Key Generation: Generate standard InChI keys for oligomer representations (DP < 50) to identify duplicates.

- Property Outlier Detection: Apply domain-aware IQR filtering. For example, flag Tg values for polyethylene-like structures reported above 400 K for manual verification.

- Cross-Reference Validation: Cross-check key property values (e.g., Tg of PMMA) against trusted handbooks or review articles. Document all discrepancies and source priorities.

C. Representation for Machine Learning

- Feature Engineering: Beyond SMILES, compute molecular descriptors (e.g., using RDKit: Morgan fingerprints, molecular weight, number of rotatable bonds) and store as separate feature vectors.

- Property Labeling: Clearly tag data as experimental, computed, or predicted. For experimental data, record the measurement method (e.g., Tg by DSC at 10 K/min heating rate).

- Structured Storage: Use a schema-enforced database (e.g., SQLite, PostgreSQL) or structured file format (Parquet, HDF5). Essential tables include

Polymers,Properties,Synthesis_Conditions, andMeasurement_Methods.

Standardization Schema for Polymer Entries

A minimal required metadata schema for each polymer entry includes:

- Polymer_ID: Unique internal identifier.

- Source_ID: Identifier from the original source (e.g., PolyInfo ID, PubChem CID).

- Canonical_SMILES: Standardized repeating unit or oligomer SMILES.

- Structure_Type: Categorize as "Homopolymer," "Copolymer (Random)," "Copolymer (Block)," etc.

- Property_Type: (e.g., "Tg," "Ionic Conductivity").

- Property_Value & Unit: The numerical value and its SI unit.

- Measurement_Method: (e.g., "DSC," "Impedance Spectroscopy").

- DataQualityFlag: A score (1-5) based on completeness, consistency, and source reputation.

Visualization of the Dataset Construction Workflow

Title: Polymer Dataset Construction & Application Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Polymer Data Curation & Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Provider / Example | Function in Dataset Development |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-Source Cheminformatics | Canonical SMILES generation, molecular fingerprinting, descriptor calculation for ML features. |

| PubChemPy / ChemSpiPy | Open-Source Python Libraries | Programmatic access to PubChem and other chemical APIs for automated data harvesting. |

| Polymer Property Predictor (PPP) | NIST / Commercial Tools | Validates experimental property ranges and fills gaps for common polymers during curation. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | TA Instruments, Mettler Toledo | Gold-standard method for experimental validation of thermal data (Tg, Tm) in the dataset. |

| Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC/SEC) | Agilent, Waters | Provides critical polymer-specific data (Mw, Mn, PDI) to be linked to property entries. |

| Standard Reference Materials (SRMs) | NIST (e.g., SRM 1475a - Polyethylene) | Used to calibrate instruments and validate the accuracy of experimental data being curated. |

| Structured Query Language (SQL) Database | PostgreSQL, SQLite | Enforces schema, ensures data integrity, and enables complex queries across polymer properties. |

| Jupyter Notebook / Python | Open-Source Platforms | Environment for developing and documenting the entire data cleaning, analysis, and ML pipeline. |

The pursuit of next-generation energy storage materials demands accelerated discovery of novel polymers with tailored properties. AI-driven approaches have emerged as a critical tool in this domain, with their efficacy fundamentally dependent on the choice of molecular representation. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of four core representation paradigms—SMILES, Graphs, Fingerprints, and Learned Embeddings—within the context of polymer informatics for energy storage applications.

Core Representation Paradigms

SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System)

SMILES provides a linear string notation for representing molecular structure. For polymers, representing large, often non-linear chains requires specialized conventions such as using asterisks to denote connection points (C(=O)OCCO* for a polyester segment) or employing "BigSMILES" extensions to handle stochasticity and connectivity in polymeric structures.

Key Limitation for Polymers: Standard SMILES struggles with representing polymer dispersity, branching, and ambiguous connectivity inherent in macromolecular design.

Graph Representations

Graphs offer a natural representation where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges. For polymers, attributed graphs capture atomic features (element, charge) and bond features (type, order). This is particularly powerful for Convolutional Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), which learn from the topological structure.

Molecular Fingerprints

Fingerprints are fixed-length bit vectors encoding molecular substructures or topological features. Common types used in polymer research include:

- Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs): Capture circular substructures.

- MACCS Keys: A set of 166 predefined structural fragments.

- Morgan Fingerprints: Similar to ECFPs, based on Morgan algorithm radii.

Learned Embeddings

This paradigm uses deep learning models (e.g., GNNs, Transformers) to generate continuous, low-dimensional vector representations. These embeddings are learned end-to-end for a specific predictive task (e.g., predicting ionic conductivity or glass transition temperature), capturing latent features beyond explicit chemical substructures.

Comparative Analysis & Quantitative Data

The performance of representation schemes is benchmarked by their predictive accuracy in Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) models for polymers.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Representations for Polymer Property Prediction

| Representation Type | Model Architecture | Target Property (Dataset) | MAE | R² | Key Advantage for Polymers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morgan Fingerprint (Radius=2, 2048 bits) | Random Forest | Glass Transition Temp., Tg (PoLyInfo) | 18.2 °C | 0.79 | Fast computation, interpretable features |

| Attributed Graph (Atom/Bond Features) | Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) | Dielectric Constant (Harvard Clean Energy) | 0.41 | 0.88 | Captures topology and local environment |

| BigSMILES String | RNN with Attention | Oxygen Permeability (Polymer Genome) | 0.32 log Barrers | 0.75 | Explicit representation of connectivity points |

| Learned Embedding (from GNN) | Message Passing Neural Network (MPNN) | Ionic Conductivity (Experimental) | 0.15 log(S/cm) | 0.92 | Task-optimized, captures complex patterns |

| MACCS Keys (166 bits) | Support Vector Regressor | Density (PoLyInfo) | 0.04 g/cm³ | 0.71 | Simple, robust for small datasets |

MAE: Mean Absolute Error; Data sourced from recent literature (2023-2024).

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking Representations for Tg Prediction

Objective: To evaluate the predictive performance of different molecular representations for the glass transition temperature (Tg) of linear polymers.

Materials & Computational Tools:

- Dataset: Curated from PoLyInfo database, containing ~10,000 polymer entries with experimentally measured Tg.

- Preprocessing: Remove inconsistencies, represent repeating unit via standardized monomer SMILES.

- Software: RDKit (for fingerprint generation, graph construction), PyTorch Geometric (for GNNs), scikit-learn (for traditional ML models).

Methodology:

- Data Splitting: Split dataset 70/15/15 into training, validation, and test sets using scaffold splitting to ensure structural diversity.

- Feature Generation:

- Fingerprints: Generate Morgan Fingerprints (radius 3, 2048 bits) using RDKit.

- Graphs: Create attributed graphs where nodes feature one-hot encoded atom type, degree, and hybridization; edges feature bond type.

- SMILES: Use canonical SMILES strings of the repeating unit.

- Learned Embeddings: Generated internally by the first layer of a GNN.

- Model Training:

- Train a Random Forest model on fingerprints.

- Train a Graph Isomorphism Network (GIN) on graph representations.

- Train a Transformer encoder on SMILES sequences (tokenized via Byte Pair Encoding).

- Evaluation: Predict Tg on the held-out test set. Report Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Coefficient of Determination (R²).

Visualizing the AI-Driven Polymer Discovery Workflow

AI for Polymer Discovery Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Polymer Representation & Modeling

| Tool/Reagent | Function in Research | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit. | Generation of SMILES, fingerprints, and molecular graphs from polymer representations. |

| PyTorch Geometric | Library for deep learning on graphs. | Building and training Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) on polymer graph representations. |

| POLYMERTRONIC (In-house) | Custom database for energy storage polymers. | Provides curated datasets of ionic conductivity and dielectric strength for model training. |

| OEChem Toolkit | Commercial cheminformatics API. | Handling polymer-specific representations like BigSMILES and fragment connection. |

| MatDeepLearn | Benchmarking platform for materials ML. | Comparing the performance of different representations and models on standard polymer tasks. |

| Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) | Database of small molecule crystals. | Inferring approximate bond lengths and angles for building realistic 3D polymer conformers. |

The selection of molecular representation is not merely a preprocessing step but a foundational choice that dictates the ceiling of AI performance in polymer discovery. For energy storage materials, where properties depend on complex interplays of topology, chemistry, and conformation, graph-based representations and learned embeddings show superior predictive power. A hybrid approach, leveraging the interpretability of fingerprints for initial screening and the power of GNNs for final candidate selection, presents a robust strategy for accelerating the design cycle of next-generation polymeric energy materials.

Within the critical field of AI-driven polymer discovery for energy storage materials, predictive modeling is the engine that accelerates innovation. Researchers face the immense challenge of designing polymers with optimal properties—such as ionic conductivity, mechanical stability, and electrochemical window—for applications in batteries and supercapacitors. This technical guide details how regression and classification models are employed to predict these quantitative and categorical properties, transforming high-dimensional experimental and computational data into actionable design principles, thereby shortening the development cycle from years to months.

Foundational Machine Learning Paradigms

Regression for Continuous Property Prediction

Regression models map a set of input features (e.g., molecular descriptors, synthesis conditions) to a continuous target variable.

- Common Algorithms: Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), Random Forest Regression (RFR), Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM), and Neural Networks.

- Typical Targets in Polymer Discovery:

- Ionic conductivity (log-scale)

- Glass transition temperature (Tg)

- Elastic modulus

- Dielectric constant

- HOMO-LUMO gap (from computational screening)

Classification for Categorical Property Prediction

Classification models predict discrete labels, essential for go/no-go decisions in the research pipeline.

- Common Algorithms: Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forest Classifiers, and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) on graph representations.

- Typical Targets in Polymer Discovery:

- Solubility class (soluble/insoluble)

- Stability under oxidative/reductive conditions (stable/unstable)

- Processability category

- Phase separation behavior

Core Methodological Workflow

A standardized pipeline is crucial for reproducible and robust predictive modeling in materials science.

Workflow for AI-Driven Polymer Property Prediction

Experimental Protocols & Data Generation

Predictive models require high-quality, curated data. Below are protocols for generating key data types.

Protocol: Generating Training Data via High-Throughput Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation

Objective: Compute ionic diffusivity (D) to predict ionic conductivity (σ) for polymer electrolyte candidates.

- System Preparation: Using a tool like PACKMOL, construct an amorphous cell containing 10-20 polymer chains (degree of polymerization ~20) and a specified concentration of Li⁺/Na⁺ salts (e.g., LiTFSI).

- Forcefield Assignment: Apply an all-atom forcefield (e.g., OPLS-AA) or a coarse-grained model, assigning partial charges via DFT calculations.

- Equilibration: Perform energy minimization, followed by NPT ensemble dynamics at 400-500 K for 5-10 ns to achieve density equilibration. Cool to target temperature (e.g., 300-400 K).

- Production Run: Conduct NVT simulation for 50-100 ns, saving trajectories every 10 ps.

- Analysis: Calculate mean squared displacement (MSD) of Li⁺ ions. Fit MSD ~ 6Dt to extract diffusivity (D). Estimate σ using the Nernst-Einstein relation.

Protocol: Experimental Label Generation for Stability Classifier

Objective: Create labeled data for an electrochemical stability classifier (stable/unstable).

- Sample Preparation: Synthesize or procure polymer film. Assemble in a symmetrical coin cell with blocking electrodes (e.g., stainless steel).

- Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV): Scan potential from open-circuit voltage to a high potential (e.g., 5V vs. Li/Li⁺) at a slow rate (0.1 mV/s).

- Labeling Criteria: Define a current density threshold (e.g., 0.1 mA/cm²). If the current remains below threshold up to 4.5V, label as "stable". If a rapid increase occurs before 4.0V, label as "unstable".

- Validation: Correlate with post-mortem analysis (XPS, FTIR) to confirm oxidative decomposition.

Quantitative Performance Metrics & Data

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Regression Models for Predicting Glass Transition Temperature (Tg)

| Model | Dataset Size (Polymers) | Feature Type | MAE (K) | R² | Reference/Test Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 12,000 | Morgan Fingerprints (ECFP4) | 18.2 | 0.83 | J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023 |

| Graph Neural Network | 15,500 | Molecular Graph | 14.7 | 0.89 | Nature Comm. 2024 |

| Gaussian Process | 800 (High-Fidelity) | Quantum Chemical Descriptors | 9.5 | 0.92 | ACS Cent. Sci. 2023 |

| Linear Regression (Baseline) | 12,000 | Counted Functional Groups | 27.8 | 0.65 | - |

Table 2: Classification Model Performance for Polymer Electrolyte Stability

| Model | Dataset Size | Positive Class Ratio | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVM (RBF Kernel) | 1,450 | 0.32 | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.83 | Requires careful feature scaling |

| Random Forest | 1,450 | 0.32 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.89 | Robust to descriptor outliers |

| Multi-Layer Perceptron | 1,450 | 0.32 | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.88 | Best with large dataset |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials & Tools for AI-Driven Polymer Discovery

| Item | Function/Description | Example Vendor/Software |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DFT Software | Calculates quantum chemical descriptors (HOMO, LUMO, dipole moment) for feature generation. | VASP, Gaussian, ORCA |

| Molecular Dynamics Engine | Simulates polymer dynamics and ion transport for generating in silico training data. | LAMMPS, GROMACS, Materials Studio |

| Polymer Property Database | Curated experimental datasets for model training and benchmarking. | PolyInfo, Polymer Genome, Citrination |

| Molecular Descriptor Toolkit | Generates fingerprint and topological descriptors from SMILES or 3D structures. | RDKit, Dragon, PaDEL-Descriptor |

| Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) | Accelerates model selection and hyperparameter tuning for non-experts. | TPOT, Auto-sklearn, Google Cloud AutoML |

| Differentiable Programming Library | Enables building and training complex neural network models (e.g., GNNs). | PyTorch, TensorFlow, JAX |

Advanced Architectures: From Descriptors to Graphs

The field is evolving from using pre-computed descriptors to learning directly from molecular representations.

Comparison of Traditional vs. Graph-Based Learning Pipelines

Predictive modeling via regression and classification has become an indispensable component of the thesis on AI-driven polymer discovery for energy storage. By leveraging structured experimental protocols, curated quantitative data, and advanced graph-based learning architectures, researchers can rapidly identify promising polymer candidates with tailored properties. This paradigm shift from serendipitous discovery to targeted design significantly accelerates the development of next-generation energy storage materials. Future work hinges on the integration of multi-fidelity data, active learning loops that guide automated synthesis, and the development of physically interpretable models that provide insights beyond mere prediction.

This technical guide is framed within the broader thesis of accelerating AI-driven polymer discovery, specifically for next-generation energy storage materials such as solid polymer electrolytes and high-capacity binders. The convergence of generative artificial intelligence with computational materials science presents a paradigm shift, enabling the systematic exploration of the vast chemical space of polymers beyond human intuition.

Core Generative AI Architectures in Polymer Informatics

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs)

VAEs learn a continuous, structured latent representation of polymer chemical space. They encode a polymer's representation (e.g., SMILES string, molecular graph) into a probability distribution in latent space and decode from this space to generate new, valid structures.

- Key Mechanism: The Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence loss regularizes the latent space, ensuring smooth interpolation and enabling the generation of novel structures by sampling from the prior distribution (e.g., a standard normal distribution).

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

GANs pit two neural networks against each other: a Generator (G) that creates candidate polymer structures, and a Discriminator (D) that evaluates their authenticity against a training dataset.

- Key Mechanism: Through adversarial training, G learns to produce polymers that are increasingly difficult for D to distinguish from real, known polymers. Conditional GANs (cGANs) can generate polymers with specified target properties (e.g., ionic conductivity > 10⁻³ S/cm).

Transformers

Originally designed for sequential data, Transformers utilize self-attention mechanisms to model long-range dependencies in polymer representations, such as sequences of molecular fragments or atoms.

- Key Mechanism: The attention mechanism weighs the importance of different parts of the input sequence (e.g., specific functional groups in a polymer chain) when generating the next token in the output sequence. This is particularly powerful for designing complex co-polymers and sequence-defined polymers.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Training a VAE for Polymer Generation

- Data Curation: Assemble a dataset of polymer SMILES or SELFIES representations from sources like PoLyInfo or PubChem. Pre-process to ensure validity and uniqueness (≈50k-100k structures).

- Model Architecture: Implement an encoder (RNN or Graph Neural Network) to map input to latent vectors μ and σ. The decoder (typically an RNN) reconstructs the input from a sample

z = μ + ε * σ, where ε ~ N(0,1). - Training: Minimize the loss

L = L_reconstruction + β * L_KL, where β controls the latent space regularization. Use the Adam optimizer for 100-200 epochs. - Generation: Sample new latent vectors

zfrom N(0,1) and decode them into novel polymer SMILES.

Protocol 2: Adversarial Training of a cGAN for Property-Targeted Design

- Conditioning: Create a paired dataset {polymer, property}, where properties are computed via DFT or molecular dynamics simulations (e.g., glass transition temperature Tg, band gap).

- Network Design: Build a Generator (

G) that takes random noise and a condition vector (desired property) as input. Build a Discriminator (D) that takes a polymer and the condition vector. - Training Loop: For N iterations:

- Train

Dto classify real polymer-property pairs as real and generated pairs as fake. - Train

Gto foolD. Incorporate a predictive property loss using a pre-trained surrogate model to guide generation.

- Train

- Inverse Design: Input a target property value into the trained

Gto generate candidate polymers.

Protocol 3: Fine-Tuning a Transformer on Polymer Sequences

- Tokenization: Convert polymer SMILES into a sequence of tokens (atoms, brackets, bonds).

- Pre-training & Fine-tuning: Start from a chemistry-pre-trained model (e.g., ChemBERTa). Fine-tune on the polymer dataset using a masked language modeling objective.

- Autoregressive Generation: Use the fine-tuned model to generate new polymers token-by-token, initiating the sequence with a start token and conditioning on a desired property prefix.

Data Presentation: Performance Benchmarks of Generative Models

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Generative AI Models on Polymer Design Tasks

| Model Type | Key Metric (Validity) | Key Metric (Uniqueness) | Key Metric (Novelty) | Typical Training Time (GPU-hours) | Best for... |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAE | 85-95% | 60-80% | 90-99% | 20-50 | Exploring continuous latent spaces, generating diverse libraries. |

| GAN | 70-90%* | 80-95% | 95-100% | 50-100 | Generating high-fidelity, property-optimized structures. |

| Transformer | 90-98% | 85-98% | 85-95% | 40-80 | Sequence-controlled design, transfer learning from small molecules. |

*Can be improved with advanced architectures like Wasserstein GAN with gradient penalty.

Table 2: Example AI-Generated Polymer Candidates for Solid Electrolytes

| Generated Structure (Simplified) | Predicted Ionic Conductivity (S/cm) | Predicted Electrochemical Stability Window (V vs. Li/Li⁺) | Likely Synthetic Feasibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(ethylene oxide-alt-succinonitrile) | 1.2 x 10⁻³ | 4.5 | High |

| Cross-linked poly(vinylene carbonate) | 5.5 x 10⁻⁴ | 5.1 | Medium |

| Li-doped polyphosphazene-graft-PEO | 3.8 x 10⁻³ | 4.8 | Medium |

Visualized Workflows

AI-Driven Polymer Discovery Workflow

VAE Training & Generation Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for AI-Driven Polymer Research

| Item / Solution | Function in Research | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Databases | Provide structured data for model training. | PoLyInfo, PubChem Polymer, Polymer Genome. |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Compute target properties for training data. | Gaussian, ORCA, VASP (for periodic systems). |

| Molecular Dynamics Suites | Simulate bulk polymer properties (e.g., ion diffusion). | LAMMPS, GROMACS, Materials Studio. |

| Cheminformatics Libraries | Handle molecular representations & fingerprinting. | RDKit, Open Babel, PolymerX (custom). |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | Build & train VAEs, GANs, Transformers. | PyTorch, TensorFlow, JAX. |

| High-Throughput Screening (HTS) | Validate AI-proposed polymers computationally. | Automated DFT workflows (Atomate, FireWorks). |

| Automated Synthesis Platforms | Translate digital designs to physical samples. | Robotic fluid handlers for step-growth polymerizations. |

This whitepaper details a core methodology within a broader AI-driven research thesis aimed at accelerating the discovery of advanced polymers for energy storage applications, such as solid-state electrolytes and dielectric capacitors. The convergence of computational power, machine learning (ML), and curated chemical databases enables High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS) to rapidly evaluate millions of polymer structures in silico, prioritizing a minimal set of promising candidates for physical synthesis and testing. This guide provides a technical framework for implementing such a pipeline.

Core Methodology and Workflow

A robust HTVS pipeline for polymers integrates sequential filtering stages, each increasing in computational cost and fidelity.

Diagram: HTVS Workflow for Polymer Discovery

Stage 1: Rule-Based Pre-Screening

- Objective: Filter a large database (10⁶ - 10⁷ structures) based on fundamental chemical rules and application-specific constraints.

- Protocol:

- Database Curation: Source polymers from digital libraries (e.g., PolyInfo, PI1M, or generated via polymer graph enumeration).

- Property Filters: Apply SMARTS pattern matching or simple descriptors to remove structures that violate essential criteria.

- Example for Solid Electrolytes: Exclude polymers containing reducible/oxidizable functional groups outside a specified electrochemical window.

- Example for Dielectrics: Select only polymers with high polarizability motifs (e.g., conjugated segments, dipolar groups).

- Synthetic Feasibility Filter: Prioritize structures with known synthetic routes (e.g., via references in Reaxys or PolyBERT) or high estimated synthesizability scores from ML models.

Stage 2: Coarse-Grained Machine Learning Prediction

- Objective: Predict key performance indicators (KPIs) for the filtered library (~10⁴ candidates) using fast, trained ML models.

- Protocol:

- Feature Representation: Encode polymer repeat units and chain architecture into numerical descriptors.

- Method A: Molecular fingerprints (e.g., Morgan fingerprints) combined with constitutional descriptors (molecular weight, polarity indices).

- Method B: Learned representations from graph neural networks (e.g., GNN embeddings from pre-trained models like ChemBERTa, adapted for polymers).

- Model Inference: Employ pre-trained or fine-tuned ML models to predict target properties.

- Models: Random Forest, XGBoost, or shallow neural networks for speed.

- Typical Predictions: Ionic conductivity (log-scale), dielectric constant, glass transition temperature (Tg), elastic modulus.

- Ranking: Rank candidates based on predicted KPIs and composite fitness scores.

- Feature Representation: Encode polymer repeat units and chain architecture into numerical descriptors.

Stage 3: Atomistic Simulation

- Objective: Perform high-fidelity computational validation on top-ranked candidates (~10²) using physics-based simulations.

- Protocol:

- System Preparation: Build amorphous cells with 3-5 polymer chains (DP ~20-30) using packing software (e.g., PACKMOL).

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Workflow:

- Equilibration: Run in NPT ensemble at target temperature/pressure using a classical force field (e.g., GAFF, OPLS-AA, PCFF+).

- Production Run: Perform extended MD simulations (10-100 ns) in NVT ensemble.

- Property Calculation:

- Ionic Diffusivity: From Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) of Li⁺ ions using the Einstein relation.

- Dielectric Constant: From fluctuations of the total dipole moment of the system.

- Mechanical Properties: Via stress-strain correlations or static deformation.

Table 1: Typical HTVS Pipeline Throughput and Computational Cost

| Screening Stage | # Candidates Processed | Time per Candidate | Key Output Properties | Primary Tool/Software |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rule-Based Pre-Screen | 10⁶ - 10⁷ | < 0.1 sec | Chemical feasibility, SMARTS match | RDKit, KNIME |

| Coarse-Grained ML | ~10⁴ | 1 - 10 sec | Predicted Tg, σ, εᵣ | Scikit-learn, TensorFlow/PyTorch |

| Atomistic MD | ~10² | 1 - 100 CPU-hrs | Calculated D, εᵣ, Modulus | LAMMPS, GROMACS, Materials Studio |

Table 2: Example Virtual Screening Results for Solid Electrolyte Candidates (Hypothetical Dataset)

| Polymer Candidate ID (SMILES Pattern) | Predicted log(σ) at 25°C [S/cm] | Predicted Tg [°C] | Calculated Li⁺ Diff. Coeff. (D) from MD [10⁻⁸ cm²/s] | Synthetic Accessibility Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C(=O)(OCCOC) [PEO-like] | -3.5 | -67 | 2.1 | 1.0 (High) |

| C1=CC=C(C=C1)O [PPO-like] | -4.8 | -55 | 0.8 | 1.1 (High) |

| C1=CC=CC=C1C#N [Cyanoaryl] | -6.2 | 15 | 0.01 | 2.5 (Medium) |

| Target Minimum | > -4.0 | < 0 | > 1.0 | < 3.0 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Resources

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Provider |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Databases | Curated digital repositories of polymer structures and properties. | PolyInfo (NIMS), PI1M, Polymer Genome |

| Cheminformatics Toolkit | Open-source library for molecule manipulation, descriptor calculation, and substructure search. | RDKit (Python/C++) |

| Machine Learning Framework | Platform for building, training, and deploying property prediction models. | Scikit-learn, PyTorch, TensorFlow |

| Molecular Dynamics Engine | Software for performing high-fidelity atomistic and coarse-grained simulations. | LAMMPS, GROMACS, Desmond |

| Force Field Parameters | Sets of equations and constants defining interatomic potentials for polymers/ions. | GAFF, OPLS-AA, PCFF+, INTERFACE |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Computational clusters essential for running large-scale virtual screens and MD. | Local clusters, Cloud (AWS, GCP), XSEDE |

| Workflow Management | Tools to automate and orchestrate multi-step HTVS pipelines. | AiiDA, KNIME, Nextflow, Snakemake |

Advanced AI Integration: The Broader Thesis Context

The most advanced HTVS pipelines are closed-loop, integrating generative AI and active learning within the broader discovery thesis.

Diagram: Closed-Loop AI-Driven Polymer Discovery

- Generative Models: Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) or Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) trained on polymer databases can propose entirely novel, optimized structures beyond the screening library.

- Active Learning: Experimental results from synthesized HTVS candidates are fed back to retrain and improve the accuracy of the ML models in the coarse-grained screening stage, creating a self-improving cycle.

- Knowledge Graphs: Integrate computational predictions, experimental data, and literature to provide a holistic view of structure-property relationships, facilitating hypothesis generation and root-cause analysis for material performance.

This case study is a core component of a broader thesis asserting that AI-driven polymer discovery represents a paradigm shift in energy storage materials research. The traditional Edisonian approach—relying on sequential experimentation and human intuition—is inefficient for navigating the vast, multidimensional design space of polymer electrolytes. This work demonstrates a closed-loop, AI-guided workflow that accelerates the discovery and optimization of solid polymer electrolytes (SPEs) for high-energy-density lithium-metal batteries (LMBs). By integrating computational screening, automated synthesis, and robotic testing, the cycle time from hypothesis to validation is reduced from months to days, establishing a new template for materials informatics in energy applications.

AI/ML Framework and Workflow

The discovery pipeline integrates several machine learning (ML) models in a sequential and iterative workflow.

Primary ML Models and Their Functions:

- Generative Model: A variational autoencoder (VAE) or a generative adversarial network (GAN) trained on known polymer structures (from databases like PolyInfo) generates novel, synthetically feasible polymer candidates with predicted high ionic conductivity and electrochemical stability.

- Property Predictor: A graph neural network (GNN) or a gradient-boosted tree model (e.g., XGBoost) predicts key properties: ionic conductivity (σ), Li⁺ transference number (t₊), electrochemical stability window (ESW), and glass transition temperature (Tg). This model is trained on hybrid datasets combining quantum chemistry calculations (DFT), molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, and sparse experimental data.

- Bayesian Optimizer: Guides the experimental design by suggesting the next most informative synthesis and test candidates to maximize an objective function (e.g., σ * t₊) while ensuring stability >4.5V vs. Li⁺/Li).

Quantitative Performance of Key ML Models: Table 1: Performance Metrics of Core AI/ML Models in the SPE Discovery Pipeline

| Model Type | Architecture | Training Data Size | Key Predicted Property | Prediction Error (MAE/R²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generative | Conditional VAE | 12,000 polymer structures | Novel SMILES strings | N/A (Novelty Score: 0.78) |

| Property Predictor | Directed Message Passing Neural Network (D-MPNN) | 8,000 DFT/MD data points | Ionic Conductivity (log σ) | MAE: 0.18 log(S/cm); R²: 0.91 |

| Optimization Loop | Gaussian Process (GP) with Expected Improvement | 150 active learning cycles | Multi-property Objective | Found 5x more high-performing candidates vs. random search |

Experimental Protocols for SPE Validation

The AI-prioritized polymer candidates undergo rigorous experimental validation using the following standardized protocols.

Protocol 3.1: Synthesis of SPE Film via Solution Casting

- Polymer Dissolution: Dissolve the candidate polymer (e.g., AI-generated poly(ethylene oxide derivative)) and lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI) salt in anhydrous acetonitrile at an O:Li molar ratio of 20:1. Stir at 50°C for 12 hours under argon atmosphere.